the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Novel hydrocarbon-utilizing soil mycobacteria synthesize unique mycocerosic acids at a Sicilian everlasting fire

Nadine T. Smit

Laura Villanueva

Darci Rush

Fausto Grassa

Caitlyn R. Witkowski

Mira Holzheimer

Adriaan J. Minnaard

Jaap S. Sinninghe Damsté

Stefan Schouten

Soil bacteria rank among the most diverse groups of organisms on Earth and actively impact global processes of carbon cycling, especially in the emission of greenhouse gases like methane, CO2 and higher gaseous hydrocarbons. An abundant group of soil bacteria are the mycobacteria, which colonize various terrestrial, marine and anthropogenic environments due to their impermeable cell envelope that contains remarkable lipids. These bacteria have been found to be highly abundant at petroleum and gas seep areas, where they might utilize the released hydrocarbons. However, the function and the lipid biomarker inventory of these soil mycobacteria are poorly studied. Here, soils from the Fuoco di Censo seep, an everlasting fire (gas seep) in Sicily, Italy, were investigated for the presence of mycobacteria via 16S rRNA gene sequencing and fatty acid profiling. The soils contained high relative abundances (up to 34 % of reads assigned) of mycobacteria, phylogenetically close to the Mycobacterium simiae complex and more distant from the well-studied M. tuberculosis and hydrocarbon-utilizing M. paraffinicum. The soils showed decreasing abundances of mycocerosic acids (MAs), fatty acids unique for mycobacteria, with increasing distance from the seep. The major MAs at this seep were tentatively identified as 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl tetracosanoic acid and 2,4,6,8,10-pentamethyl hexacosanoic acid. Unusual MAs with mid-chain methyl branches at positions C-12 and C-16 (i.e., 2,12-dimethyl eicosanoic acid and 2,4,6,8,16-pentamethyl tetracosanoic acid) were also present. The molecular structures of the Fuoco di Censo MAs are different from those of the well-studied mycobacteria like M. tuberculosis or M. bovis and have relatively δ13C-depleted values (−38 ‰ to −48 ‰), suggesting a direct or indirect utilization of the released seep gases like methane or ethane. The structurally unique MAs in combination with their depleted δ13C values identified at the Fuoco di Censo seep offer a new tool to study the role of soil mycobacteria as hydrocarbon gas consumers in the carbon cycle.

- Article

(2999 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Soils harbor the largest diversity of microorganisms on our planet and have a large influence on the Earth's ecosystem as they actively impact nutrient and carbon cycling, plant production and the emissions of greenhouse gases (Tiedje et al., 1999; Bardgett and van der Putten, 2014; Delgado-Baquerizo et al., 2018). Soil bacteria rank among the most diverse and abundant groups of organisms on Earth. However, numerous studies suggest that most of their function and diversity in our ecosystems are still undescribed (Tiedje et al., 1999; Bardgett and van der Putten, 2014). The assessment of soil bacterial diversity has mainly relied on 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing and has indicated that the most abundant bacterial phylotypes in global soils include Alphaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Acidobacteria and Planctomycetes (Fierer et al., 2012; Delgado-Baquerizo et al., 2018). Besides the use of DNA-based techniques, lipid biomarkers offer an additional tool to investigate soil bacterial communities, such as branched glycerol dialky glycerol tetraether (brGDGTs) believed to derive from soil acidobacteria (Weijers et al., 2009; Peterse et al., 2010; Sinninghe Damsté et al., 2018) or lipids derived from methanotrophic bacteria like certain fatty acids (Bull et al., 2000; Bodelier et al., 2009), specific bacteriohopanepolyols (van Winden et al., 2012; Talbot et al., 2016) or 13C-depleted hopanoids (Inglis et al., 2019; van Winden et al., 2020).

Mycobacteria of the genus Mycobacterium belonging to the phylum Actinobacteria form an abundant microbial group in global soils (Falkinham, 2015; Walsh et al., 2019). Some members of the genus Mycobacterium are obligate pathogens (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae) and are the cause of more than 1.5 million annual human deaths worldwide through the diseases tuberculosis and leprosy (World Health Organization, 2019). Thus, they have consequently been more frequently studied than opportunistic pathogenic and non-pathogenic environmental mycobacteria. Interestingly, early studies from the 1950s reported high abundances of non-pathogenic hydrocarbon-consuming mycobacteria (M. paraffinicum) in areas of oil and gas production, gas seeps and common garden soils (Davis et al., 1956; Dworkin and Foster, 1958; Davis et al., 1959). Cultivation and genomic studies show that mycobacteria can oxidize a range of greenhouse gases (ethane, propane, alkenes, carbon monoxide or hydrogen) and can degrade toxic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (Miller et al., 2007; Hennessee et al., 2009; Coleman et al., 2012; Martin et al., 2014). Mycobacteria are able to colonize a wide variety of habitats from soils to aquatic and human-engineered environments (Brennan and Nikaido, 1995; Falkinham, 2009). Their impermeable cell envelope may play an important role in their ecological dominance. It consists of a peptidoglycan polymer that is surrounded by a thick hydrophobic lipid-rich outer membrane. This impermeability favors the formation of biofilms, thus enabling mycobacteria to often be the first colonizers at environmental interfaces like air–water or surface–water (Brennan and Nikaido, 1995). Additionally, the impermeable cell membrane allows a resistance to acidic conditions, anoxic survival and the possibility to metabolize recalcitrant carbon compounds. Mycobacteria feature an unusual lipid inventory such as extremely long fatty acids with chains up to 90 carbon atoms long and with numerous methyl groups, hydroxylations and/or methoxylations produced by two fatty acid biosynthesis systems, i.e., FAS type I (eukaryotic type) and FAS type II (prokaryotic type) (Minnikin et al., 1985, 1993a; Donoghue et al., 2017; Daffé et al., 2019). Furthermore, mycobacteria are known to synthesize characteristic fatty acids like tuberculostearic acid (10-Me C18:0) and the multi-methyl-branched mycocerosic acids (MAs) that can contain three to five methyl branches at regularly spaced intervals such as at positions C-2, C-4, C-6 and C-8 (Minnikin et al., 1985, 1993a, 2002; Redman et al., 2009). MAs are synthesized by the mycocerosic acid synthase (encoded by the mas gene) through the FAS-type pathway I using a methyl malonyl CoA instead of a malonyl CoA, generating the unique methyl branching pattern of MAs (Brennan, 2003; Gago et al., 2011). These unusual fatty acids are bound to complex glycolipids like phthiocerol dimycocerosates (PDIMs), diacyl trehalose (DATs) or phenolic glycolipids (Minnikin et al., 2002; Jackson et al., 2007). However, in contrast to the pathogenic and opportunistic pathogenic mycobacteria, the lipid biomarker inventory of non-pathogenic mycobacteria in soils and other environments remains poorly described.

In this study, we investigated soils near a continuous gas seep named “Fuoco di Censo” (“everlasting fire”) in Sicily, Italy, to explore the presence of non-pathogenic, potentially hydrocarbon-utilizing, mycobacterial species using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and fatty acid profiling. It resulted in the identification of potential biomarkers for the presence of mycobacteria in terrestrial environments and hydrocarbon seeps. Furthermore, their stable carbon isotopic composition provided hints at their role in the carbon cycle in this gas seepage environment.

2.1 Study area

The Fuoco di Censo seep (37∘37′30.1′′ N, 13∘23′15.0′′ E), in the following referred to as the Censo seep, is located at 800 m above sea level in the mountains of southwestern Sicily, Italy (Etiope et al., 2002; Grassa et al., 2004). The area is part of the Alpine orogenic belt in the Mediterranean and located along the boundary of the African and European plates (Basilone, 2012). The Censo seep belongs to the Bivona area, which is characterized by a complex geological setting. The seep is located in an area with sandy clays, marls and evaporites from the Tortonian–Messinian that are covered by a thrusting limestone of Carnian–Rhetian age (Trincianti et al., 2015). The Censo seep is a typical example of a natural everlasting fire, which is characterized by the absence of water and the temporal production of flames, which can be several meters high, by a continuous gas flux (Etiope et al., 2002). The Censo seep gas consists mainly of CH4 (76 %–86 %) and N2 (10 %–17 %) as well as some other minor gases like CO2, O2, ethane, propane, He and H2 (Etiope et al., 2002; Grassa et al., 2004). A diffuse soil degassing is detectable within an area of 80 m2 with an average CH4 flux of 7×106 mg m−2 d−1 and a total CH4 emission of 6.2×103 kg yr−1 (Etiope et al., 2002, 2007). The CH4 is suggested to be generated by the thermal alteration of organic matter and is characterized by a stable carbon isotopic composition of ‰ and ‰ (Grassa et al., 2004). This thermogenic CH4 possibly derives from mature marine source rocks (kerogen type II) with a thermal maturity beyond the oil window, resulting in a dry gas with ratios greater than 100 (Grassa et al., 2004).

2.2 Sample collection

Soil samples of the Censo seep were recovered during a field campaign in October 2017. The soil was collected from a horizon 5 to 10 cm below the surface and at three distances from the seep, i.e., 0 m (seep site), 1.8 m and a control at 13.2 m from the main vent. The in situ temperature of the soils at the time of collection was ca. 18 ∘C. The soils were directly transferred into a clean geochemical sampling bag and stored frozen at −20 ∘C until freeze-drying and extraction.

