the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The biogeographic pattern of microbial communities inhabiting terrestrial mud volcanoes across the Eurasian continent

Tzu-Hsuan Tu

Li-Ling Chen

Yi-Ping Chiu

Li-Hung Lin

Li-Wei Wu

Francesco Italiano

J. Bruce H. Shyu

Seyed Naser Raisossadat

Terrestrial mud volcanoes (MVs) represent the surface expression of conduits tapping fluid and gas reservoirs in the deep subsurface. Such plumbing channels provide a direct, effective means to extract deep microbial communities fueled by geologically produced gases and fluids. The drivers accounting for the diversity and composition of these MV microbial communities, which are distributed over a wide geographic range, remain elusive. This study characterized the variation in microbial communities in 15 terrestrial MVs across a distance of ∼ 10 000 km on the Eurasian continent to test the validity of distance control and physiochemical factors in explaining biogeographic patterns. Our analyses yielded diverse community compositions with a total of 28 928 amplicon sequence variances (ASVs) taxonomically assigned to 73 phyla. While no true cosmopolitan member was found, ∼ 85 % of ASVs were confined within a single MV. Community variance between MVs appeared to be higher and more stochastically controlled than within MVs, generating a slope of the distance–decay relationship exceeding those for marine seeps and MVs as well as seawater columns. For comparison, physiochemical parameters explained 12 % of community variance, with the chloride concentration being the most influential factor. Overall, the apparent lack of fluid exchange renders terrestrial MVs a patchy habitat, with microbiomes diverging stochastically with distance and consisting of dispersal-limited colonists that are highly adapted to the local environmental context.

- Article

(2619 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(4797 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Microbial biogeography describes the distribution of microbial taxa over space and time, providing insights into the fundamental processes generating and governing diversity (Lomolino et al., 2006). Four nonexclusive processes – selection, drift, dispersal, and mutation – have been proposed to account for various microbial biogeographical patterns (Hanson et al., 2012). The selection process is generally regarded as deterministic and involves nonrandom, niche-based mechanisms, including environmental filtering (e.g., pH, temperature, salinity, and geochemical or redox variations) and various biological interactions (e.g., competition, mutualisms, predation, and trade-offs) (Ning et al., 2019). Therefore, the distribution pattern of microbial diversity is controlled by the response of community members to environmental parameters (Comte et al., 2016; Power et al., 2018). Such selection factors could have led to the establishment of a variety of core microbiomes inhabiting distinct environments, such as soil, sediment, aquatic, and vent ecosystems (Orcutt et al., 2011; Ruff et al., 2015), or organized spatially as in a gradient and, thus, autocorrelated (Hanson et al., 2012; Ranjard et al., 2013). The drift process is caused by chance events (e.g., differences in taxa associated with birth and death events), differentiating microbial composition over space in neutral theory (Slatkin, 1993; Condit et al., 2002). Microbial dispersal is defined as the physical movement of cells between two locations and successful establishment at the receiving location (Hanson et al., 2012). Due to the dispersal limitation, chance events at one location would influence nearby compositions. Therefore, the interaction between drift and dispersal limitation would generate a distance–decay relationship (DDR) (Hutchison and Templeton, 1999) in which the community dissimilarity increases with distance. Finally, gene duplications, mutations, and other processes produce new genes and alleles that reshape the DDR by increasing local genetic diversity across all locations. Although these latter three processes generate community diversity patterns indistinguishable from random chance alone or are considered a stochastic consequence (Ning et al., 2019), they are also nonexclusive and interact with deterministic processes. Dissecting the contribution of individual processes and governing factors remains a challenging issue (Hanson et al., 2012).

Mud volcanoes (MVs) represent a unique ecosystem for investigating microbial biogeographic patterns when compared with aquatic, soil, and sediment ecosystems on or near the land surface or seafloor. This uniqueness stems from the fact that MV genesis is tightly linked with the plumbing of fluids and sediments from deep reservoirs through fracture networks often extending to a depth of several kilometers (Mazzini and Etiope, 2017). Because advection dominates over diffusion for fluid transport, relatively rapid migration can occur with minimal alterations of geochemical characteristics and even microbial communities of fluids/muds emanating from a mud cone or pool (Dimitrov, 2002; Chen et al., 2020). Therefore, MVs provide a direct, effective means to recover deep microbial communities. Meanwhile, the export of reducing compounds and rapid deposition of sediments enable MV sediments to be highly reduced and confined to a limited spatial extent (from tens of centimeters to kilometers) (Chang et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2012; Mazzini and Etiope, 2017). Such physicochemical characteristics generate localized, strong redox gradients and host abundant microorganisms with identities distinct from adjacent environments or overlying seawater (Wang et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2018), rendering MVs globally distributed, unique biological hotspots fueled by geologically produced gases and fluids. A recent survey has demonstrated the predominance of few cosmopolitan taxa with a physiological preference for methane or hydrocarbons in marine MVs (Ruff et al., 2015). This line of evidence, combined with the observed DDR, suggests that both dispersal and selection exert a profound influence on shaping community compositions and structures. In contrast with the aid of dispersal through seawater circulation in their marine counterparts, terrestrial MVs have an even more limited connection with one another. For a geographic scale larger than tens of kilometers, dispersal through groundwater transport would be essentially absent. This limitation, combined with enormous oxidative power driven by atmospheric oxygen (Lin et al., 2018), renders terrestrial MVs ideal for investigating whether any biogeographic pattern imposed by geographic isolation and environmental contexts emerges. In addition to various spatial scales, environmental and redox contexts vary substantially along a vertical scale. The variance of beta diversity and its controlling mechanism on both spatial and vertical scales remains poorly constrained.

This study aims to determine prokaryotic community compositions and structures associated with terrestrial MVs and to constrain the underlying mechanisms by examining the control of deterministic and stochastic processes on community variations over a spatial scale (up to ∼ 10 000 km) across the Eurasian continent and a vertical scale (up to ∼ 1.5 m) over a redox transition. Community compositions based on 16S rRNA gene sequences and metadata for cored sediments from 15 MVs were synthesized and analyzed to assess the control of qualitative stochasticity on community variations at different spatial and vertical scales using various statistical approaches and ecological metrics. Moreover, while cosmopolitan members with significant dispersal capability and specific colonists highly adapted to local environmental contexts were identified, distribution patterns of members potentially possessing sulfur or methane metabolisms were also revealed. These results were compared with marine data to draw the framework and characteristics shared between terrestrial and marine MV ecosystems. This work represents the most extensive microbial ecology study to date on terrestrial MVs at a continental scale.

2.1 Sampled MVs and data source

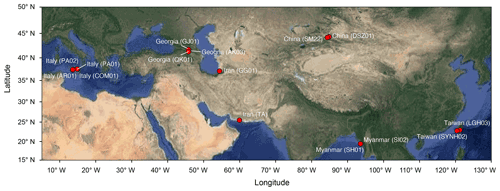

Muddy fluids from bubbling pools and sediment cores from the adjacent mud platform were retrieved from MVs across the Eurasian continent during the period from 2011 to 2013 (Fig. 1; Table S1 in the Supplement) for geochemical (n=9) and molecular analyses (n=13). Detailed sample collection, processing, and preservation are described in the Supplement. Data (Tu et al., 2022a) obtained in this study were merged with companion geochemical data for 4 MVs in Italy (AR01, COM01, PA01, and PA02; Chiu, 2015) and with geochemical and molecular data for 2 MVs in Taiwan (LGH03 and SYNH02; Tu et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2018) to generate a total of 136 sample sets for 16 cores from 15 MVs.

