the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Geochemical consequences of oxygen diffusion from the oceanic crust into overlying sediments and its significance for biogeochemical cycles based on sediments of the northeast Pacific

Gerard J. M. Versteegh

Andrea Koschinsky

Thomas Kuhn

Inken Preuss

Sabine Kasten

Exchange of dissolved substances at the sediment–water interface provides an important link between the short-term and long-term geochemical cycles in the ocean. A second, as yet poorly understood sediment–water exchange is supported by low-temperature circulation of seawater through the oceanic basement underneath the sediments. From the basement, upwards diffusing oxygen and other dissolved species modify the sediment, whereas reaction products diffuse from the sediment down into the basement where they are transported by the basement fluid and released to the ocean. Here, we investigate the impact of this “second” route with respect to transport, release and consumption of oxygen, nitrate, manganese, nickel and cobalt on the basis of sediment cores retrieved from the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. We show that in this abyssal ocean region characterised by low organic carbon burial and sedimentation rates vast areas exist where the downward- and upward-directed diffusive fluxes of oxygen meet so that the sediments are oxic throughout. This is especially the case where sediments are thin or in the proximity of faults. Oxygen diffusing upward from the basaltic crust into the sediment contributes to the degradation of sedimentary organic matter. Where the sediments are entirely oxic, nitrate produced in the upper sediment by nitrification is lost both by upward diffusion into the bottom water and by downward diffusion into the fluids circulating within the basement. Where the oxygen profiles do not meet, they are separated by a suboxic sediment interval characterised by Mn2+ in the porewater. Where porewater Mn2+ in the suboxic zones remains low, nitrate consumption is low and the sediment continues to deliver nitrate to the ocean bottom waters and basement fluid. We observe that at elevated porewater manganese concentrations, nitrate consumption exceeds production and nitrate diffuses from the basement fluid into the sediment. Within the suboxic zone, not only manganese but also cobalt and nickel are released into the porewater by reduction of Mn oxides, diffusing towards the oxic–suboxic fronts above and below where they precipitate, effectively removing these metals from the suboxic zone and concentrating them at the two oxic–suboxic redox boundaries. We show that not only do diffusive fluxes in the top part of deep-sea sediments modify the geochemical composition over time but also diffusive fluxes of dissolved constituents from the basement into the bottom layers of the sediment. Hence, the palaeoceanographic interpretation of sedimentary layers should carefully consider such deep secondary modifications in order to prevent the misinterpretation of primary signatures.

- Article

(9514 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

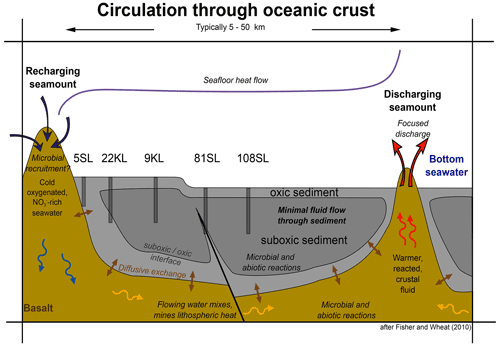

The heat flux from the mantle through the lithosphere into the ocean is high where the ocean crust is young and sediment cover sparse such as at spreading zones, and the heat flux typically decreases with age as the crust cools (e.g. Williams and von Herzen, 1974; Sclater et al., 1980; Davis et al., 1999). Ventilation of the basaltic crust by seawater is an important aspect of this cooling and is predicted to occur in off-axis settings up to an age of 65 Ma (e.g. Stein and Stein, 1992; Fisher et al., 2003; Hutnak et al., 2006). Most of the ocean floor has cooled over time, and conversely, most ventilation of the basaltic crust occurs at low temperatures (Hasterok et al., 2011; Coogan and Gillis, 2018). Water percolating through the crust changes the chemistry of the basement and vice versa (Fisher and Wheat, 2010; Orcutt et al., 2013). Moreover, sediments overlying the basement may be modified by substances diffusing from the crust upwards such as oxygen, whereas sedimentary products may diffuse down and interact with the crust and the fluid circulating therein (Ziebis et al., 2012; Orcutt et al., 2013; Mewes et al., 2016; Kuhn et al., 2017). Due to the vastness of the abyssal ocean floor, this low-temperature ventilation may have a large impact on the global geochemical and biogeochemical cycles (e.g. Baker et al., 1991). This impact is however poorly constrained. This is to a large extent due to sediments accumulating on the basement, making it less accessible; due to low sediment permeability, they progressively insulate the crust, both thermally and hydrodynamically (Anderson et al., 1979). As a result, water can enter or leave the basement only where sediment cover remains thin or absent such as at seamounts, ridges and faults. Finally, diffusion of dissolved species from the basement into the sediments and vice versa modifies the composition of both fluid and sediment and adds an extra aspect to the geochemical and biogeochemical impact of basement ventilation (e.g. Wheat and Mottl, 2000; Fisher et al., 2003; Wheat and Fisher, 2008; Mewes et al., 2016; Kuhn et al., 2017; Hulme et al., 2019).

1.1 Sediment geochemistry

The ocean floor is subject to a continuous rain of reduced material, notably organic matter (OM). Sedimentary life harvests the energy stored in this reduced material by exploiting and catalysing the redox reactions, giving priority to the energetically most favourable redox pair (e.g. Froelich et al., 1979; Berner, 1980). In oxic sediments, the dominant redox process is aerobic respiration. Oxygen entering the sediment by diffusion is consumed on its way down, and if sufficient OM is available, dissolved oxygen becomes exhausted resulting in an oxic–suboxic interface at depth. In a steady state situation, this interface keeps pace with sedimentation, and its depth relative to the sediment surface remains constant (e.g. de Lange et al., 1983; Kasten et al., 2003). From this interface downwards successively energetically less favourable redox reactions follow, provided sufficient electron donors remain (e.g. Canfield and Thamdrup, 2009; Kasten et al., 2003). However, due to successively reduced activation energies, oxidation of OM will be increasingly less complete (e.g. Tegelaar et al., 1989; Arnarson and Keil, 2007; Zonneveld et al., 2010). Dissolved redox products with remaining oxidation potential may diffuse to a zone with energetically more favourable redox reaction conditions and become further oxidised at the corresponding redox front (e.g. the oxic–suboxic interface). Oxidation of immobile components requiring a high activation energy slows down or even stops, leading to long-term preservation, as is the case of the more refractory OM below the oxic–suboxic interface (e.g. Arndt et al., 2013; Zonneveld et al., 2010).

Less input of reactive OM or lower sedimentation rates shift the balance between oxygen diffusion and its benthic consumption deeper into the sediment (e.g. Emerson et al., 2003). The result is increased oxygen exposure time of the sediments and a deeper oxic–suboxic interface, which can reach depths of up to several metres and more (Fischer et al., 2009; Rühlemann et al., 2011; Ziebis et al., 2012; Orcutt et al., 2013; Mewes et al., 2014, 2016; d'Hondt et al., 2015; Mogollón et al., 2016; Kuhn et al., 2017; Volz et al., 2018). The higher degree of OM degradation results in a more refractory residue. Conversely, OM degradation rates decrease more rapidly and to a larger extent with distance into the sediment as compared to regions with higher productivity and/or sedimentation rates (Mogollón et al., 2016).

In sediment-filled basins of the western flank of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge at “North Pond” and in the deep-sea sediments of the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in the northeast Pacific Ocean, oxygen was shown to diffuse not only downward across the sediment–water interface but also upward into the basal sediments from the underlying oceanic basement (Ziebis et al., 2012; Orcutt et al., 2013; Mewes et al., 2016; Kuhn et al., 2017). For this upward diffusion both oxygen concentration profiles and redox dynamics involved differ from those near the sediment surface. Oxygen concentrations of the fluids circulating in the permeable crust were demonstrated to be lower than those in the bottom water overlying the sediment surface due to partial consumption as a consequence of the oxidation of reduced mineral phase contained in the crustal basalt (Fisher and Wheat, 2010; Orcutt et al., 2013; Mewes et al., 2016). The oxygen entering the sediment from below also encounters old, refractory OM and meets electron donors diffusing down from the redox zones above. In this zone of upward-diffusing oxygen, oxygen exposure time of OM decreases upward from the sediment–basement interface and may have been very long, up to equalling the age of the sediment where this upward diffusive supply of oxygen never ceased.