2.3 Extraction and saponification

Freeze-dried Censo soils were extracted with a modified Bligh and Dyer extraction for various compound classes (Schouten et al., 2008; Bale et al., 2013). Soil samples (ca. 12 g) were ultrasonically extracted (10 min) with a solvent mixture containing methanol (MeOH), dichloromethane (DCM) and phosphate buffer (, ). After centrifugation, the solvent was collected and combined and the residues re-extracted twice. A biphasic separation was achieved by adding additional DCM and phosphate buffer to a ratio of MeOH, DCM and phosphate buffer (, ). The aqueous layer was washed two more times with DCM and the combined organic layers dried over a Na2SO4 column followed by drying under N2.

Saponification (base hydrolysis) was conducted on aliquots (1–7 mg) of the Bligh–Dyer extracts (BDEs) to release fatty acids from structurally complex intact polar lipids by the addition of 2 mL 1N KOH in MeOH solution and refluxing for 1 h at 130 ∘C. After cooling, the pH was adjusted to 5 by using a 2N HCL in MeOH solution, separated with 2 mL bidistilled water and 2 mL DCM, and the organic bottom layer was collected. The aqueous layer was washed two more times with DCM and the combined organic layers dried over a Na2SO4 column followed by drying under N2.

2.4 Derivatization of fatty acids

2.4.1 Preparation of fatty acid methyl esters using BF3

Aliquots of the saponified Censo seep BDEs and aliquots of a mycocerosic acid standard (2,4,6-trimethyl-tetracosanoic acid; C27 MA standard) synthesized by hydrogenation with palladium and charcoal from mycolipenic acid (Holzheimer et al., 2020) were esterified with 0.5 mL of a boron trifluoride–methanol solution (BF3 solution) for 10 min at 60 ∘C. After cooling, 0.5 mL bidistilled water and 0.5 mL DCM were added and shaken, and the DCM bottom layer was pipetted off. The water layer was extracted twice with DCM, and the combined DCM layers were dried over an MgSO4 column. The soil extracts were eluted over a small silica gel column with ethyl acetate as an eluent to remove polar compounds. Extracts were subsequently separated using a small column packed with activated aluminum oxide into two fractions. The first fraction (fatty acid methyl ester fraction) was eluted with four column volumes of DCM followed by a second fraction (polar fraction) eluted with three column volumes of (1:1). The fatty acid methyl ester fractions were dried under a continuous flow of N2 and analyzed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) and GC–isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS).

2.4.2 Preparation of fatty acid “picolinyl” esters derivatives using 3-pyridylcarbinol

Aliquots of saponified Censo seep BDEs, as well as aliquots of the C27 MA, standard, were derivatized into picolinyl esters. This technique enhances the abundance of diagnostic fragment ions in the mass spectrum, such as those of methyl branching points in fatty acids, enabling an improved structural identification (Christie, 1998; Harvey, 1998). Different picolinyl derivatization protocols were tested on the C27 MA standard and the highest yields were achieved by the procedure in Harvey (1998). In this procedure, 0.5 mL of thionyl chloride was added using a 1 mL disposable syringe to 1 mg aliquot of the dried saponified Censo seep BDEs in a pressure vial and left for ca. 2 min at room temperature. The vials were then dried by a continuous flow of N2. A total of 0.5 mL of a solution of 1 % 3-pyridylcarbinol in acetonitrile was added in the reaction vials and left at room temperature for 2 min. The volumes of reagents in this protocol were reduced (0.1 mL) for 0.1 mg of the MA standard. The picolinyl esters were transferred with acetonitrile to 2 mL analysis vials and the concentration was adjusted to 1 mg mL−1 with acetonitrile. The picolinyl esters were analyzed using GC–MS with acetonitrile as injection solvent.

2.4.3 Preparation of fatty acid methyl sulfide esters using dimethyl disulfide (DMDS)

To determine the position of the double bonds in unsaturated fatty acids, dimethyl disulfide (DMDS) derivatization was used (Francis, 1981; Nichols et al., 1986). For this, 100 µL of hexane, 100 µL of DMDS solution (Merck ≥99 %) and 20 µL of I2/ether were added to the dry aliquot and heated overnight at 40 ∘C. The mixture was left to room temperature and 400 µL of hexane and 200 µL of a 5 % aqueous solution of Na2S2O3 (for iodine deactivation) were added and mixed. The upper hexane layer was removed, and the aqueous layer washed twice with hexane. The three hexane layers were combined and dried over a Na2SO4 column before GC–MS analysis with hexane as injection solvent.

2.5 Instrumental analysis

2.5.1 Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS)

GC–MS was performed using an Agilent Technologies GC–MS Triple Quad 7000C in full-scan mode. A CP-Sil5 CB column (25 m×0.32 mm with a film of 0.12 µm, Agilent Technologies) was used for the chromatography with He as the carrier gas (constant flow 2 mL min−1). The samples (1 µL) were injected on column at 70 ∘C, the temperature was increased at 20 ∘C min−1 to 130 ∘C and raised further by 4 ∘C min−1 to 320 ∘C, at which it was held for 20 min. The mass spectrometer was operated over a mass range of 50 to 850; the gain was set at 3, with a scan time of 700 ms.

2.5.2 Gas chromatography–isotope ratio mass spectrometry (GC–IRMS)

GC–IRMS was carried out with a Thermo Scientific Trace 1310 with a GC Isolink II, a ConFlo IV and a Delta Advantage IRMS. The gas chromatography was performed on a CP-Sil5 CB column (25 m×0.32 mm with a film thickness of 0.12 µm, Agilent) with He as the carrier gas (constant flow 2 mL min−1). The BF3 methylated samples (dissolved in ethyl acetate) were on-column injected at 70 ∘C, and subsequently, the oven was programmed to 130 ∘C at 20 ∘C min−1, and then at 4 ∘C min−1 to 320 ∘C, which was held for 10 min. Stable carbon isotope ratios are reported in delta notation against Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) 13C standard. Values were determined by two analyses and results averaged to a mean value.

2.6 DNA extraction, 16S rRNA gene amplification, analysis and phylogeny

DNA was extracted from sediments using the PowerMax soil DNA isolation kit (Qiagen). DNA extracts were stored at −80 ∘C until further analysis. The 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and analysis were performed with the general 16S rRNA archaeal and bacterial primer pair 515F and 806RB targeting the V4 region (Caporaso et al., 2012; Besseling et al., 2018). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were gel purified using the QIAquick Gel-Purification kit (Qiagen), pooled and diluted. Sequencing was performed at the Utrecht Sequencing Facility (Utrecht, the Netherlands) using an Illumina MiSeq sequencing platform. The 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequences were analyzed by an in-house pipeline (Abdala Asbun et al., 2020) that includes quality assessment by FastQC (Andrews, 2010), assembly of the paired-end reads with Pear (Zhang et al., 2013) and assignment of taxonomy (including picking a representative set of sequences with the “longest” method) with blast by using the ARB Silva database (https://www.arb-silva.de/, last access: 5 August 2018, release 128). Representative operational taxonomic unit (OTU) sequences (assigned with OTU picking the method based on 97 % nucleotide similarity with Uclust) (Edgar, 2010), attributed to the family Mycobacteriaceae, were aligned by using Muscle (Edgar, 2004) implemented in MEGA6 and then used to construct a phylogeny together with 16S rRNA gene sequences of characterized Mycobacterium species and closely related uncultured Mycobacteriaceae 16S rRNA gene sequences. The phylogenetic tree was inferred using the maximum likelihood method based on the general time reversible model (Nei and Kumar, 2000). The analysis involved 32 nucleotide sequences with 294 base pair positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6 (Tamura et al., 2013).

