the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Effects of light and temperature on Mg uptake, growth, and calcification in the proxy climate archive Clathromorphum compactum

Siobhan Williams

Walter Adey

Jochen Halfar

Andreas Kronz

Patrick Gagnon

David Bélanger

Merinda Nash

The shallow-marine benthic coralline alga Clathromorphum compactum is an important annual- to sub-annual-resolution archive of Arctic and subarctic environmental conditions, allowing reconstructions going back > 600 years. Both Mg content, in the high-Mg calcitic cell walls, and annual algal growth increments have been used as a proxy for past temperatures and sea ice conditions. The process of calcification in coralline algae has been debated widely, with no definitive conclusion about the role of light and photosynthesis in growth and calcification. Light received by algal specimens can vary with latitude, water depth, sea ice conditions, water turbidity, and shading. Furthermore, field calibration studies of Clathromorphum sp. have yielded geographically disparate correlations between MgCO3 and sea surface temperature. The influence of other environmental controls, such as light, on Mg uptake and calcification has received little attention. We present results from an 11-month mesocosm experiment in which 123 wild-collected C. compactum specimens were grown in conditions simulating their natural habitat. Specimens grown for periods of 1 and 2 months in complete darkness show that the typical complex of anatomy and cell wall calcification develops in new tissue without the presence of light, demonstrating that calcification is metabolically driven and not a side effect of photosynthesis. Also, we show that both light and temperature significantly affect MgCO3 in C. compactum cell walls. For specimens grown at low temperature (2 ∘C), the effects of light are smaller, with a 1.4 mol % MgCO3 increase from low-light (mean = 17 lx) to high-light conditions (mean = 450 lx). At higher (10 ∘C) temperature there was a 1.8 mol % MgCO3 increase from low to high light. It is therefore concluded that site- and possibly specimen-specific temperature calibrations must be applied, to account for effects of light when generating Clathromorphum-derived temperature calibrations.

- Article

(14022 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2011 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The coralline alga Clathromorphum compactum exhibits well-defined annual growth increments and often produces seasonal conceptacles (seasonal autumn/winter reproductive structures) within those increments (Adey and Hayek, 2011; Halfar et al., 2008). The ovoid conceptacles are embedded within a considerably larger vegetative matrix consisting of a plethora of tissues (Adey, 1965; Adey et al., 2013) within calcified cell walls. The calcified cell walls additionally show a variety of well-defined micro-structures in their high-magnesium calcitic skeleton (Adey et al., 2005; Nash and Adey, 2017, 2018). Owing to C. compactum longevity, multicentennial chronologies that have the potential to provide data necessary for accurately calibrating climate models have been constructed (Adey, 1965; Adey et al., 2015a, b; Halfar et al., 2013). C. compactum grows in subarctic to high-Arctic oceans in the benthic mid photic zone, and its distribution becomes severely limited at temperatures above 11–13 ∘C (Adey, 1965).

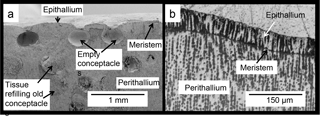

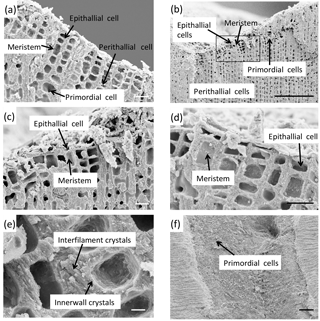

Figure 1(a) Cross section of C. compactum mound indicating major skeletal features. (b) Close-up of meristem, epithallium, and perithallium cells.

The precise mode of calcification in coralline algae has been long debated (Adey, 1998; Nash et al., 2018), and the role of photosynthesis in influencing calcification has not yet been fully established. The shape of Mg content curves from subarctic/Arctic Clathromorphum sp. suggests that they continue to grow and calcify for at least part of the winter in darkness at −1.8 ∘C (Halfar et al., 2013). A recent model of coralline calcification (Nash and Adey, 2017) shows fibrous cellulosic extrusions from the cell membranes into the cell wall environment that provide molecular initiation centres for calcium and magnesium, but it does not demonstrate a process for cellular injection of Ca and Mg. Their model indicates Mg control by temperature in a complex subset of calcification modes but does not include a light component (other than as a basic photosynthetic requirement).

Production of C. compactum's high-magnesium calcite skeleton occurs in an intercalary meristem (as in the cambium of higher plants) and is concurrent with cellular and tissue growth (Fig. 1). The intercalary meristem, in addition to producing perithallium, the primary body of the calcified crust, also generates the thin upper layer of the epithallium, the primary photosynthetic tissue of these plants (Adey, 1965). The perithallial tissue below the meristem preserves the annual growth increments and the remains of the yearly conceptacles, which are ovoid conceptacle cavities (Fig. 1). The primary hypothallium is a multicellular tissue forming the base of each individual and provides attachment to the substratum (Adey, 1965). Since it shows a modified form of calcification with higher Mg levels than the perithallium (Nash and Adey, 2018), it is not utilized in climate archiving. Wound tissue and secondary hypothallia develop to repair physical damage, inflicted by wave tools or grazers to the algal thallus (Fig. 1). While occasionally grazing can damage the meristem and perithallus, most grazing is restricted to the epithallus. A “symbiotic” association between chiton and limpet grazing and Clathromorphum sp. has been demonstrated, and moderate grazing of surficial epithallium is required to keep the meristem active (Adey, 1973; Steneck, 1982).

Skeletal elemental composition (Mg ∕ Ca) of Clathromorphum sp. has been shown to correspond to temperature controls (Gamboa et al., 2010; Halfar et al., 2008; Hetzinger et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2018) and displays seasonal cyclicity (Adey et al., 2013). However, there is evidence that light is also influencing Mg incorporation (Moberly, 1968). For example, in the Newfoundland shallow benthos, C. compactum Mg ∕ Ca ratios begin to increase in the spring before temperatures increased from the winter lows (Gamboa et al., 2010). In addition, several studies have noted inter-sample variability in Mg ∕ Ca (e.g. Chan et al., 2011) and published Clathromorphum sp. Mg ∕ Ca – temperature calibrations have been site specific (Hetzinger et al., 2009, 2018; Williams et al., 2014). It has been hypothesized that, because algae collected at the same site are experiencing similar temperatures, inter-sample variability may be caused by differences in shading or orientation relative to the sea surface (Williams et al., 2014). Differences among calibrations might also result from collections at different depths or different water clarity between sites of similar depths.

