the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Aqueous system-level processes and prokaryote assemblages in the ferruginous and sulfate-rich bottom waters of a post-mining lake

Daniel A. Petrash

Ingrid M. Steenbergen

Astolfo Valero

Travis B. Meador

Tomáš Pačes

Christophe Thomazo

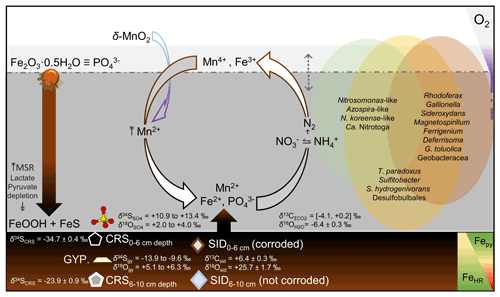

In the low-nutrient, redox-stratified Lake Medard (Czechia), reductive Fe(III) dissolution outpaces sulfide generation from microbial sulfate reduction (MSR) and ferruginous conditions occur without quantitative sulfate depletion. The lake currently has marked overlapping C, N, S, Mn and Fe cycles occurring in the anoxic portion of the water column. This feature is unusual in stable, natural, redox-stratified lacustrine systems where at least one of these biogeochemical cycles is functionally diminished or undergoes minimal transformations because of the dominance of another component or other components. Therefore, this post-mining lake has scientific value for (i) testing emerging hypotheses on how such interlinked biogeochemical cycles operate during transitional redox states and (ii) acquiring insight into redox proxy signals of ferruginous sediments underlying a sulfatic and ferruginous water column. An isotopically constrained estimate of the rates of sulfate reduction (SRRs) suggests that despite high genetic potential, this respiration pathway may be limited by the rather low amounts of metabolizable organic carbon. This points to substrate competition exerted by iron- and nitrogen-respiring prokaryotes. Yet, the planktonic microbial succession across the nitrogenous and ferruginous zones also indicates genetic potential for chemolithotrophic sulfur oxidation. Therefore, our SRR estimates could rather be portraying high rates of anoxic sulfide oxidation to sulfate, probably accompanied by microbially induced disproportionation of S intermediates. Near and at the anoxic sediment–water interface, vigorous sulfur cycling can be fuelled by ferric and manganic particulate matter and redeposited siderite stocks. Sulfur oxidation and disproportionation then appear to prevent substantial stabilization of iron monosulfides as pyrite but enable the interstitial precipitation of microcrystalline equant gypsum. This latter mineral isotopically recorded sulfur oxidation proceeding at near equilibrium with the ambient anoxic waters, whilst authigenic pyrite sulfur displays a 38 ‰ to 27 ‰ isotopic offset from ambient sulfate, suggestive of incomplete MSR and open sulfur cycling. Pyrite-sulfur fractionation decreases with increased reducible reactive iron in the sediment. In the absence of ferruginous coastal zones today affected by post-depositional sulfate fluxes, the current water column redox stratification in the post-mining Lake Medard is thought relevant for refining interpretations pertaining to the onset of widespread redox-stratified states across ancient nearshore depositional systems.

- Article

(5366 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1824 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The biogeochemical reactions governing the distinctive redox structure of modern permanently stratified lakes have been studied, for the most part, in natural settings featuring relatively high dissolved iron but low sulfate concentrations (Swanner et al., 2020). Improved by insights from laboratory experiments (e.g., Konhauser et al., 2007; Rasmussen et al., 2015; Jiang and Tosca, 2019), geochemical and microbiological analyses made in such lacustrine systems have provided us with an empirical framework to interpret modern iron biomineralization mechanisms and, by analogy, similar processes that determined a secular trend in the stratigraphic distribution of iron formations in the Precambrian.

Lakes that display permanent stagnation and marked redox gradients in their water column are termed meromictic. Meromictic lakes featuring ferruginous conditions in their water columns (i.e., [Fe2+] > [] and [Fe2+] > []) are relevant to deciphering the environmental significance of specific chemical and isotopic signals recorded in iron-rich deposits and to advance paleoenvironmental interpretations of redox-stratified oceans, such as those prevalent during the Precambrian (Canfield et al., 2018) or intermittently developed during the Phanerozoic (Crowe et al., 2008; Walter et al., 2014; Posth et al., 2014; Lambrecht et al., 2018; Canfield et al., 2018; Swanner et al., 2020; Reershemius and Planavsky, 2021).

Ferruginous water columns that also contain elevated dissolved sulfate concentrations are not uncommon in acidic shallow pit lakes (e.g., Denimal et al., 2005; Trettin et al., 2007) and have also been reported in pH-neutralized post-mining lakes (McCullough and Schultze, 2018). Lake Medard, in NW Czechia (Fig. 1), belongs to this latter group. The newly formed lake features low nutrient contents (i.e., it is oligotrophic), and its temperature-, redox- and salinity-stratified water column (Fig. 2a) remains unmixed throughout the year. Given its recent water-filling history – completed in 2016 – and the fact that its ferruginous bottom waters contain up to 21 mM of dissolved sulfate (Petrash et al., 2018), this oligotrophic lake can be considered a large-scale incubation experiment featuring an imbalanced sulfatic transition between aqueous ferruginous and euxinic redox states. The latter redox state is defined by an abundance of dissolved sulfide able to titrate dissolved Fe2+ out from solution (Scholz, 2018; van de Velde et al., 2021).

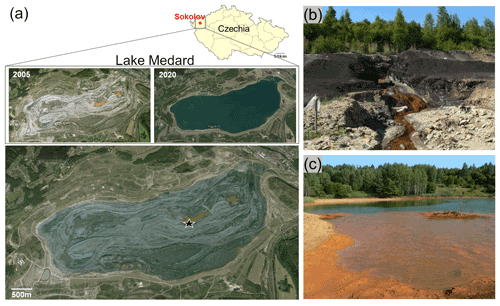

Figure 1The area now occupied by the post-mining Lake Medard was previously an open-cast coal mine near Sokolov, NW Czechia. Upon mine abandonment, the deepest parts of the open-cast mine became shallow acidic pit lakes and are now the lake depocentres. The deeper zone of the lake now features ferruginous and sulfate-rich aqueous conditions, but the pH is circumneutral. The star marks the central sampling location in a recent lake imagery superimposed on the 2005 mine-pit imagery (a). The mine pit had important fluxes of solutes linked to pyrite oxidation in exploited coal seams and their associated pyrite-bearing lithologies (b–c). These fluxes may still affect the hydrochemistry of the present-day lacustrine system; i.e., solutes are currently sourced from now submerged lithologies that also bear pH-neutralizing carbonates (Appendix A). Imagery dates 19 May 2020 (© CNES/Airbus) and 1 January 2004 (© GEODIS Brno). Historical photographic record by courtesy of the Czech Geological Survey.

Here we combined spectroscopic analyses of the hypoxic (i.e., 2.0 to 0.2 mg O2 L−1), nitrogenous and ferruginous, and ultimately anoxic (<0.03 mg O2 L−1) ferruginous and sulfatic bottom water column of Lake Medard. System-level processes that can be linked to specific planktonic prokaryote functionalities were interpreted. For this aim, isotope ratios of carbon and oxygen in dissolved inorganic carbon, sulfur and oxygen in dissolved sulfate, and concentration profiles of bioactive ions and volatile fatty acids (VFAs) were measured together with a 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequence profile. Amplicon gene sequencing informed our ecological and biogeochemical interpretations despite quantitative biases that are inherent in this type of data (Salcher, 2014; Piwosz et al., 2020). To complement our interpretations, we also conducted mineralogical analyses and a mineral-calibrated wet chemical speciation study of reactive Fe and Mn pools in the upper anoxic sediments. Using these data, we developed a mechanistic model that assesses the potential regulatory roles of prokaryotes over the geochemical gradients detected in the water column and their influence over interlinked biogeochemical cycling involving reactive minerals. Consumption and replenishment of iron, sulfur (S), carbon (C), nitrogen (N) and manganese (Mn) across the redoxcline and near the anoxic sediment–water interface (SWI) are presented as a set of geochemical reactions. These reactions differentiate distinctive niches where a phylogenetically and metabolically diverse planktonic microbial community induce vigorous elemental recycling.

Our observations in this unique lake are thought relevant since analogue aqueous-level system processes would have also operated in some ancient ferruginous coastal settings. Lake Medard could therefore offer valuable information to further understand early diagenetic signals resulting from analogue microbial ecosystem dynamics. When preserved in the rock record, such signals could be elusive and reflective, for instance, of ferruginous nearshore facies affected by continental sulfate delivery during shallow burial. In this regard, our research furthers understanding of the cryptic S cycle under ferruginous conditions unaccompanied by quantitative dissolved sulfate exhaustion.

Reclamation (flooding) of land occupied by the decommissioned Medard open-cast lignite mine in the Sokolov mining district of Karlovy Vary, northwest Czechia, led to the ca. 4.9 km2 (∼ 60 m max. depth) post-mining Lake Medard (Fig. 1a; 50∘10′41′′ N, 12∘35′46′′ E). The lake was filled with waters diverted for reclamation purposes from the nearby river Eger (Ohře). The filling of the former open-cast mine pit with river water started in 2010 and was reportedly completed by 2016 (Kovar et al., 2016). During closure and abandonment of the former mine pit, dissolved iron and sulfate – the latter derived from pyrite oxidation – leached towards initially shallow ephemeral and acidic pit lakes formed as surficial and groundwater filled the mine pit (Fig. 1b–c). In these mining-impacted brines, metastable Fe(III) oxyhydroxides and Fe(III) oxyhydroxysulfates precipitated (Murad and Rojík, 2005). Runoff also affected the hydrochemistry of the ensuing shallow pit lake (Fig. 1b–c) by carrying solutes sourced from weathered Miocene tuffaceous and carbonate-rich lacustrine claystones associated with the mined coal seam. These lithological units were described by Kříbek et al. (2017).

