the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Climatic controls on leaf wax hydrogen isotope ratios in terrestrial and marine sediments along a hyperarid-to-humid gradient

Nestor Gaviria-Lugo

Charlotte Läuchli

Hella Wittmann

Anne Bernhardt

Patrick Frings

Mahyar Mohtadi

Oliver Rach

Dirk Sachse

The hydrogen isotope composition of leaf wax biomarkers (δ2Hwax) is a valuable tool for reconstructing continental paleohydrology, since it serves as a proxy for the hydrogen isotope composition of precipitation (δ2Hpre). To yield robust palaeohydrological reconstructions using δ2Hwax in marine archives, it is necessary to examine the impacts of regional climate on δ2Hwax and assess the similarity between marine sedimentary δ2Hwax and the source of continental δ2Hwax. Here, we examined an aridity gradient from hyperarid to humid along the Chilean coast. We sampled sediments at the outlets of rivers draining into the Pacific as well as soils within catchments and marine surface sediments adjacent to the outlets of the studied rivers and analyzed the relationship between climatic variables and δ2Hwax values. We found that apparent fractionation between leaf waxes and source water is relatively constant in humid and semiarid regions (average: −121 ‰). However, it becomes less negative in hyperarid regions (average: −86 ‰) as a result of evapotranspirative processes affecting soil and leaf water 2H enrichment.

We also observed that along strong aridity gradients, the 2H enrichment of δ2Hwax follows a non-linear relationship with water content and water flux variables, driven by strong soil evaporation and plant transpiration. Furthermore, our results indicate that δ2Hwax values in marine surface sediments largely reflect δ2Hwax values from the continent, confirming the robustness of marine δ2Hwax records for paleohydrological reconstructions along the Chilean margin. These findings also highlight the importance of considering the effects of hyperaridity in the interpretation of δ2Hwax values and pave the way for more quantitative paleohydrological reconstructions using δ2Hwax.

- Article

(5604 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The assessment of changes in paleohydrology is crucial for reconstructing a complete picture of paleoclimate. Paleohydrological changes can be inferred with multiple proxies, including pollen analyses, oxygen stable isotopes from foraminifera, hydrogen and oxygen stable isotopes from ice cores, stable isotopes in tree ring cellulose, and leaf wax n-alkanes and their stable carbon and hydrogen isotope ratios (expressed here as δ2Hwax) (Dansgaard et al., 1993; Eglinton and Eglinton, 2008; Epstein et al., 1977; Francey and Farquhar, 1982; Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005; Longinelli, 1984; North Greenland Ice Core Project members, 2004; Sachse et al., 2012). Among these proxies, leaf-wax-derived long-chain n-alkanes and δ2Hwax values have proven particularly useful for reconstructing changes in continental paleohydrology (Niedermeyer et al., 2010; Pagani et al., 2006; Rach et al., 2014; Schefuß et al., 2005; Tierney et al., 2008; Collins et al., 2017), because of their long-term preservation potential, their source specificity, and their ubiquitous presence in sedimentary archives.

δ2Hwax values reflect the hydrogen isotopic composition of local precipitation (δ2Hpre). Studies of modern plants, soils, and lake surface sediments have shown that δ2Hwax and δ2Hpre are highly correlated, and that δ2Hpre is generally the primary control on δ2Hwax (Polissar and Freeman, 2010; Rao et al., 2009; Sachse et al., 2004, 2006, 2012; Sessions et al., 1999). Hence, δ2Hwax values are considered a high-fidelity recorder of δ2Hpre, and consequently of the processes affecting δ2Hpre values. In mid-to-high latitudes δ2Hpre values are controlled by distance from the coastline (continentality/rainout effect) and changes in temperature of the air masses, in turn controlled by elevation and latitude effects (Bowen et al., 2019; Craig, 1961; Dansgaard, 1964; Gat, 1996; Rozanski et al., 1993). In tropical regions, δ2Hpre values primarily respond to rainfall amount (Hoffmann et al., 2003; Kurita et al., 2009; Vuille and Werner, 2005). Beyond this, moisture source is another important factor dictating the isotopic signature of precipitation (Tian et al., 2007; Uemura et al., 2008; Vimeux et al., 1999, 2001).

Before being incorporated into leaf waxes, δ2Hpre values are modified by biosynthetic processes inside plants and ecohydrological processes such as evapotranspiration. The net effect of these fractionations is such that δ2Hwax is significantly depleted in deuterium relative to the source water δ2Hpre, with the depletion commonly referred to as “net or apparent fractionation” (expressed here as ) (Cernusak et al., 2016; Dawson et al., 2002; Kahmen et al., 2013a, b; Smith and Freeman, 2006). Commonly estimated values of generally average around −120 ‰ (Sachse et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2022). Yet, values can be affected by the type of plant communities sourcing the n-alkanes. Generally, values are higher in C3 plants than in C4 plants (Chikaraishi et al., 2004; Kahmen et al., 2013b; Sachse et al., 2010, 2012; Smith and Freeman, 2006). It has been suggested that these differences originate due to specific discrimination against 2H between distinct photosynthetic pathways (Chikaraishi et al., 2004), as well as due to different pools of biosynthetic source waters fed by different mixtures of enriched leaf water and unenriched soil water (Kahmen et al., 2013a), or due to both processes. Moreover, studies analyzing plants by growth form (Griepentrog et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2016) or even at the species level (Gao et al., 2014) show a strong control of vegetation type or species on , explained by physiological and biochemical factors that vary among different plant taxa (Gao et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016). In addition to the vegetation effects, it has been identified that values become higher as aridity intensifies (Douglas et al., 2012; Feakins and Sessions, 2010; Garcin et al., 2012; Goldsmith et al., 2019; Herrmann et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019; Polissar and Freeman, 2010; Smith and Freeman, 2006). However, prior research has primarily been confined to regions with an aridity index ≥ 0.05, i.e., arid, semiarid, dry–subhumid, and humid regions, where aridity index is defined as the ratio of mean annual precipitation to potential evapotranspiration (after. UNEP, 1997), leaving hyperarid zones (aridity index < 0.05) understudied. To improve our understanding of the climatic controls on δ2Hwax and , it is necessary to examine the impact of hyperaridity and the extent to which hydrological parameters influence δ2Hwax. This information is necessary to maximize the accuracy of paleohydrological reconstructions and eventually develop them into quantitative tools.

In addition to these knowledge gaps, δ2Hwax values from sedimentary archives may or may not reflect the entire source region due to filtering during sediment transit through sedimentary systems. Häggi et al. (2016) showed that δ2Hwax from suspended sediments in the Amazon River and δ2Hwax from marine surface sediments have equivalent values limited to the Amazon freshwater plume, with δ2Hwax values disagreeing beyond this area. Along the Italian Adriatic coast, marine and terrestrial sediments display equivalent δ2Hwax values on the semiarid side of the peninsula, but not in the humid regions (Leider et al., 2013). Vogts et al. (2012) showed that δ13Cwax values from marine sediments correlate with δ13Cwax values from terrestrial plants along a humid-to-arid transect offshore southwest Africa. However, the current understanding of the possible filter effects on leaf wax proxy data within sedimentary systems from source to sink remains incomplete. Hence, paired marine–continental sampling approaches would represent a step toward addressing these issues.

In this study, we analyze leaf wax n-alkanes and their δ2Hwax values in marine surface sediments, modern soils, and river sediments along a strong aridity gradient in Chile. The gradient spans from the humid to the hyperarid zones and encompasses a range of annual mean precipitation values from 6 to 2300 mm yr−1 (Fig. 1). We examine how climatic factors (evapotranspiration, precipitation, aridity, relative humidity, soil moisture, temperature) impact δ2Hwax and , and assess the similarity of δ2Hwax values of soils, riverine and marine sediments across the aridity zones of the aridity gradient. We provide a better and quantitative understanding of the effects of aridity on δ2Hwax values and a foundation for the application of δ2Hwax in paleohydrological reconstructions along aridity gradients, in particular along the Chilean aridity gradient.

2.1 Study area and sampling strategy

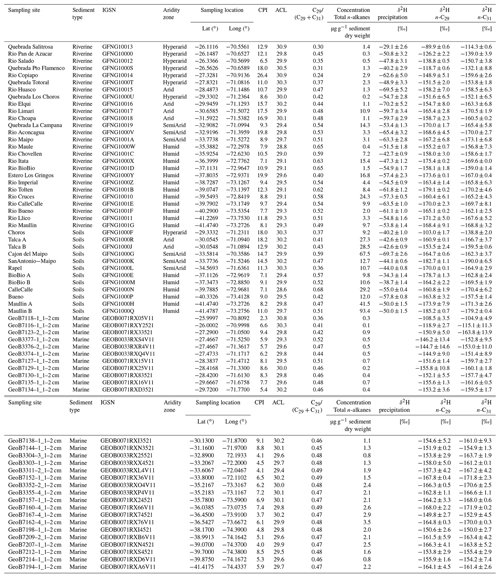

Here we study a gradient from hyperarid to humid along Chile, using soils, river sediments, and marine surface sediments (Fig. 1). During March–April 2019 we sampled topsoils (upper 5 cm, n=12) and riverbed sediments (n=26) from catchments draining to the Pacific Ocean. Three small sub-catchments nested in three of the major catchments were also sampled. Marine core-top sediments (1–2 cm core depth, 29 sites, Table 1) were provided by the MARUM core repository. Marine samples used in this study were recovered during expeditions SO-102 and SO-156 of the RV SONNE using a multicorer (Hebbeln, 1995, 2001).

Figure 1Maps of climatic conditions and sampling locations along the studied gradient. (a) Aridity index (dimensionless quantity) with sampling locations and studied catchments. Aridity index data are from the Global Aridity Index and Potential Evapotranspiration Climate Database v3 of Trabucco and Zomer (2022), and aridity zone classification follows the classification proposed by UNEP (1997). (b) Long-term (1958–2015) mean annual actual evapotranspiration (AET; mm yr−1) from the TerraClimate dataset of Abatzoglou et al. (2018). (c) Mean annual hydrogen isotopic composition of precipitation (δ2Hpre, in ‰), from The Online Isotopes in Precipitation Calculator, version 3.1.

