the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Effect of elevated pCO2 on trace gas production during an ocean acidification mesocosm experiment

Sheng-Hui Zhang

Juan Yu

Qiong-Yao Ding

Kun-Shan Gao

Hong-Hai Zhang

Da-Wei Pan

A mesocosm experiment was conducted in Wuyuan Bay (Xiamen), China, to investigate the effects of elevated pCO2 on the phytoplankton species Phaeodactylum tricornutum (P. tricornutum), Thalassiosira weissflogii (T. weissflogii) and Emiliania huxleyi (E. huxleyi) and their production ability of dimethylsulfide (DMS), dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), as well as four halocarbon compounds, bromodichloromethane (CHBrCl2), methyl bromide (CH3Br), dibromomethane (CH2Br2) and iodomethane (CH3I). Over a period of 5 weeks, P. tricornuntum outcompeted T. weissflogii and E. huxleyi, comprising more than 99 % of the final biomass. During the logarithmic growth phase (phase I), mean DMS concentration in high pCO2 mesocosms (1000 µatm) was 28 % lower than that in low pCO2 mesocosms (400 µatm). Elevated pCO2 led to a delay in DMSP-consuming bacteria concentrations attached to T. weissflogii and P. tricornutum and finally resulted in the delay of DMS concentration in the high pCO2 treatment. Unlike DMS, the elevated pCO2 did not affect DMSP production ability of T. weissflogii or P. tricornuntum throughout the 5-week culture. A positive relationship was detected between CH3I and T. weissflogii and P. tricornuntum during the experiment, and there was a 40 % reduction in mean CH3I concentration in the high pCO2 mesocosms. CHBrCl2, CH3Br, and CH2Br2 concentrations did not increase with elevated chlorophyll a (Chl a) concentrations compared with DMS(P) and CH3I, and there were no major peaks both in the high pCO2 or low pCO2 mesocosms. In addition, no effect of elevated pCO2 was identified for any of the three bromocarbons.

- Article

(759 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Anthropogenic emissions have increased the fugacity of atmospheric carbon dioxide (pCO2) from the pre-industrial value of 280 µatm to the present-day value of over 400 µatm, and these values will further increase to 800–1000 µatm by the end of this century (Gattuso et al., 2015). The dissolution of this excess CO2 into the surface of the ocean directly affects the carbonate system and has lowered the pH by 0.1 units, from 8.21 to 8.10 over the last 250 years. Further decreases of 0.3–0.4 pH units are predicted by the end of this century (Doney et al., 2009; Orr et al., 2005; Gattuso et al., 2015), which is commonly referred to as ocean acidification. The physiological and ecological aspects of the phytoplankton response to this changing environment can potentially alter marine phytoplankton community composition, community biomass, and feedback to biogeochemical cycles (Boyd and Doney, 2002). These changes simultaneously have an impact on some volatile organic compounds produced by marine phytoplankton (Liss et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017), including the climatically important trace gas dimethylsulfide (DMS) and a number of volatile halocarbon compounds.

DMS is the most important volatile sulfur compound produced from dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), which is ubiquitous in marine environments, mainly synthesized by marine microalgae (Stefels et al., 2007), a few angiosperms, some corals (Raina et al., 2016), and several heterotrophic bacteria (Curson et al., 2017) through complex biological interactions in marine ecosystems. Although it remains controversial, DMS and its by-products, such as methanesulfonic acid and non-sea-salt sulfate, are suspected of having a prominent part in climate feedback (Charlson et al., 1987; Quinn and Bates, 2011). The conversion of DMSP to DMS is facilitated by several enzymes, including DMSP lyase and acyl CoA transferase (Kirkwood et al., 2010; Todd et al., 2007); these enzymes are mainly found in phytoplankton, macroalgae, symbiodinium, bacteria and fungi (de Souza and Yoch, 1995; Stefels and Dijkhuizen, 1996; Steinke and Kirst, 1996; Chl a and Yoch, 1998; Yost and Mitchelmore, 2009). Several studies have shown a negative impact of decreasing pH on DMS-production capability (Hopkins et al., 2010; Avgoustidi et al., 2012; Archer et al., 2013; Webb et al., 2016), while others have found either no effect or a positive effect (Vogt et al., 2008; Hopkins and Archer, 2014). Several assumptions have been presented to explain these contrasting results and attributed the pH-induced variation in DMS-production capability to altered physiology of the algae cells or of bacterial DMSP degradation (Vogt et al., 2008; Hopkins et al., 2010, Avgoustidi et al., 2012; Archer et al., 2013; Hopkins and Archer, 2014; Webb et al., 2015).

Halocarbons also play a significant role in the global climate because they are linked to tropospheric and stratospheric ozone depletion and a synergistic effect of chlorine and bromine species has been reported, accounting for approximately 20 % of the polar stratospheric ozone depletion (Roy et al., 2011). In addition, iodocarbons can release atomic iodine quickly through photolysis in the atmospheric boundary layer and iodine atoms are very efficient in the catalytic removal of O3, which governs the lifetime of many climate-relevant gases, including methane and DMS (Jenkins et al., 1991). Compared with DMS, limited attention was received about the effect of ocean acidification on halocarbon concentrations. Hopkins et al. (2010) and Webb et al. (2015) measured lower concentrations of several iodocarbons, while bromocarbons were unaffected by elevated pCO2 in two acidification experiments. In addition, another mesocosm study did not elicit significant differences from any halocarbon compounds at up to 1400 µatm pCO2 (Hopkins et al., 2013).

