the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Rates of palaeoecological change can inform ecosystem restoration

Walter Finsinger

Christian Bigler

Christoph Schwörer

Willy Tinner

Accelerations of ecosystem transformation raise concerns, to the extent that high rates of ecological change may be regarded amongst the most important ongoing imbalances in the Earth system. Here, we used high-resolution pollen and diatom assemblages and associated ecological indicators (the sum of tree and shrub pollen and diatom-inferred total phosphorus concentrations as proxies for tree cover and lake-water eutrophication, respectively) spanning the past 150 years to emphasize that rate-of-change records based on compositional data may document transformations having substantially different causes and outcomes. To characterize rates of change also in terms of other key ecosystem features, we quantified for both ecological indicators: (i) the percentage of change per unit time, (ii) the percentage of change relative to a reference level, and (iii) the rate of percentage change per unit time relative to a reference period, taking into account the irregular spacing of palaeoecological data. These measures document how quickly specific facets of nature changed, their trajectory, as well as their status in terms of palaeoecological indicators. Ultimately, some past accelerations of community transformation may document the potential of ecosystems to rapidly recover important ecological attributes and functions. In this context, insights from palaeoecological records may be useful to accelerate ecosystem restoration.

- Article

(1656 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Changes in community composition have long captured the attention of palaeoecologists as they often unfold transformations reflecting biotic responses to drivers of ecosystem change (e.g. climatic changes, human impact, competition, and changing disturbance regimes) (Birks, 2019). Amongst the different ways to explore and quantify past community transformations, rates of ecological change appear as particularly useful to estimate both how quickly and how much communities changed in the past, thereby allowing one to detect accelerations and slowdowns of ecological transformation (Steffen et al., 2015). Though the idea of irregular rates of change in nature was already mentioned in the Principles of Geology (Lyell, 1854), rates of palaeoecological change were formally introduced to Quaternary palaeoecology only more than a century later (Jacobson and Grimm, 1986) when chronologies of sedimentary records were better constrained.

Late Quaternary records of rates of palaeoecological change based on pollen sequences, and thus by inference vegetation compositional turnover, often show two main periods of acceleration (Jacobson and Grimm, 1986; Lotter et al., 1992; Bennett and Humphry, 1995; Seddon et al., 2015; Finsinger et al., 2017; Nogué et al., 2021): one period centred on the last deglaciation (ca. 14600–10000 cal BP) when rapid and high-amplitude climate-driven vegetation changes occurred and another acceleration during recent millennia under smaller-amplitude climate changes and increased human pressure. These patterns were recently confirmed using records around the globe (Mottl et al., 2021a) and applying new and improved approaches to estimate rates of palaeoecological change (Mottl et al., 2021b). Importantly, that study clearly documents unprecedented rates of ecological change in recent millennia that exceeded rates of climate-driven vegetation change during the last deglaciation, thereby demonstrating that humans undoubtedly can be viewed as a potent force capable of driving large and rapid ecological transformations (Overpeck and Breshears, 2021) already before the onset of industrialization.

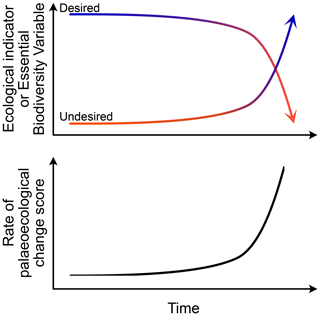

However, despite the concerns for the ongoing climate-driven and human-driven acceleration of ecological transformation (Steffen et al., 2015; Jouffray et al., 2020; Purvis et al., 2019), rates of change based on community composition (Jacobson and Grimm, 1986) unfold only one facet of ecosystem change (Purvis et al., 2019). Thus, rising rates of change based on assemblage records may document community transformations having substantially different underlying causes and, most importantly, different outcomes (Fig. 1). Yet, for a sound assessment of trends in nature, for instance from the perspective of ecological restoration (Clewell and Aronson, 2013), it may also be important to explore how other ecological properties changed (Purvis et al., 2019).

Figure 1Schematic model to illustrate the relationship between palaeoecological indicators characterizing the ecosystem state and its trajectory, as well as the resulting rate of palaeoecological change based on compositional data. The rate of palaeoecological change may rise irrespective of how and in which direction ecosystems changed, as it estimates the absolute amount of compositional change.

Given these theoretical and empirical premises, the aim of the present contribution is to emphasize the importance of characterizing rates of palaeoecological change also in terms of other ecological properties rather than solely on community composition. To do this, we build on recent work of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES, 2019) that used essential biodiversity variables (EBVs; Pereira et al., 2013) and ecological indicators as a basis for the assessment of both the trends in nature and the current status of nature (Purvis et al., 2019). The examples chosen concern post-industrial transformations of both terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems, as documented by pollen and diatom records from a lake located in the forelands of the western Italian Alps (Finsinger et al., 2006). We chose these palaeoecological records because they have a high temporal resolution (Fig. A1) and a well-established chronology based on annual varve counts supported by short-lived radionuclide measurements and by biostratigraphic control points. Accordingly, these datasets disclose rapid environmental changes in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, revealing compositional changes that occurred in conjunction with both undesired and desired changes of ecological properties during the past 150 years.

