the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Serpulid microbialitic bioherms from the upper Sarmatian (Middle Miocene) of the central Paratethys Sea (NW Hungary) – witnesses of a microbial sea

Mathias Harzhauser

Oleg Mandic

Werner E. Piller

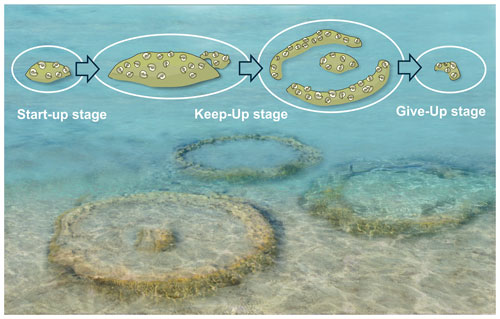

We present previously unknown stacked bowl-shaped bioherms reaching a size of 45 cm in diameter and 40 cm in height from weakly solidified peloidal sand from the upper Sarmatian of the Paratethys Sea. The bioherms were mostly embedded in sediment, and the “growth stages” reflect a reaction on sediment accretion and sinking into the soft sediment. The bioherms are spirorbid–microclot–acicular cement boundstones with densely packed Janua tubes surrounded by microclots and acicular cement solidifying the bioherm. The surrounding sediment is a thrombolite made of peloids and polylobate particles (mesoclots) which are solidified synsedimentarily by micrite cement and dog-tooth cement in a later stage. The shape of the bioherms reflects a series of growth stages with an initial stage (“start-up stage”) followed by a more massive “keep-up stage” which grades into a structure with a collar-like outer rim and a central protrusion and finally by a termination of growth (“give-up stage”). The setting was a shallow subtidal environment with normal marine or elevated saline, probably oligotrophic, conditions with an elevated alkalinity. The stacked bowl-shaped microbialites are a unique feature that has so far been undescribed. Modern and Neogene microbialite occurrences are not direct analogues to the described structures, but the marine examples, like in The Bahamas, Shark Bay and the Persian Gulf, offer insight into their microbial composition and environmental parameters.

The microbialites and the surrounding sediment document a predominance of microbial activity in the shallow marine environments of the Paratethys Sea during the late Middle Miocene, which was characterized by a warm, arid climate.

- Article

(23007 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The Miocene central Paratethys Sea was a warm temperate to subtropical sea covering large parts of central and southeastern Europe (Rögl, 1998; Popov et al., 2004; Harzhauser and Piller, 2007). Normal marine conditions prevailed during most of the Badenian (Langhian and early Serravallian) with a moderately diverse scleractinian coral reef fauna (Riegl and Piller, 2000; Perrin and Bosellini, 2012; Wiedl et al., 2013). Microbialites were of subordinate importance in these ecosystems except for a short phase around 13.8 Ma at the Langhian–Serravallian boundary. At that time the Paratethyan basins became largely isolated from the proto-Mediterranean Sea and hypersaline conditions of the Badenian salinity crisis resulted in the formation of evaporites (de Leeuw et al., 2010; Bukowski, 2011; Śliwiński et al., 2012). Stromatolites formed in restricted lagoons (Harzhauser et al., 2014). Around 12.7 Ma, a major extinction event, termed the Badenian–Sarmatian Extinction Event (BSEE) (Harzhauser and Piller, 2007; Palcu et al., 2015), caused a final collapse of Paratethyan coral reef communities, accompanied by a dramatic decline in the diversity of calcareous red algae. The BSEE marked the onset of the Sarmatian, which was characterized by a peculiar endemic marine fauna (Harzhauser and Piller, 2007). During the early Sarmatian, bryostromatolites were established in coastal–lagoonal settings, pointing to eutrophication and polyhaline salinities (Piller and Harzhauser, 2023, and references therein). Around 12 Ma, climate warming and aridification changed the environmental conditions of the Sarmatian Paratethys and normal marine to elevated saline conditions prevailed (Latal et al., 2004). Kranner et al. (2021) calculated salinities of around 37 psu for late Sarmatian foraminiferal assemblages from the Vienna Basin. Oolite shoals became widespread during the late Sarmatian in the central Paratethys Sea (Piller and Harzhauser, 2005). At that time, the bryostromatolites had vanished and had been replaced by another type of microbialites lacking bryozoans. These upper Sarmatian bioherms are classified as foraminiferal Nubecularia boundstones, Nubecularia coralline algal boundstones, stromatolitic and thrombolitic boundstones, and serpulid nubeculariid microbial boundstones (Piller and Harzhauser, 2023). The structure described herein is, however, different from the described boundstones in representing stacked bowl-shaped microbialites with a high share of the serpulid Janua. Many modern marine microbialites occur in oligotrophic intertidal to shallow subtidal environments, often affected by aridity and hypersalinity (Siqueiros-Beltrones, 2008; Johnson et al., 2012; Mobberley et al., 2015). Photosynthetic Cyanobacteria and Proteobacteria are the most important groups in these microbialites (Mobberley et al., 2015), but a broad consortium of other microbes contribute to the microbial mats of living structures including other bacteria, archaea and various heterotrophic eukaryotes (Khodadad and Foster, 2012; Edgcomb et al., 2014).

The paleoecological interpretation of the Sarmatian Sea has so far especially been based on its mollusk assemblages and foraminiferal faunas (e.g., Harzhauser and Piller, 2007; Kranner et al., 2021, and references therein). The bioherms observed herein, in contrast, have not been described so far. Consequently, no information on the paleoenvironmental indications of these structures is available. Herein, we want to elucidate the main constituents of the bioherms to describe the composition, structure and mode of growth of these enigmatic bioherms. This information will give new insights into the marine ecosystems of the Sarmatian Sea.

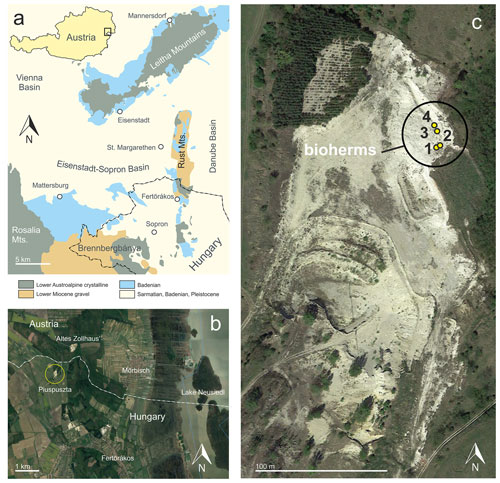

Sarmatian microbialites were detected in 2004 in the Piuspuszta gravel pit in NW Hungary (Fig. 1). The pit is situated in the Eisenstadt–Sopron Basin, which is a triangular Neogene structure of about 20 km width (Harzhauser, 2022). To the north, the basin is confined by the NE–SW-trending Leitha Mountains, while the Rust Mountains separate it from the Danube Basin to the east. A crystalline ridge, covered by Lower Miocene gravel, extending from the Rosalia Mountains to Brennbergbánya, defines the basin's southern margin. This topographical barrier separates the Eisenstadt–Sopron Basin from the Oberpullendorf and Styrian basins. Sedimentation started during the Early Miocene with fluvial gravel and ended during the Late Miocene with lacustrine deposits of Lake Pannon (Harzhauser, 2022).

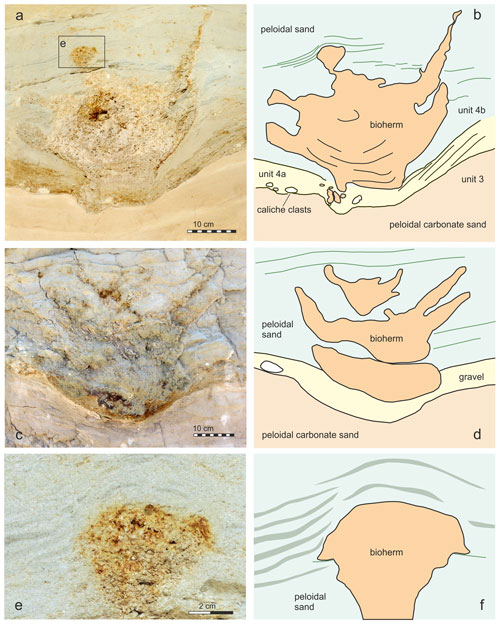

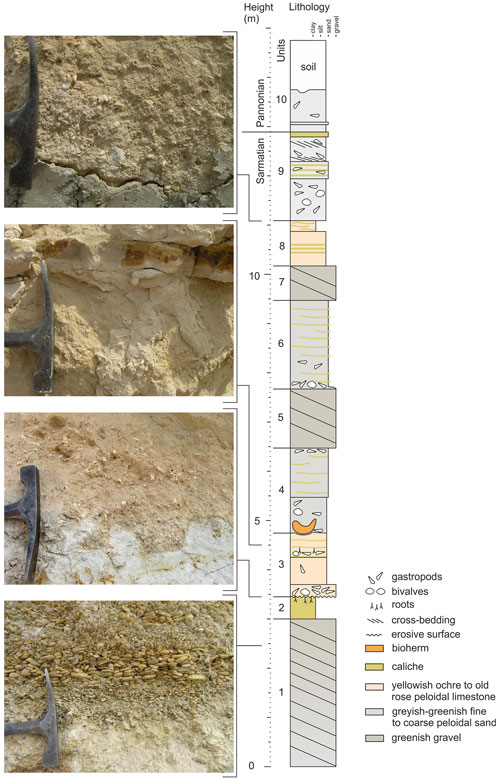

Figure 2The Piuspuszta section based on the outcrop situation in 2004. The bioherms are situated in the base of unit 4.

The gravel pit is located about 400 m SSW of the border crossing point St Margarethen at the Hungarian–Austrian border and 3 km NNW of Fertörákos in Hungary (Fig. 1). The outcrop is generally abandoned, but occasionally gravel is exploited for local use. Within the pit, upper Sarmatian and lower Pannonian deposits are exposed along two levels. The lower level is situated in the southern part of the pit and exposes about 8 m of upper Sarmatian marine gravel of a Gilbert-type delta passing into well-sorted fine to medium sand with Sarmatimactra vitaliana and Sarmatigibbula podolicus and large, platy sandstone concretions (47∘45.146′ N, 16∘37.118′ E). In the upper level of the pit, an about 10 m thick succession crops out (Fig. 2) along an about 35 m long NNW–SSE-trending section. The upper level represents the overlying succession of the gravel and sand of the lower level, but both occurrences are separated by a fault, associated with the Kőhida fault zone (Rosta, 1993). The investigated bioherms were detected in 2004 in the eastern part of the gravel pit (47∘45.196′ N, 16∘37.122′ E).