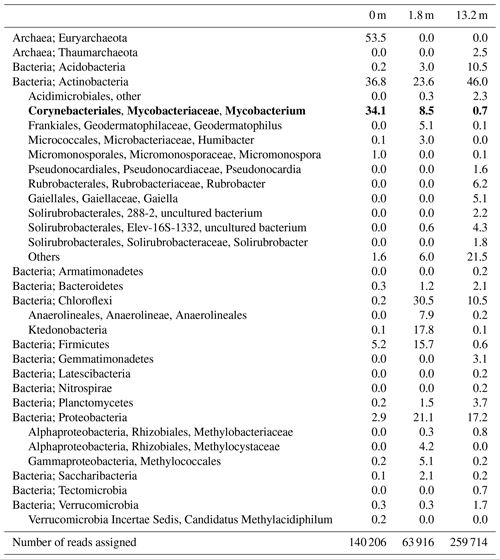

3.1 Microbial diversity in the Censo seep soils

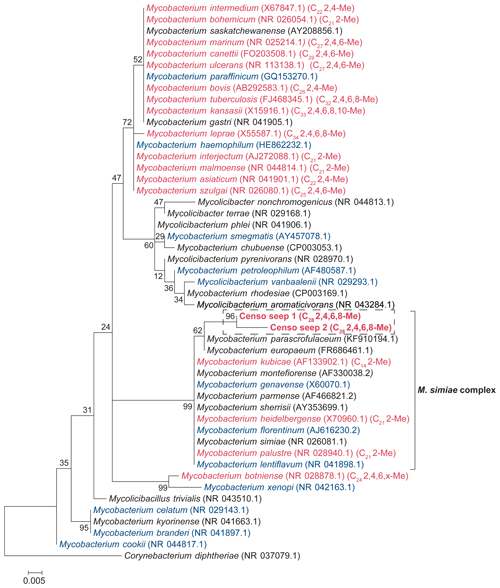

Soils were sampled at the Censo seep and with increasing distance from the seep (Table 1). To investigate the microbial diversity, 16S rRNA gene libraries were generated from extracted DNA using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. This analysis showed a high relative abundance of 16S rRNA gene reads attributed to Mycobacteriaceae ranging from 0.7 % to 34.1 % of assigned bacterial plus archaeal reads in the soils with relative abundances increasing with decreasing distance from the seep (Table 1). Sequences assigned to known methanotrophs are Gammaproteobacteria (Methylococcales), Alphaproteobacteria (Methylocystaceae and Methylobacteriaceae) and Verrucomicrobia (“Candidatus Methylacidiphilum”) but only accounted for 0.2 % to 5.1 % of the total number of reads assigned (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that there are two sequences representative for operational taxonomic units (OTUs) attributed to mycobacteria (i.e., sequences Censo seep 1 and Censo seep 2) present in the soils (Fig. 1). Both OTUs are phylogenetically most closely related to sequences of the Mycobacterium simiae complex (Tortoli, 2014) (Fig. 2; >98 % identical considering the 294 bp sequence fragment analyzed), which include M. simiae, M. europaeum, M. kubicae and M. heidelbergense (Hamieh et al., 2018). Previously described cultivated mycobacteria of the M. simiae complex are slow-growing mycobacterium species isolated from environmental niches but also associated with infections in humans as opportunistic pathogens (Lévy-Frébault et al., 1987; Heap, 1989; Bouam et al., 2018). The Censo seep sequences are more distantly related (94 %–95 % identical) to frequently studied pathogenic mycobacteria (such as M. tuberculosis and M. leprae) and other environmental mycobacteria like hydrocarbon utilizers (e.g., M. paraffinicum and M. vanbaalenii) (Fig. 1). To the best of our knowledge the hydrocarbon-utilizing bacteria have not been isolated from humans or animals (e.g., M. vanbaalenii) and are mostly able to degrade aromatic hydrocarbons (Kweon et al., 2015). Our data reveal abundances of up to 34 % of uncultured mycobacteria (Censo 0 m) in the soils around the Censo seep. This is in line with previous reports of the occurrence of mycobacteria near petroleum seeps and gas fields (Davis et al., 1956, 1959).

Table 1Distribution of the main microbial groups (in percentage of assigned reads) based on 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing at three distances from the main gas seep in the Censo soils. The bold typeface annotates the relative abundances of mycobacteria in the Censo soils.

Figure 1Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree of the Mycobacterial 16S rRNA gene fragments (i.e., 294 bp; in bold) generated by amplicon sequencing and representative for the two OTUs present in the soils from the Censo seep everlasting fire. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of Corynebacterium diphtheriae was used as an outgroup, and other Mycobacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences are plotted for reference. The ML tree is based on the general time reversible model with gamma distribution plus invariable sites. Mycobacterial species biosynthesizing MAs are indicated in red font, species not containing MAs are shown in blue and species for which MAs have not been analyzed are shown in black. The mycobacterial species producing MAs (in red) are labeled with their dominant MA in brackets (total carbon number, Me: methyl, x: unidentified position of methyl group).

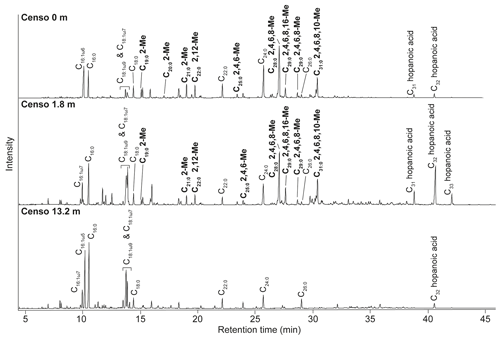

Figure 2Total ion chromatograms of the saponified and derivatized (BF3) fatty acid fractions from the Censo seep soils at an increasing distance from the main seepage showing the distributions of FAs, hopanoic acids and MAs. The black bold annotations show the tentatively identified MAs and the carbon position of their methyl groups (Me).

3.2 Fatty acid composition of Censo seep soils

Analysis of the fatty acid fractions of the Censo seep soils reveals a distinct pattern that changes with increasing distance from the main seep (Fig. 2). Common fatty acids such as C16:0, C16:1ω6, C16:1ω7, C18, C18:1ω9 and C18:1ω7 as well as the longer-chain C22 and C24 fatty acids occur in all three soils. C16 and C18 fatty acids are abundant lipids in soils and are synthesized by diverse bacteria and fungi, whereas the longer-chain (C22–C24) fatty acids originate commonly from higher plants (Řezanka and Sigler, 2009; Frostegård et al., 2011). These fatty acids could also derive from mycobacteria which can produce fatty acids (C14 to C26) with high amounts of C16 and C18 fatty acids and their unsaturated homologues (Chou et al., 1996; Torkko et al., 2003). Besides mycobacteria which are abundant in the soils close to the main seepage (Table 1), the C16 fatty acids may also originate from Type I methanotrophs (Gammaproteobacteria), whereas C18 fatty acids could derive from type II methanotrophs (Alphaproteobacteria), present in these Censo seep soils (Fig. 2 and Table 1) (Bull et al., 2000; Bowman et al., 1993; Bodelier et al., 2009). However, the relative abundances of 16S rRNA gene reads of these Type I and II methanotrophs are only minor in the Censo soils (Table 1).

The Censo seep soils also feature C31–C33 17β,21β(H)-homohopanoic acids, the most abundant of which is the C32 17β,21β(H)-hopanoic acid (bishomohopanoic acid) (Fig. 2). Hopanoic acids are common components in terrestrial environments (Ourisson et al., 1979; Rohmer et al., 1984; Ries-Kautt and Albrecht, 1989; Crossman et al., 2005; Inglis et al., 2018) and can be derived from a range of bacteria, including Alpha- and Gammaproteobacteria, Planctomycetes, and Acidobacteria (Thiel et al., 2003; Sinninghe Damsté et al., 2004; Birgel and Peckmann, 2008; Sinninghe Damsté et al., 2017). Explorative searches of genomic databases for the biosynthetic gene encoding squalene-hopane-cyclase (shc) in mycobacteria from the M. simiae complex revealed a potential for biohopanoid production. In contrast, the more distantly related pathogenic mycobacteria, e.g., M. tuberculosis, are known to synthesize steroids instead of hopanoids (Lamb et al., 1998; Podust et al., 2001). Therefore, mycobacteria from the M. simiae complex may be an additional source for hopanoic acids in the Censo seep soils.

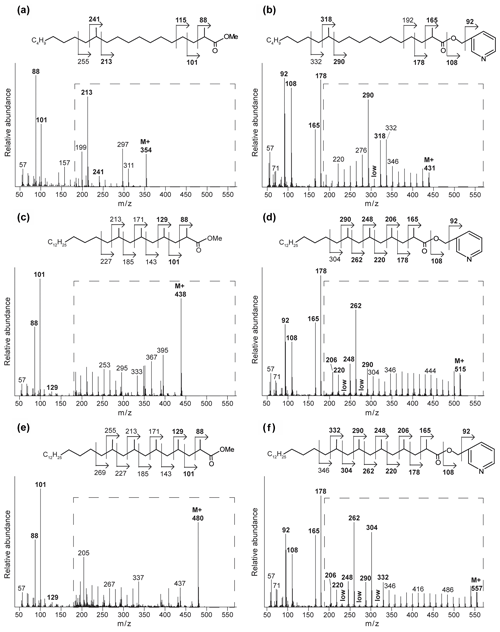

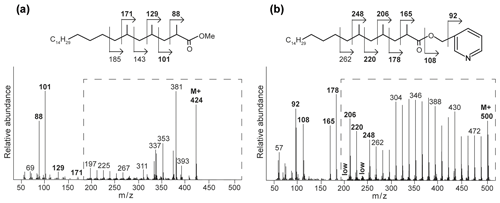

Interestingly, at the seep (0 m) the FA pattern is dominated by unusual FAs ranging from C19 to C31, which are absent further away from the main seepage (Fig. 2). The mass spectra of the three most abundant representatives of these fatty acids are shown in Fig. 3. Mass spectra of the methyl ester derivatives of these fatty acids show major fragment ions of 88 and 101. These fragments result from “McLafferty” rearrangements associated with the presence of the carboxylic acid methyl ester group (Lough, 1975; Ran-Ressler et al., 2012). The presence of the even-numbered 88 fragment ion, rather than the typical fragment ion at 74 in the mass spectra of methyl esters of n-FAs, strongly suggests a methyl group at position C-2 (Fig. 3). One FA also shows high fragment ions at 213 and 241 (Fig. 3a). This difference of 28 Da hints at a second methyl group at position C-12 (Fig. 3a). Two of these fatty acids show a fragment ion at 129 (Fig. 3c and e), suggesting the presence of an additional methyl at position C-4 of the fatty acids. The apparent methyl branches in these fatty acids are in agreement with the relatively early retention times of these FAs compared to the regular straight-chain counterparts (Fig. 2). Other fragment ions, including those potentially revealing the positions of additional methyl groups, were only present in low abundance, complicating further structural identification. Nevertheless, the presence of methyl branches at C-2 and C-4 in a number of these fatty acids does suggest that they may be related to mycobacteria-derived MAs, which share the same structural characteristics (Alugupalli et al., 1998; Nicoara et al., 2013). Indeed, the mass spectrum of the methyl ester of a synthetic C27 MA standard (2,4,6-trimethyl-tetracosanoic acid) (Holzheimer et al., 2020) shows identical mass spectral features (i.e., 88 and 129; Fig. 4a). However, full structural interpretation of the mass spectrum of this authentic standard is also complicated by the low abundances of diagnostic fragment ions indicative for the position of the methyl branches in the alkyl chain.