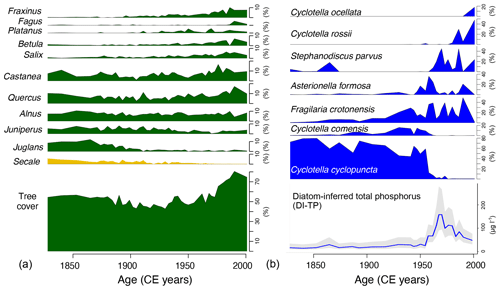

Specifically, the pollen assemblages document an increase of tree cover starting around 1960 CE (Fig. 2a), as also observed in other high-resolution pollen records from the European Alps that provide evidence for the spread of natural woodlands mainly as a result of the abandonment of agriculture in marginal areas (Tinner et al., 1998; van der Knaap et al., 2000; Brugger et al., 2021) and reforestation programmes and afforestation actions (Fuchs et al., 2013; Brugger et al., 2021). At Lago Grande di Avigliana this is supported by the decrease of cultivated species such as Juglans and Secale and the enlargement of the wooded area by the spread of different taxa, such as pioneer taxa colonizing abandoned fields and meadows (Betula), trees growing on wetter sites such as the lake shores (Salix), arboreal plants of the mixed oak forest (Fraxinus, Quercus), ornamental trees (Platanus), as well as late-successional shade-tolerant trees (Fagus) (Tinner et al., 1998).

In the freshwater lake ecosystem, diatom assemblages substantially changed around 1950–1960 CE, and diatom-inferred total phosphorus concentration (DI-TP) rapidly rose. DI-TP culminated in the late 1960s (Fig. 2b) as a result of the sewage discharge from the bursting and unmanaged urban drain network. Subsequently, DI-TP values decreased, indicating a rapid recovery of the freshwater ecosystem due to conservation measures, such as the drain-network deflection of sewage discharge that likely reduced phosphorus loads (Finsinger et al., 2006). The DI-TP record illustrates the eutrophication history common to several low-elevation lakes in the European Alps over the 19th–20th centuries (Lotter, 1998; Marchetto et al., 2004; Bigler et al., 2007).

Figure 2Synthetic illustration of community composition changes for the terrestrial vegetation (a) and the aquatic diatom flora (b) as documented by pollen and diatom percentages from sediments of Lago Grande di Avigliana (Italy) for the past ca. 150 years, as well as pollen-inferred tree cover (%) and diatom-inferred total phosphorous (TP, µg L−1) concentration (from Finsinger et al., 2006).

The pollen data from Lago Grande di Avigliana with associated metadata and chronology (Finsinger et al., 2019) were obtained from the Neotoma database (Williams et al., 2018) and its constituent database (European Pollen Database (EPD); Giesecke et al., 2014) using the NeotomaExplorer app. To account for the irregular spacing of palaeoecological records, rates of palaeoecological change (hereafter RoC) scores were calculated with the R-Ratepoll v1.2.1 package (Mottl et al., 2021b). In addition, we devised two custom-coded functions in the R environment (R Core Team, 2022) to unfold both how quickly and in which direction palaeoecological indicators changed. To explore the trends of palaeoecological indicators, we used the relative abundance of tree and shrub pollen as a proxy for tree cover (Lang et al., 2023) and the diatom-inferred total phosphorous (DI-TP) concentrations (Finsinger et al., 2006) that illustrates the effects of cultural eutrophication and freshwater restoration (Lotter et al., 1997; Smol, 2008). Specifically, we quantified (i) the rate of change of the indicators as a percentage of change per unit time to show the rapidity and direction of change, (ii) the percentage of change relative to the inferred or estimated reference level to show how much was present after (and if applicable also before) the reference period, and (iii) the rate of percentage change per unit time relative to the inferred or estimated reference level (Purvis et al., 2019). As reference periods for the pollen-inferred tree cover, we selected the time intervals 1970–1979 CE (Purvis et al., 2023) and 1940–1950 CE (Fuchs et al., 2013) to compare the results with documentary data. Likewise, we use temporally based reference conditions using palaeo-reconstructions for the freshwater ecosystem, as acknowledged in the European Water Framework Directive (WFD 2000/60/EC; Bennion et al., 2011; Smol, 2008). Specifically, for the DI-TP record we selected the time interval 1800–1899 CE, which pre-dates the earliest major step in lake-water eutrophication during the 19th–20th centuries in lowland lakes in the region of the European Alps (Bigler et al., 2007; Finsinger et al., 2006; Lotter, 1998; Marchetto et al., 2004). See Appendix A for further details.

