the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Community structures and taphonomic controls on benthic foraminiferal community from an Antarctic Fjord (Edisto Inlet, Victoria Land)

Francesca Caridi

Patrizia Giordano

Caterina Morigi

Anna Sabbatini

Leonardo Langone

Benthic foraminiferal assemblages are key indicators for reconstructing past environmental conditions due to their ecological preference and preservation potential. This study investigates the hard-shelled benthic foraminifera of Edisto Inlet; an Antarctic fjord located on the Northern Victoria Land Coast (Ross Sea). The Inlet is characterized by a well-preserved Holocene laminated sedimentary sequence, providing an invaluable tool to reconstruct local and regional environmental changes. Living and fossil assemblages from the upper 5 cm of sediment were analysed across five sites along an inner-to-outer fjord transect to assess their ecological preferences and preservation patterns. Sites located on the inner fjord are characterized by high accumulation rates, low dry densities, fine grain sizes, and elevated content of organic carbon, indicative of high phytodetrital input and anoxic, reducing conditions probably derived by the burial of fresh organic matter. The surface sediments at these sites host low-diversity low-densities living assemblages but are abundant in dead specimens, suggesting substantial mortality events probably linked to post-sea-ice breakup, high organic matter flux to the bottom, and oxygen depletion associated with low current activity. Total assemblages are characterised by calcareous (Globocassidulina biora, G. subglobosa) and agglutinated (Paratrochammina bartrami, Portatrochammina antarctica) taxa, reflecting sluggish circulation along with a high input of fresh organic matter. A sharp decline in calcareous forms points to intense carbonate dissolution caused by the low redox potential within the sediment that develops during the year. In contrast, transitional and outer sites show more diverse and better-preserved assemblages, including Trifarina angulosa, Nodulina dentaliniformis, Reophax scorpiurus and Globocassidulina spp. among others, consistent with stronger bottom currents and more oxygenated conditions of the outer bay in respect to the inner fjord sites. The site located at the fjord mouth reveals distinct fossil faunas, likely shaped by ecological succession and/or dissolution, highlighting the high environmental variability of this setting. Resistant agglutinated species (Pseudobolivina antarctica, Paratrochammina bipolaris, Miliammina arenacea) dominate these areas, underscoring their potential value for paleoenvironmental reconstruction. Comparison with the succession of the palaeocommunity collected in a nearby marine sediment core (TR17-08) suggests recent improvements in bottom conditions and organic matter content, though key taxa have not recovered to Late Holocene (3600–1500 years BP) levels. These findings highlight the sensitivity of benthic foraminiferal communities to sea-ice dynamics, organic matter input, and hydrographic conditions in Antarctic fjord systems.

- Article

(5027 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(752 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

How organisms distribute and what are the underlying causes of their spatial patterns is a long-standing question in ecology. Local studies are crucial to gain insight of the extant ecological patterns that could be lost due to climate change or anthropogenic activities especially in sensitive areas, such as the polar regions (Gutt et al., 2021; Ingels et al., 2012). Antarctica's remoteness and isolation make it an almost pristine environment in respect of the anthropogenic pressure; thus, an ecological characterization of this area might highlight the natural processes acting on the extant community as well as giving a background natural level (baseline) for future monitoring studies.

In this study, we focus on the distribution of the living and recent benthic foraminifera, an important meiofaunal component of all marine ecosystems (Gooday, 1993; Langlet et al., 2023; Nomaki et al., 2008). Benthic foraminifera are marine unicellular eukaryotes capable of forming a mineralized calcite or agglutinated shell (test) that covers the cytoplasm (Sen Gupta, 2003). Dead assemblages of hard-shelled benthic foraminifera communities are especially important for paleoenvironmental studies due to their excellent preservation potential (Gooday, 2003; Murray, 2006). The composition of these communities is influenced by water masses characteristics, the nature and availability of Organic Matter (OM) at the seafloor, and the dissolved oxygen concentration, which makes benthic foraminifera reliable tracers of past marine environmental conditions (Jorissen et al., 1995; Gooday, 2003). In coastal Antarctica, these assemblages have been used to infer past changes in the water circulation pattern, glacial discharge regime, and sea-ice cover making them a valuable tool to gain insight on the connectivity between the cryosphere and the ocean (Kyrmanidou et al., 2018; Li et al., 2000; Majewski et al., 2018; Majewski and Anderson, 2009; Peck et al., 2015). Thus, the ecological preference of the modern foraminiferal community offers key information on the associations between the species and their environmental significance, which is crucial to constrain the past environmental evolution of a region. Furthermore, the comparison with the modern fauna and the dead one is crucial to underpin the taphonomic controls that might hinge on the preservation on these key environmental tracers.

In Antarctica, studies that analysed benthic foraminifera over the continental shelf have focused on the Antarctic Peninsula, along the western sector of the continent, and on the Weddell Sea (Bernasconi et al., 2019; Cornelius and Gooday, 2004; Ishman and Szymcek, 2003; Lehrmann et al., 2025; Mackensen et al., 1990; Majewski et al., 2023). One of the most studied areas are the South Shetland Islands, especially Admiralty Bay on King George Island; a shallow fjord that has been extensively investigated for its benthic foraminiferal content (<200 m water depth) (Majewski, 2010). In the Ross Sea, research was largely carried out on the continental shelf and the southernmost edge of Victoria Land, especially McMurdo Sound and Terra Nova Bay (Fillon, 1974; Gooday et al., 1996; Kellogg et al., 1979; Kennett, 1966; McKnight, 1962; Pflum, 1966; Violanti, 2000).

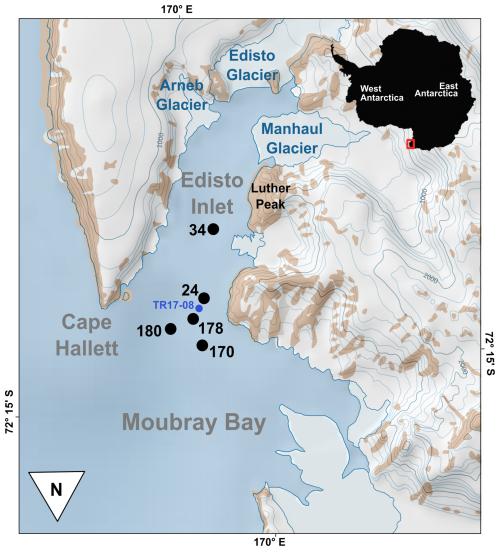

The focus of this study is Edisto Inlet, a little fjord located on the northwestern tip of the Ross Sea, and what could it be a sentinel site to investigate palaeoceanographic changes occurring throughout the Holocene across the Victoria Land Coast (Fig. 1, Battaglia et al., 2024, Galli et al., 2025). In addition, the already studied 3600 year long record of benthic foraminiferal assemblage provides a robust baseline for assess the ecological context of the modern communities by characterizing the changes in relative abundance of key indicator species with known environmental succession that affected the benthic fauna throughout this time interval (Dillon et al., 2022; Galli et al., 2025).

Figure 1Location of the Edisto Inlet (red square) respect to Antarctica and relative location of site of sediment core retrieval inside the inlet (black dots). The previously investigated marine sediment core for the benthic assemblages (TR17-08) is indicated in blue.

Hence, the objective of this study is two-fold: (1) to characterize the environmental context that affect the living and the dead benthic foraminiferal assemblages and (2) to contextualize the modern environmental state of the fjord by comparing recent communities with the succession of different fossil communities reconstructed from sedimentary records.

Environmental Context

Edisto Inlet is narrow fjord located along the northern Victoria Land coast, in the northwestern part of the Ross Sea. The fjord is surrounded by 4 glaciers: Arneb Glacier, Manhaul Glacier, Edisto Glacier and a minor glacier next to Luther Peak (Fig. 1). The Inlet depth is between 400 and 500 m, and it is divided from the Moubray Bay by a sill with a height of about 100 m that shows a steeper flank on the eastern side (Battaglia et al., 2024).

The inlet is characterized by a seasonal cycle of landfast sea-ice: during the austral winter the sea-ice forms and covers the Inlet, and, over the beginning of the warming seasons, it thaws (Tesi et al., 2020). Differences in this seasonal behaviour can have a profound effect on the local benthic fauna: from 2–1.55 kyrs BP, the brittle stars Ophionotus victoriae was thriving, associated with stable interannual cycle of freezing and thawing of the sea-ice cover (Galli et al., 2024). Variability of these environmental patterns are also reflected in lamination structures observed in sediments, characterized by alternating dark and light laminae of different thickness (Galli et al., 2023; Tesi et al., 2020). These sedimentary features have been connected to first sea-ice break up over the spring (dark lamina), and ice-free conditions over the summer (light lamina) (Finocchiaro et al., 2005; Tesi et al., 2020). This is further supported by the presence of two very distinct diatom associations: after the first break-up, diatom of the Fragilariopsis genus blooms, and a dark lamina is deposited. If ice-free conditions persist during the austral summer, reduced vertical mixing may due to stratification caused by the thawing of the sea-ice cover further limit nutrient replenishment in surface waters, favouring the dominance of oligotrophic species like Corethron pennatum thus resulting in the deposition of light-colored laminae (Tesi et al., 2020). However, the Edisto Inlet does not open every year, as sea ice cover can persist even during the summer season (Tesi et al., 2020). As a result of this variability (interannual and seasonal), very few oceanographic studies have been carried out in the area due to its remoteness and the limited accessibility. When investigated, a two-layer stratification was observed, with water masses below the thermocline being saltier than those above (Battaglia et al., 2024). Oceanographic survey on the outer part of the fjord had highlighted the presence of High Salinity Shelf Water (HSSW), a cold, saline and corrosive water mass that forms due to the freezing of the seawater (Caridi et al., 2026). On the inner part, a relatively warmer and less saline water mass is present, while the hydrographical exchange between the Edisto Inlet and Moubray Bay is regulated by tidal waves. A more detailed description of the dynamics that governs Edisto Inlet can be found in Caridi et al. (2026).