2.2 Analytical methods

2.2.1 Sample preparation

Prior to extraction of the organic compounds, samples from river and soil sediment were dried for 48 h in an oven at 60 ∘C. Any visible plant material was carefully extracted using steel tweezers, and the samples were sieved to < 32 µm. Marine surface sediments were freeze-dried for 48 h and homogenized using an agate mortar.

2.2.2 Lipid extraction and chromatography

Organic lipids were extracted from ∼ 20 g of sediment and purified using the manual solid phase extraction (SPE) procedure described by Rach et al. (2020). In brief, a Dionex Accelerated Solvent Extraction system (ASE 350, ThermoFisher Scientific) using a dichloromethane (DCM) : methanol (MeOH) mixture (9:1, ) at 100 ∘C, 103 bar pressure with two extraction cycles (20 min static time) was used to extract total lipid extracts (TLE). These were collected in a combusted glass vial and then completely evaporated under a stream of nitrogen. All samples were spiked with 10 µg of an internal standard (5α-androstane) and the TLE was separated into aliphatic, aromatic, and alcohol fatty acid fractions by SPE in 8 mL glass columns filled with 2 g silica gel using Hexane, Hexane:DCM (1:1), and DCM : Methanol (1:1) as solvents. The aliphatic fraction was desulfurized by elution through activated copper powder, and then additionally cleaned over silver nitrate-coated silica gel.

Identification and quantification of n-alkanes were performed on an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph (GC) coupled to a flame ionization detector (FID) and to an Agilent 5975C mass spectrometer (MS). The GC was equipped with a 30 m Agilent DB-5MS UI column (0.25 µm film thickness, 25 mm diameter). We used the internal standard to normalize the peak areas of the n-alkanes in the chromatogram. The internal standard was spiked into the sample after extracting the TLE from the sediments, but before performing the separation of the TLE through SPE. This allowed us to compare the relative abundance of the n-alkanes in different samples, while accounting for any losses that may have occurred during SPE. Quantification results were normalized to their initial dry weight and are reported as µg g−1 dry weight. The uncertainty of the δ2Hwax values was calculated using the standard deviation between the duplicate measurements of each sample.

2.2.3 Hydrogen isotope analysis

Stable hydrogen isotope ratios (δ2H) from the n-alkanes were measured in the separated aliphatic fractions using a Trace GC 1310 (ThermoFisher Scientific) connected to a Delta V plus Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IRMS) (ThermoFisher Scientific). The GC was equipped with a 30 m Agilent DB-5MS UI column (0.25 µm film thickness, 25 mm diameter). n-alkane δ2H values were determined by duplicate measurements. We followed the same GC oven program as described by Rach et al. (2014). The H factor was measured before each sequence and averaged 2.82 ± 0.14 mV (n=6) over a period of 5 weeks. To correct and transfer to the VSMOW scale, an n-alkane standard-mix A6 (n-C16 to n-C30) with known δ2H values obtained from A. Schimmelmann (Indiana University) was measured before and after the samples.

2.3 n-Alkane indices

To assess variations in the n-alkane distributions along the Chilean gradient, we calculated the carbon preference index (CPI) and the average chain length (ACL) indices. The CPI measures the relative abundances of odd- vs. even-numbered n-alkanes, using the concentrations of odd- and even-numbered n-alkane chains from n-C25 to n-C35 following Marzi et al. (1993):

The ACL value is the weighted average of the various carbon chain lengths in a sample:

2.4 Global δ2Hwax data compilation

The compiled dataset is accessible from the Gaviria-Lugo et al. (2023) data publication and can be correspondently used and cited. We used the previously published δ2Hwax datasets of soils and lake sediments of Ladd et al. (2021) and Chen et al. (2022), but significantly expanded these compilations with newer datasets reporting δ2Hwax for both n-C29 and n-C31. In total, our compilation includes data from 26 peer-reviewed publications, with 750 and 663 δ2Hwax values for n-C29 and n-C31, respectively (Table S1 in the Supplement).

2.5 Remote sensing data and GIS methods

2.5.1 δ2H of precipitation

δ2Hpre was extracted from the grids produced by Bowen and Revenaugh (2003), which are publicly available at the Online Isotopes in Precipitation Calculator webpage (OIPC, The Online Isotopes in Precipitation Calculator, version 3.1). We used the raster grid of annual averaged δ2Hpre data from the OIPC to calculate the δ2Hpre values for each location in our study area and from the global compilation. The raster grid data were provided at a resolution of ∼ 9 km, with each pixel corresponding to an area of ∼ 81 km2. To assess the accuracy of OIPC δ2Hpre values at our sampling sites, we compare the values predicted by the OIPC, extracted on a monthly basis, with a dataset comprising 923 measured data points of δ2Hpre. This dataset was obtained from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA/WMO, 2023), collected as part of the Global Network of Isotopes in Precipitation (GNIP) program at nine long-term monitoring stations located along the different aridity zones of continental Chile.

2.5.2 Climatic parameters

Hydrological variables were obtained from the TerraClimate dataset (Abatzoglou et al., 2018) as long-term annual averages for the period between 1958 and 2019 at ∼ 4.5 km spatial resolution, with each pixel representing ∼ 20 km2. Variables obtained from the dataset were mean annual precipitation (MAP), actual evapotranspiration (AET), soil moisture (SM), actual vapor pressure (VAP), and vapor pressure deficit (VPD); the last two were used to derive relative humidity (RH) using Eq. (3):

The TerraClimate dataset was accessed and analyzed using the cloud computing capabilities publicly available via Google Earth Engine. Aridity index (AIdx) data were accessed from the Consultative Group of the International Agricultural Research Consortium for Spatial Information (CGIARCSI) Global-Aridity Index dataset (Trabucco and Zomer, 2022) that integrates aridity over the period 1970–2000 at a resolution of ∼ 1 km, with each pixel corresponding to ∼ 1 km2. The WorldClim dataset (Fick and Hijmans, 2017) was used to derive the mean annual temperature (MAT) and annual average of daily maximum temperature (MaxT), based on data from 1970–2000 with a resolution of ∼ 1 km, corresponding to ∼ 1 km2 per pixel.

2.5.3 Vegetation cover

Fractional land cover data were obtained from Collection 2 of the Copernicus Global Land Cover layers (Buchhorn et al., 2020) via Google Earth Engine. We extracted mean values for the fraction of trees, shrubs, grasses, crops, and barren land for the period 2015–2019 at a 100 m resolution, with each pixel representing 0.01 km2. We used land cover fractions of vegetation obtained for each site to derive values of the fraction of herbaceous vegetation and woody vegetation. To derive the woody fraction of the vegetation, we summed the values of trees and shrubs land cover and divided this sum by the sum of all the vegetation fractions (trees, shrubs, grasses, crops). The values of the herbaceous fraction of the vegetation were derived summing the values of grasses and crops and dividing this sum by the sum of all the vegetation fractions (trees, shrubs, grasses, crops).

2.5.4 Spatial analysis

Catchments were defined upstream of the sampling points of river sediments using the drainagebasins function from the MATLAB-based software TopoToolbox 2 (Schwanghart and Scherler, 2014). The digital elevation model (DEM) used for the drainage basin definition in this study was the freely available Copernicus WorldDEM with a resolution of 30 m (Fahrland et al., 2020). For each catchment area, we calculated a mean value of δ2Hpre, the climatic parameters, and vegetation cover fractions (Table S6) of all grid cells within the catchment. Soil samples were considered as points, and in this case we extracted the values of δ2Hpre, the climatic parameters, and vegetation cover fractions from the pixel containing the sampling point (Table S6 in the Supplement). For the compiled global dataset, all soil samples were also treated as points, and drainage basins were defined for lake sediment samples using the same procedure as for the Chilean river samples. Values for δ2Hpre and all climatic parameters were retrieved using the same procedures and the same sources as for our sampling sites in Chile (Table S1).

2.6 Statistical and mathematical methods

2.6.1 δ2Hwax vs. δ2Hpre regression and analysis of residuals

Using the R programming language, we conducted a linear regression between the global compilation of δ2Hwax values and their corresponding δ2Hpre values retrieved from the OIPC. This global regression serves as an indicator of the expected relationship between δ2Hwax and δ2Hpre. To assess the influence of fractionation processes on δ2Hwax along the Chilean gradient, we calculated the residuals between measured δ2Hwax and predictions from the global regression for our sampling sites. As δ2Hpre is assumed to be the primary determinant of δ2Hwax, any substantial deviations from the global regression may suggest the presence of additional fractionation processes.

2.6.2 Statistical test of the differences between medians of groups (Kruskal–Wallis test)

The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to statistically test the hypothesis that the median δ2Hwax values are similar among the different aridity zones and sediment types. This non-parametric test does not make any assumptions about the distribution of the data, and using the median instead of the mean helps to avoid errors induced by outliers in the data. If the p value of the test is < 0.05, then the null hypothesis must be rejected, indicating a statistically significant difference between the medians of the groups (Kruskal and Wallis, 1952). We performed the test using the function kruskal.test of the stats package version 4.2.1 from the R programming language (R Core Team, 2022).

