the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Stable isotopes of nitrate reveal different nitrogen processing mechanisms in streams across a land use gradient during wet and dry periods

Wei Wen Wong

Jesse Pottage

Fiona Y. Warry

Paul Reich

Keryn L. Roberts

Michael R. Grace

Perran L. M. Cook

Understanding the relationship between land use and the dynamics of nitrate () is the key to constrain sources of export in order to aid effective management of waterways. In this study, isotopic compositions of (δ15N– and δ18O–) were used to elucidate the effects of land use (agriculture in particular) and rainfall on the major sources and sinks of within the Western Port catchment, Victoria, Australia. This study is one of the very few studies carried out in temperate regions with highly stochastic rainfall patterns, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of the applications of isotopes in catchment ecosystems with different climatic conditions. Longitudinal samples were collected from five streams with different agriculture land use intensities on five occasions – three during dry periods and two during wet periods. At the catchment scale, we observed significant positive relationships between concentrations (p < 0.05), δ15N– (p < 0.01) and percentage agriculture (particularly during the wet period), reflecting the dominance of anthropogenic nitrogen inputs within the catchment. Different rainfall conditions appeared to be major controls on the predominance of the sources and transformation processes of in our study sites. Artificial fertiliser was the dominant source of during the wet periods. In addition to artificial fertiliser, nitrified organic matter in sediment was also an apparent source of to the surface water during the dry periods. Denitrification was prevalent during the wet periods, while uptake of by plants or algae was only observed during the dry periods in two streams. The outcome of this study suggests that effective reduction of load to the streams can only be achieved by prioritising management strategies based on different rainfall conditions.

- Article

(1553 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(214 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Anthropogenic sources of from catchments can pose substantial risk to the quality of freshwater ecosystems (Vitousek et al., 1997; Galloway et al., 2004). Over-enrichment of in freshwater systems is a major factor in development of algal blooms which often promote bottom water hypoxia and anoxia. Such anoxia intensifies nutrient recycling and can lead to disruption of ecosystem functioning and ultimately loss of biodiversity (Galloway et al., 2004; Carmago and Alonso, 2006). Freshwater streams are often sites for enhanced denitrification (Peterson et al., 2001; Barnes and Raymond, 2010). However, when loading from the catchment exceeds the removal and retention capacity of the streams, is transported to downstream receiving waters including estuaries and coastal embayments, which are often nitrogen-limited, further compounding the problem of eutrophication.

Understanding the sources, transport and sinks of is critical, particularly in planning and setting guidelines for better management of the waterways (Xue et al., 2009). Establishing the link between land use and the biogeochemistry of provides fundamental information to help develop reduction and watershed restoration strategies (Kaushal et al., 2011). To date, the most promising tool to investigate the sources and sinks of are the dual isotopic compositions of at natural abundance level (expressed as δ15N– and δ18O– in ‰). Preferential utilisation of lighter isotopes (14N and 16O) over heavier isotopes (15N and 18O) leads to distinctive isotopic signatures that differentiate the various sources/end members (e.g. inorganic and organic fertiliser, animal manure, atmospheric deposition) and the predictable kinetic fractionation effect when undergoes different biological processes (e.g. nitrogen fixation and denitrification). For instance, numerous previous culture-based experiments revealed that denitrification and phytoplankton assimilation fractionate N and O isotopes equally (1 : 1 pattern), leaving behind that is enriched in both 15N and 18O (Fry, 2006). Simultaneous measurement of δ15N– and δ18O– also provides complementary information on the cycling of in the environment. δ18O– is a more effective proxy of internal cycling of (i.e. assimilation, mineralisation and nitrification) compared to δ15N–. This is because during assimilation and mineralisation, N atoms are recycled between fixed N pools and the O atoms are removed and replaced by nitrification (Sigman et al., 2009; Buchwald et al., 2012).

In addition to constraining budget and N cycling in various environmental settings, previous studies have also utilised the dual isotopic signatures of to study the effects of different land uses on the pool of in headwater streams (Barnes and Raymond, 2010; Sebilo et al., 2003), creeks (Danielescu and MacQuarrie, 2013) and large rivers (Voss et al., 2006; Battaglin et al., 2001). Barnes and Raymond (2010) for example found that both δ15N– and δ18O– varied significantly between urban, agricultural and forested areas in the Connecticut River watershed, USA. Several other investigators (Mueller et al., 2016; Mayer et al., 2002) showed positive relationships between δ15N– and the percent of agricultural land in their study area, indicating the applicability of δ15N– and δ18O– to distinguish originating from different land uses. Danielescu and MacQuarrie (2013) and Chang et al. (2002) on the other hand found no correlations between isotopes and land use intensities in the Trout River catchment and the Mississippi River basin, respectively. These studies attributed the lack of correlation to catchment size (Danielescu and MacQuarrie, 2013) and the homogeneity of land use (Chang et al., 2002).

Despite the extensive application of isotopes to study the transport of terrestrial to the tributaries in the catchment, the majority of these studies were carried out in the United States and western Europe where climatic conditions, for example temperature and rainfall patterns, are different compared to that in the Southern Hemisphere. The Southern Hemisphere tends to have more sporadic and variable rainfall patterns compared to the Northern Hemisphere, and Australia is an example of this. The variable rainfall patterns can modulate different efficiencies of denitrification in soils and thus different fractionation effects to the residual pool (Chien et al., 1977; Billy et al., 2010). However, the lack of isotope studies in the Southern Hemisphere (Ohte, 2013) impedes a more thorough understanding of dynamics within catchment ecosystems.

Most previous studies investigating the relationship between land use and export using δ15N– and δ18O– have either focused on the seasonal or spatial variations in one stream, or used multiple streams with one site per stream (i.e. Mayer et al., 2002; Yevenes et al., 2016). Far fewer studies have incorporated longitudinal sampling of multiple streams over multiple seasons. Nitrate concentrations and concomitant isotopic signatures can change substantially, not only spatially but temporally. Changes in hydrological and physicochemical (notably temperature) conditions of a river can affect the relative contribution of different sources of and the seasonal predominance of a specific source (Kaushal et al., 2011; Panno et al., 2008). In some studies (e.g. Riha et al., 2014; Kaushal et al., 2011), denitrification and assimilation by plants and algae have been reported to be more prominent during the dry seasons compared to the wet seasons, but in other studies (e.g. Murdiyarso et al., 2010; Enanga et al., 2016) denitrification appeared to be more prevalent during the wet seasons as precipitation induces saturation of soils, resulting in oxygen depletion and thereby low redox potentials that favour denitrification. As such, if spatial and temporal variations of δ15N– and δ18O– are not considered thoroughly in a sampling regime, it can lead to misinterpretation of the origin and fate of . Proper consideration of the temporal variability of isotope signatures and transformation are particularly pertinent in catchments with highly stochastic rainfall patterns, such as Australia.