Taken together, the data indicate that the response of DMS and halocarbon release to elevated pCO2 is complex and controversial. DMS and halocarbons play a significant role in the global climate and will perhaps act to a greater extent in the future. An intermediate step between laboratory and natural community field experiments was designed in this study to understand the response of the release of DMS and halocarbon to ocean acidification in Chinese coastal seas using isolates of non-axenic phytoplankton added to filtered natural water. We hypothesized that the response of DMS and halocarbon release to elevated pCO2 in natural seawater can be better presented after minimizing the shifting composition of the natural phytoplankton and microbial communities.

2.1 Experimental setup

To investigate the response of DMS and halocarbon release to ocean acidification, a mesocosm experiment was carried out on a floating platform (set in seawater, about 150 m from the shore) at the Facility for Ocean Acidification Impacts Study of Xiamen University (FOANIC-XMU; 24.52∘ N, 117.18∘ E) (for full technical details of the mesocosms, see Liu et al., 2017). Six cylindrical transparent thermoplastic polyurethane bags with domes were deployed along the southern side of the platform. The width and depth of each mesocosm bag were 1.5 and 3 m, respectively. Filtered (0.01 µm ultrafiltration water purifier, MU801-4T, Midea, Guangdong, China) in situ seawater was pumped into the six bags simultaneously within 24 h. A known amount of NaCl solution was added to each bag to calculate the exact volume of seawater in the bags, according to a comparison of the salinity before and after adding salt (Czerny et al., 2013). The initial in situ pCO2 was about 650 µatm. To set the low (400 µatm) and high pCO2 (1000 µatm) levels, we added Na2CO3 solution and CO2 saturated seawater to the mesocosm bags to alter total alkalinity and dissolved inorganic carbon (Gattuso et al., 2010; Riebesell et al., 2013). Subsequently, during the whole experimental process, air at the ambient (400 µatm) and elevated pCO2 (1000 µatm) concentrations was continuously bubbled into the mesocosm bags using a CO2 Enricher (CE-100B, Wuhan Ruihua Instrument & Equipment Ltd., Wuhan, China). Seawater taken from the coastal environment was first filtered to remove algae and their attached bacteria before usage in mesocosm bags. Bacterial abundance in the pre-filtered water was less than 103 cell mL−1, which was 3 magnitudes lower than the bacterial abundance in the natural water and close to the detection limit of the flow cytometer. The trace gases, including DMS, bromodichloromethane (CHBrCl2), methyl bromide (CH3Br), dibromomethane (CH2Br2), and iodomethane (CH3I) produced in the environment, did not affect the mesocosm trace gas concentrations after the bags were sealed.

2.2 Algal strains

Before being introduced into the mesocosms, the three phytoplankton species Phaeodactylum tricornutum (P. tricornutum), Thalassiosira weissflogii (T. weissflogii) and Emiliania huxleyi (E. huxleyi) were cultured in autoclaved, pre-filtered seawater from Wuyuan Bay at 16 ∘C (similar to the in situ temperature of Wuyuan Bay) without any addition of nutrients. Cultures were continuously aerated with filtered ambient air containing 400 µatm of CO2 within plant chambers (HP1000G-D, Wuhan Ruihua Instrument & Equipment, China) at a constant bubbling rate of 300 mL min−1. The culture medium was renewed every 24 h to maintain the cells of each phytoplankton species in exponential growth. When the experiment began, these three phytoplankton species were inoculated into the mesocosm bags, with an initial diatom/coccolithophorid cell ratio of 1:1. The initial concentrations of P. tricornuntum, T. weissflogii, and E. huxleyi inoculated into the mesocosm were 10, 10, and 20 cells mL−1, respectively. P. tricornuntum and T. weissflogii were obtained from the Center for Collections of Marine Bacteria and Phytoplankton of the State Key Laboratory of Marine Environmental Science (Xiamen University). P. tricornuntum was originally isolated from the South China Sea in 2004 and T. weissflogii was isolated from Daya Bay in the coastal South China Sea. E. huxleyi was originally isolated in 1992 from the field station of the University of Bergen (Raunefjorden; 60∘18′ N, 05∘15′ E).

2.3 Sampling for DMS(P) and halocarbons

DMS(P) and halocarbon samples were taken from the above-mentioned mesocosm bags at 09:00; then all collected samples were transported into a dark cool box back to the laboratory onshore for analysis within 1 h. For the DMS analysis, a 2 mL sample was gently filtered through a 25 mm GF/F (glass fiber) filter and transferred to a purge and trap system linked to a Shimadzu GC-2014 gas chromatograph (Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a glass column packed with 10 % DEGS on Chromosorb W-AW-DMCS (3 m × 3 mm) and a flame photometric detector (Zhang et al., 2014). For total DMSP analysis, a 10 mL water sample was fixed using 50 µL of 50 % H2SO4 and sealed (Kiene and Slezak, 2006). After >1-day preservation, DMSP samples were hydrolyzed for 24 h with a pellet of KOH (final pH > 13) to fully convert DMSP to DMS. Then, 2 mL of the hydrolyzed sample was carefully transferred to the purge and trap system mentioned above for extraction of DMS. For halocarbons, a 100 mL sample was purged at 40 ∘C with pure nitrogen at a flow rate of 100 mL min−1 for 12 min using another purge and trap system coupled to an Agilent 6890 gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with an electron capture detector (ECD) as well as a 60 m DB-624 capillary column (0.53 mm ID; film thickness, 3 µm) (Yang et al., 2010). The analytical precision for duplicate measurements of DMS(P) and halocarbons was >10 %.