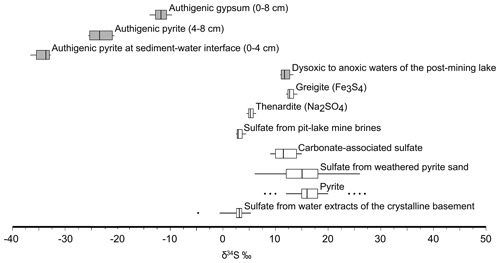

At present, Lake Medard exhibits density, temperature and marked redox stratification in its hypolimnion that is hypoxic (0.2 to 0.03 mg O2 L−1) to anoxic (Fig. 2a) and ferruginous (Petrash et al., 2018). Water–rock interactions down to the underlying granitic basement also influence the hydrochemistry of the modern lake. Percolation and subsurface flow of meteoric water cause dissolution of fault-related thenardite (Na2SO4) accumulations. Thenardite dissolution and groundwater reflux introduce significant loads of isotopically heavy sulfate into the present-day hydrological system (Pačes and Šmejkal, 2004). Additional details on the geological framework of the area and its influence over the hydrochemistry of the post-mining lake are in Appendix A.

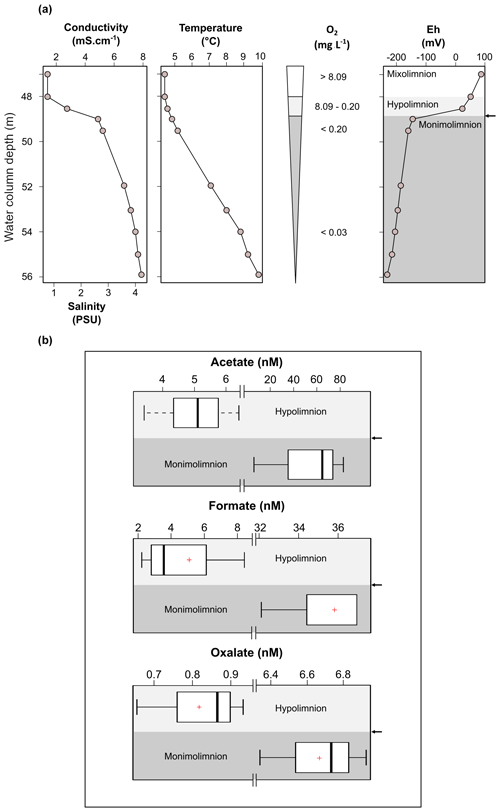

Figure 2Physicochemical parameters in the dysoxic to anoxic waters of Lake Medard in its central sampling location, which has a maximum depth of 56 m (a), and concentration range of acetate, formate and oxalate quantified in the dysoxic (n=4; <48 depth) and anoxic (n=3; 54–55 m depth) waters of Lake Medard (b). The arrow shows the redoxcline.

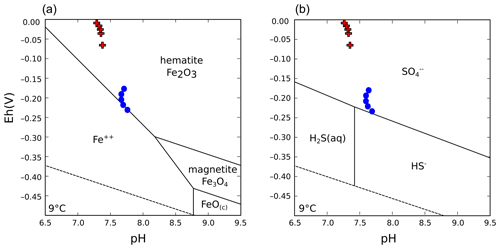

Water column stratification was already observed in 2009, when environmental monitoring of the shallow pit lake formed after decommissioning of the dewatering wells took place (e.g., Medová et al., 2015). In the current deep post-mining lake, both abiotic and microbially mediated precipitation of poorly crystalline iron minerals – i.e., amorphous ferric hydroxide (Fe(OH)3) and metastable nanocrystalline ferrihydrite (Fe2O3 • (H2O)n) – occurs near the pelagic redoxcline (i.e., the redox transition between low dissolved oxygen and anoxic waters, Fig. 2a), from where these solid phases are exported to the SWI (Petrash et al., 2018). Mineral equilibrium reactions at the SWI proceed mostly within the nitrogenous to ferruginous redox potentials (Eh) and at a circumneutral to moderately alkaline pH. Stability diagrams showcasing the predicted stability of S and Fe species in the bottom waters of Lake Medard are shown in Fig. B1 (Appendix B). The stability diagrams show that the current physicochemical conditions of the bottom sulfatic waters favour colloidal Fe(III)-oxyhydroxide formation, but ferruginous monimolimnial waters also occur.

3.1 Water sampling and analyses

3.1.1 Physicochemical parameter measurements and water column sampling

A water quality monitoring and profiling probe (YSI 6600 V2-2) was used – prior to sampling – to measure conductivity, temperature, O2 concentrations, pH and Eh in the stratified portion of the water column of Lake Medard (from 47 to 55 m depth) in its central location (Fig. 1a, star). The probing resolution was 1 m above and below the O2 minimum zone and 0.5 m at the redoxcline. Based on the profiles, water column samples (n=8; four replicates) were collected (in November 2019) using a Ruttner sampler with a capacity of 1.7 L. Flushing and rinsing of the sampling device with distilled water (dH2O) were performed between samples. A total of eight samples were taken at depths of 47, 48, 48.5, 49, 50, 52, 54 and 55 m. Replicate samples were taken at depths of 47, 48.5, 50 and 54 m below the lake water surface. On aliquots of our water samples, we performed (i) prokaryote DNA extraction followed by MiSeq Illumina 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing; (ii) mass determinations of cations (iron, manganese, potassium, sodium, magnesium and calcium); (iii) high-pressure liquid chromatography for concentrations of chlorine, sulfate, nitrate, ammonium and phosphate anions, and VFA abundances; (iv) measurement of dissolved inorganic carbon and methane concentrations; (v) isotope ratio analyses of δ13C in total dissolved inorganic carbon and methane; and (vi) isotope ratio analyses of δ34S and δ18O values in dissolved sulfate. Details on these analyses follow.

3.1.2 Environmental microbial DNA sampling

For each DNA sampling depth, an aliquot of 1 L was transferred to polyethylene (PET) bottles using a hand pump connected to sterile a Sterifil® aseptic system loaded with sterile cellulose nitrate Whatman® MicroPlus-21 ST filters (0.45 µm cutoff, 47 mm diameter). The filters were separated from the filtrating apparatus using a pair of sterilized tweezers (70 % ethanol and Bunsen burner) and transferred into sterile 2 mL Cryotube vials (Thermo Scientific). These were stored in liquid N2 for transport to the lab, where DNA extraction from the biomass collected on the filters took place. After each sample collection, the filtration apparatus was rinsed three times with dH2O and a new filter was carefully placed onto the apparatus. Samples for 16 S rRNA gene analyses were collected from the two redox compartments of the lake: the hypoxic hypolimnion and anoxic monimolimnion. The rinsing water (1 L) prior to the second-last sampling (52 m) was used as a control.

3.1.3 Microbiome profile

DNA was extracted from the water filters described above using a Quick-DNA Soil Microbe Kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of 11 water replicates (i.e., 47 to 54 m depth and replicates) were evaluated. The DNA extracted from these samples was ≥6 ng as per Qubit dsDNA BR fluorometric assays (Life Technologies) and below limits of quantification (< LQs) for the control (i.e., nucleic acids <0.2 ng). DNA integrity was assessed by agarose gel (2 %) electrophoresis.

A two-step PCR protocol targeting the small subunit 16S rRNA gene in bacteria and archaea was conducted using the universal primer combinations 341F/806R (CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG and GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT) and 519F/915R (CAGCCGCCGCGGTAA and GTGCTCCCCCGCCAATTCCT), respectively. The samples were sequenced on the MiSeq Illumina platform. The 16Ss rRNA gene amplicon datasets were analyzed with a pipeline consisting of an initial step where all reads passing the standard Illumina chastity filter (PF reads) were demultiplexed according to their index sequences. This was followed by a primer clipping step in which the target forward and reverse primer sequences for bacteria and archaea were identified and clipped from the starts of the raw forward and reverse reads. Only read pairs exhibiting forward and reverse primer overlaps were kept for merging by using FLASH 2.2.00 (Magoč and Salzberg, 2011). This yielded a total of 1 799 339 high-quality sequence reads, with an average length after processing of 412 bp.

Sequence features (herein described as representative operational taxonomic units, OTUs) were clustered using QIIME 2 (VSEARCH cluster-features-de-novo option; Rognes et al., 2016). To assign taxonomic information to each OTU, we performed DC-MegaBLAST alignments of cluster-representative sequences regarding the NCBI sequence database (release 10 October 2019). A taxonomic assignment for each OTU was then transferred from the set of best-matching reference sequences (lowest common taxonomic unit of all best hits). Hereby, a sequence identity of >70 % across at least ≥ 80 % of the representative sequence was a minimal requirement when considering reference sequences. We assigned significant tentative correspondence of OTUs to reference species provided that identity thresholds ≥ 97 % of the V3–V4 hypervariable region for bacteria and V4–V5 for archaea were meet. Further processing of OTUs and taxonomic assignments (75.8 % of the sequences after chimera detection and filtering; Edgar et al., 2011) and read abundance estimation for all detected OTUs were performed using the QIIME 2 software package (version 1.9.1, Caporaso et al., 2010). Abundances of bacterial and archaeal taxonomic units were normalized using lineage-specific copy numbers of the relevant marker genes to improve estimates (Angly et al., 2014). The microbial sequence data for this study (lengths ≥ 402 bp) were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) at EMBL-EBI under accession number PRJEB47217.

3.1.4 Cation concentration analyses

For cation concentration analyses, aliquots of 15 mL were filtered using sterile, high-flow, 28 mm diameter, polyethersulfone (PES) filters to remove particles >0.22 µm and then placed in acid-cleaned, PET centrifuge tubes. The aliquots were acidified using concentrated trace metal grade HNO3. At the lab these water aliquots were digested with trace metal grade HNO3 (8 N) and were sent for analyses at the Pôle Spectrométrie Océan at IUEM in Brest, France. A Thermo Element 2 high-resolution inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer set to solution mode was used. The data were calibrated against multi-element standards at concentrations that were measured repeatedly throughout the session. Multi-element solutions were measured at the beginning, end and twice in the middle of the sequence, and a 5 µg L−1 standard was further repeated after every five samples throughout the sequence. Additionally, 5 ppb indium (In) was added directly to the 2 % HNO3 diluent employed to prepare all standard solutions and was used to monitor signal stability and correct for instrumental drift across the session. Each sample and standard were bracketed by a rinse composed of the same diluent (i.e., the 2 % HNO3 with In), for which data were also acquired to determine the method detection limit. Relative standard deviations (2σ level) were better than 0.01 % for Fe and Mn, and between 0.001 % and 0.002 % for other analyzed elements, e.g., K, Na, Mg and Ca, concentrations of which were used for aqueous-mineral equilibrium modelling (Appendix A, also Supplement 1 – PHREEQC modelling input/results).

