the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Glaciogenic iron transport pathways to the Kerguelen offshore phytoplankton bloom

Alex Nalivaev

Francesco d'Ovidio

Laurent Bopp

Maristella Berta

Louise Rousselet

Clara Azarian

Stéphane Blain

In contrast to the average low biological productivity across most of the Southern Ocean, the Kerguelen region is one of the few subantarctic regions to host massive phytoplankton blooms, extending hundreds of kilometers offshore. These blooms play a crucial role in the Southern Ocean carbon cycle and support a diverse ecosystem of patrimonial and commercial significance. The Kerguelen blooms are associated with a subsurface iron source that supplies surface waters both on the Plateau and offshore. The mechanisms of iron enrichment have only been partially elucidated. The resuspension of iron-enriched sediments over the Plateau, transported offshore by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, is one mechanism that has been studied in the past years. However, the Kerguelen Islands host a glacier system, and two of the outlet glaciers of Kerguelen's Cook Ice Cap are likely to provide iron-enriched lithogenic material downstream to the coastal waters of the Golfe des Baleiniers. Whether the circulation is able to connect the glacier outlets to the open ocean, and how much of the offshore bloom extension can be reached by glaciogenic iron is not known. Using in situ and satellite data, including observations from the recent SWOT satellite mission, we reconstruct the horizontal advection of iron and show that glaciogenic iron supply reaches up to one third of the spatial extent of the offshore bloom onset. These findings have significant implications in the context of ongoing ice cap mass loss and glacier retreat observed on Kerguelen and other Southern Ocean islands under climate change.

- Article

(6468 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Phytoplankton are a key component of the biogeochemical cycles of the oceans and serve as a backbone of marine trophic webs. Phytoplankton growth is subject to nutrient limitation, being confined to the euphotic surface layer which is regularly depleted of nutrients (Sarmiento and Gruber, 2006). Ocean currents influence phytoplankton growth and distribution in particular by supplying nutrients vertically or horizontally, thus acting as a “dynamic landscape” (Lévy et al., 2015). Therefore, when studying the distribution, abundance and phenology of primary producers, particular attention must be paid to the circulation processes that enable nutrient supply (Lévy, 2008). While most of the ocean's primary producers are limited by macronutrients (nitrate and/or phosphate), about 25 % of the global ocean is iron-limited with high concentrations of macronutrients (Boyd and Ellwood, 2010). Indeed iron, a trace metal present in very low concentrations in the ocean (10−9 to 10−12 mol L−1), is required for cellular processes such as photosynthesis, respiration or macronutrient utilization (Twining and Baines, 2013; Moore et al., 2013; Lohan and Tagliabue, 2018). The Southern Ocean is the largest High Nutrient, Low Chlorophyll (HNLC) region of the world's ocean (Boyd et al., 2007; Martin et al., 1990). The limitation of its primary productivity by iron has been attested by numerous artificial (e.g. Boyd et al., 2000; Martin et al., 2013) and natural iron fertilization experiments (e.g. Blain et al., 2007, 2008 or Bowie et al., 2015 at Kerguelen; Planquette et al., 2011 near Crozet Islands; Boyd et al., 2005 and Ellwood et al., 2014 east of New Zealand; Bowie et al., 2009 south of Tasmania; or Korb et al., 2008 and Venables and Meredith, 2009 in South Georgia). Indeed, contrasting with the average low biological production of the Southern Ocean, some of its regions, benefiting from external iron supply, host massive seasonal phytoplankton blooms. If the condition of sufficient iron is met, the removal of light limitation in spring can stimulate the growth of primary producers – leading to a bloom (Pellichero et al., 2020). Biological consumption can then rapidly deplete the nutrient, ending the bloom. This raised the question of the external iron sources and of their relative contributions to the fertilization of Southern Ocean blooms (Tagliabue et al., 2017). In a traditional view, iron was considered to be supplied to the ocean through either atmospheric dust deposition (Johnson et al., 1997; Jickells et al., 2005), continental margin sediment (Elrod et al., 2004; Moore and Braucher, 2008), or hydrothermal vents (Tagliabue et al., 2010) inputs. In the Southern Ocean, the importance of sedimentary iron has been indicated by model-based (Tagliabue et al., 2009, 2014), satellite-based (Ardyna et al., 2017) and in situ-based studies (Chever et al., 2010; Bowie et al., 2015). Hydrothermal vents have been shown to contribute to sustaining Southern Ocean blooms and ecosystems above ocean ridges (Tagliabue et al., 2010; Ardyna et al., 2019; Sergi et al., 2020). Although long overlooked, continental ice shelves, icebergs, and sea ice have gained interest and are now considered as significant sources of iron (Boyd and Ellwood, 2010; Raiswell et al., 2018; Krause et al., 2024). Glaciers and ice sheets have been shown to deliver iron, extracted from the continental bedrock by erosion, to coastal and open ocean waters through basal melt (Raiswell et al., 2006, 2008; Gerringa et al., 2012; Bhatia et al., 2013; Kanna et al., 2020). Phytoplankton blooms have been shown to colocalize with water discharge from glaciers, and attributed to iron inputs (Arrigo et al., 2015, 2017). In some cases, the influence of glacial iron inputs has been shown to extend far beyond the coastal area (e.g. Arrigo et al., 2015). However, in the Southern Ocean, most studies have focused on the impact of Antarctic ice sheets and sea ice on primary productivity near the Antarctic shelf (e.g. Schallenberg et al., 2016; Arrigo et al., 2017; Person et al., 2021). The contribution to Southern Ocean primary productivity of glaciers located on Southern Ocean islands has thus been poorly studied and remains largely unknown (see Van Der Merwe et al., 2019, as well as Holmes et al., 2019, 2020 for some of the few studies at subantarctic latitudes, on Heard Island).

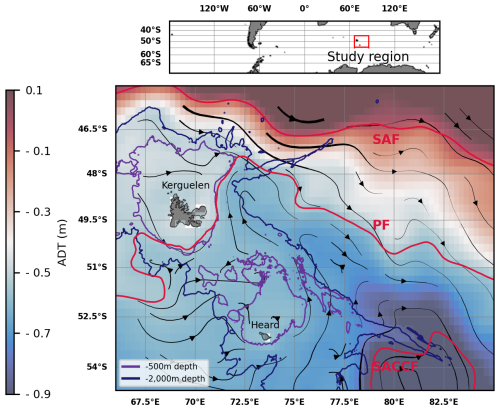

Located in the Indian section of the Southern Ocean, the region surrounding the French Southern Lands of Kerguelen illustrates these scientific questions. The Kerguelen Plateau is a northwest-southeast topographic structure of volcanic origin and of approximately 500 meters depth, surrounding the Kerguelen Islands to its north and the Heard and McDonald islands to its south (Fig. 1). The Kerguelen Plateau acts as a topographic barrier to the strong, eastward-flowing Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC; Donohue et al., 2016). As it approaches the Plateau, two thirds of the ACC is deflected north of the Kerguelen Islands, transporting Sub-Antarctic Surface Waters (SASW), but other branches of the ACC flow between the Kerguelen and Heard Islands, transporting Winter Waters (following the Polar Front), or further south of Heard Island (in the form of the Fawn Trough Current; Park et al., 2008, 2014; Pauthenet et al., 2018).

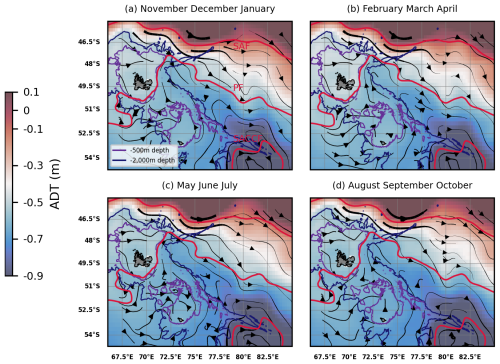

Figure 1Absolute dynamic topography (ADT) and streamlines derived from altimetry (DUACS multisatellite product) in the Kerguelen region, 2004–2023 climatology of February to April months. The arrow linewidth is proportional to the speed of geostrophic currents. Bathymetric contours (500 and 2000 m depth) are shown. A climatology of some of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) fronts is shown in red: the Subantarctic Front (SAF), the Polar Front (PF), and the Southern ACC front (SACCF) (constructed from mean dynamic topography, source: Park and Durand, 2019; Park et al., 2019). The three other seasonal climatologies were found to be similar and are shown in Appendix A.

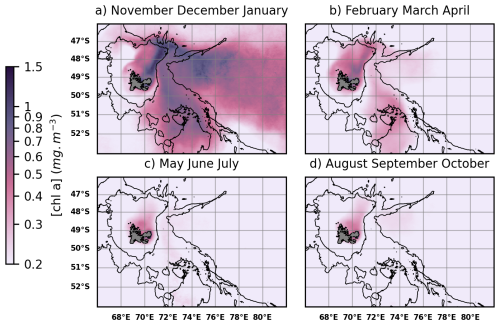

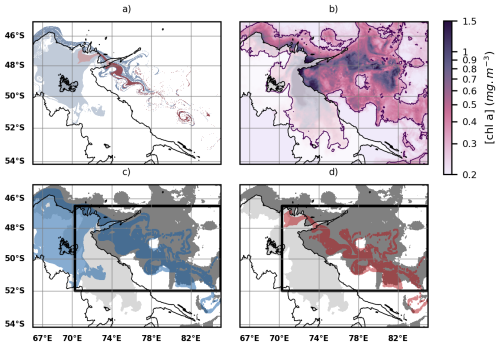

The Kerguelen region is home to massive seasonal blooms that can be divided into two sub-regions based on bathymetry, and therefore, on distance from continental iron sources. On one hand, a significant bloom develops over the Plateau, i.e. an area with shallow bathymetry (less than 500 m depth) (Blain et al., 2007; Mongin et al., 2008). On the other hand, a massive bloom develops east of the Islands, over the open ocean, beyond the continental margin and slope (i.e. approximately beyond 2000 m depth). We hereafter refer to these blooms as coastal and offshore blooms, respectively. The spatial extension and seasonality of these blooms are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2Surface chlorophyll a (Chl a) concentration over the Kerguelen region, derived from ocean colour satellite products (GlobColour multisatellite product), 2004–2023 seasonal climatologies. Bathymetric contours (500 and 2000 m depth) are shown. From November to January (Austral spring and summer) (a), massive coastal (< 500 m depth) and offshore (> 2000 m depth) phytoplankton blooms are observable. From February to April (late summer and autumn) (b), a less intense bloom is localized over the Northern Plateau. During the rest of the year (c, d) the biological productivity of the region is low.

