the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Metabolic tradeoffs and heterogeneity in microbial responses to temperature determine the fate of litter carbon in simulations of a warmer world

Seeta A. Sistla

Kristen M. DeAngelis

Climate change has the potential to destabilize the Earth's massive terrestrial carbon (C) stocks, but the degree to which models project this destabilization to occur depends on the kinds and complexities of microbial processes they simulate. Of particular note is carbon use efficiency (CUE), which determines the fraction of C processed by microbes that is anabolized into microbial biomass rather than lost to the atmosphere and soil as carbon dioxide and extracellular products. The temperature sensitivity of CUE is often modeled as an intrinsically fixed (homogeneous) property of the community, which contrasts with empirical data and has unknown impacts on projected changes to the soil C cycle under global warming. We used the Decomposition Model of Enzymatic Traits (DEMENT) – which simulates taxon-level litter decomposition dynamics – to explore the effects of introducing organism-level heterogeneity into the CUE response to temperature for decomposition of leaf litter under 5 ∘C of warming. We found that allowing the CUE temperature response to differ between taxa facilitated increased loss of litter C, unless fungal taxa were specifically restricted to decreasing CUE with temperature. Litter C loss was exacerbated by variable and elevated CUE at higher temperature, which effectively lowered costs for extracellular enzyme production. Together these results implicate a role for diversity of taxon-level CUE responses in driving the fate of litter C in a warmer world within DEMENT, which should be explored within the framework of additional model structures and validated with empirical studies.

- Article

(1763 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(225 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Soil heterotrophs are central to the cycling and recycling of the 60 Gt of organic carbon (C) that plants deposit onto and into the ground each year. How well these inputs are converted into relatively stable soil organic matter depends on temperature, moisture, chemical composition, and soil mineralogy, which interact to influence microbial physiology (Manzoni et al., 2012; Kallenbach et al., 2016; Oldfield et al., 2018). Predictions regarding how soil C stocks will respond to climate change are, in turn, highly sensitive to how carbon use efficiency (CUE) – or the fraction of C taken up by a cell and incorporated into biomass rather than being respired – changes with temperature (Allison et al., 2010; Wieder et al., 2013; Allison, 2014; Li et al., 2014; Sistla et al., 2014; Tang and Riley, 2015). As such, quantifying microbial decomposer CUE and its responsiveness to environmental change has been subject to intensive study (Devêvre and Horwáth, 2000; Frey et al., 2013; Blagodatskaya et al., 2014; Lee and Schmidt, 2014; Spohn et al., 2016a, b; Öquist et al., 2017; Malik et al., 2018; Geyer et al., 2019; Malik et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2019).

Soil microbial communities show considerable differences in how their metabolisms respond to elevated temperatures, with their CUE increasing (Öquist et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2019), decreasing (Devêvre and Horwáth, 2000; Frey et al., 2013; Öquist et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2019), or remaining unaffected by warming (Dijkstra et al., 2011b; Öquist et al., 2017; Walker et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2019). However, models of the soil C cycle generally assume either no change (Allison et al., 2010; Li et al., 2014; Wieder et al., 2014) or a fixed and homogeneous decrease in CUE with temperature (Allison et al., 2010; Wieder et al., 2013; Allison, 2014; Li et al., 2014). When CUE is allowed to directly increase with temperature, this temperature response is homogeneous across taxa (Frey et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2019). In other instances, CUE may be modeled as fixed within taxa, such that dynamic changes in community-level CUE with warming are the result of shifts in the dominant group or groups of organisms present as a function of their dietary preferences and/or C : N (nitrogen) ratio (Wieder et al., 2013; Sistla et al., 2014) rather than any inherent differences in the temperature sensitivity of the constituent community members. This may occur, for instance, if large C-rich fungi show less-positive responses to warming than small, N-rich bacteria do (Pietikäinen et al., 2005; DeAngelis et al., 2015). Therefore, models have thus far insufficiently accounted for how the temperature sensitivity of central metabolism may differ between microbes, such that intrinsic differences in efficiency between taxa (heterogeneity) above and beyond temperature-driven differences in substrate supply may also drive microbial community trajectories.

Heterogeneity in the temperature sensitivity of growth efficiency across taxa could be driven by differences in the rate-limiting step of central metabolic pathways (Dijkstra et al., 2011a) or in how well the proteins responsible for the extracellular processing and uptake of environmental nutrients are able to maintain activity as temperature increases (Allison et al., 2018; Alster et al., 2018). For instance, there is some evidence that bacteria benefit more than fungi from an increase in temperature, as their growth rate has been observed to decrease less rapidly with temperature above its optimum than a fungal community (Pietikäinen et al., 2005). The respiration rate for the two groups could not be isolated in that study, and so direct differential effects of temperature on CUE could not be parsed out. However, the CUE has been observed to differ in how sensitive it is to nutrient limitation for bacteria and fungi, such that differences in the temperature sensitivity of CUE between the two groups may play out as a consequence of changing nutrient demands (Keiblinger et al., 2010; Sinsabaugh et al., 2016). Therefore, the temperature range over which an organism can maintain efficient growth is one important dimension of its niche (Cavicchioli, 2016) and may differ between taxa.

The temperature response of CUE may also differ between taxa because of varying investments in extracellular enzyme production. Extracellular enzyme production can impose substantial metabolic costs on the cell (Allison, 2014; Malik et al., 2019), as C which could otherwise be allocated to growing the cell must instead be spent producing amino acids and ATP to synthesize the enzymes (Kaleta et al., 2013; Kafri et al., 2016). Thus if taxa need to produce more extracellular enzymes in order to support rapid growth at higher temperature, then their CUE could decrease with temperature. However, some taxa may have mechanisms to adjust central metabolism so growth remains efficient at elevated temperatures, as hinted by a weak positive correlation between the Q10 of CUE and cellulolytic potential in soil communities (Zheng et al., 2019). Nonetheless, the most probable relationship between the CUE temperature response and extracellular investment is currently unknown.

We explored whether interactions between the temperature sensitivity of intracellular (i.e., CUE) and extracellular (i.e., litter decomposing enzyme) metabolic processes of cells can explain why CUE is observed to increase with temperature in some soils and decrease in others. We used the litter decomposition model DEMENT (Decomposition Model of Enzymatic Traits; Allison, 2012) to evaluate four hypotheses: (1) allowing the temperature response of CUE to differ (be heterogeneous) between taxa increases uncertainty in projected litter decomposition dynamics because more diverse phenotypic combinations exist for competitive selection (i.e., species sorting) to act upon; (2) this heterogeneity favors a community with higher CUE, in turn leading to higher microbial biomass and greater litter C loss with warming; (3) forcing the temperature response of CUE to increase with the number of enzymes an organism produces causes greater litter C loss than when the two factors vary independently, because increasing CUE with temperature offsets the increased costs against CUE associated with copious enzyme production; and (4) the magnitude of litter C loss with warming is greater when the CUE of the C-rich fungal functional group increases with temperature than if only the N-rich bacterial functional group does due to the higher relative C demand of the former.

2.1 DEMENT background and model design

DEMENT (Allison, 2012) is a litter decomposition model designed to simulate the loss of leaf C through time. The principal advancement of DEMENT over its predecessors is that it is both microbially and spatially explicit. The model is able to simulate inter- and intraspecific microbial interactions, with a primary focus on the tradeoff between (i) the ability to take up and digest substrates and (ii) the metabolic costs of creating and maintaining the machinery required to do so. Because these tradeoffs are both explicit and variable across taxa, DEMENT is an ideal model for evaluating how the physiology and ecology of microbes affects C stocks in a changing world. Furthermore, DEMENT allows for consideration of how heterogeneous responses across taxa (rather than using some homogeneous cross-taxon mean) can facilitate soil C responses to climate change. Full details about the setup and execution of DEMENT are available elsewhere (Allison, 2012, 2014; Allison and Goulden, 2017); here we describe the controls on CUE in the model which are relevant to our study.

