the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Growth rate rather than temperature affects the B∕Ca ratio in the calcareous red alga Lithothamnion corallioides

Giulia Piazza

Valentina A. Bracchi

Antonio Langone

Agostino N. Meroni

Daniela Basso

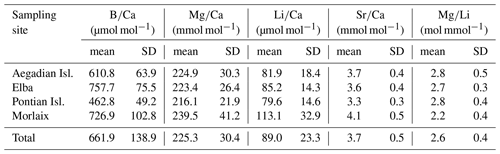

The ratio in calcareous marine species is informative of past seawater CO concentrations, but scarce data exist on in coralline algae. Recent studies suggest influences of temperature and growth rates on , the effect of which could be critical for the reconstructions of surface ocean pH and atmospheric pCO2. In this paper, we present the first laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) analyses of Mg, Sr, Li, and B in the coralline alga Lithothamnion corallioides collected from different geographic settings and depths across the Mediterranean Sea and in the Atlantic Ocean. We produced the first data on putative temperature proxies (, , , ) and in a coralline algal species grown in different basins from across the photic zone (12, 40, 45, and 66 m depth). We tested the correlation with temperature proxies and growth rates in order to evaluate their possible effect on B incorporation. Our results suggested a growth rate influence on , which was evident in the sample with the lowest growth rate of 0.10 mm yr−1 (Pontian Isl., Italy; 66 m depth) and in Elba (Italy; 45 m depth), where the algal growth rate was the highest (0.14 mm yr−1). At these two sites, the measured was the lowest at 462.8 ± 49.2 µmol mol−1 and the highest at 757.7 ± 75.5 µmol mol−1, respectively. A positive correlation between and temperature proxies was found only in the shallowest sample from Morlaix (Atlantic coast of France; 12 m depth), where the amplitude of temperature variation (ΔT) was the highest (8.9 ∘C). Still, fluctuations in did not mirror yearly seasonal temperature oscillations as for , , and . We concluded that growth rates, triggered by the different ΔT and light availability across depth, affect the B incorporation in L. corallioides.

- Article

(5749 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(833 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Warming and acidification are major anthropogenic perturbations of present-day oceans (Callendar, 1938; Fairhall, 1973; Brewer, 1997; Gattuso, 1999; Caldeira, 2005; Hönisch et al., 2012; Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021). Ocean acidification reduces the saturation state of calcite and aragonite, lowering the dissolution threshold of biominerals and threatening habitat-forming species of critical ecological importance such as coralline red algae and corals (Morse et al., 2006; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007; Andersson et al., 2008, 2011; Basso, 2012; Ragazzola et al., 2012; Ries et al., 2016). Coralline algae, which precipitate high-Mg calcite (>8 mol %–12 mol % MgCO3) (Morse et al., 2006), are particularly suitable as proxy archives for paleoclimate reconstruction because of their worldwide distribution and longevity. Importantly, they show indeterminate growth with no ontogenetic trend (Halfar et al., 2008), which means the growth trend of coralline algae does not slow down asymptotically with age, as in bivalves, thus preserving the resolution of the geochemical signals in all stages of growth (Adey, 1965; Frantz et al., 2005; Halfar et al., 2008). Moreover, coralline algae thin sections under optical microscopy reveal bands that reflect the growth pattern (Cabioch, 1966; Basso, 1995a, b; Foster, 2001), similar to tree rings (Ragazzola et al., 2016) that can be targeted for high-resolution geochemical analyses. Seasonal growth bands, indeed, consist of the perithallial alternation of dark and light bands that together constitute the annual growth patterns (Freiwald and Henrich, 1994; Basso, 1995a, b; Kamenos et al., 2009). Dark bands correspond to slow-growing cells produced in the cold season, which are shorter, thick-walled, and with lower Mg contents, while light bands are fast-growing cells produced in the warm season, which are longer, less calcified, and with higher Mg concentrations (Kamenos et al., 2009; Ragazzola et al., 2016). The high-Mg calcite of calcareous red algae records ambient seawater temperature (Halfar et al., 2000; Kamenos et al., 2008; Nash et al., 2016; Hetzinger er al., 2018), primary productivity (Chan et al., 2017; Hou et al., 2019), and salinity (Kamenos, 2012), proving to be a suitable paleoclimate archive. Most of the data were collected from high-latitude (Kamenos et al., 2008; Anagnostou et al., 2019) and tropical species (Caragnano et al., 2014; Darrenougue et al., 2014), whereas less attention has been given to coralline algae from mid-latitudes.

Trace element variations in marine calcareous species inform the reconstruction of changes in the environmental parameters which characterized the seawater during their growth (Hetzinger et al., 2011; Montagna and Douville, 2017). Boron is incorporated into the mineral lattice of calcareous marine species during calcite precipitation. In the ocean, B occurs in two molecular species: boric acid B(OH)3 and borate ion B(OH) (Dickson, 1990), which are related by the following acid–base equilibrium reaction:

which shows the dependence of the two species concentrations on pH. The first analyses of the isotopic signal of marine carbonates evidenced a strong similarity with the isotopic composition of B(OH) in solution, suggesting that borate would preferentially be incorporated into marine carbonates (Vengosh et al., 1991; Hemming and Hanson, 1992; Zeebe and Wolf-Gladrow, 2001; DeCarlo et al., 2018). The B content and its isotopic signature (δ11B) in calcareous marine species record information about the seawater carbonate system. The δ11B is used to reconstruct past seawater pH (Hönisch and Hemming, 2005; Foster, 2008; Douville et al., 2010; Paris et al., 2010; Rae et al., 2011). The boron-to-calcium ratio () proved to be informative about past seawater CO concentrations in different empirical studies on benthic foraminifera (Yu and Elderfield, 2007; Yu et al., 2007; Rae et al., 2011) and in synthetic aragonite (Holcomb et al., 2016). Most of the literature on boron studies is focused on its isotopic composition (Hemming and Hönisch, 2007; Klochko et al., 2009; Henehan et al., 2013; Fietzke et al., 2015; Cornwall et al., 2017; Ragazzola et al., 2020), whereas less attention has been given to records, especially in coralline algae. Recent studies suggest that is a function of seawater pH, as well as of other environmental variables such as temperature, the effect of which should be considered in the attempt to reconstruct surface ocean pH and atmospheric pCO2 (Wara et al., 2003; Allen et al., 2012; Kaczmarek et al., 2016).

To achieve the best reliability of geochemical proxies for climate reconstructions, it is important to recognize the influence of multiple factors on a single proxy (Kaczmarek et al., 2016; Donald et al., 2017). For instance, more recently the effects of temperature and growth rate on B incorporation have been investigated through experiments on both synthetic and biogenic carbonates (Wara et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2007; Gabitov et al., 2014; Mavromatis et al., 2015; Uchikawa et al., 2015; Kaczmarek et al., 2016; Donald et al., 2017). In particular, a culture experiment on the coralline alga Neogoniolithon sp. showed a positive correlation of with growth rate and a negative correlation with , which was proposed as a proxy for dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) (Donald et al., 2017). Moreover, a culture experiment on the high-latitude species Clathromorphum compactum (Kjellman) Foslie 1898 revealed non-significant temperature influences on and a significant inverse relationship with growth rate (Anagnostou et al., 2019). The factors which influence the B incorporation in calcareous red algae are therefore still debated. Recent experiments also suggest that coralline algae can control the calcifying fluid pH (pHcf) (Cornwall et al., 2017), as already observed in corals (Comeau et al., 2017). Both organisms have a species-specific capability to elevate pH at calcification sites in response to variations of ambient pH, also influencing precipitation rates (Cornwall et al., 2017). Differences between carbonate polymorphs were also highlighted (McCulloch et al., 2012; Cornwall et al., 2018), showing more elevated pHcf in aragonitic corals than calcites, pointing to the relevance of the mineralogical control on biological up-regulation. So far, no investigations on pHcf modifications in natural systems have been performed on calcareous red algae.

No studies have been conducted so far on the correlation between temperature proxies (Mg, Sr, ) and . The ratio is extensively used as a temperature proxy in coralline algae (Halfar et al., 2008; Kamenos et al., 2008; Fietzke et al., 2015; Ragazzola et al., 2020), since the substitution of Mg2+ with Ca2+ ions in the calcite lattice is an endothermic reaction. Accordingly, Mg incorporation increases with temperature (Moberly, 1968; Berner, 1975; Ries, 2006; Caragnano et al., 2014, 2017). and ratios in calcareous red algae have also been investigated as climate proxies, showing significant positive correlations with temperature in different species (Kamenos et al., 2008; Hetzinger et al., 2011; Caragnano et al., 2014; Darrenougue et al., 2014). The ratio showed a strong correlation with seawater temperature in cultured C. compactum (Anagnostou et al., 2019) and in empirical studies on high-Mg calcites, including coralline algae (Stewart et al., 2020). Conversely, the calibration did not reveal improvements in the or proxies in Lithophyllum spp. (Caragnano et al., 2014, 2017).

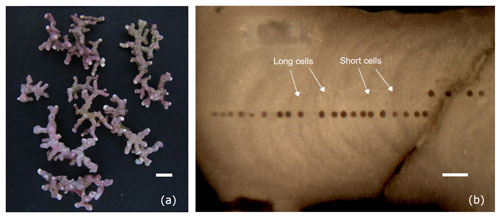

Here, we present laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) conducted on a wild-grown coralline alga with a wide geographic scope. This technique, which allows high-resolution analysis of a broad range of trace elements in solid-state samples, has been widely used in biogenic carbonates to extract records of seawater temperature, salinity, and water chemistry (Schöne et al., 2005; Corrège, 2006; Hetzinger et al., 2009, 2011; Fietzke et al., 2015; Ragazzola et al., 2020). Measurements were made on the non-geniculate coralline alga Lithothamnion corallioides (P. Crouan and H. Crouan) P. Crouan and H. Crouan 1867, which is widely distributed in the Mediterranean Sea and in the north-eastern Atlantic Ocean from Scotland to the Canary Islands (Irvine and Chamberlain, 1999; Wilson et al., 2004; Carro et al., 2014), usually constituting maerl beds (Potin et al., 1990; Foster, 2001; Martin et al., 2006; Savini et al., 2012; Basso et al., 2017). It forms rhodoliths as unattached branches (Basso et al., 2016) with obvious banding in longitudinal sections (Basso, 1995b). These characteristics combine to make this species a suitable model for the measurement of geochemical proxies by comparing different environmental settings.