During the last few years, the Piuspuszta gravel pit was frequently visited during geological excursions, but only very limited published data are available for the outcrop. Rosta (1993) described parts of the section and identified the lower part of the outcrop as part of a Sarmatian Gilbert-type delta. A lateral equivalent of the Piuspuszta section outcrops south of St Margarethen in Austria at the “Altes Zollhaus” section (Fig. 1) from where Harzhauser and Kowalke (2002) and Harzhauser et al. (2002) described Sarmatian and Pannonian mollusk faunas and Piller and Harzhauser (2023) serpulid nubeculariid microbial boundstones. Latal et al. (2004) provided stable isotope data on some of the mollusks from St Margarethen.

2.1 The Piuspuszta section

The section starts with 3 m of well-sorted marine gravel, frequently showing imbrication, grading in the top into a 40 cm thick layer of whitish caliche (units 1 and 2 in Fig. 2) (47∘45.248′ N, 16∘37.143′ E). Above a strong relief of up to 15 cm amplitude follows an about 1.3 m thick fining-upward unit of weakly solidified old rose peloidal calcareous sand with scattered gravel and abundant mollusks (unit 3). An about 15 cm thick horizon with thin limonitic roots occurs in the upper part of the unit, where discontinuous caliche layers become frequent. Above follows a 1.7 m thick unit of weakly solidified, greenish-grey, peloidal calcareous sand with fine to coarse siliciclastic sand and occasional gravel stringers (unit 4). Discontinuous caliche layers and a rich mollusk assemblage occur in unit 4. The described bioherms start close above the base of unit 4 (47∘45.227′ N, 16∘37.162′ E), which is overlain by a succession of 1.2 m of gravel (unit 5), 1.8 m of greenish-greyish peloidal sand with abundant caliche layers (unit 6) and 0.7 m of gravel (unit 7). Unit 8 represents a 0.9 m thick bed of old rose peloidal calcareous sand with siliciclastic fine to middle sand and gravel and frequent caliche layers. The upper part of the Sarmatian succession is formed by 1.8 m fossiliferous mixed-carbonate–siliciclastic fine to middle sand with a thick caliche layer in the top (unit 9). Above follows an about 1 m thick unit of poorly sorted fine to coarse sand with gravel, layers of small oncoids and frequent shells of Melanopsis pseudonarzolina (unit 10) (47∘45.238′ N, 16∘37.163′ E).

2.2 Biostratigraphy

The occurrence of the bivalve Sarmatimactra vitaliana in units 1 to 9 is indicative of the upper Sarmatian Sarmatimactra Zone (Papp, 1954; Harzhauser and Piller, 2004a, b; Piller and Harzhauser, 2005), which roughly spans an interval from 11.9 to 11.6 Ma (Harzhauser and Piller, 2004a). This part of the Sarmatian corresponds to the lower Bessarabian stage of the eastern Paratethys (Popov et al., 2004). The presence of Melanopsis pseudonarzolina places unit 10 in the lower Pannonian (Harzhauser et al., 2002).

2.3 Paleoenvironment

The Piuspuszta section is a lateral equivalent of the Altes Zollhaus section at St Margarethen in Austria, described by Harzhauser and Kowalke (2002) and Piller and Harzhauser (2023). The Altes Zollhaus section is situated 1.2 km NNE of the Piuspuszta section and differs mainly by its thicker limestone beds. Terrestrial and freshwater species and the oligohaline Potamides hartbergensis assemblage, which were described from the Altes Zollhaus section by Harzhauser and Kowalke (2002), are missing at the Piuspuszta section, suggesting a more distal and fully marine position. The mollusk assemblage from the sediment surrounding the bioherms is dominated by the mud whelk Potamides disjunctus. This species is eponymous with the Potamides disjunctus assemblage defined by Harzhauser and Kowalke (2002), which occurred in littoral to shallow sublittoral settings of the Paratethys Sea on sand under marine conditions. Normal marine and even hypersaline conditions were documented by stable isotope data for this assemblage, based on material from the Altes Zollhaus section (Latal et al., 2004). The also enormously abundant mud whelk Tiaracerithium pictum dwelled on the surrounding mudflats (termed Granulolabium bicinctum in Harzhauser and Kowalke, 2002, and Latal et al., 2004). Thus, normal marine or elevated saline coastal marine conditions can be assumed for the phase of bioherm development. These were bracketed by small but rapid oscillations of the relative sea level as indicated by root horizons and erosive boundaries. The frequent caliche layers point to high evaporation due to overall semi-arid conditions during the latest Sarmatian (Piller and Harzhauser, 2005; Koleva-Rekalova et al., 2021). The low amount of siliciclastic material within the peloidal limestones suggest little terrigenous input and oligotrophic conditions. Stable isotope data from upper Sarmatian mollusk shells, collected close to the Piuspuszta section, reveal a marked peak in δ13C. which was interpreted by Harzhauser et al. (2007) as an indication of elevated alkalinity. This is in line with results of Pisera (1995, 1996) and Corneé et al. (2009), who also discussed elevated alkalinity for the Sarmatian Sea based on data from Poland and Hungary.

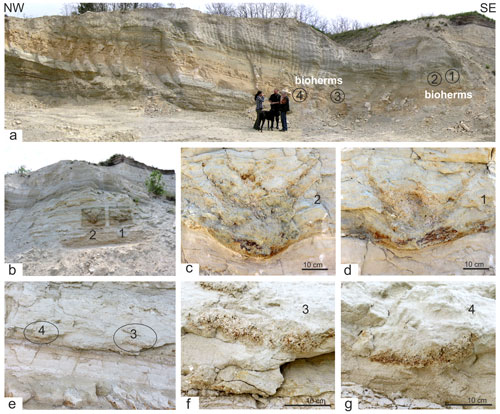

Figure 3(a) Outcrop situation in 2004 and position of the four bioherms (1–4). Bioherms 1 and 2 (b, c, d) in the field before bioherm 1 was excavated. Only lateral parts of bioherms 3 and 4 (e, f, g) are visible.

Four bioherms have been detected during fieldwork in 2004 in close proximity to each other (bioherms 1–4 in Fig. 3). Two of these bioherms were cut more or less centrally, exposing full vertical sections in the field (bioherms 1 and 2 in Fig. 3a–d). The other two bioherms were recorded as marginal sections (Fig. 3e–g). Later stages of excavations documented a size and morphology of these bioherms comparable to those for bioherms 1 and 2. The bioherms have been analyzed and measured during fieldwork, and sediment bulk samples have been taken from each unit as defined in Fig. 2. One of the bioherms (1 in Fig. 3, Fig. 4a–b) was excavated for further analysis in the laboratory. In a first step, the vertical section was smoothed mechanically in the field, and the surface was impregnated with acrylic varnish with an air compressor. After drying of the varnish, the area was covered by gauze bandages, impregnated again with varnish and fixed to a wooden plate. Finally, an about 10–20 cm thick layer of the wall was undercut, tilted with the wooden plate and transported to the Natural History Museum Vienna (NHMW) where it was prepared in the laboratory. This slab is now stored in the Geological-Paleontological Department of the NHMW. All illustrated thin sections (5×5 cm) have been made from samples taken during preparation of this slab. Overview pictures of thin sections were made with a Zeiss Discovery V20. Thin-section studies were carried out with a Leica MZ16 and a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope using ImageAccess ver. 5 rel. 186 for measurements as well as with a Keyence VHX-6000 digital microscope with software for photographic documentation and measurements. The number of vugs in the thin sections was evaluated with ImageJ version 1.53u. Cathodoluminescence analyses were carried out on carbon-coated thin sections with a lumic HC5-LM microscope to differentiate between different carbonate components. Microbialite terminology follows Aitken (1967), Kennard and James (1986), Burne and Moore (1987), Riding (2011), Shapiro (2000), Grey and Awramik (2020), Bourillot et al. (2020), and Vescogni et al. (2022). The salinity classification follows the Venice System (Anonymous, 1958). Na stable isotope data are available from the studied section, but we refer to data from the adjacent outcrop St Margarethen Altes Zollhaus published by Latal et al. (2004), where the lateral equivalent of the Piuspuszta section crops out.

The most striking macroscopic constituents of the bioherms are small serpulid tubes dextrally coiled (mostly below 1 mm in diameter), relatively massive shells with prominent crests and prominent transverse rugae (Fig. 5). The imprints of the lower side document that the tubes have been attached to a hard or at least consolidated substratum. The characteristic morphology allows an identification as Janua heliciformis (Eichwald, 1830) (see Radwanska, 1994) (Fig. 5), which is a widespread and gregarious species in Sarmatian strata of the Paratethys Sea (Boda, 1959; Piller and Harzhauser, 2005).

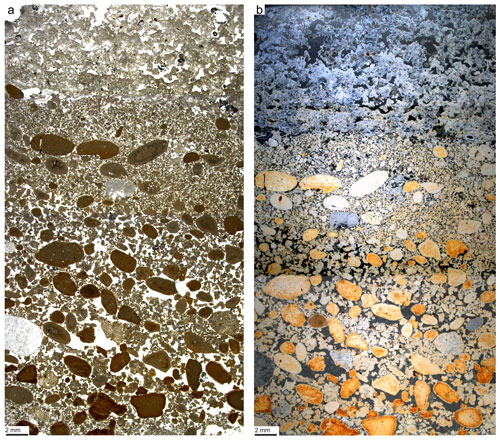

Figure 6Composite of petrographic thin sections documenting the fining-upward sequence of unit 4a and the initial settlement by microbialites with serpulids (a). The same section under dark-field microscopy, documenting the onset of thrombolite growth (blue) versus underlaying sediment (orange) (b).

