the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Proteomic and biogeochemical perspectives on cyanobacteria nutrient acquisition – Part 1: Zonal gradients in phosphorus and nitrogen acquisition and stress revealed by metaproteomes of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus

Claire Mahaffey

Noelle A. Held

Korinne Kunde

Clare Davis

Neil Wyatt

E. Matthew R. McIlvin

E. Malcolm S. Woodward

Lewis Wrightson

Alessandro Tagliabue

Maeve C. Lohan

Mak Saito

Ocean productivity is maintained by key nutrients, including nitrogen, phosphorus and trace metals. The magnitude and stoichiometry of nutrient fluxes to the ocean is changing. Here, we investigate how natural assemblages of marine microbes in the subtropical North Atlantic respond to variation in nutrient availability along a natural zonal gradient. We measure dissolved nutrient concentrations, biological rates, and characterize the microbial proteomes of the dominant picocyanobacteria, Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus. Moving west to east, dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP) and phosphate concentrations increased, and dissolved iron decreased. Prochlorococcus abundance increased eastwards, whereas Synechococcus abundance was highest in the west. Zonal distributions of protein biomarkers representing phosphorus (PstS, PhoA, PhoX), nitrogen (P-II, UrtA, AmtB) and trace metal metabolism (related to iron, zinc and cobalt) from metaproteomes, together with rates of alkaline phosphatase activity, indicate greater phosphorus stress in the west than the east for both picocyanobacteria. In the east, elevated levels of protein biomarkers for nitrogen, iron, zinc and cobalamin in Prochlorococcus indicate a transition to nitrogen stress and greater influence of trace metal resources. Measured responses of Prochlorococcus ecotypes and Synechococcus clades to DOP, iron and zinc additions in incubation experiments further indicate divergent regulation in uptake and acquisition of phosphorus by these picocyanobacteria across the transect, albeit with caveats on the potential for differences in regulation within a genus and between strains. Together our findings suggest a basin-scale transition from phosphorus stress in picocyanobacteria in the west to nitrogen stress in the east.

- Article

(5258 KB) - Full-text XML

- Companion paper

-

Supplement

(14708 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Marine phytoplankton have an important role in biogeochemical cycles, supporting ecosystems and regulating climate. Global net primary productivity (NPP) is underpinned by availability of key nutrient resources, such as nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn) and others. In the subtropical open ocean, surface nutrient concentrations are chronically low and often limit NPP. Enhanced stratification, induced by ocean warming, alongside changes to natural and anthropogenic supply of fixed N (Chien et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2014; Wrightson and Tagliabue, 2020), P (Barkley et al., 2019) or Fe (Liu et al., 2022) to the global ocean are likely to perturb the magnitude and ratio at which nutrients are supplied to phytoplankton (Peñuelas et al., 2013), potentially expanding or intensifying nutrient limited ocean regions (Bopp et al., 2013; Chien et al., 2016; Lapointe et al., 2021). Detecting and understanding how nutrients regulate phytoplankton distribution, growth and activity is key to estimating the magnitude and direction of contemporary and future NPP, reducing uncertainty and assessing risks to ecosystem services (Tagliabue et al., 2021).

The nutrient that limits phytoplankton growth can be identified by adding single or multiple nutrients to seawater and measuring phytoplankton growth or other properties over time (Browning and Moore, 2023; Mahaffey et al., 2014; Mills et al., 2004; Moore et al., 2008). In addition, advances in “-omics” have enabled identification of protein biomarkers related to nutrient acquisition or stress in marine phytoplankton (Chappell et al., 2012; Hawco et al., 2020; Held et al., 2020, 2026; Rouco et al., 2018; Saito et al., 2014, 2015; Ustick et al., 2021). Systems-level interpretation of incubation results and biomarker abundances is needed to disentangle the effects of nutrient biogeochemistry and biological plasticity/activity. For instance, in low-phosphate regions dominated by the ecologically important picocyanobacteria, Prochlorococcus, phosphate addition experiments imply a lack of P stress, whereas genomic data identifies large areas of P stress for Prochlorococcus (Browning and Moore, 2023). This mismatch may be due to the flexibility in P acquisition strategies (Duhamel et al., 2021; Martínez et al., 2012; Martiny et al., 2006, 2009; Moore et al., 2005; Ostrowski et al., 2010; Scanlan et al., 1993; Tetu et al., 2009). Phosphate limited phytoplankton can deploy an array of strategies to acquire alternative sources of P from dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP) including esters (Sebastian and Ammerman, 2009; Tetu et al., 2009), polyphosphate (Moore et al., 2005), phosphite (Martínez et al., 2012) and phosphonate (Ilikchyan et al., 2010) or substituting P-rich lipids with P-free alternatives (Van Mooy et al., 2009). A hydrolytic metalloenzyme group, alkaline phosphatases, are responsible for cleaving P from esters (Hoppe, 2003). Enhanced activity of alkaline phosphatase (AP) has been used as an indicator of P limitation (Mahaffey et al., 2014; Su et al., 2023) although the substrate specificity (Srivastava et al., 2021), cellular localisation (Luo et al., 2009), AP allocation between ecotypes (Moore et al., 2005), uncertainty in the contribution of different phytoplankton groups to total enzyme activity (Held et al., 2026; companion study to this manuscript)) and lack of knowledge on the efficiency of different AP enzymes raises uncertainties. Collectively, the flexibility in P acquisition strategies, as well as the perceived ability of Prochlorococcus to readily satisfy their P demands at ultra-low concentrations of phosphate (Lomas et al., 2014) has led to the idea that Prochlorococcus evade nutrient stress, particularly by remodelling their proteomes.

Comparing the physiological response of two ecologically important picocyanobacteria, Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus, to P stress demonstrates the complexity of deciphering resource limitation in mixed populations, between species, or even between strains of the same species. Synechococcus possess genes encoding a high affinity periplasmic phosphate binding protein (pstS) and transport system (pstABC), as well as genes encoding proteins essential for accessing organic P via alkaline phosphatase (phoA) and phosphonatase (phnC, D, E, (Moore et al., 2005; Scanlan et al., 1993; Tetu et al., 2009). When phosphate is scarce, Synechococcus has been shown to upregulate pstS, pstABC and phoA (Moore et al., 2005; Tetu et al., 2009), the regulator gene ptrA (Ostrowski et al., 2010) and the recently described high affinity AP gene psip1 (in clade III only (Torcello-Requena et al., 2024), with a measurable increase in AP activity (Moore et al., 2005, Torcello-Requena et al., 2024), implying that expression of these genes is indicative of P stress (Moore et al., 2005, Torcello-Requena et al., 2024). However, clade specific variations in response to phosphate limitation have been observed in situ (Sohm et al., 2016; Torcello-Requena et al., 2024) and in culture (Moore et al., 2005). While Prochlorococcus also possesses pstS and pstABC and has been shown to upregulate these genes alongside phoA under phosphate deplete conditions (Martiny et al., 2006), strain specific variations in its ability to access organic P also exist. For example, while the two most prevalent high light (HL) clades, MED4 (HL1) and MIT9312 (HLII) can grow solely on phosphate, MED4 grows on a wider range of organic P compounds, possess a high affinity AP (psip1, Torcello-Requena et al., 2024) and dramatically increases AP activity when P starved compared to MIT9312 (Moore et al., 2005).

In addition to species and clade specific responses across the microbial realm, AP enzymes are dependent on a metal co-factor, with Zn and/or cobalt (Co) required for the protein PhoA (Coleman, 1992) and Fe and calcium for the proteins PhoX and PhoD (Rodriguez et al., 2014; Yong et al., 2014) and Psip1 (Torcello-Requena et al., 2024). Although the 130 active sites of PhoA and PhoX in marine microbes have yet to be biochemically characterised, their metal requirements have been estimated assuming they are like the model organism, Escherichia coli and based on supporting evidence that the enzymes respond to the metals that they are expected to contain (Cox and Saito, 2013; Mikhaylina et al., 2022; Ostrowski et al., 2010). However, homology-based annotation of enzymes is challenging and therefore the annotations herein should be considered putative. The trace-metal content of these proteins creates the potential for trace metals to control P acquisition via regulation of AP activity leading to Fe-P or Zn-P co-limitation (Browning et al., 2017; Duhamel et al., 2021; Held et al., 2026; Mahaffey et al., 2014). Observations of an accelerating stoichiometry of Co in the western North Atlantic has led to hypotheses for the potential for Co use in oceanic alkaline phosphatases too (Held et al., 2026; Jakuba et al., 2008; Saito et al., 2017). In culture studies, Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus have been shown to have absolute requirements for Co but not Zn under replete P conditions (Hawco et al., 2020; Saito et al., 2002; Sunda and Huntsman, 1995) but Synechococcus benefits from available Zn to produce AP under P scarcity (Cox and Saito, 2013). Thus, knowledge of the phytoplankton community structure, alongside their nutritional preferences and enzyme characteristics is key in deciphering nutrient limitation in the ocean.

This study measures the biological response to nutrient transitions in the North Atlantic Gyre. Here, the western basin is heavily influenced by Saharan aeolian dust (Jickells, 1999), while the eastern basin borders the upwelling system off northwest Africa (Menna et al., 2016). Both upwelling and dust deliver scarce resources to the region, creating strong gradients in nutrients and trace metals (Gross et al., 2015; Kunde et al., 2019; Reynolds et al., 2014; Sebastián et al., 2004) influencing productivity (Moore et al., 2008), DOP dynamics (Liang et al., 2022) and marine dinitrogen (N2) fixation (Moore et al., 2009). Here, we exploit these strong natural gradients in nutrient and trace metal resources and biological activity to investigate nutrient acquisition strategies of natural assemblages of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus.

