the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Effects of intensified freeze-thaw frequency on dynamics of winter nitrogen resources in temperate grasslands

Chaoxue Zhang

Na Li

Chunyue Yao

Jinan Gao

Linna Ma

In seasonal snow-covered temperate regions, winter serves as a crucial phase for nitrogen (N) accumulation, yet how intensified freeze-thaw cycles (FTC) influence the fate of winter-derived N remains poorly understood. We simulated intensified FTC regimes (increased 0, 6, and 12 cycles) in situ across two contrasting temperate grasslands, employing dual-labeled isotopes (15NH415NO3) to trace the dynamics of winter N sources. Our results showed that soil microbes exhibited a strategic adaptation to FTC stress characterized by C-N decoupling: despite a decline in microbial biomass C, they maintained or even increased biomass N. Intensified FTC did not cause ecosystem-level losses of winter N sources, primarily because the soil and microbes functioned as a crucial N reservoir during the vulnerable early spring period. The convergence in ecosystem-level 15N retention emerged through distinct compensatory pathways: while the meadow steppe exhibited higher N mineralization potential, the sandy steppe achieved functionally equivalent retention through more efficient plant 15N uptake, comparable microbial 15N immobilization, and similarly constrained 15N leaching. While HFTC reduced community-level plant 15N acquisition, it amplified competitive asymmetry among plant functional types: dominant cold-adapted species (early spring phenology and deeper roots) increased 15N uptake, while subordinate species (later-active, shallow-rooted species) exhibited reduced 15N acquisition. These findings reveal that winter climate change restructures grassland N cycling primarily through biological mechanisms, microbial resilience and trait-mediated plant competition, rather than promoting N losses. Future climate models must incorporate these plant-microbe-soil interactions to accurately predict ecosystem trajectories under changing winter conditions.

- Article

(6604 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(389 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Approximately 50 % of terrestrial ecosystems in the Northern Hemisphere experience seasonal snow cover and winter soil freezing (Sommerfeld et al., 1993; IPCC, 2021). Remarkably, soil microbes maintain metabolic activity under snowpack and contribute to nutrient mineralization throughout winter (Larsen et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2011). These winter processes, including soil nitrogen (N) mineralization and microbial N immobilization, constitute a vital nutrient reservoir that supports plant growth across alpine grasslands, temperate grasslands, and boreal forests (Alatalo et al., 2014; Collins et al., 2017; Edwards and Jefferies, 2010). The springtime release of winter-derived N (mainly including NH, NO, and dissolved organic N) through freeze-thaw cycles (FTC) synchronizes nutrient availability with plant demand (Kaiser et al., 2011), particularly in N-limited ecosystems where winter N contributions may determine growing season productivity (Schmidt and Lipson, 2004).

Climate warming has emerged as one of the most important global environmental challenges. Evidence shows that climate warming has primarily occurred during winter, with the rate of winter warming exceeding the annual average over the past few decades in China (Zong and Shi, 2020). This trend is expected to intensify, with an anticipated increase in the frequency of extreme warming events (IPCC, 2021). Winter warming is projected to alter multiple aspects of freeze-thaw dynamics, including the intensity, frequency, and duration of freeze-thaw cycles (FTC), as well as the timing of their onset in temperate regions (Gao et al., 2018; Rooney and Possinger, 2024). Among these changes, the elongation of the FTC period, resulting from a delayed and less stable soil freeze-up in autumn combined with an earlier spring thaw, is a critical outcome (Henry, 2008). This elongation extends the duration of the transitional period when soil temperatures fluctuate around 0 °C, while an increase in FTC frequency intensifies the recurrence of such fluctuations within a given season. Together, these changes substantially increase the window and intensity of physical and biological disturbances to ecosystem processes. Consequently, this could affect the availability of winter N sources for plant growth. However, how intensified FTC regime affects winter N retention remains poorly understood, particularly its subsequent impacts on plant N uptake and ecosystem functioning.

Intensified FTC induces complex shifts in soil N dynamics by simultaneously enhancing N mineralization while disrupting microbial immobilization and ecosystem retention processes. Existing research has demonstrated that intensified FTC can enhance soil N availability in cold regions (Dai et al., 2020; Nie et al., 2024; Teepe and Ludwig, 2004). The physical disruption caused by FTC promotes the N release from both soil organic matter and microbial biomass via cell lysis (Koponen et al., 2006; Sawicka et al., 2010; Skogland et al., 1988). However, this FTC-induced N pulse often occurs before plants resume active uptake, leading to substantial N losses through leaching and gaseous emissions (Chen et al., 2021; Elrys et al., 2021; Ji et al., 2024). While microbial mortality reduces microbial N immobilization (Gao et al., 2018), the surviving microbial community exhibits stimulated microbial activity that accelerates nutrient cycling (Fitzhugh et al., 2001; Nie et al., 2024; Sharma et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2024). Notably, a comprehensive meta-analysis by Song et al. (2017) indicated that FTC have no significant effect on microbial biomass N (MBN) across various ecosystems, including forest, shrubland, grassland/meadow, cropland, tundra and wetland ecosystems, which suggests complex compensatory mechanisms in microbial N retention.

Frequent FTC significantly impact plant-soil N dynamics through multiple pathways.

Root damage caused by FTC directly impairs plant N acquisition capacity (Campbell et al., 2014; Song et al., 2017), while simultaneously creating temporal mismatches in N availability. Using 15N tracer, Larsen et al. (2012) demonstrated that soil microbes initially dominate N immobilization following snowmelt, with plant functional types exhibiting sequential N uptake patterns: evergreen dwarf shrubs are the first to take up winter N, succeeded by deciduous dwarf shrubs and graminoids in late spring in the alpine ecosystem. This study highlighted a temporal differentiation in the resumption of N uptake among plant functional groups after winter. This temporal niche partitioning is particularly pronounced in temperate regions, where shallower snowpack and more frequent spring FTC result in distinct competitive environments compared to alpine systems. Studies in temperate grasslands have shown that perennial bunch grasses exhibit earlier N uptake than perennial rhizome grasses and forbs (Ma et al., 2018, 2020), a phenological advantage that becomes more pronounced under winter warming conditions (Turner and Henry, 2009). These findings highlight how FTC-mediated changes in belowground processes interact with plant functional traits to govern winter N partitioning.

While previous studies have examined winter N cycling in high-altitude and high-latitude regions experiencing rapid warming trends (Alatalo et al., 2014; Brooks et al., 1996; Edwards and Jefferies, 2010), temperate grasslands, characterized by distinct freeze-thaw regimes, have received little attention. Critically, existing research has predominantly relied on laboratory simulations employing artificial freeze-thaw regimes (DeLuca et al., 1992; Teepe and Ludwig, 2004), creating significant gaps regarding the ecological impacts of natural in situ freeze-thaw cycles. Field-based investigations are urgently needed to address two critical questions: (1) how FTC frequency alters retention dynamics of winter N sources, and (2) whether these changes create legacy effects on subsequent growing season productivity and plant community composition in temperate grasslands.

Temperate grasslands cover nearly 40 % of China's terrestrial ecosystems (Bardgett et al., 2021) and are particularly vulnerable to climate change due to their prolonged near-freezing winter conditions. To quantify how intensified FTC affect the retention of winter N resources in this vulnerable system, we conducted an in situ 15NH415NO3 tracer experiment in two contrasting temperate grasslands. We hypothesize that: (1) Intensified FTC would increase ecosystem-level losses of winter-derived N in temperate grasslands. Furthermore, the sandy steppe would experience greater N loss than the meadow steppe due to its inferior edaphic and vegetation conditions (Table 1); and (2) intensified FTC would lead to differential utilization of winter N sources among plant species, mediated by interspecific variations in their competitive abilities, root system architecture, and temporal niche partitioning in growth phenology (Hosokawa et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2018, 2020). Specifically, we expected that species with earlier spring green-up and deeper root systems (e.g., dominant species) would increase 15N utilization under intensified FTC, while subordinate species with later phenology and shallower roots would show reduced 15N uptake (Table S1; Campbell et al., 2014; Song et al., 2017).

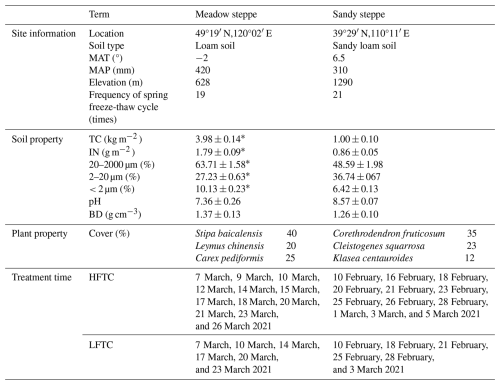

Table 1Climate, soil and plant properties (± Standard Error, n=6), and treatment time in the meadow steppe and the sandy steppe.

