the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Hydrogen and carbon isotope fractionation factors of aerobic methane oxidation in deep-sea water

Shinsuke Kawagucci

Yohei Matsui

Akiko Makabe

Tatsuhiro Fukuba

Yuji Onishi

Takuro Nunoura

Taichi Yokokawa

Isotope fractionation factors associated with various biogeochemical processes are important in ensuring the reliable use of isotope tracers in biogeosciences at large. Methane is a key component of the subsurface biosphere and a notable greenhouse gas, making the accurate evaluation of methane cycles, including microbial methanotrophy, imperative. Although the isotope fractionation factors associated with methanotrophy have been examined under various conditions, the dual-isotope fractionation factors of aerobic methanotrophy in oxic seawater remain unclear. Here, we investigated hydrogen and carbon isotope ratios of methane as well as the relevant biogeochemical parameters and microbial community compositions in hydrothermal plumes in the Okinawa Trough. Methanotrophs were found to be abundant in plumes above the Hatoma Knoll vent site, and we succeeded in simultaneously determining hydrogen and carbon isotope fractionation factors associated with the aerobic oxidation of methane ( ‰, ‰) – the former being the first of its kind ever reported. This εH value is comparable with values reported from terrestrial ecosystems but clearly lower than those from aerobic and anaerobic methanotroph enrichment cultures, as well as incubations of methanotrophic isolates. The covariation factor between δ13C and δD, Λ (9.4 or 8.8 determined using two different methods), was consistent with those from methanotrophic isolate incubations. These values are valuable for understanding dynamics of methane cycling in the marine realm, and future applications of the approach to other habitats with methanotrophic activity will help reveal whether the small εH value observed is a ubiquitous feature across all marine systems.

- Article

(4909 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(57 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Stable isotope ratios have been widely used for tracing biogeochemical cycles and microbial activities (e.g., Ohkouchi et al., 2010; Sharp, 2017). To ensure the reliable use of isotope tracers in biogeoscience, it is important to understand the isotope fractionation factors associated with expected processes in the environment of interest. The isotope fractionation factor associated with microbial metabolism is known to be variable due to physiological responses to environmental conditions such as temperature and substrate availability (e.g., Valentine et al., 2004). As the complex biogeochemistry of a natural system cannot be practically rebuilt in full in either laboratory or models, determination of the fractionation factor in the natural environment is most appropriately done via observation.

Measuring multiple-isotope ratios of a compound is a powerful tool to trace a specific process. Currently available multi-isotope-ratio approaches include mass-independent fractionations (e.g., Farquhar et al., 2000; Michalski et al., 2003), position-specific differences (Blair et al., 1987; Yoshida and Toyoda, 2000), multiple substitution “clumped” isotopes (Affek and Eiler, 2006; Ghosh et al., 2006), and multi-element isotope ratios of a compound (e.g., Vogt et al., 2016). Among these, the two-dimensional analysis of dual-element isotope ratios in compounds, such as δ15N and δ18O of nitrite (Casciotti, 2016) and δ13C and δ37Cl of methyl chloride (Konno et al., 2013), is the most conventional method. As isotope effects associated with molecular dynamics, such as diffusion, occur to the same extent for each element in a compound, the two-dimensional analysis is useful in distinguishing the processes producing and consuming the compound.

Methane (CH4) is a representative compound of the subsurface environment (e.g., Ijiri et al., 2018) and is also a notable atmospheric compound due to its strong greenhouse effect (e.g., Saunois et al., 2020). As such, the accurate evaluation of the marine CH4 cycle is a matter of urgency (Reeburgh, 2007; Dean et al., 2018). Two-dimensional analysis with carbon and hydrogen isotope ratios has been applied to trace the origins and behaviors of CH4 (Whiticar et al., 1986; Sugimoto and Wada, 1995; Nadalig et al., 2013). The kinetic isotope effect on the cleavage of the C–H bond in CH4 causes isotope fractionation in the remnant CH4. Carbon and hydrogen isotope fractionation factors associated with the microbial consumption of CH4, methanotrophy, mediated by enzymes such as methane monooxygenase, have been determined through incubation of isolates (Feisthauer et al., 2011), incubation of enrichment cultures (Coleman et al., 1981; Kinnaman et al., 2007; Holler et al., 2009; Rasigraf et al., 2012), and observations in the natural environment (Snover and Quay, 2000; Kessler et al., 2006). While wide variations in isotope fractionation have been observed in each, with a factor between 2 ‰–36 ‰ for carbon and 36 ‰–320 ‰ for hydrogen, the ratio between carbon and hydrogen fractionation factors falls into a narrow range of 6–15 regardless of magnitudes of the fractionations (Feisthauer et al., 2011; Rasigraf et al., 2012, and references therein). The dual-isotope fractionation factors associated with methanotrophy have been examined under a variety of environmental and physiological properties such as aerobic–anaerobic, terrestrial and marine, temperatures, and forms of key enzyme methane monooxygenase (reviewed by Feisthauer et al., 2011; Rasigraf et al., 2012). Despite these efforts, the dual-isotope fractionation factors of methanotrophy in oxic seawater have never been determined. Only the carbon isotope fractionation factors of aerobic methanotrophy have been determined in oxic seawater, through observations of CH4-rich hydrothermal plumes (Tsunogai et al., 2000; Gharib, 2005; Gamo et al., 2010; Kawagucci et al., 2010).

Here, we studied both hydrogen and carbon isotope ratios of CH4, as well as the relevant biogeochemical processes and microbial community compositions, in plumes above two hydrothermal vents in the Okinawa Trough, at the Hatoma Knoll site and the Daisan-Kume Knoll ANA site, in order to simultaneously determine hydrogen and carbon isotope fractionation factors associated with aerobic oxidation of CH4 in the marine environment. High-resolution vertical samplings inside and above seamount craters, at the base of which the vents are located, allowed us to capture gradual biogeochemical alteration of the plumes. Since vigorous venting of fluids with high CH4 concentration (> 10 mM) with CH4-bearing boiling-derived bubbles at Hatoma Knoll (Toki et al., 2016) contrasts with relatively weak discharge of fluids with lower CH4 concentration (< 1 mM) at the ANA site (Makabe et al., 2016), our initial intention was to reveal critical mechanisms controlling the fractionation factors by comparing them. We successfully determined the first hydrogen isotope fractionation factor of aerobic methanotrophy in seawater column at the Hatoma site, along with carbon isotope fractionation factors consistent with those reported to date (Tsunogai et al., 2000; Gharib, 2005; Gamo et al., 2010; Kawagucci et al., 2010).

2.1 Sampling

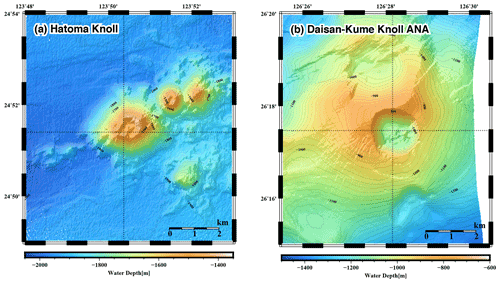

Seawater samples were collected during R/V Mirai cruise MR17-03C in 2017 (Brisbin et al., 2020) above two active deep-sea hydrothermal vent sites (Fig. 1), including the Hatoma Knoll site (depth: 1531 m) (Toki et al., 2016) and the Daisan-Kume Knoll ANA site (depth: 1079 m) (Makabe et al., 2016; Uyeno et al., 2020). Hatoma Knoll is characterized by vigorous venting of fluids at 323 ∘C with boiling-derived bubbles. The galatheoid squat lobster Shinkaia crosnieri, exhibiting ectosymbiosis with a microbial community of methanotrophs and thiotrophs (Watsuji et al., 2014), is dominant and densely distributed across the hydrothermally active area of Hatoma Knoll. Discovered in 2015 near Kumejima, the ANA site takes its name from an acronym of “Acoustic anomaly from Narrow pit Areas on caldera floor” (Nakamura et al., 2015), with a double meaning where ana means “hole” in Japanese. The maximum measured vent fluid temperature at the ANA site was 229 ∘C. The total vent fluid flux of the ANA site appeared to be more than an order of magnitude lower than that of Hatoma Knoll (unpublished data). Active venting at both sites is located on the bottom of the caldera at the top of the knolls, with the surrounding caldera walls being approximately 200 m high (Fig. 1).