In this study, we examine both spatial and temporal variations of concentrations and isotopic compositions within and between five streams in five catchments spanning an agricultural land use gradient, enabling us to evaluate (1) the effects of agriculture land use on the sources and transformation processes of and (2) the effects of rainfall on the predominance of the sources and fate of in the catchments.

2.1 Study area

This study was undertaken using five major streams (Bass River, Lang Lang River, Bunyip River, Watsons Creek and Toomuc Creek) draining into Western Port (Fig. 1) which lies approximately 75 km south-east of Melbourne, Australia. Western Port is a nitrogen-limited coastal embayment recognised as a Ramsar site for migratory birds. The catchments in Western Port contain three marine national parks, highlighting its environmental and ecological significance. The catchments cover an area of 3721 km2 with land uses ranging from semi-pristine/state forest to high-density residential and intense agricultural activities. The area experiences a temperate climate with average annual rainfall ranging from 750 mm along the coast to 1200 mm in the northern highlands. Mean monthly rainfall was about 20 and 53 mm in 2014 and 2015, respectively (Australian Bureau of Meteorology 2014 – http://www.bom.gov.au/, last access: 30 Apri 2016).

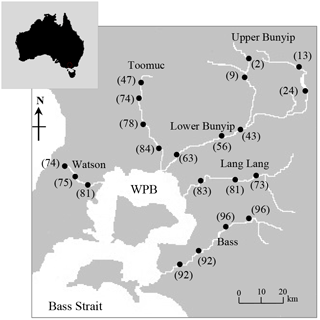

Figure 1Map of Western Port Bay (WPB) in southern Victoria, Australia, and major rivers discharging into WPB. Closed circles represent sampling sites where surface water samples were obtained. Values in parentheses represent the % agriculture area in the catchment.

The catchment overlies a multi-layered combined aquifer system. The main aquifer consists of Quaternary alluvial and dune deposit (average thickness of < 7 m) as well as Baxter, Sherwood and Yallock formations (average thickness between 20 and 175 m). These aquifers are generally unconfined with radial groundwater flow direction from the basin edge towards Western Port Bay. The hydrogeology of Western Port can be found in Carillo-Rivera (1975).

Five longitudinal surveys were carried out between April 2014 and May 2015, two during wet periods (14 April 2014; 15 May 2015 – the total rainfall for 5 days before sampling was between 45 and 65 mm) and three during dry periods (8 April 2014; 22 May 2014; 21 March 2015 – the total rainfall for 5 to 10 days before sampling was < 5 mm). A total of 21 sampling sites indicated in Fig. 1 were selected across a gradient of catchment land use intensity. The five streams were selected based on the extent and distribution of land use types between and within each stream sub-catchment (see Fig. S1 in the Supplement), thus enabling comparisons within and between the streams.

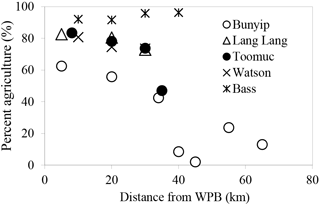

In this study, catchment-intensive agriculture was used as a predictor of land use intensity in the catchment. These data were obtained from the National Environmental Stream Attributes database v1.1 (Stein et al., 2014), Bureau of Rural Sciences' 2005/06 Land Use of Australia V4 maps (http://www.agriculture.gov.au/abares/aclump, last access: 30 April 2016) and Victorian Resources Online (VRO). In the context of this study, the catchment-intensive agriculture variable is termed “percentage agriculture”. This term represents the percentage of the catchment subject to intensive animal production, intensive plant production (horticulture and irrigated cropping) and grazing of modified pastures. This variable also reflects the integrated diffuse sources of nutrients derived from intense agriculture including animal manure and inorganic fertilisers. The percentage agriculture for the sampling sites ranged between 2 and 96 % with the Bass River (94±2 %) > Lang Lang (79±5 %) > Watsons (76±4 %) > Toomuc (71±16 %) > Bunyip (upper Bunyip: 12±9 %; lower Bunyip: 54±10 %; Fig. 2). For the purpose of this study, Bunyip is divided into two sectors (upper and lower Bunyip) based on the proximity of the sampling sites (Fig. 1) and the percentage of land use. All the sampling sites in the upper Bunyip are situated in areas with > 30 % forestation (see Fig. S1). In general, the percentage agriculture decreases with increased distance from Western Port Bay (WPB) for all the streams except Bass River. There is an increase of about 2 % in percentage agriculture for Bass River with increased distance from WPB. Watsons Creek has the largest percentage of market gardens (∼ 91 %).

2.2 Sample collection and preservation

Water quality parameters (pH, electrical conductivity, turbidity, dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration and water temperature) were measured using a calibrated Horiba U-10 multimeter. Stream samples were collected for the analyses of dissolved inorganic nutrients (DIN) (ammonium, ; and nitrite, ), dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and isotopes (δ15N– and δ18O–). These samples were filtered on site using 0.2 µm Pall Supor® membrane disc filters. Filtered DOC samples were acidified to pH < 2 with concentrated hydrochloric acid. Samples for δ18O–H2O were collected directly from the streams without filtering. Sediment samples were collected from the bottom of the rivers and were kept in zip-lock bags. All samples were stored and transported on ice until they were refrigerated (nutrient samples were frozen) in the laboratory. In addition to stream water and sediment, we also collected four samples of artificial/inorganic fertiliser (from the fertiliser distributor in the area) and five of cow manure (from local farmers).

2.3 DIN and DOC concentration measurements

All chemical analyses were performed within 1–2 weeks of sample collection except for isotope analyses (within 2 months). The concentrations of , , and were determined spectrophotometrically using a Lachat QuikChem 8000 Flow Injection Analyzer (FIA) following standard procedures (APHA 2005). DOC concentrations were determined using a Shimadzu TOC-5000 Total Organic Carbon analyser. Analysis of standard reference materials indicated the accuracy of the spectrophotometric analyses and the TOC analyser was always within 2 % relative error.