There is also evidence for the influence of light and temperature on growth rates of coralline algae. Adey (1970) demonstrated that growth of many Boreal–subarctic coralline algal genera exhibited a strong relationship with light at high temperatures and a weak relationship with light at low temperatures. These patterns suggest growth is limited by photosynthesis in water temperatures above 4–5 ∘C, while respiration and other growth processes likely limit growth at lower temperatures (Adey, 1970). Similarly, Halfar et al. (2011a) found a positive correlation between water temperature and Clathromorphum sp. growth increment width in the North Atlantic where winter sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are below 0 ∘C, whereas Clathromorphum sp. growth in the Bering Sea (winter SST > 3 ∘C) was unrelated to temperature yet was positively correlated with light (Halfar et al., 2011b). This supports Adey's (1970) finding that growth is limited by photosynthetic production in warmer water, whereas it is temperature-controlled in colder water. Adey et al. (2013) modelled the relative control of temperature and light in algal systems, showing that, over a broad range of temperatures and light, temperature had a somewhat larger effect on productivity than light. Since both temperature and light are limiting factors, the most limiting will be controlling productivity. However, in winter subarctic conditions, both factors are at or near limiting conditions. Similarly, cloud cover, another light proxy, has been linked to the summer calcification of the rhodolith-forming coralline alga Lithothamnion glaciale (Burdett et al., 2011). In that study, lower light levels caused by winter cloud cover reduced summer carbonate density (Burdett et al., 2011). Additionally, Teichert and Freiwald (2014) found light to be the most important, and mean annual temperature to be the second-most-important, physical parameter limiting calcium carbonate production of coralline algae on the Svalbard shelf. Furthermore, Halfar et al. (2013) used the influence of light on both growth rates and Mg ∕ Ca to reconstruct sea ice cover in the Arctic. Sea ice cover constrains growth by limiting photosynthates that the algae produce (Halfar et al., 2013). Also, bottom temperatures remain relatively constant below sea ice and more ice-free days allow for higher temperatures, which are recorded in the Mg ∕ Ca of the algae (Halfar et al., 2013). In summary, both light and temperature have demonstrated effects on coralline algal calcification and Mg ∕ Ca.

Contrary to the majority of photosynthetic calcifiers, C. compactum can thrive in the absence of light for over half of the year. For example, C. compactum is found in abundance in Arctic Bay, Nunavut, Canada, at 73∘ N, where sea ice cover causes near darkness at the sea floor for up to 9 months of the year (Halfar et al., 2013). Regardless of ice, C. compactum has been found in Novaya Zemlya (Adey et al., 2015b), an archipelago in the Russian Arctic where there is less than 1 h of sunlight per day for 4 months of the year. These relationships prevail in other distantly related coralline genera from high-latitude warmer (Boreal) waters as shown by the ability of Phymatolithon borealis, P. investiens, P. tenue, and L. glaciale to develop extensive crusts and mobile rhodoliths in the far north of Norway, where long winter darkness also occurs (Adey et al., 2018; Teichert et al., 2013). Even though growth rate is controlled by light and temperature, the chemistry of the associated calcification does not rely directly on photosynthesis but rather on total quantity of photosynthates.

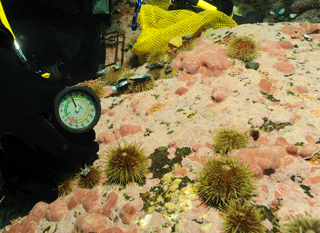

Figure 2Clathromorphum compactum mounds (dark red) up to 3 cm thick in a typical coralline community at 13 m depth off Quirpon Island in northernmost Newfoundland. Photo by Nick Caloyianus.

It is clear that a better understanding of the effects of temperature and light (or lack thereof) on C. compactum growth, calcification, and elemental composition is necessary to fully understand C. compactum biology and ecology, and the use of this species as a climate archive. In this study, we examine multiple specimens of C. compactum, monitored at a range of light, temperature, and time treatments in a suite of tanks having the same open-coast-source water supply. Post-experiment, multiple samples were analysed for their anatomical and cellular changes, growth, and MgCO3 composition relative to the various treatments.

2.1 Test subjects

One hundred and twenty-three living specimens of Clathromorphum compactum were chipped off rocky surfaces by divers in August 2012 at 10–12 m depths in Bread and Cheese Cove, Bay Bulls, Newfoundland (47∘18.57′ N; 52∘46.98′ W). The C. compactum specimens were dome-shaped, 3–6 cm in diameter, and 1–3 cm thick, a common size in Newfoundland and Southern Labrador (Fig. 2). Clathromorphum species are highly distinctive and easily separated from other coralline species in the region by their surface features and deep intercalary meristem (Adey, 1965; Adey et al., 2015b). C. circumscriptum, the only other species of the genus in the northwestern Atlantic, occurs primarily in shallow water, rarely reaching to the depth of specimen collection in this study, and at maturity is morphologically quite distinctive (Adey, 1965; Adey et al., 2013). As each collected specimen was delivered by divers to the dive boat for selection and initial scarring, it was identified aboard by co-author WHA. During the experiment, each individual specimen, as selected for analysis, was tagged with a number, after removal from the tanks, for tracking through analysis; the specimens are stored in the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) with those identification tags for future reference.

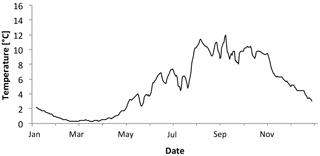

Figure 4Five-day average temperatures through 2011 at Bay Bulls, Bread and Cheese Cove, at 10 m, taken with HOBO data loggers.

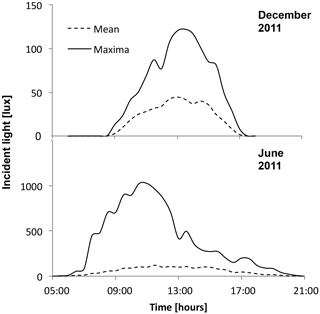

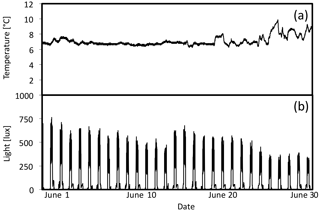

Year-long temperature and light data (lux) were measured with in situ HOBO loggers (HOBO Pendant; Onset Computer Corporation) at a depth of 12 m at Bread and Cheese Cove (Figs. 3 and 4). The calibration of the HOBO light loggers used in the experiment was confirmed against the earlier field data by installing the same sensors at the field site for a single day. This provided values similar to the previous time series. In addition, temperature–depth profiles were obtained from Adey (1966) for four exposed stations on the east and northeast coast of Newfoundland, along with a relative abundance–depth profile of C. compactum at those sites (Supplement Fig. S1). Both sources of instrumental data were used to establish the temperature and light parameters of the mesocosm complex.

