the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Dynamic upper-ocean processes enhance mesopelagic carbon export of zooplankton fecal pellets in the southern South China Sea

Ruitong Wu

Jiaying Li

Baozhi Lin

Yulong Zhao

Junyuan Cao

Xiaodong Zhang

Zooplankton are key contributors to the marine biological carbon pump by converting phytoplankton-derived organic carbon into fast-sinking fecal pellets. Despite the established role of upper ocean dynamics in regulating epipelagic biogeochemistry and plankton communities, their impact on mesopelagic fecal pellet carbon export remains poorly constrained. Here, we present time-series sediment trap mooring observations of fecal pellet fluxes at 500 m from August 2022–May 2023 in the southern South China Sea. Zooplankton fecal pellet fluxes display distinct seasonal patterns, with average numerical and carbon fluxes of 7.39×104 pellets and 1.27 mg C . Fecal pellets account for 10.0 %–42.6 % (average 21.6 %) of particulate organic carbon export, exceeding most oligotrophic regions. Mesopelagic fecal pellet fluxes are strongly correlated with upper-ocean dynamic processes, including winter mixing, tropical cyclones, and mesoscale eddies. Two tropical cyclones increase regional fecal pellet carbon export by more than 10 % of the annual carbon flux. One spring peak in March 2023 contributes more than 60 % of the total flux, likely driven by the combined effects of winter mixing, cold eddy activity, and spring zooplankton blooms. Our results highlight the critical role of upper-ocean dynamics in fecal pellet carbon export in the mesopelagic zone.

- Article

(9018 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(4559 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The ocean plays a pivotal role in regulating global carbon sink, absorbing 2.9±0.4 Gt C annually through coupled physical and biological mechanisms, mitigating the increasing anthropogenic carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (Friedlingstein et al., 2025). Central to this uptake lies the biological carbon pump (BCP), which converts massive CO2 in the surface ocean into particulate organic carbon (POC) via phytoplankton photosynthesis (Falkowski, 2012; Boyd and Trull, 2007; Nowicki et al., 2022). In the BCP, carbon is effectively transferred from the euphotic zone to the deep ocean through intertwined pathways (Siegel et al., 2023), including gravitational carbon transport (Boyd et al., 2019; Nowicki et al., 2022), active carbon transport by diel vertical migration (Steinberg and Landry, 2017; Smith et al., 2025), and physical mixing driven by submesoscale to meridional mechanisms (Boyd et al., 2019; Resplandy et al., 2019).

Zooplankton fecal pellets, produced through zooplankton grazing on phytoplankton and organic matter (Steinberg and Landry, 2017), constitute a major component of POC in the gravitational carbon pump. By compacting slow-sinking biogenic elements into dense particles, zooplankton significantly reduce microbial degradation and dissolution of organic matter during the sinking process, thereby enhancing regional carbon export efficiency (Turner and Ferrante, 1979; Turner, 2002). Modern methodological advances have enabled precise quantification of pellet morphology, density, and sinking velocity across diverse zooplankton taxa (Turner, 2002; Atkinson et al., 2012). Building on these capabilities, recent studies have deepened our understanding of fecal pellet flux dynamics by integrating multiple approaches: In-situ observations from sediment traps and large filtering systems provide high-resolution time-series flux records (Shatova et al., 2012; Turner, 2015; Li et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023; Cao et al., 2024; Darnis et al., 2024), while complementary approaches including satellite observations (Siegel et al., 2014) and numerical modeling (Stamieszkin et al., 2015; Countryman et al., 2022) largely expand the scope of investigation across broader spatial and temporal scales. Collectively, these investigations highlight two principle regulatory mechanisms: (1) bottom-up control via surface primary productivity and zooplankton community structure, mediated by regional biogeochemistry and hydrography, and (2) particle transformation processes during pellet sedimentation, including microbial degradation, particle repackaging, coprophagy, and zooplankton diel vertical migration (Turner, 2002, 2015). Episodic and seasonal events, including spring phytoplankton blooms (Dagg et al., 2003), monsoon cycles (Carroll et al., 1998; Roman et al., 2000; Ramaswamy et al., 2005), sea ice melting (Lalande et al., 2021), and El Niño events (Menschel and González, 2019) are reported to effectively increase mesopelagic fecal pellet export, often driving distinct high-flux episodes. Overall, fecal pellets fluxes contribute substantially to the biological carbon pump across different marine ecosystems, with their proportional contribution to POC varying widely from < 1 % to > 100 %, most < 40 % (reviewed in Turner, 2015).

Recent evidence highlights the importance of upper ocean dynamics in regulating surface biogeochemistry and carbon export, particularly in stratified oligotrophic systems (Dai et al., 2023). Transient processes including tropical cyclones, mesoscale eddies, and mixing events can rapidly modify surface physical-chemical gradients and plankton communities, overriding bottom-up controls on fecal pellet export. Cyclonic eddies are widely reported to enhance zooplankton biomass, abundance, and active transport (Strzelecki et al., 2007; Landry et al., 2008; Labat et al., 2009; Chen et al.; 2020; Belkin et al., 2022), restructure regional plankton communities (Franco et al., 2023), and elevate gravitational export through increased pellet production (Goldthwait and Steinberg, 2008; Shatova et al., 2012; Fischer et al., 2021). Similarly, typhoons, storms, and tropical cyclones are believed to intensify surface turbulence, stimulate phytoplankton blooms and trigger zooplankton responses that further modulate carbon export (Baek et al., 2020; Li and Tang, 2022; Chen et al., 2022, 2023a; Rühl and Möller, 2024). Yet, how these mechanisms influence mesopelagic (200–1000 m) fecal pellet fluxes remain poorly resolved, as most studies emphasize epipelagic (0–200 m) responses and seldom quantify the pellet-specific contribution to POC flux. In addition, these reported effects also vary by ecosystems: some eddies enhance pellet export (Goldthwait and Steinberg, 2008), whereas others attenuate flux despite elevated zooplankton biomass (Christiansen et al., 2018), reflecting complex dependencies on regional hydrology and zooplankton community structure.

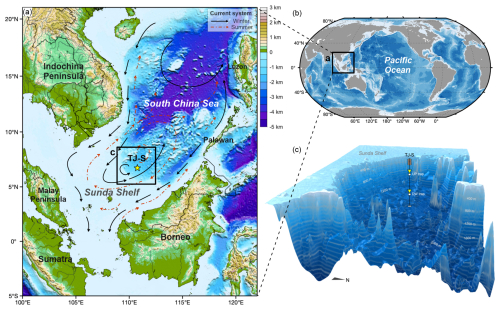

The South China Sea (SCS) is the largest semi-enclosed marginal sea in the western Pacific, spanning 3.5×106 km2 with an average depth of 1140 m (Wang and Li, 2009). Governed by the East Asian monsoon (EAM) system, the SCS represents a natural laboratory for investigating upper-ocean processes because of its dynamic interplay of surface mixing, mesoscale eddies, typhoons, and tropical cyclones. Regional fecal pellets account for over 20 % of POC flux during winter monsoon, underscoring their significance in carbon sequestration (Li et al., 2022). While seasonal export variability is often attributed to monsoon forcing (Li et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023; Cao et al., 2024), the role of individual physical processes in regulating zooplankton-mediated carbon export remain poorly constrained. Key questions include: (1) how transient processes such as cyclones and eddies influence mesopelagic fecal pellet fluxes, and (2) whether the EAM constitutes the dominant driver of fecal pellet export across SCS regimes. To address these gaps, we analyze high-resolution time-series sediment trap records (August 2022–May 2023) from mooring station TJ-S in the oligotrophic southern SCS, combining with synchronous physical and biogeochemical data. This study provides the first quantitative assessment of how winter-mixing, tropical cyclones and mesoscale eddies collectively regulate fecal pellet carbon export, offering new insights into BCP dynamics in monsoon-driven marginal systems.

2.1 Environmental background

Mooring TJ-S (6.72° N, 110.76° E, 1630 m water depth) is located in the southern SCS near the Sunda Shelf (Fig. 1a), where the EAM exerts dominant control on local wind fields and ocean circulation (Shaw and Chao, 1994). As a typical oligotrophic region (Wong et al., 2007; Du et al., 2017), both primary production and hydrological conditions in the monsoon-controlled area exhibit pronounced seasonal characteristics: In summer, southwest monsoon from June–September establish an anticyclonic surface circulation (Hu et al., 2000), resulting in strong thermal stratification that limits nutrient upwelling and primary production. From November–April, strong northeast winter monsoon drives a cyclonic surface circulation while intensifying vertical mixing, entraining deep nutrients while sustaining high primary production (Hu et al., 2000; Fang et al., 2002).

Figure 1Geographic locations of the study area and the mooring system. (a) Surface current systems in the southern SCS, after Liu et al. (2016). Black arrows indicate surface current circulation in winter, and red dash-line arrows represent surface currents in summer. (b) Location of the research area. (c) 3-D bathymetry map and vertical structures of the sediment trap mooring system TJ-S.

