the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Factors controlling Carex brevicuspis leaf litter decomposition and its contribution to surface soil organic carbon pool at different water levels

Lianlian Zhu

Zhengmiao Deng

Yonghong Xie

Xu Li

Feng Li

Xinsheng Chen

Yeai Zou

Chengyi Zhang

Litter decomposition plays a vital role in wetland carbon cycling. However, the contribution of aboveground litter decomposition to the wetland soil organic carbon (SOC) pool has not yet been quantified. Here, we conducted a Carex brevicuspis leaf litter input experiment to clarify the intrinsic factors controlling litter decomposition and quantify its contribution to the SOC pool at different water levels. The Carex genus is ubiquitous in global freshwater wetlands. We sampled this plant leaf litter at −25, 0, and +25 cm relative to the soil surface over 280 d and analysed leaf litter decomposition and its contribution to the SOC pool. The percentage litter dry weight loss and the instantaneous litter dry weight decomposition rate were the highest at +25 cm water level (61.8 %, 0.01307 d−1), followed by the 0 cm water level (49.8 %, 0.00908 d−1), and the lowest at −25 cm water level (32.4 %, 0.00527 d−1). Significant amounts of litter carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus were released at all three water levels. Litter input significantly increased the soil microbial biomass and fungal density but had nonsignificant impacts on soil bacteria, actinomycetes, and the fungal∕bacterial concentrations at all three water levels. Compared with litter removal, litter addition increased the SOC by 16.93 %, 9.44 %, and 2.51 % at the +25, 0, and −25 cm water levels, respectively. Hence, higher water levels facilitate the release of organic carbon from leaf litter into the soil via water leaching. In this way, they increase the soil carbon pool. At lower water levels, soil carbon is lost due to the slower litter decomposition rate and active microbial (actinomycete) respiration. Our results revealed that the water level in natural wetlands influenced litter decomposition mainly by leaching and microbial activity, by extension, and affected the wetland surface carbon pool.

- Article

(6144 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Wetlands are important terrestrial carbon pools. Depending on the definition of “wetland”, they contain between 82 and 158 Pg soil organic carbon (SOC) (Kayranli et al., 2010; Kochy et al., 2015). The surface soil organic carbon (SOC) pool (S-SOCP) and its turnover are sensitive to climate, topography, and hydrological conditions (Wang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017; Pinto et al., 2018).

Leaf litter decomposition is a major biotic carbon input route from vegetation to S-SOCP in wetland ecosystems (Whiting and Chanton, 2001; Moriyama et al., 2013). However, the reported impacts of litter decomposition on the soil carbon pool are highly variable (Bowden et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2020). Litter input destabilised carbon storage by stimulating soil mineralisation and increasing labile soil carbon fractions (microbial biomass carbon (MBC), soil dissolved organic carbon (DOC)), and enzyme activity in the freshwater marshland of northeastern China (Song et al., 2014). It also promoted soil carbon loss via CO2 emissions and microbial activity in alpine and coastal wetlands (Gao et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017). In contrast, a study has recently found that litter decomposition stabilised the soil carbon pool after processing by soil microbes in the Jiaozhou Bay wetland (Sun et al., 2019).

Litter decomposition is a physicochemical process that reduces litter to its elemental chemical constituents (Xie et al., 2017). Litter decomposition rates are determined mainly by environmental factors (climatic and soil conditions), litter quality (litter composition such as C, N, and lignin content) and decomposer organisms (microorganisms and invertebrates) (Yan et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2020). A previous study showed that regional and global environmental conditions explain >51 % of the variation in litter decomposition rate (Zhang et al., 2019). In wetland ecosystems, the water level ecosystem processes determine soil aerobic and anaerobic conditions which, in turn, affect the microbial decomposition of litter and SOC decomposition (Liu et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2018). An earlier study reported that high soil moisture content and long flooding periods facilitate litter decomposition by promoting leaching, fragmentation, and microbial activity (Van de Moortel et al., 2012). The water level may contribute to soil physicochemical conditions which, in turn, regulate litter decomposition (Xie et al., 2016b). Leaf litter contributes more to soil organic carbon than fine roots (Cao et al., 2020); litter also strongly influences root decomposition rates, particularly near the surface (Hoyos-Santillan et al., 2015). However, the contribution of litter decomposition to the S-SOCP pool has seldom been quantified.