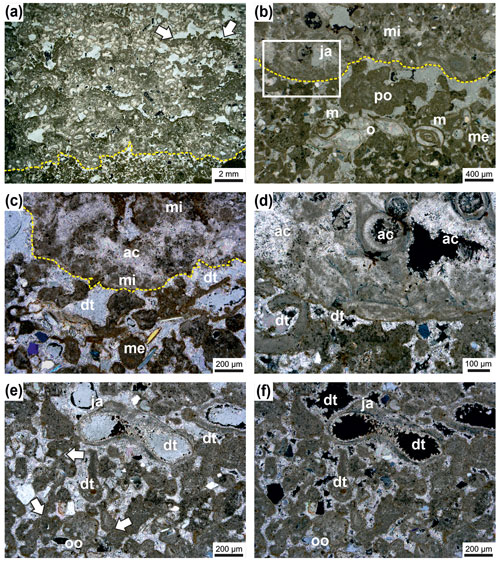

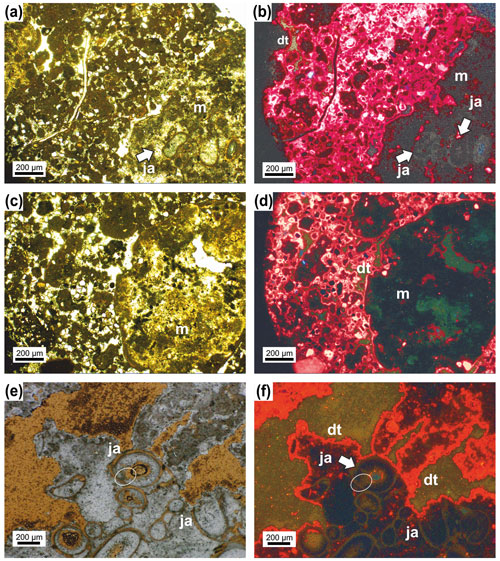

Figure 7Irregular boundary (dashed line) between Janua microclot–acicular cement boundstone in the upper part and the underlying thrombolite of single and polylobate mesoclots (a). In the Janua bioherm the great number of Janua tubes is evident and relatively large open vugs are present, which are indistinctly horizontally arranged. In some vugs geopetal infilling of peloidal mesoclots occurs (arrows). The thrombolitic sediment at the base is rich in miliolid foraminifers. Transmitted polarized light (a). Detail of the irregular boundary (dashed line) with thrombolite at the base with single (me) and polylobate (po) mesoclots and miliolid foraminifers (m) and ostracods (o) (b). In the Janua bioherm a worm tube is cut near the coiling axis (ja) and microclots (mi) (b). Higher magnification of the boundary interval with microclots (mi) and acicular cement (ac) in the Janua bioherm (upper part) and single and polylobate mesoclots (me) and micritic cements and dog-tooth cements (dt) (c). In the thrombolite some terrigenous grains are present; transmitted polarized light (c). Higher magnification of (b) (box) showing microclots and acicular cement (ac) in the upper Janua bioherm and mesoclots and dog-tooth cement (dt) in the thrombolite; transmitted polarized light, crossed nicols (d). Detail of thrombolite in polarized light (e) and under crossed nicols (f) composed of single and polylobate mesoclots and also containing cross-sections of Janua tubes (ja). The mesoclots show micritic meniscus-like cements (arrows), and the remaining pores are cemented by dog-tooth cement (dt). The internal space of the Janua tubes is lined by dog-tooth cement. A few terrigenous grains are also visible. One polylobate grain shows oolitic coating (oo).

4.1 Bioherm morphology

The bioherms are characterized in vertical sections by their outline, which is reminiscent of stacked bowls. The structures attain about 45 cm in diameter and about 40 cm in height (Figs. 3, 4).

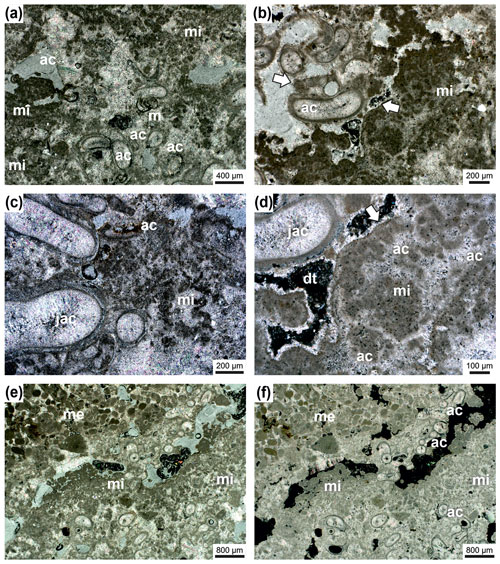

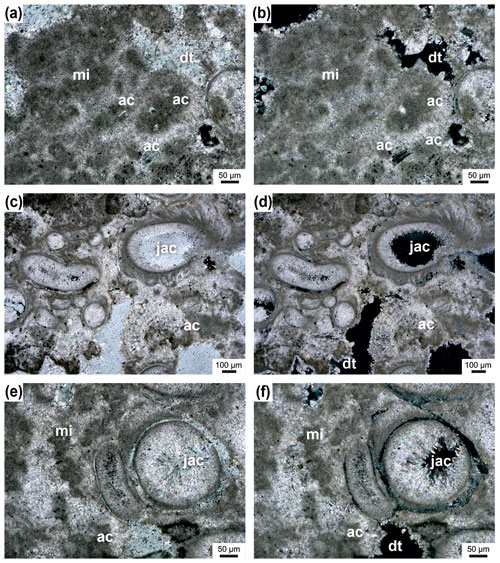

Figure 8Janua microclot–acicular cement boundstone: Janua tubes in cross-section (partly) filled with acicular cement oriented perpendicular to the tube wall (ac) and miliolid foraminifers settling on the outer side of the wall (m) (a). Microclots are very abundant (mi), and also between microclots acicular cement is present. Acicular cement is indicated with (ac); transmitted polarized light (a). Detail with Janua tubes which are filled by acicular cement (ac) and well-developed microclots (mi) (b). Pores and voids are filled with dog-tooth cement (arrow). One Janua tube shows a flat plane of attachment (white arrow). Transmitted polarized light (b). Detail with Janua tubes filled with acicular cement (jac); abundant microclots (mi) also surrounded by acicular cement (ac); transmitted polarized light (c). Detail with Janua tube with acicular cement (jac) and microclot patches (mi) with acicular cement in between (ac) (d). The microclot patch is surrounded by a micritic crust (white arrow); pore space is filled by dog-tooth cement (dt); black areas are empty voids; transmitted polarized light, crossed nicols (d). Lower part of the thin section is composed of Janua tubes in cross-section and microclots (patches) (mi) (e–f). In the upper-right part of the thin section, an infilling with sediment of mesoclots (me) is visible to show the size differences between micro- and mesoclots. Black areas are remnants of grinding powder; transmitted polarized light (e) and transmitted polarized light, crossed nicols (f).

Figure 9In the lower-right corner in (a) is the Janua microbial boundstone visible (m) with sections through the serpulid tubes. On the left side peloidal sediment (mesoclots) is present with various biota. Transmitted light. (b) The same thin-section area as in (a) but under cathodoluminescence (CL) microscope. The serpulid tubes (ja) and the matrix of the boundstone are dark grey in appearance and difficult to separate. The particles in the surrounding sediment show a very pronounced dog-tooth cement (dt) coating which also occurs at the outer margin of the boundstone. (c) The right part of the figure represents the Janua microbial boundstone composed here only of micro- and mesoclots and acicular cement. The left side exhibits peloidal sediment with some terrigenous particles. (d) The same area as (c) but under CL showing the boundstone (m) as nearly structureless (without mesoclots and acicular cements visible) with dog-tooth cement at the margin (dt) and also around the components in the peloidal sediment. (e) Janua microbial boundstone with various sections through the serpulid tubes (ja) and ghost structures of acicular cement (ellipse). (f) The same as in (e) but under CL. The tubes are difficult to visualize. and the area originally filled by acicular cement is composed of larger calcite crystals (ellipse). Well visible is the dog-tooth cement enveloping the boundstone.

4.2 Bioherm composition and embedding sediment

The wall of the bowl-shaped bioherm is built by spirorbid tubes and peloidal, microclotted sediment embedded in a clear to bright yellowish “matrix” with a high number of irregularly shaped vugs with irregular outlines (Fig. 7). No filaments or filamentous structures were detected. The microclots (sensu Frasier and Corsetti, 2003; Harwood and Sumner, 2012; not mesoclots sensu Grey and Awramik, 2020, because of their smaller size) range mainly from 40–120 µm and have a fuzzy outline (Figs. 7–10). They are surrounded by acicular (fibrous) cement (Figs. 7d, 9) and also form microspherolites around the clots (Fig. 10), which is the reason for the light appearance in thin sections. The interior of the spirorbid tubes is generally free of microclots, and the cavities within the tubes are, partly, filled by acicular cement (Figs. 7d, 8). These cements were probably in both cases originally aragonite. The vugs are lined by sparitic dog-tooth cement (Fig. 7d) and lack acicular cement. Serpulid tubes outside the bowl-shaped structure also lack acicular cement and are lined by dog-tooth cement (Figs. 7d, 8d). Under the cathodoluminescence microscope only the last dog-tooth cement generations give a very clear luminescence signal (Fig. 9). The microbial micrite and the acicular cement show no specific signal and can in some places not even be clearly detected under cathodoluminescence (CL) conditions (Fig. 9). This nearly homogenous appearance originated from neomorphism, which produces larger calcite crystals, and the original crystal morphologies are only preserved as “dusty” ghosts. This “recrystallization” may be due to meteoric diagenesis. The boundary between the bioherm wall and the underlying peloidal, mesoclotted sediment is sharp but irregular; the contrast between acicular and dog-tooth cement is also very pronounced under the light microscope (Fig. 7a–c) but not under the luminescence microscope (Fig. 9). Between the “bowl wall” and underlying sediment a narrow gap that is now cement filled does usually exist (Fig. 7b–d), and in some cases an erosional contact may occur (Fig. 6). The vugs are usually randomly arranged; only in the initial basal part of the bioherm does a vague horizontal orientation of large vugs occur (Figs. 6, 7a). Vugs account for up to 21 % in the early stages of bioherm growth. Terminologically the described structures are somewhat difficult: they resemble a thrombolite, but following Shapiro (2000) a thrombolite is a “microbialite composed of a clotted mesostructure (mesoclots)” (Shapiro, 2000, p. 169). The described spirorbid microbialite, however, does not consist of mesoclots but shows a microstructure made of microclots, serpulid tubes and acicular cements (Fig. 8). Microclots are rarely arranged in mesoclots but coincide with the microstructure depicted by Shapiro (2000, Fig. 2).

Figure 10Microclots (mi) surrounded by acicular cement (ac) (a–b); pores are partly filled with dog-tooth cement (dt); transmitted polarized light (a) and transmitted polarized light, crossed nicols (b). Janua tubes filled with acicular cement (jac) and microclots surrounded by acicular cement (ac) (c–f); remaining pores are filled by dog-tooth cement (dt) (c). Transmitted polarized light (e) and transmitted polarized light, crossed nicols (d, f).