In this region, the mixed layer depth (MLD) is primarily controlled by air–sea heat fluxes and exhibits remarkable seasonal variations under monsoon forcing, deepening during June–August and December–February but remaining shallower than 60 m annually (Qu et al., 2007; Thompson and Tkalich, 2014; Liang et al., 2019). Copepods dominate the local zooplankton community (47.1 % of total species), followed by ostracods (8.4 %) and siphonophores (7.8 %), along with contributions from pteropods, euphausiids, hydrozoans, amphipods, and various larval forms (Du et al., 2014). Diatoms and dinoflagellates dominate the surface phytoplankton community, with contributions from picophytoplankton and cyanobacteria (Zhu et al., 2003; Ke et al., 2012, 2016; Wang et al., 2022). Phytoplankton exhibit maximal abundance in subsurface waters (35–75 m), while zooplankton biomass and abundance peak in the upper 200 m, both displaying a gradual decrease with depth (Zhu et al., 2003). Plankton community structure and distribution are regulated by regional geographical settings, hydrological conditions, and dynamic processes, with wind fields, water mass characteristics, and vertical mixing acting as key external drivers. In the southern SCS, these factors operate predominantly through monsoon-forced circulation patterns (Wang et al., 2015).

2.2 Sample processing and fecal pellet analysis

Between August 2022 and May 2023, two sediment traps (UP trap and DW trap) were deployed at depths of 500 m and 1590 m, respectively, each featuring a sampling area of 0.5 m2 (Fig. 1c). The upper trap was equipped with 13 receiving cups, collecting samples over 22 d intervals, while the downward trap contained 22 receiving cups with 13 d intervals. Prior to deployment, all cups were filled with NaCl-buffered HgCl2 deionized water solution to inhibit biological degradation and thereby ensure the reliability of organic geochemical analyses. Each cup was fitted with a plastic baffle to prevent the entry of large organisms. The traps were retrieved in August 2023. However, the DW trap malfunctioned after October 2022, leaving only two available samples from August–September. Therefore, this study focuses primarily on the complete time-series samples obtained from the UP trap for subsequent analysis and discussion.

All sediment trap samples were stored at < 4 °C immediately after retrieval. Sample separation and pretreatment were carried out at the State Key Laboratory of Marine Geology at Tongji University, following Li et al. (2022). Samples were sieved through a 1 mm stainless steel mesh stack to roughly separate zooplankton fecal pellets from other components. Swimming organisms, supernatants, and plant debris were manually removed with tweezers. Each sample was then split into multiple aliquots ( to depending on the sample quantity). One aliquot was used for independent fecal pellet analysis, whereas others were prepared for total mass flux (TMF, ) and POC measurements. TMF flux was calculated from sample dry weight (mg) normalized to the trap collection area (0.5 m2) and sampling duration, while POC and component-specific mass fluxes (e.g., opal flux, carbonate flux, and terrigenous flux) were derived by the measured TMF percentage (%).

Prior to fecal pellet enumeration, wet subsamples were sieved through a 20 µm Nitex© mesh to separate fecal pellets from finer terrigenous sediments. The retained fraction was rinsed into a gridded petri dish and evenly distributed for microscopic analysis. Fecal pellets were then enumerated using a Zeiss Stemi 508 stereomicroscope. To standardize measurements, fecal pellets were categorized into large (width > 100 µm) and small (width < 100 µm) pellets. Large pellets were counted and photographed at 8× magnification, while small pellets were enumerated at 50× magnification from 32–50 random selected fields. Densely packed samples were further split (2–3 times) before imaging. Morphological parameters (length and width) were measured with Image J, and their biovolume was calculated from geometric approximations (Li et al., 2022). Biovolumes were converted to carbon content using a carbon-volume conversion factor of 0.036 mg C mm−3, as previously reported in the southern SCS (Li et al., 2022). Fecal pellet numerical (FPN) flux (pellets ) and fecal pellet carbon (FPC) flux (mg C ) were then derived from counts and carbon estimates, normalized to the petri dish area, photographic coverage, trap collection area (0.5 m2), and sampling duration.

2.3 Hydrological data sources

To investigate the temporal variability of zooplankton fecal pellet fluxes in sediment trap samples and their underlying mechanisms, we performed a comprehensive analysis that incorporated key physical and biogeochemical parameters. The following selected products were chosen for their sufficient spatial resolution, operational continuity, and documented validation in the SCS or adjacent regions, which enables an integrated assessment of physical forcing as well as biogeochemistry conditions. Hourly wind speed and sea surface temperature (SST) were obtained from the fifth-generation atmospheric reanalysis of the global climate (ERA5, 0.25°×0.25°) provided by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), which is forced by a coupled atmosphere–ocean assimilation system, and has been extensively evaluated against in-situ buoy and station data in the SCS (Liu et al., 2022; Zhai et al., 2023). Daily mixed layer depth (MLD) was obtained from the CMEMS Global Ocean Physics Analysis and Forecast (0.83°×0.83°, GLOBAL_ANALYSISFORECAST_PHY_001_024), which assimilates satellite and Argo data and has been shown to reproduce mixed-layer and circulation features in the region (Trinh et al., 2024). Daily sea level anomalies (SLA) were derived from the Global Ocean Gridded L4 Sea Surface Heights And Derived Variables Near Real time products (0.125°×0.125°, SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_L4_NRT_008_046), where SLA is estimated by interpolation of different altimeter missions measurements, and has been validated for reproducing mesoscale dynamics in the SCS and adjacent areas (Yao and Wang, 2021). For biogeochemical variables, daily chlorophyll a (Chl a) and primary production (PP) data were obtained from the CMEMS Global Ocean Biogeochemistry Analysis and Forecast product, which couples the NEMO ocean circulation model with the PISCES biogeochemical model and has been widely applied in SCS studies (Chen et al., 2023b; Wahyudi et al., 2023; Marshal et al., 2025). Zooplankton biomass was derived from the CMEMS Global Ocean Low and Mid Trophic Levels (LMTL, GLOBAL_MULTILAYER_BGC_001_033) generated by the SEAPODYM-LMTL model. This product provides two-dimensional biomass fields of zooplankton and six micronekton functional groups (expressed as carbon mass, g C m−2), and is increasingly used as an explanatory variable in habitat and population studies (Lehodey et al., 2015, 2020). Wind stress was calculated as , where V is wind speed (m s−1) at 10 m above the sea surface, ρ is air density (1.225 kg m−3), and Cd is the drag coefficient. The subsurface deep chlorophyll maximum (DCM) was identified manually from CMEMS chlorophyll profiles, which provide data across 31 depth levels between 0 and 500 m.

2.4 Statistical analysis and generalized linear model (GLM)

Statistical analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics (v27). Pearson's correlation was applied to examine relationships among environmental variables during monsoon and non-monsoon periods, and group differences in normally distributed data were evaluated using two-sided t-tests. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Graphical outputs were generated using Grapher (v15), while marine data maps were produced using MATLAB R2020a using the M_Map package (v1.4). Three-dimensional topography maps were constructed in QGIS (v3.16) with the Qgis2threejs plugin (v2.8).

To quantify the relative contributions of different physical forcing events (i.e. monsoon, typhoon, and mesoscale eddies to fecal pellet export, we applied generalized linear models (GLMs) with a Gamma distribution and a log link function. Fecal pellet fluxes (FPN, FPC) were analyzed as response variables (Y) in separate models. The GLM can be expressed as:

Each physical event (Xn) was represented as an independent binary factor (0= absence, 1= presence) indicating whether the event occurred during the sampling period. Model coefficients (βn) were estimated using maximum likelihood. The residual term (ε) accounted for unexplained variability.

3.1 Fecal pellet fluxes and characteristics

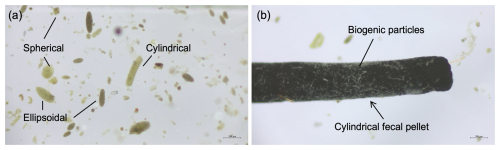

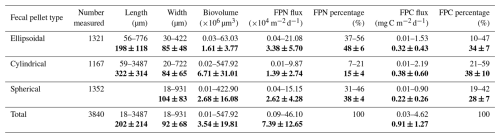

Three types of zooplankton fecal pellets were identified at Mooring TJ-S: spherical, cylindrical, and ellipsoidal (Fig. 2a). Most pellets exhibited compact structures with distinct edges and colors ranging from light green to dark brown. Larger pellets were typically darker, while smaller ones appeared more transparent (Fig. 2b). Geometric and flux characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 3, with detailed data in Table S1 in the Supplement. Cylindrical pellets were the largest, with mean biovolumes (6.71×105 µm3) about 2–4 times those of ellipsoidal (1.61×105 µm3) and spherical (2.68×105 µm3) pellets (p<0.001). Spherical pellets were also larger than ellipsoidal pellets (p<0.05). Considerable size variability occurred with types, particularly cylindrical pellets, which range in length from over 1 mm and width from more than 400 µm for larger specimens to less than 50 µm in width for smaller specimens (Table 1; Figs. S7 and S8 in the Supplement).

Figure 2Optical micrograph of fecal pellets from typical samples at TJ-S in the southern SCS. (a) Three types of fecal pellets (spherical, cylindrical, and ellipsoidal). (b) A carbon-rich cylindrical fecal pellet with biogenic particles attached to its surface.

Table 1Geometric parameters and fecal pellet fluxes at TJ-S (500 m) in the southern SCS. Bold values are the average and standard deviations.