2.4 Isotopic analyses

The samples for δ15N– and δ18O– were analysed using the chemical azide method based on the procedure outlined in McIlvin et al. (2005). In brief, NOx ( + ) was quantitatively converted to using cadmium reduction and then to N2O using sodium azide. The initial concentrations were insignificant, typically < 1 % relative to . Hence, the influence of δ15N– was negligible and the measured δ15N–N2O represents the signature of δ15N–. The resultant N2O was then analysed on a Hydra 20–22 continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (CF-IRMS; Sercon Ltd., UK) interfaced to a cryoprep system (Sercon Ltd., UK). Nitrogen and oxygen isotope ratios are reported in per mil (‰) relative to atmospheric air (AIR) and Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW), respectively. The external reproducibility of the isotopic analyses lies within ±0.5 ‰ for δ15N and ±0.3 ‰ for δ18O. The international reference materials used were USGS32, USGS 34, USGS 35 and IAEA-. Lab-internal standards (K and Na) with pre-determined isotopic values were also processed the same way as the samples to check on the efficiency of the analytical method. The δ18O–H2O values were measured via equilibration with He–CO2 at 32 ∘C for 24 to 48 h in a Finnigan MAT Gas Bench and then analysed using CF-IRMS. The δ18O–H2O values were referenced to internal laboratory standards, which were calibrated using VSMOW and Standard Light Antarctic Precipitation. Measurement of two sets of triplicate samples in every run showed a precision of 0.2 ‰ for δ18O–H2O. Sediment samples for the analysis of δ15N of total nitrogen were dried at 60 ∘C before being analysed on the 20–22 CF-IRMS coupled to an elemental analyser (Sercon Ltd., UK). The precision of the elemental analysis and δ15N was 0.5 µg and ±0.2 ‰ (n=5), respectively.

2.5 Data analysis

The relationships between percentage agriculture and surface water concentrations were assessed using linear regression. Percentage agriculture was the predictor variable. concentration and δ15N– were response variables. Relationships between δ15N– and concentration as well as δ18O– and δ15N– were assessed using Pearson's correlation. The isotopes' response variables were assessed at two spatial scales – individual stream and catchment scale. The catchment scale integrates data from all five studied streams. Any graphical patterns or relationships derived from using these scales represent processes that occur somewhere in the catchment either in the streams or prior to entering the streams with data from the individual stream likely to represent more localised processes to that particular stream.

The streams were oxic throughout the course of our study period with % DO saturation between 60 and 110 % (see Fig. S2 in the Supplement). There was no apparent spatial and temporal variation in DO; however, % DO saturation was slightly lower during the dry periods (average of 73 ± 20 %) compared to the wet periods (average of 82 ± 12 %). Temperature was also relatively consistent, with an average of 13 ± 2 ∘C. Ammonium concentration was generally low (< 4 µM) except during the wet periods in Bunyip (∼ 7 µM), Lang Lang (∼ 21 µM) and Bass (∼ 29 µM). DOC concentrations were typically 0.8±0.4 mM. Nitrite concentrations were also low in all the streams, ranging between 0.1 and 0.4 µmol L−1.

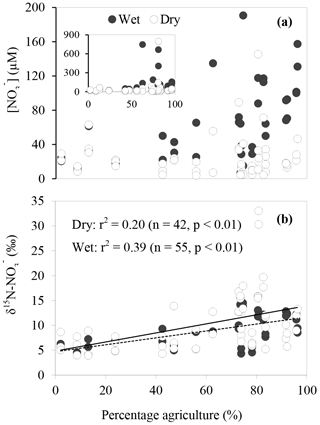

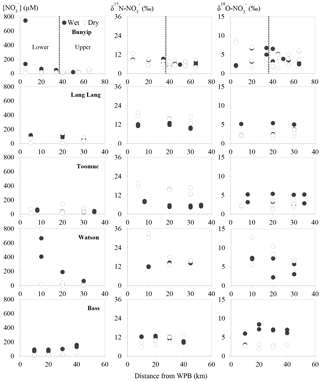

The spatial and temporal variations of concentration, δ15N and δ18O across the sites are shown in Fig. 3. concentrations ranged between 7 and 790 µM with averages of 21±15, 50±130, 64±43, 71±43 and 190±280 µM for Toomuc, Bunyip, Bass, Lang Lang and Watsons, respectively. The lowest concentration was observed in the lower Bunyip (4 µM), while the highest concentration was observed in Watsons Creek (790 µM) at the most downstream site. Nitrate concentrations were generally higher during the wet periods compared to the dry periods in all streams (Fig. 3). During the wet periods, concentrations typically followed an increasing trend heading downstream except for the Bass River which exhibited the opposite trend with lower concentrations at downstream sites. During the dry periods, only the Bunyip and Bass rivers showed apparent longitudinal patterns in concentrations, with decreasing concentrations moving downstream in both. Sites with high-percentage agriculture generally also exhibited high concentrations (Fig. 4), particularly during the wet periods.

Figure 3Spatial and temporal variations of nitrate concentrations and isotope values. Closed circles represent data obtained during the wet periods. Open circles represent data obtained during the dry periods.

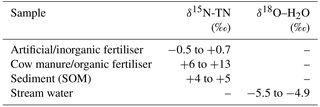

Overall, δ15N of the riverine spanned a wide range (+4 to +33 ‰). Approximately 62 % of the obtained δ15N– values fell below +10 ‰. More enriched δ15N– values (> +10 ‰) were typically observed during the dry periods and were coincident with a high-percentage agriculture (Fig. 4). Among all sites, δ15N– values in the Bunyip and Bass were relatively depleted (+4 to +12 ‰ for Bunyip and +10 to 12 ‰ for Bass), with the lower range found at upper Bunyip (+4 to +8 ‰). There was no discernible pattern spatially or temporally in δ18O–, except that higher values were found in Lang Lang and Bass during the wet periods, with +4 to +6 and +5 to +9 ‰, respectively, compared to the dry periods (< +4 ‰). For other sampling sites, δ18O– ranged between +2 and +13 ‰. The isotope compositions of sediment, water, artificial fertiliser and cow manure/organic fertiliser are presented in Table 1. The δ15N-TN of three potential sources – artificial fertiliser, organic fertiliser and soil organic matter – ranged from −0.5 to +0.7, +6 to +13 and +4 to +5 ‰, respectively.