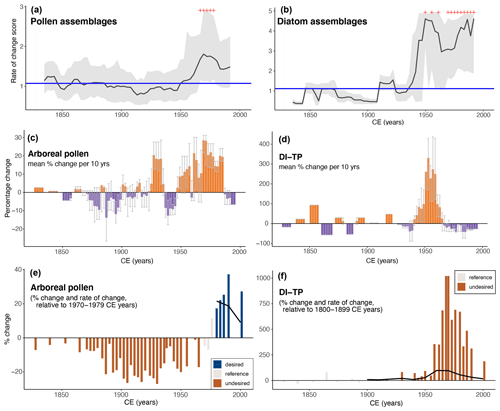

3.1 Rates of palaeoecological change

The pollen and diatom assemblages changed substantially during the second half of the 20th century, and significant RoC peaks were detected in both records between 1950 and 2000 CE (Fig. 3a–b). RoC scores increased faster for diatom assemblages and the magnitude of change was about 2 times larger for the diatom than for the pollen assemblages. The shorter generation times of diatoms and the fact that the lake is a closed ecosystem may be important, though not exclusive, factors contributing to the different velocity and magnitude of change (Ammann et al., 2000). The RoC records also differ in their trajectory after 1950 CE, as RoC scores of diatom assemblages were persistently high until 2000 CE, whereas RoC scores of pollen assemblages decreased in the most recent decades.

3.2 Trends of palaeoecological indicators

The per-decade mean percentage change of tree cover (Fig. 3c) shows transient variations (± 20 % per decade) until 1950 CE followed by a 30-year-long period of persistently positive changes (up to 30 % per decade) between 1950 and 1990 CE. DI-TP varied even less before 1950 CE (Fig. 3d) when compared to its highest mean percentage change (up to 300 % per decade) around 1960 CE. However, the per-decade mean percentage change of DI-TP persistently decreased after 1960 CE (up to −50 % per decade).

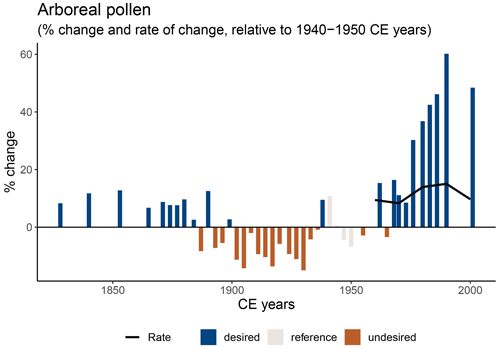

Compared to the average inferred reference values, the tree cover was up to 40 % higher around 1990–2000 CE than during 1970–1979 CE (Fig. 3e) and up to 60 % higher than during 1940–1950 CE (Fig. A2). The average per-decade rate of change in tree cover was 9 %–10 % between 1970–1979 and 2000 CE as well as between 1940–1950 and 2000 CE (Fig. 3e–f). DI-TP values were up to 1000 % higher than during the reference period 1800–1899 CE, and the per-decade rate of change of DI-TP was 17 % between 1800–1899 and 2000 CE (Fig. 3f).

Figure 3Comparison between rates of palaeoecological change based on (a) the pollen and (b) the diatom assemblages from sediments of Lago Grande di Avigliana. (c–f) The trends of palaeoecological indicators for the terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems (arboreal pollen percentages indicative of tree cover and diatom-inferred total phosphorous concentration (DI-TP), respectively) for the past ca. 150 years. The panels in the middle (c–d) document how quickly and in which direction the indicators changed as the average decadal rate of percentage change (coloured bars: mean values; whiskers: first and third quartiles). The bottom panels (e–f) show how much of the indicator was present after (and if applicable also before) the reference period (filled bars), as well as how quickly and in which direction the indicators shifted relative to the reference period on the basis of the per-decade rate of percentage change relative to the reference period (black continuous line).

Assessments of past rates of ecological change are important to explore how quickly ecosystems changed through time and highlight accelerations of ecosystem transformation (Overpeck and Breshears, 2021). Currently, high expected rates of ecological change in response to predicted high rates of climate change raise concerns, as species' and ecosystems' capacity to respond adaptively may be outpaced (Williams et al., 2021). Moreover, human actions appear as significant drivers for rising rates of change of vegetation composition (Mottl et al., 2021a), to the extent that high rates of ecological changes may be regarded amongst the most important ongoing imbalances in the Earth system (Albert et al., 2023).

We found that RoC scores of pollen assemblages significantly peaked at the time of the spread of natural woodlands as a result of land-use changes including abandonment of agricultural lands in marginal areas (Figs. 2 and 3a), indicating that high RoC scores can also document shifts towards less degraded conditions. Likewise, diatom assemblages significantly changed both when lake-water eutrophication increased as well as when the freshwater system recovered towards more desired total phosphorus concentrations (Figs. 2 and 3b). Thus, rises and significant peaks of RoC records may occur irrespective of the underlying trajectory of ecosystems (Fig. 1), thereby supporting the view that RoC records based on compositional data should be interpreted in the context of the nature of changes.

