the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Animal burrowing at cold seep ecotones boosts productivity by linking macromolecule turnover with chemosynthesis and nutrient cycling

Maxim Rubin-Blum

Eyal Rahav

Guy Sisma-Ventura

Yana Yudkovski

Zoya Harbuzov

Or M. Bialik

Oded Ezra

Anneleen Foubert

Barak Herut

Yizhaq Makovsky

Hydrocarbon seepage at the deep seafloor fuels flourishing chemosynthetic communities. These seeps impact the functionality of the benthic ecosystem beyond hotspots of gas emission, altering the abundance, diversity, and activity of microbiota and fauna and affecting geochemical processes. However, these chemosynthetic ecotones (chemotones) are far less explored than the foci of seepage. To better understand the functionality of chemotones, we (i) mapped seabed morphology at the periphery of gas seeps in the deep eastern Mediterranean Sea, using video analyses and synthetic aperture sonar; (ii) sampled chemotone sediments and described burrowing using computerized tomography; (iii) explored nutrient concentrations; (iv) quantified microbial abundance, activity, and N2 fixation rates in selected samples; and (v) extracted DNA and explored microbial diversity and function using amplicon sequencing and metagenomics. Our results show that gas seepage creates burrowing intensity gradients at seep ecotones, with the ghost shrimp Calliax lobata primarily responsible for burrowing, which influences nitrogen and sulfur cycling through microbial activity. Burrow walls form a unique habitat, where macromolecules are degraded by Bacteroidota, and their fermentation products fuel sulfate reduction by Desulfobacterota and Nitrospirota. These, in turn, support chemosynthetic Campylobacterota and giant sulfur bacteria Thiomargarita, which can aid C. lobata nutrition. These interactions may support enhanced productivity at seep ecotones.

- Article

(7730 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2534 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Most organisms in the deep-sea biosphere thrive under extreme energy limitation (Orsi, 2018). In this dark, energy-limited environment, the natural discharge of fossil hydrocarbons results in accelerated biogeochemical dynamics, creating unique geobiological habitats – cold seeps (Joye, 2020). Cold seeps form the richest and most productive ecosystems that are widespread across continental margins (Joye, 2020; Levin and Sibuet, 2012). The transition zones between these highly productive ecosystems and the often impoverished deep-sea benthic habitats are considered chemosynthetic ecotones, i.e., chemotones (Ashford et al., 2021). The chemotone communities benefit from chemosynthetic production, which can deliver food supplements through the water column, and intrinsic chemosynthetic producers in the sediments, resulting in intermediate biomass and richness as well as a distinct species composition (Ashford et al., 2021). These areas of interactions and transition affect the deep-sea ecosystem services, most importantly, carbon cycling and sequestration, as well as fisheries production (Levin et al., 2016). However, our knowledge of chemotone communities is limited, and their functionality has not been studied in detail (e.g., Amon et al., 2017; Ashford et al., 2021; Åström et al., 2022; Ritt et al., 2011).

Chemical and temperature clines around seep edifices may determine the biogeochemical processes at chemotones (Levin et al., 2016). In turn, surface water productivity and fluxes of photosynthetic carbon to the seep area may also impact the extent of seep chemotones (Ashford et al., 2021). For example, strong pelagic–benthic coupling limits the chemosynthetic inputs in some Arctic seeps (Åström et al., 2022). Cold seeps are also pervasive in the warm (13.5 and 15.5 °C) deep waters of the ultraoligotrophic southeastern Mediterranean Sea (SEMS) (Bayon et al., 2009; Coleman and Ballard, 2001; Coleman et al., 2011; Herut et al., 2022; Kormas and Meziti, 2020; Lawal et al., 2023; Olu-Le Roy et al., 2004). In high contrast to the Arctic seeps, weak benthic–pelagic coupling in the ultraoligotrophic SEMS may lead to sharp gradients between the active seep sites and the energy-limited deep benthos (Sisma-Ventura et al., 2022). The warm deep-sea temperatures may alter the availability of dissolved gases and boost microbial activity in the SEMS, potentially affecting the biogeochemical gradients at seep clines (Mavropoulou et al., 2020; Rahav et al., 2019; Roether and Well, 2001).

Here, we focus on cold seep chemotones at the toe region of the Palmahim Disturbance, an evaporite-rooted, progressive, large-scale (∼ 15 km × 50 km), rotational submarine slide on the SEMS continental margin, offshore of Israel (Gadol et al., 2020; Garfunkel et al., 1979); (Fig. 1). These seeps are characterized by local hotspots of slow diffusive discharge, where authigenic carbonates are formed (Rubin-Blum et al., 2014a, b; Weidlich et al., 2023) with dispersed bivalve beds, indicative of substantial past and limited present activity (Beccari et al., 2020). However, hotspots of marked discharge of gas-rich brine, forming small (< 40 m wide) brine pools, have recently been discovered (Herut et al., 2022). The sediments at the Palmahim Disturbance seep chemotones do not host the typical seep fauna; rather, they are inhabited by dense populations of a burrowing ghost shrimp, Calliax lobata, which alter the morphology of the sediment surface for tens of meters away from the seepage hotspots (Basso et al., 2020; Beccari et al., 2020; Makovsky et al., 2017). Similar burrowing is prominent in the periphery of SEMS seeps, as has been observed, for example, in the hemipelagic sediments near the Amon mud volcano at the Nile deep-sea fan (Blouet et al., 2021; Ritt et al., 2011). At the Palmahim Disturbance, the sediments in the seep periphery are characterized by elevated nutrient fluxes and oxygen consumption as well as increased microbial activity compared with the background stations (Sisma-Ventura et al., 2022).

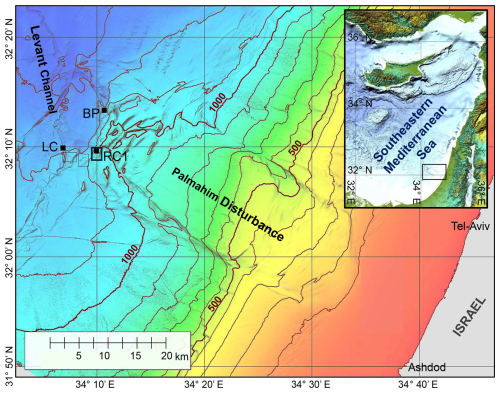

Figure 1A bathymetric map of the Palmahim Disturbance and its vicinity (color-coded and contoured with a 100 m spacing). This study is focused on seafloor gas seeps in the ridge–crest pockmark system (RC1) at the southwestern edge of the disturbance, the proximate part of the Levant Channel (LC), and the brine pool (BP) area to the north. Black dots mark the sites of box-core sampling, and the black frames outline the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) surveying analysis maps of Fig. 2d and e.

Thus, microbes likely play a key role not only in hotspots of seepage but also in the seep ecotones. However, to date, most studies on seep microbiota focus on seepage hotspots. At these hotspots, seep ecosystems support diverse assemblages of microorganisms, with cosmopolitan distribution and key biogeochemical functions (Ruff et al., 2015; Teske and Carvalho, 2020). At the seepage hotspots, microbes catalyze key processes such as anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM), sulfate reduction, and chemosynthesis (Boetius and Wenzhöfer, 2013; Knittel and Boetius, 2009; Teske and Carvalho, 2020). The marked primary productivity at seeps may boost secondary microbial productivity, via, for example, the fermentation of organic macromolecules (Zhang et al., 2023). Such microbial communities are characteristic of Palmahim Disturbance seepage hotspots (Rubin-Blum et al., 2014b). However, little is known about the diversity and function of microbial communities that occupy the seep periphery, in the SEMS seeps in particular.

Here, we aimed to understand the extent and functionality of the burrowed sediments at Palmahim Disturbance seep chemotones. Thus, we mapped the bioturbation using analyses of video collected with remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and high-resolution acoustic mapping with synthetic aperture sonar (SAS), mounted on an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV). Hypothesizing that the bioturbated sediments at Palmahim Disturbance seep chemotones host unique microbial communities, which may function synergistically to exploit limited fluxes of seep carbon, we investigated their diversity and function using metagenomics analyses of samples collected at the seep periphery (Sisma-Ventura et al., 2022). We investigated the activity of chemotone microbes using the leucine uptake assay and evaluated their ability to fix dinitrogen. Previous studies have suggested that burrowing shrimp, in particular ghost shrimp (Axiidea), garden and groom their burrows by incorporating organic matter into the walls through mucus excretions, creating microniches within the burrow walls (Abed-Navandi et al., 2005; Astall et al., 1997; Coelho et al., 2000; Dworschak et al., 2006; Gilbertson et al., 2012; Laverock et al., 2010; Papaspyrou et al., 2005). In seeps, burrowing may enhance carbonate precipitation in areas with very low methane flux and/or diffusive seepage (Weidlich et al., 2023). Therefore, we hypothesized that the burrowing activity of C. lobata can alter the diversity and functionality of these microbes, introducing new metabolic adaptations and handoffs. Hence, we focused on the specific sediment layers where burrows were present.

2.1 Exploration of the Palmahim Disturbance gas seeps

The Palmahim Disturbance toe region comprises a set of hundreds of meters high and ∼ 1 km wide fold ridges and is bounded to the west by the ∼ 500 m wide and ∼ 40 m deep easternmost channel of the deep-sea fan of the Nile River, the Levant Channel (Gvirtzman et al., 2015). We investigated three seepage domains: (i) hundreds of meters wide pockmark systems at the crest of three ridges marking the southwest of the Palmahim Disturbance toe, with a particularly large pockmark at the crest of the eastern ridge (RC1; Fig. 1); (ii) elongate pockmarks along the sides of the Levant Channel (LC; Fig. 1); and (iii) brine pools at the northern part of Palmahim Disturbance toe region (BP; Fig. 1). We collected sediment samples and survey data during several cruises to the Palmahim Disturbance, offshore of Israel, comprising the following: (i) the E/V Nautilus cruise in 2011 (Coleman et al., 2012); (ii) the EUROFLEETS2 SEMSEEP cruise in the framework of the EUROFLEETS2 expeditions in 2016, aboard R/V AEGAEO (Basso et al., 2020; Makovsky et al., 2017); and (iii) the R/V Bat-Galim cruises in 2020–2023 (Herut et al., 2022; Rubin-Blum et al., 2024; Sisma-Ventura et al., 2022). In the latter cruises, sediment collection was supplemented with an AUV-based seafloor survey using a SAS (MINSAS 120, Kraken Robotics Inc.), providing a backscatter image of the seafloor with a constant ultrahigh-definition 3 cm × 3 cm resolution across a 120 m wide swath along each side of the AUV track. The SAS data were collected in the framework of a 70 km long reconnaissance survey that traversed the Palmahim Disturbance toe region. SAS images collected in some specific areas were manually correlated with the relevant ROV videos by identifying specific seafloor morphologies.