Figure 5Experimental tank layout at the Ocean Sciences Centre at Logy Bay, NF. High-light right end of each tank is adjacent to large port-like window and has fluorescent lights overlying. Opposite, low-light ends of tanks shielded with opaque plastic sheet. Note cooling probes, coated with ice, placed in 2 and 4 ∘C tanks on left. Three light segments (left to right: low light, ll; mid-light. ml; high light, hl) with their emplaced specimens can be seen in right tank.

There were several reasons for not measuring photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) in this study. (1) Considerable pre-existing field evidence suggested that calcification in Clathromorphum (and other corallines) is not directly related to photosynthesis (Nash and Adey, 2018), but rather only to the availability of stored photosynthate energy. (2) Being red algae, and having the accessory pigments phycocyanin and phycoerythrin that supplement chlorophyll, corallines have quite different action spectra from green algae or higher plants. Also, since these algae reach a peak of cover at about 20 m, we were working with available light spectra that would be very different from those at the water surface. Using PAR sensors would have raised as many questions as it solved. (3) Since C. compactum occurs over a wide depth range (5–30 m), the level of photosynthesis varies widely, and previous studies have not indicated major changes in growth and calcification over that range. Thus we would not have expected a strong relationship between our parameters of interest and light spectra. (4) Adding PAR, with or instead of lux, especially since action spectra responses would have been an essential component requiring individual chambers for each specimen, would have significantly increased the difficulty and cost of carrying out the experiment.

2.2 Experimental setup

The experiment was carried out at the Ocean Sciences Centre (OSC) of Memorial University of Newfoundland from September 2012 to July 2013. Sea water, pumped in from a depth of 5 m in the adjacent embayment, Logy Bay, was provided through a constant-flow system at 1 L min−1 to each tank. Four 180 L glass tanks were placed so that natural light from large rounded windows was provided at one end of each pair of tanks, with the opposite ends of the tanks shaded with black plastic sheets (Fig. 5). Sixty-centimetre-long, 20 W Hagen Marine-GLO T8 fluorescent tubes were positioned over the window-lighted end of each tank so as to provide a significant light gradient (Fig. 6). The light covered one half of each tank (the high-light section). The immediate darker quarter of each tank was the mid-light section, and the darkest quarter the low-light section. The fluorescent tubes were automatically switched on at 10:00 and off at 15:00. Day length and morning and evening light intensity were supplied by natural sunlight from the north-facing windows. Experimental temperatures were 2, 4, 7, and 10 ∘C. All tanks were supplied with 4 ∘C seawater from a master chiller at a constant flow rate of 1 L min−1. Temperatures in the 7 and 10 ∘C tanks were obtained with immersion heaters (Hagen, Fluval M300). Temperatures in the 2 ∘C tank were obtained with two immersion probe coolers (Polyscience, IP 35RCC). September was a month of gradual temperature change in each tank from roughly 12 ∘C incoming sea water to each experimental value.

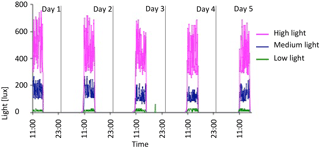

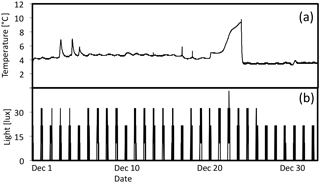

Figure 6Five-day plot of light levels taken from HOBO loggers in October 2012 in 10 ∘C tank. Pink is high light, blue is medium light, and green is low light.

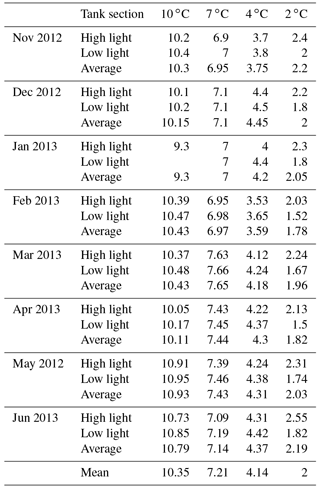

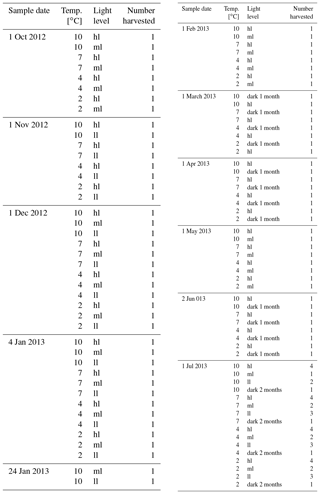

HOBO data loggers were placed in each tank at high- and low-light positions to quantify light and temperature at 5 min intervals throughout the experiment (Figs. 6–8). A pre-experimental trial with data loggers in all three sections produced a light value as a proportion of that in the high-light tank for the remainder of the experiment (Fig. 6). Mean light levels in October were as follows: high light = 450 lx, medium light = 142 lx, and low light = 17 lx (Fig. 6). The monthly mean temperatures at each light level in each tank are shown in Table 1. Occasional changes in flow rates of the sea water supply as well as heater function required manual system adjustments to bring temperature to desired values. Due to the limitations of the laboratory and available equipment, the −1.5 to 1 ∘C temperature levels representing winter temperatures in coastal Newfoundland were not achieved, with 2 ∘C being the lowest temperature attained for the long-term experiment.

2.3 Placement and harvest of C. compactum specimens in mesocosm

To mark the beginning of the experiment (September 2012), the specimens of C. compactum were placed in a tank containing approximately 85 mg alizarin red dye per liter of seawater for 48 h. Alizarin red is incorporated into the living algal tissue, and it leaves a permanent red stain line (Kamenos et al., 2008). However, the stain was not incorporated in the tissues, likely because the test subjects did not grow sufficiently during the staining process, so staining information was not part of this study.

Figure 8(a) Temperature (∘C) and (b) light (lux) during December in high-light portion of 7 ∘C tank.

Each specimen was also laterally scarred (incised) with a fine metal file to a depth of 200–400 µm aboard the dive skiff immediately following collection (Fig. 2). The incisions, when sectioned by vertical fracturing, allowed for a scanning electron microscope (SEM)-based estimate of rate of wound tissue growth during the experiment, as well as study of the process of wound repair. Electron microprobe examination was separately applied to sections of normal (unscarred) perithallial tissue and used to estimate the beginning of the experiment (shown by the cessation of seasonal Mg fluctuation). The annual maximum Mg ∕ Ca was used to denote the beginning of the experiment for electron microprobe data, since this represents highest temperatures annually at the collection site, which occur in August, at the time of collection.

