the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Shifts in organic matter character and microbial assemblages from glacial headwaters to downstream reaches in the Canadian Rocky Mountains

Hayley F. Drapeau

Maria A. Cavaco

Jessica A. Serbu

Vincent L. St. Louis

Maya P. Bhatia

Climate change is causing mountain glacial systems to warm rapidly, leading to increased water fluxes and concomitant export of glacially derived sediment and organic matter (OM). Glacial OM represents an aged but potentially bioavailable carbon pool that is compositionally distinct from OM found in non-glacially sourced waters. Despite this, the composition of riverine OM from glacial headwaters to downstream reaches and its possible role in structuring microbial assemblages have rarely been characterized in the Canadian Rockies. Over three summers (2019–2021), we collected samples before, during, and after glacial ice melt along stream transects ranging from 0 to 100 km downstream of glacial termini on the eastern slopes of the Canadian Rocky Mountains. We quantified dissolved and particulate organic carbon (DOC, POC) concentrations and used isotopes (Δ14C–OC, δ13C–OC) and dissolved OM (DOM) absorbance and fluorescence to assess OM age, source, and character. Environmental data were combined with microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing to assess controls on the composition of stream water microbial assemblages. From glacial headwaters to downstream reaches, OM showed a clear transition from being aged and protein-like, with an apparent microbial source, to being relatively younger and humic-like. Indicator microbial species for headwater sites included chemolithoautotrophs and taxa known to harbour adaptations to cold temperatures and nutrient-poor conditions, suggesting some role of glacial seeding of microbial taxa to the headwaters of this connected riverine gradient. However, physical and chemical conditions (including water temperature; POC concentration; protein-like DOM; and deuterium excess, an indicator of water source) could only significantly explain ∼ 9 % of the observed variation in microbial assemblage structure. This finding, paired with the identification of a ubiquitous core microbial assemblage that comprised a small proportion of all identified amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) but was present in large relative abundance at all sites, suggests that mass effects (i.e., whereby high dispersal rates cause homogenization of adjacent communities) largely overcome species sorting to enable a connected microbial assemblage along this strong environmental gradient. Our findings suggest that a loss of novel glacial and microbial inputs with climate change, coupled with catchment terrestrialization, could change OM cycling and microbial assemblage structure across the evolving mountain-to-downstream continuum in glacierized systems.

- Article

(5508 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2892 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

We tragically lost Maya P. Bhatia while this manuscript was under review. Without her vision, this work would never have been accomplished.

Anthropogenic climate change is causing glaciers to retreat at unprecedented rates (Zemp et al., 2015). Rapid glacial retreat has the potential to impact downstream hydrology (Clarke et al., 2015), carbon cycling (Hood et al., 2015, 2020), and microbial assemblage dynamics (Bourquin et al., 2022; Hotaling et al., 2017) as source water contributions to headwater streams undergo fundamental change. In the Canadian Rocky Mountains, glacial meltwater contributions to downstream rivers are presently increasing but are projected to peak by 2040 (Clarke et al., 2015; Pradhananga and Pomeroy, 2022). Over the coming decades, the eventual disappearance of glacial meltwater additions to glacially fed rivers is predicted to lead to decreased summer flows and water availability, impacting millions of individuals in communities downstream (Anderson and Radić, 2020).

Changing contributions of glacial meltwater to headwater streams could disrupt downstream riverine carbon dynamics because glaciers provide and internally cycle unique sources of organic carbon (OC) (Hood et al., 2015; Musilova et al., 2017; Wadham et al., 2019). As glaciers melt, the formation of supraglacial and subglacial channels can cause meltwater to be routed on top of, through, and/or underneath, glaciers (Nienow et al., 1998). At the beginning of the melt season, water is typically sourced from snowmelt which is inefficiently routed through a distributed hydrological network at the ice–bed interface or along the ice margin and is characterized by high rock–water contact times (Arendt et al., 2016). As the melt season progresses, an efficient subglacial network forms, facilitating rapid transit through the subglacial environment (Arendt et al., 2016) or routing of water laterally via marginal streams. This meltwater is then exported into headwater streams, where it provides an important seasonal control on stream hydrology via augmentation of summer discharge (Campbell et al., 1995) and biogeochemistry via its unique chemical signature (Milner et al., 2017). The contribution of glacially sourced water to headwater streams enables the movement of novel organic matter (OM) from overridden vegetation at the glacier bed (Bhatia et al., 2010), anthropogenic aerosols on the ice surface (Stubbins et al., 2012), and in situ microbial assemblages (Stibal et al., 2012) to downstream systems. Previous studies have shown that glacially derived dissolved OM (DOM) is aged (Bhatia et al., 2013; Hood et al., 2009; Stubbins et al., 2012), exhibits protein-like fluorescence (Dubnick et al., 2009; Kellerman et al., 2020), and can serve as a labile substrate for downstream microorganisms (Hood et al., 2009; Singer et al., 2012). In contrast, glacially derived particulate OM (POM) and its OC subset POC, which have been less studied, can be predominantly derived from comminuted rock and sediment and can persist within rivers (Cui et al., 2016; Hood et al., 2020). During transit through fluvial networks, glacially exported OM mixes with non-glacial terrestrially derived OM, which typically exhibits a humic-like fluorescent signature (McKnight et al., 2001a), is relatively younger (Raymond and Bauer, 2001), and has generally been shown to be less accessible for microbial consumption (D'Andrilli et al., 2015).

River ecosystems are overwhelmingly heterotrophic, with food webs sustained by microbial consumption and mineralization of OM inputs (Bernhardt et al., 2022). OM composition has been found to be an important determinant of microbial assemblage structure (Judd et al., 2006), alongside environmental factors such as light, river flow regimes (Bernhardt et al., 2022; Milner et al., 2017), temperature, and nutrient availability (Elser et al., 2020). Thus, the increase and eventual decline in glacial meltwater inputs into fluvial networks, with their entrained glacial OM, may impact microbial assemblages. In addition, headwater assemblages can shift as a result of the direct loss of novel glacially sourced microbes (Wilhelm et al., 2013) as glaciers have been found to host unique microbial taxa in both the supraglacial and subglacial environments (Bourquin et al., 2022; Hotaling et al., 2017; Stibal et al., 2012). These taxa are often uniquely adapted to glacial conditions, such as seasonally fluctuating and overall low nutrient concentrations; cold temperatures; and the presence of reduced chemical species in low-oxygen subglacial environments, which can select for chemosynthetic metabolisms (Bourquin et al., 2022; Hotaling et al., 2017). Recent work at European, Greenlandic, and North American glaciers indicates that microbes from supraglacial environments are readily entrained in meltwaters, enabling these flow paths to seed downstream microbial assemblages (Stevens et al., 2022). Overall, if changes in glacial loss drive changes in microbial assemblage composition, this could lead to a loss of unique metabolic pathways (Bourquin et al., 2022), changes in respiratory effluxes of CO2 (e.g., Singer et al., 2012), and food web perturbations, given that OM incorporated into microbial biomass is assimilated by higher-trophic-level organisms (e.g., Fellman et al., 2015).

In this study, we pair measurements of stream OM and microbial assemblage composition along transects from glacial headwaters to downstream reaches, with sampling across 3 years and encompassing conditions prior to, during, and after the summer glacial melt season. We undertake this work in glacially fed fluvial networks draining eastward from the Canadian Rocky Mountains to assess how glacial loss will impact downstream microbial diversity and carbon cycling in this region. The icefields (Wapta and Columbia) that feed these alpine glaciers are rapidly shrinking and are projected to be reduced by 80 %–100 % of their 2005 area by 2100 (Clarke et al., 2015). Our objectives in this rapidly changing landscape were three-fold: first, to investigate spatial and temporal variation in stream OM age, source, and character across different hydrological periods in three Rocky Mountain rivers, with a distance ranging from 0 to 100 km downstream of glacial termini; second, to characterize microbial assemblage composition and its variation along this same gradient; and, finally, to identify environmental drivers of variation in microbial assemblage structure, with a particular focus on OM composition. We hypothesized that (1) OM character, apparent source, and age would transition along our 100 km transects; (2) microbial assemblages would vary similarly along our transects; and (3) these shifts would be tied, such that changes in OM and other chemical parameters would structure microbial assemblages from headwaters to downstream reaches.

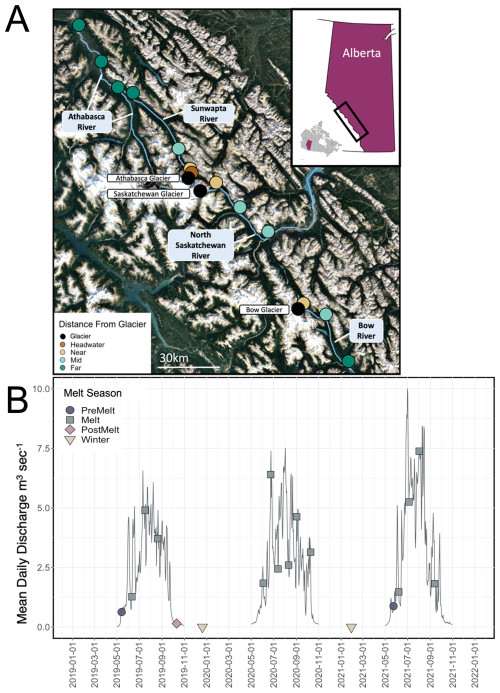

Figure 1(a) Sampling locations of study sites on the Bow, North Saskatchewan, Sunwapta, and Athabasca rivers, in Alberta, Canada (© Google Earth 2022). Locations are coloured by distance range, binned as headwater (0.2 km downstream), near (3–6 km downstream), middle (16–50 km downstream), and far (>50 km downstream). The inset map shows the location of the sampling region (black box) within Alberta. (b) Hydrograph of open-water discharge measured at the gauging station 3 km downstream of Athabasca glacier (station no. 07AA007, maintained by Environment and Climate Change Canada) from 2019 to 2021; note that data were not collected during November–May. The location of the hydrologic station corresponds to the Sunwapta “near” site. Sample collection dates are demarcated, with the corresponding melt season indicated.

