the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Implementation of mycorrhizal mechanisms into soil carbon model improves the prediction of long-term processes of plant litter decomposition

Weilin Huang

Peter M. van Bodegom

Toni Viskari

Jari Liski

Nadejda A. Soudzilovskaia

Ecosystems have distinct soil carbon dynamics, including litter decomposition, depending on whether they are dominated by plants featuring ectomycorrhizae (EM) or arbuscular mycorrhizae (AM). However, current soil carbon models treat mycorrhizal impacts on the processes of soil carbon transformation as a black box.

We re-formulated the soil carbon model Yasso15 and incorporated impacts of mycorrhizal vegetation on topsoil carbon pools of different recalcitrance. We examined alternative conceptualizations of mycorrhizal impacts on transformations of labile and stable carbon and quantitatively assessed the performance of the selected optimal model in terms of the long-term fate of plant litter 10 years following litter input.

We found that mycorrhizal impacts on labile carbon pools are distinct from those on recalcitrant pools. Plant litter of the same chemical composition decomposes slower when exposed to EM-dominated ecosystems compared to AM-dominated ones, and across time, EM-dominated ecosystems accumulate more recalcitrant residues of non-decomposed litter. Overall, adding our mycorrhizal module into the Yasso model improved the accuracy of the temporal dynamics of carbon sequestration predictions.

Our results suggest that mycorrhizal impacts on litter decomposition are underpinned by distinct decomposition pathways in AM- and EM-dominated ecosystems. A sensitivity analysis of litter decomposition to climate and mycorrhizal factors indicated that ignoring the mycorrhizal impact on decomposition leads to an overestimation of climate impacts on decomposition dynamics. Our new model provides a benchmark for quantitative modelling of microbial impacts on soil carbon dynamics. It helps to determine the relative importance of mycorrhizal associations and climate on litter decomposition rate and reduces the uncertainties in estimating soil carbon sequestration.

- Article

(6711 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(624 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Long-term soil carbon (C) sequestration is to a large extent determined by complex soil–plant rhizosphere and microbial interactions (Dijkstra and Cheng, 2007; Fernandez and Kennedy, 2016; Fontaine et al., 2007; Ostle et al., 2009). These interactions contribute to the atmospheric CO2 balance (Ostle et al., 2009; Todd-Brown et al., 2012) and are increasingly recognized as processes that counteract climate change (Terrer et al., 2016). Plant associations with fungi, so-called mycorrhizas, are the most widespread symbiosis on Earth, featured by the majority of vascular plants including trees, shrubs, and herbs (Brundrett and Tedersoo, 2018). Mycorrhizae are hypothesized to play especially important roles in soil C sequestration, yet the actual mechanisms of mycorrhizal impacts on soil C dynamics are poorly understood.

Mycorrhizal fungi themselves are not capable of meaningfully obtaining carbon from decomposing plant litter (Bödeker et al., 2016; Lindahl and Tunlid, 2015). Instead, they receive carbon from their symbiotic host plants. However, the relation between mycorrhizal fungi and soil C dynamics is enabled through three potential pathways that likely complement each other (Frey, 2019): (i) provisioning of substrate for decomposition (Leake et al., 2004; Soudzilovskaia et al., 2015), (ii) mediating plant litter quality and amounts (Averill et al., 2019; Cornelissen et al., 2001; Phillips et al., 2013), and (iii) controlling the environment of plant litter decomposition, including mediation of the microbial community (Fernandez and Kennedy, 2016; Frey, 2019). Plant litter decomposition is an important component of soil C cycling and is affected by its chemical composition (Berg and McClaugherty, 2008; Cornelissen et al., 2007), which is generally grouped as labile and recalcitrant components. The fate of carbon originating from components of various chemical recalcitrance will ultimately determine the decomposition and sequestration dynamics (Aponte et al., 2012; Cusack et al., 2009; Kalbitz et al., 2003; McClaugherty et al., 1985). Among the three major pathways of mycorrhizal impacts on soil C dynamics, the pathway of mycorrhizal fungal control on this decomposition environment and the fate of carbon is arguably understood the least.

To understand mycorrhizal fungal impacts on soil C dynamics, we need to distinguish between arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) and ectomycorrhiza (EM) types of symbiosis. Together, these types are possessed by over 80 % of plant species compromising the majority of terrestrial plant biomass (Brundrett and Tedersoo, 2018; Soudzilovskaia et al., 2019). While they are present in almost all ecosystems, it has been proposed that distinct mycorrhizal types are associated with specific ecosystems and soil attributes (Craig et al., 2018; Read and Perez-Moreno, 2003; Steidinger et al., 2019). Moreover, distinct mycorrhizal guilds differ in the pathways through which they affect the decomposition environment of plant litter. AM fungi (AMF) have limited or no ability to depolymerize organic macromolecules. They do not possess enzymes enabling nitrogen extraction and uptake from soil organic matter (Orwin et al., 2011; Treseder et al., 2016; Treseder and Allen, 2002) but primarily acquire inorganic nutrients mobilized by saprotrophic fungi and bacteria. Accordingly, plant litter subjected to AM fungi-dominated decomposition environment is likely to undergo a more balanced decomposition process, with both labile and recalcitrant components being degraded by saprotrophic decomposers. On the other hand, compared to AM fungi, most EM fungi (EMF) can produce enzymes involved in decomposing organic compounds of plant litter (Fernandez and Kennedy, 2015; Lindahl and Tunlid, 2015; Zak et al., 2019) and therefore have easier access to organic nutrients, especially so to nitrogen. It has been proposed that EMF increase the recalcitrance of decomposing litter, as their ability to uptake nitrogen while withholding carbon compounds from breaking down increases carbon-to-nitrogen ratios of decomposing plant litter (Nicolás et al., 2019; Read and Perez-Moreno, 2003; Rineau et al., 2013). This process of gradually increasing recalcitrance of plant litter subjected to an EM-dominated decomposition environment is further magnified by the suppression of saprotrophic decomposer activities, an effect known as the Gadgil effect (Fernandez and Kennedy, 2015; Gadgil and Gadgil, 1971; Smith and Wan, 2019). Yet the magnitude of the impacts induced by the differential roles of mycorrhizal types on the dynamics of decomposing plant litter is understood very poorly, especially so in quantitative terms.

Traditional field experiments are typically too short to assess the full complexity of the mechanisms underpinning the potential difference of AM and EM impacts on plant litter decomposition processes over time. In addition, traditional field experiments have limitations in explicitly distinguishing the individual pathways of mycorrhizal impacts on the decomposition process, including the fate of litter fractions of different chemical recalcitrance. An alternative tool to progress in our understanding of mycorrhizal impacts on plant litter decomposition is testing different formulations of mycorrhizal impacts in process-based models of litter decomposition and examining how well the models fit the observations.

Current deterministic models of soil C decomposition (e.g. CENTURY, DAYCENT, DAISY, DNDC, NCSOIL, RothC, and Struc-C) do not explicitly account for mycorrhizas as a driver of plant litter decomposition processes. Instead, climate and litter quality, the well-acknowledged regulators of soil organic carbon (SOC) and litter decomposition (Cornwell et al., 2008; Coûteaux et al., 1998; Cusack et al., 2009; Parton et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2008), are being modelled as primary drivers of all aspects of SOC dynamics. A body of recent studies have questioned the recognition of climate and litter quality as the only dominant regulators in SOC and litter decomposition (Bradford et al., 2016; García-Palacios et al., 2013; Wall et al., 2008) and plead for explicit inclusion of microbial and especially mycorrhizal impacts (Johnson et al., 2006; Shi et al., 2016) on SOC dynamics in biogeochemical models (Clemmensen et al., 2013; Craig et al., 2018; Todd-Brown et al., 2012; Wieder et al., 2013). However, so far, models assessing the role of mycorrhizas in SOC dynamics (e.g. Liang et al., 2017; Orwin et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2016) do not compare the relative impacts of mycorrhiza vs. climate on litter decomposition processes.

In this study, we aim to develop a framework allowing incorporation of mycorrhizal impacts on the decomposition of plant litter into a generic soil C model, specifically addressing one of the most poorly understood mechanisms of mycorrhizal impact on plant litter decomposition – the impact through controlling decomposition environment, separately from climate and other factors. Hereto we focus on answering the following four questions.

-

What is the best conceptualization, and accordingly the best representation, in a soil C dynamics model to describe mycorrhizal impacts on the decomposition of plant litter labile and recalcitrant carbon compounds?

-

To what extent does modelling mycorrhiza-associated impacts on the litter decomposition environment improve model performance, in terms of model errors, robustness, and temporal dynamics?

-

What is the sensitivity of model predictions to the uncertainty of parameters and input describing the pathways of decomposition as affected by mycorrhiza vs. climate and other factors?

-

How is the temporal dynamics of plant litter decomposition affected in AMF- vs. EMF-dominated decomposition environments in terms of both total C loss and loss of C from compounds of distinct recalcitrance?

Among available models of plant litter decomposition, the Yasso model (Tuomi et al., 2011a) provides an ideal framework for a mechanistic integration of mycorrhizal impacts into the modelling of plant litter decomposition processes. Yasso is among the models that underpin IPCC predictions of impacts of environmental change scenarios on global C cycles (IPCC, 2006; IPCC, 2019). In the Yasso model, plant litter is classified into five pools, characterized based on measurable chemical solubility of organic matter (Liski et al., 2005): compounds soluble in water (denoted with W); carbon compounds hydrolysable in acid (A); components soluble in a non-polar solvent, e.g. ethanol or dichloromethane (E); compounds neither soluble nor hydrolysable (N); and humus (H) (Berg and Agren, 1984; Palosuo et al., 2005). The W, A, and E pools together form the group of labile C fractions of soil organic matter, N is a recalcitrant but yet not mineral-bound C fraction, and the H pool represents the fraction of very stable soil C that remains in the soil for decades or centuries.

