the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Effects of surface water interactions with karst groundwater on microbial biomass, metabolism, and production

Adrian Barry-Sosa

Madison K. Flint

Justin C. Ellena

Jonathan B. Martin

Brent C. Christner

Unearthing the effects of surface water and groundwater interactions on subsurface biogeochemical reactions is crucial for developing a more mechanistic understanding of carbon and energy flow in aquifer ecosystems. To examine physiological characteristics across groundwater microbial communities that experience varying degrees of interaction with surface waters, we investigated 10 springs and a river sink and rise system in north central Florida that discharge from and/or mix with the karstic upper Floridan aquifer (UFA). Groundwater with longer residence times in the aquifer had lower concentrations of dissolved oxygen, dissolved and particulate organic carbon, and microbial biomass, as well as the lowest rates of respiration (0.102 to 0.189 ) and heterotrophic production (198 to 576 ). Despite these features, oligotrophic UFA groundwater (< 0.5 mg C L−1) contained bioavailable organic matter that supported doubling times (14 to 62 h) and cell-specific production rates (0.0485 to 0.261 pmol C per cell per hour) comparable to those observed for surface waters (17 to 20 h; 0.105 to 0.124 pmol C per cell per hour). The relatively high specific rates of dissimilatory and assimilatory metabolism indicate a subsurface source of labile carbon to the groundwater (e.g., secondary production and/or chemoautotrophy). Our results link variations in UFA hydrobiogeochemistry to the physiology of its groundwater communities, providing a basis to develop new hypotheses related to microbial carbon cycling, trophic hierarchy, and processes generating bioavailable organic matter in karstic aquifer ecosystems.

- Article

(2550 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1152 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Groundwater is a vital natural resource that sustains aquatic ecosystems and provides approximately half of the water used globally for agriculture and human consumption (Jasechko and Perrone, 2021). Information on microbial biogeochemical reactions that affect organic matter degradation, nutrient cycling, and the transformation of contaminants in aquifers is therefore highly relevant for understanding the processes contributing to groundwater quality. Moreover, knowledge of groundwater food webs is necessary for enabling meaningful assessments of their resilience to human impacts and environmental change. Aquifers vary in lithology and characteristics such as permeability, depth, and water storage capacity. Karst terrain covers ∼ 15 % of Earth's ice-free land surface (Goldscheider et al., 2020) and represents the largest reservoir of carbon on the Earth with potential impacts on the carbon and climate cycle (Martin, 2017). In the case of karst aquifers, the dissolution of the underlying carbonate rock creates preferential flow paths for groundwater in the subsurface. More specifically, the solubility of karstic rocks creates heterogenous subsurface environments with a range of permeabilities that can be described via a triple porosity model (i.e., rock's primary porosity, fractures, and conduits from a few centimeters to tens of meters in diameter; Worthington et al., 2000). Because the hydrogeological features of karst aquifers provide opportunities for rapid and direct exchange between surface waters and groundwater, they are extremely vulnerable to surface contaminants (e.g., Kalhor et al., 2019).

Studies of karstic aquifers from around the world have shown their groundwaters to be generally oligotrophic (< 0.5 mg C L−1) and contain low standing stocks of microbial cells and biomass (Farnleitner et al., 2005; Wilhartitz et al., 2009, 2013; Hershey et al., 2018; Hershey and Barton, 2018; Malki et al., 2020, 2021). While these properties imply energy- and growth-limited conditions, new observations from karst aquifers are needed to decipher the biogeochemical contributions and rates of carbon metabolism by microbes in their groundwaters. Supplies of organic matter for subsurface microbial activity include photosynthetically derived material originating from the surface (e.g., Jin et al., 2014) and in situ production via chemosynthesis. The current paradigm for karstic aquifers is that biogeochemical reactions are chiefly driven by the oxidation of surface-derived organic matter (Hershey and Barton, 2018). Based on this assumption, rates of carbon cycling and microbial growth should depend on the nature of the organic matter pool, presence of suitable electron acceptors, and residence time of groundwater. Though secondary production (i.e., heterotrophic production of biomass) may be the dominant component of subsurface carbon and energy flow, the data available to assess rates of organic carbon recycling and heterotrophic growth in karst aquifer ecosystems are sparse. Remarkably, studies that have compared the chemistry of organic matter in surface water to groundwater have shown higher hydrogen to carbon ratios that indicate the groundwater contains more labile forms of organic carbon (McDonough et al., 2022). Sources of labile carbon to karstic groundwater remain poorly characterized; however, recent estimates of global dark primary production in carbonate aquifer ecosystems (0.11 Pg C yr−1; Overholt et al., 2022) suggest chemoautotrophy may have a larger contribution than previously thought.

The upper Floridan aquifer (UFA) is one of the largest and most hydrologically productive karstic aquifers in the world, with an area of ∼ 260 000 km2 and depth of up to 500 m below the surface (Miller, 1986, 1997; Williams and Kuniansky, 2016). Most of the UFA is confined by the Hawthorn Group, which consists of siliciclastic sands and clays interbedded with thin carbonate units (Scott, 1988). At the erosional edge of the Hawthorn Group in northwest Florida, the confining unit has been eroded, promoting extensive surface-water–groundwater exchange. The presence of numerous hydrological springs throughout this region provides direct access to groundwater that has had varying degrees of interaction with surface water and an experimentally tractable system to investigate the effects of hydrogeochemistry on microbial biomass and metabolism. Previous work has shown that groundwater residence time is inversely proportional to concentrations of dissolved oxygen (DO) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC; Martin and Gordon, 2000; Martin et al., 2016; Oberhelman et al., 2024); however, the effects of hydrogeochemistry on microbial physiology and production in the groundwater are not known. Importantly, interactions with surface waters that increase groundwater DO and DOC concentrations can shift groundwater redox state and pH, which in turn alter biogeochemical reactions in the aquifer (Brown et al., 2014). For instance, the microbial production of the greenhouse gases nitrous oxide (Flint et al., 2021, 2023) and methane (Oberhelman et al., 2023) is known to be enhanced by surface water mixing into phreatic cave systems of the UFA.

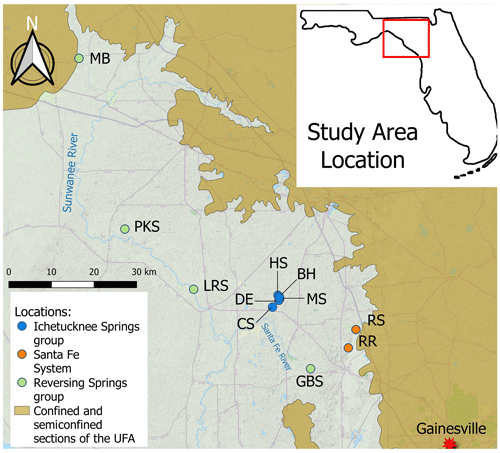

Figure 1Locator map of the sites sampled in this study. MB: Madison Blue Spring; PKS: Peacock Springs; LRS: Little River Spring; DE: Devil's Eye Spring; HS: Head Spring; BH: Blue Hole Spring; MS: Mission Spring; CS: Coffee Spring; GBS: Gilchrist Blue Springs; RS: Santa Fe River Sink; RR: Santa Fe River Rise. The figure was generated using QGIS with base map data from ©OpenStreetMap contributors 2021. Distributed under the Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL) v1.0.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that groundwater residence time and the availability and quality (i.e., composition, chemical structure, and nutrient content) of organic matter correlate with microbial biomass, metabolism, and production. This concept was examined by studying 10 locations (Fig. 1) that discharge groundwater with differing organic matter characteristics and estimated residence times ranging from ∼ 18 h to ∼ 40 years (Martin and Dean, 1999; Martin et al., 2016). The effects of mixing with surface waterbodies were studied by sampling water from springs that reverse flow under flood stage conditions (Gulley et al., 2011) as well as the Santa Fe River before and after it emerges from the subsurface after conduit flow and interaction with groundwater (Moore et al., 2009). Our results provide new insight into microbial carbon flow and partitioning over an energy gradient ranging from nutrient-rich surface waters to oligotrophic groundwaters that had been stored in the UFA for decades.

2.1 Site description

Water from 10 springs and a river sink–rise system (O'Leno State Park) in north central Florida (Fig. 1) was sampled between December 2018 and December 2022 (Table S1 in the Supplement). Based on the geochemical properties of the groundwater discharged from the springs and extent of interaction with surface waters, the sites investigated can be classified into three groups (Flint et al., 2021): (1) the Ichetucknee spring group, which includes Blue Hole Spring, Head Spring, Mission Spring, Coffee Spring, and Devil's Eye Spring; (2) the reversing spring group, which includes Madison Blue Spring, Peacock Springs, Little River Spring, and Gilchrist Blue Springs; and (3) the Santa Fe River sink–rise system, where River Sink and River Rise are located (Fig. 1). The river sink–rise system is a swallet or opening where the Santa Fe River directly recharges water-filled caves and that is discharged to the surface ∼ 6 km downstream. Blue Hole Spring, Madison Blue Spring, and River Rise are first-magnitude springs (discharge > 2.8 m3 s−1); Gilchrist Blue Springs (vents 1 and 2), Little River Spring, Head Spring, and Devil's Eye Spring are second magnitude (discharge 2.8–0.28 m3 s−1); and Peacock Springs, Mission Spring, and Coffee Spring are third magnitude (discharge < 0.28 m3 s−1).