Significant differences between sites were identified using one-way ANOVA: * p<0.05. MAT, mean annual temperature; MAP, mean annual precipitation; TC, soil total C content; IN, soil inorganic N content; BD, soil bulk density; HFTC, increased high frequency freeze-thaw cycles (+12 times; conduct 12 additional freeze-thaw cycles); LFTC, increased low frequency freeze-thaw cycles (+6 times; conduct 6 additional freeze-thaw cycles).

2.1 Experimental site

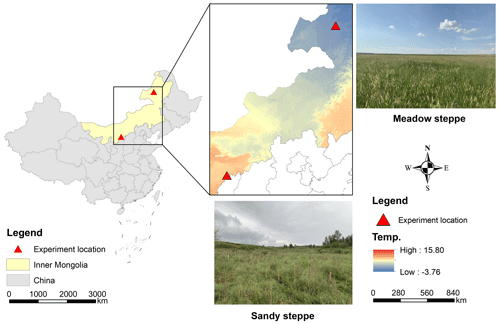

We conducted parallel experiments in two contrasting temperate grassland ecosystems: a meadow steppe and a sandy steppe (Table 1; Fig. 1). Soil bulk density, texture, pH, total C and inorganic N were determined from our own field measurements and laboratory analysis of soil samples collected during the study establishment. The meadow steppe was situated at the Hulunber Grassland Ecosystem Observation and Research Station in northeastern China (49°19′ N, 120°02′ E, 628 m), while the sandy steppe was located at the Ordos Sandy Grassland Ecology Research Station in northern China (39°29′ N, 110°11′ E, 1290 m).

Figure 1Geographical distribution of the transect in a meadow steppe and a sandy steppe in northern China.

Both sites have a continental climate. The mean annual precipitation is 420 and 310 mm, and the mean annual temperature is −2 and 6.5 °C in the meadow steppe and the sandy steppe, respectively (http://data.cma.cn/, last access: 6 January 2021; https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/maps/hourly/, last access: 6 January 2021). The non-growing season for the meadow steppe extends from late September to late April of the following year, with a spring freeze-thaw period occurring from late March to late April. In contrast, the non-growing season for the sandy steppe lasts from mid-October to late March, with the spring freeze-thaw period occurring from late February to late March. During the study period, the meadow steppe had a persistent snow cover that reached a depth of 20–25 cm in late winter (January–February). In contrast, the sandy steppe exhibited shallower and more variable snowpack (typically 10 cm depth) due to higher wind redistribution and lower moisture retention. Under natural conditions, the meadow steppe in this study experienced a total of 19 freeze-thaw cycles, while the sandy steppe experienced 21 freeze-thaw cycles in early spring (http://nm.cma.gov.cn/, last access: 6 January 2021).

The meadow steppe features high plant diversity and fertile soils, while the sandy steppe exhibits lower diversity and nutrient-poor, coarse-textured soils (Table 1). This contrast enables a comprehensive assessment of FTC impacts across varying resource availability and community structures, as evidenced by significant baseline differences in N dynamics between sites. According to the Chinese Soil Classification (GB/T 17296-2009), the predominant soil type is loam in the meadow steppe and sandy loam in the sandy steppe. The meadow steppe soil has higher C and N content but slightly lower pH compared to the sandy steppe soil (Table 1). In the meadow steppe, the dominant plant species are Stipa baicalensis Roshev (perennial bunch grass), and subordinate species are Leymus chinensis (Trin.) Tzvel (perennial rhizome grass) and Carex pediformis C. A. Mey. (perennial forb), which together cover approximately 85 % of the site. In the sandy steppe, the dominant species are

Corethrodendron fruticosum (Pall.) B. H. Choi and H. Ohashi (semi-shrub), and subordinate species are Cleistogenes squarrosa (Trin.) Keng. (perennial bunch grass), and Klasea centauroides (L.) Cass. (perennial forb), covering about 70 % of the site (Table 1). The complementary strengths of these ecosystems enable robust predictions about grassland responses to change winter climate regimes. The detail information was described in Table S1.

2.2 Experimental design

In late October 2020, eighteen 3 m × 3 m plots were established at each site, with a 3 m buffer between neighboring plots. The experiment employed a randomized block design with three treatments and six replicates per site: (1) control (ambient FTC), (2) intensified low-frequency FTC (LFTC; +6 times; conduct 6 additional freeze-thaw cycles), and (3) intensified high-frequency FTC (HFTC; +12 times; conduct 12 additional freeze-thaw cycles). These treatments were designed to simulate projected increases in winter FTC frequency under climate change scenarios.

The treatment levels were based on historical climate data showing approximately 20 natural FTC typically occur during winter and early spring at both sites (Table 1; https://data.cma.cn/, last access: 6 January 2021). According to the definition of freeze-thaw cycling, a freeze-thaw cycle is defined as the process in which soil temperature (0–10 cm) rises above 0 °C and then subsequently drops below °C (Yanai et al., 2007). Therefore, the intensified FTC correspond to total increases in 30 % (+6 times; conduct 6 additional freeze-thaw cycles) and 60 % (+12 times; conduct 12 additional freeze-thaw cycles) in the frequency of FTC during winter and spring seasons, respectively.

Within each plot, we established a fixed 1 m × 1 m subplot for 15N tracing. Building upon established 15N tracing approaches (Ma et al., 2020), we applied 15NH415NO3 solution prior to the onset of winter soil freezing. A solution containing 600 mg 15N L−1 of 15NH415NO3 was injected into 100 holes with a syringe guided by a grid frame (1 m × 1 m), with each hole receiving 2 mL of the labeled solution. The total application per subplot was 200 mL, which is equal to 120 mg 15N m−2. The added 15N was kept within the natural fluctuation range of inorganic N in the soil, approximately 7 %–10 % of background soil inorganic N levels. We injected water into control treatments instead of the 15N tracer, and there were no significant differences in plant/microbial N concentrations when compared to the 15N treatments. This indicates that the 15N application did not disrupt natural N cycling processes (Ma et al., 2018).

Based on recent 5-year climatic records, our initial FTC treatments were scheduled approximately 15 d prior to the natural spring FTC period (late winter). For the freezing-thaw manipulation, a closed-top tent (3 m length × 3 m width × 2 m height) was installed in each plot during each warming manipulation. The heating tents were constructed with polyester fabric, featuring sealed tops and mesh-sided windows to prevent excessive CO2 accumulation while maintaining temperature control. Within each tent, we used a propane air heater (Mr. Heater, USA) to raise soil temperature to 2–3 °C (0–15 cm), maintaining this temperature continuously for 8 to 10 h each time. Continuous temperature logging was performed using a temperature detector per treatment positioned at 10 cm soil depth, with data recorded at half-hour intervals throughout the experiment. The temperature was then allowed to drop to approximately −2 °C over a period of 4 h to complete one freeze-thaw cycle, the 5 cm depth was periodically verified with a handheld thermometer specifically during FTC treatments to ensure target temperature thresholds were met. Two intensified FTC regimes were implemented: (i) high-frequency FTC (HFTC) with 12 additional cycles administered every 1–6 d, and (ii) low-frequency FTC (LFTC) with 6 additional cycles every 3–8 d. During the natural freeze-thaw period, all artificial FTC treatments were deliberately conducted when daily mean temperatures remained below −2 °C to avoid interference with natural cycles.

2.3 Sampling and processing

2.3.1 Field soil and plant sampling

A comprehensive characterization of baseline soil properties and plant community was conducted in August 2020, prior to the establishment of experimental treatments. Soil samples were collected from the top 20 cm depth at 10 randomly selected points within each site. Soil pH was determined in a 1:2.5 soil : water suspension. Soil clay texture was determined by an optical size analyser (Mastersizer 2000). Soil total C was determined using an elemental analyser (Elementar analyzer Vario MAX 257 CN, Germany). Soil inorganic N was determined using a flow injection autoanalyzer (Scalar SANplus segmented flow 305 analyzer, Netherlands). Plant community cover was assessed by visual estimation using ten randomly placed 1×1 m quadrats at each site (Table 1).

