the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Reviews and syntheses: Dams, water quality and tropical reservoir stratification

Robert Scott Winton

Elisa Calamita

Bernhard Wehrli

The impact of large dams is a popular topic in environmental science, but the importance of altered water quality as a driver of ecological impacts is often missing from such discussions. This is partly because information on the relationship between dams and water quality is relatively sparse and fragmentary, especially for low-latitude developing countries where dam building is now concentrated. In this paper, we review and synthesize information on the effects of damming on water quality with a special focus on low latitudes. We find that two ultimate physical processes drive most water quality changes: the trapping of sediments and nutrients, and thermal stratification in reservoirs. Since stratification emerges as an important driver and there is ambiguity in the literature regarding the stratification behavior of water bodies in the tropics, we synthesize data and literature on the 54 largest low-latitude reservoirs to assess their mixing behavior using three classification schemes. Direct observations from literature as well as classifications based on climate and/or morphometry suggest that most, if not all, low-latitude reservoirs will stratify on at least a seasonal basis. This finding suggests that low-latitude dams have the potential to discharge cooler, anoxic deep water, which can degrade downstream ecosystems by altering thermal regimes or causing hypoxic stress. Many of these reservoirs are also capable of efficient trapping of sediments and bed load, transforming or destroying downstream ecosystems, such as floodplains and deltas. Water quality impacts imposed by stratification and sediment trapping can be mitigated through a variety of approaches, but implementation often meets physical or financial constraints. The impending construction of thousands of planned low-latitude dams will alter water quality throughout tropical and subtropical rivers. These changes and associated environmental impacts need to be better understood by better baseline data and more sophisticated predictors of reservoir stratification behavior. Improved environmental impact assessments and dam designs have the potential to mitigate both existing and future potential impacts.

- Article

(1929 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(171 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

As a global dam construction boom transforms the world's low-latitude river systems (Zarfl et al., 2014) there is a serious concern about how competing demands for water, energy and food resources will unfold. The challenge created by dams is not merely that they can limit the availability of water to downstream peoples and ecosystems, but also that the physical and chemical quality of any released water is often altered drastically (Friedl and Wüest, 2002; Kunz et al., 2011). Access to sufficient quality of water is a United Nations Environment Programme sustainable development goal (UNEP, 2016), and yet the potential negative effects of dams on water quality are rarely emphasized in overviews of impacts of dams (Gibson et al., 2017).

Dams are often criticized by ecologists and biogeochemists for fragmenting habitats (Anderson et al., 2018; Winemiller et al., 2016), disrupting floodplain hydrologic cycles (Kingsford and Thomas, 2004; Mumba and Thompson, 2005; Power et al., 1996) and for emitting large amounts of methane (Delsontro et al., 2011). Such impacts act against the promise of carbon-neutral hydropower (Deemer et al., 2016). In contrast, scientists have committed less investigative effort to documenting the potential impacts of dams on water quality. In cases where investigators have synthesized knowledge of water quality impacts (Friedl and Wüest, 2002; Nilsson and Renofalt, 2008; Petts, 1986), the conclusions are inevitably biased towards mid/high latitudes where the bulk of case studies and mitigation efforts have occurred.

While there is much to be learned from more thoroughly studied high-latitude rivers, given the fundamental role played by climate in river and lake functioning, it is important to consider how the low-latitude reservoirs may behave differently. For example, the process of reservoir stratification, which plays a crucial role in driving downstream water quality impacts, is governed to a large degree by local climate. Additionally, tropical aquatic systems are more prone to suffer from oxygen depletion because of lower oxygen solubility and faster organic matter decomposition at higher temperatures (Lewis, 2000). Latitude also plays an important role in considering ecological or physiological responses to altered water quality. Studies focused on cold-water fish species may have little applicability to warmer rivers in the subtropics and tropics.

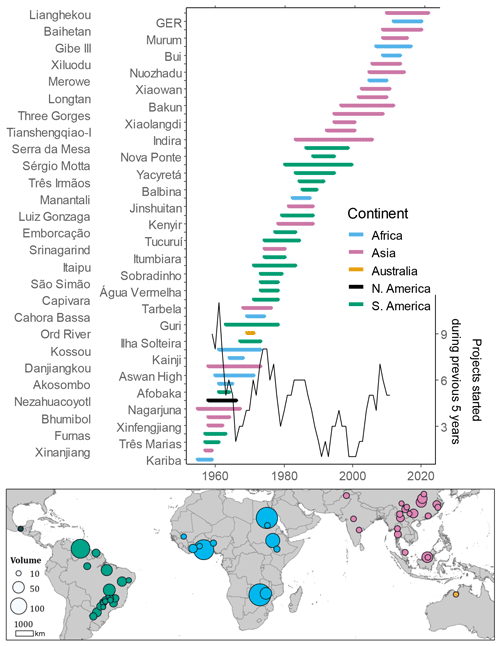

Low-latitude river systems are experiencing a high rate of new impacts from very large dam projects. A review of the construction history of very large reservoirs of at least 10 km3 below latitude reveals that few projects were launched between 1987 and 2000, but in the recent decade (2001–2011) low-latitude mega-reservoirs have appeared at a rate of one new project per year (Fig. 1). Given that ongoing and proposed major dam projects are concentrated at low latitudes (Zarfl et al., 2014), a specific review of water quality impacts of dams and the extent to which they are understood and manageable in tropical biomes is needed.

Figure 1Construction history of the world's 54 largest reservoirs located below ±35∘ latitude. Project year of completion data are from the International Commission on Large Dams (https://www.icold-cigb.net/, last access: 1 November 2018). Project start data are approximate (±1 year) and based on either gray literature source or for some more recent dams, i.e., visual inspection of Google Earth satellite imagery. Grand Ethiopian Renaissance abbreviated as GER. Volume in map legend is in cubic kilometers.

Large dams exert impacts across many dimension; but in this review, we largely ignore the important, but well-covered, impacts of altered hydrologic regimes. Instead, we focus on water quality, while acknowledging that flow and water quality issues are often inextricable. We also disregard the important issue of habitat fragmentation and the many acute impacts on ecosystems and local human populations arising from dam construction activities (i.e., displacement and habitat loss due to inundation). These important topics have been recently reviewed elsewhere (e.g., Winemiller et al., 2016; Anderson et al., 2018).

In order to understand the severity and ubiquity of water quality impacts associated with dams, it is necessary to understand the process of lake stratification, which occurs because density gradients within lake water formed by solar heating of the water surface prevent efficient mixing. By isolating deep reservoir water from surface oxygen, stratification facilitates the development of low-oxygen conditions and a suite of chemical changes that can be passed downstream. To address the outstanding question of whether low-latitude reservoirs are likely to stratify and experience associated chemical water quality changes, we devote a section of this study to predicting reservoir stratification. This analysis includes the largest low-latitude reservoirs and is focused on physical and chemical processes within the reservoirs that may affect downstream water quality.

Finally, we review off-the-shelf efforts to manage or mitigate undesired chemical and ecological effects of dams related to water quality. The management of dam operations to minimize downstream ecological impacts follows the concept of environmental flows (eflows). The primary goal of eflows is to mimic natural hydrologic cycles for downstream ecosystems, which are otherwise impaired by conventional dam-altered hydrology of diminished flood peaks and higher minimum flows. Although restoring hydrology is vitally important to ecological functioning, it does not necessarily solve water quality impacts, which often require different types of management actions. Rather than duplicate the recent eflow reconceptualizations (e.g., Tharme, 2003; Richter, 2009; Olden and Naiman, 2010; O'Keeffe, 2018), we focus our review on dam management efforts that specifically target water quality, which includes both eflow and non-eflow actions.

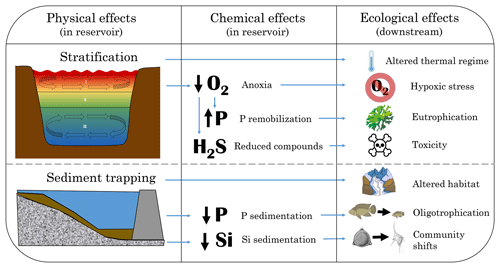

The act of damming and impounding a river imposes a fundamental physical change upon the river continuum. The river velocity slows as it approaches the dam wall and the created reservoir becomes a lacustrine system. The physical change of damming leads to chemical changes within the reservoir, which alters the physical and chemical water quality, which in turn leads to ecological impacts on downstream rivers and associated wetlands. The best-documented physical, chemical and ecological effects of damming on water quality are summarized in Fig. 2 and described in detail in this section. In each subsection, we begin with a general overview and then specifically consider the available evidence for low-latitude systems.

Figure 2Conceptual summary of the physical and chemical water quality effects of dams and how they affect aquatic ecology.