High sedimentation rates, typical of fjord embayment, were inferred from age-depth models derived from marine sediment cores as well as sedimentary structures reflecting an expanded Holocene laminated sequence, mostly composed of diatomaceous ooze (Finocchiaro et al., 2005; Battaglia et al., 2024). However, a reduction in the sedimentation of an order of magnitude has been notice across multiple locations starting at 700 years Before Present (yr BP, 0 BP=1950 CE). At that time, the sedimentation rate decreases sharply from 0.7–0.5 cm yr−1 to values of about 0.07–0.04 cm yr−1, strongly suggesting that a less seasonally open fjord with less hydrodynamic conditions characterized the Inlet over the last 700 years (Tesi et al., 2020, Di Roberto et al., 2023).

2.1 Sampling activities

To investigate the benthic foraminiferal assemblages and their distribution related to the environmental parameter in Edisto Inlet, 5 sediment cores were collected with a multicorer Oktopus MC08-12-series (12×∅; 100 mm×610 mm) aboard on the R/V Laura Bassi during the 38th Italian Antarctic Expedition in the framework of the LASAGNE project (Fig. 1, Table 1, and Fig. S1 in the Supplement).

Table 1Core number, site coordinates, depth and date of retrieval. The Sediment Accumulation Rate (SAR) is calculated from the age-depth model reconstructed with the excess activity of 210Pb. Cores in the table are order from the inner to the outermost part: 34 and 24 are located inside of the Inlet; 178 is located at the sill and, lastly, 180 and 170 are located on the outer part of the Inlet (see also Fig. 1).

2.2 Sedimentological analysis

Different analytical approaches were adopted to characterize the sedimentological properties of the uppermost 5 cm of the cores. Redox potential (Eh) was measured directly on board immediately after core recovery using a pre-calibrated Metrohm punch-in pHEh electrode. Measurements were taken with a vertical resolution of 1 cm. Following retrieval, the sediment cores were stored at +4 °C in a refrigerated ISO20 container and transported to Italy for further laboratory analyses. Magnetic susceptibility (MS; ) was measured at 1 cm resolution using an MS2F Surface Point Probe (Bartington Instruments Ltd., UK). Each sediment core was split lengthwise into two halves. One half was sub-sampled at 1 cm intervals, and each slice was divided into multiple aliquots for water content, biogeochemical, and stable isotope analyses. The remaining half was used for non-destructive analyses: it was photographed and X-rayed to identify sedimentary structures, variations in density and texture, and bioturbation features. This archive half was subsequently stored at +4 °C. Dry density (g cm−3) and water content (%) were determined by measuring weight loss after drying sediment samples overnight at 55 °C to constant weight. A particle density of 2.5 g cm−3 was assumed, following the method described by Tesi et al. (2012). An aliquot of each sample was dried, weighed, and wet-sieved at 63 µm to estimate the proportion of sand-sized particles in the sediment. The sand fraction (%) was calculated as the ratio between the dry weight of the >63 µm fraction and the total dry weight (g) of the sample, following the methodology for the dead assemblages (Section Micropaleontological analysis). For organic carbon (OC, wt %) analysis, freeze-dried sediment was homogenized using an agate mortar, acidified with 1.5 M HCl to remove carbonates, and analyzed using a Thermo Fisher FLASH 2000 CHNS/O Elemental Analyzer coupled to a Thermo Fisher Scientific Delta Q isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) (Tesi et al., 2012). The analysis of organic carbon (OC) was performed only for three sites (24, 34, and 180) and after a year from the collection of the sediment cores.

A second freeze-dried and powdered aliquot was used for radionuclide analyses. 210Pb activities were assessed through measurement of its daughter 210Po by alpha spectrometry, using a silicon barrier detector connected to a multichannel analyzer. 210Po activity was assumed to be in secular equilibrium with its grandparent 226Ra, following the method described in Frignani et al. (2005). Sediment accumulation rates (SARs; cm yr−1) were calculated using the Constant Flux : Constant Sedimentation (CF : CS) model based on the decay profile of unsupported 210Pb (half-life: 22.3 years).

2.3 Micropaleontological analysis

Sediment cores for living foraminiferal assemblages were split vertically into two halves. Each half was horizontally sectioned onboard: every 0.5 cm down to 2 cm depth, and then in 1 cm intervals down to 5 cm. The cores used for analysing dead assemblages were stored at −20 °C onboard and later sliced into 1 cm sections down to 5 cm in the laboratory.

In the laboratory, one half of the prepared core was treated with Rose Bengal (RB) and fixed in a 4 % formalin buffer with sodium borate solution for 72 h. After staining, samples were sieved through 125 µm mesh. Residues were kept wet, hand-sorted and counted in water using a binocular microscope. Hard-shelled foraminifera were collected in micropaleontological slides. For what concerns the analysis of the dead assemblages, samples were dried and washed with distilled water with a 63 µm sieve and collected in filter paper. Samples were dried overnight at 40 °C, and further dry sieved at 125 µm. The analysis focuses on the >125 µm fraction, while the 63–125 µm fraction was only collected. If the number of tests in a sample was estimated by sight to be well above 300 tests, the sample was split using a dry Microsplitter and one fraction was counted and picked. The use of the >125 µm enables the comparison with the benthic foraminiferal assemblages to reconstruct paleoenvironmental evolutions of an area since coarser size fractions are commonly employed for that analysis and more suited for the scope of this study (e.g., Majewski et al., 2020; Peck et al., 2015). However, it is important to acknowledge that finer fractions can bear different indicator species then coarser fraction (Lo Giudice Cappelli and Austin, 2019; Ishman and Sperling, 2002; Majewski et al., 2023; Melis and Salvi, 2009).

From both living and fossils analysis, fragments of branching and tubular foraminifera (i.e., Hyperammina and Rhizammina, Plate A1) were collected but not included in the community data analysis because their fragile, easily breakable tests can mislead the correct determination of their occurrence and their abundance.

Taxonomy for hard-shelled benthic foraminifera (agglutinated and calcareous taxa) followed Loeblich and Tappan, (1988) for the genus-level identification, and other reference studies (Anderson, 1975; Capotondi et al., 2020; Galli et al., 2023; Igarashi et al., 2001; Ishman and Szymcek, 2003; Majewski et al., 2005, 2016, 2023; Melis and Salvi, 2009; Sabbatini et al., 2007). Foraminifera were recognised at the species level, when possible. A Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM, Hitachi TM3030plus Scanning Electronic Microscope) was used to gain images of surface texture of specimens and diagnostic details for species recognition. The total density of the specimens was calculated as the number of individuals per 50 cm3 (Area of the core=69.4 cm2). Relative abundances were calculated as the number of individuals of the same species normalized to the total number of benthic foraminiferal tests. Density of planktic foraminifera (expressed in number g−1 of dry sediment) was estimated by the ratio between the total number of tests and the total dry weight.

2.4 Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were conducted in the R enviroment (R Core Team, 2024). Figures and plots were computed using the package ggplot2 (Wickham, 2011). Correlations between the environmental variables were assessed using the function ggcorrplot from the ggcorrplot package (Kassambra, 2022). All the code used to compute the figure and the statistical analysis is reported in the Supplement.

To compare the results from living assemblages with the fossil ones, the assemblage composition of the first 2 centimetres was merged as a 1 cm thick sample to resemble the sample step of 1 cm of the dead assemblage.

To understand the ecological gradient that affected the communities, a non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (nMDS) was computed using Wisconsin transformed relative abundances of species that showed a maximum relative abundances>5 % and appeared in at least two samples, with a Bray–Curtis distance (function monoMDS in the package vegan; Oksanen et al., 2024). nMDS is conservative in respect of the dissimilarity between each sample, making it easier to detect the presence of ecological gradients (Kruskal, 1964; Prentice, 1977). In addition, convex hulls (polygons) were used to investigate the relationship between each station using the function chull.

Lastly, for comparing different paleocommunities with the recent ones, the relative abundance of selected species of different periods were pairwise compared using a non-parametric wilcoxon-test using the function geom_pwc of the scales package (Wicham et al., 2025). A significant p-value threshold of 0.05 was used to reject the null hypothesis of no differences between the groups. The data used for the comparison are those of the TR17-08 (Galli et al., 2025), while, for the core selected, only the assemblages at sites 24 and 34 were used because of the vicinity from the sediment core (Fig. 1).

3.1 Geochemical characteristics of the sediments

The Sediment Accumulation Rate (SAR) derived from the 210Pb excess activity is higher at sites 24 and 178 than the one characterizing the outer sites (170, 180) (Table 1 and Fig. 2a). Core 34 did not yield a usable profile to compute the age-depth model (Fig. S2).

Figure 2Sedimentological characteristics of the sediment cores retrieved in Edisto Inlet. (a) Age-depth model derived from the 210Pb excess activity for every core collected in the sites. The core 34 yield a not usable profile, thus it is not plotted (Fig. S1). The dashed horizontal black line highlights the upper 5 cm used in this study, while the color-coded vertical dashed line highlights how much do the upper section spans time (in yr CE). (b) Sedimentological, geochemical characteristics measured on the uppermost 5 cm, along with planktic foraminiferal densities, retrieved from the fossil assemblage. MS=Magnetic Susceptibility; Eh=Redox potential; OC=Organic Carbon. (c) Pearson's relationship between the features of panel (b). The strength of the relationship is indicated by both the labels inside the square and by the color: Red color=positive relationship, Blue=negative relationship; White=no significant relationship.