2.6.3 Leaf wax hydrogen isotope fractionation

We calculated the difference between δ2Hpre values as source water and δ2Hwax values to assess the climatic parameters that control δ2Hwax along the gradient. This difference is referred to as the “net or apparent fractionation”, as it encompasses several fractionation processes, such as the evaporation and enrichment of soil water, the enrichment of leaf water through transpiration, and the biosynthesis of lipids (Sessions et al., 1999; Smith and Freeman, 2006; Farquhar et al., 2007; Sachse et al., 2012). We used the isotopic fractionation factor (α) instead of the apparent fractionation in permil (ε ‰) to derive accurate regressions and to be mathematically consistent according to the theory of compositional data analysis (Aitchison, 1982, 1986), but reported all values as ε (in ‰) for the sake of comparison with other studies. Since α is the ratio of the isotopic composition of two substances, it enables application of the log-ratio approach when studying the factors affecting fractionation. Using log ratios is the preferred approach to yield mathematically and statistically robust regression models for compositional data (Aitchison, 1982, 1986; Ramisch et al., 2018; Weltje et al., 2015).

To obtain the fractionation factor α, delta values were transformed back to isotopic ratios from the permil scale using Eqs. (4) and (5). The apparent fractionation is related to the isotopic fractionation factor through Eq. (6). For comparison with existing literature data, apparent fractionation values in permil can be obtained multiplying Eq. (6) by 1000.

To explore the environmental controls on fractionation, we fitted ordinary least squares regression models between the natural log of the isotopic fractionation factor and the natural log of the environmental parameters of interest. The type of linear model obtained is represented by Eq. (7). To back-transform this type of model from the log space to the original space, we applied an exponential function to both sides of Eq. (7) to obtain a model in the form of Eq. (8):

2.6.4 Soil and leaf water enrichment models

To mechanistically understand how evapotranspirative 2H enrichment with respect to source water regulates δ2Hwax, it is advantageous to model the effect of this process considering its two primary components: (1) soil water 2H enrichment due to evaporation and (2) leaf water 2H enrichment due to transpiration. To model soil water 2H enrichment we used a simplified Craig–Gordon model based on the modifications of Gat (1995) and followed the parameterization of Smith and Freeman (2006). The soil water is treated as a through-flow reservoir at hydrologic and isotopic steady state. The 2H enrichment (Δ2HSW) is predicted for each site using Eq. (9) based on relative humidity (RH), and the ratio between precipitation (MAP) and evaporated soil water (SEv). RH and MAP data come from the retrieved values for each site (Sect. 2.5.2; Table S6). The equilibrium isotope fractionation factor between vapor and liquid (ε*) is calculated as a function of temperature following the empirical relation derived by Horita and Wesolowski (1994).

The value of SEv is derived from AET from Eq. (10), in which the soil evaporation factor (fe) reflects the contribution of soil evaporation to AET. This factor fe varies along the aridity gradient.

It is known that the contribution of (soil) evaporation to AET is higher in arid regions compared to humid regions (Lawrence et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2016). According to Lehmann et al. (2019), in arid regions, only 13 % of the precipitated water is shielded from evaporation, and this percentage decreases to 2.3 % in hyperarid regions. Based on these values, which consider evaporation not only from soils but also from water bodies, we assume conservative fe values of 0.8 for arid regions and 0.9 for hyperarid regions. The present study does not model the contribution of soil evaporation to 2H enrichment in humid regions, as it is typically less significant than transpiration in such regions (Schlesinger and Jasechko, 2014; Zhang et al., 2016).

Leaf water enrichment is modeled using the Péclet modified Craig–Gordon model proposed by Kahmen et al. (2011) for δ18O values, adjusted for δ2H values as in Rach et al. (2017). Based on Eq. (11), this model first estimates leaf water 2H enrichment (Δ2HLW) considering ε* (defined as for the soil evaporation model), the kinetic isotope fractionation during water vapor diffusion from the leaf intercellular air space to the atmosphere (εk), the 2H enrichment of water vapor relative to source water (Δ2HWV), and the ratio of atmospheric vapor pressure and leaf internal vapor pressure ().

As in Eq. (12), εk is dependent on two parameters that are considered constant: leaf boundary layer resistance (rb=1 mol m−2 s−1) and stomatal conductance (gs=0.1 mol−1 m2 s) which is formulated as stomatal resistance .

The magnitude of Δ2HWV (Eq. 13) is considered the same as ε*, as demonstrated by long-term observations in temperate regions (Jacob and Sonntag, 1991).

Leaf internal vapor pressure (ei; Eq. 14) is dependent on leaf temperature (Tleaf), which is considered to be the same as air temperature (Tair) over decadal timescales of sedimentary integration (Rach et al., 2017). Saturation vapor pressure (esat; Eq. 15) depends on Tair and atmospheric pressure (eatm) at each site. With the value of esat, we calculate the atmospheric vapor pressure (ea; Eq. 16).

The final component of the model involves the utilization of the Péclet number (℘) to adjust for physiological factors that can influence leaf water enrichment. The calculation of ℘ entails the preliminary estimation of the transpirational water flux (Tr; Eq. 17) and water diffusivity (Diff; Eq. 18).

For the calculation of ℘ (Eq. 19), path length (LM=15 mm) and the molar concentration of water ( mol m−3) are considered constant, following Kahmen et al. (2011). After obtaining ℘, the final Peclét corrected leaf water 2H enrichment values (Δ2HLWP; Eq. 20) can be calculated.

3.1 Concentration and distribution of leaf wax n-alkanes along the Chilean aridity gradient

3.1.1 Concentration and distribution of n-alkanes in river sediments and soils

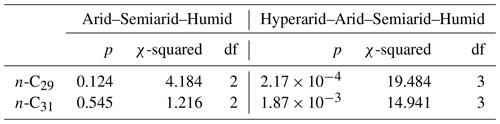

In both soils and riverine sediments, n-alkane distributions exhibited a strong predominance of odd over even chain length n-alkanes with a CPI between 6.5 and 26.4 (Table 1). Total concentrations of n-alkanes in riverine sediments ranged from 0.2 µg g−1 sediment dry weight (dw) to 24.3 µg g−1 dw. Total concentrations of n-alkanes in soils ranged from 9.2 to 93.4 µg g−1 dw. Concentrations of n-alkanes both in riverine sediments and in soil samples were lowest in the hyperarid zone and highest in the humid zone (Table 1). ACL varied along the aridity gradient (Table 1), ranging from 28.6 to 30.9; the highest ACL values were found in the hyperarid zone and the lowest in the humid zone (Table 1). The most prevalent n-alkane homologues were n-C31 and n-C29. In the hyperarid and arid zones, n-C31 was the most common, while in the semiarid and humid zones, n−C29 predominated (Tables 1 and S4).

3.1.2 Concentration and distribution of n-alkanes in marine sediments

All 29 marine sediments analyzed presented odd over even chain length predominance with a CPI between 2.3 and 9.4 (Table 1). The n-alkane concentration was lowest (0.1 µg g−1 dw) in sediments adjacent to the hyperarid zone and highest (3.5 µg g−1 dw) in sediments adjacent to the humid zone (Table 1). In the marine sediments, the chain length distribution of the n-alkanes varied with an ACL ranging from 29.3 to 30.8 (Table 1). The highest ACL values were found in sediments adjacent to the hyperarid zone (30.8), but no clear trend with latitude was apparent in the ACL values of the marine sediments. The most abundant n-alkane homologue in the marine surface sediments studied was n-C31, except for two samples in the hyperarid zone, where n-C29 concentration was higher (Tables 1, S4).

3.2 δ2Hwax values of river, soil, and marine sediments

3.2.1 δ2Hwax values in river sediments and soils

The δ2Hwax values of the n-C29 and n-C31 homologues varied from −90 ‰ to −185 ‰, and from −114 ‰ to −190 ‰ respectively (Table 1). The mean δ2Hwax values from n-C29 in the hyperarid and arid zones were found to be 8 ‰ higher than the mean values from n-C31, while in the humid zone, the mean δ2Hwax values from n-C29 were 1 ‰ lower compared to those from n-C31.

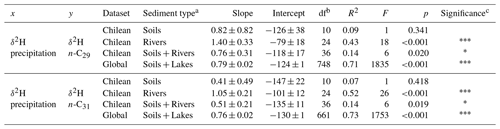

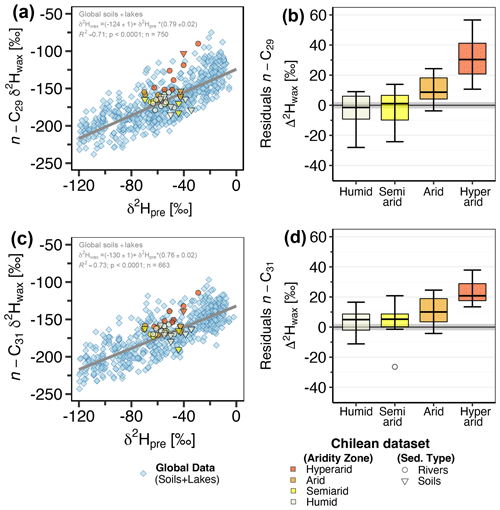

We examined the relationship between the measured δ2Hwax and δ2Hpre derived from the OIPC (Fig. 2a, c). We found that n-C29 and n-C31 δ2Hwax values from our Chilean river sediments show a positive correlation with δ2Hpre (δ2H n-C29: R2=0.43, p<0.001; n-C31: R2 = 0.52, p<0.001) (Table 2), while δ2Hwax from Chilean soils show no significant correlation with δ2Hpre (n-C29:R2=0.06, p=0.41; n-C31: R2=0.04, p=0.56) (Table 2). Analyzing river and soil δ2Hwax together vs. δ2Hpre we found a low value, yet still with a statistically significant correlation (n-C29: R2=0.14, p=0.02; n-C31: R2=0.14, p=0.02) (Table 2).

Table 2Statistical parameters of the linear regressions between δ2Hpre and δ2Hwax. The regressions obtained are of the type y = Intercept + Slope × x, df indicates the number of degrees of freedom from the fitted linear model and F is the F-statistic number.

a Sediment type refers to the sample set that was used for the regressions; enables comparison of the relationships on the different spatial scales. b df refers to degrees of freedom of the regression model, for this case it is the number of samples minus 2. c The number of asterisks indicates the significance of the regression. If a p value is greater than 0.05 there are no asterisks. If a p value is between 0.05 and 0.01, it is represented with one asterisk (*). If a p value is between 0.01 and 0.001, it is represented with two asterisks (). If a p value is less than 0.001, it is represented with three asterisks ().