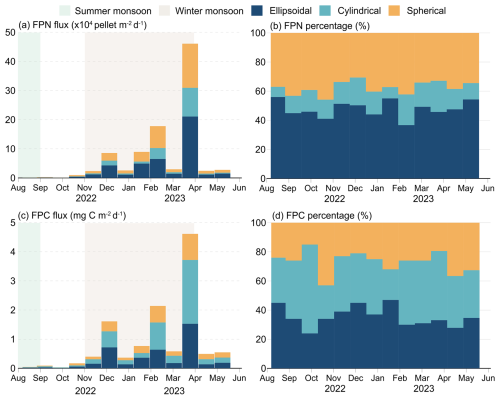

Figure 3Time-series variation of FPN and FPC at sediment trap Mooring TJ-S (500 m) in the southern SCS. (a) FPN flux; (b) FPN percentage; (c) FPC flux; (d) FPC percentage.

FPN ranged from 9.4×102 to 4.61×105 pellets (mean: 7.39×104 pellets , Fig. 3a), while FPC spanned from 0.03 mg C to 4.62 mg C (mean: 0.91 mg C , Fig. 3c), both exhibiting pronounced seasonal variations. Both fluxes reached annual minimum in late summer, with FPN of 937 pellets and FPC of 0.03 mg C in mid-September. From October–February, both fluxes increased steadily, reaching a major peak at the end of February, when FPN rose to 1.78×105 pellets and FPC to 2.14 mg C . A secondary peak occurred in late November, when FPN surging to 8.57×104 pellets , and FPC reaching 1.61 mg C , a 4–5 fold increase relative to adjacent samples. In early March, fluxes decreased again, with FPN dropping to 2.98×104 pellets and FPC decreasing to 0.58 mg C . However, a sharp surge followed in mid-March, when FPN surged to 4.61×105 pellets and FPC to 4.62 mg C , representing the annual maximum. This March peak was 2–3 times greater than the late February and November peaks, and was 10–17 times higher than adjacent samples. Fluxes declined from April–May, averaging 2.61×104 pellets for FPN and 0.52 mg C for FPC, with a slight increasing trend noted in May.

Fecal pellet contributions revealed distinct contributions to both FPN and FPC flux (Fig. 3b and d). Ellipsoidal pellets were numerically dominant (3.38×104 pellets , 48 % of total FPN), followed by spherical (2.62×104 pellets , 38 %) and cylindrical pellets (1.39×104 pellets , 15 %). During specific seasons, ellipsoidal and spherical pellets together accounted for over 90 % of total FPN. The contribution to carbon flux was size-dependent. Cylindrical pellets, despite numerical scarcity, contributed disproportionately (38 % of total FPC) due to largest biovolume. Ellipsoidal pellets, though numerically dominant, accounted for 34 % of FPC, while spherical pellets represented only 28 %. The size-driven disparity was particularly pronounced during low-flux periods. For example, in late September, when the total pellet flux reached its minimum, large cylindrical pellets contributed more than 60 % of FPC flux despite their low abundance.

3.2 POC flux and FPC POC ratio

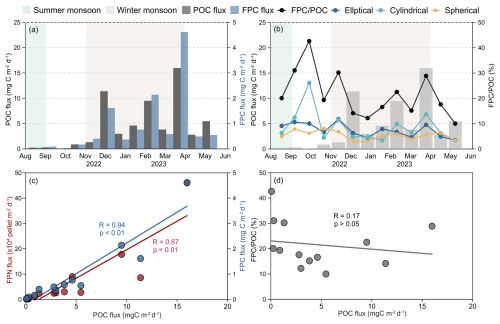

During the sampling period, POC fluxes varied significantly, ranging from 0.08 mg C to 15.97 mg C , with an average of 4.56 mg C , displaying seasonal variations that generally paralleled the patterns of FPN and FPC (Fig. 4a and c). Fluxes were lowest in late summer (0.08 mg C ), followed by a gradual increase from October–February, reaching a peak at 9.50 mg C in February (Fig. 4a). A distinct peak of 11.38 mg C was observed in late November, which exceeded the February peak and was 4–8 times higher than adjacent samples. Following a temporary decline to 3.83 mg C in early March, POC fluxes surged to the annual maximum of 15.97 mg C by the end of the month before stabilizing at lower levels (average 4.13 mg C ) from April–May. The contribution of FPC to POC at 500 m fluctuated between 10.0 % and 42.6 % (average 21.6 %), displaying inverse seasonal variations to POC fluxes (Fig. 4b and d). FPC POC ratio remained elevated during summer, averaging around 31 %, but declined during the winter monsoon. Notably, transient peaks in the FPC POC ratio were observed in late November (30.2 %), February (22.5 %), and late March (28.9 %), coinciding with major POC flux events (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4POC flux and FPC POC ratio at Mooring TJ-S in the southern SCS. (a) Total POC flux and FPC flux; (b) FPC POC ratio; (c) correlations between FPC flux, FPN flux, and POC flux; (d) correlations between FPC POC ratio and POC flux. Solid lines indicate a linear correlation with a coefficient of R.

3.3 Upper-ocean processes during the sampling period

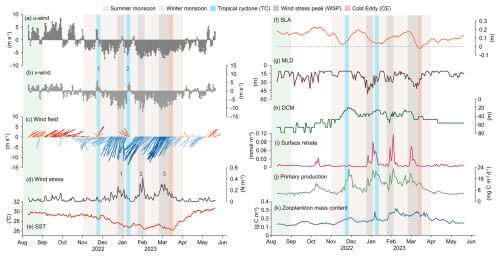

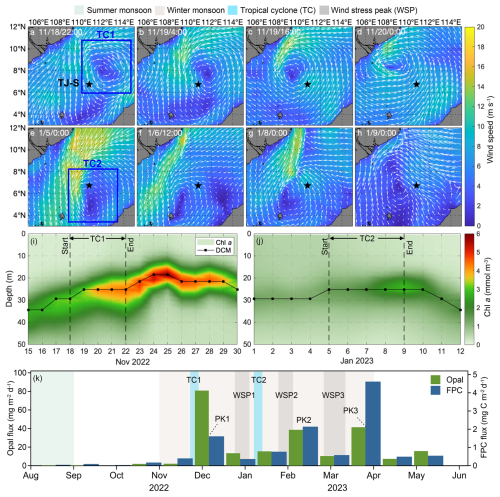

Physical and biogeochemical parameters exhibited clear seasonal variability from August 2022–May 2023 (Fig. 5). From August–September, station TJ-S was dominated by weak southwesterly winds (average 3.76 m s−1, Fig. 5a–c). From October onward, winds progressively shifted northeastward and intensified, reaching 6.91–7.95 m s−1 between December and March, with a maximum of 13.8 m s−1 at the end of January. From late March–April, wind speed decreased to approximately 3 m s−1, and wind direction gradually turned southward. Wind stress ranged from 0.0001–0.4273 N m−2, and three pronounced peaks (wind stress peaks, WSPs) were identified during the EAM period (Fig. 5d): WSP1 in late December (0.27 N m−2), WSP2 in late January (0.43 N m−2) and WSP3 in early March (0.31 N m−2). Two tropical cyclones (TC1, 18–22 November 2022; TC2, 5–9 January 2023) were identified based on wind direction and horizontal wind field observations (Fig. 5c, see Fig. 8 in discussion). Collectively, these features confirm the dominance of winter monsoon from November–April. SST ranged between 26.1 and 30.7 °C, cooling from late summer to early spring under the EAM and rebounded rapidly thereafter, displaying inverse seasonal patterns (Fig. 5e). SLA variability indicated strong mesoscale eddy activity during the sampling period (Fig. 5f). A marked negative SLA in late March corresponded to a cold eddy event (see Fig. 8 in discussion). MLD varied between 10.14 m and 50.35 m, averaging 18.48 m, with pronounced deepening events occurring during the winter monsoon, largely consistent with wind forcing and WSPs (Fig. 5g). Surface (0–100 m) PP averaged 6.72 in August–October (Fig. 5j), then gradually increased in November, with four major peaks related to TCs and MLD deepening: late November (22.83 ), early January (21.92 ), early February (23.21 ), and late February (19.73 ). PP subsequently declined after March, indicating the seasonal variability related to the EAM.

Figure 5Hydrological parameters at the sediment trap Mooring TJ-S in the southern SCS. (a) eastward component for 10 m wind (u), where positive values represent eastern winds, and negative values for western wind; (b) northward component for 10 m wind (v), where positive values represent northern winds, and negative values for southern winds; (c) sea surface wind field; (d) sea surface wind stress; (e) sea surface temperature (SST); (f) sea level anomaly (SLA); (g) mixed layer depth (MLD); (h) deep chlorophyll maximum (DCM); (i) surface nitrate; (j) net primary productivity (NPP); (k) zooplankton mass content expressed in carbon.

In oligotrophic systems like the SCS, dynamic processes in the upper ocean can override bottom-up controls on fecal pellet export by altering both phytoplankton availability and zooplankton grazing behavior. Elevated pellet fluxes are usually associated with phytoplankton blooms (Huffard et al., 2020), which occur when vertical mixing and upwelling supply nutrients and enhance primary production (McGillicuddy et al., 1999; van Ruth et al., 2010). Such bloom events can stimulate zooplankton feeding activity and thereby increase fecal pellet production and export. In the southern SCS, these fluxes are primarily modulated by regional surface hydrodynamics and biogeochemical conditions. Processes during sedimentation, such as microbial remineralization, can strongly regulate transport efficiency but remain difficult to quantify due to the lack of downward sediment trap samples. Strong lateral transport has been reported in the region, while available evidence suggests that most sinking organic carbon originates from local primary production with limited lateral inputs (Zhang et al., 2019, 2022). Here, we evaluate the impacts of several key dynamic drivers on fecal pellet carbon export in the upper trap (500 m) at Mooring TJ-S, including winter monsoon mixing, tropical cyclones, and mesoscale eddies, as well as the potential roles of lateral transport and seasonal zooplankton blooms.