In this paper, we provide the first LA-ICP-MS data on putative temperature proxies (, , , ) and measured on L. corallioides collected from different geographic settings and depths across the Mediterranean Sea and in the Atlantic Ocean. We test the influence of temperature and growth rate on the ratio, which could be crucial in assessing the reliability of as a proxy for the seawater carbonate system.

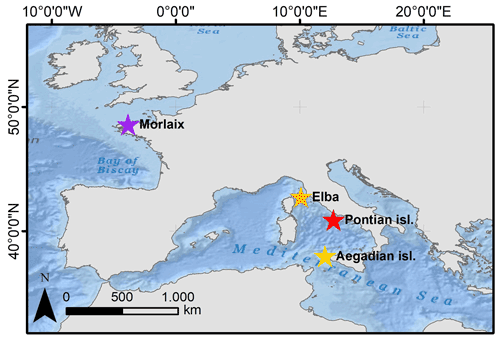

2.1 Sampling sites and collection of Lithothamnion corallioides

Samples of the coralline alga L. corallioides were collected in the western Mediterranean Sea and in the Atlantic Ocean (Fig. 1). In the Mediterranean Sea, the samples collected in the Pontian Islands (Italy) at 66 m depth were gathered by grab during the cruises of the R/V Minerva Uno in the framework of the Marine Strategy Campaigns 2016 (Table 1). The last two Mediterranean samples were collected by one of the authors (DB) by scuba diving during local surveys at 45 m off the coasts of Pomonte (Elba Island, Italy) (Basso and Brusoni, 2004) and at 40 m depth in the Aegadian Islands (Marettimo, Italy). The Atlantic sample was collected by grab at 12 m depth in Morlaix Bay (Brittany, France) (Table 1).

Figure 1Map showing the distribution of sampling sites where Lithothamnion corallioides samples were collected: Morlaix Bay (48∘34′42′′ N, 3∘49′36′′ W), Aegadian Islands (37∘97′36′′ N, 12∘14′12′′ E), Elba (42∘44′56.4′′ N, 10∘07′08.4′′ E), and Pontian Islands (40∘54′ N, 12∘45′ E). Service layer credits: source Esri, GEBCO, NOAA, National Geographic, Garmin, https://www.geonames.org/ (last access: 21 December 2021), and other contributors.

Figure 2(a) Thalli of Lithothamnion corallioides collected in Morlaix (scale bar: 5 mm). (b) Longitudinal section through the L. corallioides branch sampled in Morlaix showing the LA-ICP-MS transects targeting each growth band (scale bar: 200 µm).

The identification of the algal samples was achieved by morphological analyses of epithallial and perithallial cells using a field emission gun scanning electron microscope (SEM-FEG) Gemini 500 Zeiss. Samples were prepared for SEM according to Basso (1995a). Morphological identification was based on Adey and McKibbin (1970) and Irvine and Chamberlain (1994). Other information about maerl species distribution in Morlaix was provided by Carro et al. (2014) and Melbourne et al. (2017). L. corallioides was selected as the target species because of its presence in both Mediterranean and Atlantic waters. The Atlantic sample (Morlaix) was used as voucher specimen for the subsequent identification of the Mediterranean samples, since Phymatolithon spp. and L. corallioides are the only components of the Morlaix maerl (Carro et al., 2014; Melbourne et al., 2017). Hence, once its inclusion under the genus Phymatolithon was excluded, the Morlaix sample identified as L. corallioides was used as a reference for the most reliable identification of the other Mediterranean samples.

2.2 Sample preparation

The selected algal branches were embedded in Epo-Fix resin, which was stirred for 2 min with a hardener (13 % ); they were then left to dry at room temperature for 24 h. Afterwards, the treated branches were cut by an IsoMet diamond wafering blade 15HC along the direction of growth. In the laboratory of the Institute of Geosciences and Earth Resources of the National Research Council (IGG-CNR) in Pavia (Italy), the sections were polished with a MetaServ grinder–polisher (400 RPM) using a diamond paste solution, finally cleaned ultrasonically in distilled water for 10 min, and dried at 30 ∘C for 24 h.

2.3 Trace elements analyses and environmental data

LA-ICP-MS analyses were carried out at the IGG-CNR laboratory on one algal branch per sampling site. 43Ca, 7Li, 25Mg, 88Sr, and 11B contents were measured using an Agilent ICP-QQQ 8900 quadrupole ICP-MS coupled to an Excimer laser ablation system (193 nm wavelength, MicroLas with GeoLas optics). Element Ca ratios were calculated for these isotopes, as was the ratio. Measurements were performed with laser energy densities of 4 J cm−2 and helium as a carrier gas.

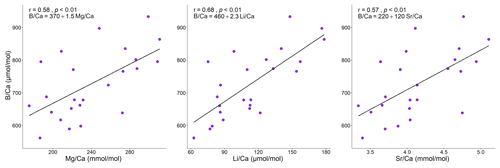

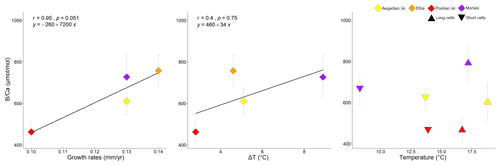

Figure 3Correlation plots of with and . For each analysis the Spearman's coefficient r, the p value, and the line equation are given.

The laser transects crossed the algal growth direction with a spot size of 50 µm, attempting to target each growth band change which marked the transition between the cells usually produced in the warm season and those usually produced in the cold season, hereinafter referred to as long and short cells (Figs. 2, S1, S2, S3). NIST 612 was used as an external standard (e.g. Fietzke et al., 2010; Jochum et al., 2012), whereas Ca was adopted as an internal standard. Accuracy and precision were better than 4 % for NIST 612 and 8 % for Ca standard. Minimum detection limits (99 % confidence) of measured elements were Ca = 16.91, Li = 0.07, Mg = 0.11, Sr = 0.004, and B = 2.64 ppm. Each analysis was carried out in MS/MS mode for 3 min by acquiring 60 s of background before and after the sampling period by the laser on the polished surface. The first part of the signal was not used for the integration to avoid surface contamination. The Glitter software (v. 4.4.4) was used for data reduction.

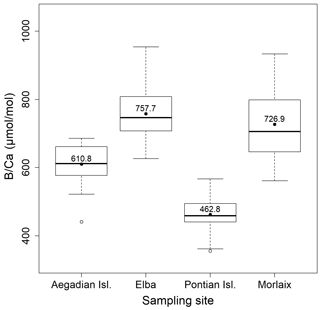

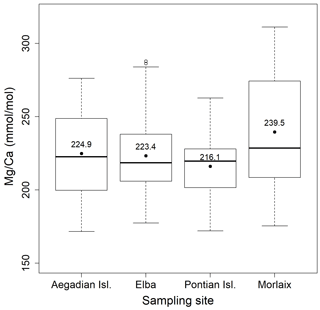

Figure 4Box plot of the statistical tests performed to evaluate the differences of in L. corallioides collected at different sampling sites. The horizontal black lines indicate the median values. The black dots and the numbers inside the plot indicate the mean values.

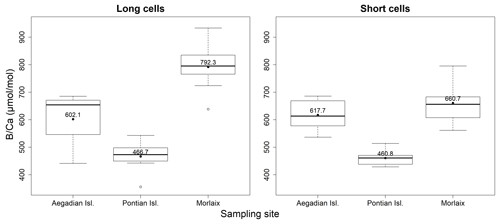

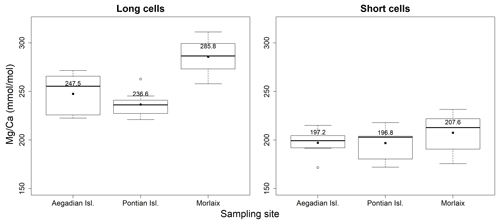

Figure 5Box plots of the statistical tests performed to evaluate the differences of in the long and short cells of L. corallioides collected at different sampling sites. The horizontal black lines indicate the median values. The black dots and the numbers inside the plot indicate the mean values.

In the absence of in situ environmental data, the seawater temperature has been extracted by 11 years of monthly reanalysis spanning 1979–2016 from from the Ocean ReAnalysis System 5 (ORAS5) at 0.25∘ horizontal resolution (Zuo et al., 2019). The time interval of extraction for each site corresponded to 11 years before sample collection (Bracchi et al., 2021). Minimum, maximum, and mean values, as reported in Table 1, refer to the temperature at sampling depth and have been measured over the entire time interval of extraction.

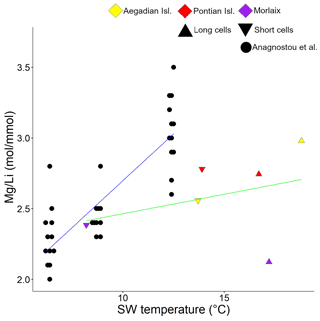

Figure 6Correlation plot between and seawater temperature. Data are shown for cultured C. compactum (Anagnostou et al., 2019) and L. corallioides (this paper). L. corallioides results are shown separately in long and short cells per sampling site.