2.1 Stratification-related effects

Stratification, i.e., the separation of reservoir waters into stable layers of differing densities, has important consequences for river water downstream of dams. A key to understanding the impacts of dams on river water quality is a precise understanding of the depth of the reservoir thermocline/oxycline relative to spillway or turbine intakes. At many high-head-storage hydropower dams, the turbine intakes are more than 10–20 m deep to preserve generation capacity even under extreme drought conditions. For example, Kariba Dam's intakes pull water from 20 to 25 m below the typical level of the reservoir surface, which roughly coincides with the typical depth of the thermocline. In more turbid tropical reservoirs, thermocline depth can be much shallower, for example at Murum Reservoir in Indonesia where the epilimnion is just 4 to 6 m thick. Unfortunately, the turbine intake depths are not typically reported in dam databases. Furthermore, for many reservoirs, especially those in the tropics, the mixing behavior and therefore the typical depth of the thermocline are not well understood. Collecting the reservoir depth profiles necessary to generate this key information may be more difficult than simply analyzing water chemistry below dams. Dam tail waters with low oxygen or reduced compounds, such as hydrogen sulfide or dissolved methane, are likely to stem from discharged deep water of a stratified reservoir.

2.1.1 Changing thermal regimes

Even at low latitudes where seasonal differences are less than temperate climates, aquatic ecosystems experience water temperatures that fluctuate according to daily and annual thermal regimes (Olden and Naiman, 2010). Hypolimnetic releases of unseasonably cold water represent alterations to a natural regime. Although the difference between surface and deep waters in tropical lakes is typically much less than those at higher latitudes (Lewis, 1996), the differences are often much greater than the relatively subtle temperature shifts of 3–5 ∘C that have been shown to cause serious impacts (King et al., 1998; Preece and Jones, 2002). For example, at 17∘ south of the Equator, Lake Kariba seasonally reaches a 6 to 7 ∘C difference between surface and deep waters (Magadza, 2010). The ecological impacts of altered thermal regimes have been extensively documented across a range of river systems.

Many aquatic insects are highly sensitive to alterations in thermal regime (Eady et al., 2013; Ward and Stanford, 1982), with specific temperature thresholds required for completion of various life cycle phases (Vannote and Sweeney, 1980). Since macroinvertebrates form an important prey base for fish and other larger organisms, there will be cascading effects when insect life cycles are disrupted. Fish have their own set of thermal requirements, with species often filling specific thermal niches (Coutant, 1987). Altered thermal regimes can shift species distributions and community composition. Development schedules for both fish and insects respond to accumulated daily temperatures above or below a threshold, as well as absolute temperatures (Olden and Naiman, 2010). Fish and insects have both chronic and acute responses to extreme temperatures. A systemic meta-analysis of flow regulation on invertebrates and fish populations by Haxton and Findlay (2008) found that hypolimnetic releases tend to reduce abundance of aquatic species regardless of setting.

There exist several case studies from relatively low latitudes suggesting that tropical and subtropical rivers are susceptible to dam-imposed thermal impacts. The Murray cod has been severely impacted by cold-water pollution from the Dartmouth Dam in Victoria, Australia (Todd et al., 2005) and a variety of native fish species were similarly impacted by the Keepit Dam in New South Wales, Australia (Preece and Jones, 2002). In subtropical China, cold-water dam releases have caused fish spawning to be delayed by several weeks (Zhong and Power, 2015). In tropical Brazil, Sato et al. (2005) tracked disruptions to fish reproductive success 34 km downstream of the Três Marias Dam. In tropical South Africa, researchers monitoring downstream temperature-sensitive fish in regulated and unregulated rivers found that warm water flows promoted fish spawning, whereas flows of 3 to 5 ∘C cooler hypolimnetic water forced fish to emigrate (King et al., 1998).

2.1.2 Hypoxia

Stratification tends to lead to the deoxygenation of deep reservoir water, because of heterotrophic consumption and a lack of resupply from oxic surface layers. When dam intakes are deeper than the oxycline, hypoxic water can be passed downstream where it is suspected to cause significant ecological harm. Oxygen concentrations below 3.5 to 5 mg L−1 typically trigger escape behavior in higher organisms, whereas only well-adapted organisms survive below 2 mg L−1 (Spoor, 1990). A study of 19 dams in the southeastern United States found that 15 routinely released water with less than 5 mg L−1 of dissolved oxygen and 7 released water with less than 2 mg L−1 of dissolved oxygen (Higgins and Brock, 1999). Hypoxic releases from these dams often lasted for months and the hypoxic water was detectable in some cases for dozens of kilometers downstream. Below the Hume Dam in Australia, researchers found that oxygen concentrations reached an annual minimum of less than 50 % saturation (well under 5 mg L−1), while other un-impacted reference streams always had 100 % oxygen saturation (Walker et al., 1978). Researchers recently observed similar hypoxic conditions below the Bakun Dam in Malaysia with less than 5 mg L−1 recorded for more than 150 km downstream (Wera et al., 2019). Although observations and experiments have demonstrated the powerful stress that hypoxia exerts on many fish species (Coble, 1982; Spoor, 1990), there exist few well-documented field studies of dam-induced hypoxia disrupting downstream ecosystems. This is partly because it can be difficult to distinguish the relative importance of dissolved oxygen and other correlated chemical and physical parameters (Hill, 1968). Hypolimnetic dam releases containing low oxygen will necessarily also be colder than surface waters and they may contain toxic levels of ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, so it was not clear which factor was the main driver for the loss of benthic macroinvertebrate diversity documented below a dam of the Guadalupe River in Texas (Young et al., 1976).

Regardless, regulators in the southern US found the threat of hypoxia to be sufficiently serious to mandate that dam tail waters maintain a minimum dissolved oxygen content of 4 to 6 mg L−1 depending on temperature (Higgins and Brock, 1999). These dams in the Tennessee Valley are on the northern fringe of the subtropics (∼35–36∘ N), but are relatively warm compared with other reservoirs of the United States. Since oxygen is less soluble in warmer water and gas transfer is driven by the difference between equilibrium and actual concentrations, it follows that low-oxygen stretches downstream of low-latitude dams will suffer from slower oxygen recovery.

In addition to the direct impact imposed by hypoxic reservoir water when it is discharged downstream, anoxic bottom waters will also trigger a suite of anaerobic redox processes within reservoir sediments that exert additional alterations to water quality. Therefore, anoxia can also exert indirect chemical changes and associated ecological impacts. Here we discuss two particularly prevalent processes: phosphorus remobilization and the generation of soluble reduced compounds.

2.1.3 Phosphorus remobilization and eutrophication

Phosphorus (P) is an important macronutrient. Its scarcity or limited bioavailability to primary producers often limits productivity of aquatic systems. Conversely, the addition of dissolved P to aquatic ecosystems often stimulates eutrophication, leading to blooms of algae, phytoplankton or floating macrophytes on water surfaces (Carpenter et al., 1998; Smith, 2003). Typically, eutrophication will occur when P is imported into a system from some external source, but in the case of lakes and reservoirs internal P loading from sediments can also be important. Most P in the aquatic environment is bound to sediment particles where it is relatively unavailable for uptake by biota, but anoxic bottom waters of lakes greatly accelerate internal P loading (Nurnberg, 1984). Iron oxide particles are strong absorbers of dissolved ;, but under anoxic conditions, the iron serves as an electron acceptor and is reduced to a soluble ferrous form. During iron reduction, iron-bound P also becomes soluble and is released into solution where it can build up in hypolimnetic waters. Water rich in P is then either discharged through turbines or mixed with surface waters during periods of destratification. Therefore, sudden increases in bioavailable P can stimulate algal and other aquatic plant growth in the reservoir epilimnion. Theoretically, discharging of P-rich deep water could cause similar blooms in downstream river reaches, but we are not aware of any direct observations of this phenomenon. Typically, nutrient releases in low-latitude contexts are thought of as beneficial to downstream ecosystems because they would counteract the oligotrophication imposed by the dam through sediment trapping (Kunz et al., 2011).

Although dams seem to typically lead to overall reductions in downstream nutrient delivery (see “Oligotrophication”, Sect. 2.2.2), the phenomenon of within-reservoir eutrophication because of internal P loading has been extensively documented in lakes and reservoirs worldwide. In the absence of major anthropogenic nutrient inputs, the eutrophication is typically ephemeral and is abated after several years following reservoir creation. A well-known tropical example is Lake Kariba, the world's largest reservoir by volume. For many years after flooding a 10 % to 15 % of the lake surface was covered by Kariba weed (Salvinia molesta), a floating macrophyte. Limnologists attributed these blooms to decomposing organic matter and also gradual P release from inundated soils exposed to an anoxic hypolimnion (Marshall and Junor, 1981).

Indeed, some characteristics of tropical lakes seem to make them especially susceptible to P regeneration from the hypolimnion. The great depth to which mixing occurs (often 50 m or more) during destratification, a product of the mild thermal density gradient between surface and deep water, provides more opportunity to transport deep P back to the surface (Kilham and Kilham, 1990). This has led limnologists to conclude that deep tropical water bodies are more prone to eutrophication compared with their temperate counterparts (Lewis, 2000). There is of course variability within tropical lakes. Those with larger catchment areas tend to receive more sediments and nutrients from their inflowing rivers and are also more prone to eutrophication (Straskraba et al., 1993). These findings together suggest that thermally stratified low-latitude reservoirs run a high risk of experiencing problems of eutrophication because of internal P re-mobilization.

