the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Estimating oil-palm Si storage, Si return to soils, and Si losses through harvest in smallholder oil-palm plantations of Sumatra, Indonesia

Britta Greenshields

Barbara von der Lühe

Felix Schwarz

Harold J. Hughes

Aiyen Tjoa

Martyna Kotowska

Fabian Brambach

Daniela Sauer

Most plant-available Si in strongly desilicated soils is provided through litter decomposition and subsequent phytolith dissolution. The importance of silicon (Si) cycling in tropical soil–plant systems raised the question of whether oil-palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) cultivation alters Si cycling. As oil palms are considered Si hyper-accumulators, we hypothesized that much Si is stored in the above-ground biomass of oil palms with time. Furthermore, the system might lose considerable amounts of Si every year through fruit-bunch harvest. To test these hypotheses, we analysed Si concentrations in fruit-bunch stalks, fruit pulp and kernels, leaflets, rachises, and frond bases of mature oil palms on eight smallholder oil-palm plantations in Sumatra, Indonesia. We estimated Si storage in the total above-ground biomass of oil palms, Si return to soils through decomposing pruned palm fronds, and Si losses from the system through harvest. Leaflets of oil-palm fronds had a mean Si concentration of > 1 wt %. All other analysed plant parts had < 0.5 wt % Si. According to our estimates, a single palm tree stored about 4–5 kg Si in its total above-ground biomass. A smallholder oil-palm plantation stored at least 550 kg Si ha−1 in the palm trees' above-ground biomass. Pruned palm fronds returned 111–131 kg of Si ha−1 to topsoils each year. Fruit-bunch harvest corresponded to an annual Si export of 32–72 kg Si ha−1 in 2015 and 2018. Greater Si losses (of at least 550 kg Si ha−1) would occur from the system if oil-palm stems were removed from plantations prior to replanting. Therefore, it is advisable to leave oil-palm stems on the plantations, e.g. by distributing chipped stem parts across the plantation at the end of a plantation cycle (∼ 25 years).

- Article

(5072 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Indonesia has become one of the largest global palm-oil producers, with currently ∼ 16 million hectares under oil-palm cultivation (Gaveau et al., 2022). In the 1980s, the emerging palm-oil boom led to clearing of rainforests (Tsujino et al., 2016; Qaim et al., 2020). Since then, palm oil has remained a tropical cash crop with high demand on the global market (Qaim et al., 2020) due to its versatile use, e.g. as vegetable oil, in cosmetics, and as biofuels (FAO, 2020). In the province of Jambi, Indonesia, oil-palm cultivation has improved the livelihoods of many smallholder farmers but at the expense of the natural environment (Clough et al., 2016; Grass et al., 2020; Qaim et al., 2020). This has resulted in a decrease in biodiversity (Drescher et al., 2016; Meijaard et al., 2020) and ecosystem services (Dislich et al., 2017). To balance ecosystem preservation (Tsujino et al., 2016) and economic prosperity (Grass et al., 2020), current research aims to identify ways to increase land use sustainability while keeping current oil-palm plantations profitable (Darras et al., 2019; Luke et al., 2019).

Oil palms (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.), like many other crops, are commonly grown on highly weathered soils that have been exposed to intense element leaching, including phosphorous (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), and silicon (Si) (Haynes, 2014). However, well-balanced Si levels in soils are essential for many crops because Si can promote the release of adsorbed macro-nutrients and prevent plant toxicity at low soil pH (Epstein, 2009). Plants store Si in their leaf tissue to mitigate biotic and abiotic stresses and to reduce transpiration. Si is taken up from the soil solution as monomeric silicic acid (H4SiO4) (Haynes, 2017) and is then transported from the roots to the shoot with the xylem flow (Liang et al., 2015). Transpiration increases the Si concentration in the leaf tissue, where Si finally precipitates as amorphous silica bodies called phytoliths (SiO2 ⋅ nH2O) (Liang et al., 2015; Haynes, 2017). It preferentially precipitates in epidermal cell walls, the cell lumen, and intercellular spaces of any plant part, such as the shoot, leaflets, leaf stalk, and fruit (Liang et al., 2015). Si can also precipitate in certain Si cells associated with the vascular system in the stem or endodermis of roots (Epstein, 1994; Haynes, 2017).

Plants can be grouped into three categories based on the Si concentration and Si / Ca ratio in their dry leaf tissue (Ma and Takahashi, 2002): (i) non-accumulators or excluders (Si concentration < 0.5 wt %; Si / Ca < 0.5); (ii) intermediate accumulators (Si concentration 0.5 wt %–1 wt %; Si / Ca 0.5–1); (iii) accumulators (Si concentration > 1 wt %; Si / Ca > 1). To better distinguish between plants of groups II and III, we will use the term “hyper-accumulator” for plants of group III throughout this paper. Following this terminology, Si hyper-accumulators include e.g. rice (Oryza sativa L.), barley (Hordeum vulgare L.), maize (Zea mays L.), wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), and sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) (Haynes, 2017). According to Munevar and Romero (2015), oil palms are Si hyper-accumulators too. They reported high Si concentrations in oil-palm fronds in Colombia and found that the Si concentration increased with leaf age. However, these observations have not yet been confirmed in any other oil-palm growing region. In addition, Si concentrations of oil-palm parts other than leaves need to be quantified to reliably estimate Si storage in oil palms.

Several studies have shown that land conversion from forests to arable land has caused soil Si depletion in the long term (Struyf et al., 2010; Clymans et al., 2015; Carey and Fulweiler, 2016). Thereby, reduced Si return to soils through litter input and Si export through crop harvest were identified as the main drivers (Puppe et al., 2021; Vandevenne et al., 2012; Guntzer et al., 2012). The weathering stages of soils can also affect biological Si cycling (Vander Linden and Delvaux, 2019; Carey, 2020; de Tombeur et al., 2020). In strongly weathered soils, Si cycling is predominantly maintained by the recycling of phytoliths (de Tombeur et al., 2020). For these reasons, some crops already receive Si fertilizers, especially when cultivated on strongly weathered, naturally desilicated soils (Datnoff et al., 1997; Li and Delvaux, 2019; Zellner et al., 2021). Under oil-palm plantations, amorphous Si concentrations in topsoil were decreased (by a factor of 1.25) compared to rainforest topsoil (von der Lühe et al., 2020). Furthermore, the dissolution rate of phytoliths isolated from oil-palm litter was significantly lower compared to rainforest litter (von der Lühe et al., 2022). These previous observations suggest that rainforest conversion to oil-palm plantations can considerably alter Si cycling. This raised our concern that oil-palm cultivation may lead to soil Si depletion with time to a degree that could negatively affect future crop yields.

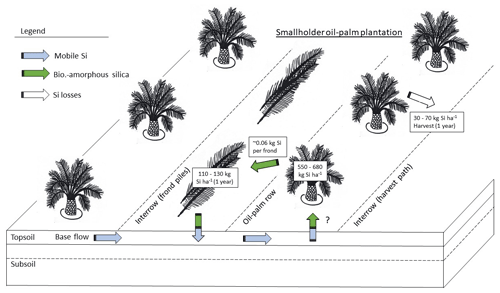

Si cycling differs between oil-palm plantations and undisturbed terrestrial ecosystems: in undisturbed terrestrial ecosystems, Si returns to soil through litterfall. Subsequent litter decomposition leads to an accumulation of phytoliths in the topsoil (Conley et al., 2008; Li et al., 2020), which is a key source of Si that can easily become plant-available (Lucas et al., 1993; Alexandre et al., 1997; Schaller et al., 2018). In oil-palm plantations, Si which has been taken up by oil palms mainly returns to soils through decomposing palm fronds (von der Lühe et al., 2022) which are pruned and then commonly stacked in piles in every second row of a plantation (Dislich et al., 2017). Phytolith accumulation in topsoils is therefore largely restricted to frond-pile areas (Greenshields et al., 2023; von der Lühe et al., 2022), which may comprise as little as ∼ 12 % of the plantation (Tarigan et al., 2020). In oil-palm plantations, Si cycling is expected to be further disrupted by fruit-bunch harvest. Si losses from the system can be considerable as not only fruit, but also entire fruit bunches are removed from the system (Kotowska et al., 2015; Euler et al., 2016a). Lastly, oil palms have a ∼ 25-year cultivation cycle (Corley and Tinker, 2016). Many oil-palm plantations in Indonesia are currently approaching the end of their first cultivation cycle in Sumatra. However, there is no clear strategy on how to use the biomass of the first-generation oil palms (Awalludin et al., 2015).