4.1 Contribution of winter-mixing related to the EAM

In the southern SCS, FPN and FPC exhibit remarkable seasonal variability and is primarily modulated by the EAM. Previous studies have shown that fluxes peak in winter and reach minima in summer, consistent with monsoon-driven changes in both wind speed and MLD (Li et al., 2022, 2025; Wang et al., 2023; Cao et al., 2024). High SST, weak winds, and strong stratification in summer largely restrict surface nutrient supply, leading to low primary productivity, zooplankton biomass, and fecal pellet export. In contrast, strong winter monsoon winds and surface cooling enhance vertical mixing, bringing nutrients to the surface, stimulating phytoplankton blooms, and promoting both fecal pellet production and carbon export.

FPN and FPC fluxes at TJ-S generally followed this seasonal pattern, with relatively low values in summer and elevated fluxes in winter (Fig. 3). Three pronounced pellet flux peaks (PKs, PK1 in late November, PK2 in mid-February, PK3 in late March) were observed. Several WSPs occurred during the same period (Fig. 5d), coincided with deepened MLD, shallowed DCM, and increased surface nutrients (Fig. 5g and h). Considering both ecological response times and the 22 d sampling interval of sediment traps, PK2 and PK3 can be temporally linked to WSP2 and WSP3, respectively. PK1 is closely correlated with DCM elevation and zooplankton biomass increase, but appears unrelated to WSP1, suggesting other mechanisms beyond monsoon mixing.

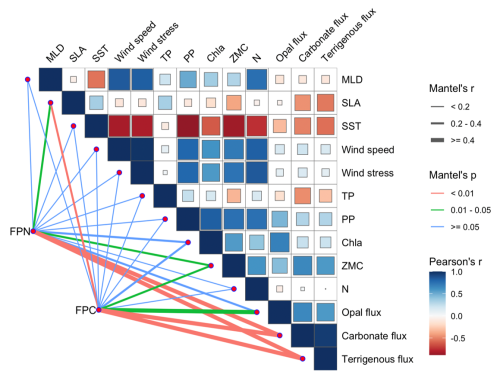

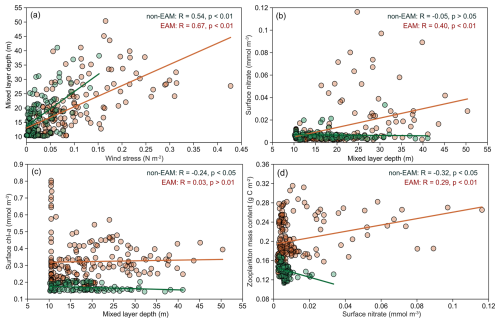

At Mooring TJ-S, this monsoon-driven mechanism was supported by correlation analysis (Fig. 6). MLD is strongly correlated with wind stress during both winter monsoon (R=0.67, p<0.01) and non-monsoon seasons (R=0.54, p<0.01, Fig. 6a). Both surface nitrate and Chl a concentration increase with deepening MLD during the EAM but show an opposite trend during non-monsoon seasons (Fig. 6b and c). Zooplankton biomass also responds positively to surface nitrate during EAM (R=0.29, p<0.01) but negatively during non-monsoon seasons (, p<0.01, Fig. 6d). These relationships highlight the key role of winter mixing in sustaining higher trophic levels and fecal pellet flux.

Figure 6Correlation between hydrological parameters during monsoon and non-monsoon periods. (a) Wind stress and MLD; (b) surface nitrate and MLD; (c) surface Chl a and MLD; (d) zooplankton mass content and surface nitrate. Solid lines indicate a linear correlation with a coefficient of R.

According to the monsoon-driven hypothesis, intensified vertical mixing during winter monsoon can facilitate effective nutrient replenishment from deeper waters, supporting elevated surface primary productivity and chlorophyll concentrations indicative of phytoplankton blooms, and under high-food-availability conditions, zooplankton biomass increase significantly, resulting in rich fecal pellet production. We believe that if mooring TJ-S follows the monsoon-driven hypothesis, FPC and FPN should exhibit a good correlation with WSP events, with the annual maximum occurring during periods of the highest wind stress and the highest zooplankton biomass (WSP2). The response time depends on the complexity of the surface ecosystem, zooplankton community structure, and food chain effects in the research area. The plankton community in the southern SCS features a small class community, thus often resulting in a longer food chain (Bao et al., 2023). Thus, a time lag of several days to several weeks is expected.

Contrary to our expectations, the annual maximum flux (PK3) occurred in March, lagging behind the strongest wind stress peak (WSP2) and associated with weaker mixing conditions. Despite lower wind stress, zooplankton biomass, and nutrient levels than in February (PK2), PK3 accounted for over 60 % of the annual FPC export, a tenfold increase relative to adjacent samples (Fig. 3). Such a pronounced spring flux maximum has not been reported in the northern or western SCS (Wang et al., 2023; Cao et al., 2024). Our observations indicate that, while EAM-driven mixing dominates the seasonal cycle and explains over 90 % of annual fluxes, additional mechanisms are required to account for the exceptionally high spring fluxes in March (PK3) and the early peak in October (PK1).

4.2 Impacts of typhoons and tropical cyclones

Typhoons and tropical cyclones play a key role in inducing phytoplankton blooms and promoting mesopelagic carbon export in the SCS. During typhoon events, intensified wind stress drives surface turbulent mixing, Ekman pumping and nutrient entrainment, elevating primary production and organic carbon export (Subrahmanyam et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2020; Li and Tang, 2022). The magnitude of these effects depends largely on cyclone characteristics, including intensity (represented by maximum wind speed, WS) and transition speed (TS) (Sun et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2017). In the open ocean, slow-moving cyclones with high wind speed (WS >25 m s−1, TS <5 m s−1) are reported to generate the strongest blooms (Li and Tang, 2022).

At TJ-S, two notable tropical cyclone events (TC1 and TC2) were identified during the observation period (Fig. 7a–d). WS of the cyclones is determined by satellite data analysis, and TS is approximated with the moving distance estimated via the Haversine function. TC1 (18–22 November 2022) was a slow-moving cyclone with slow wind speed (WS ∼25 m s−1, TS ∼5 m s−1) that passes directly over the station. A pronounced phytoplankton bloom was observed after its passage, with chlorophyll concentrations in the upper 50 m rising to more than twice of the background levels and persisting for about one week (Fig. 7i). This bloom coincided with significant increases in fecal pellet fluxes, with FPN and FPC reaching 4–5 times the values of adjacent samples, contributing over 10 % of the annual flux (Fig. 7l). Elevated opal fluxes during this period suggest enhanced diatom productivity (Fig. 7k). Given that the EAM was relatively weak at this time, these features can be primarily attributed to the passage of TC1.

Figure 7The possible impact of tropical cyclones at TJ-S. (a–d) Surface wind field from 18–20 November 2022, representing the passage of TC1. (e, f) Surface wind field from 5–9 January 2023, representing the possible impact of TC2. (i, j) Chl a concentration and DCM variations during the passage of TC1 and TC2. (k) Opal flux and FPC flux.

TC2 (5–9 January 2023), in contrast, did not directly pass over the station but remained southwest of TJ-S. Nevertheless, we still observed increases in chlorophyll concentration, DCM shoaling, and elevated fecal pellet fluxes (Fig. 7j), indicating that even peripheral cyclone influence can enhance local BCP. These findings highlight that both direct and indirect impacts of tropical cyclones can substantially stimulate primary production and fecal pellet carbon export in the southern SCS, underscoring the key role of tropical cyclones to mesopelagic carbon export. However, the absence of cyclones from February–March suggests that other physical or biochemical processes must contribute to the spring peak.

4.3 Potential impact of mesoscale eddy activities

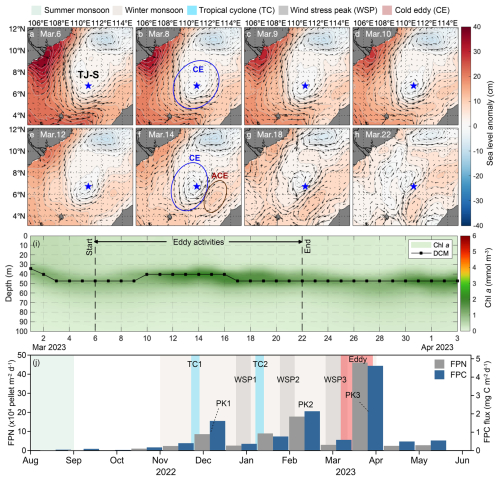

During 6–22 March 2023, strong eddy activities occurred at mooring TJ-S, well coincided with the spring flux maximum recorded in sediment trap samples from 12 March to 3 April (Fig. 8). A cyclonic eddy (CE) formed on 6 March (Fig. 8a), subsequently propagated north-eastward before dissipating in the northwestern waters around 22 March (Fig. 8h). Following the formation of CE, an anticyclonic eddy (ACE) developed southeast of the station along the Borneo coast, gradually moving southwest. From 14 March, TJ-S remained persistently located at the frontal zones between these two counter-rotating eddies, and the influence of eddy activities ended around 22 March.