Peng et al. (2005) reported that the organic carbon density in Dongting Lake wetland soil at 1 m depth was 127.3 ± 36.1 t hm−2, and the carbon density in the 0–30 cm topsoil was 46.5 ± 19.7 t hm−2. Carex brevicuspis is a dominant species in the Dongting Lake wetland and has large carbon reserves (∼ 6.5 × 106 t yr−1) (Kang et al., 2009). However, due to the dam construction upstream of Dongting Lake, the water regime has varied considerably (early water withdrawal and decline of groundwater in non-flood season) in recent years, leading to a significant carbon loss in this floodplain wetland (Hu et al., 2018; Deng et al., 2018).

Here, we investigated C. brevicuspis leaf litter decomposition and its contribution to the SOC pool at three water levels (−25, 0, and +25 cm relative to the soil surface) to find the factors controlling C. brevicuspis leaf litter decomposition and quantify the contribution of litter decomposition to the SOC pool. We tested the following hypotheses. Firstly, the water level has a significant effect on litter decomposition. Secondly, the intrinsic factors that control litter decomposition rate at three water levels are different. Thirdly, the contribution of leaf decomposition to S-SOCP is relatively higher at the +25 cm water level.

2.1 Soil core collection and leaf litter preparation

Dongting Lake (28∘30′–30∘20′ N, 111∘40′–113∘10′ E) is the second-largest freshwater lake in China. It is connected to the Yangtze River via tributaries. Dongting Lake wetlands are characterised by large seasonal fluctuations in water level (≤ 15 m) and are completely flooded during June–October and exposed during November–May (Chen et al., 2016). Soil cores (40 cm diameter × 50 cm length) were taken from the wetland. Leaf litter was collected in May 2017 from an undisturbed Carex brevicuspis community at the sampling site (29∘27′2.02′′ N, 112∘47′32.28′′ E) of the Dongting Lake Station for Wetland Ecosystem Research, which is part of the China Ecosystem Research Network. The litter was cleaned with distilled water, oven-dried at 60 ∘C to a constant weight, and cut into pieces 5–10 cm long. Pre-weighed litter samples (5 g; 10.73 ± 0.28 g kg−1 N, 0.89 ± 0.04 g kg−1 P, 40.23 ± 2.6 % organic C, and 17.83 ± 0.25 % lignin) were placed into 10 cm × 15 cm 1 mm mesh nylon bags. This mesh size excluded macroinvertebrates but permitted microbial colonisation and litter fragment leaching (Xie et al., 2016a).

2.2 Experimental design

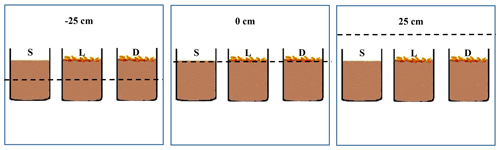

There were three water level treatments (−25, 0, and +25 cm relative to the soil surface) nested by two litter treatments (input vs. removal) and three replicates. The experiment was conducted in nine cement ponds (2 m × 2 m × 1 m) at the Dongting Lake Station for Wetland Ecosystem Research. For the −25 cm treatment, the water level was 25 cm below the soil surface. For the 0 cm treatment, the soil was fully wetted with belowground water (the belowground water was extracted from the well in the experiment site by a water pump) but without surface pooling. For the +25 cm treatment, the water level was 25 cm above the soil surface. Water levels were adjusted weekly using belowground water (total organic carbon: 3.44 mg L−1; total nitrogen: 0.001 mg L−1; total phosphorus: 0.018 mg L−1). Three soil core sets were placed in each pond. One was designated the litter removal control (S), the second was distributed on the soil surface with 15 litter bags to observe the effects of leaf litter input on soil carbon pool (L), and the third was distributed on the soil surface with 15 litter bags to monitor the litter decomposition rate and process (D) (Fig. 1). Litter bags were laid flat on the surface of the soil. Each litter bag was not filled, and there are a little overlap between the litter bags where there is no litter. All the litter bags were fixed to the soil surface with bamboo sticks. The experiment started on 20 August 2017 and lasted 280 d. By that time, no further significant change in litter dry weight was observed. Before incubation, three litter and three soil samples (SOC: 63.32 g kg−1) were collected to determine their initial quality. Litter bags were randomly collected from treatment D after 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 130, 160, 190, 220, 250, and 280 d. After collection, the litter samples were separated, cleaned with distilled water, and oven-dried at 60 ∘C to a constant weight (±0.01 g). All samples were pulverised and passed through a 0.5 mm mesh screen for litter quality analysis. At the end of incubation, the surface soil (0–5 cm, ∼ 600 g in fresh weight) was collected to eliminate the influences of root decomposition on the soil organic pool. The soil samples were placed in aseptic sealed plastic bags and transported to the laboratory. The samples were sieved (<2 mm), thoroughly mixed, and divided into three subsamples. The first subsample (∼ 150 g) was stored at −20 ∘C and freeze-dried for phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis. The second one (∼ 150 g) was stored at 4 ∘C for MBC and DOC measurements. The third subsample (∼ 300 g) was air-dried for physicochemical analysis.

