the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Pyrite oxidization accelerates bacterial carbon sequestration in copper mine tailings

Yang Li

Zhaojun Wu

Xingchen Dong

Zifu Xu

Qixin Zhang

Haiyan Su

Zhongjun Jia

Qingye Sun

Polymetallic mine tailings have great potential as carbon sequestration tools to stabilize atmospheric CO2 concentrations. However, previous studies focused on carbonate mineral precipitation, whereas the role of autotrophic bacteria in mine tailing carbon sequestration has been neglected. In this study, carbon sequestration in two samples of mine tailings treated with FeS2 was evaluated using 13C isotope, pyrosequencing and DNA-based stable isotope probing (SIP) analyses to identify carbon fixers. Mine tailings treated with FeS2 exhibited a higher percentage of 13C atoms (1.76±0.06 % for Yangshanchong and 1.36±0.01 % for Shuimuchong) than did controls over a 14-day incubation, which emphasized the role of autotrophs in carbon sequestration with pyrite addition. Pyrite treatment also led to changes in the composition of bacterial communities, and several autotrophic bacteria increased, including Acidithiobacillus and Sulfobacillus. Furthermore, pyrite addition increased the relative abundance of the dominant genus Sulfobacillus by 8.86 % and 5.99 % in Yangshanchong and Shuimuchong samples, respectively. Furthermore, DNA SIP results indicated a 8.20–16.50 times greater gene copy number for cbbL than cbbM in 13C-labeled heavy fractions, and a Sulfobacillus-like cbbL gene sequence (cbbL-OTU1) accounted for 30.11 %–34.74 % of all cbbL gene sequences in 13C-labeled heavy fractions of mine tailings treated with FeS2. These findings highlight the importance of the cbbL gene in bacterial carbon sequestration and demonstrate the ability of chemoautotrophs to sequester carbon during sulfide mineral oxidation in mine tailings. This study is the first to investigate carbon sequestration by autotrophic bacteria in mine tailings through the use of isotope tracers and DNA SIP.

- Article

(1639 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(71 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Soil ecosystems have great potential as carbon sinks to stabilize CO2 and regulate climate change (White et al., 2000). Atmospheric CO2 can be fixed in plants via photosynthesis and assimilated into soils via decomposition and microbial activity (Deng et al., 2016; Antonelli et al., 2018), and autotrophic bacteria play a significant role in carbon sequestration in soil ecosystems (Berg, 2011; Alfreider et al., 2017). Six autotrophic carbon sequestration mechanisms are widespread, including the Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) cycle, the reductive tricarboxylic acid (rTCA) cycle, the reductive acetyl-CoA pathway, and the recently discovered 3-hydroxypropionate–4-hydroxybutyrate (HP–HB) cycles (Berg, 2011; Alfreider et al., 2017). Among them, the CBB cycle is the most prevalent means of CO2 fixation by autotrophs including autotrophic bacteria (Tabita, 1999; Berg, 2011). The enzyme ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) is important in the CBB cycle and is in fact the most prominent enzyme on Earth (Raven, 2013). The cbbL and cbbM genes encoding the large subunit of RuBisCO, with 25 % to 30 % amino acid sequence identity (Tabita et al., 2008), serve as autotroph markers (Berg, 2011; Alfreider et al., 2017).

Compared with soil ecosystems, polymetallic mine tailings exhibit specific features, including a lack of organic matter, nutrients, and nutrient-holding capacity (Lottermoser, 2010; Young et al., 2015); these characteristics restrict plant growth, and it is generally difficult to restore plant productivity in mining wastelands (Li et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2018). As the limited amount of organic matter in mine tailings also inhibits the activities of heterotrophic bacteria, the microbes in these environments are dominated by lithotrophs (Li et al., 2015), and these autotrophic bacteria may accordingly play a role in organic carbon sequestration in mine tailings that cannot be ignored. In addition, polymetallic mine tailings have considerable potential to stabilize levels of atmospheric CO2 (Harrison et al., 2013) through the carbonation of noncarbonate minerals, including dissolution of silicates, hydroxides, and oxides and precipitation of carbonate minerals (McCutcheon et al., 2014, 2016; Meyer et al., 2014). However, previous studies have mainly focused on carbonate mineral precipitation, whereas the role of autotrophic bacteria in carbon sequestration by mine tailings has been overlooked.

Polymetallic mine tailings contain sulfide minerals (e.g., pyrite), and oxidation of these sulfide minerals leads to a decrease in pH, also known as mine tailing acidification. Previous studies have noted that due to the limited amount of organic matter present, polymetallic mine tailings have lithotroph-dominated microbial compositions (Li et al., 2015). Consequently, acidophilic, chemoautotrophic bacteria, including Acidithiobacillus, Leptospirillum, and Sulfobacillus (Chen et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014), largely participate in ferrous and sulfur oxidation in mine tailings, and these autotrophic taxa have leading roles in carbon cycling and energy flow during the mine tailing acidification process. Nonetheless, the relationship between the oxidation of sulfide minerals and carbon sequestration by these acidophilic chemoautotrophic bacteria remains unknown. In the present study, we conducted a microcosm experiment using mine tailings collected from two sites to determine the effects of sulfide mineral (pyrite) oxidation on carbon sequestration in mine tailings through pyrite addition. The main carbon fixers were also examined using DNA-based stable isotope probing (DNA SIP) and cbbL and cbbM gene analysis. Our objectives were to investigate whether sulfide mineral oxidation can stimulate carbon sequestration in mine tailings and to identify key carbon sequestration groups in mine tailings during the acidification process.

