the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Macromolecular fungal ice nuclei in Fusarium: effects of physical and chemical processing

Anna T. Kunert

Mira L. Pöhlker

Kai Tang

Carola S. Krevert

Carsten Wieder

Kai R. Speth

Linda E. Hanson

Cindy E. Morris

David G. Schmale III

Ulrich Pöschl

Janine Fröhlich-Nowoisky

Some biological particles and macromolecules are particularly efficient ice nuclei (IN), triggering ice formation at temperatures close to 0 ∘C. The impact of biological particles on cloud glaciation and the formation of precipitation is still poorly understood and constitutes a large gap in the scientific understanding of the interactions and coevolution of life and climate. Ice nucleation activity in fungi was first discovered in the cosmopolitan genus Fusarium, which is widespread in soil and plants, has been found in atmospheric aerosol and cloud water samples, and can be regarded as the best studied ice-nucleation-active (IN-active) fungus. The frequency and distribution of ice nucleation activity within Fusarium, however, remains elusive. Here, we tested more than 100 strains from 65 different Fusarium species for ice nucleation activity. In total, ∼11 % of all tested species included IN-active strains, and ∼16 % of all tested strains showed ice nucleation activity above −12 ∘C. Besides Fusarium species with known ice nucleation activity, F. armeniacum, F. begoniae, F. concentricum, and F. langsethiae were newly identified as IN-active. The cumulative number of IN per gram of mycelium for all tested Fusarium species was comparable to other biological IN like Sarocladium implicatum, Mortierella alpina, and Snomax®. Filtration experiments indicate that cell-free ice-nucleating macromolecules (INMs) from Fusarium are smaller than 100 kDa and that molecular aggregates can be formed in solution. Long-term storage and freeze–thaw cycle experiments revealed that the fungal IN in aqueous solution remain active over several months and in the course of repeated freezing and thawing. Exposure to ozone and nitrogen dioxide at atmospherically relevant concentration levels also did not affect the ice nucleation activity. Heat treatments at 40 to 98 ∘C, however, strongly reduced the observed IN concentrations, confirming earlier hypotheses that the INM in Fusarium largely consists of a proteinaceous compound. The frequency and the wide distribution of ice nucleation activity within the genus Fusarium, combined with the stability of the IN under atmospherically relevant conditions, suggest a larger implication of fungal IN on Earth’s water cycle and climate than previously assumed.

- Article

(2323 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(217 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Ice particles in the atmosphere are formed either by homogeneous nucleation at temperatures below −38 ∘C or by heterogeneous nucleation catalyzed by particles or macromolecules serving as ice nuclei (IN) at warmer temperatures (Pruppacher and Klett, 1997; reviewed in detail in Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2016 and Knopf et al., 2018). Biological particles in particular are expected to play an important role as IN in the temperature range from −15 to 0 ∘C, but the impact of biological particles on cloud glaciation and the formation of precipitation is still poorly understood (Coluzza et al., 2017). Several studies suggest a triggering effect of biological IN for cloud glaciation and formation of precipitation (Creamean et al., 2013; DeMott and Prenni, 2010; Failor et al., 2017; Hanlon et al., 2017; Joly et al., 2014; Petters and Wright, 2015; Pratt et al., 2009; Stopelli et al., 2015, 2017), and former studies have shown that biological particles are more efficient than mineral IN (DeMott and Prenni, 2010; Després et al., 2012; Hill et al., 2014; Hoose and Möhler, 2012; Huffman et al., 2013; Möhler et al., 2007; Morris et al., 2014; Murray et al., 2012; Pratt et al., 2009).

The best characterized biological IN are common plant-associated bacteria of the genera Pseudomonas, Pantoea, and Xanthomonas (Garnham et al., 2011; Govindarajan and Lindow, 1988; Graether and Jia, 2001; Green and Warren, 1985; Hill et al., 2014; Kim et al., 1987; Ling et al., 2018; Šantl-Temkiv et al., 2015; Schmid et al., 1997; Wolber et al., 1986), and, recently, an ice-nucleation-active (IN-active) Lysinibacillus was found (Failor et al., 2017). The first identified IN-active fungi were strains of the genus Fusarium (Hasegawa et al., 1994; Pouleur et al., 1992; Richard et al., 1996; Tsumuki et al., 1992). To date, a few more fungal genera with varying initial freezing temperatures such as Isaria farinosa ( ∘C), Mortierella alpina ( ∘C), Puccinia species (−4 to −8 ∘C), and Sarocladium (formerly named Acremonium) implicatum ( ∘C) have been identified as IN-active (Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2015; Huffman et al., 2013; Morris et al., 2013; Richard et al., 1996).

The genus Fusarium is cosmopolitan and includes saprophytes and pathogens of plants and animals (Leslie and Summerell, 2006; Nelson et al., 1994). Although they are considered to be primarily soilborne fungi, many species of Fusarium are airborne (Prussin et al., 2014; Schmale et al., 2012; Schmale and Ross, 2015), and they were found in atmospheric and cloud water samples (e.g., Amato et al., 2007; Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2009; Fulton, 1966). Some species can cause wilts, blights, root rots, and cankers in agriculturally important crops worldwide (e.g., Schmale and Gordon, 2003; Wang and Jeffers, 2000). Other species can produce secondary metabolites known as mycotoxins that can cause a variety of acute and chronic health effects in humans and animals (e.g., Bush et al., 2004; Ichinoe et al., 1983).

While the factors for a positive selective pressure for ice nucleation activity in Fusarium and other fungi have not been directly identified, an ecological advantage of initiating ice formation is easily conceivable. Indeed, most IN-active bacteria and fungi are isolated from regions with seasonal temperatures below 0 ∘C (Diehl et al., 2002; Schnell and Vali, 1972). Ice nucleation activity at temperatures close to 0 ∘C could be beneficial for pathogens or might provide an ecological advantage for saprophytic Fusarium species by facilitating in the acquisition of nutrients liberated during cell rupture of the host (Lindow et al., 1982). Furthermore, IN on the surface of the mycelium could avoid physical damage of the fungus by protective extracellular freezing (Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2015; Zachariassen and Kristiansen, 2000) or by binding moisture as ice in cold and dry seasons (Pouleur et al., 1992). With increasing temperatures, the retained water can be of advantage in early vegetative periods and for bacterial movement on the mycelial water film known as the fungal highway (Kohlmeier et al., 2005; Warmink et al., 2011). Moreover, ice nucleation activity might be beneficial for airborne Fusarium and for their return to Earth’s surface under advantageous conditions in a feedback cycle known as bioprecipitation (Després et al., 2012; Morris et al., 2013, 2014; Sands et al., 1982). In addition, once the IN are released into the environment, they can adsorb to clay and might also be available in the atmosphere associated with soil dust particles (Conen et al., 2011; Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2015, 2016; Hill et al., 2016; O'Sullivan et al., 2014, 2015, 2016; Sing and Sing, 2010).

The sources, abundance, and identity of biological IN are not well characterized (Coluzza et al., 2017), and it has been proposed that systematic surveys will likely increase the number of IN-active fungal species discovered (Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2015). Fusarium is the best-known IN-active fungus, but the frequency and distribution of ice nucleation activity within Fusarium is not well known. In this study, more than 100 strains from 65 different Fusarium species were tested for ice nucleation activity in three laboratories with different freezing methods. A high-throughput droplet freezing assay was used to quantify the IN of selected Fusarium species, and filtration experiments were performed to estimate the size of the Fusarium IN. Furthermore, the stability of Fusarium IN upon exposure to ozone and nitrogen dioxide, under high and low or quickly changing temperatures, and after short- and long-term storage under various conditions was investigated.

2.1 Origin and growth conditions of fungal cultures

Thirty Fusarium strains from USDA-ARS, Michigan State University (Linda E. Hanson, East Lansing, MI, USA), 13 strains from the Schmale Laboratory at Virginia Tech (David G. Schmale, Blacksburg, VA, USA), and 69 strains from the Kansas State University Teaching Collection (John F. Leslie, Manhattan, KS, USA) were screened for ice nucleation activity (Table S1 in the Supplement).