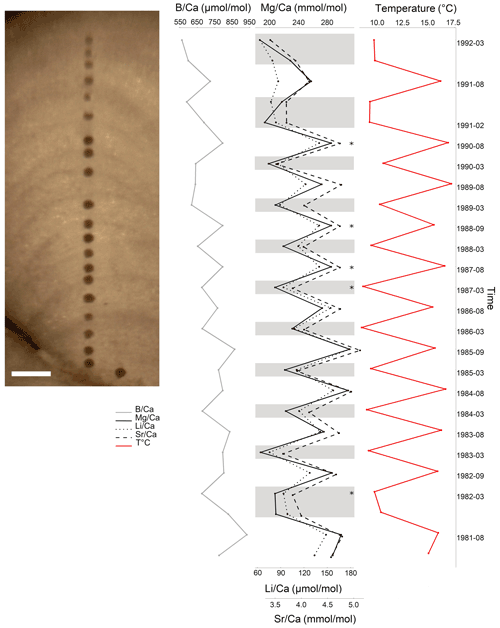

For the purpose of this work, we considered temperature data in terms of (a) the amplitude of temperature variation (ΔT) and (b) the temperature maxima and minima. ΔT represents the temperature fluctuations during the algal growth and has been measured as the difference between the maximum and minimum temperature registered at the site over 11 years. We used ΔT when comparing the sampling sites, given their differences in depth and geographical regions. The temperature peaks (maximum and minimum) have rather been used when considering data corresponding to long and short cells, since they are related to warm and cold periods of growth, respectively. We used the temperature peaks over the entire time interval of extraction (11 years) when comparing the mean elemental ratios of long and short cells per sampling site. The maximum and minimum temperature within each year have been used instead for the reconstruction of the algal age model. In the sample from Morlaix Bay, indeed, the good visibility of the growth bands allowed us to relate the temperature record with the algal growth at annual resolution. We therefore plotted all the element ratios against the average seawater temperature values of the coldest and warmest months of the year to reconstruct the temperature variations during the algal growth (Moberly, 1970; Corrège, 2006; Williams et al., 2014; Ragazzola et al., 2020; Caragnano et al., 2014). Missing element ratios, possibly due to non-targeted consecutive bands, were calculated as the means of known values.

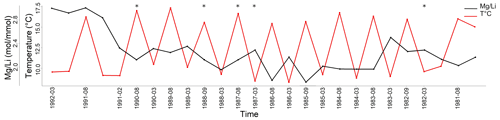

Figure 7 ratio of L. corallioides collected in Morlaix Bay. Note the lack of cyclic variations in results. In the timeline, the coldest and the warmest months have been reported. ratios in the missing bands (asterisks) have been calculated as the means of the values measured in warm and cold periods. Monthly means of seawater temperature have been extracted by ORAS5 reanalysis.

Carbon system parameters for each site have also been estimated. Even if they were not available in the same time interval of temperature data, the seasonal variations occurring in the extracted period allowed the characterization of the sampling sites. Monthly mean seawater pH has been derived by the EU Copernicus Marine Service Information (CMEMS) global biogeochemical hindcast spanning 1999–2017 at 0.25∘ horizontal resolution (Perruche, 2018). Monthly means of DIC in the time interval 1999–2017 have been extracted by CMEMS biogeochemical reanalysis for the Mediterranean Sea at 0.042∘ horizontal resolution (Teruzzi et al., 2021). At the Atlantic site, monthly means of DIC in 1999–2017 were derived from the CMEMS IBI biogeochemical model at 0.083∘ horizontal resolution (Copernicus Marine Environmental Monitoring Service, 2020). The pH and DIC data showed consistent variations among sites, despite being derived from different biogeochemical models. The mean values of DIC and pH, as reported in Table 1, refer to sampling depth and have been measured over the entire time interval of extraction. The complete timeline of temperature and carbon data used in this paper is shown in Supplement Figs. S5, S6, S7, and S8.

2.4 Growth rate estimation

Growth rates were estimated under light microscope by measuring the length of the LA-ICP-MS transect and dividing it by the number of annual growth bands crossed by the transect (Bracchi et al., 2021). The obtained values are expressed in linear extension per year (mm yr−1). In the samples wherein the growth bands were not easily detectable under microscope, i.e. the Elba sample, we also used the results in order to check for the correspondence of Mg peaks with growth bands.

2.5 Statistical analysis

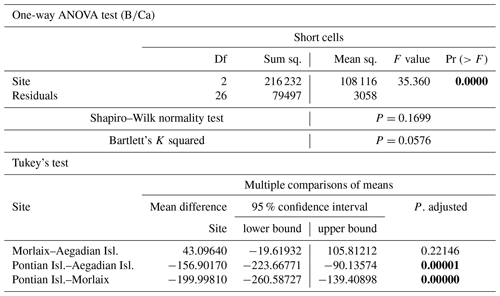

Statistics were calculated for both the dataset with all the spot analyses and the dataset with the records from long and short cells separately. Short cells refer to slow-growing cells in dark bands, usually produced in the cold season; long cells correspond to fast-growing cells in light bands, usually produced in the warm season (Kamenos et al., 2009; Ragazzola et al., 2016). For each spot, a distinction between the cells was thus made by image analyses, except for the Elba sample, given the poor resolution of the growth bands. The Spearman's correlation was tested to provide the statistical comparisons between , , , and records from the LA-ICP-MS analyses in L. corallioides. The Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by the Dunn's test for comparisons, and the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Tukey's test for post hoc analysis, were used to compare the geochemical signals among sampling sites and to evidence the differences between group medians and means. All statistical analyses were run in R 3.6.3 software.

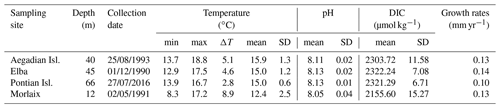

3.1 Environmental data

The temperature data obtained by ORAS5 reanalysis revealed a lower amplitude of the seasonal temperature change in the Mediterranean samples with respect to the Atlantic site, as shown by the standard deviation and ΔT values in Table 1. This difference is explained in terms of the different sampling depths, with the seasonal variations decreasing with increasing depth.

Temperature variations in Morlaix Bay (Atlantic Ocean) were higher, registering an overall mean seawater temperature of 12.4 ∘C (Table 1). Among Mediterranean samples, mean seawater temperatures were highest in the Aegadian Isl., followed by Elba and the Pontian Isl. (Table 1). Aegadian Isl. also registered the highest temperature variations among the Mediterranean sites (Table 1). Moderate temperature variations characterized the site in Elba, which registered the lowest monthly mean temperature among Mediterranean sites (Table 1). At the Pontian Isl., consistent with the fact that it is the deepest sampling site at 66 m depth, the lowest seawater temperature variations were found (Table 1).

The pH estimates at the Mediterranean sites were all similarly high at ∼8.13 and less variable than the Atlantic site (8.05). The mean pH had slightly higher values in Pontian Isl. and Elba than Aegadian Isl. (Table 1). Similarly, DIC was higher in the Mediterranean sites and decreased in Morlaix, as this largely dictates the pH (Table 1).

Figure 11Correlation plots of growth rates and seawater temperature with in L. corallioides samples analysed in this study. Spearman's coefficient r, the p value, and the line equation are given. Temperature variations (ΔT) correspond to the differences between the maximum and minimum temperature registered over 11 years of monthly reanalysis (ORAS5). The means measured in long and short cells respectively correspond to the maximum and minimum temperature.

Figure 12Elemental ratios in L. corallioides collected in Morlaix Bay (scale bar: 200 µm). Mg, Li, and show cyclic variations mirroring the local seawater temperature. In the timeline, the coldest and the warmest months have been reported, which correspond to dark and light bands of growth. Element Ca ratios in the missing bands (asterisks) have been calculated as the means of the values measured in warm or cold periods. Monthly means of temperature have been extracted by ORAS5 reanalysis.

Table 1Environmental data from each sampling site. The minimum and maximum monthly means of temperature are indicated, as are the highest temperature variation (ΔT), the mean, and the standard deviation of the time series. Data from monthly means were extracted by 11 years of ORAS5 reanalysis. The pH and DIC for each sampling site are also indicated. The minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation values have been measured over the time interval 1999–2017. Carbonate system parameters have been extracted from monthly mean biogeochemical data provided by CMEMS.

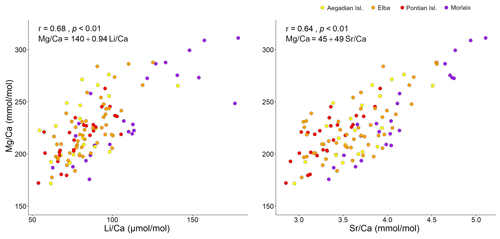

3.2 , , , and

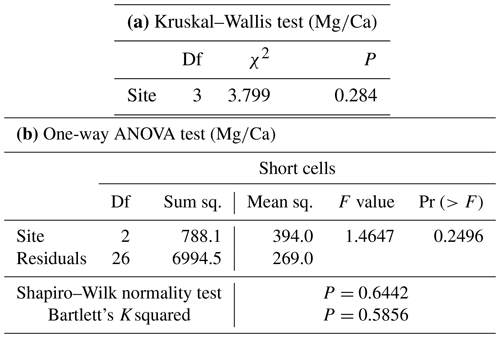

Both and records had positive correlations with in our samples of L. corallioides (Figs. 3 and S4). The overall mean was 225.3 ± 30.4 mmol mol−1, registering the minimum value in the sample from Aegadian Isl. (171.7 mmol mol−1) and the maximum value in Morlaix (311.2 mmol mol−1) (Fig. 4; Table 2). The Kruskal–Wallis test did not show significant differences in among samples (Table A1 in the Appendix; Fig. 4). Among Mediterranean sites, the algal sample from Aegadian Isl. had the highest mean value, followed by Elba and Pontian Isl., which had the lowest mean value of all sampling sites (Fig. 4). The highest mean was registered in the sample from Morlaix Bay, which also showed a large dispersion of data above the median value (Fig. 4).