Figure 1Seafloor topography of the (a) Hatoma Knoll site and (b) ANA site. Sampling locations are indicated as cross points of dotted lines.

High-resolution vertical sampling with 23 seawater samples collected within 400 m altitude from the seafloor was conducted just above the center of activity at both vent sites (Hatoma Knoll: 24∘51.426′ N–123∘50.328′ E – 1531 m, ANA site: 26∘17.490′ N–126∘28.158′ E – 1079 m) using a conductivity–temperature–depth (CTD) profiler with a Carousel Multiple Sampling (CMS) system. The CTD–CMS system deployed during the MR17-03C cruise consisted of a CTD sensor (SBE911plus, Sea-bird Scientific), a SBE32 Carousel water sampler (Sea-bird Scientific) for 36 Niskin-X bottles, a dissolved oxygen (DO) sensor (RINKO), and a turbidity meter (Seapoint turbidity meter, Sea-Bird Scientific).

2.2 Analytical procedure

Concentrations and dual-isotope ratios of CH4 and nitrous oxide (N2O) in the seawater samples were measured by a custom-made purge-and-trap system with a MAT253 isotope-ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS), following previously published methods (Hirota et al., 2010) and modifications (Okumura et al., 2016; Kawagucci et al., 2018). Immediately after the recovery of the CTD–CMS system on deck, each seawater sample in the Niskin bottle was subsampled into a 120 mL glass vial, sealed with a butyl rubber septum and aluminum cap after the addition of 0.2 mL mercury-chloride-saturated solution, and stored at 4 ∘C until shore-based measurement in laboratories at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), Yokosuka.

Each seawater sample was transferred by helium stream (rate: 100 mL min−1) into a 250 mL purge bottle to extract dissolved gases by helium bubbling and magnetic stirring. CH4 and N2O in the stripped gas were purified by passing through a stainless-steel tubing coil trap held at −110 ∘C (ethanol liquid-N2 bath) as well as a chemical trap filled with magnesium perchlorate (Mg(ClO4)2; Merck KGaA) and Ascarite II (sodium-hydroxide-coated silica; Thomas Scientific), followed by a stainless-steel tubing trap filled with HayeSep-D porous polymer (60/80 mesh, Hayes Separations Inc.) held at −130 ∘C (ethanol liquid-N2 bath). Then, the CH4 and N2O on the HayeSep-D trap were released into another helium stream (rate: 1.0 mL min−1) and again condensed on a capillary trap made of PoraPLOT Q (20 cm long, 0.32 mm i.d.) held at −196 ∘C (liquid-N2 bath) for cryofocus, and finally released at room temperature.

After the complete separation of CH4 and N2O from the other molecules using a GS Carbon-PLOT capillary column (30 m long, 0.32 mm i.d.) at 40 ∘C, the effluent CH4 was put through a 960 ∘C combustion unit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to convert into CO2 prior to introduction into MAT253 via an open-split interface (GCC III, Thermo Fisher Scientific). N2O was introduced into GCC III and IRMS without conversion. Carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen isotope ratios were obtained through simultaneous monitoring of CO and N2O+ isotopologues at , 45, and 46 by Faraday cups with 10-times-higher resistors, for increased sensitivity compared to commercially available general settings (Kawagucci et al., 2018). For the determination of hydrogen isotope ratio of CH4, another vial of the same sample was used, with the analytical procedure being almost identical to the above except a 1440 ∘C pyrolysis unit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) was applied for conversion into H2, and 3 (Okumura et al., 2016). Isotope ratios are represented by conventional δ notation and presented at a per mill scale. Errors for the analyses of deep-sea water conducted during the present study were estimated from repeated analyses of a sample and were within 10 % for N2O concentration, 0.2 ‰ for δ15N, 0.5 ‰ for δ18O, 20 % for CH4 concentration, 0.3 ‰ for δ13C, and 5 ‰ for δD. Results of the N2O analysis are provided in Table S1 in the Supplement.

Isotope fractionation factor caused by kinetics, ε (‰), can be expressed by the following equation:

where k is reaction constant while () is the kinetic isotope effect and superscripts “h” and “l” represent the heavier isotopologue (e.g., 13C) and the lighter one (e.g., 12C), respectively. Observations of fractional yield and isotope composition of the reactant in a closed system can be used to determine the fractionation factor using the following equation (Mariotti et al., 1981):

where the subscripts designate initial reactant (r0) and reactant remaining in a sample (rx), and f represents the fraction of the reactant consumed after the reaction. When δrx is plotted as a function of ln (1−f), the ε value is given by the slope of the line. A factor expressing covariation between δ13C and δD, Λ, is defined (Elsner, 2010; Feisthauer et al., 2011) by the following equation:

Assuming variations in the isotope ratios of CH4 in the environment are attributable solely to CH4 oxidation, Λ can also be calculated using another equation without the parameter f from discriminations of isotope ratios observed (Tsunogai et al., 2020), as follows:

The manganese concentration was measured in a laboratory of Kaiyo-Keisoku Co. Ltd. (Kei Okamura) using 100 mL of unfiltered seawater via the luminol–H2O2 chemiluminescence detection method (Ishibashi et al., 1997; Kawagucci et al., 2018) calibrated with the international standard NASS-5. Ammonium concentrations were determined on board the research vessel with the conventional autoanalyzer method.

The concentration of particulate ATP (pATP) was determined by a luciferin–luciferase assay on board the ship. Seawater samples collected using the CTD–CMS were transferred aseptically to clean plastic tubes, and an aliquot of this subsample was immediately filtrated through a sterilized membrane filter unit (0.2 µm pore size). Concentrations of ATP in both unfiltered and filtered aliquots were measured with a simplified quantification assay using the ATP assay kit (CheckLight HS, Kikkoman Biochemifa) without pre-concentration and extraction process. To start, 100 µL of cell lysis reagent was directly added to 100 µL of seawater sample for ATP extraction in a disposable test tube. After leaving the lysate for at least 30 min at room temperature to minimize the effect of temperature differences between the samples, 100 µL of the luciferin–luciferase mixture reagent was added to the lysate, and the luminescence intensity was immediately measured using a desktop photodetector (Luminescencer Octa AB-2270, ATTO). The ATP concentrations from unfiltered and filtered subsamples were regarded as total ATP and dissolved ATP, respectively. The pATP concentration was calculated by subtracting the dissolved ATP concentration from the total ATP concentration.

Samples for measuring the microbial cell density were fixed with 0.5 % (wt v) glutaraldehyde (final concentration) in 2 mL cryo-vials on board and stored at −80 ∘C until further analysis. For cell density measurements, 200 µL of each sample was stained by SYBR Green I nucleic acid gel stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific, ×5 of manufacture's stock) at room temperature for >10 min. The total microbial cell abundance in 100 µL of sample was determined using an Attune NxT acoustic focusing flow cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) by their signature in a plot of green fluorescence versus side scatter (Brussaard, 2004; Giorgio et al., 1996).