Figure 8The possible impact of mesoscale eddy activities at Mooring TJ-S. (a–h) Sea surface anomaly and current field from 6-22 March 2023. The blue star represents the location of TJ-S. (i) Chl a concentration and DCM during eddy activity. (j) FPN and FPC fluxes.

Recent studies suggest that dynamic mechanisms of mesoscale eddies can carry large volumes of high-kinetic-energy and thermally anomalous water masses during their movement. The horizontal advection and vertical pumping processes associated with these eddies can significantly influence regional hydrographic structures, current distributions, nutrient concentrations, and primary productivity (Chelton et al., 2011; Parker, 1971; Richardson, 1980). CEs are widely recognized to induce dome-like uplift of isopycnal layer, enhance vertical mixing, increase water column instability, and promote upward nutrient transport from deeper layers, which can further effectively replenish surface nutrients, triggering phytoplankton blooms and increase primary productivity (Xiu and Chai, 2011; Falkowski et al., 1991; McGillicuddy et al., 1999; Benitez-Nelson et al., 2007; Siegel et al., 1999; Garçon et al., 2001; Jadhav and Smitha, 2024). In contrast, ACEs are generally believed to deepen isopycnals and cannot stimulate primary productivity (Xiu and Chai, 2011; Gaube et al., 2013). Recent studies have revealed that mesoscale eddies modulate sea surface chlorophyll concentrations and phytoplankton distributions through complex interacting mechanisms (Chelton et al., 2011; McGillicuddy et al., 2007; Gaube et al., 2014; Siegel et al., 2011), including advective transport via eddy rotation (Chelton et al., 2011), entrainment of surrounding water masses and particulates at eddy peripheries (Early et al., 2011), vertical circulation driven by eddy instability and wind forcing (Martin and Richards, 2001), and Ekman transport (Siegel et al., 2008; Gaube et al., 2014). In specific situations, elevated Chl a concentrations are also observed in ACEs. Notably, frontal zones at eddy margins with high current velocity are reported to generate sub-mesoscale upwelling through intense shear forces, thus facilitating the rise of nutrient-rich deep water (Siegel et al., 2011). When CEs rotate around ACEs, kinetic energy effects can vertically induce nitrite-enriched water into the euphoric zone, increasing phytoplankton biomass.

Thus, we assume that these eddy activities significantly enhance regional vertical mixing with their high-velocity shear-generating upwelling that can alter subsurface nutrient distributions, which results in favorable conditions for plankton blooms. Estimation of the eddies' trajectories suggests that they can likely facilitate water mass exchange between the Mekong River plume and Borneo coastal waters, providing additional inputs of nutrients, particulate matter, and plankton communities. A slight elevation of the SCM is observed from 9–17 March (Fig. 8i). Zooplankton mass content, opal flux, and POC flux also increase during the eddy activity.

Notably, MLD during eddy period is deeper than during the winter maximum, suggesting the possible interactions between EAM and mesoscale eddies. The combined effects of cyclonic eddy activity and monsoon-induced vertical mixing have been widely reported in the SCS and can significantly increase the export efficiency of BCP, as evidenced by elevated POC and opal fluxes during eddy activities (Li et al., 2017). However, despite peak pellet fluxes and plankton biomass, neither Chl a concentration nor primary production showed elevated values during this period. This pattern likely reflects strong top-down control, where intense zooplankton grazing pressure suppressed the standing stocks of phytoplankton, a phenomenon well documented in high-nutrient, low-chlorophyll regions (Gervais et al., 2002; Schultes et al., 2006; Henjes et al., 2007).

4.4 Quantification of specific contribution of upper-ocean dynamics

The strong correlations revealed by the Mantel test (Fig. 9) highlight the close coupling between fecal pellet export and regional upper-ocean dynamics. The significant relationships of both FPN and FPC with sea level anomaly (SLA) and zooplankton biomass (ZMC) suggest the primary regulation of zooplankton productivity and key impacts of eddy activities (p<0.05). Positive associations with other mass components, including carbonate, silica, and terrigenous fluxes (p<0.01) further indicate the importance of aggregation and mineral ballasting in facilitating fecal pellet export during high-flux events. Collectively, these correlations imply that different components of POC tend to increase proportionally during periods of intensified pellet export, driven by episodic events such as monsoon and eddy activities.

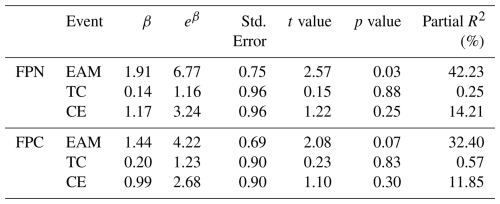

Table 2Summary of GLM results showing the effects of three dynamic events, EAM, TC and cyclonic eddy (CE) on fecal pellet flux (FPN, FPC). Estimates (β) represent the fitted coefficients of log-transformed fluxes. Partial R2 values were calculated using the formula to quantify the independent contribution of each event.

In order to quantify the relative contributions of the three events, a simple GLM model was conducted (Table 2). Among all the three events examined, the EAM exerted the most pronounced influence, enhancing FPN by more than sixfold (p<0.05) and explaining 42 % of its temporal variability. Though typhoon and eddy events also showed positive effects, their statistical significance was weaker, likely due to the limited number of observations and their short temporal duration. These findings underscore the dominant role of monsoon-driven mixing in stimulating fecal pellet production and export in the southern SCS. Nonetheless, our small sample size (n=13) may have led to potential overfitting in these models. Further studies, which incorporate longer time scales and higher temporal resolution would help to refine these quantitative estimates.

In this study, we address comprehensive studies on zooplankton fecal pellet characteristics, seasonal flux variations, and controlling mechanisms by using sediment trap samples and open-source hydrological data. In the southern SCS, both FPN and FPC fluxes display distinct seasonal patterns, with minimum values occurring in late September and increasing values from October–February. The EAM system plays a dominant role in regional fecal pellet production, evidenced by seasonal variations and corresponding changes in wind stress, MLD, DCM, and fecal pellet flux. In contrast to traditional paradigms, rather than the winter peak, the spring annual maximum makes the greatest contribution, indicating the possible contribution of other physical processes. At Mooring TJ-S, high zooplankton fecal pellet fluxes result from the integrated mechanisms of winter mixing, tropical cyclones, eddy activities, and spring zooplankton blooms. Cyclone-induced fluxes account for over 10 % of the annual total. The spring annual maximum contributes more than 60 % of the total flux, likely resulting from the combined effects of the EAM and eddy activities. In the SCS, zooplankton fecal pellets make the most contribution to POC export in the southern region, with FPC POC ratio ranging from 10.0 %–42.6 %, reaching an average of 21.6 %. This range is relatively higher than the typical values reported for oligotrophic mesopelagic regions (0.3 %–35 %; reviewed in Turner, 2015; Li et al., 2022), including Station ALOHA in the central North Pacific (14 %–35 %; Wilson et al., 2008), the northwestern Mediterranean (3 %–35 %; Carroll et al., 1998), and the Sargasso Sea (0.4 %–10.0 % at 500 m; Shatova et al., 2012), highlighting the critical role of zooplankton fecal pellets in shaping the unique carbon export process in the southern SCS.

Data of zooplankton fecal pellets and particulate organic carbon generated by this study can be found in the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-23-345-2026-supplement.

ZL designed the study and obtained the funding. RW carried out the measurements and wrote the original draft with help of ZL, JL, BL, and JC. ZL, JL, BL, YZ, JC, XZ, and RW participated in mooring deployment/recovery cruises.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We would like to thank Hongzhe Song and Wenzhuo Wang for their assistance during the laboratory analysis and mooring deployment/recovery cruises. We especially thank Huixiang Xie (editor) and the two anonymous referees for their valuable comments that greatly improved this paper.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42130407 and 42188102).

This paper was edited by Huixiang Xie and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Atkinson, A., Schmidt, K., Fielding, S., Kawaguchi, S., and Geissler, P. A.: Variable food absorption by Antarctic krill: Relationships between diet, egestion rate and the composition and sinking rates of their fecal pellets, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 59–60, 147–158, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2011.06.008, 2012.

Baek, S. H., Lee, M., Park, B. S., and Lim, Y. K.: Variation in phytoplankton community due to an autumn typhoon and winter water turbulence in Southern Korean Coastal Waters, Sustainability, 12, 2781, https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072781, 2020.

Bao, M., Xiao, W., and Huang, B.: Progress on the time lag between marine primary production and export production, J. Xiamen Univ. (Nat. Sci.), 62, 314–324, https://doi.org/10.6043/j.issn.0438-0479.202204044, 2023.

Belkin, N., Guy-Haim, T., Rubin-Blum, M., Lazar, A., Sisma-Ventura, G., Kiko, R., Morov, A. R., Ozer, T., Gertman, I., Herut, B., and Rahav, E.: Influence of cyclonic and anticyclonic eddies on plankton in the southeastern Mediterranean Sea during late summertime, Ocean Sci., 18, 693–715, https://doi.org/10.5194/os-18-693-2022, 2022.