The strains from the USDA-ARS, Michigan State University, were collected from crop tissue (sugar beet). All isolates were from field-grown beets and were obtained by hyphal tip transfer. The strains from the Schmale Laboratory at Virginia Tech were collected with unmanned aircraft systems (UASs or drones) equipped with remotely operated sampling devices containing a Fusarium selective medium (e.g., Lin et al., 2013, 2014). All of the Schmale Laboratory strains were collected 100 m above ground level at the Kentland Farm in Blacksburg, Virginia, USA. Detailed information is not available for the sources of the strains for the Kansas State University Teaching collection. However, some of these strains are holotype strains referenced in Leslie and Summerell (2006).

The strains from the USDA-ARS, Michigan State University, were cultivated on dextrose peptone yeast extract agar, containing 10 g L−1 dextrose (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA), 3 g L−1 peptone (Difco Proteose Peptone No. 3, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NY, USA), and 0.3 g L−1 yeast extract (Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, USA), and were filtered through a 0.2 µm pore diameter filter (PES disposable filter units, Life Science Products, Frederick, CO, USA). After filtration, 12 g L−1 agarose (Certified Molecular Biology Agarose, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was added, and the medium was sterilized by autoclaving at 121 ∘C for 20 min. The colonies were grown at 22 to 24 ∘C for 7 to 19 d. The strains from the Schmale Laboratory at Virginia Tech and the Kansas State University Teaching Collection were maintained in cryogenic storage at −80 ∘C and were grown on quarter-strength potato dextrose agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, USA) on 100 mm petri plates at ambient room temperature for 4 d prior to ice nucleation assays.

For quantitative analysis, exposure experiments, heat treatments, freeze–thaw cycles, and short- and long-term storage tests, a selection of IN-active tested strains was grown on full-strength potato dextrose agar (VWR International GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) first at room temperature for 4 to 6 d and then at 6 ∘C for about 4 weeks. For filtration experiments, the fungal cultures were grown at 6 ∘C for up to 6 months.

2.2 Preparation and treatments of aqueous extracts

For LED-based Ice Nucleation Detection Apparatus (LINDA) (Stopelli et al., 2014) experiments (see Sect. 2.3), 4 mL of sterile 0.9 % NaCl was added to each of eight petri plates, and the fungal cultures were scraped with the flat end of a sterile bamboo skewer. The resulting suspension of mycelium and spores was filtered through a 100 µm filter (Corning Life Sciences, Reims, France).

For Twin-plate Ice Nucleation Assay (TINA) (Kunert et al., 2018) experiments (see Sect. 2.3) the fungal mycelium was scraped off the agar plate and transferred into a 15 mL tube (Greiner Bio One, Kremsmünster, Austria). The fresh weight of the mycelium was determined gravimetrically. Pure water was prepared as described in Kunert et al. (2018). Aliquots of 10 mL pure water were added before vortexing three times at 2700 rpm for 30 s (Vortex-Genie 2, Scientific Industries, Inc., Bohemia, NY, USA) and centrifugation at 4500 g for 10 min (Heraeus Megafuge 40, Thermo Scientific, Braunschweig, Germany). For all experiments, the aqueous extract were filtered successively through a 5 and a 0.1 µm PES syringe filter (Acrodisc®, Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany), and the aqueous extracts contained IN from spores and mycelial surfaces.

For filtration experiments, the 0.1 µm filtrate was further filtered successively through 300 000 and 100 000 MWCO PES ultrafiltration units (Vivaspin®, Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany). After each filtration step, the IN concentration was determined using TINA.

For exposure experiments, aqueous extracts of F. acuminatum 3–68 and F. avenaceum 2–106 were exposed to high concentrations of O3 and NO2 as described in Liu et al. (2017). Briefly, a mixture of 1 ppm O3 and 1 ppm NO2 was bubbled through 1 mL aliquots of aqueous extract for 4 h, and the IN concentration was determined using TINA.

For heat treatment experiments, aliquots of aqueous extracts were incubated at 40, 70, and 98 ∘C for 1 h for each of F. acuminatum 3–68, F. armeniacum 20 970, F. avenaceum 2–106, and F. langsethiae 19 084. The IN concentration was determined using TINA.

For freeze–thaw cycles, the ice nucleation activity of F. acuminatum 3–68 was determined shortly after preparation of the aqueous extract and after storage at 6 ∘C for 24 h using TINA. Then, the aqueous extract was stored at −20 ∘C for 24 h and thawed again. The ice nucleation activity was tested before storage at −20 ∘C for an additional 24 h. After thawing, the ice nucleation activity was determined again.

For long-term storage experiments, the aqueous extracts of various Fusarium species were stored at 6 ∘C for about 4 months or at −20 ∘C for about 8 months, and the ice nucleation activity was determined using TINA.

2.3 Ice nucleation assays

Two independent droplet freezing assays conducted in two laboratories were used to investigate the distribution of ice nucleation activity within Fusarium in an initial screening.

First, a thermal cycler (PTC200, MJ Research, Hercules, CA, USA) was used as described in Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al. (2015) to screen 30 Fusarium strains from seven species from USDA-ARS, Michigan State University, in the temperature range from −2 to −9 ∘C. Mycelium was picked with sterile pipette tips (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY, USA) into 80 µL aliquots of 0.2 µm pore diameter filtered dextrose peptone yeast (DPY) broth in sterile 96-well polypropylene PCR plates (VWR International, LLC, Radnor, PA, USA). Up to seven droplets were measured for each sample, and the mean freezing temperature was calculated. Aliquots of uninoculated DPY broth were used as negative controls, which did not freeze in the investigated temperature interval.

Second, the LED-based Ice Nucleation Detection Apparatus (LINDA) was used as described by Stopelli et al. (2014) to screen 13 strains from the Schmale Laboratory at Virginia Tech and 69 strains from the Kansas State University Teaching Collection. Aliquots of 200 µL of each aqueous extract were transferred to three separate 500 µL tubes and placed on ice for 1 h prior to the LINDA experiments. LINDA was run from −1 to −20 ∘C, and images of the samples were recorded every 6 s. The mean freezing temperature for three droplets was calculated. Note that the aqueous extracts were prepared in 0.9 % NaCl solution, which could reduce the freezing temperatures by 0.5 ∘C based on theoretical calculations. We cannot exclude, however, that the high concentration of IN compensates for the effect of NaCl on the freezing temperature. This is supported by the investigations of Stopelli et al. (2014), who did not find a systematic suppression of freezing at this salt concentration in LINDA experiments. As a negative control, a 0.9 % NaCl solution was added to three uninoculated agar plates, and the freezing started below −14 ∘C. As positive control, aqueous suspensions of Pseudomonas syringae CC94 from the collection of INRA (Avignon, France) (Berge et al., 2014), with a final OD580 of 0.5 to 0.7, i.e. ∼109 bacteria mL−1, were used for each experiment. The bacteria were grown on King's medium B (King et al., 1954) at 22 to 25 ∘C for 48 h, and aqueous suspensions were equilibrated at 4 ∘C for 1 to 4 h before LINDA experiments. The freezing temperatures of P. syringae CC94 ranged from −3.5 to −4.6 ∘C.