To obtain microbial community structure based on amplicon sequencing of the 16 rRNA gene, 2–4 L seawater samples were filtered with 0.2 µm pore-size cellulose nitrate or acetate membrane filters. The filters were stored at −80 ∘C until environmental DNA extraction, following previously published methods (Hirai et al., 2017). The 16S SSU rRNA gene was amplified from the extracted DNA with the primer mixture of 530F and 907R, using the LA Taq polymerase with GC buffer (Takara Bio) as described previously (Nunoura et al., 2012; Hiraoka et al., 2020). The amplicon sequencing libraries were sequenced using an Illumina MiSeq high-throughput sequencer (2×300 paired-end platform) at JAMSTEC. The sequence data generated herein are publicly available in the DDBJ sequence read archive (DRA) under the BioProject PRJDB11835.

Raw paired-end reads were merged using PEAR v0.9.10 (Zhang et al., 2014), and primer sequences were removed using Cutadapt v1.10 (Martin, 2011). Low-quality (Q score < 30 in over 3 % of sequences) and short (<150 bp) reads were filtered out using a custom perl script. A total of 5 996 472 SSU rRNA gene sequences from 59 samples were analyzed using the QIIME2 v 2019.4.0 pipeline (Bolyen et al., 2019). Unique amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were generated using the DADA2 plugin wrapped in QIIME2, and chimeric sequences were removed (Callahan et al., 2016). The taxa were assigned to the ASVs for 16S rRNA genes using the QIIME2 plugin feature classifier classify-sklearn (Bokulich et al., 2018) to search against the SILVA 138 database (Quast et al., 2013).

3.1 Hydrothermal plume signature

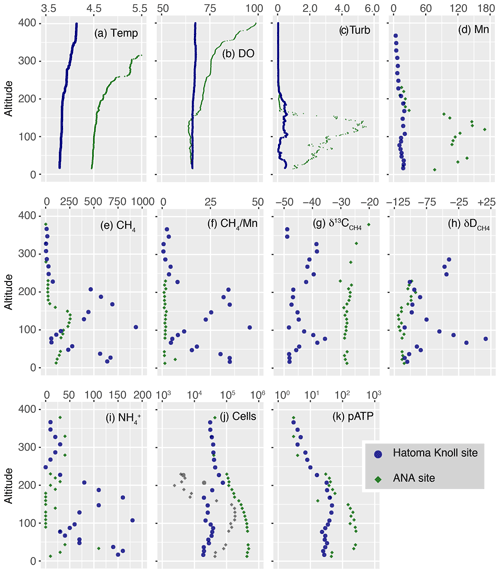

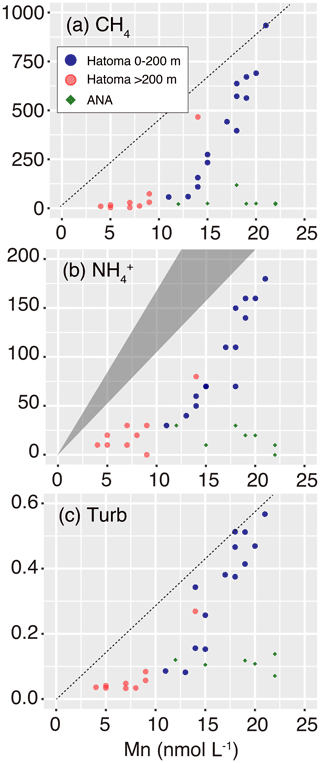

Vertical profiles of biogeochemical parameters drawn by altitude from the seafloor are presented in Fig. 2, and with all data provided as Table S1. Temperatures of seawater collected ranged between 3.5 and 7.0 ∘C (Fig. 2a). Water columns showed simultaneous increases in turbidity, manganese, and CH4 and demonstrated the presence of hydrothermal plumes above both the Hatoma Knoll and ANA sites. Temperature changes (from the bottom water temperature) fluctuated at both sites along the vertical profile, with no clearly identifiable peaks. Dissolved oxygen profiles at both sites demonstrated sufficiently oxic seawater for aerobic metabolisms through the water column observed. The turbidity profile above Hatoma Knoll exhibited two vertically broad turbid water masses, one near the seafloor and another at 100–200 m altitude. At the ANA station the turbidity profile displayed a single peak centered around 130 m altitude. The maximum turbidity seen above Hatoma Knoll was an order of magnitude lower (0.6 FTU) than at the ANA site. Drastic change in temperature and decline of turbidity above 200 m altitude in the Hatoma Knoll plume suggests the height of the caldera rim. Vertical patterns of manganese concentrations at each station were generally similar to turbidity. The maximum manganese concentrations observed were lower at Hatoma Knoll (21 nM) than the ANA site (119 nM).

Figure 2Vertical profiles of measured parameters. The y axis represents altitude from the seafloor at each site. (a) Temperature. (b) DO level (µmol kg−1). (c) Turbidity (FTU). (d–e) Manganese and CH4 concentrations (nmol L−1). (f) Methane manganese ratio. (g–h) Carbon and hydrogen isotope ratios of CH4 (‰). (i) Concentrations of ammonium (nmol kg−1). (j) Total cell density (colored) as well as HSS (grey) with logarithmic x axis (cells mL−1). (k) pATP concentration (pmol L−1).

Vertical distribution of CH4 concentrations also showed similar patterns to those of turbidity and manganese, but they differed from them in that the maximum CH4 concentrations observed were clearly higher at Hatoma Knoll (935 nM) compared to ANA (254 nM). The ratios varied between 1 and 45 above Hatoma Knoll but were roughly constant around 1.5 in the water column above ANA. Ammonium was more enriched in the water column above Hatoma Knoll compared to the ANA site. The vertical pattern of ammonium concentrations above Hatoma was similar to that of CH4 concentrations.

3.2 Methane isotope composition

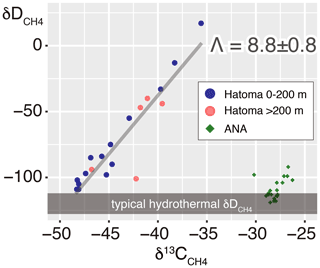

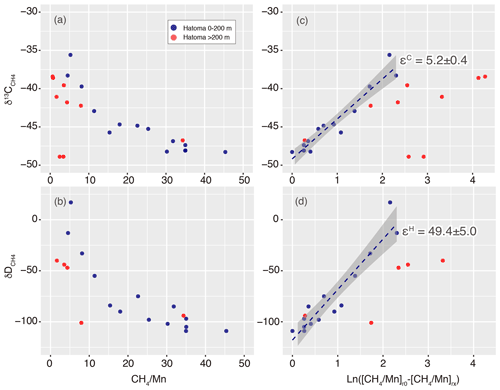

Carbon and hydrogen isotope ratios of CH4 were distinct between the two vent sites (Figs. 2 and 3). Above Hatoma Knoll, vertical patterns of CH4 concentrations and the δ13C values were mirror images of each other, with the δ13C values being the lowest (approximately −47 ‰) at 107 m altitude where the CH4 concentrations were high, while the highest δ13C value (−35.6 ‰) appeared at 77 m altitude where there was a minimum in CH4 concentrations. The vertical pattern of δD values above Hatoma was similar to that of the δ13C value, peaking at 77 m altitude with +17 ‰. Above the ANA site, however, the δ13C and δD values were almost constant across the depth gradient at −28 ‰ and −110 ‰, respectively.