For the global compiled dataset, combining the lakes and soils data, we found a strong significant correlation between δ2Hwax and δ2Hpre (n-C29: R2=0.71, p<0.001; n-C31: R2=0.73, p<0.001) (Table 2, Fig. 2a, c). Chilean δ2Hwax values from the humid, semiarid, and arid zones generally follow the linear relationship between δ2Hwax and δ2Hpre established by the global dataset (Fig. 2a, c), while δ2Hwax values from the hyperarid zone exhibit a noticeable departure from the global linear relationship between δ2Hwax and δ2Hpre (Fig. 2a, c).

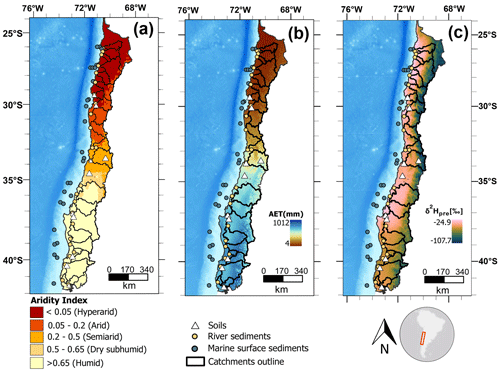

From our measured samples, we used δ2Hwax values from river and soil samples to calculate residuals, following the methodology described in Sect. 2.6.1. δ2Hwax value residuals, from n-C29 and n-C31, were highest in samples from the hyperarid zone (Fig. 2b, d and Table S5) and decreased with increasing humidity. n-C29 mean residual values ranged from 32 ‰ in the hyperarid zone to −3 ‰ in the humid zone, while n-C31 residuals varied from 23 ‰ in the hyperarid zone to 4 ‰ in the humid zone. Residuals from n-C29 and n-C31 for the humid, semiarid, and arid zones showed no significant differences (Kruskal–Wallis test, Sect. 2.6.2; n-C29: p=0.125; n-C31: p=0.545; Table 3). When residuals from the hyperarid zone were analyzed together with the residuals from the other zones, the Kruskal–Wallis test indicated the existence of a significant difference among them (n-C29: p<0.001; n-C31: p<0.002; Table 3).

Figure 2(a, c) δ2Hwax values from n-C29 and n-C31 homologues vs. δ2Hpre. Inverted triangles represent Chilean soil samples, circles represent Chilean river sediment samples. The blue diamonds represent δ2Hwax from a global compilation of previously published data from soils and lake surface sediments (Table S1). δ2Hpre data for both the Chilean locations and the global compilation dataset are derived from OIPC (Bowen and Revenaugh, 2003). The gray line in the plot illustrates the linear relationship between δ2Hwax and δ2Hpre for the global dataset, as indicated by the equation and regression parameters annotated within the plot. (b, d) Boxplots of the calculated residuals from the Chilean sediments (soils + river sediments) with respect to the global regression. The aridity zone classification follows the classification proposed by UNEP (1997).

3.2.2 δ2Hwax values in marine sediments

δ2Hwax values of n-C29 and n-C31 in marine sediments varied from −108 ‰ to −168 ‰, and from −105 ‰ to −172 ‰, respectively (Table 1). For both n-C29 and n-C31, δ2Hwax values were highest in marine sediments adjacent to the continental hyperarid zone and lowest in sediments adjacent to the continental humid zone. δ2Hwax values from n-C29 were on average 4 ‰ higher compared to values from n-C31 along the gradient (Table 1).

3.3 Apparent hydrogen isotope fractionation along the Chilean gradient

Apparent fractionation values () varied from −63 ‰ to −150 ‰, and from −88 ‰ to −153 ‰ for the n-C29 and n-C31 homologues, respectively (Table S6). Both soil and river sediments exhibited higher values in the hyperarid zone ( n-C ‰; n-C ‰). In general, values were increasingly negative with increasing humidity.

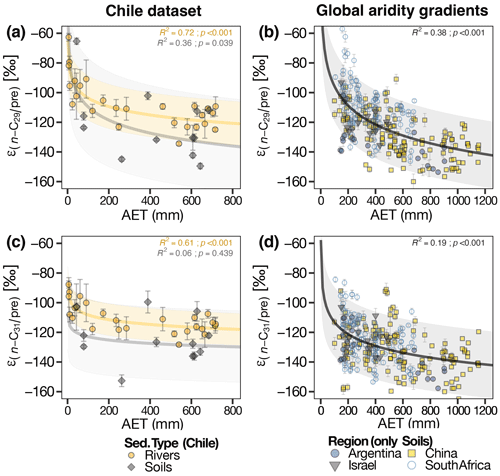

We found significant non-linear relationships between and water-climate parameters, i.e., AET, MAP, SM, RH, and aridity index (Table S7). AET showed the strongest correlation with (river sediments n-C29: R2=0.72, p<0.0001; river sediments n-C31: R2=0.61, p<0.0001) (Fig. 3, Table S7). Parameters associated solely with temperature (i.e., mean annual temperature, mean annual max daily temperature) showed no correlation with (Table S7). The values obtained from river samples were more strongly correlated with the climatic parameters than the values from soils (Table S7).

Figure 3 vs. AET (actual evapotranspiration). (a, c) Chilean soils and river sediments. Shaded gray area represents 95 % CI of the model fitted to the soil data, shaded yellow area represents 95 % CI of the model fitted to the river sediments. (b, d) Soils from aridity gradients of Argentina (Tuthorn et al., 2015), China (Rao et al., 2009; Li et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2020), Israel (Goldsmith et al., 2019), and South Africa (Herrmann et al., 2017; Strobel et al., 2020). Shaded gray area represents 95 % CI of the model fitted to the full dataset.

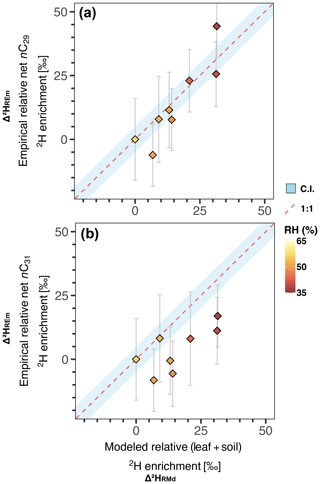

Figure 4Δ2HREm vs. Δ2HRMd for the catchments of the hyperarid zone. The dashed red line represents a 1:1 line; an analytical uncertainty range of 5 ‰ is used to represent the confidence interval (shaded blue area). Markers are color-coded by relative humidity (RH). (a) Results obtained for the n-C29 homologue. (b) Results obtained for the n-C31 homologue.

4.1 Causes of δ2Hwax variability in sediments and soils along the Chilean aridity gradient

4.1.1 Assessment of the OIPC δ2Hpre values along the aridity gradient

Analyzing the drivers of δ2Hwax values requires robust data on δ2Hpre. Since no long-term time series are available for the exact locations of our sampling sites, we rely on interpolated data generated by the OIPC (see above). Thus, a first factor to consider in our interpretations is the accuracy of the δ2Hpre values derived from the OIPC. The OIPC provides long-term estimates of modern (post-1950) mean δ2Hpre, at monthly and annual grids, which may differ from the δ2Hpre measured at a particular site on a short-term basis. The longer-term estimates from the OIPC are advantageous for our study, as soils and river sediments can integrate leaf waxes over spans of several decades to centuries (Huang et al., 1996; Douglas et al., 2014; Vonk et al., 2019). Consequently, we expect that δ2Hpre values from OIPC are the more relevant predictors for our δ2Hwax values. The OIPC model is based on data from GNIP stations (Bowen and Revenaugh, 2003), of which nine fall within continental Chile and can be used as a validation dataset. They range from the humid zone to the border between the arid and hyperarid zones and include a total of 923 monthly precipitation datapoints between 1964 and 2017 (Table S3). We find a significant linear relationship (R2=0.53, p<0.0001) between the δ2Hpre predicted by OIPC and measured δ2Hpre (Fig. S1a). Grouping by month and taking the long-term average of the measured δ2Hpre values, we found that the correlation is stronger (R2=0.80, p<0.0001) (Fig. S1b). Although there are uncertainties associated with the predicted OIPC δ2Hpre values, particularly in regions with sparse GNIP station coverage, the results presented above validate the use of OIPC δ2Hpre values across the studied aridity gradient in Chile.

4.1.2 δ2Hpre values control δ2Hwax values in the humid to arid zone

In the humid and semiarid zones of Chile δ2Hpre values are the main factor determining δ2Hwax values. Our results show that δ2Hwax values from soils and river sediments in the humid and semiarid zones of Chile generally follow the global linear relationship between δ2Hwax and δ2Hpre. This is confirmed through the residuals analysis (Fig. 2b, d) and is in accordance with the findings of previous studies in humid and semiarid regions (Feakins et al., 2016; Hou et al., 2008; Sachse et al., 2006; Tipple and Pagani, 2013; Tuthorn et al., 2015; Häggi et al., 2016; Bertassoli et al., 2022). Therefore, we suggest that δ2Hwax is primarily controlled by δ2Hpre in the humid and semiarid zones of Chile.