Springs of the Ichetucknee spring group (blue symbols in Fig. 1) show low temporal geochemical variability, are located far from the point recharge of sinking streams, and have a low degree of mixing with surface waters (Martin et al., 2016; Henson et al., 2017). The Ichetucknee spring group is comprised of two subgroups, with groundwater from springs in subgroup I (Head Spring, Blue Hole Spring, and Coffee Spring) having shorter apparent ages (∼ 30 years) and higher average dissolved oxygen (DO; ∼ 3 mg L−1) in comparison to springs in subgroup II (Mission Spring and Devil's Eye Spring), which have apparent ages of ∼ 40 years and average DO concentrations of ∼ 0.5 mg L−1 (Martin and Gordon, 2000; Martin et al., 2016). The Ichetucknee spring group discharge water draining a 960 km2 springshed (Katz et al., 2009), approximately half of this area is located within the unconfined portion of the UFA, and the watershed is dominated by diffusive recharge with minimal point recharge. Approximately half of the landscape in the Ichetucknee springshed is forested, and about one-quarter is used for agriculture (Katz et al., 2009).

When water levels of the spring vents in the reversing spring group (Peacock Springs, Madison Blue Spring, Little River Spring, and Gilchrist Blue Springs; green symbols in Fig. 1) are higher than those of the receiving water, these springs discharge clear, fresh groundwater to spring runs. However, increases in the river stage during periods of high discharge may raise surface water elevations above groundwater heads, causing a reversal of spring flow direction that injects DO- and DOC-rich surficial waters into subsurface conduits hydraulically connected to the spring vent (Gulley et al., 2011). At Madison Blue Spring, the river water intrusions have been documented at distances of at least 1 km from the vent (Brown et al., 2014). Depending on rainfall and the spring's physiographic characteristics, the frequency of reversals for a given spring can vary from a few times a year to once every few years, and the effects of reversals on groundwater chemistry have been shown to persist for a period of at least 1 month (Brown et al., 2014, 2019; Oberhelman et al., 2023, 2024).

In the Santa Fe sink and rise system (orange symbols in Fig. 1), the Santa Fe River flows over a confined portion of the UFA to a region that is unconfined; this boundary is a topographic feature known as the Cody Scarp (Puri and Vernon, 1964). At River Sink, river water enters a sinkhole, flows underground for approximately 6 km through anastomosing water filled caves (herein called conduits) that have been partially mapped by cave divers, and reemerges at River Rise, a first-magnitude spring (Fig. 1) (Moore et al., 2009). Water transit times through the conduit system from River Sink to River Rise are estimated to be from 18 h to 6 d, depending on the river stage (Martin and Dean, 1999). At lower rates of river discharge (i.e., below ∼ 15 m3 s−1 at River Rise), there is a net gain of water in the conduits from groundwater that flows from the rock matrix porosity (Martin and Dean, 2001; Flint et al., 2023). When discharge is above ∼ 15 m3 s−1 at River Rise, river water in the conduits flows into the matrix to recharge the aquifer. For simplicity, we subsequently use the descriptors “low” and “high” flow to separate samples collected when discharge is < or > 15 m3 s−1 at River Rise, respectively.

2.2 Groundwater sampling

Spring discharge was sampled by performing hydrocasts from a canoe with a 5 L Niskin bottle (General Oceanics Inc., Miami, FL) or by pumping with a peristaltic pump (GeoTech) through PVC tubing led from the spring vent to the shore. Prior to deployment, the Niskin bottle was thoroughly cleaned with 10 bleach followed by thorough rinsing with autoclaved deionized (DI) water. The PVC tubing was decontaminated by circulating a solution of 5 hydrogen peroxide for at least 1 min and then rinsed with DI water. Water samples collected in the Niskin bottle were carefully transferred to sterile 100 mL biological oxygen demand (BOD) bottles (radioisotope incorporation analyses) or 40 mL serum bottles (dissolved inorganic carbon, DIC, production and oxygen consumption analyses) via clean silicon tubing that was inserted into the bottles. Each bottle was filled with the sample until no headspace remained and sealed with a glass or butyl stopper. To determine the initial DIC concentration, the water sample was filtered using a 0.1 µm PVDF syringe filter (Merck Millipore, Cork, Ireland) and collected in 20 mL glass DIC bottles with no headspace. Transport to the laboratory was done within 4 h of collection, with samples stored in an insulated cooler that contained water from each location to minimize temperature changes prior to analysis.

The particulate organic carbon (POC) and δ13C isotopic composition of POC (δ13CPOC) were analyzed using samples collected on 25 mm glass fiber filters (GF/F; Whatman). All sampling equipment was thoroughly cleaned with detergent and soaked overnight in 15 % HCl, followed by rinsing six times with Milli-Q water. Residual organic carbon on the tweezers and glass fiber filters was removed by combustion at 450 °C for 4 h in a muffle furnace. Particles were purged from the tubing by pumping spring water through it for several minutes before attaching the filter housing and collecting the particulate samples. After filtration, the samples were kept chilled upon returned to the laboratory and stored at −20 °C until processing.

2.3 Water properties and organic carbon content

Water temperature, pH, oxidation–reduction potential (ORP), specific conductivity, dissolved oxygen, turbidity, and depth data were obtained with a ProDSS multiparameter meter (YSI Inc.) that was calibrated prior to deployment. The data presented were collected at depths that were in the immediate vicinity and as close as possible to the vent discharge point.

DOC concentrations were measured on a Shimadzu TOC-V CSN total carbon analyzer. Three-dimensional fluorescence spectra were obtained using a Hitachi F-7000 fluorescence spectrophotometer across an excitation and emission range from 240–450 nm (5 nm intervals) and 250–550 nm (2 nm intervals), respectively. Three variables were parameterized from the spectral matrix data to describe organic matter quality: HIX (humification index), BIX (biological index), and FI (fluorescence index). When HIX values are above 16, the presence of complex mixtures of organic molecules with low H:C ratios and higher molecular weights are inferred, whereas values below 4 indicate less humic characteristics that approximate autochthonous aquatic bacteria (< 4). BIX differentiates dissolved organic matter of allochthonous (≤ 0.6) and autochthonous (∼ 0.8–1.0) origin, while FI distinguishes fulvics of terrestrial origin (≤ 1.4) from those produced by microbes (≥ 1.9) (Flint et al., 2023).

Filters for POC, δ13CPOC, and the procedural blanks were decarbonated for 3 h under HCl fumes, dried at 40 °C, and stored at −20 °C until analysis. Measurements for POC and the δ13CPOC were made using a Thermo Electron Delta V Advantage isotope ratio mass spectrometer coupled with a ConFlo II interface linked to a Carlo Erba NA 1500 CNHS elemental analyzer. All carbon isotopic data are expressed in standard delta notation relative to Vienna Peedee Belemnite (VPDB).

2.4 Cell and biomass concentration

Estimates of cell concentration were performed with 15 mL water samples that were preserved with formalin (final concentration 4 ) immediately after collection. The fixed samples were subsequently vacuum filtered (< 23.7 kPa) through a black 25 mm 0.2 µm pore size Isopore polycarbonate filter (Millipore) and a 0.45 µm pore size nitrocellulose backing filter (Whatman). DNA-containing cells on the filters were stained for 15 min with a 25 × SYBR Gold stain (Invitrogen) solution that was diluted in 0.2 µm filtered TBE (Tris borate ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, EDTA). After staining, the filter towers were washed with clean TBE, vacuum was applied to filter the excess material, and the filters were mounted on glass microscope slides with a drop of a 1:1 antifade solution (0.1 phenylenediamine : glycerol). The stained cells were visualized and digitized using a Nikon Eclipse Ni-E epifluorescence microscope equipped with a C-FL GFP filter set (excitation 450–490 nm; dichroic mirror 495 nm; emission 500–550 nm) and 4.2 megapixel Zyla 4.2 PLUS camera.

For each sample, digital images were obtained for 40 random fields of view. To maximize depth of field for the analysis, a z stack of 40 images was captured in 0.4 µm intervals (z range of 16 µm) and compiled into a single image file for each field of view. The number, size, and shape of epifluorescent cells in the acquired images were determined by software-assisted tracing, and individual observations were measured using NIS-Elements AR v4.51.00 (Nikon Inc.). The number of cells was determined based on the “brightest pixel detection” algorithm. For shape and size, a uniform “threshold cut-off” value was not applied to all samples due to differences in background fluorescence among the samples. Instead, light threshold and contrast were manually adjusted for each sample in tandem with histogram analysis of binned intensity data. This allowed visual verification that the threshold parameters selected were processing data collected from individually stained cells. Contiguous pixels with intensity values above the threshold cut-off were used to define a particle boundary, from which the area, circularity, equivalent diameter, major axis length, and minor axis length were calculated by the software. Spherical volume based on the major axis length was used to estimate biovolume following the assumption of equivalent diameter. Estimates of cell carbon using biovolume data were calculated according to Verity et al. (1992) and their conversion of 0.36 pg C µm−3 for 10 µm3 cells.

The 50 mL water samples for measurement of cellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) were collected in triplicate and sequentially filtered through 0.2 µm pore size Millex MF Millipore MCE membranes and 0.1 µm pore size Millex Durapore PVDF membrane filters using 60 mL syringes. Immediately upon return to the laboratory, the filters were stored at −20 °C and processed less than 48 h after collection. ATP was extracted from cells on the filters using the BioThema ATP Biomass Kit HS following the manufacturer's instructions except for the following modification: 500 µL of Extractant B/S was added to and used to extract ATP from each filter by purging the material into a test tube with an air-filled sterile syringe. Subsequently, 100 µL of the extracted material was mixed with 400 µL of reconstituted ATP reagent HS and immediately measured using a Turner BioSystems E5331 luminometer. The data presented for each filtered sample are the average values from three technical replications. The amount of ATP in each sample was calculated as follows: ATPsmp = , where ATPsmp is the amount of ATP in the sample (in pmol), Ismp is the sample tube intensity in relative luminosity units (RLUs), and Ismp + std is the intensity (in RLUs) in the sample tube after adding 10 µL of the 10−7 mol L−1 internal ATP standard. ATP concentration was converted into carbon biomass based on a molar ratio 250:1 for C:ATP (Karl, 1980).

