the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Mercury accumulation in leaves of different plant types – the significance of tissue age and specific leaf area

Jenny Klingberg

Michelle Nerentorp

Malin C. Broberg

Brigitte Nyirambangutse

John Munthe

Göran Wallin

Mercury, Hg, is one of the most problematic metals from an environmental perspective. To assess the problems caused by Hg in the environment, it is crucial to understand the processes of Hg biogeochemistry, but the exchange of Hg between the atmosphere and vegetation is not sufficiently well characterized. We explored the mercury concentration, [Hg], in foliage from a diverse set of plant types, locations and sampling periods to study whether there is a continuous accumulation of Hg in leaves and needles over time. Measurements of [Hg] were made for deciduous and conifer trees in Gothenburg, Sweden (botanical garden and city area), as well as for evergreen trees in Rwanda. In addition, data for wheat from an ozone experiment conducted at Östad, Sweden, were included. Conifer data were quantitatively compared with literature data. In every case where older foliage was directly compared with younger, [Hg] was higher in older tissue. Covering the range from the current year up to 4-year-old needles in the literature data, there was no sign of Hg saturation in conifer needles with age. Thus, over timescales of approximately 1 month to several years, the Hg uptake in foliage from the atmosphere always dominated over Hg evasion. Rwandan broadleaved trees had generally older leaves due to lack of seasonal abscission and higher [Hg] than Swedish broadleaved trees. The significance of atmospheric Hg uptake in plants was shown in a wheat experiment where charcoal-filtrated air led to significantly lower leaf [Hg]. To search for general patterns, the accumulation rates of Hg in the diverse set of tree species in the Gothenburg area were related to the specific leaf area (SLA). Leaf-area-based [Hg] was negatively and non-linearly correlated with SLA, while mass-based [Hg] had a somewhat weaker positive relationship with SLA. An elaborated understanding of the relationship behind [Hg] and SLA may have the potential to support large-scale modelling of Hg uptake by vegetation and Hg circulation.

- Article

(1966 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Mercury (Hg) is widely distributed in the atmosphere and is known to deposit in ecosystems, where it can transform to highly toxic methylmercury. Important atmospheric sources of Hg are for example burning of fossil fuels, artisanal and small-scale gold mining and non-ferrous metal and cement production, along with natural sources such as volcanic activity, fires and weathering of rocks (UN Environment, 2019). Most mercury in the atmosphere is recognized as gaseous elemental mercury (GEM, Hg0), globally distributed due to its long residence time in air (6–24 months), having background concentrations of approximately 1.3–1.6 and 1.0–1.3 ng m−3 in the Northern Hemisphere and Southern Hemisphere, respectively (Sprovieri et al., 2016).

The bidirectional exchange of Hg0 between the atmosphere and terrestrial surfaces is poorly understood. Deposition of Hg, representing the downward flux, is a combination of Hg0 (dry deposition) and oxidized species of Hg, including particulate Hg (dry and wet deposition). The re-emission of Hg from terrestrial and water surfaces, the upward flux, consists primarily of gaseous Hg0 (Bishop et al., 2020). Wet deposition of Hg is widely monitored by measuring Hg in precipitation. Measuring dry deposition includes dry deposition of both Hg0 and HgII on foliar surfaces washed off by throughfall (Graydon et al., 2008), vegetation Hg0 uptake followed by litterfall (Risch et al., 2017), and direct dry deposition to ground surfaces. In this context, the net accumulation of Hg in tree leaves and needles, which has been shown to represent a substantial uptake (Obrist et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2021), can provide important information on Hg fluxes over timescales of months to years.

A pronounced seasonality in the atmospheric concentration of elemental mercury, [Hg0], has been observed over the Northern Hemisphere, well correlated with the annual variation in the carbon dioxide concentration, [CO2] (Obrist, 2007). Jiskra et al. (2018) explored this observation and pointed out that the seasonal amplitude of [Hg0], like that of [CO2], increases with latitude. The authors suggested that terrestrial vegetation acts as a global Hg0 pump, removing atmospheric Hg mainly during the growing season when plant gas exchange in terms of photosynthesis, and thus CO2 uptake, is large. The observed seasonality of [Hg] in the Northern Hemisphere would then be explained by seasonal vegetation uptake, rather than by variation in Hg emissions or atmospheric oxidation of Hg0. Jiskra et al. (2018) used a median foliar Hg concentration of 24 ng g−1 to estimate the total deposition of Hg to vegetation over the Northern Hemisphere. This estimate of the typical foliar Hg level emanates from Grigal (2002) and does not explicitly distinguish between trees and crops, conifers and deciduous trees or foliage of different age, for example.

It is not fully understood how Hg0 is taken up by foliage. However, Laacouri et al. (2013) suggested it to be a stomatal diffusion process due to the correlation between leaf Hg content and stomatal density. Also, non-stomatal adsorption of Hg0 to cuticle surfaces has been observed (Stamenkovic and Gustin, 2009), but Frescholtz et al. (2003) concluded from experimental washing of quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) that leaf surface deposition was not significant in their experiment. There is instead experimental evidence that the accumulation of Hg inside leaves is dominated by stomatal uptake of Hg0 from the atmosphere (Lindberg et al., 2007). This applies to trees (e.g. Millhollen et al., 2006; Assad et al., 2016) as well as crops like wheat and corn (e.g. Niu et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2019). In addition, observations suggest a continued accumulation of Hg over time in green leaf tissue, e.g. from younger to older leaves (Bushey et al., 2008) or needles (Wyttenbach and Tobler, 1988). The detailed character and relative importance of biochemical processes inside the leaf subsequent to stomatal uptake in the accumulation of Hg in leaf tissue are not completely understood. Du and Fang (1983) found that in wheat leaves Hg0 was converted to divalent Hg2+ resulting from oxidation, likely promoted by the enzyme catalase.

The mobility of Hg within plants after uptake by the leaves seems to be limited. Niu et al. (2011) observed that leaf [Hg] was strongly correlated to air [Hg] but not to soil [Hg], while root [Hg] was linked almost entirely to soil [Hg]. This explains why [Hg] in crops has been observed to be much higher in leaves than in fruits or seeds (Li et al., 2017; Niu et al., 2011). Yang et al. (2018) found [Hg] in wood to be much lower than in leaves and needles of a range of broadleaved and conifer species of north-eastern USA. Although [Hg] in wood is not a direct measure of Hg transport, this observation provides an indication of limited Hg transport.

There are several observations of Hg0 emissions from leaves (Bishop et al., 2020; Sommar et al., 2020). Yuan et al. (2019), using stable Hg isotopes and a branch chamber system, provided direct evidence of foliar Hg0 re-emission partly counteracting foliar uptake. Empirical evidence of the development of the Hg concentration over time in leaves suggests exposure of vegetation to elevated atmospheric levels of Hg0 generally result in a net accumulation in leaves–needles, which is not in conflict with the dynamical bidirectional fluxes found using high time resolution of isotope techniques (e.g. Demers et al., 2013).

In most studies, the leaf concentration of Hg was expressed on a mass basis, [Hg]M. However, from an ecosystem perspective it would be equally, or in some cases more, relevant to use leaf-area-based concentrations, [Hg]A. It can be calculated through dividing [Hg]M by the specific leaf area (SLA, leaf area per unit leaf mass), a leaf trait which varies between plant functional types such as broadleaved trees and conifers (Poorter et al., 2009). The significance of [Hg]A follows from the assumption that Hg0 is mainly taken up through the leaf surface, i.e. stomata and cuticles, as explained above. The ecosystem uptake may therefore partly be driven by its leaf area index (LAI, unit area leaves per unit area ground). However, if [Hg] in the leaves saturates with time, the ecosystem uptake might instead be limited by the total leaf mass. In both cases, duration of the uptake period (i.e. the seasonal variation in stomatal opening and leaf longevity) will have a decisive effect on Hg accumulation.

The maximum leaf area index in a closed canopy has an upper limit set by incoming light interception (Larcher, 2003). Thus, a mature broadleaved forest and a mature conifer forest may approach similar LAI. Since conifer needles are typically thicker (have lower SLA) than leaves, leaf mass will be larger in the conifer forest. If Hg uptake is related to leaf mass rather than leaf area, i.e. depends on SLA, the Hg accumulation could be larger in conifer forests than broadleaved forests, provided that the two forests have the same LAI, thus possibly representing a stronger Hg sink. This calls for an investigation of the variation in [Hg]A among trees in combination with exposure time to compare Hg accumulation by trees of different functional types. This line of argument was investigated by Wohlgemuth et al. (2020) by comparing conifers and broadleaved trees with respect to area-based Hg concentrations. If the unit leaf area accumulation of Hg depends on the fundamental leaf characteristic SLA, a general understanding of the relationship behind [Hg]A and SLA would support improved descriptions of Hg uptake by vegetation applied in large-scale atmospheric modelling and assessments of its biogeochemical cycling.