The 13C–D diagram for CH4 observed above Hatoma Knoll demonstrated a linear trend (Fig. 3). Isotopic composition of the low-δ13C root of the linear distribution is consistent with the δ13C values of Hatoma vent fluids determined by direct sampling (−54 ‰ to −49 ‰) (Toki et al., 2016), and the δD values determined from all known deep-sea vent fluids (approximately −120 ‰) (Proskurowski et al., 2006). A least-square linear fitting for the dataset obtained above Hatoma Knoll yielded a slope of 8.8 (Fig. 3), which corresponds to Λ according to Eq. (4).

3.3 Microbiological characteristics

Total cell density (cells mL−1) above Hatoma Knoll generally fell within a narrow range between 1.9–7.6 × 104 across the depth gradient (Fig. 2j). The cytogram obtained from cell counting using flow cytometry exhibited two clusters, each of which represented the typical microbial cells and cells with typical fluorescence signals with significantly higher side-scatter signals, named the high-side-scatter population (HSS). The HSS is attributable to large cells and/or cell aggregates. Only two samples between 200–230 m showed significant HSS cell abundances at Hatoma Knoll. At the ANA site, the total cell density below 250 m altitude was an order of magnitude higher ( cells mL−1) than that above 250 m (4.0×104 cells mL−1). Between 40–160 m altitude, HSS cells occupied 20 %–58 % of the total cells. The cell densities in these samples are possibly underestimated because a HSS signal possibly consists of aggregated cells.

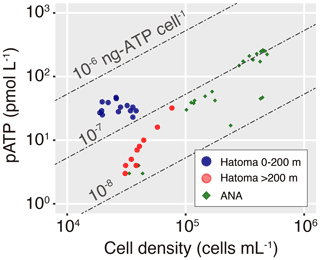

pATP concentrations above Hatoma Knoll increased with depth and were nearly constant below 200 m (the height of the caldera rim) at an order of 101 pmol L−1 (Fig. 2k). Above the ANA site, pATP concentrations were the highest between 33–140 m altitude at 3.0×102 pmol L−1. pATP concentrations above 250 m altitude were comparable between the two vent sites on the order of 100.

Cellular ATP contents (ng of ATP per cell) below 10−7 were observed above 300 m altitude at both the Hatoma Knoll and ANA sites (Fig. 4). The level observed is consistent with values previously reported from open ocean water (e.g., Winn and Karl, 1986), suggesting that they represent background levels without any effect from hydrothermal input. Gradual increase in the cellular ATP content along with increased depth was found from the caldera rim depth (200 m altitude) to the seafloor at Hatoma as well as across the depth gradient above the ANA site. Cellular ATP contents above 10−7 ng of ATP per cell, despite the low cell density (<105 cells mL−1), were observed below 200 m altitude at Hatoma Knoll.

Figure 313C–D diagram for CH4. Symbols of Hatoma Knoll samples are classified by color according to sampling altitudes below 200 m (blue) and above 200 m (pink). The grey diagonal line represents a linear fitting for the Hatoma Knoll dataset.

Figure 4A cross plot between pATP concentration and total cell density. Symbols are the same as those in Fig. 3. Dashed diagonal lines represent cellular ATP contents.

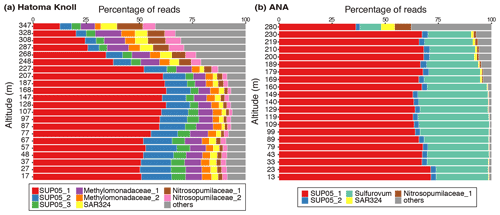

Figure 5Prokaryotic composition of (a) Hatoma Knoll plume and (b) ANA plume. The top 10 % (49 ASVs) of 4880 ASVs, in terms of total read abundance in this study, were defined as the major group. Read abundance of the major group corresponds to 83 % of the total read abundance of the samples. The names and colors in the legend are identical in these two panels.

Microbial community analysis using amplicon sequences of the 16S rRNA gene revealed distinct communities between the Hatoma Knoll and ANA sites (Fig. 5). In the water column from the seafloor to 200 m altitude above Hatoma, more than half of the community consisted of members of SUP05 (composed of three ASVs: SUP05_1, _2, and _3), a well-known group of chemolithotrophic sulfur-oxidizing Gammaproteobacteria frequently detected around hydrothermal vents and within hydrothermal plumes (Dick et al., 2013). Approximately 10 % of the community was occupied by the aerobic methanotrophic Gammaproteobacteria family Methylococcaceae (composed of two ASVs: Methylococcaceae_1 and _2) and >5 % by the ammonium-oxidizing archaeal family Nitrosopumilaceae (composed of two ASVs: Nitrosopumilaceae_1 and _2). Occupancies of SUP05 decreased with increasing altitude from the 200 m mark. The microbial community in the water column above ANA consisted of over 50 % SUP05 (composed of three ASVs: SUP05_1 and _2) and 19 % Sulfurovaceae (sulfur-oxidizing Epsilonproteobacteria family) from the seafloor to 250 m altitude. In contrast to Hatoma Knoll, methanotrophic lineages were not detected at the ANA site.

4.1 Active aerobic methanotrophy in Hatoma Knoll plume

Multiple lines of evidence point to the occurrence of microbial oxidation of CH4 in the hydrothermal plume above Hatoma Knoll, between the water column at the seafloor to 200 m altitude, but not at the ANA site. Manganese concentration has been utilized as an indicator for the dilution of Mn-rich hydrothermal vent fluid with Mn-depleted ambient seawater (e.g., Kawagucci et al., 2008), owing to the long life of manganese compared to particles and aerobically energetic molecules like CH4 (Kadko et al., 1990). In principle, a two-component mixing is represented by a straight line on the Mn plot, and a downward deviation from the ideal mixing line suggests significant removal of the counterpart compound (German and Seyfried, 2014). Indeed, the Mn plot of waters above Hatoma Knoll exhibited downward convex curves and not a straight line for CH4 concentrations, ammonium concentrations, and turbidity (Fig. 6). The NH4–Mn dataset of the Hatoma plume observed is shifted downwards from the ideal mixing line, assuming ratios of 11–18 observed in the Hatoma vent fluid (Toki et al., 2016), confirming the removal of ammonium from the plume. Despite the lack of available data for the estimated endmember fluid at the Hatoma Knoll vent site (Toki et al., 2016), the downward convex curve of CH4 concentrations on the Mn plot strongly suggests CH4 removal. From the viewpoint of microbial ecology, the ATP-rich microbial cells (Fig. 4) and the significant appearance of aerobic methanotrophic lineage (Fig. 5) observed in the plume above Hatoma Knoll are both strongly indicative of active microbial methanotrophy within the plume. In contrast, the rather uniform ratios above the ANA site regardless of concentrations suggest negligible CH4 consumption in the plume. No dominant methanotrophic microbial groups were detected by the 16S rRNA gene community analysis above ANA, supporting a lack of methanotrophic activity.

Figure 6Manganese plots with CH4 concentration, ammonium concentration, and turbidity. Symbols are the same as those in Fig. 3. The grey triangle in (b) represents the ideal mixing line between ambient seawater and the Hatoma vent fluid having ratios of 11–18. Diagonal dotted lines in (a) and (c) represent estimated mixing lines between ambient seawater and the hydrothermal plume source, assumed by the highest and turbidity Mn ratios observed.