4.1 Potential sources of

There are three major potential sources of in the catchments – artificial fertiliser, cow manure/organic fertiliser and soil organic matter (SOM) – see Table 1 for the δ15N-TN values. The average δ15N-TN value of soils is used to directly represent the soil organic portion as most of the nitrogen in soils is generally bound in organic forms. Nitrogen isotope of the produced from the potential end members usually retains the signature of the δ15N-TN as a result of tight coupling between mineralisation (production of ammonium from organic matter) and nitrification (oxidation of ammonium to ). The δ18O of generated by nitrification of these sources (δ18O–final) is, however, decoupled from δ15N–. As shown in Eq. (1), which is adapted from Buchwald et al. (2012), δ18O–final relies on the oxygen isotope of water (δ18O–H2O), oxygen isotope of dissolved oxygen (δ18O–O2), kinetic isotope fractionation associated with incorporation of oxygen during ammonia oxidation (18εk-O2), kinetic isotope fractionation associated with incorporation of oxygen from water during ammonia oxidation (18εk-H2O,1) and nitrite oxidation (18εk-H2O,2), equilibrium isotope effect associated with oxygen isotope exchange between nitrite and water (18εeq) as well as the fraction of nitrite oxygen atoms exchanged with H2O during ammonia oxidation (xAO) (Casciotti et al., 2010; Buchwald et al., 2012). To date, 18εk-O2 and 18εk-H2O cannot be separated. Previous culture studies have reported the overall 18εk-O2 + 18εk-H2O,1 to range between 17.9 and 37.6 ‰ (Casciotti et al., 2010), while 18εk-H2O,2 ranged from 12.8 to 18.2 ‰ (Buchwald and Casciotti, 2010). These values together with a 18εeq value of 14 ‰, average δ18O–H2O of −5.3 ‰ and δ18O–O2 of 23.5 ‰ were used to calculate the maximum and minimum estimates of the δ18O of newly produced from nitrification. The minimum estimate of δ18O–final was calculated using the lower range of 18εk-O2 + 18εk-H2O,1 (17.9 ‰) and 18εk-H2O,2 (12.8 ‰), while the maximum estimate was calculated using the upper range of 18εk-O2 + 18εk-H2O,1 (37.6 ‰) and 18εk-H2O,2 (18.2 ‰). Based on the assumptions that ammonia was fully oxidised to (as no accumulation of was observed during our study period) and there was complete exchange of oxygen isotope between nitrite and H2O during ammonia oxidation (xAO=1), which likely characterises most freshwater systems (Casciotti et al., 2007; Snider et al., 2010; Buchwald and Casciotti, 2013); we calculated the δ18O of produced from nitrification to be between −2.03 and −0.23 ‰.

The δ15N-TN of cow manure (+6 to +13 ‰) was most variable compared to other end members. This variation reflects the extent of volatilisation, a highly fractionating process. Volatilisation can cause a fractionation effect of up to 25 ‰ in the residual (Hübner, 1986). As such, the lower value of +6 ‰ indicates a relatively fresh manure sample and is assumed to represent the initial δ15N of the cow manure before undergoing any extensive fractionation.

Atmospheric deposition did not appear to be an important source of in this study based on the relatively depleted δ18O– values (ranged from +2 to +8 ‰ during the wet periods, and from +1.5 to +13 ‰ during the dry periods) of the riverine samples. The δ18O– of atmospheric deposition were reported to range from +60 to +95 ‰ in the literature (Kendall, 2007; Elliott et al., 2007; Pardo et al., 2004). Similarly, groundwater was not considered as an important source of to the streams based on the low concentrations (∼ 0.7 to 7.0 µM) reported in previous studies (Water Information System Online; http://data.water.vic.gov.au/monitoring.htm, last access: 29 April 2016).

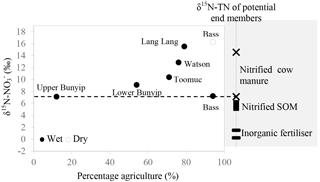

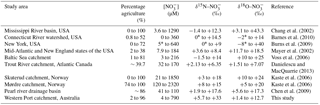

4.2 General characteristics of in the streams

Agricultural land use (i.e. market gardens and cattle rearing) appeared to influence concentrations in our study sites. As shown in Fig. 4a, during the wet periods, high concentrations (> 40 µM) were particularly observed at sites with more than 70 % agricultural land use. During the dry periods, although concentrations were generally lower than 36 µM, the outliers were observed at sites with more than 70 % agricultural land use. Similarly, enriched δ15N– in the streams were mainly found at sites with high-percentage agricultural land use (between 75 and 85 %) for both dry and wet periods, suggesting that enriched δ15N– in the stream originated from agricultural activities. In fact, the most enriched δ15N– values (> 30 ‰) were observed at the most downstream site of Watsons Creek which has the largest percentage of market gardens (although the total agricultural area is not the highest amongst all the studied sites). We also observed a significant positive relationship between δ15N– and percentage agriculture during the wet periods (r2=0.39, p < 0.01; Fig. 4b). This further supports the contention that agricultural activities were the main control of the δ15N– in the streams. Other researchers (e.g. Mayer et al., 2002; Voss et al., 2006) have also documented similar trends of enriched δ15N– with increasing percentage agriculture. For example, Harrington et al. (1998), Mayer et al. (2002) and Voss et al. (2006) observed highly significant positive relationships between percentage agriculture land area and δ15N– with r2∼0.7. However, these studies showed comparatively narrower and more depleted ranges of δ15N–, with 2.0 to 7.3, 4 to 8 and −0.1 to 8.3 ‰, respectively, suggesting more subtle changes in δ15N– over a large span of agriculture land areas in these studies compared to our study (see Table 2).

Given that none of the predicted sources of in the Western Port catchment exhibited an initial δ15N– of more than +6 ‰ (see Table 1), the isotopically enriched as well as the variability of concentrations observed in this study were consequences of a series of transformation processes. Hence, we propose the following factors to explain the heavy isotopes and the different concentrations across different periods observed in our study.

-

During the wet period when surface runoff was conspicuous and residence time of the water column was low, in-stream was comprised mainly of externally derived (i.e. fertilisers, manure and soil organic matter) and there was limited in-stream processing of these . The high concentrations and the heavy δ15N– values reflect the occurrence of mineralisation, nitrification and subsequent preferential denitrification of the isotopically lighter source/s in either the waterlogged soil or in the soil zone underneath the market gardens before transport to the streams through surface runoff.

-

During the dry periods when surface runoff was negligible and residence time of the water column was high, there was minimal introduction of external into the streams and in-stream processing of was more apparent than during the wet periods. In addition to mineralisation and nitrification, volatilisation and assimilation by plant and algae were highly likely to occur in the stream, further reducing the concentration and further fractionating the isotopic signature of .