In the arid zone of Chile, δ2Hwax values show a slight deviation from the global regression between δ2Hwax and δ2Hpre (Fig. 2b, c). However, this deviation is not statistically significant when compared to the deviation of δ2Hwax values from the humid and semiarid zones of Chile (Table 3). As a result, the net or apparent fractionation between water source and lipid biomarker () is not significantly different in the arid zone when compared to humid and semiarid zones. Although previous studies have found that δ2Hwax values in arid zones are consistently higher due to changes in (Douglas et al., 2012; Feakins and Sessions, 2010; Polissar and Freeman, 2010), we cannot resolve a statistically significant difference between the arid zone, the humid zone, and semiarid zone (Fig. 2b, c, Table 3). This might be because earlier studies including arid zones focused on lakes draining small areas or exclusively analyzed soil and plant samples (Douglas et al., 2012; Feakins and Sessions, 2010; Polissar and Freeman, 2010; Schwab et al., 2015). Our study analyzed only two soil samples from the arid zone, which may not be a complete representation of the whole δ2Hwax variability. It is important to note that δ2Hwax values are significantly more variable in soils than in river sediments in all climate zones (as discussed in Sect. 4.4). Therefore, further sampling at smaller subcatchments or at the soil scale is necessary to confidently test whether δ2Hwax largely reflects δ2Hpre in the arid zone.

4.1.3 Controls on δ2Hwax variability in the hyperarid zone

δ2Hwax values in the hyperarid zone of Chile are influenced by additional factors beyond δ2Hpre values, as suggested by the Kruskal–Wallis test results (Table 3) and the deviation of δ2Hwax values from the global linear relationship between δ2Hwax and δ2Hpre (Fig. 2a, c). Along aridity gradients, climatic parameters such as evapotranspiration, RH, and aridity itself have been identified as key factors that exert control over values (Douglas et al., 2012; Polissar and Freeman, 2010; Schwab et al., 2015; Herrmann et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019). The mechanism behind this control is rooted in the impact that these climatic parameters have on soil water enrichment and leaf water enrichment (Gat, 1996; Smith and Freeman, 2006; Kahmen et al., 2013a). To determine the factors controlling along the Chilean aridity gradient, we conducted a regression analysis as outlined in Sect. 2.6.3. This analysis examined against three broad categories of climatic factors: temperature, water content, and water fluxes. Temperature was evaluated based on maximum daily temperature (MaxT) and mean annual temperature (MAT). Water content in the soil and atmosphere was evaluated through relative humidity (RH), soil moisture (SM), and aridity index (AIdx). Water fluxes were analyzed through actual/net evapotranspiration (AET) and mean annual precipitation (MAP). To further validate our findings, we used data from four previously published aridity gradients to determine if the observed trends are characteristic of strong aridity gradients globally, or simply a feature of the Chilean dataset. We selected four regions with the most pronounced aridity gradients in our compilation (Table S2), comprising data from soils from Argentina (Tuthorn et al., 2015), China (Rao et al., 2009; Li et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2020), Israel (Goldsmith et al., 2019), and South Africa (Herrmann et al., 2017; Strobel et al., 2020). To maintain the rigor of our analysis, we adopted a cautious approach and excluded publications that contained marked altitude gradients within the four selected regions, thereby eliminating the potentially confounding effect of elevation.

Our regression analysis indicates that no significant relationship exists between MAT or MaxT and (Table S7), which is consistent with mechanistic models of leaf water enrichment, which demonstrate a low sensitivity to variations in temperature (Farquhar and Gan, 2003; Kahmen et al., 2011; Rach et al., 2017). Furthermore, field studies in climatic transects along South Africa from Strobel et al. (2020) also found no significant correlation between temperature and . Similarly, along an aridity gradient in Argentina, Tuthorn et al. (2015) showed that RH exerts a greater control than temperature on the magnitude of 2H enrichment in leaf waxes. Thus, the narrow MAT range of 8–17 ∘C along our study area is expected to have minimal impact on leaf water enrichment and consequently on .

The significant correlations that we found between and variables linked to water content and water fluxes (Table S7) highlight the influence of hydrological conditions on values. Results from a principal component analysis (Fig. S2) demonstrate that hydrological variables are correlated, contributing to 69% of the total variance observed. This confirms the synchronized variation of these parameters, due to the hydrological cycle's water balance, and to some degree, their autocorrelation (Douglas et al., 2012). Similarly, all hydrological variables are strongly correlated with in our study, but AET exhibits the highest correlation (Fig. 3, Table S7). Hence, we suggest that in the hyperarid zone of Chile, δ2Hwax values are strongly controlled by evapotranspirative processes, in addition to δ2Hpre values.

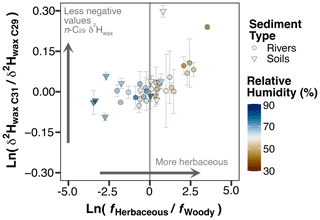

Figure 5Plot of log ratio between n-C31 δ2Hwax and n-C29 δ2Hwax vs. the log ratio between the fraction of herbaceous plants and fraction of woody plants. The fractions of herbaceous and woody vegetation were obtained following the methods described in Sect. 2.5.3. The vegetation cover is derived at the scale of the catchment area for river sediment samples and at the maximum resolution of the pixel (100 m × 100 m) for soil samples. Vegetation cover fraction data are from Buchhorn et al. (2020).

4.1.4 Soil and leaf water enrichment modeling in the hyperarid zone

We modeled the 2H enrichment in soil and leaf water of river samples in the hyperarid zone using Eqs. (9) and (20). By comparing the model results with the enrichment measured in our samples, while holding vegetation parameters constant, we can isolate the contribution of climatic factors to the changes in along the gradient. Equations (9) and (20) produce net soil (Δ2HSW) and net leaf water enrichment (Δ2HLWP) values, respectively, for each sample. To make the modeled Δ2HSW and Δ2HLWP values comparable with empirical values, we standardize the values of each catchment relative to the values obtained for the southernmost catchment of the hyperarid zone (Los Choros) (Table S8). From the standardization of the values we obtain an empirical relative net 2H enrichment for each catchment (Δ2HREm). The standardization of Δ2HSW and Δ2HLWP yields a relative Δ2HSW and a relative Δ2HLWP, the sum of which yields a modeled relative 2H enrichment for each catchment (Δ2HRMd) (Table S8). The progressive aridification trend toward the north offers an opportunity to evaluate the consistency between Δ2HREm and Δ2HRMd in response to aridity. Additionally, this approach eliminates the uncertainty surrounding the absolute value of biosynthetic fractionation, which would otherwise be a requirement for comparison of the Δ2HSW and Δ2HLWP against .

Our modeling approach was able to reproduce well the empirical enrichment measured in n-C29, but the enrichment measured in n-C31 was overestimated (Fig. 4a, b). Despite the high uncertainties propagated into the empirical relative enrichment values, the agreement between modeled and empirical values for n-C29 supports the hypothesis that evapotranspiration processes play a significant role in the fractionation of hydrogen isotopes in the hyperarid zone of Chile. Although for n-C31 most of the empirical enrichment is reproduced within uncertainty, there is a clear overestimation of the enrichment by the model (Fig. 4b). The model overestimation for n-C31 indicates that changes in climatic conditions alone do not account for all the variability in the magnitude of the enrichment. Some residual variability can be caused by vegetation effects that generate a differential enrichment in n-C29 and n-C31 among different plant types; this is further discussed in Sect. 4.2.

4.2 Aridity highlights δ2Hwax differences among n-C29 and n-C31 n-alkanes

In arid sites dominated by herbaceous vegetation, n-C29 consistently exhibited higher δ2Hwax values compared to n-C31 (Fig. 5, Table S6). This suggests a differential response of the homologues to evapotranspirative processes, which can be attributed to the plant sources from which they originate. Woody plants like trees and shrubs generally yield higher concentrations of n-C29 than n-C31, and herbaceous plants like grasses and forbs tend to produce higher concentrations of n-C31 than n-C29 (Kuhn et al., 2010; Zech et al., 2010; Duan and He, 2011; Howard et al., 2018; Bliedtner et al., 2018). Herbaceous plants possess different strategies to cope with aridity, including the development of smaller leaves and the use of CAM photosynthesis. Also, in desert ecosystems, herbaceous plants generally have greater rooting depths in comparison to woody plants like shrubs, which gives them access to water sources less enriched in 2H than surficial soil water (Ehleringer et al., 1991; Gibson, 1998; Gibbens and Lenz, 2001; Herrera, 2009; Feakins and Sessions, 2010; Kirschner et al., 2021). Additionally, greenhouse experiments have demonstrated that grasses use a mixture of enriched leaf water and less enriched soil water for biosynthesis (Kahmen et al., 2013a). Furthermore, plant physiology, biochemistry, or even the timing of leaf flush can have a significant impact on δ2Hwax (Bi et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2006; Smith and Freeman, 2006; Hou et al., 2007; Liu and Yang, 2008; Sachse et al., 2012; Tipple et al., 2013). Thus, it is possible that differences in δ2Hwax values of n-C31 and n-C29 homologues are the manifestation of distinct physiological and biochemical characteristics among different plant growth forms or particular plant species. In this study we focused on the level of plant growth forms due to the lack of plant species datasets at the scale of our study areas. However, it is important to note that within the same plant growth form, different plant species might exhibit distinct biosynthetic fractionation values and consequently affect δ2Hwax differently. The influence of both plant growth forms and plant species on sedimentary δ2Hwax over large scales is unclear, and more studies are needed to fully understand these relationships.

Notably, the differences in δ2Hwax values among homologues become significantly pronounced only under conditions of high aridity. These findings offer empirical evidence that disparities in δ2Hwax values between n-C31 and n-C29 homologues can potentially be utilized as a marker of specific vegetation and aridity conditions, such as the predominance of herbaceous plants under high aridity. Some studies noted and briefly discussed the divergence in δ2Hwax values from the n-C29 and n-C31 homologues (Garcin et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2022), but to our knowledge this has not been further analyzed. The results of this study suggest that differences between the homologues contain valuable information that could potentially be exploited as a proxy to indicate both aridity and the presence of herbaceous plants or possibly the presence of particular herbaceous species, but further research is needed to validate its application.