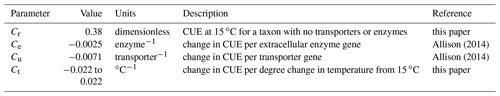

Intrinsic CUE – the maximum CUE an organism could attain under ideal temperature and stoichiometry – is calculated for each taxon as a function of the baseline CUE at 15 ∘C (Cr), as well as the number of enzymes (Ne) and uptake transporters (Nu) the taxon can produce. In turn, how much CUE is decreased due to enzyme and transporter production depends on the cost per enzyme (Ce) and cost per transporter (Cu) (Table 1). The C used in enzyme synthesis is considered a loss from the cell and is therefore not reported as microbial biomass C. The intrinsic CUE of each taxon is adjusted for temperature, decreasing by 0.016 ∘C−1 by default (i.e., ∘C−1), consistent with a global meta-analysis (Qiao et al., 2019). Therefore, CUE is calculated as , where temperature is in kelvin.

2.2 Modifications to DEMENT

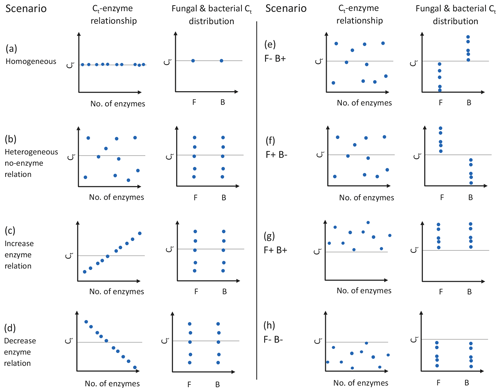

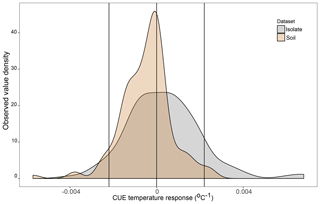

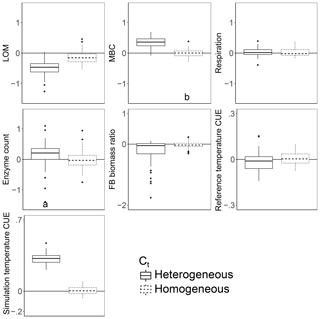

DEMENT version 0.7.2 was downloaded from GitHub (https://github.com/stevenallison/DEMENT, last access: 15 September 2016) and modified as follows. Cr was adjusted downwards from its original published value of 0.58 to 0.38 at 15 ∘C; this not only improved model stability (Table S1 in the Supplement), but is also consistent with a comparative modeling study completed by Li et al. (2014), with several 18O-H2O-based CUE measurements (Spohn et al., 2016a, b; Geyer et al., 2019), and for the structural components of litter modeled by the soil C model MIMICS (Wieder et al., 2015a). By default, the temperature sensitivity of CUE (Ct) is fixed to take on the same value (i.e., is homogeneous) for all taxa; therefore, we modified the model so Ct could vary around the mean in different ways (Fig. 1). In the first set of scenarios, Ct varied independent of the taxonomic identity or number of enzymes a taxon produced (Fig. 1b and hypotheses 1 and 2). In the second scenario, Ct was limited to either increasing (Fig. 1c) or decreasing (Fig. 1d) as a function of the number of enzymes a given taxon had (hypothesis 3). In the third, bacteria were constrained to have a positive and fungi a negative Ct (Fig. 1e), fungi a positive and bacteria a negative Ct (Fig. 1f), both bacteria and fungi a positive Ct (Fig. 1g), or both a negative Ct (Fig. 1h; hypothesis 4). In all instances, Ct was selected at random from a uniform distribution bounded by ±0.022 ∘C−1 at the upper and/or lower limits (scenarios b–h, Fig. 1) or assigned a fixed value equivalent to the cross-taxon mean (scenario a, Fig. 1; scenario ai and aii Fig. S1 in the Supplement). These values are within the range of temperature sensitivities observed for both bacterial cultures in the lab and for field communities (Fig. 2), as well as values inferred based on modeling CUE against mean annual temperature on a global basis (Sinsabaugh et al., 2017; Ye et al., 2019). It was necessary to force the temperature sensitivity of CUE to take on a zero-centered uniform distribution so that simulation outputs in which extracellular enzyme counts were linked to the Ct could be compared to those scenarios where they were not linked, without changing the distribution of extracellular enzyme counts present in the community.

2.3 Running DEMENT

DEMENT was run on the Massachusetts Green High Performance Computing Cluster for 6000 model days using 59 different independent starting seeds and a 100×100 grid size. Control runs were completed at 15 ∘C (equivalent to April to November mean soil temperature for a northern midlatitude temperate deciduous forest; Boose, 2001), while heated runs were completed at 20 ∘C (Allison, 2014). The first 1000 d of each resultant output file was excluded from the analysis because of rapid shifts in the microbial community during this time. In addition, outputs were filtered to exclude any seeds where the substrate pool was 2 or more times greater at the end of the model run than the median during the preceding 5000 d, indicating unrealistic, unconstrained litter accumulation. R version 3.4.0 was used for all runs and analyses (R Core Team, 2016). A full set of parameters and the model used to run all these simulations can be found in OSF.

2.4 Analysis of outputs

The model outputs of interest were litter organic matter (LOM), microbial biomass carbon (MBC), respiration rate, richness and diversity of the surviving community, median number of enzymes per taxon for taxa alive during the 5000 d simulation, fungal : bacterial biomass ratio for surviving taxa, and reference and simulation temperature CUE. Two diversity metrics – richness and Shannon's H – were calculated using median daily values for the microbial community over the 5000 d of simulation and the vegan package (Oksanen et al., 2017). Biomass-weighted CUE was reported for communities at 15 ∘C (reference temperature CUE) or at the simulation temperature (simulation temperature CUE), calculated using the formula

where 1000 and 6000 are the days of the simulation the outputs were examined over, 100 is the number of taxa the model was initiated with, Ne i is the number of enzyme genes taxon i has, Nu i is the number of uptake transporter genes the taxon has, and temperature is the simulation temperature in ∘K.

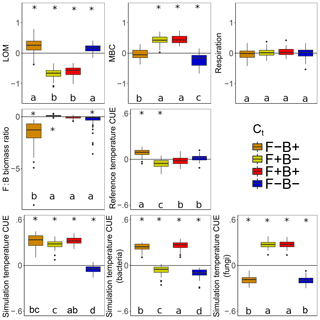

In order to determine whether warming and model parameterization affected model outputs, we used mixed effect models with the starting seed as a random effect and the warming or simulation scenario as fixed effects using lmer in lme4 version 1.1-17 (Bates et al., 2015). Data were visually assessed for normality and homoscedasticity using Q–Q plots and residual plots following log transformation. Significantly different pairwise differences were subsequently identified using emmeans version 1.3.0 (Lenth et al., 2019), with a stringent Bonferroni-corrected P-value cutoff of P<0.0001. Warming effect sizes are plotted as the natural log ratio of model outputs in heated : control scenarios. Figures were generated using ggplot2 (Wickham, 2009), and asterisks and letters denoting significant effects of experimental factors were added in Inkscape (Inkscape'sContributors, 2019).

