the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Insights from year-long measurements of air–water CH4 and CO2 exchange in a coastal environment

Thomas G. Bell

Ian J. Brown

James R. Fishwick

Vassilis Kitidis

Philip D. Nightingale

Andrew P. Rees

Timothy J. Smyth

Air–water CH4 and CO2 fluxes were directly measured using the eddy covariance technique at the Penlee Point Atmospheric Observatory on the southwest coast of the United Kingdom from September 2015 to August 2016. The high-frequency, year-long measurements provide unprecedented detail on the variability of these greenhouse gas fluxes from seasonal to diurnal and to semi-diurnal (tidal) timescales. Depending on the wind sector, fluxes measured at this site are indicative of air–water exchange in coastal seas as well as in an outer estuary. For the open-water sector when winds were off the Atlantic Ocean, CH4 flux was almost always positive (annual mean of ∼0.05 mmol m−2 d−1) except in December and January, when CH4 flux was near zero. At times of high rainfall and river flow rate, CH4 emission from the estuarine-influenced Plymouth Sound sector was several times higher than emission from the open-water sector. The implied CH4 saturation (derived from the measured fluxes and a wind-speed-dependent gas transfer velocity parameterization) of over 1000 % in the Plymouth Sound is within range of in situ dissolved CH4 measurements near the mouth of the river Tamar. CO2 flux from the open-water sector was generally from sea to air in autumn and winter and from air to sea in late spring and summer, with an annual mean flux of near zero. A diurnal signal in CO2 flux and implied partial pressure of CO2 in water (pCO2) are clearly observed for the Plymouth Sound sector and also evident for the open-water sector during biologically productive periods. These observations suggest that coastal CO2 efflux may be underestimated if sampling strategies are limited to daytime only. Combining the flux data with seawater pCO2 measurements made in situ within the flux footprint allows us to estimate the CO2 transfer velocity. The gas transfer velocity and wind speed relationship at this coastal location agrees reasonably well with previous open-water parameterizations in the mean but demonstrates considerable variability. We discuss the influences of biological productivity, bottom-driven turbulence and rainfall on coastal air–water gas exchange.

- Article

(1544 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(5738 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2) are two of the most important greenhouse gases (GHGs). Their tropospheric abundances have increased over the last few hundred years primarily due to human activities, with the fastest increases in the last 50 years (Hartmann et al., 2013). Highly dynamic estuarine and coastal regions can be important sources and sinks of these GHGs. Understanding the emissions and uptake of these gases by coastal waters and how they change is directly relevant to the fulfillment of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Paris 2016 agreement. We argue in this paper that the eddy covariance (EC) technique, with a temporal resolution of tens of minutes to hours, is an excellent method for long-term monitoring of coastal air–sea CH4 and CO2 fluxes.

There has been much debate over the causes of the recent tropospheric CH4 trend, from varying wetland (e.g. Pison et al., 2013; Schaefer et al., 2016; Nisbet et al., 2016) and fossil fuel (e.g. Helmig et al., 2016; Rice et al., 2016) emissions to changes in the atmospheric oxidative capacity (e.g. Rigby et al., 2017). Inland aquatic systems may be important sources of tropospheric CH4 (e.g. Borges et al., 2015). Similarly, due to benthic methanogenesis, large surface CH4 supersaturations of thousands of percent have been observed in estuaries (e.g. Upstill-Goddard et al., 2000; Middelburg et al., 2002). CH4 concentrations in estuaries can be influenced by processes including biological productivity, organic-carbon input, benthic and particle-derived CH4 production, oxygen content, and hydrodynamics (e.g. Upstill-Goddard et al., 2000, 2016). In regions of intense benthic methanogenesis, gas bubbles supersaturated with CH4 episodically rise through the water column to the surface (e.g. Dimitrov, 2002; Kitidis et al., 2007). This process of ebullition will result in CH4 emissions that are not quantified using air–sea flux calculations based on seawater CH4 concentration (see below). In coastal seas, CH4 saturation tends to be lower than in estuaries but is still much greater than 100 % (e.g. mean > 200 % for European shelf waters; Bange et al., 2006). Consequently, estuaries and coastal seas tend to have much greater CH4 emissions per unit area than the open ocean (Bange et al., 2006; Forster et al., 2009).

Seawater CO2 levels are primarily determined by solubility (temperature-dependent) and the balance between primary production and respiration by the biological community. Seasonal and geographical differences in seawater temperature and biological activity mean that the surface ocean can act as a net source or sink of CO2, depending on location and time of the year (Khatiwala et al., 2013; Houghton, 2003). Models estimate that 2.4±0.5 GtC yr−1 of CO2 (a quarter of anthropogenic emissions) have been absorbed by the global ocean over the last decade (Le Quéré et al., 2018). Shelf seas, despite their relatively small area, support high primary productivity, cause a large drawdown of CO2 in the mean (Frankignoulle and Borges, 2001; Chen et al., 2013) and might be responsible for as much as 10 %–40 % of global oceanic carbon sequestration (Muller-Karger et al., 2005; Cai et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2009; Laruelle et al., 2010). Estuaries, on the other hand, are generally net sources of CO2 to the atmosphere (e.g. Frankignoulle et al., 1998). Inner estuaries are estimated to emit about 0.3 GtC yr−1 of CO2 globally (Laruelle et al., 2010; Cai 2011). Most of this CO2 emission is due to the degradation of allochthonous organic matter rather than a direct input of dissolved inorganic carbon (Borges et al., 2006). The direction of net air–sea CO2 flux is less certain in coastal areas that are influenced by riverine outflow and anthropogenic activities (Chen et al., 2013). Kitidis et al. (2012) showed a gradient of increasing air-to-sea CO2 flux with distance offshore in the western English Channel. The coastal seas may have been heterotrophic during preindustrial conditions and thus a net source of CO2 due to organic-carbon degradation (e.g. Smith and Hollibaugh, 1993). Some studies (e.g. Andersson and Mackenzie, 2004; Cai, 2011) predict that shallow seas will become a net sink (or a reduced source) of CO2 in the future due to rising atmospheric CO2 levels and increased inorganic nutrient inputs. Modelling of the carbonate chemistry and hence CO2 flux in the northwestern European shelf is hindered partly because of the uncertain representation of riverine influence (Artioli et al., 2012).

To quantify the impacts of estuarine and coastal emissions on the atmospheric CH4 and CO2 burden, an indirect method requiring the inventories of air–sea concentration difference (ΔC) and the gas transfer velocity (K) is usually utilized: Flux . Coastal areas tend to be highly dynamic, with greater spatial and temporal variability in physics and biology than the open ocean. This heterogeneity poses serious challenges to observational and modelling efforts aimed at constraining coastal air–sea GHG fluxes. Dissolved gas concentrations may be affected by tides, currents, mixed-layer processes and benthic–pelagic interactions. The sheltered nature of the coastal seas, coupled with freshwater input, often results in stratification (e.g. Sims et al., 2017), where biological processes can more quickly modify the near-surface dissolved gas concentrations. Mixed-layer dynamics can vary on a diurnal timescale, due for example to buoyancy forcing (e.g. Esters et al., 2018). The atmospheric concentrations of GHGs at coastal locations also vary as a function of wind direction, air mass history and boundary layer processes (e.g. Yang et al., 2016a). Estuaries and coastal seas in mid-latitudes also tend to experience large seasonal variability, which affects the dissolved gas concentrations (e.g. Crosswell et al., 2012; Joesoef et al., 2015).

The transfer velocity (K) primarily depends on near-surface turbulence, and over the ocean it is generally parameterized as a function of wind speed (e.g. Wanninkhof et al., 2009). Currents and resultant bottom-driven turbulence significantly affect gas exchange in shallower waters, resulting in K values that can be much higher than predicted based on wind speed alone (O'Connor and Dobbins, 1958; Borges et al., 2004; Ho et al., 2014). Rainfall is highly episodic but may be important for gas exchange because it generates additional turbulence and/or alters near-surface gas concentrations (e.g. Ho et al., 1997; Zappa et al., 2009; Turk et al., 2010). Variability in biogeochemical processes could also affect K by changing the surface tension and modifying the turbulence at the air–sea interface. Pereira et al. (2016) observed a gradient of increased sea surface surfactant activity from the open sea towards the coast, which reduced the gas transfer velocity by approximately a factor of 2 in their laboratory tank simulations. Thus, a representation of K dependent on wind speed only is probably even less appropriate for coastal environments than for the open ocean.

Measuring the fluxes directly with the eddy covariance technique is an ideal way to study the many controlling factors of air–sea exchange in dynamic and heterogeneous environments such as shallow waters and coastal seas. It also allows us to test the appropriateness of the indirect flux calculations. Furthermore, compared to shipboard EC observations, measuring fluxes from a stationary tower has the advantage of not requiring any motion correction on the winds (see Edson et al., 1998). This means that flux and K measurements at a coastal location are potentially more accurate, especially at high wind speeds when the motion correction for a moving platform would become large. Only a few coastal stations exist worldwide that have reported air–sea CO2 fluxes by EC on a seasonal timescale, such as Östergarnsholm station in the Baltic Sea (Rutgersson et al., 2008), the Utö Atmospheric and Marine Research Station also in the Baltic Sea (Honkanen et al., 2018), Punta Morro in Baja California, Mexico (Gutieìerrez-Loza and Ocampo-Torres, 2016) and Qikirtaarjuk Island in the Canadian Arctic (Butterworth and Else, 2018). In the case of the Östergarnsholm station, concurrent measurements of the partial pressure of seawater CO2 (pCO2) from a nearby buoy allow for the determination of the CO2 gas transfer velocity. CH4 sensors with sufficient measurement frequency and precision for the EC methods have only been developed in recent years (Yang et al., 2016b). We are not aware of any published long-term air–sea CH4 fluxes by the EC method.