2.1 Site description

Samples were collected from the Sunwapta–Athabasca, North Saskatchewan (NSR), and Bow rivers located within Banff National Park and Jasper National Park of the Canadian Rocky Mountains (Fig. 1). Each of these rivers are sourced from glacial headwaters, with the Sunwapta–Athabasca and NSR receiving inputs predominately from the Columbia Icefield and the Bow River receiving inputs from the Wapta Icefield. At ∼ 216 km2 (Tennant and Menounos, 2013; Bolch et al., 2010), the Columbia Icefield is the largest icefield in the Canadian Rockies, while the Wapta Icefield is smaller at ∼ 80 km2 (Ommanney, 2002).

Along each river, we chose three to four sampling sites at which we examined how stream OM and microbial characteristics transitioned with increasing distance from glacial input. Sampling sites ranged from glacial headwaters (0 km downstream of glacial inflow) to 100 km downstream of glacial termini. For certain statistical analyses (predominantly those associated with microbial assemblage structure), sites were binned into four distance ranges based on the variation in the upstream catchment between sites: headwater (0.2 km downstream), near (2–6 km downstream), middle (18–50 km downstream), and far (>50 km downstream) (Fig. 1a). These bins were selected a priori to enable a gradient of sites (Table S1 in the Supplement). For example, the headwater site had no catchment forest cover, near sites ranged from 0.3 % to 5 % forest and from 42 % to 55 % snow and ice, and far sites had greater than 25 % forest and 6 %–12 % snow and ice (Table S1). Sites were restricted to locations within Banff National Park and Jasper National Park to enable a comparison of study sites that were minimally impacted by direct anthropogenic landscape disturbances. Throughout, we generally use the term “stream” to refer to specific sites, although we acknowledge that our transects span from glacial headwaters to relatively large riverine reaches.

Samples were collected over a 3-year study period (Fig. 1b). Each of the sample sites were visited every 3 to 4 weeks throughout the months of May to October during 2019, 2020, and 2021. Opportunistic samples were also collected at a subset of sites in December 2019 and January 2021. This sampling design enabled us to cover the three main hydrological stages in a glacially sourced river: prior to the seasonal glacial ice melt (pre-melt; n=2 visits, 24 samples total), during the glacial melt period (melt; n=13 visits, 177 samples), during the post-glacial ice melt period (post-melt; n=1 visit; 14 samples), and during winter (n=2 visits; 7 samples). Hydrological periods were determined using the Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) stream discharge hydrographs from Athabasca Glacier (station ID no. 07AA007) (Fig. 1b). We defined the pre-melt stage as the period when monthly average stream discharge at the Athabasca glacier headwater was low (<1 m3 s−1; assessed as the inflection point on the Athabasca Glacier hydrograph), a likely indication that glacial meltwater channels were not yet established (Arendt, 2015). The glacial melt period was defined as the period when monthly average discharge was high (>1 but rapidly transitioning to >2.5 m3 s−1; discharge typically peaked during July–August); at this time, glacial meltwater channels were likely well established, with melting glacier ice contributing substantially to headwater stream flow. Finally, the post-melt period was characterized by, once again, low average monthly discharge at the glacier headwater (<1 m3 s−1; typically from October and onwards), likely indicating closed glacial channels and cessation of ice melt input. In 2019, all three hydrological stages (pre-melt, melt, post-melt) were sampled; in 2020, sampling was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and samples were only collected during the melt and post-melt stages; in 2021, samples were collected during the pre-melt and melt stages only. Over our 3-year study period, 2019 exhibited the lowest melt-period discharge, and 2021 exhibited the highest melt-period discharge (Fig. 1b).

2.2 Field sampling and field laboratory processing

At each site, samples were collected for DOM absorbance and fluorescence, DOC concentration, POC concentration, particulate and dissolved OC isotopes (δ13C–DOC, δ13C–POC, Δ14C–DOC, Δ14C–POC), and 16S rRNA gene sequencing. To further assess water source and hydrochemical controls on microbial diversity in our analyses, we used data for water isotopes (δ18O–H2O, δ2H–H2O), nutrients (ammonia (NH), nitrate and nitrite (NONO), total dissolved nitrogen (TDN), total nitrogen (TN), soluble reactive phosphorous (SRP), total dissolved phosphorus (TDP), total phosphorous (TP), dissolved silica (SiO2)), major anions and cations (Mg2+, Cl−, Na2+, SO, Ca2+, K+), trace metals (Al3+, Ba2+, dCr, dMn, dMo, dNi, Sr2+), temperature, and specific conductance; these data were collected on each trip (see also Serbu et al., 2024). All sample bottles, except those for anions and nutrients, were soaked overnight in a dilute acid bath (1.2 mol L−1 trace-metal-grade HCl), rinsed at least three times with 18.2 MΩ Milli-Q water, and rinsed three times with sample water before collection at the field site. Bottles for anion and nutrient analyses were new, following the tested protocol in the CALA (Canadian Association for Laboratory Accreditation)-certified laboratory where these analyses were run (University of Alberta Biogeochemical Analytical Services Laboratory; BASL). Trace metal bottles were pre-soaked in a 0.01 % Citranox (phosphate-free detergent) bath prior to the acid bath step. Following the HCl soak and Milli-Q water rinse, all glassware (bottles, EPA vials, and filtration apparatus) were combusted at 560 °C for a minimum of 4 h, and high-density polycarbonate (HDPC) bottles for microbial analysis were autoclaved. Glass microfiber filters (grade GF/F, Whatman) were combusted at 460 °C for a minimum of 4 h prior to use. High-density polyethylene (HDPE) bottles for ion collection were pre-washed with Citranox prior to the acid-cleaning procedure.

Samples for DOM absorbance and fluorescence, DOC concentration, and δ13C–DOC were sub-sampled from a 250 mL amber glass collection bottle and filtered stream-side through 0.45 µm polyethersulfone (PES) filters (Fisherbrand Basix; pre-rinsed with 60 mL Milli-Q and 15 mL river water) into combusted 40 mL amber EPA vials. Nutrient samples were sub-sampled from a 500 mL HDPE collection bottle and filtered stream-side, using a pre-rinsed sterile plastic syringe and a pre-rinsed 0.45 µm cellulose acetate filter (Sartorius), into polypropylene collection bottles. Water isotope samples were filtered stream-side, using either 0.45 µm cellulose acetate (in 2019, 2020) or PES (in 2021) filters, into 2 mL glass (2019, 2020) or 25 mL HDPE scintillation (2021) vials filled with no headspace. Major ions and trace metals were sub-sampled from a 250 mL HDPE collection bottle and were filtered stream-side into 20 mL scintillation vials using rubber-free syringes and a 0.45 µm PES filter. Water temperature and specific conductance were measured on site using a YSI EXO sonde. Bulk water samples were collected for microbial assemblage analyses in prepared (see above) HDPC bottles, radiocarbon (Δ14C–DOC, Δ14C–POC) samples were collected in Teflon bottles, and POC concentration and δ13C–POC samples were collected in 4L HDPE plastic bottles. All bulk water chemistry samples (for Δ14C–DOC, POC concentration, Δ14C–POC, and δ13C–POC) were filtered within 24 h of collection off site. Samples for 16S rRNA gene sequencing were generally filtered within 4–12 h of collection, apart from the Bow River samples, which were filtered after 24 h following collection. To minimize the effects of differential processing times on the assessment of microbial assemblage dynamics, Bow River samples were excluded from our microbial analysis but were retained in the hydrochemical and carbon analyses.

Bulk water samples of 2 L collected for 16S rRNA gene sequencing were filtered “until refusal” using a 0.22 µm Sterivex (Millipore Sigma) filter and a peristaltic pump operated at 50–60 mL min−1 to minimize cell breakage. A field blank, consisting of a clean 2 L polycarbonate bottle filled with Milli-Q water, left open at each site, was also processed in the same way to control for any outside contamination during processing. Dissolved radiocarbon samples were filtered through a 0.7 µm GF/F filter using a glass filter tower, collected into 1 L amber glass bottles, and acidified to pH 2 using HPLC-grade H3PO4. Material retained on the 0.7 µm GF/F filter was used for Δ14C–POC analysis. Samples for POC concentration and δ13C–POC were collected on 0.7 µm GF/F filters using plastic filter towers. Samples for DOC concentration and δ13C–DOC were acidified to pH 2 using trace-metal-grade HCl. Cation and trace metal samples were acidified to pH 2 using trace-metal-grade HNO3. Samples for DOC concentration, δ13C–DOC, Δ14C–DOC, DOM absorbance and fluorescence, anions, TDN, TDP, and dSi were stored at 4 °C. Samples for NH, NONO, δ13C–POC, and Δ14C–POC were stored at −20 °C. Sterivex filters were flash-frozen in a liquid nitrogen dry shipper and, upon return to the laboratory, were stored at −80 °C until analysis.