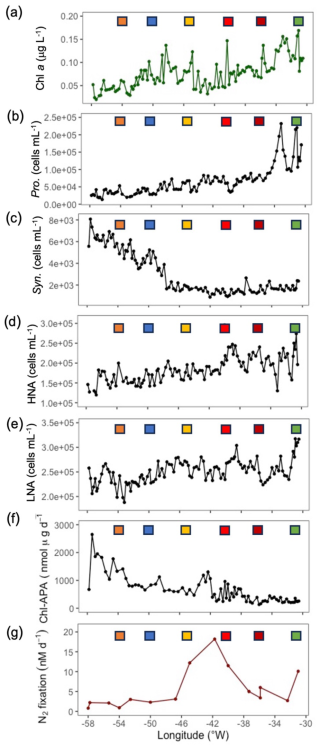

Alongside measurements of biogeochemical states, specifically nutrients, dissolved iron, zinc, cobalt and DOP and biological rates, including AP activity and N2 fixation, we investigated biological activity with non-targeted metaproteomics and quantitative targeted proteomics of the high affinity phosphate binding protein, PstS, and two alkaline phosphatases, PhoA and PhoX in Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus (Table 1). From the non-targeted metaproteomics analyses we specifically focus on proteins indicative of N acquisition (P-II, UrtA, AmtB) and proteins involved in iron (ferredoxin), zinc (zinc peptidase and transporter) and B12 (cobalamin synthetase) metabolism (Table 1). This allows us to firstly investigate the potential for Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus to be phosphorus stressed in the subtropical Atlantic, challenging the view that the can avoid P limitation. We hypothesised that zonal gradients in proteins would reflect nutrient stress. We then assessed the potential for P acquisition to be regulated by the availability of DOP, Fe and Zn, or Co. We hypothesised that the distribution of PhoA and PhoX would reflect rates of AP and alongside Fe and Zn, the limiting trace metal. We augmented in-situ sampling with nutrient bioassays, complimentary to those reported by Held et al., 2026 (companion manuscript), to further assess the potential for DOP substrate, alongside metals Fe and Zn to regulate AP activity and applied a quantitative proteomic approach targeting PstS, PhoA and PhoX only. Finally, we critically assessed our different approaches to delineate nutrient controls of the distribution and physiological strategies of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus, highlighting the nuanced insights gained when bringing together biogeochemical measurements alongside “-omics” (Saito et al., 2024).

2.1 Sample collection from surface waters

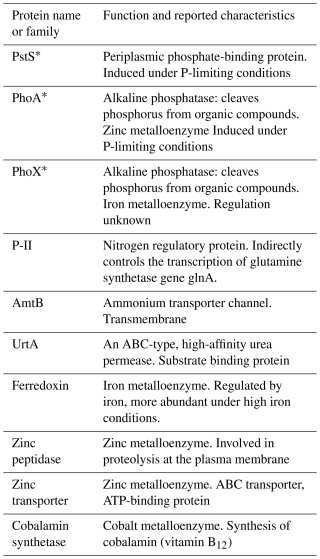

Samples were collected on a zonal transect between Guadeloupe and Tenerife at approx. ∼ 22° N between 26 June and 12 August 2017 onboard the RRS James Cook (JC150, Fig. 1a). Sea surface temperature (SST) was measured via the underway seawater system using Seabird sensors. Using a trace-metal clean towed FISH and a Teflon diaphragm pump (Almatec A-15), seawater samples were collected every 2 h, at a resolution of ∼ 25 km, from ∼ 3 m below the surface (Fig. 1a), with seawater flow terminating into a class-100 clean air-laboratory.

Figure 1(a) Locations sampled during JC150 from the trace metal clean towed FISH (black circles) and stations (coloured squares) and surface ocean properties including (b) sea surface temperature (°C), (c) phosphate (nM), (d) dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP, nM), (e) nitrate + nitrite (N + N, nM), (f) ammonium (nM). Note that data from JC150 station 1 (test station) has not been included in this manuscript due to the strong riverine influence (Kunde et al., 2019). Map produced using Ocean Data View (ODV). Schlitzer, Reiner, Ocean Data View, http://odv.awi.de (last access: 24 July 2024), 2023.

2.2 Biogeochemical states and rates

Using unfiltered seawater samples from the towed FISH, concentrations of nitrate plus nitrite (Brewer and Riley, 1965), phosphate (Kirkwood 1989) and ammonium (Jones, 1991) were analysed onboard according to GO-SHIP nutrient protocols (Becker et al., 2020). Using filtered seawater from the towed FISH (Sartobran, Sartorius, µm polyethersulfone membrane), concentrations of dissolved iron (Kunde et al., 2019) were measured onboard while concentrations of dissolved zinc (Nowicki et al., 1994) were determined at the University of Southampton. Concentrations of DOP were determined at the University of Liverpool using a modified version of Lomas et al. (2010) as described by Davis et al. (2019). Using unfiltered seawater from the towed FISH, rates of alkaline phosphatase were determined onboard every 4 h or ∼ 50 km (Davis et al., 2019). Enzyme kinetic parameters were determined at each station by incubating unfiltered surface seawater with various concentrations of the synthetic fluorogenic substrate 4-methylumbeliferyll-phosphate (MUFP, Sigma Aldrich) and measuring the change in fluorescence for 8 hours (as described by Davis et al., 2019). The maximum hydrolysis rates (Vmax) and the half saturation constant (Km) were determined using the Hanes-Woolf plot graphical linearization of the Michaelis-Menten equation following Duhamel et al. (2011). Prochlorococcus, Synechococcus (or Parasynechococcus, (Coutinho et al., 2016) and high and low nucleic acid bacteria (HNA and LNA, respectively) were enumerated every 2 h at Plymouth Marine Laboratory using flow cytometry (Tarran et al., 2006). Surface ocean concentrations of chlorophyll a (on GF/F) were determined on every sample (Welschmeyer, 1994). Concentrations of dissolved cobalt were measured in separate samples collected from 40 m from 4 stations only using high resolution inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (HR-ICP-MS), preceded by UV-digestion and off-line preconcentration into a chelating resin (WAKO) at the University of Southampton (Lough et al., 2019; Rapp et al., 2017).

2.3 Global metaproteomic analysis

At 7 stations, McLane pumps were deployed to 15 m (see Table S1 for deployment details). Data from station 1 was omitted from this study due to significant riverine influence (Kunde et al., 2019). Pumps were fitted with a trace metal clean mini-MULVS filter head. Between 17 and 359 L of seawater was filtered through a 51 µm (Nitex), 3 µm (Versapor) and 0.2 µm (Supor) filter stack. Filters were immediately frozen at −80 °C, with subsequent transportation and storage at −80 °C. Protein biomarker analysis was conducted on the 0.2 µm filter, representing the 0.2 to 3 µm particle fraction. Briefly, upon return to the laboratory, the total microbial protein was extracted using a detergent based method. The filter was unfolded and placed in an ethanol rinsed tube, then covered in 1 % SDS extraction buffer (1 % SDS, 0.1 M Tris HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM EDTA), incubated at room temperature for 10 min, then at 95 °C for 10 min, and then shaken at room temperature for 1 h. The extract was decanted and clarified by centrifugation before being concentrated by 5 kD membrane centrifugation to a small volume, washed in extraction buffer, and concentrated again. The total protein concentration was determined by BCA assay (kit) at this time. The proteins were precipitated in cold 50 % methanol 50 % acetone 0.5 mM HCl at 20 °C for one week, collected by centrifugation at 4 °C, and dried by vacuum. Purified protein pellets were resuspended in 1 % SDS extraction buffer and redissolved for 1 h at room temperature. Total protein was again quantified by BCA assay to assess recovery of the purification.

Extracted proteins were immobilized in a small volume polyacrylamide tube gel using a previously published method (Lu and Zhu, 2005; Saito et al., 2014). LC-MS/MS grade reagents were used and all tubes were ethanol rinsed. The gels were fixed in 50 % ethanol, 10 % acetic acid, then cut into 1 mm cubes and washed in 50:50 acetonitrile: 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate for 1 h at room temperature, then washed again in the same solution overnight. Next, the gels were dehydrated by acetonitrile treatment before protein reduction by 10 mM dithiothreitol treatment at 56 °C for 1 h with shaking. Gel pieces were rinsed in 50:50 acetonitrile: ammonium bicarbonate solution, then proteins were alkylated by treatment with 55 mM iodacetamide at room temperature for 1 h with shaking. Gels were again dehydrated by acetonitrile treatment and dried by vacuum. Finally, proteins were digested by treatment with trypsin gold (Promega) prepared in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate at the ratio of 1:20 µg trypsin: ug total protein overnight at 37 °C with shaking. The next morning, any supernatant was decanted into a clean microfuge tube, and 50 µL protein extraction buffer (50 % acetonitrile, 5 % formic acid in water) was added to the gels, incubated for 20 min, centrifuged and collected. The extraction was repeated and combined with the original supernatant. Peptides were concentrated to approximately 1 µg total protein per µL solution by vacuum at room temperature. 10 µL or 10 µg were injected per analysis.

Global metaproteome analysis, which is conducted with no prior determined targets, was performed in Data-Dependent-Acquisition (DDA) mode using Reverse Phase Liquid Chromatography – active modulation – Reverse Phase Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (RPLC-am-RPLC-MS) (McIlvin and Saito, 2021). RPLC-am-RPLC-MS involves two orthogonal chromatography steps, which are performed in-line on a Thermo Dionex Ultimate 3000 LC system equipped with two pumps. The first separation was on a PLRP-S column (200 µm × 150 mm, 3 µm bead size, 300 Å pore size, NanoLCMS Solutions) using an 8 h pH 10 gradient (10 mM ammonium formate and 10 mM ammonium formate in 90 % acetonitrile), with trapping and elution every 30 min onto the second column. The second separation occurred in 30 min intervals on a C18 column (100 m × 150 mm, 3 µm particle size, 120 Å pore size, C18 Reprosil-God, Maisch, packed in a New Objective PicoFrit column) using 0.1 % formic acid and a 0.1 % formic acid in 99.9 % acetonitrile. The eluent was analyzed on a Thermo Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer with a Thermo Flex ion source. MS1 scans were monitored between 380 and 1580, with an 1.6 MS2 isolation window (CID mode), 50 ms maximum injection time and 5 s dynamic exclusion time.

Resulting spectra were searched in Proteome Discoverer 2.2 with SequestHT using a custom DNA sequence database consisting of over 30 genomes from cyanobacteria isolates and metagenomic data from the Pacific and Atlantic oceans (including metagenomes from Metzyme and Geotraces cruise GA03). Annotations were derived using BLASTp against the NCBI non-redundant protein database. The corresponding protein FASTA file is available with the raw mass spectra files (see Supplement S1). SequestHT parameters were set to 10 ppm for the parent ion, 0.6 Da for the fragment, with cysteine modification (+57.022) and variable methionine (+16.0) and cysteine oxidation allowed. Protein identifications were made using Protein Prophet in Scaffold (Proteome Software) at the 95 % peptide confidence level, resulting in < 1 % protein and peptide FDRs. Details of the peptides identified relative to protein name and organism can be found in Table S2 and the protein report and analytical details can be found in Supplement S2.