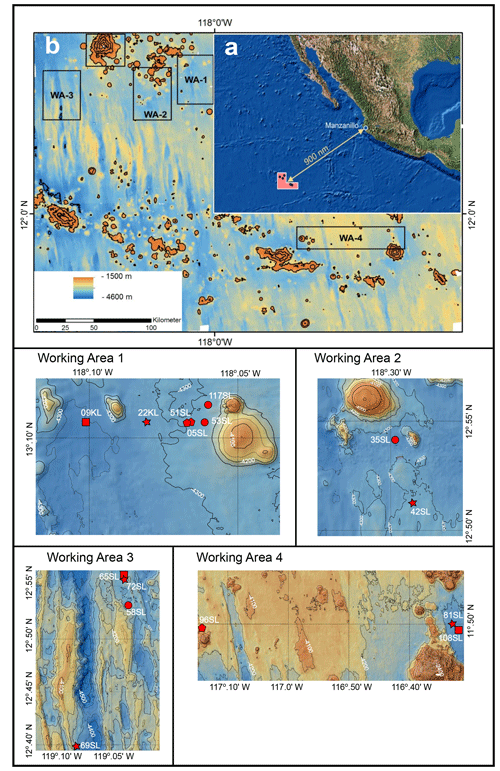

Although the upward diffusion of oxygen from the basement has only been documented for a few ocean environments, its impact on the sediment composition, OM preservation/burial and biogeochemical cycles is becoming better understood (e.g. D'Hondt et al., 2015, 2019a; Kuhn et al., 2017; Mewes et al., 2016; Morono et al., 2020; Ziebis et al., 2012). Still material and information are relatively limited. This is to a large extent a result of coring practice and/or list of parameters typically measured aboard ship. Mostly, coring devices such as piston and gravity corers are too short or the sediment cover involved too thick to reach beyond the redox zones in the upper-metre sediments and reach the deep oxic redox zone induced by the upward diffusion of oxygen from seawater circulating within the basement. Furthermore, although there is a long history of deeper drilling into the ocean sediments, and through them into the ocean crust (such as in the Deep Sea Drilling Project, DSDP, Ocean Drilling Program, ODP, and Integrated Ocean Drilling Program, IODP, frameworks), the instances during which ex situ oxygen measurements were performed on these long sediment cores are rare (e.g. Fischer et al., 2009; Ziebis et al., 2012; Orcutt et al., 2013; d'Hondt et al., 2013). To overcome this problem, we went to the northeast Pacific to the region of the CCZ in the framework of RV Sonne expedition SO240 (Kuhn et al., 2015) and among other porewater and solid-phase components performed ex situ oxygen measurements on whole-round gravity cores (Fig. 1). Sedimentation rates in the CCZ are low, ranging between 0.2 and 1.2 cm kyr−1 (Mewes et al., 2014; Volz et al., 2018), thus combining a relatively thin sediment cover with a long period of sedimentation and seawater circulation within the upper basaltic crust that delivered dissolved oxygen to the overlying sediment which penetrated the entire sediment column or at least to the deepest sediment recovered. Sediments with such low sedimentation rates represent about 70 % of the ocean floor (Bowles et al., 2014; Mewes et al., 2016), and conversely it has been suggested that extensive and long periods of oxidation are a widespread phenomenon in abyssal ocean deposits (D'Hondt et al., 2015, 2019b). Therefore, understanding the processes associated with upward oxygen supply from the basement into overlying sediments is crucial for our understanding of global biogeochemical cycles and for properly interpreting marine sedimentary records/archives. To shed more light on the exchange between the basaltic basement and the ocean, as well as the role of the oceanic sediments herein, the oceanic basement and overlying sediments of the abyssal plain in the CCZ were investigated seismically, thermally and geochemically during and after RV Sonne cruise SO240 in the framework of the project FLUM (Kuhn et al., 2015; Fig. 1).

Figure 1Maps (adapted from Kuhn et al., 2015). (a) Geographical setting. (b) Bathymetric map of the region of investigation with the four working areas indicated. The lower four panel cut-outs of bathymetric maps are of the four working areas with core locations indicated by red dots. Intervals between isobaths for working areas 1 to 3 are 50 m and 100 m for working area 4. A star signifies cores taken above a fault, a circle signifies cores taken near a seamount, a pentagon signifies cores taken above a fault and near a seamount, and a square signifies cores taken neither close to a seamount nor above a fault.

1.2 Study area

The oceanic basement underlying the sediments between the Clarion and the Clipperton fracture zones was formed from the late Cretaceous to the Miocene (Eittreim et al., 1992). The region hosts many seamounts and faults, which, due to their steep topography, are often barren of sediment on their slopes (e.g. Rühlemann et al., 2011). This allows seawater to circulate through the oceanic crust to enter or leave (Fisher and Wheat, 2010; Kuhn et al., 2017; Mewes et al., 2016). Sediment accretion is slow (typically a few mm kyr−1) due to the great distance from land, relatively great water depth, a low carbon flux to the seafloor of 1.5–1.8 (Lutz et al., 2007) and a seafloor below the current carbonate compensation depth. Metre-scale oxygen penetration into the sediment results in extensive organic matter mineralisation (total organic carbon, TOC, typically <0.2 % and mostly below 0.4 % at the surface) due to oxygen exposure times on the order of hundreds of thousands of years (e.g. Müller and Mangini, 1980; Mewes et al., 2016; Volz et al., 2018).

In this paper we concentrate on the impact dissolved inorganic substances migrating from the basaltic crust have on the overlying sediment and vice versa to better understand the impact of seawater ventilation of oceanic crusts on global biogeochemical cycles. We build upon recent insights on the low-temperature exchange of dissolved components between the basement and the overlying sediment and role of the sedimentary record (Mewes et al., 2014, 2016; Mogollón et al., 2016; Fisher and Wheat, 2010; Kuhn et al., 2017; Volz et al., 2018). We pay special attention to the upward diffusion of oxygen from the basement to obtain a better insight on its impact on sediment composition, preservation/burial of OM and its relevance for global biogeochemical cycles.

The oceanic crust in the region of investigation between 11.5∘ N, 116.3∘ W and 13.1∘ N, 119.6∘ W (Fig. 1) is of middle to late Eocene age (21–17 Ma) (Barckhausen et al., 2013). Sediment thicknesses are based on sediment echo sounding (PARASOUND) and single channel seismics using a 100 m streamer chain for signal detection and a GI airgun (Kuhn et al., 2015; Table 1). Sediments were recovered during RV Sonne cruise SO240 (Kuhn et al., 2015) by means of box, multiple, gravity and piston corers (Table 1; Fig. 1). Cores consist generally of stiff and compact brown clays with colour depending on the MnO2 contents. For example, less MnO2 (< concentration) resulted in a lighter brown colour and more MnO2 (> concentration) resulted in a darker colour (Kuhn et al., 2015). Of these, cores 22KL, 42SL, 72SL, 81SL and 96SL were taken close by or above a fault, cores 5SL, 35SL, 51SL, 53SL and 117SL were taken close to a seamount, core 69SL was taken near both a fault and a seamount, and cores 9KL, 58SL, 65SL and 108SL were taken near neither a fault nor a seamount.

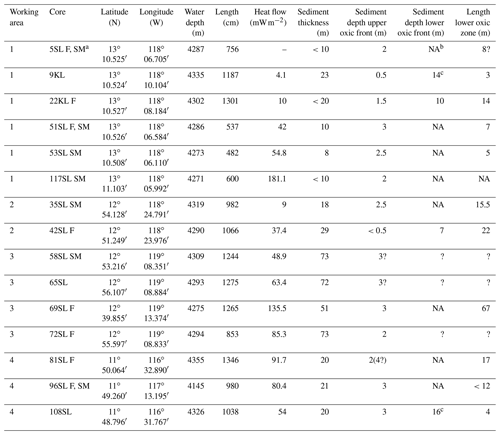

Table 1Sediment cores analysed (adapted from Kuhn et al., 2015).

a Core names: SL = gravity core, KL = piston core, F = core taken above a fault, SM = core taken near a sea mountain; b NA – not available; c Extrapolated from porewater Mn profile.

2.1 Oxygen analyses

Porewater oxygen in the retrieved sediments was determined ex situ on board using amperometric Clark-type oxygen sensors according to the procedure described by Revsbech (1989), Ziebis et al. (2012), Mewes et al. (2014, 2016), and Volz et al. (2018). For conversion of the measured millivolts to millimole per litre we used Eq. (1):

where V signifies sensor voltage at depth (Vd), under O2 saturation (Vsat) and in argon (VAr). O2(sol) is the oxygen solubility at the given temperature (measured), salinity (measured) and pressure (atmospheric pressure) conditions and was calculated using the equation of García and Gordon (1992). Measurements were performed in an acclimatised room kept at 4 to 6 ∘C.

2.2 Porewater sampling and analyses

Upon recovery of the sediment cores, porewater was sampled using rhizons according to the procedure described by Seeberg-Elverfeldt et al. (2005) with a typical average pore diameter of 0.1 µm (Mewes et al., 2014). For analyses a QuAAtro continuous segmented flow analyser was used (Seal Analytical). Porewater Mn2+, Ni2+ and Co2+ were determined after sample acidification with distilled HNO3 by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP–OES; IRIS Intrepid ICP–OES Spectrometer, Thermo Elemental) using the NIST2702 standard as reference and following the procedures described by Mewes et al. (2014).

2.3 Sediment analyses

For solid-phase element analysis, 50 mg of freeze-dried and homogenised bulk sediment was digested with a mixture of HF (0.5 mL, 40 %, Suprapur), HNO3 (3 mL, 65 %) and HCl (1.5 mL, 30 %, Suprapur) at 220 ∘C using a MARSXpress microwave system (CEM) as described by Nöthen and Kasten (2011). Major and trace elements were quantified in the laboratories of the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) in Bremerhaven and the Jacobs University Bremen using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP–MS) and inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP–OES), as well as at the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR) in Hanover by quantitative XRF (X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy) (Rietveld, 1967). Cross calibration, achieved by quantifying the same elements with ICP–MS, ICP–OES and XRF for a few cores, showed that the XRF measurements reliably reproduce the changes in the elemental composition of the sediment.

The total carbon content (TC), the content of organic carbon (Corg) and the total sulfur (TS) content were determined using a LECO CS230 carbon and sulfur analyser at the BGR. The samples were burned in a high-frequency oven at 1800–2200 ∘C, and the carbon and sulfur contents were determined using infrared detection. Untreated samples were used to determine TC and TS. Another sample aliquot was treated with 2N HCl at 80 ∘C to remove carbonate carbon and subsequently measured for Corg. The difference between TC and Corg equals carbonate carbon.

Porosity was calculated from the water content of samples with a known volume, corrected for salinity and using a bulk mineral density of 2.53 g cm−3 measured on core 22KL.

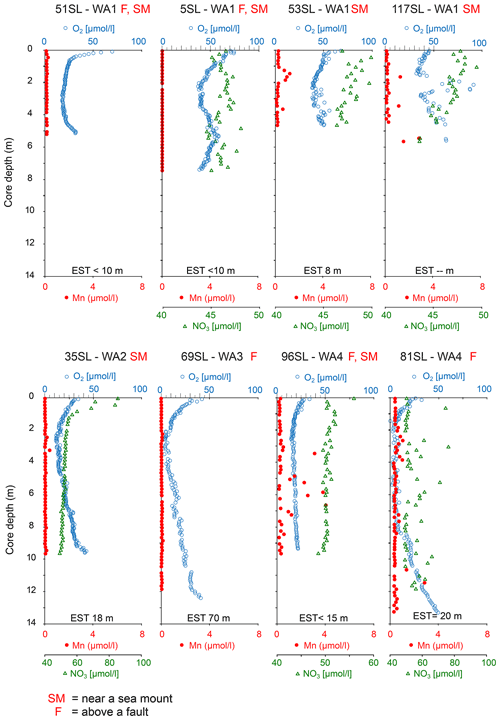

The oxygen profiles of the cores analysed which are oxic throughout are highly asymmetric. From core top to bottom, oxygen shows a strong decrease in the upper 30 cm and below a less pronounced decrease with depth leading to an interval of minimum oxygen concentrations between 2–3 m (Fig. 2). From there in most of these cores, a nearly linear re-increase in oxygen concentrations is observed towards the bottom of the cores (51, 53SL, 117SL, 35SL, 81SL, 69SL, 96SL; Fig. 2). Core 5SL does not entirely follow these general patterns but shows an S-shaped oxygen profile (Fig. 2) which we explain by assuming non-equilibrium from recent mass transport adding sediment at the location of this core and/or by lateral transport of oxygen, and for that reason we do not take this core into further consideration.