Benitez-Nelson, C. R., Bidigare, R. R., Dickey, T. D., Landry, M. R., Leonard, C. L., Brown, S. L., Nencioli, F., Rii, Y. M., Maiti, K., Becker, J. W., Bibby, T. S., Black, W., Cai, W. J., Carlson, C. A., Chen, F., Kuwahara, V. S., Mahaffey, C., McAndrew, P. M., Quay, P. D., Rappe, M. S., Selph, K. E., Simmons, M. P., and Yang, E. J.: Mesoscale eddies drive increased silica export in the subtropical Pacific Ocean, Science, 316, 1017–1021, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1136221, 2007.

Boyd, P. W. and Trull, T. W.: Understanding the export of biogenic particles in oceanic waters: Is there consensus?, Prog. Oceanogr., 72, 276–312, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2006.10.007, 2007.

Boyd, P. W., Claustre, H., Levy, M., Siegel, D. A., and Weber, T.: Multi-faceted particle pumps drive carbon sequestration in the ocean, Nature, 568, 327–335, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1098-2, 2019.

Cao, J., Liu, Z., Lin, B., Zhao, Y., Li, J., Wang, H., Zhang, X., Zhang, J., and Song, H.: Temporal and vertical variations in carbon flux and export of zooplankton fecal pellets in the western South China Sea, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I, 207, 104283, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2024.104283, 2024.

Carroll, M. L., Miquel, J. C., and Fowler, S. W.: Seasonal patterns and depth-specific trends of zooplankton fecal pellet fluxes in the Northwestern Mediterranean Sea, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I, 45, 1303–1318, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0967-0637(98)00013-2, 1998.

Chelton, D. B., Gaube, P., Schlax, M. G., Early, J. J., and Samelson, R. M.: The influence of nonlinear mesoscale eddies on near-surface oceanic chlorophyll, Science, 334, 328–332, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1208897, 2011.

Chen, F., Lao, Q., Lu, X., Wang, C., Chen, C., Liu, S., and Zhou, X.: A review of the marine biogeochemical response to typhoons, Mar. Pollut. Bull., 194, 115408, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.115408, 2023a.

Chen, K., Zhou, M., Zhong, Y., Waniek, J. J., Shan, C., and Zhang, Z.: Effects of mixing and stratification on the vertical distribution and size spectrum of zooplankton on the shelf and slope of the northern South China Sea, Front. Mar. Sci., 9, 870021, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.870021, 2022.

Chen, Q., Li, D., Feng, J., Zhao, L., Qi, J., and Yin, B.: Understanding the compound marine heatwave and low-chlorophyll extremes in the western Pacific Ocean, Front. Mar. Sci., 10:1303663, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1303663, 2023b.

Chen, Y., Lin, S., Wang, C., Yang, J., and Sun, D.: Response of size and trophic structure of zooplankton community to marine environmental conditions in the northern South China Sea in winter, J. Plankton Res., 42, 378–393, https://doi.org/10.1093/plankt/fbaa022, 2020.

Christiansen, S., Hoving, H., Schütte, F., Hauss, H., Karstensen, J., Körtzinger, A., Schröder, S., Stemmann, L., Christiansen, B., Picheral, M., Brandt, P., Robison, B., Koch, R., and Kiko, R.: Particulate matter flux interception in oceanic mesoscale eddies by the polychaete Poeobius sp., Limnol. Oceanogr., 63, 2093–2109, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10926, 2018.

Countryman, C. E., Steinberg, D. K., and Burd, A. B.: Modelling the effects of copepod diel vertical migration and community structure on ocean carbon flux using an agent-based model, Ecol. Modell., 470, 110003, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2022.110003, 2022.

Dagg, M. J., Urban-Rich, J., and Peterson, J. O.: The potential contribution of fecal pellets from large copepods to the flux of biogenic silica and particulate organic carbon in the Antarctic Polar Front region near 170° W, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 50, 675–691, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0967-0645(02)00590-8, 2003.

Dai, M., Luo, Y., Achterberg, E. P., Browning, T. J., Cai, Y., Cao, Z., Chai, F., Chen, B., Church, M. J., Ci, D., Du, C., Gao, K., Guo, X., Hu, Z., Kao, S., Laws, E. A., Lee, Z., Lin, H., Liu, Q., Liu, X., Luo, W., Meng, F., Shang, S., Shi, D., Saito, H., Song, L., Wan, X. S., Wang, Y., Wang, W., Wen, Z., Xiu, P., Zhang, J., Zhang, R., and Zhou, K.: Upper ocean biogeochemistry of the oligotrophic North Pacific subtropical gyre: From nutrient sources to carbon export, Rev. Geophys., 61, e2022RG000800, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022rg000800, 2023.

Darnis, G., Geoffroy, M., Daase, M., Lalande, C., Søreide, J. E., Leu, E., Renaud, P. E., and Berge, J.: Zooplankton fecal pellet flux drives the biological carbon pump during the winter–spring transition in a high-Arctic system, Limnol. Oceanogr., 69, 1481–1493, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.12588, 2024.

Du, C., Liu, Z., Kao, S., and Dai, M.: Diapycnal fluxes of nutrients in an oligotrophic oceanic regime: The South China Sea, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, 11510–11518, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017gl074921, 2017.

Du, F., Wang, X., Yangguang, G., Yu, J., Wang, L., Ning, J., Lin, Q., Jia, X., and Yang, S.: Vertical distribution of zooplankton in the continental slope southwest of Nansha Islands, South China Sea, Acta Oceanolog. Sin., 36, 94–103, http://www.hyxbocean.cn/en/article/id/20140613, 2014.

Early, J. J., Samelson, R. M., and Chelton, D. B.: The evolution and propagation of Quasigeostrophic ocean eddies, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 41, 1535–1555, https://doi.org/10.1175/2011jpo4601.1, 2011.

Falkowski, P. G.: Ocean Science: The power of plankton, Nature, 483, S17–S20, https://doi.org/10.1038/483S17a, 2012.

Falkowski, P. G., Ziemann, D., Kolber, Z., and Bienfang, P. K.: Role of eddy pumping in enhancing primary production in the ocean, Nature, 352, 55–58, https://doi.org/10.1038/352055a0, 1991.

Fang, W., Fang, G., Shi, P., Huang, Q., and Xie, Q.: Seasonal structures of upper layer circulation in the southern South China Sea from in situ observations, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 107, 21–23, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002jc001343, 2002.

Fischer, G., Romero, O. E., Karstensen, J., Baumann, K.-H., Moradi, N., Iversen, M., Ruhland, G., Klann, M., and Körtzinger, A.: Seasonal flux patterns and carbon transport from low-oxygen eddies at the Cape Verde Ocean Observatory: lessons learned from a time series sediment trap study (2009–2016), Biogeosciences, 18, 6479–6500, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-18-6479-2021, 2021.

Friedlingstein, P., O'Sullivan, M., Jones, M. W., Andrew, R. M., Hauck, J., Landschützer, P., Le Quéré, C., Li, H., Luijkx, I. T., Olsen, A., Peters, G. P., Peters, W., Pongratz, J., Schwingshackl, C., Sitch, S., Canadell, J. G., Ciais, P., Jackson, R. B., Alin, S. R., Arneth, A., Arora, V., Bates, N. R., Becker, M., Bellouin, N., Berghoff, C. F., Bittig, H. C., Bopp, L., Cadule, P., Campbell, K., Chamberlain, M. A., Chandra, N., Chevallier, F., Chini, L. P., Colligan, T., Decayeux, J., Djeutchouang, L. M., Dou, X., Duran Rojas, C., Enyo, K., Evans, W., Fay, A. R., Feely, R. A., Ford, D. J., Foster, A., Gasser, T., Gehlen, M., Gkritzalis, T., Grassi, G., Gregor, L., Gruber, N., Gürses, Ö., Harris, I., Hefner, M., Heinke, J., Hurtt, G. C., Iida, Y., Ilyina, T., Jacobson, A. R., Jain, A. K., Jarníková, T., Jersild, A., Jiang, F., Jin, Z., Kato, E., Keeling, R. F., Klein Goldewijk, K., Knauer, J., Korsbakken, J. I., Lan, X., Lauvset, S. K., Lefèvre, N., Liu, Z., Liu, J., Ma, L., Maksyutov, S., Marland, G., Mayot, N., McGuire, P. C., Metzl, N., Monacci, N. M., Morgan, E. J., Nakaoka, S.-I., Neill, C., Niwa, Y., Nützel, T., Olivier, L., Ono, T., Palmer, P. I., Pierrot, D., Qin, Z., Resplandy, L., Roobaert, A., Rosan, T. M., Rödenbeck, C., Schwinger, J., Smallman, T. L., Smith, S. M., Sospedra-Alfonso, R., Steinhoff, T., Sun, Q., Sutton, A. J., Séférian, R., Takao, S., Tatebe, H., Tian, H., Tilbrook, B., Torres, O., Tourigny, E., Tsujino, H., Tubiello, F., van der Werf, G., Wanninkhof, R., Wang, X., Yang, D., Yang, X., Yu, Z., Yuan, W., Yue, X., Zaehle, S., Zeng, N., and Zeng, J.: Global Carbon Budget 2024, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 17, 965–1039, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-17-965-2025, 2025.

Garçon, V. C., Oschlies, A., Doney, S. C., McGillicuddy, D. J., and Waniek, J.: The role of mesoscale variability on plankton dynamics in the North Atlantic, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 48, 2199–2226, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0967-0645(00)00183-1, 2001.