3.1.5 Ions, ammonia and VFA concentration analyses

Alkalinity (i.e., the capacity of water to neutralize free hydrogen ions, H+) was measured as HCO via acidometric titration of filtered water samples. The titrations were conducted on board immediately upon sample collection by using 0.16 N sulfuric acid cartridges on a digital titrator (Hach).

Ions, ammonia and VFA concentrations were measured in filtered, unacidified water sample aliquots via high-pressure liquid chromatography (HP-LC). For these analyses we used an ICS-5000 + Eluent Generator (Dionex), with conductivity detection application and suppression. Analytes were separated using Dionex IonPac AS11-HC-4 µm (anions, VFAs) and IonPac CS16-4 µm (ammonium) columns (2×250 mm in size). The flow rate was 0.36 mL min−1; run time was 65 min for anions and VFAs and 17 min for ammonium. Potassium hydroxide was the eluent for inorganic anions and monovalent organic acids; methanesulfonic acid was the eluent for ammonium ion detection/quantification. A combined stock calibration standard solution featuring environmentally relevant anion ratios was used for determining concentrations and was prepared from corresponding analytical reagent grade salts. To optimize and calibrate the method for VFA analyses and determine the limits of detection, we used stock mixtures of IC grade formate, oxalate, acetate, lactate, pyruvate and butyrate standards for preparing our working saline stock solutions. Detection limits were better than 60 ppb for lactate and oxalate and 200 ppb for pyruvate, formate and acetate. Recoveries, based on standards, exceed 80 % for all analytes reported. The ion concentration measurements have an error (2σ) <20 % based on replicate analyses.

3.1.6 Dissolved (in)organic carbon and methane

Aliquots of the lake water collected were immediately transferred from the sampler to pre-cleaned – i.e., rinsed three times with ddH2O and oven-dried at 550 ∘C – 12 mL glass exetainer septum-capped vials (Labco), pre-filled with He(g) and 1 mL NaCl oversaturated solution (40 %) for CH4 or 1 mL 85 % phosphoric acid for ΣCO2. On board, the vials were filled with ∼ 11 mL water samples using a syringe connected to 15 cm PES tube that was introduced from below into the sampler to prevent diffusion of atmospheric gases into the exetainer vials.

A dissolved inorganic carbon (ΣCO2) concentration profile was produced using a peak area calibration curve obtained on a MAT253 Plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IR-MS; Thermo Scientific). The same instrument was used for determining isotope ratios of ΣCO2 (δ13C, δ18O) and methane (δ13C) and for a rough estimation of the CH4 concentrations at the monimolimnion. In brief, CO2 (or CH4) is purged from the headspace of the exetainer vials and then the gas passes through a Nafion water trap and into a sample loop PoraPLOT-Q column (0.32 mm i.d.) cooled in liquid N2; with He as the carrier gas. The sample gases are then separated via a Carboxen PLOT 1010 (0.53 mm i.d.; Supelco) held at 90 ∘C with a flow rate of 2.2 mL min−1 and transferred via a ConFlo IV interface to the instrument. For methane, prior to transfer to the IR-MS, the sample is transferred via a multi-channel device to a nickel oxide conversion reactor tube with copper oxide as a catalyst (1000 ∘C). The δ13C values obtained relative to CO2 working gas are then corrected for linearity and normalized to laboratory working standards calibrated against CO2 evolved from the international standard IAEA-603.

The concentration measurements have an error (1σ) < 4 % for ΣCO2 and <25 % for CH4. Isotope data are expressed in delta notation: , where R is the mole ratio of or and is reported in units per mil (‰). The δ13C data are reported vs. the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (V-PDB) standard. The δ18O data are reported vs. the international Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (V-SMOW) standard. The reproducibility of the δ13CDIC and δ13C measurements was better than ±0.05 ‰ and ±0.3 ‰ (1σ), respectively, based on replicates for reported values of the standard materials and the samples. Reproducibility of δ18O measurements was better than 0.4 ‰. DOC was analyzed in untreated samples by catalytic combustion at 680 ∘C (Shimadzu 5000A) with a detection limit of ∼ 0.05 mg L−1.

3.1.7 Dissolved sulfur analyses

For measuring dissolved acid-volatile sulfur (AVS) in the monimolimnion (i.e., HS−, intermediate sulfur species, H2S and the aqueous FeS clusters; Rickard and Morse, 2005), 500 mL aliquots of water samples collected at the 52–54 m depth interval were transferred to PET sample bottles pre-filled with 2 mL of 1 M Zn acetate and then 50 mL of 5 M NaOH was added. The combined concentrations of AVS bound into the ZnS precipitates were spectrophotometrically determined in an acidified solution of phenylenediamine and ferric chloride by using a Specord 210 UV/Vis (Analytik). The detection limit of the method is ≥ 0.25 µM.

As for cation analyses, 1 L aliquots of the filtered water samples were intended for sulfate S and O isotope analyses. These samples were acidified to a pH ∼ 3 with 6 N reagent grade HCl. Also, to oxidize and degas dissolved organic matter, we added 6 mL of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) 6 % and heated the samples (90 ∘C) until clear (i.e., 1 to 3 h). Dissolved sulfate was then precipitated as purified baryte (BaSO4) by using a saturated BaCl2 solution. Accordingly, after heating, ∼ 5 mL of 10 % BaCl2 was added to the water samples that were then allowed to cool down overnight. An additional 1 mL of BaCl2 solution was added the next day to ensure that all possible BaSO4 precipitated. The precipitates were then collected on pre-weighed membrane filters, rinsed thoroughly using deionized water, stored in plastic petri dishes and dried in a desiccator using a sulfate-free desiccant; the dry BaSO4 powder was scraped into clean vials; weighted; and stored until shipped to the Biogéosciences Laboratory, Dijon, France, for isotope analysis.

Each purified BaSO4 sample was analyzed for δ34S and δ18O. Samples were measured on a vario PYRO cube elemental analyzer (Elementar) in line with a 100 IR-MS (IsoPrime) in continuous-flow mode. The SO isotope data are expressed in the delta notation: , where R is the mole ratio reported in units per mil (‰) vs. the Vienna Canyon Diablo Troilite (V-CDT) and V-SMOW standards for and , respectively. Analytical errors are better than ±0.4 ‰ (2σ) based on replicate analyses of the international baryte standard NBS-127, which was used for data correction via standard–sample–standard bracketing. International standards IAEA-S-1, IAEA-S-2 and IAEA-S-3 were used for calibration with a cumulative reproducibility better than 0.3 ‰ (1σ).

3.2 Sediment samples

We also sampled the upper anoxic sediment column to a depth of ∼ 8 cm. The mineralogy of these fine-grained sediments (silt to clay in size) was qualitatively and semi-quantitatively assessed via X-ray diffraction (XRD). The δ34S and δ18O of gypsum (CaSO4 • 2H2O), δ13C of siderite (FeCO3), and δ34S isotope values of pyrite (FeS2) from these sediments were also measured and reported as described above using the delta notation: , where R is the mole ratio. Scanning electron microscopy aided by electron dispersive spectrometry (SEM-EDS) was used for textural analyses focused on the S- and/or Fe-bearing phases. In addition, a sequential extraction scheme (after Poulton et al., 2004; Goldberg et al., 2012) was conducted to characterize the sedimentary partitioning of reactive Fe and Mn fractions. Details on these analyses follow.

3.3 Sampling

Replicate sediment cores (∼ 16 cm in length) were collected with a messenger-activated gravity corer attached to 20 cm long polycarbonate tubes (5 cm in diameter). The cores were immediately sealed upon retrieval with butyl rubber stoppers, preserving about 3 cm of anoxic lake water. The head water showed no signs of oxidation (i.e., no reddish hue observed) upon transport – within about 6 h of collection – to the lab. The sediment pile was extruded and sectioned at 2 cm intervals. Surfaces of the silty clayey sediment in contact with the core liner were scrapped to remove potential contamination from the lake water and to minimize smearing effects. The sediment subsamples were rapidly frozen using liquid N2 and then stored at −18 ∘C until freeze-dried. We interrogated the upper part of the sediment pile to a depth of 8 cm (i.e., two replicate samples per depth, two cores).

3.3.1 Mineralogy

The mineralogy of the sediment was determined, semi-quantitatively, via X-ray diffraction (XRD). Powder XRD data were collected on a D8 Advance powder diffractometer (Bruker) with a LYNXEYE XE detector, under a Bragg–Brentano geometry and Cu K1 radiation (λ=1.5405 Å). Collection in the 2Θ range 4–80∘ was performed using 0.015∘ step-size increments and 0.8 s collection time per step size. Qualitative phase analyses were performed by comparison with diffraction patterns from the PDF-2 database. A semi-quantitative phase analysis was performed by the Rietveld refinement method (Post and Bish, 1989), as implemented in the computer code TOPAS 5 (Bruker). The crystal structures of the mineral phases used for refinement were obtained from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). During Rietveld refinement, only the scale factors, unit-cell parameters and size of coherent diffracting domains were refined. A correction for preferred orientation was applied for selected mineral phases (i.e., K-feldspar, mica, gypsum).

The abundance of sedimentary Fe- and Mn-bearing phases was established by applying a sequential extraction scheme aiming to quantify the contribution of the operationally defined reactive pool capable of reacting after reductive dissolution with sulfide (after Poulton and Canfield, 2005). A wet chemical extraction scheme was applied to liberate (i) the fraction of total acid-volatile sulfur (AVS) in the sediment, which might consist of mackinawite, a portion of greigite, and a (usually) unknown yet typically negligible fraction of pyrite (Rickard and Morse, 2005), and (ii) chromium-reducible sulfur (CRS), consisting primarily in pyrite but also in the sediment intermediate sulfur compounds (Canfield et al., 1986). AVS was extracted with cold concentrated HCl for 2 h. Then, the resulting hydrogen sulfide concentration (i.e., between 0.004 wt % and 0.036 wt %) was precipitated as Ag2S by using a 0.3 M AgNO3 solution. Subsequently, CRS was liberated using a hot and acidic 1.0 M CrCl2 solution (Canfield et al., 1986). The resulting H2S was trapped as Ag2S. Mass balance after gravimetric quantification was used to calculate the amount of AVS and CRS. Concentration analyses of Fe and Mn dissolved in each of these extracts were conducted via ICP-MS measurements (XSERIES II, Thermo Scientific) at the Department of Environmental Geosciences, Czech University of Life Sciences, Prague.