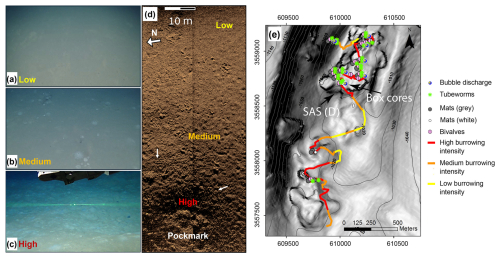

2.2 Burrowing quantification

The high-definition (HD) video data of three consecutive dives of the E/V Nautilus 2011 cruise to the three ridge–crest pockmarks in the southwestern part of the Palmahim Disturbance toe (RC1, Fig. 1) were systematically analyzed using an ArcGIS desktop (Esri). The intensity of burrowing was semi-quantified (low, medium, and high density of burrowing mounds), within the video recordings of the ROV camera's field of view, and in SAS data (Fig. 2a–d). The three levels were as follows: (i) low – where the seafloor is generally smooth with the possible presence of a few sporadic burrowing mounds; (ii) medium – when multiple burrowing mounds are continuously viewed; and (iii) high – where burrowing mounds are pervasive across the majority of the field of view. The analysis mapped markers of active seepage, including bubble discharge, bacterial mats, chemosynthetic fauna, and seafloor burrowing. The results were combined to generate a map of seepage indicator distribution (Fig. 2e).

Figure 2Classification and mapping of burrowing intensities and their correlation with indicators of active seepage. ROV images of low (a), medium (b), and high (c) burrowing intensities are shown (similar scales, with the green laser beams in panel c being 7.5 cm apart). (d) Synthetic aperture sonar (SAS) backscatter image of the gradient in burrowing intensity from low (top right) to high (bottom) inside a small pockmark at the edge of the RC1 pockmark system. The burrowing mounds are observed as a decimeter-scale dotted dark–bright pattern (white arrows show examples). (e) Map of classified burrowing intensities and active seepage indicators along E/V Nautilus 2011 ROV survey tracks of a ridge–crest pockmark system RC1, overlaid on the contours of bathymetry (at 5 m spacing) and a grayscale map of the bathymetric gradient (high gradients are darker). Locations of the SAS swath in panel (d) and the cored area are marked by black arrows in panel (e).

2.3 Sediment sample collection

Sediments were sampled using box corers, targeted with an ultra-short baseline (USBL) positioning system in the large ridge–crest pockmark RC1 (AG16-17BC1 (2016), RC20-BC1 (2020), and RC20-BC2 (2020); all within ∼ 20 m positioning accuracy of 32°09.60′ N, 34°10.00′ E; water depth circa 1035 m) (Fig. 1, Table 1). An additional RC20-Flare1 core was collected within RC1, corresponding to a gas flare detected by acoustics (32°9.76′ N, 34°10.12′ E). In 2016, we collected an additional core within the pockmark in the western flank of Levant Channel (LC; AG16-15BC1; 32°09.88′ N, 34°06.88′ E; water depth 1261 m). In 2023, we collected two box-core samples near the Palmahim Disturbance brine pool site (BP; BP22-BC1 and BP22-BC2; 32°13.33′ N, 34°10.72′ E and 32°13.32′ N, 34°10.71′ E, ∼ 10 and 20 m away from the brine pool, respectively; water depth ∼ 1135 m). The sediments in each of the box corers were subsampled using ∼ 40 cm long push corers (60 mm diameter) and sectioned on board at 1 cm resolution. We also collected distinct samples from the same section, based on the black coloration of the burrow walls and bright coloration of the ambient sediments. The sections for DNA extractions were frozen and kept at −20 °C until further processing. Additional push cores were collected from the same box-core samples, kept intact, and stored at 4 °C for X-ray computerized tomography (CT) scanning.

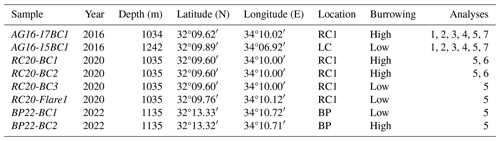

Table 1Box-core samples used in this study. RC1 is a ridge–crest pockmark system, LC is the Levant Channel, and BP is a brine pool area (Fig. 1). The following analyses were performed: CT scan (1), nutrient profiles (2), flow cytometry (3), activity measurements (4), amplicon sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene (5), metagenomics, (6), and dinitrogen fixation (7).

2.4 Computerized tomography (CT) scans

We performed computer tomographic scanning using a Siemens Somatom Definition AS62 installed at the Institute of Forensic Medicine (University of Bern, Switzerland). Whole core sections were scanned at a spatial resolution of 300 µm, using energies of 120 kV and effective power of 35 mA. Image analyses and processing (combined single thresholding and watershed segmentation, labeling, and quantification) were done using Avizo 9.4 (FEI – Thermo Scientific). Before segmentation and labeling, images were filtered using a nonlocal mean filter. Bioturbation features have been segmented and quantified for each slice across the full scanned volume. Results are presented as the volume percentage vs. depth (each 400 µm from top to bottom). For the overall core section, bioturbation has been described according to the bioturbation index (BI) (Reineck, 1963) and assessed qualitatively (taking a descriptive approach) for approximately every 10 cm interval of the box core. This method assesses bioturbation on a scale from 0 to 6, where 0 indicates 0 % bioturbation, 1 corresponds to 1 %–4 % bioturbated sediment, 2 corresponds to between 5 % and 30 % bioturbation, 3 corresponds to between 31 % and 60 % bioturbation, 4 corresponds to between 61 % and 90 % bioturbation, 5 corresponds to between 91 % and 99 % bioturbation, and 6 reflects 100 % bioturbation. The shape and size of the burrows were described according to the length and thickness/diameter of the burrowing and their orientation (Jumars et al., 2007).

2.5 DNA extraction and sequencing

DNA was extracted from the sediment (∼ 500 mg wet weight) samples with the legacy DNeasy PowerSoil kit (Qiagen, USA) or the FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (MPBio, USA) with FastPrep-24™ Classic (MP Biomedicals, USA) bead-beating to disrupt the cells (two cycles at 5.5 m s−1 with a 5 min interval). The V4 region (∼ 300 bp) of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified from the DNA (∼ 50 ng) using the 515Fc/806Rc primers (5'- GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA, 5'- GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT) amended with either CS1/CS2 tags (2020 samples) or SP1/SP2 tags (2023 samples) (Apprill et al., 2015; Parada et al., 2016). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 45 s, 30 cycles of denaturation (94 °C for 15 s), annealing (15 cycles at 50 °C and 15 cycles at 60 °C for 20 s), and extension (72 °C for 30 s) (Sisma-Ventura et al., 2022). Library preparation from the PCR products and sequencing of 2x250 bp Illumina MiSeq reads was performed by Hylabs (Israel) in 2020 and Syntezza Bioscience (Israel) in 2021. Five metagenomic libraries were constructed and sequenced to a depth of ∼ 70 million 2x150 Illumina reads at Hylabs (Israel) (two libraries from the burrows: 9–10 cm section in RC20-BC1 and 8–9 cm section in BOX 2; three control libraries from RC20-BC1: 1, 2–5, 25–29 cm below sediment surface).

2.6 Bioinformatics

Demultiplexed paired-end reads were processed in the QIIME2 V2021.4 environment (Bolyen et al., 2019). Primers and sequences that did not contain primers were removed with Cutadapt (Martin, 2011), as implemented in QIIME2. Reads were truncated based on quality plots, checked for chimeras, merged, and grouped into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) with DADA2 (Callahan et al., 2016), as implemented in QIIME2. The amplicons were classified with a scikit-learn classifier that was trained on the Silva database V138 (16S rRNA; Glöckner et al., 2017). Mitochondrial and chloroplast sequences were removed from the 16S rRNA amplicon dataset. Downstream analyses were performed in R V3.6.3 (R Core Team, 2024), using the phyloseq (McMurdie and Holmes, 2013) and ampvis2 (Andersen et al., 2018) packages.

Metagenomic libraries were processed using ATLAS V2.3 (Kieser et al., 2020), employing the SPAdes V3.14 de novo assembler (Prjibelski et al., 2020) with –meta -k 21,33,66,99 flags. We used metaBAT2 (Kang et al., 2015) and maxbin2 (Wu et al., 2015) as binners and the DAS Tool (Sieber et al., 2018) as a final binner for metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) curation. MAGs were dereplicated with dREP (Olm et al., 2017), using a 0.975 identity cutoff. We used CheckM2 to assess the completeness of MAGs (Chklovski et al., 2023), assigned taxonomy with GTDB-Tk V1.5 and GTDB R202 taxonomy (Chaumeil et al., 2020), and annotated them with the SEED and the rapid annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST) (Overbeek et al., 2014). Identification of key functions was based on the hidden Markov model (HMM) profiles within METABOLIC (Zhou et al., 2022). Metagenomic reads and MAGs were deposited to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under project no. PRJNA1072319.

2.7 Prokaryote abundance

Total prokaryote abundance (bacteria and archaea) was quantified from both the upper sediment (top 18–25 cm, every ∼ 2 cm) and above the seabed (50 m, every 5–20 m) using flow cytometry. Sediment samples (∼ 3 g) were collected into sterile 15 mL plastic tubes containing 6 mL of pre-filtered seawater (0.2 µm) from the same station, fixed with a flow-cytometry-grade glutaraldehyde solution (1 % final concentration, G7651, Sigma-Aldrich), and kept at 4 °C until analysis (which occurred within ∼ 2 weeks). At the lab, the chelating agent sodium pyrophosphate (final concentration 0.01 M) and the detergent TWEEN-20 (final concentration 0.5 %) were added. The samples were then vortexed at 700 rpm, placed in an ultrasonic water bath (VWR, Symphony) for 1 min to disperse the grain-attached prokaryotic cells into the liquid seawater phase, and left overnight at 4 °C. At the lab, subsamples were stained for 10 min in the dark with 1 µL SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems cat. no. S32717) per 100 µL of the sample. The samples were analyzed by an Attune® acoustic focusing flow cytometer at a flow rate of 25 µL min−1. Taxonomic discrimination was based on cell side scatter, forward scatter, and green fluorescence. Cell abundance was normalized to the sediment's dry weight.