Gaube, P., Chelton, D. B., Strutton, P. G., and Behrenfeld, M. J.: Satellite observations of chlorophyll, phytoplankton biomass, and Ekman pumping in nonlinear mesoscale eddies, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 118, 6349–6370, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013jc009027, 2013.

Gaube, P., McGillicuddy, D. J., Chelton, D. B., Behrenfeld, M. J., and Strutton, P. G.: Regional variations in the influence of mesoscale eddies on near-surface chlorophyll, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 119, 8195–8220, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014jc010111, 2014.

Gervais, F., Riebesell, U., and Gorbunov, M. Y.: Changes in primary productivity and chlorophyll a in response to iron fertilization in the Southern Polar Frontal Zone, Limnol. Oceanogr., 47, 1324–1335, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2002.47.5.1324, 2002.

Goldthwait, S. A. and Steinberg, D. K.: Elevated biomass of mesozooplankton and enhanced fecal pellet flux in cyclonic and mode-water eddies in the Sargasso Sea, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 55, 1360–1377, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.01.003, 2008.

Henjes, J., Assmy, P., Klaas, C., and Smetacek, V.: Response of the larger protozooplankton to an iron-induced phytoplankton bloom in the Polar Frontal Zone of the Southern Ocean (EisenEx), Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I, 54, 774–791, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2007.02.005, 2007.

Hu, J., Kawamura, H., Hong, H., and Qi, Y.: A review on the currents in the South China Sea: seasonal circulation, South China Sea warm current and Kuroshio intrusion, J. Oceanogr., 56, 607–624, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011117531252, 2000.

Huffard, C. L., Durkin, C. A., Wilson, S. E., McGill, P. R., Henthorn, R., and Smith, K. L.: Temporally resolved mechanisms of deep-ocean particle flux and impact on the seafloor carbon cycle in the northeast Pacific, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 173, 104763, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2020.104763, 2020.

Jadhav, S. J. and Smitha, B. R.: Abundance distribution pattern of zooplankton associated with the Eastern Arabian Sea Monsoon System as detected by underwater acoustics and net sampling, Acoust. Aust., 53, 25–46, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40857-024-00336-w, 2024.

Ke, Z., Tan, Y., Huang, L., Zhang, J., and Lian, S.: Relationship between phytoplankton composition and environmental factors in the surface waters of southern South China Sea in early summer of 2009, Acta Oceanolog. Sin., 31, 109–119, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13131-012-0211-2, 2012.

Ke, Z., Tan, Y., and Huang, L.: Spatial variation of phytoplankton community from Malacca Strait to southern South China Sea in May of 2011, Acta Ecol. Sin., 36, 154–159, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chnaes.2016.03.003, 2016.

Labat, J. P., Gasparini, S., Mousseau, L., Prieur, L., Boutoute, M., and Mayzaud, P.: Mesoscale distribution of zooplankton biomass in the northeast Atlantic Ocean determined with an Optical Plankton Counter: Relationships with environmental structures, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I, 56, 1742–1756, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2009.05.013, 2009.

Lalande, C., Grebmeier, J. M., McDonnell, A. M. P., Hopcroft, R. R., O'Daly, S., and Danielson, S. L.: Impact of a warm anomaly in the Pacific Arctic region derived from time-series export fluxes, PLoS One, 16, e0255837, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255837, 2021.

Landry, M. R., Decima, M., Simmons, M. P., Hannides, C. C. S., and Daniels, E.: Mesozooplankton biomass and grazing responses to Cyclone Opal, a subtropical mesoscale eddy, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 55, 1378–1388, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.01.005, 2008.

Lehodey, P., Conchon, A., Senina, I., Domokos, R., Calmettes, B., Jouanno, J., Hernandez, O., and Kloser, R.: Optimization of a micronekton model with acoustic data, ICES J. Mar. Sci., 72, 1399–1412, https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsu233, 2015.

Lehodey, P., Titaud, O., Conchon, A., Senina, I., and Stum, J.: Zooplankton and Micronekton products from the CMEMS Catalogue for better monitoring of Marine Resources and Protected Species, EGU General Assembly 2020, Online, 4–8 May 2020, EGU2020-9016, https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu2020-9016, 2020.

Li, H., Wiesner, M. G., Chen, J., Ling, Z., Zhang, J., and Ran, L.: Long-term variation of mesopelagic biogenic flux in the central South China Sea: Impact of monsoonal seasonality and mesoscale eddy, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I, 126, 62–72, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2017.05.012, 2017.

Li, J., Liu, Z., Lin, B., Zhao, Y., Cao, J., Zhang, X., Zhang, J., Ling, C., Ma, P., and Wu, J.: Zooplankton fecal pellet characteristics and contribution to the deep-sea carbon export in the southern South China Sea, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 127, e2022JC019412, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022jc019412, 2022.

Li, J., Liu, Z., Lin, B., Zhao, Y., Zhang, X., Cao, J., Zhang, J., and Song, H.: Zooplankton fecal pellet flux and carbon export: The South China Sea record and its global comparison, Global Planet. Change, 245, 104657, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2024.104657, 2025.

Li, Y. and Tang, D.: Tropical cyclone Wind Pump induced chlorophyll-a enhancement in the South China Sea: A comparison of the open sea and continental shelf, Front. Mar. Sci., 9, 1039824, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.1039824, 2022.

Liang, Z., Xing, T., Wang, Y., and Zeng, L.: Mixed layer heat variations in the South China Sea observed by Argo float and reanalysis data during 2012–2015, Sustainability, 11, 5429, https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195429, 2019.

Liu, J., Li, B., Chen, W., Li, J. and Yan, J.: Evaluation of ERA5 wave parameters with in situ data in the South China Sea, Atmosphere, 13, 935, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13060935, 2022.

Liu, Z., Zhao, Y., Colin, C., Stattegger, K., Wiesner, M. G., Huh, C.-A., Zhang, Y., Li, X., Sompongchaiyakul, P., You, C.-F., Huang, C.-Y., Liu, J. T., Siringan, F. P., Le, K. P., Sathiamurthy, E., Hantoro, W. S., Liu, J., Tuo, S., Zhao, S., Zhou, S., He, Z., Wang, Y., Bunsomboonsakul, S., and Li, Y.: Source-to-sink transport processes of fluvial sediments in the South China Sea, Earth Sci. Rev., 153, 238–273, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.08.005, 2016.

Lu, H., Zhao, X., Sun, J., Zha, G., Xi, J., and Cai, S.: A case study of a phytoplankton bloom triggered by a tropical cyclone and cyclonic eddies, PLoS One, 15, e0230394, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230394, 2020.

Marshal, W., Roseli, N., Md Amin, R., and Mohd Akhir, M. F.: Long-term biogeochemical variations in the southern South China Sea and adjacent seas: A model data analysis, J. Sea Res., 204, 102573, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seares.2025.102573, 2025.

Martin, A. P. and Richards, K. J.: Mechanisms for vertical nutrient transport within a North Atlantic mesoscale eddy, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 48, 757–773, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0967-0645(00)00096-5, 2001.

McGillicuddy, D. J., Johnson, R., Siegel, D. A., Michaels, A. F., Bates, N. R., and Knap, A. H.: Mesoscale variations of biogeochemical properties in the Sargasso Sea, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 104, 13381–13394, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999jc900021, 1999.

McGillicuddy, D. J., J., Anderson, L. A., Bates, N. R., Bibby, T., Buesseler, K. O., Carlson, C. A., Davis, C. S., Ewart, C., Falkowski, P. G., Goldthwait, S. A., Hansell, D. A., Jenkins, W. J., Johnson, R., Kosnyrev, V. K., Ledwell, J. R., Li, Q. P., Siegel, D. A., and Steinberg, D. K.: Eddy/wind interactions stimulate extraordinary mid-ocean plankton blooms, Science, 316, 1021–1026, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1136256, 2007.

Menschel, E. and Gonzalez, H.: Carbon and calcium carbonate export driven by appendicularian faecal pellets in the Humboldt current system off Chile, Sci. Rep., 9, 16501, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52469-y, 2019.

Nowicki, M., DeVries, T., and Siegel, D. A.: Quantifying the carbon export and sequestration pathways of the Ocean's Biological Carbon Pump, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 36, e2021GB007083, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GB007083, 2022.

Parker, C. E.: Gulf stream rings in the Sargasso Sea, Deep-Sea Res. Oceanogr. Abstr., 18, 981–993, https://doi.org/10.1016/0011-7471(71)90003-9, 1971.

Qu, T., Du, Y., Gan, J., and Wang, D.: Mean seasonal cycle of isothermal depth in the South China Sea, J. Geophys. Res., 112, C02020, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JC003583, 2007.

Ramaswamy, V., Sarin, M. M., and Rengarajan, R.: Enhanced export of carbon by salps during the northeast monsoon period in the northern Arabian Sea, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 52, 1922–1929, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2005.05.005, 2005.

Resplandy, L., Lévy, M., and McGillicuddy, D. J.: Effects of eddy-driven subduction on Ocean Biological Carbon Pump, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 33, 1071–1084, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018gb006125, 2019.

Richardson, P. L.: Gulf stream ring trajectories, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 10, 90–104, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0485(1980)010<0090:Gsrt>2.0.Co;2, 1980.

Rocha-Díaz, F. A., Coria-Monter, E., Monreal-Gómez, M. A., Salas-De-León, D. A., and Durán-Campos, E.: Copepod groups distribution in a cyclonic eddy in Bay of La Paz, Gulf of California, Mexico, during summer 2009, Pan-Am. J. Aquat. Sci., 19, 6–16, https://doi.org/10.54451/PanamJAS.19.1.6, 2023.