2.3 Laboratory analyses

2.3.1 DOM absorbance and fluorescence, DOC, POC, and OC isotopes

DOM absorbance and fluorescence were analyzed using a HORIBA Scientific Aqualog with a 1 cm path length quartz cuvette. Absorbance scans were collected over a 240–800 nm wavelength range in 1 nm increments with a 0.5 s integration time. Excitation emission matrices (EEMs) were constructed over a 230–500 nm excitation wavelength range in increments of 5 nm and at a 5 s integration time, with an emission coverage increment of 2.33 nm and a 230–500 nm emission wavelength range.

DOC samples were analyzed using a Shimadzu total organic carbon analyzer. Samples estimated (from absorbance) to have less than 1 mg L−1 DOC were analyzed on a Shimadzu TOC-V equipped with a high-sensitivity catalyst using a 2 mL injection and 5 min sparge time. Samples estimated to have more than 1 mg L−1 DOC were analyzed using a Shimadzu TOC-L fitted with a regular-sensitivity catalyst using a 150 µL injection and 5 min sparge time. For analyses on the TOC-V, a five-point (0–1 mg L−1) or six-point (0–0.5 mg L−1) calibration curve (R2>0.98) was created daily using dilution from a 5 mg L−1 stock solution (SCP Science). For analyses on the TOC-L, a five-point (0–1 or 0–2 mg L−1) calibration curve (R2>0.98) was created through dilution of either 5 mg L−1 or 10 mg L−1 stock solution (SCP Science). Reference waters were created using dilution of a 5 mg L−1 stock solution (SCP Science) or from a 1 mg C L−1 caffeine solution. Reference waters and Milli-Q blanks were run every 10 samples and were within 10 % of the accepted values. Samples were blank corrected via the subtraction of mean blank concentrations of Milli-Q samples run prior to the 10 sample groups to account for instrument drift.

POC, δ13C–POC, and Δ14C–POC samples were subjected to a heated acid fumigation following procedures outlined in Whiteside et al. (2011). Briefly, this involved heating the filters at 60 °C for 24 h in a desiccator with 20 mL of concentrated trace-metal-grade HCl and then neutralizing the filters at room temperature for 24 h in a desiccator with NaOH pellets. Samples for POC concentration and δ13C–POC were packaged into tin capsules before being measured using an Elementar vario EL cube elemental analyzer and a DELTA V Plus Advantage isotope ratio mass spectrometer with a ConFlo III interface (δ13C–POC only) at the Environmental Isotope Laboratory at the University of Waterloo (in 2019) or the Jan Veizer Stable Isotope Laboratory (Ottawa, ON, Canada, in 2020 and 2021). δ13C–DOC samples were analyzed using the wet oxidation method on an OI Analytical Aurora 1030W TOC Analyzer connected to an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) at the Jan Veizer Stable Isotope Laboratory. Δ14C–POC samples were processed via organic combustion and Δ14C–DOC samples were processed using UV oxidation prior to graphitization and accelerator mass spectrometry analysis at the André E. Lalonde AMS Laboratory at the University of Ottawa (in 2019) or the National Ocean Sciences Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Facility (NOSAMS; WHOI, Woods Hole, MA, USA, in 2020 and 2021; batch nos. 67 580, 67 380, 67 069, and 66 828).

2.3.2 Hydrochemical samples

Nutrient (NH, NONO, TDN, TDP, TN, TP, dSi, SRP), trace metal (Al3+, Ba2+, dCr, dMn, dMo, dNi, Sr2+), and ion (Mg2+, Cl−, Na2+, SO, Ca2+, K+) samples were analyzed at the CALA-accredited BASL facility at the University of Alberta (Edmonton, AB, Canada) (see Table S2 for detection limits and method details). Nutrient samples were analyzed using flow injection analysis on a Lachat Quikchem 8500 FIA automated ion analyzer, and anions were analyzed via ion chromatography on a Dionex DX600. Cations and trace metals were analyzed using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry on a Thermo Scientific iCAP Q (2019) and Agilent 7900 (2020–2021). Water isotopes (δ18O–H2O and δ2H–H2O) were analyzed using a Picarro L2130 isotope and gas concentration analyzer calibrated using standard references obtained from ice core water (USGS46) and Lake Louise drinking water (USGS47) (United States Geological Survey). Reference waters and Milli-Q were run every 20 samples and were within 20 % of the accepted values. Sample values were calculated from an average of three injections where the standard deviation of δ18O–H2O was less than 0.2 and the standard deviation for δ2H–H2O was less than 1; the first five injections were typically excluded due to memory effects. δ18O–H2O and δ2H–H2O were used to calculate deuterium excess, which we use as an indicator of water source, given its known increase with elevation, and therefore of water sourced from glaciers and high-elevation snow (Bershaw and Lechler, 2019; Bershaw et al., 2020; Boral et al., 2019).

2.3.3 Lab and bio-informatic processing of microbial samples

Bulk genomic DNA collected on the Sterivex filter was extracted using a DNeasy PowerWater Sterivex Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, with an amendment of a 1 h at 72 °C for the initial incubation time rather than 90 °C for 5 min to increase DNA yield. Measured genomic DNA extracted from filters ranged from below detection (<0.5 ng µL−1) to 20.8 ng µL−1; when DNA concentrations were quantified to be below 10 ng µL−1 on the Qubit following DNA extraction, we added 5 µL of template DNA (default is 2.5 µL), along with bovine serum albumin (BSA), to maximize DNA available for PCR (polymerase chain reaction), adjusting for total water added to the reaction.

Extracted samples, including field blank samples and a separate negative control containing PCR-grade water as a template, were amplified using the 515F (5'GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA'3) and 926R (5'CCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT'3) primers (Parada et al., 2016), targeting the V4–V5 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene with the following protocol: 3 min initial denaturation at 98 °C; 35 cycles of 30 s denaturation, 30 s primer annealing at ∼ 60 °C, and 30 s extension at 72 °C; and, finally, 10 min of final extension at 72 °C. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were visualized on a 1.5 % agarose gel. Any samples showing a band at the expected size of ∼ 400 bp on the gel were subsequently purified using NucleoMag beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a 1 : 0.8 ratio of sample : beads. The purified samples were then indexed, using unique indexes that were added to each sample using i7 and i5 adapters (Illumina) to construct the final library. These indexed samples underwent another purification using the same NucleoMag bead procedure outlined above. These purified, indexed samples, representing each year of sampling (2019, 2020, 2021) were then pooled together at 5 µL each, where fainter samples were added at 10 µL. We only purified and pooled samples if our negative control was not amplified (no band on the gel), demonstrating no introduction of exogenous contamination during library preparation steps. The final quality of each pool was determined on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer at the Molecular Biology Service Unit (University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada) using a high-sensitivity DNA assay prior to submitting the library for 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The final prepared 2–4 nM libraries, containing up to 50 % PhiX Control V3 (Illumina, Canada Inc., NB, Canada; see below), were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq (Illumina Inc., CA, USA) using a 2×250 cycle MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 submitted to the Molecular Biological Services Unit (University of Alberta) in 2019 and to the Applied Genomics Core (University of Alberta) in 2020 and 2021. Sequence data were demultiplexed using MiSeq Reporter software (version 2.5.0.5) and MiSeq Local Run Manager GenerateFastQ Analysis Module 3.0. The assembled data were then processed using the Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME2) pipeline (Boylen et al., 2019, version 2021.11). Sequences were clustered into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), with chimeric sequences and singletons removed using DADA2 (Callahan et al., 2019). All representative sequences were classified with the SILVA v138 taxonomic database (Quast et al., 2012; Yilmaz et al., 2014) at the default similarity threshold of 80 %. ASV sequences that were identified as eukaryotes or chloroplasts were removed. Samples were decontaminated by removing ASVs present in a sequenced field blank using the prevalence method, with a threshold of 0.5 (Karstens et al., 2019; Parada et al., 2016b). No positive controls were included in our sequencing run because we spiked our pool quite heavily with PhiX (∼ 50 %), which is a quality control reagent commonly used in sequencing runs to optimize cluster generation, sequencing, alignment, and calibration control throughout the run. Because PhiX is a well-defined bacteriophage genome, it has a diverse base composition that provides the balanced fluorescent signal that low-diversity sample libraries, like ours, lack during each sequencing cycle (Illumina). A large proportion of PhiX was therefore added to increase the diversity of our oligotrophic pool. Following inspection of rarefaction curves (Fig. S1 in the Supplement), samples with less than 5000 reads were excluded from further analysis because they had not reached a plateau, indicating that sequencing did not capture a good representation of ASVs.

2.4 Data analysis

2.4.1 DOM absorbance and fluorescence calculations and PARAFAC analysis

EEMs were corrected for inner-filter effects, Raman normalized, blank corrected, and had Rayleigh and Raman scatter bands removed prior to parallel factor (PARAFAC) analysis (Murphy et al., 2013). PARAFAC analysis was performed in MATLAB (version 9.12.0) using the drEEM toolbox (version 0.6.5) (Murphy et al., 2013). PARAFAC models of up to seven components were assessed, and samples with high leverage were removed. A four-component model was validated using split-half analysis and was ultimately selected based on a low sum of square error and visual confirmation that only random noise remained in the residuals. Absorbance scans were utilized to calculate specific UV absorbance at 254 nm (SUVA254; a measure of DOM aromaticity) (Weishaar et al., 2003) and at the spectral slope coefficient between 275 and 295 nm (S275–295; a measure of DOM molecular weight) (Helms et al., 2008). Corrected fluorescence data were utilized to calculate the fluorescence index (FI) (McKnight et al., 2001b), humification index (HIX), and biological index (BIX) (Huguet et al., 2008) and the proportional contribution of common fluorescence peaks (peaks A, B, C, M, T; Coble, 1996). Further descriptions of absorbance- and fluorescence-based metrics are provided in Table S3.