The origin of the iron fertilization of the Kerguelen coastal and offshore blooms has been addressed by several successive in situ experiments. Cruise ANTARES 3/F-JGOFS, conducted in October 1995, concluded that iron from rivers and coastal weathering, as well as from the continental margin sediments, supplied the area of the coastal bloom (Blain et al., 2000; Bucciarelli et al., 2001). This observation was confirmed and refined by subsequent cruises. KEOPS1 (Kerguelen Ocean and Plateau Compared Study 1) conducted in January 2005 (Blain et al., 2007, 2008) led to the first iron budget over the area of the coastal bloom (Chever et al., 2010). KEOPS2, conducted from October to November 2011 highlighted the lateral heterogeneity of iron budgets (Bowie et al., 2015; Quéroué et al., 2015; Van Der Merwe et al., 2015). In addition, offshore phytoplankton was shown to be fertilized through a lateral transport of iron from the Plateau, during austral spring and summer. In particular, d'Ovidio et al. (2015) demonstrated the significant contribution of horizontal advection processes to the transport of iron from the shallow water areas of Kerguelen to the offshore bloom. Importantly, KEOPS2 put forward the hypothesis of an iron supply from glacio-fluvial processes on Kerguelen (Van Der Merwe et al., 2015).

The Kerguelen Islands indeed present several glaciers discharging into its coastal waters. On the main island of the archipelago, Grande Terre, the Cook Ice Cap, covering ca. 400 km2 in 2020, features about a dozen outlet glaciers (Verfaillie et al., 2021). In particular, north of the Polar Front, the weathering and ice melting of Naumann and Valot glaciers discharging into the Golfe des Baleiniers are likely to provide iron-enriched lithogenic matter to the coastal waters of the gulf. More precisely, as the glaciers are land-terminating (Verfaillie et al., 2021), the iron sourced by glacial erosion is transported further by riverine systems along the land-to-sea pathway, thereby influencing iron biogeochemistry. Hereafter, we will refer to iron inputs influenced by glacial processes as “glaciogenic iron”. Recent findings suggest that glaciogenic iron can be bioavailable: for instance, Thoppil et al. (2025) discovered that it stimulates bacterial activity, which is a first step in making it accessible to phytoplankton. However, the contribution of this glaciogenic iron input to both coastal and offshore ecosystems is left to be understood. More specifically, as part of the MARGOCEAN project, this study reconstructs the fine scale (1–100 km, days-months) iron supply pathways and bloom patchiness from surface drifters and remote sensing data, thus complementing the in situ biogeochemical measurements carried out during the MARGOCEAN cruise, which was held from January to February 2024 aboard the RV Marion Dufresne (https://doi.org/10.17600/18002958, Blain and Obernosterer, 2024). Our study in particular aims at answering the following question: to what extent does glaciogenic iron supply over the Golfe des Baleiniers reach the region of the offshore phytoplankton bloom? In order to achieve this, we sample the coastal circulation in the Golfe des Baleiniers by using surface drifters deployed during the MARGOCEAN cruise. Away from the coast, we reconstruct plumes of horizontal iron transport using a Lagrangian methodology combined with remote sensed ocean color and altimetry data (Ardyna et al., 2017; d'Ovidio et al., 2015). We also use this study as a first test case for the novel high resolution SWOT (Surface Water and Ocean Topography; Morrow et al., 2019) altimetry mission, and test whether SWOT observations reduce altimetry biases for fine-scale features (Appendix B).

2.1 Satellite products

This study combines the use of altimetry and ocean color data, providing a thorough representation of Kerguelen circulation and phytoplankton patchiness. Geostrophic velocities and surface chlorophyll a concentrations (Chl a) are extracted from different products distributed by the European Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS) and the satellite altimetry database AVISO (CNES).

2.1.1 Altimetry

Regional sea surface heights and geostrophic surface currents are obtained through an altimetry multi-satellite product (SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_L4_MY_008_047, DOI: https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00148, SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_L4_MY_008_047, 2024) produced by the CNES-CLS operational system DUACS (Data Unification and Altimeter Combination System, https://duacs.cls.fr/, last access: 18 September 2024). The product processes data from several altimeter missions and has spatial and temporal resolutions of, respectively, ° and one day. DUACS altimetry has a process resolution of ∼ 150 km in wavelength (∼ 70 km eddy diameter; Morrow et al., 2023). The use of DUACS altimetry to study mesoscale iron transport pathways at regional scales has been validated by previous studies (e.g. d'Ovidio et al., 2015 over Kerguelen). DUACS geostrophic velocities are extracted over the period 2014–2023.

Furthermore, this study makes use of the recently launched SWOT satellite, developed through a CNES-NASA collaboration (Morrow et al., 2023). Thanks to a novel SAR-In radar interferometric wide-swath technology, SWOT enables the visualization of structures of 7–15 km diameter (15–30 km wavelength): its resolution is thus 5 to 10 times greater than DUACS (Morrow et al., 2019, 2023). We use L4 MIOST SWOT products (Ubelmann et al., 2021; Ballarotta et al., 2023) at a horizontal resolution of 2 km as inputs in the Lagrangian model detailed below, and compare the obtained results with DUACS (Appendix B). Similarly to DUACS, MIOST processes data from several altimetry missions, but also includes SWOT swath data.

2.1.2 Ocean colour

Satellite surface Chl a concentrations are analyzed with the multimission Copernicus Global Ocean Color dataset (OCEANCOLOUR_GLO_BGC_L3_MY_009_103, DOI: https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00280, OCEANCOLOUR_GLO_BGC_L3_MY_009_103, 2024) produced by ACRI-ST. Copernicus GlobColour product has temporal and spatial resolutions of, respectively, one day and 4 km. L3 processing level products are extracted over the period 2004–2023 so as to draw daily chlorophyll climatologies of the Kerguelen coastal and offshore blooms. L3 products enable to preserve the signal of fine scale chlorophyll variability, buffered by interpolation algorithms of higher processing levels, while the use of a long period for the climatology statistically reduces the cloud-covered area. Analyses are performed over a wide area encapsulating the offshore bloom (66–90° E, 45–55° S). Fine scale filamentous chlorophyll structures are observed over the Golfe des Baleiniers both with GlobColour products and with Sentinel 3A and 3B data from Ocean and Land Color Instrument (OLCI, Level 2 WFR, Copernicus Sentinel data 2023), the latter allowing a higher spatial resolution (∼ 300 m). The products are generated and maintained by EUMETSAT. The high resolution S3 data is extracted on a daily basis over the months of January to March 2024, thus matching the period of the MARGOCEAN cruise. When comparing chlorophyll concentrations over two areas (see Results, Sect. 3.1), we use the Brunner-Munzel statistical test, also known as the generalized Wilcoxon test. This nonparametric test that aims to determine whether, for two randomly selected samples X and Y of two populations, the probability of X being greater than Y is equal to the probability of Y being greater than X (null hypothesis). This test has previously been applied to the comparison of chlorophyll concentrations (e.g. Lévy et al., 2025).

2.2 Surface CARTHE drifters

The use of satellite altimetry is combined with that of 10 CARTHE drifters (Consortium for Advanced Research on Transport of Hydrocarbon in the Environment; Novelli et al., 2017, 2018), deployed during the MARGOCEAN cruise. The use of surface drifters is a common method to study fine-scale circulation processes, especially when trying to capture submesoscale motions close to the surface and below the resolution of altimetry. The use of surface drifters was first applied to study the submesoscale-driven dispersion of contaminants (e.g. Poje et al., 2014; Novelli et al., 2018; D'Asaro et al., 2020). Subsequently, drifters have been used to sample submesoscale dynamics (Novelli et al., 2017; Schroeder et al., 2011; Berta et al., 2015). In this work, CARTHE drifters are chosen for their compactness and ease of use. CARTHE have been shown from tank tests to be consistent with the flow in the upper 0.60 m, and their toroidal shape was designed to minimize windage (Novelli et al., 2017). The CARTHE drifters were deployed in the Golfe des Baleiniers following two transects, orthogonal to the coastal iron plume and consisting of 5 drifters each, on 6 and 12 February 2024 respectively (Berta et al., 2024). The trajectories of the drifters, equipped with a GPS transmitter, are monitored. Inertial oscillations are filtered out using a running mean (Berta et al., 2015), with a time window equal to the inertial period at Kerguelen latitudes (ie, approximately 16 h). Previous studies have shown that the average transport within the mixed layer is better approximated by Lagrangian methods using surface geostrophic velocities (rather than total velocities) (Lehahn et al., 2007, 2018). Given that, especially at Kerguelen latitudes, wind stress is a major component driving the circulation of the surface layer, the Ekman velocity is subtracted from the total drifter velocity in order to estimate drifter geostrophic velocities. Indeed, geostrophic velocities integrate information about the circulation in the mixed layer (where the iron is distributed), while the influence of the Ekman component is limited to the surface layer, and strongly decreases with depth (Venables and Meredith, 2009). Daily, surface modeled Ekman velocities are obtained from the Copernicus-GlobCurrent product (MULTIOBS_GLO_PHY_MYNRT_015_003, DOI: https://doi.org/10.48670/mds-00327, MULTIOBS_GLO_PHY_MYNRT_015_003, 2024). DUACS geostrophic velocities are compared to the drifters' geostrophic velocities in the study region (Appendix C).