The 123 Clathromorphum compactum specimens from Bread and Cheese Cove were distributed evenly within each of the four experimental tanks, with ∼10 specimens in each light zone (for a total of 30 subjects in each tank). On the first of each month, beginning with 1 October, individual specimens were haphazardly collected from each light zone of each tank with the intention of leaving the remaining specimens evenly distributed over the zone space so as not to bias in-zone distribution with time. After collection, specimens were oven-dried for 48 h at 40 ∘C and shipped to the NMNH for sectioning and anatomical analysis with SEM (Table 2). Using SEM, the progress of regrowth of the scarred tissue, as well as the status of the meristem and epithallial and hypothallial tissues, was determined. Of the 123 subjects, 3 were lost to “white-patch disease”, which is occasionally seen in the wild (Adey et al, 2013), and 85 were vertically fractured in an attempt both to cut across the scars made immediately after collection and to section the peak of the mound. The remaining 35 specimens, mostly collected on 1 July 2013, at the close of the experiment, were also sent to the NMNH coralline herbarium, as the ClEx Collection, for examination and voucher storage.

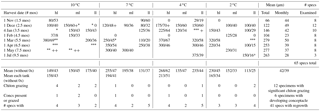

Table 2C. compactum growth experiment (ClEx) at Logy Bay, Newfoundland. Specimens collected in mid-August 2012 and brought to experimental temperature through September 2012. High light (hl) was < 400 lx, medium light (ml) was < 160 lx, and low light (ll) was < 17 lx.

Anatomy, growth, and calcification in the dark (Adey et al., 2013, 2015) were also monitored and measured, since C. compactum is primarily an Arctic species and is seasonally exposed to periods of up to 9 months without sunlight. On 1 February 2013, and repeated on 1 May 2013, 16 specimens from the low-light areas of each of the experimental mesocosms were re-scarred (position of scar several millimetres removed from the original scar) and placed in in situ dark chambers. These specimens were subsequently collected at 1–2-month intervals (Table 2) and examined in SEM to determine the extent of wound recovery in the dark (Fig. 9a).

Table 3Number of transects analysed with electron microprobe from each temperature and light level. Number of samples from each level in brackets.

Each experimental mesocosm had chitons (Tonicella spp.), collected at Bay Bulls, added in roughly equal numbers to the number of C. compactum mounds present in each tank. The chitons, normally having home sites on or near C. compactum in the wild, established home sites beneath the experimental specimens; because the chitons might not travel over glass from specimen to specimen, we provided one to each C. compactum mound. The reason for including chitons in the experiment is the above-described symbiotic relationship between grazing and Clathromorphum sp.

2.4 Sample analyses

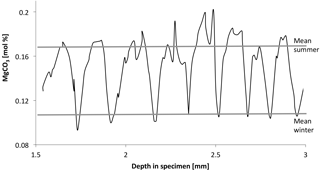

All specimens were examined at the NMNH Imaging Laboratory at a range of magnifications from 50× to 5000× on a Leica Stereoscan 440 SEM operated at 10 kV, a 13–15 mm working distance, and a sample current of 101 pA. Specimens harvested in July, at the end of the experiment, were sectioned vertically and polished using diamond suspension to a grit size of 1 µm. The software geo.TS (Olympus Soft Imaging Systems) was utilized with an automated sampling stage on a reflected-light microscope to produce two-dimensional maps of the experimental subjects' polished surfaces. These high-resolution composite images were used to identify the first annual growth increment and to select linear transects for geochemical analysis across the annual growth increment, encompassing the length of the experiment and avoiding the wound area of the samples (for details see Hetzinger et al., 2009). One to three parallel electron microprobe line transects were analysed for algal MgCO3 composition on each subject (Table 3) from the meristem to the first growth line at the University of Göttingen, Germany, using a JEOL JXA 8900 RL electron microprobe. An acceleration voltage of 10 kV, a spot diameter of 7 µm, and a beam current of 12 nA were used. Along transects samples were obtained at intervals of 10 µm; to avoid unsuitable areas such as uncalcified cell interiors, the location of analyses were manually chosen no more than 20 µm laterally from the transect line. Further details of the method are described in Halfar et al. (2013).

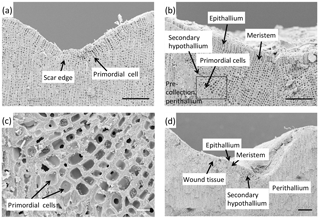

Figure 9Example of wound recovery of C. compactum. (a) Section of C. compactum mound through the scar groove, collected from low-light, 2 ∘C tank on 1 December 2012 after 2.5 months of recovery. Wound regrowth was initiated with one or more large primordial cells that gradually transition into normal perithallial cells. Following the production of three to four typical perithallial cells, meristem cells have developed and are beginning to produce epithallial cells (ClEx 121 211). (b) Scar groove section of C. compactum mound from the high-light, 2 ∘C tank after 6 months of recovery. Groove has nearly grown in with normal meristem cells and perithallial and epithallial tissue. See blow-up of large primordial cells in (c). (c) Primordial cells in lower left of section of (b). These large ovoid to box-shaped cells typically have massive cell walls that appear to be a combination of inner cell wall and interfilament, crystals (ClEx 41 2hl). (d) Partially regrown scar (∼400 µm at the deepest part) in C. compactum retrieved from 10 ∘C high-light tank on 1 November 2012. Left side and shallower back portion of scar have formed new perithallium directly from old, pre-scar tissue. However, deeper bottom of scar is being filled by new hypothallium being topped with new perithallium. Allowing for late August and September recovery without growth, new wound tissue represents 1–2 months' growth. Scale bars: 100 µm (a, b, d) and 10 µm (c).

Using R version 3.3.2 (R Core Team, 2016) one-way and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were performed to determine the variance between light and temperature conditions. Assumptions for ANOVA were met, and normality was verified using the Shapiro–Wilks test, and equal variance was verified with the Bartlett test. Linear regressions were used to determine temperature–MgCO3 relationships. There was only data for three temperature treatments for the medium-light conditions, instead of the four temperature treatments for high- and low-light conditions. This was addressed through the degrees of freedom associated with specific ANOVA tests used to determine each p value.

Figure 10Examples of wound recovery during dark calcification. (a) Wound tissue recovery after 2 months in dark conditions. Primordial cells, perithallial cells, meristem cells and two to three epithallial cells appear similar to those shown in Fig. 9a–c for lighted wound recovery tissues (ClEx 71 4dk). (b) Similar wound recovery after 1 month of growth in the dark. There are fewer cells, with only few meristem cells apparent as compared to (a); rectangle indicates area magnified in (c) (ClEx 31 4dk). (c) Magnification section of (b) showing three meristem and two new epithallial cells being initiated (ClEx 31 4dk). (d) Section of 1-month dark groove developing new tissues. Meristem cells are in process of developing along with one or two epithallial cells. Note clear development of interfilament, even at this early stage, along with standard radial inner-wall crystals (ClEx 41 4dk). (e) Normal upper perithallial tissue from 4 ∘C tank after 2 months of dark growth (meristem cell in upper left) showing extensive, normal diagonal interfilament crystals developed in the dark (ClEx 71 4dk). (f) Surface view of part of scar made on 1 May 2013, when specimen was placed in dark chamber of 4 ∘C tank. Collected on 1 July 2013, large cells visible on mid-slope lateral surfaces of scar are recovering primordial cells. Lateral to groove, on normal tissue, right and left, overlying epithallial tissue can be seen to be heavily grazed by chitons in form of en-echelon, fine grooves (ClEx 71 4dk). Scale bars: 2 µm (e), 10 µm (a, c, d), and 100 µm (b, f).