Field samplings were conducted after the freeze-thaw treatments and during the succeeding growing season. In the meadow steppe, we collected the samples on the following dates: 26 March 2021 (early spring); 4 May 2021 (late spring); 23 June 2021 (early summer); 22 July 2021 (late summer); and 26 September 2021 (late autumn). Similarly, in the sandy steppe, samplings were collected on 5 March 2021 (early spring); 29 April 2021 (late spring); 21 June 2021 (early summer); 26 July 2021 (late summer); and 15 October 2021 (late autumn).

For plant materials, soil blocks (20 cm length × 20 cm width × 20 cm height) containing different plant species were carefully excavated and sectioned. Plant roots were washed with distilled water to remove surface 15N, then separated into aboveground and belowground components. All plant materials were oven-dried at 65 °C for 48 h. For soil samples, we randomly excavated three soil cores at 20 cm depth (diameter is 3.5 cm) from each plot. We combined three soil core into a composite sample, which was passed through a 2 mm sieve. Within 4 h of collection, the composite sample was separated into two portions: one was air-dried for soil analysis, and the other was stored at −20 °C for microbial analysis.

2.3.2 Soil moisture and temperature

Soil moisture and temperature at a depth of 10 cm were monitored using a HOBO H21-002 data logger (Onset Computer Corporation, USA) coupled with 10HS soil moisture sensors. The 10HS sensor estimates VWC by measuring the soil dielectric permittivity at a frequency of 70 MHz. The sensors were deployed with their factory-predefined standard calibration equation, which directly converts the measured dielectric readings into volumetric water content values (m3 m−3). The negative values occurred primarily in cold and frozen soil conditions and are a known artifact of the sensor's calibration at the extremely lower end of its measurement range. All negative VWC values have been set to 0 m3 m−3, reflecting that the liquid water content was at or below the sensor's effective detection limit. The number and magnitude of these values were negligible and did not influence the statistical outcomes or overall conclusions.

2.3.3 Soil and plant properties

Soil and plant samples (including aboveground and belowground parts) were dried, pulverized, and then sieved through 100-mesh and 80-mesh sieves, respectively. The sieved samples were analyzed for C and N content using an elemental analyzer (Elementar analyzer Vario MAX CN, Germany). Fresh soil samples were extracted with 2 M KCl at a 1:5 soil-to-solution ratio (10 g fresh soil with 50 mL KCl) by shaking for 1 h on a mechanical shaker. The extract was then filtered and used for the determination of NH and NO analysis. Soil net ammonification and nitrification rates were analyzed using the method of polyvinyl chloride plastic (PVC) core (Raison et al., 1987). A pair of PVC cores was vertically inserted into the soil to a depth of 20 cm in each plot to incubate soil without plant uptake. One core was collected as the initial (unincubated) sample to determine the concentrations of NH-N and NO-N using a flow injection autoanalyzer (Scalar SANplus segmented flow analyzer, Netherlands). The other core was incubated in situ for two weeks within capped cores. After incubation, we analyzed the NH-N and NO-N in these samples as well. Net ammonification and nitrification rates were estimated based on the changes in NH-N and NO-N levels between the incubated and initial values.

2.3.4 Soil microbial biomass

The microbial biomass C (MBC) and microbial biomass N (MBN) were assessed by the fumigation-extraction method with a total organic C analyzer (TOC multiN/C 3100, Analytik Jena, Germany; Vance et al., 1987). Fresh soil samples were first moistened to 60 % water-holding capacity and incubated in the dark at 25 °C for a week. After incubation, portions of 15 g fresh soil were weighed for both the fumigated and non-fumigated treatments. The fumigated portions were exposed to ethanol-free chloroform (CHCl3) vapor for 24 h in a vacuum desiccator. Both fumigated and non-fumigated soils were extracted with 60 mL of 0.5 M K2SO4 (a 1:4 soil-to-solution ratio based on fresh weight) by shaking for 30 min and then filtered. After filtration, the extractable concentration of organic C or N was determined by a total organic C analyzer. Simultaneously, the soil water content was determined gravimetrically by oven-drying separate 15 g fresh soil subsamples at 105 °C to constant weight. MBC and MBN were calculated by dividing the differences in extractable C and N between the fumigated and non-fumigated samples by the conversion factor of 0.45 (Ma et al., 2025).

2.3.5 15N levels in soil, plant and microbe

The 15N values of plant (2 mg) and soil (20 mg) subsamples were determined using an elemental analyzer (Vario MAX CN, Elementar, Germany) interfaced with a continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Isoprime Precision, Isoprime, USA). Soil microbial 15N was measured using alkaline persulfate oxidation, followed by a modified diffusion method (with slight heating and acid-soaked glass fiber filters as the trap), and the filters containing the absorbed N were then measured using the same EA-IRMS system (Stark and Hart, 1996; Zhou et al., 2003). Soil immobilized 15N was then calculated by subtracting microbial 15N from soil total 15N (Ma et al., 2018; Qu et al., 2025).

The 15N acquisition (% of applied 15N) in the shoot and root were calculated as: [(15NI−15Na) × biomass 15Nt] × 100, where 15NI and 15Na are the 15N concentrations (g 15N g−1 sample) in the labeled and the control samples; biomass is the shoot or root biomass at each sampling time (g m−2), and 15Nt is the amount of total added 15N tracer (g 15N m−2). The soil or microbial biomass 15N recovery (% of applied 15N) was calculated as: [(15NI−15Na) × V × BD Nt] × 100, where V represents the soil volume of the 20 cm soil profile (cm3 m−2), and BD is the bulk density (g cm−3).

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance of treatment effects was assessed by one-way ANOVA. Differences between treatments were reported as non-significant at p>0.05 or significant at p<0.05. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to analyze the influences of different FTC treatments, sampling times, and grassland types on the measured indicators. Spearman correlation analyses were used as initial screening tool to identify relationships between environmental factors and plant 15N acquisition across different treatments. Random Forest analysis was then employed as a more robust machine learning method that can handle high-dimensional data and minimize overfitting, while effectively ranking variable importance and handling collinearity among predictors. Spearman correlation coefficients between variables were calculated using the rcorr function (in the Hmisc R package). To assess the relative importance of predictors for plant 15N acquisition capacity, a random forest model was constructed using the randomForest and rfPermute packages in R. The dataset was randomly partitioned into a training set (70 %) for model development and a testing set (30 %) for model validation. All above-mentioned analyses were conducted with SPSS 21.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) and RStudio 2025.5.0 (Posit Software, Boston, MA, USA). All graphics were generated using SigmaPlot 14.0 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), Origin 2021 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA) and RStudio 2025.5.0.

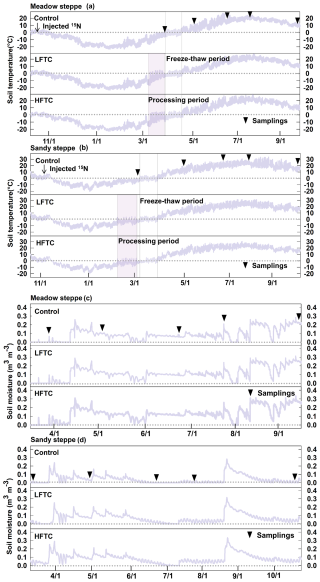

3.1 Soil microclimate

The edaphic conditions, including soil total C content, inorganic N content, and texture, exhibited significant differences between the two temperate grasslands (Table 1). Throughout the winter freezing period, the minimum soil temperatures (0–10 cm) were about −23 °C in the meadow steppe and −20 °C in the sandy steppe, respectively (Fig. 2a, b). In early spring, soil temperatures rose rapidly, accompanied by significant snowmelt. However, neither intensified LFTC nor HFTC had any significant impact on soil temperature in the subsequent growing season. In contrast, intensified low-frequency FTC (LFTC) and high-frequency FTC (HFTC) enhanced soil moisture by 0.03 and 0.05 m3 m−3, respectively, over much of the seasons (Fig. 2c, d).

Figure 2Soil temperature (a, b) and moisture (c, d) during the study period under intensified low-frequency freeze-thaw cycles (LFTC; +6 times; conduct 6 additional freeze-thaw cycles) and high-frequency freeze-thaw cycles (HFTC; +12 times; conduct 12 additional freeze-thaw cycles) treatments in a meadow steppe and a sandy steppe. Shaded vertical bars indicate processing (treatment) period. Vertical lines indicate natural freeze-thaw periods. Nablas indicate sampling times, dates for 15N tracer injection and sampling dates are also shown.