2.3 Lagrangian model

2.3.1 A Lagrangian model of iron delivery from the Golfe des Baleiniers to the offshore bloom

Using surface geostrophic velocity fields derived from DUACS altimetry, a Lagrangian experiment of tracers' advection is performed using the LAMTA (LAgrangian Manifolds Tracking Algorithm) software (Rousselet et al., 2025). Lagrangian trajectories are derived by applying a fourth-order Runge-Kutta scheme with a time step of 6 h. Virtual particles are initialized over a regular grid of 0.01° horizontal resolution (66–90° E, 45–55° S). Following the methodology detailed in Ardyna et al. (2017), each particle in the study region is advected backwards in time in order to check their potential origin from an iron source. The time of integration is set to 60 d, which is in our experiments the order of magnitude of the duration required for glaciogenic and Plateau iron to reach the region of the offshore bloom (this duration is consistent with the results of d'Ovidio et al., 2015). Among these trajectories, we are particularly interested in particles originating from iron sources in order to determine iron delivery pathways. Thus, in each advection experiment, the parcels that are found to originate from the glaciogenic and Plateau iron sources (detailed in the Results section) are given a timestamp indicating the duration, in days, of their last contact with the source. Due to iron removal processes (e.g. scavenging, complexation, or biological consumption), the iron content of the water parcels that we advect decreases over time. In this study, we account for the combined impact of these processes on the iron content of the water parcels by applying a first-order exponential decay to the iron concentration over time, as described by d'Ovidio et al. (2015).

In this formula, C0 is the initial iron concentration at the iron sources (i.e. the glacier outflow or the Plateau), and is undetermined (its estimation is one of the objectives of the MARGOCEAN cruise); t is the integration time (i.e. the time since the water parcel left the iron source), and C is the iron concentration at time t in the water parcel. We use the iron removal rate λ, which was estimated during KEOPS2 and reported in d'Ovidio et al. (2015) as λ=0.1 d−1, summing the contributions from all biotic and abiotic iron removal processes. We opted for the KEOPS2 estimation because the cruise was explicitly designed to relate removal rates to advective pathways, and was conducted during the same season as our advection experiments (see the paragraph below). Using the above approximation and the estimation of λ=0.1 d−1, the iron content of water parcels is reduced to approximately 0.25 % of the initial iron concentration at the source after an integration time of 60 d.

2.3.2 Comparison with surface chlorophyll maps

Comparisons are performed between the areas of the iron plumes and the offshore bloom over a fraction of the study region (70.25–85° E, 46.5–52° S) which includes most of the offshore bloom and remains close to the Kerguelen Plateau and consequently to the continental iron sources. We calculate the spatial contribution of iron deliveries to the extent of offshore blooms. To do this, we focus our analysis on the early phytoplankton blooms. For each year between 2014 and 2023, we identify a period of 15 d corresponding to the onset of the offshore bloom: using the phenology of the offshore bloom in each year, we determine the date on which the offshore chlorophyll concentration exceeds the annual average chlorophyll concentration. We then consider a period of 10 d centered on this date as the period of the onset of the offshore bloom, later defined as the early offshore phytoplankton bloom. The dates of the onset of the offshore bloom range from 18 October to 12 November. The iron plumes are advected for 60 d prior to the onset of the offshore bloom. Focusing on the period of the early offshore phytoplankton bloom allows us to neglect passive advection of phytoplankton cells as a mechanism responsible for the spatial extent of the bloom (d'Ovidio et al., 2010).

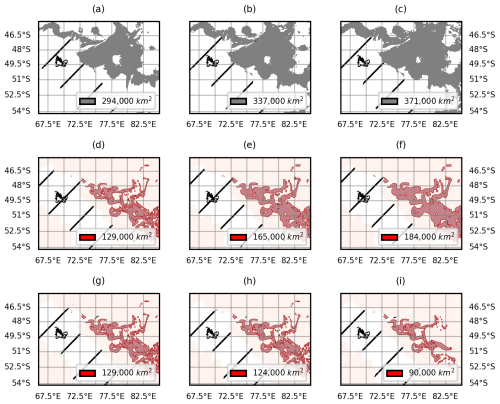

Both iron delivery maps and surface chlorophyll concentration maps are converted into binary grids. A relative chlorophyll concentration threshold is used to define the area of the offshore bloom. The choice of relative thresholds rather than absolute chlorophyll concentration thresholds is justified by the high interannual variability in the magnitude of the offshore bloom. We test three relative threshold choices: the median, 60th and 70th percentiles of chlorophyll concentrations averaged over a period of 15 d centered on the date of the onset of the offshore bloom. We thus conduct a sensitivity test on our definition of the offshore bloom area. Regarding iron delivery maps, the current state of scientific knowledge on iron limitation does not allow us to identify a clear threshold for iron content below which the impact of iron supply on phytoplankton cells can be considered negligible. Therefore, we conduct tests on three relative iron content thresholds (0.25 %, 0.3 % and 0.5 % of the initial concentration at the source), on the assumption that water parcels with lower relative iron content did not supply enough iron to be considered significant for phytoplankton ecosystems. Additionally, the iron plumes are horizontally extrapolated to the nearest n pixels (with a pixel size of 0.01° of longitude and latitude) and three extrapolation width values for the iron plumes are tested (namely 0.1, 0.16 and 0.2° squares centered on the initial iron trajectories). In each case, we compute the match between the iron plume and the offshore bloom extension. An ensemble of 27 sensitivity tests is thus perfomed, allowing a measure of the uncertainty of the statistics (an illustration of the sensitivity tests is provided in Appendix D).

The iron and chlorophyll fields are compared using a correlation matrix. We define a true prediction or true positive as a pixel that is part of both the iron plume and the offshore bloom. Conversely, we define a false prediction or false positive as a pixel that is part of the iron plume but not part of the offshore bloom. Furthermore, we consider that a pixel belonging to the offshore bloom is reached by an iron supply plume if it also belongs to the extrapolated iron plumes. Finally, we also distinguish the case of pixels belonging to the offshore bloom that are not reached by iron plumes in the experiment (corresponding to false negatives in the correlation matrix).

The bathymetry is obtained from the ETOPO Global Relief model at a 30 arcsec resolution (NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, 2022).

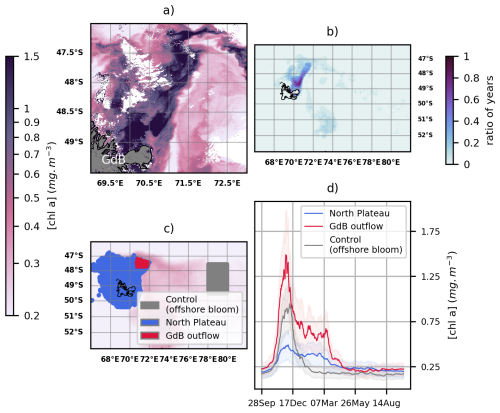

3.1 Seasonal and interannual persistence of a chlorophyll-enriched plume connected to the Golfe des Baleiniers

We observe a chlorophyll enriched plume connected to the Golfe des Baleiniers from high resolution surface chlorophyll maps, computed between January and February 2024 over the northern Kerguelen coast (Fig. 3a). The plume extends northeastward from the gulf and follows the western flank of the Polar Front. A similar spatial pattern is observed as we compute 20-year January-February Chl a climatologies over the Kerguelen region and quantify the proportion of years in which the average January-February chlorophyll at a given site is above the threshold of 0.75 mg m−3 (Fig. 3b). This threshold corresponds to the 99th percentile of the 20-year January-February Chl a averages over Kerguelen; in other words, it represents a very high concentration in these regional and seasonal contexts. However, we find that the majority (> 60 %) of the years have a high chlorophyll concentration plume extending from the Golfe des Baleiniers. Thus, the observed chlorophyll-enriched plume appears to be persistent on an interannual basis. Furthermore, this area connected to the Golfe des Baleiniers is the only area of the Kerguelen region that consistently shows blooms during the months of January-February, demonstrating its uniqueness compared to the rest of the Kerguelen region. We use the interannually persistent phytoplankton plume extending from the Golfe des Baleiniers to delineate the area where the plume leaves the shallow Plateau to join the open ocean. This area is hereafter referred to as the “Golfe des Baleiniers outflow” (GdB outflow) and is enclosed in the Northern Plateau (bathymetry less than 500 m; area shown in Fig. 3c). The GdB outflow area is deliberately located further away from the coast, as conventional altimetry products (used in Sect. 3 of the results) do not enable an adequate representation of the circulation in the first hundred meters from the coast. Therefore, the eastern, western and northern boundaries of the GdB outflow area correspond to the contour of the 0.5 mg m−3 chlorophyll concentration of the coastal bloom, averaged over the months of January and February between 2004 and 2023 (corresponding to the 95th percentile of chlorophyll concentrations over this region and period). Its southern boundary corresponds to a distance from the coast where the DUACS altimetry is considered valid (Appendix C). Using 20-year Chl a climatologies, we compute the phenology of the bloom over the GdB outflow area and compare it to the phenologies of the entire coastal bloom, as well as to a fraction of the offshore bloom (considered as a control, grey shaded area in Fig. 3c, d). The results are shown in Fig. 3d. For the offshore bloom (used as control, grey shaded area), continental iron sources are distant: iron is rapidly depleted and the bloom declines in mid-December. Conversely, both the coastal bloom (blue shaded area) and the GdB outflow bloom (red shaded area) reach a stationary phase after a peak in December and only end in early autumn when light becomes limiting again. This phenology is consistent with a persistent local supply of iron that prevents iron limitation from terminating bloom development. Moreover, the seasonal bloom appears to be stronger, in terms of magnitude, over the GdB outflow area than over the entire coastal area (this observation was confirmed by a Brunner-Munzel test: p-value< 0.001). Our hypothesis is that most of the Northern Plateau benefits from a single iron source (the resuspension of sediments), whereas the Gdb outflow benefits from an additional iron source (the glaciers), which would explain the difference of magnitude between the two areas.