2.1 Sampling of mine tailings

Samples of mine tailings were collected from the Tongling Yangshanchong (30∘54′ N, 117∘53′ E) and Shuimuchong (30∘55′ N, 117∘50′ E) mine tailing ponds of copper mines in Anhui Province, east China. Samples of oxidized mine tailings on the surface (0–20 cm) were collected using a steel corer in October 2015. The mine tailing samples were placed in sterilized plastic bags, transported to the laboratory in an ice cooler, and stored at −20 ∘C before analysis. The properties of the mine tailings were as follows:

-

Yangshanchong acidic samples had a pH of 3.21, total nitrogen (TN) of 0.11 g kg−1, total organic carbon (TOC) of 16 g kg−1, of 13.32 g kg−1, AsT of 63.29 mg kg−1, FeT of 133.46 g kg−1, CuT of 1.95 g kg−1, PbT of 27.58 mg kg−1, and ZnT of 205.44 mg kg−1.

-

Shuimuchong acidic samples had a pH of 2.92, TN of 0.11 g kg−1, TOC of 18 g kg−1, of 8.84 g kg−1, AsT of 51.77 mg kg−1, FeT of 117.59 g kg−1, CuT of 2.53 g kg−1, PbT of 30.43 mg kg−1, and ZnT of 176.59 mg kg−1.

2.2 DNA SIP microcosms

A total of four treatments were established using microcosms of the two mine tailings. In the FeS2 treatment, fresh mine tailings (equivalent to 10.0 g d.w.s., dry weight soil) of each sample were mixed with a total of 2 g of sterile pulverized FeS2 at approximately 60 % maximum water-holding capacity, followed by incubation at 25 ∘C in the dark for 14 days. The microcosms were incubated with 10 % 13C-CO2 or 12C-CO2, and both treatments were constructed in triplicate for DNA SIP analysis. Yangshanchong mine (YM) tailing samples and Shuimuchong mine (SM) tailings cultured with FeS2 are abbreviated as YM_FeS2 and SM_FeS2; fresh mine tailings at approximately 60 % maximum water-holding capacity without any additive were used as the control groups and abbreviated as YM_ck and SM_ck.

2.3 Chemical property analysis

Carbon isotope composition was analyzed using a Delta V Advantage mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., USA) coupled with an elemental analyzer (Flash2000; HT Instruments, Inc., USA) in continuous-flow mode. The 13C atom % was calculated as follows:

The TOC content was assessed using an element analyzer (vario MACRO cube, Elementar Inc., Germany). The carbon isotope composition and TOC content were determined after soil acidification pretreatment to remove inorganic carbon, as described previously (Wang et al., 2015). The pH of the mine tailing samples was measured using a pH meter (tailings : water = 1 g : 5 mL) at the end of the microcosm experiment. Fe2+ and Fe3+ in the soils were extracted using HCl. Fe2+ in the extract was measured using a spectrophotometric method after mixing with phenanthroline and trisodium citrate; Fe3+ in the extract was reduced to Fe2+ by hydroxylammonium chloride and measured using the spectrophotometric method (Heron et al., 1994). The total sulfate ion content was determined via ion chromatography after extraction with sodium hydroxide, as described previously (Yin and Catalan, 2003).

2.4 DNA extraction and SIP gradient fractionation

Total DNA was extracted from each sample using the FastDNA® SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Cleveland, OH, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA-based stable isotope probing (DNA SIP) fractionation was performed as previously described (Zheng et al., 2014), and 14 gradient fractions were generated for each sample. The refractive index of each fractionated DNA was measured using an AR200 digital handheld refractometer (Reichert, Inc., Buffalo, NY, USA).

2.5 Real-time quantitative PCR analysis of the cbbL and cbbM genes

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis to determine the copy numbers of the cbbL, cbbM, and 16S rRNA genes in DNA gradient fractions from the YM_FeS2 and SM_FeS2 DNA SIP microcosms was performed using a CFX96 optical real-time detection system (Bio-Rad, Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The K2f–V2r primer pair (K2f: 5′-ACC AYC AAG CCS AAG CTS GG-3′ and V2r: 5′-GCC TTC SAG CTT GCC SAC CRC-3′) (Nanba et al., 2004), the cbbMF–cbbMR primer pair (cbbMF: 5′-TTC TGG CTG GGB GGH GAY TTY ATY AAR AAY GAC GA-3′ and cbbM-R: 5′-CCG TGR CCR GCV CGR TGG TAR TG-3′) (Campbell and Cary, 2004), and the 515F–907R primer pair (515F: 5′-GTG CCA GCM GCC GCG G-3′ and 907R: 5′-CCG TCA ATT CMT TTR AGT TT-3′) (Zhou et al., 2011) were used to amplify the cbbL, cbbM, and 16S rRNA genes, respectively. The reactions were performed in a 20 µL mixture containing 10.0 µL of SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa), each primer at 0.5 µM, and 1 µL of DNA template. qPCR analysis of the cbbL, cbbM, and 16S rRNA genes was performed under the following conditions: 40 cycles of 30 s at 95 ∘C, 30 s at 55 ∘C (cbbL and 16S rRNA genes) or 57 ∘C (cbbM gene), and 45 s at 72 ∘C. Standard curves were obtained using 10-fold serial dilutions of linearized recombinant plasmids containing the cbbL, cbbM, and 16S rRNA genes with known copy numbers. The amplification efficiencies were 90 %–100 %, with R2 values greater than 0.99.

2.6 Pyrosequencing of the 16S rRNA gene

The composition of the bacterial communities in different samples was assessed by 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing. The 16S rRNA gene from the 13C-labeled DNA fraction, with CsCl buoyant densities of 1.738 g mL−1 in the heavy fraction of YM_FeS2 and 1.734 g mL−1 in the heavy fraction of SM_FeS2, was also amplified for pyrosequencing. The primer pair 515F–907R was used for amplification of the V4–V5 regions of the 16S rRNA gene.