2.5 Microbial respiration

Rates of oxygen consumption and production of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) were determined at in situ temperatures and calculated from the slope of linear regression models for concentration data obtained during time course experiments.

Oxygen concentration was measured in triplicate using stoppered 40 mL serum bottles containing OXSP5 oxygen sensor spots (PyroScience) and no headspace. Killed controls were prepared in triplicate by amending samples with benzalkonium chloride to a final concentration of 0.01 . Bottles were incubated in an Innova 44 incubator (New Brunswick) at 21 °C, except for samples collected at River Sink during low flow, which were incubated at the in situ temperature of 15 °C. At daily intervals, oxygen concentration was measured using a calibrated FireSting®-O2 (one-channel) fiber-optic oxygen meter (PyroScience). A serum bottle containing deionized water was incubated with the samples to serve as the temperature reference for the oxygen measurements.

Upon returning to the laboratory, the sample bottles for measurement of DIC production were incubated a 21 °C (except River Sink during low flow, which was incubated at 15 °C). After 24, 48, and 96 h of incubation, triplicate bottles of the water were filtered through a 0.1 µm pore size syringe filter (Merck Millipore, Cork, Ireland) into clean 20 mL DIC vials. Vials were stored at 4 °C and measured within 2 weeks of terminating the experiment. Total DIC was measured using a UIC (Coulometrics) 5017 CO2 coulometer coupled with an AutoMate automated carbonate preparation device (AutoMateFX, Inc.). Approximately 5 mL of sample was weighed into septum top tubes and placed into the AutoMate carousel. Acid- and CO2-free nitrogen carrier gas was then injected into the sample vial through a double needle assembly, and evolved CO2 was carried through a silver nitrate scrubber to the coulometer where total carbon was measured.

The respiratory quotient (RQ) was determined by dividing the molar rate of DIC production by the rate of O2 consumption. The average oxygen utilization rate (OUR) was calculated for paired samples at the Sink Rise system by subtracting the oxygen concentration at River Sink from the oxygen concentration at River Rise and dividing by the estimated residence time based on the hydrological stage (assumed to be 18 h for high flow and 6 d for low flow; Martin and Dean, 1999). For Head Spring and Devil's Eye Spring, OUR was calculated by assuming the initial oxygen concentration when recharge occurred to be atmospherically equilibrated water at 21 °C and sea level (8.5 mg L−1).

2.6 3H-leucine and 3H-thymidine incorporation

Radioassays consisted of 0.8 mL water samples that were placed into 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes and amended with 0.2 mL of a solution containing 3H-thymidine (thymidine [methyl-3H], 50.8 Ci mmol−1 in sterile water) or 3H-leucine (L-leucine [4, 5-3H], 160 Ci mmol−1 in ethanol water 2:98; PerkinElmer). The final concentration for each was 20 nM, which corresponded to 1 µCi per sample for the 3H-thymidine assays and 3.2 µCi per sample for 3H-leucine. Killed controls were prepared by adding 200 µL of 50 formalin to designated water samples. Six replicates per time point were established for the experimental and control groups. All samples were incubated at 21 °C in the dark.

At designated time intervals during the experiment (48 h for Devil's Eye, Madison Blue, and River Rise at high flow; 24 h for all other samples), subsets of the samples were killed by adding 200 µL of 50 formalin and stored at 4 °C. Acid-insoluble macromolecules were precipitated by adding 200 µL of an ice-cold solution of 100 trichloroacetic acid (TCA) followed by centrifugation at 15 000 × g for 15 min. Samples were then sequentially washed with 5 TCA and 70 ethanol with a 5 min centrifugation at 15 000 × g after each wash. The washed pellets were suspended in 1 mL of scintillation cocktail (CytoScint, MP Biomedicals), the tubes were placed into scintillation vials, and radioactivity was measured on the 3H channel of a Beckman LS6500 scintillation counter for 10 min. To determine disintegrations per minute from the count per minute data, the counting efficiency was calculated using a quench curve and 3H-toluene standard (PerkinElmer) with a specific activity of 2.552×106 dpm g−1. The curve was based on data generated by mixing 20 mL of scintillation cocktail (CytoScint) with 42 335 dpm (20 µL) of 3H-toluene (MP Biomedicals) and 0 %, 0.25 %, 0.5 %, 1 %, 1.5 %, 2 %, 2.5 %, 4 %, and 5 % acetone (v/v).

To convert 3H-thymidine and 3H-leucine incorporation rates to cell carbon and estimate heterotrophic production, standard conversion factors of 2.0 × 1018 cells mol−1 were used for 3H-thymidine (Fuhrman and Azam, 1980) and 1.42 × 1017 cells mol−1 for 3H-leucine (Chin-Leo and Kirchman, 1988). Cellular carbon content was based on values estimated from biovolume. Bacterial growth efficiency (BGE) was calculated as the quotient between carbon incorporated into biomass and the sum of carbon incorporated into biomass plus that respired as DIC.

3.1 Hydrogeochemistry

The groundwater discharged from sites in the Ichetucknee spring group (Head Spring, Blue Hole Spring, Coffee Spring, Devil's Eye Spring, and Mission Spring) had little interaction with surface waters during its subsurface residence time, and these springs discharge continuously at rates that vary by less than a factor of 3 (Martin and Gordon, 2000; Katz, 2004). In comparison, members of the reversing spring group (Madison Blue Spring, Gilchrist Blue Springs, Peacock Springs, and Little River Spring) experience a reversal of flow when river water levels exceed groundwater heads, which is indicated by negative discharge. For instance, there were eight occasions from 2018 to 2022 when the stage of the Withlacoochee River resulted in the flow reversal of Madison Blue Spring. We had opportunities to sample Madison Blue Spring and Peacock Springs during periods when they were reversing (Tables 1 and S1). Observed DO concentrations during reversals (7.21 and 3.86 mg L−1 for Madison Blue Spring and Peacock Springs, respectively) were at least twice as high as the values when discharge was positive. The samples we analyzed from Madison Blue Spring for POC, DIC, oxygen consumption, and heterotrophic production were all collected in 2022 and at time frames of 1 to 104 d after it had transitioned from negative to positive discharge.

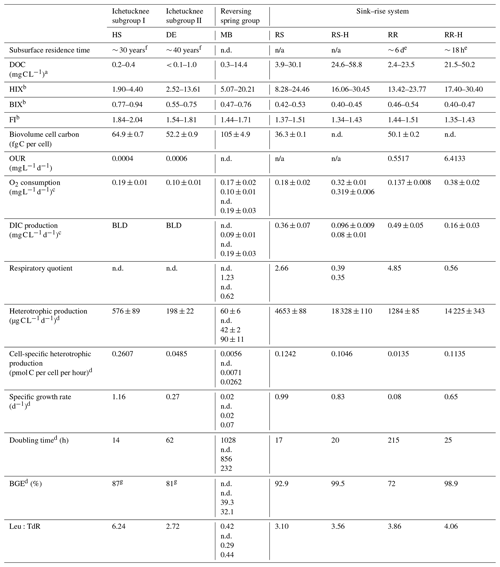

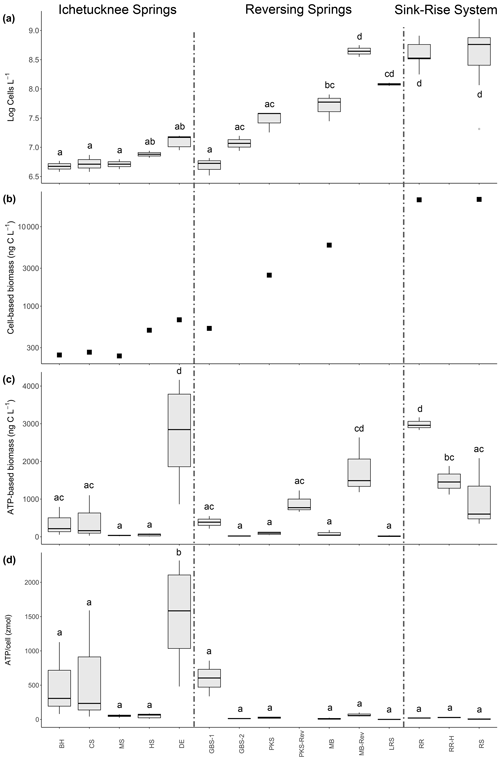

Table 2DOC concentration and quality, biogeochemical data, and microbial physiological properties derived from the rate data. RS-H and RR-H: River Sink and River Rise under high-flow conditions, respectively. n/a – not applicable.

a Data from Flint et al., 2021. b DOC quality data were collected between August 2018 through March 2022. c Error (±) is based on the slope uncertainty and not the standard error. d Based on 3H-leucine incorporation and DIC production rates. g Based on the oxygen consumption data and a theoretical RQ = 1.2 (Berggren et al., 2012). Residence time data are from e Martin and Dean (1999) and f Martin et al. (2016). Multiple values for a given parameter represent independent measurements from different dates in chronological order (see Table S1), and for Madison Blue Spring, these samples correspond to 51, 1, 104, and 91 d, respectively, after a reversal. n.d.: no data; BLD: below the level of detection of this analytical procedure.