2.4 Measurements of chlorophyll a

Chlorophyll a (Chl a) was measured in water samples (200–1000 mL) collected every 2 days at 09:00 by filtering onto Whatman GF/F filters (25 mm). The filters were placed in 5 mL 100 % methanol overnight at 4 ∘C and centrifuged at 5000 g for 10 min. The absorbance of the supernatant (2.5 mL) was measured from 250 to 800 nm using a scanning spectrophotometer (DU 800, Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA, USA). Chl a concentration was calculated according to the equation reported by Porra (2002).

2.5 Enumeration of DMSP-consuming bacteria

The number of DMSP-consuming bacteria in the mesocosms was estimated using the most probable number methodology. The medium consisted of a mixture (1:1 v∕v) of sterile artificial seawater and a mineral medium (Visscher et al., 1991), 3 mL of which was dispensed into 6 mL test tubes, which were closed by an over-sized cap, allowing gas exchange. Triplicate dilution series were set up. All test tubes contained 1 mmol L−1 DMSP as the sole organic carbon source and were kept at 30 ∘C in the dark. After 2 weeks, the presence/absence of bacteria in the tubes was verified by DAPI staining (Porter and Feig, 1980). Three tubes containing 3 mL ASW without substrate were used as controls.

2.6 Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Tukey's test, and the two-sample t test were carried out to demonstrate the differences between treatments. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant. Relationships between DMS(P), halocarbons and a range of other parameters were detected using Pearson's correlation analysis via SPSS 22.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

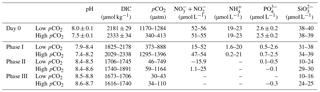

Table 1Dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), pH, pCO2 and nutrient concentrations in the mesocosm experiments. “–” means that the values were below the detection limit.

3.1 Temporal changes in pH, Chl a, P. tricornuntum, T. weissflogii, and E. huxleyi during the experiment

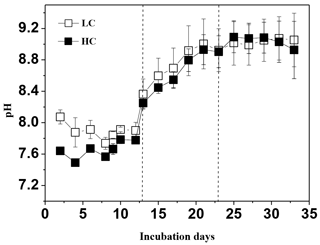

During the experiment, the seawater in each mesocosm was well mixed, and the temperature and salinity remained stable, with means of 16 ∘C and 29, respectively, in all mesocosm bags. We observed significant differences in pH levels between the two CO2 treatments on days 0–11, but the differences disappeared with subsequent phytoplankton growth (Fig. 1). The phytoplankton growth process was divided into three phases in terms of variations in Chl a concentrations in the mesocosm experiments as described in Liu et al. (2017): (i) the logarithmic growth phase (phase I, days 0–13), (ii) a plateau phase (phase II, days 13–23, bloom period), and (iii) a secondary plateau phase (phase III, days 23–33) attained after a decline in biomass from a maximum in phase II. The initial chemical parameters of the mesocosm experiment are shown in Table 1. The initial mean dissolved nitrate (including and ), , and silicate () concentrations were 54, 20, 2.6 and 41 µmol L−1, respectively, for the low pCO2 treatment and 52, 21, 2.4 and 38 µmol L−1, respectively, for the high pCO2 treatment. The nutrient concentrations (, , and phosphate) during phase I were consumed rapidly and their concentrations were below or close to the detection limit during phase II (Table 1). was detectable during the entire experimental period, and was unlikely to be a limiting factor for phytoplankton growth during the experiment. In addition, although dissolved inorganic nitrogen (, , and ) and phosphate were depleted, Chl a concentration in both treatments (biomass dominated by P. tricornuntum) remained constant over days 12–22, and then declined over subsequent days. T. weissflogii was found throughout the entire period in each bag, but the maximum concentration was 8120 cells mL−1, which was far less than the concentration of P. tricornutum with a maximum density of about 1.5 million cells mL−1 (Liu et al., 2017). It is possible that P. tricornutum outcompeted T. weissflogii because of its higher surface-to-volume ratio and/or species-specific physiology, which would enhance the efficiency of nutrient uptake and related metabolism (Alessandrade et al., 2007). E. huxleyi was only found in phase I and its maximal concentration reached 310 cells mL−1 according to the results of Liu et al. (2017). Previous studies have reported that the maximum specific growth rate of T. weissflogii and P. tricornutum is about 1.2 d−1 (Li et al., 2014; Sugie and Yoshimura, 2016), while that of E. huxleyi is about 0.8 d−1 (Xing et al., 2015). This might be the main reason why diatoms overwhelmingly outcompeted the coccolithophores during this experiment.

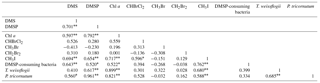

Table 2Correlation between dimethylsulfide (DMS), dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), chlorophyll a (Chl a), bromodichloromethane (CHBrCl2), methyl bromide (CH3Br), dibromomethane (CH2Br2), iodomethane (CH3I), DMSP-consuming bacteria, Thalassiosira weissflogii (T. weissflogii) and Phaeodactylum tricornutum (P. tricornutum) concentrations in the low pCO2 treatments.

∗ Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed). Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

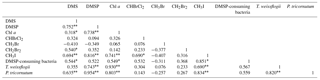

Table 3Correlation between dimethylsulfide (DMS), dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), chlorophyll a (Chl a), bromodichloromethane (CHBrCl2), methyl bromide (CH3Br), dibromomethane (CH2Br2), iodomethane (CH3I), DMSP-consuming bacteria, Thalassiosira weissflogii (T. weissflogii) and Phaeodactylum tricornutum (P. tricornutum) concentrations in the high pCO2 treatments.