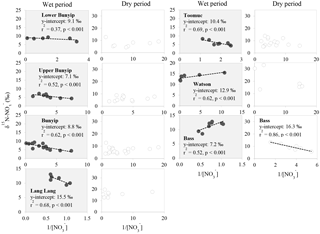

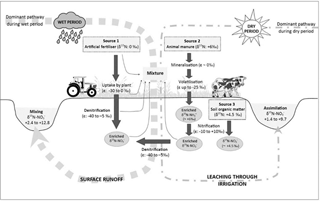

These processes are conceptualised in Fig. 5 and are corroborated in the following discussion using two graphical methods: the Keeling plot and the isotope biplot. In an agricultural watershed, the co-existence of multiple sources and transformation processes can potentially complicate the use of isotopes as tracers of its origin. Keeling plots (δ15N– vs. 1/[]) are generally very useful to distinguish between mixing and fractionation (i.e. assimilation and bacterial denitrification) processes (Kendall et al., 1998). The latter typically results in progressively increasing δ15N– values as concentrations decrease and yields a curved Keeling plot. Meanwhile, mixing of from two or more sources can result in a concomitant increase in both δ15N– and concentrations and results in a straight line on the Keeling plot (Kendall et al., 1998). A biplot (δ18O– vs. δ15N–) on the other hand is a proven diagnostic method to elucidate the presence of two isotope fractionating processes: assimilation and denitrification.

Figure 5Conceptual diagram illustrating the sources and processes of during the wet and dry periods in the Western Port catchment. The values of the enrichment factor (ε) were obtained from the literature (Kendall et al., 2007) to indicate the relative contribution of the transformation processes to the isotopic compositions of the residual .

4.3 Key controlling processes of nitrate during the wet periods

In-stream processing of was not evident during the wet periods based on the lack of relationships between δ18O– and [] as well as between δ18O– and δ15N– for the individual streams (shown in Supplement Fig. S3). If denitrification was dominant, both δ15N– and δ18O– values are expected to increase in a 1 : 1 pattern at low concentration – a trend which has been proven by numerous culture-based experiments to indicate the occurrence of denitrification (Granger and Wankel, 2016). In addition, high DO in the water column ruled out the possibility of pelagic denitrification.

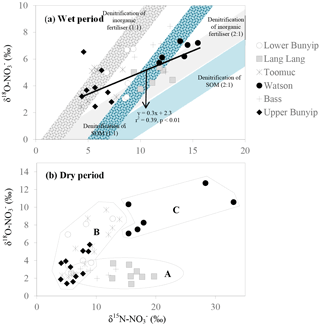

Careful examination of the Keeling plots for individual streams (Fig. 6) revealed that during the wet periods, concentrations were significantly and linearly correlated with 1/[] in all the streams. These relationships strongly suggest mixing between two sources (with distinctive isotopic signatures) as the dominant process regulating the isotopic composition of the residual in the streams during the wet periods. The different trends in the Keeling plots (Fig. 6) for individual streams indicate that the isotopic signature of the dominant source varied temporally and spatially across the catchments. Negative trends on the Keeling plots for Bunyip, Lang Lang and Toomuc (Fig. 6) clearly show that the dominant source was isotopically enriched (above +10 ‰ for Bunyip and Toomuc and +14 ‰ for Lang Lang), while the positive trends on the Keeling plots for Bass and Watsons show that the dominant source was more isotopically depleted (less than +8 ‰ for Bass and less than +9 ‰ for Watsons). Nevertheless, the isotopic signatures of the dominant source indicated by the y-intercepts of the Keeling plots were a lot more enriched than the initial δ15N– of all three pre-identified end members. Interestingly, these δ15N– values increased with percentage agriculture, except for Bass (Fig. 7). The fact that there was a clear fractionation pattern (∼ 2 : 1) when integrating the isotope values of all the streams (catchment scale) suggests that denitrification was still prevalent during the wet periods (Fig. 8a), but this process was more likely to occur prior to entering the streams via surface runoff. We explain these observations on the basis that increased rainfall created a “hot moment” in the soil whereby organic matter mineralisation and nitrification were stimulated, followed by denitrification within the waterlogged soil. Waterlogging can result in root anoxia and increased denitrification, leading to significant isotopic enrichment of the residual (Chien et al., 1977; Billy et al., 2010), which was then washed into the streams. The extent of this process (mineralisation–nitrification–denitrification) was greatest at Bass and Watsons, sites with the highest agricultural activity (Fig. 8a). Based on Fig. 8a, the isotope enrichments of the riverine followed the denitrification trend of the artificial fertiliser and the isotopes were distributed in between the denitrification ranges of both artificial fertiliser and SOM, suggesting the important contributions of these two sources during the wet periods.

Figure 7Relationship between δ15N– of the dominant initial source (indicated by the y-intercept of the Keeling plots; Fig. 6) and percentage agriculture during wet periods. Data for the Bass-dry period were also presented because only the Keeling plot for the Bass-dry period indicates mixing between different sources. The shaded area represents the δ15N– of the potential end members.

In fact, the deviation of the δ15N– : δ18O– from the 1 : 1 trend to 2 : 1 corroborates the co-existence of other processes in our system (i.e. nitrification and/or anammox) in addition to denitrification. Based on the multi-process model developed by Granger and Wankel (2016), the negative deflation of the denitrification trend (1 : 1) is strongly driven by concurrent production catalysed by nitrification and/or anammox (Granger and Wankel, 2016) when the rate of reduction to (via denitrification) is higher than the rate of oxidation to (via nitrification and/or anammox). A higher reduction rate of to tends to create a pool with enriched δ15N due to isotopic fractionation (0 to 20 ‰) during the reduction of to N2 (the last step of denitrification). The subsequent oxidation of the δ15N-enriched leads to the production of which is isotopically more enriched than denitrified owing to inverse kinetic fractionation effects (−35 to 0 ‰), driving the negative deviation of δ18O– : δ15N– from the 1 : 1 trend (Granger and Wankel, 2016). During the wet periods, simultaneous occurrence of these three processes (nitrification, annamox and denitrification) was plausible due to the redox dynamics in the waterlogged soil zone. Downward percolation of oxygenated rain water could induce nitrification while denitrification and anammox could be promoted in the anoxic interstitial spaces of the waterlogged soil zone.