3.3.2 Sedimentary geochemistry and stable S, O and C isotope analyses

Aliquots of the sediment samples were analyzed for total S (Stot) concentration using a CS analyzer (Eltra GmbH). The detection limit was 0.01 wt % for Stot. The relative errors using the reference material (CRM 7001) was ±2 % for Stot.

Total S for δ34S determination was extracted in the form of BaSO4 from the sediments. To evaluate the S and sulfate-O isotope ratios of gypsum (δ34Sgy), first the heavy mineral fraction of the samples, which includes pyrite, was excluded by using 1,1,2,2-tetrabromoethane (ρ=2.95). The gypsum was then dissolved in ddH2O to extract sulfate. The free sulfate obtained was precipitated as BaSO4 as described above (Sect. 3.1.7). The BaSO4 was then converted to SO2 by direct decomposition mixed with V2O5 and SiO2 powder and combusted at 1000 ∘C under vacuum (10−2–10−3 mbar); mass spectroscopic measurements of the evolved SO2 were conducted on a Finnigan MAT 251 IR-MS dedicated to S isotope determinations. The results are expressed in delta notation and reported against the V-CDT and V-SMOW standards. The accuracy of the measurements was determined via international standards, with reproducibility better than 0.2 ‰.

The IR-MS instrument used to evaluate the isotope ratios of dissolved sulfate was also used for determining the δ34S of pyrite in the upper anoxic sediments. Prior to analyses, an AVS/CRS wet chemical extraction scheme similar to the one described above was applied. After centrifugation, the Ag2S precipitate was washed several times with ddH2O and oven-dried at 50 ∘C for 48 h. The pyrite δ34S measurements were performed on SO2 molecules via combustion of ∼ 500 mg of silver sulfide homogeneously mixed with an equal amount of WO3 using a vario PYRO cube (Elementar) connected online via an open split device to the IR-MS. International standards (IAEA-S-1, IAEA-S-2, IAEA-S-3) were used for calibration. Isotope results are reported in the delta notation against the V-CDT standard. Analytical reproducibility was better than 0.5 ‰ based on replicates for standard materials and samples.

The isotope ratios of carbonate in the sediment fraction were evaluated – after removal of organic carbon with H2O2 – by implementing the method described by Rosenbaum and Sheppard (1986). These were measured using a DELTA V mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled with an EA-1108 elemental analyzer (Fisons). The same instrument was used for measuring the sediment δ13Corg. For this purpose, the samples where finely milled, place in tin (Sn) capsules and oxidized to CO2 at 1040 ∘C in the elemental analyzer. The reproducibility of the isotope measurements for organic C was better than ±0.12 ‰ and better than ±0.1 ‰ for both carbon and oxygen isotopes of siderite. For siderite, the accuracy of the measurement was monitored by analyses of the IAEA NBS-18 (δ13C = −5.014 ‰; δ18O = −23.2 ‰) and two in-house standards; the long-term reproducibility is better than 0.05 ‰ for δ13C and 0.1 ‰ for δ18O.

3.3.3 Textural features

For SEM of the sediments, we used a MIRA3 GMU scanning electron microscope (Tescan) combined with a NordlysNano electron backscattering diffraction (EBSD) system for semi-quantitative chemical petrography and a Magellan 400 (FEI) for higher-resolution imaging in secondary electron mode.

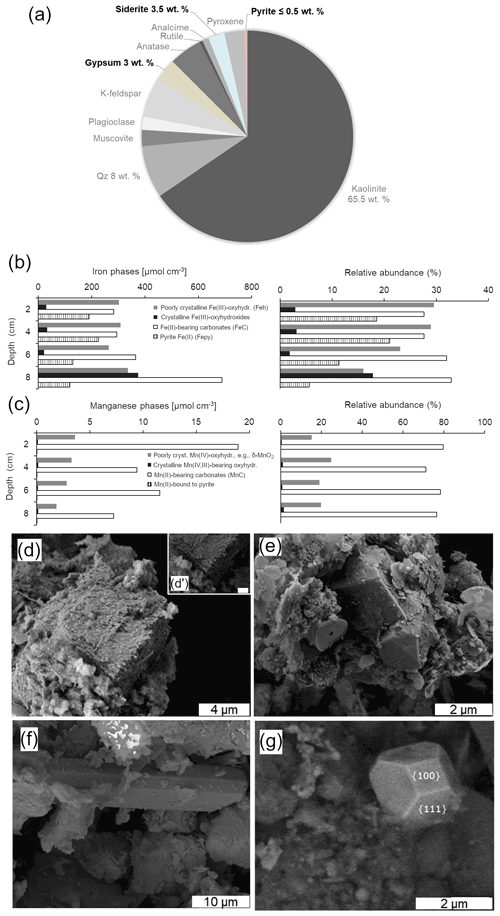

4.1 Bottom water column stratification and dissolved oxygen levels

Physicochemical parameters measured in the dysoxic to anoxic waters at the time of sampling are shown in Fig. 2a. Profiling of these parameters was consistent with several previous and subsequent probe monitoring measurements in the meromictic post-mining lake (e.g., Petrash et al., 2018). The pH in the hypolimnion was ∼8.2 and decreased moderately downwards, reaching 7.4±0.2 units near the anoxic SWI. Simultaneous reactions involving dissolution, anoxic re-oxidation and (re)precipitation of reactive minerals could be responsible for this moderate pH decrease (see Soetaert et al., 2007). These reactions are considered in subsequent sections of this work.

Conductivity exhibited a steep gradient at ca. 48 m depth that flattens with increasing depth. Temperature increased gradually towards the bottom. The zone in the water column where these gradients concur is referred to as the hypolimnion. Increased conductivities within the hypolimnion of post-mining lakes, such as that examined here, could result from the legacy of the former mine drainage and/or from groundwater inflow (e.g., Denimal et al., 2005; Schultze et al., 2010).

Salinity was directly derived by using the measured conductivity values (after Hambright et al., 1994). It increased 3-fold from the hypolimnion downwards (Fig. 2a). This could result from recharge of groundwater carrying high loads of dissolved salts and/or from the lack of mixing of the legacy mine-impacted pit lake waters with those now comprising the mixolimnion. The temperature gradient, on the other hand, is a consequence of limited seasonal vertical heat exchange between the density-stratified water column and the mixolimnion (Boehrer and Schultze, 2008).

Molecular oxygen (O2) from the mixolimnion cannot be replenished below the density-stratified and thermally stratified bottom waters, and O2 dropped rapidly within the 48 to 49 m depth interval of the water column from about 8.1 to ∼ 0.2 mg L−1. The deepest part of the lake is anoxic (Fig. 2a). At this level, the Eh shifts from >100 mV at the lower mixolimnion to negative values down to mV near the SWI. The dysoxic, nitrogenous zone of the water column is referred to as the hypolimnion; it contains a sharp redox boundary zone referred to as the redoxcline. Below the redoxcline lies the monimolimnion which becomes anoxic (ferruginous) towards the SWI (Fig. 2a).

The hydrochemically different monimolimnion persists in the deepest depressions of the lakebed throughout the year, although with slight variations in the monitored Eh and pH ranges that could be accompanied by minor (±1 m) shifts in the vertical position of the redoxcline. In this study, we focused on the central part of the lake as it exhibited the broadest Eh range in its bottom water column (Fig. 2a). Details on the eastern and western sampling locations are available in a descriptive study by Petrash et al. (2018). Short-lived changes in redox potential of about 150 mV in the bottom water column were recently considered by Umbría-Salinas et al. (2021). These changes have effects on water column speciation (Fig. B1, Appendix B) and affect the partitioning of several redox-sensitive metals that bind to reactive iron phases in the upper sediments (Umbría-Salinas et al., 2021, for details).

4.2 Dissolved carbon concentrations and δ13C isotope values

4.2.1 Dissolved organic carbon (DOC)

The average of measured DOC concentration in the sampled waters is 1050±500 µM. This range of values was higher than observed in the bottom waters of meromictic lakes such as Matano (<100 µM; Crowe et al., 2008) or Pavin (300±100 µM; Viollier et al., 1995). DOC is generally comprised of relatively high molecular weight organic compounds (not quantified here), such as cellular exudates from living and senescent planktonic microorganisms (e.g., algae, protists, bacteria) and their degradation products. Probably also present in solution are soluble humic substances (HSs) derived from the biological breakdown of refractory organic matter (e.g., lignite particles) in the sediment (Petrash et al., 2018). VFAs are linear short-chain aliphatic mono-carboxylate compounds produced during anaerobic degradation of the organic compounds referred to above. They serve as C sources and electron donors for planktonic microbial heterotrophy and were therefore quantified here. VFAs in the bottom waters were at nanomolar concentrations that are reflective of the general scarcity of labile organic substrates. A 6- to 10-fold increase in concentrations of acetate, oxalate and formate occurred towards the increasingly saline and O2-depleted waters. Concentrations of lactate, propionate, and butyrate could be detected at similar nanomolar magnitudes in the mixolimnion (not shown), but in the monimolimnion these VFAs were exhausted, i.e., below the LQ.