Figure 2Dissolved oxygen, manganese and nitrate profiles of cores without free porewater Mn2+. For all cores, nitrate profiles do not display significant denitrification beyond the uppermost metre (e.g. in 35SL). It is important to note that core 5SL may reflect disequilibrium conditions due to recent slumping and that nitrate increase with depth for 81SL is aberrant, as is the absence of free manganese. EST denotes estimated sediment thickness for each core (from Table 1). For cores 51SL and 69SL nitrate analyses were not possible due to insufficient porewater volume.

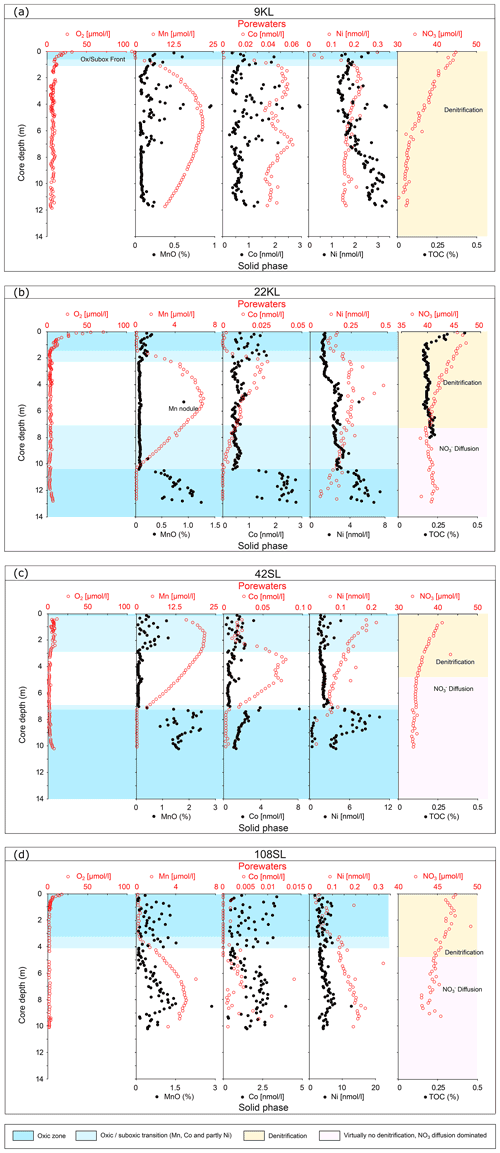

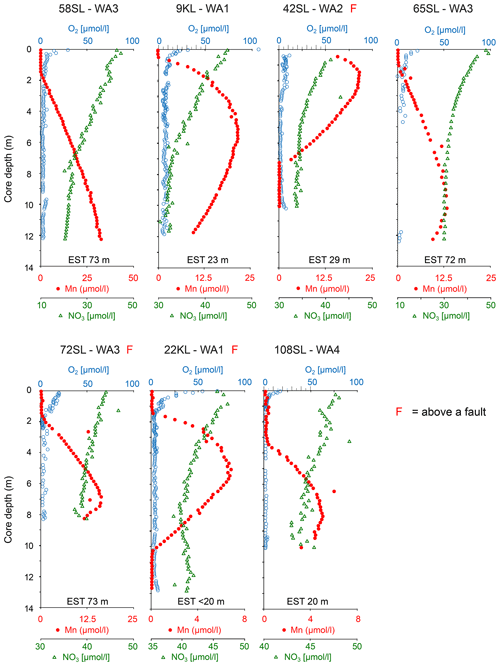

At two sites, these upper and lower oxic zones are separated by an intermediate suboxic interval as indicated by the presence of Mn2+ in the porewater (Fig. 3; 22KL, 42SL). There are five cores where the suboxic zone continues to the core bottom (9KL, 58SL, 65SL, 72SL, 108SL). Of these seven cores that are partly suboxic, none has been retrieved close to a seamount, and none except for 22KL and 42SL has been retrieved from above a fault. Except for 58SL, all cores which are partly suboxic show convex porewater Mn2+ profiles whereby the profile from the upper oxic–suboxic interface downward is steeper than the upward profile from the lower (extrapolated) oxic–suboxic interface. For core 22KL porewater oxygen concentrations decrease linearly with depth. For site 58SL a downward decrease in Mn2+ concentration is absent, and concentrations increase toward the core bottom.

Figure 3Dissolved oxygen, manganese and nitrate profiles of cores with free porewater manganese in order of maximum manganese concentrations (decreasing minimum nitrate values). For all cores nitrate values reach below the inferred value for basement fluid of 45 µmol L−1, suggesting the sediments at these locations are nitrate sinks. Core 22KL illustrates this with a nitrate minimum at 7 m core depth, indicating the depth where denitrification equals the nitrate fluxes from above and below. EST denotes estimated sediment thickness for each core (from Table 1).

In all but two cores porewater concentrations decrease downward from the core top (Figs. 2 and 3). For cores 22KL and 35SL the maximum is not at the sediment surface but slightly below in the top metre, and from this maximum the downward decrease commences (Figs. 2 and 3). In the cores with a suboxic zone the downward decrease in has a concave shape in the upper part, which is followed in the suboxic zone by a less steep linear decrease (9KL, 42SL, 58SL) or linear increase (22KL). The entirely oxic cores (35SL, 53SL, 117SL, 96SL) all display a linear downward decrease in . Extrapolation of the concentrations to the sediment–basement interface (see Table 1 for sediment thicknesses) provides values between 43 and 48 µmol L−1 at the interface for all oxic cores and for cores 22KL and 108SL. Core 5SL and the remaining cores with a suboxic interval (lower extrapolated concentrations) do not follow this general pattern.

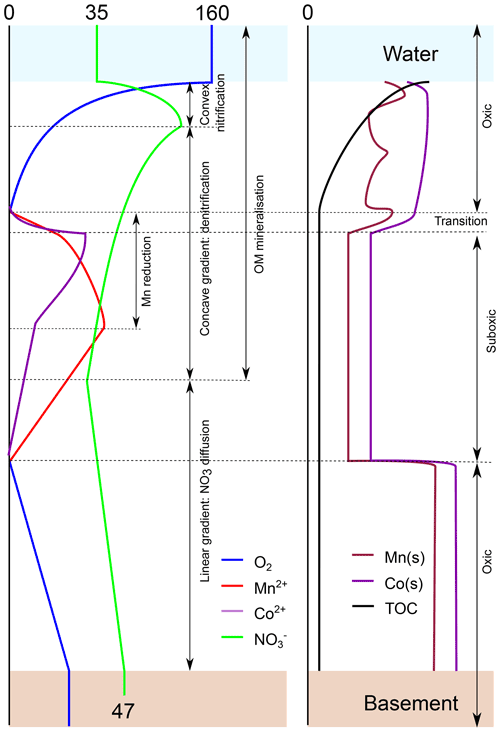

Porewater trace metals that co-vary in their concentrations with Mn are Co and to a lesser extent Ni (Fig. 4). In combination with the solid-phase data of these elements, we see from top to bottom (if present, Fig. 4) an oxic zone (for 22KL with clearly decreasing TOC values), without free porewater Mn and Co and with low porewater Ni and elevated solid-phase Mn, Co and Ni values, often with considerable scatter. Below this, a “transition zone” (Fig. 4) is present with low oxygen (and for core 22KL low and constant TOC) and solid-phase Mn, Co and Ni at the same level as in the oxic zone directly above, whereas in the porewater these elements mostly steeply decrease downward. Below this transition zone, solid-phase trace metal values are low, and porewater values are high. Below this, there is a sharp transition to oxic conditions without a transition zone. Like in the upper oxic zone, porewater Mn and Co are below the detection limit, and dissolved Ni is low again, while the solid-phase values of all three elements increase (Fig. 4). Dissolved Fe has not been detected in any of the porewaters, neither in the oxic nor in the suboxic sections. Solid-phase manganese for core 22KL shows an interval with low values in the suboxic interval.

For 63 %–91 % of the seafloor oxygen is high at the sediment–water interface and decreases to zero at depth (e.g. Wenzhöfer and Gludd, 2002; D'Hondt et al., 2015) due to mineralisation of organic matter (OM) or oxidation of reduced porewater and sediment compounds. The oxygen profile is concave since oxygen is consumed over the entire upper oxic zone (e.g. Froelich et al., 1979; Cai, and Sayles, 1996; Wenzhöfer and Gludd, 2002). The cores analysed in this study show the typical features of abyssal, carbon-starved ocean sediments with sufficient deep-water ventilation. OM oxygen exposure times are long, OM degradation is extensive, the remaining OM is refractory, and conversely sedimentary oxygen consumption rates are low. As expected, we observe oxygen penetrating several metres into the sediments (see also, for example, Fischer et al., 2009). Despite this, for some cores, sufficient degradable OM remains available to exhaust oxygen at depth. Below the oxic zone and with increasing sediment depth, we observe zones of denitrification and manganese reduction (Froelich et al., 1979; Berner, 1980; Mogollón et al., 2016; Volz et al., 2020). However, iron reduction and sulfate reduction were not observed due to the low content and reactivity of buried OM.