Figure 3(a) High resolution surface Chl a map on 12 February 2024 (data from Sentinel 3A ocean colour product). (b) Ratio of years, between 2004 and 2023, for which January-February averaged chlorophyll concentrations exceed the threshold of 0.75 mg m−3 (data from GlobColour ocean colour product). (d) 20-year phenology of three blooms shown in panel (c): the coastal bloom (blue shaded area corresponding to the 500 m bathymetry threshold), the GdB outflow bloom (red shaded area), and a part of the offshore bloom (used as control, grey shaded area). In panel (d), uncertainties are shown as lighter shading and represent the interannual variability.

Our observations are consistent with the hypothesis of a sustained iron supply to the Golfe des Baleiniers, causing a coastal bloom that persists on a seasonal and interannual basis and extends from the gulf. Next, we investigate the circulation mechanisms at the origin of the phytoplankton plume.

3.2 Horizontal advection at the origin of the chlorophyll plume connected to the Golfe des Baleiniers

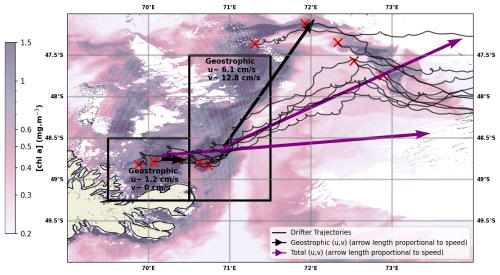

Several circulation-related mechanisms could account for the iron supply to the phytoplankton plume connected to the Golfe des Baleiniers. According to a glaciogenic iron input hypothesis, iron is supplied by horizontal surface advection. To test the hypothesis of a horizontal advection pathway connected to the Golfe des Baleiniers, two arrays of surface drifters were deployed perpendicular to the chlorophyll plume. We are interested here in the trajectories and velocities of the first array of drifters deployed in the shallow bathymetry area of the Golfe des Baleiniers (deployment positions indicated in Fig. 4).

Figure 4Purple arrows: total velocities obtained from the trajectories of the CARTHE drifters (shown as black curves). Black arrows: geostrophic velocities obtained by subtracting from the total velocities the Ekman velocities (obtained from the GlobCurrent product). Red crosses indicate drifter deployment positions. A surface Chl a map on 12 February 2024, the day of the deployment of the second array of drifters (Sentinel3 OLCI data), is shown in the background. The velocities are averaged over two areas shown as black boxes. A fine-scale geostrophic circulation pathway is shown to connect the Golfe des Baleiniers to the open ocean; furthermore, the geostrophic velocities are aligned with the direction of the chlorophyll plume, indicating that the plume most likely results from horizontal geostrophic transport.

Within a few weeks of their deployment in coastal waters, all the drifters are advected into the open ocean (Fig. 4). Their trajectories appear to have a strong eastward component, consistent with the prevailing wind direction at Kerguelen latitudes: indeed, the surface drifters are strongly influenced by the Ekman drift. Two advective branches can be distinguished. First, an eastward-flowing branch that joins the western flank of the Polar Front. Second, a northeastward-flowing branch that crosses the Polar Front under the strong influence of the westerlies. In order to compute the drifters' geostrophic velocities, we subtract the Ekman component, revealing the existence of a fine-scale geostrophic circulation pathway connecting the Golfe des Baleiniers to the open ocean, and showing a remarkable correspondence with the direction of the chlorophyll plume. In the Golfe des Baleiniers, the geostrophic currents are oriented towards the east (zonal geostrophic velocity > 0, meridional geostrophic velocity close to zero). Further away from the gulf, along the trajectories of the drifters, the geostrophic currents are oriented northeastward (geostrophic u,v > 0). This observation is coherent with the hypothesis that the observed chlorophyll plume is due to horizontal advection processes. Moreover, the duration of the trajectory from the Golfe des Baleiniers to the open ocean (of the order of the week), is consistent with the hypothesis of the horizontal transport of a tracer from the coast (as was shown using radium isotopes by Van Beek et al., 2008 and Sanial et al., 2015), rather than a passive advection of phytoplankton cells.

Our results support the hypothesis that a horizontal surface advection pathway allows glaciogenic iron to leave the Golfe des Baleiniers. During the bloom months, iron is locally consumed by phytoplankton, hence the observed chlorophyll plume. However, in winter or early spring, in the absence of biological consumption, glaciogenic iron is transported to the open ocean, raising the question of its influence on the offshore bloom onset. In order to assess this influence, we reconstruct the pathways of glaciogenic iron supply to offshore ecosystems using a Lagrangian model.

3.3 Glaciogenic iron pathway to the offshore bloom

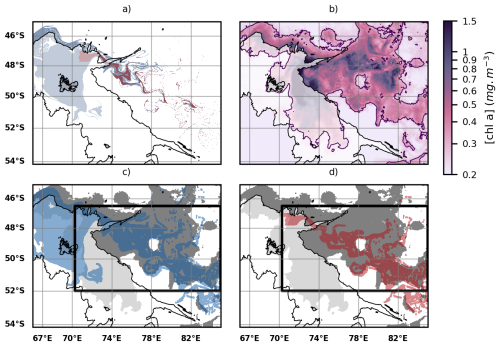

We define two areas considered as respectively glaciogenic and Plateau iron sources. The source of glaciogenic iron is included in the Northern Kerguelen Plateau, representing 5 % of the Northern Plateau area (4800 out of 106 100 km2). The glaciogenic iron source is defined as the GdB outflow area, considering the high surface chlorophyll concentration filament as a proxy for glaciogenic iron. Indeed, the presence of iron is a prerequisite for a phytoplankton bloom to develop over the GdB outflow area. While it is likely that there are regions supplied with iron from glacial sources where blooms did not develop due to light or silicon limitations, or grazing, the reciprocal (i.e. a bloom in the absence of iron supply) is not possible. Therefore, the GdB outflow area can be seen as the lower bound of the area impacted by glacial iron contribution. The Plateau iron source is defined as in Ardyna et al. (2017), corresponding to the iron originating from the entire Northern Kerguelen Plateau, using a bathymetry threshold of 500 m. Using a Lagrangian model with altimetry-derived geostrophic velocity fields from DUACS products as input, we reconstruct the glaciogenic and Plateau iron supply pathways from their respective source areas to the open ocean. The iron supply from both sources is modeled in early spring for ten consecutive years. Each year, iron transport is modeled for 60 d prior to the onset of the offshore bloom (see Material and Methods), allowing a representation of the early spring iron supply pathway.

Figure 5(a) Iron transport pathways from the GdB outflow (glaciogenic source, red plume) and the Northern Plateau (blue plume) using multi-sattelite DUACS altimetry product. The GdB outflow area is encapsulated within the Northern Plateau, so the glaciogenic iron transport pathways are included in the Plateau iron transport pathways. Iron transport is modeled for a 60 d period prior to the onset of the 2023 offshore bloom. (b) Map of surface chlorophyll concentrations over the offshore bloom area, averaged over a 10 d period centered on day 8 November 2023, identified as the onset of the 2023 offshore bloom. The offshore bloom area is considered to extend beyond the continental margin and slope, and in practice is defined by using the bathymetric threshold of 2000 m (the 2000 m bathymetric contour is shown as a black line, and the shallower regions appear as slightly shaded in white in the figures). (c) Comparison of the spatial extent of the Plateau iron plumes (blue plume) with the extent of the offshore bloom (grey patch). A statistical threshold (here, the 60th percentile) is used to delineate the offshore bloom. (d) Same as panel (c), but with the glaciogenic iron plumes (red plume). On panels (c) and (d), black boxes represent the areas where the statistics shown on Figs. 6 and 7 are computed.