In this study, [Hg] in leaves from a diverse set of plant types, locations and different sampling periods was studied in order to find out if there is an essentially continuous accumulation of Hg in leaf tissue over time. Collected conifer data were complemented with literature data to further analyse the relationship between [Hg]M and needle age. Finally, the relationship between Hg accumulation and SLA was investigated.

The hypotheses were as follows.

-

Over time periods of months to years, there is a continued net accumulation of Hg in foliage for all studied plant species.

-

Hg accumulation in foliage has a negative relationship with SLA.

-

Hg concentrations in tropical tree leaves are higher than in broadleaved trees of the temperate zone, due to the lack of seasonal abscission of broadleaved trees in the tropics.

-

Hg accumulation in wheat is dominated by leaf uptake from air, and redistribution of Hg to other plant parts, including seeds, is small.

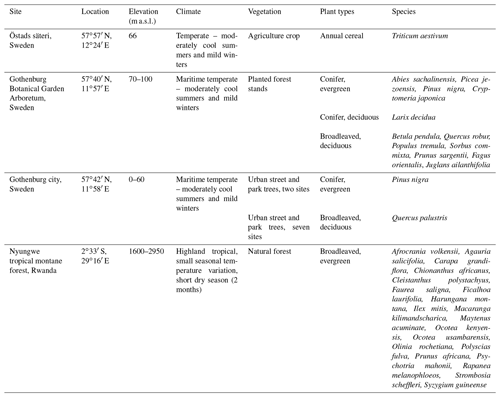

2.1 Sampling sites

Leaf samples were collected from trees at three different sites: (i) the Botanical Garden Arboretum in Gothenburg, Sweden; (ii) city area of Gothenburg, Sweden (seven sampling points) and (iii) the Nyungwe tropical montane forest in Rwanda. The wheat experiment was conducted at a wheat crop field at Östads säteri, 35 km north-east of Gothenburg, Sweden. These sites will hereafter be denoted arboretum, Gothenburg city, Nyungwe and Östad, respectively. The Arboretum and Gothenburg city sites will collectively be denoted as the Gothenburg area. See Table 1 for an overview of sites and investigated plant species.

2.1.1 Gothenburg area

The arboretum and Gothenburg city sites are located in the Gothenburg area on the south-west coast of Sweden. Gothenburg is the second largest city in Sweden with approximately 540 000 inhabitants. It has a maritime temperate climate with, for the latitude, moderately cool summers and mild winters. Annual mean temperature is 7.6 ∘C, and annual mean precipitation is 772 mm. Like large areas of north and central Europe, Gothenburg experienced an unusually warm and dry summer in 2018. The average daytime temperature from April–September 2018 was higher by 2.0–2.4 ∘C in 2018, and the water vapour pressure deficit (VPD) was positively affected compared to the preceding 5-year period (Johansson et al., 2020).

The arboretum (botanical garden collection of planted trees from Europe, Asia and North America) enabled comparison of a range of tree species in similar growth conditions. The distance to the closest traffic route is about 800 m. Twelve tree species representing contrasting leaf characteristics were selected for comparison: four evergreen conifers, one deciduous conifer and seven deciduous broadleaved species (Table 1). Further details on the sampling sites in the Gothenburg area are provided in the supporting data file (see Data availability below).

2.1.2 Nyungwe tropical montane forest

Nyungwe tropical montane rainforest is located in south-western Rwanda covering 1013 km2 (Table 1). It consists of a mixture of late successional and early successional trees, mainly evergreens. Annual mean temperature in sampled areas is 13.7 to 15.6 ∘C, and mean annual precipitation is 1867 mm. The seasonal variation in temperature is small, but precipitation varies spatially and seasonally, with a dry period of 2 months, from mid-June to mid-August. Sampled trees were growing at elevations between ca. 1950 and 2500 m a.s.l. along a 32 km long east-to-west transect. Nyirambangutse et al. (2017) provide details of the sampling sites and characteristics of the tree species.

2.1.3 Östads säteri, south-west Sweden

Wheat data were obtained from an experiment in which field-grown wheat was exposed to five different levels of ozone in open-top chambers. The treatments were charcoal-filtered air (daytime average ozone concentrations in brackets): CF (7 ppb ozone), non-filtered air: NF (20 ppb), and non-filtered air with three levels of elevated ozone: NF+ (34 ppb), NF++ (48 ppb) and NF+++ (62 ppb). The site is located at Östads säteri (Table 1). Each treatment was replicated with five chambers (n=5). Ozone exposure started on 1 July and continued until harvest by the end of August. Mid-anthesis (flowering) was reached on 8 July. Gelang et al. (2000) provide details of the experimental system.

2.2 Collection and preparation of samples

Three trees of each species were sampled at all sampling points in the Gothenburg area while 3 to 38 trees of each species were sampled in Nyungwe (combined into 2–11 composite samples; 60 % of the species included >10 trees). A pruning pole was used at all sites to cut branches from the upper part of the tree crown. Branches with leaves or needles in the outer part of the crown were selected. In the Gothenburg area leaves from broadleaved deciduous trees including Larix decidua were collected on 25–28 June and 17–20 September 2018, while shoots from conifers of the age classes current +1 (C + 1) and current+3 (C + 3) were collected on 25–28 June during the same year. Mature leaves from Nyungwe trees were collected in the period between August and December 2013. The samples were packed in polyethylene plastic bags, transported in a cool bag and stored in a fridge until further handling.

Five to six leaves from each sampled broadleaved tree and three shoots of each age class and conifer tree were randomly selected from harvested branches for determination of SLA. A total of six or more leaf discs of a known area (18, 13, 10 or 8 mm in diameter, depending on leaf size and sampling location) were collected per sample using a puncher. The discs were oven-dried in 70 ∘C for at least 48 h and then weighed (laboratory balance with 0.1 mg resolution). For conifers, 20 needles (40 from Larix due to small needle size) were removed using tweezers and scanned to determine total projected area using WinSEEDLE (plant image analysis scanner and software from Regent Instruments Inc, Canada; version Pro 5.1a). Needles were dried and weighed, following the same procedure as for broadleaved species. Determination of SLA for Cryptomeria was complicated by the shoot/needle morphology, prohibiting complete consistency with the other conifers. For this species, the needles could not be removed from the shoots without causing damage. Thus, reliable SLA values could not be obtained for Cryptomeira, and this species was consequently excluded from analyses involving SLA.

Sampled wheat plants were separated into leaves, straw, grain and chaff. Three shoots were sampled on each of three days (16, 18, 21 July 1999) in the early part of the grain filling period and on three days (13, 15, 18 August) short before final harvest (starting 19 August) from each plot. The samples for each experimental plot from the three earlier dates and the three later dates, respectively, were pooled to obtain sufficient plant material for elemental analysis of all fractions (seeds, leaves, straw, chaff), with the two sampling periods thus being approximately 4 weeks apart.

Samples for element analysis, carefully collected to avoid contamination, were put in aluminium (Gothenburg area and Östad) or paper envelopes (Nyungwe) and dried in 70 ∘C until constant weight (at least 48 h). Thereafter the samples were ground to a fine powder using a ball mill (model MM 301, Retsch, Haan, Germany) equipped with grinding jars and balls made of wolfram carbide, except samples from Östad that were ground with jars and balls made of stainless steel.

2.3 Analysis of the concentration of Hg and other elements in leaves and needles

Samples were analysed for the content of 37 elements including Hg using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (dry vegetation ICP-MS, 37 elements after digestion in HNO3 and then aqua regia (method VG101); Bureau Veritas Mineral laboratories, Vancouver, BC, Canada). Here, only Hg data are presented. The concentrations of Hg in the samples were determined as mass-based [Hg]M and were also converted to area-based [Hg]A by dividing [Hg]M by SLA. The laboratory has implemented an analytical quality management system meeting the requirements of ISO/IEC 17025 and ISO 9001. The method detection limit (MDL) for Hg was 1 ng g−1. Values below MDL, obtained for samples of grain, stems and chaff of wheat, are presented as 0.5 MDL, and these plant fractions were excluded from statistical analysis. All other samples were greater than MDL.