2.8 Heterotrophic activity

Samples of ∼ 3 g were collected across the upper sediment layer (18–25 cm; see Sect. 2.5), resuspended in 3.5 mL of pre-filtered seawater/porewater (0.2 µm), and spiked with 500 nmol L−1 (final concentration) of [4,5-3H]-leucine (specific activity 160 Ci mmol−1, PerkinElmer, USA). Porewater from 5 to 25 cm was first degassed from O2 by bubbling N2 into it for ∼ 10 min, thereby keeping it anoxic. The samples were incubated in the dark for 4–5 h at in situ temperatures. At the end of the incubation, 100 µL of 100 % trichloroacetic acid solution was added to stop any microbial assimilation of leucine, followed by sonication (VWR, Symphony) for 10 min to remove bacterial biomass from the sediment grains (Frank et al., 2017). The bacterial biomass was extracted from the liquid phase and divided into three 1 mL aliquots. For the seawater samples, the collected material was added to 100 nmol L−1 of [4,5-3H]-leucine (same working solution as above, final concentration), incubated for 4–5 h in the dark, and 100 µL of 100 % trichloroacetic acid solution was added to stop the incubation. The sediment's liquid extracts were then processed using micro-centrifugation (Smith et al., 1992). Disintegration per minute (DPM) from each sample was read using a Packard Tri-Carb 2100 liquid scintillation counter. A conversion factor of 1.5 kg C mol−1 with an isotope dilution factor of 2.0 was used to calculate the carbon assimilation rate (Simon and Azam, 1989). Blanks included sediments spiked with [4,5-3H]-leucine and with the immediate addition of trichloroacetic acid that were incubated and processed under the same conditions as described above.

2.9 Nitrogen fixation rates

We evaluated N2 fixation rates in the top sediment layer (upper 3 cm) and overlying seawater (∼ 1 m above the seabed) in push cores AG16-15BC1 and AG16-15BC1, sampled in 2016. The sediment samples (∼ 150 mL) were placed in 250 mL gas-tight bottles filled with porewater from the same sediment layer (∼ 100 mL) and 15N2-enriched seawater (10 % of the water volume), as previously described (Mohr et al., 2010). In short, 15N2 gas (99 %, Cambridge Isotopes) was injected at a 1:100 ratio (v:v) to filtered (0.2 µm, PALL) and degassed (MiniModule G543) seawater (FSW) or porewater (FPW) and shaken vigorously for ∼ 12 h to completely dissolve the 15N2 gas. The sample bottles were incubated in the dark at an ambient temperature of ∼ 15 °C for 168–172 h. After incubation, the bottles were vortexed for 30 min at 700 rpm, placed in an ultrasonic water bath (Symphony, VWR) for an additional 10 min, left on the bench for ∼ 1 h, and filtered using pre-combusted GF/F filters (following 100 µm mesh pre-filtration to remove large aggregates). For the overlying seawater measurements, 4.5 L was placed in darkened Nalgene bottles with 15N2-enriched seawater (10 % of the water volume). The bottles were incubated for 72 h at ambient temperature, and the content was filtered onto pre-combusted GF/F filters. Triplicate bottles without 15N enrichment were used to determine the natural abundance of the particulate matter at each station. The filters were kept at −20 °C in sterile Petri plates until dried at 60 °C overnight and analyzed on an NC 2500 elemental analyzer (CE Instruments) interfaced with a Thermo Fisher Scientific Finningan DELTAplus XP isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS). For isotope ratio mass spectrometry, a standard curve to determine N mass was generated for each sample run. Based on natural abundance, N mass on the filters, incubation times, and precision of the mass spectrometer, our calculated detection limit for 15N uptake was 0.01 . N2 fixation rates were calculated based on Eqs. (1) and (2), after Mulholland et al. (2006), using the N solubility factors of Weiss (1970).

Here, Atom %(final) and Atom %(t0) represent the fractional 15N enrichment of the particulate nitrogen (PN) pool after the incubation and of the ambient seawater, respectively; is the fractional 15N enrichment of the N2 source pool; PN(final) is the concentration of the particulate nitrogen at the end of the incubation; and Δt is the incubation length (72 h for the seawater and 168–172 h for the sediment incubations).

3.1 Burrowed sediments are concentrated around Palmahim Disturbance seepage hotspots

While burrow mounds are rare on the generally smooth seafloor in the bathyal SEMS, these seabed features were particularly abundant at the toe region of Palmahim Disturbance. The seabed burrow extensions appeared in two main forms: (i) decimeter-scale circular sediment mounds with mostly bright color, often similar to that of the surrounding seafloor, and (ii) holes that were several millimeters to decimeters in scale, commonly surrounded by scrape marks (Fig. 2). The borrow density varied from only a few sporadic borrows (low intensity) to a complete convolution of the seafloor within an ROV field of view (high intensity; Fig. 2). In the regions of intense burrowing, we observed a rugged seafloor with localized depressions and mounds (bright color and, often, dark heaps).

The SAS surveying and the video analysis and mapping of active seepage markers along the ROV dive tracks revealed that bioturbation intensities increased towards the inner part of a pockmark (Fig. 2e). The high burrowing intensity was often associated with the presence of seepage indicators, including microbial mats, bubbles, or chemosynthetic fauna. Within the large pockmark RC1, nearly the entire soft sediment seafloor was intensely bioturbated, except in the vicinity of rock outcrops. The domes of intensely burrowed sediments reached over 1 m in diameter and sometimes overlapped neighboring ones. Our observations suggest that burrowing is markedly enhanced by nearby seepage, whereas the burrowed areas largely exceed the vicinity of visible seepage hotspots, often beyond 100 m distances.

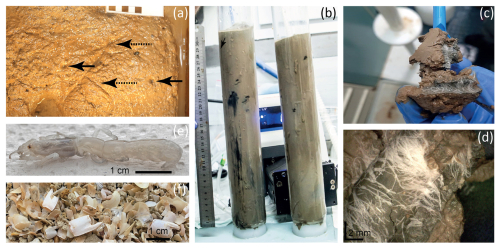

3.2 Calliax lobata ghost shrimp inhabit near-seep large burrows

Box-core sediment samples within the RC1 area (AG16-17BC1, RC20-BC1, and RC20-BC1) were intensely burrowed (Fig. 3). The sediment surface within these samples appeared fluffy with decimeter-scale mounding and multiple holes and scratches (Fig. 3a). We observed sporadic black coloration at various horizons, indicative of large, ∼ 0.5 cm wide burrows (Fig. 3b–d). Random sieving of leftover sediments in the respective box corer with a 2 mm mesh revealed that macrofauna was usually scarce, except for six live specimens of Calliax lobata ghost shrimp, measuring ∼ 5 cm long and ∼ 1 cm wide (Fig. 3e). C. lobata claws consistently dominated the > 2 mm sieved fraction, varying in size up to ∼ 1 cm long and ∼ 5 mm wide (Fig. 3f), following previous observations in the same area (Beccari et al., 2020). Therefore, we suggest that C. lobata plays a key role in near-seep sediment burrowing.

Figure 3Burrows of the ghost shrimp Calliax lobata near active seepage sites within the Palmahim Disturbance in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Panel (a) presents the seafloor, as exposed in the AC16-17BC1 box core (RC1 area, 2016), highlighting burrow openings (black arrows) and scratches (dashed arrows) on the sediment surface. Panel (b) is an image of the RC20-BC1 and RC20-BC2 cores (RC1 area, 2020), showing dark coloration of burrows, unusual for the ambient sediments. Panels (c) and (d) show a zoomed-in view of the burrows of the RC20-BC1 and RC20-BC2 cores, highlighting the presence of large filamentous microbes. Panel (e) presents a live C. lobata specimen found in AC16-17BC1. Panel (f) shows a multitude of C. lobata claws recovered through sporadic sieving (2 mm mesh) of AC16-17BC1.

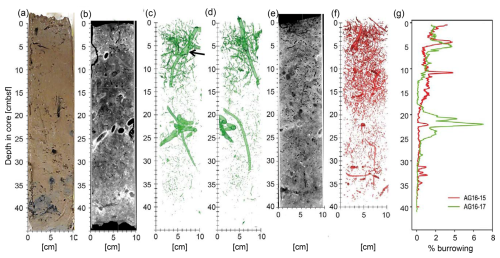

Figure 4Burrowing in AG16-15BC1 and AG16-17BC1, as detected by computerized tomography (CT) scans. (a) A vertical section through a sub-core of box-core AC16-17BC1 cut and imaged immediately after sampling. (b) A vertical section through the 3D CT scan of another sub-core of AC16-17BC1 (standard medical CT display in which higher relative X-ray intensities are darker and low intensities are brighter, depicting lower and higher material densities, respectively). Panels (c) and (d) show two perpendicular 3D displays of segmentation of the relatively vacant (high-intensity) burrows, imaged in the CT scan of the same core (in panel b). (e) A vertical section through the 3D CT scan of a sub-core of AC16-15BC1 (displayed as in panel b). (f) A 3D display of AC16-15BC1 segmentation of the vacant (high-intensity) burrows. (g) Graphs comparing the volumetric percentage of relatively vacant burrows in CT-scanned sub-cores of AC16-17BC1 (green) and AC16-15BC1 (red), as estimated based on the respective segmentation results (in panels c, d, and f).

CT scans of the AG16-17BC1 and AG16-15BC1 cores showed considerable burrowing (Fig. 4). The burrows were imaged as lower-density to empty, subvertical to subhorizontal, linear and helicoidal, and generally cylindrical tubes that varied in diameter between ∼ 1 to ∼ 10 mm. Larger burrows were usually surrounded by bright halos or rings of relatively dense material. Several burrows had chamber-like regions (Fig. 4c). Pervasive tone variations across the CT scans suggest the impact of multiple generations of burrowing that convolute a major part of the cored sections, with more pronounced tone contrasts imaging the most recent generation of burrowing.