Global metaproteome protein abundances are reported in normalized spectral counts. The normalization is performed by summing the total number of spectra in each sample, calculating the average number of spectra across all the samples, and then multiplying each spectrum count by the average count over the sample's total spectral count. This is done to control for small differences in the amount of sample injected into the mass spectrometer.

2.4 Quantitative proteomics analysis

A small number of tryptic peptides were selected for absolute quantitative analysis in the samples from nutrient addition experiments (see Sect. 2.5 for details) and were analysed as described in detail by Held et al. (2026) (companion manuscript). The amino acid sequence for the protein biomarkers quantified in this study (PstS, PhoA, PhoX) for Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus are summarised in Table S3 and peptide report and analytical details are found in Supplement S3.

2.5 Nutrient bioassay experiments

Trace-metal clean sampling and incubation protocols used to setup onboard bioassays are described in detail in the Supplement S4. Aliquots of Fe, Zn and Co solutions were added to unfiltered seawater to investigate metal limitation of alkaline phosphatase and results are reported in Held et al. (2026). Alongside these experiments, we added DOP alone or with Fe and Zn to investigate the potential for organic P availability to influence AP activity at stations 2 and 3 only, where concentrations of DOP were low (< 80 nM, Fig. 1a and e, Table S4), and the results are reported here. Trace-metal clean 20 L carboys were triple rinsed with unfiltered seawater collected from 40 m (to avoid contamination from the ship) via the FISH and filled and amended accordingly (Table S4). At the start and end of 48 h, we measured phytoplankton biomass (chlorophyll a, abundance of Prochlorococcus, Synechococcus) and AP activity. After 48 h, we collected samples to quantify protein concentration (PstS, PhoA and PhoX) as described in Sect. 2.4 (Table S3). Incubations were conducted in triplicate. However, due to the biomass (therefore volume) required for protein analysis, we were unable to collect samples from three incubation bottles for further analyses. Instead, all measurements were collected from two incubation bottles, except aliquots for determination of AP, which was collected from three incubation bottles. To compare the change in states or rates in treatments relative to the control, we considered a significant change in a property to occur when the mean of the property in the amended incubation was 2-times higher (or lower) than the mean control incubation. Incubations were conducted in a temperature controlled container set to a temperature measured at 40m (between 25 and 27 °C) and with 12:12 h light : dark cycle simulated by LED light panels (Part no: LED-PANEL-300-1200-DW and LED-PANEL-200-6-DW, Daylight White, supplier Power Pax UK Limited).

3.1 Zonal trends in nutrients, cell abundance and biological rates

Strong zonal gradients were evident in surface temperature and phosphorus concentrations. From west to east, SST decreased by ∼ 3 °C (Fig. 1b), phosphate increased by ∼ 15 nM (Fig. 1c) and DOP increased 3-fold (from ∼ 50 nM to ∼ 150 nM, Fig. 1d). By comparison, there were no clear zonal trends in fixed nitrogen, with concentrations of nitrate plus nitrate (N + N, herein nitrate) ranging from < 10 nM to ∼ 40 nM (Fig. 1e) and ammonium, which ranged from 3 to 21 nM, being highest at stations 5 and 6 (Fig. 1f).

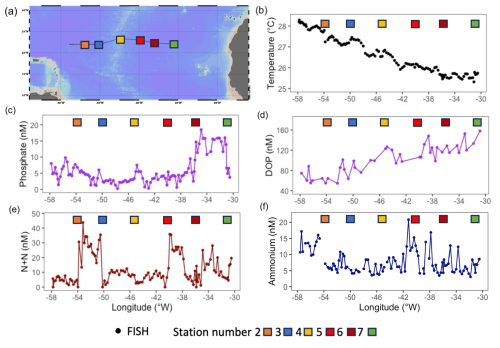

There was a clear zonal trend in dissolved Fe concentrations, which decreased west to east by ∼ 1.0 nM (Fig. 2a) owing to enhanced Saharan dust deposition in the western Atlantic Ocean (Kunde et al., 2019). In contrast, Zn concentrations were variable throughout the transect (ranging from 0.04 to 0.8 nM, Fig. 2b) and cobalt was constant (∼ 11 to 14 pM, data not shown).

Figure 2Zonal gradients in (a) dissolved iron concentrations (nM, from Kunde et al., 2019) and (b) dissolved zinc concentrations (nM). Samples captured from the towed FISH at ∼ 7 m. Coloured square represent stations sampled during JC150 (see Fig. 1 for station names).

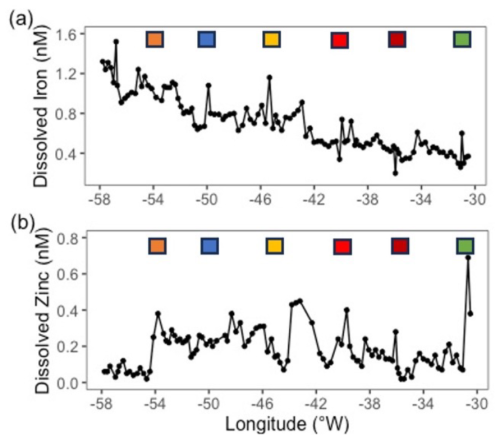

Figure 3Zonal gradients in (a) chlorophyll a concentrations (µg chl a L−1) and the abundance of (b) Prochlorococcus (cells mL−1), (c) Synechococcus (cells mL−1), (d) high nucleic acid bacteria (HNA, cells mL−1) and (e) low nucleic acid bacteria (LNA, cells mL−1), (f) chlorophyll a – corrected rates of alkaline phosphatase (nmol P mg chl d−1) and (g) mean rates of dinitrogen (N2) fixation (nM N d−1) with error bars as standard deviation of triplicate incubations. Samples captured from the towed FISH at ∼ 7 m. Coloured squares represent stations sampled during JC150 (see Fig. 1 for station names).

Microbial biomass, picocyanobacteria abundance and biological rates exhibited strong zonal gradients. From west to east, there were increases in chlorophyll aconcentration (Fig. 3a) and Prochlorococcus cell abundance (Fig. 3b) whereas Synechococcus cell abundance decreased (Fig. 3c). HNA and LNA bacterial abundance (Fig. 3d and e, respectively) also increased from east to west. There was also a 4-fold decrease in chlorophyll corrected APA (from > 2000 nmol P µg chl a d−1 to < 500 nmol P µg chl a d−1, Fig. 3f), likely in response to the observed gradient in P/DOP availability (Mahaffey et al., 2014 , Fig. S1a, S1b).

In addition, the abundance of key diazotrophs Trichodesmium and UCYN-A increased from west to east (Cerdan-Garcia et al., 2022). Although rates of N2 fixation in the east exceeded those in the west (3 to 10 nM d−1 and < 3 nM d−1, respectively), the highest rates were in the central transect between stations 4 and 5 (12 to 18 nM d−1, Fig. 3g).

These zonal gradients in hydrography, nutrients, biological rates and picocyanobacteria create two contrasting regions – one in the west (west of 46° W or west of station 4) and one in the east (east of 46° W or east of station 4). Thus, quantitative comparisons of key characteristics can be drawn between station 2 at 54° W and station 7 at 31° E (Fig. 1a, Table 2). Compared to the east, conditions in the west were characterized by notably higher dissolved Fe and ammonium concentrations (3 to 4-fold higher), APA (4-fold higher) and Synechococcus abundance (2-fold higher). In contrast, the east was characterized by relatively high phosphate, DOP, chlorophyll a, Prochlorococcus abundance, rates of N2 fixation, Trichodesmium and UCYN-A abundances (Table 2).

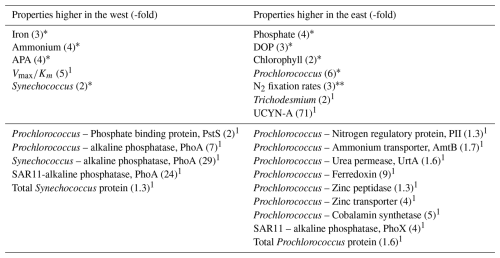

Table 2Summary of states, rates and protein biomarkers that are higher in the west (left hand column) or east (right hand column) of the transect. The numbers in brackets represent the approximate -fold difference between west and east. Properties not reported (e.g. dissolved zinc, Syn-UrtA) displayed no clear difference between west and east. We note if the differences in properties are statistically significant (*, p<0.05) or not significant (, p>0.05). 1 indicates insufficient replication or measurements for statistical analysis.

Based on these biogeochemical parameters, the phosphate-binding protein PstS, which is expressed under P-limiting conditions, would be expected to be prevalent throughout the transect consistent with low phosphate concentrations across the entire transect. Protein biomarkers would also be expected to indicate higher alkaline phosphatase (AP) abundances in the west, corresponding with the observed trends in APA. In addition, PhoX would be expected to be prevalent in the Fe-rich west, with greater prevalence of Fe-stress biomarkers in the east.

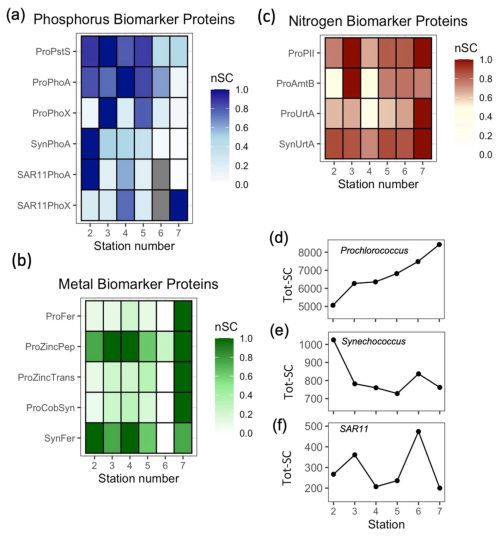

3.2 Zonal gradients in phosphorus acquisition proteins

3.2.1 Prochlorococcus

Zonal gradients in Procholorocuccus P proteins generally indicate more severe P stress in the west. Prochlorococcus (HLII) specific P proteins PstS and PhoA (Pro-PstS and Pro-PhoA, respectively) were almost 2-fold and 7-fold higher in the west relative to the east (Fig. 4a, Table 2), whereas there was no clear zonal trend in PhoX (Pro-PhoX, Fig. 4a). Similar zonal trends for PstS (Fig. S2a), PhoA (Fig. S2b) and PhoX (Fig. S2c) were observed irrelevant of the strain or ecotype of Prochlorococcus, thus reflecting true biological regulation within the entire Prochlorococcus community, rather being contingent on variation in the abundance of one clade/strain across the transect. Moreover, the increase in total Prochlorococcus protein (Fig. 4d) alongside Prochlorococcus cell abundance (Fig. 3b) in the east suggests that trends in untargeted metaproteomics analysis are representative of microbial community structure. Thus, assuming all observed Prochlorococcus cells possess both genes, the higher Pro-PstS and Pro-PhoA in the west, where Prochlorococcus abundance was lower, reflects a physiological response to low phosphorus availability.