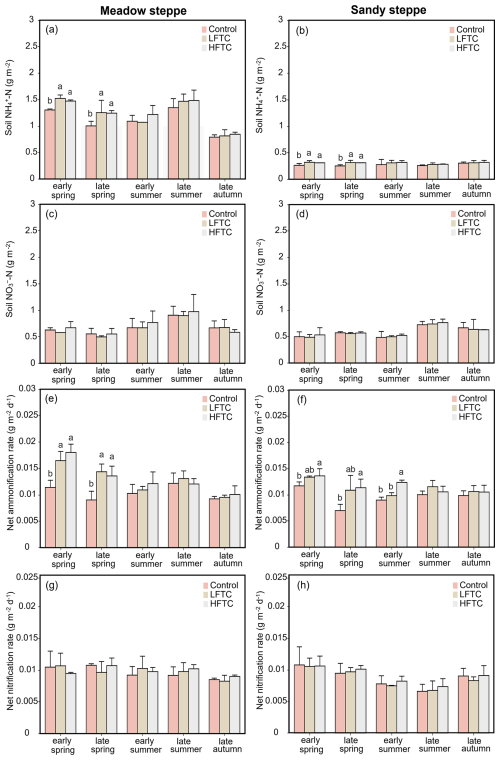

3.2 Soil properties

Intensified HFTC significantly increased soil NH-N concentrations and net ammonification rates in both grasslands during spring, with the most pronounced effects observed in the meadow steppe (Fig. 3a, b, e, f). In contrast, soil NO-N concentrations and net nitrification rates remained stable across all treatments (Fig. 3c, d, g, h).

Figure 3Soil NH-N and NO-N concentrations, net ammonification rate and net nitrification rate under intensified low-frequency freeze-thaw cycles (LFTC; 6 times) and high-frequency freeze-thaw cycles (HFTC; 12 times) treatments in the meadow steppe and the sandy steppe. In the meadow steppe, samplings were collected on 26 March (early spring), 4 May (late spring), 23 June (early summer), 22 July (late summer), and 26 September (late autumn) in 2021. In the sandy steppe, samplings were collected on 5 March (early spring), 29 April (late spring), 21 June (early summer), 26 July (late summer), and 15 October (late autumn) in 2021. Vertical bars indicate the standard error (SE) of the means (n=6). Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatment groups within sampling periods (p<0.05).

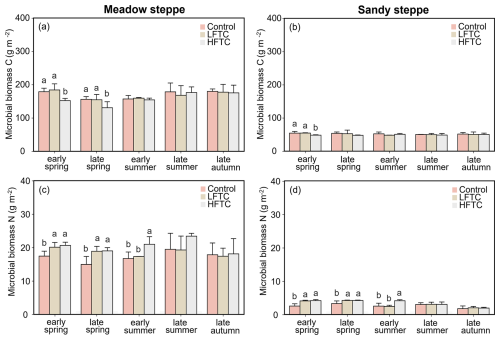

Intensified HFTC significantly decreased the soil microbial biomass C (MBC) in spring, while the effect of HFTC on microbial biomass N (MBN) persisted to summer (Fig. 4a–d). In the meadow steppe, HFTC significantly decreased MBC by 16.2 % (Fig. 4a), while LFTC and HFTC significantly increased MBN by 26.2 % and 26.9 %, respectively (Fig. 4c). In the sandy steppe, HFTC significantly decreased MBC by 11.3 % in early spring. Unlike MBC, both LFTC and HFTC significantly increased MBN by 8.5 % and 28.2 %, respectively (Fig. 4b, d).

Figure 4Soil microbial biomass C and N under intensified low-frequency freeze-thaw cycles (LFTC; 6 times) and high-frequency freeze-thaw cycles (HFTC; 12 times) treatments in the meadow steppe and the sandy steppe. In the meadow steppe, samplings were collected on 26 March (early spring), 4 May (late spring), 23 June (early summer), 22 July (late summer), and 26 September (late autumn) in 2021. In the sandy steppe, samplings were collected on 5 March (early spring), 29 April (late spring), 21 June (early summer), 26 July (late summer), and 15 October (late autumn) in 2021. Vertical bars indicate the standard error (SE) of the means (n=6). Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among sampling periods (p<0.05).

3.3 Plant properties

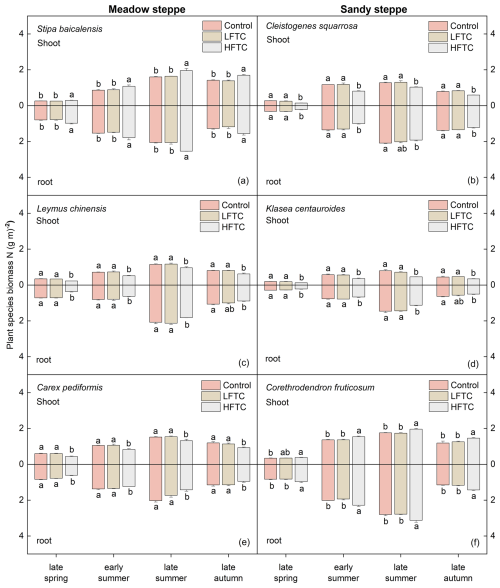

In contrast to the significant effects of HFTC, intensified LFTC had no significant impact on the shoot or root biomass N of the selected plant species at either site (Fig. 5a–f). In the meadow steppe, HFTC significantly increased shoot and root biomass N of Stipa baicalensis (perennial bunch grass) by 19.7 % and 21.8 % at the end of the growing season, respectively (Fig. 5a). In contrast, HFTC significantly reduced biomass N in the perennial rhizome grass Leymus chinensis (shoot: 23.9 %; root: 16.2 %) and the perennial forb Carex pediformis (shoot: 22.2 %; root: 18.0 %) (Fig. 5c, e). A similar differential response was observed in the sandy steppe. HFTC significantly increased biomass N in the semi-shrub Corethrodendron fruticosum (shoot: 22.6 %; root: 23.7 %) but significantly reduced it in the perennial bunch grass Cleistogenes squarrosa (shoot: −25.3 %; root: −12.1 %) and the perennial forb Klasea centauroides (shoot: −23.1 %; root: −20.3 %) (Fig. 5b, d, f).

Figure 5Plant biomass N (shoot and root) under intensified low-frequency freeze-thaw cycles (LFTC; 6 times) and high-frequency freeze-thaw cycles (HFTC; 12 times) treatments in the meadow steppe and the sandy steppe. In the meadow steppe, samplings were collected on 26 March (early spring), 4 May (late spring), 23 June (early summer), 22 July (late summer), and 26 September (late autumn) in 2021. In the sandy steppe, samplings were collected on 5 March (early spring), 29 April (late spring), 21 June (early summer), 26 July (late summer), and 15 October (late autumn) in 2021. Vertical bars indicate the SE of the means (n=6). Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among sampling periods (p<0.05).

3.4 15N Retention in the soil-microbe-plant systems

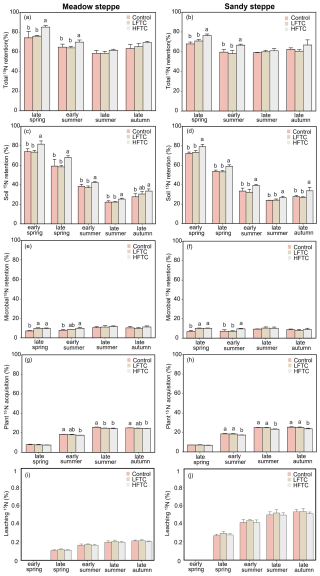

In both grassland types, soil 15N recovery peaked in early spring, followed by a rapid decline from late spring to late summer. This was then followed by a gradual increase in recovery until late autumn (Fig. 6c, d). In contrast, plant 15N acquisition increased steadily throughout the growing season in both grasslands, while microbial 15N recovery exhibited only modest fluctuations over the entire growing season (Fig. 6e–h).

During the early growing season, intensified LFTC had no significant effect on total 15N recovery in soil-microbe-plant systems, while intensified HFTC significantly increased total 15N recovery (Fig. 6a, b). LFTC did not significantly impact soil 15N recovery, but HFTC significantly increased soil 15N recovery in the two grasslands Fig. 6c, d). In the meadow steppe, intensified LFTC and HFTC significantly enhanced microbial 15N recovery by 38.0 % and 26.6 %, respectively, and by 49.5 % and 32.5 % in the sandy steppe (Fig. 6e, f). In contrast to the positive effects on microbial recovery, HFTC significantly reduced plant 15N acquisition in both grasslands. LFTC had no significant effect on plant 15N acquisition (Fig. 6g, h). The leaching 15N (deepsoil: 30–50 cm) in meadow steppe was more than that in the sandy steppe. In both grasslands, neither LFTC nor HFTC had a significant effect on the leaching 15N (Fig. 6i, j).