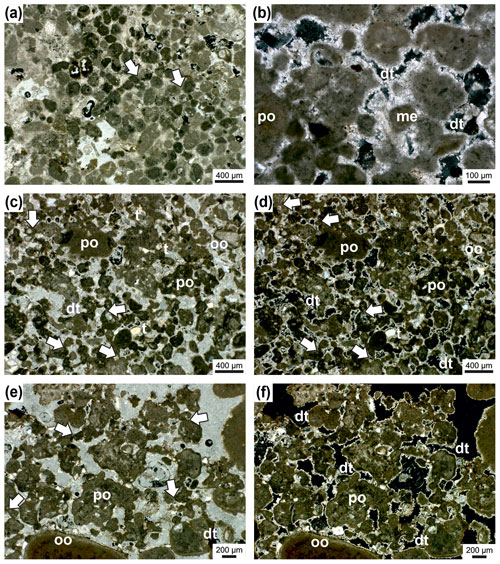

In the surrounding area of the bowl-shaped structure and also within the bowl, the sediment is peloidal but generally coarser grained (mesoclots) as in the structure of the bowl wall (Fig. 9) and contains abundant ostracods, foraminifera (miliolids, rotalids) (Fig. 7a, d), a few mollusks and fish teeth and otoliths as well as coarser-grained, rounded clasts of microbial origin (thrombolitic and stromatolitic) (Fig. 6). Polymictic terrigenous components also occur. The mesoclots reach 2 mm in size and sometimes several millimeters in elongated shapes and are frequently fused into polylobate grains resembling grapestones or aggregate grains (Figs. 7b, 10). In contrast to the substance of the bowl-shaped body, the cements between the surrounding sediments are coarse grained, dog-tooth cements (Fig. 11). The larger components frequently show oolitic or microbial coating (Figs. 7f and 10c, d). The cement in the polylobate components seems to be granular, but acicular shapes cannot be fully excluded. Overall, the sediment is a coarse grainstone (Figs. 6, 10), and the vug area ranges from 10 % to 17 %. Due to these characteristics, the sediment within the “bowls” and in the surrounding areas can be classified as thrombolite.

In summary, the microbialites described herein have to be differentiated into the bowl-shaped structures which are dominated by spirorbid tubes, microclots and acicular cements and a typical thrombolite composed by mesoclots which reflects the surrounding sediment and the sediment within the bowls. The Janua microbialites can be assigned either to “Metazoan-bearing Microbial Structures” or to “Microbial-bearing Metazoan Structures” after the classification of Kennard and James (1986).

Figure 11Thrombolite from the surrounding area of the Janua bioherms. The sediment is composed of peloids (mesoclots) which are connected by micritic cement bridges or meniscus-like structures (arrows) (a); transmitted polarized light. Detail of thrombolite with single (me) and polylobate (po) mesoclots; the pore space around mesoclots is rimmed by dog-tooth cement (dt); transmitted polarized light, crossed nicols (b). Thrombolites of single (m) and polylobate (po) mesoclots. Mesoclots are connected by bridges or meniscus-type micritic cement (arrows) (c–d). A few terrigenous particles (t) are present, and one grain shows oolitic coating; mesoclots are rimmed by dog-tooth cement (dt); transmitted polarized light (c); transmitted polarized light, crossed nicols (d). Detail of thrombolite with mostly polylobate mesoclots (po) which are connected by micritic cement bridges (arrows) (e–f); large peloid at the lower margin shows oolitic coating; pore space is filled by dog-tooth cement (dt). Transmitted polarized light (e); transmitted polarized light, crossed nicols (f).

The spirorbid Janua is a filter-feeding, cosmopolitan serpulid genus with a wide ecological range, occurring from intertidal to deep sublittoral zones (Knight-Jones et al., 1975; Knight-Jones and Knight-Jones, 1977). The genus is not selective concerning its substrate, but settlement is bound to the presence of bacterial films (Kirchman et al., 1981). Thus, the ecological requirements of extant Janua species are not very indicative of paleoecological interpretations. As stated by Ten Hove and van den Hurk (1993, p. 31) “Recent spirorbids never are `reef-forming'. Nevertheless, records of `spirorbids' as contributors to fossil `spirorbid'-algal stromatolites, forming monospecific banks or even `reefs', are numerous”, ranging from the Devonian to the Miocene. Under dispute are, however, their salinity requirements, in particular in the Paleozoic, but “Recent spirorbids are marine, or at most brackish species” (Ten Hove and van den Hurk, 1993, p. 31). In the bioherms studied herein, foraminifers, potamidid gastropods and cardiid bivalves occur in subordinate numbers within the bioherm carbonate but are very frequent in the surrounding sediment, pointing to full marine or elevated saline conditions (e.g., Harzhauser and Kowalke, 2002; Latal et al., 2004; Piller and Harzhauser, 2005).

5.1 Growth dynamics and environmental indications of the bioherms

The morphology of the bioherms suggests four growth stages:

-

The bioherm growth commenced abruptly above a minor erosional surface and is characterized by an open porous fabric with abundant Janua shells and a large number of vugs, which are very vaguely horizontally oriented without forming lamination (Fig. 6). During this initial stage, the bioherms attained about 15–20 cm width (Fig. 4).

-

Subsequently, the bioherms expanded and graded into structures of about 30 cm diameter lacking any macroscopic internal structures. The rapid increase in diameter results in a depressed vase-like outline in the vertical section (Fig. 4).

-

During the next growth stage, the central part of the microbialites continued to grow and widened in diameter. In addition, “branches” developed along the periphery in vertical view. In horizontal view, these branches reflect a continuous ring-like rim of about 5–8 cm width, separated from the central part of the bioherm by sediment. Two phases of ring formation can be observed in bioherm 1 (Fig. 4b and three phases in bioherm 2 Fig. 4d).

-

Finally, the central part of the thrombolites was successively shrinking whilst the peripheral ring increased in diameter. In the terminal phase of growth, only small patches of the ring and/or of the central part persisted, until they finally became completely covered by sediment (Fig. 4e–f).

All bioherms started to grow close above the boundary between units 3 and 4. Unit 3 is formed by weakly solidified peloidal carbonate sand (Fig. 4a), and none of the bioherms is in direct contact with this sediment, although the structures are sunken into unit 3. The boundary between units 3 and 4 is an erosional boundary, and caliche formation can be detected laterally. Unit 3 is abruptly overlain by up to 10 cm of a fining-upward layer of grain supporting fine gravel and peloidal sand with cross-bedding (unit 4a). The topmost part of this unit consists of fine peloidal sand and silt with miliolid foraminifers, mollusks and scattered serpulids. The first microbial film developed on this fine sediment (Figs. 4b, 6). After subaerial exposure of unit 3, indicated by the erosional surface and the laterally occurring caliche, growth of the bioherms started after reflooding, which can be considered a “start-up” phase. This terminology of Neumann and Macintyre (1985) and Macintyre and Neumann (2011) was introduced for coral reefs, indicating their development in respect to rising sea level. In our example, however, the bioherm development mostly depends on the sediment production rate. This is documented by the sediment onlapping on the bioherm during this early stage, indicating that the bioherm was keeping up with sedimentation without protruding much above the sea bottom. Thus, the living part of the bioherms was only slightly elevated over the surrounding sediment surface. Onlapping sand at the terminal part of central body in bioherm 1 indicates a relief of less than 5 cm (Fig. 4 inset). Nevertheless, in reference to the coral reef classification of Neumann and Macintyre (1985) and Macintyre and Neumann (2011), we identify this growth stage as “keep-up” stage because the bioherm was still able to keep up with the pace of sediment production (Fig. 12). During this keep-up stage, the bioherms became too heavy to float on the still-soft sediment and the structures started to sink. Strong post-depositional deformation of units 3 and 4a and of the basal parts of unit 4b documents this process. The uniform growth of coherent, ellipsoidal bioherms changed into the bowl-shaped stage, which may have shown some similarities to microatolls or “thrombolitic microatolls” following the terminology of Burne and Moore (1993) (Fig. 12). The bioherms struggled to keep up with the suddenly increasing subsidence and sediment production, and parts of the central area became buried. Subsequently, the process of sinking ceased, as documented by non-deformed bedding surrounding the bioherms. Unlike coral microatolls, the top of the bioherm never reached the sea surface and projected only a few centimeters above the seafloor but grew laterally and upwards, forming the typical rim of microatolls and dead central areas which became buried (e.g., Meltzner and Woodroff, 2015). In convergence with the reef evolution nomenclature of Neumann and Macintyre (1985) and Macintyre and Neumann (2011), we call this phase the “give-up” stage (Fig. 12). In terms of coral microatolls, this terminal phase could be morphologically classified as “upgrown” microatolls which have low centers encircled by higher living rims, indicating a rising sea level (Woodroffe and Webster, 2014; Meltzner and Woodroff, 2015), but sea level may be of minor importance compared to sediment accumulation in the Sarmatian microbial examples. In contrast to coral microatolls and also to microbial microatolls, no concentric rings could be observed or interpreted in the studied material and also the stacked bowl-shaped structures, which, in fact, resemble budding, as is well known from invertebrates such as sponges and corals, are not present. The stacked pattern of two documented bowl-shaped bioherms showing three growth intervals may be interpreted in two ways: the second bioherm started growing in the center of the underlying older bioherm while this was still growing at the rim or the second bioherm started to grow when the first had already stopped growth. The first case indicates a more or less continuous relative sea level rise and sedimentation rate with the first bioherm already in the give-up stage and the second in the start-up stage. In both cases the growth sequence could be caused by small-scale fluctuations in the relative sea level and also changing sediment production. Finally, during the give-up stage, the sedimentation rate exceeded the capability of the bioherm to keep up, leading to the “escape” growth structures of the terminal phase of bioherm growth (Fig. 12).

The composition of the microbialites exhibits two main fabric types: Janua microclot–acicular cement boundstone and thromboidal (mesoclots) boundstone. The first constitutes the bowl-shaped bioherm; the latter represents the surrounding sediment and the bowl infill. The Janua microclot–acicular cement boundstone can be clearly related to a euhaline to elevated saline environment indicated by the mass occurrences of Janua tubes and the acicular cements (see also below). The acicular cements surround the microclots producing microspherulites and solidify the Janua microclot framework. Since the nearly planispiral tubes of Janua produced imprints in the boundstone, its (part) solidification is documented. The lack of filamentous microbial structures may indicate that coccoid Cyanobacteria have been the major microbial constituents in the shallow subtidal setting in accordance with the description by Suosaari et al. (2016) from Shark Bay, Western Australia. The sediment outside the bowl is a thrombolite constructed by mesoclots which are loosely bound by micritic cement, forming not only single peloids but also polylobate, grapestone-type particles. Within and besides the mesoclots, foraminifera, mollusks and also ooids occur, demonstrating the marine environment. The particles are also connected with micritic meniscus-like cements frequently forming bridges over larger distances. This sediment may have formed a cohesive microbial mat stabilizing the substrate and grew rapidly upwards penecontemporaneously with the bowl structure. Not only the interparticle spaces but also space within the Janua tubes and vugs is lined by dog-tooth cements. These cements indicate formation in a phreatic environment, mostly marine phreatic but also meteoric phreatic (e.g., Flügel, 2010; Andrieu et al., 2017).