To our knowledge, only Munevar and Romero (2015) have quantified Si concentrations in oil-palm leaves so far. Furthermore, no Si concentrations from oil-palm parts other than leaflets have been reported yet. Therefore, our study in a region dominated by smallholder oil-palm plantations in lowland Sumatra, Indonesia, had two aims, first to test whether oil palms in Indonesia can be considered Si hyper-accumulators and second to estimate Si storage in oil palms, Si losses from the system through harvest, and Si return from plants to soils on oil-palm plantations in two different landscape positions (well-drained areas – slopes; riparian areas – floodplains) and WRB reference soil groups (Acrisols and Stagnosols). We hypothesized that much Si is stored in the above-ground biomass of oil palms with time. Furthermore, the system might lose considerable amounts of Si every year through fruit-bunch harvest. To account for the landscape position, we further hypothesized that soils in riparian areas might be less affected by Si depletion because they additionally receive dissolved silicic acid through flooding and capillary rise of groundwater as well as through lateral water fluxes (inflow) from higher landscape areas. We expected that greater Si availability in riparian areas would result in greater Si uptake and consequently in greater Si storage in the above-ground biomass of riparian oil-palm plantations.

2.1 Study area and selected oil-palm plantations

The study was conducted in the lowlands of the province of Jambi, Sumatra, Indonesia (1∘55′0′′ S, 103∘15′0′′ E; 50 m ± 5 m above sea level). The region has a humid tropical climate with a mean annual temperature of 26.7 ∘C and mean annual precipitation of 2230 mm yr−1 (Drescher et al., 2016). The climate is characterized by two rainy seasons in December and March and a dry season lasting from July to August (Drescher et al., 2016). The geological basement of the study area consists of pre-Paleogene metamorphic and igneous bedrock alongside lacustrine and fluvial sediments (De Coster, 2006). The soils in well-drained areas at higher landscape positions are predominantly Acrisols, whereas the temporarily flooded riparian areas are dominated by Stagnosols (IUSS Working Group WRB, 2022; Hennings et al., 2021). The natural vegetation is a mixed dipterocarp lowland rainforest (Laumonier, 1997). Alongside oil-palm plantations, large areas in the lowlands of the province of Jambi are also covered by rubber, jungle rubber, and commercial timber (Dislich et al., 2017). We conducted sampling on smallholder oil-palm plantations (≤ 2 ha) at four well-drained (Acrisol) and four riparian (Stagnosol) sites (Dislich et al., 2017). On each plantation, study plots (50×50 m) were established by the Collaborative Research Centre (CRC) 990 – Ecological and Socioeconomic Functions of Tropical Lowland Rainforest Transformation Systems (funded by the German Research Foundation). At the time of sampling, oil palms were 18–22 years old at the well-drained sites (HO1–4) and 11–21 years old at riparian sites (HOr1–4) (Hennings et al., 2021). The average planting density was 142 ± 17 oil palms per hectare. Oil palms were planted in a triangular planting array with ∼ 9 m distance between individual palm trees. Smallholder farmers followed common management practices. Thereby, interrows (i.e. empty spaces on either side of an oil-palm row) served either as harvesting paths or were used to stack pruned palm fronds (Darras et al., 2019). Herbicides (e.g. glyphosate) were sprayed twice per year to clear understorey vegetation in the interrows. The palm circle, a circular area with a radius of ca. 2 m around an oil-palm stem (Munevar and Romero, 2015), was weeded regularly. Inorganic fertilizers (NPK, KCl, and urea) were applied twice per year within the palm circle (Allen et al., 2016; Euler et al., 2016b).

2.2 Study design and plant sampling

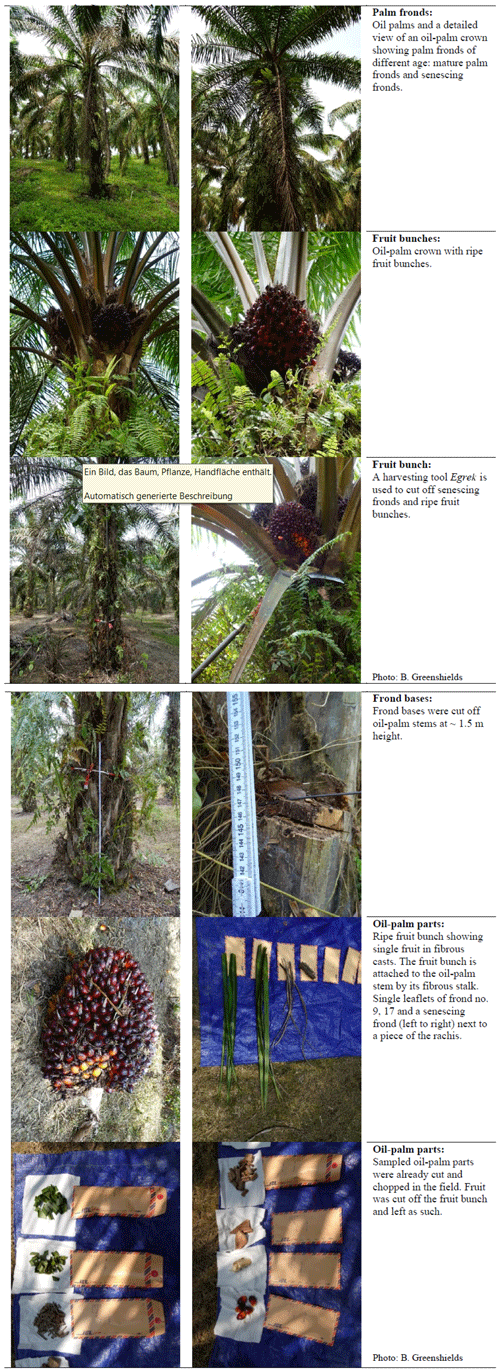

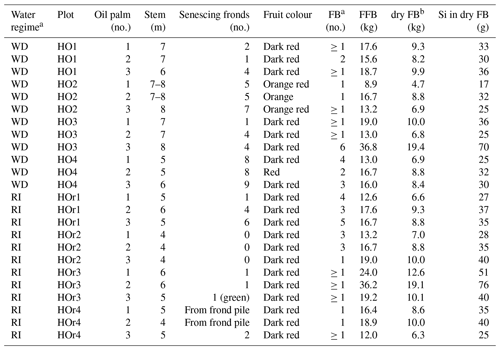

We aimed to quantify Si concentrations in the different plant parts of an oil palm and to subsequently derive Si storage estimates for the average total above-ground biomass of 1 ha of an oil-palm plantation. For this purpose, we sampled leaflets, rachises, fruit-bunch stalks, fruit pulp, kernels, and frond bases of oil palms (Appendix Table A1). Oil-palm sampling was coordinated with the regional harvesting schedule to ensure that all sampled oil-palm parts (n = 3 for each part) originated from the same palm tree. At each well-drained (HO1–4) and riparian (HOr1–4) site, three morphologically similar oil palms with at least one ripe fruit bunch were selected for sampling (Appendix Table B2).

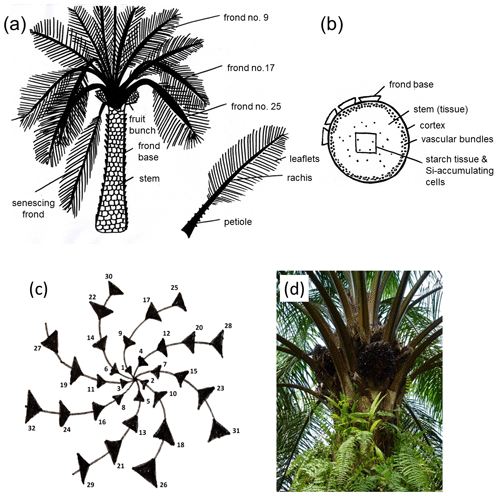

The regular phyllotaxis of the oil palm allows us to group palm fronds into (i) young fronds, (ii) mature fronds, and (iii) senescing fronds (Rees, 1964; Albakri et al., 2019) (Fig. 1a, c, d). Frond no. 1 is the youngest frond, frond no. 9 is the first mature frond, and the senescing frond (∼ leaf no. 40) is the oldest frond still attached to the oil-palm stem (Corley and Tinker, 2016). Grouping fronds according to age is important because we assume that they have different Si concentrations (Munevar and Romero, 2015). Frond no. 17 is commonly used as a reference frond to determine the nutrient status of a palm tree (Ollivier et al., 2017; Amirruddin et al., 2017). We collected leaflets from frond no. 9, frond no. 17, and a senescing frond. We also sampled rachises and frond bases (attachment of petioles to the stem). In addition, we sampled a ripe fruit bunch of each selected palm tree. The latter was sub-divided into fruit-bunch stalk, fruit pulp, and kernel (Fig. 1a). We did not have the opportunity to sample oil-palm stems (Fig. 1b) and therefore used data of Pratiwi et al. (2018) in our Si storage calculations. They quantified SiO2 concentrations of oil-palm stems in Malaysia, which we converted into Si concentrations. All Si concentrations are presented as the percentage of weight of the dry biomass of each part. The grand means refer to three oil palms per plot which provided the basis for subsequent Si storage calculations.