Figure 3Mass spectra of the methyl-ester-derivatized (a, c, e) and picolinyl-ester-derivatized (b, d, f) MAs of the Censo 0 m soil sample, with proposed molecular structures and fragmentation patterns. 2,12-Dimethyl-eicosanoic acid (C22 2,12-Me MA) (a, b), 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl-tetracosanoic acid (C28 2,4,6,8-Me MA) (c, d), and 2,4,6,8,10-pentamethyl-hexacosanoic acid (C31 2,4,6,8,10-Me MA) (e, f). The dashed boxes show a 10 times exaggerated view into the indicated area of the mass spectrum.

Figure 4Mass spectra with fragmentation and annotated molecular structures of the (a) methyl ester and (b) picolinyl ester synthetic 2,4,6-trimethyl-tetracosanoic acid (C27 2,4,6-Me MA standard). The dashed boxes show a 10 times exaggerated view into the indicated area of the mass spectrum.

To enhance the diagnostic fragmentation patterns of these potential MAs, the fatty acids were also transformed into a picolinyl ester (Harvey, 1998). The potential of this technique is revealed by the mass spectrum of the synthetic MA standard (2,4,6-trimethyl-tetracosanoic acid) picolinyl ester derivative (Fig. 4b), which shows fragment ions revealing all positions of methylation of the fatty acid n-alkyl chain. The high intensity of the fragment ion of 165 indicate the presence of a methyl group at position C-2, while the presence of the fragment ions at 178 and 206 combined with the absence of an 192 fragment ion indicates the presence of a methyl group at C-4. Similarly, the presence of the third methyl group at position C-6 is revealed by the fragment ions at 220 and 248 and the low abundance of the fragment ion at 234. Thus, the picolinyl derivatization technique substantially increases the confidence in the structural identification of multi-methyl-branched fatty acids using mass spectrometry. Therefore, this picolinyl ester derivatization technique was also applied to determine the methylation pattern of the potentially novel MAs in the Censo seep soils (Fig. 3).

To illustrate this approach, we discuss the identification of the three major MAs. When analyzed as picolinyl ester derivatives (Fig. 3b, d and f), these MAs showed molecular ions (M+) 431, 515 and 557, indicating C22, C28 and C31 MAs, respectively. The mass spectrum of the picolinyl ester derivative C28 MA (Fig. 3d), the most abundant MA in the Censo seep soils, confirms the methylation at C-2 with the fragment ion of 165. Furthermore, this spectrum also shows abundant fragment ions at 178, 206, 220, 248, 262 and 290. Combined with the absence of the fragment ions at 192, 234 and 276, this strongly suggests the presence of three additional methyl groups at positions C-4, C-6 and C-8. The mass spectrum of the C22 picolinyl ester derivative (Fig. 3b) also confirms the methyl branch at position C-2 through the mass ion 165. Elevated fragment ions at 290 and 318 in combination with the low intensity of the fragment ion at 304 suggest a methyl group at position C-12. Further mass spectral interpretations can be made for the C31 MA, with a mass spectrum similar to that of the C28 MA but including an additional methyl group at position C-10, as indicated by the presence of fragment ions at 304 and 332 and the absence of a fragment ion at 318 (Fig. 3f). Thus, we tentatively identified these MAs as 2,12-dimethyl-eicosanoic acid (C22 2,12-dimethyl MA), 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl-tetracosanoic acid (C28 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl MA) and 2,4,6,8,10-pentamethyl-hexacosanoic acid (C31 2,4,6,8,10-pentamethyl MA), respectively (Figs. 2, 3 and Table 2). Other abundant MAs tentatively identified include 2-methyl-octadecanoic acid (C19 2-methyl MA), 2-methyl-nonadecanoic acid (C20 2-methyl MA), 2-methyl-eicosanoic acid (C21 2-methyl MA), 2,4,6-trimethyl-docosanoic acid (C25 2,4,6-trimethyl MA), 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl-pentacosanoic acid (C29 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl) and 2,4,6,8,16-pentamethyl-tetracosanoic acid (C29 2,4,6,8,16-pentamethyl MA) MAs (Fig. 2 and Table 2).

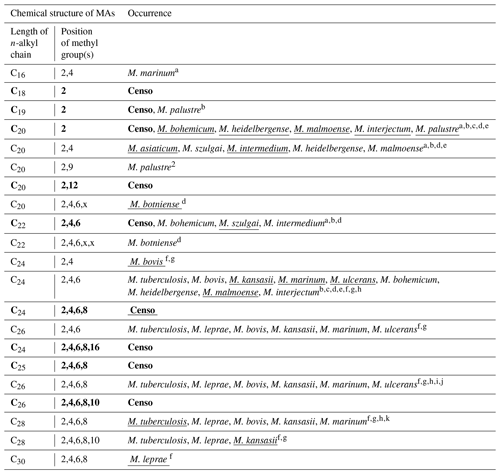

Table 2Chemical variability and occurrence of MAs in the Censo seep soils and in the most relevant mycobacterial species. The underlined names of the mycobacterial species indicate the major MA configuration in the mycobacterial species. The x in the position of methylations in the n-alkyl chain features an unidentified position of the methyl group. MAs indicated in bold typeface are MAs identified in the Censo seep soils.

a Chou et al. (1996). b Torkko et al. (2002). c Torkko et al. (2001). d Torkko et al. (2003). e Valero-Guillén et al. (1988). f Minnikin et al. (1993a). g Minnikin et al. (1985). h Daffé and Laneelle (1988). i Donoghue et al. (2017). j Redman et al. (2009). k Minnikin et al. (2002).

At the seep (0 m), the MAs have a high relative abundance, representing ca. 44 % of the total FAs. Their abundance decreases to ca. 20 % in the soil at 1.8 m from the seep, whereas MAs were not detected in the soil at 13.2 m distance from the seep (Fig. 2). These lipids show a similar distribution trend as the 16S rRNA gene-sequencing results, which show high relative abundances of sequences from mycobacteria at the seep (ca. 34.1 % at 0 m), decrease to 8.5 % at 1.8 m, and are <1 % at 13.2 m (Table 1). Therefore, both the specific structure and the 16S rRNA gene data strongly suggest that the unusual FAs are derived from mycobacteria.

3.3 Mycocerosic acids as biomarkers for mycobacteria in the environment

Mycocerosic acids are thought to be only synthesized by mycobacteria and have been mainly studied as biomarkers for diseases from pathogenic (e.g., M. tuberculosis or M. leprae) or opportunistic pathogenic (e.g., the M. simiae complex) mycobacteria in the last decades (e.g., Minnikin et al., 1993a, b; Torkko et al., 2003). These studies revealed a high structural variability of MAs with distribution patterns characteristic for different mycobacterial species. For example, the frequently studied M. tuberculosis shows a major C32 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl MA and M. leprae a C34 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl MA (Minnikin et al., 1993a, b), whereas other mycobacteria feature shorter-chain major MAs like C21 2-methyl MA in M. palustre and C22 2,4-dimethyl MA in M. intermedium (Chou et al., 1996; Torkko et al., 2002) (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

The Censo seep soils reveal a high number of tentatively identified MAs which have not been reported previously (Fig. 1 and Table 2), e.g., those biosynthesized by pathogenic mycobacteria like M. tuberculosis and M. leprae and by mycobacteria belonging to the more closely related M. simiae complex like M. heidelbergense (Minnikin et al., 1993a, b; Torkko et al., 2003). The MA distribution of the Censo seep soils is characterized by a dominant C28 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl MA, while the MA distribution of M. heidelbergense or M. palustre from the M. simiae complex is dominated by the C21 2-methyl MA. Other more distantly related environmental opportunistic pathogens besides those of the M. simiae complex, like M. marinum or M. intermedium, produce a dominant C27 2,4,6-trimethyl or C22 2,4-dimethyl MA. As mentioned earlier, pathogenic mycobacteria like M. tuberculosis feature a major C32 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl MA, and M. leprae produces a dominant C34 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl MA, clearly different from the major MA in the Censo soils (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Possibly, these unusual MAs could help to differentiate environmental Censo mycobacteria from opportunistic pathogenic and pathogenic mycobacteria in various modern and past environments.

Interestingly, the Censo mycobacteria show relatively high abundances of pentamethylated MAs (C29 2,4,6,8,16-pentamethyl MA and C31 2,4,6,8,10-pentamethyl MA) compared to other studied mycobacteria. M. kansasii has a dominant pentamethyl MA (C33 2,4,6,8,10-pentamethyl MA; Table 2), which was also been reported in M. tuberculosis and M. leprae albeit in very low abundances, while M. botniense features a partially identified pentamethylated C27 (2,4,6,x,x) MA (Minnikin et al., 1985; Daffé and Laneelle, 1988; Torkko et al., 2003). Shorter-chain MAs are also abundant in the Censo soils, some of which have been identified in other mycobacterial species (Fig. 1 and Table 2): C20 2-methyl MA (M. palustre), C21 2-methyl MA (e.g., M. palustre, M. heidelbergense or M. interjectum) and C25 2,4,6-trimethyl MA (M. bohemicum, M. szulgai and M. intermedium) (Torkko et al., 2001, 2002, 2003). The presence of C20 2-methyl and C21 2-methyl MAs in both Censo mycobacteria and mycobacteria from the closely related M. simiae complex indicate that these MAs might be a common feature in the M. simiae complex. However, these MAs have also been found in more distantly related mycobacterial species like M. interjectum and M. malmoense, while common pathogenic mycobacteria like M. tuberculosis or M. bovis do not produce these shorter-chain MAs. These pathogenic mycobacteria contain a C27 2,4,6-methyl MA (M. tuberculosis) and a C26 2,4-methyl (M. bovis) as the shortest-chain MAs (Minnikin et al., 1993a; Redman et al., 2009), which are not present in the Censo soils. Some more distantly related mycobacteria can even contain much shorter-chain fatty acids like C11 2-methyl MA (M. interjectum or M. intermedium), C15 2-methyl MA (e.g., M. kansasii or M. intermedium) or C16 2,4-dimethyl MA (M. marinum) (Torkko et al., 2003), but these are not found in the Censo MA inventory.