5.2 Serpulid microbialites in the Paratethys Sea

Microbialites with serpulids and bryozoans have been frequently described from the lower Sarmatian of the central Paratethys (e.g., Pikija et al., 1989; Bucur et al., 1992; Friebe, 1994a, b; Harzhauser and Piller, 2004a, b; Piller and Harzhauser, 2005; Cornée et al., 2009; see Piller and Harzhauser, 2023, for review) and from the Volhynian and Bessarabian (Middle and Upper Miocene) of the eastern Paratethys (e.g., Andrussow, 1909–1912; Andrusov, 1936; Pisera, 1996; Saint Martin and Pestrea, 1999; Daoud et al., 2006; Jasionowski, 2006; Taylor et al., 2006; Studencka and Jasionowski, 2011; Górka et al., 2012; Goncharova and Rostovtseva, 2009; Jasinowski et al., 2006). But all these bioherms differ considerably from the bioherms discussed herein by the dominance of bryozoans, such as Cryptosula and Schizoporella and near absence of microclots and acicular cement. In addition, the serpulids are represented by Hydroides, a serpuline, instead of Janua, a spirorbine. Modern counterparts of such bioherms have been termed bryostromatolites by Harrison et al. (2021), and Piller and Harzhauser (2023) applied this term to the widespread lower Sarmatian bioherms. The driving force triggering the development of these Hydroides bryostromatolites was considerable eutrophication (Piller and Harzhauser, 2023). In addition, polyhaline conditions prevailed, to which Hydroides and the bryozoans have adapted (Piller and Harzhauser, 2023). These environmental conditions are in strong contrast to the probably oligotrophic and fully marine to elevated saline conditions in which the Janua microbialites formed. Comparable structures are rarely reported from Paratethyan deposits. Possible occurrences are those by Hoernes (1898, p. 60) and Papp (1956, p. 58 f.), who described “Spirorbiskalke” (Spirorbis limestone) represented by elliptical structures of up to 40 cm with dominating spirorbid tubes in an (unspecified) algal limestone. Koleva-Rekalova et al. (2021) documented several elliptical to circular serpulid bioherms from the Bessarabian of NE Bulgaria of up to 40 cm diameter. Based on the illustrated thin sections, the serpulids in these bioherms are rich in Janua and their tubes are filled by fibrous cements (not sediments as mentioned in Koleva-Rekalova et al., 2021), which matches the Janua microbialites described herein. Interestingly, these bioherms are also sunken into the underlaying sediment due to their weight (Koleva-Rekalova et al., 2021, their Fig. 1a).

The reason for the scarce fossil record of upper Sarmatian microbialites is that only comparatively few of the uppermost Sarmatian deposits of the Sarmatimactra Zone are preserved in the central Paratethys, due to considerable erosion at the Sarmatian–Pannonian boundary (Harzhauser et al., 2020). The lower Sarmatian deposits with Hydroides bryostromatolites, in contrast, are widespread and well preserved.

5.3 Modern and fossil analogues

Typical morphologies of extant microbialites range from domal, discoidal and tabular to ridges and extensive platforms (Siqueiros-Beltrones, 2008; Jahnert and Collins, 2012; Suosaari et al., 2016; Louyakis et al., 2017; Paul et al., 2018, 2021). Numerous Neogene to present-day thrombolite-bearing deposits have been described in the literature.

The classical modern microbialite occurrences in The Bahamas and in Shark Bay, Australia, contain well-studied stromatolites and thrombolites (e.g., Dill et al., 1986; Reid et al., 1995, 2000; Andres and Reid, 2006; Planavsky and Ginsburg, 2009; Jahnert and Collins, 2012; Suosaari et al., 2016). Microbialites in Hamelin Pool in Shark Bay show variation in morphologies clearly related to their occurrence from the upper intertidal to the shallow subtidal environment (Jahnert and Collins, 2012). The deepest subtidal thrombolites occur down to 6 m water depth and are represented by “non-laminated cryptomicrobial (Cerebroid) structures” and “Microbial Pavement … with tabular and blocky surface morphologies” (Jahnert and Collins, 2012, p. 127). The cerebroid types contain abundant serpulid skeletons and fibrous aragonite cement (Jahnert and Collins, 2012, their Figs. 13d and 15k, l). Suosaari et al. (2016) also deal with microbialites in Hamelin Pool and focus not only on microbial mat communities but also on pervasively precipitated microbial micrite, which are all built of aragonite (p. 8), but acicular aragonite cements also occur (Fig. 7f). Although the results of the various authors do not fully coincide, the subtidal microbialites (cerebroids) contain abundant serpulids and acicular aragonite cement (Jahnert and Collins, 2012) and clearly show a high amount of precipitated micrite (e.g., as clots) and also aragonitic cements (Suosaari et al., 2016). The lack of filamentous microbial carbonates in the Sarmatian example may reflect the dominance of coccoid Cyanobacteria as described for subtidal microbialites in Shark Bay (Suosaari et al., 2016, p. 5). The microbialites in Shark Bay are not direct analogues of the Sarmatian microbialites, but the serpulid-rich structures in shallow subtidal settings, abundant micrite precipitation and aragonite cement are features which show strong similarities. The best-known subtidal microbialites from the Adderly tidal channel at the Great Bahama Bank also show very similar internal structures with a thrombolitic fabric of clots and micritic and fibrous aragonite cements at both the microscale and mesoscale (Planavsky and Ginsburg, 2009, their Figs. 10, 12). Similar structures are also found in the intertidal microbialites at Highbourne Cay, The Bahamas (Reid et al., 1999, 2000; Myshrall et al., 2010).

A modern example containing well-developed thrombolites is reported from the southern shore of the Persian Gulf (alternatively called the Arabian Gulf) close to Abu Dhabi, the United Arab Emirates (Paul et al., 2018, 2021). The thrombolites occur in a sabkha setting with water salinities of 75–93 psu, and morphologies include domes (5–20 cm in width and a relief of 10–25 cm above a hard ground) and bands. Internally, the domes represent stromatolites at the base overlain by thrombolites. Grains are coated by an isopachous acicular aragonite cement with fibrous needles oriented perpendicular to the grain surface (Paul et al., 2018, 2021). The skeletal assemblage is dominated by foraminifers and ostracods and contains subordinate bivalves. Although the growth morphology and the intertidal setting are not comparable to the Sarmatian examples described herein, the microclots and acicular cement (Paul et al., 2021, their Fig. 12b–d) are strikingly similar, and it is a hypersaline environment.

Microbialitic bioherms described from Mediterranean lagoons of southern France are not analogues for the microbialites described herein and also not for other Sarmatian microbialites because Sarmatian bioherms show “mainly clotted and/or peloidal micrite … and, also, fibrous calcite rims around serpulid tubes” (Saint Martin and Saint Martin, 2015, p. 67).

Interesting examples of metazoan and microbial bioherms are well documented from Mediterranean caves (e.g., Guido et al., 2017, 2022; Rosso et al., 2021). These are known as biostalactites and are composed of a variety of metazoans besides microbialites. In some examples, the core of the biostalactites is built by a serpulid boundstone dominated by Protula tubes, but microbialite/skeletal boundstones and pure microbialite boundstones also occur. These structures are comparable with the Sarmatian thrombolites in their microstructure of clotted peloidal limestones and fibrous cements; however, the metazoan diversity is comparably high and even serpulids are diverse. In addition, the environmental conditions are completely different because these bioherms all form in caves and the microbialites are built by heterotrophic bacteria (Guido et al., 2022).

Two well-studied modern examples of microbial microatolls will be cited here: Lake Clifton, Western Australia, and Bacalar Lagoon, Mexico. In Lake Clifton thrombolitic microbialites showing tabular or concentric ring-shaped growth of up to 50 cm high developed across a shallow platform which is called reef platform due to the occurrence of the microbial microatolls (Burne and Moore, 1993). The morphology of the thrombolites varies along the platform depending on proximal or distal location. Lake Clifton is a hypo- to hypersaline lake, and the microatolls occur in water depth of mostly less 1 m (Burne and Moore, 1993). The water level fluctuates approximately 1 m seasonally, and salinity ranges between 15 and 40 psu (Moore and Burne, 1994); however, summer salinity changed between 1983 and 1999 from 29 to 48 psu (Konishi et al., 2001). Although metazoans are reported from the thrombolites, none of them were dominant (Moore and Burne, 1994; Konishi et al., 2001). Cementation resulted from aragonite crystals. Despite some morphologic similarities between the Sarmatian Janua microbialite and the Lake Clifton thrombolites, the driving processes seem to be different. Although the Janua thrombolites developed in a very shallow marine environment, no sedimentological features indicate that the bioherms developed in the intertidal zone, being limited in growth by the low tide level. The central biostrome areas became abandoned due to sedimentation load and not due to emergence. The Bacalar Lagoon, Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico, harbors the largest known Holocene freshwater microbialite system (Gischler et al., 2008, 2011; Yanez-Montalvo et al., 2020). The thrombolitic microbialites include domes, ledges and oncolites; the domes reach a size up to 3 m in height and diameter; and they occur down to 3 m water depth. The maximum depth of the lagoon reaches 15 m, and the water level is fairly constant with annual fluctuations of 30 cm (Gischler et al., 2011). In the southern part of the lagoon, large microatolls (called mini-atolls by Gischler et al., 2011) are present, reflecting a variety of morphologies not only with concentric flat tops but also with deep central depressions and cone-shaped structures. Mineralogically the microbialite cements are made of calcite (Gischler et al., 2008). Both locations (Lake Clifton, Bacalar Lagoon) exhibit similarities in growth morphology containing microatolls: in Lake Clifton marine-derived saline lake water shows elevated calcium carbonate contents, and in the Bacalar Lagoon the microbialites occur in freshwater, but they also show an elevated carbonate content (Gischler et al., 2008, 2011) and the biotic composition is different. Compared to the Sarmatian bioherms, no major content of serpulids or other dominant metazoans is present.

Another distantly similar example is Holocene serpulid stromatolites from SE Tunisia. These developed in a lagoonal setting with high salinity and high evaporation and were associated with large populations of the mud whelk Pirenella conica (Davaud et al., 1994). Like in Piuspuszta, the bioherms are associated with miliolid and rotalid foraminifers and “Spirorbis-type” serpulids. These structures differ, however, in the sequence of growth in which stromatolites overgrow serpulid bioherms, but the microbialites are very similar in being composed of clotted fabric and fan-shaped and aragonitic microspherulites (Davaud et al., 1994, their Fig. 9).

The famous serpulid tufa bioherms in the Dominican Republic described by Winsor et al. (2012) are only superficially reminiscent of the Sarmatian bioherms and differ considerably in their meter-scale dimension and various shapes, which are not represented in our examples. The petrographic description is not detailed enough for a direct comparison, and also terminology used is not comparable to other examples. The bioherms formed during the Holocene in restricted hyposaline lakes along the Enriquillo Seaway (Winsor et al., 2012).

