the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Strong correspondence between nitrogen isotope composition of foliage and chlorin across a rainfall gradient: implications for paleo-reconstruction of the nitrogen cycle

Sara K. E. Goulden

Naohiko Ohkouchi

Katherine H. Freeman

Yoshito Chikaraishi

Nanako O. Ogawa

Hisami Suga

Oliver Chadwick

Benjamin Z. Houlton

Nitrogen (N) availability influences patterns of terrestrial productivity and global carbon cycling, imparting strong but poorly resolved feedbacks on Earth's climate system. Central questions concern the timescale of N cycle response to elevated CO2 concentration in the atmosphere and whether availability of this limiting nutrient increases or decreases with climate change. Nitrogen isotopic composition of bulk plant leaves provides information on large-scale patterns of N availability in the modern environment. Here we examine the utility of chlorins, degradation products of chlorophyll, hypothesized to persist in soil subsequent to plant decay, as proxies for reconstructing past plant δ15N. Specifically, we test the hypothesis that δ15N of plant leaves (δ15Nleaf) is recorded in δ15N of pheophytin a (δ15Npheo) along the leaf–litter–soil continuum across an array of ecosystem climate conditions and plant functional types (C3, C4, legumes, and woody plants). The δ15N of live foliage and bulk soil display marked declines with increasing rainfall, consistent with past studies in Hawaii and patterns worldwide. We find measurable chlorin concentrations along soil–depth profiles at all sites, with pheophytin a present in amounts required for isotopic analysis (>10 nmol). δ15Npheo in leaves, litter, and soil track δ15Nleaf of plant leaves. We find potential for δ15Npheo records from soil to provide proxy information on δ15Nleaf.

- Article

(1598 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

A combination of high biological requirements, limited natural supply, and high chemical reactivity and mobility gives nitrogen (N) important controls over photosynthesis and respiration in the terrestrial biosphere (Vitousek and Howarth, 1991). The response of the terrestrial carbon (C) cycle to climate change and increased atmospheric carbon dioxide (pCO2) will depend largely on the availability of N (Hungate et al., 2003; Wang and Houlton, 2009; Ainsworth and Long, 2005; Denman et al., 2007; Thornton et al., 2009), raising the question of how N availability may also be expected to change.

Humans have modified the N cycle directly through production of reactive N (Galloway et al., 1995) and likely indirectly through several climate-induced changes receiving ongoing investigation, including changes in biological demand (McLauchlan et al., 2013), changes in organic mineralization (Durán et al., 2016) and mineral weathering rates (Houlton et al., 2018), and changes in N-fixation rates. Experimental manipulations have yielded tremendous insights into mechanisms underlying complex carbon–climate–N cycle dynamics, yet limitations of geography, complexity, and time have left open questions about the overall N biogeochemical response to climate change at the landscape and global scales.

Insight into actual outcomes on real landscapes over decadal to millennial timescales would be helpful to predict how feedbacks between C and N cycles will play a role in climate change this century (Luo et al., 2004). If we could observe how N availability to plants responded to past periods of change in climate and pCO2, such as during transitions from glacial to interglacial periods, we could improve our projections for future integrative responses of the N cycles to a complex, changing world (Hungate et al., 2003; Houlton et al., 2015). Knowledge of past N cycle behavior would provide both insight into long-term dynamics and important baselines from which we can better assess anthropogenic impacts.

Natural abundance stable isotopes of N (δ15N) are useful integrators of N cycle processes in modern environmental systems (Robinson, 2001), and are natural sources of evidence for N cycle behavior in the past. Due to high reactivity and mobility of N, point-based concentration measurements give temporally limited views of dynamic plant–soil–microbial cycling of N. δ15N of plants and soils reflect a time-integrated signal of the N cycle. The gaseous loss processes (denitrification, ammonia volatilization, and anammox) which fractionate the light and heavy isotopes in terrestrial ecosystems are substrate-dependent, making δ15N sensitive to changes in the availability of nitrogen (Houlton and Bai, 2009). Conversely, at low N availability, there is likely to be less isotopic expression of these pathways as well as potential for greater dependence of plants on ectomycorrhizae, thereby reducing isotopic difference between plant foliage and N sources (Hobbie and Ouimette, 2009). As a result, higher δ15Nleaf corresponds to higher N availability to plants on average (e.g., Handley et al., 1999; Amundson et al., 2003; Houlton et al., 2007; Craine et al., 2009; Martinelli et al., 1999). Reconstructions of δ15Nleaf would accordingly provide information on availability of N to plants in the past.

The same reactivity of N that makes δ15Nleaf a valuable proxy for N availability in modern landscapes makes obtaining a primary N isotope signal from dead, buried, and decomposed organic matter particularly challenging. Primary δ15N signatures are altered by decomposition and diagenesis (Thackeray, 1998; Meyers and Ishiwatari, 1993; Hedges and Oades, 1997), and bulk interpretations are confounded by preferential preservation and accumulation of macromolecules with distinct δ15N values (Hobbie and Ouimette, 2009; Wedin et al., 1995). Because low-oxygen environments preserve organic matter, sediment accumulations in small lakes have been used as sources of terrestrial δ15Nleaf (McLauchlan et al., 2013). However, lake ecosystem processes can obscure the original δ15N of terrestrial sources (Meyers and Ishiwatari, 1993). Land-based paleo-proxy δ15Nleaf inferences have targeted bulk N protected structurally, in fossil faunal material (Stevens and Hedges, 2004), tree wood (Hietz et al., 2010), and pollen (Descolas-Gros and Scholzel, 2007). These approaches require controversial case-by-case defense of the primary nature of δ15N due to diagenetic vulnerability (Harbeck et al., 2004; Thackeray, 1998) and redistribution of N (Gerhart and McLauchlan, 2014). In the case of faunal material, it is also necessary to consider species-specific trophic enrichment factors, age effects, and dietary protein content (Sponheimer et al., 2003; Overman and Parrish, 2001). Many of these approaches are further limited for understanding landscape-level patterns by the poor spatial distribution of samples.

Compound-specific isotope analysis (CSIA) of sedimentary material offers advantages over these methods: isotope ratios of individual compounds can be more resistant to diagenesis than those of bulk materials, and have the further advantages of deriving from more constrainable sources. This last characteristic permits analysis of material from integrative depositional environments. In marine N biogeochemistry, subaqueous sediments that collect and bury organic compounds in time series deposits are widely used for paleoenvironmental reconstruction (Junium et al., 2011; Meyers, 1997). Soils likewise accumulate organic material over time, though not perfectly analogously to subaqueous systems.

The ideal characteristic compound for CSIA reconstruction of δ15Nleaf in soil is N-rich, produced only above-ground, and retains the primary δ15N of plant leaves. We suggest that degradation products of the chlorophyll molecule (chlorins) meet all the above criteria. Chlorins derive from chlorophyll through processes of senescence, decomposition, diagenesis, and grazing (Keely, 2006; Treibs, 1936). They have been successfully extracted from plants, litter, organic soil layers, sediments, and coal deposits (Kennicutt et al., 1992; Sanger, 1971a; Hodgson et al., 1968; Bidigare et al., 1991; Dilcher et al., 1970), but have not previously been sought in mineral soil horizons.

δ15N of chlorophyll and chlorins derived from algal pigments deposited in sediments have been used to infer N cycling processes in aquatic systems (Higgins et al., 2010; Sachs and Repeta, 1999; Enders et al., 2008; Tyler et al., 2010), as both combined chloropigment fractions and individual pigment compounds (Higgins et al., 2010; Kusch et al., 2010). Several studies have shown that the δ15N of plant chlorophyll reflects bulk foliar δ15N with a smaller offset than that between algal chlorophyll and bulk algal δ15N (Chikaraishi et al., 2005; Bidigare et al., 1991; Kennicutt et al., 1992), but δ15N has not previously been measured on chlorins extracted from decomposed plants, terrestrial organic matter, or soil. The behavior of chlorophyll a degradation products and their δ15N values along the leaf–soil continuum, and any environmental effects such as climate on isotope offsets, are also unknown.