Figure 6Dynamics of 15N retention in soil-microbe-plant system, and leaching 15N (deepsoil, 30–50 cm) under intensified low-frequency freeze-thaw cycles (LFTC; 6 times) and high-frequency freeze-thaw cycles (HFTC; 12 times) treatments in the meadow steppe and the sandy steppe. In the meadow steppe, samplings were collected on 26 March (early spring), 4 May (late spring), 23 June (early summer), 22 July (late summer), and 26 September (late autumn) in 2021. In the sandy steppe, samplings were collected on 5 March (early spring), 29 April (late spring), 21 June (early summer), 26 July (late summer), and 15 October (late autumn) in 2021. Vertical bars indicate the SE of the means (n=6). Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among sampling periods (p<0.05).

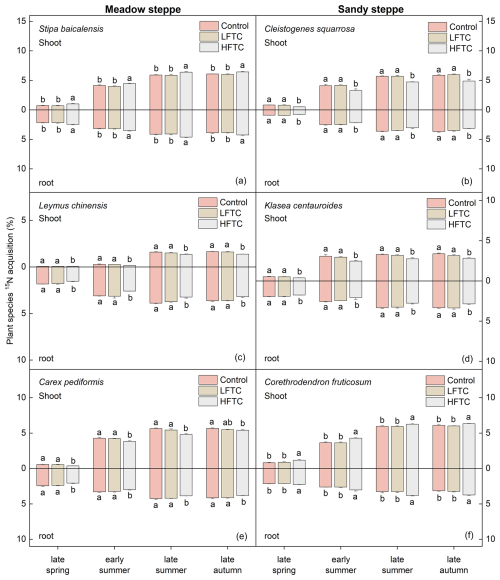

In the meadow steppe, the 15N acquisition in the shoots of S. baicalensis (perennial bunch grass) and C. pediformis (perennial forb) were comparable, while L. chinensis (perennial rhizome grass) exhibited lower 15N acquisition. In contrast, the highest 15N acquisition in roots was observed in L. chinensis, followed by C. pediformis and S. baicalensis (Fig. 7a, c, e). In the sandy steppe, both shoot and root 15N acquisition of C. fruticosum (semi-shrub) were the highest among the studied species. This was followed by the shoot 15N acquisition of C. squarrosa (perennial bunch grass) and K. centauroides (perennial forb). Notably, the root 15N acquisition of K. centauroides was higher than that of C. squarrosa (Fig. 7b, d, f).

HFTC significantly altered these acquisition patterns in a species-specific manner (Fig. 7). In the meadow steppe, HFTC significantly increased shoot and root 15N acquisition of S. baicalensis by 5.8 % and 9.3 %, respectively, but significantly decreased it in L. chinensis (shoot: 16.4 %; root: 12.1 %) and C. pediformis (shoot: 4.9 %; root: 7.8 %) (Fig. 7a, c, e). Similarly, in the sandy steppe, HFTC significantly increased 15N acquisition in C. fruticosum (shoot: 3.8 %; root: 18.4 %) but significantly reduced it in C. squarrosa (shoot: 16.7 %; root: 14.4 %) and K. centauroides (shoot: 16.1 %; root: 14.1 %) (Fig. 7b, d, f).

Figure 7Plant 15N acquisition under intensified low-frequency freeze-thaw cycles (LFTC; 6 times) and high-frequency freeze-thaw cycles (HFTC; 12 times) treatments in a meadow steppe and a sandy steppe. In the meadow steppe, samplings were collected on 26 March (early spring), 4 May (late spring), 23 June (early summer), 22 July (late summer), and 26 September (late autumn) in 2021. In the sandy steppe, samplings were collected on 5 March (early spring), 29 April (late spring), 21 June (early summer), 26 July (late summer), and 15 October (late autumn) in 2021. Vertical bars indicate the SE of the mean (n=6). Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among sampling periods (p<0.05).

3.5 Controls on plant 15N acquisition

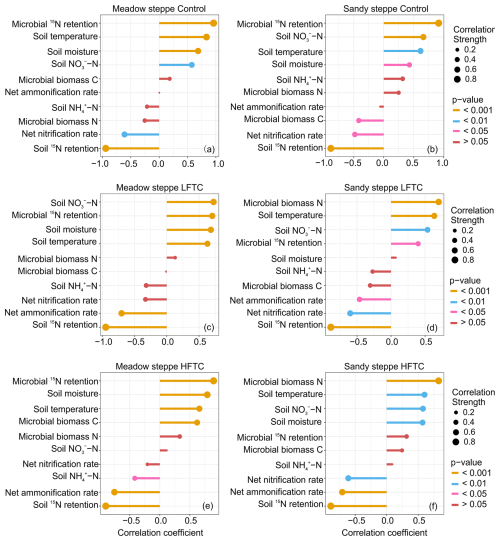

The correlation analysis revealed distinct and treatment-specific shifts in the relationships between plant 15N acquisition and environmental predictors across two grasslands (Fig. 8). In both grasslands, plant 15N acquisition exhibited the strongest positive correlation with microbial 15N retention under control treatment (Fig. 8a, b). In the meadow steppe, under both LFTC and control, microbial 15N retention, soil temperature, soil moisture and soil NO-N levels were positively correlated with plant 15N acquisition (Fig. 8a, c). Under HFTC, plant 15N acquisition also exhibited a positive correlation with MBC (Fig. 8e). In the sandy steppe, under LFTC and HFTC, plant 15N acquisition exhibited the strongest positive correlation with microbial biomass N, followed by soil temperature, and soil NO-N levels (Fig. 8d, f). Conversely, soil 15N retention, net nitrification rate, and net ammonification rate were negatively correlated (Fig. 8d, f). Under HFTC, plant 15N acquisition also exhibited a positive correlation with soil moisture (Fig. 8d).

Figure 8Relationships (Spearman correlaltion) between plant 15N acquisition and environmental predictors under control (ambient condition), intensified low freeze-thaw cycle (LFTC; 6 cycles) and high freeze-thaw cycle (HFTC; 12 times) treatments in the meadow steppe and the sandy steppe.

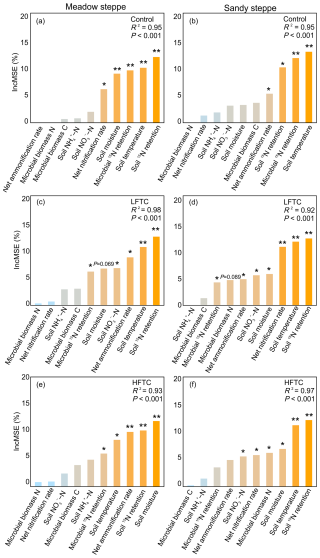

Random forest analysis revealed that soil temperature and soil 15N retention were the primary predictors of plant 15N acquisition across all treatments (Fig. 9). Notably, MBC and NH-N levels did not emerge as a significant predictor in any of the models. However, the importance of other predictors varied between grasslands and treatments. In the meadow steppe, the control, LFTC, and HFTC treatments each retained five key predictors. Dominant predictors under LFTC included net ammonification rate, soil NO-N levels and microbial 15N retention. Under HFTC, key predictors shifted to soil moisture, microbial 15N retention and net ammonification rate. Neither net nitrification rate nor MBN emerged as significant predictors under LFTC or HFTC (Fig. 9c, e). In the sandy steppe, net nitrification rate and soil moisture were key predictors under both LFTC and HFTC (Fig. 9d, f). Both LFTC and HFTC exhibited more predictors than control. Under LFTC, MBN was not a significant predictor (p=0.089), under HFTC, net ammonification rate and microbial 15N retention were also not significant predictors.

Figure 9Relative importance of environmental predictors for plant 15N acquisition as determined by random forest analysis under control (ambient condition), intensified low freeze-thaw cycle (LFTC; 6 cycles) and high freeze-thaw cycle (HFTC; 12 times) treatments in the meadow steppe and the sandy steppe.

Our in-situ 15N tracer experiment demonstrates that intensified winter freeze-thaw cycles (FTC) reshape winter N availability in temperate grasslands by stabilizing soil and microbial N retention and creating competitive hierarchies among plants, without causing losses of winter N sources.