The most unique feature that distinguishes the MAs of the Censo mycobacteria from cultivated mycobacterial species is the occurrence of methyl groups in the middle of the fatty acid chain at positions C-12 and C-16 in C22 2,12-dimethyl and C29 2,4,6,8,16-pentamethyl MAs, respectively. To the best of our knowledge, this mid-chain methyl branching has only been reported once before, in the mycobacterial species M. palustre, also from the M. simiae complex (Torkko et al., 2002), which is closely related to the species living in the Censo soil. However, the methyl branching in M. palustre is at position C-9 (C22 2,9-dimethyl MA) (Torkko et al., 2002).

The fatty acid profile of the Censo soils shows longer-chain MAs (e.g., C28 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl and C31 2,4,6,8,10-pentamethyl MAs), which are even more abundant than C24 and C26 long-chain n-alkyl fatty acids. This feature has not been previously reported in mycobacteria including mycobacteria from the closely related M. simiae complex like M. heidelbergense and M. palustre, which synthesize much higher amounts of regular fatty acids over MAs (Torkko et al., 2002, 2003). Some mycobacterial species from the M. simiae complex (i.e., M. lentiflavum, M. florentinum and M. genavense) and other more distantly related mycobacteria (e.g., M. paraffinicum and M. smegmatis) (Torkko et al., 2002, 2003; Fernandes and Kolattukudy, 1997; Chou et al., 1998) do not even contain MAs.

In conclusion, the MA patterns in the Censo soil mycobacteria are clearly different from those of previously cultivated mycobacterial species. This could be caused by environmental conditions near the Censo seep, which may have induced adaptions and regulation processes within the biosynthesis systems of MAs in the Censo mycobacteria or may just be a chemotaxonomic feature. Further studies of other soils that contain mycobacteria should reveal how unique the MAs detected in the Censo soils are.

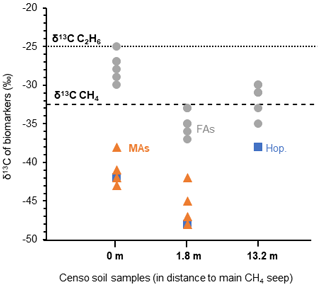

3.4 Role of the mycobacteria at the Censo seep

The high relative abundances of mycobacteria and MAs based on both the relative 16S rRNA gene abundance and FA composition in the soil close to the main Censo seep (Table 1 and Fig. 2), combined with the decrease in these abundances in soils further away from the seep, hint to the potential involvement of mycobacteria in gas oxidation processes at the gas seep system. To further investigate this, the δ13C values of the MAs, as well as regular fatty acids and hopanoic acids, were analyzed in the Censo seep soils (Fig. 5) and compared with that of the thermogenically derived methane (−30 ‰ to −35 ‰) and ethane (−25 ‰) at the Censo seep, as previously reported by Grassa et al. (2004).

Figure 5The stable carbon isotopic composition (δ13C) of biomarkers in the Censo soils at increasing distance from the main gas seepage. Biomarkers shown are fatty acids (FAs: grey circle), mycocerosic acids (MAs: orange triangle) and the C32 hopanoic acid (Hop.: blue square). Data points represent the mean average of two analysis. The δ13C values of the released methane ( ‰) and ethane ( ‰) are indicated by dashed lines in the plot.

At the seep site, regular and unsaturated C16, C18, C22 and C24 fatty acids showed no significant depletion in their carbon isotopic composition ( ‰ to −30 ‰), while at 1.8 m distance these FAs feature a bit more depleted δ13C values ranging from −33 ‰ to −37 ‰ (Fig. 5). As mentioned before, the C16 and C18 FAs could originate from Type I and Type II methanotrophs (e.g., Bowman, 2006; Dedysh et al., 2007; Bodelier et al., 2009), although larger depletion of ca. 10 ‰ to 20 ‰ relative to the methane source is generally expected for fatty acids of aerobic methanotrophs (Jahnke et al., 1999; Blumenberg et al., 2007; Berndmeyer et al., 2013). Thus, a mixed bacterial community of heterotrophic and methanotrophic bacteria (e.g., Inglis et al., 2019) or other soil microbes using soil organic matter as a carbon source are likely to contribute to the pool of these fatty acids at Censo 0 and 1.8 m. This agrees with the typical bulk δ13C values of −25 ‰ to −30 ‰ in temperate soils (Balesdent et al., 1987; Huang et al., 1996) and the presence of saturated and unsaturated C16 and C18 fatty acids even further away from the seep, at 13.2 m (Fig. 2).

The C32 17β,21β(H)-hopanoic acid shows more depleted δ13C values ranging from −42 ‰ to −48 ‰ at Censo 0 and 1.8 m, respectively (Fig. 5), suggesting an origin from bacteria involved in the cycling of a 13C-depleted carbon source like methane at this gas seep. The C32 hopanoic acid is a diagenetic product of bacteriohopanepolyols (Rohmer et al., 1984; Ries-Kautt and Albrecht, 1989; Farrimond et al., 2002), which could be produced by some of the aerobic methanotrophs (e.g., Methylocystaceae or Methylococcales) (Zundel and Rohmer, 1985; van Winden et al., 2012) identified in the Censo seep soils (Table 1). However, as discussed above, the mycobacteria in the soil, which are closely related to the M. simiae complex (Fig. 1), might also be able to synthesize hopanoids and therefore could be contributing to the hopanoid pool.

Depleted δ13C values are observed in the MAs (−38 ‰ to −48 ‰) close to the Censo seep at 0 and 1.8 m (Fig. 5), indicating that these are likely synthesized by organisms that use a 13C-depleted carbon source rather than soil organic matter. The Censo seep releases high amounts of methane (76 %–86 % of total released gas) and minor amounts of higher gaseous hydrocarbons (ethane, propane, etc.) as well as CO2 and N2 (Etiope et al., 2002; Grassa et al., 2004). Thus, it would appear that the Censo mycobacteria are using 13C-depleted methane as their carbon source as it is the major released gas at the Censo seep. This is in agreement with the decreasing relative abundance of mycobacteria and MAs away from the main seepage according to the decrease in the released gas. Furthermore, the δ13C values of the MAs are more negative than the δ13C value of the released methane, as expected for methanotrophs, and dissimilar to bulk soil organic matter and the simple FAs likely derived from heterotrophic bacteria.

However, these results are not completely in agreement with previous incubation and genetic studies, which showed that mycobacteria are not able to utilize methane but rather use other gaseous hydrocarbons like ethane and propane as well as alkenes, methanol and carbon monoxide as their carbon source (Park et al., 2003; Coleman et al., 2011, 2012; Martin et al., 2014). Studies from the 1950s reported high abundances of mycobacteria in soils from areas of oil and gas production and in areas of petroliferous gas seeps, hinting to their potential involvement in gas oxidation processes (Davis et al., 1956, 1959). Cultivation experiments of those soils confirmed that mycobacteria did not utilize methane but higher gaseous hydrocarbons (ethane and propane) (Davis et al., 1956; Dworkin and Foster, 1958). These results suggest that the mycobacteria in the Censo soils are perhaps not using methane but possibly other gaseous hydrocarbons in the seep, like ethane or propane. However, it should be noted that two previous studies have described mycobacterial species Mycobacterium flavum var. methanicum, Mycobacterium methanicum n. sp. and Mycobacterium ID-Y that were able to oxidize methane (Nechaeva, 1949; Reed and Dugan, 1987). Alternatively, mycobacteria at the Censo seep could act as indirect methane utilizers by using secondary products of methane oxidation performed by other methanotrophs, like methanol. Indeed, some studies have shown that cultured pathogenic mycobacteria were able to utilize methanol (Reed and Dugan, 1987; Park et al., 2003, 2010). However, this is difficult to reconcile with their very high abundances (up to 34.1 %) compared to the low abundance of typical methanotrophs like Methylococcales or Methylocystaceae (up to 5.1 %) near the seep (Table 1).

Overall, based on the clear abundance of mycobacterial 16S rRNA sequences in the Censo seep soils, the novel 13C-depleted MAs identified here may be useful biomarkers for the presence of hydrocarbon-oxidizing mycobacteria in soils. These unique MAs in combination with 13C depletion could be used to trace mycobacteria in present and past environments, specifically those influenced by hydrocarbon seepage. Longer-chain fatty acids and branched fatty acids like MAs have been shown to be more resistant than other biomolecules (e.g., short-chain fatty acids) to diagenetic changes in diverse studies of fossil forests, sediment cores from the Gulf of California and petroleum systems (Staccioli et al., 2002; Wenger et al., 2002; Camacho-Ibar et al., 2003). Under the right conditions, fatty acids may be preserved as bound compounds in ancient sediments through the Miocene (Ahmed et al., 2001). Indeed, studies have indicated the presence of MAs of M. tuberculosis on ancient bones from a 17 000-year-old bison and from a ca. 200-year-old human skeleton (Redman et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2012), suggesting a high preservation potential of these lipids.

Nevertheless, future research should investigate the presence and stable carbon isotope composition of MAs in other modern terrestrial and marine hydrocarbon seeps as well as in past environments where gas seepage might have played an important role. Additionally, further detailed incubation studies and genomic analysis of the Censo mycobacteria and mycobacteria at other terrestrial gas seeps are required to elucidate the exact role of the mycobacteria in gas oxidation processes at the Censo seep and in other gas-rich environments.