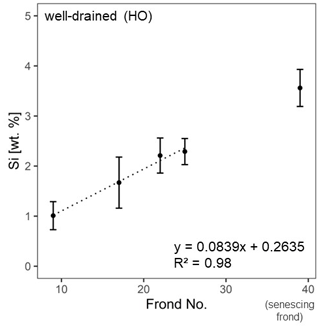

In well-drained areas, we additionally assessed how Si accumulated with leaf age. For this purpose, we sampled leaflets from two additional mature palm fronds, i.e. frond no. 22 and frond no. 25 from two oil palms per plot. To exclude any bias in the calculations of Si accumulation in leaf tissue, the grand means of frond no. 9, 17, 22, and 25 and the senescing frond were all calculated based on two oil palms per plot (Table 1). In contrast to Munevar and Romero (2015), we only included mature fronds (≥ leaf no. 9). In the field, oil-palm leaflets were wiped clean of dust and then cut into smaller pieces. Fruit were cut off from the lower part of the fruit bunch. The oil-palm parts were then dried at 60 ∘C for 48 h. Prior to analysis, leaflets were finely ground (5 min). The rachises, frond bases, and fruit-bunch stalks were first cut into chunks and then chopped finely. Fruit pulp was separated from the kernel. The kernels were cooled with liquid nitrogen so that they could be crushed and ground despite their high oil content. They were then ground into a fine powder in a stainless-steel mortar.

Figure 1(a) Morphology of the oil-palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) and plant parts sampled for this study after Lewis et al. (2020). (b) Cross section through an oil-palm stem, including Si-accumulating cells after Dungani et al. (2013). (c) Phyllotaxis of the oil palm after Albakri et al. (2019). Black triangles represent palm fronds. (d) Oil-palm crown with regular phyllotaxis (photo Britta Greenshields).

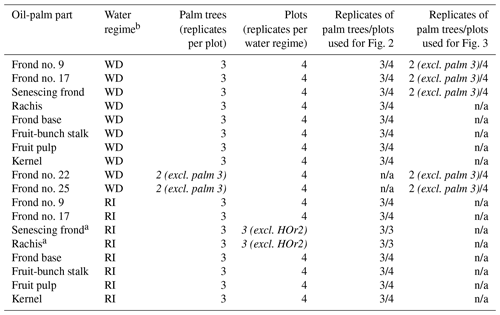

Table 1Sampling scheme and number of replicates, providing the statistical basis of Figs. 2 and 3.

a Only three replicate plots as no senescing fronds were left hanging on palm trees at site HOr2 (differing management practice). b WD: well-drained, RI: riparian. c Italics: differing from the general sampling scheme. n/a: not applicable.

2.3 Extraction methods

2.3.1 Alkaline extraction for determining Si concentrations of oil-palm parts

Si was extracted from all sampled oil-palm parts by leaching with 1 % Na2CO3 after Meunier et al. (2014) and Saccone et al. (2007). As 1 % Na2CO3 may not completely dissolve amorphous silica (Saccone et al., 2007; Li and Delvaux, 2019), we conducted a pre-test to compare the efficiency of 1 M NaOH and 1 % Na2CO3 to extract Si from various types of plant parts included in this study. NaOH could generally extract Si more efficiently from those plant parts remaining in the system, whereas Na2CO3 could extract Si more efficiently from those parts leaving the system through harvest (except for the fruit-bunch stalk, which underestimated Si by 8 %). As the latter are more important for calculating the final Si budget of the system, we decided to use Na2CO3. Each plant sample was extracted and analysed in two laboratory replicates. We accepted ≤ 10 % relative error between the two laboratory replicates. In case this threshold was exceeded, a third replicate was done.

Forty millilitres of 1 % Na2CO3 solution was added to approximately 50 mg of finely ground plant material in 50 mL centrifugation tubes. The tubes were placed in a shaking hot-water bath at 85 ∘C (continuous shaking, 85 rpm) and were additionally shaken manually after 1 h. The tubes were left to react overnight for 16 h. On the next day, the samples were cooled off in a cold-water basin for 10 min and were then centrifuged for 5 min at 3000 rpm. An aliquot of 125 µL was transferred to a plastic tube, neutralized with 1125 µL 0.021 M HCl, and diluted to 2.5 mL with de-ionized water. Si was analysed according to the molybdenum blue method (Grasshoff et al., 2009) with a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Lambda 40, Perkin Elmer, Germany) at 810 nm.

2.3.2 HNO3 digestion for determining Ca concentrations of oil-palm parts

Ca concentrations of all sampled oil-palm parts were determined by HNO3 digestion (Heinrichs and Hermann, 1990; Heinrichs et al., 1986). Prior to analysis, 50 mL Teflon beakers were rinsed with de-ionized water (18.3Ω) and dried (60 ∘C, 24 h). Approximately 50–150 mg of sample was weighed into each Teflon beaker, and then 2 mL of concentrated HNO3 solution was added to each sample. The Teflon beakers were closed with a Teflon lid and inserted into digestion blocks. These digestion blocks were placed into a drying oven and left to react at 170 ∘C for 10 h. Afterwards, the digestion solution was transferred into 50 mL volumetric flasks through ash-free filters and filled up with de-ionized water to 50 mL. Ca concentrations were measured with an inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer (ICP-AES, iCap 7000, Thermo Fisher Scientific GmbH, Germany) at 317.887 nm.

2.4 Estimating Si storage in the above-ground biomass of oil palms and 1 ha of plantation

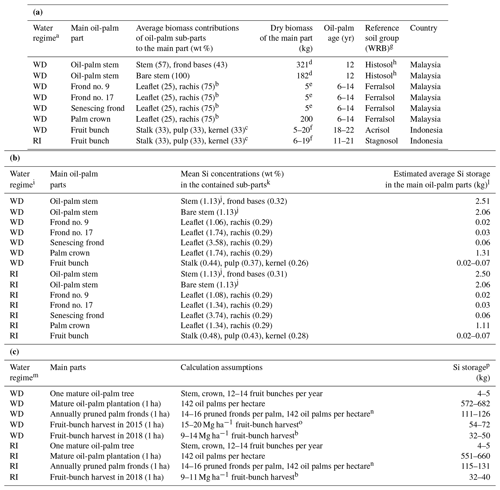

For any given oil-palm part, Si storage can be calculated by multiplying the Si concentration by its dry-weight biomass. As we quantified Si concentrations of oil-palm sub-parts, i.e. leaflets, rachises, frond bases, fruit-bunch stalks, fruit pulp, and kernels (Sect. 2.2, Table 2a), but the literature mostly provided dry weights of the oil-palm main parts, i.e. the stem with palm-frond bases, palm fronds, palm crowns, and fruit bunches (Corley et al., 1971; Lewis et al., 2020), estimating Si storage in the above-ground biomass of oil palms and 1 ha oil-palm plantation required some additional calculations as follows: we first estimated the dry biomass of each oil-palm sub-part by multiplying the dry biomass of each main part by its percentage contribution of the respective sub-part (Table 2a). We then multiplied the dry biomass of each sub-part by its mean Si concentration (Table 2b) to calculate the Si storage of the main oil-palm parts. Si storage in the total above-ground biomass of an oil palm was calculated by adding up the amounts of Si stored in an oil-palm stem, in a palm crown composed of 40 mature palm fronds, and in 12–14 fruit bunches, which is considered an average annual production of a mature oil palm (Corley and Tinker, 2016) (Table 2c). Si storage in the above-ground oil-palm biomass of a 1 ha oil-palm plantation was calculated by multiplying the amount of Si stored in one mature oil palm by the average oil-palm-planting density. All calculations were done for well-drained and riparian sites individually. The dry weights of the oil-palm main parts obtained from the literature only included data from mature oil palms (≥ 6 years) and were further distinguished according to the WRB reference soil group. Fruit-bunch biomass varied noticeably among oil palms, whereas the other main parts showed less variability in their dry biomass. Therefore, dry biomass ranges are presented only for fruit bunches.

Table 2(a) Dry biomass estimates of the main parts of mature oil palms in South-East Asia and relative contributions of oil-palm sub-parts to the biomass of the main parts. (b) Calculation of average Si storage in the main oil-palm parts of mature oil palms in South-East Asia. (c) Si storage calculation in the above-ground oil-palm biomass in 1 ha of oil-palm plantation.

a WD: well-drained, RI: riparian. b This study, Martyna Kotowska, personal communication, 2021. c Average share estimated. d Lewis et al. (2020). e Corley et al. (1971). f Data from this study. g WRB: IUSS Working Group WRB (2022): World Reference Base for Soil Resources, fourth edition. h Stem biomass data of mature oil palms in South-East Asia were only found for drained Histosols. i WD: well-drained, RI: riparian. j Pratiwi et al. (2018) determined the SiO2 concentration in the oil-palm stem, which we converted to Si concentration (2.41 wt % SiO2 equaling 1.13 wt % Si). k Total Si concentrations including error terms and the number of replicates are shown in Table B1 in the Appendix. l Calculated by multiplying the mean Si concentration of each oil-palm sub-part by the biomass that the sub-part contributes to the main oil-palm part; data for fruit bunches mark the range that results from the highly variable fruit-bunch biomass. m WD: well-drained, RI: riparian. n Aiyen Tjoa, personal communication, 2021. o Kotowska et al. (2015). p Data in the fourth column of the table mark the range of Si storage in the oil-palm parts listed in the second column, calculated based on the assumptions shown in the third column.