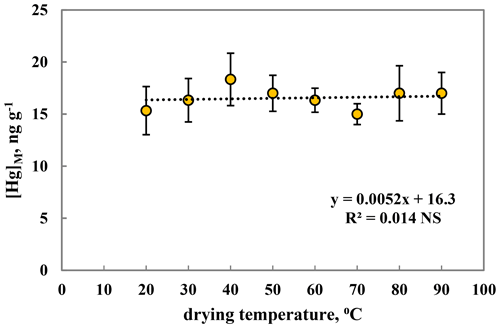

To test if there is an influence of drying temperature on the estimation of [Hg], a batch of Populus tremula leaves were collected in the arboretum in August 2019, and three subsamples were dried at each of the following temperatures: 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80 and 90 ∘C. They were then subject to elemental analysis as described above. As can be inferred from Fig. 1, there was no indication of an influence of drying temperature on the estimated leaf [Hg]M. This means that higher drying temperatures in pre-treatment of samples for mercury analysis do not lead to an underestimation of [Hg]M due to loss of volatile Hg components. This is in line with the evidence by Lodenius et al. (2003) studying Hg accumulation in the moss Sphagnum girgensohnii and the grass Lolium perenne, as well as Wohlgemuth et al. (2020) working with forest trees.

2.4 Literature review for [Hg]M of conifer needles

The scientific literature was searched for data on [Hg] in conifer needles using Web of Science. Only studies with the age classes of sampled needles explicitly specified were included. A summary of conifer needle Hg data found in literature is presented in Table 2. The specific data are presented in the file available at the data repository. Data only presented in graphs were extracted using GetData Graphic Digitizer software (version 2.26).

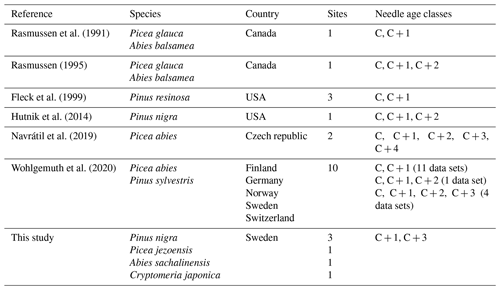

Table 2Overview of the data obtained from the literature search and our study to investigate the dependence of [Hg]M on needle age class, including literature reference, species studied, country where the sampling took place, number of sites covered by the study and needle age classes sampled. C is current-year needles, C + 1 is 1-year-old needles, etc.

2.5 Calculation of the annual Hg uptake rate by leaves and needles in the Gothenburg area

For broadleaved trees and Larix, September values of [Hg]M and [Hg]A were considered to represent the Hg uptake during one growing season, since the sampling was made short before senescence and shedding of leaves and needles. To estimate the uptake of Hg by perennial needles per growing season, C + 3 values of [Hg]M and [Hg]A were divided by 3. C + 3 needles collected by the end of June are marginally older than 3 years.

2.6 Statistical methods

Differences in [Hg]M and [Hg]A for the sampling in the Gothenburg area were investigated using a mixed designed analysis of variance (ANOVA) with IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25). Leaf–needle age was set to the within-subject variable (repeated measures) with two levels, the two different shoot age classes for conifers and the two sampling times for deciduous trees as well as wheat. The between-subject factor was set to the sampling location in Gothenburg city, species in the arboretum or experimental ozone treatment of wheat. Tukey's HD was used as a post hoc test. Linear regression was used to assess the relationship between [Hg]M and drying temperature and between [Hg]M and needle age, using absolute concentration values as well as concentrations in relation to the needle age class C + 1. Linear regression was also used to study the relationship of [Hg]M and [Hg]A with SLA after log transformation of SLA values. One-way ANOVA was used to investigate variation in [Hg]M among tree species in Rwanda using Hochberg's GT2 as a post hoc test. The difference in [Hg]M between Rwandan trees and September values of broadleaved trees in the Gothenburg area was tested using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test.

3.1 Conifers in Gothenburg area

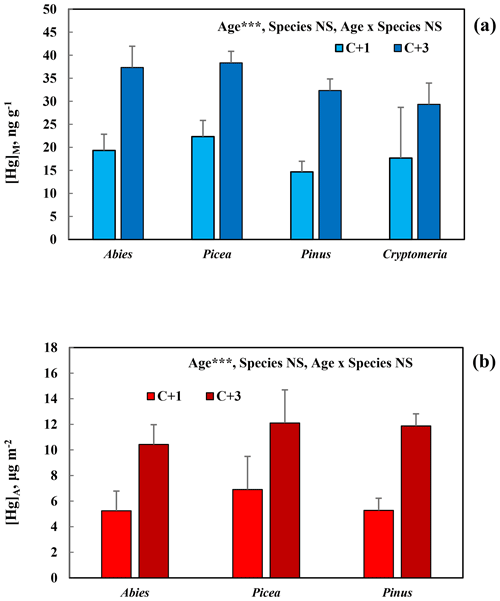

[Hg]M and [Hg]A of C + 1 and C + 3 needles of the different species of conifers with perennial needles, sampled in the Botanical Garden Arboretum, are presented in Fig. 2a and b. There was a significant (p<0.001) and consistent increase in Hg concentration for both [Hg]M and [Hg]A from C + 1 to C + 3 needles. Both for [Hg]M and [Hg]A, the variation among species was modest, with no significant differences.

Figure 2Mass-based [Hg]M (a) and area-based [Hg]A (b) in 1-year-old (C + 1) and 3-year-old (C + 3) needles of conifers (Abies sachalinensis, Picea jezoensis, Pinus nigra, Cryptomeria japonica) in the Gothenburg Botanical Garden Arboretum. Cryptomeria was not included in Fig. 2b because of the uncertainties in the SLA determination for this species. Error bars show standard deviation for the three trees sampled per species; ; NS, non-significant.

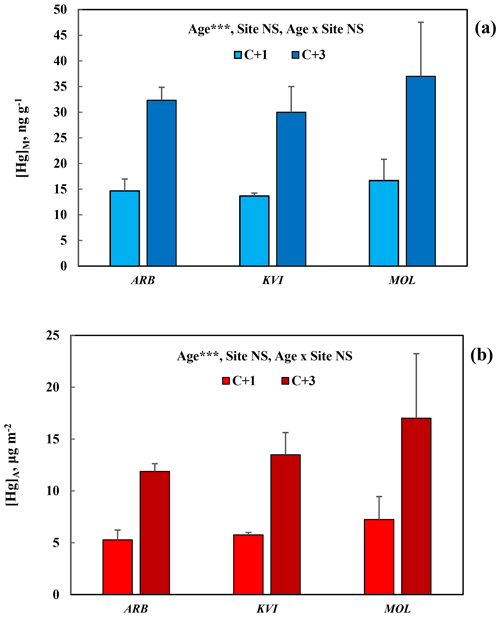

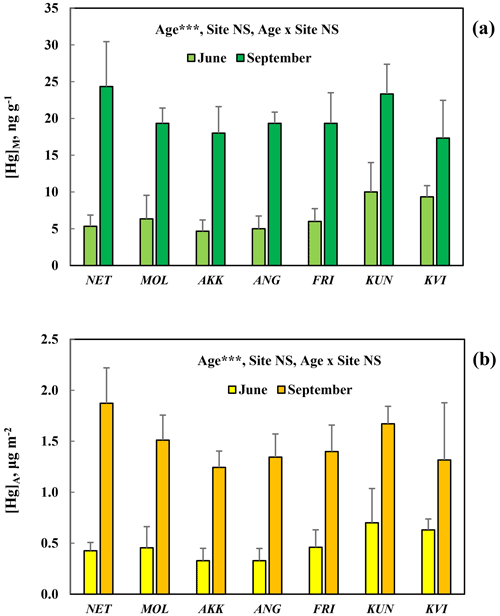

For comparison between sites, data for [Hg]M and [Hg]A in Pinus nigra are here presented at three sites in the Gothenburg area, Fig. 3a and b, respectively. Again, the concentration increase from C + 1 to C + 3 needles was consistent and significant (p<0.001), while the variation between sites was small and non-significant for both [Hg]M and [Hg]A.

Figure 3Mass-based [Hg]M (a) and area-based [Hg]A (b) in 1-year-old (C + 1) and 3-year-old (C + 3) needles of Pinus nigra at three sites in the Gothenburg area including the arboretum. Error bars show standard deviation for the three trees sampled per species. ; NS, non-significant. Site locations and characteristics are available in the supporting information.