Primers were tagged with unique bar codes for each sample. Each sample was amplified in triplicate, and the products were pooled. Negative controls using sterilized water instead of soil DNA extract were included to check for primer or sample DNA contamination. The qualities and concentrations of the purified bar-coded PCR products were determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. The bacterial community composition of each sample was assessed by Illumina MiSeq sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene using MiSeq Reagent Kit v3.

Read merging and quality filtering of the raw sequences were performed using QIIME software with the UPARSE pipeline. The “identify_chimeric_seqs.py” command was used to identify chimeric sequences according to the UCHIME algorithm, and chimeric sequences were removed with the “filter_fasta.py” command. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were clustered with 97 % similarity, and OTU picking and taxonomy assignments were performed with the “pick_de_novo_otus.py” command for subsequent analysis. OTUs containing less than 10 reads in the 13C-labeled DNA fractions were removed. The raw amplicon sequence data for the 16S rRNA gene have been deposited in the GenBank sequence read archive under accession number SRP155504.

2.7 Clone library construction of the cbbL and cbbM genes

Clone libraries of the cbbL and cbbM genes were also constructed using 13C-labeled DNA fractions with CsCl buoyant densities of 1.738 g mL−1 in the YM_FeS2 heavy fraction and 1.734 g mL−1 in the SM_FeS2 heavy fraction. Primer pairs K2f–V2r and cbbMF–cbbMR were used to amplify the cbbL and cbbM genes, respectively. Triplicate amplicons were pooled, ligated to the pGEM-T vector (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA), and transformed into competent DH5.α cells. Sanger sequencing of randomly selected positive clones reveals 188 cbbL gene sequences and 183 cbbM gene sequences. OTU clustering with 97 % similarity was performed using mothur. Representative OTU sequences of the cbbL and cbbM genes obtained from clone library sequencing have been

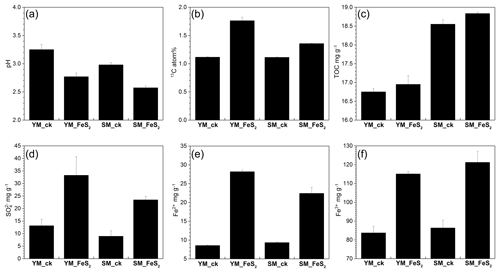

Figure 1pH values (a), 13C atom % (b), and TOC (c), (d), Fe2+ (e), and Fe3+ (f) contents in mine tailings. The error bars indicate the standard errors of three subsamples for each tailing sample. To determine 13C atom % (b), all analyzed samples were treated with 13C-CO2 in microcosms. YM_ck, control group of Yangshanchong mine tailings; SM_ck, control group of Shuimuchong mine tailings; YM_FeS2, Yangshanchong mine tailings treated with FeS2; SM_FeS2, Shuimuchong mine tailings treated with FeS2.

deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MH699091 to MH699105.

2.8 Data analysis

Bray–Curtis distance matrices for the overall bacterial community composition among the samples were calculated in R v.3.3.2 using the “vegdist” function of the vegan package and visualized by nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) in Origin 8. A heat map of dominant genera with relative abundances above 0.02 % was applied for plotting in the R environment using the pheatmap package. Translated cbbL and cbbM sequences from the heavy fractions were used to construct a phylogenetic tree with the neighbor-joining method using the MEGA package, version 7.0.

3.1 Pyrite oxidation and carbon sequestration

No significant changes in chemical properties, pH values (3.25±0.09 in YM_ck and 2.98±0.04 in SM_ck), sulfate () contents (13.15±2.58 mg g−1 in YM_ck and 8.95±2.19 mg g−1 in SM_ck), and TOC contents (16.75±0.09 mg g−1 in YM_ck and 18.55±0.12 mg g−1 in SM_ck) were found for the control groups compared to the original Yangshanchong and Shuimuchong acidic samples after 14 days of incubation (Fig. 1). However, the addition of pyrite decreased pH values in the YM and SM samples by 0.48±0.16 and 0.41±0.07, respectively. Pyrite addition also increased the content by 252.96 % and 262.35 %, Fe2+ content by 329.47 % and 240.38 %, and Fe3+ content by 137.47 % and 140.37 % in the YM and SM samples, respectively. Together, these data indicate the occurrence of pyrite oxidization and acidification in mine tailings after pyrite addition. Additionally, the TOC content increased by 0.20±0.11 mg g−1 in YM_FeS2 and 0.28±0.14 mg g−1 in SM_FeS2, and the 13C atom % values in YM_FeS2 (1.76±0.06 13C atom %) and SM_FeS2 (1.76±0.06 13C atom %) were higher than those in the controls YM_ck (1.12±0.01 13C atom %) and SM_ck (1.11±0.01 13C atom %). This result shows that fixation of 13C-CO2 occurred in these mine tailings with the addition of pyrite; the CO2-fixing capacities of autotrophs under FeS2 addition were 9.50±0.91 mg kg−1 d−1 in YM and 3.69±0.11 mg kg−1 d−1 in SM.

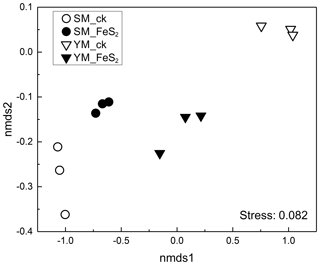

Figure 2Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) of the overall bacterial community composition according to Bray–Curtis distance matrices in mine tailings.