4.1 Porewater oxygen

As a result of core retrieval by gravity and piston corers, the surface sediment proper is usually lost or at least heavily disturbed. Oxygen concentrations in the bottom waters are close to 160 µmol L−1 (Mewes et al., 2014; Mogollón et al., 2016; Garcia et al., 2018) and rapidly decrease to values identical to those found for the gravity and piston cores discussed here within the upper 5 cm (not shown). The presence of a second, upward-directed diffusive flux of oxygen in many of the sediments investigated in our study and in some others suggests that oxygen is supplied from low-temperature seawater ventilation of the underlying basement. This seems to be a widespread phenomenon (Wheat and Fisher, 2008; Fisher and Wheat, 2010; Ziebis et al., 2012; Orcutt et al., 2013; Mewes et al., 2016; Kuhn et al., 2017). The interaction between the upward- and downward-directed oxygen profiles through time shapes the porewater and solid-phase element profiles in the investigated sediments. Two types of geochemical settings were encountered in the investigated sediments. One type is represented by entirely oxic sediments with concave oxygen profiles (Fig. 2) and the other by cores with a suboxic zone with a second oxic zone below where oxygen concentrations increase towards the core bottom (Fig. 3). A compilation of the extension of the upward and downward porewater oxygen and manganese profiles (Fig. 5) shows that the oxygen porewater profiles from the core top downward are restricted to the upper 3 m. The relatively constant thickness of the upper oxic zone of the sediments (mostly 2–3 m) for the oxic cores suggests that the combination of OM flux to the sediment and benthic mineralisation, oxygen diffusion, and sedimentation rate is relatively constant so that the system would turn into suboxic conditions somewhere below the upper 2–3 m. Although sedimentation rates in the area vary (Müller and Mangini, 1980; Mewes et al., 2014, 2016; Volz et al., 2018), they are significantly lower than the rate at which oxygen diffuses into the sediments and thus have no significant influence on the oxygen penetration depth. This would imply that the thickness of the sediment cover and the diffusive oxygen delivery from the basement into the overlying sediments, i.e. the steepness of the upward oxygen profile, in the end determine if, and to what extent, a suboxic zone is present in the sediment.

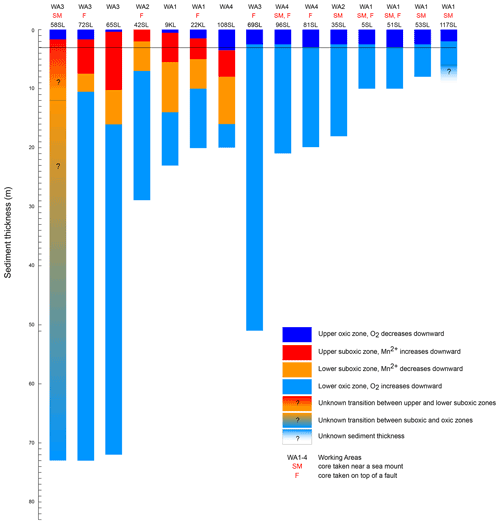

Figure 5Compilation of oxygenation states of cores for the entire sediment column (sediment surface to basement) taken during RV Sonne cruise SO240. Sediment thickness is based on seismic and parasound data (Kuhn et al., 2015); oxidation state based on core porewater oxygen and manganese concentrations. Note that for the totally oxic cores (blue only) the oxygen minimum (where the downward dark blue and upward light blue oxygen profiles meet) is always in the upper few metres. The upper oxic–suboxic transition also occurs in the upper few metres. The black line at 3 m depth marks the lower limit of the upper oxic zone for all cores except for 108SL.

In the case when oxygen consumption exceeds supply from above and below, two oxic–suboxic fronts are formed, with the intermediate suboxic zone having free Mn2+ in porewater. In a steady-state situation, both fronts represent metastable equilibria between diffusion of reduced compounds produced in the suboxic zone to the oxidation front and consumption and diffusion of oxygen in the oxic zones. Whereas in the upper oxic zone the concave oxygen profile indicates that oxygen is consumed over the entire oxic zone due to the presence of more reactive OM close to the sediment surface, in the lower oxic zone the linear oxygen profiles indicate that oxygen consumption along the profile is insignificant compared to that at the front (Fig. 3). In combination with sediment thickness, this linearity allows us to extrapolate the profiles to the basement and calculate basement oxygen concentrations in several instances (Table 2, using the seismic-based estimates of sediment thicknesses; Table 1). The values are thus obtained and vary strongly (from 29 µmol L−1 at 21 m in 96SL to 156 µmol L−1 at 51 m in 69SL), an observation also made for North Pond at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (Ziebis et al., 2012; Orcutt et al., 2013). The differences may be caused by, for example, differences in fluid advection velocities, by fluid path length in the basement in combination with the consumption of oxygen by reduced compounds in the basement or by proximity to subsurface faults (Kuhn et al., 2017). For core 69SL the projected value is very close to that of the bottom waters (160 µmol L−1), and, therefore, it is suggested that this core was taken close to an active site of bottom water uptake by the basaltic basement. To a lesser extent this is true for Site 51SL (131 µmol L−1). For sites with lower projected O2 concentrations at the bottom of the core, we infer a longer distance to the site of inlet or recharge and/or a more sluggish fluid circulation through the basaltic basement.

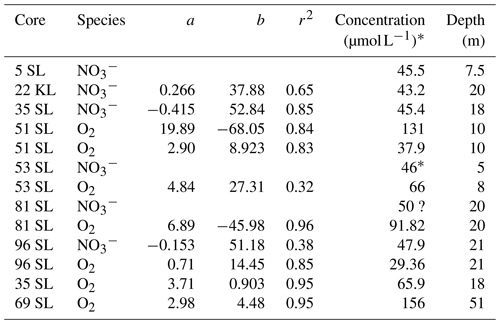

Table 2Linear regressions and extrapolated concentrations at the sediment base. Regressions are based on the lower, linear part of the O2 and profiles, whereby concentration in µmol L−1 = a × (sediment depth in metres) + b.

* Estimated from the values and trend at the core base.

For the partly suboxic sites the upper oxic–suboxic front is (logically) always shallower than the depth in the entirely oxic cores where the downward and upward O2 fluxes meet. The seafloor in the investigated region is not a smooth abyssal plain but is characterised by abundant seamounts of different heights. The variable and dynamic interaction of laterally flowing deep-water masses with these seamounts results in bottom water currents of variable speed. As such, deposition of OM raining to the seafloor will be uneven as well, with pockets enriched and areas impoverished in OM flux. We infer that this patchiness is the main factor causing the differences in the depth of the upper oxic–suboxic front, as already discussed by Mewes et al. (2014) and Volz et al. (2018). In the investigated region bioturbation depth is usually <7 cm and occasionally reaches twice as deep (Volz et al., 2018). This bioturbation depth is supported by the exponential decrease in oxygen concentrations, which is restricted to the upper 4–5 cm of the accompanying multicores. As such, bioturbation is much shallower than the depth of the oxic–suboxic front (50–300 cm) and thus plays no significant role in shaping the porewater profiles. The exception is 42SL for which suboxic conditions already prevail at the core top. However, in the accompanying multicore, the upper 25 cm measured are all oxic, whereas the rapid and exponential decrease in oxygen concentrations is restricted to the upper 3.5 cm. We thus infer that for site 42SL, an unusually thick section of the upper sediments has become lost upon core recovery, and also here the oxic–suboxic front was located >25 cm below the surface, well below the zone of bioturbation.

The influence of the sediment thickness on porewater oxygen profiles is evident from the cores from areas with a thin sediment cover, namely cores/sites 96SL, 5SL, 51SL, 53SL and 117SL which are all entirely oxic (Table 1; Fig. 5), whereas longer cores appear oxic or partly suboxic. Cores 9KL, 65SL, 58SL and 108SL are the only cores from areas characterised by sediment thicknesses of >15 m that are neither above a fault nor close to a seamount except for 58SL, and they all have an intermediate suboxic interval. Oxic core 81SL and partly suboxic core 108SL have similar lengths and were taken close to each other (Fig. 1), whereby core 81SL was taken above a fault in contrast to core 108SL. Considering the different lengths of the oxygen diffusion paths from below, we suggest that subsurface faults may facilitate upward oxygen diffusion, thus explaining the absence of a suboxic zone for core 81SL, as already suggested by Kuhn et al. (2017). The presence of a fault may also explain why oxygen penetrates further upwards at site 72SL (near fault) compared to 65SL (no fault) despite both cores having been taken close to each other (Fig. 1) and having a similar sediment cover (73 and 72 m respectively; Fig. 5). The presence of an underlying fault may also explain why core 69SL is entirely oxic despite the thickness of the sediment cover. Finally, it may explain why in core 22KL the lower oxic–suboxic interface is located at a shallower sediment depth than in core 9SL. At extensional faults, pore volumes may increase, so it is conceivable that faults increase sediment permeability. However, for these cores (>10 m thickness), fluid advection may be neglected due to the low permeability of these sediments (Spinelli et al., 2004; Kuhn et al., 2017).

Apart from sediment thickness and the effect of faults, the oxygen concentration at the sediment–basement interface is a third variable determining the oxygen profile into the overlying sediments. This third variable depends, amongst others, on the flow rate, length of path of the fluids in the basement, the amount of reducible compounds in the basin and basement temperature, whereby the latter two variables also depend on basement age (e.g. Coogan and Gillis 2018). Near sites where oxygen-rich seawater enters the basement, such as near larger seamounts, oxygen concentrations at the sediment–basement interface will be highest (e.g. Fisher et al., 2003). Since oxygen is consumed within the basement and diffuses from the basement into the sediment, further away from these sites of inflow, oxygen concentrations at the sediment–basement interface will be lower. The oxygen diffusion is not necessarily vertical only. For instance, 69SL is taken close to a ridge system with a steep slope, and sediment cover may be sufficiently thin (Fig. 1) to allow fluid venting from the basement into the ocean. As such, it is conceivable that lateral oxygen diffusion, perpendicular to this venting, contributes to the upward oxygen profile for 69SL, resulting in sediment columns in proximity to these venting systems that may be entirely oxic, possibly overruling the effect of sediment thickness.