In this paper, we describe a year-long set of air–water CO2 and CH4 flux measurements by EC at the coastal Penlee Point Atmospheric Observatory. The high-frequency fluxes allow us to characterize their variability across a range of timescales (semi-diurnal to diurnal to seasonal). Combining these data with in situ observations of dissolved gas concentrations as well as supporting physical and biogeochemical measurements enables us to quantify the gas transfer velocity at this coastal location and examine its controls.

The Penlee Point Atmospheric Observatory (PPAO; 50∘19.08′ N, 4∘11.35′ W; http://www.westernchannelobservatory.org.uk/penlee/, last access: 7 March 2019) was established in May 2014 on the southwest coast of the United Kingdom. Understanding the controls of coastal air–sea exchange is one of the main scientific foci at this site. Yang et al. (2016a, b) demonstrated that the PPAO is a suitable location to measure air–sea exchange by the EC method.

2.1 Eddy covariance fluxes

Atmospheric CH4 and CO2 mixing ratios were measured at a frequency of 10 Hz using a Los Gatos Research (LGR) Fast Greenhouse Gas Analyzer (FGGA, enhanced performance model) between September 2015 and August 2016. As described in detail by Yang et al. (2016a), two Gill sonic anemometers (Windmaster Pro and R3) are installed on a mast on the rooftop of PPAO (∼18 m above mean sea level). For this paper, wind data from the Windmaster Pro sonic anemometer were used between September 2015 and March 2016. Since March 2016, wind data from the R3 sonic anemometer (not operational for the first 6 months of this annual study) were preferred because of its higher precision and better performance during heavy rain events. The effect of rain on the EC gas flux measurement is discussed in the Supplement.

The gas inlet tip, located ∼30 cm below the Windmaster Pro sonic anemometer centre volume, is connected to the LGR via ∼18 m long perfluoroalkoxy (PFA) tubing ( outer diameter). First a scroll pump (BOC Edwards XDS-35i) until 16 October 2015 and then a rotary vane pump (Gast 1023) were used to pull sample air through the inlet tubing, an aerosol filter (2 µm pore size, Swagelok SS-6F-05) and the LGR. The aerosol filter became laden with sea salt over time and the filter elements were replaced approximately every ∼2 months. As a result, the volumetric flow rate through the LGR varied between 23 and 78 LPM (litres per minute), which affected the lag time and the high-frequency attenuation of the fluxes. The lag time was determined from a maximum lag correlation analysis between CO2 and the instantaneous vertical wind velocity (w), varying from about 2.7 to 9.0 s. The strong atmosphere-biosphere flux of CO2 when winds were from land aided our determination of this lag time. The high-frequency flux attenuation was estimated from the instrument response time (see Yang et al., 2013, 2016a) and a wind-speed-dependent correction was applied to the flux data (representing a ∼15 % gain in the mean).

Fluxes of CH4 and CO2 were initially computed in 10 min intervals from the covariance of their lag-shifted dry mixing ratios and w. Wind velocities were streamline corrected using the standard double-rotation method (Tanner and Thurtell, 1969) on a 10 min basis. Evaluations of the EC momentum transfer against the expected rate (Fig. S2 in Supplement), as well as stationarity in winds and gas mixing ratios, are used to quality control the 10 min flux data. The filtered 10 min fluxes are further averaged to hourly and also 6-hourly intervals to reduce random noise. See Yang et al. (2016a, b) for further details on data processing, quality control, and measurements of momentum and sensible heat fluxes. Horizontal wind speed measurements are corrected for flow distortion and adjusted to a neutral atmosphere at 10 m height (see Supplement).

2.2 Flux footprints

The theoretical flux footprint model of Kljun et al. (2004) predicts the upwind distance of maximum flux contribution (Xmax) and the distance of 90 % cumulative flux contribution (X90). The semi-diurnal tidal range at this location is large (up to 6 m during spring tide), effectively raising the EC measurement height above water at low tide and reducing it at high tide. For a neutral atmosphere, the Kljun et al. (2004) model estimates Xmax and X90 to be approximately 0.4 and 1.1 km at the highest tide and 0.6 and 1.6 km at the lowest tide. As described in more detail by Yang et al. (2016a), stable and unstable atmospheres are predicted to increase and decrease Xmax as well as X90 by a few tens of percent, respectively.

In this paper we focus on air–water transfer over two different wind sectors. When winds are from the southwest (180–240∘), the eddy covariance flux footprint is over open water with a depth of approximately 20 m at Xmax. When winds are from the northeast (45–80∘), the footprint is over the fetch-limited Plymouth Sound (approximately 5–6 km wide), which is ∼10 m deep and more influenced by the outflow of the Tamar estuary (Siddorn et al., 2003; Uncles et al., 2015). See Fig. S1 for a map of the site and the approximate flux footprints.

2.3 Seawater measurements

We used the Plymouth Marine Laboratory's research vessels (RVs) Quest and Plymouth Explorer to study the spatial heterogeneity in this coastal environment. Underway seawater measurements on the Quest from ∼3 m depth include pCO2 (Kitidis et al., 2012), salinity, temperature, chlorophyll and dissolved oxygen. As a part of the Western Channel Observatory sampling program (http://www.westernchannelobservatory.org.uk, last access: 7 March 2019), the Quest made approximately weekly trips to the L4 station (50∘15.0′ N, 4∘13.0′ W; ∼6 km south of PPAO) and fortnightly trips to the E1 station (50∘02.6′ N, 4∘22.5′ W; ∼20 km south of PPAO). These visits were always during the daytime. On the way back to Plymouth from L4 and E1, the Quest often idled at about 600 m to the south/southwest of PPAO for approximately 10 min, enabling the collection of underway measurements within the open-water flux footprint of PPAO. The ship also passed through the Plymouth Sound flux footprint of PPAO en route back into port.

Seawater samples were taken at the L4 station from a CTD rosette. For CH4 analysis, discrete seawater samples were collected directly into 500 mL borosilicate bottles from Niskin bottles using clean Tygon tubing. Sample bottles were overfilled by 3 times their volume to eliminate air bubbles, poisoned with 100 µL of a saturated mercuric chloride solution and returned to the laboratory where they were transferred to a water bath at 25 ∘C and temperature equilibrated for a minimum of 1 h before analysis. Samples were analysed for CH4 by single-phase equilibration gas chromatography using a flame ionization detector similar to that described by Upstill-Goddard et al. (1996). Samples were typically analysed at Plymouth Marine Laboratory (PML) within 2 weeks of collection and calibrated against three certified (±5 %) reference standards (Air Products Ltd), which are traceable to NOAA WMO-N2O-X2006A.

The other PML vessel, a hard-bottomed Rigid Hull Inflatable Boat (RHIB, Plymouth Explorer), was used to occasionally sample the estuary Tamar from the upper freshwater section near Gunnislake to the lower saltwater section near the Plymouth Sound in 2017 and 2018. This is a part of the NERC-funded LOCATE (Land Ocean Carbon Transfer; http://www.locate.ac.uk, last access: 7 March 2019) research programme. Discrete seawater samples were collected at stations from the near surface into 500 mL borosilicate bottles with care taken to eliminate air bubbles. Analysis for dissolved CH4 was performed as described above.

Over the 1 year of measurements, variability in physical parameters was large: wind speed at times exceeding 20 m s−1, and seawater temperature varying between about 7 ∘C and 18 ∘C. Chlorophyll a concentration ranged between about 0.2 and 5 mg m−3, with generally higher values from late spring to early autumn than in winter. Time series of ancillary data (meteorological parameters, Tamar river flow, and surface ocean physical and biogeochemical parameters) are shown in the Supplement (Figs. S3 to S6). This region can be roughly characterized by a windier, wetter autumn and winter and a calmer, dryer spring and summer. Southwesterly winds off the Atlantic Ocean (annual mean wind speed of ∼8 m s−1) occurred more frequently in the winter months, resulting in higher precipitation rates and greater riverine discharge. During these conditions, the temperatures in the sea surface and air were similar throughout the entire year, resulting in fairly small air–sea temperature differences and modest sensible heat fluxes (monthly average of typically −20 to 20 W m−2). As a result, the atmosphere was often close to neutral stability with a monthly mean Monin–Obukhov stability parameter (z∕L) between −1.7 and 0.04.

3.1 CH4 fluxes and implied seawater concentrations

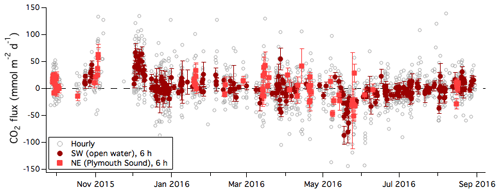

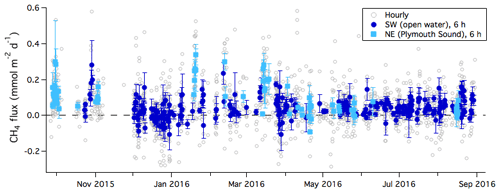

Figure 1 shows the air–sea flux of CH4 over the 1-year measurement period. Flux data gaps are due to either wind direction outside of air–water sectors or instrumental failure. As shown by Yang et al. (2016b), under ideal conditions (moderate winds and steady atmospheric mixing ratio) the random uncertainty in the LGR CH4 flux due to band-limited instrumental noise is on the order of 0.02 and 0.01 mmol m−2 d−1 for a 1 h average and a 6 h average, respectively. In comparison, the standard deviation (σ) in the 6 h averaged CH4 flux for the open-water sector is about 0.05 mmol m−2 d−1 (computed over the entire year). Thus, much of the rapid temporal fluctuations in the measured CH4 flux appear to be driven by natural variability (due to changes in water mass within the flux footprint, wind, etc.), rather than due to random instrumental noise. CH4 flux from the open-water sector at times shows semi-diurnal (tidal) variability (consistent with Yang et al., 2016a). We note that most of what appear to be negative CH4 fluxes are within the uncertainty of the EC measurement and are not significantly different from zero.

Figure 1One-year time series of CH4 flux (hourly average) during times when winds were from the sea. Six-hour averages of fluxes are further separated into the southwest (open water) and northeast (Plymouth Sound) wind sectors. Error bars indicate standard error.