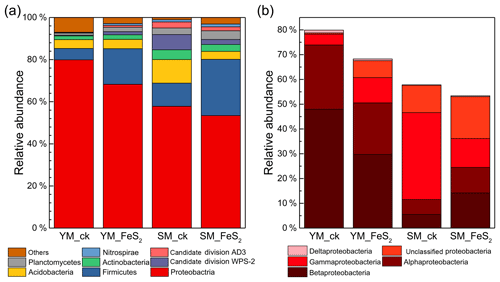

Figure 3Relative abundances (percentages) of the main bacterial taxonomic groups identified, i.e., Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, candidate division WPS-2, Planctomycetes, candidate division AD3, and Nitrospirae (a), and classes Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Deltaproteobacteria, and Gammaproteobacteria (within the phylum Proteobacteria) (b). For each tailing sample, the relative abundances of the sequences assigned to a given taxonomic unit were calculated for each of three subsamples, and the average value was then used to represent the relative abundance of each tailing sample.

3.2 Bacterial communities in mine tailings under FeS2 addition

A total of 220 877 usable sequences (mean 24 541, minimum 9362, maximum 28 400) were obtained from total genomic DNA. The ordering of samples by NMDS according to their OTU composition and Bray–Curtis dissimilarity measures (Fig. 2) demonstrated separation of the bacterial community structure in both YM and SM samples.

In this study, eight dominant bacterial phyla or candidate divisions (relative abundance >1 %) and four proteobacterial classes were identified in the two mine tailings, including Proteobacteria (mainly composed of classes Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, and Deltaproteobacteria), Firmicutes, Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, candidate division WPS-2, Planctomycetes, candidate division AD3, and Nitrospirae (Fig. 3). In the YM tailings, pyrite addition significantly increased the relative abundances of candidate division AD3, Nitrospirae, and unclassified Proteobacteria by 0.75 % (P=0.008), 0.59 % (P=0.019), and 6.33 % (P<0.001), respectively. Similarly, FeS2 addition to SM tailings significantly increased the relative abundances of Firmicutes, Planctomycetes, unclassified Proteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, and Deltaproteobacteria by 15.69 % (P<0.001), 0.97 % (P<0.001), 5.88 % (P=0.002), 4.35 % (P=0.001), 8.61 % (P<0.001), and 0.21 % (P=0.003), respectively. However, the percentages of candidate division AD3, Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Gammaproteobacteria in SM by 0.97 % (P=0.002), 7.43 % (P=0.002), 1.35 % (P=0.016), and 4.85 % (P=0.002) decreased in the SM tailings with pyrite addition.

Figure 4Heat map of the top genera with relative abundances above 0.02 % in mine tailings. Autotrophic bacteria were marked with underlining.

The total number of genera assigned to known taxa accounted for 29.89 % of the total bacterial communities. In addition, we constructed a heat map diagram (Fig. 4) that shows the top 51 dominant genera with relative abundances above 0.02 % in the mine tailings, accounting for 29.16 % of the total bacterial communities. Specifically, Sulfobacillus (8.04 %) and Novosphingobium (8.60 %) accounted for 16.64 % of the total bacterial communities and were the dominant taxa in the mine tailings. In contrast, autotrophic bacteria including Rhodanobacter (0.04 %), Pseudomonas (0.02 %), Acidithiobacillus (0.02 %), Thiobacillus (0.04 %), Ralstonia (0.02 %), Thiomonas (0.04 %), Burkholderia (0.09 %), Acidiphilium (1.49 %), Rhodobacter (0.04 %), Rhodoplanes (0.59 %), Nitrospira (0.02 %), Leptospirillum (0.80 %), Sulfobacillus (8.04 %), Clostridium (0.04 %), and Corynebacterium (0.04 %) accounted for 11.33 % of the total bacterial communities. Whereby, Thiobacillus, Acidiphilium, Leptospirillum, Acidithiobacillus, and Sulfobacillus are ferrous and sulfur-oxidizing bacteria. For the YM tailings, pyrite addition significantly increased the relative abundances of the autotrophic genera Acidithiobacillus, Leptospirillum, Sulfobacillus, and Acidiphilium by 0.02 % (P=0.001), 0.74 % (P=0.002), 8.86 % (P=0.043), and 1.57 % (P<0.001), respectively. FeS2 addition also significantly increased the relative abundances of autotrophic genera in the SM tailings: Rhodanobacter, Acidithiobacillus, Thiobacillus, and Sulfobacillus by 0.07 % (P=0.016), 0.03 % (P=0.034), 0.02 % (P=0.030), and 5.99 % (P<0.001), respectively.

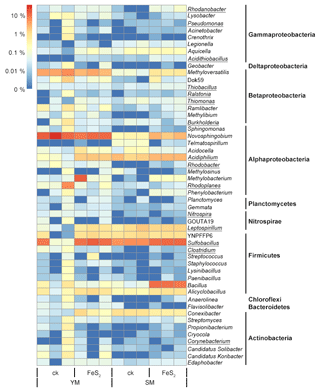

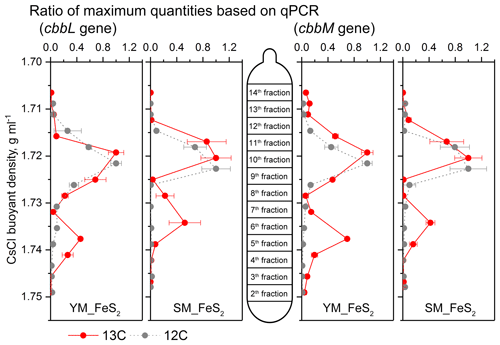

Figure 5Quantitative distribution of cbbL and cbbM gene fragments across the entire buoyant density gradients of the DNA fractions from microcosms treated with FeS2 and incubated with 12C-CO2 or 13C-CO2. The normalized data consist of the ratio of the gene copy number for each DNA gradient to the maximum quantity for each treatment. The error bars represent the standard errors of triplicate microcosms, and each consisted of three technical replicates. cbbL and cbbM gene abundance qPCR data are presented in the Supplement.