Segmentation of the CT images captures these more pronounced contrasts, marking the current burrowing activity. Core AG16-17BC1 (47 cm recovery) was composed of homogeneous oxidized clayey sediments with a high number of shell fragments and pteropod fragments. In this core, the burrow segmentation had an average value of 0.9 %, with a maximum of 7.0 % of the total sediment volume. We noted the highest burrowing at 5 (∼ 4 %) and between 20–22 (∼ 7 %). Between 0 and 15 , the sediments generally displayed sparse burrowing (BI = 1), with a few discrete traces. Discrete traces were composed of elongated subvertical burrows with a length of approximately 3 cm and a diameter of ∼ 1–5 mm as well as helicoidal burrows that were similar in size. One large vertical burrow with a length of 12 cm and diameter of 1 cm was present from the surface to 15 . From 15 to 25 , the overall BI was again close to 1, with a few discrete traces composed of very small subvertical burrows of 1 cm length and 1 mm diameter as well as two large-sized burrows of 15 cm length (1 cm diameter) and 6 cm length (4 cm thickness), respectively. From 25 to 41 , no clear bioturbation features were quantified (BI = 0).

Core AG16-15BC1 was composed of oxidized clayey sediment with minor horizontal layering. The surface was highly bioturbated, showing a wavy and slightly disturbed surface with small mounds as well as a high number of pteropod shells. The average volume percentage of burrowing was 0.7 %, with peak burrowing at 4 and 10 (up to 4 %). The box-core sediments (0–40 ) present overall sparse burrowing (BI = 1). From 0 to 20 , a few discrete traces (BI = 1) were composed of elongated subvertical burrows of 5 cm in length and 0.5 cm in diameter and horizontally elongated burrows of 6 cm in length and 0.5 cm in diameter. Moreover, small curved burrows were present (1 cm in length and 1–2 mm thick). From 20 to 35 , a few discrete traces (BI = 0–1) were composed of vertically elongated burrows of 5 cm length and 2–3 mm diameter as well as small curved burrows of 2 cm length and 1–2 mm thickness with a subvertical orientation. The amount of bioturbation decreased towards 35 . From 35 to 40 , no bioturbation (BI = 0) was visible.

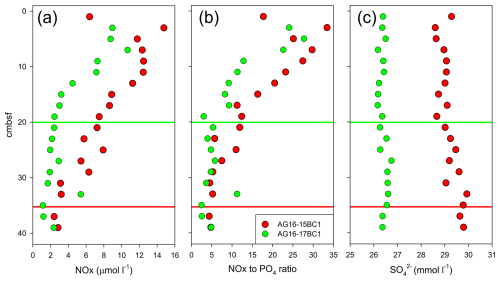

Figure 5Porewater characteristics in cores AG16-15BC1 and AG16-17BC1: (a) nitrate + nitrite (NOx) concentration; (b) NOx-to-phosphate ratio; and (c) sulfate concentration. Red and green lines indicate the depths at which NOx concentrations appear to stabilize.

Based on the burrow morphology, three distinct burrow traces/ichnofabrics were distinguished: (i) large (≥ 5 mm wide) vertical to subhorizontal burrows (Thalassinoides); (ii) smaller (2–5 mm wide) vertical and subhorizontal burrows forming a dense network (Ophiomorpha); and (iii) small (≤ 2 mm wide) curved and helicoidal burrows (Gyrolithes) (Seilacher, 2007). The presence of significant subhorizontal segments and chambers in the Thalassinoides burrows suggests that they were created by arthropods. First, it is unlikely that subhorizontal burrows would be created by a bivalve, which would usually produce vertical to oblique burrows (Knaust, 2015; Trueman et al., 1966). Second, arthropods, in particular decapods, excavate chambers that allow them to change direction within their burrows (Coelho et al., 2000; Hembree, 2019; Stamhuis et al., 1997). In turn, the sparse spacing of the burrows also suggests a decapod rather than worm-like organisms, which often produce tightly packed burrows (Seilacher, 2007). We suggest that C. lobata is the primary inhabitant of the two larger Thalassinoides and Ophiomorpha burrow morphologies, prominent in AG16-17BC1, based on the marked abundance of these organisms and matches in size. At this stage, it is impossible to determine the provenance of the smaller Gyrolithes-type burrows, possibly worm-like organisms.

3.3 Burrowing alters geochemical processes at seep chemotones

Our data indicate that intense near-seep burrowing can affect geochemical processes via the exchange of solutes across the sediment and the overlying water. The measurements of nutrient concentrations indicate that depth profiles in cores AG16-15BC1 and AG16-17BC1 show different penetration depths and standing stocks, correlated with the presence of burrows (we assumed negligible nitrite concentrations; Fig. 5a). In core AG16-15BC1, we observed an increasing trend in the concentrations from ∼ 35 cm upwards. In comparison, core AG16-17BC1 showed significant enrichment above 20 cm depth. Assuming steady-state conditions, the amount of in the upper 35 cm of core 15 was double that of core 17 (∼ 260 and ∼ 105 nmol , respectively). Nitrification driven by ammonia-oxidizing archaea is the key process in background sediments of the abyssal SEMS (Rubin-Blum et al., 2022). However, in the seepage area, this process may be regulated by burrowing, altering the diffusive access of ammonium from the ambient sediment and oxygen supplies via irrigation by the burrow inhabitant (Kristensen and Kostka, 2005). Thus, macrofaunal burrowing near the sediment surface may aid nitrification (Glud et al., 2009; Mayer et al., 1995). The gradual upward change in the ratios (Fig. 5b) further supports the enhancement of nitrification. Nonetheless, C. lobata burrowing may enhance denitrification (removal of nitrate), which has been suggested to be enhanced and correlated with the presence of burrowing macrofauna (Nielsen et al., 2004). In core AG16-17, denitrification is likely prominent, given the rapid depletion of nitrate (Fig. 5a). Thus, our results are in line with the previous observations of infauna and depth distribution at 1450 m water depth using precise microprofiling, which suggested that burrow irrigation may stimulate both the production and consumption (Glud et al., 2009).

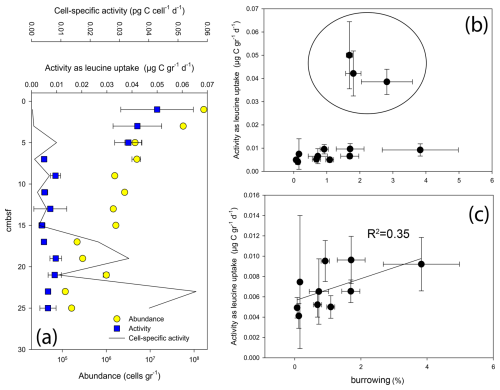

Figure 6Abundance and activity of microbes in core AG16-17BC1: (a) abundance and activity profiles; (b) activity vs. burrowing; and (c) activity vs. burrowing – upper 5 cm removed.

Previous observations suggest that nitrifying bacteria have a positive correlation with Fe(III) and a negative correlation with dissolved sulfide, which inhibits nitrification (Kristensen and Kostka, 2005). Experimental studies supported field data, confirming that increased amounts of Fe(III) react with sulfide, intensifying the effect of nitrification–denitrification processes. In both cores, the depth distributions of porewater concentrations show values slightly lower than the ambient seawater (31 mM; Herut et al., 2022), suggesting the occurrence of sulfate reduction (Fig. 5c). Nonetheless, the sulfate levels in core AG16-17BC1 are consistently lower than in AG16-15BC1, indicating that sulfate reduction in this core, where C. lobata burrows were found, was enhanced. This is in line with previous studies, showing that sedimentary infaunal burrows and irrigation impact the depth distribution of early diagenetic dissolved reactants/electron acceptors (e.g., O2, , and ) and products (e.g., CO2, , and H2S) in porewaters (Aller, 2001; Kristensen and Kostka, 2005; Meile and Van Cappellen, 2003).

Our data suggest that seep chemotones are potential hotspots of dinitrogen fixation. Although we did not measure nitrogen fixation rates directly in the burrows, the 0.02 ± 0.004 estimates in the top 3 cm of the chemotone sediments (AG16-17BC1) were significantly higher than the 0.01 ± 0.005 background values (AG16-15BC1, ANOVA followed by a Fisher least significant difference, LSD, multiple-comparison post hoc test, p = 0.04; Fig. S1a in the Supplement). Given that most putative diazotrophs were found in burrow walls (see below), our results likely underestimate N2 fixation rates in the sediments. These rates were also enhanced in the water column approximately 1 m above the chemotone sediments (0.04 ± 0.01 as opposed to 0.01 ± 0.009 at the control site, ANOVA followed by a Fisher LSD multiple-comparison post hoc test, p = 0.02; Fig. S1b), with different diazotrophic populations found in that habitat compared with those in the sediments (Sisma-Ventura et al., 2022). Altogether, our results suggest that nitrogen cycling at chemotones is substantially altered and that these processes may be boosted by burrowing.

3.4 Burrowing may alter microbial abundance and activity at seep chemotones

Following the previous observations of elevated microbial activity in seep chemotone sediments (Sisma-Ventura et al., 2022), our measurements in core AG16-17BC1 suggest a weak but feasible link between burrowing and microbial activity in these sediments (Fig. 6). While the highest abundance and activity values were found in the upper 5 cm, we observed a substantial variation in activity below 5 cm in this core (Fig. 6a). In sediments deeper than 5 cm, we observed a weak trend linking burrow intensity and the rate of leucine uptake (Fig. 6b and c). We note that activity was not estimated in burrows; rather, it was estimated using random subsamples from the respective sections and, thus, may reflect only partial burrow effects.