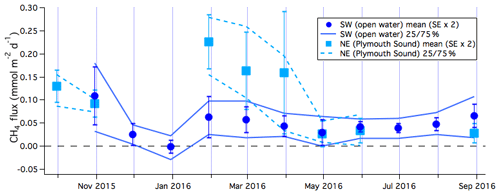

To more clearly illustrate the seasonal variability, the means and 25th and 75th percentiles of the 6 h averaged CH4 fluxes are computed in monthly intervals (Fig. 2). CH4 flux was consistently positive, indicating emission of CH4 from these coastal waters. The only exception was during the months of December and January, when CH4 flux was near zero. The annual mean CH4 flux from the open-water sector was 0.047 (standard error, or SE, of 0.008) mmol m−2 d−1 when computed from monthly mean fluxes and 0.039 (SE of 0.003) mmol m−2 d−1 when directly computed from 6 h mean fluxes. Wind directions that enable air–sea flux measurements did not occur with the same frequency throughout the year. For example, southwesterly winds were less frequent in spring (30 % of the time in March–May 2016) than in winter (60 % of the time in January 2016). Thus, annual averages computed directly from the 6 h fluxes are more heavily weighted by the periods with a high proportion of valid flux measurements. In contrast, annual averages computed from the monthly means give more equal weight to all the months. The annual mean CH4 flux here is largely consistent with previous coastal estimates (e.g. Upstill-Goddard et al., 2016) and roughly 1 order of magnitude greater than estimates of CH4 flux for the open ocean (e.g. Forster et al., 2009).

Figure 2Monthly averages and 25th and 75th percentiles (designated 25/75 % in the figure) of CH4 flux from the southwest (open water) and northeast (Plymouth Sound) wind sectors. Error bars indicate 2 times standard error.

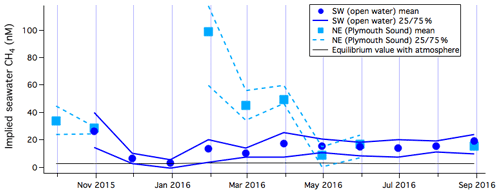

Figure 3Monthly averages and 25th and 75th percentiles of implied CH4 concentration for the southwest (open water) and northeast (Plymouth Sound) wind sectors, along with the equilibrium value with respect to the atmosphere.

CH4 flux from the Plymouth Sound sector was noticeably higher than flux from the open-water sector, with an annual mean of about 0.108 (SE of 0.026) mmol m−2 d−1. This enhancement in the flux was particularly noticeable at times of high rainfall and river discharge rate, with fluxes over 0.2 mmol m−2 d−1 in February 2016. During the dry summer months of 2016 (May and June), CH4 fluxes from the two wind sectors were comparable. Northerly winds occurred only 7.4 % of the time overall during the 1-year study period. Thus, the seasonal variability in CH4 emission from the Plymouth Sound is less well represented than emission from the open-water sector.

We briefly compare our measured fluxes with existing estimates of riverine CH4 emission. The 1 km2 resolution UK National Atmospheric Emissions Inventory (NAEI, http://naei.defra.gov.uk, last access: 7 March 2019) reports a natural CH4 emission source of 0.17 mmol m−2 d−1 averaged over the area of the Plymouth Sound for the year 2013. Our annual mean flux from the Plymouth Sound wind sector is about 64 % of the NAEI estimate. Based on in situ measurements of dissolved CH4 concentrations in six major UK estuaries, Upstill-Goddard et al. (2016) estimated CH4 emissions of 4.3 Gg yr−1 for UK outer estuaries (using a total outer estuarine area of 1894 km2). If we crudely assume that the Plymouth Sound is a representative outer UK estuary, scaling up our mean flux from this wind sector to the total outer estuarine area of 1894 km2 yields an annual flux of 1.2 Gg yr−1. This is lower than the estimate from Upstill-Goddard et al. (2016), likely because according to their survey the CH4 saturation from the Tamar is fairly low compared to some of the other major UK estuaries. The UK has a 12 429 km long coastline. If the PPAO open-water footprint is representative of the nearest 1.4 km (i.e. typical X90 of our fluxes; see Sect. 2.2) of the UK coast, our measurements crudely extrapolate to a total CH4 flux of 4.8 Gg yr−1 for the UK coastal seas. This order-of-magnitude estimate is made from a mean flux of 0.047 mmol m−2 d−1 and a total coastal sea area of 12 429 km by 1.4 km. We are not able to use PPAO EC flux data to provide estimates for CH4 emission from the inner estuary, where fluxes are likely higher per unit area (Upstill-Goddard et al., 2016).

We wish to disentangle the processes that control the gas transfer velocity (K) from the processes that control the air–water concentration difference (ΔC). We first compute the implied seawater CH4 and CO2 concentrations from the eddy covariance fluxes by assuming a parameterization of the gas transfer velocity. Here the sea-minus-air concentration difference (ΔC) is computed by dividing the EC flux by the wind-speed-dependent K from Nightingale et al. (2000) (adjusted for ambient Schmidt number by the exponent of −0.5). Adding the atmospheric concentration to ΔC yields the implied seawater concentration. At low wind speeds, both the flux and K trend towards zero. To avoid excessive noise from dividing one small number by another, implied seawater concentrations at wind speeds lower than 5 m s−1 are discarded. Note that we apply the Nightingale et al. (2000) wind-speed-based K parameterization here largely because it is commonly used and lies between the very strong and the very weak wind-speed-dependent relationships.

Implied seawater CH4 concentration from the open-water flux footprint ranges from about 3 to 26 nM on a monthly interval (mean of 14 nM; see Fig. 3). It is often convenient to represent dissolved CH4 as a saturation level relative to the atmosphere (saturation = , where CH4w and CH4a are waterside and airside concentrations; is the CH4 solubility from Wanninkhof, 2014). CH4 saturations are shown in Fig. S8. The lowest implied CH4 concentration occurred in winter and corresponded to a saturation level close to 100 %. The highest implied CH4 concentration was from April to November, with an average saturation level of about 600 %. The temperature and salinity-dependent solubility of CH4 varies by only ∼14 % from summer to winter at this location. The seasonal variability in CH4 concentration and saturation is thus more due to changing biological processes (methanogenesis and/or CH4 oxidation) and hydrodynamics than due to dissolution (i.e. seasonal temperature changes). For the Plymouth Sound flux footprint, the implied concentration ranges from 9 to 99 nM (mean of 37 nM, corresponding to about 1200 % saturation), with the highest values in late winter and early spring. These implied concentrations and saturations are compared with nearby dissolved CH4 measurements in Sect. 3.3.3. We note that any contribution to CH4 emission from ebullition would have been included in the EC flux measurements, potentially resulting in higher implied seawater CH4 concentrations than the measured dissolved concentrations.

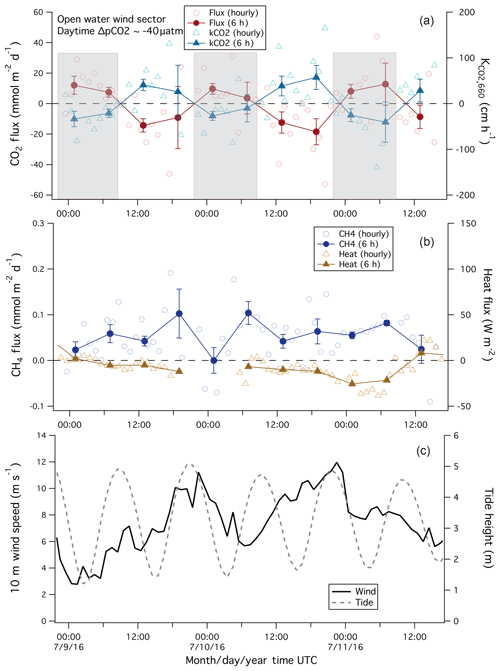

Based on measurements from April to June 2015 at PPAO, Yang et al. (2016a) observed that CH4 flux from the open-water flux footprint varied with the timing of the tide but not with the tide height. Specifically, CH4 flux tended to be the highest during the first ∼4 h after low water. This was attributed to the outflow of a lower-salinity surface layer from the Tamar river during rising tide around the Penlee headland. A subtle semi-diurnal variability in CH4 flux can be seen in Fig. 6b, where adjacent 6 h mean fluxes always alternated between higher and lower values during these few days. The same general tidal pattern is apparent over an annual cycle in the implied saturation level of CH4. On average, the implied CH4 saturation within the open-water sector was about 40 % higher during rising tide than during falling tide.

3.2 CO2 fluxes and implied seawater concentrations

Figure 4 shows the air–sea flux of CO2 over the 1-year measurement period. The random uncertainty in the LGR CO2 flux, estimated from the band-limited instrumental noise, is on the order of 4 and 2 mmol m−2 d−1 for 1 h average and 6 h average measurements, respectively (Yang et al., 2016b). The standard deviation in the 6 h averaged CO2 flux for the open-water sector is about 20 mmol m−2 d−1 (computed over the entire year), substantially greater than the random uncertainty due to instrumental noise. The rapid temporal fluctuations in CO2 flux are likely to be driven by variability in winds as well as variability in seawater pCO2. The latter is unlikely to be fully captured by weekly or monthly seawater sampling.

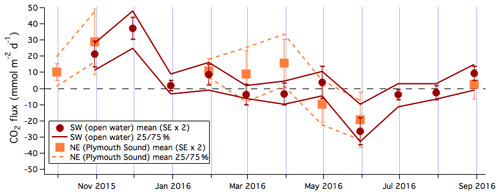

The means and 25th and 75th percentiles of the 6 h averaged CO2 fluxes are computed in monthly intervals (Fig. 5). CO2 flux from the open-water sector was generally from sea to air in autumn and winter (up to 37 mmol m−2 d−1) and from air to sea in spring and early summer (as much as −26 mmol m−2 d−1). The seasonality in CO2 flux is consistent with seawater pCO2 observations by Litt et al. (2010) and Kitidis et al. (2012) from the same region and is partly driven by biology. Figure S7 shows that in situ pCO2 generally decreased with increasing chlorophyll a concentrations during this annual study. CO2 flux from the Plymouth Sound sector appeared to be more positive than from the open-water sector in some months.