Samples collected in the inner fjord (sites 34 and 24) are characterized by low dry density, low magnetic susceptibility (MS), a low sand content and a high-water content (Fig. 2b). By contrast, sites on the outer part of the fjord, namely 170 and 180, are characterized by the opposite trend: high dry densities as well as a high MS and sand content, along with a low water content (Fig. 2b). Site 178, located at the fjord mouth, shows a mixed signal between the geochemical parameters at the inner and outer sites (Fig. 2b). Site 34 has the most negative redox potential (Eh) values, while sites 178, 170 and 180 show a similar reduction pattern down core with the presence of positive Eh values only at the most surficial layer (Fig. 2b). Site 24 has positive Eh values throughout, except for the deepest interval (Fig. 2b).

Since this study focuses on the benthic foraminiferal distribution, planktic foraminiferal tests (only of Neogloboquadrina pachyderma) are used as indicator for primary productivity regimes and/or open water conditions. In the surface samples, sites 34 and 24 are characterised by the highest concentration of planktic test, while outer stations are characterised by the almost complete absence of the latter (Fig. 2b).

Positive relationship between the dry densities, MS, sand content, Eh, are observed, while the water is negatively with every other parameter, except with the planktic foraminifera (Fig. 2c). The only non-significant relationship is between the Eh and the planktic foraminifera content.

3.2 Benthic foraminiferal fauna from Edisto Inlet

A total of 49 species were recognised in the living (stained) assemblages with a total 1589 counted tests, with the first half centimetre from site 170 holding most specimens (496 specimens). Across the dead assemblages, 55 species were identified, and 5639 tests were counted, with the first centimetre of site 170 holding a total of 796 tests. Across all the investigated site, only one planktic species, Neogloboquadrina pachyderma was found.

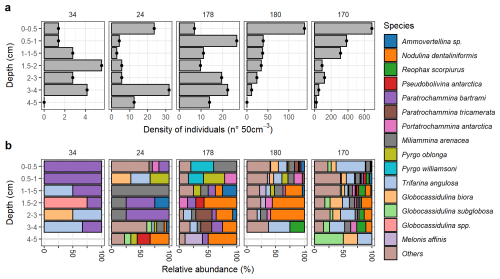

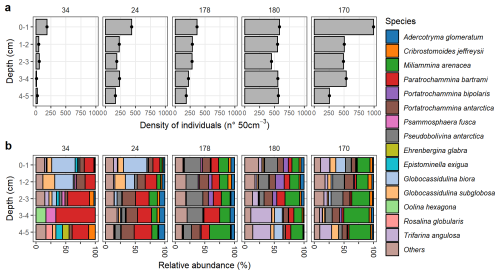

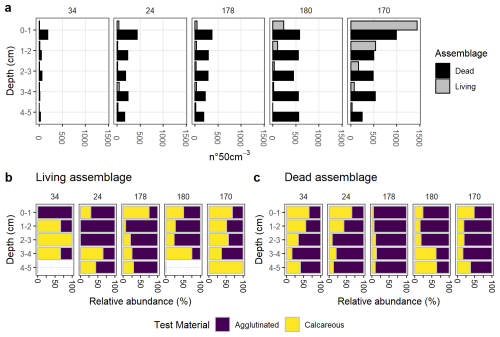

Total densities and community composition of the most common species are reported in Figs. 3 and 4, while a list of all the benthic species identified is presented in the Supplement, along with the counted specimens.

Figure 3Living (Rose-Bengal stained) benthic foraminifera community in Edisto Inlet. (a) Total densities () of stained benthic foraminifera test counted. The x axis is scaled differently for each station. (b) Assemblage composition of the species that appears more than 20 %. A threshold of 20 % was used because of the low number of individuals at sites 34, 24 and 178 (). Sites names are reported on top of each plot and are arranged from the innermost (34) to the outermost site (180). Species are reported in alphabetical order.

Figure 4Dead benthic foraminiferal community in Edisto Inlet. (a) Total densities () of foraminifera test counted in the dead assemblage. (b) Assemblage composition of the species that appears more than 10 % and at least in one station. Species are reported in alphabetical order.

A comparison between the living and dead assemblage is also reported in Fig. 5, highlighting the differences in the total densities between the two assemblages, and the different content of the agglutinated and calcareous test.

Figure 5Comparison between the living and dead benthic foraminifera assemblage. (a) Total densities () of the living (grey) and dead (black) assemblages. To compare the total densities of the living with the one of the dead, samples that were sliced at 0.5 cm were merged. (b) Relative abundances of calcareous (yellow) and agglutinated (dark purple) benthic foraminifera of the living (b) and dead assemblage (c) assemblage.

Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) photos of selected species are presented in the Appendix section.

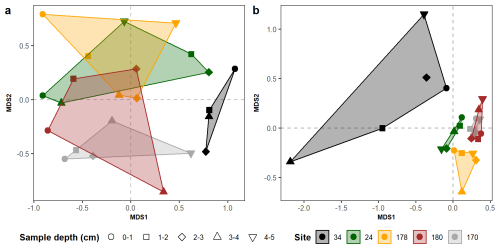

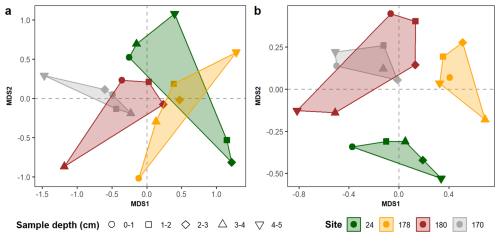

3.3 Multivariate analysis

The 2-dimension nMDS models are characterised by stress values <0.2 (Figs. 6 and 7), indicating that the ecological gradients in Edisto Inlet are well represented in a two-dimensional space (Dexter et al., 2018). The living benthic foraminiferal fauna shows a higher degree of overlap among sites than the dead assemblage (Fig. 6). Notably, site 34 appears as an outlier in both assemblages, so a second nMDS was computed excluding the latter (Fig. 7).

Figure 62-dimension nMDS models computed on the community composition of the living (a) and the dead (b) benthic assemblages. Both models show Site 34 as an outlier. In the legend, the sites are reported from the innermost to the outermost part of the fjord.

Figure 72-dimension nMDS models computed on the community composition of the living (a) and the dead (b) benthic assemblages computed without site 34. Notice the change in the community structure of site 178: in the living assemblages overlaps sites 24 (a), while on the fossil assemblage mostly overlaps site 180 (b).

After removing site 34, the living assemblage shows more overlapping features than the dead one (Fig. 7). Of note, the relative location of the polygon of site 178 (the site located at the sill, Fig. 1) changes quite substantially: in the living assemblage it overlaps site 24 (Fig. 7a), while on the dead ones it is completely detached from it (Fig. 7b). Lastly, the dead assemblages at site 24 are much more distant from the outer and entrance site than the living one (Fig. 7), being the only site showing only negative MDS2 values (Fig. 7b).

3.4 Palaeocommunities comparison

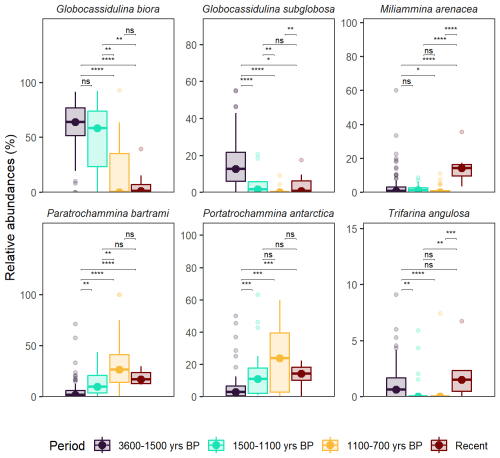

The palaeocommunities analysed from the TR17-08 were divided according to the environmental phases reported by Galli et al. (2025) with emphasize on the fjord-like behaviour (3600–1500 yr BP, total number of samples n=99) Transitional warming phase (1500–1100 yr BP, n=21), Cooling phase (1100–700 yr BP, n=20). The data used from sites 24 and 178 are considered “recent” because they span a relative long period as shown in Fig. 2a (n=10). All the pairwise comparison and significance are reported in Fig. 8. For simplicity, we comment only the comparison with the recent period. All the species relative abundances are significantly different from the 3600–1500 yr BP period except for Trifarina angulosa. Similarly, significant differences are present from the 1500–1100 period, except for Globocassidulina sublgobosa, Paratrochammina bartrami and Portatrochammina antartica. Content of G. biora, P. bartrami, P. antarctica shows no significant difference from the 1100–700 yr BP period, G. subglobosa, Miliammina arenacea and T. angulosa, are characterized by an increase in their relative abundances in respect to the latter.