4.1 Microbial nutrient-use strategies shift under intensified FTC

Our study reveals that intensified FTC triggers a strategic shift in soil microbial nutrient use, characterized by a notable decoupling between microbial C and N dynamics (Fig. 4). The significant reduction in MBC during the early growing season aligns with the previous observations of microbial lysis and physiological stress induced by freeze-thaw events (DeLuca et al., 1992; Walker et al., 2006). A critical finding was the stability or even increase in MBN under C-limited conditions in early spring (Fig. 4), indicating a decoupled microbial response. We propose this reflects a microbial adaptation to prioritize N retention. Faced with an inorganic N pulse from cell lysis and aggregate disruption (Fig. 3) yet constrained by C scarcity, microbes engage in luxury N immobilization. This strategy allows them to secure and store N, preventing its loss from the system (Christopher et al., 2008; Skogland et al., 1988; Wang et al., 2024). This physiological trade-off maintains ecosystem N retention at the expense of C use efficiency (Schimel and Bennett, 2004; Yu et al., 2011). Therefore, the microbial response to FTC is one of strategic re-allocation, shifting their stoichiometry to optimize N storage during a critical window of availability and instability.

4.2 Ecosystem-level retention of winter N sources under intensified FTC

Contrary to our first hypothesis, intensified FTC did not increase lead to ecosystem-level losses of the total 15N tracer in either temperate grasslands. Instead, high-frequency FTC (HFTC) significantly enhanced total 15N recovery within the soil-microbe-plant system during the early growing season (Fig. 6a, b), indicating that effective conservation mechanisms were activated. This finding challenging the prevailing paradigm that winter climate change inevitably promotes widespread N loss (Han et al., 2018; Song et al., 2017).

This observed retention capacity can be explained through three interconnected mechanisms. First, the soil pool acted as a major and persistent sink. The significantly elevated soil 15N retention under HFTC (Fig. 6) points to the efficient physical protection and chemical stabilization of the released N. This protection likely occurred through incorporation within stable soil aggregates and adsorption onto organic matter surfaces, reducing N mobility and availability for loss pathways (Bhattacharyya et al., 2019).

Second, soil microbes served as a crucial biological buffer during the critical early spring period. The significant increase in microbial 15N immobilization during early spring (Fig. 6) indicates their rapid capture of winter-derived N. Crucially, this microbial immobilization occurred when plant uptake was minimal, thereby securing the N pulse during this vulnerable window (Turner and Henry, 2009; Zheng et al., 2024). Third, FTC-induced increases in soil moisture mediated 15N availability. Our random forest analyses identified soil moisture as a significant predictor of plant 15N acquisition (Fig. 8). The elevated moisture under FTC treatments (Fig. 2b) likely enhanced N mobility, facilitating diffusion to roots. This moisture-driven promotion of N flux created favorable conditions for plant uptake, yet within the framework of effective ecosystem retention as evidenced by the absence of significant leaching losses.

While the stability of the microbial 15N pool over time indicates limited direct transfer of immobilized N to plants, its role in initial N stabilization during the vulnerable early spring period was paramount. Subsequent plant 15N uptake likely derived from other soil pools replenished by mineralization, indicating a decoupling of the typical synchrony between microbial and plant N partitioning.

4.3 Cross-site convergence in ecosystem 15N retention

Contrary to our first hypothesis, total 15N recovery was statistically similar between the two contrasting grassland ecosystems under intensified FTC conditions (Fig. 6). This convergence in ecosystem-level 15N retention can be explained by several compensatory mechanisms: First, while the meadow steppe exhibited higher net N mineralization rates in early spring, releasing a larger initial nitrogen pulse, the sandy steppe compensated through more efficient microbial and plant uptake of the N sources. This was evidenced by significantly lower soil NH-N concentrations in the sandy steppe (Fig. 4), suggesting adaptation for rapid N acquisition in this resource-limited system. Consequently, both ecosystems achieved statistically similar 15N levels in microbial and plant pools despite their divergent soil conditions (Fig. 4e–h; Table 1).

Second, hydrological pathways of winter-derived N loss were similarly constrained in both grasslands. The minimal 15N levels detected in deep soil layers (30–50 cm) (Fig. 5e, f) indicate limited leaching losses, demonstrating that intensified FTC did not disproportionately enhance N loss in the coarser-textured sandy steppe. This established a similar baseline of physical N conservation in both systems. Therefore, the similar levels of ecosystem 15N retention were not achieved through identical processes, but through different yet effective strategies in plant N uptake, physical conservation, and microbial immobilization.

4.4 Divergent plant strategies for 15N acquisition under intensified FTC

Our results strongly support the second hypothesis that intensified FTC alter species-specific acquisition of winter N sources. While HFTC significantly reduced 15N acquisition at the community-level, this overall trend concealed strongly species-level divergence (Fig. 7). This divergence was not random but was clearly aligned with key plant functional traits, particularly spring phenology and root system architecture (Table S1).

The enhanced 15N acquisition under HFTC by dominant species, S. baicalensis in the meadow steppe and H. mongolicum in the sandy steppe, exemplifies a trait-based strategy for exploiting freeze-thaw induced N pulses (Table S1). In the meadow steppe, S. baicalensis capitalized on its early spring growth and dense root morphology (Ma et al., 2018) to dominate N acquisition. The high root density provided a superior absorptive surface area in the topsoil, where FTC-mobilized N was concentrated, granting it a competitive advantage over species with coarser or less-developed root systems. In the sandy steppe, the deep-rooted legume C. fruticosum (Lonati et al., 2015) buffered against surface perturbations by accessing stable subsurface N and water. The success of these species underscores that the coupling of early phenology or deep resource access with robust root systems is a critical adaptation to FTC-induced stress, allowing them to effectively monopolize winter N resources (Miller et al., 2009).

In contrast, subordinate species (L. chinensis, C. pediformis, C. squarrosa, K. centauroides) showed significantly decreased 15N acquisition, a consequence of their phenological and architectural mismatch with the FTC-altered regime. Their later phenology likely prevented utilization of the early N pulse, while shallow, damage-susceptible root systems further constrained access to winter N sources (Table S1; Ma et al., 2018). This competitive disadvantage arose through two interconnected mechanisms. First, phenological asynchrony placed the subordinate species at a critical disadvantage. The early-season N pulse released by HFTC occurred before these later-active species had initiated substantial root activity or shoot growth (Table S1). Consequently, they missed the peak window of N pulse, which was preemptively captured by early-season competitors.

Second, structural vulnerability exacerbated their disadvantage. The fine, shallow root systems of perennial forbs, particularly C. pediformis and K. centauroides, are highly susceptible to HFTC-induced root damage (Table S1; Campbell et al., 2014; Ye et al., 2017). This vulnerability was supported by our data showing the significant reduction in root biomass N for these species (Fig. 5). Such damage not only increased fine root mortality but also further constrained their capacity to access winter-derived N (Hosokawa et al., 2017; Reinmann et al., 2019).

Ecologically, the divergent responses among plant species can be primarily attributed to a disruption of temporal niche partitioning. HFTC generate an early-season N pulse that preferentially favors species with pre-existing adaptations to cold-season conditions, such as early spring phenology and robust root systems. This initial advantage is further amplified by the greater susceptibility of later-active species to root damage, thereby intensifying competitive asymmetry and potentially driving long-term shifts in plant community structure. Despite the stability of soil and microbial N pools, the overall reduction in community-level 15N acquisition under HFTC suggests a potential decoupling between ecosystem N retention and plant N utilization. This indicates that ecosystem resilience, defined as the capacity to maintain both structure and function, may be compromised, as the ability to conserve N does not necessarily ensure unchanged patterns of plant resource acquisition.

4.5 Limitations and future work

This study provides valuable insights into ecosystem N cycling under intensified FTC, yet several limitations should be acknowledged. First, while our 15N tracer approach precisely tracked the fate of winter-derived inorganic N, it did not capture dynamics of the native soil N pool, particularly mobilization and loss pathways of unlabeled organic N. Second, the temporal resolution of our sampling, while appropriate for quantifying seasonal patterns of plant N uptake, was insufficient to capture rapid microbial N transformations and gaseous fluxes occurring within days following FTC events. Third, while sampling the 0–20 cm soil layer captured the majority (70 %–80 %) of the root systems, it may not fully represent the absolute 15N acquisition by deep-rooted species was likely underestimated. Finally, due to equipment constraints, we did not monitor photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) or precise CO2 levels within experimental tents; including these parameters in future studies would offer a more comprehensive understanding of microclimatic perturbations.