By contrast, the assessment of the rate of change of ecological indicators allows assessing how quickly and in which direction ecosystem properties changed through time. For instance, the per-decade percentage change of the arboreal pollen documents a net gain in tree cover when vegetation composition significantly changed (Fig. 3c). Likewise, the DI-TP percentage change record documents the changing trajectory of lake eutrophication during the time interval of significant diatom-assemblage changes (Fig. 3d). Thus, these measures of ecosystem trajectories based on palaeoecological indicators document how the 19th–20th centuries and ongoing land-use changes in the lowlands of the European Alps reversed longer-term trends of ecosystem degradation (Birks and Tinner, 2016), both accidentally (e.g. land abandonment) and intentionally (lake restoration, forest protection and/or restoration).

Such assessments are consistent with the way the IPBES (2019) assesses trends in nature on the basis of ecological indicators and essential biodiversity variables (Pereira et al., 2013; Purvis et al., 2019), some of which can be estimated based on palaeoecological records and could complement RoC records. Admittedly, only one facet of nature was explored here for the terrestrial and the freshwater environments, respectively. Given that nature is too complex for its trends and status to be captured by one or a few indicators (Purvis et al., 2019), palaeoecological data may be explored to yield other indicators, such as the abundance of invasive and exotic species, biodiversity measures, browsing and grazing intensity, fire activity, or environmental disturbance such as drought or frost (Tinner, 2023), to name a few. It may further be speculated that the ambiguity of RoC records is not limited to records for the 20th–21st centuries when restoration actions often reversed longer-term trends of ecosystem degradation. Previous plant community changes were sometimes embedded in a longer-term framework of varying human footprints. For instance, pollen records from Europe often document for the Late Holocene alternating land-abandonment phases and more intensive land-use phases (Schibler et al., 1997; Tinner et al., 2003; Finsinger and Tinner, 2006; Rey et al., 2019), usually involving more or less marked rises and falls of tree cover. Moreover, it should be noted that ecosystem properties are also context dependent. Whilst increases in tree cover might be viewed favourably in the context of the ecological restoration for this ecosystem, in other locations (e.g. grasslands) increases in tree cover might not necessarily be representative of a positive change in terms of restoration (Veldman et al., 2019).

Assessing the long-term development of palaeoecological indicators may also be useful to explore key features of ecosystems relative to ecological references or baselines. Baselines are an integral part of the conceptual framework of the UN's decade on ecosystem restoration (2021–2030) and are an asset of palaeoecological records (Willis et al., 2010; Nogué et al., 2022; Burge et al., 2023) as the current status of nature is often assessed with reference to relatively recent periods (e.g. mostly after 1970 CE; Purvis et al., 2019). Here, we found that tree cover rose at an average per-decade rate of > 9 % between 1970–1979 and 2000 CE (Fig. 3e), suggesting it rose faster than the global average (2.1 %; Purvis et al., 2019). Interestingly, it also rose at an average per-decade rate of ca. 9 % between 1940–1950 and 2000 CE (Fig. A2), supporting the notion of a net gain in tree cover (here 50 %–60 %) documented on the basis of land-cover datasets (25 %) for Europe (Fuchs et al., 2013) for a longer time interval than the one considered by Purvis et al. (2019) (ca. 50 vs. 30 years). While the higher net gain documented by the pollen record does not take into account potential representation issues, which could be addressed by correction for the differences in pollen productivity and dispersal (Sugita, 1994; Seppä, 2013), it suggests the occurrence of a high spatial variability that could be further explored with a network of pollen records. Moreover, it is noteworthy to mention that several diatom taxa which dominated the lakes' flora prior to the cultural eutrophication did not reappear during the recovery (Fig. 2), a feature often observed in palaeolimnological diatom records (Smol, 2008). In contrast to methods based on community composition (e.g. Burge et al., 2023) that would very likely highlight the dissimilarity between the assemblages, information provided by the change of palaeoecological indicators gives “permission to accept transient environmental and ecological change” (Jackson and Hobbs, 2009).

The analysis of rates of compositional change together with those of palaeoecological indicators that document key features of nature (e.g. tree cover, freshwater eutrophication, diversity measures, and disturbance dynamics) thus may provide insights into the speed of ecosystem recovery as well as into conditions under which ecosystem recovery may and may not occur, thereby informing managers about the level of intervention needed in ecosystem restoration based on long-term data (Willis et al., 2010; Whitlock et al., 2018). Ultimately, past accelerations of community transformation may document the potential of ecosystems to shift toward more desired states and recover important ecological attributes such as their functions and diversity. Such insights may be useful to accelerate ecosystem restoration (Manzano et al., 2020; Edrisi and Abhilash, 2021; Gillson, 2022).