4.3 Non-linear relationship between and hydrological factors

The results of the regression analyses shown in Table S7 revealed that is non-linearly correlated with all the hydrological parameters studied. The values in Chilean soils exhibit non-linear correlations with hydrological factors. However, for Chilean soils, the only significant correlations between and climatic variables are with SM and AET, these correlations are observed only for the n-C29 homologue. This likely reflects the low sample density of soils in our study, particularly in the arid and hyperarid regions. For river samples as well as for the four selected aridity gradients, the results show that all regressions against hydrological factors are significant and non-linear (Table S7). These results indicate that the non-linear relationship between and hydrological factors can be found on strong aridity gradients globally and is not merely an artifact of our data.

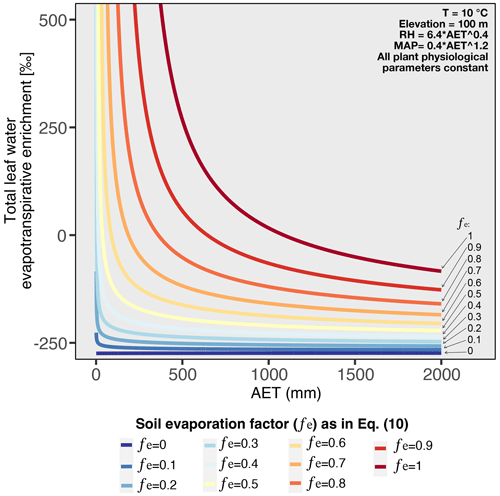

The non-linear relationship between enrichment and hydrological conditions can be modeled combining the leaf and soil water enrichment models explained in Sect. 2.6.4 of the methods. By parametrizing RH and MAP in terms of AET, Fig. 6 shows that the non-linear behavior can be reproduced when the model includes a component of soil evaporation (fe>0). These modeling results support our findings and strengthen the idea that under high aridity, the relationship between and hydrological conditions is non-linear. Previous studies showed that is controlled by hydrological conditions (Hou et al., 2018; Smith and Freeman, 2006; Feakins and Sessions, 2010; Sachse et al., 2012; Douglas et al., 2012; Herrmann et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2020), but most argue that the relationship between and the hydrological parameters is linear (Feakins and Sessions, 2010; Vogts et al., 2016; Herrmann et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019). By extensively including and analyzing samples from hyperarid regions, we demonstrate that behaves non-linearly along strong aridity gradients, as is also predicted by enrichment models incorporating both soil evaporation and leaf water transpiration (Fig. 6).

Figure 6Modeled total leaf water evapotranspirative enrichment under varying AET, considering different soil evaporation factors (fe). The fe values are used to derive the soil evaporated water from AET as expressed in Eq. (10). The total evapotranspirative leaf water enrichment is obtained summing the results of Eqs. (9) and (20). To obtain the results for this figure, RH and MAP were parameterized as a function of AET (see Figs. S3 and S4), as such all the variation in the evapotranspirative enrichment is only driven by variation of AET.

4.3.1 δ2Hwax differences between soils, riverine and marine sediments

Analyzing the Chilean dataset at the differential spatial scales, we found that δ2Hpre values showed better correlation with δ2Hwax values from river sediments than from soils (Table 2). In addition, soil δ2Hwax values showed weaker correlations with all climatic variables than river δ2Hwax values. This suggests a larger effect of spatial averaging of the δ2Hwax values for the river sediment samples, as they integrate both vegetation and climatic variability over larger regions than soil samples. In support of this, Goldsmith et al. (2019) showed a significant reduction of variability via the early incorporation of the leaf waxes into soils, finding that variability of from soils is significantly lower than variability of from plants. In a similar manner, lake sediments exhibit lower variability than both plants (Sachse et al., 2006) and soils (Douglas et al., 2012) in their source areas.

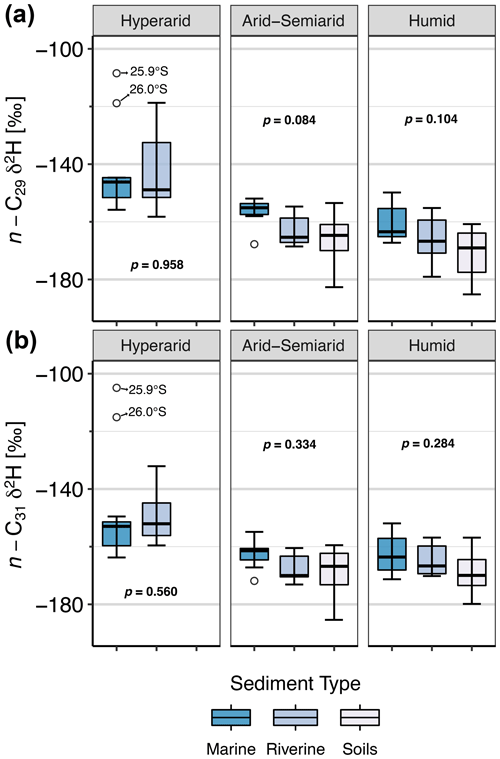

Figure 7Boxplots of δ2Hwax in soils, rivers, and marine surface sediments, among the different climate zones. (a) Data for the n-C29 homologue. (b) Data for the n-C31 homologue. Arid and semiarid zones were grouped to overcome sample size limitations. In the hyperarid zone, only one soil sample was taken and therefore no box is shown.

Overall, the ranges of δ2Hwax values from soils, rivers, and marine sediments overlap (Fig. 7), but there are two notable outliers in marine sediments of the hyperarid zone (Fig. 7). These samples were taken adjacent to the Pan de Azúcar catchment at 25.9∘ S (δ2H ‰) and at 26.0∘ S (δ2H ‰) and have similar δ2Hwax values as continental samples from locations further south: the Quebrada Puerto Flamenco at 26.5∘ S (δ2H ‰) and Quebrada Salitrosa at 26.1∘ S (δ2H ‰), which are catchments with predominantly herbaceous vegetation that span small areas close to the coastline. This suggests that these catchments could be a source of sediments to the identified outliers.

We conducted a Kruskal–Wallis test (Sect. 2.6.2) to assess the presence of significant differences in δ2Hwax values among the soils, rivers, and marine sediments from the different aridity zones. Together with the two marine outliers (above), nested catchments (Quebrada Salitrosa, Quebrada La Campana, and Estero Los Gringos) were excluded from the analysis, as the major catchments that include them would be expected to contribute the δ2Hwax values transported to the marine sediments.

We find no statistical differences between mean δ2Hwax values of the sediment types within each climate zone (Fig. 7). This suggests that climatic signals recorded by δ2Hwax are effectively transported along the sedimentary systems. In general, marine sediments show the smallest range of δ2Hwax values in any given region, in line with the decrease in variability that follows an increase in integration area and integration time. Marine sediments are expected to integrate over larger areas and longer timescales than river sediments, acquiring sediments not only from near fluvial sources but also by eolian input or coast-parallel currents (Gagosian and Peltzer, 1986; Poynter et al., 1989; Bernhardt et al., 2016). Overall, our findings support the notion of consistent transport of δ2Hwax values from the continent to the adjacent marine sediments within each climate zone.

In Fig. 7, δ2Hwax values from marine sediments generally display higher δ2Hwax values in marine sediments in comparison to soils and river sediments. Although the difference between δ2Hwax values among the sediment types is not statistically significant, higher δ2Hwax values in marine sediments might be attributed to differences in sourcing and transport of the continental sediments. However, given the limited sample set of paired marine and river sediments in the arid region and the absence of statistically significant differences in δ2Hwax values between the sediment types, we consider further discussion would be too speculative at this point.

4.4 Implications for paleoclimate studies

Our results demonstrate the potential of δ2Hwax as a proxy for δ2Hpre in the humid-to-arid zones of Chile. We found that δ2Hwax values in marine sediments are consistent with those in river sediments and soils from the adjacent continent, supporting the use of marine sedimentary δ2Hwax as a tracer of continental δ2Hpre. However, our analysis also revealed that hyperaridity can cause strong 2H enrichment (i.e., smaller values) and non-linear relationships between hydrological variables and . These findings suggest that δ2Hwax is highly sensitive to the onset of extreme aridity, while δ2Hwax values largely reflect δ2Hpre values in humid, semiarid, and arid settings. In hyperarid regions, the strong evapotranspirative effects on δ2Hwax could lead to an overestimation of δ2Hpre values, and consequently of hydrological changes, as also discussed by Hou et al. (2018). Because of this, it is crucial to consider the aridity states that an area may have experienced when using δ2Hwax as a paleoenvironmental proxy.

Furthermore, our analysis revealed differential responses of the n-C29 and n-C31 homologues under strong aridity conditions, likely due to different vegetation sources. We found that n-C29 is more sensitive to aridity and exhibits higher δ2Hwax values relative to n-C31 in sites with high aridity (Fig. 5). Similar findings have been reported in previous studies (Chen et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2013; Garcin et al., 2012). We found that the difference between δ2Hwax values in n-C29 and n-C31 is particularly pronounced in arid settings, especially where herbaceous vegetation dominates. This differential sensitivity could be useful in detecting the onset of high aridity, and thus could help avoid overestimation of hydrological changes. However, such an application requires additional information about the n-alkanes of the vegetation from the source areas.

In summary, along the Chilean humid-to-arid zones, our results support the use of δ2Hwax as a proxy for δ2Hpre and to study changes in paleohydrological conditions. However, with the onset of hyperaridity, δ2Hwax values can become decoupled from δ2Hpre and be controlled by evapotranspirative processes.