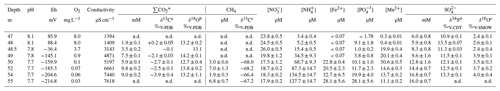

4.2.2 Total dissolved inorganic carbon

The concentrations of total dissolved inorganic carbon (i.e., ΣCO2 = H2CO3 + HCO + CO) ranged from 1.9 to 9.8 mM and increased downwards (Fig. 3a). This parameter positively correlated with alkalinity, which ranged from 1.8 to 2.9 meq L−1. Total dissolved inorganic carbon exhibited lower δ13C values at the anoxic monimolimnion, and [ΣCO2] values were inversely correlated with the δ13C values (Table 1; Fig. 3a–b). The δ13C values are in the range +0.2 to −4.1 and were inversely correlated with the dissolved sulfate concentrations [SO] too (Table 1), whilst [SO] and [ΣCO2] were directly correlated (Fig. 3b–c). From these observations, an increased ΣCO2-to-alkalinity ratio is consistent with heterotrophy exceeding gross primary production (for example from chemo- and photo-autotrophy). But admixture of the lake's monimolimnion with groundwater carrying geogenic CO2 could also alter the ΣCO2 alkalinity balance. A contribution of organically derived CO2 is evident as per δ13C data, yet it could be argued that in the monimolimnion, sulfate reduction has only a moderate impact on alkalinity generation. Although speculative, it is possible that microbial sulfate reduction (MSR) is responsible for the observed lactate depletion. Therefore, the complete (to CO2) and incomplete (to acetate) oxidation of lactate by MSR could be a factor contributing to the slight decrease in pH in the monimolimnion (see Gallagher et al., 2012).

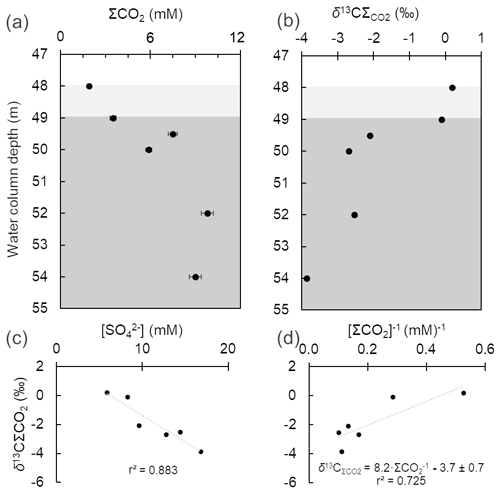

Table 1Measured concentrations and isotopic ratios in the O2-depleted bottom water column of the central sampling location (from 47 to 55 m depth below the surface), Lake Medard.

* ΣCO2 = H2CO3 + HCO + CO. a 0.05 precision of the isotopic values reported (here and for all following footnotes, based on repeated measurements of analytical standards; better than 2σ in ‰). b 0.4 precision. c 0.9 precision. d 0.1 precision. e 0.4 precision. n.d. – not determined.

Figure 3Depth-dependent variation in total dissolved inorganic carbon (ΣCO2) (a) and its δ13C (b) in the oxygen-depleted bottom water column of Lake Medard (centre). Background grey colour code as in Fig. 2. There is negative correlation (r2=0.883) between the δ13C values and dissolved SO concentrations (c). A Keeling-style plot (ΣCO2 vs. δ13C) was used to deduce the isotopic C signature of the combined CO2 flux at the sediment water interface, i.e., the intercept (d).

The CO2 source flux at the lake floor was estimated using a two-component mixing model that considers the δ13C values in sedimentary carbonates and organic matter. An input to our model is the isotope values of the sedimentary organic matter (δ13C = ‰; n=6) and those of (bi)carbonate ions derived from the dissolution of carbonate phases near the SWI and below (Table 1). For the latter, a minor contribution of ΣCO2 evolved from the oxidation of methane (mean δ13C ‰; Table 1) might also be possible and was considered. This methane diffuses throughout the anoxic sediments to the bottom water column. To account for the reactive C of the sedimentary carbonates, we used the δ13C mean values in the anoxic sediments ( ‰), which are within the range reported for carbonates in the lignite-associated lithologies (δ13C range +1.7 ‰ to +13.4 ‰; median +9.8 ‰; Šmejkal, 1978, 1984). Our sediment's δ13C mean value likely fingerprints siderite, which was the only carbonate phase detected via XRD. Yet, other relatively more soluble carbonate phases, such as dolomite and calcite, might be present in small proportions at the lake floor because they occur with siderite in the claystone sediment source. These would account for only ≤ 0.2 wt % (i.e., the LQ of our semi-quantitative XRD analyses). The range of estimated isotopic C values of the CO2 flux from the sediments to the water column is between −3.0 ‰ and −4.2 ‰ (Fig. 3d). The contributions of CO2 derived from OM degradation, carbonate mineral dissolution and any plausible methanotrophic activity thus produce isotopic C values in the lake bottom water's ΣCO2 that match those of the magmatic-derived CO2 emissions (Weinlich et al., 1999; Dupalová et al., 2012).

The mixing factor in a simple linear mixing model was calculated after Phillips and Gregg (2001). Accordingly, it could be established that dissolution of sedimentary carbonates contributes 70±5 % of the dissolved inorganic carbon, with the remaining fraction being CO2 from organic matter heterotrophy (35 % to 25 %). The influence of isotopically light CO2 derived from the oxidation of diffused methane is negligible, and any contribution of CO2 from the magmatic source cannot be estimated because of the similar isotopic values. The implication for environmental/early diagenetic interpretations of this approach is that if siderite is formed in the lake sediments, it displays a significant δ13C offset (i.e., between +9.1 ‰ and +10.9 ‰) from the values of the ΣCO2 reservoir of the lake's floor. Alternatively, siderite could rather be a redeposited mineral sourced from the Miocene claystone lithology that provided detrital material to the mine spoils and modern lake system. We will revisit siderite under Sect. 4.6.1.

4.3 Nitrogen, iron and sulfur species in water column with functional annotations on the planktonic prokaryote community

4.3.1 Nitrogen species transformations and the N-utilizing prokaryotes

Dissolved nitrate (NO) concentrations across the dysoxic hypolimnion were approximately 25 µM and decrease about 28 % towards the anoxic monimolimnion. This decrease is accompanied by an increase in ammonium from 16 µM to up to 142 µM (Table 1; Fig. 4a). Similar behaviour of reactive N species was described in other ferruginous water columns (e.g., Michiels et al., 2017; Lambrecht et al., 2018).

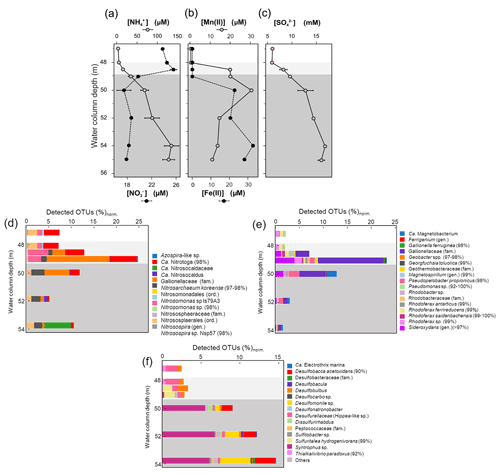

Figure 4Measured dissolved concentrations of nitrate and ammonia (a), manganous manganese and ferrous iron (b), and sulfate (c) in the bottom water column of Lake Medard (central sampling location). The right-side panels show the corresponding, normalized abundance of putative planktonic nitrogen (d), iron (e), and sulfur-utilizing (f) prokaryotes. Sequences were classified based on best BLAST (basic local alignment search tool) hit results, and bacteria/archaea were identified based on phylogenetic affiliations. Normalization was with regard to total amplicon reads in each sample. Grey background colours are based on the Eh profile (Fig. 2) and here also indicate redox-stratified niches. The sequences were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive EMBL-EBI (PRJEB47217).

The relative abundance of 16S rRNA gene sequences that can be ascribed to N-utilizing planktonic prokaryotes (Fig. 4d) indicates that Nitrosomonas-like species (95 % to 98 % gene similarity) are in the dysoxic hypolimnion at a low normalized abundance which increases at the redoxcline. Here Nitrosomonas-like species may conduct the first and rate-limiting step in nitrification, i.e., NH3 oxidation (Lehtovirta-Morley, 2018). The second nitrification step, nitrite oxidation to NO, could be exerted predominantly by species exhibiting similarity (98 % gene sequence) to Candidatus (Ca.) Nitrotoga (98 % gene sequence similarity). Ca. Nitrotoga was detected in all our samples but exhibited a higher normalized abundance (up to 9 %) at the redoxcline (Fig. 4d).

Among the relatively abundant, NH3-oxidizing microbes detected is an archaeon related to Nitrosarchaeum koreense (97 %–98 % gene similarity). This archaeon has higher normalized abundances in the ferruginous waters below the redoxcline (Fig. 4d, also Supplement 2 – Krona chart). Its distribution across the redox gradient is at odds with the fact that N. koreense has been previously suggested to be an aerobe (Jung et al., 2018). Similarly, members of the Candidatus Nitrosocaldaceae family (similarity 78 %–82 % in 387 bp) appeared to be present in the anoxic zone of the water column, despite the best-studied member of this family, Ca. Nitrosocaldus, being reported as displaying an aerobic lifestyle (de la Torre et al., 2008). The archaeal family has heterogeneous metabolic capabilities and is capable of oxidizing ammonia to nitrite (Luo et al., 2021). Our observation could make the case for niche differentiation linked to high loads of dissolved metal concentrations conferring a competitive advantage to these archaea (e.g., Gwak et al., 2019). Alternatively, the NH3-oxidizing archaea detected predominantly in the ferruginous waters possess a yet to be explored tolerance to anoxia (see Mußmann et al., 2011). For instance, Ca. Nitrosocaldus encodes a pyruvate : ferredoxin oxidoreductase that is rather uncommon among aerobic ammonia oxidizers (Daebeler et al., 2018), but it is encoded by most anaerobes able to catalyze the decarboxylation of pyruvate to form acetyl coenzyme A (Chabrière et al., 1999).

The maximal relative abundance of an Azospira-like microorganism (95 % similarity) coincides with the peak of relative abundance of members of the Gallionellaceae family at 49 to 50 m depth (Fig. 4d, Supplement 2). Like Gallionella spp., Azospira also possess dissimilatory N- and Fe-based metabolisms capable of yielding dinitrogen (N2) (Mattes et al., 2013). N2 production probably accounts for a fraction of the apparent nitrogen loss observed when the dissolved reactive NH and NO levels are compared across their counter-gradients (Table 1; Fig. 4a). Nitrite (NO), an intermediate between NO and NH, can also accumulate. Yet, concentration profiles of such an intermediate remain to be accurately resolved in the increasingly saline (high-chlorine) bottom water column of Lake Medard.