Building on these limitations, we propose two key priorities for future research: First, pinpoint the sources of newly available N during FTC. It would be valuable to differentiate the specific origins of newly available N during FTC, whether derived from microbial cell lysis, root mortality, or physical disruption of soil aggregates. Clarifying these sources is essential to accurately trace the pathways and retention mechanisms of FTC-mobilized N. Second, conduct high-frequency monitoring of greenhouse gas fluxes. Simultaneous monitoring of greenhouse gases (particularly N2O and CO2) with high temporal resolution during FTC events is crucial. This approach would help elucidate the coupling of microbial C and N cycling, especially given that FTC-induced N2O peaks often occur without corresponding CO2 increases, a phenomenon potentially related to the decoupled responses of microbial biomass C and N observed in our study. By systematically addressing these research priorities, we can significantly advance the mechanistic understanding of N cycling and ecosystem responses to winter climate change.

Our in-situ 15N tracer experiment provides integrated mechanistic insights into the fate of winter N sources under intensified high-frequency freeze-thaw cycles (FTC) in temperate grasslands. The key findings demonstrate that these ecosystems possess remarkable capacity to conserve winter-derived N, challenging the paradigm of significant N loss under winter climate change. First, intensified FTC did not lead to losses of total 15N tracer at the ecosystem level. This conservation was achieved through complementary mechanisms: efficient physical protection within the soils and rapid immobilization by microbial communities that secured N during the vulnerable early spring period. Second, the meadow and sandy steppes showed convergent ecosystem-level 15N retention under intensified FTC. This likely arose from equivalent plant 15N uptake via divergent strategies, similarly constrained 15N losses, and comparable microbial 15N immobilization. Third, intensified FTC restructured plant 15N acquisition by amplifying competitive hierarchies based on functional traits. Dominant species with early spring phenology and robust root systems enhanced their 15N uptake, while subordinate species with later phenology and shallower roots were disadvantaged.

These findings demonstrate that microbial communities buffer against N loss during FTC events, while plant functional traits mediate ecosystem responses to winter climate change. The species-specific shifts in 15N acquisition induced by high-frequency FTC are ecologically meaningful. The amplified competitive asymmetry, favoring cold-adapted dominants while suppressing subordinates, could initiate directional changes in plant community composition if sustained over years. Although immediate productivity may be sustained, the observed trade-off between ecosystem N retention and plant N utilization suggests a decline in long-term resource-use efficiency. Consequently, these N partitioning patterns serve as an early indicator of how winter climate change could compromise plant community resilience and trigger ecosystem restructuring. Integrating these critical plant-microbe-soil interactions into models is therefore essential for predicting future ecosystem trajectories.

Data will be made available on request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-23-1117-2026-supplement.

CZ: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing–original draft; NL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology; CY, JG: Data curation, Formal analysis; LM: Review and editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors thank the Hulunber Grassland Ecosystem Observation and Research Station, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and the Ordos Sandy Grassland Ecology Research Station, Chinese Academy of Sciences for help with logistics and access permission to the study site.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 32071602).

This paper was edited by Anja Rammig and reviewed by Chunwang Xiao, Paulina Englert, and Ana Meijide.

Alatalo, J. M., Jägerbrand, A. K., and Molau, U.: Climate change and climatic events: community-, functional- and species-level responses of bryophytes and lichens to constant, stepwise, and pulse experimental warming in an alpine tundra, Alp. Botany., 124, 81–91, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00035-014-0133-z, 2014.

Bardgett, R. D., Bullock, J. M., Lavorel, S., Manning, P., Schaffner, U., Ostle, N., Chomel, M., Durigan, G., Fry, E. L., Johnson, D., Lavallee, J. M., Le Provost, G., Luo, S., Png, K., Sankaran, M., Hou, X., Zhou, H., Ma, L., Ren, W., Li, X., Ding, Y., Li, Y., and Shi, H.: Combatting global grassland degradation, Nat. Rev. Earth Env., 2, 720–735, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-021-00207-2, 2021.

Bhattacharyya, R., Das, T. K., Das, S., Dey, A., Patra, A. K., Agnihotri, R., Ghosh, A., and Sharma, A. R.: Four years of conservation agriculture affects topsoil aggregate-associated 15nitrogen but not the 15nitrogen use efficiency by wheat in a semi-arid climate, Geoderma, 337, 333–340, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.09.036, 2019.

Brooks, P. D., Williams, M. W., and Schmidt, S. K.: Microbial activity under alpine snowpacks, Niwot Ridge, Colorado, Biogeochemistry, 32, 93–113, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00000354, 1996.

Campbell, J. L., Socci, A. M., and Templer, P. H.: Increased nitrogen leaching following soil freezing is due to decreased root uptake in a northern hardwood forest, Glob. Change Biol., 20, 2663–2673, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12532, 2014.

Chen, M., Zhu, X., Zhao, C., Yu, P., Abulaizi, M., and Jia, H.: Rapid microbial community evolution in initial Carex litter decomposition stages in Bayinbuluk alpine wetland during the freeze–thaw period, Ecol. Indic., 121, 107180, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107180, 2021.

Christopher, S. F., Shibata, H., Ozawa, M., Nakagawa, Y., and Mitchell, M. J.: The effect of soil freezing on N cycling: comparison of two headwater subcatchments with different vegetation and snowpack conditions in the northern Hokkaido Island of Japan, Biogeochemistry, 88, 15–30, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-008-9189-4, 2008.

Collins, S. L., Ladwig, L. M., Petrie, M. D., Jones, S. K., Mulhouse, J. M., Thibault, J. R., and Pockman, W. T.: Press-pulse interactions: effects of warming, N deposition, altered winter precipitation, and fire on desert grassland community structure and dynamics, Glob. Change Biol., 23, 1095–1108, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13493, 2017.

Dai, Z., Yu, M., Chen, H., Zhao, H., Huang, Y., Su, W., Xia, F., Chang, S. X., Brookes, P. C., Dahlgren, R. A., and Xu, J.: Elevated temperature shifts soil N cycling from microbial immobilization to enhanced mineralization, nitrification and denitrification across global terrestrial ecosystems, Glob. Change Biol., 26, 5267–5276, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15211, 2020.

DeLuca, T. H., Keeney, D. R., and McCarty, G. W.: Effect of freeze-thaw events on mineralization of soil nitrogen, Biol. Fertil. Soils, 14, 116–120, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00336260, 1992.

Edwards, K. A. and Jefferies, R. L.: Nitrogen uptake by Carex aquatilis during the winter-spring transition in a low Arctic wet meadow, J. Ecol., 98, 737–744, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2010.01675.x, 2010.

Elrys, A. S., Wang, J., Metwally, M. A. S., Cheng, Y., Zhang, J., Cai, Z., Chang, S. X., and Müller, C.: Global gross nitrification rates are dominantly driven by soil carbon-to-nitrogen stoichiometry and total nitrogen, Glob. Change Biol., 27, 6512–6524, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15883, 2021.

Fitzhugh, R. D., Driscoll, C. T., Groffman, P. M., Tierney, G. L., Fahey, T. J., and Hardy, J. P.: Effects of soil freezing disturbance on soil solution nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon chemistry in a northern hardwood ecosystem, Biogeochemistry, 56, 215–238, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013076609950, 2001.

Gao, D., Zhang, L., Liu, J., Peng, B., Fan, Z., Dai, W., Jiang, P., and Bai, E.: Responses of terrestrial nitrogen pools and dynamics to different patterns of freeze-thaw cycle: A meta-analysis, Glob. Change Biol., 24, 2377–2389, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14010, 2018.

Hosokawa, N., Isobe, K., Urakawa, R., Tateno, R., Fukuzawa, K., Watanabe, T., and Shibata, H.: Soil freeze–thaw with root litter alters N transformations during the dormant season in soils under two temperate forests in northern Japan, Soil Biol. Biochem., 114, 270–278, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.07.025, 2017.

Han, C., Gu, Y., Kong, M., Hu, L., Jia, Y., Li, F., Sun, G., and Siddique, K. H.: Responses of soil microorganisms, carbon and nitrogen to freeze–thaw cycles in diverse land-use types, Appl. Soil Ecol., 124, 211–217, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.11.012, 2018.

Henry, H. A. L.: Climate change and soil freezing dynamics: historical trends and projected changes, Clim. Change, 87, 421–434, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-007-9322-8, 2008.

IPCC: Climate Change 2021: The physical science basis. contribution of working Group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on Climate Change, Cambridge Univ. Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896, 2021.

Ji, X., Xu, Y., Liu, H., Cai, T., and Feng, F.: Response of soil microbial diversity and functionality to snow removal in a cool-temperate forest, Soil Biol. Biochem., 196, 109515, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2024.109515, 2024.