2.4.2 Geochemistry

We ran linear mixed-effects models with distance (as kilometres downstream) and season (comparing winter, pre-melt, melt, and post-melt) as fixed effects and river and year as random effects to explore variations in geochemical parameters (OC concentration, OM character, OC isotopic composition, and water isotopes). We ran a type-II ANOVA on model outputs to assess significant main effects of distance and season and their interaction. When the effect of season was significant, the analysis was followed by Tukey-adjusted contrasts using estimated marginal means. A linear model was used to assess the relationship between Δ14C–DOC and protein-like PARAFAC components. We use deuterium excess as a proxy for glacial meltwater because it is known to increase with elevation (Bershaw and Lechler, 2019) and is thus typically higher in glacial ice (Souchez et al., 2000) and in water contributions from high-elevation snow (Bershaw et al., 2020) when compared to lower-elevation (downstream) water sources. To explore how DOM parameters varied across hydrologic seasons and with distance downstream, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed. Deuterium excess was fitted onto the ordinated PCA as a passive overlay (i.e., fit post-ordination) to not affect the analytical output using envfit (Oksanen, 2007).

2.4.3 Microbial analyses

To enable contrasts between sites most strongly influenced by glaciers (i.e., the headwater and near sites; 42 %–55 % snow and ice coverage in catchment; Table S1) and those further downstream (here, far sites with 6 %–12 % snow and ice coverage in catchment), the middle distance range sites were excluded from statistical analysis of the microbial samples. Alpha diversity was calculated on untransformed data using the Shannon index (Hill, 1973), and beta diversity was visualized using non-parametric multi-dimensional scaling (NMDS) using a Bray Curtis distance matrix created from Hellinger-transformed ASV abundance data (Ramette, 2007; Legendre and Gallagher, 2001). Significant differences between clusters determined a priori on the NMDS were assessed using permutational multivariate ANOVAs (perMANOVA), set at 999 permutations and using the Bray Curtis distance matrix. The clusters used for comparison included distance (headwater, near, and far), year, and river. We additionally constructed a Venn diagram in R to explore ASV overlap between headwater, near, and far sites, and we refer to ASVs present across all distance bins as a “core” assemblage below. To explore the possible role of environmental controls on microbial assemblage structure, we performed a backward selection distance-based redundancy analysis (db-RDA) on Hellinger-transformed ASV abundance data and non-correlated normally scaled environmental parameters. To do this, we first considered a broad suite of environmental parameters in a non-stepped RDA, including temperature, pH, specific conductance, turbidity, DOC concentration, DOM composition (percentage humic-like [see Sect. 3.1.1], FI, BIX, HIX, peak A, peak B, peak C, peak M, peak T, S275–295, SUVA254), nutrients (TP, TDN, dSi), major ions, and trace metals, and we used a variance inflation factor (VIF) of 10 as a benchmark to omit highly correlated parameters to avoid an over-parameterized model. The backward selection db-RDA was run on this streamlined set of parameters, and the percent variance of the model output was adjusted following the approach of Peres-Neto et al. (2006). An indicator species analysis (ISA) was performed on raw (non-transformed) ASV abundance data (Dufrêne and Legendre, 1997). Indicator values were compared to the Spearman rank correlation coefficient for the relationship between ASV abundance and deuterium excess to explore how the presence of indicator species varied across gradients of water source. We re-ran (i.e., as a check on output) NMDS and perMANOVA analyses using rarefied, rather than Hellinger-transformed, datasets to confirm the suitability of the Hellinger transformation for our analyses. Of our target sample set, we successfully obtained sequences from 72 samples, with ASV richness ranging from 81 to 9634 and read counts ranging from 5066 to 409 740; inspection of rarefaction curves confirmed that a plateau was reached for all included samples (i.e., those with more than 5000 reads; Fig. S1).

All data were analyzed within the R statistical language using the vegan (Oksanen, 2007), lme4 (Bates et al., 2015), car (Fox and Weisberg, 2019), emmeans (Lenth, 2024), stardom (Pucher et al., 2019), decontam (Davis et al., 2018), indicspecies (Cáceres and Legendre, 2009), dplyr (Wickham et al., 2023), and base packages (R Core Team, 2022). Variance adjustment within the db-RDA used the function “RsquareAdj”, and the perMANOVA was performed using the function “adonis”, both in vegan. Data visualization utilized the package ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016).

3.1 Spatial and temporal variation in stream organic matter characteristics

3.1.1 Water isotopes, DOC concentration, and DOM composition

In a model with sample year and river as random effects, deuterium excess declined with distance downstream (58.75; p<0.001) and varied seasonally (58.75; p<0.001), with deuterium excess values greater during melt seasons than during pre-melt seasons (p<0.001) (Fig. S2b; Tables S4, S5). δ18O–H2O also varied seasonally (; p<0.001), becoming more enriched from pre-melt to melt seasons (p=0.001) and from melt to post-melt seasons (p<0.023) (Fig. S2a; Tables S4, S5). A two-way ANOVA to assess differences in water source between the distance bins selected a priori showed deuterium excess to vary significantly between bins (, p<0.001), with Tukey post hoc comparisons showing headwater and near sites to be similar to each other (p=0.15) but all other bins to be significantly different from one another (p<0.001).

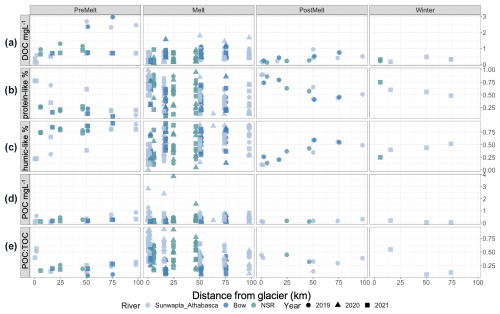

Figure 2Plots of (a) DOC concentration (in mg L−1) (b) relative percentage (%) of protein-like DOM, (c) relative percentage (%) of humic-like DOM, (d) POC concentration (in mg L−1), and (e) the ratio of POC to TOC (POC + DOC). Data are split by melt season and plotted against distance downstream, with river and year indicated.

DOC concentrations were universally low closest to the glacier (0.09–0.76 mg L−1) and increased with distance downstream (; p<0.001) (Fig. 2a, Table S4). Concentrations also varied seasonally (; p<0.001), with pre-melt concentrations being greater than those during melt (p<0.001), post-melt (p<0.001), and winter (p<0.001). However, a significant interaction suggests that these effects were not necessarily consistent (; p<0.001) (Fig. 2a; Tables S4, S5). Across all sites and dates, POC concentrations ranged from 0.04 to 2.8 mg L−1. POC was typically the dominant component of the total OC (TOC) pool at glacial headwaters (POC : TOC =0.32–0.89; median ratio >0.5 for all but pre-melt 2021; data not shown) and showed a proportional decline with distance downstream (18.31; p<0.001) (Fig. 2e, Table S4).

From the suite of PARAFAC models considered, a four-component model was selected (Fig. S3). Using the OpenFluor database (Murphy et al., 2014), components 1 (C1) and 2 (C2) were identified as humic-like components, component 3 (C3) was identified as a tryptophan-like (protein-like) component, and component 4 (C4) was identified as a tyrosine-like (protein-like) component (Table S6). The proportion of protein-like (sum of C3 and C4) and humic-like (sum of C1 and C2) components transitioned along transects, with humic-like DOM increasing proportionately with distance downstream, while protein-like DOM decreased proportionally (; p<0.001) (Fig. 2b–c, Table S4). Overall, the proportion of humic-like DOM was greater in the pre-melt period than during the melt (p=0.005) and post-melt (p<0.001) periods (Table S5).

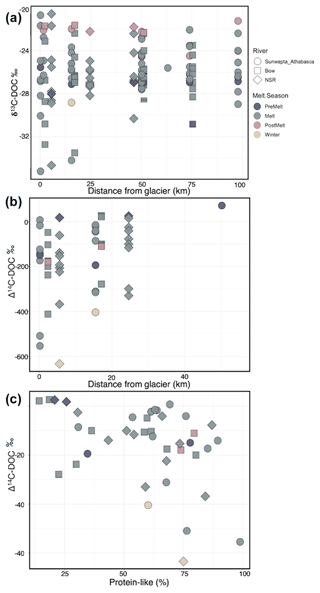

3.1.2 Dissolved and particulate OC isotopes

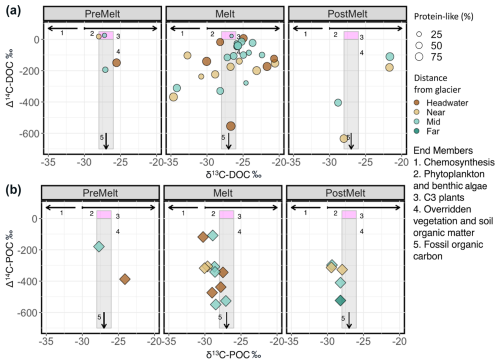

δ13C–DOC ranged from −35 ‰ to −20.2 ‰ (Figs. 3a and 4), showing a marginal enrichment with distance downstream (; p=0.059; Table S4) and significant variation across seasons (; p=0.022; Table S4), with depleted values during the pre-melt (p=0.050) and melt (p=0.035) seasons when compared to the post-melt season (Table S5). δ13C–POC ranged from −38.8 ‰ to −20.8 ‰ (Fig. 4b) and increased with distance downstream (; p=0.013) but with a significant interaction between distance and season (; p=0.013; Table S4). Δ14C–DOC became more enriched with increasing distance downstream (; p=0.014) but with high variability at the headwater site, particularly during the melt season (−554 ‰ to +7 ‰; n=8) (Figs. 3b and 4a). Δ14C–DOC also varied (; ), with values being most depleted during winter compared to during other seasons (p=0.020 to 0.001 for various comparisons) (Fig. 3b; Tables S4, S5). In addition, Δ14C–DOC showed a modest negative association with protein-like DOM (linear model 7, , p=0.007) (Fig. 3c). Similarly to Δ14C–DOC, Δ14C–POC exhibited a large range in values, from −550 ‰ to −108 ‰ (Fig. 4b). However, in contrast to Δ14C–DOC, the large variation in Δ14C–POC values was not associated with significant seasonal or spatial differences between samples (Fig. 4, Table S4).