Figure 1Schematic diagram of the experimental setup. The dotted line represents the water level. L represents litter which was distributed on the soil surface in 15 litter bags to observe the effects of leaf litter input on soil carbon pool; S represents soil which was designated the litter removal control; D represents decomposition which was distributed on the soil surface in 15 litter bags to monitor the litter decomposition rate and process.

2.3 Litter quality analyses

Litter organic carbon content was analysed by the H2SO4-K2Cr2O7 heat method. Litter nitrogen was extracted by Kjeldahl digestion and quantified with a flow injection analyser AA3 (SEAL, Germany) (Xie et al., 2017). Litter phosphorus content was quantified by the molybdenum–antimony anti-spectrophotometric method. The lignin content was measured by hydrolysis (72 % H2SO4) (Graça et al., 2005; Xie et al., 2017).

2.4 Soil quality analyses

2.4.1 Soil chemical analyses

SOC was determined by wet oxidation with KCr2O7 + H2SO4 and titration with FeSO4 (Xie et al., 2017). Soil DOC was extracted with K2SO4 and measured with a TOC analyser (TOC-VWP; Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan). MBC was analysed by chloroform fumigation and K2SO4 extraction, and it was measured with a TOC analyser (TOC-VWP, Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) (Tong et al., 2017).

2.4.2 Soil microbial composition

The total and specific microbial group biomass values and the microbial community structure were estimated by PLFA analysis. The PLFAs were extracted from 8 g of freeze-dried soil and analysed as previously described (Zhao et al., 2015). The concentrations of each PLFA were calculated relative to that of the methyl nonadecanoate (19:0) internal standard. The PLFAs for the following groups were determined: bacterial biomass, sum of i15:0, a15:0, 15:0, i16:0, 16 : 1u7, i17:0, a17:0, 17:0, cy17:0, and cy19:0; actinomycete biomass, sum of 10 Me 16:0, 10 Me17:0, and 10 Me 18:0; and fungal biomass, 18:2 ω6 and 18:1ω9. The total microbial biomass was represented by the sum of the bacterial, fungal, and actinomycete biomass values. The ratios of fungal to bacterial lipids (F/B) were used to evaluate the microbial community structure (Bossio and Scow, 1998; Wilkinson et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2015). We calculated PLFA mass content first, PLFA (ng g−1 dry soil) = (response of PLFA/response of 19:0 internal standard) × concentration of 19:0 internal standard × (volume of sample ∕ mass of soil). Concentration of 19:0 is an internal standard: 5 µg mL−1, volume of sample: 200µL mass of soil: 8 g dry soil. And then we calculated PLFA molar mass concentration, PLFA (n mol g−1 dry soil) = PLFA (ng g−1 dry soil) ∕ relative molecular mass.

2.5 Data processing

2.5.1 Litter decomposition rate

The percentage of litter dry weight loss was calculated as follows (Zhang et al., 2019):

where Lt is the percentage litter dry weight loss at time t (%), Mt is the litter dry matter weight at the time t (g), and M0 is the initial dry matter weight (g).