Microbialites with a wide range of morphologies and dimensions with various fabric types partly with a high contribution of serpulids occur in Messinian oolite shoals in southeastern Spain (Feldmann and McKenzie, 1997; Goldstein et al., 2013; Bourillot et al., 2020). Like the Sarmatian bioherms, these bioherms formed in a shallow-water environment in less than 10 m water depth but below the intertidal zone under normal marine to hypersaline conditions (Feldmann and McKenzie, 1997; Bourillot et al., 2020). Also, the meso- and microscale fabrics are similar. In contrast to the Sarmatian thrombolites, these Messinian Mediterranean bioherms also contain calcareous red algae and corals such as Porites and Tarbellastrea. In addition, they attain larger dimensions and are associated with Porites patch reefs and stromatolites, forming ecological successions related to salinity fluctuations (Feldmann and McKenzie, 1997). Unsurprisingly similar to the Spanish examples are upper Messinian microbialites from southern Italy, which also exhibit various morphologies; various fabrics; and diverse biota, including corals, coralline algae and serpulids (Vescogni et al., 2022). Thus, the Messinian microbialites are comparable with the Sarmatian bioherms in terms of their subtidal building environments, in meso- and microfabrics, but differ in size and biotic composition and complexity of depositional environments.

None of the microbialites described in the literature display the stacked bowl-shaped vertical section of the Sarmatian biostromes from NW Hungary as described herein. Fabric composition as well as microbial and acicular cements is in some cases conformable as are subtidal, normal marine to hypersaline conditions and high alkalinity, but morphology does not fit. Overall and in accordance with Piller and Harzhauser (2023), the entire shallow-water area in the late Sarmatian of the Vienna Basin (and eventually in all the Paratethys) was dominated by microbial sediments because most of the widespread oolites are also microbially bound as are the bioherms (Piller and Harzhauser, 2023).

In the central Paratethys, Janua microbialites were restricted to the late Sarmatian, whereas bryostromatolites occurred during the early Sarmatian. This exclusive stratigraphic succession coincided with a change from polyhaline eutrophic to normal marine, elevated saline or even hypersaline conditions caused by climatic warming and enhanced aridity.

The macroscopic morphology of the Janua bioherms suggests a succession of three growth stages ranging from a start-up stage with small, vaguely laminated bioherms grading into broad bowl-like morphologies (keep-up stage) when the bioherms managed to balance the sedimentation rate. The third stage is characterized by a circular rim and a narrow central protrusion. During this stage, parts of the central part of the bioherms became covered by sediment, limiting the area of biologically active zones. Two or three phases forming a collar-like structure from the central body are observed in the Hungarian bioherms, resulting in a characteristic stacked bowl-shaped vertical section. During the final phase, the thrombolites struggle to keep up with the sedimentation, resulting in successive covering of the bioherm. During this give-up stage, the bioherms form small isolated escape structures and finally become buried by sediment.

The internal composition of the bioherms represents a Janua microclot–acicular cement boundstone, whereas the surrounding and bowl infilling sediments are thrombolites consisting of peloids and polylobate particles (mesoclots) cemented synsedimentarily by micritic cements. Remaining interparticle space and vugs are later cemented by dog-tooth cements.

Only two occurrences of Janua bioherms are known to us, the one in NW-Hungary described herein and one in NE Bulgaria. In both cases, the bioherms are synsedimentarily sunken in the underlaying sediment, indicating that the bioherms started to subside due to their increasing weight. For the Janua bioherms described herein, this sinking seems to have triggered the peculiar bowl shape, whereas the Bulgarian bioherms could keep up with the relatively low sedimentation rate and formed domal structures. The bowl-shaped growth form of the Hungarian bioherm is a unique feature. The upper Sarmatian bioherms grew in a very shallow subtidal environment and have not been restricted in vertical growth by the low tide level. Instead, the bioherms formed during a minor transgressive pulse in normal marine or elevated saline waters with elevated alkalinity. Janua bioherms might have been much more common in Sarmatian deposits but might have been confused with the much more widespread and better-documented lower Sarmatian bryostromatolites.

Both the serpulid microbialites and the surrounding peloidal sediment are expressions of excessive microbial activity. Similarly, the widespread late Sarmatian oolites are microbially bound. Therefore, we assume that the entire shallow-water area of the Paratethys Sea was dominated by microbial sediments from ∼12.0 to 11.6 Ma, coinciding with a phase of warm, semi-arid climate and probably oligotrophic waters.

All material is stored in the collections of the Geological-Paleontological Department of the Natural History Museum Vienna and can be studied upon request.

All authors were responsible for data acquisition and interpretation and wrote the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We are greatly indebted to Daniela Gallhofer and Simon Schretter (both University of Graz) for their help with the cathodoluminescence microscope. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their positive and constructive reviews and suggestions. We thank Cindy De Jonge (ETH Zürich) for her excellent editorial work.

This paper was edited by Cindy De Jonge and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Aitken, J. D.: Classification and environmental significance of cryptalgal limestones and dolostones, with illustrations from the Cambrian and Ordovician of southwestern Alberta, J. Sediment. Petrol., 37, 1163–1178, https://doi.org/10.1306/74D7185C-2B21-11D7-8648000102C1865D, 1967.

Andres, M. S. and Reid, R. P.: Growth morphologies of modern marine stromatolites: A case study from Highborne Cay, Bahamas. Sediment. Geol., 185, 319–328, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2005.12.020, 2006.

Andrieu, S., Brigaud, B., Barbarand, J., and Lasseur, E.: The complex diagenetic history of discontinuities in shallow-marine carbonate rocks: New insights from high-resolution ion microprobe investigation of δ18O and δ13C of early cements, Sedimentology, 65, 360–399, https://doi.org/10.1111/sed.12384, 2017.

Andrusov, N.: Vergleich der fossilen Bryozoen-Riffe der Halbinseln Kertsch und Taman mit anderen riffartigen zoogenen Bildungen, Bulletin de l'Association Russe pour les Recherches Scientifiques a Prague, IV (IX), Section des sciences naturelles et mathématiques, 22, 113–123, 1936.

Andrussow, N.: Die fossilen Bryozoenriffe der Halbinsel Kertsch und Taman, Selbstverlag, Kiew, 1–144, 1909–1912.

Boda, J.: Das Sarmat in Ungarn und seine Invertebraten-Fauna, A magyarországi szarmata emelet és gerinctelen faunája, Das Sarmat in Ungarn und seine Invertebraten-Fauna, Magyar Állam, Földt. Int. Évkön, 47, 862 pp., http://real-j.mtak.hu/18637/1/00098_EPA03274_mafi_evkonyv_1959_03.pdf (last access: 31 November 2023), 1959.

Anonymous: The Venice System for the classification of marine waters according to salinity, Limnol. Oceanogr., 3/3, 346–347, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1958.3.3.0346, 1958.

Bourillot, R., Vennin, E., Dupraz, C., Pace, A., Foubert, A., Rouchy, J.-M., Patrier, P., Blanc, P., Bernard, D., Lesseur, J., and Visscher, P. T.: The record of environmental and microbial signatures in ancient microbialites: The Terminal Carbonate Complex from the Neogene Basins of Southeastern Spain, Minerals, 10, 276, https://doi.org/10.3390/min10030276, 2020.

Bucur, I. I., Nicorici, E., Huică, I., and Ionesi, B.: Calcareous microfacies in the Sarmatian deposits from Romania, Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai, Chemia, 2, 9–16, 1992.

Bukowski, K.: Badenian saline sedimentation between Rybnik and Dębica based on geochemical, isotopic and radiometric research, Rozprawy, Monograf, 236, 1–184, Wydawnictwa AGH, Kraków, ISBN 978-83-7464-439-9, 2011.

Burne, R. V. and Moore, L. S.: Microbialites: Organosedimentary deposits of benthic microbial communities, Palaios, 2, 241–254, 1987.

Burne, R. V. and Moore, L. S.: Microatoll microbialites of Lake Clifton, Western Australia: morphological analogues of Cryptozoön proliferum Hall, the first formally-named stromatolite, Facies, 29, 149–168, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02536926, 1993.

Cornée, J.-J., Moissette, P., Saint Martin, J.-P., Kázmér, M., Tóth, E., Görög, Á., Dulai, A., and Müller, P.: Marine carbonate systems in the Sarmatian (Middle Miocene) of the Central Paratethys: the Zsámbék Basin of Hungary, Sedimentology, 56, 1728–1750, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.2009.01055.x, 2009.

Daoud, H., Bucur, I. I., and Bruchental, C.: Microbialitic structures in the Sarmatian carbonate deposits from Şimleu Basin, Romania. Studia Universitatis Babeş-Bolyai, Geologia, 51, 3–13, 2006.

Davaud, E., Strasser, A., and Jedoui, Y.: Stromatolite and serpulid bioherms in a Holocene restricted lagoon (Sabkha el Melah, Southeastern Tuisia), in: Phanerozoic Stromatolites II, edited by: Bertrand-Sarfati, J. and Monty, C., Kluwer Academic Publishing, Dordrecht, 131–151, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-1124-9_6, 1994.

De Leeuw, A., Bukowski, K., Krijgsman, W., and Kuiper, K. F.: Age of Badenian salinity crisis; impact of Miocene climate variability on the circum-Mediterranean region, Geology, 38, 715–718, https://doi.org/10.1130/G30982.1, 2010.

Dill, R. F., Shinn, E. A., Jones, A. T., Kelly, K., and Steinen, R. P.: Giant subtidal stromatolites forming in normal salinity waters, Nature, 324, 55–58, https://doi.org/10.1038/324055a0, 1986.

Edgcomb, V., Bernhard, J., Summons, R., Orsi, W., Beaudoin, D., and Visscher, P. T.: Active eukaryotes in microbialites from Highborne Cay, Bahamas, and Hamelin Pool (Shark Bay), Australia, ISME J., 8, 418–429, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.130, 2014.

Feldmann, M. and McKenzie, J. A.: Messinian stromatolite-thrombolite associations, Santa Pola, SE Spain: an analogue for the Palaeozoic?, Sedimentology, 44, 893–914, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3091.1997.d01-53.x, 1997.

Flügel, E.: Microfacies of Carbonate Rocks. Analysis, Interpretation and Application, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, XXIII+984 p., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-03796-2, 2010.

Fraiser, M. and Corsetti, F.: Neoproterozoic carbonate shrubs: interplay of microbial activity and unusual environmental conditions in post-Snowball Earth oceans, Palaios, 18, 378–387, https://doi.org/10.1669/0883-1351(2003)018<0378:NCSIOM>2.0.CO;2, 2003.