Only core 58SL shows no downward decrease in its porewater Mn2+ profile. It was taken from the thickest sediment cover encountered like cores 65SL and 72SL, but in contrast to these two latter cores, there are no faults nearby. So, of all cores this one has the best prerequisites for having a suboxic zone that extends deep into the sediment. We therefore suppose that also for this location upward oxygen diffusion modifies the sediment, but we are not able to observe this since the porewater Mn2+ maximum and subsequent downward decrease are found below the depth of the retrieved sediments/bottom of the core.

4.2 Porewater nitrate

Usually in oxic sediments, nitrification of ammonium and diffusive loss of nitrate to the bottom water result in a nitrate maximum in the subsurface (Hensen et al., 2006). This was observed in our associated multicore data (not shown) in which values increase from 36 µmol L−1 at the sediment surface to reach maxima between 40 and 60 µmol L−1 at 10 to 50 cm depth, which agrees with earlier studies in the region (Mewes et al., 2014; Volz et al., 2018). The absence of such a subsurface nitrate maximum for all piston and gravity cores but 22KL and 35SL (Fig. 2) is explained by the loss of surface sediments as a result of the core recovery procedure. OM mineralisation slows down with increasing sediment depth, as does nitrate production. Furthermore, nitrate is diffusively lost to the overlying ocean bottom water (e.g. Hensen and Zabel, 2000; Hensen et al., 2006) and to the deeper sediment. The subsurface porewater nitrate maximum in the upper oxic zone of the cores reflects the balance between these three processes. For the entirely oxic cores, deeper in the sediment the linearly downward decreasing nitrate concentrations (Fig. 2) suggest the profiles to be driven by diffusion only, whereby nitrate is delivered to the basement fluid. Whereas the multicore tops indicate nitrate maximum concentrations of 35–40 µmol L−1 for ocean bottom waters (e.g. Hensen et al., 2006), extrapolation of the deeper linear nitrate profiles to the basement–sediment interface (from seismics; Kuhn et al., 2015) results in higher concentrations (43–48 µmol L−1) for the sediment–basement interface. These values differ at most by only 5 µmol L−1, suggesting the basement fluid has a relatively constant nitrate concentration. It also implies that the seismic-based estimates of sediment thicknesses must be relatively accurate. Since the bottom-water nitrate concentrations are lower than those in the basement fluids, we infer that there is a net flux of nitrate from the sediment to the basement. This stability of nitrate concentrations at the sediment–basement interface contrasts with the variability in inferred oxygen concentrations at this interface, suggesting very different dynamics such as a much stronger influence of processes in the basement on oxygen concentrations.

The cores with a suboxic zone (Fig. 3) have a more complex nitrate chemistry. From the nitrate maximum in the upper oxic zone well into the suboxic zone, the curvature of the profile becomes increasingly less (as also observed in some cores by, for example, Mewes et al., 2014; Mogollón et al., 2016 for this region), indicating a decreasing contribution of aerobic nitrification and suboxic heterotrophic nitrification with depth. Extrapolation of the nitrate profile of core 108SL down to the anticipated depth of the basement–sediment interface provides values estimated between 42 and 47 µmol L−1, which agrees with the values inferred from the entirely oxic cores. As such, the sediments represented by core 108SL are a source of nitrate for the basement fluid. For core 22KL, nitrate values reach below those inferred for the basement fluid. Here, the change from a gentle decrease to a linear increase at 9 m core depth in core 22KL marks the point where upward nitrate diffusion from the basement equals downward diffusion and nitrate consumption. Linear extrapolation of this downward increase provides 44 µmol L−1 for the basement–sediment interface, which again agrees well with the values estimated from the entirely oxic cores/sites. However, in contrast to the oxic cores and core 108SL, the sediments represented by 22KL are a sink for basement-fluid nitrate. For the remaining cores with a suboxic zone (9KL, 42SL, 58SL, 65SL and 72SL), denitrification is even more substantial, and minimum nitrate values always reach below those inferred for the basement fluid. We infer for the sediments below these cores a nitrate profile analogous to that seen in 22KL. However, whereas the nitrate minimum occurs within 22KL, we infer that these other cores did not reach sufficiently deep to include the nitrate minimum. From this minimum, (anticipated to be located below the maximum core depth), we infer a linear downward nitrate increase towards the basement, suggesting that the basement fluid represents a nitrate source.

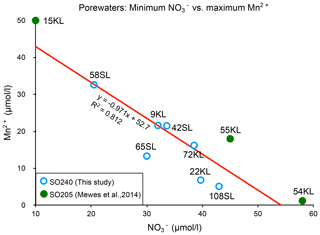

There appears to be a clear linear relationship between the minimum porewater nitrate concentration measured and the maximum porewater manganese concentration (Fig. 6), which roughly suggests that for each 1 µmol L−1 increase in manganese, nitrate decreases by also 1 µmol L−1, and this suggests a coupling between the manganese and nitrate cycles. The ratio is very different from the manganese-mediated denitrification in which 2.5 manganese are needed to consume 1 nitrate to produce 0.5 nitrogen molecules (e.g. Mogollón et al., 2016). We note that such an opposite relation can be induced by two processes: (1) oxidation by O2 increases (from ) and decreases Mn2+ (producing MnO2), whereas (2) OM degradation consumes (producing ) and produces Mn2+ (from MnO2) (see, for example, Mogollón et al., 2016). Apparently, the long-term dynamic equilibria between these processes result in the observed net relation between the minimum porewater nitrate concentration measured and the maximum porewater manganese concentration in the sediments of this region.

Figure 6Relationship between maximum Mn2+ and minimum concentrations for the cores with a suboxic zone.

Thus, we observe that some sediments deliver nitrate to the basement, whereas others take up nitrate from the basement. We also observe that the inferred nitrate values in the basaltic basement are higher than those in the ocean bottom waters, which implies that after entering the basement, the basement fluids get enriched in nitrate. We infer, therefore, that overall, the nitrate uptake from the basement by the sediment is less than the nitrate delivery to the basement by the sediment so that the basement gets enriched in nitrate relative to the ocean bottom waters. This nitrate enrichment can also be observed for the Cocos Ridge (Wheat and Fisher, 2008) and North Pond, Mid-Atlantic Ridge (Wankel et al., 2015; Wheat et al., 2020).

For the nitrate profiles in marine sediments there seem to be three situations. In the more eutrophic ocean and coastal margins, sediments get suboxic at shallow sediment depths, and in the suboxic zone nitrate is completely removed from the sediment by denitrification (e.g. Froelich et al., 1979). As nitrate is absent from the deeper sediment, a flux of nitrate will occur from the basaltic basement upwards into the sediment where it gets consumed. Towards increasingly oligotrophic conditions and lower sedimentation rates, oxygen can diffuse deeper into the sediment, and the depth at which nitrate is completely consumed increases as well, e.g. core SPG-12 just outside the South Pacific Gyre (SPG) (D'Hondt et al., 2009), IODP 329 Site U1371 (D'hondt et al., 2015) and western North Atlantic KN223 Site 10 (Buchwald et al., 2018).

A second situation occurs in which nitrate remains present throughout the sediment. It seems that this situation occurs with further decreasing productivity and/or sedimentation rate and denitrification in the suboxic zone such that it is insufficient to create a zone without nitrate. This occurs at, for example, the Dorado Outcrop on the East Pacific Rise (Wheat et al., 2019). Here, manganese reduction starts when nitrate falls below 10–20 µmol kg−1 . In such cases, the redox succession probably remains suboxic with manganese reduction and does not enter the zone of iron reduction. In the CCZ cores we observe a negative linear 1:1 relation between nitrate and porewater manganese concentrations (Fig. 6). In the East Pacific Rise (Wheat et al., 2019) dissolved manganese appears if nitrate falls below 25 µmol kg−1, and nitrate becomes depleted if porewater manganese is near 70 µmol kg−1. As a consequence every 1 µmol increase in nitrate results in a 2.8 µmol decrease in porewater manganese. As long as sedimentary nitrate remains below the values in the basaltic basement, nitrate diffuses from this basement into the sediment, a situation we observe for most of our sediments with a suboxic zone. However, as maximum dissolved manganese concentrations decrease, minimum nitrate concentrations increase, and eventually nitrate concentrations stay higher in the sediment than in the basaltic basement, establishing a net nitrate flux from the sediment into the fluid circulating in the underlying basaltic basement. This is the case at site108SL and also occurs at IODP 329 Site U1370 at the edge of the SPG (D'Hondt et al., 2015).

A third situation evolves if the sediments become entirely oxic. The zone with dissolved manganese disappears and denitrification ceases. In the CCZ, we find for this situation nitrate concentrations up to 52 µmol L−1. Mewes et al. (2014) found a slightly higher threshold of 60 µmol L−1 (Fig. 6, green dots). In all these cases, sediments are a nitrate source to the basaltic basement. This is also observed at North Pond, western flank of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, at IODP 336 sites U1382B, U1383D and U1384 A (Wankel et al., 2015). In the latter study maximum nitrate concentrations increase with decreasing denitrification rates. Towards the even more oligotrophic conditions, such as towards the centre of the SPG, sedimentation rates decrease, and the minimum oxygen concentrations increase. We infer that towards such increasingly carbon-poor settings maximum sedimentary nitrate concentrations decrease as well and so does the nitrate flux to the basaltic basement. This situation is encountered in the SPG: cores SPG 1–11 (D'Hondt et al., 2009) and IODP 329 SPG sites U1365–U1369 (D'hondt et al., 2015) where maximum concentrations decrease towards the SPG centre.

On a global scale, from the eutrophic continental margins and upwelling zones towards the highly oligotrophic central ocean gyres, export production and sedimentation rate decrease, and oxygen penetration into the sediments (from above and below) increases. As a result of nitrification in the upper sediment, there is always a net flux of nitrate from the sediment to the bottom waters and further down into the sediment. However, nitrate exchange with the basement varies. In more eutrophic sediments, denitrification is so extensive that nitrate concentrations deeper in the sediment are lower than in the basaltic basement, and – as a consequence – the basement delivers nitrate to the sediment. However, towards the centre of the gyres (more oligotrophic settings), denitrification rates decrease, and nitrate becomes present throughout the sediment. If denitrification in the suboxic zone further declines, minimum nitrate levels eventually exceed those in the basaltic basement, and a net flux of nitrate into this basement is induced. Eventually, also the suboxic zone disappears, denitrification ceases, and the sediments become entirely oxic. Towards even more oligotrophic settings, maximum nitrate levels in the sediments decrease and so does the nitrate flux from the sediment to the basaltic basement.