Figure 3Plots of (a) stream δ13C–DOC as a function of increasing distance from glacier terminus, (b) stream Δ14C–DOC as a function of increasing distance from glacier terminus, and (c) the relationship between stream Δ14C–DOC and the relative percentage of protein-like DOM (%). River and melt season are indicated by the point shape and shading, respectively. Statistics for the relationships in (a) and (b) are provided in Table S4. A linear model of the relationship between Δ14C–DOC and protein-like DOM shows a significant negative slope (slope ; , , p=0.007).

Figure 4Δ14C versus δ13C values for (a) dissolved OC and (b) particulate OC for all sites and seasons combined. In panel (a), symbol size indicates the percentage of protein-like DOM in each sample. Symbol size variation is not applicable in (b). Different colours represent distance ranges. Numbered (1–5) pink and grey boxes and black lines represent literature isotopic ranges for various endmembers: (1) right arrow, (2) right arrow, (3) pink box, (4) grey box, (5) downwards arrow (Table S8).

3.1.3 An integrative assessment of DOM composition across sites

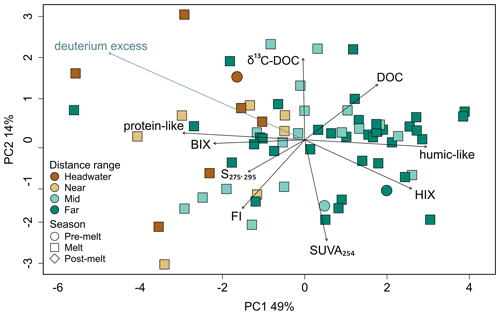

A PCA exploring DOM composition across sites identified eight principal components, with 64 % of the observed variation being explained by the first two principal component axes (Fig. 5). Principal component 1 (PC1) explained 49 % of the sample variance, with humic-like PARAFAC components, DOC concentration, and HIX (humification) loading positively on this axis and protein-like PARAFAC components, BIX (biological origin), FI (microbial origin), and S275–295 (declining molecular weight) loading negatively. Sites were generally plotted along PC1 according to their distance from glacier termini, with headwater and near sites more frequently having negative PC1 scores and far sites having more positive PC1 scores (Fig. 5). PC2 explained 14 % of the sample variance and was positively associated with δ13C–DOC and negatively associated with SUVA254 (aromaticity). A passive overlay of deuterium excess was negatively associated with PC1 and positively associated with PC2 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5Principal component analysis of dissolved OM parameters (DOC concentration, δ13C–DOC, S275–295, SUVA254, BIX, FI, HIX, protein-like DOM, and humic-like DOM). Deuterium excess (blue text) is a passive overlay. Colours represent distance range, and shapes represent hydrological period. Percentages along the axes are explained variance.

3.2 Microbial assemblage characterization and its controls over space and time

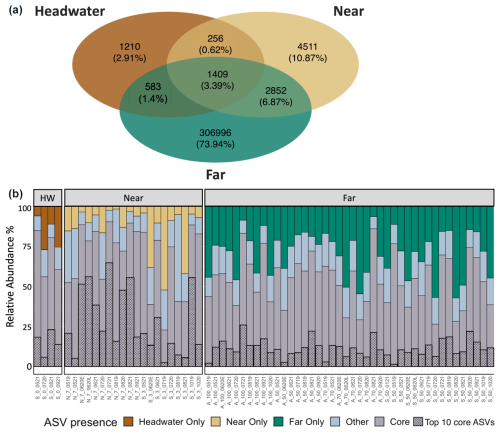

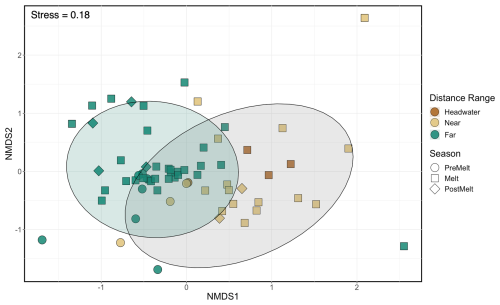

Generally, microbial assemblages shared similar dominant phyla and orders across sites and seasons, with the top 10 most abundant phyla across all samples being Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, Bacteroidota, Bdellovibrionota, Chloroflexi, Cyanobacteria, Firmicutes, Planctomycetota, Proteobacteria, and Verrucomicrobiota (Fig. S4). At near and far sites in the Sunwapta–Athabasca and North Saskatchewan rivers, these 10 phyla collectively described between 80 %–88 % of the resolved microbial assemblage composition (Fig. S4). Major microbial orders were dominated by Burkholderiales, Chitinophagales, Cytophagales, Flavobacteriales, Frankiales, Microtrichales, Sphingobacteriales, Synechococcales, and Vicinamibacterales (Fig. S5), with microorganisms related to Burkholderiales appearing to be most dominant, particularly in August at sites closer to the headwaters. Cumulatively, the top 10 orders accounted for 56 % of the total microbial assemblage composition. To explore taxonomic variation at a finer scale, we investigated shared ASVs across distance ranges (Fig. 6a). This assessment revealed a core microbial assemblage, shared among all our samples, comprised of 1409 ASVs in total, with the top 10 most abundant ASVs belonging to the families Comamonadaceae, Cyanobiaceae, Gallionellaceae, Ilumatobacteraceae, Sporichthyaceae, Alcaligenaceae, Methylophilaceae, and Flavobacteriaceae. While this core assemblage only represented 3.4 % of all identified ASVs (Fig. 6a), it made up a large fraction of relative abundance at each site (between 25 %–80 %; Fig. 6b), with a general decreased prevalence of the core assemblage at the far sites when compared to headwater and near sites. Accordingly, microbial assemblage diversity was highest at the far sites during all seasons (Fig. S6). Indeed, near sites showed a reduction in diversity from a median of 5.7 during pre-melt to a median of 4.3 during post-melt, whereas far sites increased in diversity throughout the melt season, from a median pre-melt diversity value of 6.5 to 6.8 at post melt. Further, a comparison of microbial diversity between samples (beta diversity) showed that assemblage composition shifted with movement from headwater and near sites to far sites (R2=0.09, p<0.001) (Fig. 7, Table S7). Assemblages were also distinct across rivers (R2=0.08, p<0.001; comparing the Athabasca, Sunwapta, and North Saskatchewan rivers) and different sampling years (R2=0.06, p<0.001; comparing 2019, 2020, and 2021), with each river and year being significantly different from one other (p<0.01) (Fig. S7, Table S7).

Figure 6(a) Venn diagram showing the number of identified ASVs at the headwater (n=4 samples), near (n=20), and far sites (n=42). (b) Bar plot showing the relative abundance of ASVs that are unique to each distance range, those ASVs identified in all three (headwater, near, far) distance bins (“core”), or those that are shared between two distance bins (“other”) in each sample. Sample abbreviations on the x axis indicate the river (Sunwapta (S), North Saskatchewan (N), Athabasca (A)), distance downstream (km), and sample date (mmyy); the suffixes “E” and “L” correspond to early and late in the associated sample month.

Figure 7NMDS of microbial assemblage composition across sites and sample dates. Shapes represent different hydrological periods, while colour indicates distance range. Shaded circles represent the 95 % confidence interval for significantly different groupings, where the far sites (green) were significantly different from the headwater and near sites (brown and tan; pairwise perMANOVA p<0.001 (Holm adjusted), R2=0.09). Headwater and near sites were not significantly different from one another. Table S7 shows statistical comparisons; plots separated by year and river are shown in Fig. S7.

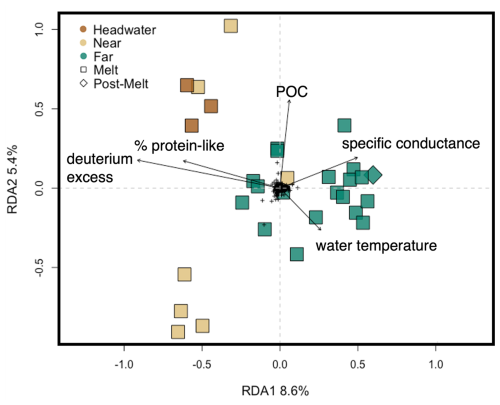

We used a db-RDA to assess how microbial assemblages varied across environmental gradients to better understand the role of environment in structuring assemblages at each of our sites. Removal of environmental variables with VIF >10 reduced the initially considered factors described in the Methods section (n=32) to the percentage of protein-like DOM, water temperature, DOC concentration, POC concentration, δ13C–DOC, δ18O–H2O, deuterium excess, S275–295, SUVA254, TN, TP, and specific conductance (n=12). Following backward selection, the final db-RDA described 9.1 % (adjusted; see Methods section) of the microbial assemblage structure, with the percentage of protein-like DOM, water temperature, specific conductance, POC, and deuterium excess identified as significant predictor variables (p<0.001) (Fig. 8). RDA axis 1 (RDA1) described a gradient of apparent high-elevation (e.g., glacial ice, snow) water source inputs, with deuterium excess and protein-like DOM being negatively correlated with this axis and specific conductance and water temperature being positively correlated with this axis (Fig. 8). RDA axis 2 (RDA2) showed water temperature loading negatively on this axis and POC loading positively (Fig. 8). Headwater sites were plotted negatively on RDA1 and positively on RDA2, whereas far sites tended to be plotted positively on RDA1. Overall, headwater microbial assemblages were associated with relatively higher proportions of protein-like DOM, deuterium excess, and POC but lower specific conductance and water temperature compared to assemblages at the far sites (Fig. 8).