LOM and MBC content were both generally higher than observed in environmental samples and corresponded to MBC : LOM ratios at the high end of ranges observed in the field (2 %–11 % vs. 1 %–5 %; Santos et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2013). LOM and MBC values were within the range previously observed for simulations using DEMENT with daily litter inputs (Allison et al., 2014) but greater than those with just a single litter pulse (Allison, 2012; Allison and Goulden, 2017; Evans et al., 2017), indicating that these high biomass and litter C values can be attributed to these substrate inputs.

3.1 Intertaxon variability

To evaluate the effect of intertaxon CUE variability on LOM stocks, we ran the model at 20 ∘C (heated) under two scenarios and then compared the results to runs at 15 ∘C (control). In the first (homogeneous) scenario all taxa had an identical Ct, equal to 0 ∘C−1 (Fig. 1a). In the second (heterogeneous) scenario, Ct was assigned from a random uniform distribution bounded by −0.022 and 0.022 ∘C−1 (Fig. 1b). Therefore, the mean Ct of the heterogeneous scenario was 0 ∘C−1, matching that of the homogeneous scenario.

Figure 1Schematic of experimental design used in this study, where the CUE temperature response (Ct) varies as a function of the number of enzymes and/or taxonomic affiliation of organisms. Graphs show the effects of having homogeneous (a) or heterogeneous (b) Ct across taxa, the effect of forcing a positive (increase; c) or negative (decrease; d) correlation between the number of enzymes and Ct, bacteria showing a positive Ct and fungi a negative Ct (e), fungi showing an positive Ct and bacteria a negative Ct (f), or fungi and bacteria both having positive (g) or negative (h) Ct. Each point represents the combination of traits 1 of 10 taxa in the model might have, although 100 taxa were actually used in the simulations. Horizontal dashed lines indicate a Ct of zero, and clusters of points above and below this line denote when CUE tends to increase or decrease with increasing temperature. The letters F and B in the x axis of individual graphs denote sensitivities for fungi and bacteria, respectively. The trait values for different mock taxa may not be visible if the values for the traits on the two axes are identical. Figure prepared in BioRender.

Figure 2Density plot of the observed CUE temperature response for 23 soil bacterial isolates grown between 15 and 25 ∘C on four different liquid media types in the lab (n=160 datapoints, grey) and for soil microbial communities grown with various different substrates and temperatures based on a literature search (n=141 datapoints, brown). Vertical lines are placed at 0 (no change in CUE with temperature) as well as the ±0.022 ∘C−1 upper and lower limits used in the present study. Contributing datapoints are primarily derived from Qiao et al. (2019) and can be found in the Ct_literatureValues.txt file in OSF.

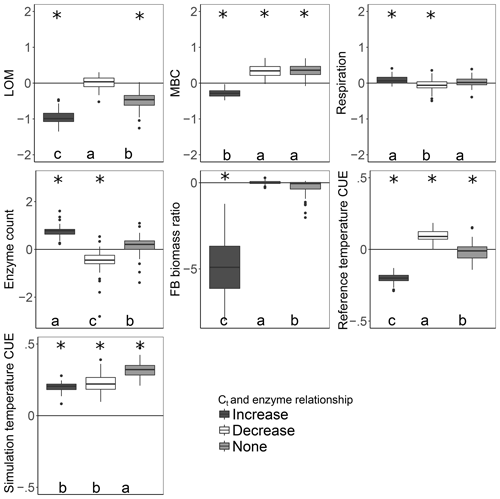

Introducing intertaxon differences in the CUE temperature response caused the characteristics of the initial microbial community (starting seed) to have a greater impact on litter decomposition than when all taxa had an identical temperature response (Table 2). This contrasts with the dampening effect proposed to explain instability in small-scale microbially explicit models compared to their macroscale counterparts (Wieder et al., 2015b). Specifically, Wieder et. al. (2015) proposed integrating diverse physiology into C-cycling models should allow different microbial subpopulations to follow distinct trajectories which average out to a more consistent community-level mean and greater certainty in model projections. However, we found that the additive effect of increased physiological diversity was to increase, rather than decrease, uncertainty in the present simulations. The median-standardized interquartile ranges of both MBC (0.25 vs. 0.16) and LOM (0.28 vs. 0.14) increased with the introduction of a variable Ct. Through species sorting, this heterogeneously responding microbial community became less diverse than both the homogeneous and control communities (Table 2). The communities characterized by heterogeneous Ct maintained a higher median microbial biomass – driving 2.5 times more LOM loss – than the communities characterized by a homogeneous Ct (Fig. 3). Intriguingly, neither litter (r=0.16, P=0.23) nor microbial biomass pool sizes (, P<0.001) positively correlated with extracellular enzyme investment; thus, a (nonsignificant) 28 % increase in the median enzyme count is unlikely to have driven the increased decomposition under the heterogeneous scenario. Instead, increased decomposition and increased biomass are likely the consequence of elevated CUE under warming conditions. Nonetheless, the nonlinearity of the model limits the degree to which causal relationships can be drawn between changes in litter C and the microbial parameters.

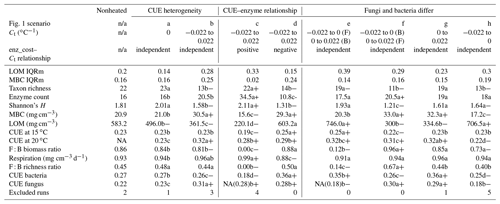

Table 2Median (or median-standardized interquartile range, IQRm) output values for various DEMENT model runs, marked according to warming effect () and model structure effects (letters) determined using Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests following linear mixed effect models. Symbols: “+” denotes the warming increased value; “−” denotes the warming decreased value. Letters denote differences between warmed scenarios. All heated scenarios were compared to values in the control column to determine the warming effect. Only values within boxes defined by vertical lines were evaluated for significance differences of the warming scenario, as different seeds needed to be excluded for failing to constrain litter accumulation in the two boxes. NA indicates that fungi died out completely in many instances (i.e., median fungal biomass of zero), so the parameter output could not be determined. The number in brackets denotes the median, excluding the scenarios where all the fungi died out. “Excluded runs” denote the number of runs removed from analysis due to unconstrained litter C accumulation.

n/a: not applicable.

Figure 3Effect of warming 5 ∘C on C stocks and flows in simulations, reported as the natural log of the ratio of values in heated compared to control conditions. The CUE temperature response either varied between taxa (heterogeneous) or took on the fixed cross-sample mean temperature response of zero. Values above the zero line indicate that warming increased the value, and values below indicate a decrease with warming. Boxplots denote the first to third quartiles with the median. Asterisks denote a significant warming effect based on a paired Wilcoxon test at Bonferroni-corrected P<0.0001. Letters denote warmed scenarios which are significantly different from one another using the same criteria. “Reference temperature CUE” denotes the ratio of CUE for the surviving community at 15 ∘C in the warmed scenarios to the ratio of CUE for the surviving community at 15∘ in the control scenarios, while “simulation temperature CUE” denotes the ratio of CUE in heated scenarios run at 20 ∘C to control scenarios run at 15 ∘C.