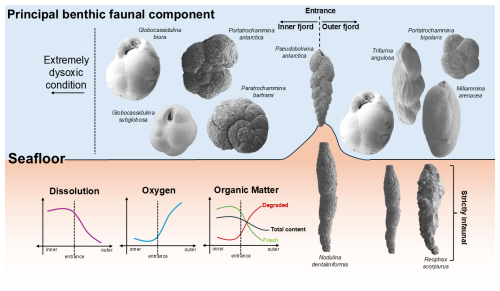

4.1 Environmental gradient across the fjord transects

From the sedimentological and geochemical analysis, it is evident that the fjord is characterized by an extremely well-defined gradient of benthic environmental conditions going from the inner to the outermost part (Figs. 2 and 9). The main factor that shapes this pattern might be related to the amount of Organic Matter (OM) that arrives at the bottom probably exerting a first order control on the amount of dissolved oxygen that is present at the bottom. Low MS, reduced sand content, high OC at the inner sites support this interpretation, along with the extremely low Eh values found at the innermost sites (Fig. 2b, Arndt et al., 2013; Hoogakker et al., 2024; LaRowe et al., 2020). Furthermore, the extremely low values of Eh at site 34, in conjunction with the elevated OC content, and the lower dry density, reflecting a high porosity, (Fig. 2b) suggest that the OM delivered to the bottom is efficiently buried within the sediments, generating a strong redox potential and a very harsh environment within the sediments (Hoogakker et al., 2024). In addition, higher sedimentation rates characterize the innermost sites and can be attributed to the extreme seasonality that this fjord experiences (Table 1). In the Edisto Inlet, the presence of a landfast sea-ice cover that forms and thaws over the summer have been regarded as the first order control on depositional signal, since most of the primary productivity happens after the sea-ice break up (Finocchiaro et al., 2005; Tesi et al., 2020). This can be seen by the higher concentrations of planktic foraminifera in the upper first centimetre on the inner stations, indicating a high surface productivity (Fig. 2b). The presence of mostly diatoms derived OM on the inner part could enhance the dissolution potential on the innermost part of the fjord and, along with the almost completely absence of a bottom current activity in the fjord might enhance the amount of OM present in the sediment (Arndt et al., 2013; Battaglia et al., 2024).

On the other hand, sites located outside of the fjord are characterized by a complete opposite condition from the ones that characterized the inner fjord (Fig. 2b). Despite being lower, OC values on the outer stations are still quite high (>0.3), implying that a significant amount of OM is still delivered to the bottom. However, the presence of higher values of Eh, higher MS, and higher sand content suggests the presence of a more dynamical regime and less dysoxic conditions, while also implying an increase in the detrital material arriving at the bottom respect to the inner site (Fig. 9).

Figure 9Conceptual cartoon of the modern Edisto Inlet benthic foraminiferal fauna and the major environmental factors (Dissolution, Oxygen, Organic Matter) that affects the benthic community and how they are distributed along the fjord transect, from innermost to outermost part. Species that have been found only below 1 cm were considered as strictly infaunal and are depicted inside the sediments. For a more detailed discussion readers are referred to the Sect. 4.2. SEM photos of selected foraminifera are not in scale.

Site 178, situated near the entrance of the fjord, bridges the gap between the innermost and the outermost conditions, showing values comprising between these two endmembers (Figs. 2b and 9).

Hence, it is reasonable to hypothesize that most of the benthic conditions in the Edisto Inlet are shaped by the type of OM that arrives at the seafloor and how much of this fresh OM is buried into sediments which is highly regulated by the bottom hydrographic conditions. These environmental conditions are probably exerting a first order control on the dissolved oxygen present at the sediment-water interface and deeper in the sediments (Fig. 9).

4.2 Benthic foraminiferal communities and their relationship with the environment

To better frame the differences in the benthic foraminiferal fauna that shapes the living assemblages and what control the preservation potential of the hard-shelled fauna, it is possible to define three important habitats within the studied sites by comparing it with the environmental gradients: innermost part of the fjord (34, 24), the entrance (178) and the outermost bay (170, 180) (Fig. 9). It is, however, important to stress that the living RB-stained assemblage represents an estimation of the living community, as well as snapshots of the whole benthic foraminifera community, while the dead community represents a time averaged community, affected by both environmental and taphonomical controls on their compositions (Van Der Zwaan et al., 1999). Among taphonomical controls on the community structure, the different sedimentation rates found in the inner fjord and its outer part could influence the sharp contrast of the total densities of specimens between these two environmental opposites (Fig. 2a). Dead assemblages located inside the fjord could experience a substantial decrease in the density of individuals, while, on the outer bay, sediment winnowing could remove the finer (<63 µm) sediment fraction, effectively concentrating the specimens within less sediment. Hence, this taphonomical effect could be a concurring factor in explain the stark contrast between the assemblages found in this area (Fig. 5b). However, the steep gradient highlighted by geochemical analysis and the community structure (Figs. 2 and 4) points out to a more complex and substantial control affecting the dead assemblages.

4.2.1 Inner fjord (sites 34 and 24)

The living community at this site shows extremely low abundances and low diversity, indicative of harsh environmental conditions affecting the populations (Fig. 3). However, a very sharp contrast between the amount of dead test and the presence of very high dissolution conditions going down core is testified by a sharp decay of calcareous test going down cores probably caused by the high content of Organic Matter (OM, Fig. 5). The presence of these extreme conditions can be further inferred from the nMDS models, both showing that the community at the inner sites are far more diverse than the one at the entrance and the one found on the outer bay (Figs. 6 and 7). This is evident for site 34 (Figs. 6 and 7a). In the inner sites, the dead community is dominated by the presence of four major component: the calcareous Globocassidulina biora and Globocassidulina subglobosa, while the agglutinated fauna is mainly composed by Paratrochammina bartrami and Portatrochammina antarctica (Fig. 9). The latter two are indicative of locations with high carbonate dissolution, and elevated OM accumulation on the seafloor, and, because of their fragile test material, to sluggish circulation regimes, all of which are consistent with the environmental features derived from the sedimentological properties (Fig. 9, Anderson, 1975; Capotondi et al., 2020; Majewski, 2010; Majewski et al., 2023; Majewski and Anderson, 2009; Melis and Salvi, 2009; Violanti, 2000). Anoxic (or suboxic) conditions can lead to the death of most benthic organisms, including foraminifera, with only few opportunistic taxa capable of surviving in low-oxygen environments, such as G. biora and G. subglobosa (Gooday, 2003; Levin et al., 2009). Thus, the presence of these species, known for their tolerance to low oxygen condition, opportunistic behaviour and rapid reproduction, supports the hypothesis of oxygen-depleted bottom conditions while highlighting the influence of organic-rich, poorly oxygenated microenvironments affecting the living foraminiferal community structure (Fig. 4b). The presence in the fossil assemblage of the phytodetritivorous species Epistominella exigua further corroborates this view of enhanced OM fluxes, that might be associated with the seasonal break-up of the sea-ice cover (Mackensen et al., 1990; Smart et al., 1994; Gooday and Rathburn, 1999; Lehrmann et al., 2025). However, the preservation of this faunal component seems to be severely limited by the high dissolution conditions that develops deeper in the sediments and probably later in the year (Figs. 5 and 9). By these considerations, it is plausible that these discrepancies between the living and dead assemblages over the innermost site arised due to a combination of substantial mortality events following the sea-ice break up and taphonomic controls on the dead assemblage. The date of retrieval of the core was late in the austral summer (Table 1), well after the first break-up of the sea-ice, aligning with thisintepretation.

Thus, the presence of relatively high fluxes of OM could exert a double control on the population. First, the break-up of the sea-ice cover enriches the seafloor of OM due to enhanced primary productivity because of the light availability. Afterwards, the absence of a strong circulation regime can increase the remineralization and oxidation potential of this food bank, providing a suitable explanation of the strong differences between the living and dead assemblages (Smith et al., 2015). While this makes the foraminiferal prone to dissolution, it also stresses the importance of considering this fjord as an efficient hotspot of OC burial (Smith et al., 2015).

4.2.2 Entrance part (site 178)

In terms of geochemical and sedimentological parameters, this site is transitional between the innermost and the outermost station (Figs. 2b and 9). Interestingly, the living benthic foraminiferal community is characterized by being most similar to the sites that are inside of the fjord, in both the total number of specimens and community structures (Figs. 3 and 7). However, in the dead assemblages the separation of the entrace from the inner fjord sites is evident (Figs. 4 and 7b). On the surface, the living community is characterized by calcareous miliolid of the epifaunal genus Pyrgo (Pyrgo oblonga and P. williamsoni) and by the presence of the agglutinated miliolid Miliammina arenacea. Downcore, the community is replenished by the agglutinated uniserial Nodulina dentaliniformis,and the trochospiral Paratrochammina tricamerata and P. bartrami (Fig. 3b). On the other hand, the fossils community is characterized by a strikingly similar composition throughout, mostly composed of Pseudobolivina antarctica, Potratrochammina antarctica, Miliammina arenacea and Paratrochammina bartrami, all of which are agglutinated forms (Fig. 4b). While dissolution conditions might affect the dead assemblage, as evidenced by the discrepancies between the content of calcareous tests in the first cm, the community is dominated by agglutinated forms in both living and dead assemblages going with depth in the cores (Fig. 5). The high content of Pseudobolivina antarctica in the dead assemblage is particularly remarkable since, in the living one, it is found in only one sample at a depth of 3 cm (Fig. 3b), hinting to a different ecological preference rather than an increase in its concentration produced by dissolution alone. Site 178 is located at mouth of the fjord, where most of the variability in both oceanographical and sedimentological parameters happens in enclosed basin. Due to water mass exchange with the outer bay and because landfast sea-ice is more prone to be broken because of the increasing distance from its anchored coastal part, the area is affected by strong and complex environmental dynamics (Cottier et al., 2010; Fraser et al., 2023; Howe et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2022). This is further supported by the highest number of tubular fragments found at site 178, indicating a strong hydrodynamical regime (Majewski et al., 2023, Fig. S3). Hence, while dissolution cannot be fully ruled out as a major component affecting the preservation potential at this site, the presence of a different ecological succession of benthic fauna over the year can also be seen as concurring factor in shaping the community structure (Alve, 1999). However, more studies need to be done to fully understand the possible effect of deep and intermediate water and frame these peculiar discrepancies over the entrance site where the interplay between the inner fjord water masses and outer one is stronger.