3.3 DNA SIP identification of autotrophs in mine tailings

For quantitative analysis of cbbL and cbbM gene abundances, the buoyant densities of the DNA in isopycnic centrifugation gradients were employed to assess the labeling efficiencies of cbbL or cbbM gene-carrying carbon fixers in the DNA SIP microcosms (Fig. 5). cbbL and cbbM gene levels under 13C-CO2 treatment peaked at a density of 1.72 g mL−1 in both the 12C-CO2 and 13C-CO2 treatments. In addition, a shift toward heavy fractions was observed for cbbL and cbbM gene abundances in the 13C-CO2 treatment (Fig. 5), with buoyant densities of 1.738 g mL−1 in YM_FeS2 and 1.734 g mL−1 in SM_FeS2. In contrast, the highest copy numbers of cbbL and cbbM genes under the 12C-CO2 treatment appeared in the light fraction, with a buoyant density of 1.722–1.723 g mL−1.

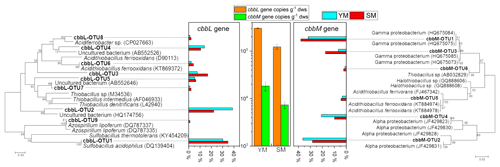

cbbL and cbbM sequences, encoding the large subunit of RuBisCO, from the clone libraries in the 13C-DNA heavy fraction treated with 13C-CO2 were used for phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 6). The gene copy numbers of cbbL were 16.50-fold and 8.20-fold greater than those of cbbM in the heavy fractions of YM_FeS2 and SM_FeS2, respectively. In addition, a vast majority of cbbL and cbbM gene sequences appear to be associated with unknown groups, with the exception of cbbL-OTU1, cbbL-OTU6, cbbL-OTU9, cbbM-OTU5, and cbbM-OTU6. According to phylogenetic analysis based on amino acid sequences, the cbbL gene OTUs are related to Sulfobacillus, Acidithiobacillus, and Azospirillum and the cbbM gene OTUs are related to Acidithiobacillus and Thiobacillus. The Sulfobacillus-like cbbL gene sequence cbbL-OTU1 accounted for 30.11 % and 34.74 % of the total cbbL gene sequences in the heavy fractions of YM_FeS2 and SM_ FeS2, respectively. Conversely, Acidithiobacillus-like cbbL and cbbM genes accounted for only 2.15 % and 4.21 % of the total cbbL gene sequences and 3.30 % and 4.35 % of the total cbbM gene sequences in the heavy fractions of YM_ FeS2 and SM_FeS2, respectively. In addition, the genus Sulfobacillus exhibited the highest relative abundance based on 16S rRNA analysis (Table S2), accounting for 17.18 % and 18.24 % of the heavy fractions of YM_FeS2 and SM_FeS2, respectively. The Leptospirillum genus accounted for 1.32 % and 1.58 % of the heavy fractions of YM_FeS2 and SM_FeS2, respectively, and Acidithiobacillus accounted for 0.11 % and 0.06 % in the heavy fractions of YM_FeS2 and SM_FeS2, respectively.

Figure 6Phylogenetic tree of translated cbbL and cbbM sequences in the heavy fractions from YM and SM treated with FeS2. Relative frequencies (%) are marked in the bar graph. Bootstrap values of >50 % are indicated at branch points. cbbL and cbbM gene copy numbers in the heavy fractions from FeS2-treated YM and SM are shown in the middle of the figure. The cultured genera most related to OTUs from cbbL and cbbM clone libraries are shown in Table S1.

4.1 The effect of FeS2 on the entire bacterial community in mine tailings

Acidic polymetallic mine tailings have strong potential for pyrite oxidation. In this study, a large amount of sulfuric acid was generated (increases of approximately 19.95 and 14.64 mg g−1 in YM_FeS2 and SM_FeS2, respectively), with a persistent decline in pH (decreases by 0.44 and 0.35 in YM_FeS2 and SM_FeS2, respectively), in only 14 days. These changes clearly indicate the oxidization of pyrite (i.e., acidification) in these mine tailings. Previous studies have found significant increases in certain bacterial phyla, such as Firmicutes and Nitrospirae (Chen et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014), with the acidification process of mine tailings. In the present study, the bacterial composition in the different mine tailings varied greatly, with only Firmicutes increasing in both tested mine tailings under pyrite addition. This group might participate in the oxidization of sulfide minerals (Chen et al., 2013), and Sulfobacillus accounted for the majority of Firmicutes. However, many other microorganisms might be inhibited under pyrite addition. Korehi et al. (2014) and Liu et al. (2014) also indicated that the ongoing oxidation process in mine tailings was accompanied by an increase in Firmicutes and a decrease in Actinobacteria as well as all classes of Proteobacteria except Gammaproteobacteria. In addition, Chen et al. (2013) and Liu et al. (2014) reported relative abundances of Euryarchaeota belonging to archaea significantly increased with decreasing pH, which indicates that this taxon is an indicator of metal contamination (Hur et al., 2011). Euryarchaeota compete with Betaproteobacteria for ecological niches under such acidic conditions (Liu et al., 2014). However, in this study archaea have been ignored, which will require further study.

The growth of microorganisms in bare mine tailings is usually limited by the availability of organic carbon (Schimel and Weintraub, 2003). In our study, pyrite oxidization in mine tailings further increased the acidity of the mine tailings (pH decreased to 2.77 and 2.57 in YM_FeS2 and SM_FeS2, respectively). As a result, only microorganisms that were able to overcome resistance to infertility and/or acidophilic conditions maintained high activities. The level of some specific taxa, including the autotrophic genera Acidithiobacillus and Sulfobacillus, increased in both of the tested mine tailings under pyrite addition (Fig. 4), indicating high consistency of dominant autotrophic bacterial genera in different mine tailings. It is possible that acidophilic and/or autotrophic bacteria might be stimulated under conditions of pyrite oxidization and the availability of organic carbon (Deng et al., 2016; Antonelli et al., 2018); moreover, the main carbon fixers in these two mine tailings may be derived from the same groups. In addition, levels of major ferrous and sulfur-oxidizing genera, autotrophic Leptospirillum and Acidiphilium in YM_ FeS2 and autotrophic Thiobacillus in SM_FeS2, were enhanced, suggesting the synchronization of pyrite oxidization and carbon sequestration in mine tailings.