Long cells had high values; conversely, short cells corresponded to areas with a low ratio.

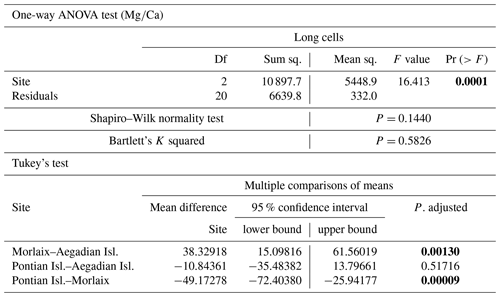

The ANOVA test followed by the Tukey's test for multiple comparisons evidenced a significant variability of algal among three sites in long cells (Table A2; Fig. 5). In the long cells of L. corallioides collected from Aegadian Isl. and Pontian Isl., the data showed a quite similar distribution (Table A2; Fig. 5). The of the alga from Pontian Isl. was the lowest (Fig. 5). In Morlaix a higher mean value was registered, which is significantly different compared to Aegadian and Pontian Isl. (Table A2; Fig. 5). In short cells, the differences in among samples were not statistically significant (Table A1). The magnesium incorporation was slightly higher in Morlaix and very similar between Aegadian and Pontian Isl. samples (Fig. 5).

values in long and short cells fell in the range found by Anagnostou et al. (2019) for cultured Clathromorphum compactum (Fig. 6). When plotted against the extracted seawater temperature in Morlaix (Fig. 7), results did not reflect the seasonal oscillations in temperature.

3.3

The ratio in the sample collected from Morlaix showed a moderate positive correlation with all the examined temperature proxies (, , ), with a more defined trend when plotted against (r=0.68) and slightly less defined against (r=0.58) and (r=0.57) (Fig. 8). On the contrary, the Spearman's analyses did not evidence significant correlations between and the temperature signals in the algae collected elsewhere (p>0.05).

Overall, the ratio in L. corallioides was 661.9 ± 138.9 µmol mol−1, registering the minimum value in the long cells of the sample from Pontian Isl. (356.0 µmol mol−1) and the maximum value in Elba (954.1 µmol mol−1) (Fig. 9; Table 2).

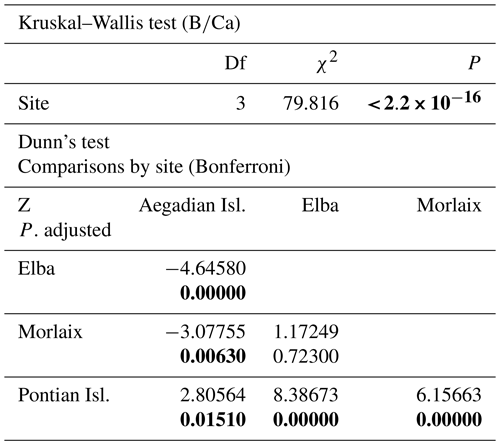

The Kruskal–Wallis coefficient showed a highly significant difference in the value among sites, particularly in the L. corallioides from the Pontian Isl., which had the lowest boron incorporation (Table A3; Fig. 9). The algae collected in Aegadian Isl. still had significantly lower compared to those collected in Elba and Morlaix (Table A3; Fig. 9). The highest mean value was registered in Elba, with medians comparable to Morlaix (Table A3; Fig. 9).

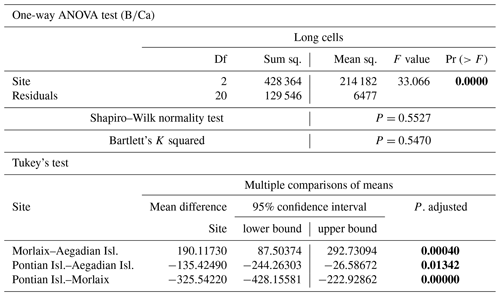

The ANOVA test followed by the Tukey's test for multiple comparisons by site, for long (Table A4) and short cells (Table A5) separately, showed lower values at the Mediterranean sites and higher values at the Atlantic site (Fig. 10).

The sample from Pontian Isl. had the lowest mean in both seasons, being significantly different from the samples from both Morlaix and Aegadian Isl. (Tables A4, A5; Fig. 10). Morlaix had the highest mean in both long and short cells (Tables A4, A5; Fig. 10). L. corallioides from Aegadian Isl. had an intermediate mean value in long cells, differing significantly from both the Morlaix and Pontian Isl. samples (Table A4; Fig. 10). In short cells, the sample from Aegadian Isl. slightly differed from the one in Morlaix (Table A5; Fig. 10).

Interestingly, the long cells of all samples had higher median values compared to short cells (Fig. 10), although only in Morlaix, the differences between measured in long and short cells were statistically significant (χ2=8.4899, p<0.01).

3.4 Growth rates

In the sample from Aegadian Isl., the LA-ICP-MS transect was 1.31 mm long, and 10 years of growth was detected by coupling microscopical imaging and peaks, resulting in a growth rate of 0.13 mm yr−1. In the Elba sample the laser transect was 1.15 mm long, crossing 8 years of growth, with a resulting growth rate of 0.14 mm yr−1. The Pontian Isl. sample had 1.08 mm of transect including 11 years of growth and hence a growth rate of 0.10 mm yr−1. Finally, the transect from the Morlaix sample was 1.38 mm long, counting 11 years and resulting in a growth rate of 0.13 mm yr−1.

Growth rates did not show any linear relationship with Mg, Li, and , but they were positively correlated with the sample mean values (Fig. 11).

Temperature variations affect many physiological processes involved in biomineralization, and the rate of calcification, along with the preservation state of mineral structures, influences the content of trace elements in carbonates (Lorens, 1981; Rimstidt et al., 1998; Gussone et al., 2005; Noireaux et al., 2015; Kaczmarek et al., 2016). Trace element concentrations recorded from the four L. corallioides branches analysed in this study were consistent with previously published values for other calcareous red algae (Chave, 1954; Hemming and Hanson, 1992; Hetzinger et al., 2011; Darrenougue et al., 2014). Particularly, the ratios recorded in this study ranged from 172 to 311 mmol mol−1, which is comparable to previous studies on rhodoliths of Lithothamnion glaciale Kjellman 1883 grown at 6–15 ∘C (148–326 mmol mol−1) (Kamenos et al., 2008). The ratios in L. corallioides from our results range from 356 to 954 µmol mol−1, which is wider than the range measured by solution ICP-MS on bulk samples of Neogoniolithon sp. (352–670 µmol mol−1) (Donald et al., 2017) and C. compactum (320–430 µmol mol−1) (Anagnostou et al., 2019), both cultured with controlled pCO2 and a pH ranging from 7.2 to 8.2. The high resolution given by laser ablation should be more effective in measuring the heterogeneity of across the thallus, thus explaining the wider range of our data.

The results evidenced a strong relationship with the seawater temperatures extracted from ORAS5 (Table 1; Fig. 12), as expected. L. corallioides from Aegadian Isl. had slightly higher values, followed by Elba and Pontian Isl. (Fig. 4). This was consistent with local temperature values in the Mediterranean (Table 1), since Pontian Isl. registered the lowest mean value and the lowest ΔT, while Aegadian Isl. showed the highest mean temperature and ΔT. On the contrary, the sample from Morlaix, collected at 12 m depth, showed high values in both long and short cells (Table A2; Fig. 5). The monthly mean temperatures had the highest variations during the year (ΔT in Table 1) due to the shallower depth (12 m) and the geographical location. Temperature correlates with seasons, influencing primary production, respiration, and calcification in L. corallioides (Payri, 2000; Martin et al., 2006) as well as other calcareous red algae (Roberts et al., 2002). The high seasonality that characterized the sample from Morlaix, represented by the high ΔT (Table 1), was probably responsible for the highest variation of values and undoubtedly accounted for most of the differences with Mediterranean samples. For the first time, we confirmed the reliability of the temperature proxies and on a wild-grown coralline alga collected at different depths and locations. and records were positively correlated with in L. corallioides (Fig. 3), which, in turn, showed a strong relationship with seawater temperature. Moreover, both Li and showed periodical oscillations in correspondence to long and short cells, related to seasonal temperature variations (Fig. 12). Therefore, and could be regarded as temperature proxies in L. corallioides, as could . The coupling of the ratio with and can be considered a useful technique to gather information about past temperature for paleoclimate reconstructions (Halfar et al., 2011; Caragnano et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2014; Fowell et al., 2016; Cuny-Guirriec et al., 2019).

The ratio in coralline algae has rarely been measured, and it is not clear how the environmental factors control its incorporation. The carbonate system primarily drives the changes in B incorporation (Hemming and Hanson, 1992; Yu and Elderfield, 2007). In benthic foraminifera, increases with [CO] (Yu and Elderfield, 2007), whereas there is no consensus on the effect of [CO] on and (Rosenthal et al., 2006; Dueñas-Bohórquez et al., 2011). Experiments with inorganic calcite showed a positive correlation between and [DIC] (Uchikawa et al., 2015). Nevertheless, in culture experiments of the coralline algae Neogoniolithon sp. (Donald et al., 2017) and corals (Gagnon et al., 2021), [DIC] had a negative effect on . DIC and values showed a negative relationship in the samples from Morlaix, Aegadian Isl., and Pontian Isl., which was not observed in Elba (Fig. 9; Table 1). Significant differences among values in the Mediterranean samples were not expected, since DIC concentrations were similar (Table 1). This evidence suggests influences other than DIC on the B signal.