A1 Data pre-treatment and analysis

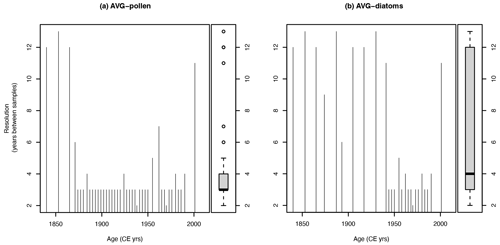

The pollen and diatom data were treated and thereafter their format adapted for the R-Ratepoll package (Mottl et al., 2021b) with custom-coded functions in the R environment (R Core Team, 2022). The treatments for the pollen data include filtering the data to select only terrestrial pollen types (thus, excluding pollen and spores from obligate aquatic plants), removing the Humulus/Cannabis-type and a sample having a low pollen count sum (< 195), and harmonizing the taxonomy following Mottl et al. (2021a). The diatom data were filtered to include only diatom taxa (thus, excluding chrysophyte cysts). Initial exploratory data analysis also focussed on the assessment of the inter-sample distances (in years) of the samples (Fig. A1). Inter-sample distances are overall < 14 years and < 5 years for the time interval 1940–2000 CE.

A2 Rates of palaeoecological change

Rates of palaeoecological change (hereafter RoC) scores were calculated with the R-Ratepoll package (Mottl et al., 2021b) using the pollen and diatom counts with the following settings: age-weighted average smoothing, binning with 14-year-long moving windows (thus, with larger working units than the largest inter-sample distance), shifting moving windows three times, random selection of samples from bins, random sampling without replacement to draw 195 individuals from each working unit, the chi-squared coefficient as the dissimilarity coefficient, transforming the counts to proportions, and rescaling RoC score values to the RoC per 50 years. These calculations were reiterated 999 times, and thereafter significant RoC peaks were identified by comparing the 95th quantile of the RoC scores from all calculations and the median of all RoC scores from the whole sequence.

A3 Trends of palaeoecological indicators

Firstly, we quantified the rate of change of palaeoecological indicators as a percentage of change per unit time, thereby showing how quickly the indicator changed and its trend (Purvis et al., 2019). Following Mottl et al. (2021b), we took into account the irregular spacing of palaeoecological records by binning with moving windows, random selection of samples from bins, and shifting moving windows (here five times). The random selection procedure was repeated 99 times for each set of moving windows prior to calculating summary statistic values (i.e. the mean, the median, and the first and third quartiles). As we focussed on the higher sampling-resolution time interval, we used 10-year-long moving windows. Secondly, we quantified the change in the indicator as a percentage of change relative to the inferred or estimated reference level, thereby showing how much was present after the reference period (Purvis et al., 2019) and, if applicable, also how much was present before the reference period. Thirdly, we quantified the per-decade rate of percentage change relative to the inferred or estimated reference level. To do this, we first calculated the change between the mean reference value and the post-reference values and thereafter divided them by the number of “bins” between their dates to provide a per-unit-time rate of change. For instance, with bins equal to 10 years, we quantified the per-decade rate of change. It should be noted that this is just the average rate of net change over the time span being considered, whether or not the change was linear (Purvis et al., 2019).

Figure A1Inter-sample distance for the pollen (a) and the diatom records (b) from the sediments of Lago Grande di Avigliana (Finsinger et al., 2006).

The pollen data (Finsinger et al., 2019) were obtained from the Neotoma database (Williams et al., 2018) and its constituent database (European Pollen Database, EPD; Giesecke et al., 2014). The diatom record and all computer codes are publicly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10075146 (Finsinger, 2024).

WF conceived of the paper and was responsible for developing the code, generating all figures, and writing the original draft. The manuscript was reviewed and edited with contributions from all co-authors.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

Data were obtained from the Neotoma Paleoecology Database (http://www.neotomadb.org, last access: 2 November 2023) and its constituent database (European Pollen Database, EPD). The work of data contributors, data stewards, and the Neotoma community is gratefully acknowledged.

This paper was edited by Paul Stoy and reviewed by Alistair W. R. Seddon and one anonymous referee.

Albert, J. S., Carnaval, A. C., Flantua, S. G. A., Lohmann, L. G., Ribas, C. C., Riff, D., Carrillo, J. D., Fan, Y., Figueiredo, J. J. P., Guayasamin, J. M., Hoorn, C., De Melo, G. H., Nascimento, N., Quesada, C. A., Ulloa Ulloa, C., Val, P., Arieira, J., Encalada, A. C., and Nobre, C. A.: Human impacts outpace natural processes in the Amazon, Science, 379, eabo5003, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abo5003, 2023.

Ammann, B., Birks, H. J. B., Brooks, S. J., Eicher, U., von Grafenstein, U., Hofmann, W., Lemdahl, G., Schwander, J., Tobolski, K., and Wick, L.: Quantification of biotic responses to rapid climatic changes around the Younger Dryas – a synthesis, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 159, 313–347, 2000.

Bennett, K. D. and Humphry, R. W.: Analysis of late-glacial and Holocene rates of vegetational change at two sites in the British Isles, Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol., 85, 263–287, 1995.

Bennion, H., Battarbee, R. W., Sayer, C. D., Simpson, G. L., and Davidson, T. A.: Defining reference conditions and restoration targets for lake ecosystems using palaeolimnology: a synthesis, J. Paleolimnol., 45, 533–544, 2011.