3.2 Conifer data from the literature

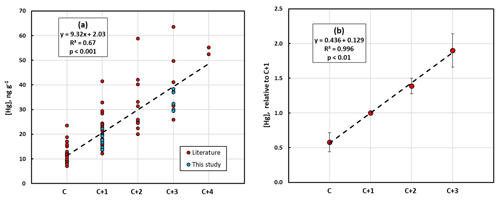

In Fig. 4a, the data regarding conifers from our investigation in the city of Gothenburg are combined with literature data. There was a strong and highly significant linear relationship between [Hg]M and needle age, although the data come from different parts of Europe and North America and represent 10 different conifer species of the four genera Abies, Picea, Pinus and Cryptomeria. In Fig. 4b, relative values of [Hg]M in different needle age classes are shown using the most commonly sampled needle age class, C + 1, as the reference. Values for the other age classes of a certain data set were divided by the value for C + 1 for that data set to obtain a common, relative scale for all observations. Data sets without C + 1 data were consequently not included. Likewise, C + 4 needles were not included since only one paper reported data for this needle age class. There was no indication of a saturation of [Hg]M at higher needle age. Instead, the amount of Hg added per year is similar from one needle age class to the next, over the range of needle age classes covered, in both Fig. 4a and b. However, since the slope coefficient of the relationship presented in Fig. 4b is <0.5, there is still an indication of a decrease in the rate of Hg accumulation over time.

Figure 4(a) Absolute mass-based concentration of mercury, [Hg]M, in different conifer species from the present study and data from the literature in relation to needle age (C is current year, C + 1 is 1 year old, etc.). (b) Averages of mass-based concentration of mercury, [Hg]M, from the present study and from the literature in relation to needle age as values relative to the concentration in the 1-year-old (C + 1) needle age class. For each data set the [Hg]M of the different needle age classes was divided by the [Hg]M of the C + 1 to create a relative scale. Error bars show standard deviation.

3.3 Deciduous trees in Gothenburg area

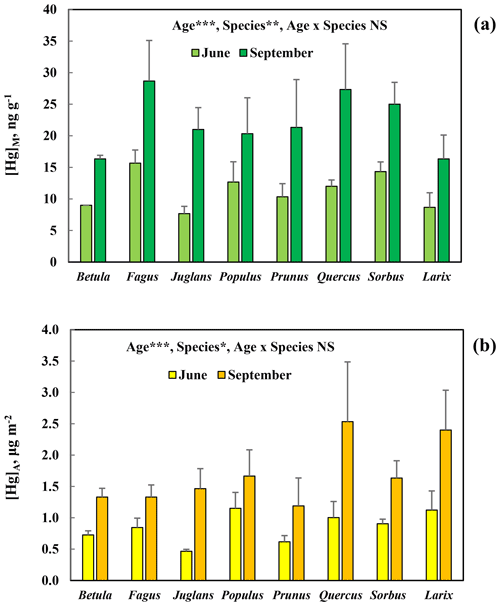

[Hg]M and [Hg]A increased consistently and similarly for all broadleaved tree species, as well as for the deciduous conifer Larix, investigated in the arboretum (Fig. 5). The difference in concentrations between June and September was statistically significant (p<0.001). There was also a significant variation among species (p<0.01 for [Hg]M and p<0.05 for[Hg]A). The post hoc test of the ANOVA showed that for [Hg]M Betula and Larix were significantly different from Fagus, and in the case of [Hg]A Prunus differed significantly from Larix and Quercus.

Figure 5Mass-based [Hg]M (a) and area-based [Hg]A (b) concentrations of mercury in leaves sampled in June and September of seven broadleaved tree species (Betula pendula, Fagus orientalis, Juglans ailanthifolia, Populus tremula, Prunus sargentii, Quercus robur, Sorbus commixta) and one deciduous conifer (Larix decidua) in the Gothenburg Botanical Garden Arboretum. Error bars show the standard deviation for the three trees sampled per species; ; ; ; NS, non-significant.

[Hg]M and [Hg]A in Quercus palustris at seven different sites in the city of Gothenburg (Table 1) showed a consistent, highly significant (p<0.001) pattern of increased concentrations from June to September (Fig. 6). The concentration levels were similar at all the different sites, and consequently the site effect was non-significant (p>0.05). The smaller difference among sites with Quercus palustris compared to the difference among species in the arboretum may represent genetic variation in Hg uptake rate among the investigated species in the arboretum. The genetic variation in properties of interest for Hg uptake, such as inter-species variation in stomatal conductance, is expected to be small when only one species is considered.

Figure 6Mass-based [Hg]M (a) and area-based [Hg]A (b) concentrations of mercury in leaves sampled in June and September from Quercus palustris trees at seven sites with different local air pollution in the city of Gothenburg. Error bars show the standard deviation, between the three trees sampled per species; ; NS, non-significant. Site locations and characteristics are available in the supporting information.

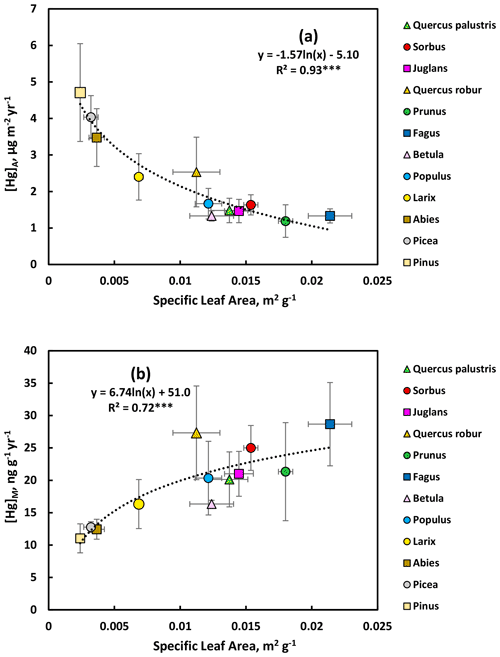

3.4 Relationship between annual Hg accumulation and specific leaf area SLA

As explained in the Methods section, September values for broadleaved trees and Larix were considered to represent the Hg uptake during one growing season. For conifers with perennial needles, C + 3 values were divided by 3 to obtain a comparable growing season estimate of Hg uptake. The resulting [Hg]M and [Hg]A data for both groups of trees were plotted vs. SLA for all observations in the Gothenburg area (Fig. 7). There was a consistent (R2=0.93) non-linear (logarithmic) relationship between the annual increment in [Hg]A and specific leaf area (SLA, Fig. 7a). The rate of increase in [Hg]A per growing season was larger for evergreen conifers, with low SLA, compared to broadleaved trees, having higher SLA. The annual conifer Larix was intermediate between these groups. For the growing season rate of increase in [Hg]M, there was a weaker but statistically significant positive logarithmic relationship with SLA (Fig. 7b), where the broadleaved trees consistently showed higher rates than evergreen conifers. Again, Larix was intermediate. Thus, the evergreen conifers had higher per unit leaf area uptake rates of Hg strongly dependant on SLA, while broadleaved trees had higher Hg uptake rates per unit leaf mass which were more variable and not as strongly linked to SLA.

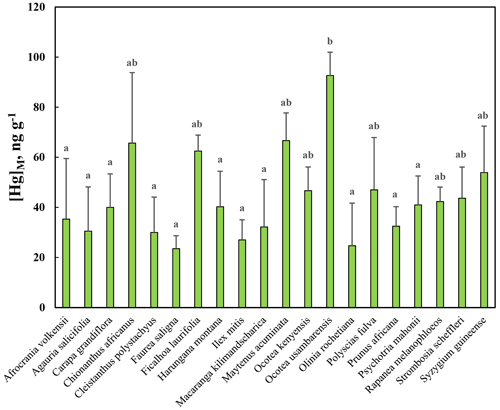

3.5 Broadleaved evergreen trees in Nyungwe

[Hg]M was investigated in leaves from 20 broadleaved evergreen tree species in Nyungwe (Table 1). As evident from Fig. 8, there was a substantial variation between species, and the ANOVA showed that there was statistically significant variation (p<0.01) in [Hg]M among species, as displayed in Fig. 8. The post hoc test revealed that there were significant differences between the species with the highest [Hg]M (Ocotea usambarensis) and 11 of the other species as depicted in Fig. 8. None of the other differences between species were statistically significant.

The average [Hg]M for all species of the Rwandan data set was 43.9 ng g−1 with a standard deviation among species of 17.3 ng g−1. This can be compared with the average [Hg]M for all broadleaved species in the Gothenburg area, 9.2 and 21.5 ng g−1 for June and September, respectively. Thus, in general, leaf concentrations of broadleaved trees in Rwanda were approximately twice as high as in the Gothenburg area by the end of the growing season in September. The Mann–Whitney U test showed that [Hg]M in leaves of Rwandan tree species was significantly higher (p<0.01) than in leaves of broadleaved trees in the Gothenburg area from the September sampling.

The seasonal accumulation of Hg was not possible to determine for the Rwandan trees, as the leaf ages were unknown, but most of them were likely in the range of 0.5 to 2 years. However, their SLA was in a rather narrow range with values between most of the evergreen conifers and deciduous trees of the Gothenburg area, 0.006 to 0.012 m2 g−1.