Ice nuclei of selected Fusarium species, which were long known for ice nucleation activity (F. acuminatum, F. avenaceum), as well as all the newly identified species, were further analyzed in immersion freezing mode using the high-throughput Twin-plate Ice Nucleation Assay (TINA) (Kunert et al., 2018). The aqueous extracts were serially diluted 10-fold with pure water by a liquid handling station (epMotion ep5073, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) to a dilution at which droplets remained liquid in the investigated temperature interval. Of each dilution, 96 droplets (3 µL) were tested with a continuous cooling rate of 1 ∘C min−1 from 0 to −20 ∘C. Pure water samples (0.1 µm filtrated) served as a negative control for each experiment. These did not freeze in the observed temperature interval. The temperature was measured with an accuracy of 0.2 K (Kunert et al., 2018). The obtained fraction of frozen droplets (fice) and the counting error were used to calculate the cumulative number of IN (Nm) with the associated error using the Vali formula and the Gaussian error propagation (Kunert et al., 2018; Vali, 1971). For each experiment, the cumulative number of IN was averaged over all dilutions. If the experiment was repeated, the cumulative number of IN was averaged over all experiments, and the standard error was calculated. Three independent experiments with aqueous extracts from three individual fungal culture plates of the same strain showed similar results with only slight variation. An example of results is presented for F. armeniacum 20 970 (Fig. S1 in the Supplement).

3.1 IN-active Fusarium species

Although several IN-active Fusarium species are known, the frequency and distribution of ice nucleation activity within the fungal genus Fusarium are still not well studied (Hasegawa et al., 1994; Humphreys et al., 2001; Pouleur et al., 1992; Richard et al., 1996; Tsumuki and Konno, 1994). Two initial screenings in the temperature range from −1 to −20 ∘C were performed to better evaluate the frequency of ice nucleation activity within Fusarium. A strain was defined as IN-active, when it initiated ice formation above −9 ∘C (thermal cycler) and −12 ∘C (LINDA), respectively.

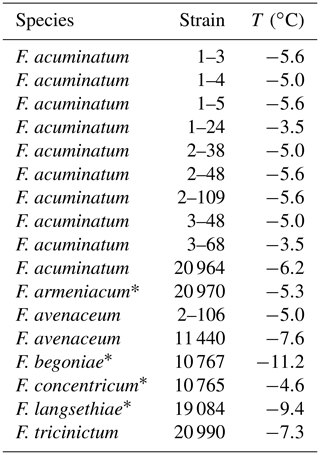

Table 1Ice-nucleation-active Fusarium strains with corresponding mean freezing temperatures of the initial screening. The newly identified IN-active Fusarium species are marked with an asterisk (*).

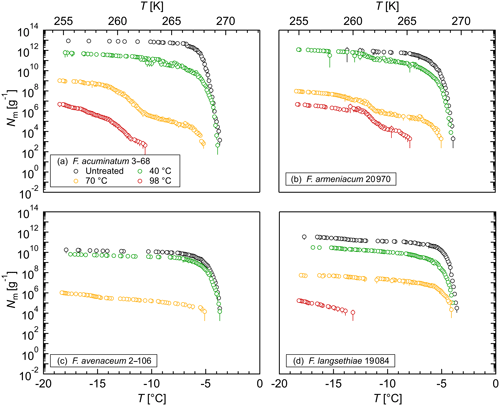

Figure 1Overview of ice nucleation activity for selected Fusarium species and strains: cumulative number of IN (Nm) per gram of mycelium plotted against the temperature (T); arithmetic mean values and standard error of two independent experiments with aqueous extracts from two individual fungal culture plates of the same species.

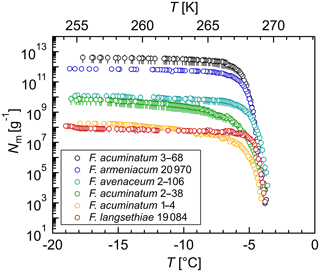

Figure 2Size determination of the Fusarium IN upon filtration: cumulative number of IN (Nm) per gram of mycelium plotted against the temperature (T) for (a) F. acuminatum 3–68, (b) F. armeniacum 20 970, (c) F. avenaceum 2–106, and (d) F. langsethiae 19 084. The error bars were calculated using the counting error and the Gaussian error propagation.

In total, ∼16 % (18/112) of the tested strains showed ice nucleation activity with mean freezing temperatures of −3.5 to −11.2 ∘C (Table 1) in the typical range known for Fusarium (−1 and −9 ∘C) (Hasegawa et al., 1994; Humphreys et al., 2001; Pouleur et al., 1992; Richard et al., 1996; Tsumuki et al., 1992; Tsumuki and Konno, 1994). Most formerly reported initial freezing temperatures were obtained with different Fusarium strains, growth conditions, and freezing assays, which might explain differences compared to our results. The high proportion of IN-active strains within F. acuminatum is consistent with previous reports (Pouleur et al., 1992; Tsumuki et al., 1995). Overall, ∼11 % (7/65) of the tested species included IN-active strains. In addition to strains from Fusarium species with known ice nucleation activity, four Fusarium species were newly identified as IN-active: F. armeniacum, F. begoniae, F. concentricum, and F. langsethiae. In further experiments, the ice nucleation activity of F. begoniae and F. concentricum could not be verified.

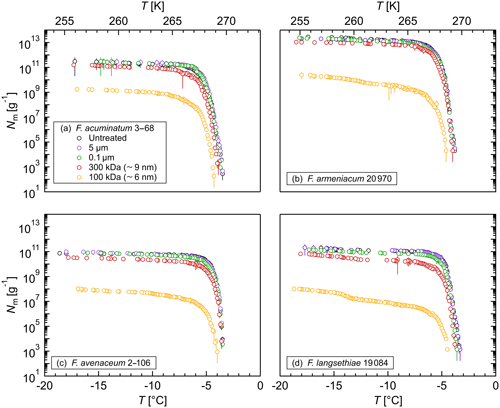

Figure 3Exposure of aqueous extract from Fusarium to ozone and nitrogen dioxide: cumulative number of IN (Nm) per mass of mycelium plotted against the temperature (T) for (a) F. acuminatum 3–68 and (b) F. avenaceum 2–106; arithmetic mean values and standard error of two independent experiments with aqueous extracts from two individual fungal culture plates of the same species.

The newly identified IN-active species are cosmopolitan. Fusarium armeniacum is a toxigenic saprophyte (Burgess et al., 1993), causing seed and root rot on soybeans (Ellis et al., 2012). The geographical distribution has been reported as tropical and subtropical (Leslie and Summerell, 2006), but it was also found in Minnesota, USA (Kommedahl et al., 1979), and Australia (Burgess et al., 1993). Fusarium begoniae is a plant pathogen of Begonia found in Germany with a potential wider distribution (Nirenberg and O'Donnell, 1998). Fusarium concentricum is a plant pathogen, which is frequently found in Central America and isolated from bananas (Aoki et al., 2001; Leslie and Summerell, 2006), and F. langsethiae is a broadly distributed cereal pathogen (Torp and Nirenberg, 2004). Some strains of these newly identified IN-active species are known to produce mycotoxins, which can threaten the health of humans and animals (Fotso et al., 2012; Kokkonen et al., 2012; Wing et al., 1993a, b).

The results suggest that the ice nucleation activity within Fusarium is more widespread than previously known. Not all Fusarium species include IN-active strains and not all strains within one species show ice nucleation activity. Earlier studies including experiments suggested that Fusarium IN are proteins or at least contain a proteinaceous compound (Hasegawa et al., 1994; Pouleur et al., 1992; Tsumuki and Konno, 1994). Their production requires energy, and we might assume that this trait would not be expressed or maintained unless there was an ecological advantage. It is known that Fusarium can regulate the gene expression for IN production, depending on environmental conditions such as nutrient availability (Richard et al., 1996), and some Fusarium species reduce or lose their ice nucleation activity after several subcultures (Pummer et al., 2013; Tsumuki et al., 1995). Thus, we cannot exclude that all Fusarium strains have the ability to produce IN. From the phylogenetic distribution of ice nucleation activity across the genus Fusarium, we can speculate that ice nucleation activity is a very old trait, but either the gene expression requires a trigger, which is not yet identified, or the trait might be in the process of being lost. It is unlikely, however, that the age of the genetic determinants of fungal ice nucleation activity is older than that in bacteria, since fungi diverged well after the age that has been attributed to the bacterial IN gene (Morris et al., 2014), and the genetic determinants are not the same as those in bacteria.