By analyzing soils, river sediments, and their marine counterparts along a strong aridity gradient in Chile, we tested the robustness with which the hydrogen isotope composition of leaf waxes (δ2Hwax) in soils and river sediments reflects modern climate conditions, and how accurately marine sediments preserve continental δ2Hwax values. We corroborate previous findings that in humid-to-arid zones, δ2Hwax values are largely controlled by δ2Hpre. However, in hyperarid zones, δ2Hwax values are additionally influenced by evapotranspirative enrichment, resulting in a non-linear relationship of δ2Hwax with hydrological variables. Using established models, we show that changes in RH, MAP and AET can explain most of the 2H enrichment for the n-C29 homologue. The n-C31 homologue is less sensitive to changes in hydrological conditions, suggesting that the δ2Hwax differences between the homologues reflect differences in leaf wax sources and their differential use of enriched leaf water and unenriched xylem water, as herbaceous vegetation is dominant under arid conditions. Further, the non-linearity that we found is particularly relevant in hyperarid zones, where small variations in hydrological parameters translate into large changes in δ2Hwax values. In paleoclimate studies, care must hence be taken when interpreting records in arid-to-hyperarid regions as records of δ2Hpre alone, since changes in δ2Hwax can become decoupled from changes in δ2Hpre and are rather driven by AET. The marine core-top samples that we analyzed reflect faithfully the continental δ2Hwax values from river sediments and soils along the entire aridity gradient, showing a land–ocean connectivity and preservation of terrestrial signals in the marine realm, even under the different hydrological regimes along the Chilean coast.

All Supplement Tables (S1–S9) and Figures (S1–S5) are available in the data publication Gaviria-Lugo et al. (2023): http://doi.org/10.5880/GFZ.3.3.2023.001. The data publication is hosted by the GFZ data services.

The metadata of all the IGSN-registered samples used for this study (samples in Table 1) can be accessed via http://igsn.org/ (plus according IGSN number).

NGL: Conceptualized the research, collected, and prepared samples, compiled and analyzed data, prepared the original manuscript draft. CL: Conceptualized the research, collected samples, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. HW: Acquired funding, conceptualized the research, collected samples, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. AB: Acquired funding, conceptualized the research, collected samples, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. PF: Conceptualized the research, collected samples, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. MM: Provided marine sediment samples, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. OR: Assisted and supervised the lab work, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. DS: Supervised and conceptualized the research, acquired funding, collected samples, reviewed, and edited the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

This article is part of the special issue “Earth surface shaping by biota (Esurf/BG/SOIL/ESD/ESSD inter-journal SI)”. It is not associated with a conference.

We acknowledge support from the German Science Foundation (DFG) priority program SPP-1803 “EarthShape: Earth Surface Shaping by Biota”. We are grateful to the Chilean National Park Service (CONAF) for providing access to the sample locations (Pan de Azúcar, La Campana and Nahuelbuta) and on-site support of our research. We thank Friedhelm von Blanckenburg and Todd Ehlers for initiating and leading the SPP Earthshape. We also acknowledge all the support from Esteban Rodríguez Sepúlveda during our field work campaign in Chile. We thank Kirstin Übernickel and Leandro Paulino for their support in the coordination of the EarthShape program. The marine sample material was stored and supplied by the GeoB Core Repository at the MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen, Germany. We would like to thank the two anonymous referees for their valuable comments and contributions, which have improved the quality of this paper.

This research has been supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant nos. WI 3874/7-1, BE 5070/6-1, and SA 1889/3-1).

The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by the Helmholtz Centre Potsdam – GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences.

This paper was edited by Todd A. Ehlers and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Abatzoglou, J. T., Dobrowski, S. Z., Parks, S. A., and Hegewisch, K. C.: TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015, Sci. Data, 5, 170191, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.191, 2018.

Aitchison, J.: The Statistical Analysis of Compositional Data, J. Roy. Stat. Soc. Ser. B, 44, 139–177, 1982.

Aitchison, J.: The statistical analysis of compositional data, Chapman and Hall, 416 pp., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-4109-0, 1986.

Bernhardt, A., Hebbeln, D., Regenberg, M., Lückge, A., and Strecker, M. R.: Shelfal sediment transport by an undercurrent forces turbidity-current activity during high sea level along the Chile continental margin, Geology, 44, 295–298, 2016.

Bertassoli, D. J., Häggi, C., Chiessi, C. M., Schefuß, E., Hefter, J., Akabane, T. K., and Sawakuchi, A. O.: Controls on the distributions of GDGTs and n-alkane isotopic compositions in sediments of the Amazon River Basin, Chem. Geol., 594, 120777, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2022.120777, 2022.

Bi, X., Sheng, G., Liu, X., Li, C., and Fu, J.: Molecular and carbon and hydrogen isotopic composition of n-alkanes in plant leaf waxes, Org. Geochem., 36, 1405–1417, 2005.

Bliedtner, M., Schäfer, I. K., Zech, R., and von Suchodoletz, H.: Leaf wax n-alkanes in modern plants and topsoils from eastern Georgia (Caucasus) – implications for reconstructing regional paleovegetation, Biogeosciences, 15, 3927–3936, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-3927-2018, 2018.

Bowen, G. J. and Revenaugh, J.: Interpolating the isotopic composition of modern meteoric precipitation, Water Resour. Res., 39, 1299, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003WR002086, 2003.

Bowen, G. J., Cai, Z., Fiorella, R. P., and Putman, A. L.: Isotopes in the Water Cycle: Regional- to Global-Scale Patterns and Applications, Annu. Rev. Earth Pl. Sc., 47, 453–479, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-053018-060220, 2019.

Buchhorn, M., Lesiv, M., Tsendbazar, N.-E., Herold, M., Bertels, L., and Smets, B.: Copernicus global land cover layers—collection 2, Remote Sens., 12, 1044, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12061044, 2020.

Cernusak, L. A., Barbour, M. M., Arndt, S. K., Cheesman, A. W., English, N. B., Feild, T. S., Helliker, B. R., Holloway-Phillips, M. M., Holtum, J. A. M., Kahmen, A., McInerney, F. A., Munksgaard, N. C., Simonin, K. A., Song, X., Stuart-Williams, H., West, J. B., and Farquhar, G. D.: Stable isotopes in leaf water of terrestrial plants: Stable isotopes in leaf water, Plant Cell Environ., 39, 1087–1102, https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.12703, 2016.

Chen, G., Li, X., Tang, X., Qin, W., Liu, H., Zech, M., and Auerswald, K.: Variability in pattern and hydrogen isotope composition (δ2H) of long-chain n-alkanes of surface soils and its relations to climate and vegetation characteristics: A meta-analysis, Pedosphere, 32, 369–380, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0160(21)60080-2, 2022.

Chikaraishi, Y., Naraoka, H., and Poulson, S. R.: Hydrogen and carbon isotopic fractionations of lipid biosynthesis among terrestrial (C3, C4 and CAM) and aquatic plants, Phytochemistry, 65, 1369–1381, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.03.036, 2004.

Collins, J. A., Prange, M., Caley, T., Gimeno, L., Beckmann, B., Mulitza, S., Skonieczny, C., Roche, D., and Schefuß, E.: Rapid termination of the African Humid Period triggered by northern high-latitude cooling, Nat. Commun., 8, 1372, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01454-y, 2017.

Craig, H.: Isotopic Variations in Meteoric Waters, Science, 133, 1702–1703, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.133.3465.1702, 1961.

Dansgaard, W.: Stable isotopes in precipitation, Tellus, 16, 436–468, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2153-3490.1964.tb00181.x, 1964.

Dansgaard, W., Johnsen, S. J., Clausen, H. B., Dahl-Jensen, D., Gundestrup, N. S., Hammer, C. U., Hvidberg, C. S., Steffensen, J. P., Sveinbjörnsdottir, A. E., Jouzel, J., and Bond, G.: Evidence for general instability of past climate from a 250-kyr ice-core record, Nature, 364, 218–220, https://doi.org/10.1038/364218a0, 1993.

Dawson, T. E., Mambelli, S., Plamboeck, A. H., Templer, P. H., and Tu, K. P.: Stable Isotopes in Plant Ecology, Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst., 33, 507–559, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.020602.095451, 2002.

Douglas, P. M. J., Pagani, M., Brenner, M., Hodell, D. A., and Curtis, J. H.: Aridity and vegetation composition are important determinants of leaf-wax δD values in southeastern Mexico and Central America, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 97, 24–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2012.09.005, 2012.

Douglas, P. M., Pagani, M., Eglinton, T. I., Brenner, M., Hodell, D. A., Curtis, J. H., Ma, K. F., and Breckenridge, A.: Pre-aged plant waxes in tropical lake sediments and their influence on the chronology of molecular paleoclimate proxy records, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 141, 346–364, 2014.

Duan, Y. and He, J.: Distribution and isotopic composition of n-alkanes from grass, reed and tree leaves along a latitudinal gradient in China, Geochem. J., 45, 199–207, https://doi.org/10.2343/geochemj.1.0115, 2011.

Eglinton, T. I. and Eglinton, G.: Molecular proxies for paleoclimatology, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 275, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2008.07.012, 2008.

Ehleringer, J. R., Phillips, S. L., Schuster, W. S. F., and Sandquist, D. R.: Differential utilization of summer rains by desert plants, Oecologia, 88, 430–434, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00317589, 1991.

Epstein, S., Thompson, P., and Yapp, C. J.: Oxygen and Hydrogen Isotopic Ratios in Plant Cellulose, Science, 198, 1209–1215, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.198.4323.1209, 1977.

Fahrland, E., Jacob, P., Schrader, H., and Kahabka, H.: Copernicus DEM Product Handbook, Copernicus, https://doi.org/10.5270/esa-c5d3d65, 2020.

Farquhar, G. and Gan, K. S.: On the progressive enrichment of the oxygen isotopic composition of water along a leaf, Plant Cell Environ., 26, 801–819, 2003.

Farquhar, G. D., Cernusak, L. A., and Barnes, B.: Heavy Water Fractionation during Transpiration, Plant Physiol., 143, 11–18, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.106.093278, 2007.

Feakins, S. J. and Sessions, A. L.: Controls on the ratios of plant leaf waxes in an arid ecosystem, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 74, 2128–2141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2010.01.016, 2010.

Feakins, S. J., Bentley, L. P., Salinas, N., Shenkin, A., Blonder, B., Goldsmith, G. R., Ponton, C., Arvin, L. J., Wu, M. S., Peters, T., West, A. J., Martin, R. E., Enquist, B. J., Asner, G. P., and Malhi, Y.: Plant leaf wax biomarkers capture gradients in hydrogen isotopes of precipitation from the Andes and Amazon, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 182, 155–172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2016.03.018, 2016.