In addition to the amount of Si stored in oil palms, we also calculated Si return to soils through pruned palm fronds and Si losses through fruit-bunch harvest (Table 2c). Our estimates of Si return to soils were based on 14–16 pruned palm fronds per palm each year, considering the average age of the investigated oil palms (Woittiez et al., 2017; Aiyen Tjoa, personal communication, 2021). Our Si-loss estimates through fruit-bunch harvest were based on the harvests of 2 years in the province of Jambi, i.e. the harvests of the years 2015 (well-drained) and 2018 (well-drained and riparian) (Kotowska et al., 2015; this study). We multiplied the average annual fruit-bunch harvest of these 2 years by the mean Si concentration of a fruit bunch to estimate annual Si losses through fruit-bunch harvest. Again, these calculations were done individually for well-drained and riparian sites.

2.5 Statistics

Statistical analyses were conducted on the grand means of three palm trees (n = 3) in four replicate plots at well-drained and riparian sites (n = 4 each). No senescing frond could be sampled at the riparian site HOr2, as ageing fronds were pruned early to maintain a high crop yield (smallholder farmers, personal communication, 2021). Statistical analyses were done on log-transformed data. Normal distribution (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homogeneity of variances (Levene test) were tested for all groups. We conducted a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test whether the Si concentration of each oil-palm part differed significantly between the two water regimes. We conducted a Tukey–Kramer post hoc test to examine which oil-palm parts differed significantly in their Si concentrations. Statistical significance was assigned at p≤0.05 in all analyses. We used the open-source software R version 3.6.2 and the R CRAN packages ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016), car (Fox and Weisberg, 2019), and psych (Revelle, 2022) to perform statistical analyses.

For well-drained sites, we fitted a trend line to test whether Si accumulated with frond age. The trend line was fitted to the grand means (n = 4 plantations, n = 2 oil palms per plantation) of four mature frond leaflets (no. 9, no. 17, no. 22, and no. 25). The senescing frond was plotted as frond no. 39, although the exact frond number was not determined in the field.

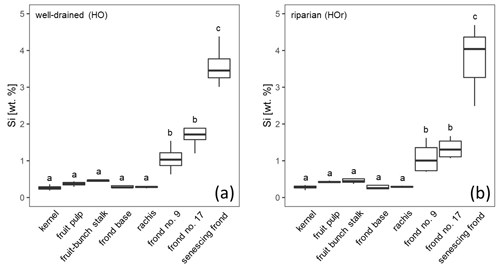

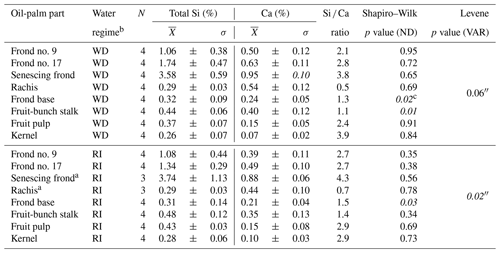

3.1 Si and Ca concentrations in oil-palm parts

At well-drained sites, leaflets of all analysed palm fronds had a mean Si concentration of at least 1 wt % Si, whereas rachises, frond bases, fruit-bunch stalks, fruit pulp, and kernels had mean Si concentrations below 0.5 wt % Si (Fig. 2a). Mean Si concentrations in leaflets of frond no. 9 (1.06 ± 0.38 wt % Si), leaflets of frond no. 17 (1.74 ± 0.47 wt % Si), and leaflets of the senescing frond (3.58 ± 0.59 wt % Si) were also significantly higher (p≤0.05) compared to those of the fruit-bunch stalk (0.44 ± 0.06 wt % Si), frond base (0.32 ± 0.09 wt % Si), rachis (0.29 ± 0.03 wt % Si), fruit pulp (0.37 ± 0.07 wt % Si), and kernel (0.26 ± 0.07 wt % Si) (Fig. 2a, Appendix Table B1). Mean Si concentrations in leaflets of the senescing palm frond were significantly higher (p≤0.05) than Si concentrations in leaflets of frond no. 17 and leaflets of frond no. 9, while mean Si concentrations did not differ significantly between the latter two. All the oil-palm parts showed a Si / Ca weight ratio of > 1, except for the rachises, which had a Si / Ca weight ratio of 0.5 (Appendix Table B1).

At riparian sites, mean Si concentrations followed a similar trend to the well-drained sites (Fig. 2a and b). Again, leaflets of palm fronds had significantly higher Si concentrations (p≤0.05) in their tissue than other oil-palm parts (Fig. 2b). Mean Si concentrations increased with age from 1.08 ± 0.44 wt % Si in leaflets of palm frond no. 9 to 3.74 ± 1.13 wt % Si in leaflets of the senescing palm frond (Fig. 2, Appendix Table B1). Si concentrations in leaflets of the senescing palm fronds were significantly higher (p≤0.05) than those in leaflets of palm frond no. 9 and palm frond no. 17 (Fig. 2b). In contrast, mean Si concentrations in the rachises, frond bases, fruit-bunch stalks, fruit pulp, and kernels were in a similar range of around 0.3 wt % to 0.5 wt % Si (Fig. 2b). Rachises had the smallest Si / Ca ratio of 0.7, whereas leaflets of the senescing palm frond had the largest Si / Ca ratio of 4.3 (Appendix Table B1). When comparing Si concentrations of the same oil-palm part (e.g. rachis) between well-drained and riparian sites (HO and HOr), Si concentrations were similar. No significant differences were detected (Appendix Table B1).

At the well-drained sites, we additionally assessed in more detail how Si accumulated with leaf age. Mean Si concentrations in leaflets of four mature palm fronds increased linearly (R2 = 0.98) with palm-frond age (Fig. 3).

Figure 2Si concentrations in oil-palm sub-parts at (a) well-drained and (b) riparian sites. Lower-cased letters indicate significant differences (p≤0.05) between oil-palm sub-parts within the same water regime. n = 4 for each plant part, except for the senescing frond and rachis, which is n = 3 at riparian sites.

3.2 Si storage in the above-ground biomass of oil palms, Si return to soils through decomposing pruned palm fronds, and Si losses through harvest on smallholder oil-palm plantations

Calculating Si storage in the above-ground biomass of oil palms required biomass data for all plant parts. As it was not permitted to cut down oil palms to determine the stem and frond-base biomass per palm tree, we used mean biomass estimates of mature oil palms in South-East Asia from the literature (Table 2a). Lewis et al. (2020) calculated the average biomass of a bare oil-palm stem (∼ 182 kg) and a stem including palm-frond bases (∼ 321 kg). These data suggest that palm-frond bases add another ∼ 40 wt % of biomass to an oil-palm stem. Corley et al. (1971) estimated a mature oil-palm frond to weigh ∼ 5 kg. Based on these literature data and our own observations, we estimated a palm crown composed of 40 fronds to weigh roughly ∼ 200 kg, which is in the same range as a bare oil-palm stem. In comparison, a single fruit bunch weighed between 5 and 20 kg (Appendix Table B2).

Si storage in the analysed oil-palm parts was similar at well-drained and riparian sites (Table 2b). Among all the analysed parts, the oil-palm stem contributed the most to the estimated Si storage of one palm tree, amounting to 2.0–2.5 kg Si. Thereby, palm-frond bases that are attached to the palm stem up to an age of at least 12 years contributed about 20 wt % Si (Corley and Tinker, 2016). Compared to the stem, an oil-palm crown composed of 40 palm fronds stored roughly half the amount of Si, about ∼ 1.2 kg. The 12–14 fruit bunches produced by a palm tree each year stored 0.24–0.98 kg Si (0.02–0.07 kg Si per fruit bunch). In oil-palm fronds, Si storage increased with palm-frond age from 0.02 kg Si in frond no. 9 to 0.06 kg Si in a senescing frond.

According to our calculations, smallholder plantations at well-drained and riparian sites showed similar Si storage in the total above-ground biomass of oil palms, Si return through decomposing palm fronds, and Si losses through fruit-bunch harvest (Table 2c). The above-ground biomass of a mature oil palm was estimated to store about 4–5 kg Si. Consequently, oil palms in a 1 ha smallholder oil-palm plantation stored at least 550 kg Si in their above-ground biomass. Annual Si return to the topsoil via pruned palm fronds comprised at least 110 kg Si ha−1. About 50–70 kg Si ha−1 was lost by annual fruit-bunch harvest in 2015 and about 30–50 kg Si ha−1 in 2018.