The contrasting microbial community composition and methanotrophic activity seen between plumes above the Hatoma Knoll and ANA sites are likely attributable to differences in the vent fluid chemistry. High-temperature hydrothermal fluids directly collected from vent orifices at Hatoma Knoll showed relatively high CH4 concentrations sometimes >10 mM (Toki et al., 2016), in line with significant methanotrophic activity being detected in the Hatoma plume. In the plume originating from the CH4-rich Guaymas Basin site (McDermott et al., 2015), the presence of Methylococcaceae and the high expression of the methane oxidation gene (pmo) were revealed (Lesniewski et al., 2012). In contrast, high-temperature vent fluid collected from the ANA site only contained CH4 at concentrations below 1 mM (Makabe et al., 2016), which may explain the lack of significant methanotrophic activity in the plume above this site. The increase in total cell abundance (Fig. 2) and the dominance of the plume-associated sulfur-oxidizing bacteria group SUP05 (Fig. 5) (Sunamura et al., 2004) in the ANA plume are evidence for significant shifts of the entire microbial community supported by hydrothermal fluids. Although available CH4 likely fuels the methanotrophs, the low concentration only allows for slow methanotrophic activity compared to the residence time of the plume. This could make it difficult to detect signatures of methane consumption using concentrations and isotope ratios.

4.2 Determination of isotope fractionation factors at Hatoma Knoll

Hereafter, we assume the ratios of the plume above Hatoma vary only by aerobic CH4 oxidation, for the evaluation of isotope fractionation factors. When the δ13C and δD values of the Hatoma Knoll plume are plotted as a function of the ratio, there are observable increments of δ values along decrements of the ratio (Fig. 7). This phenomenon is well explained by the kinetic isotope effect on aerobic CH4 oxidation which causes the enrichment of heavier isotopologues, 13CH4 and CH3D, in the remnant reactant. Some large scatters of the δ13C and δD values are seen, particularly at low ranges (e.g., <10) – these data include two distinct seawater masses below 200 m altitude (the height of the caldera wall), corresponding to the high pATP water inside the caldera (Fig. 2) and waters coming in from above 200 m (Fig. 1). As our aim is to determine the isotope fractionation factors from the observed values, the gradual changes in isotope composition within the water mass below 200 m altitude were used for further analysis.

Figure 7Isotope ratio changes along with aerobic methanotrophy above Hatoma Knoll. Panels (a)–(b) show ratios while (c)–(d) represent Eq. (5) in the main text. Dashed lines and grey zones illustrated in (c)–(d) represent fitting lines with standard errors corresponding to isotope fractionation factors of the εC and εH values.

According to previous studies (e.g., Gamo et al., 2010), we applied the ratio instead of f for Eq. (2), as follows:

where a represents carbon (C) or hydrogen (H) isotopes. The plot analysis for the plume above Hatoma Knoll yielded slopes representing εC and εH values of 5.2±0.4 ‰ and 49.4±5.0 ‰, respectively (Fig. 7). The εC and εH values in turn yielded a Λ value of 9.4 according to Eq. (3). This ε-based Λ value calculated from the plume sample is similar to the δ-based Λ value calculated using the entire dataset from Hatoma Knoll (8.8) (Fig. 3).

The εH value of 49.4±5.0 ‰ determined is the first εH value reported for aerobic CH4 oxidation in oxic seawater. The εH value in the seawater column occupied by Methylococcaceae (49.4±5.0 ‰) is comparable with those determined by observations for terrestrial ecosystems (≥42 ‰) but clearly lower than those from aerobic and anaerobic methanotroph enrichment cultures (93 ‰–320 ‰) (e.g., Rasigraf et al., 2012; Ono et al., 2021) as well as incubations of methanotrophic isolates (110 ‰–232 ‰) (Feisthauer et al., 2011). Remarkably, the methanotrophic isolate Methylococcus capsulatus, a representative species of the family Methylococcaceae, exhibited εH values of 192 ‰ and 232 ‰ when cultivated at 45 ∘C with and without sufficient copper supply (Feisthauer et al., 2011).

The εC values obtained through observations of deep-sea hydrothermal plumes reported to date are comparable among the sites and regions, including the 27.5–32.5∘ S area on the East Pacific Rise (4 ‰–6 ‰) (Gharib, 2005), the Myojin Knoll field on the Izu-Ogasawara Arc (5±1) (Tsunogai et al., 2000), the Daiyon-Yonaguni site in the Okinawa Trough (5 ‰ and 12 ‰) (Gamo et al., 2010), Izena Hole also in the Okinawa Trough (<7 ‰) (Kawagucci et al., 2010), and Hatoma Knoll (5.2±0.4 ‰) (this study). These εC values from the deep-sea plumes are lower than those estimated from methanotrophic isolate incubations (18.8 ‰–27.9 ‰) and methanotrophic communities (7.9 ‰–26.6 ‰) when not considering some exceptional values (e.g., Feisthauer et al., 2011). Regardless of the εH and εC values, the Λ value of the hydrothermal plume (9.4 and 8.8) reported herein is consistent with those from methanotrophic isolate incubations (7.3–10.5), including the cultivation of M. capsulatus (Feisthauer et al., 2011). The consistencies in both εC values among deep-sea plumes and Λ values among isolates and plumes suggest that the εH, εC, and Λ values determined in this study are appropriate. However, the reasons why the εH and εC values are smaller in the natural environment including deep-sea water columns compared to others remain unclear at this point. Although temperature dependency of isotope fractionation factors on the methanotrophy was discussed (Chanton et al., 2008), the small ε values at 4 ∘C obtained in this study oppose the trend reported so far. A possible explanation, originally proposed for the case of benzene biodegradation (Fischer et al., 2009), is that the cells take up only a limited amount of methane, which is then virtually all consumed, leading to little change in the isotopic ratios of water column methane. Future applications of the approach to the other marine habitats with methanotrophic activity will reveal whether or not the small εH value observed here is ubiquitous in the marine realm.

The εH, εC, and Λ values associated with aerobic CH4 oxidation in seawater above hydrothermally active areas are useful for understanding marine CH4 dynamics. The δD values of seafloor hydrothermal vent fluids and hydrocarbon seep fluids are expected to be −130 ‰ and −180 ‰, respectively (Whiticar, 1986; Okumura et al., 2016). As such, observations of the δD values in the water column above the geofluid sites, combined with the εH value of 49.4±5.0, enable us to estimate how CH4 oxidation has progressed through Eq. (2). The estimation of the fraction as well as the δ13C values of vent plumes further allow us to estimate the δ13C value of the endmember effluent CH4. The estimated δ13C value of the endmember geofluid denotes the origin of CH4 there, allowing “sneak peeks” of the ongoing subseafloor process.

Our approach to determine isotope fractionation factors in the seawater column environment by high-resolution hydrothermal plume sampling can be applied not only to conventional carbon and hydrogen isotope ratios of CH4 but also to “clumped” isotope composition of CH4 (Wang et al., 2016; Ono et al., 2021). The same approach at Hatoma Knoll is also applicable to determining isotope fractionation factors for ammonium oxidation in marine environment because of the decreases in ratios (Fig. 6) and significant appearance of the ammonium-oxidizing archaeal family Nitrosopumilaceae (Fig. 5). If the focus was on sulfur isotope fractionation of aerobic sulfide oxidation, then the same approach at the ANA site would be appropriate because sulfur-oxidizing microbes dominated the microbial community (Fig. 5). Drastic changes in N2O and H2 concentrations in plumes at the Izena Cauldron (Kawagucci et al., 2010) also allow us to determine the isotope fractionation factors associated with their metabolisms in the water column by the same approach. These are foci in future studies.

The dataset reported is available in Table S1 in the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-18-5351-2021-supplement.

SK and TY designed the study. YM, AM, TF, YO, TN, and TY conducted chemical and microbiological analyses. SK made a draft. All authors contributed to sampling and gave final approval for submission and publication.