Fick, S. E. and Hijmans, R. J.: WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas, Int. J. Climatol., 37, 4302–4315, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5086, 2017.

Francey, R. J. and Farquhar, G. D.: An explanation of 13C 12C variations in tree rings, Nature, 297, 28–31, https://doi.org/10.1038/297028a0, 1982.

Gagosian, R. B. and Peltzer, E. T.: The importance of atmospheric input of terrestrial organic material to deep sea sediments, Org. Geochem., 10, 661–669, 1986.

Gao, L., Edwards, E. J., Zeng, Y., and Huang, Y.: Major evolutionary trends in hydrogen isotope fractionation of vascular plant leaf waxes, PloS one, 9, e112610, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112610, 2014.

Garcin, Y., Schwab, V. F., Gleixner, G., Kahmen, A., Todou, G., Séné, O., Onana, J.-M., Achoundong, G., and Sachse, D.: Hydrogen isotope ratios of lacustrine sedimentary n-alkanes as proxies of tropical African hydrology: Insights from a calibration transect across Cameroon, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 79, 106–126, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2011.11.039, 2012.

Gat, J. R.: Stable isotopes of fresh and saline lakes, in: Physics and Chemistry of Lakes, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 139–165, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-85132-2_5, 1995.

Gat, J. R.: Oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in the hydrologic cycle, Annu. Rev. Earth Pl. Sc., 24, 225–262, 1996.

Gaviria-Lugo, N., Läuchli, C., Wittmann, H., Bernhard, A., Frings, P., Mohtadi, M., Rach, O., and Sachse, D.: Data of leaf wax hydrogen isotope ratios and climatic variables along an aridity gradient in Chile and globally, GFZ Data Services [data set], https://doi.org/10.5880/GFZ.3.3.2023.001, 2023.

Gibbens, R. P. and Lenz, J. M.: Root systems of some Chihuahuan Desert plants, J. Arid Environ., 49, 221–263, 2001.

Gibson, A. C.: Photosynthetic organs of desert plants, Bioscience, 48, 911–920, 1998.

Goldsmith, Y., Polissar, P. J., deMenocal, P. B., and Broecker, W. S.: Leaf Wax δD and δ13C in Soils Record Hydrological and Environmental Information Across a Climatic Gradient in Israel, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 124, 2898–2916, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JG005149, 2019.

Griepentrog, M., De Wispelaere, L., Bauters, M., Bodé, S., Hemp, A., Verschuren, D., and Boeckx, P.: Influence of plant growth form, habitat and season on leaf-wax n-alkane hydrogen-isotopic signatures in equatorial East Africa, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 263, 122–139, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2019.08.004, 2019.

Häggi, C., Sawakuchi, A. O., Chiessi, C. M., Mulitza, S., Mollenhauer, G., Sawakuchi, H. O., Baker, P. A., Zabel, M., and Schefuß, E.: Origin, transport and deposition of leaf-wax biomarkers in the Amazon Basin and the adjacent Atlantic, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 192, 149–165, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2016.07.002, 2016.

Hebbeln, D.: Cruise Report of R/V Sonne Cruise 102 Valparaiso – Valparaiso, 9 May–28 June 1995, 1995.

Hebbeln, D.: PUCK: Report and preliminary results of R/V Sonne Cruise SO156, Valparaiso (Chile) – Talcahuano (Chile), 29 March–14 May 2001, 2001.

Herrera, A.: Crassulacean acid metabolism and fitness under water deficit stress: if not for carbon gain, what is facultative CAM good for?, Ann. Bot., 103, 645–653, 2009.

Herrmann, N., Boom, A., Carr, A. S., Chase, B. M., West, A. G., Zabel, M., and Schefuß, E.: Hydrogen isotope fractionation of leaf wax n-alkanes in southern African soils, Org. Geochem., 109, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2017.03.008, 2017.

Hoffmann, G., Ramirez, E., Taupin, J. D., Francou, B., Ribstein, P., Delmas, R., Dürr, H., Gallaire, R., Simões, J., Schotterer, U., Stievenard, M., and Werner, M.: Coherent isotope history of Andean ice cores over the last century, Geophys. Res. Lett., 30, 1179, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL014870, 2003.

Horita, J. and Wesolowski, D. J.: Liquid-vapor fractionation of oxygen and hydrogen isotopes of water from the freezing to the critical temperature, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 58, 3425–3437, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(94)90096-5, 1994.

Hou, J., D'Andrea, W. J., MacDonald, D., and Huang, Y.: Hydrogen isotopic variability in leaf waxes among terrestrial and aquatic plants around Blood Pond, Massachusetts (USA), Org. Geochem., 38, 977–984, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2006.12.009, 2007.

Hou, J., D'Andrea, W. J., and Huang, Y.: Can sedimentary leaf waxes record D/H ratios of continental precipitation? Field, model, and experimental assessments, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 72, 3503–3517, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2008.04.030, 2008.

Hou, J., Tian, Q., and Wang, M.: Variable apparent hydrogen isotopic fractionation between sedimentary n-alkanes and precipitation on the Tibetan Plateau, Org. Geochem., 122, 78–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2018.05.011, 2018.

Howard, S., McInerney, F., Caddy-Retalic, S., Hall, P., and Andrae, J.: Modelling leaf wax n-alkane inputs to soils along a latitudinal transect across Australia, Org. Geochem., 121, 126–137, 2018.

Huang, Y., Bol, R., Harkness, D. D., Ineson, P., and Eglinton, G.: Post-glacial variations in distributions, 13C and 14C contents of aliphatic hydrocarbons and bulk organic matter in three types of British acid upland soils, Org. Geochem., 24, 273–287, 1996.

IAEA/WMO: Global Network of Isotopes in Precipitation, The GNIP Database: https://nucleus.iaea.org/wiser, last access: 25 January 2023.

Jacob, H. and Sonntag, C.: An 8-year record of the seasonal variation of 2H and 18O in atmospheric water vapour and precipitation at Heidelberg, Germany, Tellus B, 43, 291–300, https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0889.1991.t01-2-00003.x, 1991.

Kahmen, A., Sachse, D., Arndt, S. K., Tu, K. P., Farrington, H., Vitousek, P. M., and Dawson, T. E.: Cellulose δ18O is an index of leaf-to-air vapor pressure difference (VPD) in tropical plants, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 1981–1986, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1018906108, 2011.

Kahmen, A., Schefuß, E., and Sachse, D.: Leaf water deuterium enrichment shapes leaf wax n-alkane δD values of angiosperm plants I: Experimental evidence and mechanistic insights, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 111, 39–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2012.09.003, 2013a.

Kahmen, A., Hoffmann, B., Schefuß, E., Arndt, S. K., Cernusak, L. A., West, J. B., and Sachse, D.: Leaf water deuterium enrichment shapes leaf wax n-alkane δD values of angiosperm plants II: Observational evidence and global implications, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 111, 50–63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2012.09.004, 2013b.

Kirschner, G. K., Xiao, T. T., and Blilou, I.: Rooting in the desert: A developmental overview on desert plants, Genes, 12, 709, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12050709, 2021.

Kruskal, W. H. and Wallis, W. A.: Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis, J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 47, 583–621, 1952.

Kuhn, T. K., Krull, E. S., Bowater, A., Grice, K., and Gleixner, G.: The occurrence of short chain n-alkanes with an even over odd predominance in higher plants and soils, Org. Geochem., 41, 88–95, 2010.

Kurita, N., Ichiyanagi, K., Matsumoto, J., Yamanaka, M. D., and Ohata, T.: The relationship between the isotopic content of precipitation and the precipitation amount in tropical regions, J. Geochem. Expl., 102, 113–122, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gexplo.2009.03.002, 2009.

Ladd, S. N., Maloney, A. E., Nelson, D. B., Prebble, M., Camperio, G., Sear, D. A., Hassall, J. D., Langdon, P. G., Sachs, J. P., and Dubois, N.: Leaf wax hydrogen isotopes as a hydroclimate proxy in the tropical Pacific, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 126, e2020JG005891, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020jg005891, 2021.

Lawrence, D. M., Thornton, P. E., Oleson, K. W., and Bonan, G. B.: The partitioning of evapotranspiration into transpiration, soil evaporation, and canopy evaporation in a GCM: Impacts on land–atmosphere interaction, J. Hydrometeorol., 8, 862–880, 2007.

Lehmann, P., Berli, M., Koonce, J. E., and Or, D.: Surface evaporation in arid regions: Insights from lysimeter decadal record and global application of a surface evaporation capacitor (SEC) model, Geophys. Res. Lett., 46, 9648–9657, 2019.

Leider, A., Hinrichs, K.-U., Schefuß, E., and Versteegh, G. J. M.: Distribution and stable isotopes of plant wax derived n-alkanes in lacustrine, fluvial and marine surface sediments along an Eastern Italian transect and their potential to reconstruct the hydrological cycle, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 117, 16–32, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2013.04.018, 2013.

Li, Y., Yang, S., Luo, P., and Xiong, S.: Aridity-controlled hydrogen isotope fractionation between soil n-alkanes and precipitation in China, Org. Geochem., 133, 53–64, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2019.04.009, 2019.

Lisiecki, L. E. and Raymo, M. E.: A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records, Paleoceanography, 20, PA1003, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004pa001071, 2005.

Liu, J., Liu, W., An, Z., and Yang, H.: Different hydrogen isotope fractionations during lipid formation in higher plants: Implications for paleohydrology reconstruction at a global scale, Sci. Rep., 6, 19711, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19711, 2016.

Liu, W. and Yang, H.: Multiple controls for the variability of hydrogen isotopic compositions in higher plant n-alkanes from modern ecosystems, Glob. Change Biol., 14, 2166–2177, 2008.