2.2 Geochemical analyses

Concentrations of methane were analyzed using a 6890N gas chromatograph (GC; Agilent Technologies, USA). Carbon isotope compositions of methane were measured with a MAT 253 isotope ratio mass spectrometer connected to a GC IsoLink (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Chloride and sulfate concentrations in porewater were analyzed using an ICS-3000 ion chromatograph (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Concentrations of particulate total organic carbon (TOC), total inorganic carbon (TIC), total nitrogen (TN), and total sulfur (TS) were determined by an elemental analyzer (MICRO cube, Elementar, Germany). Detailed methods for these analyses are described in the Supplement.

2.3 Microbial community analyses

Crude DNA for 16S rRNA gene analyses was extracted from fluids/sediments using a PowerSoil DNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Germany). Bubbling fluids (if available) and sediments distributed across geochemical transition were selected for DNA extraction. These samples are representative of communities inhabiting the subsurface source region (for bubbling fluids) or subject to the redox gradient developed after the sediment deposition (cored sediments in the adjacent mud platform). DNA extracts were obtained and stored at −80 ∘C for subsequent analyses.

Amplicons for 16S rRNA genes were generated from polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) using the universal primers targeting both bacterial and archaeal communities and were sequenced on the Illumina platform. Sequences were analyzed using mothur and QIIME 2 software (Schloss et al., 2009; Bolyen et al., 2019). Denoised reads were assembled to full sequences, aligned, and taxonomically assigned against the Silva v.132 reference set using mothur. Detailed schemes for PCR, sequencing, and sequence processing are described in the Supplement. The obtained sequences were deposited in GenBank with the accession number PRJNA560274.

2.4 Statistical analyses

Detailed methods for the statistical analyses are described in the Supplement.

2.4.1 Microbial community analyses

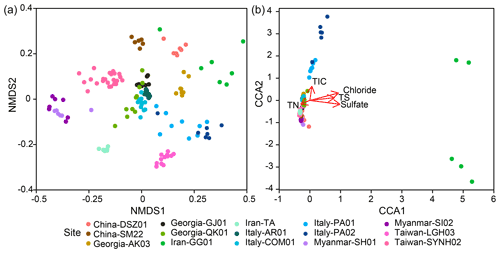

Sequence data were first rarefied to 9413 sequences per sample through 100 sequence random resampling (without replacement) of the original amplicon sequence variant (ASV) table to account for the difference in sequencing depth for the calculation of alpha diversity indices (Hill, 1973). For the beta diversity calculation, the entire ASV table was used and normalized using the cumNorm function embedded within metagenomeSeq in R (Paulson et al., 2013). The method considers the sum of ASVs and their quantile distribution for each sample by adjusting the sequence number for individual ASVs while keeping the total ASVs the same before and after the normalization. The method does not sacrifice the sample diversity contributed from rare ASVs, thereby providing a better assessment of the community variation across different spatial scales or controlled by localized environmental factors. The dissimilarity matrix between samples was computed using the Bray–Curtis method (Bray and Curtis, 1957; Ranjard et al., 2013) and visualized through the ordination of nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS). Among the synthesized 136 samples, 126 samples with concentrations of chloride, sulfate, methane, TN, TS, TIC, and TOC were used for constrained correspondence analysis (CCA), which aims to elucidate the relationship between microbial community compositions and geochemical variables.

2.4.2 Habitat similarities

Habitat similarities were calculated from the Euclidean distances between paired samples with the available concentrations of chloride, sulfate, methane, TN, TS, TIC, and TOC using the following equation (Ranjard et al., 2013):

where Ed is the habitat similarity, Eucd is the Euclidean distance, and Eucmax is the maximum distance between MVs.

2.4.3 Distance decay relationships (DDRs)

To assess the DDR, pairwise community similarities were calculated using the Sørensen–Dice index (Dice, 1945). The pairwise similarity was transformed on a logarithmic scale to enhance the linear fitting (Nekola and White, 1999) using the following equation:

where Scom is the pairwise similarity in community composition, D is the distance between two samples, a is the intercept, and β is the slope. The distance between samples was aggregated from two categories for samples in separate cores (geographic distance) or within the same cores (vertical distance).

2.4.4 Normalized stochasticity ratios (NSTs)

NSTs were calculated to assess the stochasticity of community variations within each category of samples using 50 % as a threshold for either more stochastic (>50 %) or deterministic (<50 %) control (Ning et al., 2019). The analysis was conducted using the obtained ASV table by first categorizing all samples into “bubbling fluid”, “surface sediment”, and “within-MV sediment”, each representing source communities, source communities subject to minor surface impact, or communities potentially altered by localized geochemical/redox context. The categorization addressed the scenarios in which the variation pattern for source communities with/without minor impact of the surface process (for bubbling fluid and surface sediment) is dependent on distance separation as well as scenarios in which the variation pattern for localized communities (for within-MV sediment) is dependent on a specific environmental context within individual MVs. The NST was calculated using the NST package developed by Ning et al. (2019) based on the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity (NSTBray), Jaccard distance (NSTJaccard), and phylogenetic distance (pNST) between pairwise communities within each category of samples, following the recommendation of the developers.

3.1 Physical and geochemical characteristics

The pairwise distance between samples ranged from 2.5 to 160 cm within cores and from 0.005 to 9924 km between cores (Fig. 1). Geochemical profiles of porewater showed various characteristics related to abiotic and microbial processes. Chloride concentrations varied highly among MVs (ranging between 82 mM at SI02 in Myanmar and 4890 mM at GG01 in Iran) and generally decreased with increasing depth within individual cores (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). Sulfate concentrations ranged from below the detectable level at SM22, AK03, GJ01, TA, PA01, PA02, and LGH03 to 288 mM at GG01, with most data clustering between 0.5 and 2 mM (Fig. S1). Methane concentrations ranged between 0.006 mM (PA02) and 3.98 mM (SYMH02C4), with most data clustering between 0.2 and 1 mM (Fig. S2). The δ13C values of methane spanned from −58 ‰ to −35 ‰ and exhibited a trend opposite to that of the methane concentration. The molar ratios of methane over ethane and propane (C1 (methane)(C2 (ethane) + C3 (propane))) were variable and ranged from 22 (SI02) to approximately 1200 (AR01 and COM01; Fig. S3). Detailed porewater characteristics are provided in the Supplement.