Here we examine chlorin fractions for the presence of individual compounds in sufficient abundance for isotopic analysis. Pheophytin a (pheo a) is a chlorin previously found in greater relative abundance than any other in organic soils and litter (Sanger, 1971a; Gorham and Sanger, 1967), and is therefore of particular interest. We next examine δ15N of abundant chlorins in leaves, litter, and soil and compare values to bulk foliar sources to evaluate potential use of the compound as a proxy for past terrestrial foliar δ15N. For a chlorin to be a useful foliar δ15N proxy in the terrestrial environment, we hypothesize two conditions: first, it must persist in quantities sufficient for isotopic analysis. Second, it must record the δ15N value of the leaves it derived from. To meet this second condition, the chlorin δ15N must retain foliar δ15N with at most a constrainable isotopic offset, independent of environmental conditions and throughout the processes of biosynthesis, senescence, and decomposition.

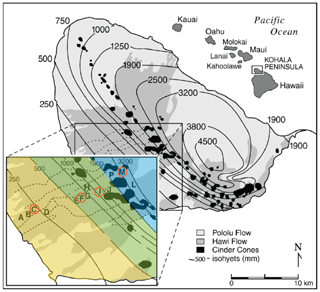

We evaluate these hypotheses on the natural climate gradient of the Kohala mountain, on the Big Island of Hawaii. These ecosystems are well suited for testing questions about relationships between climate, biogeochemistry, and the preservation or degradation of organic compounds. Relatively low plant diversity and broad environmental niches permit comparison of the bulk and compound-specific δ15N of leaves, litter, and soil of similar grassland communities at sites ranging widely in climate and δ15N to investigate patterns of deviation of compound-specific values from bulk values.

Figure 1Map of Kohala climosequence sites with respect to rainfall isoclines, reproduced from Chadwick et al. (2007). Sites sampled for this study (C, F, I, and M) are circled in orange. Vegetation zones are highlighted in the inset map: lowland dry scrubland and grassland between 150 and 500 mm of rainfall (yellow); lowland dry and mesic forest, woodland, and shrubland from 500 to 2000 mm (green); and wet forest and woodland above 2000 mm (blue).

2.1 Site description

The four sites of this study are located on Kohala mountain, the oldest of five volcanoes that make up the Big Island of Hawaii (Fig. 1). The sites are a subset of a well characterized climosequence running from the crest of Kohala down the leeward side (see Chadwick et al., 2003; Kelly et al., 1998b; Vitousek and Chadwick, 2013; von Sperber et al., 2017). Prevailing winds from the northwest create a dramatic gradient in precipitation, from 2500 mm falling annually at the uppermost site to 210 mm at the lowest site (Giambelluca et al., 1986). In contrast to the substantial shift in precipitation, the elevation of the mountain produces only a moderate gradient in air temperature, ranging from 17 ∘C at the upper site to 23 ∘C at the lowest site. Soils have been forming since emplacement of the Hawaii lava flows, approximately 150 000 years ago (Chadwick et al., 2003; Spengler and Garcia, 1988; Wolfe and Morris, 1996). This gradient thereby brings into focus precipitation as the most substantial systematic factor of change across sites.

Climate history for this region has been reconstructed from pollen assemblages in cores from bogs near the Kohala summit (Hotchkiss, 1998) and inferred from patterns of sea-level change (Ziegler et al., 2003), aeolian deposits (Porter, 1997), and soil calcite deposits at the drier sites (Chadwick et al., 2003; Porter, 1997). During glacial periods the summit was cooler and drier, while the lower sites show less climate variability, having remained arid throughout soil development.

Vegetation across the gradient was altered by clearing of land for pasture in the last 200 hundred years (Cuddihy and Stone, 1990; Chadwick et al., 2007), resulting in the introduction of non-native species and grasses with the C4 carboxylation pathway. All of the sites in this study experience grazing by cows, with sites F and I grazed most heavily. Site C is lowland dry scrubland and grassland (150 to 500 mm annual rainfall), dominated by buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaria) and the leguminous tree keawe (Prosopis pallida). Sites F (790 mm annual rainfall) and I (1260 mm annual rainfall) lie in lowland dry and mesic forest, woodland, and shrubland zones, which through conversion to pasture are dominated by the grass kikuyu (Pennisetum clandestinum). Site M lies in the wet forest and woodland zone (2500 mm annual rainfall), in which ohia (Metrosideros polymorpha) is the dominant tree, and the native understory was previously dominated by tree fern (Cibotium spp.) and uluhe (Dicranopteris linearis), but conversion of land to pasture has introduced kikuyu and other species. The herbs clover (Desmodium incanum) and Madagascar ragwort (Senecio madagascariensis) were additionally prevalent at sites I and M.

2.2 Sample collection and preparation

Leaves were sampled across sites from six plant species, from the upper one-third of the canopy in the case of the trees: Two grasses, P. clandestinum and C. ciliaria; two herbs, D. incanum and S. madagascariensis; and two trees, P. pallida and M. polymorpha. Two of these species are N fixers (D. incanum and P. pallida), and two have a C4 carboxylation pathway (P. clandestinum and C. ciliaria) while the others have C3. Each species was collected wherever present within a radius of ∼50 m from the soil pit dug at each site, but not all species were present at all sites. For grasses and herbs, at least three individuals were collected at each site and bulked for processing as a single sample. For trees, leaves were collected from at least three branches per tree and bulked for processing.

Soils were sampled from pits dug in open, grassy areas with minimal slope. Pits were dug to a depth of greater than 50 cm, with the deepest dug to 65 cm. At these sites, litter and organic horizon layers were sampled as a single genetic horizon termed “litter,” consisting of organic materials with fibrous through humic composition and which had a total thickness of less than 2 cm. Mineral horizons were sampled at regular depth intervals of ∼10 cm to a depth of 50 cm. Samples were bagged in Whirl-Pak bags and kept dark and chilled on ice in coolers until processing.

Live foliage was rinsed with deionized (DI) water to remove dust or other contaminants and then freeze-dried for preservation. Soils and litter were likewise freeze-dried. Dried samples were ground using either a carbide-steel shatter box (SPEX SamplePrep, University of California, Davis) or a mortar and pestle. Samples were stored in a dark freezer.

2.3 Compound extraction and purification

Samples were handled under very limited light conditions to minimize photodegradation. Pigments were extracted by sonication in triplicate using ∼100 mL of acetone (300 mL total) for 1 to 80 g of subsamples. Extracts were concentrated by evaporation to near dryness under nitrogen or argon. The condensed acetone extract was partitioned between 10 mL hexane and 30 mL Milli-Q water via liquid–liquid extraction to remove more polar compounds. The hexane fraction was retrieved, and dried under gentle flow of argon gas, and this crude chlorophyll extract was dissolved in dimethylformamide and passed through a syringe filter (0.4 µm) to remove particulates prior to high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) chromatography.

Two-dimensional HPLC was used to separate and purify chlorophyll a and b and their photo-reactive degradation products (Agilent 1200 series with a diode-array detector (DAD) and a fraction collector). Sample fractions corresponding to peaks collected from the first HPLC column run were subsequently run through a second column for additional purification of individual compounds. For the first HPLC separation step using reversed phase, the sample was passed through a Zorbax Eclipse XDB C18 column (9.4×250 mm; 5 µm) with a liquid phase consisting of acetonitrile∕pyridine (100:0.5) and ethyl acetate∕pyridine (100:0.5) in variable ratio, for 35 min at 4.2 mL min−1 and 30 ∘C, after Kusch et al. (2010). For the first 5 min of the run, acetonitrile∕pyridine was 75 % of the eluent, and this percentage was linearly reduced to 50 % over the subsequent 30 min of the run. For all samples, pheophytin a (pheo a) was collected upon elution at ∼19 min. For five plant samples, chlorophyll a and pyrochlorophyll a were collected upon elution at ∼12 min. Spectra were checked for purity across wavelengths 200–900 nm. In the second HPLC separation step, also using the reverse phase, the sample was passed through an Agilent Zorbax Eclipse PAH column (4.6×250 mm; 5 µm), with a liquid phase consisting of acetonitrile∕pyridine (100:0.5) and ethyl acetate∕pyridine (100:0.5) in a variable ratio for 35 min at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1 and 15 ∘C. For the first 5 min of the run, acetonitrile∕pyridine was 80 % of the eluent, between 5 and 30 min this percentage was linearly reduced from 80 % to 40 %, and for the last 5 min the column was flushed with 100 % ethyl acetate∕pyridine.