The physical and chemical properties of groundwater discharged from the Ichetucknee and reversing spring groups showed minimal variation over 48 months of observation, and their clear (turbidity values near 0 FNU), circumneutral waters had an average temperature of 21.83 ± 0.07 °C (n=65; ± the standard error; Table 1). There are statistically significant differences in specific conductance (SpC; ANOVA p < 0.05), oxidation–reduction potential (ORP; p < 0.001), and DO concentration (p < 0.001) among the Ichetucknee and reversing spring groups. Discharge from Peacock Springs and Little River Spring had the highest SpC values, and Devil's Eye Spring and Mission Spring had the lowest DO concentration (average of 0.21 and 0.55 mg L−1, respectively; Table 1). Water quality parameters from the Santa Fe sink and rise system ranged widely depending on hydrological conditions (Table 1). When groundwater was transported into the conduit during periods of low flow, water at River Rise had characteristics similar to matrix water (i.e., water contained in matrix porosity; Moore et al., 2009), for example, temperature that tended to approach 21 °C and SpC higher than Santa Fe River source waters. Variation in these physical water properties during periods of high flow coincided with increasing DOC concentration and HIX (Table 2), indicating that the distinct hydrological regimes in the sink–rise system were associated with appreciable changes in the quantity and quality of organic matter.

Figure 2POC concentration (a) and the δ13C of POC (b) in samples from the springs and sink–rise system. DE: Devil's Eye Spring; HS: Head Spring; MB: Madison Blue Spring; RS: Santa Fe River Sink; RR: Santa Fe River Rise. Lowercase letters indicate the significance groups based on a Tukey HSD test. RR-H and RS-H are samples taken during high flow at the sink–rise system.

Results of a one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey HSD (honestly significant different) analysis showed POC concentration was significantly higher at locations with the highest surface water influence (River Sink and River Rise; ANOVA p < 0.001, F = 22.007; Fig. 2a). Head Spring, Devil's Eye Spring, and Madison Blue Spring had the lowest concentrations of POC (< 0.03 mg C L−1; ANOVA p < 0.001, F = 22.007) and DOC (0.2 to 0.4 mg C L−1; Flint et al., 2021). The heaviest δ13C value for POC was observed at Madison Blue Spring (average of −28.7 ± 0.3 ‰), which was enriched by approximately 2 ‰ and 4 ‰ relative to locations with less surface water influence (Devil's Eye Spring (−31.6 ± 0.3 ‰) and Head Spring (−32.5 ± 1.4 ‰), respectively; Fig. 2b). Though average values for δ13CPOC were isotopically lighter in samples from the sink–rise system during low flow, the differences are not significantly different from those at high flow (Fig. 2b). Dissolved organic matter with HIX values below 10, BIX above 0.8, and FI above 1.9 is generally viewed to be of high quality (e.g., Flint et al., 2023). HIX values indicate that springs with the oldest groundwater (the Ichetucknee spring group) had the lowest humic content, and higher values for FI and BIX imply the organic matter was of higher quality relative to the other springs sampled (Table 2). Though much higher concentrations of DOC were observed in water from the sink–rise system (Flint et al., 2023), the HIX, FI, and BIX values are indicative of lower-quality organic matter. Higher concentrations of DOC and POC were observed during periods of high flow at River Sink, but there is not a statistical difference in POC concentration with flow stage at River Rise (Fig. 2a).

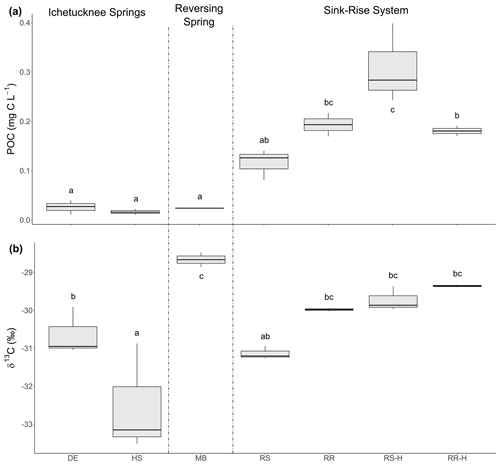

Figure 3Cell abundance and biomass estimates in samples collected from various springs and sink–rise system. (a) Log10-transformed data for cell abundance. (b) Microbial biomass based on cell volumetric data derived from microscopic observations. (c) Microbial biomass based on the concentration of cellular ATP retained in the 0.2 µm fraction. (d) ATP concentration per cell (in zeptomoles). BH: Blue Hole Spring; CS: Coffee Spring; MS: Mission Spring; HS: Head Spring; DE: Devil's Eye Spring; GBS1: Gilchrist Blue Springs vent 1; GBS2: Gilchrist Blue Springs vent 2; PKS: Peacock Springs; MB: Madison Blue Spring; LRS: Little River Spring; RR: Santa Fe River Rise; RS: Santa Fe River Sink. Samples labeled with the suffix -Rev indicate those taken during a spring reversal, and the suffix -H indicates those taken during high flow at River Rise. Lowercase letters indicate the significance groups based on a Tukey HSD test.

3.2 Microbial cell and biomass concentrations

The results of a one-way ANOVA (p < 0.001, F = 28.35) indicate significant differences in cell concentration means among analyzed samples from the 10 springs and the sink–rise system (Fig. 3a). The lowest cell concentrations were observed in samples from the Ichetucknee spring group, which ranged from 4.83 ± 0.50 × 106 cells L−1 at Blue Hole Spring to 1.29 ± 0.05 × 107 cells L−1 at Devil's Eye Spring. Reversing springs (i.e., Madison Blue Spring, Peacock Springs, and Little River Spring) generally had higher average cell concentrations at baseflow than those in the Ichetucknee spring group, but only samples from Little River Spring were significantly higher (Tukey HSD test, p < 0.001). Cell concentration means at locations with the largest surface water contribution (i.e., River Sink and River Rise, 6.08 ± 0.8 and 4.35 ± 0.4 × 108 cells L−1, respectively) are significantly higher (p < 0.001) than all other samples except those from Little River Spring and Madison Blue Spring, when the high river stage had reversed spring flow (Fig. 3a).

From a total of 198 700 individual biovolume measurements, 1029 extreme outliers (i.e., values of Q3 + (3 × IQR) or Q1 − (3 × IQR): Q3 – third quartile; IQR – interquartile range; Q1 – first quartile) were identified among the samples and removed. Subsequent analyses were conducted on an average of 19 762 ± 6160 observations per sample. Average biovolume in the groundwaters and surface waters sampled was 0.1259 ± 0.0003 µm−3, ranging from a high of 0.36 ± 0.02 µm−3 (Madison Blue Spring) to a low of 0.1010 ± 0.0003 µm−3 (River Sink). A Kruskal–Wallis test indicated there were significant differences in biovolume among the samples (p < 0.001). Therefore, cell carbon estimates were calculated separately for each spring. A sample from River Sink at low flow had the lowest average cellular carbon content (36.3 ± 0.1 fg C per cell; Fig. S1 in the Supplement), which is significantly lower than values at other sites (post hoc Dunn test; p < 0.001). The highest cellular carbon content of 105 ± 5 fg C per cell was observed at Madison Blue Spring (Table 2) from a sample collected 83 d after the spring had reversed from negative to positive discharge. Multiplying cell carbon by cell concentration provides a total estimate of microbial biomass (Fig. 3b), which is strongly correlated with cell abundance (Spearman r = 0.988; Fig. 3a). Microbial biomass in samples from the sink–rise system (River Sink, 22 065 ng C L−1; River Rise, 21 799 ng C L−1; Fig. 3b) was ∼ 100 times higher than that of the oldest groundwater from the Ichetucknee spring group (236 to 673 ng C L−1). The quantity of carbon biomass in samples from Devil's Eye Spring and Head Spring corresponded to 3 % of the carbon in POC (Fig. 2a), whereas much higher fractions of the POC were inferred to be microbial biomass in samples from Madison Blue Spring (24 %) and the sink–rise system (24 % and 11 % for River Sink and River Rise, respectively).

Most extractable ATP (79 % to 99 %) was associated with cells retained on the 0.2 µm pore sized filters. Unexpectedly, cells in the > 0.2 µm fraction from Devil's Eye Spring contained ATP concentrations ∼ 15 times higher than those observed in samples from other springs in the Ichetucknee spring group as well as the reversing spring group, with values similar to those for the sink–rise system (Fig. S2). The inferred ATP concentration per cell (Fig. 3d) in samples from Devil's Eye Spring are significantly higher (p < 0.001; 1516 ± 300 zmol ATP per cell) than all other observations (range of 1.25 to 622.32 zmol ATP per cell). The trend in carbon biomass estimated from the cellular ATP concentration (Fig. 3c) generally agrees with that based on biovolume (Fig. 3b) but with exceptions. For instance, low biomass is inferred for most Ichetucknee and reversing springs with positive rates of discharge, the latter of which significantly increased during periods of reversal when contributions from surface water predominate (Fig. 3c). Although the Ichetucknee springs have groundwater with the longest residence time, biomass carbon for Devil's Eye Spring based on ATP data was significantly higher than for the other Ichetucknee springs (Fig. 3c) and not statistically different from River Rise samples that contained ∼ 15-fold more cells (Fig. 3a). ATP-based biomass concentrations in samples from River Rise at low flow are significantly higher than values at high flow and ∼ 3-fold lower than those observed for River Sink at low flow (Fig. 3c). As ATP is considered a proxy for viable biomass (e.g., Oulahal-Lagsir et al., 2000; Köster and Meyer-Reil, 2001), we used the ratio between biomass estimates derived from biovolume (Fig. 3b) and ATP concentration (Fig. 3c) to assess trends that may be related to viability of the groundwater communities. ATP-based biomass in the reversing spring group ranged from 1.4 % (Madison Blue Spring) to 38.5 % (Gilchrist Blue Springs) of the biovolume-based biomass estimates, whereas values for River Rise and River Sink were 4.6 % and 13.7 %, respectively. In contrast, ATP-based biomass was up to 4-fold higher than estimates inferred from biovolume for the oldest groundwaters in the Ichetucknee spring group (Blue Hole Spring, Coffee Spring, and Devil's Eye Spring: 145 %, 163 %, and 404 %, respectively).