The mean estimated growth rate of L. corallioides was 0.13 ± 0.02 mm yr−1, and it was supposed to decrease with increasing depth as a direct consequence of lower light availability (Halfar et al., 2011); indeed, the growth rate of the sample from Pontian Isl. was the lowest (0.10 mm yr−1). As already suggested by previous studies on both synthetic and biogenic calcite, B incorporation is likely affected by growth rate (Gabitov et al., 2014; Mavromatis et al., 2015; Noireaux et al., 2015; Uchikawa et al., 2015; Kaczmarek et al., 2016). Indeed, in the cultured calcareous red alga Neogoniolithon sp. increases with increasing growth rate (Donald et al., 2017). The slowest growth rate found in Pontian Isl. possibly contributed to the lowest value; similarly, the highest growth rate (0.14 mm yr−1) in the sample from Elba could be responsible for the highest (Figs. 9, 11). The mean annual growth rate of the shallowest sample (Morlaix) was intermediate (0.13 mm yr−1) and likely not constant during the year. In Morlaix, the alga probably significantly slowed down the growth in cold months, when the monthly mean seawater temperature was the lowest of all sampling sites (Table 1). Nevertheless, its growth rate likely sped up in the warm season due to the abundant light availability at shallow depth and the warming of seawater (Table 1), contributing to the significantly higher values in long cells (Fig. 10). According to this interpretation, the effect of the growth rate on might be significant across depth and geographical regions (Fig. 11).

In Morlaix, showed a weak positive correlation with temperature proxies (, , and ; Fig. 8). A positive correlation between and was already observed in planktonic foraminifera (Wara et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2007). Therefore, we reconstructed the elemental variations during algal growth in the Morlaix sample at annual resolution in order to highlight the influence of temperature (Fig. 12). Contrary to Mg, Li, and , the did not mirror the seasonal temperature variations as accurately as the other proxies.

In the sample from the Pontian Isl., the seasonal ΔT, , and values were the lowest among sites. In particular, was significantly low (Fig. 9), differing more from the other samples than the results for (Fig. 4). This suggests that in this sample the B incorporation should be influenced by factors other than those affecting Mg. In general, the poor correlation with seawater temperature (Fig. 11), and most of all the lack of distinct seasonal oscillations in across the algal thallus (Fig. 12), excludes the suitability of as a temperature proxy and suggests a closer relationship with growth rate than temperature.

Knowing the biogeochemistry and the variation of the environmental variables of seawater is crucial for a more comprehensive picture of the reliability of geochemical proxies like the ones investigated here (Mg, Li, , and ). Boron incorporation in marine carbonates is still debated, raising questions about the boron isotopic fractionation, the seawater isotopic composition, and the so-called “vital effects” (i.e. the metabolic activities that can bias the proxy record). Vital effects include species-specific biologically controlled up-regulations of pH in the calcifying fluid in both corals and coralline algae in response to pH manipulations mimicking the ongoing ocean acidification (Cornwall et al., 2017, 2018). Natural marine pH undergoes pH fluctuations with characteristic ranges of about 0.3 pH units in very shallow coastal water, in areas with restricted circulation, or in shallow nearshore communities supporting high rates of benthic metabolism, such as seagrass beds (Cornwall et al., 2013; Duarte et al., 2013; Hofmann et al., 2011). However, this study analysed the trace element record in a single high-Mg-calcite species grown in a natural wide bathymetric interval (from 10 to 66 m depth) characterized by normal marine pH (range 8.05–8.13, Table 1). Therefore, we considered up-regulation, if present, to be constant among our conspecific specimens and thus irrelevant for the measured variations. Moreover, no significant yearly pH fluctuations are expected at each site. Thus, within a single specimen, the observed differences in between short and long cells (i.e. cold and warm periods of growth) (Fig. 10) are unlikely to be related to changes in pHcf.

The paucity of measurements from coralline algae and, most of all, the complete absence of these data on specimens grown in nature make it difficult to compare our data with the literature. This observation takes stock of the significance of our results and emphasizes the importance of collecting more representative data in coralline algae. Further studies on L. corallioides and other calcareous red algae should be carried out to clarify the environmental factors influencing the in these organisms and to ensure the reliability of this proxy for paleoclimate reconstructions.

This paper presents the first measures of trace elements (Mg, Sr, Li, and B) from the coralline alga L. corallioides collected across the Mediterranean Sea and in the Atlantic Ocean at different oceanographic settings and depths (12, 40, 45, and 66 m depth), providing the first geochemical data on a wild-grown coralline algal species sampled at different depths and geographical locations. LA-ICP-MS records of , , and have shown a similar trend, primarily controlled by seawater temperatures in the algal habitat. On the contrary, did not provide a valuable temperature proxy in this species. In order to evaluate the control exerted by temperature over B incorporation, we also tested the correlation of with , . and . This led us to provide the first data on wild-grown coralline algae from across the photic zone in different basins. The correlation between and in L. corallioides was statistically significant only in the shallow Atlantic waters of Morlaix, where seasonality, and hence the seasonal temperature variations, during the algal growth was the strongest among sites. Accordingly, B incorporation differences between long and short cells of L. corallioides strongly depend on seasonality, being statistically significant just in Morlaix. Nevertheless, in contrast to Mg, Li, and , oscillations across the algal growth showed a poor relationship with seasonal variations in seawater temperature. We found high values in the Atlantic sample, wherein pH and DIC were the lowest. Carbon data did not explain the low B concentration in the Pontian Isl. sample (66 m depth), though, wherein pH and DIC were similar to the other Mediterranean sites. The estimation of growth rate, which was low in the Pontian Isl. sample (0.10 mm yr−1) and got higher in the other Mediterranean samples and in Morlaix (∼0.13 mm yr−1), led us to conclude that relates to growth rate rather than seawater temperature. B incorporation is therefore subject to the specific algal growth patterns and rates, knowledge of which is essential in order to assess the reliability of in tracing seawater carbon variations.

Table A1(a) Statistically non-significant results of tests performed to evaluate (a) the differences of in L. corallioides and (b) the differences of in the short cells of L. corallioides collected at different sampling sites. Test significance at α=0.05.

Table A2Results of statistical tests performed to evaluate the differences of in the long cells of L. corallioides collected at different sampling sites. Statistically significant p values are given in bold. ANOVA test significance at α=0.05; Tukey's test significant at p≤α.

Table A3Results of statistical tests performed to evaluate the differences of in L. corallioides collected at different sampling sites. Statistically significant p values are given in bold. Kruskal–Wallis test significance at α=0.05; Dunn's test significant at .

Table A4Results of statistical tests performed to evaluate the differences of in the long cells of L. corallioides collected at different sampling sites. Statistically significant p values are given in bold. ANOVA test significance at α=0.05; Tukey's test significant at p≤α.

Data resulting from this study are available at https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.932201 (last access: 28 January 2022, Piazza et al., 2021). Environmental data were provided by EU Copernicus Marine Service Information. DIC data in the Mediterranean: https://doi.org/10.25423/CMCC/MEDSEA_MULTIYEAR_BGC_006_008_MEDBFM3 (last access: 28 January 2022, Teruzzi et al., 2021). DIC data in the Atlantic Ocean: https://resources.marine.copernicus.eu/?option=com_cswview=detailsproduct_id=IBI_MULTIYEAR_BGC_005_003 (last access: 28 January 2022, Copernicus Marine Environmental Monitoring Service, 2020.) The pH data: https://resources.marine.copernicus.eu/?option=com_cswview=detailsproduct_id=GLOBAL_REANALYSIS_BIO_001_029 (last access: 13 October 2021, Perruche, 2018) Temperature data: https://icdc.cen.uni-hamburg.de/daten/reanalysis-ocean/easy-init-ocean/ecmwf-oras5.html (last access: 28 January 2022, Zuo et al., 2019).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-19-1047-2022-supplement.

DB, VAB, and GP conceptualized the research question and study design. AL, DB, and VAB conducted the experimental work. ANM and GP performed the environmental data extraction. GP performed the data analysis and prepared the draft of the paper. All authors contributed to the editing and reviewing of the paper.

The contact author has declared that neither they nor their co-authors have any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We are grateful to the anonymous referees whose comments enabled us to significantly improve the paper. This paper is a contribution to the project MIUR-Dipartimenti di Eccellenza 2018–2022 DISAT-UNIMIB. The Pontian Isl. sample has been collected in the framework of “Convenzione MATTM-CNR per i Programmi di Monitoraggio per la Direttiva sulla Strategia Marina (MSFD, Art. 11, Dir. 2008/56/CE)”. The captain, crew, and scientific staff of the RV Minerva Uno cruise Strategia Marina Ligure–Tirreno are acknowledged for their efficient and skilful cooperation at sea. Financial support for GP was provided by the University of Milano–Bicocca as a PhD fellowship.

This research has been supported by the national project FISR (grant no. 2019_04543 CRESCIBLUREEF).

This paper was edited by Aninda Mazumdar and reviewed by five anonymous referees.

Adey, W. H.: The genus Clathromorphum (Corallinaceae) in the Gulf of Maine, Hydrobiologia, 26, 539–573, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00045545, 1965.

Adey, W. H. and McKibbin, D.: Studies on the maerl species Phymatolithon calcareum (Pallas) nov. comb. and Lithothamnion coralloides Crouan in the Ria de Vigo, Bot. Mar., 13, 100–106, https://doi.org/10.1515/botm.1970.13.2.100, 1970.

Allen, K. A., Hönisch, B., Eggins, S. M., and Rosenthal, Y.: Environmental controls on in calcite tests of the tropical planktic foraminifer species Globigerinoides ruber and Globigerinoides sacculifer, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 351, 270–280, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2012.07.004, 2012.

Anagnostou, E., Williams, B., Westfield, I., Foster, G. L., and Ries, J. B.: Calibration of the pH-δ11B and temperature- proxies in the long-lived high-latitude crustose coralline red alga Clathromorphum compactum via controlled laboratory experiments, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 254, 142–155, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2019.03.015, 2019.