4.2 The effect of FeS2 on bacterial carbon sequestration in mine tailings

Previous studies have shown that mine tailings provide an excellent substrate for carbon sequestration through the formation of carbonate due to the large surface area of the material grains (McCutcheon et al., 2016). Compared to soils and natural bedrock, mine tailings may exhibit higher carbonate precipitation rates (Wilson et al., 2009). Although the results showed that TOC content in mine tailings increased slightly under FeS2 addition, the soil acidification pretreatment and the addition of 20 % FeS2 in samples could increase the error of TOC analysis and calculation. And a long-term field test should be used to calculate the TOC increment in the acidification process of mine tailings in the future. Even so, in this study, the 13C content in mine tailings increased significantly (Fig. 1). DNA SIP analysis demonstrated assimilation of a considerable amount of 13C-CO2 by carbon fixers in the 13C-CO2-labeled mine tailing samples, leading to a significant shift in cbbL or cbbM gene-carrying genomic DNA into the heavy fraction. In addition, a peak at a buoyant density of 1.72 g mL−1 in 13C-CO2-labeled mine tailing samples was observed, with a density lower than the peak in the 12C-CO2-labeled control experiment (see Supplement); the intensity of the 13C peak at a higher density of 1.738 g mL−1 was also much lower than the 12C peak at a higher density of 1.72 g mL−1. This suggests that a large proportion of the autotrophic microorganisms detected in the mine tailing samples did not fix atmospheric carbon. All of these results indicate the contribution of special autotrophic bacteria to carbon sequestration in mine tailings. To the best of our present knowledge, this report is the first to investigate carbon sequestration by autotrophic groups in mine tailings based on isotope tracers and DNA SIP. Previous studies have found that microbial photosynthesis accelerates carbonate mineral precipitation and further induces mineralization (McCutcheon et al., 2014, 2016). In the present study, however, the microcosms were not cultured in the presence of illumination, and as a result, chemoautotrophic microorganisms, particularly iron and/or sulfide oxidizers (such as Sulfobacillus), were the dominant carbon fixers. These results indicate that bacterial carbon sequestration is mainly attributable to chemoautotrophic bacteria in mine tailings during pyrite oxidization. Nonetheless, archaea may have higher activities in RuBisCO-mediated carbon metabolic pathways (Kono et al., 2017), which will require further study.

During pyrite oxidization in mine tailings, some acidophilic autotrophic microorganisms showed very high activity levels; for example, levels of Sulfobacillus and Leptospirillum, both of which are vital ferrous and sulfur oxidizers, increased significantly. Zhang et al. (2016) identified genes for the CBB pathway and rTCA, but no other CO2 fixation pathways, in a copper bioleaching microbial community. Regarding the present study, the Sulfobacillus-like cbbL gene was the major carbon-fixing-associated gene found. Ňancucheo and Johnson (2012) reported that among acidophilic prokaryotes isolated from mine-impacted environments, the ability to metabolize glycerate-3-phosphate appeared to be restricted to Firmicutes (e.g., Sulfobacillus) and that the glycerate-3-phosphate present in all of these acidophiles might be due to the activity of RuBisCO (Ňancucheo and Johnson, 2012). Previous studies have confirmed the existence of Sulfobacillus in mine tailings (Coral et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2018), and members of this genus have the ability to oxidize or reduce Fe(III) and oxidize sulfur (Dold et al., 2005). This ability is important because by adhering to mineral surfaces and further enhancing sulfide mineral oxidation, Sulfobacillus likely leads to a high mineral dissolution rate (Becker et al., 2011; Li et al., 2016). Although none of the cbbL or cbbM genes identified in our study were highly homologous to genes in Leptospirillum, Marín et al. (2017) reported that rTCA carbon fixation pathway genes were mainly found in Leptospirillum spp. RuBisCO is the most prominent enzyme, and the genes encoding the large subunit of RuBisCO serve as a marker for the analysis of autotrophic organisms, including bacteria, using the CBB cycle (Berg, 2011). The Sulfobacillus-like cbbL gene dominated the 13C-labeled DNA among carbon-fixing taxa, and the higher relative abundance of Sulfobacillus than Leptospirillum, according to 16S rRNA analysis, demonstrates the contribution of the Sulfobacillus-like cbbL gene to carbon sequestration. Regardless, although the number (or relative abundance) of autotrophs demonstrated their ability to sequester carbon, it did not reflect their ability to perform or their importance to ferrous and sulfur oxidation. For example, the limited percentage of Acidithiobacillus in the two mine tailings did not reflect the contribution of this genus to the oxidation of iron and sulfur. Falagán et al. (2017) highlighted the importance of thermotolerant acidophiles, such as Acidithiobacillus and Sulfobacillus, in extracting and recovering metals from mine tailings. Furthermore, it has been known for many years that Acidithiobacillus can obtain energy by catalyzing oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ from sulfites (Dold, 2014), which may significantly accelerate the rate of ferrous oxidization. The decreased level of total carbon, including low-molecular-weight carboxylic acids, may also limit the activity of this taxon (Dold et al., 2005).