The instantaneous litter dry mass decay rate (k) was calculated based on the Olson negative exponential attenuation model and double exponential decay model (Olson, 1963; Berg, 2014):

where is the litter dry matter weight at nth sampling (g), is the litter dry matter weight at (n−1)th sampling (g), is the time between the nth and (n−1)th sampling, and kn is the instantaneous decomposition rate at the nth sampling.

2.5.2 Relative release index

The relative release indices (RRIs) of C, N, and P from the plant litter were calculated as follows (Zhang et al., 2019):

where Ct is the concentration of an element in the litter at time t, C0 is the initial concentration of an element in the litter, and Mt is the litter dry matter weight at time t (g). CRRI, NRRI, PRRI, and LRRI represent the carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and lignin RRIs, respectively. A positive RRI indicates a net release of the element during litter decomposition whilst a negative RRI indicates a net accumulation of the element during litter decomposition.

2.5.3 Contribution of litter-C input to the SOC pool

The contribution of litter-C input to the SOC pool was calculated as follows (Lv and Wang, 2017):

where LC is the contribution of the litter-C input to SOC pool, SOCL is the SOC concentration for the litter input treatment, SOCS is the SOC concentration for the treatment without litter input, and SOCi is the initial SOC content before the experimental treatments.

2.6 Statistical analyses

The percentage of litter dry weight losses and the instantaneous decomposition rates were compared among the three water levels by repeated ANOVA analyses. The water level was the main factor, and time was the repeated factor. The intrinsic litter decomposition rate-limiting factor was analysed by the stepwise regression method in a multiple regression model. The surface soil chemical components and the microbial community structure were compared by two-way ANOVA. Treatment (with or without litter input) and water level were the main factors. The percentage differences in litter dry weight loss, the instantaneous decomposition rates, the soil chemical components, and the microbial community structure were evaluated by least significant difference (LSD) at the 0.05 significance level. The data were expressed as means ± standard error. All statistical analyses were performed in SPSS 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

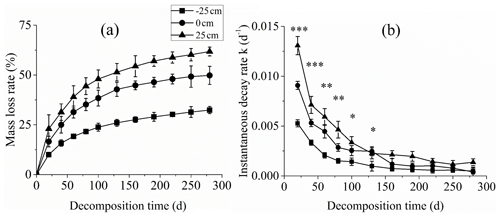

3.1 Litter decomposition process

The percentage of litter dry weight loss was the highest for the +25 cm water level treatment through the entire litter decomposition period followed by the 0 cm water level treatment. The percentage of litter dry weight loss was the lowest for the −25 cm water level treatment (P<0.01; Fig. 2a). After 280 d decomposition, the percentage litter dry weight loss values under the +25, 0, and −25 cm water level treatments were 61.8 %, 49.8 % and 32.4 %, respectively.

The instantaneous decomposition rate at each measurement time point was calculated based on the Olson negative exponential attenuation model and double exponential decay model. The instantaneous decomposition rate was highest at initial and slowly decreased and stabilised for all three water levels. The maximum decomposition rates for the −25, 0, and +25 cm water levels were 0.00527, 0.00908, and 0.01307 d−1, respectively (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2Percentage litter dry weight loss and decomposition rate during C. brevicuspis decomposition at three water levels (−25, 0, and +25 cm). *, **, and *** represent significant differences of the litter instantaneous decay rate among the three water levels at the 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 significance levels, respectively.