The contact author has declared that neither they nor their co-authors have any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

First of all, our biggest thanks go to Keiko Tanaka for her earnestness in the room Deep301. Manganese analyses were supported by Kaiyo Keisoku Co. Ltd. (president: Kei Okamura). The authors thank Hiroyuki Yamamoto, the master, crews, and scientific parties including MWJ and NME staffs of the R/V Mirai cruise (MR17-03C) for their support. The authors also thank Masami Koizumi, Miho Hirai, and Yoshihiro Takaki for assisting with microbiological analyses. Chong Chen proofread an earlier version of the paper to improve the English. This study was supported by the Council for Science, Technology, and Innovation (CSTI) as the Cross Ministerial Strategic Innovation Promotion Program (SIP), Next-generation Technology for Ocean Resource Exploration. We thank All Nippon Airways (ANA) for providing a comfortable flight to Okinawa Island, from where we embarked on the cruise to the ANA site (and Hatoma Knoll).

This research has been supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grant nos. 17H01869 and 20H02020).

This paper was edited by Jack Middelburg and reviewed by Carsten Vogt and one anonymous referee.

Affek, H. P. and Eiler, J. M.: Abundance of mass 47 CO2 in urban air, car exhaust, and human breath, Geochim. Cosmochi. Ac., 70, 1–12, 2006.

Blair, N. E., Martens, C. S., and DesMarais, D. J.: Natural Abundances of carbon isotopes in acetate from a coastal marine sediment, Science, 236, 66–68, 1987.

Bokulich, N. A., Kaehler, B. D., Rideout, J. R., Dillon, M., Bolyen, E., Knight, R., Huttley, G. A., and Caporaso, G. J.: Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2's q2-feature-classifier plugin, Microbiome, 6, 90, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z, 2018.

Bolyen, E., Rideout, J. R., Dillon, M. R., Bokulich, N. A., Abnet, C. C., Al-Ghalith, G. A., Alexander, H., Alm, E. J., Arumugam, M., Asnicar, F., Bai, Y., Bisanz, J. E., Bittinger, K., Brejnrod, A., Brislawn, C. J., Brown, C. T., Callahan, B. J., Caraballo-Rodríguez, A. M., Chase, J., Cope, E. K., Da Silva, R., Diener, C., Dorrestein, P. C., Douglas, G. M., Durall, D. M., Duvallet, C., Edwardson, C. F., Ernst, M., Estaki, M., Fouquier, J., Gauglitz, J. M., Gibbons, S. M., Gibson, D. L., Gonzalez, A., Gorlick, K., Guo, J., Hillmann, B., Holmes, S., Holste, H., Huttenhower, C., Huttley, G. A., Janssen, S., Jarmusch, A. K., Jiang, L., Kaehler, B. D., Kang, K. B., Keefe, C. R., Keim, P., Kelley, S. T., Knights, D., Koester, I., Kosciolek, T., Kreps, J., Langille, M. G. I., Lee, J., Ley, R., Liu, Y.-X., Loftfield, E., Lozupone, C., Maher, M., Marotz, C., Martin, B. D., McDonald, D., McIver, L. J., Melnik, A. V., Metcalf, J. L., Morgan, S. C., Morton, J. T., Naimey, A. T., Navas-Molina, J. A., Nothias, L. F., Orchanian, S. B., Pearson, T., Peoples, S. L., Petras, D., Preuss, M. L., Pruesse, E., Rasmussen, L. B., Rivers, A., Robeson, M. S., Rosenthal, P., Segata, N., Shaffer, M., Shiffer, A., Sinha, R., Song, S. J., Spear, J. R., Swafford, A. D., Thompson, L. R., Torres, P. J., Trinh, P., Tripathi, A., Turnbaugh, P. J., Ul-Hasan, S., van der Hooft, J. J. J., Vargas, F., Vázquez-Baeza, Y., Vogtmann, E., von Hippel, M., Walters, W., Wan, Y., Wang, M., Warren, J., Weber, K. C., Williamson, C. H. D., Willis, A. D., Xu, Z. Z., Zaneveld, J. R., Zhang, Y., Zhu, Q., Knight, R., and Caporaso, J. G.: Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2, Nat. Biotechnol., 37, 852–857, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9, 2019.

Brisbin, M. M., Conover, A. E., and Mitarai, S.: Influence of Regional Oceanography and Hydrothermal Activity on Protist Diversity and Community Structure in the Okinawa Trough, Microbial. Ecol., 80, 746–761, 2020.

Brussaard, C. P. D.: Optimization of procedures for counting viruses by flow cytometry, Appl. Environ. Microb., 70, 1506–1513, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.70.3.1506-1513.2004, 2004.

Casciotti, K. L.: Nitrite isotopes as tracers of marine N cycle processes, Philos. T. R. Soc. A, 374, 20150295-20, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2015.0295, 2016.

Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J., Rosen, M. J., Han, A. W., Johnson, A. J. A., and Holmes, S. P.: DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data, Nat. Methods, 13, 581–583, 2016.

Chanton, J. P., Powelson, D. K., Abichou, T., Fields, D., and Green, R.: Effect of Temperature and Oxidation Rate on Carbon-isotope Fractionation during Methane Oxidation by Landfill Cover Materials, Environ. Sci. Technol., 42, 7818–7823, 2008.

Coleman, D. D., Risatti, J. B., and Schoell, M.: Fractionation of carbon and hydrogen isotopes by methane-oxidizing bacteria, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 45, 1033–1037, 1981.

Dean, J. F., Middelburg, J. J., Röckmann, T., Aerts, R., Blauw, L. G., Egger, M., Jetten, M. S. M., Jong, A. E. E., Meisel, O. H., Rasigraf, O., Slomp, C. P., Zandt, M. H., and Dolman, A. J.: Methane Feedbacks to the Global Climate System in a Warmer World, Rev. Geophys., 56, 207–250, 2018.

Del Giorgio, P., Bird, D. F., Prairie, Y. T., and Planas, D.: Flow cytometric determination of bacterial abundance in lake plankton with the green nucleic acid stain SYTO 13, Limnol. Oceanogr., 41, 783–789, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1996.41.4.0783, 1996.

Dick, G. J., Anantharaman, K., Baker, B. J., Li, M., Reed D. C., and Sheik C. S.: The microbiology of deep-sea hydrothermal vent plumes: ecological and biogeographic linkages to seafloor and water column habitats, Front Microbiol., 4, 124, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2013.00124, 2013.

Elsner, M.: Stable isotope fractionation to investigate natural transformation mechanisms of organic contaminants: principles, prospects and limitations, J. Environ. Monitor., 12, 2005–2031, https://doi.org/10.1039/c0em00277a, 2010.

Farquhar, J., Savarino, J., Jackson, T. L., and Thiemens, M. H.: Evidence of atmospheric sulphur in the martian regolith from sulphur isotopes in meteorites, Nature, 404, 50–52, 2000.

Feisthauer, S., Vogt, C., Modrzynski, J., Szlenkier, M., Krüger, M., Siegert, M., and Richnow, H.-H.: Different types of methane monooxygenases produce similar carbon and hydrogen isotope fractionation patterns during methane oxidation, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 75, 1173–1184, 2011.

Fischer, A., Gehre, M., Breitfeld, J., Richnow, H., and Vogt, C.: Carbon and hydrogen isotope fractionation of benzene during biodegradation under sulfate-reducing conditions: a laboratory to field site approach, Rapid Commun. Mass Sp., 23, 2439–2447, 2009.

Gamo, T., Tsunogai, U., Ichibayashi, S., Chiba, H., Obata, H., Oomori, T., Noguchi, T., Baker, E. T., Doi, T., Maruo, M., and Sano, Y.: Microbial carbon isotope fractionation to produce extraordinarily heavy methane in aging hydrothermal plumes over the southwestern Okinawa Trough, Geochem. J., 44, 477–487, 2010.