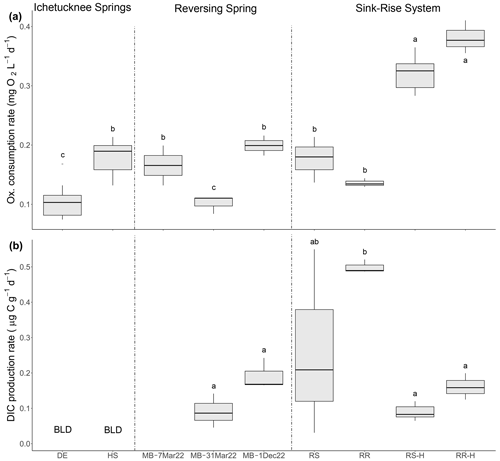

Figure 4Rates of oxygen consumption (a) and DIC production (b) in select springs and sink–rise system. Letters indicate significance groups based on a Tukey HSD test. DE: Devil's Eye Spring; HS: Head Spring; MB: Madison Blue Spring; RS: Santa Fe River Sink; RR: Santa Fe River Rise. DIC production data are not available for the Madison Blue Spring sample collected on 7 March 2022. Samples labeled with the suffix -H indicate those taken during high flow at River Sink and River Rise. BLD: below detection limit.

3.3 Microbial respiration

The rate of oxygen consumption was highest in samples from River Rise and River Sink, with rates at high flow (0.382 and 0.322 , respectively) being approximately twice those observed during low flow (0.137 and 0.178 , respectively; Fig. 4a; Table 2; Fig. S3). In contrast, rates of DIC production during low flow were at least 3 times higher than those observed during high-flow conditions (Fig. 4; Table 2). The lowest oxygen consumption rates were in groundwaters from Devil's Eye Spring (0.102 ) and samples taken at Madison Blue Spring 1 d after a period of flow reversal (31 March 2022; 0.101 ). Significantly higher rates of oxygen consumption (ANOVA F = 44.912, p < 0.001) were measured in discharge from Head Spring (0.189 ), as well as in samples from Madison Blue Spring (0.168 and 0.199 ; Fig. 4a) that occurred 51 and 91 d, respectively, after it had transitioned from negative to positive rates of discharge. A higher rate of oxygen consumption in the 91 d sample from Madison Blue Spring matched a DIC production rate that was ∼ 2-fold higher than values observed immediately after the transition from reversing conditions (Fig. 4b). Unfortunately, the poor fit of the DIC data from Devil's Eye Spring and Head Spring to the regression models (r2 ≤ 0.2; Fig. S4) coupled with no statistically significant change in concentration over time prevented an estimate of DIC production by this method. The observed molar ratio of DIC produced to oxygen consumed (i.e., respiratory quotient, RQ) for Madison Blue Spring 91 d after a reversal event (0.62) was approximately half that measured after 1 d of positive discharge (1.23). At the sink–rise system, RQ was much higher during low flow (4.85 and 2.66 for River Rise and River Sink, respectively) when there was more influence from groundwater than at high flow when surface water contributions to the conduits were the largest (0.56 and 0.37, respectively; Table 2).

At low flow in the sink–rise system, the OUR (0.55 ) was higher but similar to measured rates of oxygen consumption (0.14 ); however, OUR at higher flow (6.41 ) was ∼ 16-fold higher than measured oxygen consumption rates (Table 2). The largest discrepancy documented was for the oldest groundwaters of the Ichetucknee spring group, which had measured rates of oxygen consumption (Fig. 4a) 3 orders of magnitude higher than OUR (1.26 to 5.68 × 10−4 ; Table 2).

3.4 Heterotrophic carbon assimilation

Observed rates of 3H-leucine incorporation exceeded those for 3H-thymidine, except for the samples from Madison Blue Spring, where 3H-thymidine incorporation rates were up to 3-fold higher than those for 3H-leucine incorporation (Fig. S5). The highest rates of incorporation were observed in samples from River Sink and River Rise that also contained the highest cell and biomass concentrations (Fig. 3). The molar ratio of 3H-leucine to 3H-thymidine incorporation (Leu:TdR) was very low (< 0.45) for observations from Madison Blue Spring and much lower than the groundwater with the longest residence time (Devil's Eye, 2.72; Table 2). The largest Leu:TdR ratios were observed in samples from River Sink (3.10), River Rise (4.06), and Head Springs (6.24).

To estimate doubling times from the 3H-leucine and 3H-thymidine incorporation data, we assumed that all cells in the samples (Fig. 3a) were viable and capable of incorporating the radiotracers into newly synthesized protein and DNA. Therefore, the values derived correspond to maximum reproduction estimates for the cell populations. Doubling times calculated from cell-specific rates of 3H-leucine (Table 2) and 3H-thymidine incorporation negatively correlates with dissolved oxygen (r = −0.79 to −0.86, p < 0.05). However, the separate radiotracers did not provide matching reproduction rates, with values based on 3H-thymidine incorporation being 2 to 50 times shorter than those based on 3H-leucine incorporation. Given that freshwater bacteria have shown preferential uptake of leucine over thymidine (e.g., Pérez et al., 2010), we used the 3H-leucine incorporation rates to further evaluate rates of growth and cell carbon production in the groundwaters and surface waters studied. Doubling times of 20 h at River Sink were shorter than those at River Rise and under low-flow conditions, with doubling time increasing to nearly 9 d at River Rise when groundwater had been flowing into the conduits (Table 2). Much longer doubling times of 10 to 42 d were inferred at Madison Blue Spring (i.e., when discharge rates were positive) in comparison to the older groundwaters analyzed from the Ichetucknee spring group (14 h for Head Spring and 62 h for Devil's Eye Spring).

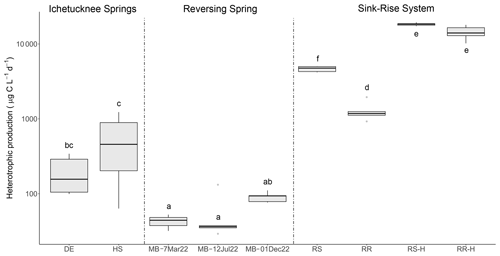

Figure 5Rates of heterotrophic carbon production based on 3H-leucine incorporation data. Letters indicate significance groups based on a Tukey post hoc analysis. DE: Devil's Eye Spring; HS: Head Spring; MB: Madison Blue Spring; RS: Santa Fe River Sink; RR: Santa Fe River Rise. Samples labeled with the suffix -H indicate those taken during high flow at River Sink and River Rise.

A standard leucine-to-carbon conversion factor was used to estimate heterotrophic productivity based on the rate of 3H-leucine incorporation (Fig. 5). The values obtained for heterotrophic productivity on three dates at Madison Blue Spring were the lowest observed (42.9 to 90.6 ). Based on an ANOVA (p < 0.001, F = 144.183) and Tukey HSD post hoc analysis, heterotrophic productivity for Devil's Eye Spring (198 ) and Head Spring (576 ) was significantly higher than at least two of the three observations from Madison Blue Spring (Fig. 5). The highest rates of heterotrophic production were measured during high flow and surface water inputs in the sink–rise system (River Sink and River Rise; 18 328 and 14 225 , respectively), which were significantly different from (ANOVA p < 0.001, F = 188.553) and 4- and 11-fold higher, respectively, than values at low flow and when groundwater enters the conduits (Fig. 5). Low-flow conditions coincided with significantly higher rates of heterotrophic production at the sink (ANOVA p < 0.001, F = 205.016; 4653 ) versus the rise (1285 ). A high correlation of heterotrophic production rates with DOC concentration (r = 0.86, p < 0.05; Fig. S7a) and quality (HIX, r = 0.86; Fig. S7d BIX and FI, r = −0.85; p < 0.05; Fig. S7b and c) support the fact that both the availability and characteristics of DOC influenced the growth of the surface water and groundwater communities. Cell carbon incorporation rates derived from 3H-thymidine follow a similar pattern among samples as those derived from 3H-leucine but in general implied higher rates of heterotrophic production at most sites (Fig. S8). The trend for cell-specific rates of heterotrophic productivity based on the 3H-leucine data (Table 2) is quite different from that for bulk values (Fig. 5), with the highest cell-specific rates observed at Head Spring exceeding those for surface waters at River Sink by ∼ 2-fold.

Very high growth efficiencies were inferred from estimates of heterotrophic production (3H-leucine data) and respiration (DIC production data) for samples from the sink–rise system (93 % to 99 %), with a decreased BGE of 72 % at River Rise under low-flow conditions and when groundwater contributions were highest. The lowest BGEs (39 % and 32 %) were found in samples collected from Madison Blue Spring at least 3 months after a period of flow reversal (Table 2). Although we were unable to empirically determine respiration rates using the DIC concentration data collected from Devil's Eye Spring and Head Spring, BGE values based on the oxygen consumption rate and a theoretical RQ of 1.2 (Berggren et al., 2012) were high (81 % and 87 %, respectively) and implied that a lower proportion of the DOC utilized was lost as CO2 in comparison to the groundwater sampled from Madison Blue Spring.