Roman, M., Smith, S., Wishner, K., Zhang, X., and Gowing, M.: Mesozooplankton production and grazing in the Arabian Sea, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 47, 1423–1450, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0967-0645(99)00149-6, 2000.

Rühl, S. and Möller, K. O.: Storm events alter marine snow fluxes in stratified marine environments, Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci., 302, 108767, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2024.108767, 2024.

Schultes, S., Verity, P. G., and Bathmann, U.: Copepod grazing during an iron-induced diatom bloom in the Antarctic Circum- polar Current (EisenEx): I. Feeding patterns and grazing impact on prey populations, J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol., 338, 16–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2006.06.028, 2006.

Shatova, O., Koweek, D., Conte, M. H., and Weber, J. C.: Contribution of zooplankton fecal pellets to deep ocean particle flux in the Sargasso Sea assessed using quantitative image analysis, J. Plankton Res., 34, 905–921, https://doi.org/10.1093/plankt/fbs053, 2012.

Shaw, P. T. and Chao, S. Y.: Surface circulation in the South China Sea, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I, 41, 1663–1683, https://doi.org/10.1016/0967-0637(94)90067-1, 1994.

Siegel, D. A., McGillicuddy, D. J., and Fields, E. A.: Mesoscale eddies, satellite altimetry, and new production in the Sargasso Sea, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 104, 13359–13379, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999jc900051, 1999.

Siegel, D. A., Court, D. B., Menzies, D. W., Peterson, P., Maritorena, S., and Nelson, N. B.: Satellite and in situ observations of the bio-optical signatures of two mesoscale eddies in the Sargasso Sea, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 55, 1218–1230, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.01.012, 2008.

Siegel, D. A., Peterson, P., McGillicuddy, D. J., Maritorena, S., and Nelson, N. B.: Bio-optical footprints created by mesoscale eddies in the Sargasso Sea, Geophys. Res. Lett., 38, L13608, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011gl047660, 2011.

Siegel, D. A., Buesseler, K. O., Doney, S. C., Sailley, S. F., Behrenfeld, M. J., and Boyd, P. W.: Global assessment of ocean carbon export by combining satellite observations and food-web models, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 28, 181–196, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013GB004743, 2014.

Siegel, D. A., DeVries, T., Cetinic, I., and Bisson, K. M.: Quantifying the ocean's Biological Pump and its carbon cycle impacts on global scales, Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci., 15, 329–356, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-040722-115226, 2023.

Smith, A. J. R., Wotherspoon, S., Ratnarajah, L., Cutter, G. R., Macaulay, G. J., Hutton, B., King, R., Kawaguchi, S., and Cox, M. J.: Antarctic krill vertical migrations modulate seasonal carbon export, Science, 387, eadq5564, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adq5564, 2025.

Stamieszkin, K., Pershing, A. J., Record, N. R., Pilskaln, C. H., Dam, H. G., and Feinberg, L. R.: Size as the master trait in modeled copepod fecal pellet carbon flux, Limnol. Oceanogr., 60: 2090–2107, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10156, 2015.

Steinberg, D. K. and Landry, M. R.: Zooplankton and the ocean carbon cycle, Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci., 9, 413–444, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-010814-015924, 2017.

Strzelecki, J., Koslow, J. A., and Waite, A.: Comparison of mesozooplankton communities from a pair of warm- and cold-core eddies off the coast of Western Australia, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 54, 1103–1112, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2007.02.004, 2007.

Subrahmanyam, B., Rao, K. H., Srinivasa Rao, N., Murty, V. S. N., and Sharp, R. J.: Influence of a tropical cyclone on chlorophyll-a concentration in the Arabian Sea, Geophys. Res. Lett., 29, 2065, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002gl015892, 2002.

Sun, L., Yang, Y., Xian, T., Lu, Z., and Fu, Y.: Strong enhancement of chlorophyll a concentration by a weak typhoon, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 404, 39–50, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps08477, 2010.

Thompson, B., and Tkalich, P.: Mixed layer thermodynamics of the Southern South China Sea, Clim. Dyn., 43, 2061–2075, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-013-2030-3, 2014.

Trinh, N. B., Herrmann, M., Ulses, C., Marsaleix, P., Duhaut, T., To Duy, T., Estournel, C., and Shearman, R. K.: New insights into the South China Sea throughflow and water budget seasonal cycle: evaluation and analysis of a high-resolution configuration of the ocean model SYMPHONIE version 2.4, Geosci. Model Dev., 17, 1831–1867, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-17-1831-2024, 2024.

Turner, J. T.: Zooplankton fecal pellets, marine snow and sinking phytoplankton blooms, Aquat. Microb. Ecol., 27, 57–102, https://doi.org/10.3354/ame027057, 2002.

Turner, J. T.: Zooplankton fecal pellets, marine snow, phytodetritus and the ocean's biological pump, Prog. Oceanogr., 130, 205–248, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2014.08.005, 2015.

Turner, J. T. and Ferrante, J. G.: Zooplankton fecal pellets in aquatic ecosystems, BioScience, 29, 670–677, https://doi.org/10.2307/1307591, 1979.

van Ruth, P. D., Ganf, G. G., and Ward, T. M.: The influence of mixing on primary productivity: A unique application of classical critical depth theory, Prog. Oceanogr., 85, 224–235, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2010.03.002, 2010.

Wahyudi, A. J., Triana, K., Masumoto, Y., Rachman, A., Firdaus, M. R., Iskandar, I., and Meirinawati, H.: Carbon and nutrient enrichment potential of South Java upwelling area as detected using hindcast biogeochemistry variables, Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci., 59, 102802, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsma.2022.102802, 2023.

Wang, P. and Li, Q.: The South China Sea: Paleoceanography and Sedimentology., vol. 13 of Developments in Paleoenvironmental Research, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4020-9745-4, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9745-4, 2009.

Wang, H., Liu, Z., Li, J., Lin, B., Zhao, Y., Zhang, X., Cao, J., Zhang, J., Song, H., and Wang, W.: Sinking fate and carbon export of zooplankton fecal pellets: insights from time-series sediment trap observations in the northern South China Sea, Biogeosciences, 20, 5109–5123, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-20-5109-2023, 2023.

Wang, L., Du, F., Li, Y., Ning, J., and Guo, W.: Community characteristics of pelagic copepods in Nansha area before and after onset of Southwest Monsoon, South China Fisheries Science, 11, 47–55, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.2095-0780.2015.05.006, 2015.

Wang, Z., Liu, L., Tang, Y., Li, A., Liu, C., Xie, C., Xiao, L., and Lu, S.: Phytoplankton community and HAB species in the South China Sea detected by morphological and metabarcoding approaches, Harmful Algae, 118, 102297, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2022.102297, 2022.

Wilson, S. E., Steinberg, D. K., and Buesseler, K. O.: Changes in fecal pellet characteristics with depth as indicators of zooplankton repackaging of particles in the mesopelagic zone of the subtropical and subarctic North Pacific Ocean, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 55(14–15), 1636–1647, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.04.019, 2008.

Wong, G. T. F., Ku, T.-L., Mulholland, M., Tseng, C.-M., and Wang, D.-P.: The SouthEast Asian Time-series Study (SEATS) and the biogeochemistry of the South China Sea – An overview, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 54, 1434–1447, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2007.05.012, 2007.

Xiu, P. and Chai, F.: Modeled biogeochemical responses to mesoscale eddies in the South China Sea, J. Geophys. Res., 116, C10006, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010jc006800, 2011.

Yao, Y. and Wang, C.: Variations in summer marine heatwaves in the South China Sea, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 126, e2021JC017792, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JC017792, 2021.

Zhai, R., Huang, C., Yang, W., Tang, L., and Zhang, W.: Applicability evaluation of ERA5 wind and wave reanalysis data in the South China Sea, J. Ocean. Limnol., 41, 495–517, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00343-022-2047-8, 2023.

Zhang, J., Li, H., Xuan, J., Wu, Z., Yang, Z., Wiesner, M. G., and Chen, J.: Enhancement of mesopelagic sinking particle fluxes due to upwelling, aerosol deposition, and monsoonal influences in the northwestern South China Sea, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 124, 99–112, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018jc014704, 2019.

Zhang, J., Li, H., Wiesner, M. G., Eglinton, T. I., Haghipour, N., Jian, Z., and Chen, J.: Carbon isotopic constraints on basin-scale vertical and lateral particulate organic carbon dynamics in the northern South China Sea, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 127, e2022JC018830, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022jc018830, 2022.

Zhao, H., Tang, D., and Wang, Y.: Comparison of phytoplankton blooms triggered by two typhoons with different intensities and translation speeds in the South China Sea, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 365, 57–65, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps07488, 2008.

Zhao, H., Pan, J., Han, G., Devlin, A. T., Zhang, S., and Hou, Y.: Effect of a fast-moving tropical storm Washi on phytoplankton in the northwestern South China Sea, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 122, 3404–3416, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016jc012286, 2017.

Zhu, G., Ning, X., Cai, Y., Liu, Z., and Liu, C.: Studies on species composition and abundance distribution of phytoplankton in the South China Sea, Acta Oceanolog. Sin., S2, 8–23, 2003 (in Chinese).