German, C. R. and Seyfried, W. E.: 8.7 Hydrothermal Processes, 2nd Edn., Elsevier Ltd., 2014.

Gharib, J. J.: Methane dynamics in hydrothermal plumes over a superfast spreading center: East Pacific Rise, 27.5∘–32.3∘ S, J. Geophys. Res., 110, B10101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JB003531, 2005.

Ghosh, P., Adkins, J., Affek, H., Balta, B., Guo, W., Schauble, E. A., Schrag, D., and Eiler, J. M.: 13C–18O bonds in carbonate minerals: A new kind of paleothermometer, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 70, 1439–1456, 2006.

Hirai, M., Nishi, S., Tsuda, M., Sunamura, M., Takaki, Y., and Nunoura T.: Library Construction from Subnanogram DNA for Pelagic Sea Water and Deep-Sea Sediments, Microbes Environ., 32, 336–343, 2017.

Hiraoka, S., Hirai, M., Matsui, Y., Makabe, A., Minegishi, H., Tsuda, M., Eugenio Rastelli, J., Danovaro, R., Corinaldesi, C., Kitahashi, T., Tasumi, E., Nishizawa, M., Takai, K., Nomaki, H., and Nunoura, T.: Microbial community and geochemical analyses of trans-trench sediments for understanding the roles of hadal environments, ISME J., 14, 740–756, 2020.

Hirota, A., Tsunogai, U., Komatsu, D. D., and Nakagawa, F.: Simultaneous determination of δ15N and δ18O of N2O and δ13C of CH4 in nanomolar quantities from a single water sample, Rapid Commun. Mass Sp., 24, 1085–1092, 2010.

Holler, T., Wegener, G., Knittel, K., Boetius, A., Brunner, B., Kuypers, M. M. M., and Widdel, F.: Substantial 13C/12C and D/H fractionation during anaerobic oxidation of methane by marine consortia enriched in vitro, Env. Microbiol. Rep., 1, 370–376, 2009.

Ijiri, A., Inagaki, F., Kubo, Y., Adhikari, R. R., Hattori, S., Hoshino, T., Imachi, H., Kawagucci, S., Morono, Y., Ohtomo, Y., Ono, S., Sakai, S., Takai, K., Toki, T., Wang, D. T., Yoshinaga, M. Y., Arnold, G. L., Ashi, J., Case, D. H., Feseker, T., Hinrichs, K.-U., Ikegawa, Y., Ikehara, M., Kallmeyer, J., Kumagai, H., Lever, M. A., Morita, S., Nakamura, K., Nakamura, Y., Nishizawa, M., Orphan, V. J., Røy, H., Schmidt, F., Tani, A., Tanikawa, W., Terada, T., Tomaru, H., Tsuji, T., Tsunogai, U., Yamaguchi, Y. T., and Yoshida, N.: Deep-biosphere methane production stimulated by geofluids in the Nankai accretionary complex, Sci. Adv., 4, eaao4631, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aao4631, 2018.

Ishibashi, J., Wakita, H., Okamura, K., Nakayama, E., Feely, R. A., Lebon, G. T., Baker, E. T., and Marumo, K.: Hydrothermal methane and manganese variation in the plume over the superfast-spreading southern East Pacific Rise, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 61, 485–500, 1997.

Kadko, D. C., Rosenberg, N. D., Lupton, J. E., Collier, R. W., and Lilley, M. D.: Chemical reaction rates and entrainment within the Endeavour Ridge hydrothermal plume, Earth Planet Sc. Lett., 99, 315–335, 1990.

Kawagucci, S., Okamura, K., Kiyota, K., Tsunogai, U., Sano, Y., Tamaki, K., and Gamo, T.: Methane, manganese, and helium-3 in newly discovered hydrothermal plumes over the Central Indian Ridge, 18∘–20∘ S, Geochem. Geophy. Geosy., 9, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008gc002082, 2008.

Kawagucci S., Shirai K., Lan T. F., Takahata N., Tsunogai U., Sano Y. and Gamo T.: Gas geochemical characteristics of hydrothermal plumes at the HAKUREI and JADE vent sites, the Izena Cauldron, Okinawa Trough. Geochem J 44, 507–518, 2010.

Kawagucci, S., Makabe, A., Kodama, T., Matsui, Y., Yoshikawa, C., Ono, E., Wakita, M., Nunoura, T., Uchida, H., and Yokokawa, T.: Hadal water biogeochemistry over the Izu–Ogasawara Trench observed with a full-depth CTD-CMS, Ocean Sci., 14, 575–588, https://doi.org/10.5194/os-14-575-2018, 2018.

Kessler, J. D., Reeburgh, W. S., and Tyler, S. C.: Controls on methane concentration and stable isotope (δ2H-CH4 and δ13C-CH4) distributions in the water columns of the Black Sea and Cariaco Basin, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 20, GB4004, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GB002571, 2006.

Kinnaman, F. S., Valentine, D. L., and Tyler, S. C.: Carbon and hydrogen isotope fractionation associated with the aerobic microbial oxidation of methane, ethane, propane and butane, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 71, 271–283, 2007.

Konno, U., Takai, K., and Kawagucci, S.: Stable chlorine isotope ratio analysis of subnanomolar level methyl chloride by continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometry, Geochem. J., 47, 469–473, https://doi.org/10.2343/geochemj.2.0264, 2013.

Lesniewski, R. A., Jain, S., Anantharaman, K., Schloss, P. D., and Dick, G. J.: The metatranscriptome of a deep-sea hydrothermal plume is dominated by water column methanotrophs and lithotrophs, ISME J., 6, 2257–2268, 2012.

Makabe, A., Tsutsumi, S., Chen, C., Torimoto, J., Matsui, Y., Shibuya, T., Miyazaki, J., Kitada, K., and Kawagucci, S.: Discovery of New Hydrothermal Vent Fields in the Mid- and southern-Okinawa Trough, Goldschmidt Abstracts, 1945, 2016.

Mariotti, A., Germon, J. C., Hubert, P., Kaiser, P., Letolle, R., Tardieux, A., and Tardieux, P.: Experimental determination of nitrogen kinetic isotope fractionation: Some principles; illustration for the denitrification and nitrification processes, Plant Soil, 62, 413–430, 1981.

Martin, M.: Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads, EMBnet Journal, 17, 10–12, 2011.

McDermott, J. M., Ono, S., Tivey, M. K., Seewald, J. S., Shanks III, W. C., and Solow, A. R.: Identification of sulfur sources and isotopic equilibria in submarine hot-springs using multiple sulfur isotopes, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 160, 169–187, 2015.

Michalski, G., Scott, Z., Kabiling, M., and Thiemens, M. H.: First measurements and modeling of Δ17O in atmospheric nitrate, Geophys. Res. Lett., 30, 1870, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL017015, 2003.

Nadalig, T., Greule, M., Bringel, F., Vuilleumier, S., and Keppler, F.: Hydrogen and carbon isotope fractionation during degradation of chloromethane by methylotrophic bacteria, Microbiologyopen, 2, 893–900, 2013.

Nakamura, K., Kawagucci, S., Kitada, K., Kumagai, H., Takai, K., and Okino, K.: Water column imaging with multibeam echo-sounding in the mid-Okinawa Trough: Implications for distribution of deep-sea hydrothermal vent sites and the cause of acoustic water column anomaly, Geochem. J., 49, 579–596, 2015.

Nunoura, T., Takaki, Y., Kazama, H., Hirai, M., Ashi, J., Imachi, H., and Takai, K.: Microbial Diversity in Deep-sea Methane Seep Sediments Presented by SSU rRNA Gene Tag Sequencing, Microbes Environ., 27, 382–390, 2012.