2.4 Analytical methods

Nitrogen isotopic composition, total N, and total C analysis of bulk soil (including litter) and leaf samples was performed using an elemental analyzer interfaced to a continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (EA–IRMS) at the University of California, Davis Stable Isotope Facility. The mean value of analytical precisions obtained for standard materials is 0.3 ‰ for δ15N. C∕N ratios are reported in mass units. In the case of soil, analysis was performed on ∼20 mg of material using an Elementar Vario EL Cube or MICRO Cube elemental analyzer (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Hanau, Germany) interfaced to a PDZ Europa 20-20 isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Sercon Ltd., Cheshire, UK). In the case of leaves, analysis was performed on ∼4 mg of material using a PDZ Europa ANCA-GSL elemental analyzer interfaced to a PDZ Europa 20-20 isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Sercon Ltd., Cheshire, UK). Samples are combusted at 1000 ∘C in a reactor packed with copper oxide and lead chromate. Following combustion, oxides were removed in a reduction reactor (reduced copper at 650 ∘C). The helium carrier then flowed through a water trap (magnesium perchlorate). N2 and CO2 were separated using a molecular sieve adsorption trap (for soil) or Carbosieve gas chromatography (GC) column (65 ∘C, 65 mL min−1) (for leaves) before entering the IRMS. Bulk isotopes of two plants (buffel and kikuyu samples from site F) were analyzed at the Japan Agency for Marine Earth-Science and Technology (JAMSTEC).

δ15N, total N, and total C analysis of isolated pheo a fraction was performed on a Nano EA–IRMS at JAMSTEC. This is a modification of an EA–IRMS system to achieve ultra-sensitive analysis (Ogawa et al., 2010). All samples contained at minimum 10 nmol N, resulting in δ15N precision of ‰. To investigate the possibility of N contamination, nitrogenous volatile was analyzed for the pheo a fraction using GC and a nitrogen–phosphorus detector (GC–NPD) with trimethylsilyl derivatization (BSTFA, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) at JAMSTEC. C∕N ratios from EA–IRMS were used as the “purity indicator” of each chlorophyll compound. As is described below, if a sample showed the clean spectrum pattern of a chlorin but had a significantly large C∕N ratio, it is likely that it contained C-containing contaminants, such as carbon hydrates, which are not detectable by DAD.

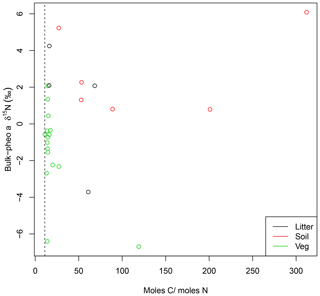

2.5 Purity of isolated compounds

While absorption spectra in UV–visible wavelengths showed no evidence for other absorptive components in the pheo a extracts, C∕N weight ratios greater than 11.8 revealed inclusion of non-pheo a carbon in the extracts. C∕N ratios were higher in pheo a extracted from litter (31) than plant samples (14.5), and even higher in pheo a samples from soils (113). Lack of relationship between C∕N and bulk-pheo δ15N offset suggests that impurities do not contribute significantly to measured δ15N values, however (Fig. 2). This supposition was confirmed by results from the GC–NPD, which showed a lack of nitrogenous compounds (e.g., containing amino groups) in the pheo a extracts. Although we caution that polar and less-volatile compounds cannot be detected by this method, the extraction methods make amino acids and other nitrogenous contaminants unlikely. The analytical protocol is designed to remove as many of such contaminating compounds as possible; e.g., amino acids are not soluble in acetone.

Figure 2C∕N ratios for pheo a isolates higher than 11 (dashed line) reveal contamination by carbon compounds. Effect of this contamination on pheo a δ15N is investigated by comparing pheo a molar C∕N with the offset between pheo a and bulk δ15N for litter (black), soil (red), and vegetation (green) samples. Lack of a systematic relationship between high C∕N ratios and greater similarity of pheo a δ15N to bulk values is evidence against contamination of the pheo a samples by N from the greater bulk sample.

2.6 Isotopic notation

Nitrogen isotopic compositions are reported using conventional delta (δ) notation:

where R represents the 15N∕14N ratio and subscripts indicate the sample or isotopic reference. The sample isotopic composition is measured directly relative to the N2 laboratory reference gas (δSRef), and the composition of the sample relative to the internationally recognized δ15N reference, AIR, is calculated by

Epsilon notation is used to describe biosynthetic isotopic fractionation within whole leaf (bulk) tissue. Nitrogen isotopic fractionation of pheo a relative to bulk leaf tissue (15εpheo−leaf) and chlorophyll a relative to bulk leaf tissue (15εchl−leaf) is defined according to Eq. (3):

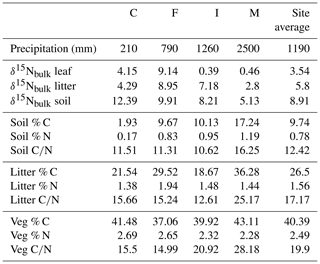

3.1 Bulk isotope and C and N concentration data

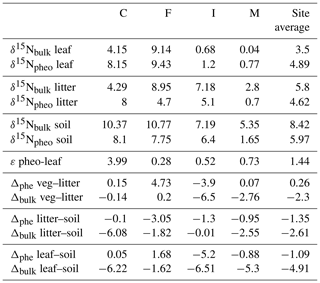

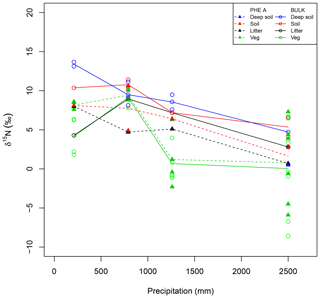

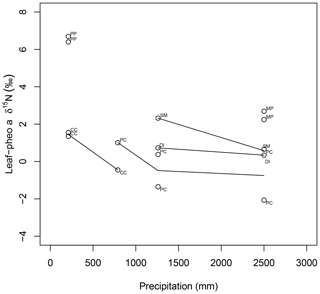

Site-averaged bulk δ15N of all soil samples decreased with increasing precipitation (and elevation) across all sites, from an average of 12.4 ‰ at site C to 5.1 ‰ at site M (Table 1). Site-averaged δ15N of litter decreased between sites C and M (4.3 ‰ to 2.8 ‰), but sites F and I were higher than either of these values (9.0 ‰ and 7.2 ‰). Average foliar δ15N likewise decreased between sites C and M (4.2 ‰ to 0.5 ‰), but site F (9.1 ‰) was higher than C (Fig. 3). Site-averaged bulk soil δ15N values for those samples on which δ15Npheo was measured follow similar trends (Table 2), though on average site values are slightly lower (8.4 ‰ vs. 8.9 ‰), reflecting the shallower average depth of the soil samples.

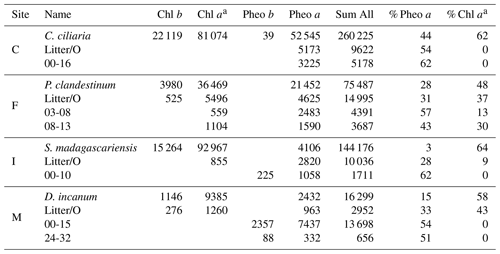

Table 2Relative compound abundance in a plant sample and the litter and soil horizons on which δ15Npheo was measured, grouped by site. Values reported are summed peak areas of absorbance at 660 nm in units of milli-absorbance units, summed for all collected injections of the sample. Values are first reported for individual compounds and then compared with the summed area of all detected chlorin peaks, first as absolute values and then as a percentage of chlorin peak area. Chlorophyll is abbreviated Chl.

a Chlorophyll a and pyrochlorophyll a are combined.

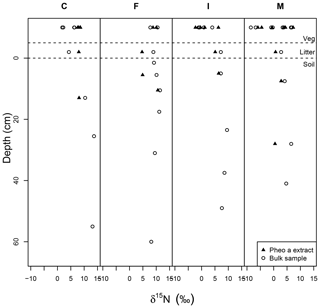

Figure 3Patterns in isotopes of bulk material (open circles) and pheo a extracts (closed triangles) from plant leaves (Veg, green), litter (black), and soil (red). Deep soils (blue) have a depth of greater than 30 cm and only one pheo a isotope measurement was made for these samples. Lines connect site averages between bulk (solid) and pheo a (dashed) measurements.