When contrasted, the counter-gradients of reactive nitrogen species and those of other dissolved bioactive chemical species suggest that while metabolizing nitrogen, the planktonic prokaryote community could also impact the cycles of Fe and S (e.g., Jewell et al., 2016, 2017; Starke et al., 2017). These cycles in the aqueous system under consideration are likely interlinked throughout microbial mediation in the generalized Reactions (R1)–(R3), but note that intermediate NO may as well act as a relevant Fe(II) oxidant in this O2-depleted system (Klueglein et al., 2014):

Reaction (R1) proceeds mixotrophically, usually requiring a favourable organic co-substrate, whereas Reactions (R2) and (R3) likely proceed under the influence of chemolithotrophic Fe(II)- and/or S-oxidizing nitrate reducers. Due to energetic considerations, these microorganisms are known for having metabolic advantages under ferruginous conditions over solely denitrifying organisms (see Robertson and Thamdrup, 2017). Reaction (R3) is known to proceed at rather low sulfide levels (Brunet and Garcia-Gil, 1996; Barnard and Russo, 2009), such as those characterizing the monimolimnion of our study site (≤0.3 µM).

In the following section, to further investigate details on the microbial ecology of the bottom ferruginous waters of Lake Medard, we consider the concentration profiles of dissolved Fe and Mn along the redoxcline. Concentrations of these dissolved metals are operationally defined as the combined ionic and colloidal fractions that passed the 0.22 µm cutoff of membrane filters. By co-evaluating the dissolved Fe and Mn concentration trends, we pursue further insight into the mechanism procuring and/or consuming these metals in the stratified water column (Davison, 1993). A 16S rRNA gene abundance profile of known iron-utilizing prokaryotes also permitted inferences about which members of the microbial community could be exerting a direct dissimilatory (catabolic) or indirect (via electron transfer) control over the concentration trends of these metals across the redox gradient.

4.3.2 Dissolved divalent manganese and iron and the Fe-utilizing prokaryotes

Dissolved manganese concentrations ([Mn]) peaked at about 50 m depth (Table 1). Below this depth, [Mn] showed a steady decrease (Fig. 4b). This trend indicates that in the water column the 50 m depth acts as a point source of Mn(II) (Davison, 1993). Divalent iron is also present at a similar concentration magnitude at this depth (Fig. 4b; Table 1), and it can readily act as a reductant of most particulate Mn(IV) settling down from the mixolimnion (Lovley and Phillips, 1988; Myers and Nealson, 1988); see Reaction (R4):

Accordingly, a substantial fraction of the Fe(II) diffusing upwards from the monimolimnion could be re-oxidized or cycled back to Fe(III) within the peak zone of Mn(IV) reduction at 50 m depth (Fig. 4b). Mn(II) yielded during iron oxidation can then be transported both upwards and downwards away from the 50 m depth source point by eddy diffusion (Fig. 4b; Davison, 1993). The internal bottom water column cycling of iron also reflects the concentration gradient of dissolved phosphate (Table 1). Solubilization of this oxyanion is thought to be regulated by reduction of its particulate Fe(III) sinks. Upward diffusion, however, allows for dissolved phosphate to be re-complexed back onto ferrihydrite-like phases that precipitate above the redoxcline, where its concentrations decrease (Table 1).

Contrary to Mn, dissolved Fe concentration ([Fe]) increased steadily downwards, and its global maximum is reached at about 54 m depth in the monimolimnion (Table 1). Immediately below this depth, [Fe] decreases by about 14 %. This decrease can be consistently observed in other anoxic zones of the lake (Petrash et al., 2018) and hints at Fe(II) and reduced S co-precipitation as metastable acid-volatile monosulfide (FeS; e.g., mackinawite). The dissimilar distribution of divalent Fe and Mn in the bottom water column (Fig. 4b) reflected reductive dissolution being much more effective for the sinking manganic particulate than for ferric particulate matter.

Our planktonic prokaryote analysis showed that above the redoxcline the relative abundance and taxonomic richness of known iron-respiring prokaryotes were low and dominated by species closely related to the β-proteobacterium Rhodoferax (99 %–100 % gene similarity) (Fig. 4e, Supplement 2). Other sequences that can be functionally affiliated to Fe(III) reduction in the dysoxic hypolimnion included a bacterium with between 92 % and 100 % gene similarity to unclassified Pseudomonas spp. (Fig. 4e). Pseudomonas could grow by coupling the oxidation of hydrogen (or nitrite) to the reduction of Fe(III) (Lovley et al., 2004). Bioutilization of manganese by Pseudomonas species – in both oxidation and reduction reactions – has also been reported (e.g., Tebo et al., 2005; Geszvain et al., 2011; Lovley, 2013; Wright et al., 2018). Other bacteria that may influence the aqueous manganese cycling to indirectly affect that of dissolved iron belong to the family Hyphomicrobiaceae (e.g., Northup et al., 2003; Spilde et al., 2005). Three OTUs with significant homology to purportedly Mn(II)-oxidizing members of the family (Hyphomicrobium hollandicum, H. sp. KC-IT-W2 and Devosia sp.) exhibited maximal relative abundances above the redoxcline but were notably absent from deeper monimolimnial waters (Supplement 2).

As previously mentioned, we detected a sharp increase in the relative number of microaerophilic Fe(II)-oxidizing Gallionella species at the redoxcline and immediately below it. They accounted for up to ∼ 24 % of the total normalized gene reads (Fig. 5b). The increase in relative abundance of Gallionella spp. coincided with an increase in sequences related to Sideroxydans spp. (Fig. 4e). These latter microaerophiles can also use Fe(II) as an energy source for chemolithotrophic growth with CO2 as the sole carbon source (Emerson and Moyer, 1997). Other different physiological groups of putative Fe(II)-oxidizing microorganisms detected above- and near-redoxcline samples including anoxygenic phototrophic and nitrate-reducing species (Magnetospirillum and Ferrigenium; Fig. 4e, Supplement 2) and Azospira-like species (Khalifa et al., 2018; Mattes et al., 2013; Dziuba et al., 2016).

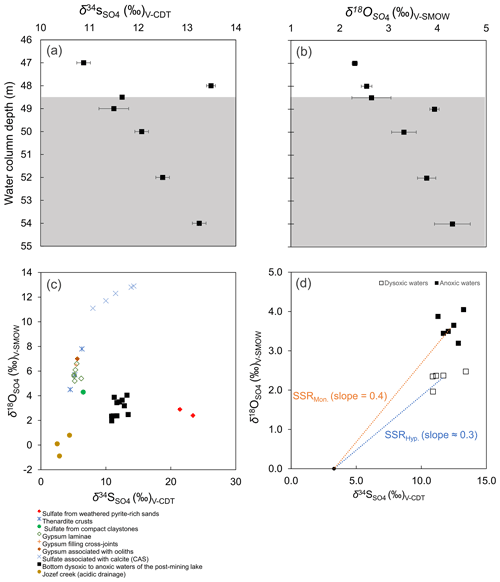

Figure 5The bottom water column δ18O and δ34S values (a–b). Grey background colour code as in Fig. 2. Also, a cross-plot of these values in the water column vs. those of all possible sources of dissolved SO to the modern lacustrine system (c). The coupled sulfur and oxygen isotope-constrained slopes of the linear regressions provide a rough estimation of the sulfate reduction rate (SRR) (d). The regressions considered the δ18O and δ34S of the acidic drainage to be the initial isotope composition of dissolved sulfate immediately after flooding (see text for details).

Prokaryotes that can adapt their metabolic strategies to the less pronounced geochemical gradients prevailing at the monimolimnion became predominant below the redoxcline. Among them is a bacterium distantly related (89 % identity in 399 bp) to Candidatus Magnetobacterium (Lin et al., 2014), whose relative abundance substantially increases at the 50 m depth (Fig. 4e). At this level, our gene sequence reads also included an OTU closely related to Georgfuchsia toluolica, a strictly anaerobic β-proteobacterium capable of degrading aromatic compounds with either Fe(III) or NO as electron acceptors (Weelink et al., 2009). HSs derived from lignite degradation contain abundant aromatic compounds (Wang et al., 2017).

Towards the SWI, important members of the Fe-respiring community were those from the family Geobacteraceae, which can use insoluble Fe(III) and/or Mn(IV) as electron acceptors and acetate, formate, alcohols, aromatics and dihydrogen (H2) as electron donors (Weber et al., 2006; Lovley and Holmes, 2022). The abundance of Geobacter species peaked around the maximum of Fe(III) reduction within the monimolimnion, at about 54 m depth. Here, acetate availability is also relatively high (Fig. 2b). The relative proportion of Geobacter spp. increased in parallel with that of their phylogenetically associated Pseudopelobacter propionicus, which is a fermentative acetogen that can only indirectly mediate Fe(III) reduction. A possible ecological interaction between P. propionicus and Geobacter species at the interface of redox boundaries in sedimentary environments has been already reported by Holmes et al. (2007) and Butler et al. (2009).

4.3.3 Dissolved sulfate and the S-utilizing prokaryotes

The dissolved sulfate concentration ([SO]) changed at the redoxcline, where it increased from 6.0 to 16.8 mM (Fig. 4c). At the lower monimolimnion, a decrease in [SO] coincided with a decrease in [Fe(II)] (Table 1; Fig. 4b–c). In the lower monimolimnion, we detected an increase in the number of taxonomic groups and relative abundances of known sulfate reducers (Fig. 4f). Their by-product sulfide, however, does not accumulate in the ambient waters ([H2S + HS−] ≤ 0.30 µM). The lack of substantial dissolved sulfide towards the SWI and the similar hydrochemical responses of both Fe(II) and [SO] could be considered circumstantial evidence for FeS precipitation, with other evidence being residual δ56Fe values that increased across the redoxcline and towards the SWI (Petrash et al., 2022). Additional insight into this and other mechanisms of sulfate turnover operating in the water column was sought by evaluating the distribution of S-utilizing prokaryotes.