3.1 Sample growth during experiment

3.1.1 Wound recovery from scars as indicator for algal growth characteristics/cellular structure

Development of characteristic wound tissue from sub-scar pre-existing perithallial tissue occurred to a depth of approximately 400 µm (Fig. 9d). After the formation of several primordial wound repair cells, a new intercalary meristem forms, gradually returning the wound tissues to normal perithallial tissue, and starch grains as stored food are present in all stages of the experiment including in samples grown in the dark. Occasionally when the scars were deeper, lateral secondary hypothallial growth developed to partially refill the base of the wound (Fig. 9d). Direct perithallial regrowth of scar tissue in almost all cases, both marginally and vertically, was typically initiated by one or several very large primordial cells, with massive calcified cell walls (Figs. 10f, 9a–c).

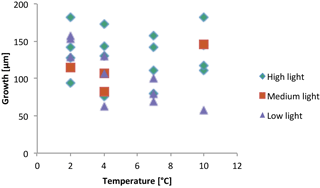

Figure 11Total perithallial growth during experiment of samples harvested at end of experiment; multiple transects from individuals were averaged.

Until the meristem and sufficient photosynthetic epithallial tissue is formed, development and growth must be sustained by transfer of photosynthate from elsewhere in the crust, either as storage food from old perithallial tissue lying below or as newly produced photosynthate from undamaged epithallial tissues beyond the wound. Therefore growth and calcification in these newly formed tissues must be metabolically driven. The mean growth of scar tissue during the course of this experiment from subjects in all temperature and all light conditions combined was 42 µm month−1 (Table 4). Specimens lacking apparent recovery (zeros) were not included in the summation, since the possibility of grazing, as a factor external to growth, cannot be excluded. This compares with the expected mean monthly growth rate of specimens at the Bay Bulls site of approximately 24 µm month−1 (Halfar et al., 2011b). Total normal perithallial growth during the experiment of the subjects harvested in July ranged from 58 to 182 µm (Fig. 11).

Table 4ClEx wound (scar) regrowth (thickness of new growth µm month−1 for growth (month)). Extensive chiton grazing of groove marked with *; conceptacles present marked with +. Specimens lacking apparent recovery (zeros) were not included in the summation, since the possibility of grazing, as a factor external to growth, cannot be excluded.

In addition to artificial scarring, chiton-inflicted grazing deeper than epithallium and apparently also into the recovering wound tissue and developing conceptacles was encountered during the experiment (Table 4). Generally, chitons took up daytime residence beneath each subject and came out to graze the surface at night. The graze marks of these animals are seen in appropriately oriented specimens (Fig. 10f). The development of asexual conceptacles in the experiment – beginning in the autumn and reaching maturity by mid-winter, just as in the wild (Adey, 1965) – occurred within the experimental system. Mature and maturing conceptacles were widely spread over the temperature and light range employed, and were commonly found in these experimental specimens (Fig. S2a and b), as well as signs of grazing, through the epithallium and overlying conceptacle roof tissue, into the conceptacle cavities (Fig. S2c). Two-thirds of the noted significant grazing, including both wound tissue and conceptacles, occurred in the 10 ∘C tank (Table 4), suggesting that at higher temperatures, out of phase with conceptacle development (normally autumn and winter), chiton grazing could significantly affect reproduction. The high dominance of observed chiton grazing occurring in the 10 ∘C tank suggests that temperature control of chiton activity is important. However, with no predators (especially small starfish) in the experimental system, chitons may well have been more active than in the wild.

3.1.2 Dark growth and calcification

Four specimens from each of the experimental tanks, all from the low-light sections of the tanks, were re-scarred, near the earlier collection scar and placed in dark chambers at the opaque back of each tank on 1 February and 1 May 2013. Of the 16 subjects placed in the dark, after collection nine were sectioned and examined in SEM for new growth in the dark. Of those SEM samples, three were covered with detritus in the crucial scar section, and SEM observations of potential new growth could not be carried out; three showed no apparent regrowth (although chiton grazing might have removed such growth); and three presented a good section and images in SEM and were capable of reliably providing a recording of dark growth. Specimens from the 4 ∘C tank placed in the dark and collected after 1 month were sectioned and examined with SEM. Two of these specimens presented the distinctive scar (wound) regrowth (Fig. 10a–c). An additional specimen – taken from the low light level of the 4 ∘C tank, placed in a dark chamber for 2 months, and manipulated similarly to the samples left in the dark for 1 month – also showed distinctive scar regrowth (Figs. 9c, 10d).

Wound recovery, both in the light and dark, was initiated with large primordial cells and several typical wound repair cells, followed by the development of typical anatomical tissue with the formation of perithallium, meristem, and epithallium cells (Fig. 9). Calcification in the newly formed tissues, with both radial inner-wall calcite and large diagonal interfilament crystals, is quite similar to that in lighted, wound regrowth tissue and in normal tissue (Fig. 10b, c, e). The full thickness of interfilament calcite that is often viewed in mature summer growth of normal vegetative tissues of C. compactum, and seen in lighted scar regrowth (Fig. 10e), has not developed in these dark specimens (Fig. S2a). All three specimens that showed regrowth in the dark came from the 4 ∘C experimental tank. The average rate of wound regrowth measured in these dark specimens, at 30 µm month−1, is considerably less than the 51 µm month−1 mean found in all lighted wound regrowth in the 4 ∘C tank (Table 4). In addition, it is unlikely that the experimental scarring affected later growth because the typical specimen used in the study was about 4 cm in diameter, while the scars were about 1 mm wide and 4 mm long. The entire photosynthetic surface of the typical specimen was about 1200 mm2, and the scar less than 4 mm2, about 1∕400th of the surface. Since lateral translocation in the shallow coralline crust is widespread (Adey et al., 2018), it seems further unlikely that the scar would have affected growth following wound repair growth. In addition, the second scarring, typically placed about 1 cm from the initial scar, took place 6–9 months after the first, making it unlikely that the first scarring affected growth in the second, dark experiment. In short, while dark wound regrowth occurs and appears to have all the anatomical and calcified cell wall features of normal wound repair tissues, growth rates, at the same temperature, appear to be slower.