Figure 4Zonal gradients in the spectral counts (SC) of biomarker proteins in Prochlorococcus (Pro-), Synechococcus (Syn-) and SAR11 for (a) Phosphorus biomarker proteins; PstS, PhoA and PhoX, (b) Iron, zinc and cobalt biomarker proteins; Ferredoxin (Fd) and Zinc peptidase (ZincPep), Zinc transporters (ZincTrans) and Cobalamin Synthetase (CobW) (c) Nitrogen biomarker proteins: PII, AmtB and UrtA and (d) total protein for Prochlorococcus, (e) Synechococcus and (f) SAR11, presenting an independent measure of biomass. See Table 1 for details of the protein functions. nSC represents normalized spectral counts, which represents the spectral counts normalized to the maximum value of each protein across 6 stations. Tot-SC represents the sum of all normalized spectral counts for Prochlorococcus, Synechococcus or SAR11.

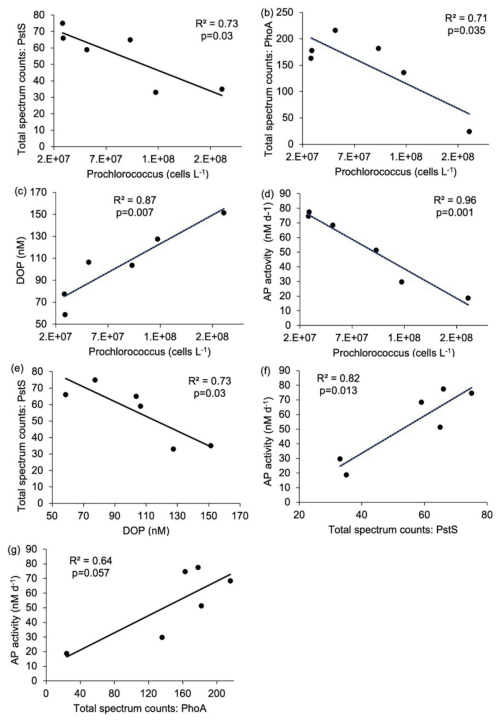

Correlations between Prochlorococcus abundance and other measured parameters also indicate a physiological response to nutrient availability. Prochlorococcus cell abundance was negatively correlated with Pro-PstS (Fig. 5a), Pro-PhoA (Fig. 5b) and APA (Fig. 5d). APA was also positively correlated with Pro-PstS and Pro-PhoA (Fig. 5f and g). Conversely, DOP concentration was positively correlated with Prochlorococcus cell abundance (Fig. 5c) but negatively correlated with Pro-PstS (Fig. 5e). Together these data suggest Prochlorococcus in the west were more P stressed than those in the east.

Figure 5Relationship between (a) Prochlorococcus cell abundance (cells L−1) and Pro-PstS (total spectrum counts), (b) Prochlorococcus cell abundance (cells L−1) and Pro-PhoA (total spectrum counts), (c) Prochlorococcus cell abundance (cells L−1) and dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP, nM), (d) Prochlorococcus cell abundance (cells L−1) and rates of alkaline phosphatase (APA, nM d−1), (e) DOP and Pro-PstS, (f) Pro-PstS and APA and (g) Pro-PhoA and APA. Results are linear regression as reported as R2 value and p-value. Relationships shown in (a) to (f) are considered statistically significant as p<0.05.

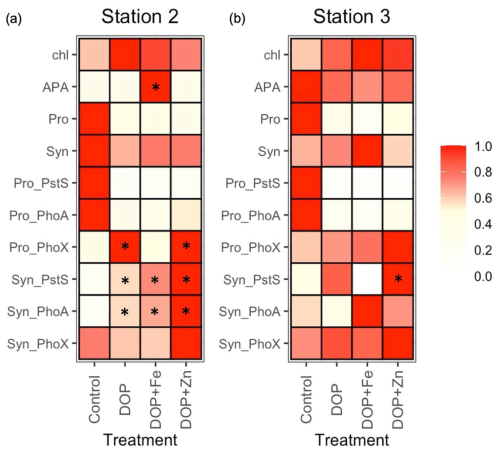

The bioassay experiments shed further light on the nutrient status of these communities. At station 2, mean chlorophyll a increased (from 0.075 to 0.120 µg L−1) after the addition of DOP alone, but with no increase in APA. Instead, DOP + Fe stimulated an increase in chlorophyll a (from 0.075 to 0.108 µg L−1) alongside an increase in mean APA (3.03 to 9.70 nM d−1, * denotes a 2-fold or greater increase relative to the control in Fig. 6a, Table S5). Pro-PhoX concentration more than doubled following DOP and, separately, DOP + Zn addition at station 2 (Fig. 6a), however insufficient understanding of the controls on PhoX limits interpretation of this observation at this time. By comparison, no significant changes in chlorophyll a or APA were observed at station 3 (Fig. 6b, Table S5).

Figure 6Fractional (scale 0 to 1) change in states, rates and individual proteins in Prochlorococcus (Pro_) and Synechococcus (Syn-) after the addition of dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP), DOP and iron (DOP + Fe) and DOP and zinc (DOP + Zn) at station 2 (a) and station 3 (b) for chlorophyll a(chl), rates of alkaline phosphatase activity (APA), Prochlorococcus (Pro), Synechococcus (Syn) and protein biomarkers PstS, PhoA and PhoX. Coloured squares represent the mean of duplicate or triplicate samples and are normalised as the fraction of the maximum of that property in each experiment. See Table S4 for a description of the experiments and Table S5 for raw data for all properties. * denotes a 2-fold or more change in the mean property relative to the control.

In the bioassays, DOP addition resulted in a decrease in the concentration of Pro-PstS and Pro-PhoA (Fig. 6a and b), implying P acquisition proteins were repressed in the presence of elevated DOP. These observations corroborate in-situ observations as Pro-PstS and Pro-PhoA both decreased to the east (Fig. 4a) where DOP and phosphate were elevated in surface waters (Fig. 1c and e). We interpret this DOP effect to be the result of DOP conversion to phosphate by alkaline phosphatase, and negative regulation of the Pho operon that controls both PstS and PhoA rather than DOP directly interacting with the regulatory system (Martiny et al., 2006). Alternatively, there may be another system that is directly regulated by DOP availability. For example, PtrA is an alternative phosphate-sensitive regulator identified in some Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus strains and that may be responsive to organic P (Ostrowski et al., 2010). However, flow cytometry-derived Prochlorococcus abundance declined in all experiments (Fig. 6a and b, Table S5), a common outcome for marine oligotrophs in bottle incubation experiments. It is unclear whether the observed decline in Pro-PstS and Pro-PhoA in the bioassays was due to a physiological response to elevated DOP or a decline in Prochlorococcus biomass, or a combination of the two.

That said, knowledge of the dominant Prochlorococcus clades in the Atlantic Ocean (Johnson et al., 2006) alongside selection of protein markers to target specific clades allows us to interpret ecotype-level responses in experiments and in the biogeochemical transect (Saito et al., 2015). For example, Prochlorococcus HLII, the dominant clade in the oligotrophic subtropical ocean, can use ATP but no other organic P sources and minimally increases APA in response to P starvation as it lacks regulatory genes that respond to P-limitation (e.g. ptrA, (Moore et al., 2005). By contrast, HL1 (MED4), which possesses both regulatory genes involved in phosphorus metabolism, phoBR and ptrA (Martiny et al., 2006), can grow on a variety of organic P substrates and substantially increases AP activity when grown on organic P relative to phosphate (Moore et al., 2005), suggesting HL1 can upregulate AP in response to external organic P levels (Moore et al., 2005). In the global metaproteomes, a west to east increase in Prochlorococcus ecotypes HL1 (Fig. S3a) and HLII (Fig. S3b) was detected, which accompanied the increases in cell abundance and total Prochlorococcus protein. HLI (MED4) is more prevalent in the eastern Atlantic (Zinser et al., 2007) and in this study, we observed an increase in the contribution of HLI to total ecotype from 6 % to 8 % (Fig. S3c). The eastward increase in HL1 abundance alongside its increased plasticity to grow on a variety of organic P substrates may explain why Prochlorococcus abundance is higher where DOP is elevated in the eastern Atlantic.

3.2.2 Synechococcus

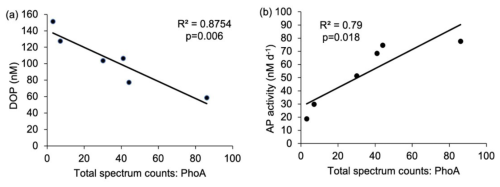

PhoA in Synechococcus (Syn-PhoA) was 29-fold higher in the west than the east (Fig. 4a, Table 2) and significantly negatively correlated with DOP (Fig. 7a) and positively correlated with APA (Fig. 7b). Unlike Prochlorococcus, there was no correlation between cell abundance and proteins, DOP or AP (Fig. S4). Other Synechococcus P-related proteins (Syn-PstS and Syn-PhoX) were not detected in the sampled metaproteome but might have been present at concentrations below detection limits. Synechococcus abundance (Fig. 3c), APA (Fig. 1f), Syn-PhoA (Fig. 4a) and total Synechococcus protein count (Fig. 4e) were higher in the west than in the east.

Figure 7Relationship between (a) Synechococcus PhoA (total spectral counts) and concentrations of DOP (nM) and (b) Synechococcus PhoA (total spectral counts) and alkaline phosphatase activity (AP, nM d−1). The R2 value and p-values are reported. p<0.05 indicates that the relationship is statistically significant.