The homogeneous community scenario tested here is akin to the fixed “no adaptation of CUE” scenario reported in a number of other studies (Allison et al., 2010; Li et al., 2014; Sistla et al., 2014), because the cross-taxon mean used is the zero temperature response. However, the effect of intertaxon differences in Ct (heterogeneous) is less studied. Our results of reduced LOM loss in the absence of acclimation are consistent with two previous studies but contrast with others. In an ecosystem-level model parameterized for an arctic tundra system, Sistla et al. (2014) found that greater soil organic matter (SOM) loss occurred with warming when the microbial community was able to dynamically acclimate its C : N ratio (and in turn efficiency) than when the CUE was effectively fixed. Likewise, Allison (2014) found greater potential for increased LOM accumulation under warming when there was greater absolute variation in CUE across taxa (i.e., Cr from 0.18 to 0.58 rather than 0.38 to 0.58) (Allison, 2014), although Ct was always consistent across taxa in these simulations. On the other hand, a comparison of models where taxon-level differences in CUE or Ct are not possible (i.e., Ct is intrinsically homogeneous at the community level) showed that soil organic matter loss increases when organisms do not adapt (Li et al., 2014). Similarly, Wieder et al. (2015) found that greater SOM loss occurred if the CUE was directly insensitive to temperature than when Ct was negative (Wieder et al., 2014). These microbially explicit decomposition models vary in if and how they link CUE to microbial traits, and so our findings support the concept that nuances in how different components of CUE respond to warming are an important control on the fate of litter C (Hagerty et al., 2018).

3.2 The role of Ct as an additional niche dimension

We allowed for CUE to increase with temperature for a subset of taxa in a way that most previous modeling efforts have not, and so it is possible that our results deviate from those of prior studies not because of variation in Ct but rather because our simulations explore novel (positive Ct) parameter space. To facilitate comparison with previous decomposition modeling studies, we ran DEMENT simulations to test the effect of Ct being homogeneous vs. heterogeneous when CUE was either always positive (homogeneous Ct=0.011 ∘C−1, Fig. S1ai; heterogeneous Ct=0 to 0.022 ∘C−1, Fig. S1g) or always negative (homogeneous ∘C−1, Fig. S1aii; heterogeneous to 0 ∘C−1, Fig. S1h). In contrast to when Ct was allowed to vary over the whole spectrum of values, introducing heterogeneity in CUE did not increase inter-run uncertainty in LOM or MBC pools (Table S2). We also found that less LOM accumulated when CUE showed a variable decrease with warming than a fixed one (Fig. S2), which could be attributed to a reduction in MBC. By contrast, the homogeneous zero-centered and homogeneous positive Ct scenarios, and the heterogeneous zero-centered and heterogeneous positive Ct, behaved more similarly to one another in that warming decreased LOM while increasing MBC and CUE to a greater degree in the heterogeneous than homogeneous scenarios (Table S2). This finding reinforces the idea that if warming favors decomposer taxa capable of maintaining efficient growth, then soil C loss will be accelerated. Nonetheless, the strongly selected-for positive CUE response is rarely observed in complex soil communities. This indicates that additional tradeoffs with the CUE temperature response are likely at play when CUE is either unaffected or decreases with temperature, but that these tradeoffs are missing in the formulation of DEMENT used in this scenario. One such tradeoff possible to explore within the framework of DEMENT is the allocation of resources to extracellular enzyme activity.

3.3 Linkages between the CUE temperature response and extracellular enzyme allocation

Microbes depend upon extracellular enzymes to break down substrates in the environment into digestible pieces, and enzyme activities can be, like CUE, responsive to temperature (Wallenstein et al., 2010; German et al., 2012; Allison et al., 2018). Soil extracellular enzymes often are active in-situ at temperatures significantly below their apparent activity optima (German et al., 2012; Pold et al., 2017; Alster et al., 2018). Therefore, warming is assumed to enable them to process substrates at a higher rate in DEMENT (Allison, 2012), increasing the supply of growth substrates to microbes. However, the affinity of enzymes for their substrates may also decrease as temperature increases (German et al., 2012; Allison et al., 2018), as is assumed in DEMENT. If this is the case, then unless the enzyme Vmax increases faster with temperature than Km additional resources must be diverted from growth to enzyme production to maintain the microbial growth substrate supply rate. Therefore, taxa may differentially allocate resources to enzymes and so demonstrate a relationship between the temperature sensitivity of CUE and the number of enzymes they produce.

We evaluated whether litter decomposition changed its trajectory when the organisms with the greatest genomic potential to break the litter down (i.e., enzyme counts) also showed the most- or least-positive growth efficiency response to warming. In the increase scenario, we simulated a positive relationship between the temperature sensitivity of CUE and extracellular enzymes, where Ct increased linearly from −0.022 ∘C−1 for organisms with no extracellular enzyme production potential to 0.022 ∘C−1 for those organisms capable of producing the model maximum of 40 enzymes (Fig. 1c). In the decrease scenario, we simulated a negative relationship between the temperature sensitivity of CUE and extracellular enzymes, where the opposite relationship was imposed with Ct decreasing with enzyme counts (Fig. 1d). These scenarios were then compared to the heterogeneous scenario (also known as “no relation”, as described above), where Ct varied across the same range but independently of the number of enzymes an organism could produce. Therefore, the starting distribution of Ct and enzymes per taxon was identical across scenarios, and only their relationship with one another changed.

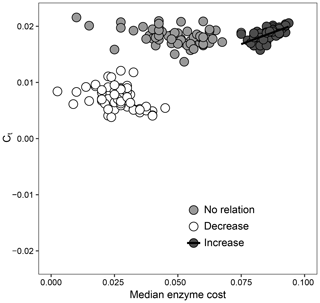

More taxa survived to the end of the simulation when warming was applied under the increase scenario than either the decrease or no-relation scenario (median of 13 versus 7 and 8, respectively; median absolute deviation is 2.97 in all cases). Under the increase scenario, taxa had 70 % more enzymes each than the no-relation scenario and more than three times as much as the decrease scenario (Table 2). This relationship caused the CUE of surviving taxa to be 20 %–37 % lower at 15 ∘C for the increase scenario compared to the others, but this deficit was diminished at 20 ∘C. As a result, the increase scenario led to higher respiration and a greater LOM loss under warming than under the “decrease” scenario, despite an overall smaller microbial biomass pool (Fig. 4).

Figure 4Effect of warming 5 ∘C on C stocks and flows in simulations, reported as the natural log of the ratio of values in heated compared to control conditions. The CUE temperature response was forced to increase, decrease, or remain independent of the number of enzymes a taxon could produce. Values above the zero line indicate that warming increased the value, and values below indicate a decrease with warming. Boxplots denote the first to third quartiles with the median. Asterisks denote a significant warming effect at P<0.0001 after correcting for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method. Letters denote warmed scenarios which are significantly different from one another using the same criteria. “Reference temperature CUE” denotes the ratio of CUE for the surviving community at 15 ∘C in the warmed scenarios to the ratio of CUE for the surviving community at 15∘ in the control scenarios, while “simulation temperature CUE” denotes the ratio of CUE in heated scenarios run at 20 ∘C to control scenarios run at 15 ∘C.

How the relationship between Ct and extracellular enzymes drives favorable trait combinations in DEMENT can also be observed in Fig. 5. Surviving taxa retained a median enzyme count of at least 30 and a realized CUE temperature response of no less than 0.0158 ∘C−1 under the increase scenario (ρ=0.64, P<0.001), but there was no relationship between the realized CUE temperature response and enzyme production under either the decrease or no-relation scenarios. The selection for a community capable of maintaining high CUE at high temperatures was much weaker when it was associated with reduced enzyme production. When there was no relationship between Ct and extracellular enzyme production costs, however, communities were able to attain a high realized CUE temperature response over a much wider range of median enzyme costs.

Figure 5Relationship between the enzyme cost and temperature sensitivity of surviving taxa when the relationship between Ct and the enzyme count is set to be positive (increase), negative (decrease), or nonexistent. Each point represents the value for the median across all surviving taxa for 1 of 59 starting communities.