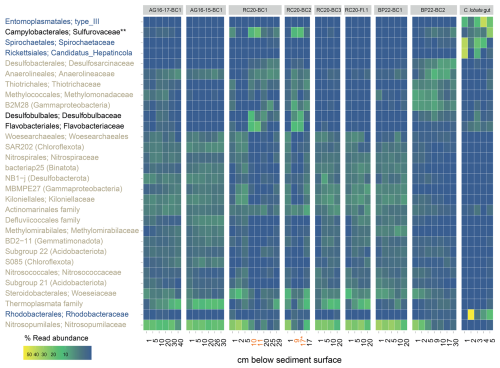

3.5 Seep chemotones host unique microbial communities that are altered by burrowing

Amplicon sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene highlighted the unique microbial communities that existed at seep chemotones (Figs. 7 and S2). These communities markedly differed from those found in seepage hotspots in the same area (Rubin-Blum et al., 2014b) and from those of background sediments in the deep SEMS (Rubin-Blum et al., 2022). We identified different levels of seepage-related perturbations in the sediments. RC20-Flare1 and BP22-BC1 samples represent the poorly disturbed, typical background sediments in the SEMS. The most altered sediments were in RC20-BC1, collected within the vicinity of authigenic carbonate in 2020 (Sisma-Ventura et al., 2022), and BP22-BC2, collected 40 m away from the brine pools in 2022. Ammonia oxidizers, such as Nitrosopumilaceae and Nitrospiraceae, and other microbes prominent in background SEMS sediments, such as Thermoplasmata and Binatota lineages (Rubin-Blum et al., 2022), were depleted in these profiles, whereas the putative methane oxidizers, sulfate reducers, and chemoautotrophs were found (Figs. 7 and S2). In particular, the anaerobic methane oxidizers ANME-1 were found at depths below 25 and 5 cm in RC20-BC1 and BP22-BC2, respectively. The aerobic Methylomonadaceae methane oxidizers were prominent in the upper sections of these cores. The read abundance of Desulfosarcinae sulfate reducers increased with distance from the sediment surface, and the putative chemoautotrophs Thiotrichales were often found in these samples. This provides evidence of chemosynthetic activity in these chemotone sediments, following previous observations of enhanced microbial activity (Sisma-Ventura et al., 2022).

Figure 7Read abundance of the top 30 most prevalent prokaryote taxa at the family level, in Palmahim sediments (see Table 1) and the hindgut of the ghost shrimp Calliax lobata (black: enriched in burrows; blue: enriched in C. lobata; brown: enriched in sediments). Sediment depths at which burrow microbes were collected are highlighted in orange. ∗ Both samples are from the 16–17 cm section, but the first one is taken from the burrow and the second from background sediments. Abundant in burrows and associated with the C. lobata hindgut.

These results are in line with visual inspection and microscopic observations that revealed the following: (i) black coloration of burrow walls, potentially indicative of the precipitation of minerals following sulfate reduction, and (ii) large, white filaments typical of giant sulfur bacteria inhabiting the burrow inner perimeter (Ionescu and Bizic, 2019) (Fig. 3c and d). According to amplicon sequencing, the key families that were prominent specifically in the burrow subsamples included Desulfobulbaceae, known mainly as sulfur and/or cable bacteria (Trojan et al., 2016); Sulfurovaceae, which are autotrophic sulfur oxidizers, often found in association with marine invertebrates (Bai et al., 2021; Hui et al., 2022); and Flavobacteriaceae, which are versatile degraders of macromolecules, especially carbohydrates (Chen et al., 2021; Gavriilidou et al., 2020). Similar key taxa appear to be associated with bioturbation in other habitats, such as the intertidal flats (Fang et al., 2023). These findings lead to the hypothesis that unique metabolic handoffs take place within the burrows, altering carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycling.

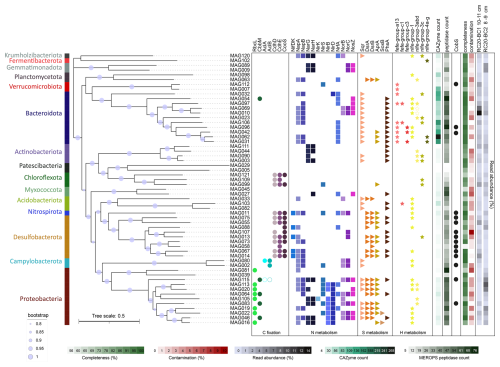

Based on two DNA samples extracted specifically from burrows in cores RC20-BC1 and RC20-BC2, we curated 58 high-quality MAGs spanning 15 phyla (57 bacteria and 1 archaea; median quality 92 % and median contamination 2 %; Fig. 8). We observed considerable genotype diversity within Bacteroidota, Desulfobacterota, and Proteobacteria phyla (mostly Gammaproteobacteria in the latter). A total of 51 MAGs were found in both samples, although the read abundance patterns often differed. In particular, we found the putative autotrophic sulfur oxidizers Thiohalobacteraceae (reclassified as UBA9214 by GTDB) and Thiomargarita in RC20-BC2, in which the giant bacteria were observed, whereas Thiohalomonadaceae, Sedimenticolaceae, and Sulfurimonadaceae (Campylobacterota) were found in RC20-BC1. Flavobacteriaceae species (mainly the CG1-02-35-72 lineage) were abundant in both samples, but they were most dominant in RC20-BC1 (14.4 % read abundance). Desulfobacterota comprised the Desulfobacterales (e.g., Desulfobacula) and Desulfobulbales lineages BM004 and BM506, with the latter associated with the dissimilatory reduction in perchlorate (Barnum et al., 2018), as well as Desulfocapsa (4.7 % read abundance in RC20-BC1), known to specialize in the disproportionation of inorganic sulfur compounds (Finster et al., 2013; Ward et al., 2021). Themodesulfovibrionia UBA6902 (Nitrospirota) was also found in RC20-BC2 (2.2 % read abundance). In RC20-BC1, Anarerolineales UBA11858 was prominent (MAG 99, 4.5 % read abundance). Gemmatimonadetes species (MAGs 9 and 89, ∼ 5 % read abundance each) were abundant in RC20-BC2. We hypothesized that these dominant lineages can perform an array of metabolic functions, using a range of substrates and electron donors/acceptors, markedly altering the functionality of ecotones compared with the unaltered bathyal sediments in the SEMS.

Figure 8Phylogeny, taxonomy, and key functions of bacteria, based on the reconstruction of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from Calliax lobata burrows. FastTree phylogeny is based on the GTDB-Tk marker gene set. Functions were assigned using the METABOLIC hidden Markov model (HMM) set. Empty circles and stars indicate the functions discovered through manual annotation of functions, using SEED and NCBI BLAST.

3.6 Metabolic handoffs at burrow walls may fuel dark productivity

Metagenomics suggest that various gammaproteobacterial lineages may fix carbon via the Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) cycle, given the presence of cbbLS and/or cbbM genes encoding the form-I and form-II ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO), respectively (Fig. 8). In agreement with previous studies (Flood et al., 2016), Thiomargarita encoded not only the form-II RubisCO but also the form-II ATP citrate lyase, indicating the potential to fix carbon via more than one pathway (Rubin-Blum et al., 2019). Sulfurimonadaceae (Campylobacterota) encoded the form-I ATP citrate lyase, needed for carbon fixation via the reverse tricarboxylic acid cycle (rTCA). Proteobacteria and Campylobacterota may fuel carbon fixation based on dissimilatory sulfur cycling, encoding proteins needed for the oxidation of reduced sulfur compounds, such as Sqr, DsrAB, and AprAB; components of the Sox system; and the PhsA, a key protein in thiosulfate disproportionation (Anantharaman et al., 2018; Finster, 2008) (Fig. 8). These lineages may respire oxygen, or denitrify, as indicated by the frequent occurrence of genes needed for dissimilatory nitrogen cycling – e.g., those encoding Nap and Nar (nitrate reduction); NirK, NirS, and NirBD (nitrite reduction, as well as NrfA for dissimilatory nitrite reduction to ammonia, DNRA); NorBC (nitric oxide reduction); and NosZ (nitrous oxide reduction to dinitrogen) (Fig. 8).

Sulfur cycling in marine sediments can be driven by fermentation products, such as hydrogen, acetate, butyrate, and lactate (Campbell et al., 2023; Ruff et al., 2023). Similar to groundwater communities (Ruff et al., 2023), the dominant Bacteroidota are the likely key fermenters of macromolecules in the burrows (Fig. 8). These ubiquitous degraders of macromolecules, such as complex glycans (Fernández-Gómez et al., 2013; Martens et al., 2008, 2009; Ndeh and Gilbert, 2018), encode carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) that are often organized in polysaccharide utilization loci (PULs), with typical SusCD transporters (Grondin et al., 2017; Martens et al., 2009; Reeves et al., 1996). We found multiple SusCD copies in diverse Bacteroidota MAGs, but we also discovered a multitude of encoded CAZymes as well as peptidases, highlighting the potential of these bacteria to use a broad scale of macromolecules (Fig. 8).

Bacteroidota may ferment macromolecules to produce various substrates, most importantly, hydrogen, as suggested by the presence of Fe–Fe hydrogen-evolving hydrogenases (MAGs 31, 42, 62, 96, and 106; Fig. 8). The highly abundant Flavobacteriales MAGs 10 and 69 did not encode the Fe–Fe or the canonical type-4 H2-evolving hydrogenases. Instead, they encoded hydrogenase I (hyaABCDEF), and, most importantly, an adjacent gene cluster encoding an aberrant putative HoxHYFU nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-dependent hydrogenase, apparently widespread in Bacteroidota (based on multiple NCBI non-redundant (nr) database BLAST hits of HoxH protein in this clade; data not shown). These soluble, oxygen-tolerant, bidirectional hydrogenases described in Ralstonia eutropha H16 (Burgdorf et al., 2006) and cyanobacteria (Appel et al., 2000; Gutekunst et al., 2014) can promote hydrogen evolution in bacteria that ferment sugars (Cheng et al., 2019). We also identified fdhAB genes encoding the NAD-dependent formate dehydrogenase in these Flavobacteriales MAGs, hinting at the potential coupling of formate oxidation and hydrogen evolution. Other genes involved in fermentation, including those needed for acetogenesis and acetate conversion to acetyl-CoA (ack, pta, and acs), were found in all of the Bacteroidota MAGs. Thus, most Bacteroidota that we discovered in burrows, including the dominant CG1-02-35-72 Flavobacteriales lineages, are likely the key fermenters that fuel the cycling of organic matter at the burrow walls.

Hydrogen can directly fuel chemosynthesis, for example, by Campylobacterota, which encode uptake NiFe hydrogenases and often thrive based on hydrogen in hydrothermal vents (Molari et al., 2023). Some Gammaproteobacteria, including the symbiotic Sedimenticolaceae and Thioglobaceae, also use hydrogen as an energy source in chemosynthetic habitats (Petersen et al., 2011). In line with these observations, we identified uptake NiFe hydrogenases in all of the diverse Sedimenticolaceae MAGs (16, 19, 22, 46, and 155) as well as in Thiohalobacteraceae MAGs 20 and 113, hinting that hydrogen is a potential energy source for burrow autotrophs.