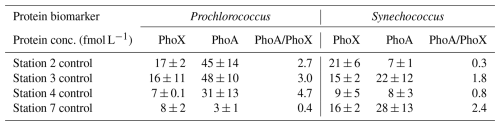

In the bioassays at station 2, the addition of DOP, DOP + Fe and DOP + Zn resulted in declines in Synechococcus abundance by 23 % to 35 % relative to the control (Fig. 6a, Table S5). However, associated biomarker proteins increased. Mean concentrations of Syn-PstS increased by 2.7-, 3.5- and 4.7-fold after the addition of DOP, DOP + Fe and DOP + Zn, respectively, relative to the control after 48 h bioassays (Fig. 6a, Table S5). Similarly, the mean concentration of Syn-PhoA increased by 3.6-, 4.3- and 6.4-fold after the addition of DOP, DOP+Fe and DOP+Zn, respectively (Fig. 6a, Table S5). It is unclear why production of both Syn-PstS and Syn-PhoA was more stimulated after the addition of DOP+Fe than DOP at station 2, assuming PhoA contains Zn or Co, and not Fe as metal co-factors (Coleman, 1992). However, replication was low (n= 2) and variability between replicates was high, limiting a statistically robust interpretation.

At station 3, Synechococcus abundance increased by 12 % and 53 % following DOP and DOP + Fe addition, respectively but decreased after DOP + Zn addition (Fig. 6b, Table S5). The change in protein concentration after nutrient additions was less pronounced at station 3 than station 2 (Table S5). DOP additions induced a 1.8-fold increase in Syn-PstS and a 30 % decrease in Syn-PhoA. Addition of DOP + Fe induced a 90 % decrease in Syn-PstS and a 1.7-fold increase in Syn-PhoA while addition of DOP+Zn induced a 2.1-fold increase in Syn-PstS and a 1.2-fold increase in Syn-PhoA (Fig. 6b, Table S5). There was no consistent change in Syn-PhoX after the addition of DOP, DOP + Zn or DOP + Fe, with Syn-PhoX increasing or decreasing by 20 % to 40 % at both stations (Fig. 6b, Table S5).

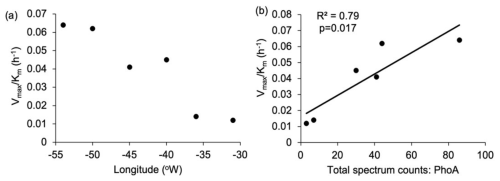

In-situ measurements and bioassays converge to imply that Synechococcus is reliant upon organic P accessed via APA. The zonal trends and bioassay results agree with culture experiments demonstrating that Syn-PstS and Syn-PhoA are produced in the presence of DOP and Zn to increase P acquisition when phosphate is low (Cox and Saito, 2013). Higher APA and prevalence of Syn-PhoA in the low DOP and phosphate west implies that Synechococcus was P stressed. Enzyme kinetic bioassays indicate higher AP enzyme efficiency in the west (Fig. 8a), with enzyme efficiency positively correlated with Syn-PhoA (p= 0.017, Fig. 8b). Thus, Syn-PhoA potentially governs this trend of enzyme efficiency, suggesting DOP hydrolysis was more efficient in the west than the east.

Figure 8Enzyme efficiency for alkaline phosphatase was calculated as the ratio between Vmax and Km (h−1); (a) zonal gradient in enzyme efficiency, indicating higher enzyme efficiency in the western compared to the eastern subtropical Atlantic and (b) positive significant (p= 0.017) relationship between Syn-PhoA and enzyme efficiency.

A west-east gradient was also observed for PhoA in SAR11 (Fig. 4a), which is an abundant aerobic chemoheterotrophic alphaproteobacteria contributing to LNA bacterial counts (Fig. 3e). The abundance of both HNA and LNA (Fig. 3d and e, respectively) and total SAR11 protein (Fig. 4f) increased from west to east. However, SAR11-PhoA decreased 24-fold and SAR11-PhoX increased 4-fold (Fig. 4a, Table 2) despite dissolved Fe concentrations being higher in the west relative to the east. The mechanism for this discrepancy is unclear. However, PhoA is efficient at hydrolysing DOP under low P conditions and culture studies show that organic P is an important source of P for SAR11, representing up to 70 % of its cellular P requirement when phosphate is non-limiting (Grant et al., 2019). Thus, we speculate that SAR11 might strategically use PhoA in the west with the zonal patterns in SAR11-PhoA and PhoX likely reflecting the preferential acquisition of DOP over phosphate. This further supports the premise that PhoA is an indicator of DOP acquisition across marine microbial taxa (Steck et al., 2025; Ustick et al., 2021).

The decline in Synechococcus abundance and Syn-PhoA, despite the increase in DOP in the east suggests other factors, such as resource availability or competition with other microorganisms including Prochlorococcus, inhibited growth of Synechococcus in the east. Zinc concentrations decreased eastwards from ∼ 0.35 nM to 0.15 nM. Briefly, bioassays conducted during the same expedition indicated that Zn addition stimulated a 2- to 4-fold fold increase in Syn-PstS and Syn-PhoA after a 48 h incubation period (Held et al., 2026; companion manuscript), corroborating a role for zinc in PhoA metabolism. Cobalt also stimulated increases in Syn-PstS and Syn-PhoA, representing new field evidence for Co influencing AP (Held et al., 2026; companion manuscript). Co may effectively substitute Zn at the active site of PhoA within marine cyanobacteria, consistent with trends observed in accelerating Co stoichiometry and APase abundances in the North Atlantic Ocean (Saito et al., 2017).

3.3 Non-targeted metaproteomic indicators of nutrient status in picocyanobacteria

Higher PstS and PhoA in the west compared to the east, alongside the positive relationship between Pro-PstS, Pro-PhoA and Syn-PhoA with AP activity and negative relationship with DOP corroborate that these protein biomarkers are P-stress biomarkers in both Prochlorococcus (Martiny et al., 2006; Moore et al., 2005; Reistetter et al., 2013) and Synechococcus (Scanlan et al., 1993; Tetu et al., 2009). However, DOP addition stimulated distinct biomarker responses in Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus (Fig. 6, Table S5). For Prochlorococcus, DOP addition reduced Pro-PstS and Pro-PhoA but increased PhoX after 48 h relative to the control (Fig. 6, Table S5). In contrast, for Synechococcus DOP addition increased Syn-PstS and Syn-PhoA, with no change in PhoX (Fig. 6, Table S5). We intuit that the protein biomarkers changed due to a physiological response rather than change in cell abundance because the per cell protein content (Fig. S5) showed the same pattern (with the caveat that the protein is clade specific yet likely targeted a major ecotype, whereas cell abundance represents all cells). DOP addition stimulated a decrease in Pro-PstS and Pro-PhoA per cell and increase Pro-PhoA per cell relative to the control (Fig. S5a), whereas DOP addition stimulated an increase in Syn-PstS, Syn-PhoA and Syn-PhoX per cell (Fig. S5b).

Either the protein regulatory pathway differs between Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus, and/or the strain specific differences in quantified proteins is complicating our interpretation response of proteins across different strains. Here we describe evidence for the former hypothesis. In Prochlorococcus, the Pho regulon controls P-acquisition genes such as pstS (phosphate transporter) and phoA and includes the two-component regulatory genes, phoB and phoR (Martiny et al., 2006). The Pro-phoX gene is controlled by the pho regulon as it sits within a genomic island with other P stress responsive genes (Kathuria and Martiny, 2011). In contrast, Synechococcus (WH8102) has a two-tiered phosphate response system , where the PhoBR regulator controls pstS using a Pho box (Cox and Saito, 2013; Tetu et al., 2009) and second regulator, PtrA, controls one of the phoA phosphatase copies, Zn transport, and various other cellular processes (Ostrowski et al., 2010). The gene neighbourhood containing phoA (SYNW2391) in Synechococcus is also located near an efflux transporter and close to the ferric uptake regulator, Fur. To our knowledge, regulation of PhoX and its interaction with PhoA regulation in the marine picocyanobacteria is not well understood, but analysis of the gene neighbourhood in the model organism Prochlorococcus sp. NATL1A reveals that phoX is not within the phoA neighbourhood and is in the vicinity of a putative manganese transporter. For Synechococcus (WH8102), the position of phoX (SYN1799) is like Prochlorococcus and is located directly next to the futAB iron ABC transport system, consistent with the iron requirement of this enzyme. The separation of phoA and phoX within the genome in both Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus (at least in the representative strains described above) implies their regulation may be distinct in the different organisms. Consistent with prior observations (Browning et al., 2017; Mahaffey et al., 2014; Rouco et al., 2018), PhoA and PhoX may be regulated by both metals and phosphorus availability but the specific regulatory system in picocyanobacteria is complex and still unknown.

The alternative interpretation is that differences in strain specificity among the identified proteins explains the differences in the Prochlorococcus vs. Synechococcus response patterns. Proteins concentrations are measured by detecting peptides, and biological specificity (e.g. to strains or species) is determined by comparing the amino acid sequence of the peptide to isolate genomes or annotated MAGs. A least-common-ancestor (LCA) analysis can then be performed to assess the level of biological specificity that is represented by that peptide (Saunders et al., 2020) (Table S3, Supplement S3). The targeted peptides were selected based on their abundance in a preliminary metaproteomics analysis, suggesting that these were the most abundant proteins within the microbial community (see Held et al., 2026 for a more complete description of how targeted peptides were selected for this study region). Peptide sequences for up to 5 strains of Prochlorococcus were targeted with a focus on the HLII clade, particularly strain MIT9314, allowing comparison between proteins of the same strain. In contrast, protein sequences for Synechococcus were compared across clades because the peptide sequence for PhoA and PhoX targeted WH8102 (clade III) but the peptide sequence for PstS targeted RCC307 (clade X, Table S3). While co-occurring clades III and X are geographically positively correlated in warm oligotrophic waters (Sohm et al., 2008), RCC307 possesses a different putative alkaline phosphatase gene compared to WH8102 (likely PhoA, see Tetu et al., 2009). This mismatch in targeted strains and clades means that interpretation of the response of Synechococcus (and perhaps Prochlorococcus) to nutrient addition needs to be treated with some caution until the physiology and regulatory pathways of protein production are better understood. However, based on current knowledge of phosphate acquisition genes in marine Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus, we do expect that the targeted proteins/strains are major players in our study region.