Bigler, C., Von Gunten, L., Lotter, A. F., Hausmann, S., Blass, A., Ohlendorf, C., and Sturm, M.: Quantifying human-induced eutrophication in Swiss mountain lakes since AD 1800 using diatoms, Holocene, 17, 1141–1154, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683607082555, 2007.

Birks, H. J. B.: Contributions of Quaternary botany to modern ecology and biogeography, Plant Ecol. Divers., 12, 189–385, https://doi.org/10.1080/17550874.2019.1646831, 2019.

Birks, H. J. B. and Tinner, W.: Past forests of Europe, in: European Atlas of Forest Tree Species, edited by: San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., and Mauri, A., Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, e010c45+, https://doi.org/10.2760/776635, 2016.

Brugger, S. O., Schwikowski, M., Gobet, E., Schwörer, C., Rohr, C., Sigl, M., Henne, S., Pfister, C., Jenk, T. M., Henne, P. D., and Tinner, W.: Alpine Glacier Reveals Ecosystem Impacts of Europe's Prosperity and Peril Over the Last Millennium, Geophys. Res. Lett., 48, e2021GL095039, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL095039, 2021.

Burge, O. R., Richardson, S. J., Wood, J. R., and Wilmshurst, J. M.: A guide to assess distance from ecological baselines and change over time in palaeoecological records, Holocene, 33, 09596836231169986, https://doi.org/10.1177/09596836231169986, 2023.

Clewell, A. F. and Aronson, J.: Ecological restoration: principles, values, and structure of an emerging profession, 2nd ed., Island Press, Washington DC, 303 pp., https://doi.org/10.5822/978-1-59726-323-8, 2013.

Edrisi, S. A. and Abhilash, P. C.: Need of transdisciplinary research for accelerating land restoration during the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, Restor. Ecol., 29, e13531, https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.13531, 2021.

Finsinger, W.: paleo_perc_change (v1.0.1), Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10630763, 2024.

Finsinger, W. and Tinner, W.: Holocene vegetation and land-use changes in the forelands of the southwestern Alps, Italy, J. Quat. Sci., 21, 243–258, 2006.

Finsinger, W., Bigler, C., Krähenbühl, U., Lotter, A. F., and Ammann, B.: Human impact and eutrophication patterns during the past ∼ 200 yrs at Lago Grande di Avigliana (N. Italy), J. Paleolimnol., 36, 55–67, 2006.

Finsinger, W., Giesecke, T., Brewer, S., and Leydet, M.: Emergence patterns of novelty in European vegetation assemblages over the past 15 000 years, Ecol. Lett., 20, 336–346, https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12731, 2017.

Finsinger, W., Bigler, C., Krähenbühl, U., Lotter, A. F., and Ammann, B.: Lago Grande di Avigliana pollen dataset, Neotoma Paleoecological Database [data set], https://doi.org/10.21233/CD0E-0190, 2019.

Fuchs, R., Herold, M., Verburg, P. H., and Clevers, J. G. P. W.: A high-resolution and harmonized model approach for reconstructing and analysing historic land changes in Europe, Biogeosciences, 10, 1543–1559, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-1543-2013, 2013.

Giesecke, T., Davis, B., Brewer, S., Finsinger, W., Wolters, S., Blaauw, M., De Beaulieu, J.-L., Binney, H., Fyfe, R. M., Gaillard, M.-J., Gil-Romera, G., Knaap, W. O., Kuneš, P., Kühl, N., Leeuwen, J. F. N., Leydet, M., Lotter, A. F., Ortu, E., Semmler, M., and Bradshaw, R. H. W.: Towards mapping the late Quaternary vegetation change of Europe, Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany, 23, 75–86, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-012-0390-y, 2014.

Gillson, L.: Paleoecology reveals lost ecological connections and strengthens ecosystem restoration, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 119, e2206436119, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2206436119, 2022.

IPBES: Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, edited by: Díaz, S., Settele, J., Brondízio, E. S., Ngo, H. T., Guèze, M., Agard, J., Arneth, A., Balvanera, P., Brauman, K. A., Butchart, S. H. M., Chan, K. M. A., Garibaldi, L. A., Ichii, K., Liu, J., Subramanian, S. M., Midgley, G. F., Miloslavich, P., Molnár, Z., Obura, D., Pfaff, A., Polasky, S., Purvis, A., Razzaque, J., Reyers, B., Roy Chowdhury, R., Shin, Y. J., Visseren-Hamakers, I. J., Willis, K. J., and Zayas, C. N., IPBES Secretariat, Bonn, Germany, ISBN 978-3-947851-13-3, 2019.

Jackson, S. T. and Hobbs, R. J.: Ecological restoration in the light of ecological history, Science, 325, 567–569, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1172977, 2009.

Jacobson, G. L. and Grimm, E. C.: A Numerical Analysis of Holocene Forest and Prairie Vegetation in Central Minnesota, Ecology, 67, 958–966, https://doi.org/10.2307/1939818, 1986.

Jouffray, J.-B., Blasiak, R., Norström, A. V., Österblom, H., and Nyström, M.: The Blue Acceleration: The Trajectory of Human Expansion into the Ocean, One Earth, 2, 43–54, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2019.12.016, 2020.