2.1.4 Reduced compounds

Another ecological stressor imposed by hypoxic reservoir water is a high concentration of reduced compounds, such as hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and reduced iron, which limit the capacity of the downstream river to cope with pollutants. Sufficient dissolved oxygen is not only necessary for the support of most forms of aquatic life, but it is also essential to maintaining oxidative self-purification processes within rivers (Friedl and Wüest, 2002; Petts, 1986). Reduced compounds limit the oxidative capacity of river water by acting as a sink for free dissolved oxygen. The occurrence of H2S has been documented in some cases in the tail waters of dams, but the co-occurrence of this stressor with low temperatures and hypoxia make it difficult to attribute the extent to which it causes direct ecological harm (Young et al., 1976). Researchers investigating fish mortality below Greens Ferry Dam in Arkansas, USA, found H2S concentrations of 0.1 mg L−1 (Grizzle, 1981), well above the recognized lethal concentrations of 0.013 to 0.045 mg L−1 of H2S for fish based on toxicological studies (Smith et al., 1976). Lethal concentrations of ammonia for fish are 0.75 to 3.4 mg L−1 of unionized NH3 (Thurston et al., 1983), though we are unaware of specific cases where these thresholds have been surpassed because of dams. At the very least, the presence of reduced compounds at elevated concentrations indicates that an aquatic system is experiencing severe stresses, which, if sustained, will be lethal to most macroscopic biota.

2.2 Sediment trapping

Dams are highly efficient at retaining sediments (Donald et al., 2015; Garnier et al., 2005; Kunz et al., 2011). As rivers approach reservoirs, the flow velocity slows and loses the potential to slide and bounce along sand and gravel, while lost turbulence allows finer sediments to fall out of suspension. Blockage of sediments and coarse material drives two related impact pathways. The first is physical, stemming from the loss of river sediments and bedload that are critical to maintaining the structure of downstream ecosystems (Kondolf, 1997). The second is chemical; the loss of sediment-bound nutrients causes oligotrophication of downstream ecosystems including floodplains and deltas (Van Cappellen and Maavara, 2016).

2.2.1 Altered habitat

The most proximate impact of sediment starvation is the enhancement of erosion downstream of dams from outflows causing channel incision that can degrade within-channel habitats for macroinvertebrates and fish (Kondolf, 1997). Impacts also reach adjacent and distant ecosystems such as floodplains and deltas, which almost universally depend upon rivers to deliver sediments and nutrients to maintain habitat quality and productivity. In addition to sediment/nutrient trapping, dams also dampen seasonal hydrologic peaks, reducing overbank flooding of downstream river reaches. The combination of these two dam effects leads to a major reduction in the delivery of nutrients to floodplains, which represents a fundamental disruption of the flood pulse, affecting the ecological functioning of floodplains (Junk et al., 1989).

River deltas also rely on sediment delivered by floods and damming has led to widespread loss of delta habitats (Giosan et al., 2014). Sediment delivery to the Mekong Delta has already been halved and could drop to 4 % of baseline if all planned dams for the catchment are constructed (Kondolf et al., 2014a). Elsewhere in the tropics, dam construction has been associated with the loss of mangrove habitat, such as at the Volta estuary in Ghana (Rubin et al., 1999). The morphology of the lower Zambezi's floodplains and delta were dramatically transformed by reduced sediment loads associated with the Cahora Bassa megadam in Mozambique (Davies et al., 2001). With diminished sediment delivery and enhanced erosion from rising sea levels, the future of many coastal deltas is precarious, as most of the world's medium and large deltas are not accumulating sediment fast enough to stay above water over the coming century (Giosan et al., 2014).

2.2.2 Oligotrophication

Although the densely populated and industrialized watersheds of the world typically suffer from eutrophication, dam-induced oligotrophication, through sediment and nutrient trapping, can also severely alter the ecological functioning of rivers and their floodplains, deltas and coastal waters. Globally, 12 % to 17 % of global river phosphorus load is trapped behind dams (Maavara et al., 2015); but in specific locations, trapping efficiency can be greater than 90 %, such as at Kariba Dam on the Zambezi River (Kunz et al., 2011) and the Aswan Dam on the Nile (Giosan et al., 2014). Such extreme losses of sediments and nutrients can cause serious acute impacts to downstream ecosystems, though examples are relatively scarce because predam baseline data are not often available.

Most of the best-documented examples of impacts stemming from oligotrophication are from temperate catchments with important and carefully monitored fisheries. For example damming led to the collapse of a valuable salmon fishery in Kootenay Lake, British Columbia, Canada, through oligotrophication (Ashley et al., 1997). The fishery was eventually restored through artificial nutrient additions. Oligotrophication may impose similar ecological impacts in tropical contexts, such as in southern Brazil where an increase in water clarity following the closure of the Eng. Sérgio Motta Dam (Porto Primavera Dam) was associated with a shift in fish communities (Granzotti et al., 2018). Impacts have been perhaps most dramatic in the eastern Mediterranean following the closure of the Aswan Dam. The Lake Nasser reservoir, following its closure in 1969, began capturing the totality of the Nile's famously sediment-rich floodwaters, including some 130 million tons of sediment that had previously reached the Mediterranean Sea. In the subsequent years there was a 95 % drop in phytoplankton biomass and an 80 % drop in fish landings (Halim, 1991). With dams driving rivers toward oligotrophy, and land-use changes such as deforestation and agricultural intensification, causing eutrophication, globally most rivers face some significant change to trophic state.

2.2.3 Elemental ratios

The attention to phosphorus and nitrogen can obscure the importance of other nutrients and their ratios. The element silicon (Si), which is also efficiently sequestered within reservoirs, is an essential nutrient for certain types of phytoplankton. The simultaneous eutrophication and damming of many watersheds has led to decreases in Si to nitrogen ratios, which tends to favor nonsiliceous species over diatoms (Turner et al., 1998). In the river Danube efficient trapping of Si in reservoirs over several decades led to a shift in Black Sea phytoplankton communities (Humborg et al., 1997), coinciding with a crash in an important and productive fishery (Tolmazin, 1985). Turner et al. (1998) document a similar phenomenon at lower latitude in the Mississippi Delta. Decreases in Si loading led to a drop in the abundance of copepods and diatoms relative to the total meso-zooplankton population in the Gulf of Mexico (Turner et al., 1998). These community shifts may have important implications for coastal and estuarine fish communities and the emergence of potential harmful algal blooms.

2.3 Reversibility and propagation of impacts

One way to think of the scope of dam impacts on water quality is in terms of how reversible perturbations to each variable may be. Sediment trapped by a dam may be irreversibly lost from a river and even unregulated downstream tributaries are unlikely to compensate. Temperature and oxygen impacts of dams, in contrast, will happen gradually through exchange with the atmosphere as the river flows. The speed of recovery will depend upon river depth, surface areas, turbulence and other factors that may provide input to predictive models (Langbein and Durum, 1967). Field data from subtropical Australia and tropical Malaysia suggest that, in practice, hypoxia can extend to dozens or hundreds of kilometers downstream of dam walls (Walker et al., 1978; Wera et al., 2019). Where reaeration measures are incorporated into dam operations, hypoxia can be mitigated immediately or within a few kilometers, as was the case in Tennessee, USA (Higgins and Brock, 1999). A study in Colorado, USA, found that thermal effects could be detected for hundreds of kilometers downstream (Holden and Stalnaker, 1975). Regardless of the type of impact, it is clear that downstream tributaries play an important role in returning rivers to conditions that are more “natural” by providing a source of sediment and flow of more appropriate water quality. Water quality impacts of dams are therefore likely to increase and become less reversible when chains of dams are built along the same river channel or on multiple tributaries of a catchment network.

Because the chemical changes in hypoxia and altered thermal regimes both stem from the physical process of reservoir stratification, understanding a reservoir's mixing behavior is an important first step toward predicting the likelihood of water quality impacts. Unfortunately, there exists ambiguity and misinformation in the literature about the mixing behavior of low-latitude reservoirs. To resolve the potential confusion, we review literature on the stratification behavior of tropical water bodies and then conduct an analysis of stratification behavior of the 54 most-voluminous low-latitude reservoirs.

3.1 Stratification in the tropics

For at least one authority on tropical limnology, the fundamental stratification behavior of tropical lakes and reservoirs is clear. Lewis (2000) states that “Tropical lakes are fundamentally warm monomictic …” with only the shallowest failing to stratify at least seasonally, and that periods of destratification are typically predictable events coinciding with cool, rainy and/or windy seasons. Yet, there exists confusion in the literature. For example, the World Commission on Large Dams' technical report states that stratification in low-latitude reservoirs is “uncommon” (McCartney et al., 2000). The authors provide no source supporting this statement, but the conclusion likely stems from the 70-year-old landmark lake classification system (Hutchinson and Loffler, 1956), which, based on very limited field data from equatorial regions, gives the impression that tropical lakes are predominately either oligomictic (mixing irregularly) or polymictic (mixing many times per year). The idea that low-latitude water bodies are fundamentally unpredictable or aseasonal, as well as Hutchinson and Loffler's (1956) approach of classifying lakes without morphometric information critical to understanding lake stability (Boehrer and Schultze, 2008), has been criticized repeatedly over subsequent decades as additional tropical lake studies have been published (Lewis, 1983, 2000, 1973, 1996). And yet, the original misleading classification diagram continues to be faithfully reproduced in contemporary limnology text books (Bengtsson et al., 2012; Wetzel, 2001). Since much of the water quality challenges associated with damming develop from the thermal and/or chemical stratification of reservoirs, we take a critical look at the issue of whether low-latitude reservoirs are likely to stratify predictably for long periods.