4.4 Key controlling processes of nitrate during the dry periods

Figure 8Biplot of δ15N– vs. δ18O– for (a) wet and (b) dry periods. The blue shaded area represents possible isotopic compositions of denitrified originated from SOM (δ15N: +4.5 ‰). The grey shaded area represents the possible isotopic composition of denitrified originated from inorganic fertiliser (δ15N–: +0.1 ‰). The δ18O– used were −2.3 and ±0.23 ‰ representing the minimum and maximum estimates of δ18O of nitrified , respectively. The shaded areas were plotted based on the theoretical 1 : 1 and 2 : 1 denitrification relationships between δ15N– and δ18O– (Kendall et al., 2007).

Figure 9Biplot of δ15N– vs. δ18O– for Bunyip and Toomuc (group B data in Fig. 8b). Shaded areas represent theoretical assimilation trends for cow manure, SOM and inorganic fertiliser. The maximum and minimum starting values for δ18O– were estimated from Eq. (1). The starting δ15N– is the δ15N-TN value of respective end member. Solid and dotted lines represent the assimilation trends for Bunyip (both lower and upper Bunyip) and Toomuc, respectively. Assimilation rather than denitrification was considered a more plausible process controlling the distribution pattern for the group B dataset as the water column was oxic throughout the study period.

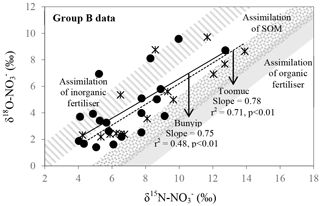

Unlike the wet periods, only in the Bass River showed an apparent relationship with δ15N– (Fig. 6) during the dry periods. There was no obvious relationships between δ15N– and 1/[] for all other systems during the dry periods limiting the interpretation available from the Keeling plots. This also suggests that mixing between two end members alone is inadequate to explain the variability of δ15N– during the dry periods. In general, during the dry periods, none of the samples show a noticeable pattern of denitrification on a biplot of δ18O vs. δ15N (Fig. 8b). The isotopic composition of the riverine appeared to be clustered into three groups (A, B and C in Fig. 8b).

in group A showed consistent δ18O but variable δ15N. This is demonstrated by the Lang Lang and Bass, coincident with the highest percentage of agriculture. The consistent δ18O (δ18O of ∼ 2.5 ‰) shows the importance of nitrification (δ18O of ∼ −2.03 to −0.23 ‰) and at the same time ruled out the occurrence of denitrification and assimilation. In the absence of the removal processes, the heavy and variable δ15N– values (+6 to +20 ‰) imply that animal manure was an apparent source of during the dry periods for Lang Lang and Bass. This is because volatilisation of 14N ammonia from the animal manure over time can lead to enrichment of 15N in the residual to > +20 ‰ (Bateman and Kelly, 2007) which can subsequently be nitrified to produce isotopically enriched without affecting its δ18O–. Tight coupling between mineralisation and nitrification results in retaining the isotopic signature of the residual (Deutsch et al., 2009) in the manure. Hence, it is not surprising that δ15N– > +13 ‰ in the group A dataset is indicative of nitrified “aged” animal manure. Because of the huge variability in the fractionation effect of ammonia volatilisation, it is difficult to affix an average δ15N value to represent the isotopic signature of this end member. As such, apportioning the relative contribution of nitrified manure versus other sources (nitrified organic matter in the sediment and inorganic fertiliser) is not possible.

Table 2Comparison of concentrations and isotopes across different systems reported in the literature.

* Values estimated from presented figures might not accurately represent the actual data.

in group B has variable δ15N and δ18O values as shown by Bunyip and Toomuc. This could be attributed to isotopic fractionation during plant and/or algae uptake of as substantiated by the parallel increase in δ18O– vs. δ15N– (Fig. 9). Denitrification was ruled out due to high levels of dissolved oxygen in the water column. Close convergence of the linear relationships onto the theoretical assimilation trends of the nitrified artificial fertiliser and SOM (Fig. 9) reiterate the dominant contribution of these sources to the riverine during the dry periods. It is worth noting that the initial δ18O of nitrified was estimated assuming full O isotopic equilibration between and H2O. Partial O isotope disequilibrium which was possible could affect the initial δ18O signature of nitrified . If this happened, the minimum estimate of δ18O of nitrified could be more depleted and the overall linear relationship of δ18O– : δ15N– would shift, resulting in more obvious contribution of artificial fertiliser, SOM and possibly organic fertiliser (Fig. 9). This scenario emphasises the sensitivity of the initial δ18O of nitrified in determining the relative contribution of multiple sources in the catchment.

in group C comprised the most enriched δ15N and δ18O in the entire dataset (Fig. 8). These isotope values were observed in Watsons Creek which has the highest percentage of market gardens. These samples were collected when the creek was not flowing, hence the enriched δ15N and δ18O values could be indications of repeated cycles of internal processes (i.e. volatilisation, nitrification, denitrification and assimilation) in the same pool which enriched the N isotope but had slight effects on the O isotope of .

Although the isotope values during the dry periods appeared to be more likely controlled by artificial fertiliser and SOM, the contribution from organic fertiliser cannot be excluded. As mentioned in the preceding text, most of the fertiliser-derived was denitrified in the catchment during the wet periods creating an artefact of heavy isotopes in the streams. This could exhibit a similar enriched isotopic composition as the volatilised manure (particularly if there was disequilibrium of O isotope between and H2O). Overlapping of these isotopic values made it difficult to distinguish between all the three sources – a disadvantage of using isotopes in a system where multiple sources and transformation processes coexist.

This study highlights the effect of rainfall conditions on the predominance of sources and transformation processes of on both individual stream and catchment scale. The significant positive relationships between percentage agriculture and concentrations (r2=0.29; p < 0.05) as well as δ15N– (r2=0.39; p < 0.01) particularly during the wet period showed that enriched concentrations and δ15N– values resulted from agricultural activities. The dual isotopic compositions of revealed that both mixing of diffuse sources and biogeochemical attenuation controlled the fate of in the streams of the Western Port catchments. During the wet periods, inorganic fertiliser appeared to be the primary source of to the streams while SOM, in addition to inorganic fertiliser was also a dominant source of during the dry periods. Denitrification in the catchment appeared to be the more active removal process during the wet periods in contrast to a greater importance of in-stream assimilation during the dry periods. However, these removal processes were insufficient to remove the agricultural-derived inferring that the streams were unreactive conduits of which might pose a potential enrichment threat to downstream ecosystems. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Australia and also one of the very few targeted studies in the Southern Hemisphere investigating the origin and sink of on a catchment scale using both δ15N and δ18O of . The application of isotopes in a region with highly variable and unpredictable rainfall patterns such as the Western Port catchments, although challenging, is imperative particularly in setting guidelines for sustainable land use management actions.