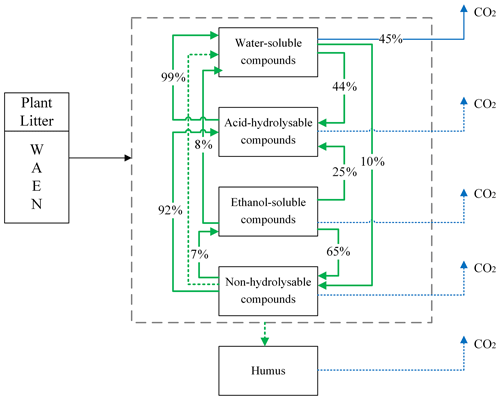

Yasso presents the litter decomposition process as a system of linear differential equations, and the total amount of carbon released from each pool is the result of fluxes between pools and C released to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. Figure 1 presents the schematic representation of the Yasso model, with carbon flows quantified from results of the original Yasso model formulation (Tuomi et al., 2011a; Viskari et al., 2020). H pool-related flows are not specified in this figure because humus can only be produced in deeper soil accessible to mineral compounds; thus it is not considered in this study of 10 years of litter decomposition simulations. Detailed descriptions of the original Yasso model and the dataset used for its parametrization are provided in Appendices A and B, respectively.

The conceptualization of litter decomposition as a process of C conversion into pools representing measurable C fractions makes Yasso a particularly suitable model for incorporating new (in our case, mycorrhizal) pathways that are based on or affected by differences in litter decomposability.

Figure 1Conceptual diagram of decomposition and mass flows between five carbon pools in Yasso. In the original Yasso model (Tuomi et al., 2011a, b), the fate of organic matter entering soil as plant litter material is represented as a series of carbon fluxes between carbon pools characterized by distinct decomposability (i.e chemical solubility) levels. Values in arrows show the percentage of C transformed between pools and leaving the pools per yearly time step (% yr−1) according to the original Yasso formulation and parameterizations (Tuomi, et al., 2011a; Viskari et al., 2020). Small flows are dotted lines.

2.1 Implementation of mycorrhizal impacts on decomposition in Yasso: general principles and data

We modified the Yasso model by adding mycorrhiza as a factor controlling the plant litter decomposition environment. Our model focuses on explaining the fate of aboveground plant litter that is decomposed at the topsoil layer before entering into deeper mineral soil or subsoil. During this stage, decomposers pre-process plant litter, liberating carbon compounds which – in a later stage – contribute to the accumulation of mineral-associated organic matter (MAOM) and particulate organic matter (POM) through different pathways in deeper soils (Bradford et al., 2016; Cotrufo et al., 2013, 2015, 2019; Sokol et al., 2019).

We conceptualized the mycorrhizal environment as a driver of soil organic carbon dynamics in addition to the drivers already accounted for by Yasso (i.e. temperature, soil moisture, and litter chemical composition). We modelled impacts of the mycorrhizal environment on plant litter decomposition as the sum of impacts caused by the predominance of AM and EM fungal types. The AM and EM fungal impacts were assumed to depend on the fungal-type-specific ability to affect the litter decomposition process and its biomass. As there are no data currently available about the global distribution of mycorrhizal fungal biomass, we approximated the AM and EM fungal biomass to be proportional to AM and EM plant biomass (the latter estimated as the product of the proportion of AM and EM plant biomass and the total vegetation gross primary production (GPP, using MODIS product-MOD17 data) (Running et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2005)).

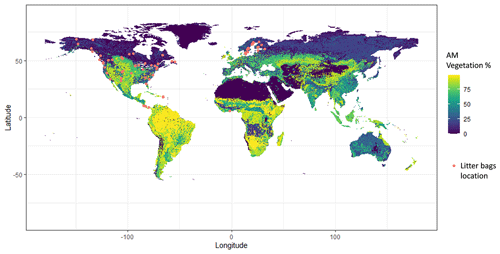

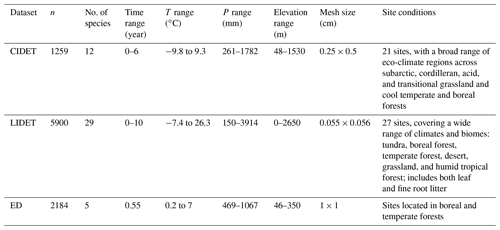

We calibrated our new model using litter decomposition databases (Appendix B) used in Yasso modelling that included total mass loss and the dynamics of different chemical components over time (Tuomi et al., 2009, 2011a, b): CIDET with the measurements from Canada (Trofymow, 1998), LIDET with data from the USA and Central America (Gholz et al., 2000), and Eurodeco (ED) with data gathered from several European research projects (Berg et al., 1991). Chemical composition data consist of the initial composition of litter in terms of W, A, E, and N fractions which were measured for each site. These data, together with other environmental data, were used for initializing the model. In addition, for the ED dataset, W, A, E, and N components had been determined during the decomposition process and at the end of the decomposition. In addition, all datasets were supplemented with site-specific estimates on the fractions of AM and EM vegetation within total plant biomass, which was extracted from the global mycorrhizal distribution map of Soudzilovskaia et al. (2019). To avoid potential mismatches between the actual fractions of AM and EM plants within the total plant biomass and the (generalized) data of AM and EM fractions derived from the map of Soudzilovskaia et al. (2019), the ecosystem type of each site was carefully checked for consistency with the map.

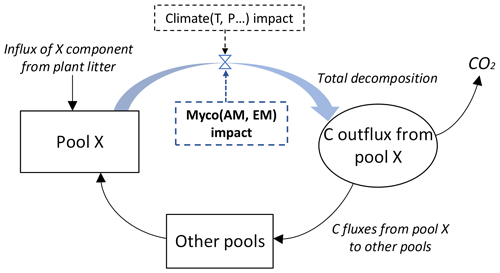

2.2 Mycorrhizal impact on total decomposition

Figure 2 shows the general principle to include the impacts of the mycorrhizal environment on each decomposition pool. The total carbon outflux of each W, A, E, and N pool is controlled by two factors: climate (as in the original YASSO model) and mycorrhizal decomposition environment (the new factor added to the model). See Appendix A for details on the decomposition terms used in YASSO.

Figure 2Carbon fluxes from and to each X pool of carbon, with X being W, A, E, or N, as represented by the modified Yasso model. The blue arrow and blue box show conceptualization of the added impact of the mycorrhizal environment on the litter decomposition process. While in the original version of the Yasso model plant litter decomposition process was represented as a function of climate and litter quality, in our model decomposition is a function of proportions of ectomycorrhizal and arbuscular mycorrhizal plants in vegetation, climate, and plant litter quality.

Accordingly, we modified the original form of the equations describing the decomposition rate of each W, A, E, and N element in the Yasso model. In the original model decomposition matrix (see Appendix A), only the climate was considered as a driver of decomposition Ki, where through Ki (C) (see Eq. A3 in Appendix A). In the new model formulation we added a term Mi representing the mycorrhizal impact on the total C outflux of each W, A, E, and N pool by Eq. (1):

The Mi term is described by Eq. (2):

where miAM and miEM are the impacts of AM and EM mycorrhizas on C loss from pool i, λAM and λEM are the fractions of AM and EM vegetation within the total vegetation biomass, and Gpp is the gross primary production of mycorrhizal vegetation.

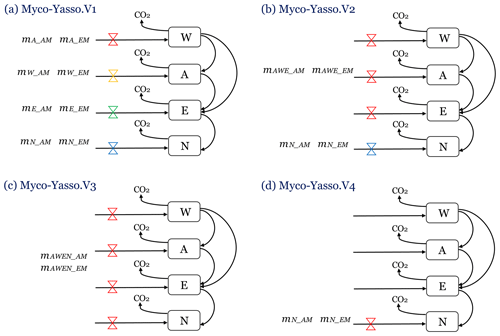

We compared four different conceptualizations of AM and EM impacts on distinct W, A, E, and N pools of decomposing litter, by evaluating the performance of four distinct model versions (Fig.3).

-

Myco-Yasso.v1 is a model where the magnitude of mycorrhizal impact on carbon loss from each of the W, A, E, and N pools differs among the pools (Fig. 3a), based on the assumption that mycorrhiza impact each pool differently.

-

Myco-Yasso.v2 is a model where mycorrhizal impacts on carbon loss from labile soil C pools (W, E, and A) are equal among the pools, while the mycorrhizal impact on carbon loss from the recalcitrant soil C pool (N) differs from the impact on C losses from labile pools (Fig. 3b), reflecting previous findings of the Yasso model that climate factors have similar impacts on W, A, and E pools but are different for the N pool (Tuomi et al., 2009; Viskari et al., 2020). We assume that mycorrhizal impacts are similarly differentiated.

-

Myco-Yasso.v3 is a model where mycorrhizal impacts on carbon loss are equal for all pools (Fig. 3c), based on the assumption that the impact is the same for all pools.

-

Myco-Yasso.v4 is a model where mycorrhiza affects only carbon loss from the recalcitrant soil C pool (N) (Fig. 3d), based on the assumption that mycorrhiza can only affect the most recalcitrant pool.

Figure 3Four conceptualizations of the possible mechanisms of mycorrhizal impacts on litter decomposition, modelled with four versions of the Myco-Yasso model. (a) Myco-Yasso.V1: mycorrhizal impacts differ for each of the W, A, E, and N pools. (b) Myco-Yasso.V2: mycorrhizal impacts on W, A, and E pools have the same magnitude, but the mycorrhizal impact on N pool is different. (c) Myco-Yasso.V3: mycorrhizal impacts on W, A, and E pools and N pools are equal. (d) Myco-Yasso.V4: mycorrhizae impact only for the N pool.