Friebe, J. G.: Serpulid-bryozoan-foraminiferal biostromes controlled by temperate climate and reduced salinity: Middle Miocene of the Styrian Basin, Austria, Facies, 30, 51–62, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02536889, 1994a.

Friebe, J. G.: Gemischt siliziklastisch-karbonatische Abfolgen aus dem Oberen Sarmatium (Mittleres Miozän) des Steirischen Beckens, Jahrbuch der Geologischen Bundesanstalt, 137/2, 245–274, 1994b.

Gischler, E., Gibson, M. A., and Oschmann, W., Giant Holocene freshwater microbialites, Laguna Bacalar, Quintana Roo, Mexico, Sedimentology, 55, 1293–1309, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.2007.00946.x, 2008.

Gischler, E., Golubic, S., Gibson, M. A., Oschmann, W., and Hudson, J. H.: Microbial mats and microbialites in the freshwater laguna Bacalar, Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico, in: Advances in Stromatolite Geobiology, edited by: Reitner, J., Quéric, N.-V., and Arp, G., Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences, 131, 187–205, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-10415-2_13, 2011.

Goldstein, R. H., Franseen, E. K., and Lipinski, C. J.: Topographic and sea level controls on oolite-microbialite-coralgal reef sequences: The terminal carbonate complex of southeast Spain, AAPG Bull., 97/11, 1997–2034, https://doi.org/10.1306/06191312170, 2013.

Goncharova, I. A. and Rostovtseva, Y. V.: Evolution of organogenic carbonate buildups in the Middle through Late Miocene of the Euxine-Caspian Basin (Eastern Paratethys), Paleontol. J., 43/8, 866–876, https://doi.org/10.1134/S0031030109080048, 2009.

Górka, M., Studencka, B., Jasionowski, M., Hara, U., Wysocka, A., and Poberezhskyy, A.: The Medobory Hills (Ukraine): Middle Miocene reef systems in the Paratethys, their biological diversity and lithofacies, Biuletyn Państwowego Instytutu Geologicznego, 449, 147–174, https://www.pgi.gov.pl/en/dokumenty-przegladarka/publikacje-2/biuletyn-pig/1293-biul449-gorka/file.html (last access 31 November 2023), 2012.

Grey, K. and Awramik, S. M.: Handbook for the study and description of microbialites, Geological Survey of Western Australia, Bulletin, 147, X+278 pp., Handbook for the study and description of microbialites, ISBN 978-1-74168-862-7, ISSN 0085-8137, 2020.

Guido, A., Jimenez, C., Achilleos, K., Rosso, A., Sanfilippo, R., Hadjioannou, L., Petrou, A., Russo, F., and Mastandrea, A.: Cryptic serpulid-microbialite bioconstructions in the Kakoskali submarine cave (Cyprus, Eastern Mediterranean), Facies, 63, 21, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10347-017-0502-3, 2017.

Guido, A., Rosso, A., Sanfilippo, R., Miriello, D., and Belmonte, G.: Skeletal vs microbialite geobiological role in bioconstructions of confined marine environments, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 593, 110920, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2022.110920, 2022.

Harrison, G. W. M., Claussen, A. L., Schulbert, C., and Munneke, A.: Modern brackish bryostromatolites (“bryoliths”) from Zeeland (Netherlands), Palaeobiol. Palaeoenviron., 102, 89–101, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12549-021-00490-3, 2021.

Harwood, C. L. and Sumner, D. Y.: Origins of microbial microstructures in the Neoproterozoic Beck Spring Dolomite: variations in microbial community and timing of lithification, J. Sediment Res., 82, 709–722, https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2012.65, 2012.

Harzhauser, M.: Eisenstadt-Sopron Basin, in: The lithostratigraphic units of Austria: Cenozoic Era(them), edited by: Piller, W. E., Friebe, J. G., Gross, M., Harzhauser, M., Van Husen, D., Koukal, V., Krenmayr, H. G., Krois, P., Nebelsick, J. H., Ortner, H., Piller, W. E., Reitner J. M., Roetzel, R., Rögl, F., Rupp, C., Stingl, V., Wagner, L., and Wagreich, M., Abhandlungen der Geologische Bundesanstalt, 76, 181–183, 2022.

Harzhauser, M. and Kowalke, T.: Sarmatian (Late Middle Miocene) gastropod assemblages of the Central Paratethys, Facies, 46, 57–82, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02668073, 2002.

Harzhauser, M. and Piller, W. E.: The Early Sarmatian – hidden seesaw changes, Cour. Forsch. Senck., 246, 89–111, 2004a.

Harzhauser, M. and Piller, W. E.: Integrated stratigraphy of the Sarmatian (Upper Middle Miocene) in the western Central Paratethys, Stratigraphy, 1, 65–86, 2004b.

Harzhauser, M. and Piller, W. E.: Benchmark data of a changing sea – Palaeogeography, Palaeobiogeography and Events in the Central Paratethys during the Miocene, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 253, 8–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.03.031, 2007.

Harzhauser, M., Kowalke, T., and Mandic, O.: Late Miocene (Pannonian) gastropods of Lake Pannon with special emphasis on early ontogenetic development, Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums Wien, 103A, 75–141, 2002.

Harzhauser, M., Piller, W. E., and Latal, C.: Geodynamic impact on the stable isotope signatures in a shallow epicontinental sea, Terra Nova, 19, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3121.2007.00755.x, 2007.

Harzhauser, M., Peckmann, J., Birgel, D., Draganits, E., Mandic, O., Theobalt, D., and Huemer, J.: Stromatolites in the Paratethys Sea during the Middle Miocene climate transition as witness of the Badenian salinity crisis, Facies, 60/2, 429–444, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10347-013-0391-z, 2014.

Harzhauser, M., Kranner, M., Mandic, O., Strauss, P., Siedl, W., and Piller, W. E.: Miocene lithostratigraphy of the northern and central Vienna Basin (Austria), Aust. J. Earth Sci., 113, 169–200, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4471-6655, 2020.

Hoernes, R.: Sarmatische Conchylien aus dem Oedenburger Comitat, Jahrbuch der Geologischen Bundesanstalt, 47, 57–94, http://opac.geologie.ac.at/wwwopacx/wwwopac.ashx?command=getcontent&server=images&value=JB0471_057_A.pdf (last access: 31 November 2023), 1898.

Jahnert, R. J. and Collins, L. B.: Characteristics, distribution and morphogenesis of subtidal microbial systems in Shark Bay, Aust. Mar. Geol., 303–306, 115–136, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2012.02.009, 2012.

Jasionowski, M.: Facies and geochemistry of lower Sarmatian reefs along the northern margins of the Paratethys in Rozticze (Poland) and Medobory (Ukraine) regions: Paleoenvironmental implications, Przeglad Geologiczny, 54, 445–454, 2006.

Jasionowski, M., Peryt, D., and Peryt, T. M.: Neptunian dykes in the Middle Miocene reefs of western Ukraine: preliminary results, Geol. Q., 56/4, 881–894, 2006.

Johnson, M. E., Ledesma-Vázquez, J., Backus, D. H., and González, M. R.: Lagoon microbialites on Isla Angel de la Guarda and associated peninsular shores, Gulf of California (Mexico), Sediment. Geol., 263–264, 76–84, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2011.09.006, 2012.

Kennard, J. M. and James, N. P.: Thrombolites and Stromatolites: two distinct types of microbial structures, Palaios, 1/5, 492–503, https://doi.org/10.2307/3514631, 1986.

Khodadad, C. L. and Foster, J. S.: Metagenomic and metabolic profiling of nonlithifying and lithifying stromatolitic mats of Highborne Cay, The Bahamas, PLOS ONE, e38229, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038229, 2012.

Kirchman, D., Graham, S., Reish, D., and Mitchell, R.: Bacteria induce settlement and metamorphosis of Janua (Dexiospira) brasiliensis Grube (Polychaeta: Spirorbidae), J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol., 56, 153–163, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0981(81)90186-6, 1981.

Knight-Jones, P. and Knight-Jones, E. W.: Taxonomy and ecology of British Spirorbidae (Polychaeta), J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK, 57, 453–499, https://doi.org/10.1017/S002531540002186X, 1977.

Knight-Jones, P., Knight-Jones, E. W., and Kawahara, T.: A review of the genus Janua, including Dexiospira (Polychaeta: Spirorbinae), Zool. J. Linn. Soc.-Lond., 56, 91–129, https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1096-3642.1975.TB00812.X, 1975.

Koleva-Rekalova, E., Nikolov, P., Yaneva, M., Ognjanova-Rumenova, N., Nikolov, N., and Donkova, Y.: The Bessarabian (Sarmatian) serpulid bioherms – an indicator of specific climatic conditions (Topola Formation, Northeastern Bulgaria), Rev. Bulgarian Geol. Soc., 82, 112–114, 2021.

Konishi, Y., Prince, J., and Knott, B.: The fauna of thrombolitic microbialites, Lake Clifton, Western Australia, Hydrobiologia, 457, 39–47, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012229412462, 2001.

Kranner, M., Harzhauser, M., Mandic, O., Strauss, P., Siedl, W., and Piller, W. E.: Trends in temperature, salinity and productivity in the Vienna Basin (Austria) during the early and middle Miocene, based on foraminiferal ecology, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 581, 110640, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110640, 2021.

Latal, C., Piller, W. E., and Harzhauser, M.: Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction by stable isotopes of Middle Miocene Gastropods of the Central Paratethys, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 211, 157–169, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.05.003, 2004.

Louyakis, A. S., Mobberley, J. M., Vitek, B. E., Visscher, P. T., Hagan, P. D., Reid, R. P., Kozdon, R., Orland, I. J., Valley, J. W., Planavsky, N. J., Casaburi, G., and Foster, J. S.: A study of the microbial spatial heterogeneity of Bahamian thrombolites using molecular, biochemical, and stable isotope analyses, Astrobiology, 17/5, 413–430, https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2016.1563, 2017.

Macintyre, I. G. and Neumann, A. C.: Reef classification, response to sea level rise, in: Encyclopedia of Modern Coral Reefs, edited by: Hopley, D., Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series, Springer, Dordrecht, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2639-2_90, 2011.

Meltzner, A. J. and Woodroffe, C. D.: Coral microatolls, in: Handbook of Sea-Level Research, edited by: Shennan, I., Long, A. J., and Horton, B. P., First Edition, John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 125–145, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118452547, 2015.

Mobberley, J. M., Khodadad, C. L. M., Visscher, P. T., Reid, R. P., Hagan, P., Foster, J. S.: Inner workings of thrombolites: spatial gradients of metabolic activity as revealed by metatranscriptome profiling, Sci. Rep., 5, 12601, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12601, 2015.