Andersson, A. J. and Mackenzie, F. T.: Technical comment on Kroeker et al. (2010) Meta-analysis reveals negative yet variable effects of ocean acidification on marine organisms, Ecol. Lett., 13, 1419–1434, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01646.x, 2011.

Andersson, A. J., Mackenzie, F. T., and Bates, N. R.: Life on the margin: implications on Mgcalcite, high latitude and cool-water marine calcifiers, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 373, 265–273, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps07639, 2008.

Barker, S., Cacho, I., Benway, H., and Tachikawa, K.: Planktonic foraminiferal as a proxy for past oceanic temperatures: a methodological overview and data compilation for the Last Glacial Maximum, Quat. Sci. Rev., 24, 821–834, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.07.016, 2005.

Basso, D.: Study of living calcareous algae by a paleontological approach: the non-geniculate Corallinaceae (Rhodophyta) of the soft bottoms of the Tyrrhenian Sea (western Mediterranean). The genera Phymatolithon Foslie and Mesophyllum Lemoine, Riv. Ital. Paleontol. S., 100, 575–596, https://doi.org/10.13130/2039-4942/8602, 1995a.

Basso, D.: Living calcareous algae by a paleontological approach: the genus Lithothamnion Heydrich nom. cons. from the soft bottoms of the Tyrrhenian Sea (Mediterranean), Riv. Ital. Paleontol. S., 101, 349–366, https://doi.org/10.13130/2039-4942/8592, 1995b.

Basso, D.: Carbonate production by calcareous red algae and global change, Geodiversitas, 34, 13–33, https://doi.org/10.5252/g2012n1a2, 2012.

Basso, D. and Brusoni, F.: The molluscan assemblage of a transitional environment: the Mediterranean maerl from off the Elba Island (Tuscan Archipelago, Tyrrhenian Sea), Boll. Malacol., 40, 37–45, 2004.

Basso, D., Babbini, L., Kaleb, S., Bracchi, V. A., and Falace, A.: Monitoring deep Mediterranean rhodolith beds, Aquat. Conserv., 26, 549–561, https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2586, 2016.

Basso, D., Babbini, L., Ramos-Esplá, A. A., and Salomidi, M.: Mediterranean rhodolith beds, in: Rhodolith/maërl beds: A global perspective, edited by: Riosmena-Rodrìguez, R., Wendy Nelson, W., and Aguirre, J., Springer, Cambridge, 281–298, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29315-8_ 11, 2017.

Berner, R. A.: The role of magnesium in the crystal growth of calcite and aragonite from sea water, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 39, 489–504, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(75)90102-7, 1975.

Bracchi, V. A., Piazza, G., and Basso, D.: A stable ultrastructural pattern despite variable cell size in Lithothamnion corallioides, Biogeosciences, 18, 6061–6076, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-18-6061-2021, 2021.

Brewer, P. G.: Ocean chemistry of the fossil fuel signal: The haline signature of “Business as Usual”, Geophys. Res. Lett., 24, 1367–1369, 1997.

Cabioch, J.: Contribution à I'étude morphologique, anatomique et systématique de deux Mélobésiées: Lithothamnium calcareum (Pallas) Areschoug et Lithothamnium corallioides Crouan, Bot. Mar., 9, 33–53, 1966.

Caldeira, K., Akai, M., Brewer, P., Chen, B., Haugan, P., Iwama, T., Johnston, P., Kheshgi, H., Li, Q., Ohsumi, T., Poertner, H., Sabine, C., Shirayama, Y., and Thomson, J.: Ocean Storage, in: Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage: A Special Report of IPCC Working Group III, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK, ISBN 10-0-521-68551-6, 2005.

Callendar, G. S.: The artificial production of carbon dioxide and its influence on temperature, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 64, 223–240, 1938.

Caragnano, A., Basso, D., Jacob, D. E., Storz, D., Rodondi, G., Benzoni, F., and Dutrieux, E.: Coralline red alga Lithophyllum kotschyanum f. affine as proxy of climate variability in the Yemen coast, Gulf of Aden (NW Indian Ocean), Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 124, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2013.09.021, 2014.

Caragnano, A., Basso, D., Storz, D., Jacob, D. E., Ragazzola, F., Benzoni, F., and Dutrieux, E.: Elemental variability in the coralline alga Lithophyllum yemenense as an archive of past climate in the Gulf of Aden (NW Indian Ocean), J. Phycol., 53, 381–395, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpy.12509, 2017.

Carro, B., Lopez, L., Peña, V., Bárbara, I., and Barreiro, R.: DNA barcoding allows the accurate assessment of European maerl diversity: a proof-of-concept study, Phytotaxa, 190, 176–189, https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.190.1.12, 2014.

Chan, P., Halfar, J., Adey, W., Hetzinger, S., Zack, T., Moore, G. W. K., Wortmann, U. G., Williams, B., and Hou, A.: Multicentennial record of Labrador Sea primary productivity and sea-ice variability archived in coralline algal barium, Nat. Commun., 8, 15543, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15543, 2017.

Chave, K. E.: Aspects of the biogeochemistry of magnesium 1. Calcareous marine organisms, J. Geol., 62, 266–283, 1954.

Copernicus Marine Environmental Monitoring Service: Atlantic-Iberian Biscay Irish-Ocean BioGeoChemistry NON ASSIMILATIVE Hindcast, CMEMS [data set], https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00028, 2020.

Cornwall, C. E., Hepburn, C. D., McGraw, C. M., Currie, K. I., Pilditch, C. A., Hunter, K. A., Boyd, P. W., and Hurd, C. L.: Diurnal fluctuations in seawater pH influence the response of a calcifying macroalga to ocean acidification, P. Roy. Soc. B-Bio., 280, 20132201, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.2201, 2013.

Cornwall, C. E., Comeau, S., and Mcculloch, M. T.: Coralline algae elevate pH at the site of calcification under ocean acidification, Glob. Change Biol., 23, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13673, 2017.

Cornwall, C. E., Comeau, S., DeCarlo, T. M., Moore, B., D'Alexis, Q., and McCulloch, M. T.: Resistance of corals and coralline algae to ocean acidification: physiological control of calcification under natural pH variability, P. Roy. Soc. B-Bio., 286, 20181168, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.1168, 2018.

Corrège, T.: Sea surface temperature and salinity reconstruction from coral geochemical tracers, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 232, 408–428, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.10.014, 2006.

Comeau, S., Cornwall, C. E., and McCulloch, M. T.: Decoupling between the response of coral calcifying fluid pH and calcification under ocean acidification, Sci. Rep., 7, 7573, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08003-z, 2017.

Cuny-Guirriec, K., Douville, E., Reynaud, S., Allemand, D., Bordier, L., Canesi, M., Mazzoli, C., Taviani, M., Canese, S., McCulloch, M., Trotter, J., Rico-Esenaro, S. D., Sanchez-Cabeza, J.-A., Ruiz-Fernàndez, A. C., Carricart-Ganivet, J. P., Scott, P. M., Sadekov, A., and Montagna, P.: Coral Li/Mg thermometry: Caveats and constraints, Chem. Geol., 523, 162–178, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2019.03.038, 2019.

Darrenougue, N., De Deckker, P, Eggins, S., and Payri, C.: Sea-surface temperature reconstruction from trace elements variations of tropical coralline red algae, Quat. Sci. Rev., 93, 34–46, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.03.005, 2014.

DeCarlo, T. M., Holcomb, M., and McCulloch, M. T.: Reviews and syntheses: Revisiting the boron systematics of aragonite and their application to coral calcification, Biogeosciences, 15, 2819–2834, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-2819-2018, 2018.

Dickson, A. G.: Thermodynamics of the dissociation of boric acid in synthetic seawater from 273.15 to 318.15 K, Deep-Sea Res., 37, 755–766, https://doi.org/10.1016/0198-0149(90)90004-F, 1990.

D'Olivo, J. P., Sinclair, D. J., Rankenburg, K., and McCulloch, M. T.: A universal multi-trace element calibration for reconstructing sea surface temperatures from long-lived Porites corals: removing “vital-effects”, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 239, 109–135, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2018.07.035, 2018.

Donald, H. K., Ries, J. B., Stewart, J. A., Fowell, S. E., and Foster, G. L.: Boron isotope sensitivity to seawater pH change in a species of Neogoniolithon coralline red alga, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 217, 240–253, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2017.08.021, 2017.

Douville, E., Paterne, M., Cabioch, G., Louvat, P., Gaillardet, J., Juillet-Leclerc, A., and Ayliffe, L.: Abrupt sea surface pH change at the end of the Younger Dryas in the central sub-equatorial Pacific inferred from boron isotope abundance in corals (Porites), Biogeosciences, 7, 2445–2459, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-7-2445-2010, 2010.

Duarte, C. M., Hendriks, I. E., Moore, T. S., Olsen, Y. S., Steckbauer, A., Ramajo, L., Jacob Carstensen, J., Trotter, J. A., and McCulloch, M.: Is ocean acidification an open-ocean syndrome?, Understanding anthropogenic impacts on seawater pH, Estuar. Coast., 36, 221–236, 2013.

Dueñas-Bohórquez, A., Raitzsch, M., Nooijer, L. J., and Reichart, G.-J.: Independent impacts of calcium and carbonate ion concentration on Mg and Sr incorporation in cultured benthic foraminifera, Mar. Micropaleontol., 81, 122–130, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2011.08.002, 2011.

Fairhall, A. W.: Accumulation of fossil CO2 in the atmosphere and the sea, Nature, 245, 20–23, 1973.

Fietzke, J., Heinemann, A., Taubner, I., Böhm, F., Erez, J., and Eisenhauer, A.: Boron isotope ratio determination in carbonates via LA-MC-ICP-MS using soda-lime glass standards as reference material, J. Anal. At. Spectrom., 25, 1953–1957, https://doi.org/10.1039/C0JA00036A, 2010.