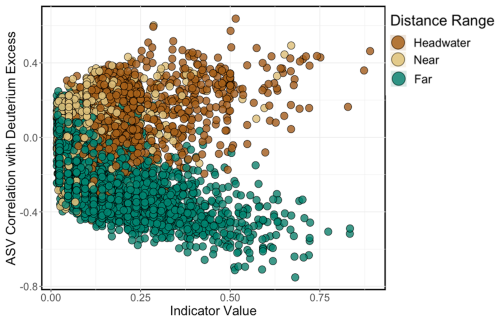

3.2.1 Indicator species analysis

An ISA resolved three strong (indicator value (IV) >0.8, p<0.05) indicator species for headwater sites and two strong indicator species for far sites. There were no strong indicator species for near sites at this IV threshold. Indicator species for the headwater sites were identified as an ASV from the genus Cryobacterium (IV =0.89), an ASV from the family Beggiatoaceae (IV =0.82), and an ASV from the family Microbacteriaceae (IV =0.87). Far indicators were an ASV from the family Sporichthyaceae (IV =0.83) and an ASV in the genus Cyanobium (PCC-6307) (IV =0.83). Correlations between ASV abundance and deuterium excess revealed that taxa indicative of headwater environments were strongly positively correlated with deuterium excess (positive ρ values), while taxa indicative of far environments showed a negative correlation (negative ρ values; Fig. 9).

4.1 Changing OM quantity and character driven by increased soil development downstream

Stream OM originates from two primary sources: (1) in situ primary production of OM from autotrophic microbes or macrophytes (autochthonous carbon) or (2) OM transported into the stream system from outside sources (allochthonous carbon) such as nearby vegetation and soils (Hinton et al., 1997, 1998; Tanentzap et al., 2014; Table S8). In glacially fed streams, glacially sourced OM also contributes to the allochthonous carbon pool (Hood et al., 2015a). However, glaciers are associated with a series of variable OM sources as a result of in situ microbial metabolism on the glacier surface (supraglacial) and at the glacier bed (subglacial) (Hotaling et al., 2017; Stibal et al., 2012), as well as of windblown deposition on the snow and ice surface and comminuted sediments and bedrock at the glacier bed (Hood et al., 2020; Stubbins et al., 2012). Thus, the changing water source contributions to streams is a critical determinant of fluvial OM composition, both in alpine environments and elsewhere (Fasching et al., 2016).

This study identified a shift in OC quantity and OM character with increasing distance downstream of glaciers and thus declining relative contributions of glacial meltwater and associated OM to streamflow. Low DOC concentrations in our mountain headwater streams, which drain catchments lacking developed soils and where dilute glacial meltwaters are the primary source of allochthonous carbon, are in agreement with previous work from the Alps (Singer et al., 2012), the Tibetan Plateau (Zhang et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2019b), the Canadian Rockies (Lafrenière et al., 2004), and the Greenland Ice Sheet (Kellerman et al., 2020). In contrast, the large relative contribution of POC to the headwater TOC pool is consistent with increased erosional processes in high-slope glacial-margin environments, export of glacially derived sediments (Hood et al., 2020), and higher rates of particle re-suspension in these high-gradient turbulent reaches (Marcus et al., 1992). At the headwaters, the protein-like character of the DOM pool suggests dominant contributions from microbial production or reworking of DOM, either on the glacier surface or at the bed, as has been found in many other glacierized regions (Zhou et al., 2019a; Dubnick et al., 2010; Hood et al., 2009; Stubbins et al., 2012; Pain et al., 2020; Singer et al., 2012). Increasing DOC concentrations and a shift from protein-like to humic-like DOM with increasing distance downstream supports increasing contributions of allochthonous carbon from surrounding vegetation and more developed soils (see also Zhou et al., 2019b). The conclusions that headwater sites receive a majority of their OM directly from the glacier and that downstream locations gain additional OM contributions derived from catchment soils are supported by declines in deuterium excess with movement downstream (Fig. S2, Table S4) and, thus, an inferred switch to increasing water contributions of rainfall and lower-elevation-sourced precipitation (Bershaw and Lechler, 2019; Bershaw et al., 2020).

4.2 Stream POC sourced from plant carbon with potential additions from glacier microbes

Compared to the DOC pool, the POC pool displayed less isotopic variation, pointing to a more consistent POC source for streams. Across seasons and with increasing distance downstream, POC was consistently aged (Δ14C–POC to −108 ‰). At the headwaters, this depletion likely indicates sourcing from glacial export of overridden vegetation (Bhatia et al., 2013) or fossil fuel products (Stubbins et al., 2012) and/or the heterotopic consumption of fossil fuels by cryoconite microbes (Margesin et al., 2002). Further downstream, radiocarbon-depleted POC could be sourced from the addition of water from aged soil margins or glacially exported aged POM that has persisted through the stream network (Hood et al., 2020). However, save for the headwater site during the pre-melt period, δ13C–POC indicated POM primarily of terrestrial origin (δ13C ‰ ‰ to −28 ‰), with occasional slight depletions at headwater and near sites (δ13C ‰ ‰ to −30 ‰) pointing to possible contributions from subglacial chemosynthetic biofilms (Table S8). Indeed, if some of the aged POM is sourced from subglacial microbes, this fraction of POM may be more accessible to recipient food webs than aged terrestrial POM (Brett et al., 2017), though relative contributions through our transects are likely to be small. The pre-melt headwater sample was uniquely δ13C enriched compared to other POM samples, which may suggest microbial re-working of δ14C depleted carbon sources as a more dominant POM source at this time.

4.3 Seasonal patterns in DOM from headwaters to downstream reaches

4.3.1 Glacial headwaters

Over the past 2 decades, studies from polar and alpine regions across the globe have led to the characterization of glacial DOM as being universally dilute, of microbial origin, and old (i.e., radiocarbon depleted) (Bhatia et al., 2013; Hood et al., 2009). Similarly, we found that DOM was consistently most protein-like in headwater reaches (Table S4) but with compositional variation during the melt season (Fig. 2). Our results contrast somewhat with other studies where melt season shifts in glacial-stream DOM character from relatively more humic-like to more protein-like have been associated with efficient subglacial channels during the peak melt season (Kellerman et al., 2020). For example, DOM fluorescence in the outflow draining Leverett Glacier, a large land-terminating glacier of the Greenland Ice Sheet, was relatively more humic-like in the early season, when waters draining subglacial flow paths access terrestrial material from previously overridden soils and bedrock-dominated stream contributions (Kellerman et al., 2020). In comparison, during peak melt flow, when supraglacial inputs dominated, Leverett Glacier outflow DOM had a distinctly more protein-like fluorescence signature (Kellerman et al., 2020). Similarly, protein-like fluorescence increased from the pre-melt to the melt period in waters draining from Mendenhall Glacier, Alaska (Spencer et al., 2014b). At these Rocky Mountain glacier sites, the variability in DOM source during the melt season may point to temporally patchy interactions with the overridden vegetation and paleosols known to be prevalent in this region (Luckman et al., 2020).

During the pre-melt period, water at the Athabasca Glacier terminus is predominately sourced from the distributed subglacial drainage network (Arendt, 2015), with DOC that was aged (Δ14C–DOC ) and with δ13C–DOC of −25.5 ‰ (Fig. 4). These carbon isotopic signatures, in conjunction with the consistent protein-like DOM fluorescence, suggest microbial reworking of previously overridden vegetation and soils at the glacier bed (Bhatia et al., 2013; Dubnick et al., 2010; see also Table S8). During the melt season, headwater δ13C–DOC shows substantial variation, in line with the DOM compositional variation described above. Four of six Δ14C–DOC samples from this period were relatively aged (Fig. 4); together with the relatively protein-like composition of the DOM pool, this isotopic variation is consistent with a range of sources, including (a) chemolithoautotrophy tied to microbial heterotrophic consumption of ancient vegetation and soil at the glacier bed (Hood et al., 2009), (b) microbial re-working of over-ridden vegetation, or (c) microbial incorporation of radiocarbon-dead fossil fuel combustion products deposited on the glacier surface (McCrimmon et al., 2018). Previous work in alpine glacial systems in both Alaska (Stubbins et al., 2012) and Tibet (Spencer et al., 2014a) has found the latter to contribute substantially to supraglacial DOC pools during peak melt periods. In a subset of melt season samples, however, headwater Δ14C–DOC was enriched (Fig. 4). This could be indicative of recent contributions from supraglacial photosynthetic microbes (Kellerman et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2017; Stibal et al., 2012) or contributions from wildfire-derived soot present on the glacier surface (Aubry-Wake et al., 2022; Nizam et al., 2020). Overall, the range of DOM composition, δ13C–DOC, and Δ14C–DOC points to striking heterogeneity of water sources draining to the glacial outflow at this site.