4.1 Si distribution and accumulation in various oil-palm parts

Leaflets of all investigated palm fronds had mean Si concentrations of > 1 wt % and a Si / Ca mass ratio of > 1. Furthermore, the Si concentration increased with leaf age. Thus, our results reconfirmed the classification of oil palms being Si hyper-accumulators (Ma and Takahashi, 2002). At both well-drained and riparian sites, mean Si concentrations in leaflets of oil-palm fronds (> 1 %) were significantly higher compared to all other above-ground oil-palm parts (≤ 0.8 %) (Fig. 2). These observations correspond well to the findings of Munevar and Romero (2015) and Carey and Fulweiler (2016), who reported higher Si concentrations in leaf tissue compared to other plant parts in Si hyper-accumulators as well.

In plants, Si remains dissolved in the transpiration stream (Carey and Fulweiler, 2012; Epstein, 1994) until it reaches epidermal cell walls, the cell lumen, and intercellular spaces in the leaves (Epstein, 1994). High Si concentrations in leaflets are the results of Si preferentially precipitating at final transpiration sites (Carey and Fulweiler, 2012). In contrast, significantly lower mean Si concentrations in palm-frond bases and rachises could imply that these plant parts are related to the transpiration stream rather than to transpiration and the associated Si precipitation. Instead, transpiration and the associated Si precipitation in leaflets seem to increase the mean Si concentration in the leaflets with palm-frond age and can be described well by a linear equation (Fig. 3). It is assumed that Si first accumulates in lower (abaxial) epidermal cells and with time in upper (adaxial) epidermal cells (Epstein, 1994).

Low mean Si concentrations in the various fruit-bunch parts (stalk, fruit pulp, and kernel) suggest that Si is present in fibres but barely in the hard shell and oily endosperm of the kernel (Omar et al., 2014). In the fruit-bunch stalk, Si is partly embedded within the surface or precipitates directly onto the surface of fruit-bunch fibres but not in cell walls (Omar et al., 2014). Despite low mean Si concentrations in various fruit-bunch parts, a considerable amount of Si is exported through harvest each year. In 2015, the annual fruit-bunch harvest amounted to about 15–20 Mg ha−1 dry biomass on well-drained plantations within our study area (Kotowska et al., 2015). This corresponded to an export of 54–72 kg ha−1 Si from the system (56–74 kg ha−1 Si if 8 % underestimation by Na2CO3 extraction from fruit-bunch stalks is considered as reported in Sect. 2.3.1). In 2018, the yield was lower in plantations of both well-drained and riparian areas, with 9–14 Mg ha−1 dry biomass, corresponding to an Si export of 32–50 kg ha−1 (33–52 kg ha−1 if 8 % underestimation is considered). Thus, Si losses through fruit-bunch harvest were similar for both well-drained and riparian areas.

According to Corley and Tinker (2016), the central part of the oil palm includes some Si-containing tissue as well (Fig. 1b). Si precipitation in the stem may take place along the vascular system or in cell walls. Epstein (1994) assumed that stabilizing the stem through silicifying cells can be a beneficial strategy of plants as it requires less energy than stabilizing the stem by cellulose.

Overall, our results suggest that, among all the oil-palm parts, palm leaflets accumulate Si most effectively in their tissue. Thus, the management of palm fronds plays a key role in driving and maintaining Si cycling on oil-palm plantations. However, our study also shows that Si precipitates in all above-ground oil-palm sub-parts. Therefore, specific Si concentrations of all the oil-palm parts need to be analysed individually and upscaled to palm-tree and plantation level. This allows us to evaluate potential impacts of oil-palm cultivation and management practices on Si cycling.

4.2 Identified Si storage, cycling, and losses on smallholder oil-palm plantations and favourable management practices

4.2.1 Comparison of plantations in well-drained and riparian areas

At well-drained and riparian sites, smallholder oil-palm plantations showed similar Si storage in the total above-ground biomass of oil palms, Si return to soils through decomposing oil-palm fronds, and Si losses through fruit-bunch harvest (Table 2c). We assume that this was due to similar Si concentrations in the respective oil-palm parts in both water regimes and because the same biomass data were used to calculate Si storage capacities for all the sites (Table 2a). The number of studies providing oil-palm biomass data is still too low to have been able to distinguish between riparian and well-drained soils. Therefore, our hypotheses were only partially verified: oil palms store noticeable amounts of Si in their biomass. However, an additional influx of dissolved silicic acid through flooding, capillary rise of groundwater, and lateral water fluxes (interflow) from higher-lying areas did not increase Si storage in oil-palm plantations of riparian areas.

4.2.2 Favourable management practices using palm fronds and fruit-bunch parts

In our study area, 1 ha of a smallholder oil-palm plantation stored about 551–682 kg Si in the total above-ground biomass. Pruned palm fronds returned ∼ 111–131 kg Si each year to the topsoils (Fig. 4). Annual Si losses through fruit-bunch harvest amounted to 32–72 kg ha−1 yr−1 (33–74 kg ha−1 yr−1 if 8 % underestimation by Na2CO3 is considered), which corresponds to around 6 %–10 % of the amount of Si stored in the total above-ground biomass. Although much Si is recycled in the system by the practice of frond-pile stacking, it could still be optimized, e.g. by changing the positions of frond piles every 5–10 years. Such practices would lead to a more evenly distributed Si return to topsoils across plantations.

The relevance of Si losses by harvest has been previously addressed by Puppe et al. (2021), Guntzer et al. (2012), and Vandevenne et al. (2012). In our study, Si storage in fruit bunches was localized mainly in the fruit-bunch stalk and fruit pulp (Sect. 4.1). Like oil palms, many Si hyper-accumulators store less Si in their grains than in the harvest residues (Carey and Fulweiler, 2016; Hughes et al., 2020; Vandevenne et al., 2012): in wheat (Triticum aestivum), oat (Avena sativa), and barley (Hordeum vulgare) straw, the mean Si concentration was higher than in the respective cereal grain (Vandevenne et al., 2012). Hughes et al. (2020) found rice grains (Oryza sativa) under different rice-residue management practices to accumulate 59 ± 43 kg Si ha−1 yr−1 but rice straw to accumulate 82 ± 25 kg Si ha−1 yr−1. Carey and Fulweiler (2016) and Guntzer et al. (2012) made similar observations and concluded that non-edible plant parts (e.g. straw) could serve well as an organic fertilizer. These observations highlight the importance of managing harvest residues.

Indeed, fruit-bunch harvest may alter Si cycling with time, although a significant impact may only be seen in a longer term than covered by this study (Clymans et al., 2011; Guntzer et al., 2012). Therefore, we recommend reducing Si losses through harvest by returning the empty fruit bunches (the residues not used to produce palm oil) to the palm circle on smallholder plantations. In this way, empty fruit bunches may serve as organic fertilizer and may increase amounts of bioavailable Si in the rooting area of the oil palm. This is already common practice on state-owned oil-palm plantations. However, it remains a low priority for smallholder farmers because of the logistical effort and costs involved in the transport of empty fruit bunches back to oil-palm plantations (Woittiez et al., 2018; Euler et al., 2016a).

4.2.3 Favourable management practices using stem residues

Si concentrations in the stem (Table 2b) may seem low. However, multiplying the Si concentration by the large stem biomass (Aholoukpè et al., 2018) showed that the stem provides the largest Si pool of the oil palm's above-ground biomass. In contrast, palm leaflets showed the highest Si concentrations (Table 2b) but contributed only 25 wt % to the biomass of a palm frond. This led to smaller total Si storage in the crown compared to the stem of a palm tree. Both oil-palm parts are highly relevant for Si cycling in the system. We strongly recommend keeping both the stem and the palm-frond residues on the plantation, especially when an oil-palm plantation is cleared for replanting. Oil palms could benefit from Si fertilization like other Si hyper-accumulators (Klotzbücher et al., 2018; Datnoff et al., 1997; Li and Delvaux, 2019).

Oil-palm plantations are usually cultivated for about 25 years (Corley and Tinker, 2016). Thereafter, the oil-palm stem is considered a waste product (Onoja et al., 2019; Awalludin et al., 2015). It used to be common practice to burn the stem as the ash was regarded as sustaining soil fertility (Selamat et al., 2019) by releasing Si and other nutrients into the topsoil (Selamat et al., 2019; von der Lühe et al., 2020). However, these nutrients including Si are released from the ash in such high amounts and so rapidly that they are highly susceptible to leaching. Many nutrients could be lost from the system before a new generation of oil palms can take them up. Thus, despite the short-term fertilizing effect of the ash, this process may enhance nutrient and Si depletion for the long term (von der Lühe et al., 2020). Nowadays, replanting follows a zero-burning policy (Corley and Tinker, 2016) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution. Furthermore, this policy will prevent fires from getting out of control, which could impact natural vegetation. Without burning, most stem biomass remains on the plantations as it has no monetary value for industrial or agricultural applications (Awalludin et al., 2015; Onoja et al., 2019). Currently, oil-palm stems are chipped and then distributed as an organic fertilizer at the end of a 25-year plantation cycle (Corley and Tinker, 2016). It has been suggested to provide governmental support to implement this practice on smallholder plantations as well (Woittiez et al., 2018). However, this practice has not yet been widely used as many oil-palm plantations in the province of Jambi (including those in our study area) are only on the verge of being replanted in the next decade.