4.1 Groundwater and surface water mixing in karst landscapes

Studies that have examined microbial production in aquifer ecosystems have deepened understanding of subsurface carbon cycling and the biogeochemical processes contributing to groundwater quality (e.g., Wilhartitz et al., 2009; Hofmann and Griebler, 2018; Karwautz et al., 2022). Research over recent decades in silicate-dominated aquifer systems has contributed greatly to these discussions, but there has been less emphasis on landscapes composed predominately of carbonate minerals (Covington et al., 2023). A key aspect of karstic aquifers is the fractures and conduits that enhance permeability and water flow within their geological formations, facilitating relatively rapid exchange of dissolved gases, nutrients, organic matter, and microbes between surface waterbodies and groundwater. The groundwater discharged from springs in north central Florida tends to be organic carbon poor and suboxic in contrast to surface waters that are organic-carbon-rich and with DO near equilibration with atmospheric oxygen (Moore et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2016; Flint et al., 2021; Oberhelman et al., 2023). In recent decades, there have been alarming trends in groundwater quality that have raised concerns about the health of Florida's springs, including decreased rates of discharge (Florida Springs Institute, 2018), increased abundance of reactive nitrogen species (Katz, 2004; Katz et al., 2001, 2009; Denizman, 2018), and lower DO concentration in the groundwater and spring runs (Heffernan et al., 2010). Consequently, this region provides a model experimental setting to evaluate the effects of surface-derived substrate delivery on microbial consumption of organic matter and biomass production in karstic groundwater.

4.2 Effects of groundwater residence time on microbes, biomass, and organic carbon

Cell concentrations in groundwater from the Ichetucknee spring group (Fig. 3a) are similar to those reported in previous studies of springs in this region (Malki et al., 2020, 2021) and other oligotrophic karstic groundwaters (Farnleitner et al., 2005; Wilhartitz et al., 2007, 2009, 2013; Hershey et al., 2018). In comparison, water samples from the reversing springs and sink–rise system had higher DO (Table 1), DOC (Table 2), cell (∼ 107 to 109 cells L−1), and biomass (Fig. 3b and c) concentrations. Biomass estimates based on biovolume (Fig. 3b) are largely congruent with those derived using ATP data for most of the Ichetucknee springs and the reversing spring group when their discharge rates were positive (Fig. 3c). The ATP-based biomass data reveal an effect of surface waters on the microbial communities, showing significantly higher values during periods of spring reversal and during hydrological conditions when groundwater mixing occurred at River Rise. For the Ichetucknee spring group, the ATP data provided higher biomass estimates in comparison to those derived from biovolume, with Devil's Eye Spring having the largest discrepancy (Fig. 3b and c). Our data and related calculations imply that average cellular ATP contents in populations discharged with suboxic, oligotrophic groundwater at Devil's Eye Spring (Fig. 3d) were at least 4-fold higher than those at other sites and approach those reported in laboratory-cultured bacteria (e.g., 2000 zmol; Thore et al., 1975). High ATP contents are associated with cells that have large biovolumes and rapid metabolisms (e.g., Eydal and Pedersen, 2007), but neither of these explanations are consistent with the data observed at Devil's Eye Spring (Table 2). As such, we hypothesize that the lower anabolic rates and energy consumption allow ATP to accumulate within cells.

The quantity and quality of organic matter is a crucial determinant of heterotrophic metabolism and biomass production rates (Hosen et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2018). Surface water from the sink–rise system had the highest concentrations of DOC (Table 2) and POC (Fig. 2a), but according to high HIX and low FI and BIX values (Table 2), the DOC origin was terrigenous and of lower quality. Although groundwater discharged from Head Spring and Devil's Eye Spring had DOC and POC concentrations similar to those at Madison Blue Spring, DOC quality in the latter reversing spring was intermediate to values for River Rise and River Sink (Table 2). Bioavailability of the microbially derived, protein-like DOC in the Ichetucknee springs (Flint et al., 2023) was confirmed by the relatively high rates of cell-specific production observed in these samples (Table 2). The δ13CPOC data also provided evidence for differences in the carbon sources available (Fig. 2b), with the isotopically lightest δ13CPOC from Head Spring coinciding with the shortest community doubling time observed (14 h) among the groundwaters and surface waters sampled (Table 2).

4.3 Hydrology and DOC influence microbial respiration

The rates of oxygen consumption in oligotrophic groundwaters discharged from the Ichetucknee and reversing springs (0.1 to 0.2 ) were within the range observed in the DOC-rich waters of the sink–rise system during low flow (Table 2). Significantly lower values occurred only in suboxic groundwater discharging from Devil's Eye Spring and Madison Blue Spring 1 d after it transitioned from negative to positive discharge (Fig. 4a). The low rates of oxygen consumption and DIC production observed in samples from Madison Blue Spring immediately following a reversal event may represent a temporal biogeochemical response of reversing spring systems. In the organic-rich waters at the sink–rise system, the highest rates of oxygen consumption were detected under high-flow conditions, whereas the highest rates of DIC production were observed during low flow (Fig. 4; Table 2) and when there was a substantial contribution of groundwater to the conduits (Flint et al., 2023). Transitions in the hydrological stage in the sink–rise system during river flooding led to increases in the DO (average of 1.6 and 3.2 mg L−1 at River Rise to 4.18 and 5.29 mg L−1 at River Sink during low and high flow, respectively; Table 1) and DOC concentration, but higher values of HIX suggest the DOC was of poorer quality (Table 2). While incomplete oxidation of lower-quality DOC at high flow is possible, reduced oxygen concentrations during low flow should enable additional microbial sources of DIC from fermentative and anaerobic respiratory metabolisms. In particular, water discharged at River Rise contains supersaturated concentrations of dissolved N2O that has been generated via denitrification, and N2O concentrations are consistently higher under low-flow conditions (Flint et al., 2023). Hence, a component of DIC produced at River Rise, as well as in the N2O-saturated discharge of Madison Blue Spring (Flint et al., 2021), has likely originated from heterotrophic denitrification in the groundwater.

RQ values based on DIC production and oxygen consumption rates (0.35 to 4.85; Table 2) deviate from the generally assumed range of 0.8 to 1.2 that is based on the stoichiometry of oxidation for specific organic compounds. However, they are commensurate to the wide range of values that have been reported for natural bacterial assemblages in freshwater ecosystems (0.25 to 4.6; Berggren et al., 2012). At the sink–rise system, the increase in RQ from < 0.6 at high flow to 2.66 and 4.85 at low flow implies a carbon source transition to highly oxidized, low-molecular-weight organic acids (Berggren et al., 2012; Allesson et al., 2016; Hilman et al., 2022) and/or an effect of supplementary DIC sources from anaerobic metabolisms (Flint et al., 2021, 2023). Decreasing methane concentrations and enrichment of δ13CH4 from River Sink to River Rise indicates a contribution from methanotrophy (Oberhelman et al., 2023), which has a theoretical RQ of 0.5 (Bastviken et al., 2008) and may partially explain the low RQ values observed during high flow (Table 2). RQ values for Madison Blue Spring (1.23 and 0.62) were based on data collected 1 and 94 d, respectively, after a period of reversal, supporting the contention that relatively short residence times in the aquifer affect the physiology of and carbon consumption by the groundwater community.

To compare the empirical oxygen consumption rates with estimates based on mixing of groundwater with atmospheric gases (i.e., OUR), we assumed that water enters the aquifer saturated with atmospheric oxygen and constant rates of oxygen consumption during the subsurface residence time, and aerobic respiration was the only oxygen sink. For springs discharging the oldest groundwater (i.e., Head Spring and Devil's Eye Spring), OUR grossly underestimates the observed oxygen consumption rate by 433- and 180-fold, respectively (Table 2). OUR values for River Rise are more congruent with measured rates and overestimate oxygen consumption by 4- and 16-fold during low and high flow, respectively (Table 2). A “dramatic” decrease in the DO concentrations of groundwater discharged by springs in this region has been documented since the 1970s (Heffernan et al., 2010). Although the biogeochemical basis for the decrease in DO is not well understood, the temporal trend coincides with increasing concentrations that have also been observed in spring discharge over the last ∼ 70 years (Hornsby et al., 2004; Munch et al., 2007). Elevated levels of reactive nitrogen species have been implicated in enhancing N2O production in the UFA (Flint et al., 2021), but it is currently not known if nitrogen eutrophication of the groundwater may also be enhancing microbial metabolic rates in the subsurface.

4.4 Effect of surface-water–groundwater interactions on heterotrophic growth

In the organic-matter- and DO-rich surface waters of River Sink, biomass was produced at rates exceeding those reported for the Amazon River (28 ; Benner et al., 1995) that were comparable to values for high-organic-matter river systems such as the Columbia River estuary (3120 to 114 240 ; Herfort et al., 2017). Groundwater contributions to the sink–rise system are minimized when discharge rates are high (> 15 m3 s−1), and while these hydrological conditions tend to increase DO and DOC concentration, the terrigenous-derived DOC was generally of lower quality than that observed when groundwater was entering the conduits (Flint et al., 2023). Nevertheless, rates of heterotrophic production, cell reproduction, and oxygen consumption in the sink–rise system decreased during low-flow conditions (Tables 1 and 2). One possibility is that metabolism becomes limited by electron acceptor availability, similar to biogeochemical scenarios described for the conduits of Madison Blue Spring during periods of reversal (Brown et al., 2014, 2019). Though BGEs as high as 80 % have been reported in aquatic systems (Del Giorgio and Cole, 1998; Eiler et al., 2003), the values inferred from the 3H-leucine and DIC data for River Sink and River Rise (> 92 %) are so high they suggest our experimental approach underestimated microbial respiration or overestimated heterotrophic production in these samples. The former possibility is less likely given that we expect additional CO2 formed via anaerobic metabolisms in these waters, which should result in an overestimate of aerobic respiration based on ΔDIC. Very similar and high BGEs values (> 90 %) are also derived from the 3H-thymidine incorporation data, leading us to conclude that both of these methods overestimated heterotrophic production (e.g., see Giering and Evans, 2022) in samples from the sink–rise system.