3.2 Quantification and size determination of IN from selected Fusarium species

A selection of IN-active Fusarium species was further investigated by extensive droplet freezing assay analysis using TINA. All tested Fusarium strains initiated ice nucleation between −3 and −4 ∘C (Fig. 1). Differences in the freezing temperatures between the initial screening and the quantitative analysis can be due to different growth conditions and freezing assays. The cumulative number of IN (Nm) per gram of mycelium was in the range between 108 g−1 and 1013 g−1. Fusarium acuminatum 3–68 showed the highest ice nucleation activity and F. langsethiae the lowest per gram of mycelium. The results are comparable to other IN-active microorganisms like Sarocladium implicatum (108 g−1, Pummer et al., 2015), Mortierella alpina (109 g−1, Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2015; 1010 g−1, Kunert et al., 2018), and the bacterial IN-active substance Snomax® containing Pseudomonas syringae (1012 g−1, Budke and Koop, 2015; Kunert et al., 2018).

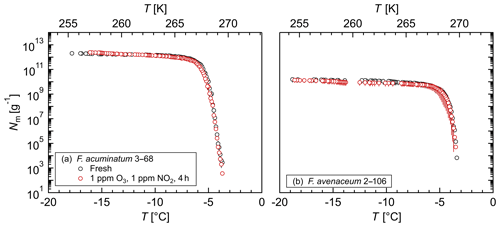

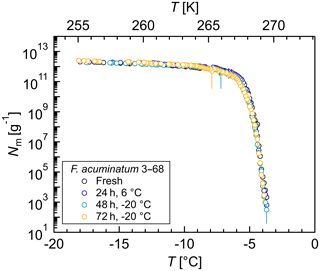

Figure 4Effects of high temperatures on the ice nucleation activity of Fusarium: cumulative number of IN (Nm) per gram of mycelium plotted against the temperature (T) for (a) F. acuminatum 3–68, (b) F. armeniacum 20 970, (c) F. avenaceum 2–106, and (d) F. langsethiae 19 084. The error bars were calculated using the counting error and the Gaussian error propagation.

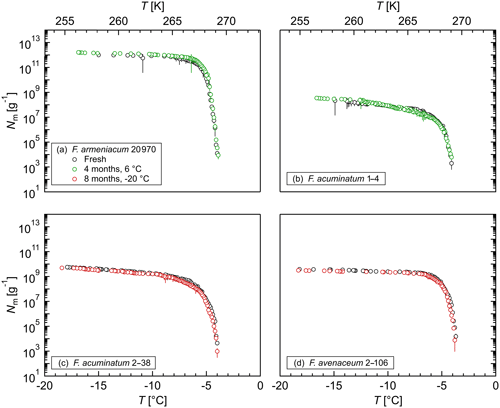

Figure 5Effects of short-term storage and freeze–thaw cycles on the ice nucleation activity of Fusarium acuminatum 3–68: cumulative number of IN (Nm) per gram of mycelium plotted against the temperature (T). The same aqueous extract was measured immediately after preparation (black), after storage at 6 ∘C for 24 h (blue), after another 24 h stored at −20 ∘C (total 48 h; turquoise), and after another 24 h stored at −20 ∘C (total 72 h; yellow). The error bars were calculated using the counting error and the Gaussian error propagation.

The size of the Fusarium IN was investigated by filtration experiments. Filtration through a 5 and a 0.1 µm filter did not affect the ice nucleation activity (Fig. 2), revealing that Fusarium IN are smaller than 100 nm, cell-free, easily removed from the fungus, and stay active in solution. This is in agreement with other Fusarium studies (O'Sullivan et al., 2015; Pouleur et al., 1992; Tsumuki and Konno, 1994). Moreover, biological ice-nucleating macromolecules (INMs) smaller than 200 nm were also found in various organisms, e.g., other fungi (Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2015; Pummer et al., 2015); leaves, bark, and pollen from birch trees (Betula spp.) (Felgitsch et al., 2018; Pummer et al., 2012); leaf litter (Schnell and Vali, 1973); some microalgae (Tesson and Šantl-Temkiv, 2018); strains of Lysinibacillus (Failor et al., 2017); and biological particles in the sea surface microlayer (Irish et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2015). Filtration through a 300 000 MWCO filter unit decreased the cumulative number of IN per gram of mycelium by about 50 % to 75 % depending on the Fusarium species, but a tremendous number of IN (1010–1013 g−1) still passed through the filter. The initial freezing temperature was slightly shifted towards lower temperatures. Further filtration through a 100 000 MWCO filter unit reduced the IN number to 108–1010 g−1, which is less than 1 % of the initial IN concentration. Additionally, the initial freezing temperature was shifted about 1 ∘C towards lower temperatures.

As ice nucleation activity was found in all filtrates, the aqueous extract of Fusarium consists of a mixture of IN-active proteins with different sizes. We hypothesize that Fusarium IN are macromolecules (INMs) smaller than 100 kDa, which agglomerate to large protein complexes in solution. Some of these complexes fall apart upon filtration, so that the INMs can pass through the filter. The small shift in the initial freezing temperature suggests that these INMs reassemble again to aggregates after filtration, as larger IN nucleate at warmer temperatures (Govindarajan and Lindow, 1988; Pummer et al., 2015). Erickson (2009) determined the size of proteins based on theoretical calculations. As the interior of proteins is closely packed with no substantial holes and almost no water molecules inside, proteins are rigid structures with approximately the same density (∼1.37 g cm−1). Assuming the protein as a smooth spherical particle, the minimum diameter of the INM would be smaller than 6.1 nm. Our results are in accordance with Lagzian et al. (2014), who cloned and expressed a 49 kDa IN-active protein from F. acuminatum.

As Fusarium IN are cell-free and can easily be washed off the fungal surface, they can be released in high numbers into the environment. If they are not degraded by microorganisms before, the IN can adsorb to soil dust and be aerosolized while attached to these particles (Conen et al., 2011; Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2015; Hill et al., 2016; O'Sullivan et al., 2014, 2015, 2016; Sing and Sing, 2010). This is in good agreement with Pruppacher and Klett (1997), who found a positive correlation between IN number concentration and particles in the coarse mode. Other releasing processes cannot be excluded; however, it is unlikely that the INMs are present in the atmosphere as individual aerosol particles. Individual proteins with a diameter of ∼6 nm, which may enter the atmosphere, would be in the nucleation mode size range, where particles tend to uptake gaseous compounds and grow to Aitken mode particles, which themselves tend to coagulate to larger agglomerates (Seinfeld and Pandis, 1998).

3.3 Stability of Fusarium IN

In the atmosphere, IN can interact with other aerosol particles or gases. They can be exposed to chemically modifying agents like ozone and nitrogen dioxide, as well as physical stressors like high and low or quickly changing temperatures. To investigate the stability of Fusarium IN, we performed exposure experiments, heat treatments, freeze–thaw cycles, and long-term storage tests.

Figure 6Effect of long-term storage on the ice nucleation activity of (a) F. armeniacum 20 970, (b) F. acuminatum 1–4, (c) F. acuminatum 2–38, and (d) F. avenaceum 2–106: cumulative number of IN (Nm) per gram of mycelium plotted against the temperature (T). The error bars were calculated using the counting error and the Gaussian error propagation.

The influence of chemical processing on the Fusarium IN, in particular oxidation and nitration reactions as occurring during atmospheric aging, was investigated by exposing aqueous extracts from F. acuminatum 3–68 and F. avenaceum 2–106 to high concentrations of ozone and nitrogen dioxide in liquid phase. Figure 3 shows that for both species neither the initial freezing temperature nor the cumulative number of IN per gram of mycelium was affected by exposure. These results demonstrate a high stability of Fusarium IN under oxidizing and nitrating conditions. This is in contrast to other biological IN, e.g., bacterial IN (Snomax®) (Kunert et al., 2018), birch and alder pollen (Gute and Abbatt, 2018), and dissolved organic matter (Borduas-Dedekind et al., 2019), where exposure to oxidizing agents reduced the IN activity.