Figure 8Redundancy analysis of microbial assemblage structure at the headwater, near, and far sites constrained by environmental variables, with black arrows showing significant explanatory variables as determined by a backward selection analysis (see Methods section). The percentage variance explained by the first two RDA axes is shown on the axis labels. The full RDA has an adjusted R2 of 0.09 and an unadjusted R2 of 0.25. Colours represent distance range, and shapes represent hydrological period. Black crosses in the centre represent individual ASV scores.

4.3.2 Transit downstream

With transit downstream, DOM becomes more humic-like overall (Table S4) but with seasonal variability in character. During the pre-melt period, inputs of enriched Δ14C–DOC were coupled with δ13C–DOC values consistent with terrestrial OM inputs (−25 ‰ to −27 ‰) at the near and middle sites, likely indicative of snowpack melt draining surficial soils, leading to pulses of concentrated modern, terrestrial-origin DOM delivery to streams (Fig. 4). This flushing of concentrated DOM from soils was the likely cause of the spike in DOC concentration observed during the pre-melt season at downstream sites in 2019 (Fig. 2) when sampling captured the spring freshet. This process has been observed previously at Bow River for the period 1998–2000, when the highest DOC concentrations were found to occur during the initial snowpack melt and, as in this study, were followed by a decline in river DOC concentrations (Lafrenière and Sharp, 2004). These isotopic signatures were also tied to higher proportional inputs of humic-like DOM (Fig. 4).

During the melt season, a proportional increase in protein-like fluorescence at the near, middle, and far sites was coupled with DOM pools at near and middle sites switching from being consistent with allochthonous terrestrial inputs (δ13C–DOC to −29 ‰) to showing a clear autochthonous signature reflective of chemosynthetic or photosynthetic OM production (δ13C–DOC ranging from −35 ‰ to −20 ‰; Figs. 3 and 4). Near and middle sites were also characterized by DOM that was often Δ14C–DOC depleted. This trend may reflect increasing in situ production by microbial photoautotrophs, as evidenced by the presence of cyanobacteria DNA in the microbial amplicon libraries from these sites (Fig. S4) or by microbial re-working of humic-like DOM either within the stream or in catchment soils (Fig. 4). Aged carbon downstream likely represents the mixing of either (a) ancient glacially exported material from the headwaters persisting downstream or (b) additions from deeper, older soils (Shi et al., 2020). During the post-melt period, stream water at the near and middle sites was either aged (Δ14C–DOC , −400 ‰) with a δ13C–DOC terrestrial signature (−28 ‰, −29 ‰), consistent with OM contributions from deeper soils when discharge declines, or slightly more modern (Δ14C–DOC , −110 ‰) and δ13C enriched (−22 ‰), consistent with incorporation of autochthonous primary production into the DOM pool (Fig. 4). Future studies could consider a mixing model to add more specificity to these assessments via the inclusion of additional tracers to resolve the multiple endmembers of this system.

4.4 Implications of inferred composition for OM lability

The transition from recently produced, low-molecular-weight, protein-like DOM to high-molecular-weight, humic-like DOM with movement downstream has implications for DOM lability. Protein-like DOM is associated with free amino acids and proteinaceous compounds which are generally considered to be more available for heterotrophic microbial consumption (Coble, 1996), while factors such as decreasing molecular weight (S275–295) (Fig. 5, Table S3) are also associated with increasing OM lability (Moran and Zepp, 1997; Patriarca et al., 2021). In previous studies of glacial DOM, paired high-resolution mass spectrometry and UV–Vis spectrometry have shown that protein-like fluorescence is associated with unsaturated aliphatic compounds, identified as being peptide- and lipid-like (Kellerman et al., 2020, 2021; Stubbins et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2019a, b), which have been found to be a common contributor to glacier DOM pools in many regions (Singer et al., 2012; Bhatia et al., 2013; Kellerman et al., 2021; Stubbins et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2019a). In contrast, humic-like DOM is associated with complex material (e.g., increased lignin content; Mann et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2019b) and, thus, is generally considered to be a more recalcitrant fraction of DOM. This shift in lability has important implications for stream ecosystems because microbial consumption of DOM can provide an energetic transfer to higher trophic levels (e.g., Fellman et al., 2015), with labile DOM being linked to increased microbial productivity (Pontiller et al., 2020). Labile OM released at the headwater site could also initiate priming of the OM pool, resulting in increased microbial consumption of recalcitrant soil-derived OM (Bingeman et al., 1953; Guenet et al., 2010). Notably, the importance of priming has yet to be assessed in glacially fed streams (Bengtsson et al., 2018). However, despite the shift in apparent bulk DOM lability with movement downstream, one additional consideration is the low overall DOC concentration at headwater sites. Although downstream sites had lower proportions of protein-like DOM, these sites had higher DOC concentrations overall. A rough calculation to compare between sites yields an estimated mean of 0.28 mg L−1 for protein-like DOM at downstream sites compared to ∼ 0.21 mg L−1 at the headwater sites (using the mean DOC and percentage of protein-like DOM for each distance bin). Therefore, although DOM may have been more accessible to microbes on a proportional basis in the headwaters, overall OM processing may still have been higher downstream.

4.5 Controls on microbial assemblage structure with transit downstream

Microbial assemblages and OM pools are inherently linked since microbes contribute to both the creation of OM and its consumption (Kujawinski, 2011). To explore possible coupling between microbial assemblages and stream OM, we investigated how assemblages shifted with increasing distance from glaciers and coupled changes in OM source, OM character, and other physicochemical characteristics. Across all sites and seasons, 10 phyla were found to account for 80 %–88 % of the assemblage composition (Fig. S4). While some of these phyla (Actinobacteria, Acidobacteriota, Cyanobacteria, Bacteroidota, and Proteobacteria) are ubiquitous in freshwater (Tamames et al., 2010), many (Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, Chloroflexi, Cyanobacteria, Firmicutes, and Plantomycetota) are also commonly identified as being dominant in glacial ecosystems and in glacially fed streams (Boetius et al., 2015; Bourquin et al., 2022; Hotaling et al., 2019). These glacially associated phyla are known to include taxa that are adapted to the environmental conditions typical of glacial environments, such as oligotrophy and cold temperatures (Bourquin et al., 2022). At a finer taxonomic resolution, the orders Cytophagales, Chitinophagales, Vicinamibacterales, Burkholderiales, and Flavobacteriales are also commonly found in glacially fed waters (Kohler et al., 2020; Brandani et al., 2023; Guo et al., 2024). Burkholderiales and Flavobacteriales are known for their contributions to organic matter cycling in oligotrophic systems such as these (Guo et al., 2024). Interestingly, the order Sphingomonadales has also been shown to be significantly correlated with suspended sediment concentrations released from the Greenland Ice Sheet (Dubnick et al., 2017). Although our system is situated within the Canadian Rocky Mountains, similar controls on the incorporation of sediment occur as glaciers melt, seeding downstream rivers with sediment-associated microorganisms.

4.5.1 Poor evidence for species sorting along glacier to downstream gradients

At the ASV level, we observed some evidence for structured changes in microbial assemblages along the headwater connected to downstream reaches that we investigated. First, within-site (alpha) and between-site (beta) diversity increased with increasing distance from the glacier (Figs. 7, S6). This result is consistent with a previous study in the Alps, where lower alpha diversity near glaciers was attributed to a decrease in the diversity of microbial source pools at higher elevations (e.g., lower groundwater contributions) and/or harsher upstream environmental conditions (Wilhelm et al., 2013). Second, we identified microbial indicator species specific to each of the headwater and downstream sites. The headwater indicators Microbacteriaceae sp. and Microbacteriaceae Cryobacterium sp. are heterotrophs that are commonly found within glacial cryoconite holes and are believed to possess specific adaptations for cold temperatures and nutrient-poor conditions (Liu et al., 2020). The third headwater microbial indicator was a sulfur-oxidizing chemolithotroph (Beggiatoaceae sp.), likely sourced from the subglacial environment where chemosynthesis is common (Anesio et al., 2017). The identification of these indicator species suggests that unique microbes (sourced from both the supraglacial and subglacial environments) may be seeding the fluvial microbial assemblage at the glacial headwaters (Wilhelm et al., 2013; Bhatia et al., 2006). Third, db-RDA identified a series of physicochemical variables – including protein-like DOM, water temperature, POC concentration, specific conductance, and deuterium excess – that were significantly associated with microbial assemblage composition across sites (Fig. 8). Of these environmental controls, DOM character can select for different specialized heterotrophic microbes (Judd et al., 2006); water temperature broadly controls rates of microbial activity (D'Amico et al., 2006); and POC can shape bacterial extracellular enzyme requirements and, thus, microbial assemblage composition (Kellogg and Deming, 2014). From these lines of evidence, we conclude that glaciers provide a biotic source of novel microbes to glacially fed streams in the Rocky Mountains (see also Wilhelm et al., 2013; Bhatia et al., 2006) but that the association between assemblage structure and environment is modest, with the db-RDA explaining only a small amount (9 %) of the observed variation in microbial assemblages across sites (Fig. 8).

4.5.2 Dispersal and increasing cell sources with transit downstream

In addition to the overall modest db-RDA results, perMANOVA tests of species divergence among site bins (i.e., beta diversity) indicated that spatial variation only explained a small proportion of assemblage composition, suggesting a high degree of similarity between assemblages (R2=0.09, p<0.001, Table S7). This low overall explanatory power of specific environmental controls, combined with a lack of strong assemblage divergence between environmentally disparate sites, is consistent with a past synthesis effort that concluded that environmental drivers are not always good predictors for microbial assemblage composition in streams (Zeglin, 2015).