In turn, fermentation products can provide electron donors to the Desulfobacterota and Nitrospirota sulfate reducers that likely drive sulfate depletion in these sediments (Fig. 5). A partial or complete Wood–Ljungdahl (WL) pathway was widespread in Desulfobacterota and Nitrospirota as well as in Chloroflexota, suggesting the potential for carbon fixation using energy from dihydrogen oxidation and sulfur reduction (Drake, 1994). Alternatively, some of these organisms may use this pathway for energy conservation during acetoclastic growth (Alves et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2022; Santos Correa et al., 2022). This is in line with the observation of hydrogenogenic fermentation and hydrogenotrophic sulfate reduction that co-occur in anoxic sandy sediments (Chen et al., 2021). These interactions between Bacteroidota and Desulfobacterota are not limited to marine sediments; for example, they also facilitate dihydrogen turnover in the human gut (Gibson et al., 1993; Thomas et al., 2011; Wolf et al., 2016). The resulting sulfide fluxes may further fuel the productivity of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria.

In summary, our results suggest the presence of productive burrow communities that cycle carbon, sulfur, and nitrogen, potentially through the turnover of hydrogen or other fermentation products. Examples of similar communities, comprising Bacteroidota degraders of macromolecules, sulfate reducers (Desulfobacterota and others), and chemotrophs (mainly Campylobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria) are common among a wide range of biomes, including burrowed sediments (Fang et al., 2023), epibionts of invertebrates in chemosynthetic habitats (Bai et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2022), and endosymbiotic communities in Idas mussels (Zvi-Kedem et al., 2023). The interactions between these organisms are not limited to the exchange of key metabolites (Zoccarato et al., 2022). One example of synergy in this system is the potential exchange of cobalamin (vitamin B12) among the community members. Our data suggest that the taxonomic diversity of cobalamin producers in the burrow walls is limited, primarily to Desulfobacterota and some thiotrophs (Thiomargarita MAG 115 and Thiohalomonadaceae MAG 43), as well as several others (Fig. 8). On the other hand, the common Flavobacteriaceae species (MAGs 10 and 69) do not produce cobalamin but may take it up, as they encode the outer-membrane vitamin B12 receptor BtuB and BtuFCD components of the vitamin B12 ABC transporter, providing this cofactor to B12-dependent enzymes such as methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (EC 5.4.99.2) and class-II ribonucleotide reductase (EC 1.17.4.1). The resilience of these communities may depend on redundancy in the production of such shared commodities, for example, cobalamin production by diverse Desulfobacterota genotypes.

3.7 Calliax lobata hosts specific gut microflora but may ingest burrow microbes

The amplicon sequencing of DNA extracted from the hindgut or midgut in several C. lobata specimens identified not only specialized microflora but also microbes found in the burrow walls (Figs. 7 and S2). The four key lineages associated with the gut sections included Entoplasmatales, Spirochaetales, Rickettsiales, and Rhodobacterales. For example, we found abundant Candidadus Hepatincola (Rickettsiales), a common nutrient-scavenging bacterium in the gut of crustaceans, in particular isopods, from terrestrial and aquatic environments (Dittmer et al., 2023). Some lineages that were prominent in burrow walls may occur in the C. lobata gut; for example, we found trace quantities of Desulfobulbus and Desulfocapsa in the gut of some C. lobata specimens (Fig. S2). Campylobacterota were abundant in the gut and the burrow walls, whereas Sulfurospirillum species were associated only with the gut, and Sulfurovum were found in both the burrows and the gut, indicating that these lineages occupy distinct niches. Altogether, these findings hint that C. lobata may be feeding in the burrows, providing evidence to support the “gardening” hypothesis.

Our results indicate that SEMS seep chemotones are characterized by extensive burrowing by ghost shrimp (C. lobata). The burrowed sediments can span tens to hundreds of meters away from the seepage hotspots, extending the seep area of influence by at least an order of magnitude. The high microbial activity in these burrowed sediments alters the biogeochemical cycles at the sediment–water interface of the oligotrophic SEMS (Sisma-Ventura et al., 2022), and our new results indicate that unique microbial communities at the burrow walls can contribute new functions needed to sustain this activity. These functions include the fermentation of complex macromolecules by Bacteroidota, coupling the oxidation of these fermentation products to sulfate reduction by Desulfobacterota and Nitrospirota and to chemotrophy by Campylobacterota and chemosynthetic Gammaproteobacteria, including the giant sulfur bacteria Thiomargarita. The enhancement of nitrogen cycling at seep chemotones may play a particularly important role in the oligotrophic SEMS. The discovery of these functions underscores the underestimated role of seep chemotones in deep-sea biogeochemistry.

The functionality of the burrow communities may depend on the gardening or grooming of burrow walls by C. lobata. Our observations indicate that this behavior is ubiquitous in ghost shrimp, altering benthic–pelagic nutrient exchange in both shallow and deep habitats (Laverock et al., 2010; Papaspyrou et al., 2005). While the burrow wall communities are most likely fueled by C. lobata secretions, producing an organic matter sink (“detrital trap”) in the burrow (Papaspyrou et al., 2005), it remains to be tested if C. lobata burrows can reach the sulfate–methane transition zone (e.g., the deeper sections of the sampled sediments, where ANME-1 species were found; Fig. 3), providing substrates for chemosynthesis. It is also intriguing to investigate the evolutionary aspects of crustacean associations with microbes in chemosynthetic habitats, given the similarity between the burrow and ectosymbiont communities (Bai et al., 2021; Cambon-Bonavita et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2022).

The raw metagenomic reads and metagenome-assembled genomes are available on NCBI as BioProject no. PRJNA1072319 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1072319/, last access: 10 March 2025).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-22-1321-2025-supplement.

MRB, YM, AF, OMB, and BH conceived this study and acquired funding. YM and OE performed mapping and led ROV and AUV work. AF and OMB performed CT scans. GSV and BH analyzed the chemical parameters. ER estimated microbial abundance and productivity. ZH and YY performed molecular work. MRB performed molecular and bioinformatics analyses. MRB wrote the paper with contributions from all co-authors.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

This research used samples and data provided by the E/V Nautilus Exploration Program, expedition NA019. The authors thank all of the individuals who helped during the expeditions, including onboard technical and scientific personnel of the E/V Nautilus, SEMSEEP 2016, and IOLR-University of Haifa cruises and the captains and crews of the E/V Nautilus, IOLR R/V Bat-Galim, and HCMR R/V AEGAEO. We are grateful to the University of Haifa Hatter Department of Marine Technologies team, Ben Herzberg and Samuel Cohen, who operated the Yona ROV. Furthermore, we wish to thank Moshe Tom and Hadas Lubinevsky (IOLR), for their assistance with sample collection, and Adi Neuman and Alexander Surdyaev (Applied Marine Exploration Lab, University of Haifa), for supporting data curation.

This study has been funded by the Israeli Science Foundation (ISF; grant nos. 913/19 and 1359/23), the Israel Ministry of Energy (grant nos. 221-17-002 and 221-17-004), the Horizon Europe REDRESS (Restoration of deep-sea habitats to rebuild European Seas; grant no. 101135492) project, the Israel Ministry of Science and Technology (grant no. 3-17403), and the Mediterranean Sea Research Center of Israel (MERCI). The EUROFLEETS2 SEMSEEP cruise was funded by the European Union FP7 program (grant no. 312762), and further analysis was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 200021_175587). This work was partly supported by the National Monitoring Program of Israel’s Mediterranean waters and the Charney School of Marine Sciences (CSMS), University of Haifa.

This paper was edited by Andrew Thurber and reviewed by Wang Minxiao and one anonymous referee.

Abed-Navandi, D., Koller, H., and Dworschak, P. C.: Nutritional ecology of thalassinidean shrimps constructing burrows with debris chambers: The distribution and use of macronutrients and micronutrients, Mar. Biol. Res., 1, 202–215, https://doi.org/10.1080/17451000510019123, 2005.

Aller, R. C.: Transport and reaction in the bioirrigated zone, in: The Benthic Boundary Layer: Transport Processes and Biogeochemistry, edited by: Boudreau, B. P. and Jorgensen, B. B., Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195118810.003.0011, 269–301, 2001.

Alves, J. I., Visser, M., Arantes, A. L., Nijsse, B., Plugge, C. M., Alves, M. M., Stams, A. J. M., and Sousa, D. Z.: Effect of sulfate on carbon monoxide conversion by a thermophilic syngas-fermenting culture dominated by a Desulfofundulus species, Front. Microbiol., 11, 588468, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.588468, 2020.

Amon, D. J., Gobin, J., Van Dover, C. L., Levin, L. A., Marsh, L., and Raineault, N. A.: Characterization of methane-seep communities in a deep-sea area designated for oil and natural gas exploitation off Ttrinidad and Tobago, Front. Mar. Sci., 4, 342, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00342, 2017.

Anantharaman, K., Hausmann, B., Jungbluth, S. P., Kantor, R. S., Lavy, A., Warren, L. A., Rappé, M. S., Pester, M., Loy, A., Thomas, B. C., and Banfield, J. F.: Expanded diversity of microbial groups that shape the dissimilatory sulfur cycle, ISME J., 12, 1715–1728, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0078-0, 2018.

Andersen, K. S., Kirkegaard, R. H., Karst, S. M., and Albertsen, M.: ampvis2: an R package to analyse and visualise 16S rRNA amplicon data, bioRxiv, 299537, https://doi.org/10.1101/299537, 2018.

Appel, J., Phunpruch, S., Steinmüller, K., and Schulz, R.: The bidirectional hydrogenase of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 works as an electron valve during photosynthesis, Arch. Microbiol., 173, 333–338, https://doi.org/10.1007/s002030000139, 2000.

Apprill, A., Mcnally, S., Parsons, R., and Weber, L.: Minor revision to V4 region SSU rRNA 806R gene primer greatly increases detection of SAR11 bacterioplankton, Aquat. Microb. Ecol., 75, 129–137, https://doi.org/10.3354/ame01753, 2015.

Ashford, O. S., Guan, S., Capone, D., Rigney, K., Rowley, K., Orphan, V., Mullin, S. W., Dawson, K. S., Cortés, J., Rouse, G. W., Mendoza, G. F., Lee, R. W., Cordes, E. E., and Levin, L. A.: A chemosynthetic ecotone – “chemotone” – in the sediments surrounding deep-sea methane seeps, Limnol. Oceanogr., 66, 1687–1702, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.11713, 2021.