∗ Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed). Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

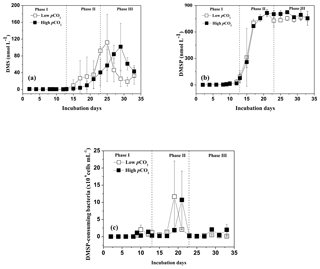

3.2 Impact of elevated pCO2 on DMS and DMSP production

DMSP concentrations in the high pCO2 and low pCO2 treatments increased significantly along with the increase in Chl a concentrations and algal cells, and remained relatively constant over the following days. A significant positive relationship was observed between DMSP and phytoplankton in the experiment (r=0.961, p<0.01 for P. tricornuntum, r=0.617, p<0.01 for T. weissflogii in the low pCO2 treatment, Table 2; r=0.954, p<0.01 for P. tricornuntum, r=0.743, p<0.01 for T. weissflogii in the high pCO2 treatment, Table 3). DMS was maintained at a low level during phase I (mean of 1.03 nmol L−1 in the low pCO2 and 0.74 nmol L−1 in the high pCO2 treatments, respectively) compared with DMSP. DMS concentrations began to increase rapidly on day 15, peaked on day 25 in the low pCO2 treatment (112.1 nmol L−1) and on day 29 in the high pCO2 treatment (101.9 nmol L−1), respectively, and then decreased in the following days. A moderate positive relationship was observed between DMS and P. tricornuntum (r=0.560, p<0.05 in the low pCO2 treatment; r=0.635, p<0.01 in the high pCO2 treatment), while no relationship was observed between DMS and T. weissflogii (Tables 2 and 3) during the experiment. Similar to DMS, DMSP-consuming bacteria also maintained a low level during phase I (mean of 0.57 × 106 and 0.40 × 106 cells mL−1 in the low pCO2 and high pCO2 treatments, respectively). DMSP-consuming bacterial concentrations peaked on days 19 (11.65 × 106 cells mL−1) and 21 (10.70 × 106 cells mL−1) in the low pCO2 and high pCO2 treatments, respectively.

Figure 2Temporal development in dimethylsulfide (DMS), dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) and DMSP-consuming bacteria concentrations in the high pCO2 (1000 µatm, black squares) and low pCO2 (400 µatm, white squares) mesocosms. Data are mean ± SD, n=3 (triplicate independent mesocosm bags).

In this study, no difference in mean DMSP concentrations was observed between the two treatments, indicating that elevated pCO2 had no significant influence on DMSP production in P. tricornuntum and T. weissflogii. However, significant reductions in mean DMS concentration (28 %) and DMSP-consuming bacteria (29 %) were detected during phase I in the high pCO2 treatment compared with those in the low pCO2 treatment, indicating that elevated pCO2 inhibited DMSP-consuming bacteria and DMS production during the logarithmic growth phase. In addition, the peak DMS concentration in the high pCO2 treatment was delayed 4 days relative to that in the low pCO2 treatment during phase II (Fig. 2a). This result has been observed in previous mesocosm experiments and it was attributed to small-scale shifts in community composition and succession (Vogt et al., 2008; Webb et al., 2016). However, this phenomenon during the present study can be explained in another straightforward way. Previous studies have shown that marine bacteria play a key role in DMS production, and that the efficiency of bacteria converting DMSP to DMS may vary from 2 to 100 % depending on the nutrient status of the bacteria and the quantity of dissolved organic matter (Simó et al., 2002, 2009; Kiene et al., 1999, 2000). In addition, a significant positive relationship was observed between DMS and DMSP-consuming bacteria (r=0.643, p<0.01 in the low pCO2 treatment; r=0.544, p<0.01 in the high pCO2 treatment) during this experiment. All of these observations point to the importance of bacteria in DMS and DMSP dynamics. During the present mesocosm experiment, DMSP concentrations in the low pCO2 treatment decreased slightly on day 23, while the slight decrease appeared on day 29 in the high pCO2 treatment (Fig. 2b). In addition, the time that the DMSP concentration began to decrease was very close to the time when the highest DMS concentration occurred in both treatments. Similar to DMS, DMSP-consuming bacteria were also delayed in the high pCO2 mesocosm compared to those in the low pCO2 mesocosm (Fig. 2c). Taken together, we inferred that the elevated pCO2 first delayed growth of DMSP-consuming bacteria; then the delayed DMSP-consuming bacteria postponed the DMSP degradation process, and eventually delayed the DMS concentration in the high pCO2 treatment. In addition, considering that algae and bacteria in natural seawater were removed through a filtering process before the experiment (Huang et al., 2018), we further concluded that the elevated pCO2 controlled DMS concentrations mainly by affecting DMSP-consuming bacteria attached to T. weissflogii and P. tricornuntum.

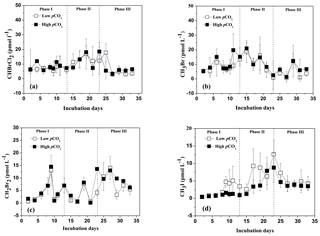

Figure 3Temporal development in bromodichloromethane (CHBrCl2), methyl bromide (CH3Br), dibromomethane (CH2Br2), and iodomethane (CH3I) concentrations in the high pCO2 (1000 µatm, black squares) and low pCO2 (400 µatm, white squares) mesocosms. Data are mean ± SD, n=3 (triplicate independent mesocosm bags).