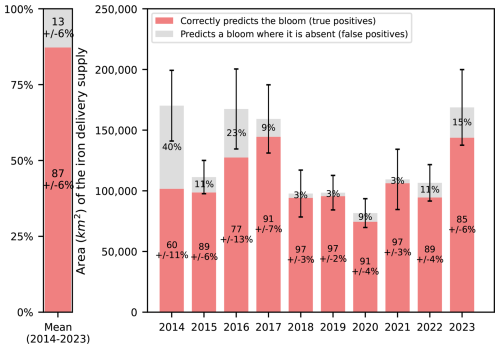

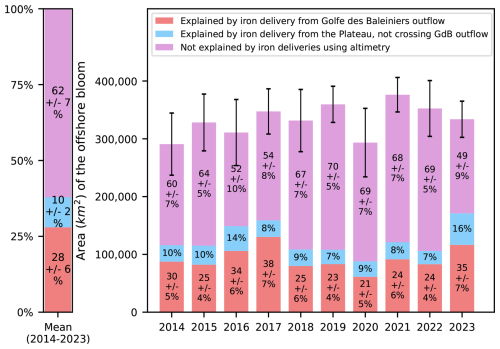

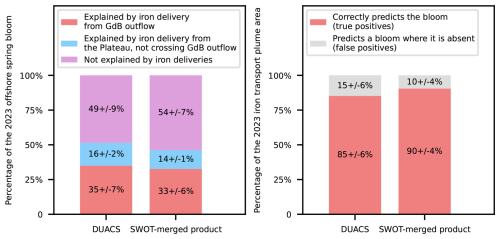

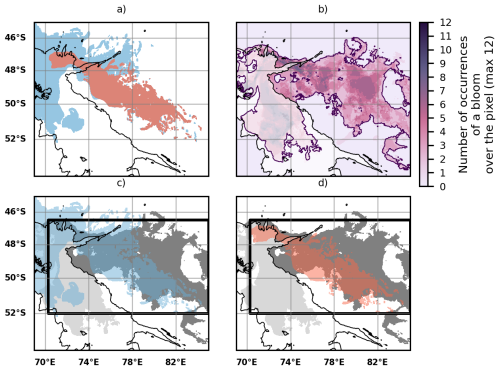

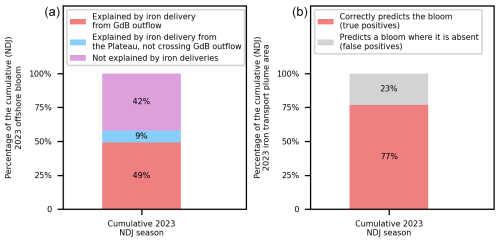

First and foremost, we observe that the advective iron plumes reconstructed by Lagrangian analysis match the horizontal extent of the offshore bloom and reproduce some mesoscale structures of plankton patchiness (Fig. 5). We further evaluate the adequacy of the reconstructed iron advective plumes in matching the fine-scale offshore bloom patchiness, calculating the ratio, with respect to the total iron plume areas, of zones supplied with iron and corresponding to bloom patches (see Material and Methods). The proportion of correct bloom localisation predictions (or true positives) represents (87 ± 6) % of the total iron plume areas, being 4 to 13 times higher than the proportion of false positives (Fig. 6). On an interannual basis, we evaluate the area of the early offshore bloom that is reached by glaciogenic and Plateau iron transport plumes (Fig. 7). We find that (28 ± 6) % of the early offshore bloom area is reached by the glaciogenic iron advective plumes, while about 40 % is reached by the Plateau iron plumes, with 10 % of the bloom being influenced by iron originating from the Plateau and not crossing the GdB outflow (Fig. 7). In fact, although the GdB outflow, considered as the glaciogenic source area, represents a small fraction of the Northern Plateau, there is a large overlap between the glaciogenic and Plateau iron plumes (representing about 70 % of the Plateau plume area). Furthermore, iron deliveries and surface chlorophyll concentrations are seasonally averaged (from 31 October to 31 January). The seasonal offshore bloom covers the whole area where the statistics are calculated, and on seasonal average, glaciogenic iron plumes reach about 45 % of the offshore bloom, while 55 % is reached by the Plateau iron supply pathways (Appendix E). In both cases, a significant fraction of the offshore bloom is not reached by any of the iron advective plumes.

Figure 6Quantification of the adequacy of the reconstructed iron supply pathways in explaining the fine-scale spatial distribution of the offshore bloom. The red bars indicate correct predictions of bloom location, that is, water parcels supplied with iron and locally corresponding to bloom patches. Conversely, the grey bars indicate incorrect predictions of bloom location, i.e. water parcels supplied with iron and not corresponding to bloom patches. Both metrics are expressed as a ratio of the total iron plume areas, averaging the statistics of the glaciogenic and Plateau iron plumes. Statistics are computed for each year between 2014 and 2023 (right panel), and the multi-year average is shown (left panel). Standard deviations, computed over an ensemble of 27 sensitivity tests (see Materials and Methods), allow to quantify the uncertainty of the metrics. Standard deviations of incorrect predictions of bloom location (grey bars) are equal to those of correct predictions (red bars), and not shown to improve figure readability. Error bars above histograms indicate a measure of the uncertainty of the area of the iron delivery plume, based on the sensitivity tests.

Figure 7Quantification of the contribution of glaciogenic and Plateau iron supply to the spatial extent of the Kerguelen offshore bloom. The red bars indicate the proportion of the bloom's spatial extent covered by iron pathways originating from the glaciogenic source (GdB outflow). The total contribution of the North Kerguelen Plateau (including coastal processes) can be visualized as the sum of the red and blue bars (the latter indicating the influence of iron originating from the Plateau and not crossing the GdB outflow). The area of the bloom covered by neither of the iron supplies is shown in purple. Statistics are computed for each year between 2014 and 2023 (right panel) and the multi-year average is shown (left panel). Standard deviations, computed over an ensemble of 27 sensitivity tests, allow quantifying the uncertainty of the metrics (see Materials and Methods and Appendix D). Standard deviations for the blue bars are not shown for readability. Error bars above histograms correspond to a measure of the uncertainty of the spatial extension of the bloom.

The Lagrangian advective plumes of glaciogenic and Plateau iron inputs were also reconstructed using the SWOT-merged MIOST altimetry product (Fig. B1) to compare the improvements of SWOT over traditional altimetry in representing fine scale structures. The potential improvement of resolution brought by SWOT did not change qualitatively the conclusions we reached with the DUACS conventional product. Both Lagrangian plumes, reconstructed using either the SWOT-merged MIOST product (Fig. B1) or DUACS (Fig. 5), were able to reach similar proportions of the phytoplankton bloom through an advective iron supply from continental (coastal and continental margin) sources. We conclude that DUACS conventional products are largely reliable for this case, even without the inclusion of SWOT wide swath observations, possibly because the dominant mesoscale circulation in the area has scales large enough to be well resolved by DUACS. Other regions with smaller and weaker mesoscale eddies, like for instance the Mediterranean sea (Escudier et al., 2016), may be a better case study for exploring SWOT improvements.

Phytoplankton blooms in the Southern Ocean provide a wide range of ecosystem services, from supporting fisheries and species of patrimonial value to contributing to climate regulation (Bindoff et al., 2019). Identifying the sources of iron that fertilize these blooms, as well as how these sources may evolve in the context of climate change, is crucial for predicting the future dynamics of Southern Ocean primary producers and the ecosystems that depend on them (Hutchins and Boyd, 2016; Hutchins and Tagliabue, 2024). In this context, assessing the contribution of the cryosphere-mediated iron supply to marine ecosystems is essential. However, this process has long been overlooked, particularly at subantarctic latitudes. Here, we present a case study highlighting the significance of glaciogenic iron supply and provide the first assessment of its pathways to the coastal and offshore phytoplankton blooms in the Kerguelen region.

Our study focuses on the Golfe des Baleiniers, where two glaciers are likely to discharge lithogenic iron (e.g. Raiswell et al., 2006, 2008; Gerringa et al., 2012; Bhatia et al., 2013; Van Der Merwe et al., 2019; Kanna et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2019, 2020). We observe a coastal phytoplankton bloom persistent on an interannual basis, extending from the Golfe des Baleiniers. The bloom exhibits a distinct seasonality that persists into early autumn, in contrast to the phenology of other blooms in the Kerguelen region (Fig. 3). We show that the phytoplankton-rich plume is caused by horizontal advection processes connecting the Golfe des Baleiniers to the open ocean. More specifically, by sampling the coastal circulation with drifters, we demonstrate the existence of a fine-scale circulation exiting the gulf, that closely matches with the direction of the plume (Fig. 4). We further assess the influence of glaciogenic iron transport pathways on the distribution of the early offshore phytoplankton bloom. We find that about one third of the early offshore bloom is reached by glacial iron supply pathways, supporting the rationale that glaciogenic iron supply routes significantly influence the development of blooms (Fig. 7). This article demonstrates that the region where glaciogenic iron is released into the ocean is connected to the offshore area in which the bloom occurs. The quantification of the biogeochemical contribution of the glacier to the phytoplankton bloom represents an interesting and complementary avenue of investigation that will be addressed by other studies within the MARGOCEAN project.

A significant part of the offshore bloom (about 60 %) is not reached by the advective iron plumes (Figs. 5 and 7). This is not surprising because several other iron sources and associated transport pathways not considered in this study could also influence the development of the offshore bloom. Hydrothermal sources close to oceanic ridges (Yesson et al., 2011) have been shown to influence bloom development in the Southern Ocean (Ardyna et al., 2019; Sergi et al., 2020), but their importance in the Kerguelen region remains poorly understood. We also hypothesize an influence of iron originating from the Crozet Archipelago, located northwest of Kerguelen, i.e. upstream of the ACC (Planquette et al., 2007, 2009). This contribution may play a role especially in the northern part of the Kerguelen offshore bloom which, according to our Lagrangian model, remains poorly reached by advective iron plumes from the Northern Kerguelen Plateau. The Central Kerguelen Plateau (defined here as south of the Kerguelen Islands, separated from the Northern Plateau by the Polar Front) could also be a possible source of iron for the offshore bloom, although its influence is expected to be small due to weaker current fields (Fig. 1) and hence to the possible presence of recirculation features. A counterclockwise circulation, as hypothesized by Van Beek et al. (2008), would be dominant over the Central Kerguelen Plateau, and entail northwestward currents, reducing the potential transport of iron from the Central Plateau to the region of the offshore bloom. Finally, some of the other Kerguelen glaciers that discharge over the south and west coasts of Kerguelen may represent another source of iron to the offshore bloom unaccounted for in our study. The local circulation constrains the transport of the material originating from these glaciers in a narrow band along the coast, before it reaches the northern part of the Plateau (Park et al., 2008). The iron supply from the glaciers located on the west and south coasts of Kerguelen has yet to be documented. A similar approach as done here for the GdB outflow, with an increase in the duration of the advection, could be considered to study the probable iron pathways associated with the glaciers. However, following this rationale, part of what is labeled here as the Plateau iron source also contains iron of glacial origin. Conversely, the glaciogenic iron plume originating from the GdB outflow is likely to be supplied by a combination of coastal processes (including the glaciers) and sediments from the continental margin. Therefore, our results should be considered as an order of magnitude of the influence of glaciogenic iron on the offshore bloom.