3.2 The largest low-latitude reservoirs

To assess the prevalence of prolonged reservoir stratification periods that could affect water quality, we reviewed and synthesized information on the 54 most-voluminous low-latitude reservoirs. Through literature searches, we found descriptions of mixing behavior for 32 of the 54. Authors described nearly all as “monomictic” (having a single well-mixed season, punctuated by a season of stratification). One of these reservoirs was described as meromictic (having a deep layer that does not typically intermix with surface waters) (Zhang et al., 2015). The review indicates that 30 reservoirs stratify regularly for seasons of several months and thus could experience the associated chemical and ecological water quality issues, such as thermal alterations and hypoxia. The two exceptions are Brazilian reservoirs, Três Irmãos and Ilha Solteira, described by Padisak et al. (2000) to be “mostly polymitic” (mixing many times per year). On further investigation, this classification does not appear to be based on direct observations but is a rather general statement of regional reservoir mixing behavior (see Supplement).

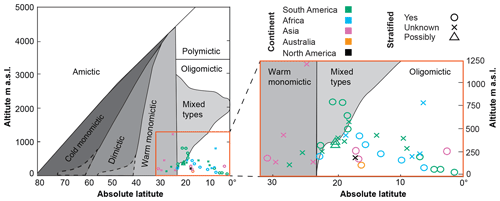

We compared our binary stratification classification based on available literature to the results of applying reservoir data to three existing stratification classification schemes. First, we consider the classic Hutchinson and Loffler (1956) classification diagram based on altitude and latitude. Second, we plot the data onto a revised classification diagram for tropical lakes proposed by Lewis (2000) based on reservoir morphometry. Finally we apply the concept of densimetric Froude number which can be used to predict reservoir stratification behavior (Parker et al., 1975) based on morphometry and discharge.

The Hutchinson and Loffler (1956) classification is meant to be applied to “deep” lakes and therefore is not useful for discriminating between stratifying and nonstratifying reservoirs based on depth. It does suggest that all sufficiently deep reservoirs (except those above 3500 m altitude) should stratify. Most of the reservoirs in our data set fall into an “oligomictic” zone, indicating irregular mixing (Fig. 3) when available literature suggests that most would be better described as monomictic, with a predictable season of deeper mixing. This finding reaffirms one of the long-running criticisms of this classification scheme: its overemphasis on oligomixis (Lewis, 1983).

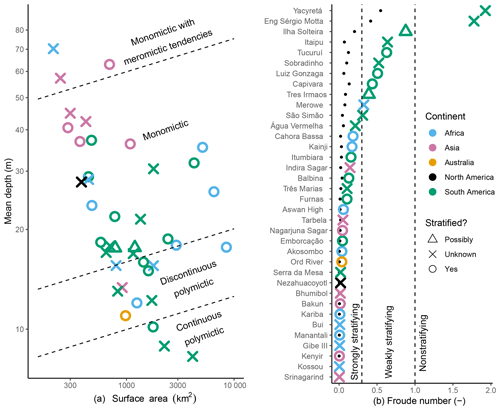

We found that the Lewis (2000) classification system for tropical lakes correctly identified most of the reservoirs in our data set as monomictic; however, six relatively shallow reservoirs known to exhibit seasonal stratification were misclassified into polymictic categories (Fig. 4a). Five of these six lie within a zone labeled “discontinuous polymictic,” which refers to lakes that do not mix on a daily basis, but mix deeply more often than once per year. The literature suggests that these lakes would be better described as “monomictic.” We should note that Lewis's (2000) goals in generating this diagram were to improve upon the Hutchinson and Loffler (1956) diagram for low-latitude regions and to develop a classification system that could be applied to shallow lakes. Lewis (2000) does not mathematically define the boundaries of difference and describes them as “approximate” based on his expert knowledge, so it is not terribly surprising that there appears to be some misclassifications.

Figure 3The 54 most-voluminous low-latitude reservoirs overlaid onto a lake classification diagram (redrawn from Hutchinson and Loffler, 1956).

Figure 4Reservoir morphometry and stratification behavior. (a) Relationships between area and depth for 40 of the 54 world's most-voluminous reservoirs located below ±35∘ latitude. Data are from the International Commission on Large Dams (https://www.icold-cigb.net/, last access: 1 August 2018) (we excluded 14 reservoirs because of missing surface area data). Stratification behavior classification is synthesized from literature: circle symbols indicate that the reservoir has an extended, predictable season of stratification and/or mixes deeply no more than once per year; triangle symbols refer to two Brazilian reservoirs that authorities suggest are likely to be polymictic, but for which no direct observations exist (see Tundisi, 1990; Padisak, 2000); for reservoirs indicated by cross symbols, no published information on stratification behavior appears in literature searches. Dashed lines and classification labels are approximations proposed by Lewis (2000). (b) Reservoirs sorted by densimetric Froude number, which is a function of reservoir depth, length, volume and discharge (Parker et al., 1975). The vertical dashed lines at Fr =1 and Fr =0.3 indicate the expected boundaries between strongly, weakly and nonstratifying reservoirs (Orlob, 1983). Small dots represent Froude numbers if maximum depth (height of dam wall) is used instead of mean depth as suggested by Ledec and Quintero, 2003. Discharge data is from the Global Runoff Data Centre (https://www.bafg.de/GRDC, last access: 1 August 2018); five dams were excluded because of missing discharge data.

In a final stratification assessment, we compared the known mixing behavior from literature to calculations of densimetric Froude number (Fr) (see Supplement) for the 35 reservoirs for which discharge and surface area data are available (Fig. 4b). We calculated Fr using two different values for depth: first, using mean depth by dividing reservoir volume by area; and second using dam wall height as a proxy for maximum depth. While some authors have suggested that either value for depth can be used (Ledec and Quintero, 2003), our analysis suggests that this choice can have a strong impact on Fr calculations and interpretation. The ratio between mean and maximum depth within our data set ranges from 0.1 to 0.4 with a mean of 0.23. This means that all Fr values could be recalculated to be roughly one-quarter of their value based on mean depth. This is inconsequential for reservoirs with small Fr, but for those with large Fr it can lead to a shift across the classification thresholds of 0.3 and 1. For example, two reservoirs in our data set exceeded the threshold of Fr =1 to indicate nonstratifying behavior when using mean depth, but they drop down into the weakly stratifying category when maximum depth is used instead. Nine other reservoirs shift from weakly to strongly stratifying. So which value for Fr better reflects reality? It is worth considering that reservoirs are typically quite long and limnologists often break them down into subbasins, separating shallower arms closer to river inflows from deeper zones close to the dam wall. Use of maximum depth for Fr calculations probably better reflects stratification behavior at the dam wall, whereas average depth may better indicate behavior in shallower subbasins that are less likely to stratify strongly. Since the deepest part of a reservoir is at the dam wall and because stratification in this zone is the most relevant to downstream water quality, it is probably most appropriate to use maximum depth in Fr calculations. The two reservoirs described as polymictic by Tundisi (1990) and Padisak et al. (2000) fall into the intermediate category of weakly stratifying (when using mean depth), but three others within this zone are reported to exhibit strong stratification (Deus et al., 2013; Naliato et al., 2009; Selge and Gunkel, 2013). Better candidates for nonstratifying members of this reservoir data set are Yacyretá and Eng. Sérgio Motta; but unfortunately, we could find no description of their mixing behavior in the literature. A field study with depth profiles of these reservoirs could dispel this ambiguity and determine whether all of the largest low-latitude reservoirs stratify on a seasonal basis.

Overall, this exercise of calculating Fr for large low-latitude reservoirs seems to indicate that most, if not all, are likely to stratify. This is an important realization because it points to a significant probability for downstream water quality problems associated with deep-water releases. Furthermore, the bulk of evidence suggests that these reservoirs mix during a predictable season and not irregularly throughout the year or across years, indicating that under normal conditions these reservoirs should be able to stratify continuously for periods of at least a few months.