As to what these species may indicates, they align with the “mixture” of environmental conditions that the microhabitat at site 178 experiences (Figs. 2 and 9). The presence of miliolids in the first cm of the living assemblages, as well as the presence of strictly infaunal species (N. dentaliniformis) throughout the core are indicative of more oxygen, more salinity variation but with conspicuous content of labile OM that is degraded by enhanced microbial activity (Kender and Kaminski, 2017; Lukina, 2001; Majewski, 2005). These environmental signals seem to be preserved in the dead assemblage even if the indicator species changes: Pseudobolivina antarctica has been found in OM-enriched-mud deposits, while M. arenacea is indicative of oxic to suboxic conditions and/or dissolution conditions that could derive from saline and cold water masses (Capotondi et al., 2018; Lehrmann et al., 2025; Majewski et al., 2023; Rodrigues et al., 2013; Violanti, 2000; Ward et al., 1987). Presence of trochospiral forms such as P. bartrami and Portatrochammina antarctica further supports the high OM content flux at the bottom (Majewski et al., 2023).

4.2.3 Outer Bay (site 170 and 180)

The outer sites constitute the other environmental end member of the analysed transect (Figs. 2 and 9). An ameliorant of the microhabitat conditions respect to the inner station can be inferred by the increased number of specimens (Fig. 3a). Moreover, going deeper into the core, the dead assemblage is characterized by an increase in the calcareous component of the fauna, thus indicating a reduction in the dissolution conditions (Fig. 5c). The presence of a more dynamical and less severe bottom conditions is reflected in both the living and dead assemblages (Figs. 3 and 4). The living assemblage is mainly composed by Globocassidulina biora, Globocassidulina subglobosa, Trifarina angulosa and Miliammina arenacea; downcore appearances of Nodulina dentaliniformis and Reophax scorpiurus are also visible (Fig. 3b). While the presence of G. biora and G. subglobosa can be indicative of the still high, but lower, OC content (>0.3, Fig. 2b, Majewski, 2005, 2010; Majewski et al., 2019), the presence of T. angulosa aligns with the presence of coarser grain size, that can be indicative of higher hydrodynamical conditions at the bottom (Melis and Salvi, 2009; Murray and Pudsey, 2004; Violanti, 2000). Moreover, the stable presence of both T. angulosa and G. biora downcore suggests a facultative infaunal behaviour of these taxa.

The higher content of M. arenacea at the outer sites might be caused by an increase in the oxygen content rather than dissolution, and it can also be ascribed by the presence of HSSW at these sites (Lehrmann et al., 2025). In addition, the downcore presence the deep infaunal species N. dentaliniformis and R. scorpiurus further corroborates this view, since both have been associated with presence of labile OM and are resistant to change in salinity, suggesting higher hydrodynamic conditions (Kender and Kaminski, 2017). Similarly, the dead community is characterized by the prominent presence of G. biora, G. subglobosa and T. angulosa, with a higher component of the agglutinated specimens (Fig. 4b). M. arenacea, is still present but its more prominent, while Pseudobolivina antarctica along with Portatrochammina antarctica and P. bipolaris become much more common going throughout (Fig. 4b). However, it is worth noting that the two deep infaual species (N. dentaliniformis and R. scorpiurus) do not constitute a significant proportion of this assemblage at outer sites, probably because of the elongated test being susceptible to easily break (Majewski, 2005; Majewski and Pawlowski, 2010). Still, the dead assemblage at these outer sites is closely related to the living one, suggesting high carbonate preservation on the outer bay and less, but still high, OM content.

4.3 Comparison with the paleocommunities from the Late Holocene

In coastal Antarctica, the presence of sea-ice affects almost every aspect of the water column (Fraser et al., 2023). Generally, after the first sea-ice break-up, light availability increases and this, along with the presence of a nutrient input, translates into higher surface productivity as well as increased OM fluxes to the seafloor (Arrigo and van Dijken, 2004; Misic et al., 2024). In the Edisto Inlet, paleoenvironmental reconstruction from the nearby piston core TR17-08 using benthic foraminiferal communities had highlighted the role of fast-ice in shaping the benthic community (Galli et al., 2023, 2024, 2025). Along the transect analysed in this study, the benthic foraminiferal community in Edisto are affected by the sedimentation rate, the quantity of OM at the bottom and the hydrographic regime (Fig. 9), all of which are closely related to the presence of a seasonal cycle of freezing and thawing of the sea-ice cover (Fraser et al., 2012, 2023). Similar to the communities found in the Arctic, this suggests that the benthic foraminiferal community in Antarctica, even at deep sites (>200 m b.s.l.), are sensitive to different seasonal sea-ice conditions (Fossile et al., 2020; Lohrer et al., 2013; Seidenkrantz, 2013).

Hence, by comparing the composed record of the fossil assemblage at the two nearest sites (24 and 178) with the faunal succession collected along the core TR17-08, it might be possible to give a broader and more general context of the modern environmental settings derived from the benthic foraminifera information. This comparison can be done because the core collected at sites 24 and 178 spans ca. 60 years (Fig. 2a) making the dead assemblages collected over the 5 cm a time frame long enough to be comparable to a longer baseline, in this case the last 3600 yr BP. Although Galli et al. (2025) used a size fraction >150 µm, while this study focussed on the >125 µm, it is unlikely that the 25 µm difference have significantly influenced the differences between the communities (Fig. 8, Weinkauf and Milker, 2018).

Briefly, a typical Antarctic fjord environment was hypothesized between 3600–1500 yr BP because of the dominance of Globocassidulina biora, G. subglobosa, and the presence of Portatrochammina antarctica and Paratrochammina bartrami, which are commonly found in other inlet and enclosed basins across different Antarctic coastal sites (Galli et al., 2025; Majewski, 2010; Rodrigues et al., 2013). From 1500–1100 yr BP, a transitional period with prolonged summer ice-free conditions along with an increase in the glacial discharge closed the fjord from the general circulation. From 1100–700 a cooling period, culminating with the transition from a calcareous dominated fauna to an agglutinated dominated one was detected (Galli et al., 2023). The latter was followed by another 700 years interval of very low benthic foraminiferal abundances, probably related to a substantial increase in the sea-ice cover period (Galli et al., 2023; Di Roberto et al., 2023; Tesi et al., 2020). In addition to G. biora, G. subglobosa, P. antarctica and P. batrami, we also compare the content of Trifarina angulosa as an indicator of benthic hydrodynamic conditions and Miliammina arenacea to address the dissolution and/or suboxic to oxic conditions at the seafloor (Fig. 8). As evidenced by the fjord-like community, the fjord has not fully recovered to the late Holocene state (3600–1500 yr BP), and the benthic fauna is similar to the one from the cold transitional state, a period in which the foraminiferal community was severely stressed (Galli et al., 2025). Only G. subglobosa increased significantly in respect to the cooling transitional periods, thus suggesting an increase in the OM content at the bottom, probably due an increase in the seasonal regime of the sea-ice recover and more warmer conditions, like the ones characterizing the 1500–1100 yr BP interval (Galli et al., 2023, 2025). Interestingly, there is an increase in the T. angulosa content that suggest increase of the hydrodynamical bottom conditions, which aligns with the significant increase of M. arenacea respect to both transitional periods (Fig. 8). M. arenacea content is also similar the one derived from the 3600–2700 yr BP, which corresponds to a period in which the presence of higher salinity water masses (as the HSSW) was more prominent inside the Inlet (in Fig. 9 this is highlighted by the presence of outlier points, Galli et al., 2025). Thus, it is possible that benthic foraminiferal community that inhabits the fjord today, has yet to recovered from the two highly stressful period (1500–1100 yr BP; 1100–700 yr BP), but an ameliorant of the bottom conditions can be hypothesized by the changes in the major component of the benthic foraminiferal fauna.

By comparing the geochemical properties and the benthic foraminiferal fauna of the upper 5 cm of five sediment cores retrieved in Edisto Inlet, it was possible to understand the main distributional pattern of the benthic meiofaunal components within this Antarctic fjord and understand what drives their ecological preference and their preservation potential. Two distinct environmental settings were identified, the inner part of the fjord (sites 34 and 24) and the outer fjord (sites 170, 180). The entrance site (178) showed mixed properties between these two endmembers. Inner stations were characterized by low dry densities, low MS, high sediment accumulation rates, low Eh and lower sand content, all which are indicative of oxygen-depleted sediments with a high fresh OM content efficiently buried within the sediments. On the other hand, outer stations are characterized by low sedimentation rates, high dry densities and lower organic carbon content, indicative of a higher oxygen content at the bottom associated with less OM (but still a high overall content of the latter) probably due to a higher hydrodynamical regime at the bottom.

Both living and dead assemblages of the benthic foraminiferal community reflects these differences. The Rose-Bengal stained “living” assemblage on the inner part of the fjord is characterized by the lowest number of individuals and a higher number of dead, suggesting the presence of substantial mortality events caused by the cascading effect of sea-ice break up: the increase in primary productivity, and the associated export of OM to the seafloor. Due to the onset of a stressful environment after the first break up, a sluggish circulation regime in concomitance with high fluxes of OM, might severely deplete the water column of oxygen and increase the dissolution condition at the bottom. Inner stations are also characterized by a release of these stressful environmental conditions going near the fjord-head. The hard-shelled benthic foraminifera community is mainly composed by Globocassidulina biora and Globocassidulina subglobosa along with the agglutinated species such as Paratrochammina bartrami and Portatrochammina antarctica, resembling a high OM setting with sluggish circulation regimes, aligning with the geochemical parameters. In addition, the overall decrease of calcareous forms in the fossil assemblage that characterized the deeper parts of the cores suggest high dissolution conditions.