In view of the large area (∼ 16 million hectares) under oil-palm cultivation in Indonesia (Gaveau et al., 2022), governments are interested in finding economically more lucrative applications for oil-palm residues (Awalludin et al., 2015; Chang, 2014; Rubinsin et al., 2020; Santi et al., 2019), including stems (Awalludin et al., 2015) that could boost the economy and benefit smallholder farmers. As a result, most research focusses on economically beneficial applications, e.g. in the renewable energy sector such as for fuel and gas production but also for production of composites and fertilizers (Onoja et al., 2019). A clear advantage of the current practice, i.e. spreading chipped stem parts across the plantation as an organic fertilizer, is that it supports the system's internal nutrient and Si cycling. This reduces the need to buy industrial fertilizers and avoids any costs and carbon dioxide emissions related to the transport of the stems. Selling the biomass waste for industrial purposes, the production of building materials (e.g. gypsum composites and wood fibre alternatives) (Selamat et al., 2019; Pratiwi et al., 2018; Dungani et al., 2013), or paper production (Pratiwi et al., 2018) would mean that farmers would have to compensate for the nutrient export from their plantations by buying more industrial fertilizers. In addition, both the transport of the palm stems from the plantations and the transport of fertilizers to the plantations would involve costs and carbon dioxide emissions.

In this study, we assessed the amounts of Si involved in internal Si cycling in the oil-palm system as well as the amounts of Si leaving the system through fruit-bunch harvest. Our study reconfirmed previous assumptions in that oil palms can be considered Si hyper-accumulators (mean Si concentration > 1 wt % in leaflets, Si / Ca mass ratio > 1). Mean Si concentrations increased with leaf age. A senescing frond stored 3 times the amount of Si in its leaf tissue compared to a mature palm frond. Total Si storage in the biomass of mature oil palms amounted to 551–682 kg ha−1. Oil-palm stems stored the greatest amounts of Si per hectare due to their large biomass. Therefore, keeping oil-palm stems (including frond bases) in the system could be an effective measure for maintaining balanced Si levels in the long term, i.e. over several oil-palm generations. In the short term, i.e. within one oil-palm generation, pruning and stacking palm fronds in frond piles turned out to be an effective management practice. This practice returned 111–131 kg Si per hectare and year to soils. Nevertheless, we found that fruit-bunch harvest involved a considerable annual Si export of 32–72 kg ha−1 from the system. Consequently, fertilization may be needed after several oil-palm generations. We recommend the following management measures that enhance Si cycling in the system: (1) ensuring a spatially more even Si return from decomposing palm fronds to soils, e.g. by changing the position of frond piles every 5–10 years, (2) returning empty fruit bunches to the palm circle to serve as organic fertilizer, and (3) leaving all the oil-palm residues on the plantation after a plantation cycle of 25 years, especially oil-palm stems (chopped and evenly distributed across the plantation), although the use of these residues for industrial purposes may be financially attractive to plantation owners.

Table B1Total Si and Ca concentrations in oil-palm parts and statistical analyses.

a n=3 as no senescing fronds were left hanging on palm trees (differing management practice on HOr2). Statistics were done with the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test and the Whitney–Mann U test. b WD: well-drained, RI: riparian. c Italic: not asserted.

Table B2Morphological characteristics of oil palms taken for sampling and Si accumulation in fruit bunches.

a WD and RI: well-drained and riparian areas. FB and FFB: fruit bunch and fresh fruit bunch. b Dry FB weight calculated after Corley et al. (1971). Si concentration in dry FB calculated by multiplying dry FB weight by mean Si concentrations of fruit-bunch components (stalk, fruit, kernel).

Data are provided in the Appendix of the paper.

BvdL and DS designed the study of the paper with input from HJH and AT. BG conducted plant sampling with input from BvdL and FB. MK and FB provided botanical and harvest data. FS conducted laboratory analyses with input from BvdL and BG. BG wrote the first draft. All the authors (BG, BvdL, FS, HJH, AT, MK, FB, and DS) contributed to generating and reviewing the subsequent versions of the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank the German Research Foundation (DFG, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) for funding this project and the Ministry of Education, Technology and Higher Education (RISTEKDIKTI) for granting research permission in Indonesia. Plant sampling was conducted using the research permit 187/ E5/E5.4/SIP/2019. Special thanks to the CRC 990 oil-palm smallholder partners, our Indonesian counterparts, the CRC-990 office members and our fieldwork assistants Nando and Toni in Jambi. We would also like to thank Jürgen Grotheer, Anja Södje, Petra Voigt, and Kerstin Diederich for their valuable help in the laboratory at the Institute of Geography, University of Göttingen.

This research has been supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG project grant 35 no. 391702217) and was associated with the Collaborative Research Centre (CRC)

990 “Ecological and Socioeconomic Functions of Tropical Lowland Rainforest Transformation Systems”

(CRC 990, DFG project no. 192626868).

This open-access publication was funded by the University of Göttingen.

This paper was edited by Yakov Kuzyakov and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Aholoukpè, H. N. S., Dubos, B., Deleporte, P., Flori, A., Amadji, L. G., Chotte, J. L., and Blavet, D.: Allometric equations for estimating oil palm stem biomass in the ecological context of Benin, West Africa, Trees, 32, 1669–1680, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-018-1742-8, 2018.

Albakri, Z. M., Saufi, M., Kassim, M., Abdullah, A. F., and Harith, H. H.: SCIENCE and TECHNOLOGY Analysis of Oil Palm Leaf Phyllotaxis towards Development of Models to Determine the Fresh Fruit Bunch (FFB) Maturity Stages, Yield and Site-Specific Harvesting, Pertanika J. Sci. Technol., 27, 659–672, 2019.

Alexandre, A., Meunier, J.-D., Colin, F., and Koud, J.-M.: Plant impact on the biogeochemical cycle of silicon and related weathering processes, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 61, 677–682, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(97)00001-X, 1997.

Allen, K., Corre, M. D., Kurniawan, S., Utami, S. R., and Veldkamp, E.: Spatial variability surpasses land-use change effects on soil biochemical properties of converted lowland landscapes in Sumatra, Indonesia, Geoderma, 284, 42–50, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.08.010, 2016.

Amirruddin, A. D., Muharam, F. M., and Mazlan, N.: Assessing leaf scale measurement for nitrogen content of oil palm: Performance of discriminant analysis and support vector machine classifiers, Int. J. Remote Sens., 38, 7260–7280, https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2017.1372862, 2017.

Awalludin, M. F., Sulaiman, O., Hashim, R., and Nadhari, W. N. A. W.: An overview of the oil palm industry in Malaysia and its waste utilization through thermochemical conversion, specifically via liquefaction, Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev., 50, 1469–1484, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.05.085, 2015.

Carey, J.: Soil age alters the global silicon cycle, Science, 369, 1161–1162, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd9425, 2020.

Carey, J. C. and Fulweiler, R. W.: The Terrestrial Silica Pump, PLoS One, 7, e52932, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052932, 2012.

Carey, J. C. and Fulweiler, R. W.: Human appropriation of biogenic silicon – the increasing role of agriculture, Funct. Ecol., 30, 1331–1339, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12544, 2016.

Chang, S. H.: An overview of empty fruit bunch from oil palm as feedstock for bio-oil production, Biomass Bioenerg., 62, 174–181, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2014.01.002, 2014.

Clough, Y., Krishna, V. v., Corre, M. D., Darras, K., Denmead, L. H., Meijide, A., Moser, S., Musshoff, O., Steinebach, S., Veldkamp, E., Allen, K., Barnes, A. D., Breidenbach, N., Brose, U., Buchori, D., Daniel, R., Finkeldey, R., Harahap, I., Hertel, D., Holtkamp, A. M., Hörandl, E., Irawan, B., Jaya, I. N. S., Jochum, M., Klarner, B., Knohl, A., Kotowska, M. M., Krashevska, V., Kreft, H., Kurniawan, S., Leuschner, C., Maraun, M., Melati, D. N., Opfermann, N., Pérez-Cruzado, C., Prabowo, W. E., Rembold, K., Rizali, A., Rubiana, R., Schneider, D., Tjitrosoedirdjo, S. S., Tjoa, A., Tscharntke, T., and Scheu, S.: Land-use choices follow profitability at the expense of ecological functions in Indonesian smallholder landscapes, Nat. Commun., 7, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13137, 2016.