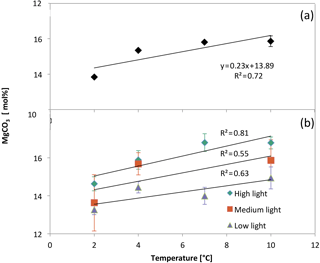

3.2 Effects of temperature and light on algal MgCO3

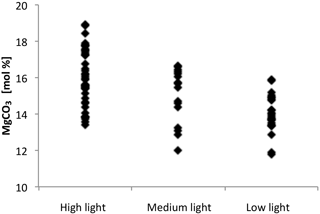

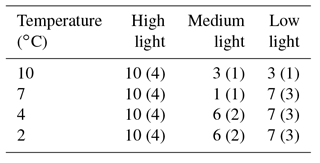

The MgCO3 of samples from high-light treatments had the most significant correlation with temperature (ANOVA: variation within the samples; , p<0.001; Fig. 12b), and the relationship weakened with diminishing light levels: medium light (, p=0.03) and low light (, p=0.05). In addition, there was no statistically significant interaction between light and temperature (two-way ANOVA; , p=0.5).

Figure 12(a) Electron-microprobe-derived MgCO3 concentrations (± standard error) of each temperature treatment group after averaging all light levels. (b) Electron-microprobe-derived MgCO3 concentrations (± standard error) of each temperature/light treatment group.

3.2.1 Temperature

When all of the light treatments were averaged together, the relationship between MgCO3 and temperature was stronger than any of the individual light levels (, p<0.001) (Fig. 12a). In addition, the standard error of MgCO3 of each of the temperature treatments was smaller than when the light treatments were separated. This was due to an increase in the sample size.

3.2.2 Light

In addition to a significant relationship between MgCO3 and temperature, there was also a significant relationship between light levels and MgCO3 from all temperatures combined (, p<0.001) (Fig. 13). Therefore, the linear regression equation of MgCO3 for each light treatment was different, and the high-light samples showed the most temperature sensitivity (steepest slope). In every temperature treatment more light resulted in higher MgCO3 (Fig. 12b). The regressions were as follows.

4.1 Algal growth characteristics determined from wound recovery

Mean all-temperature, all-light vertical growth of scar (wound) tissue during the course of this experiment was 42 µm month−1. This would provide a yearly growth rate of about 500 µm, compared with the expected mean monthly growth rate of specimens at the Bay Bulls site of approximately 287 µm yr−1 (24 µm month−1) (Halfar et al., 2011b). As shown in Fig. 11, total perithallial growth during the experiment ranged from about 80 to 270 µm (depending on light level) for an approximate period of 8 months (allowing 1.5 months for specimen acclimatization), or approximately 120–400 µm per year. Thus, the growth rate values found in this study are well within the expected range in the wild. Beginning 6 months into the experiment, fully grown-in grooves began to be seen. This suggests an even greater differential between wound recovery rate and expected whole-crust growth rate. Unfortunately, in this experiment, it was not possible to consistently achieve a tank temperature below 2 ∘C. Most C. compactum populations are in localities that reach 0 ∘C or below during the winter. Thus, tank growth could not be precisely compared with wild growth. Clearly, the relatively rapid rate of wound recovery is necessary if an even surface on C. compactum mounds is to be maintained and detritus accumulation avoided. Such recovery from wounding and conceptacle breakout is frequently seen in wild-collected specimens (Adey et al., 2013). Chiton grazing is likely a factor in the delay or absence of scar tissue in some plants. However, rapid wound recovery demonstrates that temperature and light do not provide short-term controls on growth and calcification rates.

Growth and calcification are clearly metabolically driven; when a wounded crust can draw upon photosynthates, stored or in photosynthetic production, from other parts of the crust, higher rates than normal vegetative growth under given temperature/light conditions are achievable. Arctic/subarctic C. compactum crusts must store photosynthate for an extended dark season. The growth rate that can be accomplished in the short term, to repair damage using stored energy, is clearly not an option for normal vegetative crust growth. Normal crust vegetative growth, with energy supplied from epithallial photosynthesis, must provide not only for local growth but also for annual reproduction, lateral growth, and wound repair. Thus, the wound repair rates seen here are higher than the month-to-month growth potential of C. compactum as controlled by light and temperature and abundantly provided in the literature (Adey et al., 2015).

4.2 Dark growth and calcification

This experiment has demonstrated a strong connection between light and MgCO3, while Nash and Adey (2017) have shown Mg control only by temperature. However, in the latter study, light was not a control, other than as a basic metabolic requirement. Our experiment demonstrated that growth, with the full complex of cell wall calcification, can occur without simultaneous light, presumably as long as stored photosynthate is available.

Figure 14Annual cycles of MgCO3 content of C. compactum mound from 15 to 20 m in the Kingitok Islands in north-central Labrador. Cycles show V-shaped pattern, indicating growth halt during winter. Water temperature at Kingitok is below 0 ∘C for over 200 days per year, and sea surface is typically frozen from early December to late June (Adey et al., 2015).

Calcification in the dark indicates that photosynthesis is not the direct driver of calcification by altering local chemistry. The availability of stored food previously formed by photosyntheses, growth, and calcification is driven metabolically. The initiation of the calcite crystal formation cannot be dependent on photosynthetically elevated pH, as has been proposed in various studies. C. compactum specimens grown in the wild under Arctic conditions of 6 months of darkness consistently show a sharp downward spike in Mg content at the equivalent of 0 to −1.8 ∘C water temperature (Fig. 14). Full darkness, often under ice cover, occurs before the temperature reaches its lower limits on the bottom where the plants are growing. To produce carbonate with MgCO3 ratios equivalent to a water temperature of −1 ∘C, growth has to have occurred in dark conditions for some period of time. As we see from this experiment, growth could proceed for at least 2 months before likely ceasing when sufficient stored photosynthate is exhausted.

4.3 Light and temperature

Results show that both light and temperature significantly affect magnesium in C. compactum crusts. At lower temperatures (2 ∘C) the effects of light are relatively small, relating to a 1.4 mol % MgCO3 (corresponding to 8.75 ∘C on the low-light curve and 5.4 ∘C on the high-light curve) increase from low to high light. Differences become larger at higher temperatures (10 ∘C), where MgCO3 increases by 1.8 mol % (corresponding to 11.25 ∘C on the low-light curve and 6.9 ∘C on the high-light curve) from low to high light levels. Also, at higher light levels R2 values indicate a stronger correlation between MgCO3 and temperature (Fig. 12b). These observations suggest that light and temperature both result in an increase in MgCO3 and growth, with the effects of light being more significant at higher temperatures as shown previously for other coralline species (Adey, 1970).