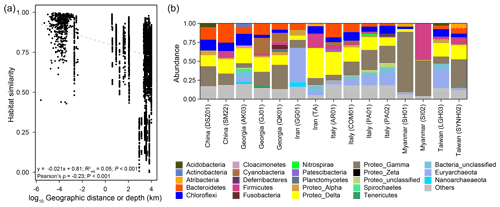

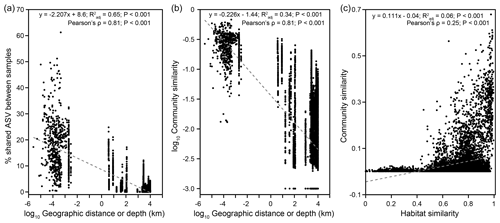

Pairwise comparisons between samples within individual cores yielded a habitat similarity (Ed) ranging between 0.42 and 1.0 (for data points with a distance of 2.5 to 160 cm in Fig. 2a). These narrow-ranging indices were generally higher than those for samples between cores (for data points with a distance greater than 160 cm in Fig. 2a). Inspection of the data sets, however, demonstrated a contrasting pattern between some MVs. For example, the geographic distances between MVs in Italy and Taiwan were the highest among all MV pairs. Habitat similarities between AR01 and COM01 and between SYNH02 and LGH03 were greater than 0.96. In contrast, habitat similarities between GG01 and other MVs were low, even though the geographic distances were short. Overall, habitat similarities were not significantly correlated with vertical distance but horizontal distance (P<0.001) (Fig. 2a).

3.2 Community structures and compositions

A total of 24 617 bacterial and 4311 archaeal ASVs, representing 181 classes (157 bacterial and 24 archaeal) within 73 phyla, were recovered. The observed ASVs for individual samples ranged between 58 and 1462, with an average value of 449 ± 250 when singletons (presence of one sequence for an ASV at only one depth) were included. The trends in diversity indices revealed a similar pattern (Fig. S4). The lowest values of alpha diversity indices occurred for SI02 and SH01 in Myanmar, whereas the highest values were found for AR01 in Italy. Diversity at the ASV level was fully captured for individual cores but was not sufficiently recovered by taking all cores as a whole (Fig. S5 in the Supplement).

The dominant phyla and subdivisions of Proteobacteria (>5 % of the total reads) included Firmicutes (6.0 %), Chloroflexi (7.6 %), Euryarchaeota (8.6 %), Bacteroidetes (9.5 %), Deltaproteobacteria (18.6 %), and Gammaproteobacteria (21.4 %). The majority of bacterial reads were assigned to the orders Betaproteobacteriales (4.2 %), Desulfuromonadales (6.1 %), and Desulfobacterales (7.1 %). Most sequences belonging to these three orders were related to the families Hydrogenophilaceae (2.9 %), Desulfuromonadaceae (3.4 %), and Desulfobulbaceae (4.5 %), respectively. The two dominant genera, Thiobacillus (Hydrogenophilaceae) and Desulfurivibrio (Desulfobulbaceae), constituted 2.9 % and 3.2 % of the total reads, respectively. For comparison, the majority of archaeal reads were assigned to the orders Halobacteriales (2.8 %) within Halobacteria and Methanosarcinales (4.3 %) within Methanomicrobia. While most sequences assigned to Halobacteria were related to the families Halobacteriaceae (1 %) and Haloferacaceae (1.1 %), the predominant sequences within Methanomicrobia were affiliated with anaerobic methanotrophs (ANME) 2a (3.2 %). Among the 28 928 ASVs, 5 out of the 10 most abundant ASVs were affiliated with the genus Thiobacillus (0.4 %–0.7 % of the total reads).

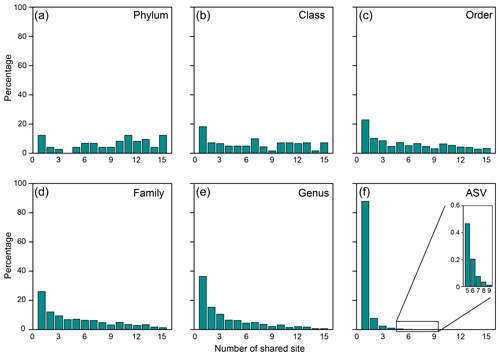

Of 73 phyla obtained, 9 were found in all cores, whereas another 9 were restricted to one core (Figs. 2b, 3a). Cosmopolitan phyla were more abundant than endemic ones, with the exceptions for GG01, SYNH02, and SH01. Proteobacteria appears to be the only phylum present in all 136 samples (and all MVs) and is the most abundant phylum in nearly all MVs (except for GG01 and SI02). While the remaining eight phyla were present in all MVs, they were absent in few samples and occurred in 124 to 135 samples. The proportions of cosmopolitan taxonomic units decreased from the level of phylum to ASV (Fig. 3b–e). Among the detected 1214 genera, the genus Desulfurivibrio was the most abundant and was present in 98 of the 136 samples. Two other prevalent genera were detected in 126 samples and taxonomically assigned to the unclassified genera related to Anaerolineae within Chloroflexi and to Gammaproteobacteria, respectively.

Figure 3Proportions of specific taxonomical units shared between the number of MVs for the (a) phylum, (b) class, (c) order, (d) family, (e) genus, and (f) ASV.

At the ASV level, no truly cosmopolitan ASVs were identified (Fig. 3f). Pairwise comparisons yielded a shared 0 %–15.4 % and 0 %–51.3 % of the ASVs between MVs and between samples, respectively. In particular, the communities at SI02 completely differed from AK03, SM22, and LGH03. The most widely distributed ASVs were present in nine MVs (Fig. 3f, Table S2) and constituted only 0.4 % of the total sequences. Their sequences were affiliated with either the unclassified genus of Desulfuromonadaceae or Desulfotignum. Compared with the pattern based on higher taxonomic units (between genus and class), the ASVs confined at one MV and less than/equal to three MVs constituted 85 % and 99 % of the total ASVs, respectively, and were taxonomically diverse and unevenly abundant. Detailed information on the 10 most abundant ASVs is given in Table S2.

Within individual cores, the number of phyla ranged from 12 (SI02) to 62 (PA01). Although 16.1 % (PA01) to 58.5 % (AR01) of detected phyla were shared between samples within individual cores, 6.3 %–40 % of phyla were restricted to single samples. Similar to the pattern for phyla, the lowest number of genera occurred for SI02 (52), whereas the highest number was present for PA01 (550). In addition, 3.4 % (GG01) to 26.5 % (AR01) of genera and up to 13.2 % (SI02) of ASVs were shared within individual cores. In contrast, up to 49.9 % (PA02) of genera and 83.9 % (GG01) of ASVs were restricted to a single sample. Overall, community dissimilarities appear to be more pronounced between samples from distinct MVs than from within the individual MVs, indicating a high degree of endemism (Fig. 4a).

3.3 Environmental effects

Multiple regression analysis yielded that methane, TN, and TIC concentrations had meaningful contributions (summed to be 18.8 %) to the Shannon index (Table S3), with TIC being the most influential one (13.4 % linear regression, P<0.001; Table S4). Similarly, the TIC concentration was also significantly correlated with the Shannon index (Pearson's coefficient: , P<0.001; Fig. S6).

Community dissimilarities were correlated more strongly with chloride (Mantel: ρ=0.45, P<0.001) than with sulfate (Mantel: ρ=0.26, P<0.001) concentrations and other geochemical parameters (Table S5). Permutational multivariate analysis of variance in community assemblage showed that TIC (3.6 %) and TN (3.1 %) concentrations had the highest contribution to the beta diversity, followed by sulfate (2.9 %) and chloride (2.6 %), TOC (2.4 %), TS (2.0 %), and methane concentrations (0.9 %) (P<0.001; Table S6).