3.2 Intrinsic litter decomposition rate-limiting factor

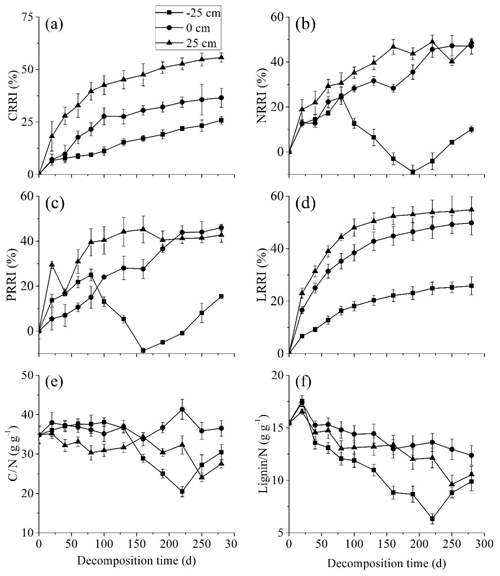

During the entire decomposition process, CRRI, NRRI, PRRI, and LRRI significantly increased with the water level. Litter carbon and lignin were always released at all three water levels whilst at −25 cm, nitrogen and phosphorus enrichment appeared in the middle stage (Fig. 3a–d). At the start of the experiment, neither the C∕N nor the lignin∕N ratio significantly differed at the three water levels. At the middle stage, however, both the C∕N and lignin∕N ratios were significantly lower at the −25 cm water level than they were at the 0 and −25 cm water levels (Fig. 3e–f).

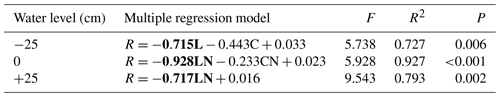

The multiple regression model of the instantaneous litter decomposition rate and the litter properties showed that at the −25 cm water levels, the main decomposition rate-limiting factor was the lignin concentration whilst at the 0 and +25 cm water level, the main litter decomposition rate-limiting factor was the lignin∕N ratio (Table 1).

Table 1Multiple regression model of instantaneous litter decomposition rate and litter properties. Bold indicates the key factors.

R is the litter instantaneous decomposition rate, L is the lignin concentration, CN is the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C∕N, g g−1), and LN is the lignin-to-nitrogen ratio (lignin∕N, g g−1). All indicators used to analyse the model refer to the content at each time point.

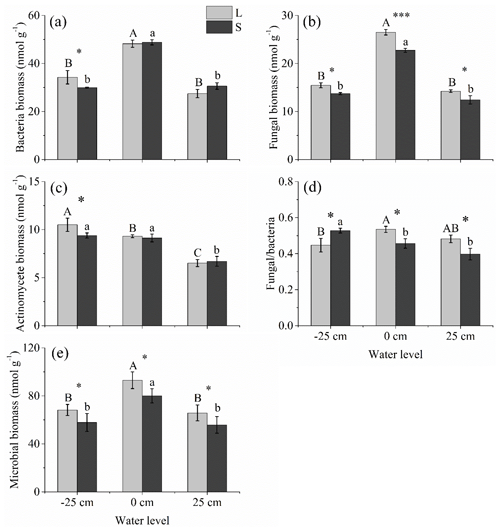

3.3 Soil surface microbial community structure

Under both litter input and litter removal conditions, the bacterial, fungal, and microbial biomass levels were the highest under the 0 cm water level treatment; however, these parameters showed nonsignificant differences between +25 cm above and below water level treatments (P>0.05; Fig. 4a, b, and f). The actinomycete biomass was the highest under the −25 cm water level treatment, followed by that under the 0 cm water level treatment. It was the lowest under the +25 cm water level treatment (Fig. 4c). Litter input significantly stimulated fungal and microbial biomass at all three water levels but only significantly stimulated bacterial and actinomycete biomass at the −25 cm water level (P<0.05; Fig. 4a–c and e). Under litter input conditions, the fungal∕bacteria ratio was the highest at the 0 cm water level, followed by the +25 cm water level. It was the lowest under the −25 cm water level treatment. Under litter removal conditions, however, the fungal∕bacteria ratio was significantly higher under the −25 cm water level treatment than it was under the 0 cm and +25 cm water level treatments (P<0.05; Fig. 4d).

Figure 4Microbial community structure under litter input and litter removal at three water levels. Different uppercase letters among vertical bars indicate significant differences among the three water levels in the litter input (L) group. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the three water levels in the litter removal (S) group. The significance level is α=0.05. *, **, and *** represent significant differences between the litter input (L) and litter removal (S) groups at the three water levels at the 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 significance levels, respectively.