4.4 Implications for proxy

Results show that, although temperature is a major factor contributing to C. compactum MgCO3 incorporation, light must be considered when using C. compactum as a proxy. Our findings suggest that a global MgCO3–temperature calibration cannot be produced for C. compactum, because light levels and shading contribute to differences in MgCO3 within individuals or a large sample. The highest correlation between temperature and MgCO3 was found when all experimental samples were combined regardless of light level, suggesting that due to inter- and intra-sample variability replication is very important when generating temperature reconstructions, rather than attempting to collect all samples from similar light conditions. The need for replication caused by inter-specimen differences has also been highlighted in several studies of Clathromorphum sp. (Hetzinger et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2014, 2018).

The effects of light on MgCO3 may explain differences in Mg ∕ Ca of samples collected from the same site and water depth found in several C. compactum climate reconstruction studies (Chan et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2014). Differential shading can be due to temporary macroalgal overgrowth or the position of the coralline algae, such as under a ledge or orientation with respect to the surface. In these cases, differing light levels would necessitate sample-specific calibrations. This would imply calibrating Mg ∕ Ca for each individual sample with known in situ temperature before averaging all samples to create a record. Applying this method could prevent outlier samples that may have experienced significantly different light levels from having an effect on the proxy reconstruction.

Experiment results also support the use of C. compactum as a sea ice proxy, because Mg ∕ Ca is driven by both light and temperature. Changes in light duration on the Arctic seafloor are related to sea ice and thus to coralline algal Mg ∕ Ca. C. compactum is especially suited as a sea ice proxy because it is the only high-resolution shallow-marine archive found in seasonally ice-covered regions of the Arctic, including the Greenland coast (Jørgensbye and Halfar, 2016), the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, northern Labrador (Halfar et al., 2013), Novaya Zemlya (Adey et al., 2015b), and Svalbard (Wisshak et al., 2016).

While the findings of this experiment should inform the use of replication and calibration of individual samples to improve the use of C. compactum as a climate proxy, they do not discount the results of past environmental reconstructions using this species. For example, Williams et al. (2014) used Clathromorphum sp. to reconstruct past temperature and tested the calibration between Mg ∕ Ca and instrumental temperature of each sampling location. Also, Halfar et al. (2013) combined annual growth and Mg ∕ Ca concentrations from C. compactum to reconstruct sea ice conditions, based on the assumption that these records respond to both light and temperature. While the influence of both light and temperature on growth rates of several species of corallines has already been demonstrated (Adey, 1970), their influences on Mg have now also been confirmed. Based on our findings, the results of past studies would only be untrustworthy if a calibration from another study or location was used to convert Mg ∕ Ca to temperature without confirming this relationship.

C. compactum produces its normal range of tissues with similarly complex high-magnesium calcitic wall structures both in the light and in the dark. Growth and calcification occur for at least 2 months in the dark, presumably following the exhaustion of stored photosynthate. Following the formation of a few distinctive initial primordial and transition cells, wound repair (scar) tissue is similar to normal perithallial tissue, although wound repair tissue grows at significantly greater rates than normal tissue. Since the autumn/winter formation of reproductive structures (conceptacles) requires vegetative tissue growth and calcification of surrounding vegetative tissues, calcification in the dark allows for the survival of C. compactum under sea ice cover and in Arctic winter darkness. Both light and temperature significantly affect the incorporation of MgCO3 in C. compactum calcitic cell wall structures. At lower temperatures the effects of light are slightly smaller than at higher temperatures. Also, the correlation between MgCO3 and temperature is stronger at higher light levels than at low light. When generating proxy temperature reconstructions using Clathromorphum species, site- and possibly specimen-specific temperature calibrations need to be applied in order to take into account the effects of light. Corallines, including Clathromorphum species, can be successfully grown in the laboratory and used for critical experimentation. However, they are complex organisms with equally complex ecological relationships, and mesocosms, rather than simple aquaria, are required to produce reliable experimental results (Adey and Loveland, 2007; Small and Adey, 2001).

Underlying research data can be accessed at http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1419109 (Williams et al., 2018 ).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-5745-2018-supplement.

WA, PG, and DB planned this study; WA, PG, and DB set up the experiment; and PG and DB ran the experiment. SW, WA, AK, and MN analysed the samples, and SW and WA processed the data. SW and WA led the writing of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to discussions in writing this manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This work was funded by the Centre for Global Change Science, the Geological

Society of America, a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of

Canada Discovery Grant to Jochen Halfar, and the Smithsonian Institution and Ecological

Systems Technology.

Edited by: Hiroshi Kitazato

Reviewed by: two anonymous referees

Adey, W. H.: The genus Clathromorphum (Corallinaceae) in the Gulf of Maine, Hydrobiologia, 539–573, available from: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00045545 (last access: 15 May 2014), 1965.

Adey, W. H.: The effects of light and temperature on growth rates in Boreal-Subarctic crustose corallines, J. Phycol., 9, 269–276, 1970.

Adey, W. H.: Temperature control of reproduction and productivity in a subarctic coralline alga, Phycologia, 12, 111–118, 1973.

Adey, W. H.: Review Coral Reefs: Algal Structured and Mediated Ecosystems in Shallow, Turbulent, Alkaline Waters, J. Phycol., 406, 393–406, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1529-8817.1998.340393.x, 1998.

Adey, W. H. and Hayek, L.-A. C.: Elucidating marine biogeography with macrophytes: quantitative analysis of the North Atlantic supports the thermogeographic model and demonstrates a distinct subarctic region in the Northwestern Atlantic, Northeast. Nat., 18, 1–128, https://doi.org/10.1656/045.018.m801, 2011.

Adey, W. H. and Loveland, K.: Dynamic aquaria?: building and restoring living ecosystems, Academic, available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/book/9780123706416 (last access: 20 January 2018), 2007.

Adey, W. H., Chamberlain, Y. M., and Irvine, L. M.: An SEM-based analysis of the morphology, anatomy, and reproduction of Lithothamnion tophiforme (Esper) unger (Corallinales, Rhodophyta), with a comparative study of associated North Atlantic arctic/subarctic melobesioideae, J. Phycol., 41, 1010–1024, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00123.x, 2005.

Adey, W. H., Halfar, J., and Williams, B.: The coralline genus Clathromorphum Foslie emend. Adey, Smithson. Contrib. Mar. Sci., 40, 1–41, 2013.

Adey, W., Halfar, J., Humphreys, A., Suskiewicz, T., Belanger, D., Gagnon, P., and Fox, M.: Subarctic rhodolith beds promote longevity of crustose coralline algal buildups and their climate archiving potential, Palaios, 30, 281–293, https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2014.075, 2015a.