3.4 Influence of trace metals on alkaline phosphatase and associated protein biomarkers

Unlike other cyanobacteria, where the trace metal availability aligns well with the biogeography of PhoA and PhoX (e.g. Trichodesmium, Rouco et al., 2018), there were no consistent trends between iron or zinc concentrations and proteins PhoX and PhoA respectively in this study. The distribution of Pro-PhoX from metaproteomes (Fig. 4a) did not reflect iron availability (Fig. 2a). Despite elevated iron in the west, Pro-PhoA concentrations were 2.7 to 4.7-fold higher than Pro-PhoX (reported fmol L−1, Table 3), with Pro-PhoX being greater than Pro-PhoA in the east where Fe was lowest (Fig. 2a). PhoX was not detected for Synechococcus in metaproteome analysis but was detected quantitatively at the start of bioassay experiments (Table 3). Syn-PhoX concentrations also did not reflect iron availability (Table 3) and there was no consistent trend in the ratio between Syn-PhoA and Syn-PhoX (Table 3). Zonal trends in quantitative versus metaproteome-derived Syn-PhoA were different and likely driven by differences in depth horizons sampled (40 m for experiments, 15 m for metaproteome analysis) as well as the different Synechococcus populations captured using quantitative peptide analysis (see Table S3, clade III and X) compared to metaproteomes.

Table 3Concentration of proteins (fmol L−1) PhoX and PhoA for Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus at the start of the nutrient bioassay experiments at stations 2, 3, 4 and 7 (see Fig. 1a for locations) to illustrate how the relative concentration and ratio of PhoA to PhoX differ between Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus and across the zonal transect.

The systems biology of the PhoX enzyme is poorly understood compared to that of PstS and PhoA, where the latter is known to be regulated by phosphate and zinc (Cox and Saito, 2013; Martiny et al., 2006; Ostrowski et al., 2010; Tetu et al., 2009). Despite the lack of correlation between trace metal availability, PhoA and PhoX in the surface ocean in this study, results from bioassays conducted during the same expedition (Held et al., 2026; companion manuscript) lends support to the potential for a direct metal control on APA (Browning et al., 2017; Jakuba et al., 2008; Mahaffey et al., 2014; Saito et al., 2017). In the west, Zn addition stimulated a 6-fold increase in Syn-PhoA relative to the control. Cobalt addition simulated a 7-fold increase in Syn-PhoA and 8-fold increase in Pro-PhoX. Finally, iron addition stimulated a 2-fold increase in Pro-PhoX in the iron-deplete eastern Atlantic (Held et al., 2026; companion manuscript).

Proteins relating to iron, zinc and B12 metabolism in Prochlorococcus increased in the east alongside the increase in Prochlorococcus cell abundance. Ferredoxin and zinc transporters increased eastward by 3 to 9-fold and protein annotated as CobW, a member of the COG0523 family implicated in metal chaperone functions (Edmonds et al., 2021) and Co chaperone for B12 synthesis (Young et al., 2021) also increased 3 to 10-fold (Fig. 4c). The eastward increase in three independent proteins (up to 10-fold) was greater than the increase in total protein for Prochlorococcus (∼ 1.6-fold) implying a regulated molecular increase in response to resource limitation or competition, rather than reflecting a change in biomass only. However, zinc protein annotations in Prochlorococcus are putative and alignment-based transporter annotations are unable to discern cognate metal use. In addition, the role of zinc in Prochlorococcus physiology is uncertain. Prochlorococcus does not have an obligate Zn requirement when phosphate is available (Saito et al., 2002), and Zn is highly toxic to a Pacific Ocean strain of Prochlorococcus (Hawco and Saito, 2018). In addition, while CobW is an abundant protein among the ∼ 20 genes involved in cobalamin biosynthesis, there are currently no known biomarkers for cobalt or zinc metabolism in Prochlorococcus, with studies producing negative results (Hawco et al., 2020). For Synechococcus, there were no clear trends in ferredoxin (Fig. 4c) and flavodoxin was infrequently detected. These findings highlight the challenge when predicting the direct metal requirement alongside metals controlling multiple APs in-situ, and makes a strong case for continued biochemical characterization of cyanobacterial trace metal physiology and enzymes.

3.5 Influence of nitrogen acquisition on the biogeography of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus in the subtropical North Atlantic

The spatial patterns in nitrogen stress biomarkers gleaned from non-targeted metaproteomics provided insight into how fixed nitrogen availability contributed to shaping the biogeography of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus across the subtropical Atlantic. Surface ocean gradients in fixed nitrogen are established via a combination of upwelling in the eastern Atlantic (Menna et al., 2016), nitrogen fixation (Fig. 3g, Cerdan-Garcia et al., 2022) and dust deposition (Powell et al., 2015) delivering nitrate, ammonium and urea to the surface subtropical Atlantic Ocean alongside microbial demand consuming fixed nitrogen. In summer 2017, concentrations of nitrate (< 40 nM) and ammonium (< 20 nM) were relatively low across the transect (Fig. 1e and f). The lowest spectral counts of the N-stress proteins, AmtB and UrtA in Prochlorococcus (Fig. 4c) coincided with a region of elevated nitrogen fixation rates (Fig 3g), reflecting alleviation of N stress in Prochlorococcus. The combination of efficient uptake of nitrogen derived from nitrogen fixers (Caffin et al., 2018), alongside the small cell size of Prochlorococcus provides a strong competitive advantage under oligotrophic conditions, as observed in the North Pacific gyre (Saito et al., 2014, 2015). Otherwise, Prochlorococcus was subjected to increasing N stress towards the eastern Atlantic, evidenced by eastward increases in protein biomarkers in Prochlorococcus, specifically P-II, ammonium transporter AmtB and urea transporter UrtA (30 %–70 %, Fig. 4b and Table 2).

In contrast to Prochlorococcus, consistently elevated UrtA in Synechococcus suggests chronic N stress throughout the transect, with UrtA in Synechococcus being more than 5 times higher than for Prochlorococcus (Fig. 4b). This is consistent with the physiological disadvantage of Synechococcus, with its larger cell size and less efficient surface-area to volume ratio for nutrient acquisition (Chisholm et al., 1992). P-II and AmtB (or NtcA) was not detected in the metaproteome of Synechococcus, perhaps because Synechococcus was 5 to 10 times less abundant in the metaproteomes compared to Prochlorococcus. The dominance of proteins for ammonium and urea acquisition of Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus are consistent with the premise that while marine Synechococcus and some Prochlorococcus strains have the genetic makeup to assimilate nitrate (Berube et al., 2015; Domínguez-Martín et al., 2022; Martiny et al., 2009, it accounts for < 5 % of their total N demand, and instead ammonium and urea are the dominant N sources (Berthelot et al., 2019; Casey et al., 2016; Painter et al., 2008). The patterns observed align with established biogeographical trends in which Prochlorococcus dominates in the nutrient-deplete surface ocean due to its competitive advantage as a small cell, whereas Synechococcus persists in regions where fixed N is available. The proteomic data indicate that nitrogen acquisition traits are one of the key determinants of population dynamics, driving spatial partitioning between Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus and ultimately influencing primary productivity and nutrient cycling across the subtropical Atlantic.

This study exploited natural gradients in nutrient resources created by upwelling in the east and dust deposition in the west. Combining biogeochemical states, enzyme rate measurements, and “omics” approaches, in the spirit of the developing “BioGeoSCAPES” program (Saito et al., 2024), we studied the nutrient acquisition strategies for Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus in-situ and using nutrient bioassays. Using protein biomarkers alongside biogeochemical signatures for nutrient stress, we concluded that Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus were P-stressed in the western Atlantic and Prochlorococcus was N-stressed in the eastern Atlantic, with Synechococcus showing signs of N-stress throughout the transect. Our findings are generally consistent with prior metagenomic observations on basin scale contrasts in N and P stress for Prochlorococcus in the Atlantic Ocean (at medium level, Ustick et al., 2021). There was evidence for trace metal control on alkaline phosphatase but the response of protein biomarkers to the addition of organic P, Zn and Fe differed between Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus (also see Held et al., 2026, companion manuscript), highlighting that the functions and systems biology of alkaline phosphatase regulation differs across the organisms and for different environmental stimuli. This indicates that ongoing laboratory characterization of protein biomarkers and cyanobacterial physiology is needed to define the regulation and function not only at the species level, but also across strains within species.

Under future climate scenarios, stratification, aerosol dynamics, N2 fixation and the bioavailability of organic P are predicted to change (e.g. Buchanan et al., 2021; Chien et al., 2016; White et al., 2012; Wrightson and Tagliabue, 2020), all with the potential to perturb the availability of already scarce nutrient resources in the oligotrophic gyres. To identify and quantify the future trajectory of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus under future ocean scenarios, a holistic view that considers the species and strain specific strategies used to access resources, alongside representation of large scale forcings are required. We have shown here that there is utility in combining biogeochemical assays with untargeted and targeted omics approaches to reveal these patterns, generate hypotheses that can be tested in controlled laboratory experiments, and improve predictions of marine microbiology and biogeochemistry in a changing ocean.

All new data are provided in the Supplement or are available from the British Oceanographic Data Centre (BODC) with the following DOIs: Size-fractionated iron measurements (Berube et al., 2015; Domínguez-Martín et al., 2022; Martiny et al., 2009), inorganic nutrients, alkaline phosphatase, DOP, chlorophyll, flow cytometry: https://doi.org/10.5285/284a411e-2639-93de-e063-7086abc0e9d8 (Mahaffey et al., 2024a), Experiment D (https://doi.org/10.5285/1e9c4caa-b936-fc7c-e063-7086abc06ff6, Mahaffey et al., 2024b). The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD054252 and https://doi.org/10.6019/PXD054252 (Held and Saito, 2025).

Supplementary information is provided as individual files and 1 zip file. There are 4 Supplements including Supplement S1 (Fasta file), Supplement S2 (protein file), Supplement S3 (peptide file) and Supplement S4 (trace metal clean protocols for nutrient bioassays). In the zip file, there are 5 tables provided as spreadsheets (Table S1 to S5) and 5 figures (Fig. S1 to S5). The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-23-905-2026-supplement.