4.1 Environmental flows

The most developed and implemented approach (or collection of approaches; reviewed by Tharme, 2003) for the mitigation of dam impacts is the environmental flow (eflow), which seeks to adjust dam releases to mimic natural hydrologic patterns. On a seasonal scale, large dams often homogenize the downstream discharge regime. An eflow approach to reservoir management could implement a simulated flood period by releasing some reservoir storage waters during the appropriate season. Although the eflow approach has traditionally focused on the mitigation of ecological problems stemming from disrupted hydrologic regimes, there is a growing realization that water quality (variables such as water temperature, pollutants, nutrients, organic matter, sediments, dissolved oxygen) must be incorporated into the framework (Olden and Naiman, 2010; Rolls et al., 2013). There is already some evidence that eflows successfully improve water quality in practice. In the Tennessee valley, the incorporation of eflows into dam management improved downstream dissolved oxygen (DO) and macroinvertebrate richness (Bednařík et al., 2017). Eflows have also been celebrated for preventing cyanobacteria blooms that had once plagued an estuary in Portugal (Chícharo et al., 2006). These examples illustrate the potential for eflows to solve some water quality impacts created by dams.

Unfortunately, eflows alone will be insufficient in many contexts. For one, flow regulation cannot address the issue of sediment and nutrient trapping without some sort of coupling to a sediment flushing strategy. Second, the issues of oxygen and thermal pollution often persist under eflow scenarios when there is reservoir stratification. Even if eflows effectively simulate the natural hydrologic regime, there is no reason why this should solve water quality problems as long as the water intake position is below the depth of the reservoir thermocline and residence time is not significantly changed. The solution to hypoxic, cold water is not simply more of it; but rather engineers must modify intakes to draw a more desirable water source, or destratification must be achieved. To address the problems of aeration and cold-water pollution, dam managers turn to outflow modification strategies or destratification.

4.2 Aeration

Hypoxia of reservoir tail waters is a common problem imposed by dams. As a result, various management methods for controlling dissolved oxygen content in outflows exist, ranging in cost-effectiveness depending on the characteristics of the dam in question (reviewed by Beutel and Horne, 1999). Options include turbine venting, turbine air injection, surface water pumps, oxygen injection and aerating weirs. As the issue of dam-induced hypoxia has been recognized for many decades, most modern dams incorporate some sort of oxygenation design elements. Where rules strictly regulate dissolved oxygen in the Tennessee Valley, United States, hydropower operators continuously monitor DO in large dam outflows. DO levels are managed by hydropower plant personnel specializing in water quality, aeration and reservoir operations (Higgins and Brock, 1999). However, dams do not always function as designed, especially older constructions in regions with less regulation and oversight; and in such cases, retrofits or adjusted management strategies may be effective. For example, Kunz et al. (2013) suggest that hypoxic releases from Zambia's Itezhi-Tezhi Dam (built in the 1970s) could be mitigated by releasing a mixture of hypolimnetic and epilimnetic waters. This proposed action could help protect the valuable fisheries of the downstream Kafue Flats floodplain.

4.3 Thermal buffering

The problem of cold-water pollution, much like hypoxia, is driven by reservoir stratification and thus can be addressed by similar management strategies (Olden and Naiman, 2010). Most common multilevel intakes are designed so that outflows are derived from an appropriate mixture of epi- and hypolimnetic waters to meet a desirable downstream temperature threshold (Price and Meyer, 1992). A remaining challenge is a lack of understanding of what the thermal requirements are for a given river system. Rivers-Moore et al. (2013) propose a method for generating temperature thresholds for South African rivers based on time series data from dozens of monitoring stations. Unfortunately, basic monitoring data for many regions of the tropics is sparse and quite fragmentary, which further complicates the establishment of ecological thermal requirements.

4.4 Sediment manipulation

Sediment trapping by dams is not only a water quality problem, as we have discussed, but also a challenge for dam management because it causes a loss of reservoir capacity over time. Thus, in order to maintain generation capacity, many managers of hydropower dams implement sediment strategies, which include the flushing of sediments through spillways or sediment bypass systems. A recent review of sediment management practices at hydropower reservoirs provides a summary of techniques in use and evaluates their advantages and limitations, including operations and cost considerations as well as ecological impacts (Hauer et al., 2018). Sediment management can be implemented at the catchment scale, within the reservoir itself or at the dam wall. Sediment bypass systems are regarded as the most comprehensive solution, but may be expensive or infeasible because of reservoir dimensions, or cause more ecological harm than they alleviate (Graf et al., 2016; Sutherland et al., 2002).

Typically, sediment flushing is practiced in an episodic manner, creating a regime of sediment famine punctuated by intense gluts that are not so much a feast, but rather bury downstream ecosystems alive (Kondolf et al., 2014b). Environmentally optimized sediment flushes show potential for minimizing risks where these are feasible, but are rare in practice. A limitation is that not all dams are designed to allow for sediment flushes, or reservoir characteristics imposed by local geomorphology render them impractical. Furthermore, no amount of flushing is able to transport coarser bedload material (i.e., gravel or larger) downstream. To compensate for lost bedload and sediments, some managers have made the expensive effort of depositing loose gravel piles onto river margins so that they can gradually be incorporated into the downstream sediment pool as sediment-starved water inevitably cuts into banks (Kondolf et al., 2014b).

An alternative to sediment management at the site of the dam is the restoration of sediment-starved floodplain or delta wetlands, but this process is likely to be prohibitively expensive in most if not all cases. Restoration of drowning Mississippi River Delta in Louisiana, United States, are estimated to cost USD 0.5 to 1.5 billion per year for 50 years (Giosan et al., 2014).

5.1 More data from low latitudes

It is telling that, in this review focused on low latitudes, we often had to cite case studies from the temperate zone. For example, we were able to locate one study describing ecological impacts stemming from dam-driven oligotrophication at low latitudes (Granzotti et al., 2018). The simple fact is that most of the tropics and subtropics lie far from the most active research centers and there has been a corresponding gap in limnological investigations. Europe and the United States have 1.5 to 4 measurement stations for water quality per 10 000 km2 of river basin on average. Monitoring density is 100 times smaller in Africa (UNEP, 2016). Our review found that of the 54 most-voluminous low-latitude reservoirs, 22 (41 %) have yet to be the subject of a basic limnological study to classify their mixing behavior. Further efforts to monitor river water quality and study aquatic ecology in regulated low-latitude catchments are needed to elucidate the blind spots that this review has identified.

5.2 Studies of small reservoirs

Compared with larger dams, the ecological impact of small hydropower dam systems have been poorly documented. Although small dams are likely to have smaller local impacts than large dams, the scaling of impacts is not necessarily proportional. That is, social and environmental impacts related to power generation may be greater for small dams than large reservoirs (Fencl et al., 2015). Generalizations about small hydroelectric systems are difficult because they come in so many different forms and designs. For example, nondiversion run-of-river systems will trap far less sediment than large dams, and those that do not create a deep reservoir are not subject to stratification-related effects. Thus, it is tempting to conclude that small-scale hydro will have minimal water quality impacts, but without a systematic assessment it is impossible to make a fair comparison with large-scale hydropower (Premalatha et al., 2014). Our analysis is biased towards large systems for the practical reason that larger systems are much more likely to be described in databases and studied by limnologists. Future studies on the environmental impacts of small hydropower systems would be valuable.

5.3 Better predictions of reservoir stratification behavior

Our predictions of reservoir stratification behavior based upon morphometric and hydrologic data, while helpful for understanding broad patterns of behavior, are not terribly useful for understanding water quality impacts of a specific planned dam. It would be much more useful to be able to reliably predict the depth of the thermocline, which could be compared with the depth of water intakes to assess the likelihood of discharging hypolimnetic water downstream. Existing modeling approaches to predicting mixing behavior fall into two categories: mathematically complex deterministic or process-based models and simpler statistical or semiempirical models. Deterministic models holistically simulate many aspects of lake functioning, including the capability to predict changes in water quality driven by biogeochemical processes. Researchers have used such tools to quantify impacts of reservoirs on downstream ecosystems (Kunz et al., 2013; Weber et al., 2017), but they require a large amount of in situ observational data, which is often lacking for low-latitude reservoirs. This data dependence also makes them unsuitable for simulating hypothetical reservoirs that are in a planning stage and thus they cannot inform dam environmental impact statements. A promising semiempirical approach was recently published, proposing a `generalized scaling' for predicting mixing depth based on lake length, water transparency and Monin–Obukhov length, which is a function of radiation and wind (Kirillin and Shatwell, 2016). This model was tuned for and validated against a data set consisting of mostly temperate zone lakes, so it is unclear how well it can be applied to low-latitude systems. If this or another semi-empirical model can be refined to make predictions about the stratification behavior of hypothetical reservoirs being planned, it could provide valuable information about potential risks of water quality impacts on ecosystems of future dams.

We have found that damming threatens the water quality of river systems throughout the world's lower latitudes, a fact that is not always recognized in broader critiques of large dam projects. Water quality impacts may propagate for hundreds of kilometers downstream of dams and therefore may be a cryptic source of environmental degradation, destroying ecosystem services provided to riparian communities. Unfortunately, a lack of predam data on low-latitude river chemistry and ecology makes it a challenge to objectively quantify such impacts. Building the capacity of developing countries at low latitudes to monitor water quality of their river systems should be a priority.