Lang, G., Ammann, B., Behre, K.-E., and Tinner, W. (Eds.): Quaternary Vegetation Dynamics of Europe, Haupt Verlag, ISBN 978-3-258-08214-1, 2023.

Lotter, A. F.: The recent eutrophication of Baldeggersee (Switzerland) as assessed by fossil diatom assemblages, Holocene, 8, 395–405, https://doi.org/10.1191/095968398674589725, 1998.

Lotter, A. F., Ammann, B., and Sturm, M.: Rates of change and chronological problems during the late-glacial period, Clim. Dyn., 6, 233–239, 1992.

Lotter, A. F., Birks, H. J. B., Hofmann, W., and Marchetto, A.: Modern diatom, cladocera, chironomid and chrysophyte cyst assemblages as quantitative indicators for the reconstructions of past environmental conditions in the Alps, I. Climate, J. Paleolimnol., 18, 395–420, 1997.

Lyell, C.: Principles of Geology or, the modern changes of the earth and its inhabitants considered as illustrative of Geology, D. Appleton & Co., New York, 1854.

Manzano, S., Julier, A. C. M., Dirk, C. J., Razafimanantsoa, A. H. I., Samuels, I., Petersen, H., Gell, P., Hoffman, M. T., and Gillson, L.: Using the past to manage the future: the role of palaeoecological and long-term data in ecological restoration, Restor. Ecol., 28, 1335–1342, https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.13285, 2020.

Marchetto, A., Lami, A., Musazzi, S., Massaferro, J., Langone, L., and Guilizzoni, P.: Lake Maggiore (N. Italy) trophic history: fossil diatom, plant pigments, and chironomids, and comparison with long-term limnological data, Quaternary Int., 113, 97–110, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-6182(03)00082-X, 2004.

Mottl, O., Flantua, S. G. A., Bhatta, K. P., Felde, V. A., Giesecke, T., Goring, S., Grimm, E. C., Haberle, S., Hooghiemstra, H., Ivory, S., Kuneš, P., Wolters, S., Seddon, A. W. R., and Williams, J. W.: Global acceleration in rates of vegetation change over the past 18,000 years, Science, 372, 860–864, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abg1685, 2021a.

Mottl, O., Grytnes, J.-A., Seddon, A. W. R., Steinbauer, M. J., Bhatta, K. P., Felde, V. A., Flantua, S. G. A., and Birks, H. J. B.: Rate-of-change analysis in paleoecology revisited: A new approach, Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol., 293, 104483, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revpalbo.2021.104483, 2021b.

Nogué, S., Santos, A. M. C., Birks, H. J. B., Björck, S., Castilla-Beltrán, A., Connor, S., De Boer, E. J., De Nascimento, L., Felde, V. A., Fernández-Palacios, J. M., Froyd, C. A., Haberle, S. G., Hooghiemstra, H., Ljung, K., Norder, S. J., Peñuelas, J., Prebble, M., Stevenson, J., Whittaker, R. J., Willis, K. J., Wilmshurst, J. M., and Steinbauer, M. J.: The human dimension of biodiversity changes on islands, Science, 372, 488–491, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd6706, 2021.

Nogué, S., De Nascimento, L., Gosling, W. D., Loughlin, N. J. D., Montoya, E., and Wilmshurst, J. M.: Multiple baselines for restoration ecology, Past Glob. Change Mag., 30, 4–5, https://doi.org/10.22498/pages.30.1.4, 2022.

Overpeck, J. T. and Breshears, D. D.: The growing challenge of vegetation change, Science, 372, 786–787, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abi9902, 2021.

Pereira, H. M., Ferrier, S., Walters, M., Geller, G. N., Jongman, R. H. G., Scholes, R. J., Bruford, M. W., Brummitt, N., Butchart, S. H. M., Cardoso, A. C., Coops, N. C., Dulloo, E., Faith, D. P., Freyhof, J., Gregory, R. D., Heip, C., Höft, R., Hurtt, G., Jetz, W., Karp, D. S., McGeoch, M. A., Obura, D., Onoda, Y., Pettorelli, N., Reyers, B., Sayre, R., Scharlemann, J. P. W., Stuart, S. N., Turak, E., Walpole, M., and Wegmann, M.: Essential Biodiversity Variables, Science, 339, 277–278, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1229931, 2013.

Purvis, A., Molnár, Z., Obura, D., Ichii, K., Willis, K., Chettri, N., Dulloo, M., Hendry, A., Gabrielyan, B., Gutt, J., Jacob, U., Keskin, E., Niamir, A., Öztürk, B., Salimov, R., and Jaureguiberry, P.: Status and Trends – Nature, Chap. 2.2, in: Global assessment report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, edited by: Brondizio, E. S., Settele, J., Díaz, S., and Ngo, H. T., IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany, 108, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3831674, 2019.

R Core Team: R: A language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.R-project.org/ (last access: 2 April 2024), 2022.