Astall, C. M., Taylor, A. C., and Atkinson, R. J. A.: Behavioural and physiological implications of a burrow-dwelling lifestyle for two species of upogebiid mud-shrimp (Crustacea: Thalassinidea), Estuar. Coast. Shelf S., 44, 155–168, https://doi.org/10.1006/ecss.1996.0207, 1997.

Åström, E. K. L., Bluhm, B. A., and Rasmussen, T. L.: Chemosynthetic and photosynthetic trophic support from cold seeps in Arctic benthic communities, Front. Mar. Sci., 9, 1–19, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.910558, 2022.

Bai, S., Xu, H. and Peng, X.: Microbial communities of the hydrothermal scaly-foot snails from kairei and longqi vent fields, Front. Mar. Sci., 8, 764000, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.764000, 2021.

Barnum, T. P., Figueroa, I. A., Carlström, C. I., Lucas, L. N., Engelbrektson, A. L., and Coates, J. D.: Genome-resolved metagenomics identifies genetic mobility, metabolic interactions, and unexpected diversity in perchlorate-reducing communities, ISME J., 12, 1568–1581, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0081-5, 2018.

Basso, D., Beccari, V., Almogi-Labin, A., Hyams-Kaphzan, O., Weissman, A., Makovsky, Y., Rüggeberg, A., and Spezzaferri, S.: Macro- and micro-fauna from cold seeps in the Palmahim Disturbance (Israeli off-shore), with description of Waisiuconcha corsellii n.sp. (Bivalvia, Vesicomyidae), Deep.-Sea Res. Pt. II, 171, 104723, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2019.104723, 2020.

Bayon, G., Loncke, L., Dupré, S., Caprais, J.-C., Ducassou, E., Duperron, S., Etoubleau, J., Foucher, J.-P. J.-P., Fouquet, Y., Gontharet, S., Henderson, G. M., Huguen, C., Klaucke, I., Mascle, J., Migeon, S., Olu-Le Roy, K., Ondreas, H., Pierre, C., Sibuet, M., Stadnitskaia, A., and Woodside, J.: Multi-disciplinary investigation of fluid seepage on an unstable margin: The case of the Central Nile deep sea fan, Mar. Geol., 261, 92–104, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2008.10.008, 2009.

Beccari, V., Basso, D., Spezzaferri, S., Rüggeberg, A., Neuman, A., and Makovsky, Y.: Preliminary video-spatial analysis of cold seep bivalve beds at the base of the continental slope of Israel (Palmahim Disturbance), Deep.-Sea Res. Pt. II, 171, 104664, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2019.104664, 2020.

Blouet, J.-P., Imbert, P., Ho, S., Wetzel, A., and Foubert, A.: What makes seep carbonates ignore self-sealing and grow vertically: the role of burrowing decapod crustaceans, Solid Earth, 12, 2439–2466, https://doi.org/10.5194/se-12-2439-2021, 2021.

Boetius, A. and Wenzhöfer, F.: Seafloor oxygen consumption fuelled by methane from cold seeps, Nat. Geosci., 6, 725–734, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1926, 2013.

Bolyen, E., Rideout, J. R., Dillon, M. R., Bokulich, N. A., Abnet, C. C., Al-Ghalith, G. A., Alexander, H., Alm, E. J., Arumugam, M., Asnicar, F., Bai, Y., Bisanz, J. E., Bittinger, K., Brejnrod, A., Brislawn, C. J., Brown, C. T., Callahan, B. J., Caraballo-Rodríguez, A. M., Chase, J., Cope, E. K., Da Silva, R., Diener, C., Dorrestein, P. C., Douglas, G. M., Durall, D. M., Duvallet, C., Edwardson, C. F., Ernst, M., Estaki, M., Fouquier, J., Gauglitz, J. M., Gibbons, S. M., Gibson, D. L., Gonzalez, A., Gorlick, K., Guo, J., Hillmann, B., Holmes, S., Holste, H., Huttenhower, C., Huttley, G. A., Janssen, S., Jarmusch, A. K., Jiang, L., Kaehler, B. D., Kang, K. Bin, Keefe, C. R., Keim, P., Kelley, S. T., Knights, D., Koester, I., Kosciolek, T., Kreps, J., Langille, M. G. I., Lee, J., Ley, R., Liu, Y. X., Loftfield, E., Lozupone, C., Maher, M., Marotz, C., Martin, B. D., McDonald, D., McIver, L. J., Melnik, A. V., Metcalf, J. L., Morgan, S. C., Morton, J. T., Naimey, A. T., Navas-Molina, J. A., Nothias, L. F., Orchanian, S. B., Pearson, T., Peoples, S. L., Petras, D., Preuss, M. L., Pruesse, E., Rasmussen, L. B., Rivers, A., Robeson, M. S., Rosenthal, P., Segata, N., Shaffer, M., Shiffer, A., Sinha, R., Song, S. J., Spear, J. R., Swafford, A. D., Thompson, L. R., Torres, P. J., Trinh, P., Tripathi, A., Turnbaugh, P. J., Ul-Hasan, S., van der Hooft, J. J. J., Vargas, F., Vázquez-Baeza, Y., Vogtmann, E., von Hippel, M., Walters, W., Wan, Y., Wang, M., Warren, J., Weber, K. C., Williamson, C. H. D., Willis, A. D., Xu, Z. Z., Zaneveld, J. R., Zhang, Y., Zhu, Q., Knight, R., and Caporaso, G. J.: Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2, Nat. Biotechnol., 37, 852–857, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9, 2019.

Burgdorf, T., Lenz, O., Buhrke, T., Van Der Linden, E., Jones, A. K., Albracht, S. P. J., and Friedrich, B.: [NiFe]-hydrogenases of Ralstonia eutropha H16: Modular enzymes for oxygen-tolerant biological hydrogen oxidation, J. Mol. Microb. Biotech., 10, 181–196, https://doi.org/10.1159/000091564, 2006.

Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J., Rosen, M. J., Han, A. W., Johnson, A. J. A., and Holmes, S. P.: DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data, Nat. Methods, 13, 581–583, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3869, 2016.

Cambon-Bonavita, M.-A., Aubé, J., Cueff-Gauchard, V., and Reveillaud, J.: Niche partitioning in the Rimicaris exoculata holobiont: the case of the first symbiotic Zetaproteobacteria, Microbiome, 9, 87, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-021-01045-6, 2021.

Campbell, A., Gdanetz, K., Schmidt, A. W., and Schmidt, T. M.: H2 generated by fermentation in the human gut microbiome influences metabolism and competitive fitness of gut butyrate producers, Microbiome, 11, 133, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-023-01565-3, 2023.

Chaumeil, P. A., Mussig, A. J., Hugenholtz, P., and Parks, D. H.: GTDB-Tk: A toolkit to classify genomes with the genome taxonomy database, Bioinformatics, 36, 1925–1927, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz848, 2020.

Chen, Y.-J. J., Leung, P. M., Wood, J. L., Bay, S. K., Hugenholtz, P., Kessler, A. J., Shelley, G., Waite, D. W., Franks, A. E., Cook, P. L. M. M., and Greening, C.: Metabolic flexibility allows bacterial habitat generalists to become dominant in a frequently disturbed ecosystem, ISME J., 15, 2986–3004, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-021-00988-w, 2021.

Cheng, J., Li, H., Zhang, J., Ding, L., Ye, Q., and Lin, R.: Enhanced dark hydrogen fermentation of Enterobacter aerogenes/HoxEFUYH with carbon cloth, Int. J. Hydrogen Energ., 44, 3560–3568, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.12.080, 2019.

Chklovski, A., Parks, D. H., Woodcroft, B. J., Tyson, G. W., Chkolovski, A., Parks, D. H., Woodcroft, B. J., Tyson, G. W., Chklovski, A., Parks, D. H., Woodcroft, B. J., and Tyson, G. W.: CheckM2: a rapid, scalable and accurate tool for assessing microbial genome quality using machine learning, Nat. Methods, 20, 1203–1212, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-023-01940-w, 2023.

Coelho, V., Cooper, R., and de Almeida Rodrigues, S.: Burrow morphology and behavior of the mud shrimp Upogebia omissa (Decapoda:Thalassinidea:Upogebiidae), Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 200, 229–240, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps200229, 2000.

Coleman, D. and Ballard, R.: A highly concentrated region of cold hydrocarbon seeps in the southeastern Mediterranean Sea, Geo-Mar. Lett., 21, 162–167, https://doi.org/10.1007/s003670100079, 2001.

Coleman, D. F., Austin Jr., J. A., Ben-Avraham, Z., Makovsky, Y., and Tchernov, D.: Seafloor pockmarks, deepwater corals, and cold seeps along the continental margin of Israel, Oceanography, 25, 40–41, 2012.

Coleman, D. F. D., Austin Jr., J. A., Ben-Avraham, Z., Ballard, R. D., Austin, J. A., Ben-Avraham, Z., and Ballard, R. D.: Exploring the continental margin of Israel: “Telepresence” at work, EOS T. Am. Geophys. Un., 92, 81–82, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011EO100002, 2011.

Dittmer, J., Bredon, M., Moumen, B., Raimond, M., Grève, P., and Bouchon, D.: The terrestrial isopod symbiont `Candidatus Hepatincola porcellionum' is a potential nutrient scavenger related to Holosporales symbionts of protists, ISME Commun., 3, 18, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43705-023-00224-w, 2023.

Drake, H. L.: Acetogenesis, Acetogenic Bacteria, and the Acetyl-CoA “Wood/Ljungdahl” Pathway: Past and Current Perspectives, in: Acetogenesis, edited by: Drake, H. L., Springer US, Boston, MA, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-1777-1_1, 3–60, 1994.

Dworschak, P. C., Koller, H., and Abed-Navandi, D.: Burrow structure, burrowing and feeding behaviour of Corallianassa longiventris and Pestarella tyrrhena (Crustacea, Thalassinidea, Callianassidae), Mar. Biol., 148, 1369–1382, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-005-0161-8, 2006.