Our 16S rRNA gene analyses (Fig. 4f; also Supplement 2) revealed a rather low number of taxonomic groups of sulfur-respiring bacteria at the dysoxic hypolimnion. Here OTU assignments show mostly a few uncultured members of the newly proposed order Desulfobulbales of the phylum Desulfobacterota (previously δ-proteobacteria; Waite et al., 2020; Ward et al., 2021) (Fig. 4f). Some species within Desulfobulbales require intermediate S or thiosulfate for heterotrophic growth but can also gain energy from pyruvate fermentation (Flores et al., 2012). Desulfobulbus spp. can perform dissimilatory sulfate reduction via the incomplete oxidation of lactate, but D. propionicus is known for efficiently conducting disproportionation of elemental sulfur (Lovley and Phillips, 1994). Pyruvate, as lactate, was found below our detection limits across the bottom water column, where sequences distantly related to D. propionicus (91 % similarity in 428 bp) appeared to be particularly abundant (Fig. 4f; Supplement 2). Probably important for the microbial sulfur cycling at this level of the water column is also a γ-proteobacterium from the order Chromatiales that has 92 % gene identity in 424 bp with Thioalkalivibrio paradoxus (Fig. 4f). T. paradoxus is a chemolithoautotrophic sulfur-oxidizing bacterium that can use both reduced and intermediate S compounds for C fixation (Berben et al., 2015).

There were gene sequences that could be confidently ascribed to the facultative S-utilizing autotroph Sulfuritalea hydrogenivorans (3 OTUs with ≥ 97 % identity in 424 bp) at the redoxcline. The abundance of S. hydrogenivorans increased in parallel to a decrease in the T. paradoxus-like bacterium, which suggests that the latter may be at a disadvantage and limited by organic C fixation under the specific hydrochemical conditions prevailing at the redoxcline. Such conditions may include, for instance, an abundance of aqueous intermediate S species. Under such conditions, S. hydrogenivorans can outcompete the T. paradoxus-like bacterium by oxidizing, under denitrifying conditions, thiosulfate (S2O, S0 and/or H2 for C fixation (Kojima and Fukui, 2011; Kojima et al., 2014).

At the redoxcline, the relative abundance of species distantly related to fully sequenced Desulfobulbales also increased to ∼1.7 % (Fig. 4f). Below the redoxcline, our genomic data revealed a progressive development of a more diverse sulfur-respiring bacterial population (Fig. 4f). This was dominated by many relatively rare taxa and a few abundant lineages (Supplement 2) and has a punctuated dominance of species distantly related to Desulfobacca acetoxidans (90 % identity in 432 bp). D. acetoxidans oxidizes acetate using sulfate or sulfite (SO) or S2O as electron acceptors but not S0 (Oude Elferink et al., 1999). The D. acetoxidans-like prokaryote first appeared at 49 m depth but became dominant towards the SWI, together with Desulfomonile-related species (96 % identity in 432 bp). Desulfomonile-related species could be also responsible for the previously noticed pyruvate depletion, but here they may be also thriving chemolithoautotrophically with S2O as the terminal electron acceptor (DeWeerd et al., 1990; Sun et al., 2001). Other prokaryotes probably gain energy out of intermediate S disproportionation in the anoxic monimolimnion. These may include uncultured species distantly related to Desulfatibacillum and Dissulfurirhabdus (2 OTUs with 87 % identity in 428 bp). The presence of the genus Sulfitobacter across the aqueous redox gradient and into the monimolimnion (Fig. 4f) points to continuous genetic potential for chemolithotrophic sulfur oxidation across the entire bottom water column.

4.4 δ34S and δ18O isotope values of dissolved sulfate

4.4.1 A proxy for disproportionation

Water column δ18O values ranged from +2.0 ‰ to +4.0 ‰, with corresponding δ34S values ranging between +10.9 ‰ and +13.4 ‰ (Table 1; Fig. 5a–b). The depth profiles of these isotopes in the water column reveal that dissolved sulfate in the anoxic monimolimnion is enriched in 18O (Fig. 5a–b) relative to the dysoxic waters. Despite the moderate decrease in [SO] towards the SWI (Fig. 4c), no significant sulfur isotope fractionation was registered. The δ34S values were only weakly correlated with [SO] (r2=0.16).

The ambient bottom waters had a narrow δ18O range of values: −6.1 ‰ to −6.7 ‰. This is consistent with ongoing meteoric water–rock interactions and rather limited evaporation effects (cf. Noseck et al., 2004; Pačes and Šmejkal, 2004; Dupalová et al., 2012). By applying the expression first proposed by Taylor et al. (1984a) to relate the δ18O values of dissolved SO and those of ambient waters, we deduced that the oxygen isotope effect () in our bottom waters ranged between +9.3 ‰ and +10.7 ‰. This range was calculated under the assumption that equilibrium of oxygen isotope exchange between cell-internal sulfur compounds and ambient water dominates over kinetic oxygen isotope fractionation (Fritz et al., 1989; Brunner et al., 2005). The estimated is within the range experimentally derived by Brunner et al. (2005) while using similarly 18O-depleted ambient waters. It is also within the range observed in studies of S disproportionation reactions generally proceeding under anoxic conditions (e.g., Böttcher et al., 2001, 2005). Yet, it is lower than values reported by Bottrell and Newton (2006) in biotic experiments with excess reactive Fe(III) species – i.e., +16.1 ‰ to +17.5 ‰. Therefore, our could result from the superimposition of the isotope signals of sulfate reduction, sulfide re-oxidation and intermediate sulfur disproportionation. It follows that the sulfur disproportionation in the bottom waters of Lake Medard most likely results from multiple biologically mediated reactions involving not only reactive iron but also reducible Mn stocks in the sediments (Böttcher et al., 2001). As further discussed below, the anoxic sediments contain a low – i.e., compared with Fe(III)-counterparts – yet still measurable abundance of Mn(IV) (Table 2).

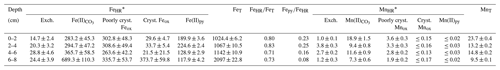

Table 2Partitioning of reactive iron and manganese species in the lacustrine sediments (0–8 cm depth).

* Sediment density is estimated at 2.71 g L−1 with a porosity of 40 %; error in the measurement (n=4) is ±16 % [Fe] and ±8 % [Mn]; in µmol cm−3.

A microbially mediated/induced sulfur disproportionation mechanism fuelled by reactive iron forms present in the sediments also involves Mn(IV)–Mn(III) reduction and is consistent with formation of FeS in the monimolimnion. This mechanism can be described by the following reactions (Reactions R5–R7, after Thamdrup et al., 1993; Böttcher and Thamdrup, 2001):

Although not shown in the rather simplified reaction set listed above, S0 may well be a different intermediate sulfur species such as S2O and/or SO (e.g., Holmkvist et al., 2011). The intracellular isotope exchange of sulfite with anoxic ambient waters has been proven to produce an oxidized SO product that is enriched in 18O relative to precursory thiosulfate and/or sulfite. This enrichment displays only a minor change, if any, in its corresponding S isotope composition (e.g., Böttcher et al., 2005; Johnston et al., 2014; Bertran et al., 2020; see Table 1). In line with this assertion, at the monimolimnion there is negligible sulfur isotope fractionation accompanying the recorded fractionation of oxygen. Yet, our data recorded a small but significant reverse sulfur isotope effect (+2.2 ‰) at the upper hypolimnion (Fig. 5a, 48 m depth). This isotope effect could be ascribed to either abiotic or biotic oxidation processes of intermediate S species occurring at that level of the water column (see Zerkle et al., 2016, their Table 1).

4.4.2 Insights into intermediate sulfur oxidation

A cross-plot of the δ34S-vs.-δ18O values along the redoxcline as well as those of all the possible geogenic sources of sulfate entering the lake system (see also Appendix B, Fig. B2) is shown in Fig. 5c. Analysis shows that the δ34S values of the redox-stratified Lake Medard fingerprint a mixed geogenic-sulfate source. Figure 5d offers further detail and linear regressions of the covariation in the δ34S-vs.-δ18O cross-plot. The slopes of such linear regressions can be used to roughly estimate sulfate reduction rates (SRRs; after Böttcher et al., 2001, and Brunner et al., 2005, among others). For assessing our SRR, it is reasonable to assume that the initial S and O isotope composition linked to dissolved sulfate was within the range of the modern nearby acidic drainage (i.e., ‰ for δ34S; 0.0±0.5 ‰ for δ18O) and similar to the initial composition of sulfate in the pit lake prior to reclamation/flooding (Fig. B2, Appendix B). The residual isotope composition would then be that of dissolved sulfate in the bottom anoxic waters.

In agreement with the lack of accumulation of sulfide in the monimolimnion, our SRR estimation is consistent with slow gross but not net SO reduction (see Böttcher et al., 2004). The SRR is apparently slower at the monimolimnion (i.e., higher slope) than in the hypolimnion. This is at odds, however, with the higher taxonomic abundance of sulfate reducers that we detected near the SWI (Fig. 4f). The decrease in dissolved sulfate concentration (Table 1) does not lower the slope of the linear regression. It means that the sulfur isotope ratio of dissolved sulfate evolves more slowly relative to the corresponding change in the oxygen isotope ratio. This result is likely due to sulfate regeneration through microbial sulfide oxidation, with oxygen isotope exchange with ambient water occurring via an intracellular oxidation step of intermediate sulfur (Böttcher et al., 2005; Bertran et al., 2020). Under the low organic substrate availability characterizing the bottom waters examined here (Fig. 2b), sulfate reducers capable of disproportionation (e.g., bacteria from the order Desulfobulbales) can maintain intracellular concentrations of sulfite. This manifested geochemically as the rapid change in water column δ18O (Böttcher et al., 2005; Antler et al., 2013).

4.5 Insights from solid-phase analyses

4.5.1 Semi-quantitative X-ray diffraction

XRD analyses of the anoxic sediments show that most detrital minerals were sourced from the Miocene claystone lithology (Appendix A). These detrital phases include kaolinite, quartz, K-feldspar, the TiO2 polymorphs rutile and anatase, and analcime (NaAlSi2O6 • H2O). Minor constituents of the anoxic lake sediments that can also be quantified include gypsum, siderite and pyrite. Gypsum and siderite were in similar abundances in the upper anoxic sediments (∼ 3 wt % to 4 wt %), whereas pyrite accounts for a maximum of 0.5 wt % of their total mineralogy (Fig. 6a). Given that the diffraction peaks of major and minor mineral sediment constituents mask those of Fe(III) and Mn(IV) oxyhydroxides, the abundances of these reactive phases were determined through a sequential extraction scheme that also targets Fe(II)- and Mn(II)-bearing carbonates.