Heterotrophic production was lower in groundwater discharging from the reversing and Ichetucknee springs than surface waters from the Santa Fe River, and 4 to 8 orders of magnitude higher than that reported for a karstic aquifer in the European Alps (Wilhartitz et al., 2009) and oligotrophic groundwater from sand and gravel aquifers (Hofmann and Griebler, 2018; Karwautz et al., 2022). Assuming standard responses for reaction kinetics (i.e., Q10 values of 2 to 3; Gillooly et al., 2001), temperature-dependent reaction kinetics cannot fully explain the differences between rates in the UFA (∼ 22 °C) and alpine and sand gravel aquifers (4 and 12 °C, respectively; Hofmann and Griebler, 2018; Karwautz et al., 2022). There are multiple potential reasons for the observed higher rates of microbial productivity in UFA groundwater, and several observations make a case for higher bioavailability of organic matter. Higher availability of metabolizable organic matter in the UFA groundwater samples was substantiated by the much shorter inferred doubling times (from 0.58 d for Head Spring to 43 d for Madison Blue Spring; Table 2) when compared to those for alpine karst aquifer (712 d, groundwater residence time of ∼ 22 years; Wilhartitz et al., 2009) and oligotrophic groundwater (533 d; Karwautz et al., 2022) systems. We also observed that microbes discharged from Head Spring had the highest rate of leucine relative to thymidine incorporation, potentially representing a response to growth-limiting conditions (e.g., Church, 2008). Nevertheless, these populations had rates of specific heterotrophic production (0.2607 pmol C per cell per hour) that were twice the values for surface waters (Table 2) and 2 to 5 orders of magnitude higher than those for groundwater of comparable residence time (Wilhartitz et al., 2009). Lastly, the DOC examined in telogenetic alpine aquifers was generally of lower quality (i.e., average FI of 1.6; Harjung et al., 2023) relative to that in the Ichetucknee springs (average FI of 1.78).

When the Withlacoochee River level is low, groundwater discharging to Madison Blue Spring run has a similar composition and DOC concentration to that in the nutrient-limited Ichetucknee springs (Table 1), yet a large disparity was observed in reproduction rates (Table 2). During the period of study, Madison Blue Spring reversed flow eight times – events that transported electron donor- and acceptor-rich river water directly into the subsurface. Large volumes of water can recharge during reversals, and during a 7.5 d reversal in 2009, an estimated ∼ 5.8 × 104 m3 of river water recharged the conduits of Madison Blue Spring (Gulley et al., 2011). Increases in bioreactive solute concentration during reversals coincide with transient microbial blooms that have been observed by cave divers in the typically nutrient-limited environment of the conduits (Gulley et al., 2011, 2013; Brown et al., 2014). Based on these observations, we hypothesized that metabolic rates of subsurface communities in reversing springs would be intermediate to those of the Ichetucknee springs and sink–rise system. Though respiration rates (Fig. 4) and DO, DOC, and POC concentrations (Table 2; Fig. 2a) at Madison Blue Spring were similar to other UFA groundwaters, the cell carbon production rates were at least 2-fold lower than those for the Ichetucknee springs (Fig. 5; Table 2) and do not fully support our initial hypothesis. The heterotrophic production and respiration data from Madison Blue Spring produced BGEs (32 % and 39 %) that are lower than other sites (Table 2) and comparable to values from oligotrophic portions of the ocean (Del Giorgio and Cole, 1998) and subsurface aquatic systems in Antarctica (Vick-Majors et al., 2016). Low BGE at Madison Blue Spring could indicate uncoupling between catabolism and anabolism, which is consistent with low leucine to thymidine incorporation ratios (Table 2) that imply its groundwater community was investing most of their energy flow in maintenance metabolism rather than growth (e.g., Chin-Leo and Kirchman, 1990; Wos and Pollard, 2012). Previous investigations at Madison Blue Spring have shown altered groundwater chemistry for a period of ∼ 1 month after each reversal (Brown et al., 2014). Considering our sampling intervals after reversal (i.e., Fig. 5 data were collected 52 to 107 d after a transition from negative to positive discharge), there may be a protracted effect of spring flow reversal on microbial metabolism in groundwater.

Groundwater discharged from unconfined portions of the UFA contained low standing stocks of microbes that divided and produced cell carbon at rates greatly exceeding those previously documented for oligotrophic aquifers. Biogeochemical activity in the aquifer is enhanced due to extensive exchange of organic-matter- and DO-rich surface water with groundwater across the karst landscape. Comparably high rates of cell-specific metabolism and reproduction in the groundwater – some of which exceeded values observed for surface waters – indicate the presence of readily oxidizable and assimilable organic carbon sources. Since labile pools of organic carbon in surface waters would not be expected to persist for the time frames necessary to be transported with the oldest groundwaters, our results indicate a subsurface source of organic matter that may be supplied via a combination of chemoautotrophy, secondary production, and degradation of necromass (e.g., Geesink et al., 2022). An improved understanding of the microbial processes affecting UFA groundwater quality is essential for developing strategies to mitigate anthropic disturbance and manage this vital natural resource under changing climate and land-use regimes. Future studies that decipher the sources of organic matter driving biogeochemical processes in the UFA are necessary to fully explain the relationships we have documented among microbial biomass, physiology, and hydrogeochemistry. Given that anthropogenic alteration of groundwater biogeochemistry and quality is an issue that is not unique to the region of study, our work from the UFA provides an important case study on groundwater microbial communities that may be compared with conditions in different geological and environmental contexts of global karst landscapes.

The DOC concentration data were previously published by Flint et al. (2021). DOC quality data are available at HydroShare: https://doi.org/10.4211/hs.a876020b85d6413f8486c57dc0b0e3bf (Flint, 2023). All other data collected and analyzed in this study are available at https://doi.org/10.4211/hs.e8e4994bb1a740d8bb3fd65acf342cb6 (Barry Sosa, 2024).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-21-3965-2024-supplement.

ABS: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing (original draft), and visualization. MKF: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, and writing (review and editing). JCE: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, and writing (review and editing). JBM: conceptualization, resources, writing (review and editing), supervision, and funding acquisition. BCC: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, resources, writing (original draft), supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

Research at springs in north central Florida was conducted under the Florida Department of Environmental Protection permits 06281812, 03211912, 07092012, 07162112A, and 08122212, and we are indebted to Christine Housel for her assistance with permit acquisition. We thank Patricia Spellman, Robert Sharping, and Jason Gulley for discussions; Quincy Faber for assisting with collecting the ATP data; and Kelenna O. Irving, Madison Tharp, Victoria Cassady, Arianna Insenga, Rachel Pinsky, and Katelyn Palmer for their assistance with fieldwork.

This research has been supported by the University of Florida Biodiversity Institute (seed grant no. 020518, and a graduate student fellowship), and a Fulbright scholarship. Partial support was also provided by the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences at the University of Florida.

This paper was edited by Tyler Cyronak and reviewed by Xiaogang Chen and one anonymous referee.

Allesson, L., Ström, L., and Berggren, M.: Impact of photochemical processing of DOC on the bacterioplankton respiratory quotient in aquatic ecosystems, Geophys. Res. Lett., 43, 7538–7545, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL069621, 2016.

Barry Sosa, A.: Microbial activity and biomass UFA data, HydroShare [data set], https://doi.org/10.4211/hs.e8e4994bb1a740d8bb3fd65acf342cb6, 2024.

Bastviken, D., Cole, J. J., Pace, M. L., and Van de-Bogert, M. C.: Fates of methane from different lake habitats: Connecting whole-lake budgets and CH4 emissions, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 113, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JG000608, 2008.

Benner, R., Opsahl, S., Chin-Leo, G., Richey, J. E., and Forsberg, B. R.: Bacterial carbon metabolism in the Amazon River system, Limnol. Oceanogr., 40, 1262–1270, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1995.40.7.1262, 1995.

Berggren, M., Lapierre, J. F., and Del Giorgio, P. A.: Magnitude and regulation of bacterioplankton respiratory quotient across freshwater environmental gradients, ISME J., 6, 984–993, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.157, 2012.

Brown, A. L., Martin, J. B., Screaton, E. J., Ezell, J. E., Spellman, P., and Gulley, J.: Bank storage in karst aquifers: The impact of temporary intrusion of river water on carbonate dissolution and trace metal mobility, Chem. Geol., 385, 56–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2014.06.015, 2014.

Brown, A. L., Martin, J. B., Kamenov, G. D., Ezell, J. E., Screaton, E. J., Gulley, J., and Spellman, P.: Trace metal cycling in karst aquifers subject to periodic river water intrusion, Chem. Geol., 527, 0–1, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2018.05.020, 2019.

Chin-Leo, G. and Kirchman, D. L.: Estimating bacterial production in marine waters from the simultaneous incorporation of thymidine and leucine, Appl. Environ. Microb., 54, 1934–1939, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.54.8.1934-1939.1988, 1988.

Chin-Leo, G. and Kirchman, D.: Unbalanced growth in natural assemblages of marine bacterioplankton, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 63, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps063001, 1990.

Church, M.: Resource Control of Bacterial Dynamics in the Sea, in: Microbial Ecology of the Oceans, edited by: Kirchman, D. L., https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470281840.ch10, 2008.

Covington, M. D., Martin, J. B., Toran, L. E., Macalady, J. L., Sekhon, N., Sullivan, P. L., García Jr., Á. A., Heffernan, J. B., and Graham, W. D.: Carbonates in the Critical Zone, Earths Future, 11, e2022EF002765, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EF002765, 2023.