4.3 Porewater manganese and iron

While in sediments with sufficient reactive OM the manganese reduction zone is followed by iron reduction, there is no evidence of this latter process in the sediments investigated in the framework of this study – i.e. the abundance of electron donors in the form of OM is too low to induce Fe reduction. In all cases when dissolved manganese is present in the porewater, we observe a maximum followed by a decrease with depth (Fig. 3). However, in those cases where we can follow this decrease further to zero, it is followed by oxic sediments and not by free iron. Consequently, we infer that in the complete region of this study insufficient reductive power is available to induce iron reduction. This has also been observed for the North Pond at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge where only hole 1382B shows porewater-dissolved manganese but no free/dissolved Fe2+ (see Interstitial water for IODP expedition 336 at https://web.iodp.tamu.edu/LORE/?appl=LORE&reportName = iw, last access: 30 August 2021).

4.4 Nickel and cobalt in porewater and solid phase

Both porewater and solid-phase nickel and cobalt in the suboxic cores tend to behave similar to manganese (Fig. 4), which agrees with the assumption that both metals are preferentially associated with the redox cycling of Mn (Aplin and Cronan, 1985; Koschinsky et al., 2001). In the suboxic zone, Mn oxide reduction also releases dissolved Ni2+ and Co2+ into the porewater. Especially cobalt behaves similar to manganese, both clearly showing the transition zone between the upper oxic zone and the suboxic zone (upper front). We call this a transition zone since these elements are still present in the porewater but already show elevated solid-phase contents. Nickel is much less bound to the oxidation fronts and seems to remain more mobile in the porewaters at higher oxygen levels than is the case for manganese and cobalt. The reason for this may be oxidation of porewater Co2+ to Co3+ when bound to the Mn oxide phase in the sediment, which is a much more efficient scavenging process compared to simple adsorption, such as for Ni2+ (Murray and Dillard, 1979). Experiments with manganese-oxide-rich sediments also showed that the bonding of Ni is on average weaker and more easily reversible than for Co, and oxidation of Co during sorption on Mn oxides was confirmed (Kay et al., 2001).

4.5 Stability of the upper and lower redox fronts

The absence of a transition zone for cobalt and manganese between the suboxic zone and the lower oxic zone (lower front) illustrates that the upper front is much more dynamic than the lower front. The lower front is the result of a very long route of oxygen transport from the ocean into and through the basement. As such, changes in ocean water oxygen arrive at the lower front delayed and with lower amplitude and as a consequence of the oxidation of reduced mineral phases in the crust also with lower concentrations. As a result, the lower front is much more stable and probably foremost moves slowly but steadily upward, oxidising the OM residue left behind when the upper front moved upwards with ongoing sedimentation.

4.6 Different aspects of the top and bottom redox zonations

Considering the above, we may add geochemical details to the conceptual model of low-temperature circulation of seawater/fluids and their components through ocean crust and diffusive exchange with overlying sediments that was presented by Fisher and Wheat (2010; Fig. 7) and schematically visualise the observed diagenetic profiles for sediments taking up nitrate from the basement (Fig. 8). The classical model of a succession of redox zones from the ocean floor into the sediment has to be extended by adding a similar reversed zonation scheme from the basement–sediment interface into the sediment for those regions where basement fluids are oxic. However, there are some marked differences between the redox succession from the sediment surface downwards and that from the basement and lower/overlying sediments upwards.

Figure 7Model of fluid circulation in the basaltic basement, diffusive exchange with the sediment and the sediment oxidation state. Note the influence of faults. Representative cores taken during SO240 are placed such that their geochemical profiles match with the model (modified from Fisher and Wheat, 2010).

Figure 8Conceptual model summarising the diagenetic processes discussed in this paper as a result of oxygen entering the sediment from the ocean bottom waters and from the oceanic basement. Left panel: porewater profiles. Right panel: solid fraction. Numbers refer to concentrations in micromoles per litre . The model is based on the profiles of inorganic species and TOC in core.

At the sediment surface the OM is fresh, highly reactive and subject to aerobic degradation first (Mewes et al., 2014; Mogollón et al., 2016; Volz et al., 2018). With ongoing sedimentation and concurrent upward movement of the oxic zone, progressively less energetically favourable redox processes follow. Generally, in such situations, the reaction time is often too short for a given redox process to consume all available substrate. Reduced species that cannot be oxidised by the next, energetically less favourable redox pair will remain, resulting in a surplus of reduced material that becomes fossilised at depth.

In contrast to this, oxygen penetrating from the basement into the sediment encounters the oldest sediment first. Compared to the sediment surface, reaction time is long and at the basalt–sediment interface aerobic conditions may have prevailed since the onset of sedimentation. Here, oxygen exposure time is not limiting the degree to which the substrate (OM) can be oxidised but the reactivity of the substrate. From the basement, the successively energetically less favourable redox zones follow each other upward so that at a particular depth, with time, progressively stronger oxidants may be expected, each consuming the fossilised reduced species (such as OM) that were left by the upwards migrating redox zones near the sediment surface. It should be noted that the fossilisation process may have changed the reactivity and degradability of the fossilised species over time (e.g. in sediments where sulfate reduction occurs; however, not in our sediments), natural sulfurisation may have cross-linked residual organic matter reducing its degradability by microorganisms (Zonneveld et al., 2010). The order of redox processes upwards thus mirrors that from the sediment–water interface downwards. However, in this lower oxic zone (from the basement upwards), oxidation times are long so that only the most refractory components remain. As such, reaction rates should be negligible so that the oxygen profile will approach linearity up to the lower oxic–suboxic interface above. Thus, the front position is primarily a balance between the downward migration/burial of oxidisable species and upward oxygen flux from the basement. This is what we observe at site 22KL. Here, the downward-directed profile of Mn, Co, Ni and other reduced species become linear already in the suboxic zone and meet a counter-directed linear upward oxygen diffusion profile (Fig. 8). If oxygen supply from below increases, the oxygen flux from below may meet the upper oxic zone. Thus, in the CCZ, the entirely oxic cores display a configuration where the balance between supply of reduced species to the sediment, oxygen supply and sedimentation rate is such that a suboxic zone is absent as is a pool of reduced fossilised material. Here, the upward oxygen flux meets the downward flux at the point of no flux. The lower profile contributes here to the aerobic degradation at the lower end of the upper profile.

If in such entirely oxic sediments the upward oxygen flux becomes less, the oxygen minimum and the downward-directed oxygen diffusion will extend downward and on its way will meet sediments with progressively increasing oxygen exposure time. Where reaction rates become very low, this downward profile will become quasi-linear. Despite very low oxygen consumption in such sediments, if they are sufficiently thick, the system may become suboxic eventually. Since this suboxic zone is formed where previously the oxygen from below had exhaustively removed electron donors, manganese re-mobilisation may be very slow relative to diffusion, or even absent due to lack of electron donors and thus, we expect to encounter a suboxic sediment where porewater manganese is undetectable, a situation that may apply to core 81SL (Fig. 2).

The widespread interaction between basement fluid and the overlying sediment through diffusion of dissolved substances adds an important dynamic component to the geochemical interaction of sediment, basement and deep ocean (as compared to direct exchange between the surface sediment and the ocean bottom waters). The deep oligotrophic and fully oxidised ocean sediments possibly account for 30 %–50 % of the ocean floor (D'Hondt et al., 2015). Most of the rest of the deep ocean is covered by sediments with oxic surface sediments and probably also oxic bottom sediments. All these sediments collect oxidised substances and store them for long periods of time. Fluid circulation through the basaltic basement increases the exchange between sediment and the bottom water and thus the buffer capacity.

Analyses of the concentrations of oxygen, nitrate, manganese, nickel and cobalt in porewaters and the solid-phase of sediments from the CCZ were summarised in a conceptual graph (Fig. 8) and show the following:

-

An upper oxygen profile of relatively constant length (2–3 m) results from oxygen penetrating the sediments from the ocean bottom water downwards, and a lower oxygen profile of variable length results from oxygen penetrating from the basement upwards.

-

Where the upper and lower oxygen profiles meet, sediments are entirely oxic, and organic carbon mineralisation is very low. In the absence of denitrification, nitrate produced in the sediment diffuses into the ocean bottom water and basement fluid.

-

Where the upper and lower oxygen profiles do not meet, they are separated by an intermediate suboxic zone with free porewater manganese and cobalt. Here denitrification continues and in some cases may be in excess of nitrate production so that the basement fluid delivers nitrate to the sediment.

-

The inferred nitrate concentrations at the basement–sediment interface are relatively constant (43–48 µmol L−1) and higher than in the ocean bottom waters so that in the sampled region overall more nitrate goes from the sediment to the basement than vice versa.

-

The behaviour of the upper and lower oxic–suboxic transitions is very different. The upper oxic–suboxic redox boundary is at the end of a curved oxygen profile. The redox boundary moves up with sedimentation, leaving unoxidised OM behind in the manganese reduction zone below. Moreover, due to the relatively short distance between bottom water and the front, the position of the upper front is sensitive to changes in bottom water oxygen content and as such is relatively unstable. The lower oxic–suboxic redox boundary is at the end of a linear oxygen profile, and it moves up as a result of lacking (sufficiently labile) oxidisable material further down. It leaves behind an “energetic desert” without further oxidation potential. The long transport route of bottom water oxygen, via basement fluid (advection) into the sediment and to the lower oxic–suboxic transition (diffusion), strongly buffers the amplitude and frequency of changes in oxygen content so that the lower transition is much more stable than the upper front.