Figure 5Monthly averages and 25th and 75th percentiles of CO2 flux from the southwest (open water) and northeast (Plymouth Sound) wind sectors. Error bars indicate 2 times standard error.

Figure 6Example of variability in: (a) CO2 flux and computed transfer velocity; (b) CH4 flux and sensible heat flux; and (c) wind speed and tidal height during a period of southwesterly winds. Fluxes are shown in both hourly and 6 h averages. Note that the negative transfer velocity (K) values at night (shaded) computed from the measured CO2 flux and interpolated daytime pCO2 are non-physical, and likely due to unaccounted for diurnal variability in seawater pCO2.

A 3-day time series of CO2 flux from July 2016 is shown in Fig. 6a. Winds were consistently from the southwest during this period, varying from about 3 to 12 m s−1 (Fig. 6c). CO2 flux during this period was clearly different between day (mean of about −13 mmol m−2 d−1) and night (mean of about +9 mmol m−2 d−1), with an overall mean of about −2 mmol m−2 d−1. Daytime pCO2 measurements on the Quest from the 7 and 12 July imply a ΔpCO2 of about −40 µatm and a net flux into the water. The EC flux is consistent in sign with ΔpCO2 during the day but not at night. The computed transfer velocity of CO2 (, see Sect. 3.4) using the linearly interpolated daytime pCO2 measurements yielded positive values during the day (as expected) but negative values at night (which is not physically possible). The positive CO2 flux at night is unlikely to be caused by a nocturnal flux footprint that overlaps with land because both sensible heat and CH4 fluxes are consistent with air–sea exchange. The air temperature was about 1.2 ∘C warmer than the water temperature, implying a slightly stable atmosphere and a flux footprint that extends a few tens of percent further upwind from the PPAO site than in a neutral atmosphere (Kljun et al., 2004). The measured sensible heat flux averaged −9 W m−2 and showed little diurnal variability. Similarly, CH4 flux was positive (sea to air) and did not vary with the time of day.

The most likely reason for the negative nighttime is that seawater pCO2 varied diurnally, probably due to a combination of biological and dynamical processes. Wind speed was generally higher at night during these few days and the measured fluxes imply that the actual ΔpCO2 changed from about −40 µatm during the day to about 15 µatm at night. Similar diurnal cycles (with slightly reduced magnitudes) have been observed in pCO2 measurements in the western English Channel by Marrec et al. (2014) and Litt et al. (2010). We note that a daytime CTD cast on 12 July 2016 showed a mixed layer at the L4 station of only ∼10 m depth. Entrainment of deeper water could contribute towards a higher surface pCO2 at night. A diurnal cycle in CO2 flux was not obvious during times of expected evasion (sea-to-air flux). These periods of positive CO2 flux occurred in autumn and winter when biological productivity was low and the water column was mixed to the bottom.

The annual mean CO2 flux was 3.9 (SE of 4.9) mmol m−2 d−1 when computed from monthly mean fluxes (Fig. 5) and 1.3 (SE of 1.3) mmol m−2 d−1 when directly computed from 6 h mean fluxes. If we subsample our EC observations to the period of 10:00–16:00 UTC only, the annual mean CO2 flux becomes 2.5 (SE of 4.9) mmol m−2 d−1 when computed from monthly mean fluxes and −1.0 (SE of 2.2) mmol m−2 d−1 when directly computed from 6 h mean fluxes. These results highlight the value of continuous flux measurements and suggest that CO2 flux estimates based only on daytime pCO2 measurements may be biased towards greater seawater net uptake for coastal environments such as the western English Channel.

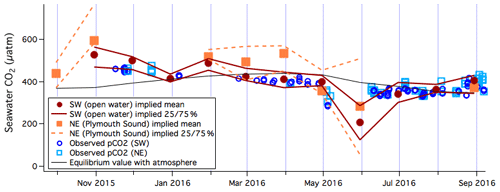

Monthly averaged implied seawater CO2 concentrations from the two flux footprints are shown in Fig. 7. The greatest supersaturation in CO2 is observed in late autumn in the open-water sector, with values exceeding 500 µatm. The greatest undersaturation in CO2 is observed in late spring and early summer, coinciding with an increase in chlorophyll a concentration at the nearby L4 station (Fig. S6). Average implied pCO2 within the Plymouth Sound is 32 µatm higher than pCO2 within the open-water flux footprint during months when fluxes were available for both wind sectors. This difference between the outer estuary and the coastal seas qualitatively agree with previous observations of supersaturated pCO2 in the river Tamar (Frankignoulle et al., 1998).

Figure 7Monthly averages and 25th and 75th percentiles of implied seawater pCO2 for the southwest (open water) and northeast (Plymouth Sound) wind sectors. Observed pCO2 from the Plymouth Quest within the southwest sector (plus at L4) and within the northeast sector are also shown, along with the equilibrium value with respect to the atmosphere.

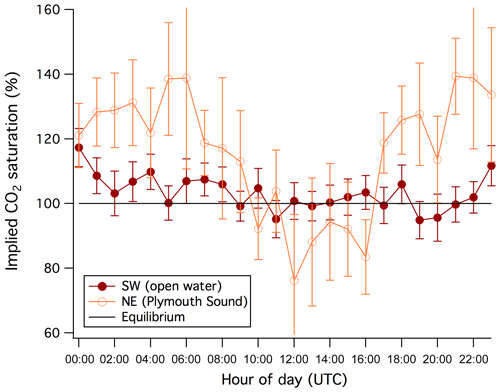

Average implied seawater CO2 saturation for the open-water sector over the entire year is about 100 % in the daytime and slightly higher at night (Fig. 8). In contrast, a marked diurnal variability in CO2 saturation is observed for the Plymouth Sound sector, with a higher saturation level at night than during the day. Compared to the open-water sector, Plymouth Sound is more sheltered and influenced by the Tamar outflow and thus subject to greater near-surface stratification and possibly different biological processes. The diurnal variability we observed is important in the context of estuarine CO2 (and carbonate system) observations that are only carried out during daytime. Our findings suggest that such a daytime-only monitoring strategy may underestimate estuarine pCO2 and by extension the efflux of CO2 to the atmosphere.

Figure 8Mean diurnal variability in the implied seawater saturation of CO2 for the for the southwest (open water) and northeast (Plymouth Sound) wind sectors. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Semi-diurnal variability as a result of the tide is not obvious in the CO2 flux or the implied CO2 saturation. This suggests that the influence of the Tamar estuary on pCO2 within the PPAO flux footprints is limited, consistent with the in situ pCO2 measurements (see Sect. 3.3.2). The diurnal variability in pCO2 might also be confounding any semi-diurnal tidal signal.

It is worth noting that our implied seawater GHG concentrations would be overestimated if the in situ gas transfer velocity were higher than the wind-speed-dependent parameterization of Nightingale et al. (2000). For example, bottom-driven turbulence could enhance the gas transfer velocity (e.g. Borges et al., 2004; Ho et al., 2014). We discuss the effects of depth and current velocity on gas exchange in Sect. 3.4.3.

3.3 Spatial homogeneity of the study region

The estimation of the gas transfer velocity K requires concurrent measurements of flux and seawater concentration within the flux footprint. Seawater pCO2 was typically measured once or twice a week, and only some of the measurements were made within the PPAO flux footprints. Observations of dissolved CH4 were even scarcer and unfortunately none of them were made within the flux footprints. In order to relate the high-frequency EC fluxes to the discrete in situ dissolved gas concentrations, we first evaluate the spatial homogeneity of our study region using shipboard seawater measurements.

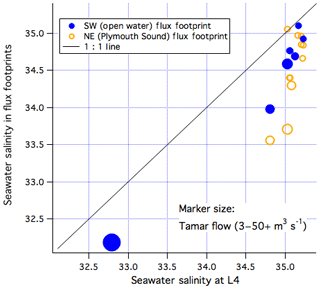

3.3.1 Variability in salinity

Previous modelling studies (Siddorn et al., 2003; Uncles et al., 2015) show that freshwater discharge from the Tamar estuary mainly flows along the western edge of Plymouth Sound and bends around PPAO towards the southwest. In Fig. 9, we compare underway salinity measured within the PPAO flux footprints (open water to the southwest as well as the Plymouth Sound to the northeast) with near-coincidental Quest observations at the L4 station (6 km south of PPAO). Compared to the L4 station, mean salinity was 1.2 % and 2.1 % lower in the open water and Plymouth Sound footprints, respectively. Periods of low salinity both within the footprints and at L4 coincided with the greatest outflow from the Tamar estuary. These observations indicate that the Tamar outflow influences this entire region; unsurprisingly water is generally fresher within the Plymouth Sound than in the open-water flux footprint. We next assess how much this riverine outflow affects the seawater CO2 and CH4 concentrations within the flux footprints of PPAO and thus the measured fluxes.

3.3.2 Variability in seawater pCO2

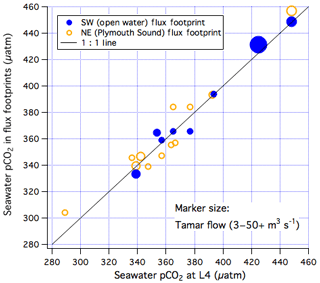

The underway in situ pCO2 measured within the PPAO flux footprints is compared with near-coincidental observations from the Quest at the L4 station in Fig. 10. The highest pCO2 measured both within the footprints and at L4 occurred at times of large riverine discharge. This is seemingly consistent with a Tamar influence (e.g. Frankignoulle et al., 1998) but may also be driven by the seasonality in pCO2 (Kitidis et al., 2012). As shown in Figs. S9–S11, fast responding sea surface temperature and chlorophyll a were not noticeably different between the flux footprints and L4, while dissolved oxygen was slightly lower within the footprints. pCO2 measurements within both flux footprints were very similar to pCO2 at the L4 station. The apparent agreement for pCO2 could be in part because the measurement with a “shower head” equilibrator has an integration time of 8 min (Kitidis et al., 2012). The Quest usually only idled for ∼10 min within the open-water flux footprint and did not idle within the Plymouth Sound footprint. It is possible that the pCO2 spatial variability is under-represented in the pCO2 measurements due to the fairly slow response time of the equilibrator.