Fietzke, J., Ragazzola, F., Halfar, J., Dietze, H., Foster, L. C., Hansteen, T. H., Eisenhauer, A., and Steneck, R. S.: Century-scale trends and seasonality in pH and temperature for shallow zones of the Bering Sea, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 112, 2960–2965, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1419216112, 2015.

Foster, G. L.: Seawater pH, pCO2 and [CO] variations in the Caribbean Sea over the last 130 kyr: a boron isotope and study of planktic foraminifera, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 271, 254–266, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2008.04.015, 2008.

Foster, M. S.: Rhodoliths: between rocks and soft places, J. Phycol., 37, 659–667, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1529-8817.2001.00195.x, 2001.

Fowell, S. E., Sandford, K., Stewart, J. A., Castillo, K. D., Ries, J. B., and Foster, G. L.: Intrareef variations in Li/Mg and sea surface temperature proxies in the Caribbean reef-building coral Siderastrea sidereal, Paleoceanography, 31, 1315–1329, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016PA002968, 2016.

Frantz, B. R., Foster, M. S., and Riosmena-Rodríguez, R.: Clathromorphum nereostratum (Corallinales, Rhodophyta): The oldest alga?, J. Phycology, 41, 770–773, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00107.x, 2005.

Freiwald, A. and Henrich, R.: Reefal coralline algal build-ups within the Arctic Circle: morphology and sedimentary dynamics under extreme environmental seasonality, Sedimentology, 41, 963–984, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.1994.tb01435.x, 1994.

Gabitov, R. I., Rollion-Bard, C., Tripati, A., and Sadekov, A.: In situ study of boron partitioning between calcite and fluid at different crystal growth rates, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 137, 81–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2014.04.014, 2014.

Gagnon, A. C., Gothmann, A. M., Branson, O., Rae, J. W. B., and Stewart, J. A.: Controls on boron isotopes in a cold-water coral and the cost of resilience to ocean acidification, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 554, 116662, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116662, 2021.

Gattuso, J.-P., Frankignoulle, M., and Smith, S. V.: Measurement of community metabolism and significance in the coral reef CO2 source-sink debate, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 13017–13022, 1999.

Gussone, N., Böhm, F., Eisenhauer, A., Dietzel, M., Heuser, A., Teichert, B. M. A., Reitner, J., Wörheide, G., and Dullo, W.-C.: Calcium isotope fractionation in calcite and aragonite, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 69, 4485–4494, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2005.06.003, 2005.

Halfar, J., Zack, T., Kronz, A., and Zachos, J. C.: Growth and high-resolution paleoenvironmental signals of rhodoliths (coralline red algae): A new biogenic archive, J. Phys. Res., 105, 22107–22116, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JC000128, 2000.

Halfar, J., Steneck, R. S., Joachimski, M., Kronz, A., and Wanamaker, A. D. Jr.: Coralline red algae as high-resolution climate recorders, Geology, 36, 463–466, https://doi.org/10.1130/G24635A.1, 2008.

Halfar, J., Williams, B., Hetzinger, S., Steneck, R. S., Lebednik, P., Winsborough, C., Omar, A., Chan, P., and Wanamaker, A. D.: 225 years of Bering Sea climate and ecosystem dynamics revealed by coralline algal growth-increment widths, Geology, 39, 579–582, https://doi.org/10.1130/g31996.1, 2011.

Hall-Spencer, J. M., Kelly, J., and Maggs, C. A.: Background document for maërl beds, in: OSPAR Commission Biodiversity Series, OSPAR Commission, London, ISBN 978-1-907390-32-6, 2010.

Hemming, N. G. and Hanson, G. N.: Boron isotopic composition and concentration in modern marine carbonates, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 56, 537–543, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(92)90151-8, 1992.

Hemming, N. G. and Hönisch, B.: Boron isotopes in marine carbonate sediments and the pH of the ocean, in: Proxies in Late Cenozoic Paleoceanography, edited by: Hillaire-Marcel, C. and de Vernal, A., Elsevier, 717–734, 2007.

Henehan, M. J., Rae, J. W. B., Foster, G. L., Erez, J., Prentice, K. C., Kucera, M., Bostock, H. C., Martınez-Boti, M. A., Milton, J. A., Wilson, P. A., Marshall, B. J., and Elliott, T.: Calibration of the boron isotope proxy in the planktonic foraminifera Globigerinoides ruber for use in palaeo-CO2 reconstruction, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 364, 111–122, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2012.12.029, 2013.

Henehan, M. J., Foster, G. L., Rae, J. W. B., Prentice, K. C., Erez, J., Bostock, H. C., Marshall, B. J., and Wilson, P. A.: Evaluating the utility of ratios in planktic foraminifera as a proxy for the carbonate system: a case study of Globigerinoides ruber: investigating controls on G. ruber , Geochem. Geophys., 16, 1052–1069, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GC005514, 2015.

Hetzinger, S., Halfar, J., Kronz, A., Steneck, R., Adey, W. H., Philipp, A. L., and Schöne, B.: High-resolution ratios in a coralline red alga as a proxy for Bering Sea temperature variations from 1902–1967, Palaois, 24, 406–412, https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2008.p08-116r, 2009.

Hetzinger, S., Halfar, J., Zack, T., Gamboa, G., Jacob, D. E., Kunz, B. E., Kronz, A., Adey, W., Lebednik, P. A., and Steneck, R. S.: High-resolution analysis of trace elements in crustose coralline algae from the North Atlantic and North Pacific by laser ablation ICP-MS, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 302 , 81–94, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.06.004, 2011.

Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Mumby, P. J., Hooten, A. J., Steneck, R. S., Greenfield, P., Gomez, E., Harvell, C. D., Sale, P. F., Edwards, A. J., Caldeira, K., Knowlton, N., Eakin, C. M., Iglesias-Prieto, R., Muthiga, N., Bradbury, R. H., Dubi, A., and Hatziolos, M. E.: Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification, Science, 318, 1737–1742, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1152509, 2007.

Holcomb, M., DeCarlo, T. M., Gaetani, G. A., and McCulloch, M.: Factors affecting ratios in synthetic aragonite, Chem. Geol., 437, 67–76, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.05.007, 2016.

Hönisch, B. and Hemming, N. G.: Surface ocean pH response to variations in pCO2 through two full glacial cycles, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 236, 305–314, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2005.04.027, 2005.

Hönisch, B., Ridgwell, A., Schmidt, D. N., Thomas, E., Gibbs, S. J., Sluijs, A., Zeebe, R., Kump, L., Martindale, R. C., Greene, S. E., Kiessling, W., Ries, J., Zachos, J. C., Royer, D. L., Barker, S., Marchitto Jr., T. M., Moyer, R., Pelejero, C., Ziveri, P., Foster, G. L., and Williams, B.: The geological record of ocean acidification, Science, 335, 1058–1063, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1208277, 2012.

Irvine, L. M. and Chamberlain, Y. M. (Eds.): Volume 1 Rhodophyta Part 2B. Corallinales, Hildenbrandiales, Natural History Museum, London, ISBN 0-11-310016-7, 1994.

Hofmann, G. E., Smith, J. E., Johnson, K. S., Send, U., Levin, L. A., Micheli, F., Paytan, A., Price, N. N., Peterson, B., Takeshita, Y., Matson, G. P., Crook, E. D., Kroeker, K. J., Gambi, M. C., Rivest, E. B., A. Frieder, C. A., Yu, P. C., and Martz T. R.: High-frequency dynamics of ocean pH: a multi-ecosystem comparison, PLoS ONE, 6, e28983, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0028983, 2011.

Hou, A., Halfar, J., Adey, W., Wortmann, U. G., Zajacz, Z., Tsay, A., Williams, B., and Chan, P.: Long-lived coralline alga records multidecadal variability in Labrador Sea carbon isotopes, Chem. Geol., 526, 93–100, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2018.02.026, 2018.

Jochum, K. P., Scholz, D., Stoll, B., Weis, U., Wilson, S. A., Yang, Q., Schwalb, A., Börner, N., Jacob, D. E., and Andreae, M. O.: Accurate trace element analysis of speleothems and biogenic calcium carbonates by LA-ICP-MS, Chem. Geol., 318, 31–44, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2012.05.009, 2012.

Kaczmarek, K., Nehrke, G., Misra, S., Bijma, J., and Elderfield, H.: Investigating the effects of growth rate and temperature on the ratio and δ11B during inorganic calcite formation, Chem. Geol., 421, 81–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2015.12.002, 2016.

Kamenos, N. A., Cusack, M., and Moore, P. G.: Coralline algae are global paleothermometers with bi-weekly resolution, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 72, 771–779, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2007.11.019, 2008.

Kamenos, N. A., Cusack, M., Huthwelker, T., Lagarde, P., and Scheibling, R. E.: Mg-lattice associations in red coralline algae, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 73, 1901–1907, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2009.01.010, 2009.

Kamenos, N. A., Hoey, T., Nienow, P., Fallick, A. E., and Claverie, T.: Reconstructing Greenland Ice sheet runoff using coralline algae, Geology, 40, 1095–1098, https://doi.org/10.1130/G33405.1, 2012.

Keul, N., Langer, G., Thoms, S., de Nooijer, L. J., Reichart, G. J., and Bijma, J.: Exploring foraminiferal as a new carbonate system proxy, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 202, 374–386, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2016.11.022, 2017.

Klochko, K., Cody, G. D., Tossell, J. A., Dera, P., and Kaufman, A. J.: Re-evaluating boron speciation in biogenic calcite and aragonite using 11B MAS NMR, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 73, 1890–1900, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2009.01.002, 2009.

Lorens, R. B.: Sr, Cd, Mn and Co distribution coefficients in calcite as a function of calcite precipitation rate, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 45, 553–561, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(81)90188-5, 1981.