3.3 Impact of elevated pCO2 on halocarbon compounds

The temporal development in CHBrCl2, CH3Br, and CH2Br2 concentrations is shown in Fig. 3a, b, and c, respectively. The temporal changes in their concentrations were substantially different from those in DMS, DMSP, P. tricornuntum and T. weissflogii. The mean concentrations of CHBrCl2, CH3Br, and CH2Br2 for the entire experiment were 8.58, 7.85, and 5.13 pmol L−1 in the low pCO2 treatment and 8.81, 9.73, and 6.27 pmol L−1 in the high pCO2 treatment. The concentrations of CHBrCl2, CH3Br, and CH2Br2 did not increase with the Chl a concentration compared with those of DMS and DMSP, and no major peaks were detected in the mesocosms. In addition, no effect of elevated pCO2 was identified for any of the three bromocarbons, which compared well with previous mesocosm findings (Hopkins et al., 2010, 2013; Webb et al., 2016). No clear correlation was observed between the three bromocarbons and any of the measured algal groups (Tables 2 and 3), indicating that P. tricornuntum and T. weissflogii did not primarily release these three bromocarbons during the mesocosm experiment. Previous studies reported that large-sized cyanobacteria, such as Aphanizomenon flos-aquae, could produce bromocarbons (Karlsson et al., 2008). Significant correlations between the abundance of cyanobacteria and several bromocarbons have been reported in the Arabian Sea (Roy et al., 2011). However, the filtration procedure led to the loss of cyanobacteria in the mesocosms and finally resulted in low bromocarbon concentrations during the experiment, although P. tricornuntum and T. weissflogii abundances were high.

The temporal dynamics of CH3I in the high pCO2 and low pCO2 treatments are shown in Fig. 3d. The CH3I concentrations in the low pCO2 treatment varied from 0.38 to 12.61 pmol L−1, with a mean of 4.76 pmol L−1. The CH3I concentrations in the high pCO2 treatment ranged between 0.44 and 8.78 pmol L−1, with a mean of 2.88 pmol L−1. The maximum CH3I concentrations in the high pCO2and low pCO2 treatments were both observed on day 23. The range of CH3I concentrations during this experiment was similar to that measured in the mesocosm experiment (<1–10 pmol L−1) in Kongsfjorden conducted by Hopkins et al. (2013). In addition, the mean CH3I concentration in the low pCO2 treatment was similar to that measured in the East China Sea, with an average of 5.34 pmol L−1 in winter and 5.74 pmol L−1 in summer (Yuan et al., 2016). Meanwhile, a positive relationship was detected between CH3I and Chl a, P. tricornuntum and T. weissflogii (r=0.588, p<0.01 in the low pCO2 treatment; r=0.834, p<0.01 in the low pCO2 treatment for P. tricornuntum; r=0.680, p<0.01 in the low pCO2 treatment; r=0.690, p<0.01 in the high pCO2 treatment for Thalassiosira weissflogii; r=0.717, p<0.01 in the low pCO2 treatment; r=0.741, p<0.01 in the high pCO2 treatment for Chl a). This result agrees with previous mesocosm (Hopkins et al., 2013) and laboratory experiments (Hughes et al., 2013; Manley and De La Cuesta, 1997) identifying diatoms as significant producers of CH3I. Moreover, similar to DMS, the maximum CH3I concentration also occurred after the maxima of P. tricornuntum and T. weissflogii, at about 4 days (Fig. 3d). This result was similar to the conclusions reported by Hopkins et al. (2010) and Wingenter et al. (2007) during two mesocosm experiments conducted in Norway. Their results confirmed that iodocarbon gases generally occur after the Chl a maxima. Furthermore, the mean CH3I concentration measured in the high pCO2 treatment was significantly lower (40 %) than that measured in the low pCO2 treatment during the mesocosm experiment. This result is in accordance with Hopkins et al. (2010) and Webb et al. (2015), who also reported that elevated pCO2 leads to a reduction in iodocarbon concentrations, but is in contrast to the findings of Hopkins et al. (2013) and Webb et al. (2016), who showed that elevated pCO2 does not significantly affect the iodocarbon concentrations in the mesocosms. Considering that the phytoplankton species did not show significant differences in the high pCO2 and low pCO2 treatments during the experiment, this reduction in the high pCO2 treatment was likely not caused by phytoplankton. Apart from direct biological production via methyl transferase enzyme activity by both phytoplankton and bacteria (Amachi et al., 2001), CH3I is produced from the breakdown of higher molecular weight iodine-containing organic matter (Fenical, 1982) through photochemical reactions between organic matter and light (Richter and Wallace, 2004). Both bacterial methyl transferase enzyme activity and photochemical reaction could be responsible for the reduction of CH3I concentrations in the high pCO2 treatment, but further experiments are needed to verify this result.

In this study, the effects of increased levels of pCO2 on marine DMS(P) and halocarbon release were studied in a controlled mesocosm facility. During the logarithmic growth phase, the elevated pCO2 led to a reduction in mean DMSP-consuming bacteria (29 %) and DMS concentration (28 %) compared with those in the low pCO2 treatment. In addition, a 4-day delay in DMS concentration was observed in the high pCO2 treatment due to the effect of elevated pCO2, and we attribute this delay in DMS concentration to the DMSP-consuming bacteria attached to P. tricornuntum and T. weissflogii. Due to the loss of main bromocarbon-producing species affected by the filtration procedure, three bromocarbon compounds measured in this study were not correlated with P. tricornuntum and T. weissflogii, and Chl a. In addition, elevated pCO2 had no effect on any of the three bromocarbons. The temporal dynamics of CH3I, combined with strong correlations with P. tricornuntum and T. weissflogii, and Chl a, indicate that P. tricornuntum and T. weissflogii play a critical role in controlling CH3I concentrations. In addition, the production of CH3I was sensitive to pCO2, with a significant increase in CH3I concentration at higher pCO2. However, without additional empirical measurements, it is unclear whether this decrease was caused by bacterial methyl transferase enzyme activity or by photochemical degradation at higher pCO2.