The CCA yielded that the eight environmental parameters combined (sample depth as well as concentrations of chloride, sulfate, and methane, TIC, TOC, TN, and TS) explained 12 % of community dissimilarity (Fig. 4b). Of these factors, chloride, sulfate, TIC, TS, and TN significantly contributed to the overall differences in community composition. For communities within individual cores, a combination of various factors described above was significantly correlated with community dissimilarities (Fig. S7). For example, the depth factor was significant for the community dissimilarities within 11 out of 16 individual cores. In contrast, the chloride factor was only significant for the community dissimilarities within two individual cores (QK01 and SYNH02C4). Finally, none of the selected factors were significantly correlated with the community dissimilarities within TA01, SH01, SI01, SM22, and LGH03.

3.4 DDR and NST patterns

Community structure varied widely across a scale of 9924 km (Bray–Curtis: RANOSIM=0.967, P<0.001; Fig. S8). Both the proportions of shared ASVs and community similarities significantly decreased with increasing geographical distance (Mantel: , P<0.001), indicating a significant DDR with a slope coefficient, , of 0.226 (P<0.001) (Fig. 5a, b). If only communities from individual cores were considered, a DDR (Mantel: ρ=0.65, P<0.001) with an even higher |β| value of 0.241 was obtained (Fig. S9b). Close examinations revealed that similarities of communities distributed within individual cores were not significantly correlated with distance (or depth; Fig. S9d, e). Such variations in the DDR reveal that community compositions were controlled by different mechanisms at vertical versus horizontal scales. Furthermore, the NSTBray values varied from 100 % for bubbling fluid and for surface sediment to between 1 % and 63 % for within-MV sediment (Table S1). For the within-MV sediment category, the NSTBray values for 12 out of 15 MVs were less than 50 % (Table S1). For comparison, the same NSTJaccard values for bubbling fluid and surface sediment as well as a similar NSTJaccard range for within-MV sediment (1 %–61 %) were obtained (Table S1). The pattern for pNST values resembled those for NSTBray and NSTJaccard values (Table S1 in the Supplement).

4.1 Environmental selection in terrestrial mud volcanoes

This study recovered diverse and complexly structured microbial communities in terrestrial MVs distributed across the Eurasian continent. Further linear regression analyses yielded that the Shannon index was mostly controlled by TIC (Fig. S6, Tables S3–S4). Both the Mantel test and CCA revealed that community similarities were strongly influenced by chloride, sulfate, TIC, and TS concentrations (Fig. 4b, Table S5) and correlated with habitat similarities (Figs. 5c, S10). To explore the controlling factors for community variance further, the individual factors stated above were addressed at the community level first, followed by at the level of specific, abundant lineage.

Salinity has been identified as the primary factor shaping the distribution of microorganisms (Or et al., 2007). Because chloride is inert to most catabolic and abiotic reactions, any correlation between community (Or et al., 2007) index and chloride concentration could have reflected the physiological response or tolerance to salinity variation (Or et al., 2007) related to evaporation and evaporite dissolution/precipitation. Chloride concentrations measured in this study spanned over a broad range between 82 and 4890 mM. While the community similarity was shaped by chloride (Fig. 4b, Table S5), the abundances of specific lineages, including Haloferacaceae and Halobacteriaceae within Halobacteria, were also significantly correlated with the chloride concentrations (Fig. S10). In particular, the order Halobacteria, detected in 11 out of the 15 investigated MVs, was highly enriched in hypersaline MVs (GG01, PA01, and PA02) where the chloride concentrations reached up to 4890 mM. Previous culture tests have shown that strains affiliated with this lineage can cope with the stress imposed by high osmotic pressures and low water activities (Grant, 2004). All members of the family Halobacteriaceae grow optimally at chloride concentrations of above 2500 mM (Oren, 2014) and up to 5000 mM (Halobacterium sp. NRC-1) (DasSarma and DasSarma, 2001). In contrast, the abundances of JS1 within Atribacteria and of Hydrogenophilaceae within Proteobacteria were negatively correlated with the chloride concentrations (; Fig. S10). Although these two families were prevalently distributed in all MVs, the correlation pattern suggests their sensitive response to the salinity stress and preference for low salt conditions.

TIC in sedimentary systems represents a pool of biological carbonate remains and authigenic carbonate formed or induced by microbial processes (Zheng et al., 2011) Considering that carbonate fossils are exempt from the preservation of genetic materials during burial diagenesis (Allison and Pye, 1994), the correlation between TIC and community similarity could have been controlled by the composition of heterotrophs and methanotrophs capable of converting organic carbon and methane into dissolved carbonate and eventually to the precipitation of carbonate minerals. Therefore, the presence and concentration of TIC might reflect the microbial capability for the utilization of organic carbon or methane to some degree. In addition to the community variance, the abundances of a variety of families, such as Woesearchaeia, Thiohalorhabdaceae, Marinilabiliaceae, Lentimicrobiaceae, Haloferaceae, Halobacteriaceae, Ectothiorhodospiraceae, Desulfarculaceae, Balneolaceae, and Anaerolineaceae were found to be significantly correlated with the TIC concentrations (Fig. S10). While none of the methanotrophs are related to the lineages described above, previous studies have demonstrated that a large number of strains affiliated with Halobacteriales, Marinilabiliaceae, Lentimicrobiaceae, Desulfarculales, and Anaerolineale are capable of metabolizing various forms of organic carbon (e.g., fatty acids, sugars, amino acids, hydrocarbons, and even short-chain alkanes) (Yamada and Sekiguchi, 2009; McGenity, 2010; Kuever, 2014; McIlroy and Nielsen, 2014; Borrel et al., 2019; Mori et al., 2019). Moreover, metagenomes with 16S rRNA gene sequences affiliated with Woesearchaeota contain genes for starch/sugar utilization, glycolysis, folate C1 metabolism, and fermentation (Liu et al., 2018). The gene pattern further suggests the heterotrophic nature of Woesearchaeota and its potential requirement of metabolic complement from other microorganisms (e.g., acetate-utilizing methanogens). Overall, the physiological characteristics derived from previous cultivation experiments, along with metagenomic data, all demonstrate the prevalence of heterotrophy among these phyla/orders. The positive correlation between their abundances and TIC concentration suggests a connection between carbon utilization and carbonate precipitation. We noted that a similar pattern was not observed for TOC and TN (Table S5). It is likely that the pools of bioavailable and biodegradable TOC and TN only constitute a small fraction of the pool size, thereby rendering TOC and TN less sensitive to the community variance.