The stability of the INM in Fusarium was investigated in heat treatment experiments. The ice nucleation activity was reduced significantly at a 40 ∘C treatment (Fig. 4). Between 40 % and 90 % of IN were lost at this temperature depending on the species, which supports the hypothesis that the INM in Fusarium consists of a proteinaceous compound. A heat treatment at 70 ∘C reduced the ice nucleation activity to less than 0.01 % compared to the initial level. Moreover, the initial freezing temperature was shifted to lower temperatures, indicating a breakdown of the large protein aggregates. After a 98 ∘C treatment, we still found ice nucleation activity for all investigated species except for F. avenaceum 2–106. The results are in agreement with previous studies, which also reported a reduction in ice nucleation activity with increasing temperature in heat treatment experiments (Hasegawa et al., 1994; Pouleur et al., 1992; Tsumuki and Konno, 1994). The remaining activity after the 98 ∘C treatment, however, could indicate that posttranslational modifications like glycosylation and therefore polysaccharides could play a role in the ice nucleation activity of Fusarium. Further systematic studies including chemical analyses are needed for elucidation.

To study the effects of short-term storage and freeze–thaw cycles on the ice nucleation activity of F. acuminatum 3–68, IN measurements of the same aqueous extract were performed at different time points (Fig. 5). The results of freshly prepared aqueous extract revealed that the highest activity of fungal IN was already developed during preparation of the filtrate and no time for equilibration was required. Storage of aqueous extract at 6 ∘C for 24 h did not affect the ice nucleation activity. Also, further storage at −20 ∘C for another 24 h and repeated freeze–thaw cycles had no impact on the ice nucleation activity. This means that, once in the atmosphere, the IN can undergo several freeze–thaw cycles without losing their activity and are still able to influence cloud glaciation and the formation of precipitation. This could be an explanation for why not all fungi are always IN-active as their IN are highly stable and quasi-recyclable. Ice nuclei might influence the availability of moisture over long time periods, and if enough moisture is available in the environment, the necessity of IN production would be omitted, and the fungus could save energy.

In addition, the stability of the INM in Fusarium was studied in long-term storage tests, where aqueous extracts of various Fusarium species were stored at different temperatures for a long period of time. Figure 6 shows that storage at 6 ∘C for 4 months and at −20 ∘C for 8 months did not influence the ice nucleation activity of F. armeniacum 20 970, F. acuminatum 1–4, F. avenaceum 2–106, or F. acuminatum 2–38. The results demonstrate the high stability of the INMs in Fusarium in liquid and frozen solutions over long time periods, which makes Fusarium well applicable for laboratory IN studies. Moreover, the high stability is likely an advantage for these fungi to be linked to atmospheric processes.

The frequency and distribution of ice nucleation activity within the fungal genus Fusarium was investigated in a screening of more than 100 strains from 65 different Fusarium species. In total, ∼11 % (7/65) of all tested species included IN-active strains, and ∼16 % (18/112) of all tested strains showed ice nucleation activity, demonstrating the wide distribution of ice nucleation activity within Fusarium. Filtration experiments suggest that Fusarium IN form aggregates consisting of INMs smaller than 100 kDa (∼6 nm). Exposure experiments, freeze–thaw cycles, and long-term storage tests revealed a high stability of the INMs in Fusarium, demonstrating the suitability of Fusarium in laboratory IN studies. Heat treatments at 40 to 98 ∘C reduced the IN concentration significantly, supporting the hypothesis that the INM in Fusarium largely consists of a proteinaceous compound. An involvement of polysaccharides, however, cannot be excluded. The wide distribution of ice nucleation activity within the genus Fusarium, together with the stability of the INM in Fusarium under atmospherically relevant conditions, suggests that the implication of these IN on Earth's water cycle and climate might be more significant than previously assumed. Additional research is necessary to characterize the INMs in Fusarium and processes which can result in their agglomeration to larger protein complexes. To evaluate the implication of these IN on Earth's climate, additional work is required to study the abundance of Fusarium IN in environmental samples on a global scale.

All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-16-4647-2019-supplement.

CEM, JFN, and UP designed the experiments. DGS III and LEH provided fungal cultures. CEM, DGS III, and JFN performed the initial screenings. ATK, KT, CSK, CW, and KRS performed the experiments. ATK, JFN, MLP, and UP discussed the results. ATK and JFN wrote the manuscript with contributions of all coauthors.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We thank Claudia Bartoli, Jan-David Förster, Tom Godwill, Nina-Maria Kropf, and Emiliano Stopelli for technical assistance; Gary D. Franc, Thomas C. J. Hill, Kathrin Reinmuth-Selzle, Beatriz Sánchez-Parra, Jan F. Scheel, and Michael G. Weller for helpful discussions; and the Max Planck Society (MPG) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, FR3641/1-2, FOR 1525 INUIT) for financial support. This work is dedicated to the memory of Gary D. Franc, whose pioneering work in atmospheric microbiology has been an inspiration for this work.

The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by the Max Planck Society.

This paper was edited by Carol Robinson and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Amato, P., Parazols, M., Sancelme, M., Laj, P., Mailhot, G., and Delort, A. M.: Microorganisms isolated from the water phase of tropospheric clouds at the Puy de Dôme: Major groups and growth abilities at low temperatures, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 59, 242–254, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00199.x, 2007. a

Aoki, T., O'Donnell, K., and Ichikawa, K.: Fusarium fractiflexum sp. nov. and two other species within the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex recently discovered in Japan that form aerial conidia in false heads, Mycoscience, 42, 461–478, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02464343, 2001. a

Berge, O., Monteil, C. L., Bartoli, C., Chandeysson, C., Guilbaud, C., Sands, D. C., and Morris, C. E.: A User's Guide to a Data Base of the Diversity of Pseudomonas syringae and Its Application to Classifying Strains in This Phylogenetic Complex, PLoS One, 9, e105547, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105547, 2014. a

Borduas-Dedekind, N., Ossola, R., David, R. O., Boynton, L. S., Weichlinger, V., Kanji, Z. A., and McNeill, K.: Photomineralization mechanism changes the ability of dissolved organic matter to activate cloud droplets and to nucleate ice crystals, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 12397–12412, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-12397-2019, 2019. a

Budke, C. and Koop, T.: BINARY: an optical freezing array for assessing temperature and time dependence of heterogeneous ice nucleation, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 8, 689–703, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-8-689-2015, 2015. a

Burgess, L. W., Forbes, G. A., Windels, C., Nelson, P. E., Marasas, W. F. O., and Gott, K. P.: Characterization and distribution of Fusarium acuminatum subsp. armeniacum subsp. nov., Mycologia, 85, 119–124, 1993. a, b

Bush, B. J., Carson, M. L., Cubeta, M. A., Hagler, W. M., and Payne, G. A.: Infection and Fumonisin Production by Fusarium verticillioides in Developing Maize Kernels, Phytopathology, 94, 88–93, https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.1.88, 2004. a

Coluzza, I., Creamean, J., Rossi, M. J., Wex, H., Alpert, P. A., Bianco, V., Boose, Y., Dellago, C., Felgitsch, L., Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J., Herrmann, H., Jungblut, S., Kanji, Z. A., Menzl, G., Moffett, B., Moritz, C., Mutzel, A., Pöschl, U., Schauperl, M., Scheel, J., Stopelli, E., Stratmann, F., Grothe, H., and Schmale III, D. G.: Perspectives on the Future of Ice Nucleation Research: Research Needs and Unanswered Questions Identified from Two International Workshops, Atmosphere-Basel, 8, 138, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos8080138, 2017. a, b

Conen, F., Morris, C. E., Leifeld, J., Yakutin, M. V., and Alewell, C.: Biological residues define the ice nucleation properties of soil dust, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 9643–9648, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-9643-2011, 2011. a, b