Soil % N increased from site C (0.2 %) to site M (1.2 %), and % C increased across these sites from 1.9 % to 17.2 %. C∕N increased between these sites from 11.5 to 16.3 (Table 1). Litter % C and C∕N was notably higher at site M (36.3 % and 25.2) than at the other sites, although litter % N was relatively flat across all sites. Vegetation % C was likewise highest at site M (43.1 %), though this value was less exceptional compared with vegetation at other sites.

Vegetation had the highest C∕N (average of 19.9), followed by litter (17.2) and soil (12.4). At sites C, F, and M, C∕N of litter is closer to that of vegetation than to soil, while at site I C∕N of litter is closer to that of soil than to vegetation.

3.2 Chlorin compound detection

Chlorins were detected in leaf, litter, and soil samples, including in soil mineral horizons up to a depth of 32 cm (Table 2). As chlorophyll a has greater absorbance at 660 nm than pheo a, direct proportionality between relative HPLC peak areas and relative compound abundance in the sample should not be assumed. In plant leaves, chlorophyll a was the dominant chlorin. Chlorophyll a was also found in smaller to trace amounts in litter and some soils. In litter, pheo a was the dominant pigment, with the exception of site M, where chlorophyll a was more abundant in the litter sample. In site C, chlorophyll a was absent from litter and soil. In soils, pheo a was the most abundant degradation product. Pheo a, targeted for isotopic analysis due to its superlative abundance, was present in sufficient concentration for isotopic analysis above ∼20 cm in soils at most sites.

3.3 Pheophytin a N isotope data of leaves, litter, and soil

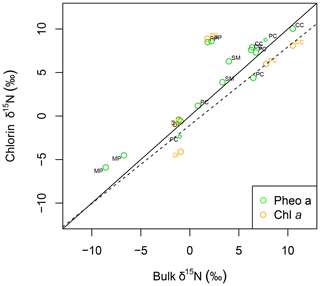

Intra-leaf isotope offsets. Across all plant samples, δ15Npheo of live foliage was significantly linearly correlated with bulk δ15Nleaf (slope=0.9; y intercept ; adjusted R2=0.8; p=0.000002507) (Fig. 4). 15εpheo−leaf was equal to 1.4 ‰ (±2.3 ‰) across all plant samples (Eq. 1).

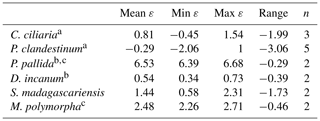

Table 3Average, minimum, maximum, and range of intra-leaf δ15N offsets between pheo a and bulk (15εpheo−leaf) for n measurements of each sampled species across all sites.

a C4 pathway. b N fixer. c Tree.

Figure 4δ15N of pheo a (green) and chlorophyll a (orange) correlates linearly with bulk leaf δ15N. The linear model for δ15N of pheo a as a function of bulk leaf δ15N is printed as a dashed line. A line with a slope of 1 (solid line) is plotted for reference. Each sample's species is identified with a label: CC: C. ciliaria (C4 pathway); DI: D. incanum (N fixer); MP: M. polymorpha (tree); PC: P. clandestinum (C4 pathway); PP: P. pallida (N fixer, tree); SM: S. madagascariensis.

Of the six sampled species, all but the two trees exhibited mean 15εpheo−leaf values ≤1.5 ‰ (Table 3): 15εpheo−leaf for P. pallida was 6.5 ‰ and 15εpheo−leaf for M. polymorpha was 2.5 ‰. If the P. pallida sample is omitted, 15εpheo−leaf drops to 0.71 ‰ (±1.3 ‰).

15εpheo−leaf was largest at site C (4.0 ‰) and smallest at site F (0.12 ‰). For a given species, average 15εpheo−leaf tended to either remain flat or slightly decrease into the wettest sites (Fig. 5).

Figure 5Comparison of species average intra-leaf δ15N offset between pheo a and bulk (15εpheo−leaf) across sites. CC: C. ciliaria (C4 pathway); DI: D. incanum (N fixer); MP: M. polymorpha (tree); PC: P. clandestinum (C4 pathway); PP: P. pallida (N fixer, tree); SM: S. madagascariensis.

δ15Npheo offsets across leaf–litter–soil. δ15N of pheo a in litter was on average 0.3 ‰ higher than the δ15N of pheo a of live foliage at a common site. Average differences between the δ15N of bulk litter and foliage were slightly higher, at ∼2.6 ‰ at a common site (Table 4). Pheo a-specific soil δ15N values were on average 1.3 ‰ higher than pheo a litter values at a common site; bulk δ15N soil values are 2.6 ‰ higher than bulk litter. The average offset between δ15Npheo of soil and live foliage at a site was 1.1 ‰; the average offset between bulk soil and bulk vegetation δ15N was 4.9 ‰.

3.4 Soil depth profiles

Soil δ15Nbulk was, on average, higher than the δ15Nbulk of overlying litter, and there was a slight trend of increasing δ15Nbulk with increasing depth in the upper ∼25 cm of soil pits (Fig. 6). δ15Npheo of soil also displayed higher values relative to overlying litter at sites F and I and in part of the profile at site M (Fig. 6). Soil δ15Nbulk values returned to slightly more negative values deep in the profiles; particularly notable at site F. At site C, δ15Npheo values along the soil profile do not deviate significantly from that of the overlying litter. At site M, δ15Npheo values increased slightly with depth in the upper profile, but then decreased while δ15Nbulk steadily increased with greater depth. In sum, δ15Npheo of soil did not follow δ15Nbulk, nor did it constantly track δ15Npheo of modern plants at a common site.

Figure 6Bulk samples (open circles) and pheo a-specific (closed triangles) δ15N in depth profiles across the rainfall gradient from dry (C) to wet (M) sites. Dashed lines set apart the vegetation samples (top) from litter samples (middle) and soil samples (bottom). The surface of the mineral soil is at a depth of 0.

4.1 Evaluation of δ15N fractionation within leaves

Nitrogen isotopic offsets between pheophytin a and live foliage (15εpheo−leaf) are generally small (mean of 1.4 ‰) and well constrained (SD±2.3 ‰, Fig. 3) across our sites, marking δ15Npheo as a useful proxy for bulk δ15Nleaf. The robustness of 15εpheo−leaf across the wide range in environmental variables and values of δ15Nleaf observed across these sites (Fig. 4) suggests that isotope effects from species or physiological changes will be relatively small sources of variation in δ15Npheo compared with changes to primary δ15Nleaf. For example, average community foliar δ15Nleaf varies by about ∼10 ‰ across terrestrial biomes in the modern environment (Craine et al., 2009), and paleo records have inferred comparable shifts in δ15Nleaf of 10 ‰ between glacial–interglacial cycles (Stevens et al., 2008). The possible effect of species shifts, and particularly growth of forests, should be considered when evaluating proxy δ15Npheo records, however. One species, P. pallida, has 15εpheo−leaf of 6.5 ‰. The other tree studied here, M. Polymorpha, had the next largest 15εpheo−leaf (2.5 ‰), while herbaceous plant values were all considerably smaller (−0.29 to 1.4 ‰), raising the possibility that this is a systematic isotope effect in trees, perhaps due to their greater size, longevity, and resulting N storage and redistribution requirements relative to herbaceous plants.

4.2 Evaluation of δ15Npheo from soil as a proxy for δ15Nleaf

Pheo a was present in quantities sufficient for isotopic analysis in litter and the uppermost mineral soil sample at all sites, and down to 30 cm at the wettest site (Fig. 4), inviting exploration of soil δ15Npheo as a proxy for δ15Nleaf. δ15Npheo of soil and litter matches δ15Npheo of overlying leaves at only one studied site (site C). Two alternatives could explain the lack of coherence in leaf, litter, and soil pools across most sites: (1) there is isotopic alteration during senescence and mineralization of chlorophyll, and (2) litter and soil pheo a pools have other sources than the plants we sampled, either on the current landscape or from previous vegetation covers.