Our results, which focus on horizontal mixing of iron sources, do not rule out the influence of vertical processes. In fact, horizontal and vertical processes often act in concert when supplying nutrients to the euphotic layer (Lévy et al., 2018; Mahadevan, 2016; McGillicuddy, 2016). Thus, several studies (e.g. Calil et al., 2011; Taylor and Ferrari, 2011; Haëck et al., 2023) have evidenced an increased phytoplankton abundance along fronts, which are regions prone to vertical velocities. Fine scale eddies and fronts may enhance primary production by enabling an upward flux of nutrients to the euphotic zone, when the induced vertical velocity field reaches the nutricline. In principle, this could be the case for the surface chlorophyll filament depicted in Fig. 4. Although high resolution modeling and ad hoc field experiments could help elucidate this point, SAR images from SWOT, which may contain signs of surface divergence associated with vertical cells (Wang et al., 2019), do not show any hint of vertical processes (Appendix F), further confirming the dominant role of horizontal transport. A second vertical process that we did not address directly but that could contribute to the enhancement of surface chlorophyll in synergy with lateral dispersion is the entrainment effect associated with the seasonal shallowing of the mixed layer (Bowie et al., 2015, supplementary material).

In our study, we aim at unveiling the existence of a transport pathway connecting the open ocean phytoplankton blooms to a potential iron source of glaciogenic origin. aking a biogeochemical iron budget is beyond the scope of the study; instead, this study provides a complementary approach to the biogeochemical iron budget addressed by the ongoing analysis of the MARGOCEAN in situ water samplings (in a similar way to Van Der Merwe et al., 2019 on Heard Island) aiming to quantify the flux of glaciogenic iron to the Golfe des Baleiniers. In our study, areas defined as iron sources are not directly correlated with initial iron concentrations. In fact, despite numerous measurements in the vicinity of Kerguelen, there is little information on the spatial variability of iron inputs on the northern Kerguelen Plateau at such small scales, which prevents us from delineating iron sources based on in situ measurements, or balancing the iron advective plumes with the amount of iron at the source. As such, the area considered as a glaciogenic iron source is contained within the Northern Plateau and most likely benefits from two iron sources: a resuspension-derived supply and a glaciogenic supply. However, as our study is independent of initial concentrations, the presence of one or more iron sourcing mechanisms that overlap the GdB outflow area does not affect our results.

A number of complex biogeochemical reactions may influence the concentration of dissolved iron while it is being transported from its sources to the open ocean, among which are complexation to organic ligands, scavenging, or in situ regeneration (Boyd and Ellwood, 2010; Gledhill, 2012). In this study, we consider all iron removal processes simultaneously. Indeed, our simple formulation of iron concentration evolution over time (see Material and Methods) does not enable us to single out the impact of each iron removal process, nor is this within the scope of our study. Moreover, we do not account for iron remineralization. We use the estimations of biotic and abiotic iron removal rates from the KEOPS2 cruise (d'Ovidio et al., 2015), since this cruise was designed to correlate removal rates with transport routes, and was conducted in the same season as our study. However, by performing sensitivity tests of iron supply thresholds, we introduce an element of uncertainty into the iron removal rates. Indeed, changing the iron supply threshold at a fixed integration time results in a change in iron removal rates. For instance, if the remaining fraction of the initial iron content is smaller after the same advection time, stronger removal processes are involved.

This study provides insight into the projected effects of climate change on the iron supply to the Kerguelen bloom. The Kerguelen Cook Ice Cap (CIC) has experienced a negative surface mass balance, thinning, and decrease of its area in recent decades. The area of the Cook Ice Cap decreased by 20 % between 1963 and 2001, with the ice retreat accelerating since the 1990s (Berthier et al., 2009). Over a more recent period, between 2000 and 2010, the mass balance of the ice cap showed a tremendous decrease of (−1.59 ± 0.19) m w.e. yr−1, accompanied by a significant thinning of the ice cap of (0.4 ± 0.1) m yr−1 (Favier et al., 2016). The loss has been shown to be even more pronounced for some of the outlet glaciers of the CIC (Favier et al., 2016). While a similar situation has been reported for other subantarctic glaciers (e.g. Chinn, 1996 or Kirkbride and Warren, 1999 in New Zealand; Gordon et al., 2008 in South Georgia; Thost and Truffer, 2008 on Heard Island), the Kerguelen Cook Ice Cap is considered to be experiencing one of the most accelerated melting rates in recent records. Verfaillie et al. (2021) found a possible disappearance of the Cook Ice Cap by the end of the century under the RCP8.5 global emissions scenario of CMIP5 model projections. A recent study conducted in the Ampère Glacier and Table Fjord region, in the southern part of the Cook Ice Cap, combined instrumental data, glacial deposits, and sedimentary proxies to investigate the variability of CIC extent and the sediment load produced by glacial erosion (Chassiot et al., 2024). It appears that the increase in glacial sediments reflects an increase in the size of the CIC. Consequently, over the next century, it is likely that glaciogenic inputs into the marine environment will decrease until it dries up after the disappearance of the CIC. Conversely, hydrothermal (if existing) and non glaciogenic Plateau iron sources are very unlikely to evolve in the framework of climate change, as described in the general case by Hutchins and Boyd (2016). Climate change would hence entail a modification of the current iron external supply to Kerguelen ecosystems.

However, the evolution of iron sources is one way in which climate change could affect the iron supply to the Kerguelen blooms. In recent decades, Ryan-Keogh et al. (2023) measured an increase in iron stress in Southern Ocean phytoplankton, which they attributed to changes in stratification and nutrient supply on the one hand, and to complex changes in biogeochemical feedbacks on the other. The biogeochemical iron cycle consists of several complex processes, each of which is more or less likely to evolve in the coming decades. Their cumulative effect on the iron cycle is all the more unknown (Hutchins and Boyd, 2016). For example, there is little consensus on the response of biological iron demand to ocean warming. Indeed, Southern Ocean phytoplankton are known to exhibit significant stoichiometric plasticity, developing photoacclimation strategies to economise on iron use in low light and iron environments (Strzepek et al., 2012). In addition, the impact of climate change on the fine-scale circulation, and hence on iron transport pathways from Kerguelen continental iron sources to offshore blooms, is difficult to assess. On a larger scale in the Southern Ocean, westerly winds, which influence the transport and meridional position of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (Beadling et al., 2020), have been shown to intensify and shift poleward (Chapman et al., 2020). In addition, fine scale processes have been shown from satellite data to intensify since the 1990s due to increased wind stress (Martínez‐Moreno et al., 2019; Martínez-Moreno et al., 2021). These trends can be expected to persist with climate change. A recent study showed that, depending on global emissions scenarios, the northernmost extent of Winter Waters could shift strongly to the south of the Kerguelen Islands, implying major modifications to the circulation in the region (Azarian et al., 2024).

This study takes a multidisciplinary approach to reveal connectivity patterns between Kerguelen glaciers, which are shrinking due to climate change, and the offshore bloom region, which supports unique ecosystems. Thus, this article presents a case study examining a mechanism that contributes to biological productivity and is projected to be impacted by climate change (through the decrease in the spatial extent of glaciers), at a regional scale, on a subantarctic ecosystem.

Figure A1Absolute dynamic topography (ADT) and streamlines derived from altimetry (DUACS multisatellite product) in the Kerguelen region, 2004–2023 seasonal climatologies as averages of (a) November to January months; (b) February to April months; (c) May to July months; (d) August to October months. The arrow linewidth is proportional to the speed of geostrophic currents. Bathymetric contours (500 and 2000 m depth) are shown. A climatology of some of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) fronts are shown in red: the Subantarctic Front (SAF), the Polar Front (PF), and the Southern ACC front (SACCF) (constructed from mean dynamic topography, source: Park and Durand, 2019; Park et al., 2019).

We used the recently made available SWOT-merged MIOST product, a multi-satellite product combining SWOT and DUACS data (Ubelmann et al., 2021; Ballarotta et al., 2023) to compare the improvements of SWOT over DUACS in representing fine scale biogeochemical patterns of the offshore phytoplankton bloom. Due to data availability, the iron deliveries reconstructed with the SWOT-merged product covered only one year, i.e. the 2023 spring bloom (Fig. B1). We found that, using either the SWOT-merged MIOST product (Fig. B1) or DUACS (Fig. 5), about half of the 2023 spring bloom was reached by the Plateau iron inputs, while the other half remained unexplained by these iron supplies (Fig. B2, right panel). The only metrics in which SWOT higher precision seemed to play an important role was the reduction of false positives in the extension of the predicted plume. For this case, the proportion of iron plume areas that did not overlap with bloom locations decreased by 30 % when estimated with SWOT-MIOST (Fig. B2, left panel, grey bar). Therefore, the addition of high-resolution altimetry measurements made along SWOT swaths did not change the conclusions we reached with conventional altimetry.

Figure B1(a) Iron transport pathways from the GdB outflow (glaciogenic source, red plume) and the Plateau (blue plume) using the SWOT-merged L4 MIOST altimetry product. Iron transport is modelled as in Fig. 5, but with MIOST as the input of the Lagrangian model. (b) Map of surface chlorophyll concentrations over the offshore bloom area averaged over a 10 d period centered on day 8 November 2023 as in Fig. 5. (c) Comparison of the spatial extent of the sedimentary iron plumes (blue plume) with the extent of the offshore bloom (grey patch). (d) Same as panel (c), but with the glaciogenic iron plumes (red plume).

Figure B2Comparison of the SWOT-merged MIOST product vs. DUACS in explaining the fine-scale spatial distribution of the offshore bloom (left panel) and the spatial extent of the Kerguelen offshore bloom (right panel). The statistics shown on the right (resp. left) panels are identical to those of Fig. 6 (resp. Fig. 7).

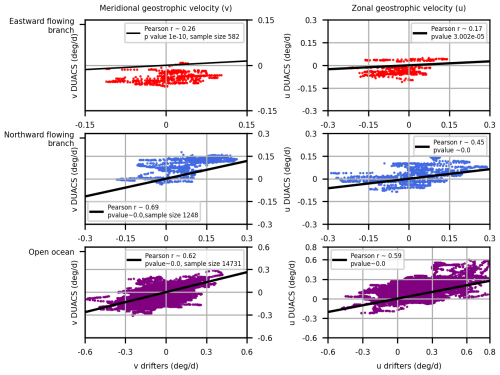

Figure C1Scatterplots comparing DUACS and CARTHE drifters zonal and meridional geostrophic velocities in three areas: the eastward (top) and northward (middle) flowing branches of the phytoplankton filament as well as the open ocean (bottom). The eastward and northward-flowing branches are indicated on Fig. 4 as black boxes, and respectively correspond to the areas [69.5, 70.5]° E, [−49.25, −48.5]° N and [70.5, 71.5]° E, [−48.5, −47.5]° N.