CM, MCL and AT acquired the funding from NERC. CM and MCL led the research cruise. CD conducted AP measurements. KK conducted Fe measurements. NW conducted zinc measurements. EMSW conducted nutrient measurements. LW conducted N2 fixation measurements. CM, MCL, CD, KK, LW and NW conducted the large volume incubation experiments. KK and NH conducted the quantitative proteomics analysis and MM analysed samples using mass spectrometry at WHOI. NH and MM conducted the global metaproteome analyses. CM and NH wrote the manuscript with significant contributions from MS, ML, CD, KK and AT.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors would like to thank the officers and crew of the RRS James Cook for the successful research cruise, JC150. This research was supported by the Natural Environment Research Council (NE/N001079/1, awarded to CM and AT, NE/N001125/1 awarded to ML), Simons Foundation Grants 1038971 and BioSCOPE, Chemical Currencies of a Microbial Planet (CCOMP) NSF-STC 2019589 to M.A.S, an ETH Zurich Career Seed Grant to N.A.H, and the USCDornsife College of Arts and Sciences. K.K. was supported by Graduate School of the National Oceanography Centre Southampton (UK) the Simons Foundation (award 723552) during the writing process. The authors would also like to thank Alastair Lough and Clément Demasy for the dissolved cobalt measurements.

This paper was edited by Tina Šantl-Temkiv and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Barkley, A. E., Prospero, J. M., Mahowald, N., Hamilton, D. S., Popendorf, K. J., Oehlert, A. M., Pourmand, A., Gatineau, A., Panechou-Pulcherie, K., Blackwelder, P., and Gaston, C. J.: African biomass burning is a substantial source of phosphorus deposition to the Amazon, Tropical Atlantic Ocean, and Southern Ocean, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 116, 16216–16221, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1906091116, 2019.

Becker, S., Aoyama, M., Woodward, E. M. S., Bakker, K., Coverly, S., Mahaffey, C., and Tanhua, T.: GO-SHIP Repeat Hydrography Nutrient Manual: The Precise and Accurate Determination of Dissolved Inorganic Nutrients in Seawater, Using Continuous Flow Analysis Methods, Front. Mar. Sci., 7, 581790, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.581790, 2020.

Berthelot, H., Duhamel, S., L'Helguen, S., Maguer, J.-F., Wang, S., Cetinić, I., and Cassar, N.: NanoSIMS single cell analyses reveal the contrasting nitrogen sources for small phytoplankton, ISME J., 13, 651–662, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0285-8, 2019.

Berube, P. M., Biller, S. J., Kent, A. G., Berta-Thompson, J. W., Roggensack, S. E., Roache-Johnson, K. H., Ackerman, M., Moore, L. R., Meisel, J. D., Sher, D., Thompson, L. R., Campbell, L., Martiny, A. C., and Chisholm, S. W.: Physiology and evolution of nitrate acquisition in Prochlorococcus, ISME J., 9, 1195–1207, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.211, 2015.

Bopp, L., Resplandy, L., Orr, J. C., Doney, S. C., Dunne, J. P., Gehlen, M., Halloran, P., Heinze, C., Ilyina, T., Séférian, R., Tjiputra, J., and Vichi, M.: Multiple stressors of ocean ecosystems in the 21st century: projections with CMIP5 models, Biogeosciences, 10, 6225–6245, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-6225-2013, 2013.

Brewer, P. G. and Riley, J. P.: The automatic determination of nitrate in sea water, Deep Sea Res. Oceanogr. Abstr., 12, 765–772, https://doi.org/10.1016/0011-7471(65)90797-7, 1965.

Browning, T. J. and Moore, C. M.: Global analysis of ocean phytoplankton nutrient limitation reveals high prevalence of co-limitation, Nat. Commun., 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40774-0, 2023.

Browning, T. J., Achterberg, E. P., Yong, J. C., Rapp, I., Utermann, C., Engel, A., and Moore, C. M.: Iron limitation of microbial phosphorus acquisition in the tropical North Atlantic, Nat. Commun., 8, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15465, 2017.

Buchanan, P. J., Aumont, O., Bopp, L., Mahaffey, C., and Tagliabue, A.: Impact of intensifying nitrogen limitation on ocean net primary production is fingerprinted by nitrogen isotopes, Nat. Commun., 12, 6214, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26552-w, 2021.

Caffin, M., Berthelot, H., Cornet-Barthaux, V., Barani, A., and Bonnet, S.: Transfer of diazotroph-derived nitrogen to the planktonic food web across gradients of N2 fixation activity and diversity in the western tropical South Pacific Ocean, Biogeosciences, 15, 3795–3810, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-3795-2018, 2018.

Casey, J. R., Mardinoglu, A., Nielsen, J., and Karl, D. M.: Adaptive Evolution of Phosphorus Metabolism in Prochlorococcus, mSystems, 1, e00065-16, https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00065-16, 2016.

Cerdan-Garcia, E., Baylay, A., Polyviou, D., Woodward, E. M. S., Wrightson, L., Mahaffey, C., Lohan, M. C., Moore, C. M., Bibby, T. S., and Robidart, J. C.: Transcriptional responses of Trichodesmium to natural inverse gradients of Fe and P availability, ISME J., 16, 1055–1064, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-021-01151-1, 2022.

Chappell, P. D., Moffett, J. W., Hynes, A. M., and Webb, E. A.: Molecular evidence of iron limitation and availability in the global diazotroph Trichodesmium, ISME J., 6, 1728–1739, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2012.13, 2012.

Chien, C., Mackey, K. R. M., Dutkiewicz, S., Mahowald, N. M., Prospero, J. M., and Paytan, A.: Effects of African dust deposition on phytoplankton in the western tropical Atlantic Ocean off Barbados, Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles, 30, 716–734, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015gb005334, 2016.

Chisholm, S. W., Frankel, S. L., Goericke, R., Olson, R., Palenik, B., Waterbury, J. B., West-Johnsrud, L., and Zettler, E. R.: Prochlorococcus marinus nov. gen. nov. sp.: an oxyphototrophic marine prokaryote containing divinyl chlorophyll a and b, Microbiol., 157, 297–300, 1992.

Coleman, J. E.: Structure and Mechanism of Alkaline Phosphatase, Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct., 21, 441–483, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.002301, 1992.

Coutinho, F., Tschoeke, D. A., Thompson, F., and Thompson, C.: Comparative genomics of Synechococcus and proposal of the new genus Parasynechococcus, PeerJ, 4, e1522, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1522, 2016.

Cox, A. D. and Saito, M. A.: Proteomic responses of oceanic Synechococcus WH8102 to phosphate and zinc scarcity and cadmium additions, Front. Microbiol., 4, 387, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2013.00387, 2013.

Davis, C. E., Blackbird, S., Wolff, G., Woodward, M., and Mahaffey, C.: Seasonal organic matter dynamics in a temperate shelf sea, Prog. Oceanogr., 177, 101925, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2018.02.021, 2019.

Domínguez-Martín, M. A., López-Lozano, A., Melero-Rubio, Y., Gómez-Baena, G., Jiménez-Estrada, J. A., Kukil, K., Diez, J., and García-Fernández, J. M.: Marine Synechococcus sp. Strain WH7803 Shows Specific Adaptative Responses to Assimilate Nanomolar Concentrations of Nitrate, Microbiol. Spectr., 10, https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.00187-22, 2022.

Duhamel, S., Björkman, K. M., Van Wambeke, F., Moutin, T., and Karl, D. M.: Characterization of alkaline phosphatase activity in the North and South Pacific Subtropical Gyres: Implications for phosphorus cycling, Limnol. Oceanogr., 56, 1244–1254, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2011.56.4.1244, 2011.

Duhamel, S., Diaz, J. M., Adams, J. C., Djaoudi, K., Steck, V., and Waggoner, E. M.: Phosphorus as an integral component of global marine biogeochemistry, Nat. Geosci., 14, 359–368, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00755-8, 2021.

Edmonds, K. A., Jordan, M. R., and Giedroc, D. P.: COG0523 proteins: a functionally diverse family of transition metal-regulated G3E P-loop GTP hydrolases from bacteria to man, Metallomics, 13, https://doi.org/10.1093/mtomcs/mfab046, 2021.

Grant, S. R., Church, M. J., Ferrón, S., Laws, E. A., and Rappé, M. S.: Elemental Composition, Phosphorous Uptake, and Characteristics of Growth of a SAR11 Strain in Batch and Continuous Culture, mSystems, 4, https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00218-18, 2019.

Gross, A., Goren, T., Pio, C., Cardoso, J., Tirosh, O., Todd, M. C., Rosenfeld, D., Weiner, T., Custódio, D., and Angert, A.: Variability in Sources and Concentrations of Saharan Dust Phosphorus over the Atlantic Ocean, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 2, 31–37, https://doi.org/10.1021/ez500399z, 2015.

Hawco, N. J. and Saito, M. A.: Competitive inhibition of cobalt uptake by zinc and manganese in a pacificProchlorococcus strain: Insights into metal homeostasis in a streamlined oligotrophic cyanobacterium, Limnol. Oceanogr., 63, 2229–2249, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10935, 2018.

Hawco, N. J., McIlvin, M. M., Bundy, R. M., Tagliabue, A., Goepfert, T. J., Moran, D. M., Valentin-Alvarado, L., DiTullio, G. R., and Saito, M. A.: Minimal cobalt metabolism in the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 117, 15740–15747, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2001393117, 2020.

Held, N. A. and Saito, M. A.: Proteomics LC-MS data (Divergence in resource acquisition strategies and drivers of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus abundance in the subtropical North Atlantic Ocean), PRIDE [data set], https://doi.org/10.6019/PXD054252, 2025.

Held, N. A., Webb, E. A., McIlvin, M. M., Hutchins, D. A., Cohen, N. R., Moran, D. M., Kunde, K., Lohan, M. C., Mahaffey, C., Woodward, E. M. S., and Saito, M. A.: Co-occurrence of Fe and P stress in natural populations of the marine diazotroph Trichodesmium, Biogeosciences, 17, 2537–2551, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-2537-2020, 2020.

Held, N. A., Kunde, K., Davis, C. E., Wyatt, N. J., Mann, E. L., Woodward, E. M. S., McIlvin, M., Tagliabue, A., Twining, B. S., Mahaffey, C., Saito, M. A., and Lohan, M. C.: Proteomic and biogeochemical perspectives on cyanobacteria nutrient acquisition – Part 2: quantitative contributions of cyanobacterial alkaline phosphatases to bulk enzymatic rates in the subtropical North Atlantic, Biogeosciences, 23, 923–938, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-23-923-2026, 2026.