Compared with chloride, sulfate concentrations varied at a higher magnitude (coefficient of variation, CV, of 13 %–186 %; Table S7). With the exception of SH01 and SYNH02, the sulfate concentrations were not significantly correlated with the chloride concentrations (Table S7). The decoupling of sulfate from chloride suggests that, in addition to the evaporation or dissolution/precipitation of evaporite minerals, microbially mediated sulfate reduction or oxidation of reduced sulfur plays a role in controlling sulfate abundance. While the sulfate concentrations were significantly correlated with the community similarities (Table S5), abundant sulfur oxidizers and sulfate reducers (such as Hydrogenophilaceae-, Desulfobulbaceae-, and Desulfuromonadaceae-related members; Or et al., 2007) were detected at SI02, SH01, and AR01. In addition, the abundances of sulfur-metabolizing lineages, such as sulfur-oxidizing Thiobacillus members within Hydrogenophilaceae (ρ=0.38, P<0.001) and sulfate-reducing members related to Desulfobulbaceae and Desulfarculaceae (, P<0.001; Fig. S10), were found to be significantly correlated with the sulfate concentrations.

Similar to TIC, TS represents an aggregation of various sulfur-bearing minerals formed through different processes at varying timescales. These pools of minerals include pyrite (or other sulfide minerals) and gypsum precipitated over geological time as well as sulfide minerals (e.g., iron monosulfide and pyrite) produced from microbial sulfate reduction at a contemporary timescale (Halevy et al., 2012). In contrast with marine environments where the sulfate pool is enormous, terrestrial MVs are often devoid of sulfate, unless evaporite is ubiquitous. Therefore, in situ sulfate reduction proceeds with sulfate produced from microbial sulfur oxidation or gypsum dissolution (Canfield, 1989; Yao and Millero, 1996; Weber et al., 2017). In this regard, the correlation between TS and community similarity observed in this study demonstrated that in situ microbial processes played a role in shaping community compositions. Detailed analyses further revealed that the abundances of a variety of families, such as Thiohalorhabdaceae, Balneolaceae, and Haloferaceae, were positively correlated with the TS concentrations (Fig. S10). Among these families, most strains affiliated with Thiohalorhabdaceae can directly metabolize sulfur (Sorokin et al., 2020). In contrast, the abundances of lineages, such as Methanosaetaceae, Marinobacteraceae, Methylomonaceae, and JS1 were negatively correlated with the TS concentrations. Although these lineages have been commonly observed at the sulfate-to-methane transition in marine sediments (Orphan et al., 2001; Inagaki et al., 2006), the correlation pattern suggests their proliferation in sulfur-depleted environments.

Methane has been found to be abundant in most MVs (Etiope et al., 2019), providing an energetic substrate and carbon source for various metabolisms. Its abundances varied substantially (CV of 277 %) and were neither correlated with the chloride concentrations nor community similarities. Previous studies have demonstrated that carbon isotopic compositions and C1(C2 + C3) abundance ratios could be used to distinguish methane produced from methanogenesis from thermal maturation (Whiticar, 1999). Thermogenic hydrocarbon gases generally possess C1(C2 + C3) abundance ratios ranging from 0 to 50 and carbon isotopic compositions of methane greater than −50 ‰ (Claypool and Kvenvolden, 1983), whereas microbial sources generate hydrocarbons with C1(C2 + C3) abundance ratios generally greater than 1000 and carbon isotopic compositions of methane smaller than −60 ‰ (Claypool and Kvenvolden, 1983). Regardless of the production source, microbial methane consumption would impart carbon isotopes of methane, preferentially producing 12C-enriched CO2 or leaving residue methane enriched in 13C.

In this study, rather than community dissimilarity, the abundances of methanogens (members of Methanosaetaceae) were significantly correlated with the methane concentrations (ρ=0.23, P<0.001; Fig. S10). Although both C1(C2 + C3) abundance ratios and carbon isotopic compositions of methane revealed a mixed origin of methane (Figs. S2, S3), the correlation pattern supports a quantitative role of microbial over thermogenic methane production in terrestrial MVs. Furthermore, both aerobic and anaerobic methanotrophs were detected in 11 of the 15 investigated MVs. While these two types of methanotrophs possess contrasting oxygen affinities, they were all distributed from the surface to the bottom of investigated cores. Resembling the findings in the marine setting (Ruff et al., 2015), neither the abundances of the entire ANME (Fig. S10) nor the community dissimilarities were significantly correlated with the methane concentrations. The abundances of the whole ANME and ANME-2a/b were inversely correlated with the carbon isotopic compositions of methane and sulfate concentrations ( and −0.32 for whole ANME, P<0.001; and −0.45 for ANME-2a/b, P<0.001), respectively, which is a pattern consistent with the coupling of methane oxidation with sulfate reduction mediated by ANME-2a/b and Deltaproteobacteria (Knittel and Boetius, 2009). In addition, ANME-2d-related sequences were mostly distributed at LGH03. Previous culture and field studies have shown that ANME-2d-related members can oxidize methane with the reduction of nitrate, iron, and manganese (Beal et al., 2009; Haroon et al., 2013; Ettwig et al., 2016; Scheller et al., 2016). Our findings suggest that anaerobic methanotrophy driven by electron acceptors other than sulfate is not prevalent in terrestrial MVs.

Finally, the factor of depth represents an integration of geochemical variations (e.g., sulfate, methane, and chloride). The counteraction between the downward penetration of atmospheric oxygen and upward migration of reducing methane would presumably result in a steep redox gradient along the depth (Lin et al., 2018), leading to a segregation of distinct niches with community compositions adapted to various redox and geochemical affinities. Indeed, the within-core community similarity was significantly correlated with depth for 11 cores (Fig. S7) and with habitat similarity for all cores (Fig. S9), which is a pattern consistent with what has been reported for marine sediments (Jørgensen et al., 2012; Ruff et al., 2015; Petro et al., 2017).

4.2 Microbial dispersal patterns

A distance–decay trend was identified for geographic distances of up to ∼ 10 000 km (Figs. 1, 2, 5). The deduced value (0.226) was smaller than that for macroorganisms ( = 0.2–0.7) (Nekola and White, 1999), pointing to a higher dispersal rate of microorganisms (Astorga et al., 2012; Zinger et al., 2014). Furthermore, the value resembled those for microbial communities in coastal sediments (Zinger et al., 2014) and was larger than those ( = 0–0.15) for microbial communities in marine seeps and MVs (Ruff et al., 2015) as well as seawater columns (Zinger et al., 2014), suggesting a higher degree of dispersal limitation in terrestrial and transition zone sediments than in marine environments. Our results are in contrast with the biogeographic pattern derived from ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in salt marsh sediments, where dispersal limitation at the local scale contributes to the beta diversity, and no evidence of evolutionary diversification is observed at the continental scale (Martiny et al., 2011). Furthermore, the mean NST values for both bubbling fluid and surface sediment categories were high (100 %) (Table S1). These sample categories represent either deeply sourced communities (for bubbling fluid) or source communities susceptible to the alteration of surface processes (for surface sediment). Considering that most of these MVs are distant from each other (except for SI01 and SH01), fluid exchange and, subsequently, microbial dispersal or exchange between MVs could be exempt. Therefore, the high NST values associated with these two categories suggest that highly stochastic control on community variance is likely linked to the limitation imposed by distance separation. In contrast, the mean NST value for the within-MV sediment category was 32 %. The NST values were <50 % for 12 out of 15 MVs and between 59 % and 63 % for the remaining 3 MVs. This sample category represents a suite of sediments successively buried with depth by the mud emanating from bubbling pools or cones. With the counteraction of atmospheric oxidation and reducing power derived from methane, sulfur, and organic matter, a strong redox and geochemical gradient develops as a result of the transient interaction between biogeochemical cycling and abiotic processes (Chang et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014; Tu et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2018). Therefore, the relatively low NST values suggest that the deterministic control on within-MV-community variance is predominantly impacted by the localized redox and geochemical context that is tightly linked to the channeling of mud and fluid sourced to the deep reservoirs.