At the sill, the dominant faunal component of the first centimeter are miliolids, while, going deeper into the sediments, deep infaunal species such as Nodulina dentaliniformis appear, indicating a higher hydrographic regime, in conjunction with a less oxygen-depleted environment associated with less OM content. The dead assemblage is highly dissimilar from the living one, with the prominent presence of Pseudobolivina antarctica and with a lesser degree, Miliammina arenacea. While dissolution cannot be fully ruled out as an explanation of these living-dead discrepancy, it is possible that this agglutinated community might reflects different period of an ecological succession that develops later in the year and with less OM availability.

In the outer fjord, living and dead assemblages are more similar. Both assemblages are constituted by Trifarina angulosa, indicating higher bottom current activity, while the presence of the infaunal Nodulina dentaliniformis and Reophax scorpiurus resembles the presence of labile OM at the seafloor. At the outer stations, calcareous species such as Trifarina angulosa and Globocassidulina spp., along with the agglutinated M. arenacea align with coarser grain size that reflects these higher hydrodynamic conditions and a general higher oxygen content compared to the inner part.

Lastly, by comparing the relative abudances from the nearby piston cores TR17-08 of G. biora, G. subglobosa, P. batrami, Portatrochammina antarctica, T. angulosa and M. arenacea with the ones derived from the nearby sites (24 and 178) it was possible to determine a more general context of this benthic community: while the fjord-like community has yet to be recover to Late Holocene values, the presence of a significant increase in T. angulosa and M. arenacea from the 1500–1100 and 1100–700 yr BP interval suggest an ameliorant from the harsh and stressful conditions that developed during that cooling period.

Plate A1(1a, b) Rhabdammina sp. 1; (2a, b) Rhabdammina sp. (2; 3) Nodulina dentaliniformis; (4) Reophax scorpiurus; (5) Reophax spiculifer; (6) Agglutinated tubular fragment; (7) Lagenammina difflugiformis; (8) Lagenammina sp. (1; 9) Lagenammina sp. (2; 10) Pseudobolivina antarctica; (11a, b) Spiroplectammina biformis; (12a, b) Eggerelloides sp. (13a, b) Psammosphera fusca; (14) Rhumblerella sp.; (15) Ammovertillina sp.; (16) Ammodiscus incertus.

Plate A2(1a–c) Recurvoides contortus; (2) Paratrochammina tricamerata; (3) Paratrochammina bartrami; (4) Portatrochammina antarctica; (5) Portatrochammina bipolaris; (6) Cribrostomoides jeffreysii; (7) Adercotryma glomeratum; (8a, b) Pyrgo elongata; (9) Miliammina arenacea.

Plate A3(1) Hyalinometrion gracilium; (2a, b) Lagena substriata; (3) Ehrenbergina glabra; (4) Parafissurina sp.; (5) Parafissurina fusiformis; (6) Stainforthia concava; (7a, b) Fursenkoina subacuta; (8a, b) Bolivinellina pseudopunctata; (9a–d); Trifarina angulosa; 10(a–c), Neogloboquadrina pachyderma.

All the data and codes used for this study are reported in the Supplement of the article.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-23-1137-2026-supplement.

GG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing (original draft preparation); FC and PG: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing (review and editing); CM and AS: Investigation, Validation, Writing (review and editing); LL: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing (review and editing).

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We sincerely thank the crew of R/V Laura Bassi and the OGS technicians for their support during the sampling activities carried out as part of Leg 2 of the PNRA XXXVIII Antarctic Expedition. Special thanks go to Riccardo Scipinotti for his invaluable logistical assistance. This work is a contribution to the PNRA19_00069 LASAGNE project. We also acknowledge Laura Bellentani and Alessandro Sartini for their invaluable help in the sample preparations.

This research has been supported by the Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca (grant no. PNRA19_00069).

The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by the Max Planck Society.

This paper was edited by Niels de Winter and reviewed by R. Mark Leckie and Maria Pia Nardelli.

Alve, E.: Colonization of new habitats by benthic foraminifera: a review, Earth. Sci. Rev., 46, 167–185, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-8252(99)00016-1, 1999.

Anderson, J. B.: Ecology and Distribution of Foraminifera in the Weddel Sea of Antarctica, Micropaleontology, 21, 69–96, https://doi.org/10.2307/1485156, 1975.

Arndt, S., Jørgensen, B. B., LaRowe, D. E., Middelburg, J. J., Pancost, R. D., and Regnier, P.: Quantifying the degradation of organic matter in marine sediments: A review and synthesis, Earth-Sci. Rev., 123, 53–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.02.008, 2013.

Arrigo, K. R. and van Dijken, G. L.: Annual changes in sea-ice, chlorophyll a, and primary production in the Ross Sea, Antarctica, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 51, 117–138, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2003.04.003, 2004.

Battaglia, F., De Santis, L., Baradello, L., Colizza, E., Rebesco, M., Kovacevic, V., Ursella, L., Bensi, M., Accettella, D., Morelli, D., Corradi, N., Falco, P., Krauzig, N., Colleoni, F., Gordini, E., Caburlotto, A., Langone, L., and Finocchiaro, F.: The discovery of the southernmost ultra-high-resolution Holocene paleoclimate sedimentary record in Antarctica, Mar. Geol., 467, 107189, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2023.107189, 2024.

Bernasconi, E., Cusminsky, G., and Gordillo, S.: Distribution of foraminifera from South Shetland Islands (Antarctic): Ecology and taphonomy, Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci., 29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsma.2019.100653, 2019.

Capotondi, L., Bergami, C., Giglio, F., Langone, L., and Ravaioli, M.: Benthic foraminifera distribution in the Ross Sea (Antarctica) and its relationship to oceanography, Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana, 57, 187–202, https://doi.org/10.4435/BSPI.2018.12, 2018.

Capotondi, L., Bonomo, S., Budillon, G., Giordano, P., and Langone, L.: Living and dead benthic foraminiferal distribution in two areas of the Ross Sea (Antarctica), Rend. Lincei Sci. Fis. Nat., 31, 1037–1053, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12210-020-00949-z, 2020.

Caridi, F., Langone, L., Sartini, A., Morigi, C., Galli, G., Giordano, P., Bensi, M., Kovacevic, V., Ursella, L., Krauzig, N., and Sabbatini, A.: Marine benthic foraminifera diversity in extreme environments: A case study from the Edisto Bay (Ross Sea, Antarctica), Mar. Micropaleontol., 203, 102553, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2026.102553, 2026.

Cornelius, N. and Gooday, A. J.: “Live” (stained) deep-sea benthic foraminiferans in the western Weddell Sea: trends in abundance, diversity and taxonomic composition along a depth transect, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 51, 1571–1602, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2004.06.024, 2004.

Cottier, F. R., Nilsen, F., Skogseth, R., Tverberg, V., Skardhamar, J., and Svendsen, H.: Arctic fjords: A review of the oceanographic environment and dominant physical processes, Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ., 344, 35–50, https://doi.org/10.1144/SP344.4, 2010.

Dexter, E., Rollwagen‐Bollens, G., and Bollens, S. M.: The trouble with stress: A flexible method for the evaluation of nonmetric multidimensional scaling, Limnology and Oceanography: Methods, 16, 434–443, https://doi.org/10.1002/lom3.10257, 2018.

Dillon, E. M., Pier, J. Q., Smith, J. A., Raja, N. B., Dimitrijević, D., Austin, E. L., Cybulski, J. D., De Entrambasaguas, J., Durham, S. R., Grether, C. M., Haldar, H. S., Kocáková, K., Lin, C.-H., Mazzini, I., Mychajliw, A. M., Ollendorf, A. L., Pimiento, C., Regalado Fernández, O. R., Smith, I. E., and Dietl, G. P.: What is conservation paleobiology? Tracking 20 years of research and development, Front. Ecol. Evol., 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.1031483, 2022.

Di Roberto, A., Re, G., Scateni, B., Petrelli, M., Tesi, T., Capotondi, L., Morigi, C., Galli, G., Colizza, E., Melis, R., Torricella, F., Giordano, P., Giglio, F., Gallerani, A., and Gariboldi, K.: Cryptotephras in the marine sediment record of the Edisto Inlet, Ross Sea: Implications for the volcanology and tephrochronology of northern Victoria Land, Antarctica, Quaternary Science Advances, 10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qsa.2023.100079, 2023.

Fillon, R. H.: Late Cenozoic Foraminiferal Paleoecology of the Ross Sea, Antarctica, Micropaleontology, 20, 129, https://doi.org/10.2307/1485056, 1974.

Finocchiaro, F., Langone, L., Colizza, E., Fontolan, G., Giglio, F., and Tuzzi, E.: Record of the early Holocene warming in a laminated sediment core from Cape Hallett Bay (Northern Victoria Land, Antarctica), Glob. Planet. Change, 45, 193–206, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2004.09.003, 2005.

Fossile, E., Nardelli, M. P., Jouini, A., Lansard, B., Pusceddu, A., Moccia, D., Michel, E., Péron, O., Howa, H., and Mojtahid, M.: Benthic foraminifera as tracers of brine production in the Storfjorden “sea ice factory”, Biogeosciences, 17, 1933–1953, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-1933-2020, 2020.