Figure 10pCO2 measured within the two air–water flux footprints of Penlee vs. near-coincidental measurements from the Quest at the L4 station. The size of the markers corresponds to the flow rate in the Tamar river, as measured at Gunnislake.

In situ pCO2 measurements from the Plymouth Sound footprint and from the open-water footprint (plus L4, since they are not distinguishable) are shown in Fig. 7, along with the 100 % saturation value with respect to the atmosphere. Implied pCO2 for the open-water sector and the in situ pCO2 within the open-water footprint (plus L4) broadly agree. Constraining the implied pCO2 estimate to during the day further improves the agreement with the in situ pCO2 measurements (also daytime only; see Sect. 3.2). These observations suggest that the direct impact of the Tamar outflow on pCO2 in the open-water flux footprint at PPAO is fairly small relative to the air–sea concentration difference as well as other sources of variability.

3.3.3 Variability in dissolved CH4

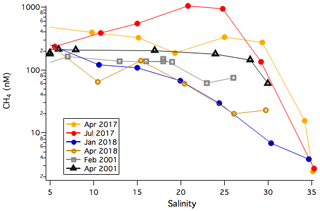

Dissolved CH4 was not measured within either of the PPAO flux footprints. Here we look at how our implied CH4 concentrations from the fluxes compare to measurements of dissolved CH4 in the river Tamar and at L4. On four separate days in April 2017, July 2017, January 2018 and April 2018, the Plymouth Explorer was used to sample dissolved CH4 from the upper reaches of the Tamar to the seaward end during a falling tide. CH4 in the estuarine part of the Tamar in general correlated inversely with salinity (Fig. 11). For example, in April 2017 the CH4 concentration was 491 nM at a salinity of 4.7 (upper Tamar), 274 nM at a salinity of 29.3 (lower Tamar), 15 nM at a salinity of 34.2 (at the mouth of the Tamar in the Plymouth Sound) and 2.4 nM at a salinity of 35.2 (L4). These correspond to CH4 saturation values of ∼10 000 % at a salinity of 29.3 and ∼600 % at a salinity of about 34.2 during this transect. The highest CH4 concentration was measured in July 2017 following heavy rainfall, while relatively low CH4 were observed in January and April 2018. The measurements from the river Tamar in 2001 by Upstill-Goddard et al. (2016) are within the range of these more recent transects. Long-term observations of surface dissolved CH4 at L4 between October 2013 and July 2017 indicate a mean (±σ) saturation of 123±60 %.

Figure 11Dissolved CH4 concentration from the Tamar river to the L4 station varies with salinity. Data from 2017 and 2018 were made during LOCATE sampling. The 2001 data are taken from Upstill-Goddard et al. (2016).

The implied seawater CH4 concentrations for the Plymouth Sound sector (Sect. 3.1) are within range of the in situ measurements in the lower Tamar and near the Plymouth Sound. In contrast, implied seawater CH4 concentrations for the open-water sector are on average about 4 times higher than the in situ measurements at L4. Thus, while pCO2 within the open-water flux footprint of the PPAO agrees reasonably well with pCO2 at L4, this is very likely not the case for CH4. The differences in salinity (Fig. 9) and in dissolved oxygen (Fig. S11) indicate that the water masses within the open-water flux footprint and at L4 are not identical.

Two features of the CH4 concentration and salinity relationship are particularly relevant for the interpretation of our CH4 flux measurements. First, the variability in dissolved CH4 concentration in the Tamar is very large. For example, CH4 concentration at a salinity of about 30 varies by a factor of 40 during the six transects. The interannual variation in CH4 concentration during April in 2001, 2017 and 2018 at this salinity is a factor of 12. Secondly, the horizontal gradient in CH4 concentration near the mouth of the Tamar estuary is very steep. Observations from April and July 2017 show a slope of between −20 and −50 nM per salinity unit. Salinity within the open-water flux footprint varied between 32.2 and 35.2 between September 2015 and August 2016, while salinity within the Plymouth Sound flux footprint varied between 32.0 and 35.1. The large range in CH4 concentration and the strong and variable CH4 and salinity relationship make any salinity-based prediction of dissolved CH4 concentration within the flux footprints highly uncertain. Thus, we focus on estimating the transfer velocity of CO2 but not CH4 in the next section.

3.4 CO2 gas transfer velocity

The implied pCO2 from EC fluxes and in situ measured pCO2 agree quite well over the annual cycle for the open-water sector (Fig. 7), suggesting that the use of the wind-speed-dependent transfer velocity parameterization of Nightingale et al. (2000) is largely reasonable in the mean. The variability in the implied pCO2 (as indicated by the 25th and 75th percentiles), however, is sometimes greater than the variability in the in situ pCO2. In this section, we estimate the time-varying CO2 gas transfer velocity () and examine its variability and possible controls.

is computed as flux , where sol is the solubility of CO2 in water. As shown in Sect. 3.3.2, pCO2 measured from the open-water flux footprint of PPAO is comparable to near-coincidental measurements at L4. Thus, to estimate for the open-water sector, we combine pCO2 measurements from the open-water footprint with the more numerous measurements at L4. To estimate for the Plymouth Sound sector, only pCO2 measurements from that footprint are used. We linearly interpolate these seawater pCO2 measurements to the times of the hourly CO2 flux measurements. Interpolation more than 4 days away from the nearest pCO2 observations is discarded. We chose 4 days (ca. half a week) here such that the computed values are retained if made between weekly pCO2 measurements. The interpolated pCO2 is then combined with the measured atmospheric CO2 mixing ratio at PPAO to yield the air–sea pCO2 difference (ΔpCO2). To normalize for the effect of temperature, is further adjusted to the Schmidt number of 660 (). The CO2 solubility and Schmidt number as a function of temperature and salinity are taken from Wanninkhof et al. (2014). In order to minimize any bias in the computed due to the interpolation of daytime only pCO2 measurements (see Sect. 3.2), we discard the nighttime (20:00 to 08:00 UTC) data during times of expected invasion (i.e. air-to-sea flux). The filtered hourly data are then averaged into 6 h bins to reduce random noise.

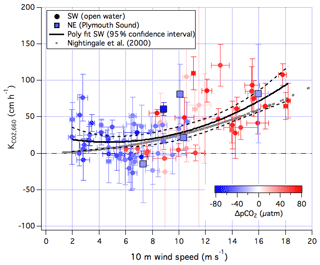

3.4.1 Dependence of on wind speed and friction velocity

is plotted against the 10 m neutral wind speed (U10n) in Fig. 12, along with a second-order polynomial fit. We have retained data here only when the absolute value of ΔpCO2 exceeded 20 µatm. This threshold is chosen as a balance between minimizing errors and maximizing data retention. A higher threshold (e.g. 40 µatm) does not obviously reduce the scatter in the and wind speed relationship. Error bars in are propagated from the standard errors in the fluxes. For the open-water sector, shows a significant non-linear increase with wind speed (R2=0.35, p< 0.0001). The scatter in the and wind speed relationship is likely due to a combination of random uncertainties in the flux measurement (Yang et al., 2016b) and variability in seawater pCO2 not captured by the weekly measurements, as well as processes other than wind speed that affect gas exchange (see below). for the Plymouth Sound sector will be discussed in Sect. 3.4.3 within the context of bottom-driven turbulence.

Figure 12CO2 transfer velocity (normalized to a Schmidt number of 660) vs. 10 m neutral wind speed for both the southwest (open water) and northeast (Plymouth Sound) wind sectors. Note that colour-coding is capped at values of 80 µatm for clarity.

The mean of the and wind speed relationship, as represented by the second-order polynomial fit, agrees (within a 95 % confidence interval) with the widely used relationship derived by Nightingale et al. (2000) using the dual-tracer (3He∕SF6) technique. We note that more recent parameterizations of the gas transfer velocity based on 3He∕SF6 and radiocarbon budgets (Ho et al., 2006; Sweeney et al., 2007; Wanninkhof 2014) are largely similar to Nightingale et al. (2000). In moderate to high winds, measured increases with wind speed at a rate that is less than cubic – a power fit yields an exponent of 1.3. This is generally consistent with other recent closed-path EC CO2 transfer velocity measurements (Butterworth and Miller, 2016; Bell et al., 2017; Blomquist et al., 2017; Landwehr et al., 2018).

At wind speeds less than ∼5 m s−1, measured at the PPAO are sometimes elevated and might not be entirely representative of air–sea transfer (Yang et al., 2016a). The EC friction velocity in the open-water sector (see below and in Fig. S2) is also at times higher than expected at these low wind speeds. The atmosphere was often more unstable at low wind speeds (z∕L of ), in part because low winds occurred more frequently during the warmer months. The Kljun et al. (2004) model predicts a flux footprint that is closer to the PPAO site during these conditions, such that the near-shore environment (i.e. from the mast to the water's edge) might have some influence on the fluxes. Furthermore, the double-rotation method used for the streamline correction of wind may be more uncertain at lower wind speeds. The planar fit method (Wilczak et al., 2001) could be superior under these conditions and will be an area of investigation during future analyses of PPAO flux data.