-

Over time, manganese, nickel and cobalt diffuse from the suboxic zone to the upper and lower redox fronts/transitions where they are oxidised and precipitate. At the upper transition they add to the manganese, cobalt and nickel that were deposited by sedimentation. With this transition moving upward with sedimentation, these elements re-enter the suboxic zone, remobilise and move up to the oxic–suboxic transition again, leading to a continuous increasing in solid-phase contents of these elements near the redox front. With the lower transition moving upwards, these elements remain fixed in the oxidised sediment below, resulting in the permanent loss of these elements from the suboxic zone.

-

Since in the region between the Clarion and Clipperton fracture zones sediment cover is generally thin and sedimentation rates are generally low, we are mostly able to observe the upper oxygen profile and accompanying redox zone, as well as in reverse the lower redox zone and oxygen profile, each with its associated set of phenomena such as nitrate diffusion into the basement fluid. In many other ocean regions sediments are thicker and productivity higher, so the lower oxygen profile will be below the reach of the gravity or piston coring device due to a more complete redox zonation reaching deeper into the sediment, and drilling is needed to reach the successive redox zones, as well as the reversed redox zonation followed by the deep oxygen profile to the basement (provided sufficient oxygen is provided by the basement). We are just beginning to understand the impact of this deep redox zonation on the biogeochemical cycles of carbon and nitrogen, as well as the distribution of carbon and other elements (such as manganese and associated metals such as nickel and cobalt and, in organically richer sediments, iron and sulfur) in the deep sediments. Fortunately, deep drilling (e.g. through international consortia like DSDP, ODP and IODP) logistically and financially enable access to these deeper sediments to investigate to what extent theories and hypotheses erected on the basis of shallower settings are applicable for the majority of the ocean floor. Considering the potential area involved this warrants a substantial research effort.

-

The vast amount of oxygen and oxidised materials in sediments below the oligotrophic ocean buffers the redox environment of the ocean bottom waters. Fluid circulation through the basaltic basement increases the exchange between sediment and the bottom water and thus the buffer capacity. Our study has pointed out that not only do diffusive fluxes in the top part of deep-sea sediments modify the geochemical composition over time but also diffusive transfer from basement fluids into the bottom layers of the sediment, and vice versa. Hence, the palaeoceanographic interpretation of sedimentary archives should carefully consider such secondary modifications and adjust rates of (bio-)geochemical processes in order to prevent the misinterpretation of primary signatures.

Data are available at https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.933062 (Versteegh et al., 2021).

GJMV interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. IP carried out the porewater analyses, and TK performed the solid-phase analyses. SK and AK, together with TK, designed and supervised the project. All authors discussed data and contributed to the manuscript at different stages.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank captain Lutz Mallon and his crew for the excellent co-operation and the pleasant atmosphere during RV Sonne cruise SO240. We also appreciate the enthusiasm and engagement of the scientific participants of the expedition. We thank the reviewers Geoff Wheat and Beth Orcutt for their detailed and constructive reviews. The working areas are within the area contracted by the International Seabed Authority to the German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources for exploration of polymetallic nodules.

This research has been supported by the German Federal Ministry

for Education and Science (grant no. 03G0240A-C) and the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR) (grant no. A-0203002.A). This study received further financial support from the Helmholtz Association (Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research).

The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI).

This paper was edited by Tina Treude and reviewed by Geoff Wheat and Beth Orcutt.

Anderson, R. N., Hobart, M. A., and Langseth, M. G.: Geothermal convection through oceanic crust and sediments in the Indian Ocean, Science, 204, 828–832, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.204.4395.828, 1979.

Aplin, A. C. and Cronan, D. S.: Ferromanganese oxide deposits from the Central Pacific Ocean, II. Nodules and associated sediments, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 49, 437–451, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(85)90035-3, 1985.

Arnarson, T. S. and Keil, R. G.: Changes in organic matter–mineral interactions for marine sediments with varying oxygen exposure times, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 71, 3545–3556, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2007.04.027, 2007.

Arndt, S., Jørgensen, B. B., LaRowe, D. E., Middelburg, J. J., Pancost, R. D., and Regnier, R.: Quantifying the degradation of organic matter in marine sediments: A review and synthesis, Earth-Sci. Rev., 123, 53–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.02.008, 2013.

Baker, P. A., Stout, P. M., Kastner, M., and Elderfield, H.: Large-scale lateral advection of seawater through oceanic crust in the central equatorial Pacific, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 105, 522–533, https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-821X(91)90189-O, 1991.

Barckhausen, U., Bagge, M., and Wilson, D. S.: Seafloor spreading anomalies and crustal ages of the Clarion–Clipperton Zone, Mar. Geophys. Res., 34, 79–88, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11001-013-9184-6, 2013.

Berner, R. A.: Early Diagenesis. A Theoretical Approach, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1980.

Bowles, M. W., Mogollón, J. M., Kasten, S., Zabel, M., and Hinrichs, K.–U.: Global rates of marine sulfate reduction and implications for sub–sea–floor metabolic activities, Science, 344, 889–891, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1249213, 2014.

Buchwald, C., Homola, K., Spivack, A. J., Estes, E. R., Murray, R. W., and Wankel, S. D.: Isotopic constraints on nitrogen transformation rates in the deep sedimentary marine biosphere, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 32, 1688–1702, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GB005948, 2018.

Cai, W.-J. and Sayles, F. L.: Oxygen penetration depths and fluxes in marine sediments, Mar. Chem., 52, 123–131, https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4203(95)00081-X, 1996.

Canfield, D. E. and Thamdrup, B.: Towards a consistent classification scheme for geochemical environments, or, why we wish the term “suboxic” would go away, Geobiology, 7, 385–392, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4669.2009.00214.x, 2009.

Coogan, L. A. and Gillis, K. M.: Low–Temperature Alteration of the Seafloor: Impacts on Ocean Chemistry, Annu. Rev. Earth Pl. Sc., 46, 21–45, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-082517-010027, 2018.

D'Hondt, S., Spivack, A. J., Pockalny, R., Ferdelman, T. G., Fischer, J. P., Kallmeyer, J., Abrams, L. J., Smith, D. C., Graham, D., Hasiuk, F., Schrum, H., and Stancin, A. M.: Subseafloor sedimentary life in the South Pacific Gyre, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 11651–11656, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0811793106, 2009.

D'Hondt, S., Inagaki, F., Alvarez Zarikian, C., and the IODP Expedition 329 Scientific Party: IODP Expedition 329: Life and Habitability Beneath the Seafloor of the South Pacific Gyre, Sci. Dril., 15, 4–10, https://doi.org/10.2204/iodp.sd.15.01.2013, 2013.

D'Hondt, S., Inagaki, F., Zarikian, C. A., Abrams, L. J., Dubois, N., Engelhardt, T., Evans, H., Ferdelman, T., Gribsholt, B., Harris, R. N., Hoppie, B., Hyun, J.-H., Kallmeyer, J., Kim, J., Lynch, J. E., McKinley, C., Mitsunobu, S., Morono, Y., Murray, R. W., Pockalny, R., Sauvage, J., Shimono, T., Shiraishi, F., Smith, D., C. Smith–Duque, C., Spivack, A. J., Steinsbu, B. O., Suzuki, Y., Szpak, M., Toffin, L., Uramoto, G., Yamaguchi, Y. T., Zhang, G.-L., Zhang, X.-H., and Ziebis, W.: Presence of oxygen and aerobic communities from sea floor to basement in deep-sea sediments, Nat. Geosci., 8, 299–304, https://doi.org/10.1038/NGEO2387, 2015.

D'Hondt, S., Inagaki, F., Orcutt, B. N., and Hinrichs K.-U.: IODP advances in the understanding of subseafloor life, Oceanography, 32, 198–207, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11450-z, 2019a.

D'Hondt, S., Pockalny, R., Fulfer, V. M., and Spivack, A. J.: Subseafloor life and ist biogeochemical impacts, Nat. Commun., 10, 3519, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11450-z, 2019b.

Davis, E. E., Chapman, D. S., Wang, K., Villinger, H., Fisher, A. T., Robinson, S. W., Grigel, J., Pribnow, D., Stein, J., and Becker, K.: Regional heat flow variations across the sedimented Juan de Fuca Ridge eastern flank: Constraints on lithospheric cooling and lateral hydrothermal heat transport, J. Geophys. Res.–Atmos., 104, 17675–17688, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JB900124, 1999.

de Lange, G. J.: Geochemical evidence of a massive slide in the southern Norwegian Sea, Nature, 305, 420–422, https://doi.org/10.1038/305420a0, 1983.

Eittreim, S. L., Ragozin, N., Gnibidenko, H. S., and Helsley, C. E.: Crustal age between the Clipperton and Clarion Fracture Zones, Geophys. Res. Lett., 19, 2365–2368, https://doi.org/10.1029/92GL02928, 1992.

Emerson, S. and Hedges, J.: Sediment diagenesis and benthic flux, in: Treatise on Geochemistry, vol. 6, Holland, H. D. and Turekian, K. K. (Eds.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 293–319, https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043751-6/06112-0, 2003.

Fischer, J. P., Ferdelman, T. G., D'Hondt, S., Røy, H., and Wenzhöfer, F.: Oxygen penetration deep into the sediment of the South Pacific gyre, Biogeosciences, 6, 1467–1478, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-6-1467-2009, 2009.

Fisher, A. T. and Wheat, C. G.: Seamounts as conduits for massive fluid, heat, and solute fluxes on ridge flanks, Oceanography, 23, 74–87, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2010.63, 2010.

Fisher, A. T., Davis, E. E., Hutnak, M., Spiess, V., Zühlsdorff, L., Cherkaoui, A., Christiansen, L., Edwards, K., Macdonald, R., Villinger, H., Mottl, M. J., Wheat, C. G., and Becker, K.: Hydrothermal recharge and discharge across 50 km guided by seamounts on a young ridge flank, Nature, 421, 618–621, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01352, 2003.

Froelich, P. N., Klinkhammer, G. P., Bender, M. L., Luedtke, N. A., Heath, G. R., Cullen, D., Dauphin, P., Hammond, D., Hartman, B., and Maynard, V.: Early oxidation of organic matter in pelagic sediments of the eastern equatorial Atlantic: suboxic diagenesis, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 43, 1075–1090, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(79)90095-4, 1979.