Seasonal stratification of low-latitude reservoirs is ubiquitous and is expected to occur in essentially any large tropical reservoir. This highlights the risk for low-latitude reservoirs to discharge cooler and anoxic hypolimnetic waters to downstream rivers depending on the depth of the thermocline relative to turbine intakes. Of course, in the absence of a randomized sampling study it is difficult to assess whether the anecdotes we have identified are outliers or part of a more general widespread pattern. Further research could investigate how common these problems are and assess the geographic or design factors that contribute toward their occurrence.

It is difficult to assess which of the water quality impacts are most damaging for two reasons. First, dams impose many impacts simultaneously and it is often difficult to disentangle which imposed water quality change is driving an ecological response, or whether multiple stressors are acting synergistically. Second, to compare the relative importance of impacts requires a calculation of value which, as we have learned from the field of ecological economics (Costanza et al., 1997), will inevitably be controversial. It does appear that water quality effects, which can render river reaches uninhabitable because of anoxia and contribute to loss of floodplain and delta wetlands through sediment trapping, exert a greater environmental impact than dam disruption to connectivity, which only directly affects migratory species.

The mitigation of water quality impacts imposed by dams has been successful in places, but its implementation is dependent on environmental regulation and associated funding mechanisms, both of which are often limited in low-latitude settings. Environmental impact assessments and follow-up monitoring should be required for all large dams. The feasibility of management actions depends upon the dam design and local geomorphology. Thus, solutions are typically custom-tailored to the context of a specific dam. We expect that as the dam boom progresses, simultaneous competing water uses will exacerbate the degradation of water quality in low-latitude river systems. Further limnological studies of data-poor regions combined with the development and validations of water quality models will greatly increase our capacity to identify and mitigate this looming water resource challenge.

All data used to produce Figs. 1, 3 and 4 are available in the ETH Zurich Research Collection (https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000310656; Winton et al., 2018). The data on reservoir size and morphometry are available in the World Register of Dams database maintained by the International Commission on Large Dams, which can be accessed (for a fee) at https://www.icold-cigb.org/ (International Commission on Large Dams, 2018). The data on discharge is available in the Global Runoff Data Centre, 56068 Koblenz, Germany, accessible at https://www.bafg.de/GRDC/ (Bundesantalt für Gewässerkunde, 2018).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-16-1657-2019-supplement.

RSW, BW and EC developed the paper concept. RSW and EC extracted the data for analysis. BW provided mentoring and oversight. RSW produced the figures. RSW wrote the original draft. All authors provided critical review and revisions.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This work is supported by the Decision Analytic Framework to explore the water-energy-food Nexus in complex transboundary water resource systems of fast developing countries (DAFNE) project, which has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 690268. The authors thank Luzia Fuchs for providing graphical support for the creation of Fig. 3. Marie-Sophie Maier provided helpful feedback on figure aesthetics. Comments from two anonymous reviewers greatly improved the manuscript.

This paper was edited by Tom J. Battin and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Anderson, E. P., Jenkins, C. N., Heilpern, S., Maldonado-ocampo, J. A., Carvajal-vallejos, F. M., Encalada, A. C., and Rivadeneira, J. F.: Fragmentation of Andes-to-Amazon connectivity by hydropower dams, Sci. Adv., 4, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aao1642, 2018.

Ashley, K., Thompson, L. C., Lasenby, D. C., Mceachern, L., Smokorowski, K. E., and Sebastian, D.: Restoration of an interior lake ecosystem: The kootenay lake fertilization experiment, Water Qual. Res. J. Can., 32, 295–323, 1997.

Bednařík, A., Blaser, M., Matoušů, A., Hekera, P., and Rulík, M.: Effect of weir impoundments on methane dynamics in a river, Sci. Total Environ., 584–585, 164–174, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.163, 2017.

Bengtsson, L., Herschy, R. W., and Fairbridge, R. W.: Encyclopedia of lakes and reservoirs: geography, geology, hydrology and paleolimnology, Springer, 2012.

Beutel, M. W. and Horne, A. J.: A review of the effects of hypolimnetic oxygenation on lake and reservoir water quality, Lake Reserv. Manage., 15, 285–297, https://doi.org/10.1080/07438149909354124, 1999.

Boehrer, B. and Schultze, M.: Stratification of lakes, Rev. Geophys., 46, RG2005, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006RG000210, 2008.

Bundesantalt für Gewässerkunde: Global Runoff Data Centre, available at: https://www.bafg.de/GRDC/, last access: 1 August 2018.

Carpenter, S. R., Caraco, N. F., Correll, D. L., Howarth, R. W., Sharpley, A. N., and Smith, V. H.: Nonpoint pollution of surface waters with phosphorus and nitrogen, Ecol. Appl., 8, 559–568, https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(1998)008[0559:NPOSWW]2.0.CO;2, 1998.

Chícharo, L., Chícharo, M. A., and Ben-Hamadou, R.: Use of a hydrotechnical infrastructure (Alqueva Dam) to regulate planktonic assemblages in the Guadiana estuary: Basis for sustainable water and ecosystem services management, Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci., 70, 3–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2006.05.039, 2006.

Coble, D. W.: Fish Populations in Relation to Dissolved Oxygen in the Wisconsin River, Trans. Am. Fish. Soc., 111, 612–623, https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8659(1982)111<612:FPIRTD>2.0.CO;2, 1982.

Costanza, R., d'Arge, R., de Groot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., Limburg, K., Naeem, S., O'Neill, R. V., Paruelo, J., Raskin, R. G., Sutton, P., and van den Belt, M.: The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital, Nature, 387, 253–260, https://doi.org/10.1038/387253a0, 1997.

Coutant, C. C.: Thermal preference: when does an asset become a liability?, Environ. Biol. Fish., 18, 161–172, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00000356, 1987.

Davies, B. R., Beilfuss, R. D., and Thoms, M. C.: Cahora Bassa retrospective, 1974–1997: effects of flow regulation on the lower Zambezi River, Verhandlungen des Int. Verein Limnol., 27, 2149–2157, 2001.

Deemer, B. R., Harrison, J. A., Li, S., Beaulieu, J. J., Delsontro, T., Barros, N., Bezerra-Neto, J. F., Powers, S. M., Dos Santos, M. A., and Vonk, J. A.: Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Reservoir Water Surfaces: A New Global Synthesis Manuscript, Bioscience, 66, 949–964, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biw117, 2016.

Delsontro, T., Kunz, M. J., Wuest, A., Wehrli, B., and Senn, D. B.: Spatial Heteogeneity of Methane Ebullition in a Large Tropical Reservoir, Environ. Sci. Technol., 45, 9866–9873, 2011.

Deus, R., Brito, D., Mateus, M., Kenov, I., Fornaro, A., Neves, R., and Alves, C. N.: Impact evaluation of a pisciculture in the Tucuruí reservoir (Pará, Brazil) using a two-dimensional water quality model, J. Hydrol., 487, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2013.01.022, 2013.

Donald, D. B., Parker, B. R., Davies, J. M., and Leavitt, P. R.: Nutrient sequestration in the Lake Winnipeg watershed, J. Great Lakes Res., 41, 630–642, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jglr.2015.03.007, 2015.

Eady, B. R., Rivers-Moore, N. A., and Hill, T. R.: Relationship between water temperature predictability and aquatic macroinvertebrate assemblages in two South African streams, African J. Aquat. Sci., 38, 163–174, https://doi.org/10.2989/16085914.2012.763110, 2013.

Fencl, J. S., Mather, M. E., Costigan, K. H., and Daniels, M. D.: How Big of an Effect Do Small Dams Have?? Using Geomorphological Footprints to Quantify Spatial Impact of Low-Head Dams and Identify Patterns of Across-Dam Variation, 10, e0141210, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141210, 2015.

Friedl, G. and Wüest, A.: Disrupting biogeochemical cycles – Consequences of damming, Aquat. Sci., 64, 55–65, 2002.

Garnier, J., Némery, J., Billen, G., and Théry, S.: Nutrient dynamics and control of eutrophication in the Marne River system: Modelling the role of exchangeable phosphorus, J. Hydrol., 304, 397–412, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2004.07.040, 2005.

Gibson, L., Wilman, E. N., and Laurance, W. F.: How Green is “Green” Energy?, Trends Ecol. Evol., 32, 922–935, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2017.09.007, 2017.

Giosan, L., Syvitski, J., Constantinescu, S., and Day, J.: Climate change: Protect the world's deltas, Nature, 516, 31–33, https://doi.org/10.1038/516031a, 2014.

Graf, W., Leitner, P., Hanetseder, I., Ittner, L. D., Dossi, F., and Hauer, C.: Ecological degradation of a meandering river by local channelization effects: a case study in an Austrian lowland river, Hydrobiologia, 772, 145–160, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-016-2653-6, 2016.

Granzotti, R. V., Miranda, L. E., Agostinho, A. A., and Gomes, L. C.: Downstream impacts of dams: shifts in benthic invertivorous fish assemblages, Aquat. Sci., 80, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-018-0579-y, 2018.

Grizzle, J. M.: Effects of hypolimnetic discharge on fish health below a reservoir, Trans. Am. Fish. Soc., 110, 29–43, https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8659(1981)110<29:EOHDOF>2.0.CO;2, 1981.