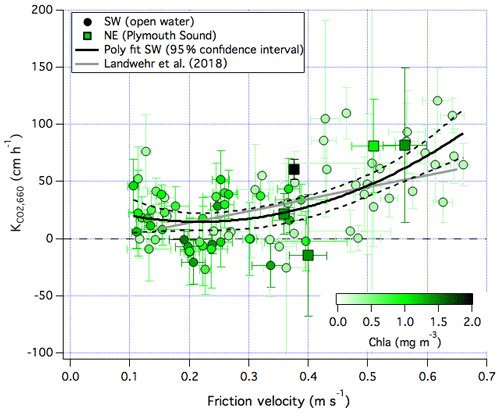

The friction velocity (u∗), a measure of air–sea total momentum transfer, is long thought to be a more direct representation of the drivers of turbulence and gas exchange than wind speed (e.g. Csanady et al., 1990). This appears to be the case especially for moderately soluble gases that are not significantly affected by bubble-mediated gas transfer, such as dimethyl sulfide (Huebert et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2011). The relationship between and the EC-derived u∗ shows a slightly better fit (R2=0.38; Fig. 13) than between and U10n (R2=0.35). This is consistent with the idea that u∗ is a more suitable predictor of K than wind speed. The other benefit of relating with u∗ instead of U10n is that the u∗ measurement may be less affected by flow distortion than the U10n measurement (Landwehr et al., 2018).

Figure 13CO2 transfer velocity (normalized to a Schmidt number of 660) vs. the friction velocity for both the southwest (open water) and northeast (Plymouth Sound) wind sectors. Note that colour-coding is capped at a chlorophyll a concentration of 2 mg m−3 for clarity.

The linear fit from Landwehr et al. (2018), derived from EC measurements of CO2 flux in the Southern Ocean, is also shown in Fig. 13. Compared to Landwehr et al. (2018), measurements at PPAO are similar at moderate u∗ values. At high u∗ values (strong winds), our estimates of increase with a greater power. Blomquist et al. (2017) demonstrated that waves play a role in the open-ocean air–sea exchange of CO2 at high wind speeds, and we expect waves to also influence u∗ (e.g. Edson et al., 2013). Waves shoal and steepen when they approach shallow water at the coast and generally break more frequently than in the open ocean. measured at PPAO when waves are large might not be the same as over the open ocean. Unfortunately there were no wave measurements within the flux footprints to quantitatively investigate this effect.

3.4.2 Seasonal variability in

We might expect the relationship between and wind speed to vary in different seasons due to the effects of bubbles and surfactants. Woolf et al. (1997) and Leighton et al. (2018) suggested an asymmetrical gas transfer rate that is faster for invasion than for evasion due to the hydrostatic pressure effect in bubble-mediated gas exchange, which is important for CO2 (Bell et al., 2017; Blomquist et al., 2017). Figure 12 is colour-coded by ΔpCO2 (positive when the ocean is supersaturated). We see that invasion (i.e. air to sea) of CO2, expected to occur in late spring and summer, was typically associated with low to moderate wind speeds. Evasion (i.e. sea to air) of CO2, expected to occur in late autumn and winter, was typically associated with moderate to high wind speeds. There was limited overlap between invasion and evasion cases in the same wind speed range, partly due to gaps in the pCO2 observations. Nevertheless, many of the data were well below the polynomial fit during periods of expected evasion and when U10n was between 6 and 10 m s−1.

Recent measurements show large spatial and temporal differences in surfactant activity over the Atlantic Ocean (Sabbaghzadeh et al., 2017). A higher surfactant activity has been associated with suppression in the gas transfer velocity (e.g. Salter et al., 2011; Pereira et al., 2016, 2018). Figure 13 is colour-coded by the near-surface chlorophyll a concentration (Chl a), an indicator of phytoplankton biomass and biological activity. Chl a was as low as 0.2 mg m−3 in the winter and early spring and as high as 5 mg m−3 during late spring and summer. Many of the data for the open-water sector were below the polynomial fit at times of high Chl a concentration. A seasonal variability in biologically influenced surfactant activity seems likely and could alter the and wind speed relationship. Higher-frequency observations of pCO2 within the flux footprint (e.g. from a buoy) would greatly increase the number of transfer velocity estimates and enable a more robust comparison between invasion and evasion. Approaches similar to Sabbaghzadeh et al. (2017) and Pereira et al. (2016) on a seasonal scale, coupled with EC gas flux measurements, would help to address the importance of naturally produced surfactants in gas exchange.

3.4.3 Dependence of on bottom-driven turbulence

Gas transfer driven by bottom-driven turbulence is parameterized as by Borges et al. (2004): 1.719 v0.5 h−0.5 (cm h−1), where v is the current velocity (in cm s−1), and h is water depth (in m). The authors treat this as a linearly additive term to wind-driven gas exchange. For a depth of 10 m for the Plymouth Sound and a current velocity on the order of 1 m s−1 during ebbing and flooding tides (Siddorn et al., 2003), this leads to a transfer velocity as a result of bottom-driven turbulence of ∼5 cm h−1 at a Schmidt number of 660. For the open-water sector, gas transfer driven by bottom-driven turbulence is calculated to be less than 4 cm h−1 due to the deeper water. For reference, the Nightingale et al. (2000) parameterization at a wind speed of 6–9 m s−1 is about 10–20 cm h−1. Thus, bottom-driven turbulence may have a relatively large (∼25 %) influence on our observations of at low to moderate wind speeds. Neglecting bottom-driven turbulence could have resulted in overestimates when calculating implied GHG concentrations (Sect. 3.1, 3.2), particularly at low wind speeds. Note though that our calculations of implied GHG concentrations were limited to wind speeds > 5 m s−1.

derived for the Plymouth Sound sector is also shown in Figs. 12 and 13. Given the strong diurnal variability in the implied pCO2 for this wind sector (see Fig. 8), we have further limited to the time of day of 10:00 to 16:00 UTC. This strict filtering as well as the small number of coincidental flux and pCO2 measurements results in only five 6 h estimates for the Plymouth Sound sector. Plymouth Sound values roughly increase with wind speed and friction velocity and are within the range of variability of the open-water values. Note that four out of five of these estimates were associated with wind speeds over 9 m s−1, for which bottom-driven turbulence is expected to have less influence (≤25 % of the wind-driven ). Future studies that combine EC flux measurements, frequent observations of seawater CO2 and CH4 concentrations within the footprint and in situ measurements of current velocity would allow us to better test and improve K parameterizations in shallow water.

3.5 Effects of rain on air–sea CO2 exchange

Our year-long EC flux observations provide a valuable opportunity to directly assess the importance of rain on gas exchange. Mechanistically, rain could affect air–sea CO2 flux in at least three ways. First, lab studies show that the falling raindrops increase the near-surface turbulence, increasing total K (e.g. Ho et al., 1997; Zappa et al., 2009). This effect is relatively more important at low wind speeds (e.g. Harrison et al., 2012). Secondly, rainwater could reduce near-surface pCO2 via changes in the carbonate chemistry and gas solubility (e.g. dilution effect; Turk et al., 2010) and so result in more negative (or less positive) CO2 fluxes. Lastly, dissolved CO2 in rain droplets is taken up by the sea, which is often termed the wet-deposition flux (e.g. Ashton et al., 2016). We examine each of these three mechanisms below.

Effect on K

Figure S12 shows the hourly and wind speed for the open-water sector, colour-coded by the measured precipitation rate at the surface (Ps). We use the hourly data here (filtered by a µatm threshold) because rainfall is highly episodic. It is not obvious from our data that rain enhances K at a given wind speed, which could be in part because typical rain rates at PPAO are roughly 1 order of magnitude lower than in lab studies or parts of the tropics where rain rates are often tens of millimetres per hour. A caveat here is that the pCO2 measurements were made approximately once a week from ∼3 m depth. Thus, they do not fully describe short-term changes in pCO2 at the air–sea interface as a result of rain. This could in turn influence the K estimate.

Dilution effect on near-surface pCO2

To tease out the effect of rain on CO2 flux via the dilution effect (and not on K), we focus on periods where we do not ordinarily expect to see much flux (i.e. when the expected is approximately zero). Figure S13 shows the hourly CO2 flux vs. rain rate for the open-water wind sector. Here we have only retained data where the expected is within 10 µatm. Within our limited dataset and given the measurement uncertainties, it is not obvious that rain makes the CO2 flux more negative (or less positive) via the dilution effect. For the open-water sector with µatm, the mean CO2 flux during rainy periods was −5.3 (SE of 5.1) mmol m−2 d−1. During non-rainy periods, the mean CO2 flux was −2.1 (SE of 2.1) mmol m−2 d−1. The two estimates are not statistically different from each other or from zero.

Wet-deposition flux

The wet-deposition flux of CO2 is estimated on an hourly basis as −sol. Here it is assumed that the falling rain droplets are in equilibrium with atmospheric CO2 (CO2,a). The mean wet-deposition flux over the entire year (including rainy and non-rainy periods) was computed to be about −0.1 mmol m−2 d−1, which is orders of magnitude smaller than the air–sea gas flux (e.g. Fig. 5). During rainy periods, the mean wet-deposition flux was −0.4 mmol m−2 d−1. Overall, the impact of rain on air–sea CO2 exchange is fairly limited at PPAO, largely as a result of the modest rain rate.

Air–sea CH4 and CO2 fluxes measured by eddy covariance from a coastal location in the southwest UK over 1 year demonstrate significant variability on seasonal timescales. CH4 flux in the coastal seas varied on a semi-diurnal (i.e. tidal) scale, while CO2 flux at times varied diurnally. These observations suggest that sporadic samplings of seawater concentrations that are limited to certain seasons, times of the day or tidal cycle could result in biased annual mean flux estimates (see Sect. 3.1 and 3.2). Surface ocean CH4 saturations implied from the measured fluxes exceed a few hundred percent, and were higher over the semi-enclosed Plymouth Sound than over open water. These results are consistent with the trend in dissolved CH4 concentration observed from the upper part of the river Tamar to the mouth of the Plymouth Sound. The coastal sea was a net sink of CO2 in late spring and summer and a net source of CO2 in autumn and winter. CO2 flux from the Plymouth Sound demonstrated greater diurnal variability than the CO2 flux from the open-water sector. We estimate the CO2 transfer velocity from our measurements of fluxes and in situ seawater concentrations. The mean derived CO2 transfer velocity at this coastal location agrees reasonably well with previous tracer-based and closed-path CO2 eddy covariance estimates from the open ocean. Rainfall does not appear to have a large direct effect on air–sea CO2 exchange at our temperate coastal site. There are hints of seasonality in the transfer velocity and wind speed relationship that may be related to asymmetric bubble-mediated gas exchange or biologically derived surfactants. The effect of bubbles, surfactants and bottom-driven turbulence warrants further investigation in order to improve our understanding of air–sea gas exchange and estimates of coastal greenhouse gas budgets.