Soils from the Fuoco di Censo everlasting fire show high relative abundances (up to 34 %) of uncultivated mycobacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences. These Censo mycobacteria are phylogenetically distant from the typical pathogenic mycobacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis or M. leprae and more closely related to the M. simiae complex like M. heidelbergense and M. palustre. At the main seep, Censo soils feature a unique MA pattern, especially in the longer-chain MAs. The most abundant MAs were tentatively identified as 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl-tetracosanoic acid (C28 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl MA) and 2,4,6,8,10-pentamethyl-hexacosanoic acid (C31 2,4,6,8,10-pentamethyl MA). The Censo soils also contained MAs with novel mid-chain methyl branching at positions C-12 and C-16 (C22 2,12-dimethyl and C29 2,4,6,8,16-pentamethyl MAs). The MA pattern in the Censo seep soils is clearly different from those reported for the well-studied mycobacteria like M. tuberculosis or M. leprae and from the closely related M. simiae complex. Only C20 2-methyl, C21 2-methyl and C25 2,4,6-trimethyl MAs have been found previously in other mycobacteria from the M. simiae complex (e.g., M. heidelbergense) and three more distantly related mycobacteria (e.g., M. interjectum). These MAs have relatively low δ13C values, suggesting that Censo mycobacteria use a carbon source depleted in 13C, such as methane, higher gaseous hydrocarbons or secondary products of gas oxidation processes, like methanol. The novel identified MAs in the Censo samples offer a new tool, besides DNA-based techniques, to investigate soils from present and past terrestrial environments for the presence of mycobacteria potentially involved in the cycling of gases.

The 16S rRNA amplicon reads (raw data) have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject number PRJNA701386.

Data will be made available on request to the corresponding author.

NTS, DR and SS planned the research. NTS, FG and CRW collected the samples. MH and AJM provided the synthetic C27 mycocerosic acid standard. NTS performed lipid analysis. LV analyzed 16S rRNA gene-sequencing data. NTS, SS and LV interpreted the data. NTS wrote the paper with input from all authors.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We thank Marianne Baas, Monique Verweij, Jort Ossebaar, Ronald van Bommel, Sanne Vreugdenhil and Maartje Brouwer for technical assistance and Marcel van der Meer for discussion about isotopic values of the fatty acids. Sebastian Naeher, Rienk Smittenberg and Gordon Inglis are thanked for their useful comments which improved the manuscript.

Stefan Schouten, Laura Villanueva and Jaap S. Sinninghe Damsté have been supported by the Netherlands Earth System Science Center (NESSC) and the Soehngen Institute for Anaerobic Microbiology (SIAM) through Gravitation grants (grant nos. 024.002.001 and 024.002.002) from the Dutch Ministry for Education, Culture and Science.

This paper was edited by Sebastian Naeher and reviewed by Rienk Smittenberg and Gordon Inglis.

Abdala Asbun, A., Besseling, M. A., Balzano, S., van Bleijswijk, J. D. L., Witte, H. J., Villanueva, L., and Engelmann, J. C.: Cascabel: A Scalable and Versatile Amplicon Sequence Data Analysis Pipeline Delivering Reproducible and Documented Results, Frontiers in Genetics, 11, 1329, https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.489357, 2020.

Ahmed, M., Schouten, S., Baas, M., and De Leeuw, J.: Bound lipids in kerogens from the Monterey Formation, Naples Beach, California, The Monterey Formation: From Rock to Molecules, Columbia University Press, New York, 189–205, 2001.

Alugupalli, S., Sikka, M. K., Larsson, L., and White, D. C.: Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry methods for the analysis of mycocerosic acids present in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, J. Microbiol. Meth., 31, 143–150, 1998.

Andrews, S.: FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data, available at: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc (last access: 5 August 2018), 2010.

Bale, N. J., Villanueva, L., Hopmans, E. C., Schouten, S., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S.: Different seasonality of pelagic and benthic Thaumarchaeota in the North Sea, Biogeosciences, 10, 7195–7206, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-7195-2013, 2013.

Balesdent, J., Mariotti, A., and Guillet, B.: Natural 13C abundance as a tracer for studies of soil organic matter dynamics, Soil Biol. Biochem., 19, 25–30, 1987.

Bardgett, R. D. and van der Putten, W. H.: Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning, Nature, 515, 505–511, 2014.

Basilone, L.: Litostratigrafia della Sicilia, Dipartimento di scienze della terra e del mare, Università degli studi, Arti Grafiche Palermitane s.r.l, Palermo, Italy, ISBN: 978-88-97559-09-2, 2012.

Berndmeyer, C., Thiel, V., Schmale, O., and Blumenberg, M.: Biomarkers for aerobic methanotrophy in the water column of the stratified Gotland Deep (Baltic Sea), Org. Geochem., 55, 103–111, 2013.

Besseling, M. A., Hopmans, E. C., Boschman, R. C., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., and Villanueva, L.: Benthic archaea as potential sources of tetraether membrane lipids in sediments across an oxygen minimum zone, Biogeosciences, 15, 4047–4064, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-4047-2018, 2018.

Birgel, D. and Peckmann, J.: Aerobic methanotrophy at ancient marine methane seeps: a synthesis, Org. Geochem., 39, 1659–1667, 2008.

Blumenberg, M., Seifert, R., and Michaelis, W.: Aerobic methanotrophy in the oxic–anoxic transition zone of the Black Sea water column, Org. Geochem., 38, 84–91, 2007.

Bodelier, P. L., Gillisen, M.-J. B., Hordijk, K., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., Rijpstra, W. I. C., Geenevasen, J. A., and Dunfield, P. F.: A reanalysis of phospholipid fatty acids as ecological biomarkers for methanotrophic bacteria, The ISME journal, 3, 606–617, 2009.

Bouam, A., Armstrong, N., Levasseur, A., and Drancourt, M.: Mycobacterium terramassiliense, Mycobacterium rhizamassiliense and Mycobacterium numidiamassiliense sp. nov., three new Mycobacterium simiae complex species cultured from plant roots, Scientific Reports, 8, 1–13, 2018.

Bowman, J.: The methanotrophs – the families Methylococcaceae and Methylocystaceae, The Prokaryotes, 5, 266–289, 2006.

Bowman, J. P., Sly, L. I., Nichols, P. D., and Hayward, A.: Revised taxonomy of the methanotrophs: description of Methylobacter gen. nov., emendation of Methylococcus, validation of Methylosinus and Methylocystis species, and a proposal that the family Methylococcaceae includes only the group I methanotrophs, Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micr., 43, 735–753, 1993.

Brennan, P. J.: Structure, function, and biogenesis of the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Tuberculosis, 83, 91–97, 2003.

Brennan, P. J. and Nikaido, H.: The envelope of mycobacteria, Annu. Rev. Biochem., 64, 29–63, 1995.

Bull, I. D., Parekh, N. R., Hall, G. H., Ineson, P., and Evershed, R. P.: Detection and classification of atmospheric methane oxidizing bacteria in soil, Nature, 405, 175–1778, 2000.

Camacho-Ibar, V. F., Aveytua-Alcázar, L., and Carriquiry, J. D.: Fatty acid reactivities in sediment cores from the northern Gulf of California, Org. Geochem., 34, 425–439, 2003.

Caporaso, J. G., Lauber, C. L., Walters, W. A., Berg-Lyons, D., Huntley, J., Fierer, N., Owens, S. M., Betley, J., Fraser, L., and Bauer, M.: Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms, The ISME journal, 6, 1621–1624, 2012.

Chou, S., Chedore, P., Haddad, A., Paul, N., and Kasatiya, S.: Direct identification of Mycobacterium species in Bactec 7H12B medium by gas-liquid chromatography, J. Clin. Microbiol., 34, 1317–1320, 1996.

Chou, S., Chedore, P., and Kasatiya, S.: Use of gas chromatographic fatty acid and mycolic acid cleavage product determination to differentiate among Mycobacterium genavense, Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium simiae, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, J. Clin. Microbiol., 36, 577–579, 1998.

Christie, W. W.: Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry methods for structural analysis of fatty acids, Lipids, 33, 343–353, 1998.

Coleman, N. V., Yau, S., Wilson, N. L., Nolan, L. M., Migocki, M. D., Ly, M. a., Crossett, B., and Holmes, A. J.: Untangling the multiple monooxygenases of Mycobacterium chubuense strain NBB4, a versatile hydrocarbon degrader, Env. Microbiol. Rep., 3, 297–307, 2011.

Coleman, N. V., Le, N. B., Ly, M. A., Ogawa, H. E., Mc Carl, V., Wilson, N. L., and Holmes, A. J.: Hydrocarbon monooxygenase in Mycobacterium: recombinant expression of a member of the ammonia monooxygenase superfamily, The ISME journal, 6, 171–182, 2012.

Crossman, Z., Ineson, P., and Evershed, R.: The use of 13C labelling of bacterial lipids in the characterisation of ambient methane-oxidising bacteria in soils, Org. Geochem., 36, 769–778, 2005.

Daffé, M. and Laneelle, M.: Distribution of phthiocerol diester, phenolic mycosides and related compounds in mycobacteria, Microbiology, 134, 2049–2055, 1988.

Daffé, M., Quémard, A., and Marrakchi, H.: Mycolic Acids: From Chemistry to Biology, in: Biogenesis of Fatty Acids, Lipids and Membranes, Springer International Publishing, 181–216, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50430-8_18, 2019.