Of diverse community members possessing key methane and sulfur metabolisms, ANME, Desulfobacterales, Methylococcales, and Thiobacillus were identified as the cosmopolitans, being present in 9–13 of the investigated MVs. The most abundant ANME ASV (accounting for 7.9 % of all ANME sequences) appeared to be the most dominant one at LGH03 (2.2 % of the total reads) but was present only as a few sequences at TA and PA01 (less than 0.1 ‰ at each MV). The most widespread ANME ASV was observed at five MVs in Italy and Georgia (Fig. S11), although it only represented 0.8 % of all ANME sequences. A similar pattern was observed for the most abundant ASVs of the Desulfobacterales and Thiobacillus that represented 2 % and 11 % of individual lineages but were only present at two and four MVs, respectively. The most widespread ASVs of these lineages (Fig. S11) were observed at nine MVs and only accounted for 0.3 % of individual lineages. Comparisons with marine counterparts further revealed a higher degree of endemism for terrestrial MVs (Fig. 3; 88 % and 70 % of ASVs unique to one terrestrial and marine MV, respectively) (Kahle and Wickham, 2013) and drastically different community compositions mediating some of these key metabolisms. For example, sulfide-oxidizing Thiotrichales and methanotrophic ANME-1 and ANME-3 are prevalent in marine settings (Ruff et al., 2015). This finding is in contrast with the terrestrial cosmopolitan sulfur-oxidizing Thiobacillus and methanotrophic ANME-2a reported in this study.

Overall, the high and NST values (Fig. 5), together with the high level of endemism in terrestrial MVs, reflect a strong pressure for local diversification. In terrestrial MVs, reduced materials are expelled to and distributed in a limited extent of the surface environment. A strong redox gradient is generated across a transect from the center of MVs to the surrounding region (Chang et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014; Tu et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2018). This phenomenon, combined with the lack of subsurface fluid exchange between terrestrial MVs, suggests that microbial dispersal is only facilitated through air circulation. Such a route imposed by strong oxidative power would be, however, particularly detrimental to further colonization of anaerobes in destination MVs. Exceptions analogous to the dispersal of thermophilic anaerobes from marine hydrothermal vents might occur if a protective agent, such as germination or sporulation, could be developed to cope with the stress associated with the exposure to the air (Bray and Curtis, 1957; Müller et al., 2014). The limitation on dispersal also renders terrestrial MVs a patchily distributed habitat and bears limited genetic exchange with the surrounding habitats.

We reported microbial community diversities and compositions associated with terrestrial MVs across the Eurasian continent. At a higher taxonomic level (phylum to order), a rather uniform composition of microbiomes was recovered from most MVs. The major phyla recovered included Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Euryarchaeota, Cyanobacteria, Firmicutes, Atribacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria. In contrast, abundant ASVs (a total of 28 928) were unevenly detected in various MVs, among which no true cosmopolitan ASV was found. Community similarities decreased and increased with geographic distances and habitat similarities, respectively. Although high NST values (100 %) were observed for bubbling fluid and surface sediment communities, low NST values (<50 %) were derived for the within-MV sediment category in 12 out of 15 MVs. The slope of the DDR was steeper than those for marine MVs, seeps, and water columns. Such community relatedness was significantly correlated with various physiochemical parameters, such as chloride, TIC, methane, and sulfate. Within individual cores, the significant correlation between community and habitat similarities highlights the importance of environmental filtering at a localized, vertical scale. In summary, the high and NST values combined with 85 % of ASVs confined to individual MVs suggest a limit on the microbial dispersal capability and a high degree of endemism. Such stochastic processes operating at continental scales in addition to deterministic filtering at local scales drive the formation of patchy habitats and the pattern of diversification in terrestrial MVs.

All data processing and plotting scripts are available from Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5973870 (Tu et al., 2022a).

The 16S rRNA gene sequence data have been deposited at NCBI under the BioProject PRJNA560274 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA560274, Tu et al., 2022b). The biogeochemical data are available from https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5973870 (Tu et al., 2022a).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-19-831-2022-supplement.

LHL and PLW initiated and designed the study. YPC, LHL, LWW, FI, JBHS, and SNR performed field work. THT, LLC, YPC, LHL, LWW, and PLW performed laboratory and statistical analyses. All co-authors participated in the discussion and paper writing process.

The contact author has declared that neither they nor their co-authors have any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive and critical comments. We would also like to acknowledge a number of scientists for their assistance with the field sampling and to offer special thanks to Sun-Lin Chung at Academia Sinica, Taiwan, for his initiation and coordination of logistic arrangement for field work in Central Asia.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology (grant nos. 100-2627-M-002-003, 109-2116-M-002-015, and 109-2116-M-110-001-MY3) and the Ministry of Education, Taiwan.

This paper was edited by Jianming Xu and reviewed by Xing Huan and one anonymous referee.

Allison, P. A. and Pye, K.: Early diagenetic mineralization and fossil Preservation in modern carbonate concretions, Palaios, 9, 561–575, https://doi.org/10.2307/3515128, 1994.

Astorga, A., Oksanen, J., Luoto, M., Soininen, J., Virtanen, R., and Muotka, T.: Distance decay of similarity in freshwater communities: Do macro- and microorganisms follow the same rules?, Global Ecol. Biogeogr., 21, 365–375, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2011.00681.x, 2012.

Beal, E. J., House, C. H., and Orphan, V. J.: Manganese- and iron-dependent marine methane oxidation, Science, 325, 184–187, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1169984, 2009.

Bolyen, E., Rideout, J. R., Dillon, M. R., et al.: Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2, Nat. Biotechnol., 37, 852–857, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9, 2019.

Borrel, G., Adam, P. S., McKay, L. J., Chen, L.-X., Sierra-García, I. N., Sieber, C. M. K., Letourneur, Q., Ghozlane, A., Andersen, G. L., Li, W.-J., Hallam, S. J., Muyzer, G., Oliveira, V. M. de, Inskeep, W. P., Banfield, J. F., and Gribaldo, S.: Wide diversity of methane and short-chain alkane metabolisms in uncultured archaea, Nat. Microbiol., 4, 603–613, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-019-0363-3, 2019.

Bray, J. R. and Curtis, J. T.: An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin, Ecol. Monogr., 27, 325–349, 1957.

Canfield, D. E.: Reactive iron in marine sediments, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 53, 619–632, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(89)90005-7, 1989.

Chang, Y.-H., Cheng, T.-W., Lai, W.-J., Tsai, W.-Y., Sun, C.-H., Lin, L.-H., and Wang, P.-L.: Microbial methane cycling in a terrestrial mud volcano in eastern Taiwan, Environ. Microbiol., 14, 895–908, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02658.x, 2012.