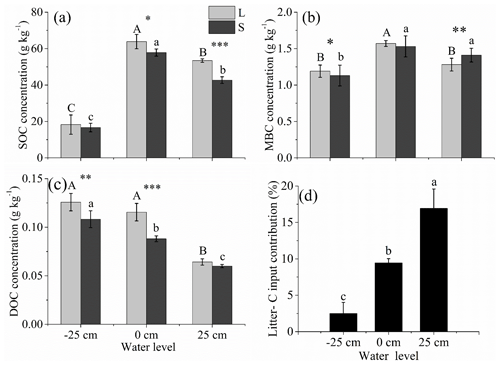

3.4 Contribution of leaf decomposition to the soil surface carbon pool

The SOC, MBC, and DOC concentrations were significantly affected by the water level. The SOC and MBC were the highest at the 0 cm water level and the lowest at the −25 cm water level (P<0.01; Fig. 5a and b). The DOC was the highest at the −25 cm water level and the lowest at the +25 cm water level (P<0.01; Fig. 5c).

Compared with the litter removal group, the SOC concentrations were significantly higher for the litter input group at the +25 and 0 cm water levels. Relative to the litter removal group, the DOC concentrations were significantly higher for the litter input group at the 0 and −25 cm water levels (P<0.001; Fig. 5a and c). The contribution of the litter-C input to the S-SOCP was the highest for the +25 cm water level treatment (16.93 %), intermediate for the 0 cm water level treatment (9.44 %), and the lowest for the −25 cm water level treatment (2.51 %) (P<0.001; Fig. 5d).

Figure 5Concentrations of SOC (a), MBC (b), DOC (c) between the litter input (L) and litter removal (S) groups and the litter-C input contribution (d) under three water levels at the end of the experiment. Different uppercase letters among vertical bars indicate significant differences among the three water levels in the litter input (L) group. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the three water levels in the litter removal (S) group. The significance level is α=0.05. *, **, and *** represent significant differences between the litter input (L) and litter removal (S) groups at the three water levels at the 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 significance levels, respectively.

4.1 Environmental control of litter decomposition

The water level significantly influenced C. brevicuspis leaf litter decomposition (P<0.001). The instantaneous decomposition rates (k) were the highest for the +25 cm water level treatment, intermediate for the 0 cm water level treatment, and the lowest for the −25 cm water level treatment (Fig. 2b). Hence, the percentage litter dry weight loss and the decomposition rate increased with the water level, which supported our first hypothesis. The wetland water level strongly affects litter leaching and microbial decomposition (Peltoniemi et al., 2012). Related research showed that the wetland water level strongly affects litter leaching and microbial decomposition (Peltoniemi et al., 2012). Molles et al. (1995) also found that compared with the terrestrial environment, in wetland, water promotes litter leaching and microbial metabolism, thereby accelerating litter decomposition. Moreover, water infiltration into litter also increases relative leaching loss (Molles et al., 1995). Here, the high litter decomposition rate measured for the +25 cm water level treatment may be explained primarily by litter leaching. This finding was consistent with results reported for Carex cinerascens litter decomposition in Poyang Lake (Zhang et al., 2019) and Calamagrostis angustifolia litter decomposition on the Sanjiang Plain (Sun et al., 2012).

The high soil total microbial, bacterial, and fungal biomass levels at the 0 cm water level could account for the rapid litter decomposition observed there. Certain microorganisms are vital to the decomposition process (Yarwood, 2018). Fungi are primary litter decomposers as they fragment dead plant tissues by breaking down lignin and cellulose. Bacteria are secondary decomposers that utilise the simpler compounds generated by fungal activity (de Boer et al., 2005; Bani et al., 2019). Microbial decomposers generally flourish in humid environments. At the 0 cm water level, microbial activity explains most of the litter decomposition. However, at the −25 cm water level, there are comparatively few microbial decomposers, and decomposition is very slow.