Davis, J., Chase, H., and Raymond, R.: Mycobacterium paraffinicum n. sp., a bacterium isolated from soil, Appl. Microbiol., 4, 310–315, 1956.

Davis, J., Raymond, R., and Stanley, J.: Areal contrasts in the abundance of hydrocarbon oxidizing microbes in soils, Appl. Microbiol., 7, 156–165, 1959.

Dedysh, S. N., Belova, S. E., Bodelier, P. L., Smirnova, K. V., Khmelenina, V. N., Chidthaisong, A., Trotsenko, Y. A., Liesack, W., and Dunfield, P. F.: Methylocystis heyeri sp. nov., a novel type II methanotrophic bacterium possessing “signature” fatty acids of type I methanotrophs, Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micr., 57, 472–479, 2007.

Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Oliverio, A. M., Brewer, T. E., Benavent-González, A., Eldridge, D. J., Bardgett, R. D., Maestre, F. T., Singh, B. K., and Fierer, N.: A global atlas of the dominant bacteria found in soil, Science, 359, 320–325, 2018.

Donoghue, H., Taylor, G., Stewart, G., Lee, O., Wu, H., Besra, G., and Minnikin, D.: Positive diagnosis of ancient leprosy and tuberculosis using ancient DNA and lipid biomarkers, Diversity, 9, 46, https://doi.org/10.3390/d9040046, 2017.

Dworkin, M. and Foster, J.: Experiments with some microorganisms which utilize ethane and hydrogen, J. Bacteriol., 75, 592–603, 1958.

Edgar, R. C.: MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput, Nucleic Acids Res., 32, 1792–1797, 2004.

Edgar, R. C.: Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST, Bioinformatics, 26, 2460–2461, 2010.

Etiope, G., Caracausi, A., Favara, R., Italiano, F., and Baciu, C.: Methane emission from the mud volcanoes of Sicily (Italy), Geophys. Res. Lett., 29, 56-51–56-54, 2002.

Etiope, G., Martinelli, G., Caracausi, A., and Italiano, F.: Methane seeps and mud volcanoes in Italy: gas origin, fractionation and emission to the atmosphere, Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, L14303, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL030341, 2007.

Falkinham, J. O.: The biology of environmental mycobacteria, Env. Microbiol. Rep., 1, 477–487, 2009.

Falkinham, J. O.: Environmental sources of nontuberculous mycobacteria, Clin. Chest Med., 36, 35–41, 2015.

Farrimond, P., Griffiths, T., and Evdokiadis, E.: Hopanoic acids in Mesozoic sedimentary rocks: their origin and relationship with hopanes, Org. Geochem., 33, 965–977, 2002.

Fernandes, N. D. and Kolattukudy, P. E.: Methylmalonyl coenzyme A selectivity of cloned and expressed acyltransferase and beta-ketoacyl synthase domains of mycocerosic acid synthase from Mycobacterium bovis BCG, J. Bacteriol., 179, 7538–7543, 1997.

Fierer, N., Leff, J. W., Adams, B. J., Nielsen, U. N., Bates, S. T., Lauber, C. L., Owens, S., Gilbert, J. A., Wall, D. H., and Caporaso, J. G.: Cross-biome metagenomic analyses of soil microbial communities and their functional attributes, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 109, 21390–21395, 2012.

Francis, G. W.: Alkylthiolation for the determination of double-bond position in unsaturated fatty acid esters, Chem. Phys. Lipids, 29, 369–374, 1981.

Frostegård, Å., Tunlid, A., and Bååth, E.: Use and misuse of PLFA measurements in soils, Soil Biol. Biochem., 43, 1621–1625, 2011.

Gago, G., Diacovich, L., Parabolize, A., Tsai, S.-C., and Gramajo, H.: Fatty acid biosynthesis in actinomycetes, FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 35, 475–497, 2011.

Grassa, F., Capasso, G., Favara, R., Inguaggiato, S., Faber, E., and Valenza, M.: Molecular and isotopic composition of free hydrocarbon gases from Sicily, Italy, Geophys. Res. Lett., 31, L06607, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL019362, 2004.

Hamieh, A., Tayyar, R., Tabaja, H., EL Zein, S., Bou Khalil, P., Kara, N., Kanafani, Z. A., Kanj, N., Bou Akl, I., and Araj, G.: Emergence of Mycobacterium simiae: A retrospective study from a tertiary care center in Lebanon, PloS One, 13, e0195390, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195390, 2018.

Harvey, D. J.: Picolinyl esters for the structural determination of fatty acids by GC/MS, Mol. Biotechnol., 10, 251–260, 1998.

Heap, B.: Mycobacterium simiae as a cause of intra-abdominal disease: a case report, Tubercle, 70, 217–221, 1989.

Hennessee, C. T., Seo, J.-S., Alvarez, A. M., and Li, Q. X.: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading species isolated from Hawaiian soils: Mycobacterium crocinum sp. nov., Mycobacterium pallens sp. nov., Mycobacterium rutilum sp. nov., Mycobacterium rufum sp. nov. and Mycobacterium aromaticivorans sp. nov, Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micr., 59, 378–387, 2009.

Holzheimer, M., Reijneveld, J. F., Ramnarine, A. K., Misiakos, G., Young, D. C., Ishikawa, E., Cheng, T.-Y., Yamasaki, S., Moody, D. B., Van Rhijn, I. and Minnaard A. J.: Asymmetric Total Synthesis of Mycobacterial Diacyl Trehaloses Demonstrates a Role for Lipid Structure in Immunogenicity, ACS Chem. Biol., 7, 1835–1841, 2020.

Huang, Y., Bol, R., Harkness, D. D., Ineson, P., and Eglinton, G.: Post-glacial variations in distributions, 13C and 14C contents of aliphatic hydrocarbons and bulk organic matter in three types of British acid upland soils, Org. Geochem., 24, 273–287, 1996.

Inglis, G. N., Naafs, B. D. A., Zheng, Y., Mc Clymont, E. L., Evershed, R. P., and Pancost, R. D.: Distributions of geohopanoids in peat: Implications for the use of hopanoid-based proxies in natural archives, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 224, 249–261, 2018.

Inglis, G. N., Naafs, B. D. A., Zheng, Y., Schellekens, J., and Pancost, R. D.: δ13C values of bacterial hopanoids and leaf waxes as tracers for methanotrophy in peatlands, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 260, 244–256, 2019.

Jackson, M., Stadthagen, G., and Gicquel, B.: Long-chain multiple methyl-branched fatty acid-containing lipids of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: biosynthesis, transport, regulation and biological activities, Tuberculosis, 87, 78–86, 2007.

Jahnke, L. L., Summons, R. E., Hope, J. M., and Des Marais, D. J.: Carbon isotopic fractionation in lipids from methanotrophic bacteria II: The effects of physiology and environmental parameters on the biosynthesis and isotopic signatures of biomarkers, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 63, 79–93, 1999.

Kweon, O., Kim, S.-J., Blom, J., Kim, S.-K., Kim, B.-S., Baek, D.-H., Park, S. I., Sutherland, J. B., and Cerniglia, C. E.: Comparative functional pan-genome analyses to build connections between genomic dynamics and phenotypic evolution in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolism in the genus Mycobacterium, BMC Evol. Biol., 15, 21, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-015-0302-8, 2015.

Lamb, D. C., Kelly, D. E., Manning, N. J., and Kelly, S. L.: A sterol biosynthetic pathway in Mycobacterium, FEBS Lett., 437, 142–144, 1998.

Lee, O. Y., Wu, H. H., Donoghue, H. D., Spigelman, M., Greenblatt, C. L., Bull, I. D., Rothschild, B. M., Martin, L. D., Minnikin, D. E., and Besra, G. S.: Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex lipid virulence factors preserved in the 17,000-year-old skeleton of an extinct bison, Bison antiquus, PLoS ONE, 7, e41923, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0041923, 2012.

Lévy-Frébault, V., Pangon, B., Buré, A., Katlama, C., Marche, C., and David, H.: Mycobacterium simiae and Mycobacterium avium-M. intracellulare mixed infection in acquired immune deficiency syndrome, J. Clin. Microbiol., 25, 154–157, 1987.

Lough, A.: The chemistry and biochemistry of phytanic, pristanic and related acids, Progress in the Chemistry of Fats and other Lipids, 14, 1–48, 1975.

Martin, K. E., Ozsvar, J., and Coleman, N. V.: SmoXYB1C1Z of Mycobacterium sp. strain NBB4: a soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO)-like enzyme, active on C2 to C4 alkanes and alkenes, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 80, 5801–5806, 2014.

Miller, C., Child, R., Hughes, J., Benscai, M., Der, J., Sims, R., and Anderson, A.: Diversity of soil mycobacterium isolates from three sites that degrade polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, J. Appl. Microbiol., 102, 1612–1624, 2007.

Minnikin, D., Dobson, G., Goodfellow, M., Magnusson, M., and Ridell, M.: Distribution of some mycobacterial waxes based on the phthiocerol family, Microbiology, 131, 1375–1381, 1985.

Minnikin, D., Besra, G., Bolton, R., Datta, A., Mallet, A., Sharif, A., Stanford, J., Ridell, M., and Magnusson, M.: Identification of the leprosy bacillus and related mycobacteria by analysis of mycocerosate profiles, Ann. Soc. Belg. Med. Tr., 73, 25–34, 1993a.

Minnikin, D., Bolton, R., Hartmann, S., Besra, G., Jenkins, P., Mallet, A., Wilkins, E., Lawson, A., and Ridell, M.: An integrated procedure for the direct detection of characteristic lipids in tuberculous patients, Ann. Soc. Belg. Med. Tr., 73, 13–24, 1993b.