Chen, N.-C., Yang, T. F., Hong, W.-L., Yu, T.-L., Lin, I.-T., Wang, P.-L., Lin, S., Su, C.-C., Shen, C.-C., Wang, Y., and Lin, L.-H.: Discharge of deeply rooted fluids from submarine mud volcanism in the Taiwan accretionary prism, Sci. Rep.-UK, 10, 381, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-57250-9, 2020.

Cheng, T.-W., Chang, Y.-H., Tang, S.-L., Tseng, C.-H., Chiang, P.-W., Chang, K.-T., Sun, C.-H., Chen, Y.-G., Kuo, H.-C., Wang, C.-H., Chu, P.-H., Song, S.-R., Wang, P.-L., and Lin, L.-H.: Metabolic stratification driven by surface and subsurface interactions in a terrestrial mud volcano, ISME J., 6, 2280–2290, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2012.61, 2012.

Chiu, Y.-P.: Microbial community structure and methane cycling in mud volcanoes of Sicily, Italy, MS thesis, National Taiwan University, Taiwan, 137 pp., https://hdl.handle.net/11296/9j6jqr (last access: 5 February 2022), 2015.

Claypool, G. E. and Kvenvolden, K. A.: Methane and other hydrocarbon gases in marine sediment, Annu. Rev. Earth Pl. Sc., 11, 299–327, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ea.11.050183.001503, 1983.

Comte, J., Monier, A., Crevecoeur, S., Lovejoy, C., and Vincent, W. F.: Microbial biogeography of permafrost thaw ponds across the changing northern landscape, Ecography, 39, 609–618, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.01667, 2016.

Condit, R., Pitman, N., Leigh, E. G., Chave, J., Terborgh, J., Foster, R. B., Núñez, P., Aguilar, S., Valencia, R., Villa, G., Muller-Landau, H. C., Losos, E., and Hubbell, S. P.: Beta-diversity in tropical forest trees, Science, 295, 666–669, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1066854, 2002.

DasSarma, S. and DasSarma, P.: Halophiles, in: eLS, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470015902.a0000394.pub4, 2001.

Dice, L. R.: Measures of the amount of ecologic association between species, Ecology, 26, 297–302, https://doi.org/10.2307/1932409, 1945.

Dimitrov, L. I.: Mud volcanoes – the most important pathway for degassing deeply buried sediments, Earth-Sci. Rev., 59, 49–76, 2002.

Etiope, G., Ciotoli, G., Schwietzke, S., and Schoell, M.: Gridded maps of geological methane emissions and their isotopic signature, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 11, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-11-1-2019, 2019.

Ettwig, K. F., Zhu, B., Speth, D., Keltjens, J. T., Jetten, M. S. M., and Kartal, B.: Archaea catalyze iron-dependent anaerobic oxidation of methane, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 12792–12796, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1609534113, 2016.

Grant, W. D.: Life at low water activity, Philos. T. R. Soc. Lon. B, 359, 1249–1267, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1502, 2004.

Halevy, I., Peters, S. E., and Fischer, W. W.: Sulfate Burial Constraints on the Phanerozoic Sulfur Cycle, Science, 337, 331–334, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1220224, 2012.

Hanson, C. A., Fuhrman, J. A., Horner-Devine, M. C., and Martiny, J. B. H.: Beyond biogeographic patterns: processes shaping the microbial landscape, Nat. Rev. Microbiol, 10, 497–506, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2795, 2012.

Haroon, M. F., Hu, S., Shi, Y., Imelfort, M., Keller, J., Hugenholtz, P., Yuan, Z., and Tyson, G. W.: Anaerobic oxidation of methane coupled to nitrate reduction in a novel archaeal lineage, Nature, 500, 567–570, 2013.

Hill, M. O.: Diversity and evenness: a unifying notation and its consequences, Ecology, 54, 427–432, 1973.

Hutchison, D. W. and Templeton, A. R.: Correlation of pairwise genetic and geographic distance measures: inferring the relative influences of gene flow and drift on the distribution of genetic variability, Evolution, 53, 1898–1914, 1999.

Inagaki, F., Nunoura, T., Nakagawa, S., Teske, A., Lever, M., Lauer, A., Suzuki, M., Takai, K., Delwiche, M., Colwell, F. S., Nealson, K. H., Horikoshi, K., D'Hondt, S., and Jørgensen, B. B.: Biogeographical distribution and diversity of microbes in methane hydrate-bearing deep marine sediments on the Pacific Ocean Margin, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 2815–2820, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0511033103, 2006.

Jørgensen, S. L., Hannisdal, B., Lanzen, A., Baumberger, T., Flesland, K., Fonseca, R., Ovreås, L., Steen, I. H., Thorseth, I. H., Pedersen, R. B., and Schleper, C.: Correlating microbial community profiles with geochemical data in highly stratified sediments from the Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridge, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 109, E2846–E2855, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1207574109, 2012.

Kahle, D. and Wickham, H.: ggmap: Spatial visualization with ggplot2, R J., 5, 144–161, https://doi.org/10.32614/rj-2013-014, 2013.

Knittel, K. and Boetius, A.: Anaerobic oxidation of methane: progress with an unknown process, Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 63, 311–334, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093130, 2009.

Kuever, J.: The family Desulfobulbaceae, in: The Prokaryotes, edited by: Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E., Lory, S., Stackebrandt E., and Thompson, F., Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 75–86, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39044-9_270, 2014.

Lin, Y.-T., Tu, T.-H., Wei, C.-L., Rumble, D., Lin, L.-H., and Wang, P.-L.: Steep redox gradient and biogeochemical cycling driven by deeply sourced fluids and gases in a terrestrial mud volcano, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 94, 3796, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiy171, 2018.

Liu, X., Li, M., Castelle, C. J., Probst, A. J., Zhou, Z., Pan, J., Liu, Y., Banfield, J. F., and Gu, J.-D.: Insights into the ecology, evolution, and metabolism of the widespread Woesearchaeotal lineages, Microbiome, 6, 102, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0488-2, 2018.

Lomolino, M. V., Riddle, B. R., and Brown, J. H. (Eds.): Biogeography, 3rd Edn., Sinauer Associates, Inc., ISBN 10-08-7893-486-3, 2006.

Martiny, J. B. H., Eisen, J. A., Penn, K., Allison, S. D., and Horner-Devine, M. C.: Drivers of bacterial beta-diversity depend on spatial scale, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 7850–7854, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1016308108, 2011.

Mazzini, A. and Etiope, G.: Mud volcanism: An updated review, Earth-Sci. Rev., 168, 81–112, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.03.001, 2017.

McGenity, T. J.: Halophilic hydrocarbon degraders, in: Handbook of hydrocarbon and lipid microbiology, edited by: Timmis, K. N., Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 1939–1951, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-77587-4_142, 2010.

McIlroy, S. J. and Nielsen, P. H.: The family Saprospiraceae, in: The Prokaryotes, edited by: Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E. F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E., and Thompson F., Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 863–889, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-38954-2_138, 2014.

Mori, J. F., Chen, L.-X., Jessen, G. L., Rudderham, S. B., McBeth, J. M., Lindsay, M. B. J., Slater, G. F., Banfield, J. F., and Warren, L. A.: Putative mixotrophic nitrifying-denitrifying Gammaproteobacteria implicated in nitrogen cycling within the ammonia/oxygen transition zone of an oil sands pit lake, Front. Microbiol., 10, 2435, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02435, 2019.