In conclusion, this study is the first to elucidate carbon sequestration by autotrophic groups in the mine tailing acidification process based on isotope tracers and DNA SIP. Our results reveal higher 13C atom % values with the addition of pyrite than in controls after a 14-day incubation. The Sulfobacillus genus was dominant in the pyrite-treated bacterial communities and was also the primary carbon fixer carrying the cbbL gene. Overall, the cbbL gene may play a vital role in carbon sequestration in the sulfide mineral oxidation of mine tailings.

The data are available from the first author and corresponding author upon request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-16-573-2019-supplement.

YL, XD, and ZJ led the design of the study, assisted by QS. All sample collection and analyses were performed by YL, ZW, ZX, QZ, and HS. YL wrote the paper with contributions from ZW.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China

(31800456), the National Key Basic Research Program of China (2015CB150506),

the Strategic Priority Research Program of the CAS (XDB15040000), the Natural

Science Foundation of the Anhui Provincial Education Department

(KJ2018A0032), and the PhD Research Startup Foundation of Anhui University

(J01003269).

Edited by: Luo Yu

Reviewed by: Weidong Kong and one anonymous referee

Alfreider, A., Baumer, A., Bogensperger, T., Posch, T., Salcher, M. M., and Summerer, M.: CO2 assimilation strategies in stratified lakes: Diversity and distribution patterns of chemolithoautotrophs, Environ. Microbiol., 19, 2754–2768, https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.13786, 2017.

Antonelli, P. M., Fraser, L. H., Gardner, W. C., Broersma, K., Karakatsoulis, J., and Phillips, M. E.: Long term carbon sequestration potential of biosolids-amended copper and molybdenum mine tailings following mine site reclamation, Ecol. Eng., 117, 38–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2018.04.001, 2018.

Becker, T., Gorham, N., Shiers, D. W., and Watling, H. R.: In situ imaging of Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans on pyrite under conditions of variable pH using tapping mode atomic force microscopy, Process. Biochem., 46, 966–976, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2011.01.014, 2011.

Berg, I. A.: Ecological aspects of the distribution of different autotrophic CO2 fixation pathways, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 77, 1925–1936, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.02473-10, 2011.

Campbell, B. J. and Cary, S. C.: Abundance of reverse tricarboxylic acid cycle genes in free-living microorganisms at deep-sea hydrothermal vents, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 70, 6282–6289, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.70.10.6282-6289.2004, 2004.

Chen, L., Li, J., Chen, Y., Huang, L., Hua, Z., Hu, M., and Shu, W.: Shifts in microbial community composition and function in the acidification of a lead/zinc mine tailings, Environ. Microbiol., 15, 2431–2444, https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.12114, 2013.

Coral, T., Descostes, M., De Boissezon, H., Bernier-Latmani, R., de Alencastro, L. F., and Rossi, P.: Microbial communities associated with uranium in-situ recovery mining process are related to acid mine drainage assemblages, Sci. Total Environ., 628–629, 26–35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.321, 2018.

Deng, X., Zhan, Y., Wang, F., Ma, W., Ren, Z., Chen, X., Qin, F., Long, W., Zhu, Z., and Lv, X.: Soil organic carbon of an intensively reclaimed region in China: Current status and carbon sequestration potential, Sci. Total Environ., 565, 539–546, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.042, 2016.

Dold, B.: Evolution of acid mine drainage formation in sulphidic mine tailings, Minerals, 4, 621–641, 2014.

Dold, B., Blowes, D. W., Dickhout, R., Spangenberg, J. E., and Pfeifer, H.-R.: Low molecular weight carboxylic acids in oxidizing porphyry copper tailings, Environ. Sci. Technol., 39, 2515–2521, https://doi.org/10.1021/es040082h, 2005.

Falagán, C., Grail, B. M., and Johnson, D. B.: New approaches for extracting and recovering metals from mine tailings, Miner. Eng., 106, 71–78, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2016.10.008, 2017.

Harrison, A. L., Power, I. M., and Dipple, G. M.: Accelerated carbonation of brucite in mine tailings for carbon sequestration, Environ. Sci. Technol., 47, 126–134, https://doi.org/10.1021/es3012854, 2013.

Heron, G., Crouzet, C., Bourg, A. C. M., and Christensen, T. H.: Speciation of Fe(II) and Fe(III) in contaminated aquifer sediments using chemical extraction techniques, Environ. Sci. Technol., 28, 1698–1705, https://doi.org/10.1021/es00058a023, 1994.

Hu, Y., Mgelwa Abubakari, S., Singh Anand, N., and Zeng, D.: Differential responses of the soil nutrient status, biomass production, and nutrient uptake for three plant species to organic amendments of placer gold mine-tailing soils, Land Degrad. Dev., 29, 2836–2845, https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3002, 2018.

Hur, M., Kim, Y., Song, H.-R., Kim, J. M., Choi, Y. I., and Yi, H.: Effect of genetically modified poplars on soil microbial communities during the phytoremediation of waste mine tailings, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 77, 7611–7619, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.06102-11, 2011.

Kono, T., Mehrotra, S., Endo, C., Kizu, N., Matusda, M., Kimura, H., Mizohata, E., Inoue, T., Hasunuma, T., Yokota, A., Matsumura, H., and Ashida, H.: A RuBisCO-mediated carbon metabolic pathway in methanogenic archaea, Nat. Comm., 8, 14007, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14007, 2017.

Korehi, H., Blöthe, M., and Schippers, A.: Microbial diversity at the moderate acidic stage in three different sulfidic mine tailings dumps generating acid mine drainage, Res. Microbiol., 165, 713–718, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmic.2014.08.007, 2014.

Li, Q., Sand, W., and Zhang, R.: Enhancement of biofilm formation on pyrite by Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans, Minerals, 6, e71, https://doi.org/10.3390/min6030071, 2016.