Minnikin, D. E., Kremer, L., Dover, L. G., and Besra, G. S.: The methyl-branched fortifications of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Chem. Biol., 9, 545–553, 2002.

Nechaeva, N: Two species of methane oxidizing mycobacteria. Mikrobiologiya, 18, 310–317, 1949 (English Translation: Associated Technical Service, East Orange, NJ).

Nei, M. and Kumar, S.: Molecular evolution and phylogenetics, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 0-19-513584-9, 2000.

Nichols, P. D., Guckert, J. B., and White, D. C.: Determination of monosaturated fatty acid double-bond position and geometry for microbial monocultures and complex consortia by capillary GC-MS of their dimethyl disulphide adducts, J. Microbiol. Meth., 5, 49–55, 1986.

Nicoara, S. C., Minnikin, D. E., Lee, O. C., O'Sullivan, D. M., McNerney, R., Pillinger, C. T., Wright, I. P., and Morgan, G. H.: Development and optimization of a gas chromatography/mass spectrometry method for the analysis of thermochemolytic degradation products of phthiocerol dimycocerosate waxes found in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Rapid Commun. Mass Sp., 27, 2374–2382, 2013.

Ourisson, G., Albrecht, P., and Rohmer, M.: The hopanoids: palaeochemistry and biochemistry of a group of natural products, Pure Appl. Chem., 51, 709–729, 1979.

Park, H., Lee, H., Ro, Y. T., and Kim, Y. M.: Identification and functional characterization of a gene for the methanol: N, N′-dimethyl-4-nitrosoaniline oxidoreductase from Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1 (DSM 3803), Microbiology, 156, 463–471, 2010.

Park, S. W., Hwang, E. H., Park, H., Kim, J. A., Heo, J., Lee, K. H., Song, T., Kim, E., Ro, Y. T., and Kim, S. W.: Growth of mycobacteria on carbon monoxide and methanol, J. Bacteriol., 185, 142–147, 2003.

Peterse, F., Nicol, G. W., Schouten, S., and Damsté, J. S. S.: Influence of soil pH on the abundance and distribution of core and intact polar lipid-derived branched GDGTs in soil, Org. Geochem., 41, 1171–1175, 2010.

Podust, L. M., Poulos, T. L., and Waterman, M. R.: Crystal structure of cytochrome P450 14α-sterol demethylase (CYP51) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis in complex with azole inhibitors, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 3068–3073, 2001.

Ran-Ressler, R. R., Lawrence, P., and Brenna, J. T.: Structural characterization of saturated branched chain fatty acid methyl esters by collisional dissociation of molecular ions generated by electron ionization, J. Lipid Res., 53, 195–203, 2012.

Redman, J. E., Shaw, M. J., Mallet, A. I., Santos, A. L., Roberts, C. A., Gernaey, A. M., and Minnikin, D. E.: Mycocerosic acid biomarkers for the diagnosis of tuberculosis in the Coimbra Skeletal Collection, Tuberculosis, 89, 267–277, 2009.

Reed, W. M. and Dugan, P. R.: Isolation and characterization of the facultative methylotroph Mycobacterium ID-Y, Microbiology, 133, 1389–1395, 1987.

Řezanka, T. and Sigler, K.: Odd-numbered very-long-chain fatty acids from the microbial, animal and plant kingdoms, Prog. Lipid Res., 48, 206–238, 2009.

Ries-Kautt, M. and Albrecht, P.: Hopane-derived triterpenoids in soils, Chem. Geol., 76, 143–151, 1989.

Rohmer, M., Bouvier-Nave, P., and Ourisson, G.: Distribution of hopanoid triterpenes in prokaryotes, Microbiology, 130, 1137–1150, 1984.

Schouten, S., Hopmans, E. C., Baas, M., Boumann, H., Standfest, S., Könneke, M., Stahl, D. A., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S.: Intact membrane lipids of “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus maritimus”, a cultivated representative of the cosmopolitan mesophilic group I crenarchaeota, Appl. Environ. Microb., 74, 2433–2440, 2008.

Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., Rijpstra, W. I. C., Schouten, S., Fuerst, J. A., Jetten, M. S., and Strous, M.: The occurrence of hopanoids in planctomycetes: implications for the sedimentary biomarker record, Org. Geochem., 35, 561–566, 2004.

Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., Rijpstra, W. I. C., Dedysh, S. N., Foesel, B. U., and Villanueva, L.: Pheno-and genotyping of hopanoid production in Acidobacteria, Front. Microbiol., 8, 968, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00968, 2017.

Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., Rijpstra, W. I. C., Foesel, B. U., Huber, K. J., Overmann, J., Nakagawa, S., Kim, J. J., Dunfield, P. F., Dedysh, S. N., and Villanueva, L.: An overview of the occurrence of ether-and ester-linked iso-diabolic acid membrane lipids in microbial cultures of the Acidobacteria: Implications for brGDGT paleoproxies for temperature and pH, Org. Geochem., 124, 63–76, 2018.

Staccioli, G., McMillan, N., Meli, A., and Bartolini, G.: Chemical characterisation of a 45-million-year bark from Geodetic Hills fossil forest, Axel Heiberg Island, Canada, Wood Sci. Technol., 36, 419–427, 2002.

Talbot, H. M., Mc Clymont, E. L., Inglis, G. N., Evershed, R. P., and Pancost, R. D.: Origin and preservation of bacteriohopanepolyol signatures in Sphagnum peat from Bissendorfer Moor (Germany), Org. Geochem., 97, 95–110, 2016.

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A., and Kumar, S.: MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0, Mol. Biol. Evol., 30, 2725–2729, 2013.

Thiel, V., Blumenberg, M., Pape, T., Seifert, R., and Michaelis, W.: Unexpected occurrence of hopanoids at gas seeps in the Black Sea, Org. Geochem., 34, 81–87, 2003.

Tiedje, J. M., Asuming-Brempong, S., Nüsslein, K., Marsh, T. L., and Flynn, S. J.: Opening the black box of soil microbial diversity, Appl. Soil Ecol., 13, 109–122, 1999.

Torkko, P., Suomalainen, S., Iivanainen, E., Suutari, M., Paulin, L., Rudbäck, E., Tortoli, E., Vincent, V., Mattila, R., and Katila, M.-L.: Characterization of Mycobacterium bohemicum isolated from human, veterinary, and environmental sources, J. Clin. Microbiol., 39, 207–211, 2001.

Torkko, P., Suomalainen, S., Iivanainen, E., Tortoli, E., Suutari, M., Seppänen, J., Paulin, L., and Katila, M.-L.: Mycobacterium palustre sp. nov., a potentially pathogenic, slowly growing mycobacterium isolated from clinical and veterinary specimens and from Finnish stream waters, Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micr., 52, 1519–1525, 2002.

Torkko, P., Katila, M.-L., and Kontro, M.: Gas-chromatographic lipid profiles in identification of currently known slowly growing environmental mycobacteria, J. Med. Microbiol., 52, 315–323, 2003.

Tortoli, E.: Microbiological features and clinical relevance of new species of the genus Mycobacterium, Clin. Microbiol. Rev., 27, 727–752, 2014.

Trincianti, E., Frixa, A., and Sartorio, D.: Palynology and stratigraphic characterization of subsurface sedimentary successions in the Sicanian and Imerese Domains–Central Western Sicily, Rev. Palaeobot. Palyno., 218, 48–66, 2015.

Valero-Guillén, P., Martín-Luengo, F., Larsson, L., Jimenez, J., Juhlin, I., and Portaels, F.: Fatty and mycolic acids of Mycobacterium malmoense, J. Clin. Microbiol., 26, 153–154, 1988.

van Winden, J. F., Talbot, H. M., Kip, N., Reichart, G.-J., Pol, A., McNamara, N. P., Jetten, M. S., Op den Camp, H. J., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S.: Bacteriohopanepolyol signatures as markers for methanotrophic bacteria in peat moss, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 77, 52–61, 2012.

van Winden, J. F., Talbot, H. M., Reichart, G.-J., McNamara, N. P., Benthien, A., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S.: Influence of temperature on the δ13C values and distribution of methanotroph-related hopanoids in Sphagnum-dominated peat bogs, Geobiology, 18, 497–507, https://doi.org/10.1111/gbi.12389, 2020.

Walsh, C. M., Gebert, M. J., Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Maestre, F., and Fierer, N.: A global survey of mycobacterial diversity in soil, Appl. Environ. Microb., 85, e01180-19, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01180-19, 2019.

Weijers, J. W., Panoto, E., van Bleijswijk, J., Schouten, S., Rijpstra, W. I. C., Balk, M., Stams, A. J., and Damste, J. S. S.: Constraints on the biological source(s) of the orphan branched tetraether membrane lipids, Geomicrobiol. J., 26, 402–414, 2009.

Wenger, L. M., Davis, C. L., and Isaksen, G. H.: Multiple controls on petroleum biodegradation and impact on oil quality, SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng., 5, 375–383, 2002.

World Health Organization: World health statistics 2019: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals, World Health Organization, 120 pp., ISBN: 9241565705, 2019.

Zhang, J., Kobert, K., Flouri, T., and Stamatakis, A.: PEAR: a fast and accurate Illumina Paired-End reAd mergeR, Bioinformatics, 30, 614–620, 2013.

Zundel, M. and Rohmer, M.: Prokaryotic triterpenoids: 1. 3β-Methylhopanoids from Acetobacter species and Methylococcus capsulatus, Eur. J. Biochem., 150, 23–27, 1985.