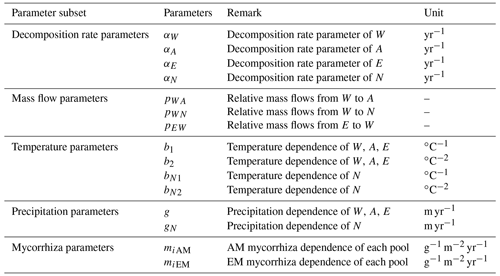

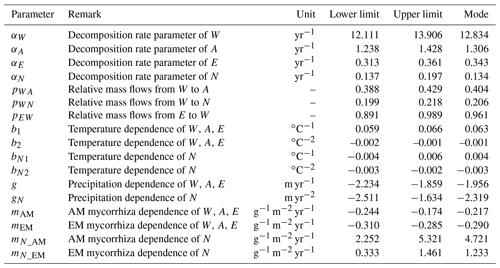

We used a Bayesian framework and a differential evolution Markov Chain with a snooker updater (DEzs; Braak and Vrugt, 2008) algorithm and Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) (Haario et al., 2001) for calibrating all relevant parameters following the original Yasso framework (Tuomi et al., 2011a; Viskari et al., 2020). Essential parameters from the original Yasso and newly derived mycorrhizal dependencies with corresponding symbols and units are explained in Table 1. We allowed miAM and miEM to vary from negative to positive values. The only control on priors of miAM and miEM is limiting Mi>−1 in Eq. (1) to make the algorithm meaningful. The other parameter priors were adopted from previous Yasso research (Tuomi et al., 2009). We performed cross-validation for each model, using 80 % of the decomposition time series randomly drawn from the dataset for calibration and the remaining 20 % of the decomposition time series for validation. After parameterization, all model versions were examined for Pearson's r and RMSE values of the correlation between the predicted and observed data for both the validation dataset and the full dataset. To account for the fact that the data in the different datasets varied in measurement uncertainty and the number of observations, we opted to compare the Pearson r and RMSE values of models separately for each dataset. We use the root mean square error (RMSE) from the 20 % validation dataset and Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) based on the 80 % data used for calibration as the criteria for comparing the relative quality of the models. The conceptualization with the lowest RMSE, AIC, and BIC was selected as the optimal model with the best performance.

2.3 Performance of the selected best mycorrhizal model of soil C sequestration

2.3.1 Model residuals and uncertainty analysis

We examined the residuals (differences between measurements and model-predicted litter decomposition) as a function of AM and EM fractions in the biomass of mycorrhizal vegetation. In addition, the uncertainty of the selected Myco-Yasso model was assessed in two aspects.

- a.

Variability in estimating total C mass loss through litter decomposition. The variability in the percentage of C mass remaining after 10 years of litter decomposition, as revealed by the original Yasso model and the selected Myco-Yasso model was examined by conducting Monte Carlo simulations for a hypothetic site. In line with previous sensitivity tests of Yasso (Liski et al., 2005), we chose the following input data to represent the conditions of decomposition: mean annual temperature of 5.2 ∘C and annual precipitation of 840 mm. For the Myco-Yasso model, the mycorrhizal impact in Eq. (2) was quantified by assuming an AM mycorrhizal plant biomass proportion of 38 %, EM mycorrhizal plant biomass proportion of 36 %, and a GPP of 1516 g m−2 yr−1. We used the following global mean values for the chemical composition of litter: W fraction −20.6 %, A fraction −43.0 %, E fraction −8.7 %, and N fraction −27.7 %. We ran 1000 simulations using parameter values randomly selected from an even distribution of the input parameters within their uncertainty ranges.

- b.

Sensitivity to parameters and input. With environmental conditions and chemical composition of the litter being the same as used in part (a), we evaluated the sensitivity of litter decomposition by separately increasing model parameters by 1 % and input values by 1 % of variations across the dataset in 10 years of model runs. This test was conducted for both the original Yasso model and the selected Myco-Yasso model.

2.3.2 Temporal dynamics of the model

- 1.

Model performance over time.

We examined the ability of the selected model in predicting litter decomposition at different times following litter input, by comparing model predictions of C mass remaining to real measurements of the remaining C at the same time moment. The time slots were classified according to the datasets' characteristics, as litter decomposition measurements for different datasets were taken at different months in a year.

- 2.

Mycorrhizal impact on labile and recalcitrant litter pools.

To analyse total litter decomposition and the different litter pools, simulations of 10 years of litter decomposition were conducted in different mycorrhizal environments with varying AM : EM vegetation biomass proportions. Input values in terms of environmental factors and chemical fractions were set consistent with the standard conditions as used in the sensitivity analysis. To evaluate model performance consistency, the analysis was done using chemical fractions of typical root and leaf litter as contrasting litter types (Appendix D).

3.1 Model comparison and selection

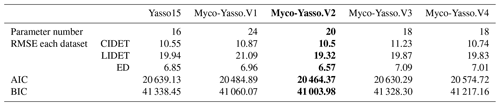

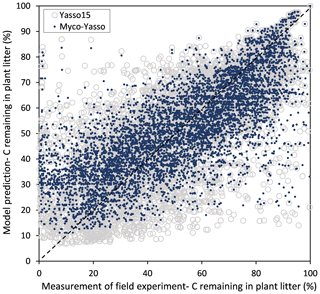

For all four model versions examined, the calibration based on all three decomposition datasets showed a high correlation between measurements and model predictions, with Pearson's r being 0.84–0.86 for CIDET, 0.67–0.68 for LIDET, and highest with 0.90–0.91 for ED, which also contained information on carbon pools through time. Small differences occurred between individual versions of Myco-Yasso models. However, the model RMSE comparisons revealed that the Myco-Yasso V2 provided the strongest RMSE decrease among all Myco-Yasso models compared to the original Yasso15 model. This pattern was consistent through all datasets (Table 2). The AIC and BIC confirmed that the Myco-Yasso V2 has the best performance. Based on the RMSE, AIC, and BIC, we selected Myco-Yasso V2 as a model representing the optimal conceptualization of mycorrhizal impact on plant litter decomposition. In this model V2, the mycorrhizal impact is similar among labile C compounds (WAE) but different for the recalcitrant C compound (N). Hereafter, this optimal model is referred to as Myco-Yasso. Scatterplots showing model improvement in terms of observed vs. predicted values for the Myco-Yasso model compared to the original Yasso15 model are provided in Appendix C. Details of parametrization outcomes of the Myco-Yasso model are provided in Table C1.

Table 2Model performance based on RMSE for the 20 % validation dataset and AIC and BIC for the 80 % data used for calibration. Model predictions are based on the total mass remaining in plant litter of different mycorrhizal model versions for different litter decomposition datasets. The selected model and its performance indexes are in bold.

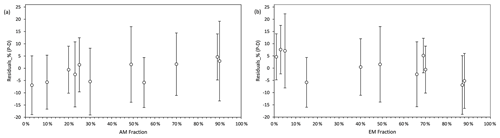

3.2 Model performance across the range of mycorrhizal plant biomass fractions in vegetation

The standardized residuals for the litter decomposition measurements (percent of C decomposed from initial plant litter) as a function of AM and EM fractions in the biomass of mycorrhizal vegetation are shown in Fig. 4. Within the 95 % probability density covered by 2σ intervals, model predictions agreed well with measurements across the entire range of fractions of biomass AM and EM plants in vegetation. The model had relatively large negative residuals at low values of the AM fractions (AM <10 %) and high values of EM fractions (EM >85 %) but relatively large positive residuals at low values of EM fractions (EM <10 %), which suggest a lower predictive power for these conditions.

Figure 4Standardized residuals (predictions – measurements, P–M) of decomposition, expressed as percent mass loss, modelled by Myco-Yasso as a function of the abundance of AM mycorrhizal plants (a) and EM mycorrhizal plants (b) in vegetation. The circle in the middle of each line is the mean value of the residuals. The intervals contain residuals within 95 % probability intervals.

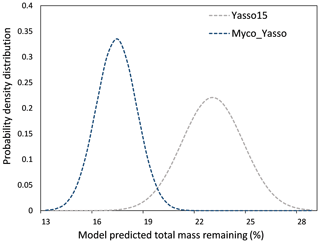

3.3 Variability in litter decomposition estimations

The 1000 simulations of the Yasso15 model ran for the conditions of a hypothetical site with prescribed environmental conditions revealed a normally distributed dataset with μ = 22.56 % and σ = 1.81 % mass remaining. The same simulations conducted by the Myco-Yasso model yielded a dataset with a lower μ (16.90 %) and lower σ (1.19 %), indicating a lower total sensitivity of the Myco-Yasso model to variation in input parameters. The best-fit normal distributions of these two model predictions are shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5The probability density distribution of litter mass remaining as predicted by Yasso15 compared to Myco_Yasso. Compared to predictions of Yasso15, Myco-Yasso reduces the variation in the predictions of C mass remaining from decomposing litter after 10 years of decomposition. The probability density is based on 1000 model runs for conditions of a hypothetical site with the prescribed environmental conditions (see descriptions in Sect. 2.3.1).

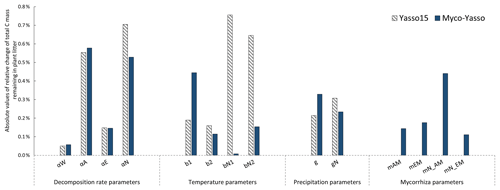

3.4 Sensitivity of litter decomposition to parameters and input values

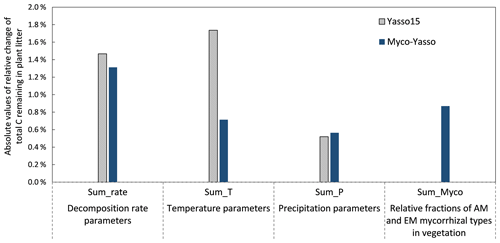

The sensitivity of the Myco-Yasso model to the individual litter decomposition parameters is shown in Fig. 6. The Myco-Yasso model showed the highest sensitivity to the impact of arbuscular mycorrhizal vegetation of the N pool (mN_AM) out of the four mycorrhizal impact parameters (Fig. 6). This implies that an AM environment has a much stronger stimulating effect on the decomposition of the recalcitrant pool compared to an EM environment. In contrast, the decomposition from the labile pools was only a bit more stimulated by an EM environment than by an AM environment. Concerning the decomposition rate parameters, the overall carbon loss in the Myco-Yasso model has a considerably lower sensitivity to the total decomposition rate of the N pool (αN) and a slightly increased sensitivity to the decomposition rate of the A pool (αA) compared to Yasso15. However, the total impact of all α terms together on carbon loss predictions is generally similar in Myco-Yasso compared to Yasso15 (Fig. C3).