Halim, Y.: The impact of human alteration of the hydrological cycle on ocean margins, in Ocean margin processes in global change, edited by: Mantoura, R. F. C., Martin, J.-M., and Wollast, R., 301–327, John Wiley & Sons, 1991.

Hauer, C., Wagner, B., Aigner, J., Holzapfel, P., Flödl, P., Liedermann, M., Tritthart, M., Sindelar, C., Pulg, U., Klösch, M., Haimann, M., Donnum, B. O., Stickler, M., and Habersack, H.: State of the art, shortcomings and future challenges for a sustainable sediment management in hydropower: A review, Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev., 98, 40–55, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.08.031, 2018.

Haxton, T. J. and Findlay, C. S.: Meta-analysis of the impacts of water management on aquatic communities, Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci., 65, 437–447, https://doi.org/10.1139/f07-175, 2008.

Higgins, J. M. and Brock, W. G.: Overview of Reservoir Release Improvements at 20 TVA Dams, J. Energ. Eng., 125, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9402(1999)125:1(1), 1999.

Hill, L. G.: Oxygen Preference in the Spring Cavefish, Chologaster agassizi Loren, Trans. Am. Fish. Soc., 97, 448–454, https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8659(1968)97[448:OPITSC]2.0.CO;2, 1968.

Holden, P. B. and Stalnaker, C. B.: Distribution and abundance of mainstream fishes of the middle and upper Colorado River basins, 1967–1973, Trans. Am. Fish. Soc., 104, 217–231, https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8659(1975)104<217:DAAOMF>2.0.CO;2, 1975.

Humborg, C., Ittekkot, V., Cociasu, A., and Bodungen, B. V.: Effect of Danube River dam on Black Sea biogeochemistry and ecosystem structure, Nature, 386, 385–388, https://doi.org/10.1038/386385a0, 1997.

Hutchinson, G. E. and Loffler, H.: The thermal stratification of lakes, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 42, 84–86, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.42.2.84, 1956.

International Commission on Large Dams: World Register of Dams, available at: https://www.icold-cigb.org/GB/world_register/world_register_of_dams.asp, last access: 1 August 2018.

Junk, W. J., Bayley, P. B., and Sparks, R. E.: The flood-pulse concept in river-floodplain systems, Proc. Int. Large River Symp. Can. Spec. Publ. Fish. Aquat. Sci., 106, available at: http://www.royalcommission.vic.gov.au/finaldocuments/summary/PF/VBRC_Summary_PF.pdf (last access: 18 April 2019), 1989.

Kilham, P. and Kilham, S. S.: Endless summer: internal loading processes dominate nutrient cycling in tropical lakes, Freshwater Biol., 23, 379–389, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.1990.tb00280.x, 1990.

King, J., Cambray, J. A., and Impson, N. D.: Linked effects of dam-released floods and water temperature on spawning of the Clanwilliam yellowfish Barbus capensis, Hydrobiologia, 384, 245–265, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003481524320, 1998.

Kingsford, R. T. and Thomas, R. F.: Destruction of wetlands and waterbird populations by dams and irrigation on the Murrumbidgee River in Arid Australia, Environ. Manage., 34, 383–396, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-004-0250-3, 2004.

Kirillin, G. and Shatwell, T.: Generalized scaling of seasonal thermal stratification in lakes, Earth-Sci. Rev., 161, 179–190, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.08.008, 2016.

Kondolf, G. M.: Hungry water: Effects of dams and gravel mining on river channels, Environ. Manage., 21, 533–551, https://doi.org/10.1007/s002679900048, 1997.

Kondolf, G. M., Rubin, Z. K., and Minear, J. T.: Dams on the Mekong: Cumulative sediment starvation, Water Resour. Res., 50, 5158–5169, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013WR014651, 2014a.

Kondolf, G. M., Gao, Y., Annandale, G. W., Morris, G. L., Jiang, E., Zhang, J., Cao, Y., Carling, P., Fu, K., Guo, Q., Hotchkiss, R., Peteuil, C., Sumi, T., Wang, H.-W., Wang, Z., Wei, Z., Wu, B., Wu, C., and Yang, C. T.: Sustainable sediment management in reservoirs and regulated rivers: Experiences from five continents, Earths Futur., 2, 256–280, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013EF000184, 2014b.

Kunz, M. J., Wüest, A., Wehrli, B., Landert, J., and Senn, D. B.: Impact of a large tropical reservoir on riverine transport of sediment, carbon, and nutrients to downstream wetlands, Water Resour. Res., 47, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011WR010996, 2011.

Kunz, M. J., Senn, D. B., Wehrli, B., Mwelwa, E. M., and Wüest, A.: Optimizing turbine withdrawal from a tropical reservoir for improved water quality in downstream wetlands, Water Resour. Res., 49, 5570–5584, https://doi.org/10.1002/wrcr.20358, 2013.

Langbein, W. and Durum, W.: The aeration capacity of streams, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Geological Survey, https://doi.org/10.3133/cir542, 1967.

Ledec, G. and Quintero, J. D.: Good dams and bad dams: environmental criteria for site selection of hydroelectric projects, Lat. Am. Caribb. Reg. Dev. Work. Pap. No. 16, 21, available at: http://large.stanford.edu/courses/2011/ph240/mina2/docs/Good_and_Bad_Dams_WP16.pdf (last access: 18 April 2019), 2003.

Lewis, W. M.: A Revised Classification of Lakes Based on Mixing, Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci., 40, 1779–1787, https://doi.org/10.1139/f83-207, 1983.

Lewis, W. M.: Basis for the Protection and Management of Tropical Lakes, Lake Reserv. Manage., 5, 35–48, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1770.2000.00091.x, 2000.

Lewis, W. M. J.: Thermal Regime Implications for Tropical Lakes, Limnol. Oceanogr., 18, 200–217, 1973.

Lewis, W. M. J.: Tropical lakes?: how latitude makes a difference, in: Perspectives in Tropical Limnology, edited by: Schiemer, F. and Boland, K. T., 43–64, SPB Academic Publishing, Amsterdam, 1996.

Maavara, T., Parsons, C. T., Ridenour, C., Stojanovic, S., Dürr, H. H., Powley, H. R., and Van Cappellen, P.: Global phosphorus retention by river damming, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 112, 15603–15608, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1511797112, 2015.

Magadza, C. H. D.: Environmental state of Lake Kariba and Zambezi River Valley: Lessons learned and not learned, Lake Reserv. Manage., 15, 167–192, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1770.2010.00438.x, 2010.

Marshall, B. E. and Junor, F. J. R.: The Decline of Salvinia-Molesta on Lake Kariba Zimbabwe, Hydrobiologia, 83, 477–484, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02187043, 1981.

McCartney, M. P., Sullivan, C., and Acreman, M. C.: Ecosystem Impacts of Large Dams, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources and United Nations Environmental Programme, 2000.

Mumba, M. and Thompson, J. R.: Hydrological and ecological impacts of dams on the Kafue Flats floodplain system, southern Zambia, Phys. Chem. Earth, 30, 442–447, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2005.06.009, 2005.

Naliato, D. A. D. O., Nogueira, M. G., Perbiche-neves, G., and Unesp, P.: Discharge pulses of hydroelectric dams and their effects in the downstream limnological conditions: a case study in a large tropical river (SE Brazil), Lake Reserv. Manage., 14, 301–314, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1770.2009.00414.x, 2009.

Nilsson, C. and Renofalt, B. M.: Linking flow regime and water quality in rivers: a challenge to adaptive catchment management, Ecol. Soc., 13, 18, 2008.

Nurnberg, G. K.: The prediction of internal phosphorus load in lakes with anoxic hypolimnia phosphorus not considered in the mass bal- sewage diversion Of six lakes, four showed model predicted, All the outliers had anoxic phorus concentration in anoxic Lake Sam- ma, Limnol. Oceanogr., 29, 111–124, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scr.2014.10.005, 1984.

Orlob, G. T.: Mathematical Modeling of Water Quality: Streams, Lakes and Reservoirs, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK, available from: http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/2144/ (last access: 18 April 2019), 1983.

O'Keeffe, J. H.: A Perspective on Training Methods Aimed at Building Local Capacity for the Assessment and Implementation of Environmental Flows in Rivers, Front. Environ. Sci., 6, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2018.00125, 2018.

Olden, J. D. and Naiman, R. J.: Incorporating thermal regimes into environmental flows assessments: Modifying dam operations to restore freshwater ecosystem integrity, Freshw. Biol., 55, 86–107, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2009.02179.x, 2010.

Padisák, J., Barbosa, F. A. R., Borbély, G., Borics, G., Chorus, I., Espindola, E. L. G., Heinze, R., Rocha, O., Törökné, A. K. and Vasas, G.: Phytoplankton composition, biodiversity and a pilot survey of toxic cyanoprokaryotes in a large cascading reservoir system (Tietê basin, Brazil), SIL Proceedings, 1922–2010, 27, 2734–2742, https://doi.org/10.1080/03680770.1998.11898164, 2000.