Clymans, W., Struyf, E., Govers, G., Vandevenne, F., and Conley, D. J.: Anthropogenic impact on amorphous silica pools in temperate soils, Biogeosciences, 8, 2281–2293, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-8-2281-2011, 2011.

Clymans, W., Struyf, E., Van den Putte, A., Langhans, C., Wang, Z., and Govers, G.: Amorphous silica mobilization by inter-rill erosion: Insights from rainfall experiments, Earth Surf. Process. Landf., 40, 1171–1181, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.3707, 2015.

Conley, D. J., Likens, G. E., Buso, D. C., Saccone, L., Bailey, S. W., and Johnson, C. E.: Deforestation causes increased dissolved silicate losses in the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, Glob. Change Biol., 14, 2548–2554, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01667.x, 2008.

Corley, R. H. V. and Tinker, P. B.: The Oil Palm, 5th Edn., Wiley, 687 pp., https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781316530122.010, 2016.

Corley, R. H. V., Hardon, J. J., and Tan, G. Y.: Analysis of growth of the oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.), I. Estimation of growth parameters and application in breeding, Euphytica, 20, 307–315, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00056093, 1971.

De Coster, G. L.: The Geology of the central and south sumatra basins, 77–110, 1974.

Darras, K. F. A., Corre, M. D., Formaglio, G., Tjoa, A., Potapov, A., Brambach, F., Sibhatu, K. T., Grass, I., Rubiano, A. A., Buchori, D., Drescher, J., Fardiansah, R., Hölscher, D., Irawan, B., Kneib, T., Krashevska, V., Krause, A., Kreft, H., Li, K., Maraun, M., Polle, A., Ryadin, A. R., Rembold, K., Stiegler, C., Scheu, S., Tarigan, S., Valdés-Uribe, A., Yadi, S., Tscharntke, T., and Veldkamp, E.: Reducing Fertilizer and Avoiding Herbicides in Oil Palm Plantations – Ecological and Economic Valuations, Front. Forest. Glob. Change, 2, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2019.00065, 2019.

Datnoff, L. E., Deren, C. W., and Snyder, G. H.: Silicon fertilization for disease management of rice in Florida, Crop Prot., 16, 525–531, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-2194(97)00033-1, 1997.

de Tombeur, F., Turner, B. L., Laliberté, E., Lambers, H., Mahy, G., Faucon, M. P., Zemunik, G., and Cornelis, J. T.: Plants sustain the terrestrial silicon cycle during ecosystem retrogression, Science, 369, 1245–1248, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc0393, 2020.

Dislich, C., Keyel, A. C., Salecker, J., Kisel, Y., Meyer, K. M., Auliya, M., Barnes, A. D., Corre, M. D., Darras, K., Faust, H., Hess, B., Klasen, S., Knohl, A., Kreft, H., Meijide, A., Nurdiansyah, F., Otten, F., Pe'er, G., Steinebach, S., Tarigan, S., Tölle, M. H., Tscharntke, T., and Wiegand, K.: A review of the ecosystem functions in oil palm plantations, using forests as a reference system, Biol. Rev., 92, 1539–1569, https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12295, 2017.

Drescher, J., Rembold, K., Allen, K., Beckscha, P., Buchori, D., Clough, Y., Faust, H., Fauzi, A. M., Gunawan, D., Hertel, D., Irawan, B., Jaya, I. N. S., Klarner, B., Kleinn, C., Knohl, A., Kotowska, M. M., Krashevska, V., Krishna, V., Leuschner, C., Lorenz, W., Meijide, A., Melati, D., Steinebach, S., Tjoa, A., Tscharntke, T., Wick, B., Wiegand, K., Kreft, H., and Scheu, S.: Ecological and socio-economic functions across tropical land use systems after rainforest conversion, Philos. T. R. Soc. B, 371, 20150275, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0275, 2016.

Dungani, R., Jawaid, M., Khalil, H. P. S. A., Jasni, Aprilia, S., Hakeem, K. R., Hartati, S., and Islam, M. N.: A review on quality enhancement of oil palm trunk waste by resin impregnation: Future materials, Bioresources, 8, 3136–3156, https://doi.org/10.15376/biores.8.2.3136-3156, 2013.

Epstein, E.: The anomaly of silicon in plant biology, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 11–17, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.91.1.11, 1994.

Epstein, E.: Silicon: its manifold roles in plants, Ann. Appl. Biol., 155, 155–160, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7348.2009.00343.x, 2009.

Euler, M., Hoffmann, M. P., Fathoni, Z., and Schwarze, S.: Exploring yield gaps in smallholder oil palm production systems in eastern Sumatra, Indonesia, Agr. Sci. China, 146, 111–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2016.04.007, 2016a.

Euler, M., Schwarze, S., Siregar, H., and Qaim, M.: Oil Palm Expansion among Smallholder Farmers in Sumatra, Indonesia, J. Agr. Econ., 67, 658–676, https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-9552.12163, 2016b.

FAO: Oilseeds, Oils & Meals, Monthly Price and Policy Update No. 132, July 2020 (MPPU – issue no. 132, July 2020), 2020.

Fox, J. and Weisberg, S.: An { R} Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd Edn., Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage, https://socialsciences. mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion/ (last access: 8 February 2023), 2019.

Gaveau, D. L. A., Locatelli, B., Salim, M. A., Husnayaen, Manurung, T., Descals, A., Angelsen, A., Meijaard, E., and Sheil, D.: Slowing deforestation in Indonesia follows declining oil palm expansion and lower oil prices, PLoS One, 17, e0266178, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266178, 2022.

Grass, I., Kubitza, C., Krishna, V. v., Corre, M. D., Mußhoff, O., Pütz, P., Drescher, J., Rembold, K., Ariyanti, E. S., Barnes, A. D., Brinkmann, N., Brose, U., Brümmer, B., Buchori, D., Daniel, R., Darras, K. F. A., Faust, H., Fehrmann, L., Hein, J., Hennings, N., Hidayat, P., Hölscher, D., Jochum, M., Knohl, A., Kotowska, M. M., Krashevska, V., Kreft, H., Leuschner, C., Lobite, N. J. S., Panjaitan, R., Polle, A., Potapov, A. M., Purnama, E., Qaim, M., Röll, A., Scheu, S., Schneider, D., Tjoa, A., Tscharntke, T., Veldkamp, E., and Wollni, M.: Trade-offs between multifunctionality and profit in tropical smallholder landscapes, Nat. Commun., 11, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15013-5, 2020.

Grasshoff, K., Kremling, K., and Ehrhardt, M.: Methods of sea water analysis, 3rd Edn., John Wiley & Sons, 899 pp., https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4203(78)90045-2, 2009.

Greenshields, B., von der Lühe, B., Hughes, H. J., Stiegler, C., Tarigan, S., Tjoa, A., and Sauer, D.: Oil-palm management alters the spatial distribution of amorphous silica and mobile silicon in topsoils, SOIL, 9, 169–188, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-9-169-2023, 2023.

Guntzer, F., Keller, C., Poulton, P. R., McGrath, S. P., and Meunier, J. D.: Long-term removal of wheat straw decreases soil amorphous silica at Broadbalk, Rothamsted, Plant Soil, 352, 173–184, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-011-0987-4, 2012.

Haynes, R. J.: A contemporary overview of silicon availability in agricultural soils, J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci., 177, 831–844, https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.201400202, 2014.

Haynes, R. J.: The nature of biogenic Si and its potential role in Si supply in agricultural soils, Agr. Ecosyst. Environ., 245, 100–111, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.04.021, 2017.

Heinrichs, H. and Hermann, A. G.: Praktikum der Analytischen Geochemie, in: Lehrbuch, Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-61286-2, 1990.

Heinrichs, H., Brumsack, H. J., Loftfield, N., and König, N.: Verbessertes Druckaufschlußsystem für biologische und anorganische Materialien, Z. Pflanz. Bodenkunde, 149, 350–353, 1986.

Hennings, N., Becker, J. N., Guillaume, T., Damris, M., Dippold, M. A., and Kuzyakov, Y.: Riparian wetland properties counter the effect of land-use change on soil carbon stocks after rainforest conversion to plantations, Catena, 196, 104941, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2020.104941, 2021.

Hughes, H. J., Hung, D. T., and Sauer, D.: Silicon recycling through rice residue management does not prevent silicon depletion in paddy rice cultivation, Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst., 118, 75–89, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-020-10084-8, 2020.

IUSS Working Group WRB: World Reference Base or Soil Resources 2014, update 2015 International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps, FAO, Rome, 4th Edn., International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS), Vienna, Austria, 1–191, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479706394902, 2022.

Klotzbücher, T., Klotzbücher, A., Kaiser, K., Merbach, I., and Mikutta, R.: Impact of agricultural practices on plant-available silicon, Geoderma, 331, 15–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.06.011, 2018.