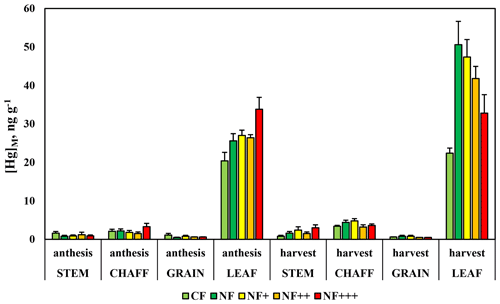

3.6 Wheat

The observations of [Hg]M in different fractions of wheat short after anthesis and at maturity in five different ozone treatments showed a number of clear characteristics (Fig. 9). [Hg]M of grain and straw was low and in several cases below the MDL of 1 ng g−1, both after anthesis and at maturity. Grains had the lowest Hg levels. For chaff, the concentrations were somewhat higher and above MDL for all samples at maturity. In leaves, [Hg]M was above MDL in all samples and higher than in the other plant fractions. The ANOVA was performed only for leaves, the plant fraction for which all samples were above MDL for both sampling periods. It showed a statistically significant increase in [Hg]M from anthesis to maturity (p<0.001), a significant ozone treatment effect (p=0.002) and a significant interaction time by treatment effect (p<0.001). A post hoc test revealed that [Hg]M of the charcoal-filtered treatment, which did not increase over time, was significantly different from the other four ozone treatments among which there were no statistically significant differences. This can be explained by the removal of Hg by the charcoal filters and shows that the uptake of Hg0 from the air was the main source of leaf Hg. In the other four treatments, there was an increase in [Hg]M between the two sampling periods. For the non-filtered air treatment, representing the current ambient air situation, there was approximately a doubling of [Hg]M between the sampling after anthesis and that before harvest. The magnitude of this leaf age effect on [Hg]M declined with increasing ozone concentration, likely associated with the shortening of leaf lifespan from ozone (Mullholland et al., 1998), reducing the duration of the period with gas exchange of the leaves (Mullholland et al., 1997; Feng et al., 2010; Osborne et al., 2019). Gelang et al. (2000) found, for the experiment used here, a reduction in the duration of grain filling and a reduced flag leaf (the uppermost leaf on the shoot) area duration, based on chlorophyll measurements, which were strongly related to ozone exposure. Compared to the NF treatment, the duration of the flag leaf was estimated to be reduced by 5, 19 and 29 d in the NF+, NF++ and NF+++ treatments, respectively. Regressing the leaf [Hg]M at maturity vs. the ozone exposure index AOT40 (Accumulated exposure Over a Threshold of 40 ppb; Fuhrer et al., 1997) resulted in a significant (p=0.003, R2=0.994) relationship ([Hg]M=50.9–0.0017 × AOT40).

In the review of global environmental mercury processes by Obrist et al. (2018), it is concluded that most terrestrial environments are net sinks of atmospheric Hg due to substantial uptake by plants. This was further substantiated by the review of Zhou et al. (2021). In agreement with this, our data from the Gothenburg area showed, with no exception, that Hg accumulated over time in leaf and needle tissue in different tree species at varying locations and without signs of saturation with time. The literature data for [Hg]M in needles of different ages (Fig. 4a and b) likewise showed a monotonic pattern of increase over time, which agreed well with our data and suggests that over the timescales considered here, months to years, net accumulation of Hg over time is the rule. Based on a range of literature sources, Grigal (2002) reported that most tree foliar [Hg]M concentrations are in the range 10–50 ng g−1 with a midpoint of 24 ng g−1. This value was used by Obrist (2007), and later by Jiskra et al. (2018), in the assessment of the role of vegetation in the annual dynamics of the atmospheric Hg concentration. Essentially, this range and midpoint value are in line with our observations of September [Hg]M of deciduous trees (21.5 mg g−1) and C + 3 [Hg]M of evergreen conifers (34.1 ng g−1) in the Gothenburg area, whereas the average for Rwandan trees was 43.9 ng g−1. Wang et al. (2018), in an assessment of global mercury through litterfall, stated that dry deposition of Hg is larger in tropical regions than temperate and boreal regions. This agrees with the higher values found in Rwandan trees in our study and with the effect of a longer growing season of Hg uptake. The average [Hg]M of litterfall in tropical (Brazil) and North American–European data, in the review by Wang et al. (2016), was 92 and 43 ng g−1, respectively. This is higher than the average values obtained from our data. It should then be kept in mind that litterfall could have lost organic carbon, therefore concentrating Hg (e.g. Pokharel and Obrist, 2011), and that the variation in data compiled by Wang et al. (2016) was substantial. Also, it cannot be excluded that Hg accumulation in litter continues after shedding of leaves or needles.

Litterfall from forest trees represents an important flux of Hg to the soil system (Munthe et al., 1995; St. Louis et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2016). Further, and as mentioned in the previous paragraph, it has been reported that litterfall has higher [Hg]M than what has been measured in foliage (e.g. Rea et al., 1996). As pointed out by Grigal (2002), this may, partly, be attributed to the fact that leaves shed in the autumn accumulated Hg over the full growing season, while leaves analysed for [Hg]M were often sampled earlier during the season and are likely to have lower [Hg]M. This is in line with our observations of a consistent and substantial increase in leaf [Hg]M and [Hg]A from June to September of broadleaved trees in the Gothenburg area.

A corresponding consideration of the importance of age also applies to conifers, on a multi-annual timescale, for which analyses of needle [Hg]M were made for the needle age classes C + 1 and C + 3. Many conifers maintain needles for 4–10 years (Reich et al., 1996, 2014), and it is mostly the oldest needles, likely having higher [Hg]M, that are shed and then form litter (e.g. Nebel and Matile, 1992; Wyttenbach and Tobler, 2000; Muukkonen, 2005). We conclude that the bias towards sampling younger leaves and needles that had less time to accumulate Hg could, if used to estimate litter Hg flux, lead to an underestimation of the flux of Hg by leaf–needle shedding. Direct measurements of litter flux do not suffer from this bias.

On shorter timescales, evasion of Hg from vegetation to the atmosphere occurs (e.g. Yuan et al., 2019). Short-term closed-chamber gas exchange experiments have provided evidence of the existence of a compensation point for Hg uptake and release from leaves (Hanson et al., 1995), and measurements of high-frequency above-canopy Hg flux using micrometeorological techniques over field crops (e.g. Sommar et al., 2016) show that fluxes from the plant–soil system to the atmosphere are important. Further, Yuan et al. (2019) showed that part of the Hg0 that has been absorbed and oxidized in the leaves becomes reduced and re-emitted. This process is in no way inconsistent with our results that there is a net accumulation of Hg in plant tissue over time horizons of months to years. Isotope studies that have been undertaken (e.g. Demers et al., 2013; Yuan et al., 2019) show that the gross uptake of Hg by leaves is larger than what bulk analysis of leaf samples (net uptake), such as in our study, shows.

Figure 9Mass-based concentrations of mercury, [Hg]M, in four fractions of wheat after anthesis and short before harvest. Data are from an ozone experiment with field-grown wheat. CF, charcoal-filtered air; NF, non-filtered air; NF+, NF++ and NF+++, non-filtered air with different levels of ozone added. Error bars show standard deviation for the five replicate experimental chambers per treatment.

From a biogeochemical and ecosystem perspective there are several aspects to consider when assessing the accumulation of Hg. Firstly, the age of the leaf–needle tissue is of critical importance. Secondly, over the range of needle age classes considered, there was no saturation of [Hg]M. Barghigiani et al. (1991) observed much higher concentrations in Pinus needles in regions of Italy with high atmospheric Hg concentrations than those obtained in the Gothenburg region. For example, C + 2 leaves of Pinus laricio in Pisa reached a [Hg]M of around 140 ng g−1 after a steady increase from year to year, again suggesting a needle sink of Hg exceeding Hg levels attained in our measurements.

Thirdly, it should be noted that many conifer species typically have more than three or four needle age classes (Reich et al., 1995), while sampling of needles has focused on the youngest needle age classes up to C + 2, rarely including C + 3 and even more uncommonly C + 4. This represents a bias in the understanding of conifer accumulation of Hg towards plant tissue with lower [Hg]M and points towards the necessity of strict protocols for needle age class sampling in biomonitoring, as pointed out by Bertolotti and Gialanella (2014). Older needle age classes will provide a stronger Hg accumulation signal in biomonitoring. Also, this suggests that studies should be undertaken where sampling is made of all needle age classes to find out if there is a saturation of [Hg]M in the oldest needles.