Ohkouchi, N., Tayasu, I., and Koba, K. (Eds.): Earth, life, and isotopes, Kyoto University Press, Kyoto, 2010.

Okumura, T., Kawagucci, S., Saito, Y., Matsui, Y., Takai, K., and Imachi, H.: Hydrogen and carbon isotope systematics in hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis under H2-limited and H2-enriched conditions: implications for the origin of methane and its isotopic diagnosis, Prog. Earth Planet. Sc., 3, 219, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-016-0088-3, 2016.

Ono, S., Rhim, J. H., Gruen, D. S., Taubner, H., Kölling, M., and Wegener, G.: Clumped isotopologue fractionation by microbial cultures performing the anaerobic oxidation of methane, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 293, 70–85, 2021.

Proskurowski, G., Lilley, M. D., Kelley, D. S., and Olson, E. J.: Low temperature volatile production at the Lost City Hydrothermal Field, evidence from a hydrogen stable isotope geothermometer, Chem. Geol., 229, 331–343, 2006.

Quast, C., Pruesse, E., Yilmaz, P., Gerken, J., Schweer, T., Yarza, P., Peplies, J., and Glöckner, F. O.: The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools, Nucleic Acids Res., 41, D590–D596, 2013.

Rasigraf, O., Vogt, C., Richnow, H.-H., Jetten, M. S. M., and Ettwig, K. F.: Carbon and hydrogen isotope fractionation during nitrite-dependent anaerobic methane oxidation by Methylomirabilis oxyfera, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 89, 256–264, 2012.

Reeburgh, W. S.: Oceanic Methane Biogeochemistry, Chem. Rev., 107, 486–513, 2007.

Saunois, M., Stavert, A. R., Poulter, B., Bousquet, P., Canadell, J. G., Jackson, R. B., Raymond, P. A., Dlugokencky, E. J., Houweling, S., Patra, P. K., Ciais, P., Arora, V. K., Bastviken, D., Bergamaschi, P., Blake, D. R., Brailsford, G., Bruhwiler, L., Carlson, K. M., Carrol, M., Castaldi, S., Chandra, N., Crevoisier, C., Crill, P. M., Covey, K., Curry, C. L., Etiope, G., Frankenberg, C., Gedney, N., Hegglin, M. I., Höglund-Isaksson, L., Hugelius, G., Ishizawa, M., Ito, A., Janssens-Maenhout, G., Jensen, K. M., Joos, F., Kleinen, T., Krummel, P. B., Langenfelds, R. L., Laruelle, G. G., Liu, L., Machida, T., Maksyutov, S., McDonald, K. C., McNorton, J., Miller, P. A., Melton, J. R., Morino, I., Müller, J., Murguia-Flores, F., Naik, V., Niwa, Y., Noce, S., O'Doherty, S., Parker, R. J., Peng, C., Peng, S., Peters, G. P., Prigent, C., Prinn, R., Ramonet, M., Regnier, P., Riley, W. J., Rosentreter, J. A., Segers, A., Simpson, I. J., Shi, H., Smith, S. J., Steele, L. P., Thornton, B. F., Tian, H., Tohjima, Y., Tubiello, F. N., Tsuruta, A., Viovy, N., Voulgarakis, A., Weber, T. S., van Weele, M., van der Werf, G. R., Weiss, R. F., Worthy, D., Wunch, D., Yin, Y., Yoshida, Y., Zhang, W., Zhang, Z., Zhao, Y., Zheng, B., Zhu, Q., Zhu, Q., and Zhuang, Q.: The Global Methane Budget 2000–2017, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 12, 1561–1623, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-1561-2020, 2020.

Sharp, Z.: Principles of stable isotope geochemistry, 2nd Edn., University of New Mexico Digital Repository, https://doi.org/10.25844/h9q1-0p82, 2017.

Snover, A. K. and Quay, P. D.: Hydrogen and carbon kinetic isotope effects during soil uptake of atmospheric methane, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 14, 25–39, 2000.

Sugimoto, A. and Wada, E.: Hydrogen isotopic composition of bacterial methane: CO2/H2 reduction and acetate fermentation, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 59, 1329–1337, 1995.

Sunamura, M., Higashi, Y., Miyako, C., Ishibashi, J., and Maruyama, A.: Two Bacteria Phylotypes Are Predominant in the Suiyo Seamount Hydrothermal Plume, Appl. Environ. Microb., 70, 1190–1198, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.70.2.1190-1198.2004, 2004.

Toki, T., Itoh, M., Iwata, D., Ohshima, S., Shinjo, R., Ishibashi, J.-I., Tsunogai, U., Takahata, N., Sano, Y., Yamanaka, T., Ijiri, A., Okabe, N., Gamo, T., Muramatsu, Y., Ueno, Y., Kawagucci, S., and Takai, K.: Geochemical characteristics of hydrothermal fluids at Hatoma Knoll in the southern Okinawa Trough, Geochem. J., 50, 493–525, 2016.

Tsunogai, U., Yoshida, N., Ishibashi, J., and Gamo, T.: Carbon isotopic distribution of methane in deep-sea hydrothermal plume, Myojin Knoll Caldera, Izu-Bonin arc: implications for microbial methane oxidation in the oceans and applications to heat flux estimation, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 64, 2439–2452, 2000.

Tsunogai, U., Miyoshi, Y., Matsushita, T., Komatsu, D. D., Ito, M., Sukigara, C., Nakagawa, F., and Maruo, M.: Dual stable isotope characterization of excess methane in oxic waters of a mesotrophic lake, Limnol. Oceanogr., 121, 2937–2952, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.11566, 2020.

Uyeno, D., Kakui, K., Watanabe, H. K., and Fujiwara, Y.: Dirivultidae (Copepoda: Siphonostomatoida) from hydrothermal vent fields in the Okinawa Trough, North Pacific Ocean, with description of one new species, J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK, 100, 1283–1298, 2020.

Valentine, D. L., Chidthaisong, A., Rice, A., Reeburgh, W. S., and Tyler, S. C.: Carbon and hydrogen isotope fractionation by moderately thermophilic methanogens, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 68, 1571–1590, 2004.

Vogt, C., Dorer, C., Musat, F., and Richnow, H.-H.: Multi-element isotope fractionation concepts to characterize the biodegradation of hydrocarbons – from enzymes to the environment, Curr. Opin. Biotech., 41, 90–98, 2016.

Wang, D. T., Welander, P. V., and Ono, S.: Fractionation of the methane isotopologues 13CH4, 12CH3D, and 13CH3D during aerobic oxidation of methane by Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath), Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 192, 186–202, 2016.

Watsuji, T., Yamamoto, A., Takaki, Y., Ueda, K., Kawagucci, S., and Takai, K.: Diversity and methane oxidation of active epibiotic methanotrophs on live Shinkaia crosnieri, ISME J., 8, 1020–1031, 2014.

Whiticar, M. J., Faber, E., and Schoell, M.: Biogenic methane formation in marine and freshwater environments: CO2 reduction vs. acetate fermentation – Isotope evidence, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 50, 693–709, 1986.

Winn, C. D. and Karl, D. M.: Diel nucleic acid synthesis and particulate DNA concentrations: Conflicts with division rate estimates by DNA accumulation, Limnol. Oceanogr., 31, 637–645, 1986.

Yoshida, N. and Toyoda, S.: Constraining the atmospheric N2O budget from intramolecular site preference in N2O isotopomers, Nature, 405, 330–334, 2000.

Zhang, J., Kobert, K., Flouri, T., and Stamatakis, A.: PEAR: a fast and accurate Illumina Paired-End reAd mergeR, Bioinformatics, 30, 614–620, 2014.