Martin, S., Castets, M.-D., and Clavier, J.: Primary production, respiration and calcification of the temperate free-living coralline alga Lithothamnion corallioides, Aquat. Bot., 85, 121–128, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2006.02.005, 2006.

Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E, Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Telekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B.: IPCC: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, in: Contribution ofWorking Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report 50 of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK, ISBN 978-92-9169-158-6, 2021.

Mavromatis, V., Montouillout, V., Noireaux, J., Gaillardet, J., and Schott, J.: Characterization of boron incorporation and speciation in calcite and aragonite from co-precipitation experiments under controlled pH, temperature and precipitation rate, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 150, 299–313, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2014.10.024, 2015.

McCulloch, M., Trotter, J., Montagna, P., Falter, J., Dunbar, R., Freiwald, A., Försterra, G., Correa, M. L., Maier, C., Rüggeberg, A., and Taviani, M.: Resilience of cold-water scleractinian corals to ocean acidification: boron isotopic systematics of pH and saturation state up-regulation, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 87, 21–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2012.03.027, 2012.

Melbourne, L. A., Hernández-Kantún, J., Russell, S., and Brodie, J.: There is more to maerl than meets the eye: DNA barcoding reveals a new species in Britain, Lithothamnion erinaceum sp. nov. (Hapalidiales, Rhodophyta), Eur. J. Phycol., 52, 166–178, https://doi.org/10.1080/09670262.2016.1269953, 2017.

Moberly, R.: Composition of magnesian calcites of algae and pelecypods by electron microprobe analysis, Sedimentology, 11, 61–82, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.1968.tb00841.x, 1968.

Moberly, R: Microprobe study of diagenesis in calcareous algae, Sedimentology, 14, 113–123, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.1970.tb00185.x, 1970.

Montagna, P. and Douville, E.: Geochemical proxies in marine biogenic carbonates: New developments and applications to global change, Chem. Geol., 533, 119411, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2019.119411, 2020.

Morse, J. W., Andersson, A. J., and Mackenzie, F. T.: Initial responses of carbonate-rich shelf sediments to rising atmospheric pCO2 and “ocean acidification”: role of high Mg-calcites, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 70, 5814–5830, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2006.08.017, 2006.

Nash, M. C., Martin, S., and Gattuso, J.-P.: Mineralogical response of the Mediterranean crustose coralline alga Lithophyllum cabiochae to near-future ocean acidification and warming, Biogeosciences, 13, 5937–5945, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-13-5937-2016, 2016.

Noireaux, J., Mavromatis, V., Gaillardet, J., Schott, J., Montouillout, V., Louvat, P., Rollion-Bard, C., and Neuville, D. R.: Crystallographic control on the boron isotope paleo-pH proxy, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 430, 398–407, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2015.07.063, 2015.

Paris, G., Bartolini, A., Donnadieu, Y., Beaumont, V., and Gaillardet, J.: Investigating boron isotopes in a middle Jurassic micritic sequence: primary vs. diagenetic signal, Chem. Geol., 275, 117–126, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2010.03.013, 2010.

Payri, C. E.: Production primaire et calcification des algues benthiques en milieu corallien, Oceanis, 26, 427–463, 2000.

Perruche, C.: Product user manual for the Global Ocean Biogeochemistry Hindcast GLOBAL_REANALYSIS_BIO_001_029, Version 1, Copernicus Marine Environmental Monitoring Service, [data set], 17 pp., https://doi.org/10.25607/OBP-490, 2018.

Piazza, G., Bracchi, V. A., Basso, D.: Mg, Li, Sr and in the calcareous red alga Lithothamnion corallioides, PANGAEA [data set], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.932201, 2021.

Potin, P., Floc'h, J.-Y., Augris, C., and Cabioch, J.: Annual growth rate of the calcareous red algae Lithothamnion corallioides (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) in the Bay of Brest, France, Hydrobiologia, 204–205, 263–267, 1990.

Rae, J. B. R., Foster, G. L., Schmidt, D. N., and Elliott, T.: Boron isotopes and in benthic foraminifera: proxies for the deep ocean carbonate system, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 302, 403–413, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2010.12.034, 2011.

Ragazzola, F., Foster, L. C., Form, A., Anderson, P. S. L., Hansteen, T. H., and Fietzke, J.: Ocean acidification weakens the structural integrity of coralline algae, Glob. Change Biol., 18, 2804–2812, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02756.x, 2012.

Ragazzola, F., Foster, L. C., Jones, C. J., Scott, T. B., Fietzke, J., Kilburn, M. R., and Schmidt, D. N.: Impact of high CO2 on the geochemistry of the coralline algae Lithothamnion glaciale, Sci. Rep., 6, 20572, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20572, 2016.

Ragazzola, F., Caragnano, A., Basso, D., Schmidt, D. N., and Fietzke, J.: Establishing temperate crustose Early Holocene coralline algae as archived for paleoenvironmental reconstructions of the shallow water habitats of the Mediterranean Sea, Paleontology, 63, 155–170, https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12447, 2020.

Ries, J. B.: Mg fractionation in crustose coralline algae: geochemical, biological and sedimentological implications of secular variation in ratio of seawater, Geochim, Cosmochim. Ac., 70, 891–900, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2005.10.025, 2006.

Ries, J. B., Ghazaleh, M. N., Connolly, B., Westfield, I., and Castillo, K. D.: Impacts of seawater saturation state (ΩA = 0.4–4.6) and temperature (10, 25 ∘C) on the dissolution kinetics of whole-shell biogenic carbonates, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 192, 318–337, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2016.07.001, 2016.

Rimstidt, J. D., Balog, A., and Webb, J.: Distribution of trace elements between carbonate minerals and aqueous solutions, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 62, 1851–1863, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(98)00125-2, 1998.

Roberts, R. D., Kühl, M., Glud, R. N., and Rysgaard, S.: Primary production of crustose coralline algae in a high Artic Fjord, J. Phycol., 38, 273–283, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1529-8817.2002.01104.x, 2002.

Rosenthal, Y., Lear, C. H., Oppo, D. W., and Braddock, K. L.: Temperature and carbonate ion effects on and ratios in benthic foraminifera: Aragonitic species Hoegludina elegans, Paleoceanography, 21, PA1007, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005PA001158, 2006.

Savini, A., Basso, D., Bracchi, V. A., Corselli, C., and Pennetta, M.: Maerl-bed mapping and carbonate quantification on submerged terraces offshore the Cilento peninsula (Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy), Geodiversitas, 34, 77–98, https://doi.org/10.5252/g2012n1a5, 2012.

Schöne, B. R., Fiebig, J., Pfeiffer, M., Gleb, R., Hickson, J., Johnson, L. A., Dreyer, A. W., and Oschmann, W.: Climate records from a bivalved Methuselah (Arctica islandica, Mollusca; Iceland), Palaeogeogr., Palaeocl., 228, 130–148, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.03.049, 2005.

Teruzzi, A., Di Biagio, V., Feudale, L., Bolzon, G., Lazzari, P., Salon, S., Di Biagio, V., Coidessa, G., and Cossarini, G.: Mediterranean Sea Biogeochemical Reanalysis (CMEMS MED-Biogeochemistry, MedBFM3 system) (Version 1) [data set], Copernicus Monitoring Environment Marine Service (CMEMS), https://doi.org/10.25423/CMCC/MEDSEA_MULTIYEAR_BGC_006_008_MEDBFM3 (last access: 28 January 2022), 2021.

Uchikawa, J., Penman, D. E., Zachos, J. C., and Zeebe, R. E.: Experimental evidence for kinetic effects on in synthetic calcite: Implications for potential B(OH) and B(OH)3 incorporation, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 150, 171–191, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2014.11.022, 2015.

Vengosh, A., Kolodny, Y., Starinsky, A., Chivas, A. R., and McCulloch, M. T.: Coprecipitation and isotopic fractionation of boron in modern biogenic carbonates, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 55, 2901–2910, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(91)90455-E, 1991.

Wara, M. W., Delaney, M. L., Bullen, T. D., and Ravelo, A. C.: Possible roles of pH, temperature, and partial dissolution in determining boron concentration and isotopic composition in planktonic foraminifera, Paleoceanography, 18, 1100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002PA000797, 2003.

Williams, B., Halfar, J., Delong, K. L., Hetzinger, S., Steneck, R. S., and Jacob, D. E.: Multi-specimen and multi-site calibration of Aleutian coralline algal to sea surface temperature, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 139, 190–204, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2014.04.006, 2014.

Wilson, S., Blake, C., Berges, J. A., and Maggs, C. A.: Environmental tolerances of free-living coralline algae (maerl): implications for European marine conservation, Biol. Conserv., 120, 279–289, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2004.03.001, 2004.

Yu, J. M. and Elderfield, H.: Benthic foraminiferal ratios reflect deep water carbonate saturation state, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 258, 73–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2007.03.025, 2007.

Yu, J. M., Elderfield, H., and Hönisch, B.: in planktonic foraminifera as a proxy for surface water pH, Paleoceanography, 22, 2202, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006PA001347, 2007.

Yu, J., Day, J., Greaves, M., and Elderfield, H.: Determination of multiple element/calcium ratios in foraminiferal calcite by quadrupole ICP-MS, Geochem. Geophys., 6, Q08P01, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GC000964, 2015.

Zeebe, R. E. and Wolf-Gladrow, D. (Eds.): CO2 in seawater: equilibrium, kinetics, isotopes, Elsevier Oceanography Book Series, Amsterdam, 65 pp., 2001.

Zuo, H., Balmaseda, M. A., Tietsche, S., Mogensen, K., and Mayer, M.: The ECMWF operational ensemble reanalysis–analysis system for ocean and sea ice: a description of the system and assessment, Ocean Sci., 15, 779–808, https://doi.org/10.5194/os-15-779-2019, 2019.