The data in this research can be accessed by sending an e-mail to gpyang@mail.ouc.edu.cn.

GPY and KSG designed the experiments. SHZ, JY and QYD carried out the experiments and prepared the manuscript. HHZ and DWP revised the paper. SHZ and JY contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 41320104008, 41576073 and 41830534), the

National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant

no. 2016YFA0601300), and the AoShan Talents Program of Qingdao National

Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (no. 2015 ASTP). We are thankful

to Minhan Dai for the nutrient data and to Bangqin Huang for the bacterial

data.

Edited by: Tina Treude

Reviewed by: Bo Qu and one anonymous referee

Alessandrade, M., Agnès, M., Shi, J., Pan, K., and Chris, B.: Genetic and phenotypic characterization of Phaeodactylum tricornutum (Bacillariophyceae) accessions. J. Phycol., 43, 992–1009, 2007.

Amachi, S., Kamagata, Y., Kanagawa, T., and Muramatsu, Y.: Bacteria mediate methylation of iodine in marine and terrestrial environments, Appl. Environ. Microb., 67, 2718–2722, 2001.

Archer, S. D., Kimmance, S. A., Stephens, J. A., Hopkins, F. E., Bellerby, R. G. J., Schulz, K. G., Piontek, J., and Engel, A.: Contrasting responses of DMS and DMSP to ocean acidification in Arctic waters, Biogeosciences, 10, 1893–1908, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-1893-2013, 2013.

Avgoustidi, V., Nightingale, P. D., Joint, I., Steinke, M., Turner, S. M., Hopkins, F. E., and Liss, P. S.: Decreased marine dimethyl sulfide production under elevated CO2 levels in mesocosm and in vitro studies, Environ. Chem., 9, 399–404, 2012.

Bacic, M. K. and Yoch, D. C.: In vivo characterization of dimethylsulfoniopropionatelyase in the fungus Fusariumlateritium, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 64, 106–111, 1998.

Boyd, P. W. and Doney, S. C.: Modelling regional responses by marine pelagic ecosystems to global climate change, Geophys. Res. Lett., 29, 1–4, 2002.

Charlson, R. J., Lovelock, J. E., Andreae, M. O., and Wakeham, S. G.: Oceanic phytoplankton, atmospheric sulfur, cloud albedo and climate, Nature, 326, 655–661, 1987.

Curson, A. R., Liu, J., Martínez, A. B., Green, R., Chan, Y., Carrion, O. Williams, B. T., Zhang, S. H., Yang, G. P., Page, P. C. B., Zhang, X. H., and Todd, J. D.: Dimethylsulfoniopropionate biosynthesis in marine bacteria and identification of the key gene in this process, Nat. Microbiol., 2, 17009, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.9, 2017.

Czerny, J., Schulz, K. G., Ludwig, A., and Riebesell, U.: Technical Note: A simple method for air-sea gas exchange measurements in mesocosms and its application in carbon budgeting, Biogeosciences, 10, 1379–1390, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-1379-2013, 2013.

de Souza, M. P. and Yoch, D. C.: Purification and characterization of dimethylsulfoniopropionatelyase from an Alcaligenes-like dimethyl sulfide-producing marine isolate, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 61, 21–26, 1995.

Doney, S. C., Fabry, V. J., Feely, R. A., and Kleypas, J. A.: Ocean acidification: the other CO2 problem, Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci., 1, 169–192, 2009.

Fenical, W.: Natural products chemistry in the marine environment, Science, 215, 923–928, 1982.

Gattuso, J. P., Gao, K., Lee, K., Rost, B., and Schulz, K. G.: Approaches and tools to manipulate the carbonate chemistry, edited by: Riebesell, U., Fabry, V. J., Hansson, L., and Gattuso, J. P., in: Guide to Best Practices in Ocean Acidification Research and Data Reporting, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg, 41–52, 2010.

Gattuso, J. P., Magnan, A., Bille, R., Cheung, W. W. L., Howes, E. L., Joos, F., Allemand, D., Bopp, L., Cooley, S. R., Eakin, C. M., Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Kelly, R. P., Portner, H. O., Rogers, A. D., Baxter, J. M., Laffoley, D., Osborn, D., Rankovic, A., Rochette, J., Sumaila, U. R., Treyer, S., and Turley, C.: Contrasting futures for ocean and society from different anthropogenic CO2 emissions scenarios, Science, 349, aac4722, doi:10.1126/science.aac4722, 2015.

Hopkins, F. E. and Archer, S. D.: Consistent increase in dimethyl sulfide (DMS) in response to high CO2 in five shipboard bioassays from contrasting NW European waters, Biogeosciences, 11, 4925–4940, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-4925-2014, 2014.

Hopkins, F. E., Kimmance, S. A., Stephens, J. A., Bellerby, R. G. J., Brussaard, C. P. D., Czerny, J., Schulz, K. G., and Archer, S. D.: Response of halocarbons to ocean acidification in the Arctic, Biogeosciences, 10, 2331–2345, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-2331-2013, 2013.

Hopkins, F. E., Turner, S. M., Nightingale, P. D., Steinke, M., and Liss, P. S.: Ocean acidification and marine biogenic trace gas production, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 760–765, 2010.