Adey, W. H., Hernandez-Kantun, J. J., Johnson, G., and Gabrielson, P. W.: DNA sequencing, anatomy, and calcification patterns support a monophyletic, subarctic, carbonate reef-forming Clathromorphum (Hapalidiaceae, Corallinales, Rhodophyta), J. Phycol., 51, 189–203, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpy.12266, 2015b.

Adey, W. H., Hernandez-Kantun, J. J., Gabrielson, P. W., Nash, M. C., and Hayek, L. C.: Phymatolithon (Melobesioideae, Hapalidiales) in the Boreal-Subarctic transition zone of the North Atlantic: a correlation of plastid DNA markers with morpho-anatomy, ecology and biogeography, Smithson. Contrib. Mar. Sci., April, The journal name is: Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences, 41, 2018.

Burdett, H., Kamenos, N. A., and Law, A.: Using coralline algae to understand historic marine cloud cover, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 302, 65–70, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.07.027, 2011.

Chan, P., Halfar, J., Williams, B., Hetzinger, S., Steneck, R. S., Zack, T., and Jacob, D. E.: Freshening of the Alaska Coastal Current recorded by coralline algal Ba ∕ Ca ratios, J. Geophys. Res., 116, G01032, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JG001548, 2011.

Gamboa, G., Halfar, J., Hetzinger, S., Adey, W. H., Zack, T., Kunz, B. E., and Jacob, D. E.: Mg ∕ Ca ratios in coralline algae record northwest Atlantic temperature variations and North Atlantic Oscillation relationships, J. Geophys. Res., 115, C12044, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JC006262, 2010.

Halfar, J., Steneck, R. S., Joachimski, M., Kronz, A., and Wanamaker, A. D.: Coralline red algae as high-resolution climate recorders, Geology, 36, 463–466, 2008.

Halfar, J., Williams, B., Hetzinger, S., Steneck, R. S., Lebednik, P. A., Winsborough, C., Omar, A., Chan, P., and Wanamaker, A. D.: 225 years of Bering Sea climate and ecosystem dynamics revealed by coralline algal growth-increment widths, Geology, 39, 579–582, https://doi.org/10.1130/G31996.1, 2011a.

Halfar, J., Hetzinger, S., Adey, W. H., Zack, T., Gamboa, G., Kunz, B. E., Williams, B., and Jacob, D. E.: Coralline algal growth-increment widths archive North Atlantic climate variability, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 302, 71–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.04.009, 2011b.

Halfar, J., Adey, W. H., Kronz, A., Hetzinger, S., Edinger, E., and Fitzhugh, W. W.: Arctic sea-ice decline archived by multicentury annual-resolution record from crustose coralline algal proxy, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 110, 1973736–1973741, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1313775110, 2013.

Hetzinger, S., Halfar, J., Kronz, A., Steneck, R. S., Adey, W. H., Lebednik, P. A., and Schöne, B. R.: High-resolution Mg ∕ Ca ratios in a coralline red alga as a proxy for Bering Sea temperature variations from 1902 to 1967, Palaios, 24, 406–412, https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2008.p08-116r, 2009.

Hetzinger, S., Halfar, J., Kronz, A., Simon, K., Adey, W. H., and Steneck, R. S.: Reproducibility of Clathromorphum compactum coralline algal Mg ∕ Ca ratios and comparison to high-resolution sea surface temperature data, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 220, 96–109, 2018.

Jørgensbye, H. I. Ø. and Halfar, J.: Overview of coralline red algal crusts and rhodolith beds (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) and their possible ecological importance in Greenland, Polar Biol., 40, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-016-1975-1, 2016.

Kamenos, N. A., Cusack, M., and Moore, P. G.: Coralline algae are global palaeothermometers with bi-weekly resolution, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 72, 771–779, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2007.11.019, 2008.

Moberly, R. J.: Composition of magnesian calcites of algae and pelecypods by electron microprobe analysis, Sedimentology, 11, 61–82, 1968.

Nash, M. C. and Adey, W.: Multiple phases of mg-calcite in crustose coralline algae suggest caution for temperature proxy and ocean acidification assessment: lessons from the ultrastructure and biomineralization in Phymatolithon (Rhodophyta, Corallinales), edited by: Hurd, C., J. Phycol., 53, 970–984, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpy.12559, 2017.

Nash, M. C. and Adey, W.: Anatomical structure overrides temperature controls on magnesium uptake – calcification in the Arctic/subarctic coralline algae Leptophytum laeve and Kvaleya epilaeve (Rhodophyta; Corallinales), Biogeosciences, 15, 781–795, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-781-2018, 2018.

R Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, available from: http://www.R-project.org, 2016.

Williams, S., Adey, W., Halfar, J., Kronz, A., Gagnon, P., Bélanger, D., and Nash, M.: Clathromorphum light/temperature experiment data, available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1419109TS2, last access: 19 September 2018.

Small, A. M. and Adey, W. H.: Reef corals, zooxanthellae and free-living algae: A microcosm study that demonstrates synergy between calcification and primary production, Ecol. Eng., 16, 443–457, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-8574(00)00066-5, 2001.

Steneck, R. S.: A limpet-coralline algal association:adaptations and defenses between a selective herbivore and its prey, Ecology, 63, 507–522, 1982.

Teichert, S. and Freiwald, A.: Polar coralline algal CaCO3-production rates correspond to intensity and duration of the solar radiation, Biogeosciences, 11, 833–842, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-833-2014, 2014.

Teichert, S., Woelkerling, W. J., Rüggeberg, A., Wisshak, M., Piepenburg, D., Meyerhöfer, M., Form, A., and Freiwald, A.: Arctic rhodolith beds and their environmental controls (Spitsbergen, Norway), Facies, 60, 15–37, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10347-013-0372-2, 2013.

Williams, B., Halfar, J., DeLong, K. L., Hetzinger, S., Steneck, R. S., and Jacob, D. E.: Multi-specimen and multi-site calibration of Aleutian coralline algal Mg ∕ Ca to sea surface temperature, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 139, 190–204, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2014.04.006, 2014.

Williams, S., Halfar, J., Zack, T., Hetzinger, S., Blicher, M., and Juul-Pedersen, T.: Comparison of climate signals obtained from encrusting and free-living rhodolith coralline algae, Chem. Geol., 476, 418–428, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2017.11.038, 2018.

Wisshak, M., Bartholomä, A., Beuck, L., Büscher, J., Form, A., Freiwald, A., Halfar, J., Hetzinger, S., Heugten, B. van, Hissmann, K., Holler, P., Meyer, N., Neumann, H., Raddatz, J., Rüggeberg, A., Teichert, S., and Wehrmann, A.: Habitat characteristics and carbonate cycling of macrophyte-supported polar carbonate factories (Svalbard) – Cruise No. MSM55 – June 11–June 29, 2016 – Reykjavik (Iceland) – Longyearbyen (Norway), 2017.