Analysis of the environmental dependencies of the Myco-Yasso (Fig. 6) revealed that the new model is less sensitive to the overall variability in temperature parameters (b1, b2, bN1, and bN2) than the original Yasso15 model, although the overall effect of temperature sensitivity decrease (Fig. C3) is mostly driven by the decreased sensitivity of N pools to temperature (bN1 and bN2). The sensitivity to precipitation parameters (g and gN) of Myco-Yasso is generally similar to Yasso15, with a slight increase in sensitivity of the W, A, and E pools to precipitation (g parameter) and a slight decrease in sensitivity of the N pool to precipitation (gN). The resulting impacts on carbon transformation in the respective pools are provided in Fig. C4.

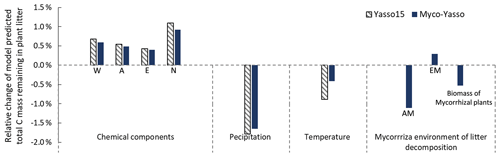

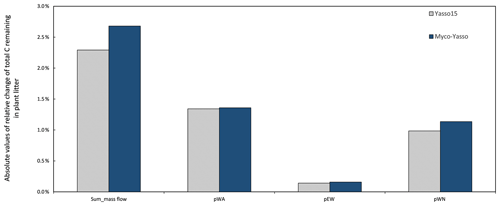

Figure 7 shows the model sensitivity to an increase in each input parameter by 1 % including effects of initial plant litter chemistry, climate parameters, and the mycorrhizal environment of decomposition. With an increase in biomass of mycorrhizal plants, less carbon will remain of the decomposing plant litter after 10 years of decomposition. This impact is similar in magnitude to the impact of temperature increase. An increase in EM dominance leads to a slight increase in carbon accumulation, while AM dominance speeds up decomposition to a similar extent as temperature increases. The Myco-Yasso shows a slight decrease in sensitivity to climate variables compared to Yasso15, confirming our supposition that potential mycorrhizal impacts were partly accounted for by climate variables in the original Yasso15. The magnitude of sensitivity of plant litter decomposition to the mycorrhizal environment is comparable to the sensitivity to climate (Figs. 6, 7, and C3).

Figure 7Model sensitivity to 1 % increase in model input values. Impacts of input parameters are shown in terms of the relative change in total C remaining after 10 years of decomposition. The “AM” bar shows the impact of an increase in AM plant biomass by 1 %, while EM plant biomass remains unchanged. The “EM” bar shows the impact of an increase in EM plant biomass by 1 %, while AM plant biomass remains unchanged. The “Biomass of mycorrhizal plants” bar shows the impact of an increase in the combined biomass of AM and EM plants by 1 % while the AM and EM distribution within the vegetation remains unchanged.

3.5 Model predictions of temporal dynamics of plant litter decomposition

3.5.1 Model performance over time

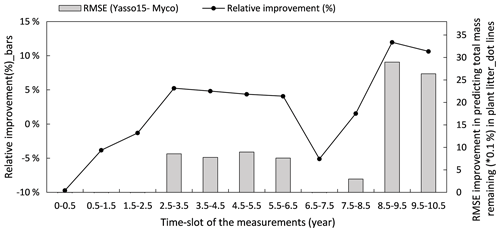

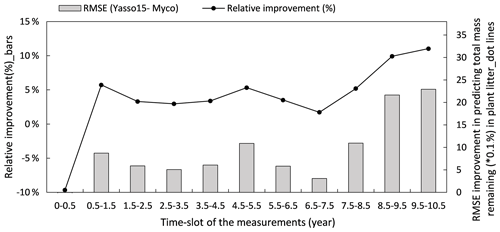

Figure 8 illustrates how the model predictions of the Myco-Yasso improve the modelled decomposition over time compared to the original Yasso15 model using the full dataset. The differences in models' prediction accuracy (RMSE of the Yasso15 predictions minus RMSE of Myco-Yasso predictions) has a trend of increment over time, indicating an increasing impact of mycorrhizas on litter decomposition dynamics across 10 years. The examination with only validation comparing the original model Yasso15 and Myco-Yasso is provided in Appendix C, Fig. C5.

Figure 8Improvement of performance comparing the Myco-Yasso model to the original Yasso model over the decomposition period. Bars represent the relative RMSE differences between Yasso15 and Myco-Yasso per period. The line with dots shows the absolute value of the RMSE differences (Yasso15- Myco). Predictions examined from the full dataset simulation.

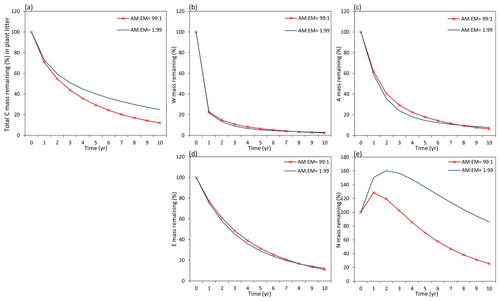

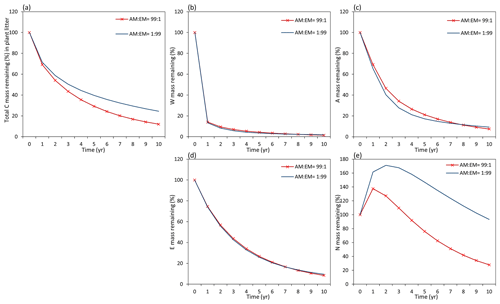

3.5.2 Mycorrhizal impact on labile and recalcitrant pools

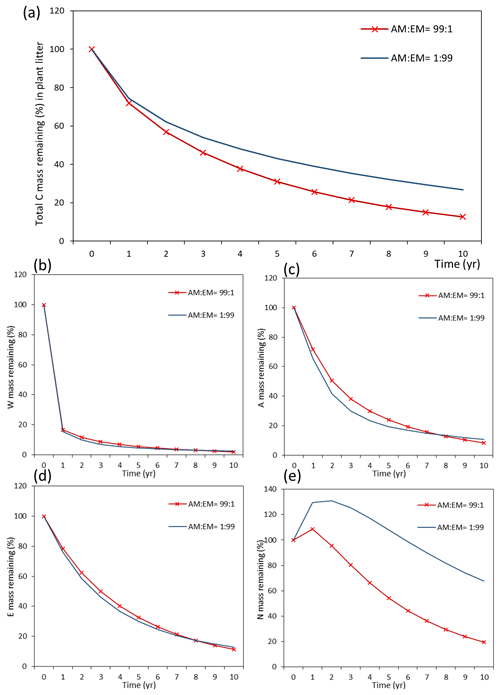

Assessments of the dynamics of total litter mass decomposition under the dominance of AM and EM vegetation with Myco-Yasso (Fig. 9a) revealed that, at the 10th year of decomposition, plant litter (with equal initial chemical composition) will have ca. 15 % less carbon remaining if decomposed in an AM-dominated environment compared to an EM-dominated environment. During the first decomposition year, litter subjected to AM or EM decomposition environments decomposes with a similar rate, while at the later stages (after 1 year), litter subjected to an AM environment decomposes faster. The difference in the total mass remaining in an AM vs. EM dominant environment increases during the decomposition period from 2–10 years.

Figure 9Dynamics of plant litter decomposition in AM-dominant vs. EM-dominant environments. (a) Decomposition of total carbon mass from plant litter. (b, c, d) The dynamics of C remaining from labile carbon components (W – water-soluble C fraction, E – ethanol-soluble C fraction, A – acid-hydrolysable C fraction). (e) Dynamics of carbon remaining from recalcitrant C component (N – non-hydrolysable fraction).

Examining the dynamics of carbon loss from distinct individual decomposition pools (Fig. 9b–e) shows that labile carbon components of plant litter (W, A, E) decompose with a similar rate in AM and EM environments. Recalcitrant carbon litter compounds (N) tend to accumulate during the first 2 years. After that, C loss starts to take place in an EM-dominant environment, promoting the accumulation in the N pool compared to an AM-dominant environment. Comparison among distinct litter types reveals that this pattern is not affected by initial litter quality (Figs. D1 and D2).

Mycorrhizal vegetation types are widely recognized to have a strong impact on plant litter decomposition processes and soil carbon pool dynamics. Yet, the mechanisms of mycorrhizal impacts on the soil C cycle are not well-understood, and available data of the relationship between soil C pools and dominance of distinct mycorrhizal types of vegetation are often contrasting each other at both the local (Craig et al., 2018; Phillips et al., 2013) and global scales (Soudzilovskaia et al., 2019; Steidinger et al., 2019). The matter is additionally complicated by the fact that mycorrhizas affect C cycles via three distinct pathways of (1) provisioning dead mycelium as substrate for decomposition, (2) mediating plant litter quality and amounts, and (3) controlling the environment of plant litter decomposition. Earlier works did not explicitly differentiate between these pathways (Johnson et al., 2006) or focused mainly on the second pathway (Brzostek et al., 2014). Our study is the first attempt to incorporate the impacts of different mycorrhizal environments on litter decomposability, i.e. the third pathway, into a plant litter decomposition model. Herewith, we explicitly focus on impacts of the mycorrhizal environment on the plant litter decomposition process in topsoils, where plant litter is transformed into soil organic matter and carbon compounds are pre-processed for further potential incorporation into particulate organic matter or mineral-associated (i.e. stable) organic matter. We assessed a full range of concepts representing mycorrhizal impacts on labile and stable components of decomposing litter across a wide range of eco-environmental conditions varying in plant species, litter types, and climate variables (Table B1). Overall, the model Myco-Yasso fits the litter decomposition datasets well, especially considering the high level of noise in some of the data and the environmental variation among the sites, in terms of geology, soil quality, and other alike parameters not described by the model. Based on this assessment, we provide insights into the role of distinct mycorrhizal types in long-term decomposition processes of labile and recalcitrant components of plant litter.