This lack of strong control from among our suite of environmental variables is also consistent with patterns observed for the core group of microbial ASVs that was ubiquitous across all distance ranges (headwater, near, far) examined in this study. While this core ASV group accounted for only ∼ 3 % of the total identified ASVs, it represented a large proportion of average relative ASV abundance across sites, ranging from a median of 70 % of the total assemblage relative abundance at headwater locations to 55 % at downstream sites (Fig. 6). Across all sites, the most abundant (top 10) core ASVs, identified to the lowest taxonomic level available, display diverse metabolisms, with some heterotopic taxa that are considered to be generalists (e.g., Flavobacterium sp., Zheng et al., 2019; Sporichthyaceae); specialists for methanol consumption (Methylophilaceae, Beck et al., 2014); and specialists for the consumption of terrestrial carbon (Alcaligenaceae) and autotrophic taxa, including both photoautotrophs (e.g., cyanobacteria) and chemoautotrophs (e.g., iron-oxidizing Gallionellaceae, Hallbeck and Pedersen, 2014). Increases in alpha diversity and declining relative importance of the core assemblage from headwaters to downstream sites indicate more diverse assemblages downstream, consistent with an increased variety of microbial sources from the surrounding terrestrial environment (Figs. 6, S6). However, the strong persistence of the core assemblage across our transects also reinforces the fact that rivers are highly connected environments that can facilitate high rates of dispersal (Tonkin et al., 2018), albeit in a unidirectional fashion. As such, mass effects can be strong drivers of microbial assemblage composition in fluvial networks, resulting in assemblage homogenization and, overall, decreased species sorting (Crump et al., 2007; Evans et al., 2017; Leibold et al., 2004; Pandit et al., 2009). These findings contrast with those from studies of more isolated environments such as lakes (Logue and Lindström, 2010; Van der Gucht et al., 2007) and soils (Fierer and Jackson, 2006), where longer residence times better enable environmental divergence between sites to drive divergence in microbial assemblage composition. In our glacially fed systems in particular, we find that, while local environmental conditions show some association with microbial assemblage composition, mass effects (homogenization by high rates of dispersal) are likely more influential, suggesting a clear ecological connection from glacial outflows to 100 km downstream sites despite striking environmental change.

This study illustrates that fluvial OM quantity and quality change along stream transects from glacier headwaters to ∼ 100 km downstream in the Rocky Mountains. These changes occur as a result of shifting inputs from different OM sources, with headwater sites adjacent to the glacier containing DOM that is compositionally consistent with predominantly autotrophic inputs (chemosynthesis and photosynthesis) and microbial reworking of terrestrially sourced OM that is aged and likely to be labile. Comparatively, the downstream DOM pool was predominately humic-like but exhibited seasonal shifts in the apparent OM source with some allochthonous inputs in the pre-glacial melt and post-glacial melt seasons and autochthonous sources increasing at the height of the melt season. This study also identified that a portion of glacially exported POC may be sourced from microbial activity and, thus, is potentially accessible to downstream food webs. In contrast to these clear environmental gradients, we found that, despite evidence for glacial seeding of headwater microbial assemblages, mass effects appeared to enable the dispersal of a persistent core microbial group throughout our stream transects from the glacial headwaters to ∼ 100 km downstream. Increasing microbial assemblage diversity with movement downstream, in the absence of a strong correlation with in-stream physical and chemical conditions, points to a greater diversity of cell sources (i.e., increasing lateral inputs) along our study continuum.

Overall, findings from this work will enable better predictions about the impacts of glacial retreat on stream ecosystems and the loss of labile OM inputs in alpine headwater regions. In the future, with increased glacier retreat in the Canadian Rockies, glacially fed rivers will shift from a glacier ice melt regime towards one dominated by seasonal snow and rainwater inputs (Pradhananga and Pomeroy, 2022). Necessarily, these changes will be accompanied by increases in surrounding soil development and vegetation cover. The likely result is a higher proportion of humic-like DOM at headwater sites, a potential loss of glacially derived POM bioavailable to downstream primary-consumer organisms, and changes in other environmental parameters (temperature, chemistry) identified in this study as being important correlates for stream microbial assemblages. At the same time, a loss of glacially exported microbes will alter the seed pool at headwater sites, which appears to persist far downstream, thus potentially altering the core assemblage that is characteristic of this glacially fed river system. Overall, glacier retreat and eventual deglaciation appear to be poised to cause a loss of glacial seeding of microbial assemblages in headwaters of the Canadian Rockies, similarly to predictions for other glacierized alpine regions (Hotaling et al., 2017). This loss of a unique source pool to the base of stream food webs could have a negative impact on overall biodiversity and ecosystem functioning, particularly if this loss in inputs decreases the functional breadth of these systems.

All water chemistry and organic matter datasets generated and analyzed in this study are available on the PANGAEA repository https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.963863 (Serbu et al., 2023; Felden et al., 2023) and https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.975984 (Drapeau et al., 2025). Microbial 16S rRNA gene sequences generated and used in this study can be accessed from the NCBI database using accession no. PRJNA995204 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=995204, BioProject, 1988).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-22-1369-2025-supplement.

VLSL, JAS, SET, and MPB designed the field program, and SET and MPB designed this study. HFD and JAS led the field sampling campaigns, and HFD, MAC, and JAS conducted the laboratory analysis. MAC built the 16S rRNA gene libraries and conducted the bio-informatic analyses. HFD conducted all other data and statistical analyses and visualized the results. HFD wrote the paper with input from SET and MPB, and all the authors provided comments on the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

Data collected via fieldwork were approved under permit nos. JNP-2018-29597 (Jasper National Park) and LL-2019-32266 (Banff National Park). We are grateful to Lakoda Thomas, Samuel Metacat-Yah, Rory Buford, Patrick White, Sydney Enns, and Janelle Flett for the invaluable assistance in the field. Lakoda Thomas and Samuel Metacat-Yah were funded by the University of Alberta I-STEAM program and an NSERC USRA award (to Lakoda Thomas). Rory Buford was funded by a Mitacs Globalink Research Award. We would like to thank the Biogeochemical Analytical Service Laboratory (BASL; University of Alberta) and the Canadian Centre for Isotopic Microanalysis (CCIM; University of Alberta) laboratory managers and staff for their role in the analysis of our samples. Hayley F. Drapeau was funded in part by an NSERC CGS-M postgraduate fellowship. We acknowledge that the University of Alberta is on Treaty 6 territory and that fieldwork was conducted on Treaty 7 and 8 territories. Jasper National Park and Banff National Park are located on the lands of the Ktunaxa, Rocky Mountain Cree, Stoney, Blackfoot/Niitsítapi, Secwépemc, Tsuut'ina, Métis, and Mountain Métis people. Finally, we are grateful to Martin Sharp for the illuminating discussions.

This research has been supported by the Networks of Centres of Excellence of Canada (Canadian Mountain Network), Campus Alberta Innovates Program (CAIP) funding to MPB and SET, Alberta Conservation Grant in Biodiversity to HFD (grant no. 030-00-90-140/1068), and I-STEAM Pathways program funding to Maya P. Bhatia and Suzanne E. Tank.

This paper was edited by Steven Bouillon and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Anderson, S. and Radić, V.: Identification of local water resource vulnerability to rapid deglaciation in Alberta, Nat. Clim. Change, 10, 933–938, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0863-4, 2020.

Anesio, A. M., Lutz, S., Chrismas, N. A. M., and Benning, L. G.: The microbiome of glaciers and ice sheets, npj Biofilms Microbiomes, 3, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-017-0019-0, 2017.

Arendt, C. A.: The Hydrologic Evolution of Glacial Meltwater: Insights and Implications from Alpine and Arctic Glaciers, PhD thesis, University of Michigan, 176 pp., 2015.

Arendt, C. A., Stevenson, E. I., and Aciego, S. M.: Hydrologic controls on radiogenic Sr in meltwater from an alpine glacier system: Athabasca Glacier, Canada, Appl. Geochem., 69, 42–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2016.04.002, 2016.

Aubry-Wake, C., Bertoncini, A., and Pomeroy, J. W.: Fire and Ice: The Impact of Wildfire-Affected Albedo and Irradiance on Glacier Melt, Earth's Future, 10, e2022EF002685, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EF002685, 2022.

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., and Walker, S.: Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4, J. Stat. Softw., 67, 1–48, https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01, 2015.

Beck, D. A. C., McTaggart, T. L., Setboonsarng, U., Vorobev, A., Kalyuzhnaya, M. G., Ivanova, N., Goodwin, L., Woyke, T., Lidstrom, M. E., and Chistoserdova, L.: The Expanded Diversity of Methylophilaceae from Lake Washington through Cultivation and Genomic Sequencing of Novel Ecotypes, PLOS ONE, 9, e102458, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102458, 2014.

Bengtsson, M. M., Attermeyer, K., and Catalán, N.: Interactive effects on organic matter processing from soils to the ocean: are priming effects relevant in aquatic ecosystems?, Hydrobiologia, 822, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-018-3672-2, 2018.

Bernhardt, E. S., Savoy, P., Vlah, M. J., Appling, A. P., Koenig, L. E., Hall, R. O., Arroita, M., Blaszczak, J. R., Carter, A. M., Cohen, M., Harvey, J. W., Heffernan, J. B., Helton, A. M., Hosen, J. D., Kirk, L., McDowell, W. H., Stanley, E. H., Yackulic, C. B., and Grimm, N. B.: Light and flow regimes regulate the metabolism of rivers, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 119, e2121976119, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2121976119, 2022.