The DUACS geostrophic velocity fields were compared with the in-situ measurements of geostrophic velocities provided by the CARTHE drifters. We compared the velocities over three areas. The first two areas correspond respectively to the eastward and northward-flowing branches of the phytoplankton filament, shown on Fig. 4 and respectively correspond to the areas [69.5, 70.5]° E, [−49.25, −48.5]° N and [70.5, 71.5]° E, [−48.5, −47.5]° N. The third case corresponds to the open ocean. DUACS velocities poorly correlated with drifter velocities close to the coast (eastward-flowing branch). In fact, DUACS indicated negative meridional and zonal geostrophic velocities in the Golfe des Baleiniers, which is contradictory with in-situ data (positive zonal geostrophic velocity and near-zero meridional geostrophic velocity). This is not surprising as DUACS data are acknowledged to be unreliable in coastal waters. However, further away from the coast (northward flowing branch and open ocean), DUACS velocities correlated much better with drifter velocities. This observation was taken into consideration when determining the “GdB outflow” area, considered as a glaciogenic iron source in the Lagrangian advection experiment. More precisely, the southernmost extent of the GdB outflow area corresponds to the latitude 47.5° S, which is the northernmost limit of the area labeled as “northward flowing branch”.

Here we illustrate the sensitivity tests used in Results Sect. 3. We carried out tests on three parameters that influenced the spatial extent of the offshore bloom and of the iron delivery plumes as shown on Fig. D1. The impact of parameter choice on the uncertainty of the statistics is displayed as error bars in Figs. 6, 7 and B2.

Figure D1Illustration of the influence of parameter choice (resp. chlorophyll thresholds, extrapolation width and iron content thresholds) on the spatial extent of the offshore bloom (a–c) and of the iron plume (d–i). We relied on statistical thresholds of chlorophyll concentrations to define the spatial extent of the offshore bloom (a–c). We therefore tested the influence of the choice of threshold on our results by using three different thresholds, corresponding to the 70th (a) and 60th (b) percentiles and to the median (c). We extrapolated the iron plumes to the nearest n pixels (pixel size: 0.01° longitude and latitude) (d–f). We therefore tested three values for n (5, 8 and 10) corresponding to an extrapolation to 0.10° × 0.10° (d), 0.16° × 0.16° (e) and 0.20° × 0.20° (f) squares centered on the initial iron trajectories. Three durations of iron advection were tested (g–i). The durations correspond to iron reductions of 0.1 (g), 0.3 (h) and 0.5 % (i) with respect to concentrations at the source.

In this section, we present an alternative methodology to that presented in Sect. 3.3 of the Results. Rather than focusing on the onset of the offshore bloom (approximately mid-October to mid-November depending on the year), we compare iron delivery pathways and the spatial extent of the offshore bloom throughout the entire season. Between the beginning of November and the end of January, we conduct one iron delivery experiment per week. For example, for the summer bloom in 2023, we conducted 12 advection experiments between 8 November (the onset of the offshore bloom) and 28 January. On each of these dates, we observe the spatial extent of the offshore bloom to the east of Kerguelen, using the methodology detailed in Sect. 2.3.2 of the Materials and Methods section. We consider the cumulative impact of iron deliveries on the spatial extent of the bloom over a season. We consider all pixels that were reached by iron delivery plumes at least once during the season (i.e. in at least one of the advection experiments performed) to be part of the cumulative seasonal iron plumes (Fig. E1a). Similarly, we consider a pixel to be part of the cumulative seasonal offshore bloom if it was part of the offshore bloom at any time during the experiments (Fig. E1b). Figure E1 illustrates the 2023 summer bloom example. Figure E2 compares the spatial extent of the cumulative 2023 offshore bloom with the areas of the iron plumes. We observe that despite adopting a cumulative approach, a significant proportion of the offshore bloom is not reached by the iron plumes. We chose not to present this methodology in the main part of the article due to its sensitivity to the passive advection of phytoplankton cells as well as its computing cost.

Figure E1(a) Cumulative iron transport pathways from the GdB outflow (glaciogenic source, red plume) and the Northern Plateau (blue plume) using the DUACS altimetry product. A backward iron advection experiment was performed each week between 8 November 2023 and 28 January 2024 (60 d advection duration as used in the Sect. 3.3 of the Results). We consider that a water parcel which was part of an iron plume during at least one of the experiments is part of the cumulative iron plume (respectively either glaciogenic or Plateau). (b) Map showing the number of occurrences of a bloom over a pixel located in the offshore area (the occurrences range from 0 to 12). The purple contour indicates a minimal occurrence of 1. Each water parcel within this contour is considered to be part of the cumulative 2023 summer offshore bloom: it has hosted a bloom at least once in our experiments. (c) Comparison of the spatial extent of the cumulative Plateau iron plume (blue plume) with the cumulative offshore bloom (grey patch). (d) Same as panel (c) but with the glaciogenic iron plumes (red plume). On panels (c) and (d) the black boxes represent the areas where the statistics shown on Fig. E2 are computed.

Figure E2(a) Quantification of the contribution of glaciogenic and Plateau cumulative iron supplies to the spatial extent of the 2023 summer offshore bloom. (b) Quantification of the adequacy of the reconstructed cumulative iron supply pathways in explaining the spatial distribution of the cumulative 2023 offshore bloom. The statistics shown on the left (resp. right) panels are similar to those of Fig. 7 (resp. Fig. 6), but considering the cumulative spatial extent of iron plumes and the offshore bloom throughout the season instead of just the onset of the offshore bloom.

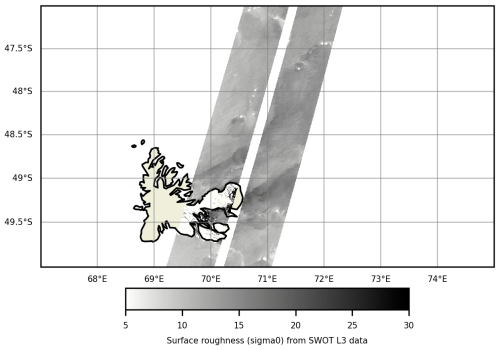

Surface divergence mechanisms may indicate transport processes associated with upward vertical circulation, and can be observed using the SWOT satellite's SAR instrument by analyzing surface roughness (Wang et al., 2019). Here we provide a map of surface roughness over the Golfe des Baleiniers, at the moment of the MARGOCEAN cruise. The analysis of surface roughness over the Golfe des Baleiniers does not show any sign of surface divergence associated with vertical processes. This observation points towards a dominant role of horizontal advective processes in the Golfe des Baleiniers.

This study was conducted as part of the MARGOCEAN project and cruise (https://doi.org/10.17600/18002958, Blain and Obernosterer, 2024). The GPS positions of CARTHE drifters used in this study were published in SEANOE (https://doi.org/10.17882/103561, Berta et al., 2024). The Lagrangian software used is available through GitHub at https://github.com/OceanCruises/SPASSO/ (Rousselet et al., 2025). This work used the color-vision deficiency friendly colormaps built by Crameri (2018, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1243862).

AN, FdO, LB, and SB conceived the work. AN performed the numerical analysis with the help of LR. SB led the oceanographic campaign. CA conducted the in situ Lagrangian experiment with the on-land assistance of MB. AN wrote the paper with the help of all other coauthors.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This work is a contribution to the ANR-22-CE01-0004 project Matter of glacial origin and its fate in the ocean: a case study at Kerguelen – MARGO. This work was performed with the support of the CNES/Tosca projects SO-BIO-SAT and BIOSWOT-ADAC and of the Institut des Sciences du Calcul et des Données (ISCD) of Sorbonne University (IDEX SUPER 11-IDEX-0004) through the support of the sponsored project-team FORMAL (From ObseRving to Modelling oceAn Life). Collection of drifter data supported by the MARGO (Material of glacial origin and its fate in the ocean) project and partners, and by CNR-ISMAR (Lerici, Italy) dedicated fundings.

This paper was edited by Emilio Marañón and reviewed by Thomas M. Holmes, Ryan Cloete, and Yoav Lehahn.