These findings indicate that response traits – which determine how an organism reacts to changes in temperature (e.g., CUE temperature response) – and effect traits – which determine how an organism alters its environment (e.g., litter decomposition potential) – interact to determine the fate of organic C within DEMENT. However, contrary to our hypothesis, adjusting DEMENT to allow for this tradeoff did not substantially alter how community-level CUE responds to temperature. The observation that LOM is reduced further when enzyme production is effectively cheaper contrasts with earlier work with DEMENT (Allison, 2014) showing smaller litter C pools under both ambient and elevated temperature when enzymes and transporters were cheaper to produce. However, our results are consistent in that microbial biomass was lower when enzyme costs were high and that the microbial community was able to maintain a higher CUE under warming no matter the enzyme costs. The mechanisms underlying these phenomenological similarities differ, however, due to differences in how Ct was parameterized in the two sets of model simulations. Specifically, although microbes were able to attain high CUE at elevated temperatures in our simulations by balancing the benefits of elevated CUE at higher temperatures with the costs of enzyme production against CUE, CUE always decreased with temperature in earlier work with DEMENT (Allison, 2014). Furthermore, enzyme production costs varied both with and independently of enzyme counts in previous DEMENT simulations (Allison, 2014).

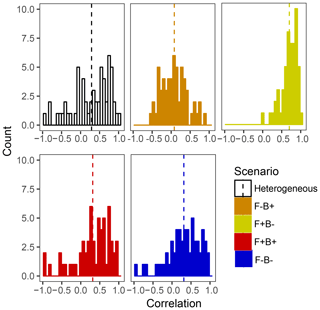

Within the framework of DEMENT, increased CUE is likely needed to offset the costs of extracellular enzyme production that allow taxa to remain competitive at elevated temperatures. However, there is a paucity of empirical evidence regarding the hypothesized correlations between the temperature sensitivity of CUE and enzyme investment in soil systems. By examining correlations between the number of enzymes an organism can produce and its CUE temperature response at the end of the DEMENT model run, we see that there is likely to be either no correlation or a positive correlation between the two variables rather than a negative one (Fig. 6). Limited data from bacterial isolates grown in the lab also support this, whereby the CUE temperature response is either positively correlated or uncorrelated with the number of enzymes produced (Pold et al., 2020). Furthermore, although the mechanisms underlying the isolate response remain unclear, the compilation of results from isolates is consistent with the scenario of Ct and enzyme counts being positively correlated. Specifically, we found isolates with lower CUE at 15 ∘C (more extracellular enzymes in DEMENT) were more likely to have a positive CUE temperature response than those with a higher CUE (fewer enzymes in DEMENT). Together, these insights support a synergism between the CUE temperature response and enzyme production rather than a tradeoff within the model. Because our DEMENT simulations indicate that selection for organisms characterized by high, positive CUE temperature responses with warming can alter both the directionality and extent of projected C loss, we propose it is important for other models to explore how possible increases – rather than just decreases – in Ct affect terrestrial C projections.

Figure 6Frequency histograms of Pearson correlation coefficients between the number of enzymes taxa which survive to the end of the 6000 d run and their Ct. Each panel corresponds to a different scenario shown elsewhere in the paper, with the counts in each bar corresponding to a single starting seed (community) under that scenario. Vertical lines denote the mean correlation coefficient for the scenario.

3.4 Ecological relevance of microbial metabolic diversity – bacteria vs. fungi

Across scenarios, fungi generally dominated the microbial biomass C pool (Table 2), as is typical for litter decomposition (Chapman et al., 2013, and references therein). This pattern occurred despite generally lower biomass-weighted CUE for surviving fungal taxa and preferential loss of fungal taxa across most scenarios (Table 2). The lower CUE for surviving fungi was not driven by higher enzyme costs than for bacteria, as median biomass-weighed enzyme costs were not statistically different (pairwise t-test P>0.4) and differed by less than one enzyme for the two groups. To test whether modeled differences in fungal vs. bacterial cell sizes and stoichiometry were driving this pattern, we tested how forcing differences in Ct in the two groups would impact the decomposition rate.

DEMENT was run with CUE simulated to respond to temperature: (1) negatively for all fungi and positively for all bacteria (F−B+; Fig. 1e), (2) negatively for all bacteria and positively for all fungi (F+B−; Fig. 1f), (3) positively for all bacterial and fungal taxa (F+B+; Fig. 1g), or (4) negatively for all bacterial and fungal taxa (F−B−; Fig. 1f). Minimum and maximum Ct were set to −0.022 and 0.022 ∘C, respectively. All four scenarios were tested in order to isolate the effect of changing taxonomic-domain–Ct relationships from simply changing Ct or taxonomic domain independently.

Litter C accumulated at higher rates with warming when fungal Ct was negative, regardless of the bacterial Ct (Fig. 7, blue, orange). This is consistent with the observation that the CUE of surviving fungi was lower at the simulation temperature in 7 out of the 11 scenarios. Because fungi have higher C : N : P ratios than bacteria (and thus higher C demands per unit biomass), we predicted that if fungi have a negative CUE temperature response, they would be weaker competitors at higher temperature than bacterial taxa, reducing their C demand and mitigating the warming effect on litter carbon stocks. While this contrasts with the premise that fungi should have a higher CUE (Six et al., 2006) due to their higher C : N ratio (Zak et al., 1996), it is consistent with a growing body of literature indicating that substrate quality – rather than the F : B ratio correlated with it – is the underlying driver of differences in CUE between soils (Thiet et al., 2006; Frey et al., 2013; Malik et al., 2018; Soares and Rousk, 2019). Despite the low nutrient content of the daily inputs to the model ( C : N : P), microbes did not show evidence for nutrient limitation as biomass C : N and C : P ratios were lower than are typical for soil communities (Xu et al., 2013) (4.1 and 36.7 vs. 7.6 and 42.4, respectively). Thus C was limiting, driven by a low Cr which is unresponsive to substrate stoichiometry in the model; this could have further disfavored the highly C demanding fungi when their Ct was negative. The lower CUE (and increased sensitivity to warming) for fungi compared to bacteria under a given scenario was also not driven by increased metabolic costs for enzyme production in fungi, as median biomass-weighted enzyme counts were statistically indistinguishable from those in bacteria.

Figure 7Effect of 5 ∘C of warming on components of the litter C cycle when bacteria and fungi show dissimilar (F−B+, orange; F+B−, yellow) or similar (F+B+, red; F−B−, blue) CUE responses to temperature. Values above the zero line indicate that warming increased the value (log ratio positive), and values below indicate a decrease with warming. Boxplots denote the first to third quartiles with the median. Asterisks denote a significant warming effect at P<0.0001 after correcting for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method. Letters denote warmed scenarios which are significantly different from one another using the same criteria. “Reference temperature CUE” denotes the ratio of CUE for the surviving community at 15 ∘C in the warmed scenarios to the ratio of CUE for the surviving community at 15∘ in the control scenarios, while “simulation temperature CUE” denotes the ratio of CUE in heated scenarios run at 20 ∘C to control scenarios run at 15 ∘C. Values for simulation temperature CUE are also shown for bacteria and fungi separately.

The litter C pool decreased when fungal CUE increased with temperature (Fig. 7), correlating with a smaller microbial biomass pool when bacterial CUE also decreased with temperature. By contrast, the LOM and MBC responses to warming were similar when only the Ct of bacteria was changed, indicating that it is the fungal warming response which really drives changes in litter decomposition in DEMENT. This result is interesting because no a priori differences in decomposition or uptake potential were imposed on the two groups, and fungal and bacterial richness was initially equivalent. Nonetheless, differences in C and nutrient translocation abilities as well as in cell size, stoichiometry, and turnover rates still defined the two groups. Warming decreased the enzyme costs when fungal Ct was positive but bacterial Ct was negative and decreased them under the opposing scenario, as evidenced by an increase in Cr in the former and a decrease in the latter. Nonetheless, as long as both bacterial and fungal CUE did not both decrease their CUE with temperature, community-level CUE remained higher at 20 ∘C than it was at 15 ∘C.