Kaiser, C., Fuchslueger, L., Koranda, M., Gorfer, M., Stange, C. F., Kitzler, B., Rasche, F., Strauss, J., Sessitsch, A., Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S., and Richter, A.: Plants control the seasonal dynamics of microbial N cycling in a beech forest soil by belowground C allocation, Ecol., 92, 1036–1051, https://doi.org/10.1890/10-1011.1, 2011.

Koponen, H. T., Jaakkola, T., Keinänen-Toivola, M. M., Kaipainen, S., Tuomainen, J., Servomaa, K., and Martikainen, P. J.: Microbial communities, biomass, and activities in soils as affected by freeze thaw cycles, Soil Biol. Biochem., 38, 1861–1871, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.12.010, 2006.

Larsen, K. S., Michelsen, A., Jonasson, S., Beier, C., and Grogan, P.: Nitrogen Uptake During Fall, Winter and Spring Differs Among Plant Functional Groups in a Subarctic Heath Ecosystem, Ecosyst., 15, 927–939, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-012-9555-x, 2012.

Lonati, M., Probo, M., Gorlier, A., and Lombardi, G.: Nitrogen fixation assessment in a legume-dominant alpine community: comparison of different reference species using the 15N isotope dilution technique, Alp. Bot., 125, 51–58, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00035-014-0143-x, 2015.

Ma, L., Liu, G., Xu, X., Xin, X., Bai, W., Zhang, L., Chen, S., and Wang, R.: Nitrogen acquisition strategies during the winter-spring transitional period are divergent at the species level yet convergent at the ecosystem level in temperate grasslands, Soil Biol. Biochem., 122, 150–159, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.04.020, 2018.

Ma, L., Zhang, C., Feng, J., Liu, G., Xu, X., Lü, Y., He, W., and Wang, R.: Retention of early-spring nitrogen in temperate grasslands: The dynamics of ammonium and nitrate nitrogen differ, Glob. Ecol. and Conserv., 24, e01335, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01335, 2020.

Ma, L., Zhang, C., Feng, J., Yao, C., and Xu, X.: Distinct roles of plant and microbial communities in ecosystem multifunctionality during grassland degradation and restoration, Geoderma, 459, 117381, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2025.117381, 2025.

Miller, A. E., Schimel, J. P., Sickman, J. O., Skeen, K., Meixner, T., and Melack, J. M.: Seasonal variation in nitrogen uptake and turnover in two high-elevation soils: mineralization responses are site-dependent, Biogeochemistry, 93, 253–270, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-009-9301-4, 2009.

Nie, S., Jia, X., Zou, Y., and Bian, J.: Effects of freeze–thaw cycles on soil nitrogen transformation in improved saline soils from an irrigated area in northeast China, Water, 16, 653, https://doi.org/10.3390/w16050653, 2024.

Qu, Y., Zhu, F., Hobbie, E. A., Wang, F., Liu, D., Huang, K., Sun, K., Hou, Z., Zhu, W., and Fang, Y.: Paired 15N labeling reveals that temperate broadleaved tree species proportionally take up more nitrate than conifers, J. Plant Ecol., 18, rtaf072, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpe/rtaf072, 2025.

Raison, R. J., Connell, M. J., and Khanna, P. K.: Methodology for studying fluxes of soil mineral-N in situ, Soil Biol. Biochem., 19, 521–530, https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(87)90094-0, 1987.

Reinmann, A. B., Susser, J. R., Demaria, E. M. C., and Templer, P. H.: Declines in northern forest tree growth following snowpack decline and soil freezing, Glob. Change Biol., 25, 420–430, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14420, 2019.

Rooney, E. C., and Possinger A. R: Climate and ecosystem factors mediate soil freeze-thaw cycles at the continental scale, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeosci., 129, e2024JG008009, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JG008009, 2024.

Sawicka, J. E., Robador, A., Hubert, C., Jørgensen, B. B., and Brüchert, V.: Effects of freeze–thaw cycles on anaerobic microbial processes in an Arctic intertidal mud flat, ISME J., 4, 585–594, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2009.140, 2010.

Schimel, J. P. and Bennett, J.: Nitrogen mineralization: challenges of a changing paradigm, Ecol., 85, 591–602, https://doi.org/10.1890/03-8002, 2004.

Schmidt, S. K. and Lipson, D. A.: Microbial growth under the snow: Implications for nutrient and allelochemical availability in temperate soils, Plant Soil, 259, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PLSO.0000020933.32473.7e, 2004.

Sharma, S., Szele, Z., Schilling, R., Munch, J. C., and Schloter, M.: Influence of freeze-thaw stress on the structure and function of microbial communities and denitrifying populations in soil, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 72, 2148–2154, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.72.3.2148-2154.2006, 2006.

Skogland, T., Lomeland, S., and Goksøyr, J.: Respiratory burst after freezing and thawing of soil: Experiments with soil bacteria, Soil Biol. Biochem., 20, 851–856, https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(88)90092-2, 1988.

Sommerfeld, R. A., Mosier, A. R., and Musselman, R. C.: CO2, CH4 and N2O flux through a Wyoming snowpack and implications for global budgets, Nature, 361, 140–142, https://doi.org/10.1038/361140a0, 1993.

Song, Y., Zou, Y., Wang, G., and Yu, X.: Altered soil carbon and nitrogen cycles due to the freeze-thaw effect: A meta-analysis, Soil Biol. Biochem., 109, 35–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.01.020, 2017.

Stark, J. M. and Hart, S. C.: Diffusion technique for preparing salt solutions, kjeldahl digests, and persulfate digests for nitrogen-15 Analysis, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J., 60,1846–1855, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1996.03615995006000060033x, 1996.

Teepe, R. and Ludwig, B.: Variability of CO2 and N2O emissions during freeze-thaw cycles: results of model experiments on undisturbed forest-soil cores, J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci., 167, 153–159, https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.200321313, 2004.

Turner, M. M. and Henry, H. A. L.: Interactive effects of warming and increased nitrogen deposition on 15N tracer retention in a temperate old field: seasonal trends, Glob. Change Biol., 15, 2885–2893, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01881.x, 2009.

Vance, E. D., Brookes, P. C., and Jenkinson, D. S.: An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C, Soil Biol. Biochem., 19, 703–707, https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(87)90052-6, 1987.

Walker, V. K., Palmer, G. R., and Voordouw, G.: Freeze-thaw tolerance and clues to the winter survival of a soil community, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 72, 1784–1792, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.72.3.1784-1792.2006, 2006.

Wang, Q., Chen, M., Yuan, X., and Liu, Y.: Effects of freeze–thaw cycles on available nitrogen content in soils of different crops, Water, 16, 2348, https://doi.org/10.3390/w16162348, 2024.

Yanai, Y., Toyota, K., and Okazaki, M.: Response of denitrifying communities to successive soil freeze–thaw cycles, Biol. Fertil. Soils, 44, 113–119, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-007-0185-y, 2007.

Ye, Y., Wang, W., Zheng, C., Fu, D., and Liu, H.: Evaluation of cold resistance of four wild Carex speices, Chin. J. Appl. Ecol., 28, 89–95, https://doi.org/10.13287/j.1001-9332.201701.035, 2017.

Yu, X., Zou, Y., Jiang, M., Lu, X., and Wang, G.: Response of soil constituents to freeze–thaw cycles in wetland soil solution, Soil Biol. Biochem., 43, 1308–1320, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.03.002, 2011.

Zhang, X., Bai, W., Gilliam, F. S., Wang, Q., Han, X., and Li, L.: Effects of in situ freezing on soil net nitrogen mineralization and net nitrification in fertilized grassland of northern China, Grass Forage Sci., 66, 391–401, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2494.2011.00789.x, 2011.

Zheng, Z., Qu, Z., Diao, Z., Zhang, Y., and Ma, L.: Efficient utilization of winter nitrogen sources by soil microorganisms and plants in a temperate grassland, Glob. Ecol. Conserv., 54, e03135, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2024.e03135, 2024.

Zhou, J., Chen, Z., and Li, S.: Oxidation efficiency of different oxidants of persulfate method used to determine total nitrogen and phosphorus in solutions, Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal., 34, 725–734, https://doi.org/10.1081/CSS-120018971, 2003.

Zong, N. and Shi, P.: Effects of winter warming on carbon and nitrogen cycling in alpine ecosystems: a review, Acta Ecol. Sinica, 40, 3131–3143, https://doi.org/10.5846/stxb201904040655, 2020.