4.1 Improved representation of temporal dynamics of litter C

There are still many uncertainties and unknowns in the temporal dynamics of litter decomposition, even though it is an essential process with the soil C cycle. Decomposition encompasses changes in both the composition of soil and litter C and in their breakdown (García-Palacios et al., 2016). This duality, in combination with the long-term nature of the processes involved, makes experimental assessments of temporal dynamics of SOC formation extremely difficult. This is especially true for measuring flows between pools. This supports using modelling approaches, although models may lead to misinterpretations when lacking a theoretical basis. Incorporation of mycorrhizal impacts into Yasso improved the overall model predictions of topsoil C across 10 years, indicating that mycorrhizal impact is a vital factor to be accounted for in analyses of long-term litter decomposition processes, at least in the topsoil layer. The mycorrhizal impacts are likely less visible in the short-term (<3 years), and detectable effects of the mycorrhizal environment on litter decomposition should be assessed over a longer period. This is in agreement with earlier studies (e.g. Paterson et al., 2008) that have shown in short-term 13C-labelling experiments that labile and recalcitrant plant litter fractions are utilized by distinct microbial communities, while in the short-term, these communities are not shaped by the presence or activity of mycorrhizal fungi.

4.2 Explicit separation of climate vs. mycorrhizal impacts

Our model allows explicit quantification of mycorrhizal impacts on the decomposition environment and separates these impacts from those of climatic factors. In the original Yasso model, soil C pools are controlled by litter quality and climate, with the “climate” factor implicitly accounting for all global variation in environmental conditions. That original model had high predictive power, especially so for short-term decomposition processes, to which our re-formulation could provide only an incremental improvement. However, the oversimplification of the role of climate without considering microbial factors hinders the ability of models to examine future impacts of alterations in the climate on soil C dynamics (Pongratz et al., 2018). Such a lack of mechanistic and quantitative representation of belowground processes is recognized to be a principal source of uncertainty in our quantification of global terrestrial biogeochemical cycles (Nyawira et al., 2017; Pongratz et al., 2018; Todd-Brown et al., 2013; Trumbore, 2006). There have been recent efforts to incorporate microbial impacts to better represent soil processes in models, such as CORPSE (Sulman et al., 2014), MIMICS (Wieder et al., 2015), and Millennial (Abramoff et al., 2018). Our study is among the first attempts to enable quantification of the impacts of the mycorrhizal environment and to explicitly model mycorrhizal impacts on litter decomposition processes and topsoil C dynamics.

Compared to the original Yasso15 model, the Myco-Yasso model has a lower sensitivity to variation in temperature. The decrease in decomposition sensitivity to temperature suggests that the impact of temperature on decomposition could have been overestimated in previous global modelling attempts that did not consider mycorrhizae as a driving factor. Undoubtedly, the temperature regime controls soil and litter respiration (Hobbie, 1996), making the sensitivity to temperature in a soil C cycle model an essential issue for better estimating future soil C stocks change and its feedback to climate. While modelling approaches allow us to distinguish these mechanisms, separation of these two factors from global field observations is extremely difficult because of a tight correlation of mycorrhizal distributions to gradients in temperature (Barceló et al., 2019; Soudzilovskaia et al., 2015).

4.3 Mycorrhizal impact on labile litter pools is distinct from that on recalcitrant litter pools

We tested four principally distinct concepts on the impact of the mycorrhizal environment on plant litter decomposition. The selected model imposes distinct impacts in terms of both magnitude and direction on labile vs. recalcitrant carbon pools. This finding supports the theory that the turnover of litter depends largely on its composition and recalcitrance of biopolymers (Baldrian, 2017; Berg and McClaugherty, 2008; Cornelissen et al., 2007; Gui et al., 2017), while distinct mycorrhizal types differ in strategies with respect to processing simple organic compounds and recalcitrant compounds (Rajala et al., 2011). This translates into an accumulation of recalcitrant C components of not-yet-decomposed plant litter material in EM-dominated environments, while AM-dominated environments generally promote decomposition. While the presence of AM does not directly affect decomposition, the theory that AMF can exert an indirect influence on this process through regulating free-living groups of decomposers in the soil is well supported. AM fungi alter the physicochemical environment for the microbial community and modify soil bacterial communities (Gui et al., 2017; Nuccio et al., 2013; Offre et al., 2007). AMF stimulate the activity of particular bacteria (Franco-Correa et al., 2010), which are known to be capable of catalysing an efficient degradation of labile and recalcitrant plant litter (Bayer et al., 1998; Kersters et al., 2006). Furthermore, AMF has been shown to prime the decomposition of organic matter by supplying plant-derived labile C to saprotrophic fungi and bacteria (de Vries and Caruso, 2016), which results in higher microbial turnover and respiration and decreasing the soil C pool.

In contrast, efficient nutrient uptake by EM fungi promotes immobilization of soil nitrogen in complex organic molecules of high recalcitrance and therewith promotes the formation of microbial communities, mostly consisting of saprotrophic fungi, able to decompose such recalcitrant organic substrates (Fernandez and Kennedy, 2016; Langley and Hungate, 2003). While multiple studies examining the genetic potential of ectomycorrhizal fungi have shown that EM fungi are capable of producing enzymes degrading complex C and humus (Nicolás et al., 2019), the abundance of such genes is generally low compared to saprotrophic fungal guilds.

Yet, the question of which direction EM impacts soil C the most in the long term has remained unanswered. Similarly, the long-term impacts of AM fungi on saprotrophic communities have, to our knowledge, never been evaluated quantitatively. Our modelling exercises provide a quantitative examination of the long-term consequences of the differential AM and EM impacts on topsoil C across 10 years and suggests that more C is conserved in an EM-dominant environment than an AM environment, particularly due to the accumulation of recalcitrant carbon compounds (independent of the associated litter quality). Moreover, we show that the long-term impacts of both types of mycorrhizas on labile carbon components are similar.

4.4 Future improvements of mycorrhizal impacts of SOC modelling

Our model improves the accuracy of predictions of SOC dynamics even though we assessed the litter decomposition processes in topsoil profiles across 10 years only. Formation of the most recalcitrant soil pool, defined by the Yasso model as “humus” (Tuomi et al., 2011a), was not examined in our study, because we assumed that a 10-year period of litter decomposition for which we had detailed data for model calibration was not long enough for forming humus. Future work should aim at including mycorrhizal impacts on humus formation, linking short- and medium-term decomposition processes to the ultra-long SOC dynamics.

Furthermore, our current work examines the dynamics of topsoil C in terms of labile and stable compounds, yet not addressing the fate of stable, mineral-associated soil C, the ultimate pool of soil-sequestered C. During the last decade, the question of whether mineral-associated soil C originates from labile C components, possibly undergoing microbial transformation (Cotrufo et al., 2015, 2019; Mambelli et al., 2011), or develops through direct sorption of poorly decomposed plant compounds was intensively debated (Bradford et al., 2016; Sokol et al., 2019). Recent research (Sokol et al., 2019) has proposed that both pathways are possible, depending on the capability of the environment to support the release of labile C compounds. While our work does not address the pathway of formation of mineral-stabilized carbon, it provides insights into the important processes preceding C mineral stabilization, as we examine the long-term processes in labile C pools that are potentially available for microbial uptake and the development of recalcitrant plant litter pools that potentially form MAOM by binding to mineral particles. Our study suggests that an EM-dominated decomposition environment tends to promote the accumulation of poorly decomposed plant compounds, supporting the pathway of mineral-associated soil C from undecomposed plant material, which suggests that EM- and AM-dominated ecosystems differ in POM and MAOM fractions contributing to the process of further SOC decomposition. The question of to what extent this pathway dominates the entire flux of soil C into the pool of mineral-associated C needs to be further evaluated. Such evaluation should additionally consider the processes omitted in this study such as fluxes of labile C from the root and fungal exudates and C fluxes originating from the decomposition of dead mycelium of mycorrhizal fungi (Baskaran et al., 2017; See et al., 2021).

Our study is the first attempt to model the impacts of the mycorrhizal environment on litter decomposition in topsoil profiles based on differences in carbon release from specific soil chemical pools within pathways of respiration and mass transformation. While mycorrhizae are widely recognized as important factors controlling SOC dynamics, the quantification of these impacts has not been possible thus far. Our work creates a benchmark in such quantifications and enables explicit separation of mycorrhizal impacts from impacts by climate factors in determining topsoil carbon formation processes, which can be applied to a broad range of ecosystems.

The dynamics of decomposition and accumulation of labile and recalcitrant litter compounds is shaped by the abundance of arbuscular and ectomycorrhizal plants in vegetation: if plant litter is decomposed in EM-dominated vegetation, the accumulation of recalcitrant components of that litter in soil is twice as high as in soils of ecosystems dominated by AM vegetation. This difference is likely to affect pathways of accumulation of soil C. We conclude that mycorrhizal traits are an important driver of soil carbon dynamics the impacts of which should be examined quantitatively when estimating future terrestrial carbon storage and predicting impacts of climate change.

The Yasso model represents the decomposing plant litter as five pools of soil carbon, W, A, E, N, and H, varying in recalcitrance. Each pool has its specific decomposition rate (independent from litter type and the initial amount of composition) (Liski et al., 2005; Tuomi et al., 2011a). The model presents the litter decomposition process as a system of linear differential Eq. (A1):

where x(t) is a vector describing the mass of individual carbon pools as a function of time (t); x(0) = x0 represents the initial amount of each carbon fraction; b(t) is the litter input; and A(D) is a matrix describing the total decomposition as a function of climatic conditions (D), where the diagonal values represent the fraction of C being removed from the pool and the non-diagonal terms specify the amount of C transferred to other pools (Viskari et al., 2020).

The total amount of carbon released from individual W, A, E, N, and H pools is the result of two fluxes: (1) carbon transformation from and to other pools and (2) carbon that is not transferred to other pools but instead released to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. The mass fluxes between the different pools and to outside the system are accordingly determined by two parameter sets: pij represents the mass transportation between pools, and αi represents the total decomposition rate of each pool, i.e. the C mass leaving the pool (the sum of C transfer to other pools and C released into the atmosphere). The total mass flux between two pools is thus a product of these two parameters; e.g. the mass flux from pool A to pool W is αA⋅pAW.