Empirical evidence for high-level differences in the temperature sensitivity of CUE in bacteria and fungi is currently mixed but indicates that the CUE temperature response for fungi is unlikely to be more positive than that for bacteria. Zheng et al. (2019) did not find a correlation between the lipid-based fungal : bacterial ratio and Q10 of CUE over a range of soils. However, we (Pold et al., 2020) and our colleagues (Eric Morrison, personal comment) have found that fungi tend to show a stronger negative CUE response with warming than do bacteria when examining them in isolation in the lab. This is consistent with the observation that fungal CUE decreases more strongly with warming than bacterial CUE does when Ct is restricted to negative values (Fig. 7). It is also consistent with the premise that bacterial growth benefits more from elevated temperature than does fungal growth in some soils (Pietikäinen et al., 2005). Greater empirical insight into the taxonomic drivers of the temperature sensitivity of CUE will assist with constraining the parameterization and projections of microbially explicit decomposition models such as DEMENT.

3.5 Comparison to empirical warming studies

Litter decomposition is typically observed to accelerate under warming (Lu et al., 2013). However, both the chemical composition of the litter and the identity of the living plant community at the site of decomposition are important for the magnitude of this response (Cornelissen et al., 2007; Ward et al., 2015). Consistent with these empirical studies – but inconsistent with a previous publication using DEMENT (Allison, 2014) – we found that litter decomposition was accelerated by warming in 7 of 10 scenarios. The range of losses and gains of litter C we observed with warming (−62 % (scenario c) to +42 % (scenario ai)) approximates the −65 % to +36 % change observed in field experiments (Lu et al., 2013), with the upper limit only being exceeded when Ct is constrained to negative values. Likewise, values for the simulated litter respiration response (−5 % to +6 %) were within a narrow range compared to those observed for soil respiration in the field (−48 % to +178 %), and responses for microbial biomass C were also within the observed range (−25 % to +58 % vs. −47 % to +86 %) (Lu et al., 2013). Our modeled responses to warming thus suggest that one possible explanation for differences in terrestrial C pool responses to warming may be diverse temperature sensitivities of underlying decomposer communities. Nonetheless, a number of additional factors must be taken into consideration when interpreting our results in the context of global climate change, including soil mineral-mediated modulation of the substrate supply (Schimel and Schaeffer, 2012; Coward et al., 2018), plant–microbe feedbacks (Melillo et al., 2011; Sistla et al., 2014; Suseela and Tharayil, 2018), and temporal variation in temperature. Furthermore, we modeled CUE as a somewhat inflexible property of individual taxa rather than as the emergent property of allocation to different, biochemically important physiological processes that it is (Hagerty et al., 2018). These are important features to pursue in future iterations of the model.

Our results indicate that accounting for the heterogeneous temperature response increases uncertainty regarding future litter C stocks but only when Ct does not differ from zero on average. However, by combining simulations, empirical studies, and literature searches, we can conclude that microbes with high enzyme costs are likely to have larger increases in intrinsic CUE with temperature, that taxa can sort on a CUE temperature response axis, and that fungi are more likely to increase CUE with warming than bacteria. The simulations meeting each or all of these criteria lead to the loss of litter C under warming, and so DEMENT supports the observation made by other studies that litter will become a net atmospheric C source in a warmer world (Song et al., 2019). Nonetheless, our results also indicate that litter C stocks may change heterogeneously with warming because of diversity in how decomposers' CUE responds to temperature. We encourage models functioning on larger scales to explore the effect of including heterogeneity in the temperature response of CUE in order to determine the robustness of our conclusions to other model structures. However, ultimately increased integration of the growing body of literature on the temperature sensitivity of CUE must be explored for root causes of heterogeneity in temperature sensitivity of CUE in taxa under in situ conditions.

The data and the modified version of DEMENT used to generate them are available from OSF (https://osf.io/cwep9/?view_only=de0e6ba7b7da493f96531f398ca62c2c, Pold, 2019).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-16-4875-2019-supplement.

GP, SAS, and KMD conceived the experiment; GP completed the experiment and analyzed data; GP wrote the first draft of the manuscript; all authors contributed to revising the manuscript and interpreting the results.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors wish to thank Steve Allison for sharing DEMENT and providing insight into troubleshooting the model. Thank you to Bin Wang and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments that improved our paper. Funding for this project came from the US Department of Energy grant DE-SC0016590 to Kristen M. DeAngelis and Seeta A. Sistla and from an American Association of University Women American Fellowship to Grace Pold.

This research has been supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science (grant no. DE-SC0016590); and the American Association of University Women (American Dissertation Writing Fellowship).

This paper was edited by Michael Weintraub and reviewed by Jörg Schnecker and two anonymous referees.

Allison, S.: A trait-based approach for modelling microbial litter decomposition, Ecol. Lett., 15, 1058–1070, 2012. a, b, c, d, e

Allison, S. D.: Modeling adaptation of carbon use efficiency in microbial communities, Front. Microbiol., 5, 1–9, 2014. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j

Allison, S. D. and Goulden, M. L.: Consequences of drought tolerance traits for microbial decomposition in the DEMENT model, Soil Biol. Biochem., 107, 104–113, 2017. a, b

Allison, S. D., Wallenstein, M. D., and Bradford, M. A.: Soil-carbon response to warming dependent on microbial physiology, Nat. Geosci., 3, 336–340, 2010. a, b, c, d

Allison, S. D., Lu, L., Kent, A. G., and Martiny, A. C.: Extracellular enzyme production and cheating in Pseudomonas fluorescens depend on diffusion rates, Front. Microbiol., 5, 169, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00169, 2014. a

Allison, S. D., Romero-Olivares, A. L., Lu, Y., Taylor, J. W., and Treseder, K. K.: Temperature sensitivities of extracellular enzyme Vmax and Km across thermal environments, Glob. Change Biol., 24, 2884–2897, 2018. a, b, c

Alster, C. J., Weller, Z. D., and von Fischer, J. C.: A Meta-Analysis of Temperature Sensitivity as a Microbial Trait, Glob. Change Biol., 24, 4211–4224, 2018. a, b

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., and Walker, S.: Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4, J. Stat. Softw., 67, 1–48, https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01, 2015. a

Blagodatskaya, E., Blagodatsky, S., Anderson, T.-H., and Kuzyakov, Y.: Microbial growth and carbon use efficiency in the rhizosphere and root-free soil, PloS One, 9, e93282, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093282, 2014. a

Boose, E.: Fisher Meteorological Station at Harvard Forest since 2001, Harvard Forest Data Archive: HF001, https://doi.org/10.6073/pasta/04076dfd30b286c6c29301b6345a63f5, 2001. a

Cavicchioli, R.: On the concept of a psychrophile, ISME J., 10, 793–795, 2016. a

Chapman, S. K., Newman, G. S., Hart, S. C., Schweitzer, J. A., and Koch, G. W.: Leaf litter mixtures alter microbial community development: mechanisms for non-additive effects in litter decomposition, PLoS One, 8, e62671, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062671, 2013. a