Ardyna, M., Claustre, H., Sallée, J., D'Ovidio, F., Gentili, B., Van Dijken, G., D'Ortenzio, F., and Arrigo, K. R.: Delineating environmental control of phytoplankton biomass and phenology in the Southern Ocean, Geophysical Research Letters, 44, 5016–5024, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL072428, 2017. a, b, c, d

Ardyna, M., Lacour, L., Sergi, S., d'Ovidio, F., Sallée, J.-B., Rembauville, M., Blain, S., Tagliabue, A., Schlitzer, R., Jeandel, C., Arrigo, K. R., and Claustre, H.: Hydrothermal vents trigger massive phytoplankton blooms in the Southern Ocean, Nature Communications, 10, 2451, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09973-6, 2019. a, b

Arrigo, K. R., Van Dijken, G. L., and Strong, A. L.: Environmental controls of marine productivity hot spots around Antarctica, Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 120, 5545–5565, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JC010888, 2015. a, b

Arrigo, K. R., Van Dijken, G. L., Castelao, R. M., Luo, H., Rennermalm, A. K., Tedesco, M., Mote, T. L., Oliver, H., and Yager, P. L.: Melting glaciers stimulate large summer phytoplankton blooms in southwest Greenland waters, Geophysical Research Letters, 44, 6278–6285, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL073583, 2017. a, b

Azarian, C., Bopp, L., Sallée, J.-B., Swart, S., Guinet, C., and d'Ovidio, F.: Marine heatwaves and global warming impacts on winter waters in the Southern Indian Ocean, Journal of Marine Systems, 243, 103962, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmarsys.2023.103962, 2024. a

Ballarotta, M., Ubelmann, C., Veillard, P., Prandi, P., Etienne, H., Mulet, S., Faugère, Y., Dibarboure, G., Morrow, R., and Picot, N.: Improved global sea surface height and current maps from remote sensing and in situ observations, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 15, 295–315, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-295-2023, 2023. a, b

Beadling, R. L., Russell, J. L., Stouffer, R. J., Mazloff, M., Talley, L. D., Goodman, P. J., Sallée, J. B., Hewitt, H. T., Hyder, P., and Pandde, A.: Representation of Southern Ocean Properties across Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Generations: CMIP3 to CMIP6, Journal of Climate, 33, 6555–6581, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-19-0970.1, 2020. a

Berta, M., Griffa, A., Magaldi, M. G., Özgökmen, T. M., Poje, A. C., Haza, A. C., and Olascoaga, M. J.: Improved Surface Velocity and Trajectory Estimates in the Gulf of Mexico from Blended Satellite Altimetry and Drifter Data, Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 32, 1880–1901, https://doi.org/10.1175/JTECH-D-14-00226.1, 2015. a, b

Berta, M., Azarian, C., Nalivaev, A., Blain, S., and D'Ovidio, F.: CARTHE drifters deployment within the MARGOCEAN experiment in the Antarctic Ocean, SEANOE [data set], https://doi.org/10.17882/103561, 2024. a, b

Berthier, E., Le Bris, R., Mabileau, L., Testut, L., and Rémy, F.: Ice wastage on the Kerguelen Islands (49° S, 69° E) between 1963 and 2006, Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface, 114, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JF001192, 2009. a

Bhatia, M. P., Kujawinski, E. B., Das, S. B., Breier, C. F., Henderson, P. B., and Charette, M. A.: Greenland meltwater as a significant and potentially bioavailable source of iron to the ocean, Nature Geoscience, 6, 274–278, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1746, 2013. a, b

Bindoff, N. L., Cheung, W. W. L., Kairo, J. G., Arístegui, J., Guinder, V. A., Hallberg, R., Hilmi, N., Jiao, N., Karim, M. S., Levin, L., O’Donoghue, S., Purca Cuicapusa, S. R., Rinkevich, B., Suga, T., Tagliabue, A., and Williamson, P.: Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, edited by: Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D. C., Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Nicolai, M., Okem, A., Petzold, J., Rama, B., and Weyer, N. M., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 447–587, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157964.007, 2019. a

Blain, S. and Obernosterer, I.: MARGOCEAN cruise, RV Marion Dufresne, Flotte oceanographique française, https://doi.org/10.17600/18002958, 2024. a, b

Blain, S., Tréguer, P., Belviso, S., Bucciarelli, E., Denis, M., Desabre, S., Fiala, M., Martin Jézéquel, V., Le Fèvre, J., Mayzaud, P., Marty, J.-C., and Razouls, S.: A biogeochemical study of the island mass e!ect in the context of the iron hypothesis: Kerguelen Islands, Southern Ocean, Deep-Sea Research, 163–187, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0637(00)00047-9, 2000. a

Blain, S., Quéguiner, B., Armand, L., Belviso, S., Bombled, B., Bopp, L., Bowie, A., Brunet, C., Brussaard, C., Carlotti, F., Christaki, U., Corbière, A., Durand, I., Ebersbach, F., Fuda, J.-L., Garcia, N., Gerringa, L., Griffiths, B., Guigue, C., Guillerm, C., Jacquet, S., Jeandel, C., Laan, P., Lefèvre, D., Lo Monaco, C., Malits, A., Mosseri, J., Obernosterer, I., Park, Y.-H., Picheral, M., Pondaven, P., Remenyi, T., Sandroni, V., Sarthou, G., Savoye, N., Scouarnec, L., Souhaut, M., Thuiller, D., Timmermans, K., Trull, T., Uitz, J., Van Beek, P., Veldhuis, M., Vincent, D., Viollier, E., Vong, L., and Wagener, T.: Effect of natural iron fertilization on carbon sequestration in the Southern Ocean, Nature, 446, 1070–1074, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05700, 2007. a, b, c

Blain, S., Sarthou, G., and Laan, P.: Distribution of dissolved iron during the natural iron-fertilization experiment KEOPS (Kerguelen Plateau, Southern Ocean), Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 55, 594–605, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2007.12.028, 2008. a, b

Bowie, A. R., Lannuzel, D., Remenyi, T. A., Wagener, T., Lam, P. J., Boyd, P. W., Guieu, C., Townsend, A. T., and Trull, T. W.: Biogeochemical iron budgets of the Southern Ocean south of Australia: Decoupling of iron and nutrient cycles in the subantarctic zone by the summertime supply, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 23, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GB003500, 2009. a

Bowie, A. R., van der Merwe, P., Quéroué, F., Trull, T., Fourquez, M., Planchon, F., Sarthou, G., Chever, F., Townsend, A. T., Obernosterer, I., Sallée, J.-B., and Blain, S.: Iron budgets for three distinct biogeochemical sites around the Kerguelen Archipelago (Southern Ocean) during the natural fertilisation study, KEOPS-2, Biogeosciences, 12, 4421–4445, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-12-4421-2015, 2015. a, b, c, d

Boyd, P. W. and Ellwood, M. J.: The biogeochemical cycle of iron in the ocean, Nature Geoscience, 3, 675–682, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo964, 2010. a, b, c

Boyd, P. W., Watson, A. J., Law, C. S., Abraham, E. R., Trull, T., Murdoch, R., Bakker, D. C. E., Bowie, A. R., Buesseler, K. O., Chang, H., Charette, M., Croot, P., Downing, K., Frew, R., Gall, M., Hadfield, M., Hall, J., Harvey, M., Jameson, G., LaRoche, J., Liddicoat, M., Ling, R., Maldonado, M. T., McKay, R. M., Nodder, S., Pickmere, S., Pridmore, R., Rintoul, S., Safi, K., Sutton, P., Strzepek, R., Tanneberger, K., Turner, S., Waite, A., and Zeldis, J.: A mesoscale phytoplankton bloom in the polar Southern Ocean stimulated by iron fertilization, Nature, 407, 695–702, https://doi.org/10.1038/35037500, 2000. a

Boyd, P. W., Law, C. S., Hutchins, D. A., Abraham, E. R., Croot, P. L., Ellwood, M., Frew, R. D., Hadfield, M., Hall, J., Handy, S., Hare, C., Higgins, J., Hill, P., Hunter, K. A., LeBlanc, K., Maldonado, M. T., McKay, R. M., Mioni, C., Oliver, M., Pickmere, S., Pinkerton, M., Safi, K., Sander, S., Sanudo‐Wilhelmy, S. A., Smith, M., Strzepek, R., Tovar‐Sanchez, A., and Wilhelm, S. W.: FeCycle: Attempting an iron biogeochemical budget from a mesoscale SF6 tracer experiment in unperturbed low iron waters, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 19, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GB002494, 2005. a

Boyd, P. W., Jickells, T., Law, C. S., Blain, S., Boyle, E. A., Buesseler, K. O., Coale, K. H., Cullen, J. J., De Baar, H. J. W., Follows, M., Harvey, M., Lancelot, C., Levasseur, M., Owens, N. P. J., Pollard, R., Rivkin, R. B., Sarmiento, J., Schoemann, V., Smetacek, V., Takeda, S., Tsuda, A., Turner, S., and Watson, A. J.: Mesoscale Iron Enrichment Experiments 1993–2005: Synthesis and Future Directions, Science, 315, 612–617, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1131669, 2007. a

Bucciarelli, E., Blain, S., and Treguer, P.: Iron and manganese in the wake of the Kerguelen Islands Southern Ocean, Marine Chemistry, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4203(00)00070-0, 2001. a

Calil, P. H. R., Doney, S. C., Yumimoto, K., Eguchi, K., and Takemura, T.: Episodic upwelling and dust deposition as bloom triggers in low-nutrient, low-chlorophyll regions, Journal of Geophysical Research, 116, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JC006704, 2011. a

Chapman, C. C., Lea, M.-A., Meyer, A., Sallée, J.-B., and Hindell, M.: Defining Southern Ocean fronts and their influence on biological and physical processes in a changing climate, Nature Climate Change, 10, 209–219, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0705-4, 2020. a

Chassiot, L., Chapron, E., Michel, E., Jomelli, V., Favier, V., Verfaillie, D., Foucher, A., Charton, J., Paterne, M., and Van der Putten, N.: Late Holocene record of subantarctic glacier variability in Table Fjord, Cook Ice Cap, Kerguelen Islands, Quaternary Science Reviews, 344, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2024.108980, 2024. a

Chever, F., Sarthou, G., Bucciarelli, E., Blain, S., and Bowie, A. R.: An iron budget during the natural iron fertilisation experiment KEOPS (Kerguelen Islands, Southern Ocean), Biogeosciences, 7, 455–468, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-7-455-2010, 2010. a, b

Chinn, T. J.: New Zealand glacier responses to climate change of the past century, New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics, 39, 415–428, https://doi.org/10.1080/00288306.1996.9514723, 1996. a

Crameri, F.: Scientific colour-maps, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1243862, 2018. a

D'Asaro, E. A., Carlson, D. F., Chamecki, M., Harcourt, R. R., Haus, B. K., Fox-Kemper, B., Molemaker, M. J., Poje, A. C., and Yang, D.: Advances in Observing and Understanding Small-Scale Open Ocean Circulation During the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative Era, Frontiers in Marine Science, 7, 349, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00349, 2020. a

Donohue, K. A., Tracey, K. L., Watts, D. R., Chidichimo, M. P., and Chereskin, T. K.: Mean Antarctic Circumpolar Current transport measured in Drake Passage, Geophysical Research Letters, 43, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL070319, 2016. a