The total decomposition represented by matrix A(D) within the whole system can be represented as a mathematical equation with a mass flow matrix, where parameters denote the flows between each pair of W, A, E, N, and H pools i and j, and K(D) represents the impact of climate on decomposition rate Eq. (A2).

In the matrix K(D), each element ki(D) describes the decomposition of W, A, E, N, and H as a function of temperature (T) and annual precipitation (P) modelled according to Eq. (A3):

where αi represents decomposition rate parameters; bi1 and bi2 are parameters describing the dependency of heterotrophic respiration on temperature, assessed through a Gaussian model (Tuomi et al., 2009); and gi is a parameter describing the dependency of heterotrophic respiration of precipitation, assessed through an exponential function (Tuomi et al., 2009). Systematic error in the litter decomposition resulting from litter leaching out of the litter bags was corrected by leaching parameters.

There are three main litter decomposition databases used in both the original Yasso modelling (Tuomi et al., 2011a) and our new model parameterization: CIDET dataset with the measurements from Canada (Trofymow, 1998), the LIDET dataset with data from the USA and Central America (Gholz et al., 2000), and the Eurodeco (ED) dataset with data gathered from several European research projects (Berg et al., 1991). The distributions of these experimental sites are shown in Fig. B1. Details of these datasets used to parametrize our new model are shown in Table B1.

The original Yasso model also uses a dataset with information of SOC accumulation along thousands of years at sites in Finland (Liski et al., 2005) and a large global soil C stock measurements dataset (Zinke et al., 1986) to infer the dynamics of the most stable carbon – humus pool in soil (see Fig. 1). However, given our focus on impacts of mycorrhizas on the dynamics of chemical compounds during plant litter decomposition, and given that the LIDET, CIDET, and ED databases of litter decomposition, used for calibration of our modified YASSO model, store data of 0–10.5 years of decomposition, we assumed no measurable amounts of humus being formed during this time frame. Therefore, the mycorrhizal impacts on H-related decomposition terms (αH and pNH; see Fig. 1) were set to zero.

Table C1Posterior and 95 % Bayesian credibility intervals (confidence limits) for the Yasso_Myco parameters.

Figure C1Scatter plot of predictions for C loss from plant litter made by the original Yasso15 model (grey circles) and predictions made by the Myco-Yasso model (blue dots) compared to experimental measurements.

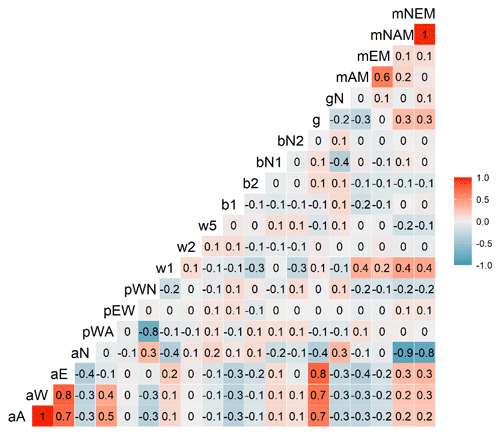

Figure C2Correlations between parameters of the Myco-Yasso C model. The gradient from the most intensive blue colours to the most intensive red colours indicate correlations from completely negative (−1) to completely positive (1).

Figure C3Model sensitivity of the Yasso15 and Myco-Yasso models to individual groups of parameters. The impact of increases by 1 % of each parameter is shown.

Figure C4Sensitivity of Yasso15 and Myco-Yasso models to 1 % increase in mass flow parameters. The two leftmost bars show the sensitivity to the joint impact of all p-term parameters being increased by 1 %. The other bars show the impact of 1 % increase in individual p terms: pWA – C flux from the W to A pool, pEN – C flux from the E to N pool, and pWN – C flux from the W to N pool.

Figure D1Dynamics of plant root litter decomposition in AM-dominated vs. EM-dominated environments. (a) Loss of total carbon mass from root litter. (b, c, d) Dynamics of loss of labile carbon components (W – water-soluble C pool, A – acid-hydrolysable C pool, E – ethanol-soluble C pool). (e) Dynamics of loss of recalcitrant (non-hydrolysable) carbon (N pool). The initial W, A, E, and N composition of root material is 17 % – W, 55 % – A, 9 % – E, and 20 % – N (typical for plant roots).

Figure D2Dynamics of plant foliage (leaf) litter decomposition in AM-dominated vs. EM-dominated environments. (a) Loss of total carbon mass from foliage litter. (b, c, d) Dynamics of loss of labile carbon components (W – water-soluble C pool, A – acid-hydrolysable C pool, E – ethanol-soluble C pool). (e) Dynamics of loss of recalcitrant (non-hydrolysable) carbon (N pool). The initial W, A, E, and N composition of leaf material is 25 % – W, 45 % – A, 12 % – E, and 18 % – N (typical for plant foliage).

The initial Yasso15 model is available from the developers’ repository at https://github.com/YASSOmodel/YASSO15 (last access: 14 November 2021). The code used for calibrating Yasso is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5059909 (Viskari et al., 2021). The extended code and data for calibrating the models and producing the results, as well as input data, and scripts used in this publication have also been uploaded to Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5579682 (Huang et al., 2021). Original litter decomposition data used for this work were provided by the data owners of the different long-term experiments. Please contact them to get access to the original decomposition data (see Table B1).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-19-1469-2022-supplement.

WH, PMB, and NAS conceived the original idea and planned the project. JL and TV were involved in planning the project. WH performed the simulations and analysis of the results. TV provided expert guidance on Yasso modelling. JL provided the data and expertise on the litter decomposition data used in the study. PMB, NAS, and TV provided insight into the methods as well as the interpretation of the results. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper.

The contact author has declared that neither they nor their co-authors have any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We gratefully acknowledge the researchers whose data and model are used in the analyses. We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions. Weilin Huang is grateful to the China Scholarship Council (CSC) for providing financial support (grant no. 201706040071).

This research has been supported by the Vidi grant from Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (grant no. 016.161.318) issued to Nadejda A. Soudzilovskaia.

This paper was edited by Serita Frey and reviewed by four anonymous referees.

Abramoff, R., Xu, X., Hartman, M., O'Brien, S., Feng, W., Davidson, E., Finzi, A., Moorhead, D., Schimel, J., Torn, M., and Mayes, M. A.: The Millennial model: in search of measurable pools and transformations for modeling soil carbon in the new century, Biogeochemistry, 137, 51–71, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-017-0409-7, 2018.

Aponte, C., García, L. V., and Marañón, T.: Tree species effect on litter decomposition and nutrient release in mediterranean oak forests changes over time, Ecosystems, 15, 1204–1218, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-012-9577-4, 2012.

Averill, C., Bhatnagar, J. M., Dietze, M. C., Pearse, W. D., and Kivlin, S. N.: Global imprint of mycorrhizal fungi on whole-plant nutrient economics, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 23163–23168, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1906655116, 2019.

Baldrian, P.: Microbial activity and the dynamics of ecosystem processes in forest soils, Curr. Opin. Microbiol., 37, 128–134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2017.06.008, 2017.

Barceló, M., van Bodegom, P. M., and Soudzilovskaia, N. A.: Climate drives the spatial distribution of mycorrhizal host plants in terrestrial ecosystems, J. Ecol., 107, 2564–2573, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.13275, 2019.

Baskaran, P., Hyvönen, R., Berglund, S. L., Clemmensen, K. E., Ågren, G. I., Lindahl, B. D., and Manzoni, S.: Modelling the influence of ectomycorrhizal decomposition on plant nutrition and soil carbon sequestration in boreal forest ecosystems, New Phytol., 213, 1452–1465, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14213, 2017.

Bayer, E. A., Chanzy, H., Lamed, R., and Shoham, Y.: Cellulose, cellulases and cellulosomes, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 8, 548–557, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-440X(98)80143-7, 1998.

Berg, B. and Agren, G. I.: Decomposition of needle litter and its organic chemical components: theory and field experiments. Long-term decomposition in a Scots pine forest. III., Can. J. Bot., 62, 2880–2888, https://doi.org/10.1139/b84-384, 1984.

Berg, B. and McClaugherty, C.: Plant Litter, 2nd edn., Decomposition, Humus Formation, Carbon Sequestration, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, ISBN 978-3-540-74922-6, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-74923-3, 2008.

Berg, B., Booltink, H., Breymeyer, A., Ewertsson, A., Gallardo, A., Holm, B., Johansson, M., Koivuoja, S., Meentemeyer, V., Nyman, P., Olofsson, J., Pettersson, A., Reurslag, A., Staaf, H., Staaf, I., and Uba, L.: Data on needle litter decomposition and soil climate as well as site characteristics for some coniferous forest sites, Part 1 and 2: Site characteristics and Decomposition Data, 2nd edn., Sect. 2, Data on needle litter decomposition; Report no. 42, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Ecology and Environmental Research, Uppsala, ISBN 91-576-4341-5, 1991.

Bödeker, I. T. M., Lindahl, B. D., Olson, Å., and Clemmensen, K. E.: Mycorrhizal and saprotrophic fungal guilds compete for the same organic substrates but affect decomposition differently, Funct. Ecol., 30, 1967–1978, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12677, 2016.

Braak, C. J. F. and Vrugt, J. A.: Differential Evolution Markov Chain with snooker updater and fewer chains, Stat. Comput., 18, 435–446, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11222-008-9104-9, 2008.

Bradford, M. A., Berg, B., Maynard, D. S., Wieder, W. R., and Wood, S. A.: Understanding the dominant controls on litter decomposition, J. Ecol., 104, 229–238, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12507, 2016.

Brundrett, M. C. and Tedersoo, L.: Evolutionary history of mycorrhizal symbioses and global host plant diversity, New Phytol., 220, 1108–1115, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14976, 2018.

Brzostek, E. R., Fisher, J. B., and Phillips, R. P.: Modeling the carbon cost of plant nitrogen acquisition: Mycorrhizal trade-offs and multipath resistance uptake improve predictions of retranslocation, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 119, 1684–1697, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JG002660, 2014.