Parker, F. L., Benedict, B. A., and Tsai, C.: Evaluation of mathematical models for temperature prediction in deep reservoirs, National Envrionmental research center, US Environmental Protection Agency, Corvallis, Oregon, 1975.

Petts, G. E.: Water quality characteristics of regulated rivers, Prog. Phys. Geogr., 10, 492–516, https://doi.org/10.1177/030913338601000402, 1986.

Power, M. E., Dietrich, W. E., and Finlay, J. C.: Dams and Downstream Aquatic Biodiversity: Potential Food Web Consequences of Hydrologic and Geomorphic Change, Environ. Manage., 20, 887–895, 1996.

Preece, R. M. and Jones, H. A.: The effect of Keepit Dam on the temperature regime of the Namoi River, Australia, River Res. Appl., 18, 397–414, https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.686, 2002.

Premalatha, M., Abbasi, T., and Abbasi, S. A.: Science of the Total Environment A critical view on the eco-friendliness of small hydroelectric installations, Sci. Total Environ., 481, 638–643, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.11.047, 2014.

Price, R. E. and Meyer, E. B.: Water quality management for reservoirs and tailwaters: operational and structural water quality techniques, Vicksburg, Mississippi, USA, available at: https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a254184.pdf (last access: 18 April 2019), 1992.

Richter, B. D.: Re-thinking environmental flows: from allocations and reserves to sustainability boundaries, River Res. Appl., 30, https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.1320, 2009.

Rivers-Moore, N. A., Dallas, H. F., and Morris, C.: Towards setting environmental water temperature guidelines: A South African example, J. Environ. Manage., 128, 380–392, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.04.059, 2013.

Rolls, R. J., Growns, I. O., Khan, T. A., Wilson, G. G., Ellison, T. L., Prior, A., and Waring, C. C.: Fish recruitment in rivers with modified discharge depends on the interacting effects of flow and thermal regimes, Freshw. Biol., 58, 1804–1819, https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12169, 2013.

Rubin, J. A., Gordon, C., and Amatekpor, J. K.: Causes and consequences of mangrove deforestation in the Volta estuary, Ghana: Some recommendations for ecosystem rehabilitation, Mar. Pollut. Bull., 37, 441–449, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-326X(99)00073-9, 1999.

Sato, Y., Bazzoli, N., Rizzo, E., Boschi, M. B., and Miranda, M. O. T.: Influence of the Abaeté River on the reproductive success of the neotropical migratory teleost Prochilodus argenteus in the São Francisco River, downstream from the Três Marias Dam, southeastern Brazil, River Res. Appl., 21, 939–950, https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.859, 2005.

Selge, F. and Gunkel, G.: Water reservoirs: worldwide distribution, morphometric characteristics and thermal stratification processes, in: Sustainable Management of Water and Land in Semiarid Areas, edited by: Gunkel, G., Aleixo da Silva, J. A., and Sobral, M. d. C., 15–27, 2013.

Smith, L. L., Oseid, D. M., Kimball, G. L., and El-Kandelgy, S. M.: Toxicity of Hydrogen Sulfide to Various Life History Stages of Bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus), T. Am. Fish. Soc., 105, 442–449, https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8659(1976)105<442:TOHSTV>2.0.CO;2, 1976.

Smith, V. H.: Eutrophication of freshwater and coastal marine ecosystems a global problem, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 10, 126–139, https://doi.org/10.1065/espr2002.12.142, 2003.

Spoor, W. A.: Distribution of fingerling brook trout, Salvelinus fontinalis (Mitchill), in dissolved oxygen concentration gradients, J. Fish Biol., 36, 363–373, 1990.

Straskraba, M., Tundisi, J. G., and Duncan, A.: Comparative reservoir limnology and water quality management, Springer-Science+Business Media, 1993.

Sutherland, A. B., Meyer, J. L., and Gardiner, E. P.: Effects of land cover on sediment regime and fish assemblage structure in four southern Appalachian streams, Freshw. Biol., 47, 1791–1805, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2002.00927.x, 2002.

Tharme, R. E.: A global perspective on environmental flow assessment: Emerging trends in the development and application of environmental flow methodologies for rivers, River Res. Appl., 19, 397–441, https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.736, 2003.

Thurston, R. V, Russo, R. C., and Phillips, G. R.: Acute Toxicity of Ammonia to Fathead Minnows, T. Am. Fish. Soc., 112, 705–711, https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8659(1983)112<705:ATOATF>2.0.CO;2, 1983.

Todd, C. R., Ryan, T., Nicol, S. J., and Bearlin, A. R.: The impact of cold water releases on the critical period of post-spawning survival and its implications for Murray cod (Maccullochella peelii peelii): A case study of the Mitta Mitta River, southeastern Australia, River Res. Appl., 21, 1035–1052, https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.873, 2005.

Tolmazin, D.: Changing Coastal oceanography of the Black Sea. I: Northwestern Shelf, Prog. Oceanogr., 15, 217–276, https://doi.org/10.1016/0079-6611(85)90038-2, 1985.

Tundisi, J. G.: Distribuição espacial, seqência temporal e ciclo sazonal do fitoplâncton em represas: fatores limitantes e controladores, Rev. Bras. Biol., 50, 937–955, 1990.

Turner, R. E., Qureshi, N., Rabalais, N. N., Dortch, Q., Justic, D., Shaw, R. F., and Cope, J.: Fluctuating silicate:nitrate ratios and coastal plankton food webs, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 13048–13051, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.22.13048, 1998.

UNEP: A Snapshot of the World's Water Quality: Towards a Global Assessment, available at: http://www.unep.org/publications/ (last access: 18 April 2019), 2016.

Van Cappellen, P. and Maavara, T.: Rivers in the Anthropocene: Global scale modifications of riverine nutrient fluxes by damming, Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol., 16, 106–111, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecohyd.2016.04.001, 2016.

Vannote, R. L. and Sweeney, B. W.: Geographic Analysis of Thermal Equilibria: A Conceptual Model for Evaluating the Effect of Natural and Modified Thermal Regimes on Aquatic Insect Communities, Am. Nat., 115, 667–695, https://doi.org/10.1086/283591, 1980.

Walker, K. F., Hillman, T. J., and Williams, W. D.: Effects of impoundments on rivers: an Australian case study, SIL Proceedings, 1922–2010, 20, 1695–1701, https://doi.org/10.1080/03680770.1977.11896755, 1978.

Ward, J. V and Stanford, J. A.: Evolutionary Ecology of Aquatic Insects, Annu. Rev. Entomol., 97–117, 1982.

Weber, M., Rinke, K., Hipsey, M. R., and Boehrer, B.: Optimizing withdrawal from drinking water reservoirs to reduce downstream temperature pollution and reservoir hypoxia, J. Environ. Manage., 197, 96–105, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.03.020, 2017.

Wera, F., Ling, T., Nyanti, L., Sim, S., and Grinang, J.: Effects of opened and closed spillway operations of a large tropical hydroelectric dam on the water quality of the downstream river, Hindawi J. Chem., 2019.

Wetzel, R. G.: Limnology: lake and river ecosystems, Academic Press, 2001.

Winemiller, K. O., McIntyre, P. B., Castello, L., Fluet-Chouinard, E., Giarrizzo, T., Nam, S., Baird, I. G., Darwall, W., Lujan, N. K., Harrison, I., Stiassny, M. L. J., Silvano, R. A. M., Fitzgerald, D. B., Pelicice, F. M., Agostinho, A. A., Gomes, L. C., Albert, J. S., Baran, E., Petrere, M., Zarfl, C., Mulligan, M., Sullivan, J. P., Arantes, C. C., Sousa, L. M., Koning, A. A., Hoeinghaus, D. J., Sabaj, M., Lundberg, J. G., Armbruster, J., Thieme, M. L., Petry, P., Zuanon, J., Vilara, G. T., Snoeks, J., Ou, C., Rainboth, W., Pavanelli, C. S., Akama, A., van Soesbergen, A., and Saenz, L.: Balancing hydropower and biodiversity in the Amazon, Congo, and Mekong, Science, 351, 128–129, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac7082, 2016.

Winton, R. S., Calamita, E., and Wehrli, B.: Physical data for the 54 most voluminous low latitude reservoirs, https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000310656, 2018.

Young, W. C., Kent, D. H., and Whiteside, B. G.: The influence of a deep storage reservoir on the species diversity of benthic macroinvertebrate communities of the Guadalupe River, Texas J. Sci., 27, 213–224, 1976.

Zarfl, C., Lumsdon, A. E., Berlekamp, J., Tydecks, L., and Tockner, K.: A global boom in hydropower dam construction, Aquat. Sci., 77, 161–170, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-014-0377-0, 2014.

Zhang, L., Li, Q.-H., Huang, G.-J., Ou, T., Li, Y., Wu, D., Zhou, Q.-L., and Gao, T.-J.: Seasonal stratification and eutrophication characteristics of a deep reservoir, Longtan Reservoir in subtropical area of China, Huan Jing Ke Xue, 36, 438–47, available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26031068 (last access: 19 October 2018), 2015.