To investigate the expression of fractionation on demetallation of chlorophyll in these samples, we can compare the δ15Npheo with chlorophyll a from the same sample. Chlorophyll a was only in sufficient abundance for isotopic measurement in live plant leaves. Chlorophyll a is about 0.05 ‰ depleted in 15N relative to bulk leaves in this study. This is consistent with previous studies, which found chlorophyll in plants to be 1.2 ‰ depleted in 15N relative to bulk leaf tissue (Kennicutt et al., 1992; Chikaraishi et al., 2005). Pheo a is accordingly about 2 ‰ enriched in 15N relative to chlorophyll a in our leaf samples, which could point to fractionation either within the leaf or in the laboratory (Sachs, 1997). Because chlorophyll abundance is greatly reduced between leaves and litter, any fractionation is likely to be expressed as a difference between leaves and litter, not as a difference between litter and soil or within soil. Fractionation on demetallation from chlorophyll should therefore not account for changes in δ15Npheo in the soil.

Soil is enriched in 15N relative to litter at our sites, consistent with observations from a wide range of environments, including temperate rainforest (Menge et al., 2011), temperate deciduous forests (Templer and Dawson, 2004), boreal forests (Hyodo and Wardle, 2009), tropical forests (Martinelli et al., 1999), temperate grasslands (Baisden et al., 2002; Brenner et al., 2001), and elsewhere (Hobbie and Ouimette, 2009). Because post-depositional processing of N involves the preferential loss of 14N from the soil N pool without replacement, through removal of the products of mineralization and denitrification, bulk soil δ15N is highly dynamic and will tend to increase along a decomposition gradient. In contrast, if there is no fractionation on breakdown of pheo a, δ15Npheo in soil should not depart from the δ15Npheo of litter inputs.

In soil profiles across the climosequence, δ15Nbulk and δ15Npheo do not exhibit similar depth patterns (Fig. 6). This suggests that different processes govern these two records in soil. While δ15Nbulk values become increasingly positive across the leaf–litter–soil continuum, pheo a values remain centered around site average leaf values, and sometimes show slight decreases in value from leaf to litter and soil (Table 4). This suggests that mixing of inputs may account for litter and soil pheo a δ15N values, while fractionating losses from the bulk soil N pool are required to explain δ15N bulk values.

δ15Npheo of litter is a window into possible isotopic effects of decomposition on δ15Npheo of plant leaves. The difference between δ15Npheo of leaves and litter averaged close to zero and was substantially smaller than the difference in δ15Nbulk (0.3 ‰ versus 2.3 ‰), supporting greater isotopic fidelity along the decay continuum in pheo a δ15N than bulk δ15N. Some of the site variability in isotopic offsets between litter and leaves/soil is likely due to differences in how well decomposed the collected litter was from site to site: at sites C, F, and M, C∕N of litter is closer to that of vegetation than to soil, while at site I C∕N of litter is closer to that of soil than to vegetation.

It is likely that litter samples do not reflect equal contributions from the plants sampled at the same site. Litter was collected from the surface of the soil pits, while vegetation was sampled from a radius of many meters, and plant taxa were not identified in litter samples to allow for source attribution. Soil algae and bacteria are considered insignificant contributors to soil pheo a, as the absorbance spectra of soil extracts showed that chlorophyll degradation products are dominated by higher plant contributions.

Pheophytin has two pathways of generation: like chlorophyll a, it is biosynthesized in plant leaves from glutamate where it serves as an electron acceptor in photosystem II (Klimov et al., 1977). Additionally, it is a product of chlorophyll degradation, whether via senescence, grazing, or decomposition across the leaf–soil continuum (Kräutler and Hörtensteiner, 2014; Sanger, 1971b), in which the central Mg is replaced by two H atoms. Transformation from chlorophyll to pheo a involves breaking N–Mg bonds, and so has potential for fractionation of N isotopes. However, the N–Mg bond is not a normal covalent bond, but a bond loosely connecting a ligand and metal in complex. Because the energy needed to break this bond is substantially smaller than the covalent bond, Mg loss from chlorophyll would theoretically be expected to have little or no N isotope fractionation. Senescence is unlikely to impart significant fractionation from bulk leaves given the observation that bulk leaf δ15N does not change on abscission (Kolb and Evans, 2002) and the understanding that N contained in the tetrapyrrole structure of chlorophyll is not recycled by the plant (Eckhardt et al., 2004). However, fractionation on demetallation of chlorophyll to pheo a has been observed in a laboratory setting with an effect of up to 2 ‰ (Sachs, 1997). Mineralization of pheo a is unlikely to alter δ15N of the remaining pheo a pool because known products of chlorin defunctionalization retain the four atoms of tetrapyrrole N and their associated bonds (Keely, 2006).

It is unlikely that environmental changes that took place between production of litter and growth of current leaves explain the observed differences between δ15N of plants and litter, given that litter at these sites is estimated to be no more than a few years old. Soil pools, however, could contain pheo a that is considerably older. There is reason to expect that deeper pheo a will be older than overlying pheo a in soil profiles and increasing recognition that compounds can be preserved in the soil matrix much longer than their inherent lability would predict (Mikutta et al., 2006; Torn et al., 1997; Marin-Spiotta et al., 2011; Kramer et al., 2012).

While we do not know the age of the sampled soil pheo a, radiocarbon dates of 4130 and 8030 yr BP were measured on soil organic carbon (SOC) deep within the soil profiles at sites A and D, respectively, along the climosequence (Chadwick et al., 2007), suggesting that our studied soils may reflect organic contributions from several thousands of years of soil development. Bulk soil carbon isotope values suggest that C4 pasture grasses, introduced over the last 200 hundred years, have been incorporated in the SOC in the top 40 cm of soil on these sites (Kelly et al., 1998a).

Patterns of radiocarbon (Δ14C) depletion of SOC in the profile (Baisden et al., 2002; Townsend et al., 1995; Tonneijck et al., 2006; Trumbore, 2009) indicate that SOC age increases with soil depth. Departures from this trend have been explained by the introduction of modern material by plant roots (Baisden et al., 2002), but as chlorophyll a and pheo a are photosynthetic pigments, we expect that inputs to the soil originate exclusively as litter accumulated at the soil surface, and we therefore expect for age of the chlorophyll derivatives to increase with depth. Bioturbation and episodic leaching could be disruptive of space-for-time trends, but based on the pattern observed in bulk SOC Δ14C they are unlikely to interfere with millennial-scale patterns given appropriate vertical sampling distances. In fact, in aggrading profiles, bioturbation has been shown to contribute to the increase in SOC age with depth, by transporting SOC downward over short distances and migrating upwards as soil accumulates overhead (Tonneijck and Jongmans, 2008).

If down-profile δ15Npheo values did represent prior landscape δ15Nleaf values, these data suggest greater changes to the N cycle at sites F and I than C and M, which could reflect heavier grazing at sites F and I. Climate has been more constant throughout the Holocene at lower elevations than higher elevations on Kohala (Hotchkiss, 1998), which could further account for the relatively constant δ15Npheo values at site C.

If the total soil δ15N pool reflects fractionation on loss of N, but the soil δ15Npheo pool does not, we expect that the more important gaseous losses are relative to leaching losses at a site, and thus the higher δ15Nbulk and the greater the offset between δ15Npheo and δ15Nbulk will be. Environments where denitrification is more important relative to leaching tend to be dry environments, due to much smaller isotope effects of non-gaseous losses (Houlton and Bai, 2009), and drier sites do indeed have higher δ15N in this study. Differences between δ15Npheo and δ15Nbulk do not show clear trends along the climosequence, however. This could be due to the complexity of soil moisture at these sites, reflected in the variability in down-profile soil bulk δ15N.

Direct testing of the hypothesis of increasing age with depth of pheo a would be enabled by improving the purification method of pheo a from soil. Removing contaminating C would make stable or radiocarbon isotopes of pheo a available tools to shed light on sources of pheo a in soil profiles, age of the compounds, and what resolution change in N cycling over the temporal window provided by the chlorins depth profile is observable (Ishikawa et al., 2015). These questions could also be averted by measuring δ15Npheo in soil profiles with constrained ages, such as buried horizons.

4.3 Implications of the δ15Npheo proxy

We suggest two key opportunities for application of a soil-based δ15Npheo proxy data to advance understanding of past terrestrial N dynamics. First, the ability to track changes in foliar δ15N over time implies comparatively direct insight into factors affecting δ15N of plants, notably the availability of nitrogen. Central questions concerning the timescale of N cycle responses to elevated CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, and whether availability of this limiting nutrient increases or decreases with climate change could be explored by selecting a time series that covers changes in atmospheric pCO2 (Goulden, 2016).