The data related to this article are available online at https://doi.org/10.4225/03/5b2c683663395.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-3953-2018-supplement.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We thank the associate editor and the reviewers for their constructive

comments. We also thank Douglas Russell, Dale Christensen and Tina Hines for

their help in the lab and in the field. We thank Neil Cranston for his help

in providing samples of cow manure. This work was supported by Melbourne

Water Corporation and an Australian Research Council Grant (LP130100684) to

PLMC.

Edited by: Manmohan

Sarin

Reviewed by: three anonymous referees

Barnes, R. T. and Raymond, P. A.: Land-use controls on sources and processing of nitrate in small watersheds: insights from dual isotopic analysis, Ecol. Appl., 20, 1961–1978, https://doi.org/10.1890/08-1328.1, 2010.

Bateman, A. S. and Kelly S. D.: Fertilizer nitrogen isotope signatures, Isot. Environ. Healt. S., 43, 237–247, https://doi.org/10.1080/10256010701550732, 2007.

Battaglin, W. A., Kendall, C., Chang, C. C. Y., Silva, S. R., and Campbell, D. H.: Chemical and isotopic evidence of nitrogen transformation in the Mississippi River, 1997–1998, Hydrol. Process., 15, 1285–1300, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.214, 2001.

Billy, C., Billen, G., Sebilo, M., Birgand, F., and Tournebize, J.: Nitrogen isotopic composition of leached nitrate and soil organic matter as an indicator of denitrification in a sloping drained agricultural plot and adjacent uncultivated riparian buffer strips, Soil Biol. Biochem., 42, 108–117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.09.026, 2010.

Buchwald, C. and Casciotti, K. L.: Oxygen isotopic fractionation and exchange during bacterial nitrite oxidation, Limnol. Oceanogr., 55, 1064–1074, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2010.55.3.1064, 2010.

Buchwald, C. and Casciotti, K. L.: Isotopic ratios of nitrite as tracers of the sources and age of oceanic nitrite, Nat. Geosci., 6, 308–313, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1745, 2013.

Buchwald, C., Santoro, A. E., McIlvin, M. R., and Casciotti, K. L.: Oxygen isotopic composition of nitrate and nitrite produced by nitrifying cocultures and natural marine assemblages, Limnol. Oceanogr., 58, 1361–1375, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2012.57.5.1361, 2012.

Burns, D. A., Boyer, E. W., Elliott, E. M., and Kendall, C.: Sources and transformations of nitrate from streams draining varying land uses: Evidence from dual isotope analysis, J. Environ. Qual., 38, 1149–59, https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2008.0371, 2009.

Carillo-Rivera, J. J.: Hydrogeology of Western Port, Geological Survey of Victoria, 1975.

Carmargo, J. A. and Alonso, A.: Ecological and toxicological effects of inorganic nitrogen pollution in aquatic ecosystems: A global assessment, Environ. Int., 32, 831–849, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2006.05.002, 2006.

Casciotti, K. L., Böhlke, J. K., McIlvin, M. R., Mroczkowski, S. J., and Hannon, J. E.: Oxygen isotopes in nitrite: Analysis, calibration, and equilibration, Anal. Chem., 79, 2427–2436, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac061598h, 2007.

Casciotti, K. L., McIlvin, M., and Buchwald, C.: Oxygen isotopic exchange and fractionation during bacterial ammonia oxidation, Limnol. Oceanogr., 55, 753–762, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2010.55.2.0753, 2010.

Chang, C. C. Y., Kendall, C., Silva, S. R., Battaglin, W. A., and Campbell, D. H.: Nitrate stable isotopes: Tools for determining nitrate sources among different land uses in the Mississippi River Basin, Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci., 59, 1874–1885, https://doi.org/10.1139/F02-153, 2002.

Chen, F., Jia, G., and Chen, J.: Nitrate sources and watershed denitrification inferred from nitrate dual isotopes in the Beijiang River, South China, Biogeochemistry, 94, 163–174, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-009-9316-x, 2009.

Chien, S. H., Shearer, G., and Kohl, D. H.: The nitrogen isotope effect associated with nitrate and nitrite loss from waterlogged soils, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J., 41, 63–69, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1977.03615995004100010021x, 1977.

Danielescu, S. and MacQuarrie, K. T. B.: Nitrogen and oxygen isotopes in nitrate in the groundwater and surface water discharge from two rural catchments: implications for nitrogen loading to coastal waters, Biogeochemistry, 115, 111–127, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-012-9823-z, 2013.

Deutsch, B., Voss, M., and Fischer, H.: Nitrogen transformation processes in the Elbe River: Distinguishing between assimilation and denitrification by means of stable isotope ratios in nitrate, Aquat. Sci., 71, 228–237, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-009-9147-9, 2009.

Elliott, E. M., Kendall, C., Wankel, S. D., Burns, D. A., Boyer, E. W., Harlin, K., Bain, D. J., and Butler, T. J.: Nitrogen isotopes as indicators of NOx source contributions to atmospheric nitrate deposition across the midwestern and northeastern United States, Environ. Sci. Technol, 41, 7661–7667, https://doi.org/10.1021/es070898t, 2007.

Enanga, E. M., Creed, I. F., Casson, N. J., and Beall, F. D.: Summer storms trigger soil N2O efflux episodes in forested catchments, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 121, 95–108, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JG003027, 2016.

Fry, B.: Stable isotope ecology, Springer, New York, 2006.

Galloway, J. N., Dentener, F. J., Capone, D. G., Boyer, E. W., Howarth, R. W., Seitzinger, S. P., Asner, G. P., Cleveland, C. C., Green, P. A., Holland, E. A., Karl, D. M., Michaels, A. F., Porter, J. H., Townsend, A. R., and Vörösmarty, C. J.: Nitrogen cycles: past, present, and future, Biogeochemistry, 70, 153–226, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-004-0370-0, 2004.

Granger, J. and Wankel, S. D.: Isotopic overprinting of nitrification on denitrification as a ubiquitous and unifying feature of environmental nitrogen cycling, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 6391–6400, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1601383113, 2016.

Harrington, R. R., Kennedy, B. P., Chamberlain, C. P., Blum, J. D., and Folt, C. L.: 15N enrichment in agricultural catchments: field patterns and applications to tracking Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), Chem. Geol., 147, 281–294, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2541(98)00018-7, 1998.