Fang, J., Jiang, W., Meng, S., He, W., Wang, G., Guo, E., and Yan, Y.: Polychaete bioturbation alters the taxonomic structure, co-occurrence network, and functional groups of bacterial communities in the intertidal flat, Microb. Ecol., 86, 112–126, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-022-02036-2, 2023.

Fang, Y., Liu, J., Yang, J., Wu, G., Hua, Z., Dong, H., Hedlund, B. P., Baker, B. J., and Jiang, H.: Compositional and metabolic responses of autotrophic microbial community to salinity in lacustrine environments, edited by: Mackelprang, R., mSystems, 7, e0033522, https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00335-22, 2022.

Fernández-Gómez, B., Richter, M., Schüler, M., Pinhassi, J., Acinas, S. G., González, J. M., and Pedrós-Alió, C.: Ecology of marine bacteroidetes: A comparative genomics approach, ISME J., 7, 1026–1037, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2012.169, 2013.

Finster, K.: Microbiological disproportionation of inorganic sulfur compounds, J. Sulfur Chem., 29, 281–292, https://doi.org/10.1080/17415990802105770, 2008.

Finster, K. W., Kjeldsen, K. U., Kube, M., Reinhardt, R., Mussmann, M., Amann, R., and Schreiber, L.: Complete genome sequence of desulfocapsa sulfexigens, a marine deltaproteobacterium specialized in disproportionating inorganic sulfur compounds, Stand. Genomic Sci., 8, 58–68, https://doi.org/10.4056/sigs.3777412, 2013.

Flood, B. E., Fliss, P., Jones, D. S., Dick, G. J., Jain, S., Kaster, A.-K., Winkel, M., Mußmann, M., and Bailey, J.: Single-cell (meta-)genomics of a dimorphic Candidatus Thiomargarita nelsonii reveals genomic plasticity, Front. Microbiol., 7, 603, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00603, 2016.

Frank, H., Rahav, E., and Bar-Zeev, E.: Short-term effects of SWRO desalination brine on benthic heterotrophic microbial communities, Desalination, 417, 52–59, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2017.04.031, 2017.

Gadol, O., Tibor, G., ten Brink, U., Hall, J. K., Groves-Gidney, G., Bar-Am, G., Hübscher, C., and Makovsky, Y.: Semi-automated bathymetric spectral decomposition delineates the impact of mass wasting on the morphological evolution of the continental slope, offshore Israel, Basin Res., 32, 1166–1193, https://doi.org/10.1111/bre.12420, 2020.

Garfunkel, Z., Arad, A., and Almagor, G.: The Palmahim disturbance and its regional setting, Geol. Surv. Isr. Bull., 56, 1979.

Gavriilidou, A., Gutleben, J., Versluis, D., Forgiarini, F., Van Passel, M. W. J., Ingham, C. J., Smidt, H., and Sipkema, D.: Comparative genomic analysis of Flavobacteriaceae: Insights into carbohydrate metabolism, gliding motility and secondary metabolite biosynthesis, BMC Genomics, 21, 569, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-06971-7, 2020.

Gibson, G. R., Macfarlane, G. T., and Cummings, J. H.: Sulphate reducing bacteria and hydrogen metabolism in the human large intestine, Gut, 34, 437–439, https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.34.4.437, 1993.

Gilbertson, W. W., Solan, M., and Prosser, J. I.: Differential effects of microorganism-invertebrate interactions on benthic nitrogen cycling, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 82, 11–22, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01400.x, 2012.

Glöckner, F. O., Yilmaz, P., Quast, C., Gerken, J., Beccati, A., Ciuprina, A., Bruns, G., Yarza, P., Peplies, J., Westram, R., and Ludwig, W.: 25 years of serving the community with ribosomal RNA gene reference databases and tools, J. Biotechnol., 261, 169–176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.06.1198, 2017.

Glud, R. N., Thamdrup, B., Stahl, H., Wenzhoefer, F., Glud, A., Nomaki, H., Oguri, K., Revsbech, N. P., and Kitazatoe, H.: Nitrogen cycling in a deep ocean margin sediment (Sagami Bay, Japan), Limnol. Oceanogr., 54, 723–734, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2009.54.3.0723, 2009.

Grondin, J. M., Tamura, K., Déjean, G., Abbott, D. W., and Brumer, H.: Polysaccharide utilization loci: Fueling microbial communities, J. Bacteriol., 199, https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00860-16, 2017.

Gutekunst, K., Chen, X., Schreiber, K., Kaspar, U., Makam, S., and Appel, J.: The bidirectional NiFe-hydrogenase in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 Is reduced by flavodoxin and ferredoxin and is essential under mixotrophic, nitrate-limiting conditions, J. Biol. Chem., 289, 1930–1937, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.526376, 2014.

Gvirtzman, Z., Reshef, M., Buch-Leviatan, O., Groves-Gidney, G., Karcz, Z., Makovsky, Y., and Ben-Avraham, Z.: Bathymetry of the Levant basin: interaction of salt-tectonics and surficial mass movements, Mar. Geol., 360, 25–39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2014.12.001, 2015.

Hembree, D. I.: Burrows and ichnofabric produced by centipedes: modern and ancient examples, Palaios, 34, 468–489, https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2019.059, 2019.

Herut, B., Rubin-Blum, M., Sisma-Ventura, G., Jacobson, Y., Bialik, O. M., Ozer, T., Lawal, M. A., Giladi, A., Kanari, M., Antler, G., and Makovsky, Y.: Discovery and chemical composition of the eastmost deep-sea anoxic brine pools in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea, Front. Mar. Sci., 9, 1040681, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.1040681, 2022.

Hui, M., Wang, A., Cheng, J., and Sha, Z.: Full-length 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing reveals the variation of epibiotic microbiota associated with two shrimp species of Alvinocarididae: possibly co-determined by environmental heterogeneity and specific recognition of hosts, PeerJ, 10, e13758, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13758, 2022.

Ionescu, D. and Bizic, M.: Giant Bacteria, in: Encyclopedia of Life Sciences, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470015902.a0020371.pub2, 2019.

Joye, S. B.: The geology and biogeochemistry of hydrocarbon seeps, Annu. Rev. Earth Pl. Sc., 48, 205–231, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-063016-020052, 2020.

Jumars, P. A., Dorgan, K. M., Mayer, L. M., Boudreau, B. P., and Johnson, B. D.: Material constraints on infaunal lifestyles. May the persistent and strong forces be with you, in: Trace Fossils. Concepts, Problems, Prospects, Elsevier Science, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-044452949-7/50152-2, 442–457, 2007.

Kang, D. D., Froula, J., Egan, R., and Wang, Z.: MetaBAT, an efficient tool for accurately reconstructing single genomes from complex microbial communities, PeerJ, 3, e1165, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1165, 2015.

Kieser, S., Brown, J., Zdobnov, E. M., Trajkovski, M., and McCue, L. A.: ATLAS: a Snakemake workflow for assembly, annotation, and genomic binning of metagenome sequence data, BMC Bioinformatics, 21, 257, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-020-03585-4, 2020.

Knaust, D.: Siphonichnidae (new ichnofamily) attributed to the burrowing activity of bivalves: Ichnotaxonomy, behaviour and palaeoenvironmental implications, Earth-Sci. Rev., 150, 497–519, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.07.014, 2015.

Knittel, K. and Boetius, A.: Anaerobic oxidation of methane: progress with an unknown process, Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 63, 311–34, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093130, 2009.

Kormas, K. A. and Meziti, A.: The microbial communities of the East Mediterranean Sea mud volcanoes and pockmarks, in: Marine Hydrocarbon Seeps: Microbiology and Biogeochemistry of a Global Marine Habitat, edited by: Teske, A. P. and Carvalho, V., Springer Nature Switzerland, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34827-4_7, 143–148, 2020.

Kristensen, E. and Kostka, J. E.: Macrofaunal burrows and irrigation in marine sediment: Microbiological and biogeochemical interactions, in: Interactions Between Macro- and Microorganisms in Marine Sediments, edited by: Kristensen, E., Haese, R. R., and Kostka, J. E., AGU, Washington, DC, US, https://doi.org/10.1029/60CE08, 125–157, 2005.

Laverock, B., Smith, C. J., Tait, K., Osborn, A. M., Widdicombe, S., and Gilbert, J. A.: Bioturbating shrimp alter the structure and diversity of bacterial communities in coastal marine sediments, ISME J., 4, 1531–1544, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2010.86, 2010.

Lawal, M. A., Bialik, O. M., Lazar, M., Waldmann, N. D., Foubert, A., and Makovsky, Y.: Modes of gas migration and seepage on the salt-rooted Palmahim Disturbance, southeastern Mediterranean, Mar. Petrol. Geol., 153, 106256, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2023.106256, 2023.

Levin, L. A. and Sibuet, M.: Understanding continental margin biodiversity: A new imperative, Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci., 4, 79–112, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142714, 2012.

Levin, L. A., Baco, A. R., Bowden, D. A., Colaco, A., Cordes, E. E., Cunha, M. R., Demopoulos, A. W. J., Gobin, J., Grupe, B. M., Le, J., Metaxas, A., Netburn, A. N., Rouse, G. W., Thurber, A. R., Tunnicliffe, V., Van Dover, C. L., Vanreusel, A., and Watling, L.: Hydrothermal vents and methane seeps: rethinking the sphere of influence, Front. Mar. Sci., 3, 72, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2016.00072, 2016.

Makovsky, Y., Rüggeberg, A., Bialik, O., Foubert, A., Almogi-Labin, A., Alter, Y., Bampas, V., Basso, D., Feenstra, E., and Fentimen, R.: South East Mediterranean SEEP Carbonate, R/V Aegaeo Cruise, EuroFLEETS2 SEMSEEP, R/V Aegaeo Cruise EuroFLEETS2 SEMSEEP, https://drive.google.com/file/d/16WKBpPIibT8eqYcDlc2SHhkBKntcT2CT/view?usp=sharing (last access: 6 March 2025), 2017.

Martens, E. C., Chiang, H. C., and Gordon, J. I.: Mucosal glycan foraging enhances fitness and transmission of a saccharolytic human gut bacterial symbiont, Cell Host Microbe, 4, 447–457, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.007, 2008.

Martens, E. C., Koropatkin, N. M., Smith, T. J., and Gordon, J. I.: Complex glycan catabolism by the human gut microbiota: The bacteroidetes sus-like paradigm, J. Biol. Chem., 284, 24673–24677, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.R109.022848, 2009.