Second, comparison of compound-specific δ15Npheo with other δ15N proxies over the same time domain could provide insights into processes that cause them to deviate from one another. Alternative sources of δ15N proxies include subaqueous sediment deposits in lakes, ungulate tooth enamel, and bulk wood, black carbon, or soil. Deviations in records of δ15N of pheo and tooth enamel at a common site would highlight changes in factors affecting dietary isotope fractionations, such as animal growth rates. δ15Npheo records could provide information on terrestrial sources of δ15N relevant to aquatic sediment δ15N records and allow aquatic and terrestrial signals to be distinguished. δ15Npheo could validate bulk proxy records, or highlight diagenetic limitations of the record. Within soil horizons, comparing δ15Npheo with δ15Nbulk could provide information on both N availability to plants and dominant pathways of N loss, hydrologic or gaseous, at a site, allowing for comparison of multiple N cycle dynamics over time.

δ15Npheo in leaves provides a molecular recorder of foliar δ15N and provides a means to trace leaf nitrogen signatures in litter and soils. The compound is found in litter and upper soil horizons in an abundance sufficient for isotopic analysis, where it shows greater fidelity to leaf δ15N than does bulk material. δ15Npheo of soil may reveal temporal changes in nitrogen cycle behavior – e.g., the availability of nitrogen to plants, and whether nitrogen losses from the ecosystem had a dominant atmospheric or hydrologic fate. Due to the well-constrained photoautotrophic sources of chlorins, their lack of confounding heterotrophic enrichment, and their minimum N isotope fractionation during burial processes, CSIA of chlorins offers several advantages over bulk isotope analysis on the study of soil C and N cycles. δ15Npheo of soil is a most promising proxy for δ15Nleaf where organic matter inputs are high and profiles aggrade. The potential to investigate decadal- to millennial-scale N cycle dynamics will depend largely on conditions for preservation of soil organic matter.

The data can be accessed by email request to the corresponding authors and have been submitted to the open-access database PANGAEA (data submission 1 August 2019, https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.905053; Goulden et al., 2019).

SKEG and BZH acquired funding for the project. SKEG, BZH, and OC collected samples. NO, KHF, and BZH contributed laboratory space and materials. SKEG, NOO, HS, and YC conducted analyses of samples. SG performed data analysis, generated figures, and wrote the initial draft; BZH, NO, KHF, YC, NOO, HS, and OC contributed to the paper.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We are grateful for help with sample collection received from the 2012 Hawaii Ecosystems meeting field campaign and Peter Vitousek. We are indebted to the following people for useful discussions, help with methods development, and support of project logistics: Stephie Kusch, Meytal Higgins, Kendra McLauchlan, Joe Craine, Troy Baisden, Yudzuru Inouye, Rota Wagai, Yoshinori Takano, Naoto Ishikawa, Dirk Holstege, Scott Morford, Alison Marklein, Joy Winbourne, Jens Stevens, Angie Mungia, Elizabeth Denis, Laurence Bird, and Sanjai Parikh. The 2010 “Isocamp” summer short course provided a forum for seminal discussions of this project. We thank the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful feedback on the manuscript.

This research has been supported by the National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant (grant no. 1311365), the National Science Foundation East Asia & Pacific Summer Internship Program (grant no. 10246132), the National Science Foundation Inter-University Training for Continental Ecology Award (grant no. 1137336), the United States Environmental Protection Agency Science to Achieve Results (STAR) Fellowship (grant no. FP917327), and the National Science Foundation CAREER Award granted to Benjamin Z. Houlton (grant no. 1150246). Naohiko Ohkouchi and Nanako O. Ogawa were financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Fellowship (JSPS) (grant nos. 22244071 and 25281013).

This paper was edited by Marcel van der Meer and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ainsworth, E. A. and Long, S. P.: What have we learned from 15 years of free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE)? A meta-analytic review of the responses of photosynthesis, canopy, New Phytologist, 165, 351–371, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01224.x, 2005.

Amundson, R., Austin, A. T., Schuur, E. A. G., Yoo, K., Matzek, V., Kendall, C., Uebersax, A., Brenner, D., and Baisden, W. T.: Global patterns of the isotopic composition of soil and plant nitrogen, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 17, 1, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002gb001903, 2003.

Baisden, W. T., Amundson, R., Brenner, D. L., Cook, A. C., Kendall, C., and Harden, J. W.: A multiisotope C and N modeling analysis of soil organic matter turnover and transport as a function of soil depth in a California annual grassland soil chronosequence, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 16, 1135, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001gb001823, 2002.

Bidigare, R. R., Kennicutt, M. C., Keeneykennicutt, W. L., and Macko, S. A.: Isolation and purification of chlorophyll-a and chlorophyll-b for the determination of stable carbon and nitrogen isotope compositions, Analyt. Chem., 63, 130–133, 1991.

Brenner, D. L., Amundson, R., Baisden, W. T., Kendall, C., and Harden, J.: Soil N and 15N variation with time in a California annual grassland ecosystem, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 65, 4171–4186, 2001.

Chadwick, O. A., Gavenda, R. T., Kelly, E. F., Ziegler, K., Olson, C. G., Elliott, W. C., and Hendricks, D. M.: The impact of climate on the biogeochemical functioning of volcanic soils, Chem. Geol., 202, 195–223, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2002.09.001, 2003.

Chadwick, O. A., Kelly, E. F., Hotchkiss, S. C., and Vitousek, P. M.: Precontact vegetation and soil nutrient status in the shadow of Kohala Volcano, Hawaii, Geomorphology, 89, 70–83, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2006.07.023, 2007.

Chikaraishi, Y., Matsumoto, K., Ogawa, N. O., Suga, H., Kitazato, H., and Ohkouchi, N.: Hydrogen, carbon and nitrogen isotopic fractionations during chlorophyll biosynthesis in C3 higher plants, Phytochemistry, 66, 911–920, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.03.004, 2005.

Craine, J. M., Elmore, A. J., Aidar, M. P. M., Bustamante, M., Dawson, T. E., Hobbie, E. A., Kahmen, A., Mack, M. C., McLauchlan, K. K., Michelsen, A., Nardoto, G. B., Pardo, L. H., Penuelas, J., Reich, P. B., Schuur, E. A. G., Stock, W. D., Templer, P. H., Virginia, R. A., Welker, J. M., and Wright, I. J.: Global patterns of foliar nitrogen isotopes and their relationships with climate, mycorrhizal fungi, foliar nutrient concentrations, and nitrogen availability, New Phytologist, 183, 980–992, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02917.x, 2009.

Cuddihy, L. W. and Stone, C. P.: Alteration of native hawaiian vegetation effects of humans their activities and introductions, in: Alteration of Native Hawaiian Vegetation: Effects of Humans, Their Activities and Introductions, edited by: Cuddihy, L. W. and Stone, C. P., Xii + 138 p., University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, Illus. Maps. Paper, XII +,138P-XII + 138 pp., 1990.

Denman, K. L., Brasseur, G., Chidthaisong, A., Ciais, P., Cox, P. M., Dickinson, R. E., Hauglustaine, D., Heinze, C., Holland, E., Jacob, D., Lohmann, U., Ramachandran, S., da Silva Dias, P. L., Wofsy, S. C., and Zhang, X.: Couplings Between Changes in the Climate System and Biogeochemistry, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2007.

Descolas-Gros, C. and Scholzel, C.: Stable isotope ratios of carbon and nitrogen in pollen grains in order to characterize plant functional groups and photosynthetic pathway types, New Phytologist, 176, 390–401, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02176.x, 2007.

Dilcher, D. L., Pavlick, R. J., and Mitchell, J.: Chlorophyll derivatives in middle eocene sediments, Science, 168, 1447, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.168.3938.1447, 1970.

Durán, J., Morse, J. L., Groffman, P. M., Campbell, J. L., Christenson, L. M., Driscoll, C. T., Fahey, T. J., Fisk, M. C., Likens, G. E., Melillo, J. M., Mitchell, M. J., Templer, P. H., and Vadeboncoeur, M. A.: Climate change decreases nitrogen pools and mineralization rates in northern hardwood forests, Ecosphere, 7, e01251, https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1251, 2016.

Eckhardt, U., Grimm, B., and Hortensteiner, S.: Recent advances in chlorophyll biosynthesis and breakdown in higher plants, Plant Molecular Biology, 56, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-004-2331-3, 2004.