Moore, L. S. and Burne, R. V.: The modern thrombolites of Lake Clifton, Western Australia, in: Phanerozoic Stromatolites II, edited by: Bertrand-Sarfati, J. and Monty, C., 3–29, Springer, Dordrecht, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-1124-9_1, 1994.

Myshrall, K. L., Mobberley, J. M., Green, S. J., Vissher, P. T., Havemann, S. A., Reid, R. P., and Foster, J. S.: Biogeochemical cycling and microbial diversity in the thrombolitic microbialites of Highborne Cay, Bahamas, Geobiology, 8, 337–354, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4669.2010.00245.x, 2010.

Neumann, A. C. and Macintyre, I. G.: Reef response to sea-level rise: keep-up, catch-up, or give-up, Proceedings of the Fifth International Coral Reef Congress, Tahiti, Moorea, 27 May–1 June 1985, 3, 105–110, https://research.si.edu/publication-details/?id=95953 (last access: 31 November 2023), 1985.

Palcu, D. V., Tulbure, M., Bartol, M., Kouwenhoven, T. J., and Krijgsman, W.: The Badenian–Sarmatian Extinction Event in the Carpathian foredeep basin of Romania: Paleogeographic changes in the Paratethys domain, Global Planet. Change, 133, 346–358, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2015.08.014, 2015.

Papp, A.: Die Molluskenfauna im Sarmat des Wiener Beckens, Mitteilungen der Geologischen Gesellschaft in Wien, 45/1952, 1–112, https://www.zobodat.at/pdf/MittGeolGes_45_0001-0112.pdf (last access: 31 November 2023), 1954.

Papp, A.: Fazies und Gliederung des Sarmats im Wiener Beckens, Mitteilungen der Geologischen Gesellschaft in Wien, 47, 35–98, https://www.zobodat.at/pdf/MittGeolGes_47_0035-0097.pdf (last access: 31 November 2023), 1956.

Paul, A., Lokier, S. W., Court, W. M., van der Land, C., Andrade, L. L., Dutton, K. D., Sherry, A., and Head, I. M.: Erosion-initiated stromatolite formation in a recent hypersaline sabkha setting (Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates), Earth ArXiv, https://doi.org/10.31223/osf.io/j38h2, 2018.

Paul, A., Lokier, S. W., Sherry, A., Andrade, L. L., Court, W. M., van der Land, C., Dutton, K. D., and Head, I. M.: Erosion-initiated stromatolite and thrombolite formation in a present-day coastal sabkha setting, Sedimentology, 68, 382–401, https://doi.org/10.1111/sed.12783, 2021.

Perrin, C. and Bosellini, F. R.: Paleobiogeography of scleractinian reef corals: changing patterns during the Oligocene–Miocene climatic transition in the Mediterranean, Earth Sci. Rev., 111, 1–24, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EARSCIREV.2011.12.007, 2012.

Pikija, M., Šikić, K., Tišljar, J., and Šikić, L.: Biolititni i prateći karbonatni facijesi sarmata u podrućju Krašić – Ozalj (središnja Hrvatska) (Sarmatian biolithite and associated carbonate deposits in Krašić – Ozalj (central Croatia) – shortened English version), Geol. Vjesnik, 42, 15–28, 1989.

Piller, W. E. and Harzhauser, M.: The Myth of the Brackish Sarmatian Sea, Terra Nova, 17, 450–455, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3121.2005.00632.x, 2005.

Piller, W. E. and Harzhauser, M.: Bryoherms from the lower Sarmatian (upper Serravallian, Middle Miocene) of the Central Paratethys, Facies, 69, 5, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10347-023-00661-y, 2023.

Piller, W. E. and Harzhauser, M.: Foraminiferal reefs of the Paratethys Sea and their paleoecological significance (upper Serravallian, upper Sarmatian, Middle Miocene), Geobiology, under review, 2023.

Pisera, A.: The role of skeletal and non-skeletal components in the Sarmatian (Miocene) reefs of Poland, Public. Serv. Geol. Luxembourg, 29, 81–86, 1995.

Pisera, A.: Miocene reefs of the Paratethys: a review, in: Models for Carbonate Stratigraphy from Miocene Reef Complexes of Mediterranean Regions, edited by: Franseen, E. K., Esteban, M., Ward, W. C., and Rouchy, J.-M., SEPM Concepts in Sedimentology and Paleontology, 5, 97–104, https://doi.org/10.2110/csp.96.01.0097, 1996.

Planavsky, N. and Ginsburg, R. N.: Taphonomy of modern marine Bahamian microbialites, Palaios, 24, 5–17, https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2008.p08-001r, 2009.

Popov, S. V., Rögl, F., Rozanov, A. Y., Steininger, F. F., Shcherba, I. G., and Kováč, M.: Lithological-Paleogeographic maps of the Paratethys, 10 maps Late Eocene to Pliocene, Cour. Forsch. Senck., 250, 1–46, 2004.

Radwańska, U.: Tube-dwelling polychaetes from the Korytnica Basin (Middle Miocene; Holy Cross Mountains, Central Poland), Acta Geol. Pol., 44, 35–81, https://geojournals.pgi.gov.pl/agp/article/view/13654/12095, 1994.

Reid, R. P., Macintyre, I. G., Browne, K. M., Steneck, R. S., and Miller, T.: Modern marine stromatolites in the Exuma Cays, Bahamas: uncommonly common, Facies, 33, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02537442, 1995.

Reid, R. P., Macintyre, I. G., and Steneck, R. S.: A microbialite/algal ridge fringing reef complex, Highborne Cay, Bahamas, Atoll Research Bulletin, 465, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.5479/si.00775630.465.1, 1999.

Reid, R. P., Visscher, P. T, Decho, A. W., Stolz, J. F., Bebout, B. M., Dupraz, C., Macintyre, I. G., Paerl, H. W., Pinckney, J. L., Prufert-Bebout, L., Steppe, T. F., and DesMarais, D. J.: The role of microbes in accretion, lamination and early lithification of modern marine stromatolites, Nature, 406, 989–992, https://doi.org/10.1038/35023158, 2000.

Riding, R.: Microbialites, Stromatolites, and Thrombolites, in: Encyclopedia of Geobiology, edited by: Reitner, J. and Thiel, V., Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series, Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 635–654, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9212-1_196, 2011.

Riegl, B. and Piller, W. E.: Biostromal coral facies – a Miocene example from theLeitha Limestone (Austria) and its actualistic interpretation, Palaios 15, 399–413, https://doi.org/10.1669/0883-1351(2000)015<0399:BCFAME>2.0.CO;2, 2000.

Rögl, F.: Palaeogeographic considerations for Mediterranean and Paratethys Seaways (Oligocene to Miocene), Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien, 99A, 279–310, https://www.zobodat.at/pdf/ANNA_99A_0279-0310.pdf (last access: 31 November 2023), 1998.

Rosso, A., Sanfilippo, R., Guido, A., Gerovasileiou, V., Taddei Ruggiero, E., and Belmonte, G.: Colonisers of the dark: biostalactite-associated metazoans from “lu Lampiùne” submarine cave (Apulia, Mediterranean Sea), Mar. Ecol., 42, e12634, https://doi.org/10.1111/maec.12634, 2021.

Rosta, E.: Gilbert-type delta in the Sarmatian-Pannonian sediments, Sopron, NW-Hungary, Földt. Közl., 123/2, 167–193, https://epa.oszk.hu/01600/01635/00272/pdf/EPA01635_foldtani_kozlony_1993_123_2_167-193.pdf (last access: 31 November 2023), 1993.

Saint Martin, J.-P. and Pestrea, S.: Les constructions à serpules et microbialites du Sarmatien de Moldavie, Acta Palaeontologica Romaniae, 2, 463–469, 1999.

Saint Martin, J.-P. and Saint Martin, S.: Calcareous microbialites and associated biota in the Mediterranean coastal lagoons and ponds of southern France: a key for ancient bioconstructions?, Geo-Eco-Marina, 21, 55–71, 2015.

Shapiro, R. S.: A comment on the systematic confusion of thrombolites, Palaios, 15/2, 166–169, https://doi.org/10.1669/0883-1351(2000)015<0166:ACOTSC>2.0.CO;2, 2000.

Schmid, H. P., Harzhauser, M., and Kroh, A.: Hypoxic Events on a Middle Miocene Carbonate Platform of the Central Paratethys (Austria, Badenian, 14 Ma), with contributions by: Ćorić, S., Rögl, F., Schultz, O., Ann. Nat. Hist. Mus. Wien, 102A, 1–50, http://verlag.nhm-wien.ac.at/pdfs/102A_001050_Schmid.pdf (last access: 31 November 2023), 2001.

Siqueiros-Beltrones, D. A.: Role of Pro-Thrombolites in the geomorphology of a coastal Lagoon, Pac. Sci., 62/2, 257–269, https://doi.org/10.2984/1534-6188(2008)62[257:ROPITG]2.0.CO;2, 2008.

Śliwiński, M., Bąbel, M., Nejbert, K., Olszewska-Nejbert, D., Gąsiewicz, A, Schreiber, B. C., Benowitz, J. A., and Layer, P.: Badenian-Sarmatian chronostratigraphy in the Polish Carpathian Foredeep, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 326–328, 12–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.12.018, 2012.

Studencka, B. and Jasionowski, M.: Bivalves from the Middle Miocene reefs of Poland und Ukraine: A new approach to Badenian/Sarmatian boundary in the Paratethys, Acta Geol. Pol., 61/1, 79–114, 2011.

Suosaari, E., Reid, R., Playford, P., Foster, J. S., Stolz, J. F., Casaburi, G., Hagan, P. D., Chirayath, V., Macintyre, I. G., Planavsky, N.-J., and Eberli, G. P.: New multi-scale perspectives on the stromatolites of Shark Bay, Western Australia, Sci. Rep.-UK, 6, 20557, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20557, 2016.

Taylor, P. D., Hara, U., and Jasionowski, M.: Unusual early development in a cyclostome bryozoan from the Ukrainian Miocene, Linzer biologische Beiträge, 38/1, 55–64, 2006.

ten Hove, H. A. and van den Hurk, P.: A review of Recent and fossil serpulid “reefs”, actuopalaeontology and the “Upper Malm” serpulid limestones in NW Germany, Geol. Mijnbouw, 72, 23–67, 1993.

Vescogni, A., Guido, A., Cipriani, A., Gennari, R., Lugli, F., Lugli, S., Manzi, V., Reghizzi, M., and Roveri, M.: Palaeoenvironmental setting and depositional model of upper Messinian microbialites of the Salento Peninsula (Southern Italy): A central Mediterranean Terminal Carbonate Complex, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 595, 110970, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2022.110970, 2022.