Cornelissen, J. H., Van Bodegom, P. M., Aerts, R., Callaghan, T. V., Van Logtestijn, R. S., Alatalo, J., Stuart Chapin, F., Gerdol, R., Gudmundsson, J., Gwynn-Jones, D., Hartley, A. E., Hik, D. S., Hofgaard, A., Jónsdóttir, I. S., Karlsson, S., Klein, J. A., Laundre, J., Magnusson, B., Michelsen, A., Molau, U., Onipchenko, V. G., Quested, H. M., Sandvik, S. M., Schmidt, I. K., Shaver, G. R., Solheim, B., Soudzilovskaia, N. A., Stenström, A., Tolvanen, A., Totland, Ø., Wada, N., Welker, J. M., Zhao, X., and Team, M. O. L.: Global negative vegetation feedback to climate warming responses of leaf litter decomposition rates in cold biomes, Ecol. Lett., 10, 619–627, 2007. a

Coward, E. K., Ohno, T., and Sparks, D. L.: Direct Evidence for Temporal Molecular Fractionation of Dissolved Organic Matter at the Iron Oxyhydroxide Interface, Environ. Sci. Technol., 53, 642–650, 2018. a

DeAngelis, K. M., Pold, G., Topçuoğlu, B. D., van Diepen, L. T., Varney, R. M., Blanchard, J. L., Melillo, J., and Frey, S. D.: Long-term forest soil warming alters microbial communities in temperate forest soils, Front. Microbiol., 6, 104, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00104, 2015. a

Devêvre, O. C. and Horwáth, W. R.: Decomposition of rice straw and microbial carbon use efficiency under different soil temperatures and moistures, Soil Biol. Biochem., 32, 1773–1785, 2000. a, b

Dijkstra, P., Dalder, J. J., Selmants, P. C., Hart, S. C., Koch, G. W., Schwartz, E., and Hungate, B. A.: Modeling soil metabolic processes using isotopologue pairs of position-specific 13C-labeled glucose and pyruvate, Soil. Biol Biochem., 43, 1848–1857, 2011a. a

Dijkstra, P., Thomas, S. C., Heinrich, P. L., Koch, G. W., Schwartz, E., and Hungate, B. A.: Effect of temperature on metabolic activity of intact microbial communities: evidence for altered metabolic pathway activity but not for increased maintenance respiration and reduced carbon use efficiency, Soil Biol. Biochem., 43, 2023–2031, 2011b. a

Evans, S., Martiny, J. B., and Allison, S. D.: Effects of dispersal and selection on stochastic assembly in microbial communities, ISME J., 11, 176–185, 2017. a

Frey, S. D., Lee, J., Melillo, J. M., and Six, J.: The temperature response of soil microbial efficiency and its feedback to climate, Nat. Clim. Change, 3, 395–398, 2013. a, b, c, d

German, D. P., Marcelo, K. R., Stone, M. M., and Allison, S. D.: The Michaelis–Menten kinetics of soil extracellular enzymes in response to temperature: a cross-latitudinal study, Glob. Change Biol., 18, 1468–1479, 2012. a, b, c

Geyer, K. M., Dijkstra, P., Sinsabaugh, R., and Frey, S. D.: Clarifying the interpretation of carbon use efficiency in soil through methods comparison, Soil Biol. Biochem., 128, 79–88, 2019. a, b

Hagerty, S. B., Allison, S. D., and Schimel, J. P.: Evaluating soil microbial carbon use efficiency explicitly as a function of cellular processes: implications for measurements and models, Biogeochemistry, 140, 269–283, 2018. a, b

Inkscape's Contributors: Inkscape, available at: https://inkscape.org, last access: January 2019. a

Kafri, M., Metzl-Raz, E., Jona, G., and Barkai, N.: The cost of protein production, Cell Reports, 14, 22–31, 2016. a

Kaleta, C., Schäuble, S., Rinas, U., and Schuster, S.: Metabolic costs of amino acid and protein production in Escherichia coli, Biotechnol. J., 8, 1105–1114, 2013. a

Kallenbach, C. M., Frey, S. D., and Grandy, A. S.: Direct evidence for microbial-derived soil organic matter formation and its ecophysiological controls, Nat. Commun., 7, 13630, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13630, 2016. a

Keiblinger, K. M., Hall, E. K., Wanek, W., Szukics, U., Hämmerle, I., Ellersdorfer, G., Böck, S., Strauss, J., Sterflinger, K., Richter, A., and Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S.: The effect of resource quantity and resource stoichiometry on microbial carbon-use-efficiency, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 73, 430–440, 2010. a

Lee, Z. M. and Schmidt, T. M.: Bacterial growth efficiency varies in soils under different land management practices, Soil Biol. Biochem., 69, 282–290, 2014. a

Lenth, R., Henrik, S., Jonathon, L., Paul, B., and Herve, M.: emmeans, Iowa State, available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/index.html (last access: November 2018), 2019. a

Li, J., Wang, G., Allison, S. D., Mayes, M. A., and Luo, Y.: Soil carbon sensitivity to temperature and carbon use efficiency compared across microbial-ecosystem models of varying complexity, Biogeochemistry, 119, 67–84, 2014. a, b, c, d, e, f

Li, J., Wang, G., Mayes, M. A., Allison, S. D., Frey, S. D., Shi, Z., Hu, X.-M., Luo, Y., and Melillo, J. M.: Reduced carbon use efficiency and increased microbial turnover with soil warming, Glob. Change Biol., 25, 900–910, 2018. a

Lu, M., Zhou, X., Yang, Q., Li, H., Luo, Y., Fang, C., Chen, J., Yang, X., and Li, B.: Responses of ecosystem carbon cycle to experimental warming: a meta-analysis, Ecology, 94, 726–738, 2013. a, b, c

Malik, A. A., Puissant, J., Buckeridge, K. M., Goodall, T., Jehmlich, N., Chowdhury, S., Gweon, H. S., Peyton, J. M., Mason, K. E., van Agtmaal, M., Blaud, A., Clark, I. M., Whitaker, J., Pywell, R. F., Ostle, N., Gleixner, G., and Griffiths, R. I.: Land use driven change in soil pH affects microbial carbon cycling processes, Nat. Commun., 9, 3591, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05980-1, 2018. a, b

Malik, A. A., Puissant, J., Goodall, T., Allison, S. D., and Griffiths, R. I.: Soil microbial communities with greater investment in resource acquisition have lower growth yield, Soil Biol. Biochem., 132, 36–39, 2019. a, b

Manzoni, S., Taylor, P., Richter, A., Porporato, A., and Ågren, G. I.: Environmental and stoichiometric controls on microbial carbon-use efficiency in soils, New Phytol., 196, 79–91, 2012. a

Melillo, J. M., Butler, S., Johnson, J., Mohan, J., Steudler, P., Lux, H., Burrows, E., Bowles, F., Smith, R., Scott, L., Vario, C., Hill, T., Burton, A., Zhou, Y.-M., and Tang, J.: Soil warming, carbon–nitrogen interactions, and forest carbon budgets, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 9508–9512, 2011. a

Oksanen, J., Blanchet, F. G., Friendly, M., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., McGlinn, D., Minchin, P. R., O'Hara, R. B., Simpson, G. L., Solymos, P., Stevens, M. H. H., Szoecs, E., and Wagner, H.: vegan: Community Ecology Package, R package version 2.4-2, available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan, last access: February 2017. a

Oldfield, E. E., Crowther, T. W., and Bradford, M. A.: Substrate identity and amount overwhelm temperature effects on soil carbon formation, Soil Biol. Biochem., 124, 218–226, 2018. a

Öquist, M. G., Erhagen, B., Haei, M., Sparrman, T., Ilstedt, U., Schleucher, J., and Nilsson, M. B.: The effect of temperature and substrate quality on the carbon use efficiency of saprotrophic decomposition, Plant Soil, 414, 113–125, 2017. a, b, c, d