Huang, Y. B., Liu, X., Edward, A. L., Chen, B. Z., Li Y., Xie, Y. Y., Wu, Y. P., Gao K. S., and Huang, B. Q.: Effects of increasing atmospheric CO2 on the marine phytoplankton and bacterial metabolism during a bloom: A coastal mesocosm study, Sci. Total. Environ., 633, 618–629, 2018.

Hughes, C., Johnson, M., Utting, R., Turner, S., Malin, G., Clarke, A., and Liss, P. S.: Microbial control of bromocarbon concentrations in coastal waters of the western Antarctic Peninsula, Mar. Chem., 151, 35–46, 2013.

Jenkins, M. E., Cox, R. A., and Hayman, G. D.: Kinetics of the reaction of IO radicals with HO2 at 298 K, Chem. Phys. Lett., 177, 272–278, 1991.

Karlsson, A., Auer, N., Schulz-Bull, D., and Abrahamsson, K.: Cyanobacterial blooms in the Baltic–A source of halocarbons, Mar. Chem., 110, 129–139, 2008.

Kiene, R. P., Linn, L. J., Gonzalez, J., Moran, M. A., and Bruton, J. A.: Dimethylsulfoniopropionate and methanethiol are important precursors of methionine and protein-sulfur in marine bacterioplankton, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 65, 4549–4558, 1999.

Kiene, R. P. and Linn, L. J.: The fate of dissolved dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) in seawater: tracer studies using 35S-DMSP. Geochim, Cosmochim. Acta., 64, 2797–2810, 2000.

Kiene, R. P. and Slezak, D.: Low dissolved DMSP concentrations in seawater revealed by smallvolume gravity filtration and dialysis sampling, Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods, 4, 80–95, 2006.

Kirkwood, M., Le Brun, N. E., Todd, J. D., and Johnston, A. W. B.: The dddP gene of Roseovarius nubinhibens encodes a novel lyase that cleaves dimethylsulfoniopropionate into acrylate plus dimethyl sulfide, Microbiology, 156, 1900–1906, 2010.

Li, Y. H., Xu, J. T., and Gao, K.: Light-modulated responses of growth and photosynthetic performance to ocean acidification in the model diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum, PLoS One, 9, e96173, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096173, 2014.

Liss, P., Marandino, C. A., Dahl, E., Helmig, D., Hintsa, E. J., Hughes, C., Johnson, M., Moore, R. M., Plane, J. M. C., Quack, B., Singh, H. B., Stefels, J., von Glasow, R., and Williams, J.: Short-lived trace gases in the surface ocean and the atmosphere, in: Ocean-Atmosphere Interactions of Gases and Particles, edited by: Liss, P. and Johnson, M., Springer, 55–112, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-25643-1, 2014.

Liu, N., Tong, S., Yi, X., Li, Y., Li, Z., Miao, H., Wang, T., Li, F., Yan, D., Huang, R., Wu, Y., Hutchins, D. A., Beardall, J., Dai, M., and Gao, K.: Carbon assimilation and losses during an ocean acidification mesocosm experiment, with special reference to algal blooms, Mar. Environ. Res., 129, 229–235, 2017.

Manley, S. L. and De La Cuesta, J. L.: Methyl iodide production from marine phytoplankton cultures, Limnol. Oceanogr., 42, 142–147, 1997.

Orr, J. C., Fabry, V. J., Aumont, O., Bopp, L., Doney, S. C., Feely, R. A., Gnanadesikan, A., Gruber, N., Ishida, A., Joos, F., Key, R. M., Lindsay, K., Maier-Reimer, E., Matear. R., Monfray, P., Mouchet, A., Najjar, R. G., Plattner, G. K., Rodgers, K. B., Sabine, C. L., Sarmiento, J. L., Schlitzer, R., Slater, R. D., Totterdell, I. J., Weirig, M. F., Yamanaka, Y., and Yool, A.: Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty first century and its impact on calcifying organisms, Nature, 437, 681–686, 2005.

Porra, R. J.: The chequered history of the development and use of simultaneous equations for the accurate determination of chlorophylls a and b, Photosynth. Res., 73, 149–156, 2002.

Porter, K. G. and Feig, Y. S.: DAPI for identifying and counting aquatic microflora, Limnol. Oceanogr., 25, 946–948, 1980.

Quinn, P. K. and Bates, T. S.: The case against climate regulation via oceanic phytoplankton sulphur emissions, Nature, 480, 51–56, 2011.

Raina, J. B., Tapiolas, D., Motti, C. A., Foret, S., Seemann, T., and Tebben, J.: Isolation of an antimicrobial compound produced by bacteria associated with reef-building corals, PeerJ, 4, e2275, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2275, 2016.

Richter, U. and Wallace, D. W. R.: Production of methyl iodide in the tropical Atlantic Ocean, Geophys. Res. Lett., 31, L23S03, doi:10.1029/2004GL020779, 2004.

Riebesell, U., Czerny, J., von Bröckel, K., Boxhammer, T., Büdenbender, J., Deckelnick, M., Fischer, M., Hoffmann, D., Krug, S. A., Lentz, U., Ludwig, A., Muche, R., and Schulz, K. G.: Technical Note: A mobile sea-going mesocosm system – new opportunities for ocean change research, Biogeosciences, 10, 1835–1847, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-1835-2013, 2013.