Kotowska, M. M., Leuschner, C., Triadiati, T., Meriem, S., and Hertel, D.: Quantifying above- and belowground biomass carbon loss with forest conversion in tropical lowlands of Sumatra (Indonesia), Glob. Change Biol., 21, 3620–3634, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12979, 2015.

Laumonier, Y.: The Vegetation and Physiography of Sumatra, in: Geobotany, Vol. 22, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 223, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-0031-8, 1997.

Lewis, K., Rumpang, E., Kho, L. K., McCalmont, J., Teh, Y. A., Gallego-Sala, A., and Hill, T. C.: An assessment of oil palm plantation aboveground biomass stocks on tropical peat using destructive and non-destructive methods, Sci. Rep., 10, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58982-9, 2020.

Li, Z. and Delvaux, B.: Phytolith-rich biochar: A potential Si fertilizer in desilicated soils, GCB Bioenergy, 11, 1264–1282, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcbb.12635, 2019.

Li, Z., de Tombeur, F., Vander Linden, C., Cornelis, J. T., and Delvaux, B.: Soil microaggregates store phytoliths in a sandy loam, Geoderma, 360, 114037, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.114037, 2020.

Liang, Y., Nikolic, M., Bélanger, R., Gong, H., and Song, A.: Silicon in Agriculture, Springer, Dordrecht, 235 pp., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9978-2, 2015.

Lucas, Y., Luizão, F. J., Chauvel, A., Rouiller, J., and Nahon, D.: The relation between biological activity of the rain forest and mineral composition of soils, Science, 260, 521–523, 1993.

Luke, S. H., Purnomo, D., Advento, A. D., Aryawan, A. A. K., Naim, M., Pikstein, R. N., Ps, S., Rambe, T. D. S., Soeprapto, Caliman, J.-P., Snaddon, J. L., Foster, W. A., and Turner, E. C.: Effects of understory vegetation management on plant communities in oil palm plantations in Sumatra, Indonesia, Front. Forest. Glob. Change, 2, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2019.00033, 2019.

Ma, J. F. and Takahashi, E.: Silicon-accumulating plants in the plant kingdom, in: Soil, fertilizer, and plant silicon research in Japan, Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, Elsevier, 63–71, https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-044451166-9/50005-1, 2002.

Meijaard, E., Brooks, T., Carlson, K. M., Slade, E. M., and Ulloa, J. G.: The environmental impacts of palm oil in context, Nat. Plants, 6, 1418–1426, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-020-00813-w, 2020.

Munevar, F. and Romero, A.: Soil and plant silicon status in oil palm crops in Colombia, Exp. Agric., 51, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479714000374, 2015.

Ollivier, J., Flori, A., Cochard, B., Amblard, P., Turnbull, N., Syahputra, I., Suryana, E., Lubis, Z., Surya, E., Sihombing, E., and Gasselin, D. T.: Genetic variation in nutrient uptake and nutrient use efficiency of oil palm, J. Plant. Nutr., 40, 558–573, https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2016.1262415, 2017.

Omar, F. N., Mohammed, M. A. P., and Baharuddin, A. S.: Effect of silica bodies on the mechanical behaviour of oil palm empty fruit bunch fibres, Bioresources, 9, 7041–7058, https://doi.org/10.15376/biores.9.4.7041-7058, 2014.

Onoja, E., Chandren, S., Abdul Razak, F. I., Mahat, N. A., and Wahab, R. A.: Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis) Biomass in Malaysia: The Present and Future Prospects, Waste Biomass Valori., 10, 2099–2117, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-018-0258-1, 2019.

Pratiwi, W., Sugiharto, A., and Sugesty, S.: The effect of pulping process variable and elemental chlorine free bleaching on the quality of oil palm trunk pulp, Jurnal Selulosa, 8, 85–94, https://doi.org/10.25269/jsel.v8i02.218, 2018.

Puppe, D., Kaczorek, D., Schaller, J., Barkusky, D., and Sommer, M.: Crop straw recycling prevents anthropogenic desilication of agricultural soil–plant systems in the temperate zone – Results from a long-term field experiment in NE Germany, Geoderma, 403, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2021.115187, 2021.

Qaim, M., Sibhatu, K. T., Siregar, H., and Grass, I.: Environmental, Economic, and Social Consequences of the Oil Palm Boom, Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ., 12, 1–24, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-110119-024922, 2020.

Rees, A. R.: The apical organization and phyllotaxis of the oil palm, Ann. Bot., 28, 57–69, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a083895, 1964.,

Revelle, W.: psych: Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, USA, 2022.

Rubinsin, N., Daud, W. R. W., Kamarudin, S. K., Masdar, M. S., Rosli, M. I., Samsatli, S., Tapia, J. F., Wan Ab Karim Ghani, W. A., and Lim, K. L.: Optimization of oil palm empty fruit bunches value chain in peninsular malaysia, Food Bioprod. Process., 119, 179–194, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbp.2019.11.006, 2020.

Saccone, L., Conley, D. J., Koning, E., Sauer, D., Sommer, M., Kaczorek, D., Blecker, S. W., and Kelly, E. F.: Assessing the extraction and quantification of amorphous silica in soils of forest and grassland ecosystems, Eur. J. Soil Sci., 58, 1446–1459, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2007.00949.x, 2007.

Santi, L. P., Kalbuadi, D. N., and Goenadi, D. H.: Empty fruit bunches as potential source for biosilica fertilizer for oil palm, J. Trop. Biodivers. Biotechnol., 4, 90–96, https://doi.org/10.22146/jtbb.38749, 2019.

Schaller, J., Turner, B. L., Weissflog, A., Pino, D., Bielnicka, A. W., and Engelbrecht, B. M. J.: Silicon in tropical forests: large variation across soils and leaves suggests ecological significance, Biogeochemistry, 140, 161–174, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-018-0483-5, 2018.

Selamat, M. E., Hashim, R., Sulaiman, O., Kassim, M. H. M., Saharudin, N. I., and Taiwo, O. F. A.: Comparative study of oil palm trunk and rice husk as fillers in gypsum composite for building material, Constr. Build. Mater., 197, 526–532, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.003, 2019.

Struyf, E., Smis, A., Van Damme, S., Garnier, J., Govers, G., Van Wesemael, B., Conley, D. J., Batelaan, O., Frot, E., Clymans, W., Vandevenne, F., Lancelot, C., Goos, P., and Meire, P.: Historical land use change has lowered terrestrial silica mobilization, Nat. Commun., 1, 127–129, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1128, 2010.

Tarigan, S., Stiegler, C., Wiegand, K., Knohl, A., and Murtilaksono, K.: Relative contribution of evapotranspiration and soil compaction to the fluctuation of catchment discharge: case study from a plantation landscape, Hydrol. Sci. J., 65, 1239–1248, https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2020.1739287, 2020.

Tsujino, R., Yumoto, T., Kitamura, S., Djamaluddin, I., and Darnaedi, D.: History of forest loss and degradation in Indonesia, Land Use Policy, 57, 335–347, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.05.034, 2016.

vander Linden, C. and Delvaux, B.: The weathering stage of tropical soils affects the soil-plant cycle of silicon, but depending on land use, Geoderma, 351, 209–220, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.05.033, 2019.

Vandevenne, F., Struyf, E., Clymans, W., and Meire, P.: Agricultural silica harvest: have humans created a new loop in the global silica cycle?, Front. Ecol. Environ., 10, 243–248, https://doi.org/10.1890/110046, 2012.

von der Lühe, B., Pauli, L., Greenshields, B., Hughes, H. J., Tjoa, A., and Sauer, D.: Transformation of Lowland Rainforest into Oil-palm Plantations and use of Fire alter Topsoil and Litter Silicon Pools and Fluxes, Silicon, 13, 4345–4353, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-020-00680-2, 2020.

von der Lühe, B., Bezler, K., Hughes, H. J., Greenshields, B., Tjoa, A., and Sauer, D.: Oil-palm and Rainforest Phytoliths Dissolve at Different Rates – with Implications for Silicon Cycling After Transformation of Rainforest Into Oil-palm Plantation, Silicon, 1347–1354, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-022-02066-y, 2022.

Wickham, H.: ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, Springer-Verlag New York, 2016.

Woittiez, L. S., van Wijk, M. T., Slingerland, M., van Noordwijk, M., and Giller, K. E.: Yield gaps in oil palm: A quantitative review of contributing factors, Europ. J. Agron., 83, 57–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2016.11.002, 2017.

Woittiez, L. S., Slingerland, M., Rafik, R., and Giller, K. E.: Nutritional imbalance in smallholder oil palm plantations in Indonesia, Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst., 111, 73–86, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-018-9919-5, 2018.

Zellner, W., Tubaña, B., Rodrigues, F. A., and Datnoff, L. E.: Silicon's Role in Plant Stress Reduction and Why This Element Is Not Used Routinely for Managing Plant Health, Plant Dis., 105, 2033–2049, https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-08-20-1797-FE, 2021.