Creamean, J. M., Suski, K. J., Rosenfeld, D., Cazorla, A., DeMott, P. J., Sullivan, R. C., White, A. B., Ralph, F. M., Minnis, P., Comstock, J. M., Tomlinson, J. M., and Prather, K. A.: Dust and Biological Aerosols from the Sahara and Asia Influence Precipitation in the Western U.S., Science, 339, 1572–1578, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1227279, 2013. a

DeMott, P. J. and Prenni, A. J.: New Directions: Need for defining the numbers and sources of biological aerosols acting as ice nuclei, Atmos. Environ., 44, 1944–1945, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.02.032, 2010. a, b

Després, V. R., Huffman, J. A., Burrows, S. M., Hoose, C., Safatov, A. S., Buryak, G., Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J., Elbert, W., Andreae, M. O., Pöschl, U., and Jaenicke, R.: Primary biological aerosol particles in the atmosphere: a review, Tellus B, 64, 15598, https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusb.v64i0.15598, 2012. a, b

Diehl, K., Matthias-Maser, S., Jaenicke, R., and Mitra, S. K.: The ice nucleating ability of pollen: Part II. Laboratory studies in immersion and contact freezing modes, Atmos. Res., 61, 125–133, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2005.03.008, 2002. a

Ellis, M. L., Diaz Arias, M. M., Leandro, L. F., and Mungvold, G. P.: First report of Fusarium armeniacum causing seed rot and root rot on soybean (Glycine max) in the United States, Plant Dis., 96, 1693, https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-05-12-0429-PDN, 2012. a

Erickson, H. P.: Size and Shape of Protein Molecules at the Nanometer Level Determined by Sedimentation, Gel Filtration, and Electron Microscopy, Biol. Proced. Online, 11, 32–51, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12575-009-9008-x, 2009. a

Failor, K. C., Schmale, D. G., Vinatzer, B. A., and Monteil, C. L.: Ice nucleation active bacteria in precipitation are genetically diverse and nucleate ice by employing different mechanisms, ISME J., 11, 2740–2753, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.124, 2017. a, b, c

Felgitsch, L., Baloh, P., Burkart, J., Mayr, M., Momken, M. E., Seifried, T. M., Winkler, P., Schmale III, D. G., and Grothe, H.: Birch leaves and branches as a source of ice-nucleating macromolecules, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 16063–16079, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-16063-2018, 2018. a

Fotso, J., Leslie, J. F., and Smith, J. S.: Production of Beauvericin, Moniliformin, Fusaproliferin, and Fumonisins B1, B2, and B3 by Fifteen Ex-Type Strains of Fusarium Species, Appl. Environ. Microb., 68, 5195–5197, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.68.10.5195-5197.2002, 2012. a

Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J., Pickersgill, D. A., Després, V. R., and Pöschl, U.: High diversity of fungi in air particulate matter, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 12814–12819, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0811003106, 2009. a

Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J., Hill, T. C. J., Pummer, B. G., Yordanova, P., Franc, G. D., and Pöschl, U.: Ice nucleation activity in the widespread soil fungus Mortierella alpina, Biogeosciences, 12, 1057–1071, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-12-1057-2015, 2015. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h

Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J., Kampf, C. J., Weber, B., Huffman, J. A., Pöhlker, C., Andreae, M. O., Lang-Yona, N., Burrows, S. M., Gunthe, S. S., Elbert, W., Su, H., Hoor, P., Thines, E., Hoffmann, T., Després, V. R., and Pöschl, U.: Bioaerosols in the Earth system: Climate, health, and ecosystem interactions, Atmos. Res., 182, 346–376, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2016.07.018, 2016. a, b

Fulton, J. D.: Microorganisms of the Upper Atmosphere: IV. Microorganisms of a Land Air Mass as it Traverses an Ocean, Appl. Envrion. Microb., 14, 241–244, 1966. a

Garnham, C. P., Campbell, R. L., Walker, V. K., and Davies, P. L.: Novel dimeric β-helical model of an ice nucleation protein with bridged active sites, BMC Struct. Biol., 11, 36, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6807-11-36, 2011. a

Govindarajan, A. G. and Lindow, S. E.: Size of bacterial ice-nucleation sites measured in situ by radiation inactivation analysis, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 1334–1338, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.85.5.1334, 1988. a, b

Graether, S. P. and Jia, Z.: Modeling Pseudomonas syringae Ice-Nucleation Protein as a β-Helical Protein, Biophys. J., 80, 1169–1173, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76093-6, 2001. a

Green, R. L. and Warren, G. J.: Physical and functional repetition in a bacterial ice nucleation gene, Nature, 317, 645–648, https://doi.org/10.1038/317645a0, 1985. a

Gute, E. and Abbatt, J. P. D.: Oxidative Processing Lowers the Ice Nucleation Activity of Birch and Alder Pollen, Geophys. Res. Lett., 45, 1647–1653, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL076357, 2018. a

Hanlon, R., Powers, C., Failor, K., Monteil, C. L., Vinatzer, B. A., and Schmale, D. G.: Microbial ice nucleators scavenged from the atmosphere during simulated rain events, Atmos. Environ., 163, 182–189, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.05.030, 2017. a

Hasegawa, Y., Ishihara, Y., and Tokuyama, T.: Characteristics of Ice-nucleation Activity in Fusarium avenaceum IFO 7158, Biosci. Biotech. Bioch., 58, 2273–2274, https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.58.2273, 1994. a, b, c, d, e

Hill, T. C. J., Moffett, B. F., DeMott, P. J., Georgakopoulos, D. G., Stump, W. L., and Franc, G. D.: Measurement of Ice Nucleation-Active Bacteria on Plants and in Precipitation by Quantitative PCR, Appl. Environ. Microb., 80, 1256–1267, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02967-13, 2014. a, b

Hill, T. C. J., DeMott, P. J., Tobo, Y., Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J., Moffett, B. F., Franc, G. D., and Kreidenweis, S. M.: Sources of organic ice nucleating particles in soils, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 7195–7211, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-7195-2016, 2016. a, b

Hoose, C. and Möhler, O.: Heterogeneous ice nucleation on atmospheric aerosols: a review of results from laboratory experiments, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 9817–9854, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-9817-2012, 2012. a

Huffman, J. A., Prenni, A. J., DeMott, P. J., Pöhlker, C., Mason, R. H., Robinson, N. H., Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J., Tobo, Y., Després, V. R., Garcia, E., Gochis, D. J., Harris, E., Müller-Germann, I., Ruzene, C., Schmer, B., Sinha, B., Day, D. A., Andreae, M. O., Jimenez, J. L., Gallagher, M., Kreidenweis, S. M., Bertram, A. K., and Pöschl, U.: High concentrations of biological aerosol particles and ice nuclei during and after rain, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 6151–6164, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-6151-2013, 2013. a, b

Humphreys, T. L., Castrillo, L. A., and Lee, M. R.: Sensitivity of Partially Purified Ice Nucleation Activity of Fusarium acuminatum SRSF 616, Curr. Microbiol., 42, 330–338, https://doi.org/10.1007/s002840010225, 2001. a, b

Ichinoe, M., Kurata, H., Sugiura, Y., and Ueno, Y.: Chemotaxonomy of Gibberella zeae with Special Reference to Production of Trichothecenes and Zearalenone, Appl. Environ. Microb., 46, 1364–1369, 1983. a

Irish, V. E., Hanna, S. J., Xi, Y., Boyer, M., Polishchuk, E., Ahmed, M., Chen, J., Abbatt, J. P. D., Gosselin, M., Chang, R., Miller, L. A., and Bertram, A. K.: Revisiting properties and concentrations of ice-nucleating particles in the sea surface microlayer and bulk seawater in the Canadian Arctic during summer, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 7775–7787, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-7775-2019, 2019. a

Joly, M., Amato, P., Deguillaume, L., Monier, M., Hoose, C., and Delort, A.-M.: Quantification of ice nuclei active at near 0 ∘C temperatures in low-altitude clouds at the Puy de Dôme atmospheric station, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 8185–8195, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-8185-2014, 2014. a