Enders, S. K., Pagani, M., Pantoja, S., Baron, J. S., Wolfe, A. P., Pedentchouk, N., and Nunez, L.: Compound-specific stable isotopes of organic compounds from lake sediments track recent environmental changes in an alpine ecosystem, Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado, Limnol. Oceanogr., 53, 1468–1478, 2008.

Galloway, J. N., Schlesinger, W. H., Levy, H., Michaels, A., and Schnoor, J. L.: Nitrogen-fixation – anthropogenic enhancement – environmental response, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 9, 235–252, 1995.

Gerhart, L. M. and McLauchlan, K. K.: Reconstructing terrestrial nutrient cycling using stable nitrogen isotopes in wood, Biogeochemistry, 120, 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-014-9988-8, 2014.

Giambelluca, T. W., Nullet, M. A., and Schroeder, T. A.: Rainfall Atlas of Hawaii, Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources, Honolulu, Hawaii, 1986.

Gorham, E. and Sanger, J.: Plant pigments in woodland soils, Ecology, 48, 306, https://doi.org/10.2307/1933116, 1967.

Goulden, S. K. E.: Development and application of a new method to reconstruct terrestrial nitrogen cycling from isotopes of plant compounds in soil, PhD, Land, Air, & Water Resources, University of California, Davis, 2016.

Goulden, S. K. E., Ohkouchi, N., Freeman, K. H., Chikaraishi, Y., Ogawa, N. O., Suga, H., Chadwick, O., and Houlton, B. Z.: Foliar, soil, litter, and chlorin data on carbon, nitrogen, and isotopes from a Hawaiian climosequence, PANGAEA, https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.905053, 2019.

Handley, L. L., Azcon, R., Lozano, J. M. R., and Scrimgeour, C. M.: Plant delta N-15 associated with arbuscular mycorrhization, drought and nitrogen deficiency, Rapid Commun. Mass Sp., 13, 1320–1324, 1999.

Harbeck, M., Ritz-Timme, S., Schroeder, I., Oehmichen, M., and von Wurmb-Schwark, N.: Degradation of biomolecules: A comparative study on the diagenesis of DNA and proteins in human osseous tissue, Anthropologischer Anzeiger, 62, 387–396, 2004.

Hedges, J. I. and Oades, J. M.: Comparative organic geochemistries of soils and marine sediments, Org. Geochem., 27, 319–361, 1997.

Hietz, P., Dunisch, O., and Wanek, W.: Long-Term Trends in Nitrogen Isotope Composition and Nitrogen Concentration in Brazilian Rainforest Trees Suggest Changes in Nitrogen Cycle, Environ. Sci. Technol., 44, 1191–1196, https://doi.org/10.1021/es901383g, 2010.

Higgins, M. B., Robinson, R. S., Carter, S. J., and Pearson, A.: Evidence from chlorin nitrogen isotopes for alternating nutrient regimes in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 290, 102–107, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2009.12.009, 2010.

Hobbie, E. A. and Ouimette, A. P.: Controls of nitrogen isotope patterns in soil profiles, Biogeochemistry, 95, 355–371, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-009-9328-6, 2009.

Hodgson, G. W., Hitchon, B., Taguchi, K., Baker, B. L., and Peake, E.: Geochemistry of porphyrins, chlorins and polycyclic aromatics in soils, sediments and sedimentary rocks, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 32, 737–772, 1968.

Hotchkiss, S. C.: Quaternary vegetation and climate of Hawai'i, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota, 1998.

Houlton, B. Z. and Bai, E.: Imprint of denitrifying bacteria on the global terrestrial biosphere, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 21713–21716, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912111106, 2009.

Houlton, B. Z., Sigman, D. M., Schuur, E. A. G., and Hedin, L. O.: A climate-driven switch in plant nitrogen acquisition within tropical forest communities, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 8902–8906, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0609935104, 2007.

Houlton, B. Z., Marklein, A. R., and Bai, E.: Representation of nitrogen in climate change forecasts, Nat. Clim. Change, 5, 398, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2538, 2015.

Houlton, B. Z., Morford, S. L., and Dahlgren, R. A.: Convergent evidence for widespread rock nitrogen sources in Earth's surface environment, Science, 360, 58–62, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan4399, 2018.

Hungate, B. A., Dukes, J. S., Shaw, M. R., Luo, Y. Q., and Field, C. B.: Nitrogen and climate change, Science, 302, 1512–1513, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1091390, 2003.

Hyodo, F. and Wardle, D. A.: Effect of ecosystem retrogression on stable nitrogen and carbon isotopes of plants, soils and consumer organisms in boreal forest islands, Rapid Commun. Mass Sp., 23, 1892–1898, https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.4095, 2009.

Ishikawa, N. F., Yamane, M., Suga, H., Ogawa, N. O., Yokoyama, Y., and Ohkouchi, N.: Chlorophyll a-specific Δ14C, δ13C and δ15N values in stream periphyton: implications for aquatic food web studies, Biogeosciences, 12, 6781–6789, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-12-6781-2015, 2015.

Junium, C. K., Keely, B. J., Freeman, K. H., and Arthur, M. A.: Chlorins in mid-Cretaceous black shales of the Demerara Rise: The oldest known occurrence, Org. Geochem., 42, 856–859, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2011.04.002, 2011.

Keely, B. J.: Geochemistry of chlorophylls, in: Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration, edited by: Grimm, B., Porra, R., Rudiger, W., and Scheer, H., Springer, ISBN 978-90-481-7140-8, 535–561 pp., 2006.

Kelly, E. F., Blecker, S. W., Yonker, C. M., Olson, C. G., Wohl, E. E., and Todd, L. C.: Stable isotope composition of soil organic matter and phytoliths as paleoenvironmental indicators, Geoderma, 82, 59–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-7061(97)00097-9, 1998a.

Kelly, E. F., Chadwick, O. A., and Hilinski, T. E.: The effect of plants on mineral weathering, Biogeochemistry, 42, 21–53, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1005919306687, 1998b.

Kennicutt, M. C., Bidigare, R. R., Macko, S. A., and Keeneykennicutt, W. L.: The stable isotopic composition of photosynthetic pigments and related biochemicals, Chem. Geol., 101, 235–245, 1992.

Klimov, V., Klevanik, A., and Shuvalov, V.: Reduction of pheophytin in the primary light reaction of photosystem II, FEBS letters, 82, 183–186, 1977.

Kolb, K. J. and Evans, R. D.: Implications of leaf nitrogen recycling on the nitrogen isotope composition of deciduous plant tissues, New Phytologist, 156, 57–64, 2002.

Kramer, M. G., Sanderman, J., Chadwick, O. A., Chorover, J., and Vitousek, P. M.: Long-term carbon storage through retention of dissolved aromatic acids by reactive particles in soil, Global Change Biol., 18, 2594–2605, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02681.x, 2012.

Kräutler, B. and Hörtensteiner, S.: Chlorophyll breakdown: chemistry, biochemistry, and biology, in: Handbook of Porphyrin Science (Volume 28) With Applications to Chemistry, Physics, Materials Science, Engineering, Biology and Medicine – Volume 28: Chlorophyll, Photosynthesis and Bio-inspired Energy, World Scientific, 117–185, 2014.

Kusch, S., Kashiyama, Y., Ogawa, N. O., Altabet, M., Butzin, M., Friedrich, J., Ohkouchi, N., and Mollenhauer, G.: Implications for chloro- and pheopigment synthesis and preservation from combined compound-specific δ13C, δ15N, and Δ14C analysis, Biogeosciences, 7, 4105–4118, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-7-4105-2010, 2010.

Luo, Y., Su, B., Currie, W. S., Dukes, J. S., Finzi, A. C., Hartwig, U., Hungate, B., McMurtrie, R. E., Oren, R., Parton, W. J., Pataki, D. E., Shaw, M. R., Zak, D. R., and Field, C. B.: Progressive nitrogen limitation of ecosystem responses to rising atmospheric carbon dioxide, Bioscience, 54, 731–739, 2004.

Marin-Spiotta, E., Chadwick, O. A., Kramer, M., and Carbone, M. S.: Carbon delivery to deep mineral horizons in Hawaiian rain forest soils, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 116, G3, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JG001587, 2011.