Hoppe, H. G.: Phosphatase activity in the sea, Hydrobiologia, 493, 187–200, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025453918247, 2003.

Ilikchyan, I. N., McKay, R. M. L., Kutovaya, O. A., Condon, R., and Bullerjahn, G. S.: Seasonal Expression of the Picocyanobacterial Phosphonate Transporter Gene phnD in the Sargasso Sea, Front. Microbiol., 1, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2010.00135, 2010.

Jakuba, R. W., Moffett, J. W., and Dyhrman, S. T.: Evidence for the linked biogeochemical cycling of zinc, cobalt, and phosphorus in the western North Atlantic Ocean, Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles, 22, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007gb003119, 2008.

Jickells, T. D.: The inputs of dust derived elements to the Sargasso Sea; a synthesis, Mar. Chem., 68, 5–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4203(99)00061-4, 1999.

Johnson, Z. I., Zinser, E. R., Coe, A., McNulty, N. P., Woodward, E. M. S., and Chisholm, S. W.: Niche Partitioning Among Prochlorococcus Ecotypes Along Ocean-Scale Environmental Gradients, Science, 311, 1737–1740, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1118052, 2006.

Jones, R. D.: An improved fluorescence method for the determination of nanomolar concentrations of ammonium in natural waters, Limnol. Oceanogr., 36, 814–819, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1991.36.4.0814, 1991.

Kathuria, S. and Martiny, A. C.: Prevalence of a calcium-based alkaline phosphatase associated with the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus and other ocean bacteria, Environ. Microbiol., 13, 74–83, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02310.x, 2011.

Kim, I.-N., Lee, K., Gruber, N., Karl, D. M., Bullister, J. L., Yang, S., and Kim, T.-W.: Increasing anthropogenic nitrogen in the North Pacific Ocean, Science, 346, 1102–1106, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1258396, 2014.

Kunde, K., Wyatt, N. J., and Lohan, M.: Size-fractionated iron measurements from surface sampling and depth profiles along 22N in the North Atlantic during summer 2017 on cruise JC150, British Oceanographic Data Centre, National Oceanography Centre, NERC, UK [data set], https://doi.org/10.5285/8a1800cc-b6a6-30ea-e053-6c86abc0c934, 2019.

Kunde, K., Wyatt, N. J., González-Santana, D., Tagliabue, A., Mahaffey, C., and Lohan, M. C.: Iron Distribution in the Subtropical North Atlantic: The Pivotal Role of Colloidal Iron, Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles, 33, 1532–1547, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GB006326, 2019.

Lapointe, B. E., Brewton, R. A., Herren, L. W., Wang, M., Hu, C., McGillicuddy, D. J., Lindell, S., Hernandez, F. J., and Morton, P. L.: Nutrient content and stoichiometry of pelagic Sargassum reflects increasing nitrogen availability in the Atlantic Basin, Nat. Commun., 12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23135-7, 2021.

Liang, Z., Letscher, R. T., and Knapp, A. N.: Dissolved organic phosphorus concentrations in the surface ocean controlled by both phosphate and iron stress, Nat. Geosci., 15, 651–657, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-022-00988-1, 2022.

Liu, M., Matsui, H., Hamilton, D. S., Lamb, K. D., Rathod, S. D., Schwarz, J. P., and Mahowald, N. M.: The underappreciated role of anthropogenic sources in atmospheric soluble iron flux to the Southern Ocean, Npj Clim. Atmospheric Sci., 5, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-022-00250-w, 2022.

Lomas, M. W., Burke, A. L., Lomas, D. A., Bell, D. W., Shen, C., Dyhrman, S. T., and Ammerman, J. W.: Sargasso Sea phosphorus biogeochemistry: an important role for dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP), Biogeosciences, 7, 695–710, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-7-695-2010, 2010.

Lomas, M. W., Bonachela, J. A., Levin, S. A., and Martiny, A. C.: Impact of ocean phytoplankton diversity on phosphate uptake, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 111, 17540–17545, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1420760111, 2014.

Lough, A. J. M., Homoky, W. B., Connelly, D. P., Comer-Warner, S. A., Nakamura, K., Abyaneh, M. K., Kaulich, B., and Mills, R. A.: Soluble iron conservation and colloidal iron dynamics in a hydrothermal plume, Chem. Geol., 511, 225–237, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2019.01.001, 2019.

Lu, X. and Zhu, H.: Tube-Gel Digestion, Mol. Cell. Proteomics, 4, 1948–1958, https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.m500138-mcp200, 2005.

Luo, H., Benner, R., Long, R. A., and Hu, J.: Subcellular localization of marine bacterial alkaline phosphatases, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 106, 21219–21223, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0907586106, 2009.

Mahaffey, C., Lohan, M., Woodward, M. S., Davis, C., Wyatt, N. J., Kunde, K., Wrightson, L., González-Santana, D., Shelley, P. D., and Johnson, L.: Temperature, salinity, alkaline phosphatase activity, phytoplankton abundance, chlorophyll a, inorganic nutrients, dissolved organic phosphorus, and dissolved zinc concentrations from towed fish surface samples in the subtropical North Atlantic during summer 2017 on cruise GApr08/JC150, NERC EDS British Oceanographic Data Centre NOC [data set], https://doi.org/10.5285/284a411e-2639-93de-e063-7086abc0e9d8, 2024a.

Mahaffey, C., Lohan, M., Woodward, E. M. S., Davis, C., Wyatt, N. J., Kunde, K., Wrightson, L., González-Santana, D., Shelley, P. D., and Johnson, L.: Chlorophyll a and nutrient concentrations, Alkaline Phosphatase Activity, phytoplankton abundance, and nitrogen fixation rates from cruise JC150 incubation experiment D, July–August 2017, NERC EDS British Oceanographic Data Centre NOC [data set], https://doi.org/10.5285/1e9c4caa-b936-fc7c-e063-7086abc06ff6, 2024b.

Mahaffey, C., Reynolds, S., Davis, C. E., and Lohan, M. C.: Alkaline phosphatase activity in the subtropical ocean: insights from nutrient, dust and trace metal addition experiments, Front. Mar. Sci., 1, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2014.00073, 2014.

Martínez, A., Osburne, M. S., Sharma, A. K., DeLong, E. F., and Chisholm, S. W.: Phosphite utilization by the marine picocyanobacterium Prochlorococcus MIT9301, Environ. Microbiol., 14, 1363–1377, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02612.x, 2012.

Martiny, A. C., Coleman, M. L., and Chisholm, S. W.: Phosphate acquisition genes in Prochlorococcus ecotypes: Evidence for genome-wide adaptation, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 103, 12552–12557, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0601301103, 2006.

Martiny, A. C., Kathuria, S., and Berube, P. M.: Widespread metabolic potential for nitrite and nitrate assimilation among Prochlorococcus ecotypes, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 106, 10787–10792, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0902532106, 2009.

McIlvin, M. R. and Saito, M. A.: Online Nanoflow Two-Dimension Comprehensive Active Modulation Reversed Phase–Reversed Phase Liquid Chromatography High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry for Metaproteomics of Environmental and Microbiome Samples, J. Proteome Res., 20, 4589–4597, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.1c00588, 2021.

Menna, M.: Upwelling Features off the Coast of North-Western Africa in 2009–2013, BGTA, https://doi.org/10.4430/bgta0164, 2015.

Menna, M., Faye, S., Poulain, P.-M., Centurioni, L., Lazar, A., Gaye, A., Sow, B., and Dagorne, D.: Upwelling features off the coast of north-western Africa in 2009–2013, BGTA, 57, 71086, https://doi.org/10.4430/bgta0164, 2016.

Mikhaylina, A., Ksibe, A. Z., Wilkinson, R. C., Smith, D., Marks, E., Coverdale, J. P. C., Fülöp, V., Scanlan, D. J., and Blindauer, C. A.: A single sensor controls large variations in zinc quotas in a marine cyanobacterium, Nat. Chem. Biol., 18, 869–877, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-022-01051-1, 2022.

Mills, M. M., Ridame, C., Davey, M., La Roche, J., and Geider, R. J.: Iron and phosphorus co-limit nitrogen fixation in the eastern tropical North Atlantic, Nature, 429, 292–294, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02550, 2004.

Moore, C. M., Mills, M. M., Langlois, R., Milne, A., Achterberg, E. P., La Roche, J., and Geider, R. J.: Relative influence of nitrogen and phosphorous availability on phytoplankton physiology and productivity in the oligotrophic sub-tropical North Atlantic Ocean, Limnol. Oceanogr., 53, 291–305, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2008.53.1.0291, 2008.

Moore, C. M., Mills, M. M., Achterberg, E. P., Geider, R. J., LaRoche, J., Lucas, M. I., McDonagh, E. L., Pan, X., Poulton, A. J., Rijkenberg, M. J. A., Suggett, D. J., Ussher, S. J., and Woodward, E. M. S.: Large-scale distribution of Atlantic nitrogen fixation controlled by iron availability, Nat. Geosci., 2, 867–871, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo667, 2009.

Moore, L., Ostrowski, M., Scanlan, D., Feren, K., and Sweetsir, T.: Ecotypic variation in phosphorus-acquisition mechanisms within marine picocyanobacteria, Aquat. Microb. Ecol., 39, 257–269, https://doi.org/10.3354/ame039257, 2005.

Nowicki, J. L., Johnson, K. S., Coale, K. H., Elrod, V. A., and Lieberman, S. H.: Determination of Zinc in Seawater Using Flow Injection Analysis with Fluorometric Detection, Anal. Chem., 66, 2732–2738, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac00089a021, 1994.

Ostrowski, M., Mazard, S., Tetu, S. G., Phillippy, K., Johnson, A., Palenik, B., Paulsen, I. T., and Scanlan, D. J.: PtrA is required for coordinate regulation of gene expression during phosphate stress in a marine Synechococcus, ISME J., 4, 908–921, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2010.24, 2010.

Painter, S., Sanders, R., Waldron, H., Lucas, M., and Torres-Valdes, S.: Urea distribution and uptake in the Atlantic Ocean between 50° N and 50° S, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 368, 53–63, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps07586, 2008.