García, H. E. and Gordon, L. I.: Oxygen solubility in seawater: Better fitting equations, Limnol. Oceanogr., 37, 1307–1312, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1992.37.6.1307, 1992.

Garcia, H. E., Weathers, K., Paver, C. R., Smolyar, I., Boyer, T. P., Locarnini, R. A., Zweng, M. M., Mishonov, A. V., Baranova, O. K., Seidov, D., and Reagan, J. R.: World Ocean Atlas 2018, Volume 4: Dissolved Inorganic Nutrients (phosphate, nitrate and nitrate+nitrite, silicate), Mishonov, A. (Technical Ed.), NOAA Atlas NESDIS 84, Silver Spring, MD, 35 pp., 2018.

Hasterok, D., Chapman, D. S., and Davis, E. E.: Oceanic heat flow: Implications for global heat loss, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 311, 386–395, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2011.09.044, 2011.

Hensen, C., Zabel, M., and Schulz, H. D.: A comparison of benthic nutrient fluxes from deep-sea sediments off Namibia and Argentinia, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 47, 2029–2050, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0645(00)00015-1, 2000.

Hensen, C., Zabel, M., and Schulz, H. N.: Early Diagenesis at the Benthic Boundary Layer: Oxygen, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus in Marine Sediments, in: Marine Geochemistry, Schulz, H. D. and Zabel, M. (Eds.), Springer, Heidelberg, pp. 207–240, https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-32144-6_6, 2006.

Hulme, S. M. and Wheat C. G.: Subseefloor fluid and chemical fluxes along a buried-basement ridge on the eastern flank of the Juan de Fuca Ridge, Geochem. Geophy. Geosy., 20, 4922–4938, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GC008408, 2019.

Hutnak, M., Fisher, A. T., Zühlsdorff, L., Spiess, V., Stauffer, P. H., and Gable, C. W.: Hydrothermal recharge and discharge guided by basement outcrops on 0.7–3.6 Ma seafloor east of the Juan de Fuca Ridge: Observations and numerical models, Geochem. Geophy. Geosy., 7, Q07O02, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GC001242, 2006.

Kasten, S., Zabel, M., Heuer, V., and Hensen, C.: Processes and signals of non–steady state diagenesis in deep-sea sediments, in: The South Atlantic in the Late Quaternary, Wefer, G., Mulitza, S., and Rathmeyer, V. (Eds.), Springer, Berlin, pp. 431–459, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-18917-3_20, 2003.

Kay, J., Conklin, M. H., Fuller, Christopher C, and O'Day, P. A.: Processes of nickel and cobalt uptake by a manganese oxide forming sediment in Pinal Creek, Globe Mining District, Arizona, Environ. Sci. Technol., 35, 4719–4725, https://doi.org/10.1021/es010514d, 2001.

Koschinsky, A., Fritsche, U., and Winkler, A.: Sequential leaching of Peru Basin surface sediment for the assessment of aged and fresh heavy metal associations and mobility, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 48, 3683–3699, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0645(01)00062-5, 2001.

Kuhn, T., Bösel, J., Dohrmann, I., Filsmair, C., Fronzek, J., Gerken, J., Goergens, R., Hartmann, J. F., Heesemann, B., Heller, C., Heyde, I., Janssen, A., Kasten, S., Kaul, N., Kevel, O., Kleint, C., Lückge, A., Müller, P., Preuss, I.-M., Purkiani, K., Ritter, S., Rühlemann, C., Schwab, A., Sing, R., Stegger, U., Sturm, S., Uhlenkott, K., Villinger, H., Vink, A., Wedemeyer, H., and Wegorzewski, A.: SO240 – Flum: Low–temperature fluid circulation at seamounts and hydrothermal pits: heat flow regime, impact on biogeochemical processes and its potential influence on the occurrence and composition of manganese nodules in the equatorial eastern Pacific, 1–185, Bundesanstalt für Geologie und Rohstoffe (BGR), https://doi.org/10.2312/cr_so240, 2015.

Kuhn, T., Versteegh, G. J. M., Villinger, H., Dohrmann, I., Heller, C., Koschinsky, A., Kaul, N., Ritter, S., Wegorzewski, A. V., and Kasten, S.: Widespread sea–water circulation in 18–22 Ma oceanic crust: Impact on heat flow and sediment geochemistry, Geology, 45, 799–802, https://doi.org/10.1130/G39091.1, 2017.

Lutz, M. J., Caldeira, K., Dunbar, R. B., and Behrenfeld, M. J.: Seasonal rhythms of net primary production and particulate organic carbon flux describe the biological pump efficiency in the global ocean, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 112, C10011, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JC003706, 2007.

Mewes, K., Mogollón, J. M., Picard, A., Rühlemann, C., Kuhn, T., Nöthen, K., and Kasten, S.: Impact of depositional and biogeochemical processes on small scale variations in nodule abundance in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I, 91, 125–141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2014.06.001, 2014.

Mewes, K., Mogollón, J. M., Picard, A., Rühlemann, C., Eisenhauer, A., Kuhn, T., Ziebis, W., and Kasten, S.: Diffusive transfer of oxygen from seamount basaltic crust into overlying sediments: An example from the Clarion–Clipperton Fracture Zone, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 433, 215–225, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2015.10.028, 2016.

Mogollón, J. M., Mewes, K., and Kasten, S.: Quantifying manganese and nitrogen cycle coupling in manganese–rich, organic carbon–starved marine sediments: Examples from the Clarion–Clipperton fracture zone, Geophys. Res. Lett., 43, 7114–7123, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016gl069117, 2016.

Morono, Y., Ito, M., Hoshino, T., Terada, T., Hori, T., Ikehara, M., D'Hondt, S., and Inagaki, F.: Aerobic microbial life persists in oxic marine sediment as old as 101.5 million years, Nat. Commun., 11, 3626, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17330-1, 2020.

Müller, P. J. and Mangini, A.: Organic carbon decomposition rates in sediments of the pacific manganese nodule belt dated by 230Th and 231Pa, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 51, 94–114, https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-821X(80)90259-9, 1980.

Murray, J. W. and Dillard, J. G.: The oxidation of cobalt(II) adsorbed on manganese dioxide, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 43, 781–787, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(79)90261-8, 1979.

Nöthen, K. and Kasten, S.: Reconstructing changes in seep activity by means of pore water and solid phase SrCa and MgCa ratios in pockmark sediments of the Northern Congo Fan, Mar. Geol., 287, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2011.06.008, 2011.

Orcutt, B. N., Wheat, C. G., Rouxel, O., Hulme, S., Edwards, K. J., and Bach, W.: Oxygen consumption rates in subseafloor basaltic crust derived from a reaction transport model, Nat. Commun., 4, 2539, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3539, 2013.

Rietveld, H. M.: Line profiles of neutron powder-diffraction peaks for structure refinement, Acta Crystallogr., 22, 151–152, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0365110X67000234, 1967.

Revsbech, N. P.: An oxygen microsensor with a guard cathode, Limnol. Oceanogr., 34, 474–478, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1989.34.2.0474, 1989.

Rühlemann, C., Kuhn, T., Wiedicke, M., Kasten, S., Mewes, K., and Picard, A.: Current status of manganese nodule exploration in the German license area, Proceedings of the Ninth (2911) ISOPE Ocean Mining Symposium, Maui, Hawaii, USA, 19–24 June, 168–173, 2011.

Sclater, J. G., Jaupart, C., and Galson, D.: The heat flow through oceanic and continental crust and the heat loss of the Earth, Rev. Geophys., 18, 269–311, https://doi.org/10.1029/RG018i001p00269, 1980.

Seeberg–Elverfeldt, J., Schlüter, M., Feseker, T., and Kölling, M.: Rhizon sampling of porewaters near the sediment-water interface of aquatic systems, Limnol. Oceanogr.-Meth., 3, 361–371, https://doi.org/10.4319/lom.2005.3.361, 2005.

Spinelli, G. A., Giambalvo, E. R., and Fisher, A. T.: Sediment permeability, distribution, and influence on fluxes in oceanic basement. in: Hydrogeology of the oceanic lithosphere, Davis, E. E. and Elderfield, H. (Eds.), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 151–188, 2004.

Stein, C. A. and Stein, S.: A model for the global variation in oceanic depth and heat flow with lithospheric age, Nature, 359, 123–129, https://doi.org/10.1038/359123a0, 1992.

Tegelaar, E. W., de Leeuw, J. W., Derenne, S., and Largeau, C.: A reappraisal of kerogen formation, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 53, 3103–3106, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(89)90191-9, 1989.

Versteegh, G. J. M., Koschinsky, A., Kuhn, T., Preuss, I., and Kasten, S.: Porewater and solid phase Mn, Ni, Co and porewater O2 and NO3 from the Clarion-Clipperton Zone NE Pacific, PANGAEA [data set], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.933062, 2021.

Volz, J. B., Mogollón, J. M., Geibert, W., Martínez Arbizu, P., Koschinsky, A., and Kasten, S.: Natural spatial variability of depositional conditions, biogeochemical processes and element fluxes in sediments of the eastern Clarion–Clipperton Zone, Pacific Ocean, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I, 140, 159–172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2018.08.006, 2018.

Volz, J. B., Liu, B., Köster, M., Henkel, S., Koschinsky, A., and Kasten, S.: Post-depositional manganese mobilization during the last glacial period in sediments of the eastern Clarion-Clipperton Zone, Pacific Ocean, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 532, 116012, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2019.116012, 2020.

Wankel, S. D., Buchwald, C., Ziebis, W., Wenk, C. B., and Lehmann, M. F.: Nitrogen cycling in the deep sedimentary biosphere: nitrate isotopes in porewaters underlying the oligotrophic North Atlantic, Biogeosciences, 12, 7483–7502, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-12-7483-2015, 2015.

Wenzhöfer, F. and Gludd, R. N.: Benthic carbon mineralization in the Atlantic: a synthesis based on in situ data from the last decade, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I, 49, 1255–1279, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0637(02)00025-0, 2002.