Fraser, A. D., Massom, R. A., Michael, K. J., Galton-Fenzi, B. K., and Lieser, J. L.: East Antarctic Landfast Sea Ice Distribution and Variability, 2000–2008, J. Climate, 25, 1137–1156, https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-10-05032.1, 2012.

Fraser, A. D., Wongpan, P., Langhorne, P. J., Klekociuk, A. R., Kusahara, K., Lannuzel, D., Massom, R. A., Meiners, K. M., Swadling, K. M., Atwater, D. P., Brett, G. M., Corkill, M., Dalman, L. A., Fiddes, S., Granata, A., Guglielmo, L., Heil, P., Leonard, G. H., Mahoney, A. R., McMinn, A., van der Merwe, P., Weldrick, C. K., and Wienecke, B.: Antarctic Landfast Sea Ice: A Review of Its Physics, Biogeochemistry and Ecology, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022RG000770, 2023.

Frignani, M., Langone, L., Ravaioli, M., Sorgente, D., Alvisi, F., and Albertazzi, S.: Fine-sediment mass balance in the western Adriatic continental shelf over a century time scale, Mar. Geol., 222–223, 113–133, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2005.06.016, 2005.

Galli, G., Morigi, C., Melis, R., Di Roberto, A., Tesi, T., Torricella, F., Langone, L., Giordano, P., Colizza, E., Capotondi, L., Gallerani, A., and Gariboldi, K.: Paleoenvironmental changes related to the variations of the sea-ice cover during the Late Holocene in an Antarctic fjord (Edisto Inlet, Ross Sea) inferred by foraminiferal association, J. Micropalaeontol., 42, 95–115, https://doi.org/10.5194/jm-42-95-2023, 2023.

Galli, G., Morigi, C., Thuy, B., and Gariboldi, K.: Late Holocene echinoderm assemblages can serve as paleoenvironmental tracers in an Antarctic fjord, Sci. Rep., 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66151-5, 2024.

Galli, G., Hansen, K. E., Morigi, C., Di Roberto, A., Giglio, F., Giordano, P., and Gariboldi, K.: Edisto Inlet as a sentinel for Late Holocene environmental changes over the Ross Sea: insights from foraminifera turnover events, Clim. Past, 21, 1661–1677, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-21-1661-2025, 2025.

Gooday, A. J.: Deep-sea benthic foraminiferal species which exploit phytodetritus: Characteristic features and controls on distribution, Mar. Micropaleontol., 22, 187–205, https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-8398(93)90043-W, 1993.

Gooday, A. J.: Benthic Foraminifera (Protista) as Tools in Deep-water Palaeoceanography: Environmental Influences on Fauna Characteristics, Advance in Marine Biology, 46, 1–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2881(03)46002-1, 2003.

Gooday, A. J. and Rathburn, A. E.: Temporal variability in living deep-sea benthic foraminifera: a review, Earth-Science Reviews, 46, 187–212, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-8252(99)00010-0, 1999.

Gooday, A. J., Bowser, S. S., and Bernhard, J. M.: Benthic foraminiferal assemblages in Explorers Cove, Antarctica: A shallow-water site with deep-sea characteristics, Prog. Oceanogr., 37, 117–166, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6611(96)00007-9, 1996.

Sen Gupta, B. K.: Modern Foraminifera, Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-48104-9, 2003.

Gutt, J., Isla, E., Xavier, J. C., Adams, B. J., Ahn, I. Y., Cheng, C. C., Colesie, C., Cummings, V. J., di Prisco, G., Griffiths, H., Hawes, I., Hogg, I., McIntyre, T., Meiners, K. M., Pearce, D. A., Peck, L., Piepenburg, D., Reisinger, R. R., Saba, G. K., Schloss, I. R., Signori, C. N., Smith, C. R., Vacchi, M., Verde, C., and Wall, D. H.: Antarctic ecosystems in transition – life between stresses and opportunities, Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc., 96, 798–821, https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12679, 2021.

Hoogakker, B., Ishimura, T., de Nooijer, L., Rathburn, A., and Schmiedl, G.: A review of benthic foraminiferal oxygen and carbon isotopes, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 342, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2024.108896, 2024.

Howe, J. A., Austin, W. E. N., Forwick, M., Paetzel, M., Harland, R., and Cage, A. G.: Fjord systems and archives: a review, Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 344, 5–15, https://doi.org/10.1144/sp344.2, 2010.

Igarashi, A., Numanami, H., Tsuchiya, Y., and Fukuchi, M.: Bathymetric distribution of fossil foraminifera within marine sediment cores from the eastern part of Lützow-Holm Bay, East Antarctica, and its paleoceanographic implications, Mar. Micropaleontol., 42, 125–162, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-8398(01)00004-4, 2001.

Ingels, J., Vanreusel, A., Brandt, A., Catarino, A. I., David, B., De Ridder, C., Dubois, P., Gooday, A. J., Martin, P., Pasotti, F., and Robert, H.: Possible effects of global environmental changes on Antarctic benthos: A synthesis across five major taxa, Ecol. Evol., 2, 453–485, https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.96, 2012.

Ishman, S. E. and Sperling, M. R.: Benthic foraminiferal record of Holocene deep-water evolution in the Palmer Deep, western Antarctica Peninsula, Geology, 30, 435–438, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0435:BFROHD>2.0.CO;2, 2002.

Ishman, S. E. and Szymcek, P.: Foraminiferal Distributions in the Former Larsen-A Ice Shelf and Prince Gustav Channel Region, Eastern Antarctic Peninsula Margin: A Baseline for Holocene Paleoenvironmental Change, in: Antarctic Peninsula Climate Variability: Historical and Paleoenvironmental Perspectives, American Geophysical Union, 239–260, https://doi.org/10.1029/AR079p0239, 2003.

Jorissen, F. J., de Stigter, H. C., and Widmark, J. G. V.: A conceptual model explaining benthic foraminiferal microhabitats, Marine Micropaleontology, 26, 3–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-8398(95)00047-X, 1995.

Kassambra, A.: ggcorrplot: Visualization of a correlation Matrix using “ggplot2,” R package version 0.1.4.999, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggcorrplot/readme/README.html (last access: 20 October 2025), 2022.

Kellogg, T. B., Osterman, L. E., and Stuiver, M.: Late Quaternary sedimentology and benthic foraminiferal paleoecology of the Ross Sea, Antarctica, Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 9, 322–335, https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.9.4.322, 1979.

Kender, S. and Kaminski, M. A.: Modern deep-water agglutinated foraminifera from IODP Expedition 323, Bering Sea: ecological and taxonomic implications, J. Micropalaeontol., jmpaleo2016-026, https://doi.org/10.1144/jmpaleo2016-026, 2017.

Kennett, J. P.: Foraminiferal Evidence of a Shallow Calcium Carbonate Solution Boundary, Ross Sea, Antarctica, Science, 153, 191–193, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.153.3732.191, 1966.

Kruskal, J. B.: Nonmetric multidimensional scaling: a numerical method, Psychometrika, 29, 115–119, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289694, 1964.

Kyrmanidou, A., Vadman, K. J., Ishman, S. E., Leventer, A., Brachfeld, S., Domack, E. W., and Wellner, J. S.: Late Holocene oceanographic and climatic variability recorded by the Perseverance Drift, northwestern Weddell Sea, based on benthic foraminifera and diatoms, Mar. Micropaleontol., 141, 10–22, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2018.03.001, 2018.

Langlet, D., Mermillod-Blondin, F., Deldicq, N., Bauville, A., Duong, G., Konecny, L., Hugoni, M., Denis, L., and Bouchet, V. M. P.: Single-celled bioturbators: benthic foraminifera mediate oxygen penetration and prokaryotic diversity in intertidal sediment, Biogeosciences, 20, 4875–4891, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-20-4875-2023, 2023.

LaRowe, D. E., Arndt, S., Bradley, J. A., Estes, E. R., Hoarfrost, A., Lang, S. Q., Lloyd, K. G., Mahmoudi, N., Orsi, W. D., Shah Walter, S. R., Steen, A. D., and Zhao, R.: The fate of organic carbon in marine sediments – New insights from recent data and analysis, Earth-Sci. Rev., 204, 103146, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103146, 1 May 2020.

Lehrmann, A. A., Totten, R. L., Wellner, J. S., Hillenbrand, C.-D., Radionovskaya, S., Comas, R. M., Larter, R. D., Graham, A. G. C., Kirkham, J. D., Hogan, K. A., Fitzgerald, V., Clark, R. W., Hopkins, B., Lepp, A. P., Mawbey, E., Smyth, R. V., Miller, L. E., Smith, J. A., and Nitsche, F. O.: Recent benthic foraminifera communities offshore of Thwaites Glacier in the Amundsen Sea, Antarctica: implications for interpretations of fossil assemblages, J. Micropalaeontol., 44, 79–105, https://doi.org/10.5194/jm-44-79-2025, 2025.

Levin, L. A., Ekau, W., Gooday, A. J., Jorissen, F., Middelburg, J. J., Naqvi, S. W. A., Neira, C., Rabalais, N. N., and Zhang, J.: Effects of natural and human-induced hypoxia on coastal benthos, Biogeosciences, 6, 2063–2098, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-6-2063-2009, 2009.

Li, B., Yoon, H., and Park, B.: Foraminiferal assemblages and CaCO3 dissolution since the last deglaciation in the Maxwell Bay, King George Island, Antarctica, Mar. Geol., 169, 239–257, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-3227(00)00059-1, 2000.