Rey, F., Gobet, E., Schwörer, C., Wey, O., Hafner, A., and Tinner, W.: Causes and mechanisms of synchronous succession trajectories in primeval Central European mixed Fagus sylvatica forests, J. Ecol., 107, 1392–1408, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.13121, 2019.

Schibler, J., Jacomet, S., Hüster-Plogmann, H., and Brombacher, C.: Economic crash in the 37th and 36th centuries cal. BC in Neolithic lake shore sites in Switzerland, Anthropozoologica, 25–26, 553–570, 1997.

Seddon, A. W., Macias-Fauria, M., and Willis, K. J.: Climate and abrupt vegetation change in Northern Europe since the last deglaciation, The Holocene, 25, 25–36, 2015.

Seppä, H.: Pollen Analysis, Principles, in: Encyclopedia of Quaternary Science, Elsevier, 794–804, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53643-3.00171-0, 2013.

Smol, J. P.: Pollution of lakes and rivers: a paleoenvironmental perspective, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1-405-15913-5, 2008.

Steffen, W., Broadgate, W., Deutsch, L., Gaffney, O., and Ludwig, C.: The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration, Anthr. Rev., 2, 81–98, https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019614564785, 2015.

Sugita, S.: Pollen representation of vegetation in Quaternary sediments – theory and method in patchy vegetation, J. Ecol., 82, 881–897, 1994.

Tinner, W.: Long-term disturbance ecology, in: Quaternary Vegetation Dynamics of Europe, edited by: Lang, G., Ammann, B., Behre, K.-E., and Tinner, W., Haupt Verlag, 467–485, ISBN 978-3-258-08214-1, 2023.

Tinner, W., Conedera, M., Ammann, B., Gaggeler, H. W., Gedye, S., Jones, R., and Sagesser, B.: Pollen and charcoal in lake sediments compared with historically documented forest fires in southern Switzerland since AD 1920, Holocene, 8, 31–42, 1998.

Tinner, W., Lotter, A. F., Ammann, B., Conedera, M., Hubschmid, P., van Leeuwen, J. F. N., and Wehrli, M.: Climatic change and contemporaneous land-use phases north and south of the Alps 2300 BC to 800 AD, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 22, 1447–1460, 2003.

van der Knaap, W. O., van Leeuwen, J. F. N., Fankhauser, A., and Ammann, B.: Palynostratigraphy of the last centuries in Switzerland based on 23 lake and mire deposits: chronostratigraphic pollen markers, regional patterns, and local histories, Rev. Paleaobot. Palynol., 108, 85–142, 2000.

Veldman, J. W., Aleman, J. C., Alvarado, S. T., Anderson, T. M., Archibald, S., Bond, W. J., Boutton, T. W., Buchmann, N., Buisson, E., Canadell, J. G., Dechoum, M. D. S., Diaz-Toribio, M. H., Durigan, G., Ewel, J. J., Fernandes, G. W., Fidelis, A., Fleischman, F., Good, S. P., Griffith, D. M., Hermann, J.-M., Hoffmann, W. A., Le Stradic, S., Lehmann, C. E. R., Mahy, G., Nerlekar, A. N., Nippert, J. B., Noss, R. F., Osborne, C. P., Overbeck, G. E., Parr, C. L., Pausas, J. G., Pennington, R. T., Perring, M. P., Putz, F. E., Ratnam, J., Sankaran, M., Schmidt, I. B., Schmitt, C. B., Silveira, F. A. O., Staver, A. C., Stevens, N., Still, C. J., Strömberg, C. A. E., Temperton, V. M., Varner, J. M., and Zaloumis, N. P.: Comment on “The global tree restoration potential”, Science, 366, eaay7976, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay7976, 2019.

Whitlock, C., Colombaroli, D., Conedera, M., and Tinner, W.: Land-use history as a guide for forest conservation and management, Conserv. Biol., 32, 84–97, https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12960, 2018.

Williams, J. W., Grimm, E. C., Blois, J. L., Charles, D. F., Davis, E. B., Goring, S. J., Graham, R. W., Smith, A. J., Anderson, M., Arroyo-Cabrales, J., Ashworth, A. C., Betancourt, J. L., Bills, B. W., Booth, R. K., Buckland, P. I., Curry, B. B., Giesecke, T., Jackson, S. T., Latorre, C., Nichols, J., Purdum, T., Roth, R. E., Stryker, M., and Takahara, H.: The Neotoma Paleoecology Database, a multiproxy, international, community-curated data resource, Quaternary Res., 89, 156–177, https://doi.org/10.1017/qua.2017.105, 2018.

Williams, J. W., Ordonez, A., and Svenning, J.-C.: A unifying framework for studying and managing climate-driven rates of ecological change, Nat. Ecol. Evol., 5, 17–26, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-01344-5, 2021.

Willis, K. J., Bailey, R. M., Bhagwat, S. A., and Birks, H. J. B.: Biodiversity baselines, thresholds and resilience: testing predictions and assumptions using palaeoecological data, Trends Ecol. Evol., 25, 583–591, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2010.07.006, 2010.