Del Giorgio, P. A. and Cole, J. J.: Bacterial growth efficiency in natural aquatic systems, Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst., 29, 503–541, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.29.1.503, 1998.

Denizman, C.: Land use changes and groundwater quality in Florida, Appl. Water Sci., 8, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-018-0776-9, 2018.

Eiler, A., Langenheder, S., Bertilsson, S., and Tranvik, L. J.: Heterotrophic bacterial growth efficiency and community structure at different natural organic carbon concentrations, Appl. Environ. Microb., 69, 3701–3709, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.69.7.3701-3709.2003, 2003.

Eydal, H. S. C. and Pedersen, K.: Use of an ATP assay to determine viable microbial biomass in Fennoscandian Shield groundwater from depths of 3–1000 m, J. Microbiol. Meth., 70, 363–373, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2007.05.012, 2007.

Farnleitner, A. H., Wilhartitz, I., Ryzinska, G., Kirschner, A. K. T., Stadler, H., Burtscher, M. M., Hornek, R., Szewzyk, U., Herndl, G., and Mach, R. L.: Bacterial dynamics in spring water of alpine karst aquifers indicates the presence of stable autochthonous microbial endokarst communities, Environ. Microbiol., 7, 1248–1259, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00810.x, 2005.

Flint, M.: Water Chemistry, Nitrogen and CDOM/FDOM Data from the Santa Fe River Watershed, North-Central Florida, HydroShare [data set], https://doi.org/10.4211/hs.a876020b85d6413f8486c57dc0b0e3bf, 2023.

Flint, M. K., Martin, J. B., Summerall, T. I., Barry-Sosa, A., and Christner, B. C.: Nitrous oxide processing in carbonate karst aquifers, J. Hydrol. (Amst.), 594, 125936, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125936, 2021.

Flint, M. K., Martin, J. B., Oberhelman, A., Janelle, A. J., Black, M., Barry-Sosa, A., and Christner, B.: Hydrologic and Organic Carbon Quality Controls on Nitrous Oxide Dynamics Across a Variably Confined Karst Aquifer, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 128, 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JG007493, 2023.

Florida Springs Institute: Florida Springs Conservation Plan, High Springs, Florida, https://floridaspringsinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Springs-Conservation-Plan-final-draft-FINAL.pdf (last access: 6 September 2024), 2018.

Fuhrman, J. A. and Azam, F.: Bacterioplankton secondary production estimates for coastal waters of British Columbia, Antarctica, and California, Appl. Environ. Microb., 39, 1085–1095, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.39.6.1085-1095.1980, 1980.

Geesink, P., Taubert, M., Jehmlich, N., von Bergen, M., and Küsel, K.: Bacterial Necromass Is Rapidly Metabolized by Heterotrophic Bacteria and Supports Multiple Trophic Levels of the Groundwater Microbiome, Microbiol. Spectr., 10, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.00437-22, 2022.

Giering, S. L. C. and Evans, C.: Overestimation of prokaryotic production by leucine incorporation–and how to avoid it, Limnol. Oceanogr., 67, 726–738, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.12032, 2022.

Gillooly, J. F., Brown, J. H., West, G. B., Savage, V. M., and Charnov, E. L.: Effects of size and temperature on metabolic rate, Science (1979), 293, 2248–2251, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1061967, 2001.

Goldscheider, N., Chen, Z., Auler, A. S., Bakalowicz, M., Broda, S., Drew, D., Hartmann, J., Jiang, G., Moosdorf, N., Stevanovic, Z., and Veni, G.: Global distribution of carbonate rocks and karst water resources, Hydrogeol. J., 28, 1661–1677, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-020-02139-5, 2020.

Gulley, J., Martin, J. B., Screaton, E., and Moore, P. J.: River reversals into karst springs: A model for cave enlargement in eogenetic karst aquifers, Bull. Geol. Soc. Am., 123, 457–467, https://doi.org/10.1130/B30254.1, 2011.

Gulley, J., Martin, J., Spellman, P., Moore, P., and Screaton, E.: Dissolution in a variably confined carbonate platform: Effects of allogenic runoff, hydraulic damming of groundwater inputs, and surface-groundwater exchange at the basin scale, Earth Surf. Proc. Land., 38, 1700–1713, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.3411, 2013.

Harjung, A., Schweichhart, J., Rasch, G., and Griebler, C.: Large-scale study on groundwater dissolved organic matter reveals a strong heterogeneity and a complex microbial footprint, Sci. Total Environ., 854, 158542, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158542, 2023.

Heffernan, J. B., Liebowitz, D. M., Frazer, T. K., Evans, J. M., and Cohen, M. J.: Algal blooms and the nitrogen-enrichment hypothesis in Florida springs: Evidence, alternatives, and adaptive management, Ecol. Appl., 20, 816–829, https://doi.org/10.1890/08-1362.1, 2010.

Henson, W. R., Huang, L., Graham, W. D., and Ogram, A.: Nitrate reduction mechanisms and rates in an unconfined eogenetic karst aquifer in two sites with different redox potential, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 122, 1062–1077, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JG003463, 2017.

Herfort, L., Crump, B. C., Fortunato, C. S., McCue, L. A., Campbell, V., Simon, H. M., Baptista, A. M., and Zuber, P.: Factors affecting the bacterial community composition and heterotrophic production of Columbia River estuarine turbidity maxima, Microbiologyopen, 6, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1002/mbo3.522, 2017.

Hershey, O. S. and Barton, H. A.: The Microbial Diversity of Caves, in: Cave Ecology, edited by: Moldovan, O., Kováč, Ľ., and Halse, S., Ecological Studies, vol. 235, Springer, Cham, 69–90, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98852-8_5, 2018.

Hershey, O. S., Kallmeyer, J., Wallace, A., Barton, M. D., and Barton, H. A.: High microbial diversity despite extremely low biomass in a deep karst aquifer, Front. Microbiol., 9, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02823, 2018.

Hilman, B., Weiner, T., Haran, T., Masiello, C. A., Gao, X., and Angert, A.: The Apparent Respiratory Quotient of Soils and Tree Stems and the Processes That Control It, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 127, e2021JG006676, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JG006676, 2022.

Hofmann, R. and Griebler, C.: DOM and bacterial growth efficiency in oligotrophic groundwater: Absence of priming and co-limitation by organic carbon and phosphorus, Mol. Plant Microbe In., 31, 311–322, https://doi.org/10.3354/ame01862, 2018.

Hornsby, D., Mattson, R., and Mirti, T.: Surfacewater Quality and Biological Annual Report, Live Oak, Florida, https://archives.waterinstitute.ufl.edu/suwannee-hydro-observ/pdf/Surfacewater-Quality-and-Biological-Report-2003.pdf (last access: 6 September 2024), 2004.

Hosen, J. D., McDonough, O. T., Febria, C. M., and Palmer, M. A.: Dissolved organic matter quality and bioavailability changes across an urbanization gradient in headwater streams, Environ. Sci. Technol., 48, 7817–7824, https://doi.org/10.1021/es501422z, 2014.

Jasechko, S. and Perrone, D.: Global groundwater wells at risk of running dry, Science (1979), 372, 418–421, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc2755, 2021.

Jin, J., Zimmerman, Andrew R., Moore, Paul J., and Martin, J. B.: Organic and inorganic carbon dynamics in a karst aquifer: Santa Fe River Sink-Rise system, north Florida, USA, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 340–357, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JG002350, 2014.

Kalhor, K., Ghasemizadeh, R., Rajic, L., and Alshawabkeh, A.: Assessment of groundwater quality and remediation in karst aquifers: A review, Groundw. Sustain. Dev., 8, 104–121, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsd.2018.10.004, 2019.

Karl, D. M.: Cellular nucleotide measurements and applications in microbial ecology, Microbiol. Rev., 44, 739–796, https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.44.4.739-796.1980, 1980.

Karwautz, C., Zhou, Y., Kerros, M. E., Weinbauer, M. G., and Griebler, C.: Bottom-Up Control of the Groundwater Microbial Food-Web in an Alpine Aquifer, Front. Ecol. Evol., 10, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.854228, 2022.

Katz, B. G.: Sources of nitrate contamination and age of water in large karstic springs of Florida, Environ. Geol., 46, 689–706, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-004-1061-9, 2004.

Katz, B. G., Böhlke, J. K., and Hornsby, H. D.: Timescales for nitrate contamination of spring waters, northern Florida, USA, Chem. Geol., 179, 167–186, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2541(01)00321-7, 2001.

Katz, B. G., Sepulveda, A. A., and Verdi, R. J.: Estimating nitrogen loading to ground water and assessing vulnerability to nitrate contamination in a large karstic springs Basin, Florida, J. Am. Water Resour. As., 45, 607–627, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.2009.00309.x, 2009.

Köster, M. and Meyer-Reil, L. A.: Characterization of carbon and microbial biomass pools in shallow water coastal sediments of the southern Baltic Sea (Nordrügensche Bodden), Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 214, 25–41, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps214025, 2001.

Malki, K., Rosario, K., Sawaya, N. A., Székely, A. J., Tisza, M. J., and Breitbart, M.: Prokaryotic and Viral Community Composition of FreshwaterSprings in Florida, USA, Applied and Environmental Science, 11, 1–18, 2020.

Malki, K., Sawaya, N. A., Tisza, M. J., Coutinho, F. H., Rosario, K., Székely, A. J., and Breitbart, M.: Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Prokaryotic and Viral Community Assemblages in a Lotic System (Manatee Springs, Florida), Appl. Environ. Microb., 87, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00646-21, 2021.