Hübner, H.: Isotope effects of nitrogen in the soil and biosphere, in: Handbook of Environmental Isotope Geochemistry, edited by: Fritz, P. and Fontes, J. C., The Terrestrial Environment, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 361–425, 1986.

Kaste, Ø., Bechmann, M., and Mørkved, P. T.: Tracing sources of nitrate in agricultural catchments by natural stable isotopes, Norwegian Institute for Water Research, Norway, 2006.

Kaushal, S. S., Groffman, P. M., Band, L. E., Elliott, E. M., Shields, C. A., and Kendall, C.: Tracking nonpoint source nitrogen pollution in human-impacted watersheds, Environ. Sci. Technol., 45, 8225–8232, https://doi.org/10.1021/es200779e, 2011.

Kendall, C. and Caldwell, E. A.: Fundamentals of isotope geochemistry, in: Isotope tracers in catchment hydrology, edited by: Kendall, C. and McDonnell, J. J., Elsevier, Amsterdam, 51–86, 1998.

Kendall, C., Elliott, E. M., and Wankel, S. D.: Tracing anthropogenic inputs of nitrogen to ecosystems, in: Stable isotopes in ecology and environmental science, edited by: Michener, R. H. and Lajtha, K., Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Boston, 375–449, 2007.

Mayer, B., Boyer, E. W., Goodale, C., Jaworski, N. A., Van Breemen, N., Howarth, R. W., Seitzinger, S., Billen, G., Lajtha, K., Nadelhoffer, K., Van Dam, D., Hetling, L. J., Nosal, M., and Paustian, K.: Sources of nitrate in rivers draining sixteen watersheds in the northeastern U.S.: Isotopic constraints, Biogeochemistry, 57–58, 171–197, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015744002496, 2002.

McIlvin, M. R. and Altabet, M. A.: Chemical conversion of nitrate and nitrite to nitrous oxide for nitrogen and oxygen isotopic analysis in freshwater and seawater, Anal. Chem., 77, 5589–5595, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac050528s, 2005.

Mueller, C., Zink, M., Samaniego, L., Krieg, R., Merz, R., Rode, M., and Knöller, K.: Discharge driven nitrogen dynamics in a mesoscale river basin as constrained by stable isotope patterns, Environ. Sci. Technol., 17, 9187–9196, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b01057, 2016.

Murdiyarso, D., Hergoualc'h, K., and Verchot, L. V.: Opportunities for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in tropical peatlands, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 19655–19660, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0911966107, 2010.

Ohte, N.: Tracing sources and pathways of dissolved nitrate in forest and river ecosystems using high-resolution isotopic techniques: a review, Ecol. Res., 28, 749–757, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-012-0939-3, 2013.

Panno, S. V., Kelly, W. R., Hackley, K. C., Hwang, H. H., and Martinsek, A. T.: Sources and fate of nitrate in the Illinois River Basin, Illinois, J. Hydrol., 359, 174–188, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2008.06.027, 2008.

Pardo, L. H., Kendall, C., Pett-Ridge, J., and Chang, C. C. Y.: Evaluating the source of streamwater nitrate using δ15N and δ18O in nitrate in two watersheds in New Hampshire, USA, Hydrol. Process., 18, 2699–2712, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.5576, 2004.

Peterson, B. J., Wollheim, W. M., Mulholland, P. J., Webster, J. R., Meyer, J. L., Tank, J. L., Marti, E., Bowden, W. B., Valett, H. M., Hershey, A. E., McDowell, M. H., Dodds, W. K., Hamilton, S. K., Gregory, S., and Morrall, D. D.: Control of nitrogen export from watersheds by headwater streams, Science, 292, 86–90, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1056874, 2001.

Riha, K. M., Michalski, G., Gallo, E. L., Lohse, K. A., Brooks, P. D., and Meixner, T.: High atmospheric nitrate input and nitrogen turnover in semi-arid urban catchments, Ecosystems, 17, 1309–1325, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-014-9797-x, 2014.

Sebilo, M., Billen, G., Grably, M., and Mariotti, A.: Isotopic composition of nitrate-nitrogen as a marker of riparian and benthic denitrification at the scale of the whole Seine River system, Biogeochemistry, 63, 35–51, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023362923881, 2003.

Sigman, D. M., DiFiore, P. J., Hain, M. P., Deutsch, C., Wang, Y., Karl, D. M., Knapp, A. N., Lehmann, M. F., and Pantoja, F.: The dual isotopes of deep nitrate as a constraint on the cycle and budget of oceanic fixed nitrogen, Deep Sea Res. Pt. I, 56, 1419–1439, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2009.04.007, 2009.

Snider, D. M., Spoelstra, J., Schiff, S. L., and Venkiteswaran, J. J.: Stable oxygen isotope ratios of nitrate produced from nitrification: (18)O-labeled water incubations of agricultural and temperate forest soils, Environ. Sci. Technol., 44, 5358–5364, https://doi.org/10.1021/es1002567, 2010.

Stein, J. L., Hutchinson, M. F., and Stein, J. A.: A new stream and nested catchment framework for Australia, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 18, 1917–1933, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-18-1917-2014, 2014.

Vitousek, P. M., Aber, J., Howarth, R. W., Likens, G. E., Matson, P. A., Schindler, D. W., Schlesinger, W. H., and Tilman, G. D.: Human alteration of the global nitrogen cycle: Causes and consequences, Ecol. Appl., 7, 737–750, https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(1997)007[0737:HAOTGN]2.0.CO;2, 1997.

Voss, M., Deutsch, B., Elmgren, R., Humborg, C., Kuuppo, P., Pastuszak, M., Rolff, C., and Schulte, U.: Source identification of nitrate by means of isotopic tracers in the Baltic Sea catchments, Biogeosciences, 3, 663–676, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-3-663-2006, 2006.

Xue, D., Botte, J., De Baets, B., Accoe, F., Nestler, A., Taylor, P., Van Cleemput, O., Berglund, M., and Boeckx, P.: Present limitations and future prospects of stable isotope methods for nitrate source identification in surface- and groundwater, Water Res., 43, 1159–1170, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2008.12.048, 2009.

Yevenes, M. A., Soetaert, K., and Mannaerts, C. M.: Tracing nitrate-nitrogen sources and modifications in a stream impacted by various land uses, south Portugal, Water, 8, 385, https://doi.org/10.3390/w8090385, 2016.