The typically high longevity of evergreen tropical leaves further emphasizes the importance of including older leaves in assessments of Hg fluxes in forested ecosystems. Reich et al. (1991) showed that tropical evergreen leaves having a SLA below 0.01 m2 g−1 had a lifespan between 10–50 months. This explains why the 20 species of tropical montane trees in Rwanda (SLA 0.006–0.012 m2 g−1) on average had approximately double [Hg]M compared to deciduous trees after 5–6 months in the Gothenburg area, in line with our third hypothesis and the findings by Zhou et al. (2021) that evergreen trees have significantly higher [Hg]M compared to deciduous trees. Leaves of tropical and subtropical trees of well-defined and different ages should be studied with respect to [Hg]M. Trees from tropical and subtropical biomes seem to have been investigated for Hg concentrations to a smaller extent in comparison to boreal regions.

Our study showed that Hg accumulation for trees in the Gothenburg area had a relationship with SLA, especially for [Hg]A (negative relationship), but also for [Hg]M (positive relationship). Thus, the result was more complex than our hypothesis stating that Hg accumulation would be negatively related to SLA. However, it means that SLA as a leaf trait might be a useful predictor of Hg accumulation, which should be investigated further, and points towards the significance of not neglecting [Hg]A since the same [Hg]M for leaves with different SLA will result in different [Hg]A values. This can become useful in modelling of Hg fluxes from the atmosphere to vegetation in forest ecosystems; rather than using a single average value like that estimated by Grigal (2002), leaf functional traits such as SLA, and leaf longevity, could be used to fine-tune estimated Hg uptake by different forest types. However, our study of the relationships of Hg accumulation in leaves and needles with SLA is based on data from one specific region with a limited number of species. Further investigations in other biogeographic areas and with further species should be made to clarify the extent to which these relationships can be generalized.

Although Wohlgemuth et al. (2020) explored the significance of [Hg]A, the literature has so far almost exclusively considered [Hg]M. From an ecosystem perspective [Hg]A may be equally or more relevant as closing canopies approach similar LAI in different forest types. For example, a LAI of 5 m2 m−2 for an evergreen and a broadleaved forest stand will represent the same projected leaf area over unit ground area, but the leaf mass, and thus potentially also the Hg sink, will be larger for the evergreen stand associated with the lower SLA for evergreens.

Further studies are required to understand the differences in Hg accumulation of different types of trees (e.g. evergreen and deciduous types of both conifers and broadleaved species) in more detail. Evergreen conifers, with the exception of the needles formed in the current year, typically have a longer growing season with gas exchange than broadleaved trees in the climate of the Gothenburg area. This will tend to extend the duration of Hg uptake. However, broadleaved trees often have higher stomatal conductance, which will intensify the Hg flux to the leaves. For now, it can be concluded that in our study conifer needles had a faster increment in [Hg]A per growing season than broadleaved trees but that [Hg]M increased faster in leaves of broadleaved trees. Crops typically have even higher stomatal conductance than broadleaved trees (Lin et al., 2015). This explains the even faster rate of accumulation of Hg by wheat leaves in our study. Over approximately 1 month [Hg]M increased by 25 ng g−1 (from 26 to 51 ng g−1, Fig. 9), while the average increase in [Hg]M of broadleaved trees in the arboretum was 11 ng g−1 (from 11 to 22 ng g−1, Fig. 5) over a 3-month period.

The only species for which we analysed the distribution of Hg within the plant was wheat. It showed that leaves are the dominating, essentially ultimate sink for Hg in the above-ground parts of this species, while little redistribution to other parts of the plants seemed to occur. This is in sharp contrast to many nutrients and other elements, which are more or less efficiently redistributed from leaves and stems to grains during grain filling (Marschner, 2012). In particular, grain concentrations of Hg were very low in our study. This supports the fourth hypothesis and is in line with conclusions that leaf crops tend to have comparatively high Hg levels (De Temmerman et al., 2009) and the observation by Li et al. (2017) that [Hg]M in tomato plants was considerably higher in leaves than in fruits, stems and roots. In addition, Niu et al. (2011) reported from experiments in the Chinese Hebei Province that seed [Hg]M in wheat and maize was very low, while leaf concentrations in wheat near harvest were ∼ 60 ng g−1, close to our observation for wheat leaves in the non-filtered air treatment short before harvest. In the Chinese Shandong Province, Sommar et al. (2016) found [Hg]M in wheat leaves up to 120 ng g−1. The significant reduction of leaf [Hg]M by charcoal filtration, known to remove Hg0, in our wheat study adds further evidence of the atmosphere as the main source of leaf Hg. An additional observation in our wheat experiment was that leaf [Hg]M near harvest declined with increasing ozone exposure. This can be explained by the shortening of the leaf lifespan, i.e. of the duration of leaf physiological activity and gas exchange, and thus Hg uptake, by the senescence-promoting air pollutant ozone (Gelang et al., 2000).

Several lines of evidence support the view that Hg in leaves is mainly a result of stomatal uptake of atmospheric gaseous elemental mercury (Ericksen et al., 2003) and has a correlation with stomatal density of the leaves (Laacouri et al., 2013). These authors also showed that in the investigated deciduous species the dominating leaf sink for Hg was tissues of the leaf interior (> 90 %) with minor amounts on the surface and in the cuticle.

Our results, showing a consistent and significant accumulation of Hg in leaf–needle biomass supports the view of Jiskra et al. (2018) that vegetation is an important Hg sink, which can explain the seasonality of background atmospheric [Hg0] concentrations in the Northern Hemisphere. This has implications for large-scale modelling of the biogeochemical Hg cycle and for future research investigating Hg concentrations in plants. In this type of modelling, the role of the variation in SLA among tree species and within canopies, as well as its relation to [Hg]M and [Hg]A for Hg accumulation, should be considered.

The most important conclusions from this study are as follows.

-

Over timescales of months to years, there was always a net accumulation of Hg in leaves and needles of trees with no saturation in needles up to 3 years old.

-

Leaf–needle age is critical for Hg concentration, which is important for sampling strategies and in the use of plant material as a biomonitor/bioaccumulator for Hg.

-

A bias towards sampling younger needle age classes of conifers, if used to assess Hg flux from foliage to soil, can lead to underestimation of this Hg flux since it is predominantly the oldest needles that are shed as litter.

-

Tropical trees had on average higher leaf [Hg]M than leaves of temperate trees. The likely reason is the longer leaf lifespan of tropical trees, but differences in rate of gas exchange may also be of importance.

-

Specific leaf area (SLA) is a leaf trait, which showed a relationship with unit area accumulation of Hg over the wide range of leaves–needle characteristics covered by our study of trees in the Gothenburg area. There was a weaker positive relationship between leaf–needle mass-based uptake of Hg and SLA. Studies should be undertaken to further investigate the role of SLA in Hg accumulation of leaves and needles.

-

For certain aspects of ecosystem-level uptake, leaf-area-based [Hg]A is relevant to assess the tree canopy accumulation capacity of Hg, typically being substantially higher in conifers than in deciduous trees.

-

In wheat, leaves are the main sink for atmospheric Hg uptake with little transport to other parts of the plant.

Original data for Hg concentrations in plant material as well as SLA data and details concerning the sampling sites in the Gothenburg area are accessible at Dryad as https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.7wm37pvsq (Pleijel et al., 2021).

HP designed the study and performed most of the data analysis in dialogue with all co-authors. Field sampling and sample preparation was made by HP (wheat, trees in the Gothenburg area), JK (trees in the Gothenburg area), GW and BN (Rwanda). HP wrote the manuscript with contributions from JK, GW, MB and MN. All co-authors participated in discussions of the manuscript and provided comments.

The contact author has declared that neither they nor their co-authors have any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We are grateful to the Gothenburg Botanical Garden and the Rwanda Development Board (RDB) for the authorization to conduct research and collect specimens in the Gothenburg Arboretum and Nyungwe National Park, respectively. We are also grateful to the Östad Foundation for making the wheat field available to our research. Many thanks are also due to Innocent Rusizana, Pierre Niyontegereje and Etienne Zibera for great assistance in the fieldwork in the Nyungwe National Park.

This research has been supported by the Svenska Forskningsrådet Formas (grant no. 2017-00696).

The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by the Gothenburg University Library.

This paper was edited by Nicolas Brüggemann and reviewed by Lena Wohlgemuth and two anonymous referees.

Assad, M., Parelle, J., Cazaux, D., Gimbert, F., Chalot, M., and Tatit-Froux, F.: Mercury uptake into poplar leaves, Chemosphere, 146, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.11.103, 2016.