Penlee Point Atmospheric Observatory (PPAO) data are archived at the Centre for Environmental Data Analysis (CEDA): http://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/uuid/8f1ff8ea77534e08b03983685990a9b0 (last access: 7 March 2019; Bell et al., 2017). Interested readers can contact the corresponding author directly for the full high-frequency (10 Hz) dataset.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-16-961-2019-supplement.

MY and TGB designed and performed the flux measurements and data analysis and interpretation. IJB and APR measured dissolved CH4 concentration, while VK measured seawater pCO2. JRF and TJS supplied the underway and buoy data from the Western Channel Observatory. TJS and PN provided helpful comments on the focus and context of the paper.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This work contributes to the ACSIS (The North Atlantic Climate System

Integrated Study; NE/N018044/1), MOYA (Methane Observations and Yearly

Assessments; NE/N015932/1), LOCATE (Land Ocean Carbon Transfer; NE/N018087/1)

and CLASS (Climate Linked Atlantic Sector Science) projects funded by the

Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), UK. The Western Channel

Observatory is funded by NERC's National Capability programme. Trinity House

(http://www.trinityhouse.co.uk/, last access: 7 March 2019) owns the

Penlee site and has kindly agreed to rent the building to PML so that

instrumentation can be protected from the elements. We are able to access

the site thanks to the cooperation of Mount Edgcumbe Estate

(http://www.mountedgcumbe.gov.uk/, last access: 7 March 2019). We thank

the Environmental Agency for the Tamar flow data. We also thank

Frances E. Hopkins (PML), Margaret J. Yelland (National Oceanography Centre),

Ian M. Brooks (University of Leeds) and John Prytherch (Stockholm University)

for continued measurement support. This is contribution number 5 from the

Penlee Point Atmospheric Observatory.

Edited

by: Gwenaël Abril

Reviewed by: two anonymous referees

Andersson, A. J. and Mackenzie, F. T.: Shallow-water oceans: a source or sink of atmospheric CO2?, Front. Ecol. Environ., 2, 348–353, 2004.

Artioli, Y., Blackford, J. C., Butenschoen, M., Holt, J., Wakelin, S. L., Thomas, H., Borges, A. V., and Allen, J. I.: The carbonate system in the North Sea: Sensitivity and model validation, J. Mar. Syst., 102–104, 1–13, 2012.

Ashton, I. G., Shutler, J. D., Land, P. E., Woolf, D. K., and Quartly, G. D.: A Sensitivity Analysis of the Impact of Rain on Regional and Global Sea-Air Fluxes of CO2, PLoS ONE, 11, e0161105, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161105, 2016.

Bange, H. W.: Nitrous oxide and methane in European coastal waters, Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci., 70, 361–374, 2006.

Bell, T. G., Landwehr, S., Miller, S. D., de Bruyn, W. J., Callaghan, A. H., Scanlon, B., Ward, B., Yang, M., and Saltzman, E. S.: Estimation of bubble-mediated air–sea gas exchange from concurrent DMS and CO2 transfer velocities at intermediate–high wind speeds, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 9019–9033, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-9019-2017, 2017.

Blomquist, B. W., Brumer, S. E., Fairall, C. W., Huebert, B. J., Zappa, C. J., Brooks, I. M., Yang, M., Bariteau, L., Prytherch, J., Hare, J. E., Czerski, H., Matei, A., and Pascal, R. W.: Wind Speed and Sea State Dependencies of Air-Sea Gas Transfer: Results From the High Wind Speed Gas Exchange Study (HiWinGS), J. Geophys. Res.-Ocean., 122, 1–29, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JC013181, 2017.

Borges, A. V., Schiettecatte, L.-S., Abril, G., Delille, B., and Gazeau, F.: Carbon dioxide in European coastal waters. Estuarine, Coast. Shelf Sci., 70, 375–387, 2006.

Borges, A. V., Darchambeau, F., Teodoru, C. R., Marwick, T. R., Tamooh, F., Geeraert, N., Omengo, F. O., Gueìrin, F., Lambert, T., Morana, C., Okuku, E., and Bouillon, S.: Globally significant greenhouse gas emissions from African inland waters, Nat. Geosci., 8, 637–642, https://doi.org/10.1038/NGEO2486, 2015.

Butterworth, B. J. and Else, B. G. T.: Dried, closed-path eddy covariance method for measuring carbon dioxide flux over sea ice, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 11, 6075–6090, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-11-6075-2018, 2018.

Butterworth, B. J. and Miller, S. D.: Air–sea exchange of carbon dioxide in the Southern Ocean and Antarctic marginal ice zone, Geophys. Res. Lett., 43, 7223–7230, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL069581, 2016.

Cai, W. J.: Estuarine and coastal ocean carbon paradox: CO2 sinks or sites of terrestrial carbon incineration?, Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci., 3, 123–145, 2011.

Cai, W. J., Dai, M. H., and Wang, Y. C.: Air-sea exchange of carbon dioxide in ocean margins: A province-based synthesis, Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, L12603, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL026219, 2006.

Chen, C. T. A. and Borges, A. V.: Reconciling opposing views on carbon cycling in the coastal ocean: Continental shelves as sinks and near-shore ecosystems as sources of atmospheric CO2, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 56, 578–590, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.01.001, 2009.

Chen, C.-T. A., Huang, T.-H., Chen, Y.-C., Bai, Y., He, X., and Kang, Y.: Air-sea exchanges of CO2 in the world's coastal seas, Biogeosciences, 10, 6509–6544, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-6509-2013, 2013.

Crosswell, J. R., Wetz, M. S., Hales, B., and Paerl, H. W.: Air-water CO2 fluxes in the microtidal Neuse River Estuary, North Carolina, J. Geophys. Res., 117, C08017, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012JC007925, 2012.

Csanady, G. T.: The role of breaking wavelets in air-sea gas transfer, J. Geophys. Res., 95, 749–759, https://doi.org/10.1029/JC095iC01p00749, 1990.

Dimitrov, L.: Contribution to atmospheric methane by natural seepages on the Bulgarian continental shelf, Cont. Shelf Res., 22, 2429–2442, 2002.

Edson, J., Hinton, A., Prada, K., Hare, J., and Fairall, C.: Direct covariance flux estimates from mobile platforms at sea, J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol., 15, 547–562, 1998.

Edson, J. B., Jampana, V., Weller, R. A., Bigorre, S. P., Plueddemann, A. J., Fairall, C. W., Miller, S. D., Mahrt, L., Vickers, D., and Hersbach, H.: On the exchange of momentum over the open ocean, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 43, 1589–1610, https://doi.org/10.1175/JPO-D-12-0173.1, 2013.

Esters, L., Breivik, O., Landwehr, S., ten Doeschate, A., Sutherland, G., Christensen, K. H., Bidlot, J., and Ward, B.: Turbulence scaling comparisons in the ocean surface boundary layer, J. Geophys. Res., 123, 2172–2191, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JC013525, 2018.

Frankignoulle, M. and Borges, A. V.: European continental shelf as a significant sink for atmospheric carbon dioxide, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 15, 569–576, 2001.

Frankignoulle, M., Abril, G., Borges, A., Bourge, I., Canon, C., Delille, B., Libert, E., and Theate, J.-M.: Carbon dioxide emission from European estuaries, Science, 282, 434–436, 1998.

Forster, G. L., Upstill-Goddard, R. C., Gist, N., Robinson, R., Uher, G., and Woodward, E. M. S.: Nitrous oxide and methane in the Atlantic Ocean between 501∘ N and 521∘ S: Latitudinal distribution and sea-to-air flux, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 56, 964–976, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.12.002, 2009.

Gutieìrrez-Loza, L. and Ocampo-Torres, F. J.: Air-sea CO2 fluxes measured by eddy covariance in a coastal station in Baja California, Mexico, in: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 35, 012012, IOP Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/35/1/012012, 2016.

Harrison, E. L., Vernon, F., Ho, D. T., Reid, M. R., Orton, P., and McGillis, W. R.: Nonlinear interaction between rain- and wind-induced air-water gas exchange, J. Geophys. Res., 117, C03034, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JC007693, 2012.

Hartmann, D. L., Klein Tank, A. M. G., Rusticucci, M., Alexander, L. V., Brönnimann, S., Charabi, Y., Dentener, F. J., Dlugokencky, E. J., Easterling, D. R., Kaplan, A., Soden, B. J., Thorne, P. W., Wild, M., and Zhai, P. M.: Observations: Atmosphere and Surface, in: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Stocker, T. F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S. K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., and Midgley, P. M., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2013.

Helmig, D., Rossabi, S., Hueber, J., Tans, P., Montzka, S. A., Masarie, K., Thoning, K., Plass-Duelmer, C., Claude, A., Car- penter, L. J., Lewis, A. C., Punjabi, S., Reimann, S., Vollmer, M. K., Steinbrecher, R., Hannigan, J. W., Emmons, L. K., Mahieu, E., Franco, B., Smale, D., and Pozzer, A.: Reversal of global atmospheric ethane and propane trends largely due to US oil and natural gas production, Nat. Geosci., 9, 490–495, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2721, 2016.

Ho, D. T., Bliven, L. F., Wanninkhof, R., and Schlosser, P.: The effect of rain on air?water gas exchange, Tellus B, 49, 149–158, https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0889.49.issue2.3.x, 1997.

Ho, D. T., Law, C. S., Smith, M. J., Schlosser, P., Harvey, M., and Hill, P.: Measurements of air-sea gas exchange at high wind speeds in the Southern Ocean: Implications for global parameterizations, Geophys. Res. Let., 33, L16611, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL026817, 2006.