Pietikäinen, J., Pettersson, M., and Bååth, E.: Comparison of temperature effects on soil respiration and bacterial and fungal growth rates, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 52, 49–58, 2005. a, b, c

Pold, G.: “DEMENT_CUE_Pold” OSF, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/CWEP9, last access: 30 November 2019. a

Pold, G., Grandy, A. S., Melillo, J. M., and DeAngelis, K. M.: Changes in substrate availability drive carbon cycle response to chronic warming, Soil Biol. Biochem., 110, 68–78, 2017. a

Pold, G., Domeignoz-Horta, L. A., Sistla, S. A., Morisson, E., Frey, S. D., and DeAngelis, K.: Carbon use efficiency and its sensitivity to temperature co-vary in soil bacteria, in press, 2020. a, b

Qiao, Y., Wang, J., Liang, G., Du, Z., Zhou, J., Zhu, C., Huang, K., Zhou, X., Luo, Y., Yan, L., and Xia, J.: Global variation of soil microbial carbon-use efficiency in relation to growth temperature and substrate supply, Sci. Rep., 9, 5621, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42145-6, 2019. a, b

R Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, available at: https://www.R-project.org/ (last access: April 2017), 2016. a

Santos, V. B., Araújo, A. S., Leite, L. F., Nunes, L. A., and Melo, W. J.: Soil microbial biomass and organic matter fractions during transition from conventional to organic farming systems, Geoderma, 170, 227–231, 2012. a

Schimel, J. and Schaeffer, S. M.: Microbial control over carbon cycling in soil, Front. Microbiol., 3, 348, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2012.00348, 2012. a

Sinsabaugh, R. L., Turner, B. L., Talbot, J. M., Waring, B. G., Powers, J. S., Kuske, C. R., Moorhead, D. L., and Follstad Shah, J. J.: Stoichiometry of microbial carbon use efficiency in soils, Ecol. Monogr., 86, 172–189, 2016. a

Sinsabaugh, R. L., Moorhead, D. L., Xu, X., and Litvak, M. E.: Plant, microbial and ecosystem carbon use efficiencies interact to stabilize microbial growth as a fraction of gross primary production, New Phytol., 214, 1518–1526, 2017. a

Sistla, S. A., Rastetter, E. B., and Schimel, J. P.: Responses of a tundra system to warming using SCAMPS: a stoichiometrically coupled, acclimating microbe–plant–soil model, Ecol. Monogr., 84, 151–170, 2014. a, b, c, d

Six, J., Frey, S., Thiet, R., and Batten, K.: Bacterial and fungal contributions to carbon sequestration in agroecosystems, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J., 70, 555–569, 2006. a

Soares, M. and Rousk, J.: Microbial growth and carbon use efficiency in soil: Links to fungal-bacterial dominance, SOC-quality and stoichiometry, Soil Biol. Biochem., https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01247, 2019. a

Song, J., Wan, S., Piao, S., et al.: A meta-analysis of 1,119 manipulative experiments on terrestrial carbon-cycling responses to global change, Nat. Ecol. Evol., 3, 1309–1320, 2019. a

Spohn, M., Klaus, K., Wanek, W., and Richter, A.: Microbial carbon use efficiency and biomass turnover times depending on soil depth–Implications for carbon cycling, Soil Biol. Biochem., 96, 74–81, 2016a. a, b

Spohn, M., Pötsch, E. M., Eichorst, S. A., Woebken, D., Wanek, W., and Richter, A.: Soil microbial carbon use efficiency and biomass turnover in a long-term fertilization experiment in a temperate grassland, Soil Biol. Biochem., 97, 168–175, 2016b. a, b

Suseela, V. and Tharayil, N.: Decoupling the direct and indirect effects of climate on plant litter decomposition: Accounting for stress-induced modifications in plant chemistry, Glob. Change Biol., 24, 1428–1451, 2018. a

Tang, J. and Riley, W. J.: Weaker soil carbon-climate feedbacks resulting from microbial and abiotic interactions, Nat. Clim. Change, 5, 56–60, 2015. a

Thiet, R. K., Frey, S. D., and Six, J.: Do growth yield efficiencies differ between soil microbial communities differing in fungal: bacterial ratios? Reality check and methodological issues, Soil Biol. Biochem., 38, 837–844, 2006. a

Walker, T. W., Kaiser, C., Strasser, F., Herbold, C. W., Leblans, N. I., Woebken, D., Janssens, I. A., Sigurdsson, B. D., and Richter, A.: Microbial temperature sensitivity and biomass change explain soil carbon loss with warming, Nat. Clim. Change, 8, 885–889, 2018. a

Wallenstein, M., Allison, S. D., Ernakovich, J., Steinweg, J. M., and Sinsabaugh, R.: Controls on the temperature sensitivity of soil enzymes: a key driver of in situ enzyme activity rates, in: Soil Enzymology, Springer, 245–258, 2010. a

Ward, S. E., Orwin, K. H., Ostle, N. J., Briones, M. J., Thomson, B. C., Griffiths, R. I., Oakley, S., Quirk, H., and Bardgett, R. D.: Vegetation exerts a greater control on litter decomposition than climate warming in peatlands, Ecology, 96, 113–123, 2015. a

Wickham, H.: ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, Springer-Verlag New York, available at: http://ggplot2.org, version 3.0.0, (last access: August 2018), 2009. a

Wieder, W. R., Bonan, G. B., and Allison, S. D.: Global soil carbon projections are improved by modelling microbial processes, Nat Clim Change, 3, 909–912, 2013. a, b, c

Wieder, W. R., Grandy, A. S., Kallenbach, C. M., and Bonan, G. B.: Integrating microbial physiology and physio-chemical principles in soils with the MIcrobial-MIneral Carbon Stabilization (MIMICS) model, Biogeosciences, 11, 3899–3917, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-3899-2014, 2014. a, b

Wieder, W. R., Grandy, A. S., Kallenbach, C. M., Taylor, P. G., and Bonan, G. B.: Representing life in the Earth system with soil microbial functional traits in the MIMICS model, Geosci. Model Dev., 8, 1789–1808, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-8-1789-2015, 2015a. a

Wieder, W. R., Allison, S. D., Davidson, E. A., Georgiou, K., Hararuk, O., He, Y., Hopkins, F., Luo, Y., Smith, M. J., Sulman, B., Todd‐Brown, K., Wang, Y.-P., Xia, J., and Xu, X.: Explicitly representing soil microbial processes in Earth system models, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 29, 1782–1800, 2015b. a

Xu, X., Thornton, P. E., and Post, W. M.: A global analysis of soil microbial biomass carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus in terrestrial ecosystems, Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr., 22, 737–749, 2013. a, b

Ye, J., Bradford, M. A., Dacal, M., Maestre, F. T., and García‐Palacios, P.: Increasing microbial carbon use efficiency with warming predicts soil heterotrophic respiration globally, Glob. Change Biol., 25, 3354–3364, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14738, 2019. a, b

Zak, D. R., Ringelberg, D. B., Pregitzer, K. S., Randlett, D. L., White, D. C., and Curtis, P. S.: Soil microbial communities beneath Populus grandidentata grown under elevated atmospheric CO2, Ecol. Appl., 6, 257–262, 1996. a

Zheng, Q., Hu, Y., Zhang, S., Noll, L., Böckle, T., Richter, A., and Wanek, W.: Growth explains microbial carbon use efficiency across soils differing in land use and geology, Soil Biol. Biochem., 128, 45–55, 2019. a, b, c, d, e, f