Barghigiani, C., Ristori, T., and Bauleo, R.: Pinus as an atmospheric Hg biomonitor, Environ. Technol., 12, 1175–1181, https://doi.org/10.1080/09593339109385118, 1991.

Bertolotti, G. and Gialanella, S.: Review: use of conifer needles as passive samplers of inorganic pollutants in air quality monitoring, Anal. Methods, 6, 6208–6222, https://doi.org/10.1039/c4ay00172a, 2014.

Bishop, K., Shanley, J. B., Riscassi, A., de Wit, H. A., Eklöf, K., Meng, B., Mitchell, C., Osterwalder, S., Schuster, P. F., Webster, J., and Zhu, W.: Recent advances in understanding and measurement of mercury in the environment: Terrestrial Hg cycling, Sci. Total Environ., 721, 137647, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137647, 2020.

Browne, C. L. and Fang, S. C.: Uptake of mercury vapor by wheat, Plant Physiol., 61, 430–433, 1978.

Bushey, J. T., Nallana, A. G., Montesdeoca, M. R., and Driscoll, C. T.: Mercury dynamics of a northern hardwood canopy, Atmos. Environ., 42, 6905–6914, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.05.043, 2008.

De Temmerman, L., Waegeneers, N., Claeys, N., and Roeckens, E.: Comparison of concentrations of mercury in ambient air to its accumulation by leafy vegetables: An important step in terrestiral food chain analysis, Environ. Pollut., 157, 1337–1341, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2008.11.035, 2009.

Demers, J. D., Blum, J. D., and Zak, D. R.: Mercury isotopes in a forested ecosystem: Implications for air-surface exchange dynamics and the global mercury cycle, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 27, 222–238, https://doi.org/10.1002/gbc.20021, 2013.

Du, S. H. and Fang, S. C.: Catalase activity of C3 and C4 species and its relationship to mercury vapour uptake, Environ. Exp. Bot., 23, 347–353, 1983.

Ericksen, J. A., Gustin, M. S., Schoran, D. E., Johnson, D. W., Lindberg, S. E., and Coleman, J. S.: Accumulation of atmospheric mercury in forest foliage, Atmos. Environ., 37, 1613–1622, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(03)00008-6, 2003.

Feng, Z., Pang, J., Kobayashi, K., Zhu, J., and Ort, D.R.: Differential responses in two varieties of winter wheat to elevated ozone concentration under fully open-air field conditions, Glob. Change Biol. 17, 580-591, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02184.x, 2010.

Fleck, J. A., Grigal, D. F., and Nater, E. A.: Mercury uptake by trees: an observational experiment, Water Air Soil Pollut., 115, 513–523, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005194608598, 1999.

Frescholtz, T., Gustin, M. S., Schorran, D. E., and Fernandez, C. J.: Assessing the source of mercury in foliar tissue of quaking aspen, Environ. Toxicol. Chem., 22, 2114–2119, https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620220922, 2003.

Fuhrer, J., Skärby, L., and Ashmore, M. R.: Critical levels for ozone effect on vegetation in Europe, Environ. Pollut., 97, 91–106, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0269-7491(97)00067-5, 1997.

Gelang, J., Pleijel, H., Sild, E., Danielsson, H., Younis, S., and Sellden, G.: Rate and duration of grain filling in relation to flag leaf senescence and grain yield in spring wheat (Triticum aestivum) exposed to different concentrations of ozone, Physiol. Plant., 110, 366–375, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.2000.1100311.x, 2000.

Graydon, J. A., St. Louis, V. L., Hintelmann, H., Lindberg, S. E., Sandilands, K. A., Rudd, J. W., Kelly, C. A., Hall, B. D., and Mowat, L. D.: Long-term wet and dry deposition of total and methyl mercury in the remote boreal ecoregion of Canada, Environ. Sci. Technol., 42, 8345–8351, https://doi.org/10.1021/es801056j, 2008.

Grigal, D. F.: Inputs and outputs of mercury from terrestrial watersheds: a review, Environ. Rev., 10, 1–39, https://doi.org/10.1139/A01-013, 2002.

Hanson, P. J., Lindberg, S. E., Tabberer, T. A., Owens, J. G., and Kim, K. H.: Foliar exchange of mercury vapor: evidence for a compensation point, Water Air Soil Pollut., 80, 373–382, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01189687, 1995.

Hutnik, R. J., McClenahen, J. R., Long, R. P., and Davis, D. D.: Mercury Accumulation in Pinus nigra (Austrian Pine), Northeast. Nat., 21, 529–540, https://doi.org/10.1656/045.021.0402, 2014.

Jiskra, M., Sonke, J. E., Obrist, D., Bieser, J., Ebinghaus, R., Myhre, C. L., Pfaffhuber, K. A., Wängberg, I., Kyllönen, K., Worthy, D., Martin, L. G., Labuschagne, C., Mkololo, T., Ramonet, M., Magand, O., and Dommergue, A.: A vegetation control on seasonal variations in global atmospheric mercury concentrations, Nat. Geosci., 11, 244–250, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0078-8, 2018.

Johansson, J., Watne, Å. K., Karlsson, P. E., Pihl Karlsson, G., Danielsson, H., Andersson, C., and Pleijel, H.: The European heat wave of 2018 and its promotion of the ozone climate penalty in southwest Sweden, Boreal Env. Res., 25, 39–50, 2020.

Laacouri, A., Nater, E. A., and Kolka, R. K.: Distribution and uptake dynamics of mercury in leaves of common deciduous tree species in Minnesota, USA, Environ. Sci. Technol., 47, 10462–10470, https://doi.org/10.1021/es401357z, 2013.

Larcher, W.: Physiological Plant Ecology, Ecophysiology and Stress Physiology of Functional Groups, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, 2003.

Li, R., Wu, H., Ding, J., Fu, W., Gan, L., and Li, Y.: Mercury pollution in vegetables, grains and soils from areas surrounding coal-fired power plants, Sci. Rep., 7, 46545, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46545, 2017.

Lin, Y. S., Medlyn, B. E., Duursma, R. A., Prentice, I. C., Wang, H., Baig, S., Eamus, D., de Dios, V. R., Mitchell, P., Ellsworth, D. S., Op de Beeck, M., Wallin, G., Uddling, J., Tarvainen, L., Linderson, M. L., Cernusak, L. A., Nippert, J. B:, Ocheltree, T. W., Tissue, D. T., Martin-StPaul, N. K., Rogers, A., Warren, J. M., De Angelis, P., Hikosaka, K., Han, Q., Onoda, Y., Gimeno, T. E., Barton, C. V. M., Bennie, J., Bonal, D., Bosc, A., Löw, M., Macinins-Ng, C., Rey, A., Rowland, L., Setterfield, S. A., Tausz-Posch, S., Zaragoza-Castells, J., Broadmeadow, M. S. J., Drake, J. E., Freeman, M., Ghannoum, O., Hutley, L. B., Kelly, J. W., Kikuzawa, K., Kolari, P., Koyama, K., Limousin, J. M., Meir, P., Lola da Costa, A. C., Mikkelsen, T. N., Salinas, N., Sun, W. and Wingate, L.: Optimal stomatal behaviour around the world, Nature Clim. Change, 5, 459–464, 2015.

Lindberg, S., Bullock, R., Ebinghaus, R., Engstrom, D., Feng, X., Fitzgerald, W., Pirrone, N., Prestbo, E., and Seigneur, C.: A synthesis of progress and uncertainties in attributing the sources of mercury in deposition, Ambio, 36, 19–32, 2007.

Lodenius, M., Tulisalo, E., and Soltanpour-Gargari, A.: Exchange of mercury between atmosphere and vegetation under contaminated conditions, Sci. Total Environ., 304, 169–174, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-9697(02)00566-1, 2003.

Marschner, P. (Ed): Marschner's Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, Third Edition, Elsevier, London, Waltham, San Diego, 2012.

Millhollen, A. G., Gustin, M. S., and Obrist, D.: Foliar mercury accumulation and exchange for three tree species, Environ. Sci. Technol., 40, 6001–6006, https://doi.org/10.1021/es0609194, 2006.

Mulholland, B. J., Craigon, J., Black, C. R., Colls, J., Atherton, J., and Landon, G.: Impact of elevated atmospheric CO2 and O3 on gas exchange and chlorophyll content in spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), J. Exp. Bot., 48, 1853–1863, https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/48.10.1853, 1997.

Mulholland, B. J., Craigon, J., Black, C. R., Colls, J., Atherton, J., and Landon, G.: Growth, light interception and yield responses of spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) grown under elevated CO2 and O3 in open-top chambers, Glob. Change Biol. 4, 121–130, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.1998.00112.x, 1998.