Ho, D. T., Ferroìn, S., Engel, V. C., Larsen, L. G., and Barr, J. G.: Air-water gas exchange and CO2 flux in a mangrove-dominated estuary, Geophys. Res. Lett., 41, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013GL058785, 2014.

Honkanen, M., Tuovinen, J.-P., Laurila, T., Mäkelä, T., Hatakka, J., Kielosto, S., and Laakso, L.: Measuring turbulent CO2 fluxes with a closed-path gas analyzer in a marine environment, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 11, 5335–5350, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-11-5335-2018, 2018.

Houghton, R. A.: The Contemporary Carbon Cycle, in: Treatise on Geochemistry, edited by: Schlesinger, W. H., Holland, H. D., and Turekian, K. K., Elsevier, Vol. 8, 473–513, https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043751-6/08168-8, 2003.

Huebert, B., Blomquist, B., Yang, M., Archer, S., Nightingale, P., Yelland, M., Stephens, J., Pascal, R., and Moat, B.: Linearity of DMS transfer coefficient with both friction velocity and wind speed in the moderate wind speed range, Geophys. Res. Lett., 37, L01605, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GL041203, 2010.

Joesoef, A., Huang, W.-J., Gao, Y., and Cai, W.-J.: Air–water fluxes and sources of carbon dioxide in the Delaware Estuary: spatial and seasonal variability, Biogeosciences, 12, 6085-6101, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-12-6085-2015, 2015.

Khatiwala, S., Tanhua, T., Mikaloff Fletcher, S., Gerber, M., Doney, S. C., Graven, H. D., Gruber, N., McKinley, G. A., Murata, A., Ríos, A. F., and Sabine, C. L.: Global ocean storage of anthropogenic carbon, Biogeosciences, 10, 2169–2191, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-2169-2013, 2013.

Kitidis, V., Tizzard, L., Uher, G., Judd, A., Upstill-Goddard, R. C., Head, I. M., Gray, N. D., Taylor, G., Duran, R., Diez, R., Iglesias, J., and Garcia-Gil, S.: The biogeochemical cycling of methane in Ria de Vigo, NW Spain: Sediment processing and sea-air exchange, J. Mar. Syst., 66, 258–271, 2007.

Kitidis, V., Hardman-Mountford, N. J., Litt, E., Brown, I., Cummings, D., Hartman, S., Hydes, D., Fishwick, J. R., Harris, C., Martinez-Vicente, V., Malcolm, E., Woodward, S., and Smyth, T. J.: Seasonal dynamics of the carbonate system in the Western English Channel, Cont. Shelf Res., 42, 30–40, 2012.

Kljun, N., Calanca, P., Rotach, M. W., and Schmid, H. P.: A Simple Parameterisation for Flux Footprint Predictions, Bound.-Lay. Meteorol., 112, 503–523, 2004.

Landwehr, S., Miller, S. D., Smith, M. J., Bell, T. G., Saltzman, E. S., and Ward, B.: Using eddy covariance to measure the dependence of air–sea CO2 exchange rate on friction velocity, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 4297–4315, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-4297-2018, 2018.

Laruelle, G. G., Durr, H. H., Slomp, C. P., and Borges, A. V: Evaluation of sinks and sources of CO2 in the global coastal ocean using a spatially-explicit typology of estuaries and continental shelves, Geophys. Res. Lett., 37, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010gl043691, 2010.

Leighton, T., Coles, D. G. H., Srokosz, M., White, P. R., and Woolf, D. K.: Asymmetric transfer of CO2 across a broken sea surface, Nat. Sci. Rep., 8, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25818-6, 2018.

Le Quéré, C., Andrew, R. M., Friedlingstein, P., Sitch, S., Hauck, J., Pongratz, J., Pickers, P. A., Korsbakken, J. I., Peters, G. P., Canadell, J. G., Arneth, A., Arora, V. K., Barbero, L., Bastos, A., Bopp, L., Chevallier, F., Chini, L. P., Ciais, P., Doney, S. C., Gkritzalis, T., Goll, D. S., Harris, I., Haverd, V., Hoffman, F. M., Hoppema, M., Houghton, R. A., Hurtt, G., Ilyina, T., Jain, A. K., Johannessen, T., Jones, C. D., Kato, E., Keeling, R. F., Goldewijk, K. K., Landschützer, P., Lefèvre, N., Lienert, S., Liu, Z., Lombardozzi, D., Metzl, N., Munro, D. R., Nabel, J. E. M. S., Nakaoka, S.-I., Neill, C., Olsen, A., Ono, T., Patra, P., Peregon, A., Peters, W., Peylin, P., Pfeil, B., Pierrot, D., Poulter, B., Rehder, G., Resplandy, L., Robertson, E., Rocher, M., Rödenbeck, C., Schuster, U., Schwinger, J., Séférian, R., Skjelvan, I., Steinhoff, T., Sutton, A., Tans, P. P., Tian, H., Tilbrook, B., Tubiello, F. N., van der Laan-Luijkx, I. T., van der Werf, G. R., Viovy, N., Walker, A. P., Wiltshire, A. J., Wright, R., Zaehle, S., and Zheng, B.: Global Carbon Budget 2018, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 10, 2141–2194, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-10-2141-2018, 2018.

Litt, E. J., Hardman-Mountford, N. J., Blackford, J. C., Mitchelson-Jacob, G., Goodman, A., Moore, G. F., Cummings, D. G., and Butenschon, M.: Biological control of pCO2 at station L4 in the Western English Channel over 3 years, J. Plankton Res., 32, 621–629, 2010.

Marrec, P., Cariou, T., Latimier, M., Macé, E., Morin, P., Vernet, M., and Bozec, Y.: Spatio-temporal dynamics of biogeochemical processes and air–sea CO2 fluxes in the Western English Channel based on two years of FerryBox deployment, J. Mar. Syst., 40, 26–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmarsys.2014.05.010, 2014.

Middelburg, J. J., Nieuwenhuize, J., Iversen, N., Høgh, N., De Wilde, H., Helder, W., Seifert, R., and Christof, O.: Methane distribution in European tidal estuaries, Biogeochemistry, 59, 95e119, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015515130419, 2002.

Muller-Karger, F. E., Varela, R. Thunell, R. Luerssen, R., Hu, C., and Walsh J. J.: The importance of continental margins in the global carbon cycle, Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, L01602, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004GL021346, 2005.

Nightingale, P. D., Malin, G., Law, C. S., Watson, A. J., Liss, P. S., Liddicoat, M. I., Boutin, J., and Upstill-Goddard, R. C.: In situ evaluation of air–sea gas exchange parameterizations using novel conservative and volatile tracers, Glob Biogeochem. Cy., 14, 373–387, 2000.

Nisbet, E. G., Dlugokencky, E. J., Manning, M. R., Lowry, D., Fisher, R. E., France, J. L., Michel, S. E., Miller, J. B., White, J. W. C., Vaughn, B., Bousquet, P., Pyle, J. A., Warwick, N. J., Cain, M., Brownlow, R., Zazzeri, G., Lanoiselleì, M., Manning, A. C., Gloor, E., Worthy, D. E. J., Brunke, E.-G., Labuschagne, C., Wolff, E. W., and Ganesan, A. L.: Rising atmospheric methane: 2007–2014 growth and isotopic shift, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 30, 1356–1370, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GB005406, 2016.

O'Connor, D. J. and Dobbins, W. E.: Mechanism of reaeration in natural streams, Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng., 123, 641–684, 1958.

Pereira, R., Schneider-Zapp, K., and Upstill-Goddard, R. C.: Surfactant control of gas transfer velocity along an offshore coastal transect: results from a laboratory gas exchange tank, Biogeosciences, 13, 3981–3989, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-13-3981-2016, 2016.

Pereira, R., Ashton, I., Sabbaghzadeh, B., Shutler, J. D., and Upstill-Goddard, R. C.: Reduced air–sea CO2 exchange in the Atlantic Ocean due to biological surfactants, Nat. Geosci., 11, 492–496, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0136-2, 2018.

Pison, I., Ringeval, B., Bousquet, P., Prigent, C., and Papa, F.: Stable atmospheric methane in the 2000s: key-role of emissions from natural wetlands, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 11609–11623, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-11609-2013, 2013.

Rigby, M., Montzka, S. A., Prinn, R. G., White, J. W. C., Young, D., O'Doherty, S., Lunt, M. F., Ganesan, A. L., Manning, A. J., Simmonds, P. G., Salameh, P. K., Harth, C. M., Mühle, J., Weiss, R. F., Fraser, P. J., Steele, L. P., Krummel, P. B., Mc- Culloch, A., and Park, S.: Role of atmospheric oxidation in recent methane growth, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 114, 5373–5377, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1616426114, 2017.

Rice, A. L., Butenhoff, C. L., Teama, D. G., Röger, F. H., Khalil, M. A. K., and Rasmussen, R. A.: Atmospheric methane isotopic record favors fossil sources flat in 1980s and 1990s with recent increase, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 10791–10796, 2016.

Rutgersson, A., Norman, M., Schneider, B., Pettersson, H., and Sahleìe, E.: The annual cycle of carbon dioxide and parameters influencing the air–sea carbon exchange in the Baltic Proper, J. Mar. Syst., 74, 381–394, 2008.

Sabbaghzadeh, B., Upstill-Goddard, R. C., Beale, R., Pereira, R., and Nightingale, P. D.: The Atlantic Ocean surface microlayer from 50∘ N to 50∘ S is ubiquitously enriched in surfactants at wind speeds up to 13 m s−1, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, 2852–2858, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL072988, 2017.

Salter, M. E., Upstill-Goddard, R. C., Nightingale, P. D., Archer, S. D., Blomquist, B., Ho, D. T., Huebert, B., Schlosser, P., and Yang, M.: Impact of an artificial surfactant release on air-sea gas fluxes during Deep Ocean Gas Exchange Experiment II, J. Geophys. Res.-Ocean., 116, C11016, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JC007023, 2011.