Kim, H. K., Orser, C., Lindow, S. E., and Sands, D. C.: Xanthomonas campestris pv. translucens Strains Active in Ice Nucleation, Plant Dis., 71, 994–996, https://doi.org/10.1094/PD-71-0994, 1987. a

King, E. O., Ward, M. K., and Raney, D. E.: Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin, Transl. Res., 44, 301–307, 1954. a

Knopf, D. A., Alpert, P. A., and Wang, B.: The Role of Organic Aerosol in Atmospheric Ice Nucleation: A Review, ACS Earth Sp. Chem., 2, 168–202, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.7b00120, 2018. a

Kohlmeier, S., Smits, T. H. M., Ford, R. M., Keel, C., Harms, H., and Wick, L. Y.: Taking the Fungal Highway: Mobilization of Pollutant-Degrading Bacteria by Fungi, Environ. Sci. Technol., 39, 4640–4646, https://doi.org/10.1021/es047979z, 2005. a

Kokkonen, M., Jestoi, M., and Laitila, A.: Mycotoxin production of Fusarium langsethiae and Fusarium sporotrichioides on cereal-based substrates, Mycotoxin Res., 28, 25–35, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12550-011-0113-8, 2012. a

Kommedahl, T., Windels, C. E., and Stucker, R. E.: Occurrence of Fusarium Species in Roots and Stalks of Symptomless Corn Plants During the Growing Season, Phytopathology, 69, 961–966, 1979. a

Kunert, A. T., Lamneck, M., Helleis, F., Pöschl, U., Pöhlker, M. L., and Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J.: Twin-plate Ice Nucleation Assay (TINA) with infrared detection for high-throughput droplet freezing experiments with biological ice nuclei in laboratory and field samples, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 11, 6327–6337, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-11-6327-2018, 2018. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h

Lagzian, M., Latifi, A. M., Bassami, M. R., and Mirzaei, M.: An ice nucleation protein from Fusarium acuminatum: cloning, expression, biochemical characterization and computational modeling, Biotechnol. Lett., 36, 2043–2051, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-014-1568-4, 2014. a

Leslie, J. F. and Summerell, B. A.: The Fusarium Laboratory Manual, Blackwell Publishing, Ames, Iowa 50014, USA, 2006. a, b, c, d

Lin, B., Bozorgmagham, A., Ross, S. D., and Schmale III, D. G.: Small fluctuations in the recovery of fusaria across consecutive sampling intervals with unmanned aircraft 100 m above ground level, Aerobiologia (Bologna), 29, 45–54, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10453-012-9261-3, 2013. a

Lin, B., Ross, S. D., Prussin, A. J., and Schmale, D. G.: Seasonal associations and atmospheric transport distances of fungi in the genus Fusarium collected with unmanned aerial vehicles and ground-based sampling devices, Atmos. Environ., 94, 385–391, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.05.043, 2014. a

Lindow, S. E., Hirano, S. S., Barchet, W. R., Arny, D. C., and Upper, C. D.: Relationship between Ice Nucleation Frequency of Bacteria and Frost Injury, Plant Physiol., 70, 1090–1093, 1982. a

Ling, M. L., Wex, H., Grawe, S., Jakobsson, J., Löndahl, J., Hartmann, S., Finster, K., Boesen, T., and Šantl‐Temkiv, T.: Effects of Ice Nucleation Protein Repeat Number and Oligomerization Level on Ice Nucleation Activity, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 123, 1802–1810, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JD027307, 2018. a

Liu, F., Lakey, P., Berkemeier, T., Tong, H., Kunert, A. T., Meusel, H., Su, H., Cheng, Y., Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J., Lai, S., Weller, M. G., Shiraiwa, M., Pöschl, U., and Kampf, C. J.: Atmospheric protein chemistry influenced by anthropogenic air pollutants: nitration and oligomerization upon exposure to ozone and nitrogen dioxide, Faraday Discuss., 200, 413–427, https://doi.org/10.1039/C7FD00005G, 2017. a

Möhler, O., DeMott, P. J., Vali, G., and Levin, Z.: Microbiology and atmospheric processes: the role of biological particles in cloud physics, Biogeosciences, 4, 1059–1071, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-4-1059-2007, 2007. a

Morris, C. E., Sands, D. C., Glaux, C., Samsatly, J., Asaad, S., Moukahel, A. R., Gonçalves, F. L. T., and Bigg, E. K.: Urediospores of rust fungi are ice nucleation active at >−10 ∘C and harbor ice nucleation active bacteria, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 4223–4233, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-4223-2013, 2013. a, b

Morris, C. E., Conen, F., Alex Huffman, J., Phillips, V., Pöschl, U., and Sands, D. C.: Bioprecipitation: a feedback cycle linking Earth history, ecosystem dynamics and land use through biological ice nucleators in the atmosphere, Glob. Change Biol., 20, 341–351, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12447, 2014. a, b, c

Murray, B. J., O'Sullivan, D., Atkinson, J. D., and Webb, M. E.: Ice nucleation by particles immersed in supercooled cloud droplets, Chem. Soc. Rev., 41, 6519, https://doi.org/10.1039/c2cs35200a, 2012. a

Nelson, P. E., Dignani, M. C., and Anaissie, E. J.: Taxonomy, biology, and clinical aspects of Fusarium species, Clin. Microbiol. Rev., 7, 479–504, https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.7.4.479, 1994. a

Nirenberg, H. I. and O'Donnell, K.: New Fusarium species and combinations within the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex, Mycologia, 90, 434–458, 1998. a

O'Sullivan, D., Murray, B. J., Malkin, T. L., Whale, T. F., Umo, N. S., Atkinson, J. D., Price, H. C., Baustian, K. J., Browse, J., and Webb, M. E.: Ice nucleation by fertile soil dusts: relative importance of mineral and biogenic components, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 1853–1867, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-1853-2014, 2014. a, b

O'Sullivan, D., Murray, B. J., Ross, J. F., Whale, T. F., Price, H. C., Atkinson, J. D., Umo, N. S., and Webb, M. E.: The relevance of nanoscale biological fragments for ice nucleation in clouds, Sci. Rep.-UK, 5, 8082, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08082, 2015. a, b, c

O'Sullivan, D., Murray, B. J., Ross, J. F., and Webb, M. E.: The adsorption of fungal ice-nucleating proteins on mineral dusts: a terrestrial reservoir of atmospheric ice-nucleating particles, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 7879–7887, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-7879-2016, 2016. a, b

Petters, M. D. and Wright, T. P.: Revisiting ice nucleation from precipitation samples, Geophys. Res. Lett., 42, 8758–8766, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL065733, 2015. a

Pouleur, S., Richard, C., Martin, J.-G., and Antoun, H.: Ice Nucleation Activity in Fusarium acuminatum and Fusarium avenaceum, Appl. Environ. Microb., 58, 2960–2964, 1992. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h

Pratt, K. A., DeMott, P. J., French, J. R., Wang, Z., Westphal, D. L., Heymsfield, A. J., Twohy, C. H., Prenni, A. J., and Prather, K. A.: In situ detection of biological particles in cloud ice-crystals, Nat. Geosci., 2, 398–401, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo521, 2009. a, b

Pruppacher, H. R. and Klett, J. D.: Microphysics of Clouds and Precipitation, Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2nd Edn., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-306-48100-0, 1997. a, b

Prussin, A. J., Li, Q., Malla, R., Ross, S. D., and Schmale, D. G.: Monitoring the Long-Distance Transport of Fusarium graminearum from Field-Scale Sources of Inoculum, Plant Dis., 98, 504–511, https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-06-13-0664-RE, 2014. a

Pummer, B. G., Bauer, H., Bernardi, J., Bleicher, S., and Grothe, H.: Suspendable macromolecules are responsible for ice nucleation activity of birch and conifer pollen, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 2541–2550, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-2541-2012, 2012. a