Loeblich, A. R. and Tappan, H.: Foraminiferal Genera and Their Classification, Springer US, Boston, MA, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-5760-3, 1988.

Lo Giudice Cappelli, E. and Austin, W. E. N.: Size Matters: Analyses of Benthic Foraminiferal Assemblages Across Differing Size Fractions, Front. Mar. Sci., 6, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00752, 2019.

Lohrer, A. M., Cummings, V. J., and Thrush, S. F.: Altered Sea Ice Thickness and Permanence Affects Benthic Ecosystem Functioning in Coastal Antarctica, Ecosystems, 16, 224–236, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-012-9610-7, 2013.

Lukina, T. G.: Foraminifera of the Laptev Sea, Protistology, 2, 105–122, 2001.

Mackensen, A., Grobe, H., Kuhn, G., and Futterer, D. K.: Benthic foraminiferal assemblages from the eastern Weddell Sea between 68 and 73° S: distribution, ecology and fossilization potential, Mar. Micropaleontol., 16, 241–283, https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-8398(90)90006-8, 1990.

Majewski, W.: Benthic foraminiferal communities: distribution and ecology in Admiralty Bay, King George Island, West Antarctica, Pol. Polar Res., 26, 159–214, 2005.

Majewski, W.: Benthic foraminifera from West Antarctic fiord environments: An overview, Pol. Polar Res., 31, 61–82, https://doi.org/10.4202/ppres.2010.05, 2010.

Majewski, W. and Anderson, J. B.: Holocene foraminiferal assemblages from Firth of Tay, Antarctic Peninsula: Paleoclimate implications, Mar. Micropaleontol., 73, 135–147, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2009.08.003, 2009.

Majewski, W. and Pawlowski, J.: Morphologic and molecular diversity of the foraminiferal genus Globocassidulina in Admiralty Bay, King George Island, Antarct. Sci., 22, 271–281, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954102010000106, 2010.

Majewski, W., Pawłoski, J., and Zajączkowski: Monothalmous foraminifera from West Spitsbergen fjords, Svalbard: a brief overview, Pol. Polar Res., 26, 269–285, 2005.

Majewski, W., Wellner, J. S., and Anderson, J. B.: Environmental connotations of benthic foraminiferal assemblages from coastal West Antarctica, Mar. Micropaleontol., 124, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2016.01.002, 2016.

Majewski, W., Bart, P. J., and McGlannan, A. J.: Foraminiferal assemblages from ice-proximal paleo-settings in the Whales Deep Basin, eastern Ross Sea, Antarctica, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 493, 64–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.12.041, 2018.

Majewski, W., Stolarski, J., and Bart, P. J.: Two rare pustulose/spinose morphotypes of benthic foraminifera from eastern Ross Sea, Antarctica, J. Foraminifer. Res., 49, 405–422, https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.49.4.405, 2019.

Majewski, W., Prothro, L. O., Simkins, L. M., Demianiuk, E. J., and Anderson, J. B.: Foraminiferal Patterns in Deglacial Sediment in the Western Ross Sea, Antarctica: Life Near Grounding Lines, Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol., 35, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019pa003716, 2020.

Majewski, W., Szczuciński, W., and Gooday, A. J.: Unique benthic foraminiferal communities (stained) in diverse environments of sub-Antarctic fjords, South Georgia, Biogeosciences, 20, 523–544, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-20-523-2023, 2023.

McKnight, W. M.: The distribution of Foraminifera off parts of the Antarctic Coast, Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, NY, https://search.library.berkeley.edu/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma991070192479706532&context=L&vid=01UCS_BER:UCB&lang=en&adaptor=Local Search Engine (last access: 29 February 2025), 1962.

Melis, R. and Salvi, G.: Late Quaternary foraminiferal assemblages from western Ross Sea (Antarctica) in relation to the main glacial and marine lithofacies, Mar. Micropaleontol., 70, 39–53, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2008.10.003, 2009.

Misic, C., Bolinesi, F., Castellano, M., Olivari, E., Povero, P., Fusco, G., Saggiomo, M., and Mangoni, O.: Factors driving the bioavailability of particulate organic matter in the Ross Sea (Antarctica) during summer, Hydrobiologia, 851, 2657–2679, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-024-05482-w, 2024.

Murray, J. W.: Ecology and Applications of Benthic Foraminifera, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511535529, 2006.

Murray, J. W. and Pudsey, C. J.: Living (stained) and dead foraminifera from the newly ice-free Larsen Ice Shelf, Weddell Sea, Antarctica: Ecology and taphonomy, Mar. Micropaleontol., 53, 67–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2004.04.001, 2004.

Nomaki, H., Ogawa, N. O., Ohkouchi, N., Suga, H., Toyofuku, T., Shimanaga, M., Nakatsuka, T., and Kitazato, H.: Benthic foraminifera as trophic links between phytodetritus and benthic metazoans: Carbon and nitrogen isotopic evidence, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 357, 153–164, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps07309, 2008.

Oksanen, J., Simpson, G. L., Blanchet, F. G., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., Minchin, P. R., O'Hara, R. B., Solymos, P., Stevens, M. H. H., Szoecs, E., Wagner, H., Barbour, M., Bedward, M., Bolker, B., Borcard, D., Carvalho, G., Chirico, M., De Caceres, M., Durand, S., Evangelista, H. B. A., FitzJohn, R., Friendly, M., Furneaux, B., Hannigan, G., Hill, M. O., Lahti, L., McGlinn, D., Ouellette, M.-H., Ribeiro Cunha, E., Smith, T., Stier, A., Ter Braak, C. J. F., and Weedon, J.: vegan: Community Ecology Package, https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.vegan, 2024.

Peck, V. L., Allen, C. S., Kender, S., McClymont, E. L., and Hodgson, D. A.: Oceanographic variability on the West Antarctic Peninsula during the Holocene and the influence of upper circumpolar deep water, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 119, 54–65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.04.002, 2015.

Pflum, C. E.: The distribution of Foraminifera in the eastern Ross Sea, Amundsen Sea and Bellingshausen Sea, Antarctica, Paleontological Research Institute, Ithaca, NY, https://search.library.berkeley.edu/discovery/fulldisplay?vid=01UCS_BER:UCB&docid=alma991070189069706532&context=L (last access: 29 February 2025), 1966.

Prentice, I. C.: Non-Metric Ordination Methods in Ecology, J. Ecol., 65, 85, https://doi.org/10.2307/2259064, 1977.

R Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, https://www.R-project.org/, last access: 21 December 2024.

Rodrigues, A. R., Eichler, P. P. B., and Eichler, B. B.: Foraminifera in Two Inlets Fed by a Tidewater Glacier, King George Island, Antarctic Peninsula, Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 43, 209–220, https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.43.3.209, 2013.

Sabbatini, A., Morigi, C., Negri, A., and Gooday, A. J.: Distribution and biodiversity of stained monothalamous foraminifera from Tempelfjord, Svalbard, Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 37, 93–106, https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.37.2.93, 2007.

Seidenkrantz, M.-S.: Benthic foraminifera as palaeo sea-ice indicators in the subarctic realm – examples from the Labrador Sea–Baffin Bay region, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 79, 135–144, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.03.014, 2013.

Smart, C. W., King, S. C., Gooday, A. J., Murray, J. W., and Thomas, E.: A benthic foraminiferal proxy of pulsed organic matter paleofluxes Marine Micropaleontology, 23, 89–99, https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-8398(94)90002-7, 1994.

Smith, R. W., Bianchi, T. S., Allison, M., Savage, C., and Galy, V.: High rates of organic carbon burial in fjord sediments globally, Nat. Geosci., 8, 450–453, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2421, 2015.

Tesi, T., Langone, L., Goñi, M. A., Wheatcroft, R. A., Miserocchi, S., and Bertotti, L.: Early diagenesis of recently deposited organic matter: A 9-yr time-series study of a flood deposit, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 83, 19–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2011.12.026, 2012.

Tesi, T., Belt, S. T., Gariboldi, K., Muschitiello, F., Smik, L., Finocchiaro, F., Giglio, F., Colizza, E., Gazzurra, G., Giordano, P., Morigi, C., Capotondi, L., Nogarotto, A., Köseoğlu, D., Di Roberto, A., Gallerani, A., and Langone, L.: Resolving sea ice dynamics in the north-western Ross Sea during the last 2.6 ka: From seasonal to millennial timescales, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 237, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106299, 2020.

Violanti, D.: Morphogroup Analysis of Recent Agglutinated Foraminifers off Terra Nova Bay, Antarctica (Expedition 1987–1988), Ross Sea Ecology, 479–492, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-59607-0_34, 2000.

Ward, B. L., Barret, P. J., and Vella, P.: Distribution and ecology of benthic foraminifera in McMurdo Sound, Antarctica, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 58, 139–153, https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(87)90057-5, 1987.

Weinkauf, M. F. G. and Milker, Y.: The Effect of Size Fraction in Analyses of Benthic Foraminiferal Assemblages: A Case Study Comparing Assemblages From the >125 and >150 µm Size Fractions, Front. Earth Sci. (Lausanne), 6, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2018.00037, 2018.

Wicham, H., Pedersen, T. L., and Seidel, D.: scales: Scale Functions for Visualizations, R package version 1.4.0, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html (last access: 20 October 2025), 2025.

Wickham, H.: ggplot2, WIREs Computational Statistics, 3, 180–185, https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.147, 2011.

Zhao, K. X., Stewart, A. L., and McWilliams, J. C.: Linking Overturning, Recirculation, and Melt in Glacial Fjords, Geophys. Res. Lett., 49, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL095706, 2022.