Li, X., Bond, P. L., Van Nostrand, J. D., Zhou, J., and Huang, L.: From lithotroph- to organotroph-dominant: Directional shift of microbial community in sulphidic tailings during phytostabilization, Sci. Rep., 5, 12978, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12978, 2015.

Li, Y., Sun, Q., Zhan, J., Yang, Y., and Wang, D.: Soil-covered strategy for ecological restoration alters the bacterial community structure and predictive energy metabolic functions in mine tailings profiles, Appl. Microbiol. Biot., 101, 2549–2561, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-016-7969-7, 2017.

Liu, J., Hua, Z., Chen, L., Kuang, J., Li, S., Shu, W., and Huang, L.: Correlating microbial diversity patterns with geochemistry in an extreme and heterogeneous environment of mine tailings, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 80, 3677–3686, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.00294-14, 2014.

Lottermoser, B. G.: Mine wastes: characterization, treatment and environmental impacts, Springer, New York, 2010.

Marín, S., Acosta, M., Galleguillos, P., Chibwana, C., Strauss, H., and Demergasso, C.: Is the growth of microorganisms limited by carbon availability during chalcopyrite bioleaching?, Hydrometallurgy, 168, 13–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2016.10.003, 2017.

McCutcheon, J., Power, I. M., Harrison, A. L., Dipple, G. M., and Southam, G.: A greenhouse-scale photosynthetic microbial bioreactor for carbon sequestration in magnesium carbonate minerals, Environ. Sci. Technol., 48, 9142–9151, https://doi.org/10.1021/es500344s, 2014.

McCutcheon, J., Wilson, S. A., and Southam, G.: Microbially accelerated carbonate mineral precipitation as a strategy for in situ carbon sequestration and rehabilitation of asbestos mine sites, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 1419–1427, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b04293, 2016.

Meyer, N. A., Vögeli, J. U., Becker, M., Broadhurst, J. L., Reid, D. L., and Franzidis, J. P.: Mineral carbonation of PGM mine tailings for CO2 storage in South Africa: A case study, Miner. Eng., 59, 45–51, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2013.10.014, 2014.

Nanba, K., King, G. M., and Dunfield, K.: Analysis of facultative lithotroph distribution and diversity on volcanic deposits by use of the large subunit of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 70, 2245–2253, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.70.4.2245-2253.2004, 2004.

Ňancucheo, I. and Johnson, D. B.: Acidophilic algae isolated from mine-impacted environments and their roles in sustaining heterotrophic acidophiles, Front. Microbiol., 3, e325, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2012.00325, 2012.

Raven, J. A.: Rubisco: still the most abundant protein of Earth?, New Phytol., 198, 1–3, 2013.

Schimel, J. P. and Weintraub, M. N.: The implications of exoenzyme activity on microbial carbon and nitrogen limitation in soil: a theoretical model, Soil Biol. Biochem., 35, 549–563, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0038-0717(03)00015-4, 2003.

Tabita, F. R.: Microbial ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase: A different perspective, Photosynth. Res., 60, 1–28, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1006211417981, 1999.

Tabita, R. S., Sriram, Hanson, T. E., Kreel, N. E., and Scott, S. S.: Distinct form I, II, III, and IV Rubisco proteins from the three kingdoms of life provide clues about Rubisco evolution and structure/function relationships, J. Exp. Bot., 59, 1515–1524, 2008.

Wang, G., Welham, C., Feng, C., Chen, L., and Cao, F.: Enhanced soil carbon storage under agroforestry and afforestation in subtropical China, Forests, 6, 2307–2323, 2015.

White, A., Cannell, M. G. R., and Friend, A. D.: CO2 stabilization, climate change and the terrestrial carbon sink, Global change biology, Glob. Change Biol., 6, 817–833, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000.00358.x, 2000.

Wilson, S. A., Dipple, G. M., Power, I. M., Thom, J. M., Anderson, R. G., Raudsepp, M., Gabites, J. E., and Southam, G.: Carbon dioxide fixation within mine wastes of ultramafic-hosted ore deposits: Examples from the Clinton Creek and Cassiar chrysotile deposits, Canada, Econ. Geol., 104, 95–112, 2009.

Yin, G., and Catalan, L. J.: Use of alkaline extraction to quantify sulfate concentration in oxidized mine tailings, J. Environ. Qual., 32, 2410–2413, 2003.

Young, I., Renault, S., and Markham, J.: Low levels organic amendments improve fertility and plant cover on non-acid generating gold mine tailings, Ecol. Eng., 74, 250–257, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.10.026, 2015.

Yu, R., Hou, C., Liu, A., Peng, T., Xia, M., Wu, X., Shen, L., Liu, Y., Li, J., Yang, F., Qiu, G., Chen, M., and Zeng, W.: Extracellular DNA enhances the adsorption of Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans strain ST on chalcopyrite surface, Hydrometallurgy, 176, 97–103, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2018.01.018, 2018.

Zhang, X., Niu, J., Liang, Y., Liu, X., and Yin, H.: Metagenome-scale analysis yields insights into the structure and function of microbial communities in a copper bioleaching heap, BMC Genetics, 17, 21 pp., https://doi.org/10.1186/s12863-016-0330-4, 2016.

Zheng, Y., Huang, R., Wang, B. Z., Bodelier, P. L. E., and Jia, Z. J.: Competitive interactions between methane- and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria modulate carbon and nitrogen cycling in paddy soil, Biogeosciences, 11, 3353–3368, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-3353-2014, 2014.

Zhou, J., Wu, L., Deng, Y., Zhi, X., Jiang, Y.-H., Tu, Q., Xie, J., Van Nostrand, J. D., He, Z., and Yang, Y.: Reproducibility and quantitation of amplicon sequencing-based detection, ISME J., 5, 1303-1313, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.11, 2011.