Muukkonen, P.: Needle biomass turnover rates of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) derived from the needle-shed dynamics, Trees, 19, 273–279, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-004-0381-4, 2005.

Munthe, J., Hultberg, H., and Iverfeldt, Å.: Mechanisms of deposition of methylmercury and mercury to coniferous forests, Water Air Soil Pollut., 80, 363–371, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01189686, 1995.

Navrátil, T., Nováková. T., Roll, M., Shanley, J. B., Koáček, J., Kaňa, J., and Cudlín, P.: Decreasing litterfall mercury deposition in central European coniferous forests and effects of bark beetle infestation, Sci. Total Environ., 682, 213–225, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.093, 2019.

Nebel, B. and Matile, P.: Longevity and senescence of needles in Pinus cembra L, Trees, 6, 156–161, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00202431, 1992.

Niu, Z., Zhang, X., Wang, Z., and Ci, Z.: Field controlled experiments of mercury accumulation in crops from air and soil, Environ. Pollut., 159, 2684–2689, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2011.05.029, 2011.

Nyirambangutse, B., Zibera, E., Uwizeye, F. K., Nsabimana, D., Bizuru, E., Pleijel, H., Uddling, J., and Wallin, G.: Carbon stocks and dynamics at different successional stages in an Afromontane tropical forest, Biogeosciences, 14, 1285–1303, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-14-1285-2017, 2017.

Obrist, D.: Atmospheric mercury pollution due to losses of terrestrial carbon pools?, Biogeochemistry, 85, 119–123, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-007-9108-0, 2007.

Obrist, D., Kirk, J. L., Zhang, L., Sunderland, E. M., Jiskra, M., and Selin, N. E.: A review of global environmental mercury processes in response to human and natural perturbations: Changes of emission, climate, and land use, Ambio, 47, 116–140, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-017-1004-9, 2018.

Osborne, S., Mills, G., Hayes, F., Harmens, H., Gillies, D., Büker, P., and Emberson, L.: New insights into leaf physiological responses to ozone for use in crop modelling, Plants, 8, 84, https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8040084, 2019.

Pleijel, H., Klingberg, J., Nerentorp, M., Broberg, M., Nyirambangutse, B., Munthe, J., and Wallin, G.: Mercury accumulation in leaves of different plant types – the significance of tissue age and specific leaf area, Dryad, [data set], https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.7wm37pvsq, 2021.

Pokharel, A. K. and Obrist, D.: Fate of mercury in tree litter during decomposition, Biogeosciences, 8, 2507–2521, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-8-2507-2011, 2011.

Poorter, H., Niinemets, Ü., Poorter, L., Wright, I. J., and Villar, R.: Causes and consequences of variation in leaf mass per area (LMA): a meta-analysis, New Phytol., 182, 565–588, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02830.x, 2009.

Rasmussen, P. E.: Temporal variation of mercury in vegetation, Water Air Soil Pollut., 80, 1039–1042, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01189762, 1995.

Rasmussen, P. E., Mierle, G., and Nriagu, J. O.: The analysis of vegetation for total mercury, Water Air Soil Pollut., 56, 379–390, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00342285, 1991.

Reich, P. B., Uhl, C., Waiters, M. B., and Ellsworth, D. S.: Leaf lifespan as a determinant of leaf structure and function among 23 Amazonian tree species, Oecologia, 86, 16–24, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00317383, 1991.

Reich, P. B., Koike, T., Gower, S. T., and Schoettle, A. W.: Causes and consequences of variation in conifer leaf life-span, in: Ecophysiology of coniferous forests, edited by: Smith, W. K. and Hinkley, T. M., Academic press, San Diego, USA, 1995.

Reich, P. B., Oleksyn, J., Modrzynski, J., and Tjoelker, M.: Evidence that longer needle retention of spruce and pine populations at high elevations and high latitudes is largely a phenotypic response, Tree Physiol., 16, 643—647, https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/16.7.643, 1996.

Reich, P. B., Richa, R. L., Luc, X., Wang, Y. P., and Oleksynj, J.: Biogeographic variation in evergreen conifer needle longevity and impacts on boreal forest carbon cycle projections, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 111, 13703–13708, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1216054110, 2014.

Risch, M. R., DeWild, J. F., Gay, D. A., Zhang, L., Boyer, E. W., and Krabbenhoft, D. P.: 747 Atmospheric mercury deposition to forests in the eastern USA, Environ. Pollut., 228, 8–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.05.004, 2017.

Sommar, J., Zhu, W., Shang, L., Lin, C.-J., and Feng, X.: Seasonal variations in metallic mercury (Hg0) vapor exchange over biannual wheat–corn rotation cropland in the North China Plain, Biogeosciences, 13, 2029–2049, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-13-2029-2016, 2016.

Sommar, J., Osterwalder, S., and Zhu, W.: Recent advances in understanding and measurement of Hg in the environment: Surface-atmosphere exchange of gaseous elemental mercury (Hg0), Sci. Total Environ., 721, 137648, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137648, 2020.

Sprovieri, F., Pirrone, N., Bencardino, M., D'Amore, F., Angot, H., Barbante, C., Brunke, E.-G., Arcega-Cabrera, F., Cairns, W., Comero, S., Diéguez, M. D. C., Dommergue, A., Ebinghaus, R., Feng, X. B., Fu, X., Garcia, P. E., Gawlik, B. M., Hageström, U., Hansson, K., Horvat, M., Kotnik, J., Labuschagne, C., Magand, O., Martin, L., Mashyanov, N., Mkololo, T., Munthe, J., Obolkin, V., Ramirez Islas, M., Sena, F., Somerset, V., Spandow, P., Vardè, M., Walters, C., Wängberg, I., Weigelt, A., Yang, X., and Zhang, H.: Five-year records of mercury wet deposition flux at GMOS sites in the Northern and Southern hemispheres, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 2689–2708, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-2689-2017, 2017.

Stamenkovic, J. and Gustin, M. S.: Nonstomatal versus Stomatal Uptake of Atmospheric Mercury, Environ. Sci. Technol., 43, 1367–1372, https://doi.org/10.1021/es801583a, 2009.

St. Louis, V. L., Rudd, J. W. M., Kelly, C. A., Hall, B. D., Rolfhus, K. R., Scott, K. J., Lindberg, S. E., and Dong, W.: Importance of the forest canopy to fluxes of methyl mercury and total mercury to boreal ecosystems, Environ. Sci. Technol., 35, 3089–3098, https://doi.org/10.1021/es001924p, 2001.

Sun, G., Feng, X., Yin, R., Zhao, H., Zhang, L., Sommar, J., Li, Z., and Zhang, H.: Corn (Zea mays L.): A low methylmercury staple cereal source and an important biospheric sink of atmospheric mercury, and health risk assessment, Environ. Int., 131, 104971, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.104971, 2019.

UN Environment: Global Mercury Assessment Report 2018, UN Environmental Programme, Chemicals and Health Branch Geneva, Switzerland, ISBN 978-92-807-3744-8, 2019.

Wang, X., Bao, Z., Lin, C.-J., Yuan, W., and Feng, X.: Assessment of global mercury deposition through litterfall, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 8548–8557, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b06351, 2016.

Wohlgemuth, L., Osterwalder, S., Joseph, C., Kahmen, A., Hoch, G., Alewell, C., and Jiskra, M.: A bottom-up quantification of foliar mercury uptake fluxes across Europe, Biogeosciences, 17, 6441–6456, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-6441-2020, 2020.

Wyttenbach, A. and Tobler, L.: The seasonal variation of 20 elements in 1st and 2nd year needles of Norway spruce, Picea abies (L.) Karst, Trees, 2, 52–64, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01196345, 1988.

Wyttenbach, A. and Tobler, L.: The concentrations of Fe, Zn and Co in successive needle age classes of Norway spruce [Picea abies (L.) Karst.], Trees, 14, 198–205, https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00009763, 2000.

Yang, Y., Yanai, R. D., Driscoll, C. T., Montesdeoca, M., and Smith, K. T.: Concentration and content of mercury in bark, wood, and leaves in hardwoods and conifers in four forested sites in the northeastern USA, PLoS ONE, 13, e0196293, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196293, 2018.

Yuan, W., Sommar, J., Lin, C. J., Wang, X., Li, K., Liu, Y., Zhang, H., Lu, Z., Wu, C., and Feng, X.: Stable isotope evidence shows re-emission of elemental mercury vapour occurring after reductive loss from foliage, Environ. Sci. Technol., 53, 651-660, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b04865, 2019.

Zhou, J., Obrist, D., Dastoor, A., Jiskra, M., and Ryjkov, A.: Vegetation uptake of mercury and impacts on global cycling. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 269–284, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-021-00146-y, 2021.