Clemmensen, K. E., Bahr, A., Ovaskainen, O., Dahlberg, A., Ekblad, A., Wallander, H., Stenlid, J., Finlay, R. D., Wardle, D. A., and Lindahl, B. D.: Roots and associated fungi drive long-term carbon sequestration in boreal forest, Science, 339, 1615–1618, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1231923, 2013.

Cornelissen, J., Aerts, R., Cerabolini, B., Werger, M., and Van der Heijden, M.: Carbon cycling traits of plant species are linked with mycorrhizal strategy, Oecologia, 129, 611–619, https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420100752, 2001.

Cornelissen, J. H. C., Van Bodegom, P. M., Aerts, R., Callaghan, T. V., Van Logtestijn, R. S. P., Alatalo, J., Stuart Chapin, F., Gerdol, R., Gudmundsson, J., Gwynn-Jones, D., Hartley, A. E., Hik, D. S., Hofgaard, A., Jónsdóttir, I. S., Karlsson, S., Klein, J. A., Laundre, J., Magnusson, B., Michelsen, A., Molau, U., Onipchenko, V. G., Quested, H. M., Sandvik, S. M., Schmidt, I. K., Shaver, G. R., Solheim, B., Soudzilovskaia, N. A., Stenström, A., Tolvanen, A., Totland, Ø., Wada, N., Welker, J. M., Zhao, X., Brancaleoni, L., Brancaleoni, L., De Beus, M. A. H., Cooper, E. J., Dalen, L., Harte, J., Hobbie, S. E., Hoefsloot, G., Jägerbrand, A., Jonasson, S., Lee, J. A., Lindblad, K., Melillo, J. M., Neill, C., Press, M. C., Rozema, J., and Zielke, M.: Global negative vegetation feedback to climate warming responses of leaf litter decomposition rates in cold biomes, Ecol. Lett., 10, 619–627, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01051.x, 2007.

Cornwell, W. K., Cornelissen, J. H. C., Amatangelo, K., Dorrepaal, E., Eviner, V. T., Godoy, O., Hobbie, S. E., Hoorens, B., Kurokawa, H., Pérez-Harguindeguy, N., Quested, H. M., Santiago, L. S., Wardle, D. A., Wright, I. J., Aerts, R., Allison, S. D., Van Bodegom, P., Brovkin, V., Chatain, A., Callaghan, T. V., Díaz, S., Garnier, E., Gurvich, D. E., Kazakou, E., Klein, J. A., Read, J., Reich, P. B., Soudzilovskaia, N. A., Vaieretti, M. V., and Westoby, M.: Plant species traits are the predominant control on litter decomposition rates within biomes worldwide, Ecol. Lett., 11, 1065–1071, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01219.x, 2008.

Cotrufo, M. F., Wallenstein, M. D., Boot, C. M., Denef, K., and Paul, E.: The Microbial Efficiency-Matrix Stabilization (MEMS) framework integrates plant inputs form stable soil organic matter?, Glob. Chang. Biol., 19, 988–995, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12113, 2013.

Cotrufo, M. F., Soong, J. L., Horton, A. J., Campbell, E. E., Haddix, M. L., Wall, D. H., and Parton, W. J.: Formation of soil organic matter via biochemical and physical pathways of litter mass loss, Nat. Geosci., 8, 776–779, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2520, 2015.

Cotrufo, M. F., Ranalli, M. G., Haddix, M. L., Six, J., and Lugato, E.: Soil carbon storage informed by particulate and mineral-associated organic matter, Nat. Geosci., 12, 989–994, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0484-6, 2019.

Coûteaux, M. M., McTiernan, K. B., Berg, B., Szuberla, D., Dardenne, P., and Bottner, P.: Chemical composition and carbon mineralisation potential of Scots pine needles at different stages of decomposition, Soil Biol. Biochem., 30, 583–595, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0717(97)00169-7, 1998.

Craig, M. E., Turner, B. L., Liang, C., Clay, K., Johnson, D. J., and Phillips, R. P.: Tree mycorrhizal type predicts within-site variability in the storage and distribution of soil organic matter, Glob. Chang. Biol., 24, 3317–3330, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14132, 2018.

Cusack, D. F., Chou, W. W., Yang, W. H., Harmon, M. E., and Silver, W. L.: Controls on long-term root and leaf litter decomposition in neotropical forests, Glob. Chang. Biol., 15, 1339–1355, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01781.x, 2009.

de Vries, F. T. and Caruso, T.: Eating from the same plate? Revisiting the role of labile carbon inputs in the soil food web, Soil Biol. Biochem., 102, 4–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.06.023, 2016.

Dijkstra, F. A. and Cheng, W.: Interactions between soil and tree roots accelerate long-term soil carbon decomposition, Ecol. Lett., 10, 1046–1053, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01095.x, 2007.

Fernandez, C. W. and Kennedy, P. G.: Moving beyond the black-box: Fungal traits, community structure, and carbon sequestration in forest soils, New Phytol., 205, 1378–1380, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13289, 2015.

Fernandez, C. W. and Kennedy, P. G.: Revisiting the “Gadgil effect”: Do interguild fungal interactions control carbon cycling in forest soils?, New Phytol., 209, 1382–1394, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13648, 2016.

Fontaine, S., Barot, S., Barré, P., Bdioui, N., Mary, B., and Rumpel, C.: Stability of organic carbon in deep soil layers controlled by fresh carbon supply, Nature, 450, 277–280, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06275, 2007.

Franco-Correa, M., Quintana, A., Duque, C., Suarez, C., Rodríguez, M. X., and Barea, J. M.: Evaluation of actinomycete strains for key traits related with plant growth promotion and mycorrhiza helping activities, Appl. Soil Ecol., 45, 209–217, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2010.04.007, 2010.

Frey, S. D.: Mycorrhizal fungi as mediators of soil organic matter dynamics, Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. S., 50, 237–259, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110617-062331, 2019.

Gadgil, R. L. and Gadgil, P. D.: Mycorrhiza and litter decomposition, Nature, 233, 133, https://doi.org/10.1038/233133a0, 1971.

García-Palacios, P., Maestre, F. T., Kattge, J., and Wall, D. H.: Climate and litter quality differently modulate the effects of soil fauna on litter decomposition across biomes, Ecol. Lett., 16, 1045–1053, https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12137, 2013.

García-Palacios, P., Shaw, E. A., Wall, D. H., and Hättenschwiler, S.: Temporal dynamics of biotic and abiotic drivers of litter decomposition, Ecol. Lett., 19, 554–563, https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12590, 2016.

Gholz, H. L., Wedin, D. A., Smitherman, S. M., Harmon, M. E., and Parton, W. J.: Long-term dynamics of pine and hardwood litter in contrasting environments: Toward a global model of decomposition, Glob. Chang. Biol., 6, 751–765, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000.00349.x, 2000.

Gui, H., Purahong, W., Hyde, K. D., Xu, J., and Mortimer, P. E.: The arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Funneliformis mosseae alters bacterial communities in subtropical forest soils during litter decomposition, Front. Microbiol., 8, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01120, 2017.

Haario, H., Saksman, E., and Tamminen, J.: An Adaptive Metropolis Algorithm, Bernoulli, 7, 223, https://doi.org/10.2307/3318737, 2001.

Hobbie, S. E.: Temperature and plant species control over litter decomposition in Alaskan tundra, Ecol. Monogr., 66, 503–522, https://doi.org/10.2307/2963492, 1996.

Huang, W., van Bodegom, P. M., Viskari, T., Liski, J., and Soudzilovskaia, N. A.: Data and code for Yasso_Myco modelling, Zenodo [data set, code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5579682, 2021.

IPCC: 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Prepared by the National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme, edited by: Eggleston, H. S., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T., and Tanabe, K., Published: IGES, Japan, ISBN 4-88788-032-4, 2016.

IPCC: 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, edited by: Calvo Buendia, E., Tanabe, K., Kranjc, A., Baasansuren, J., Fukuda, M., Ngarize S., Osako, A., Pyrozhenko, Y., Shermanau, P., and Federici, S., Published: IPCC, Switzerland, ISBN 978-4-88788-232-4, 2019.

Johnson, N. C., Hoeksema, J. D., Bever, J. D., Chaudhary, V. B., Gehring, C., Klironomos, J., Koide, R., Miller, R. M., Moore, J., Moutoglis, P., Schwartz, M., Simard, S., Swenson, W., Umbanhowar, J., Wilson, G., and Zabinski, C.: From lilliput to brobdingnag: Extending models of mycorrhizal function across scales, Bioscience, 56, 889–900, https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[889:FLTBEM]2.0.CO;2, 2006.

Kalbitz, K., Schmerwitz, J., Schwesig, D., and Matzner, E.: Biodegradation of soil-derived dissolved organic matter as related to its properties, Geoderma, 113, 273–291, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7061(02)00365-8, 2003.

Kersters, K., De Vos, P., Gillis, M., Swings, J., Vandamme, P., and Stackebrandt, E.: Introduction to the Proteobacteria, in The Prokaryotes, 3rd edn., Volume 5, Proteobacteria: Alpha and Beta Subclasses, edited by: Dworkin, M., Falkow, S., Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K. H., and Stackebrandt, E., Springer New York, New York, NY, 3–37, https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-30745-1_1 2006.

Langley, J. A. and Hungate, B. A.: Mycorrhizal controls on belowground litter quality, Ecology, 84, 2302–2312, https://doi.org/10.1890/02-0282, 2003.

Leake, J., Johnson, D., Donnelly, D., Muckle, G., Boddy, L., and Read, D.: Networks of power and influence: the role of mycorrhizal mycelium in controlling plant communities and agroecosystem functioning, Can. J. Bot., 82, 1016–1045, https://doi.org/10.1139/b04-060, 2004.

Liang, C., Schimel, J. P., and Jastrow, J. D.: The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage, Nat. Microbiol., 2, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.105, 2017.

Lindahl, B. D. and Tunlid, A.: Ectomycorrhizal fungi – potential organic matter decomposers, yet not saprotrophs, New Phytol., 205, 1443–1447, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13201, 2015.