Roy, R., Pratihary, A., Narvenkar, G., Mochemadkar, S., Gauns, M., and Naqvi, S. W. A.: The relationship between volatile halocarbons and phytoplankton pigments during a Trichodesmium bloom in the coastal eastern Arabian Sea, Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci., 95, 110–118, 2011.

Simó, R., Archer, S. D., Pedros-Alio, C., Gilpin, L., and Stelfox-Widdicombe, C. E.: Coupled dynamics of dimethylsulfoniopropionate and dimethylsulfide cycling and the microbial food web in surface waters of the North Atlantic, Limnol. Oceanogr., 47, 53–61, 2002.

Simó, R., Vila-Costa, M., Alonso-Sáez, L., Cardelús, C., Guadayol, Ó., Vázquez-Dominguez, E., and Gasol, J. M.: Annual DMSP contribution to S and C fluxes through phytoplankton and bacterioplankton in a NW Mediterranean coastal site, Aquat. Microb. Ecol., 57, 43–55, 2009.

Stefels, J. and Dijkhuizen, L.: Characteristics of DMSP-lyase in Phaeocystis sp. (Prymnesiophyceae), Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 131, 307–313, 1996.

Stefels, J., Steink, M., Turner, S., Malin, G., and Belviso, S.: Environmental constraints on the production of the climatically active gas dimethylsulphide (DMS) and implications for ecosystem modelling, Biogeochemistry, 83, 245–275, 2007.

Steinke, M. and Kirst, G. O.: Enzymatic cleavage of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) in cell-free extracts of the marine macroalga Enteromorphaclathrata (Roth) Grev (Ulvales, Chlorophyta), J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol., 201, 73–85, 1996.

Sugie, K., and Yoshimura, T.: Effects of high CO2 levels on the ecophysiology of the diatom Thalassiosira weissflogii differ depending on the iron nutritional status, ICES J. Mar. Sci., 73, 680–692, 2016.

Todd, J. D., Rogers, R., Li, Y. G., Wexler, M., Bond, P. L., Sun, L., Cruson, A. R. J., Malin, G., Steinke, M., and Johnston, A. W. B.: Structural and regulatory genes required to make the gas dimethyl sulfide in bacteria, Science, 315, 666–669, 2007.

Visscher, P. T., Quist, P., and van Gemerden, H.: Methylated sulfur compounds in microbial mats: in situ concentrations and metabolism by a colorless sulfur bacterium, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 57, 1758–1763, 1991.

Vogt, M., Steinke, M., Turner, S. M., Paulino, A., Meyerhöfer, M., Riebesell, U., LeQuéré, C., and Liss, P. S.: Dynamics of dimethylsulphoniopropionate and dimethylsulphide under different CO2 concentrations during a mesocosm experiment, Biogeosciences, 5, 407–419, 2008.

Vogt, M., Steinke, M., Turner, S., Paulino, A., Meyerhöfer, M., Riebesell, U., Le Quéré, C., and Liss, P.: Dynamics of dimethylsulphoniopropionate and dimethylsulphide under different CO2 concentrations during a mesocosm experiment, Biogeosciences, 5, 407–419, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-5-407-2008, 2008.

Webb, A. L., Leedham-Elvidge, E., Hughes, C., Hopkins, F. E., Malin, G., Bach, L. T., Schulz, K., Crawfurd, K., Brussaard, C. P. D., Stuhr, A., Riebesell, U., and Liss, P. S.: Effect of ocean acidification and elevated fCO2 on trace gas production by a Baltic Sea summer phytoplankton community, Biogeosciences, 13, 4595–4613, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-13-4595-2016, 2016.

Webb, A. L., Malin, G., Hopkins, F. E., Ho, K. L., Riebesell, U., Schulz, K., Larsen, A., and Liss, P.: Ocean acidification has different effects on the production of dimethylsulphide and dimethylsulphoniopropionate measured in cultures of Emiliania huxleyi RCC1229 and mesocosm study: a comparison of laboratory monocultures and community interactions, Environ. Chem., 13, EN14268, https://doi.org/10.1071/EN14268, 2015.

Wingenter, O. W., Haase, K. B., Zeigler, M., Blake, D. R., Rowland, F. S., Sive, B. C., Paulino, A., Thyrhaug, R., Larsen, A., Schulz, K., Meyerhofer, M., and Riebesell, U.: Unexpected consequences of increasing CO2 and ocean acidity on marine production of DMS and CH2ClI: Potential climate impacts, Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, L05710, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL028139, 2007.

Xing, T., Gao, K., and Beardall, J.: Response of growth and photosynthesis of Emiliania huxleyi to visible and UV irradiances under different light regimes, Photochem. Photobiol., 91, 343–349, 2015.

Yang, G. P., Lu, X. L., Song, G. S., and Wang, X. M.: Purge-and-trap gas chromatography method for analysis of methyl chloride and methyl bromide in seawater, Chin. J. Anal. Chem., 38, 719–722, 2010.

Yost, D. M. and Mitchelmore, C. L.: Dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) lyase activity in different strains of the symbiotic alga Symbiodinium microadriaticum, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 386, 61–70, 2009.

Yuan, D., Yang, G. P., and He, Z.: Spatio-temporal distributions of chlorofluorocarbons and methyl iodide in the Changjiang (Yangtze River) estuary and its adjacent marine area, Mar. Pollut. Bull., 103, 247–259, 2016.

Zhang, S. H., Yang, G. P., Zhang, H. H., and Yang, J.: Spatial variation of biogenic sulfur in the south Yellow Sea and the East China Sea during summer and its contribution to atmospheric sulfate aerosol, Sci. Total Environ., 488–489, 157–167, 2014.