Figure 6Representative semi-quantitative mineralogical analysis of the upper sediment (0 to 8 cm depth): the XRD data (a) show that the sediments are dominated by aluminosilicates and contain gypsum, siderite and pyrite. Results from sequential extraction of iron (b) and manganese (c) portray changes in partitioning of these metals in reactive oxyhydroxide, carbonate and sulfide solid phases with increasing sediment depth. SEM-EDS analyses of rhombohedral siderite in the (d) 0–4 and (e) 4–8 cm sediment depth intervals. This carbonate mineral displayed corroded surfaces near the SWI. The textures of microcrystalline equant gypsum (f) and truncated octahedral microcrystalline pyrite (g) are also shown (see text for details).

4.5.2 Sequential extractions of reactive iron

The relative concentrations of highly reactive Fe-bearing species (FeHR) in the upper anoxic sediment pile are displayed in Fig. 6b. The FeHR sediment pool is defined as that capable of reacting (upon reductive dissolution) with dissolved sulfide to precipitate metastable FeS, which can later be stabilized to pyrite (Canfield and Berner, 1987; Canfield, 1989). We also report here Fe(II) bound to the pyrite fraction (Fepy) and the total iron (FeT) in the sediments (Poulton and Canfield, 2005).

Our FeHR was dominated by poorly crystalline phases (Feh), such as ferrihydrite and/or lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH). These FeHR mineral fractions were followed in abundance by those of Fe(II)-bearing carbonates (FeC) (Fig. 6b; Table 2). A significant increase in the FeC is observed with increasing depth (Fig. 6b). This may be indicative of partial dissolution of some Fe(II)-bearing carbonates at the SWI or the result of soluble Fe(II)-binding reactive carbonates deeper into the sedimentary pile. To clarify this matter, we discuss the petrographic features and C isotope values of siderite in Sect. 4.6.1.

Absolute Fe(III) concentrations ascribed to Feh phases increase towards the bottom of our 8 cm depth core, but their abundance, relative to total iron, decreases downwards (Table 2). The extraction step for Feh also extracts Fe(II) bound to monosulfides (Kostka et al., 1995; Scholz and Neumann, 2007). These metastable phases yielded ≤ 0.04 wt % according to our acid-volatile sulfur (AVS) extraction. However, possible rapid oxidation of AVS particles during sampling of the sediments makes it challenging to assess their actual abundance and mineralogy (Schoonen, 2004). It thus appears that the Feh abundance at the top of the sediments (Fig. 6b) is mostly comprised of poorly crystalline oxyhydroxide.

The iron extracted from crystalline Fe(III)-bearing phases (such as goethite) increased from 2.7±0.4 % in the first 6 cm to up to 17.8 % of the FeT at the 6 to 8 cm interval (Table 2). Fe concentrations bound to pyrite (Table 2; Fig. 6b) constituted up to ∼ 21 % of the FeT in the upper sediments (i.e., ∼ 0.8 bulk wt %) and showed a general downward decreasing trend contrasting with that of crystalline Fe(III)-bearing phases. From these observations, the 0 to 6 cm depth interval is confidently considered recent anoxic lake deposition, whilst below 6 cm are sediments that were deposited in the shallow pit lake now undergoing alteration under the redox dynamics of the present-day lacustrine system.

The ratio in the 8 cm long sediment profile accounts for the extent to which the Fe pool was pyritized. The ratio is <0.35 and decreases downwards (Table 2). When considering that the corresponding ratios were consistently ≥ 0.71, the results from our sequential extraction scheme applied to iron are consistent with a persistent ferruginous but not euxinic redox state of the now anoxic sediments (Poulton and Canfield, 2011). Variability in and with depth of the sediments reflects the redox dynamics after flooding and establishment of a chemically distinct monimolimnion.

From combining results from FeHR partitioning in the sediments (Table 2) and the dissolved Mn(II) and Fe(II) concentration trends (Fig. 4b), we can now strengthen an earlier deduction that Fe(II) sourced from reductive dissolution processes in the upper sediments diffuses upwards, where it rapidly reacts with residual O2 in the vicinity of the redoxcline to form metastable Fe(III)-bearing particulate phases. Most of the iron in such amorphous to nanocrystalline ferrihydrite-like aggregates are deposited on the lake's anoxic floor. From the anoxic floor, iron is resolubilized back into the monimolimnion. Yet a fraction of it stabilizes upon burial as goethite (α-FeOOH) or is bound to the surfaces of reactive carbonates. Another fraction is pyritized through reactions involving elemental sulfur and/or polysulfide near the SWI (Fig. 6b) (Schoonen, 2004, for details). Indeed, we observed that in the upper sediment the partitioning of the reactive iron into these minerals can be swiftly altered by short-lived variations (±150 mV) in the redox potential of the bottom water column. Variations in the relative proportions of reactive iron minerals also control the distribution of siderophile redox-sensitive elements in the sediment pile (Umbría-Salinas et al., 2021).

4.5.3 Sequential extractions of reactive Mn-bearing phases

Results from our extraction scheme applied to Mn (i.e., after Slomp et al., 1997; Van Der Zee and Van Raaphorst, 2004) show that the MnHR pool in the anoxic sediment was dominated by Mn(II)-bearing carbonates (MnC) (Fig. 6c; Table 2). The carbonates were relatively more abundant at the SWI but, in contrast to FeC, showed no clearly defined concentration trend in the upper sediments (Table 2; Fig. 6b–c). A declining trend downwards is clear for the proportions of easily reducible Mn(IV) bound to poorly crystalline phases, such as δ-MnO2. These were extracted by diluted HCl (Fig. 6c; Table 2) (Slomp et al., 1997). Reducible Mn associated with more crystalline oxyhydroxide forms is extracted by dithionite (Canfield et al., 1993), but concentrations of this fraction might be sourced from crystalline Fe(III) oxyhydroxides that can either sorb Mn(II) or structurally incorporate Mn(III) (Namgung et al., 2020). Irrespective of its source, the highly crystalline Mn-bearing fraction in our sediment comprises ≤ 0.2 wt % of MnT (Table 2). The concentrations of Mn(II) bound to sulfides accounted for ≤ 0.03 wt % of the total Mn extracted (Fig. 6c; Table 2). From the analyses of the partitioning of reactive Mn species, we can thus confirm that under the anoxic conditions currently prevailing in the bottom waters and anoxic SWI of Lake Medard, a minor, yet still important, fraction of reducible MnHR can be exported from the water column and can participate, together with the reactive forms of iron, in the internal cycle of S (e.g., Reaction R7).

4.6 Insights from siderite, gypsum and pyrite analyses

4.6.1 Siderite

Siderite accounts for up to 3.5 wt % of the total mineralogy of the anoxic lacustrine sediment where it occurs as dispersed fine crystalline rhombohedra. Siderite displays corroded surfaces towards the SWI. This textural feature cannot be observed in crystals at the 4 to 8 cm depth interval (Fig. 6d–e). This is consistent with results from the sequential iron extraction scheme (see above) indicative of Fe carbonate likely undergoing recrystallization and/or growth in the deeper part of the examined sediment pile but partial dissolution towards the SWI, despite its low supersaturation in the monimolimnion (; Supplement 1).

The siderite is enriched in 13C by around +9 ‰ (mean δ13C value of siderite is ‰) relative to ΣCO2 of the bottom water column (Table 1). The mean δ13C value of the mineral is, however, within the range of δ13C isotope values reported by Šmejkal (1978) for carbonates of the Cypris claystone. Also, the mean δ18O values ( ‰) of siderite are within the range observed in Miocene claystone carbonates, which are comprised also of dolomite and calcite (Šmejkal, 1978, 1984). From combining the average isotopic values and textural features of siderite in our anoxic sediments, the mineral can then be considered a seeded (detrital) phase also sourced from the claystone. Siderite seeds were probably redeposited first in the mine spoils and then in the floor of the post-mining lake, together with aluminosilicates and other major and minor mineral phases, during the lake's flooding stage (2008–2016) or thereafter.

4.6.2 Gypsum

Gypsum has a relative abundance of ca. 3 wt %. It displays a microcrystalline {010}-dominated platy shape (Fig. 6f). This is an equilibrium morphology corresponding to a rather low supersaturation (e.g., Simon et al., 1965; van der Voort and Hartman, 1991; Massaro et al., 2010; Rodríguez-Ruiz et al., 2011). This soluble mineral is not thermodynamically predicted by the aqueous-mineral equilibrium modelling of the monimolimnion water (i.e., ; Supplement 1). However, a low-saturation state () that would allow for gypsum formation must exist in the upper sediment pore spaces, for instance, where Ca2+ ion activities are locally increased by carbonate dissolution.

Gypsum precipitation under low-saturation states can probably occur as the result of short-lived, climatically constrained changes in the precipitation–dissolution environment of the upper sediment pile (see Umbria-Salinas et al., 2021). The isotope values of the sulfate moiety in the authigenic gypsum (δ34Sgy and δ18Ogy) provide further insight into the significance of this phase within the internal sulfur cycle and early diagenetic context of the system under consideration. The δ34Sgy isotope values ranged from −13.9 ‰ to −9.6 ‰. Accordingly, gypsum shows 34S depletion of −17.8 ‰ to −11.6 ‰ relative to dissolved SO in the ambient anoxic waters (Table 1). The δ18Ogy values range from +5.1 ‰ to +6.3 ‰ (V-SMOW). In consequence, the sulfate in gypsum is 18O-enriched by +1.4 ‰ to +2.6 ‰ as compared with the mean δ18O of the monimolimnion (Table 1). This magnitude of isotope 18O enrichment of gypsum sulfate appears consistent with the range observed when sulfate is derived from pyrite that is oxidized by ferric iron in aqueous anaerobic experiments (e.g., Taylor et al., 1984b; Toran and Harris, 1989; Balci et al., 2007).