Liski, J., Palosuo, T., Peltoniemi, M., and Sievänen, R.: Carbon and decomposition model Yasso for forest soils, Ecol. Model., 189, 168–182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.005, 2005.

Mambelli, S., Bird, J. A., Gleixner, G., Dawson, T. E., and Torn, M. S.: Relative contribution of foliar and fine root pine litter to the molecular composition of soil organic matter after in situ degradation, Org. Geochem., 42, 1099–1108, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2011.06.008, 2011.

McClaugherty, C. A., Pastor, J., Aber, J. D., and Melillo, J. M.: Forest Litter Decomposition in Relation to Soil Nitrogen Dynamics and Litter Quality, Ecology, 66, 266–275, https://doi.org/10.2307/1941327, 1985.

Nicolás, C., Martin-Bertelsen, T., Floudas, D., Bentzer, J., Smits, M., Johansson, T., Troein, C., Persson, P., and Tunlid, A.: The soil organic matter decomposition mechanisms in ectomycorrhizal fungi are tuned for liberating soil organic nitrogen, ISME J., 13, 977–988, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0331-6, 2019.

Nuccio, E. E., Hodge, A., Pett-Ridge, J., Herman, D. J., Weber, P. K., and Firestone, M. K.: An arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus significantly modifies the soil bacterial community and nitrogen cycling during litter decomposition, Environ. Microbiol., 15, 1870–1881, https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.12081, 2013.

Nyawira, S. S., Nabel, J. E. M. S., Brovkin, V., and Pongratz, J.: Input-driven versus turnover-driven controls of simulated changes in soil carbon due to land-use change, Environ. Res. Lett., 12, 084015, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7ca9, 2017.

Offre, P., Pivato, B., Siblot, S., Gamalero, E., Corberand, T., Lemanceau, P., and Mougel, C.: Identification of bacterial groups preferentially associated with mycorrhizal roots of Medicago truncatula, Appl. Environ. Microb., 73, 913–921, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02042-06, 2007.

Orwin, K. H., Kirschbaum, M. U. F., St John, M. G., and Dickie, I. A.: Organic nutrient uptake by mycorrhizal fungi enhances ecosystem carbon storage: A model-based assessment, Ecol. Lett., 14, 493–502, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01611.x, 2011.

Ostle, N. J., Smith, P., Fisher, R., Ian Woodward, F., Fisher, J. B., Smith, J. U., Galbraith, D., Levy, P., Meir, P., McNamara, N. P., and Bardgett, R. D.: Integrating plant-soil interactions into global carbon cycle models, J. Ecol., 97, 851–863, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01547.x, 2009.

Palosuo, T., Liski, J., Trofymow, J. A., and Titus, B. D.: Litter decomposition affected by climate and litter quality – Testing the Yasso model with litterbag data from the Canadian intersite decomposition experiment, Ecol. Model., 189, 183–198, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.006, 2005.

Parton, W., Silver, W. L., Burke, I. C., Grassens, L., Harmon, M. E., Currie, W. S., King, J. Y., Adair, E. C., Brandt, L. A., Hart, S. C., and Fasth, B.: Global-Scale Similarities in Nitrogen Release Patterns During Long-Term Decomposition, Science, 315, 361–364, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1134853, 2007.

Paterson, E., Osler, G., Dawson, L. A., Gebbing, T., Sim, A., and Ord, B.: Labile and recalcitrant plant fractions are utilised by distinct microbial communities in soil: Independent of the presence of roots and mycorrhizal fungi, Soil Biol. Biochem., 40, 1103–1113, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.12.003, 2008.

Phillips, R. P., Brzostek, E., and Midgley, M. G.: The mycorrhizal‐associated nutrient economy: a new framework for predicting carbon–nutrient couplings in temperate forests, New Phytol., 199, 41–51, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12221, 2013.

Pongratz, J., Dolman, H., Don, A., Erb, K. H., Fuchs, R., Herold, M., Jones, C., Kuemmerle, T., Luyssaert, S., Meyfroidt, P., and Naudts, K.: Models meet data: Challenges and opportunities in implementing land management in Earth system models, Glob. Chang. Biol., 24, 1470–1487, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13988, 2018.

Rajala, T., Peltoniemi, M., Hantula, J., Mäkipää, R., and Pennanen, T.: RNA reveals a succession of active fungi during the decay of Norway spruce logs, Fungal Ecol., 4, 437–448, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funeco.2011.05.005, 2011.

Read, D. J. and Perez-Moreno, J.: Mycorrhizas and nutrient cycling in ecosystems – a journey towards relevance?, New Phytol., 157, 475–492, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00704.x, 2003.

Rineau, F., Shah, F., Smits, M. M., Persson, P., Johansson, T., Carleer, R., Troein, C., and Tunlid, A.: Carbon availability triggers the decomposition of plant litter and assimilation of nitrogen by an ectomycorrhizal fungus, ISME J., 7, 2010–2022, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.91, 2013.

Running, S. W., Nemani, R. R., Heinsch, F. A., Zhao, M., Reeves, M., and Hashimoto, H.: A continuous satellite-derived measure of global terrestrial primary production, Bioscience, 54, 547–560, https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0547:ACSMOG]2.0.CO;2, 2004.

See, C. R., Fernandez, C. W., Conley, A. M., DeLancey, L. C., Heckman, K. A., Kennedy, P. G., and Hobbie, S. E.: Distinct carbon fractions drive a generalisable two-pool model of fungal necromass decomposition, Funct. Ecol., 35, 796–806, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13728, 2021.

Shi, M., Fisher, J. B., Brzostek, E. R., and Phillips, R. P.: Carbon cost of plant nitrogen acquisition: global carbon cycle impact from an improved plant nitrogen cycle in the Community Land Model, Glob. Chang. Biol., 22, 1299–1314, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13131, 2016.

Smith, G. R. and Wan, J.: Resource-ratio theory predicts mycorrhizal control of litter decomposition, New Phytol., 223, 1595–1606, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15884, 2019.

Sokol, N. W., Sanderman, J., and Bradford, M. A.: Pathways of mineral-associated soil organic matter formation: Integrating the role of plant carbon source, chemistry, and point of entry, Glob. Chang. Biol., 25, 12–24, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14482, 2019.

Soudzilovskaia, N. A., Heijden, M. G. A. Van Der, Cornelissen, J. H. C., Makarov, M., Onipchenko, V. G., Maslov, M. N., Akhmetzhanova, A. A., and van Bodegom, P. M.: Quantitative assessment of the differential impacts of arbuscular and ectomycorrhiza on soil carbon cycling Methods Quantitative assessment of the differential impacts of arbuscular and ectomycorrhiza on soil carbon cycling, New Phytol., 208, 280–293, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13447, 2015.

Soudzilovskaia, N. A., van Bodegom, P. M., Terrer, C., van't Zelfde, M., McCallum, I., McCormack, M. L., Fisher, J. B., Brundrett, M. C., de Sá, N. C., and Tedersoo, L.: Global mycorrhizal plant distribution linked to terrestrial carbon stocks, Nat. Commun., 10, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13019-2, 2019.

Steidinger, B. S., Crowther, T. W., Liang, J., Van Nuland, M. E., Werner, G. D. A., Reich, P. B., Nabuurs, G. J., De-Miguel, S., Zhou, M., Picard, N., Herault, B., Zhao, X., Zhang, C., Routh, D., Peay, K. G., and GFBI consortium: Climatic controls of decomposition drive the global biogeography of forest-tree symbioses, Nature, 569, 404–408, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1128-0, 2019

Sulman, B. N., Phillips, R. P., Oishi, A. C., Shevliakova, E., and Pacala, S. W.: Microbe-driven turnover offsets mineral-mediated storage of soil carbon under elevated CO2, Nat. Clim. Chang., 4, 1099–1102, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2436, 2014.

Terrer, C., Vicca, S., Hungate, B. A., Phillips, R. P., and Prentice, I. C.: Mycorrhizal association as a primary control of the CO2 fertilization effect, Science, 353, 72–74, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf4610, 2016.

Todd-Brown, K. E. O., Hopkins, F. M., Kivlin, S. N., Talbot, J. M., and Allison, S. D.: A framework for representing microbial decomposition in coupled climate models, Biogeochemistry, 109, 19–33, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-011-9635-6, 2012.

Todd-Brown, K. E. O., Randerson, J. T., Post, W. M., Hoffman, F. M., Tarnocai, C., Schuur, E. A. G., and Allison, S. D.: Causes of variation in soil carbon simulations from CMIP5 Earth system models and comparison with observations, Biogeosciences, 10, 1717–1736, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-1717-2013, 2013.

Treseder, K. K. and Allen, M. F.: Direct nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: A model and field test, New Phytol., 155, 507–515, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00470.x, 2002.

Treseder, K. K., Marusenko, Y., Romero-Olivares, A. L., and Maltz, M. R.: Experimental warming alters potential function of the fungal community in boreal forest, Glob. Chang. Biol., 22, 3395–3404, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13238, 2016.

Trofymow, J. A.: The Canadian Institute Decomposition Experiment (CIDET): project and site establishment report, Trofymow, J. A., and the CIDET Working Group, Victoria, B. C., Information Report BC-X-378, 126 p., ISBN 0-662-26870-9, 1998.

Trumbore, S.: Carbon respired by terrestrial ecosystems – Recent progress and challenges, Glob. Chang. Biol., 12, 141–153, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01067.x, 2006.

Tuomi, M., Thum, T., Järvinen, H., Fronzek, S., Berg, B., Harmon, M., Trofymow, J. A., Sevanto, S., and Liski, J.: Leaf litter decomposition-Estimates of global variability based on Yasso07 model, Ecol. Model., 220, 3362–3371, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2009.05.016, 2009.

Tuomi, M., Rasinmäki, J., Repo, A., Vanhala, P., and Liski, J.: Soil carbon model Yasso07 graphical user interface, Environ. Model. Softw., 26, 1358–1362, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2011.05.009, 2011a.

Tuomi, M., Laiho, R., Repo, A., and Liski, J.: Wood decomposition model for boreal forests, Ecol. Model., 222, 709–718, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2010.10.025, 2011b.