Martinelli, L. A., Piccolo, M. C., Townsend, A. R., Vitousek, P. M., Cuevas, E., McDowell, W., Robertson, G. P., Santos, O. C., and Treseder, K.: Nitrogen stable isotopic composition of leaves and soil: Tropical versus temperate forests, Biogeochemistry, 46, 45–65, 1999.

McLauchlan, K. K., Williams, J. J., Craine, J. M., and Jeffers, E. S.: Changes in global nitrogen cycling during the Holocene epoch, Nature, 495, 352–355, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11916, 2013.

Menge, D. N. L., Baisden, W. T., Richardson, S. J., Peltzer, D. A., and Barbour, M. M.: Declining foliar and litter delta 15N diverge from soil, epiphyte and input delta 15N along a 120 000 yr temperate rainforest chronosequence, New Phytologist, 190, 941–952, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03640.x, 2011.

Meyers, P. A.: Organic geochemical proxies of paleoceanographic, paleolimnologic, and paleoclimatic processes, Org. Geochem., 27, 213–250, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0146-6380(97)00049-1, 1997.

Meyers, P. A. and Ishiwatari, R.: Lacustrine organic geochemistry - an overview of indicators of organic-matter sources and diagenesis in lake-sediments, Org. Geochem., 20, 867–900, https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6380(93)90100-p, 1993.

Mikutta, R., Kleber, M., Torn, M. S., and Jahn, R.: Stabilization of soil organic matter: Association with minerals or chemical recalcitrance?, Biogeochemistry, 77, 25–56, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-005-0712-6, 2006.

Ogawa, N. O., Nagata, T., Kitazato, H., and Ohkouchi, N.: Ultra-sensitive elemental analyzer/isotope ratio mass spectrometer for stable nitrogen and carbon isotope analysis, in: Earth, Life, and Isotopes, edited by: Ohkouchi, N., Tayasu, I., and Koba, K., Kyoto University Press, Japan, 339–353, 2010.

Overman, N. C. and Parrish, D. L.: Stable isotope composition of walleye: N-15 accumulation with age and area-specific differences in delta C-13, Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci., 58, 1253–1260, 2001.

Porter, S. C.: Late Pleistocene eolian sediments related to pyroclastic eruptions of Mauna Kea volcano, Hawaii, Quaternary Res., 47, 261–276, https://doi.org/10.1006/qres.1997.1892, 1997.

Robinson, D.: delta N-15 as an integrator of the nitrogen cycle, Trends Ecol. Evol., 16, 153–162, 2001.

Sachs, J. P.: Nitrogen isotopes in chlorophyll and the origin of Eastern Mediterranean sapropels, Massachusetts Institute of Technology/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1997.

Sachs, J. P. and Repeta, D. J.: Oligotrophy and nitrogen fixation during eastern Mediterranean sapropel events, Science, 286, 2485–2488, 1999.

Sanger, J. E.: Identification and Quantitative Measurement of Plant Pigments in Soil Humus Layers, Ecology, 52, 959–963, 1971a.

Sanger, J. E.: Quantitative investigations of leaf pigments from their inception in buds through autumn coloration to decomposition in falling leaves, Ecology, 52, 1075–1089, 1971b.

Spengler, S. R. and Garcia, M. O.: Geochemistry of the Hawi lavas, Kohala volcano, Hawaii, Contrib. Mineral. Petr., 99, 90–104, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00399369, 1988.

Sponheimer, M., Robinson, T., Ayliffe, L., Roeder, B., Hammer, J., Passey, B., West, A., Cerling, T., Dearing, D., and Ehleringer, J.: Nitrogen isotopes in mammalian herbivores: Hair delta N-15 values from a controlled feeding study, Int. J. Osteoarchaeol., 13, 80–87, https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.655, 2003.

Stevens, R. E. and Hedges, R. E. M.: Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis of northwest European horse bone and tooth collagen, 40,000 BP-present: Palaeoclimatic interpretations, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 23, 977–991, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2003.06.024, 2004.

Stevens, R. E., Jacobi, R., Street, M., Germonpre, M., Conard, N. J., Munzel, S. C., and Hedges, R. E. M.: Nitrogen isotope analyses of reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), 45,000 BP to 900 BP: Palaeoenvironmental reconstructions, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 262, 32–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.01.019, 2008.

Templer, P. H. and Dawson, T. E.: Nitrogen uptake by four tree species of the Catskill Mountains, New York: Implications for forest N dynamics, Plant Soil, 262, 251–261, https://doi.org/10.1023/b:plso.0000037047.16616.98, 2004.

Thackeray, F.: Late Quaternary palaeoclimates at Nelson Bay Cave, based on stable carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios from ungulate teeth: a re-assessment, S. Afr. J. Sci., 94, 442–443, 1998.

Thornton, P. E., Doney, S. C., Lindsay, K., Moore, J. K., Mahowald, N., Randerson, J. T., Fung, I., Lamarque, J.-F., Feddema, J. J., and Lee, Y.-H.: Carbon-nitrogen interactions regulate climate-carbon cycle feedbacks: results from an atmosphere-ocean general circulation model, Biogeosciences, 6, 2099–2120, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-6-2099-2009, 2009.

Tonneijck, F. H. and Jongmans, A. G.: The influence of bioturbation on the vertical distribution of soil organic matter in volcanic ash soils: a case study in northern Ecuador, Eur. J. Soil Sci., 59, 1063–1075, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2008.01061.x, 2008.

Tonneijck, F. H., van der Plicht, J., Jansen, B., Verstraten, J. M., and Hooghiemstra, H.: Radiocarbon dating of soil organic matter fractions in Andosols in northern Ecuador, Radiocarbon, 48, 337–353, 2006.

Torn, M. S., Trumbore, S. E., Chadwick, O. A., Vitousek, P. M., and Hendricks, D. M.: Mineral control of soil organic carbon storage and turnover, Nature, 389, 170–173, 1997.

Townsend, A. R., Vitousek, P. M., and Trumbore, S. E.: Soil organic-matter dynamics along gradients in temperature and land-use on the island of hawaii, Ecology, 76, 721–733, https://doi.org/10.2307/1939339, 1995.

Treibs, A.: Chlorophyll and heme derivatives in organic mineral materials, Angewandte Chemie, 49, 0682–0686, 1936.

Trumbore, S.: Radiocarbon and Soil Carbon Dynamics, in: Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Annual Reviews, Palo Alto, 47–66, 2009.

Tyler, J., Kashiyama, Y., Ohkouchi, N., Ogawa, N., Yokoyama, Y., Chikaraishi, Y., Staff, R. A., Ikehara, M., Ramsey, C. B., Bryant, C., Brock, F., Gotanda, K., Haraguchi, T., Yonenobu, H., and Nakagawa, T.: Tracking aquatic change using chlorine-specific carbon and nitrogen isotopes: The last glacial-interglacial transition at Lake Suigetsu, Japan, Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst., 11, Q09010, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010gc003186, 2010.

Vitousek, P. M. and Chadwick, O. A.: Pedogenic Thresholds and Soil Process Domains in Basalt-Derived Soils, Ecosystems, 16, 1379–1395, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-013-9690-z, 2013.

Vitousek, P. M. and Howarth, R. W.: Nitrogen limitation on land and in the sea – how can it occur, Biogeochemistry, 13, 87–115, 1991.

von Sperber, C., Chadwick, O. A., Casciotti, K. L., Peay, K. G., Francis, C. A., Kim, A. E., and Vitousek, P. M.: Controls of nitrogen cycling evaluated along a well-characterized climate gradient, Ecology, 98, 1117–1129, https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.1751, 2017.

Wang, Y. P. and Houlton, B. Z.: Nitrogen constraints on terrestrial carbon uptake: Implications for the global carbon-climate feedback, Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, 24, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009gl041009, 2009.

Wedin, D. A., Tieszen, L. L., Dewey, B., and Pastor, J.: Cabon-isotope dynamics during grass decomposition and soil organic-matter formation, Ecology, 76, 1383–1392, 1995.

Wolfe, E. W. and Morris, J.: Geologic Map of the Island of Hawaii, USGS Map I-2524-A, 1996.

Ziegler, K., Hsieh, J. C. C., Chadwick, O. A., Kelly, E. F., Hendricks, D. M., and Savin, S. M.: Halloysite as a kinetically controlled end product of arid-zone basalt weathering, Chem. Geol., 202, 461–478, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2002.06.001, 2003.