Müller, A. L., Rezende, J. R. de, Hubert, C. R. J., Kjeldsen, K. U., Lagkouvardos, I., Berry, D., Jørgensen, B. B., and Loy, A.: Endospores of thermophilic bacteria as tracers of microbial dispersal by ocean currents., ISME J., 8, 1153–1165, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.225, 2014.

Nekola, J. C. and White, P. S.: The distance decay of similarity in biogeography and ecology, J. Biogeogr., 26, 867–878, 1999.

Ning, D., Deng, Y., Tiedje, J. M., and Zhou, J.: A general framework for quantitatively assessing ecological stochasticity, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 16892–16898, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1904623116, 2019.

Or, D., Smets, B. F., Wraith, J. M., Dechesne, A., and Friedman, S. P.: Physical constraints affecting bacterial habitats and activity in unsaturated porous media – a review, Adv. Water Resour., 30, 1505–1527, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2006.05.025, 2007.

Orcutt, B. N., Sylvan, J. B., Knab, N. J., and Edwards, K. J.: Microbial ecology of the dark ocean above, at, and below the seafloor, Microbiol. Mol. Biol. R., 75, 361–422, https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.00039-10, 2011.

Oren, A.: The family Halobacteriaceae, in: The Prokaryotes, edited by: Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E. F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E., and Thompson, F., Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 41–121, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-38954-2_313, 2014.

Orphan, V. J., Hinrichs, K.-U., Ussler, W., Paull, C. K., Taylor, L. T., Sylva, S. P., Hayes, J. M., and DeLong, E. F.: Comparative analysis of methane-oxidizing archaea and sulfate-reducing bacteria in anoxic marine sediments, Appl. Environ. Microb., 67, 1922–1934, 2001.

Paulson, J. N., Stine, O. C., Bravo, H. C., and Pop, M.: Differential abundance analysis for microbial marker-gene surveys, Nat. Methods, 10, 1200–1222, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2658, 2013.

Petro, C., Starnawski, P., Schramm, A., and Kjeldsen, K. U.: Microbial community assembly in marine sediments, Aquat. Microb. Ecol., 79, 177–195, https://doi.org/10.3354/ame01826, 2017.

Power, J. F., Carere, C. R., Lee, C. K., Wakerley, G. L. J., Evans, D. W., Button, M., White, D., Climo, M. D., Hinze, A. M., Morgan, X. C., McDonald, I. R., Cary, S. C., and Stott, M. B.: Microbial biogeography of 925 geothermal springs in New Zealand, Nat. Commun., 9, 3152, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05020-y, 2018.

Ranjard, L., Dequiedt, S., Prévost-Bouré, N. C., Thioulouse, J., Saby, N. P. A., Lelievre, M., Maron, P. A., Morin, F. E. R., Bispo, A., Jolivet, C., Arrouays, D., and Lemanceau, P.: Turnover of soil bacterial diversity driven by wide-scale environmental heterogeneity, Nat. Commun., 4, 1434, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2431, 2013.

Ruff, S. E., Biddle, J. F., Teske, A. P., Knittel, K., Boetius, A., and Ramette, A.: Global dispersion and local diversification of the methane seep microbiome, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 112, 4015–4020, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1421865112, 2015.

Scheller, S., Yu, H., Chadwick, G. L., McGlynn, S. E., and Orphan, V. J.: Artificial electron acceptors decouple archaeal methane oxidation from sulfate reduction, Science, 351, 703–707, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad7154, 2016.

Schloss, P. D., Westcott, S. L., Ryabin, T., Hall, J. R., Hartmann, M., Hollister, E. B., Lesniewski, R. A., Oakley, B. B., Parks, D. H., and Robinson, C. J.: Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities, Appl. Environ. Microb., 75, 7537–7541, 2009.

Slatkin, M.: Isolation by distance in eqilibrium and non-equilibrium populations, Evolution, 47, 264–279, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb01215.x, 1993.

Sorokin, D. Y., Merkel, A. Y., and Muyzer, G.: Thiohalorhabdus, in Bergey's manual of systematics of archaea and bacteria (1–6), edited by: Trujillo, M. E., Dedysh, S., DeVos, P., Hedlund, B., Kämpfer, P., Rainey, F. A., and Whitman, W. B., John Wiley & Sons, New York, New Jersey, United States, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118960608.gbm01940, 2020.

Tu, T.-H., Wu, L.-W., Lin, Y.-S., Imachi, H., Lin, L.-H., and Wang, P.-L.: Microbial community composition and functional capacity in a terrestrial ferruginous, sulfate-depleted mud volcano, Front. Microbiol., 8, 2137, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02137, 2017.

Tu, T.-H., Chen, L.-L., Chiu, Y.-P., Lin, L.-H., Wu, L.-W., Italiano, F., Shyu, J. B. H., Raisossadat, S. N., and Wang, P.-L.: The biogeographic pattern of microbial communities inhabiting terrestrial mud volcanoes across the Eurasian continent, Zenodo [data set, code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5973870, 2022a.

Tu, T.-H., Chen, L.-L., Chiu, Y.-P., Lin, L.-H., Wu, L.-W., Italiano, F., Shyu, J. B. H., Raisossadat, S. N., and Wang, P.-L.: The biogeographic pattern of microbial communities inhabiting terrestrial mud volcanoes across the Eurasian continent, NCBI [data set], https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA560274, last access: 8 February 2022b.

Wang, P.-L., Chiu, Y.-P., Cheng, T.-W., Chang, Y.-H., Tu, W.-X., and Lin, L.-H.: Spatial variations of community structures and methane cycling across a transect of Lei-Gong-Hou mud volcanoes in eastern Taiwan, Front. Microbiol., 5, 2946, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00121, 2014.

Weber, L., DeForce, E., and Apprill, A.: Optimization of DNA extraction for advancing coral microbiota investigations, Microbiome, 5, 18, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-017-0229-y, 2017.

Whiticar, M. J.: Carbon and hydrogen isotope systematics of bacterial formation and oxidation of methane, Chem. Geol., 161, 291–314, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-2541(99)00092-3, 1999.

Yamada, T. and Sekiguchi, Y.: Cultivation of Uncultured Chloroflexi Subphyla: Significance and Ecophysiology of Formerly Uncultured Chloroflexi “Subphylum I” with Natural and Biotechnological Relevance, Microbes Environment, 24, 205–216, https://doi.org/10.1264/jsme2.me09151s, 2009.

Yao, W. and Millero, F. J.: Oxidation of hydrogen sulfide by hydrous Fe(III) oxides in seawater, Mar. Chem., 52, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4203(95)00072-0, 1996.

Zheng, G., Xu, S., Liang, M., Dermatas, D., and Xu, X.: Transformations of organic carbon and its impact on lead weathering in shooting range soils, Environ. Earth Sci., 64, 2241–2246, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-011-1052-6, 2011.

Zinger, L., Boetius, A., and Ramette, A.: Bacterial taxa-area and distance-decay relationships in marine environments, Mol. Ecol., 23, 954–964, https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12640, 2014.