Pummer, B. G., Atanasova, L., Bauer, H., Bernardi, J., Druzhinina, I. S., Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J., and Grothe, H.: Spores of many common airborne fungi reveal no ice nucleation activity in oil immersion freezing experiments, Biogeosciences, 10, 8083–8091, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-8083-2013, 2013. a

Pummer, B. G., Budke, C., Augustin-Bauditz, S., Niedermeier, D., Felgitsch, L., Kampf, C. J., Huber, R. G., Liedl, K. R., Loerting, T., Moschen, T., Schauperl, M., Tollinger, M., Morris, C. E., Wex, H., Grothe, H., Pöschl, U., Koop, T., and Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J.: Ice nucleation by water-soluble macromolecules, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 4077–4091, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-4077-2015, 2015. a, b, c

Richard, C., Martin, J. G., and Pouleur, S.: Ice nucleation activity identified in some phytopathogenic Fusarium species, Phytoprotection, 77, 83–92, https://doi.org/10.7202/706104ar, 1996. a, b, c, d, e

Sands, D. C., Langhans, V. E., Scharen, A. L., and de Smet, G.: The association between bacteria and rain and possible resultant meteorological implications, J. Hungarian Meteorol. Serv., 86, 148–152, 1982. a

Šantl-Temkiv, T., Sahyoun, M., Finster, K., Hartmann, S., Augustin-Bauditz, S., Stratmann, F., Wex, H., Clauss, T., Woetmann Nielsen, N., Havskov Sorensen, J., Smith Korsholm, U., Wick, L. Y., and Gosewinkel Karlson, U.: Characterization of airborne ice-nucleation-active bacteria and bacterial fragments, Atmos. Environ., 109, 105–117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.02.060, 2015. a

Schmale, D. G. and Gordon, T. R.: Variation in susceptibility to pitch canker disease, caused by Fusarium circinatum, in native stands of Pinus muricata, Plant Pathol., 52, 720–725, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3059.2003.00925.x, 2003. a

Schmale, D. G. and Ross, S. D.: Highways in the Sky: Scales of Atmospheric Transport of Plant Pathogens, Annu. Rev. Phytopathol., 53, 591–611, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-080614-115942, 2015. a

Schmale, D. G., Ross, S. D., Fetters, T. L., Tallapragada, P., Wood-Jones, A. K., and Dingus, B.: Isolates of Fusarium graminearum collected 40–320 meters above ground level cause Fusarium head blight in wheat and produce trichothecene mycotoxins, Aerobiologia (Bologna), 28, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10453-011-9206-2, 2012. a

Schmid, D., Pridmore, D., Capitani, G., Battistutta, R., Neeser, J.-R., and Jann, A.: Molecular organisation of the ice nucleation protein InaV from Pseudomonas syringae, FEBS Lett., 414, 590–594, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01079-X, 1997. a

Schnell, R. C. and Vali, G.: Atmospheric Ice Nuclei from Decomposing Vegetation, Nature, 236, 163–165, https://doi.org/10.1038/236163a0, 1972. a

Schnell, R. C. and Vali, G.: World-wide Source of Leaf-derived Freezing Nuclei, Nature, 246, 212–213, 1973. a

Seinfeld, J. H. and Pandis, S. N.: Atmospheric chemistry and physics – from air pollution to climate change, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1998. a

Sing, D. and Sing, C. F.: Impact of Direct Soil Exposures from Airborne Dust and Geophagy on Human Health, Int. J. Environ. Res. Pu., 7, 1205–1223, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph7031205, 2010. a, b

Stopelli, E., Conen, F., Zimmermann, L., Alewell, C., and Morris, C. E.: Freezing nucleation apparatus puts new slant on study of biological ice nucleators in precipitation, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 7, 129–134, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-7-129-2014, 2014. a, b, c

Stopelli, E., Conen, F., Morris, C. E., Herrmann, E., Bukowiecki, N., and Alewell, C.: Ice nucleation active particles are efficiently removed by precipitating clouds, Sci. Rep.-UK, 5, 16433, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep16433, 2015. a

Stopelli, E., Conen, F., Guilbaud, C., Zopfi, J., Alewell, C., and Morris, C. E.: Ice nucleators, bacterial cells and Pseudomonas syringae in precipitation at Jungfraujoch, Biogeosciences, 14, 1189–1196, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-14-1189-2017, 2017. a

Tesson, S. V. M. and Šantl-Temkiv, T.: Ice Nucleation Activity and Aeolian Dispersal Success in Airborne and Aquatic Microalgae, Front. Microbiol., 9, 2681, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02681, 2018. a

Torp, M. and Nirenberg, H. I.: Fusarium langsethiae sp. nov. on cereals in Europe, Int. J. Food Microbiol., 95, 247–256, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.12.014, 2004. a

Tsumuki, H. and Konno, H.: Ice Nuclei Produced by Fusarium sp. Isolated from the Gut of the Rice Stem Borer, Chilo suppressalis Walker (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), Biosci. Biotech. Bioch., 58, 578–579, 1994. a, b, c, d, e

Tsumuki, H., Konno, H., Maeda, T., and Okamoto, Y.: An ice-nucleating active fungus isolated from the gut of the rice stem borer, Chilo suppressalis Walker (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), J. Insect. Physiol., 38, 119–125, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1910(92)90040-K, 1992. a, b

Tsumuki, H., Yanai, H., and Aoki, T.: Identification of Ice-nucleating Active Fungus Isolated from the Gut of the Rice Stem Borer, Chilo suppressalis Walker (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) and a Search for Ice-nucleating Active Fusarium Species, Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Japan, 61, 334–339, https://doi.org/10.3186/jjphytopath.61.334, 1995. a, b

Vali, G.: Quantitative Evaluation of Experimental Results an the Heterogeneous Freezing Nucleation of Supercooled Liquids, J. Atmos. Sci., 28, 402–409, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1971)028<0402:QEOERA>2.0.CO;2, 1971. a

Wang, B. and Jeffers, S. N.: Fusarium Root and Crown Rot: A Disease of Container-Grown Hostas, Plant Dis., 84, 980–988, https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.9.980, 2000. a

Warmink, J., Nazir, R., Corten, B., and van Elsas, J.: Hitchhikers on the fungal highway: The helper effect for bacterial migration via fungal hyphae, Soil Biol. Biochem., 43, 760–765, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.12.009, 2011. a

Wilson, T. W., Ladino, L. A., Alpert, P. A., Breckels, M. N., Brooks, I. M., Browse, J., Burrows, S. M., Carslaw, K. S., Huffman, J. A., Judd, C., Kilthau, W. P., Mason, R. H., McFiggans, G., Miller, L. A., Nájera, J. J., Polishchuk, E., Rae, S., Schiller, C. L., Si, M., Temprado, J. V., Whale, T. F., Wong, J. P. S., Wurl, O., Yakobi-Hancock, J. D., Abbatt, J. P. D., Aller, J. Y., Bertram, A. K., Knopf, D. A., and Murray, B. J.: A marine biogenic source of atmospheric ice-nucleating particles, Nature, 525, 234–238, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14986, 2015. a

Wing, N., Bryden, W., Lauren, D., and Burgess, L.: Toxigenicity of Fusarium species and subspecies in section Gibbosum from different regions of Australia, Mycol. Res., 97, 1441–1446, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0953-7562(09)80214-1, 1993a. a

Wing, N., Lauren, D. R., Bryden, W. L., and Burgess, L. W.: Toxicity and Trichothecene Production by Fusarium acuminatum subsp. acuminatum and Fusarium acuminatum subsp. armeniacum, Nat. Toxins, 1, 229–234, 1993b. a

Wolber, P. K., Deininger, C. A., Southworth, M. W., Vandekerckhovet, J., Van Montagut, M., and Warren, G. J.: Identification and purification of a bacterial ice-nucleation protein, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 83, 7256–7260, 1986. a

Zachariassen, K. E. and Kristiansen, E.: Ice Nucleation and Antinucleation in Nature, Cryobiology, 41, 257–279, https://doi.org/10.1006/cryo.2000.2289, 2000. a