4.2 Intrinsic factors controlling litter decomposition

The instantaneous decomposition rate was highest at initial and slowly decreased and stabilised for all three water levels (Fig. 2b). Water-soluble components and non-lignin carbohydrates are preferentially and quickly decomposed at the initial of decomposition (Davis et al., 2003). Here, a multiple regression model of the instantaneous litter decomposition rate and litter properties showed that the internal limiting factors affecting the rate of C. brevicuspis leaf litter decomposition varied with the water level. The lignin concentration determined the litter decomposition rate for the −25 cm water level treatment whilst the lignin∕N ratio regulated the litter decomposition rate for the 0 and +25 cm water level treatment. This discovery upheld our second hypothesis and was consistent with the findings of Zhang et al. (2019), who reported that wetland ecosystems decomposed Carex cinerascens lignin much earlier and faster than terrestrial ecosystems. Here, we found that the lignin content was the major internal limiting factor of the C. brevicuspis leaf litter decomposition rate at −25 cm water level. At the 0 and +25 cm water level, N is rapidly lost, and the L∕N ratio significantly increases. Thus, L∕N is the main internal limiting factor at the 0 and +25 cm water levels. A few studies have shown that the lignin content is a key factor limiting terrestrial plant and hygrophyte litter decomposition (Yue et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018). Therefore, the amount of carbon that the litter can return to the ecosystem is closely associated with the plant lignin content. The lignin content of C. brevicuspis leaf litters is ∼ 10 % less than that of other wetland plants such as Miscanthus sacchariflorus (∼ 30 %) (Xie et al., 2016a), Spartina alterniflora (∼ 40 %) (Yan et al., 2019), and terrestrial plants such as willow (∼ 25 %), larch (∼ 38 %), and cypress (∼ 28 %) (Yue et al., 2016), so the C. brevicuspis leaf litter is more easily leached and then contributes more to the SOC pool. Furthermore, in Dongting Lake wetland, the Carex genus covers a large area (∼ 23 950 hm2) and generates abundant litter (∼ 36 547 t) (Kang et al., 2009). Thus, C. brevicuspis litter may potentially return large amounts of carbon to the soil.

4.3 Contribution of leaf decomposition to the soil surface carbon pool

Litter decomposition is the main pathway by which nutrients are transferred from the plants to the soil. Litter affects the SOC, the stabilisation of which affects other soil properties such as sorption, nutrient availability, pH, and water-holding capacity (Liu et al., 2017). The results of this study showed that litter addition increases SOC in a manner that varies with the water level. The contribution of litter-C input to the S-SOCP was the highest under the +25 cm water level treatment (16.93 %), intermediate under the 0 cm water level treatment (9.44 %), and the lowest under the −25 cm water level treatment (2.51 %). For this reason, flooding conditions are conducive to litter carbon input into the soil. These findings corroborated our third hypothesis. In addition, litter input had a similar effect on soil DOC at the 0 and −25 cm water levels. Therefore, litter decomposition contributes mainly soluble carbon to the soil (Zhou et al., 2015). However, this DOC is also readily lost and decomposed (Sokol and Bradford, 2019; Gomez-Casanovas et al., 2020). This fact accounts for the significantly lower relative DOC under the +25 cm water level treatment here. Wetlands have comparatively larger but also more unstable S-SOCPs than terrestrial environments. In wetlands, water level fluctuations could readily cause carbon loss (Gao et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2018). The SOC differences among three water levels were caused by different soil mineralisation in different environments. Soil mineralisation in aerobic environment (−25 cm) was significantly higher than that in the flooded environment (0, +25 cm) (Qiu et al., 2018), so the SOC at −25 cm water level was lower than the other two water levels. Nevertheless, we considered mainly aboveground litter in this experiment. Hence, the influence of underground litter (root) decomposition on the SOC pool should be investigated in future research (Sokol and Bradford, 2019; Lyu et al., 2019).

In this study, we quantified the contribution of leaf litter decomposition on soil surface organic carbon pools (S-SOCPs) under different water level conditions. Appropriate flooding (+25 cm water level treatment in our study) can significantly promote the decomposition of litter and contribute about 16.93 % organic carbon to S-SOCPs. Under waterlogging condition (0 cm water level), litter decomposition, which mainly controlled by microbial activity, contributed 9.44 % organic carbon to S-SOCP. However, under relative drought conditions (−25 cm water level treatment in our study), litter decomposition only contributes about 2.51 % organic carbon to S-SOCP, which is largely ascribed to the slower decomposition rate and soil carbon lost by microbe metabolism (i.e. actinomycetes). We also found that lignin or lignin∕N content were intrinsic factors controlling the litter decomposition rate in Carex brevicuspis. In Dongting Lake floodplain, the groundwater decline due to climate change and human disturbance would slow down the return rate of organic carbon from leaf litter to the soil and facilitate the S-SOCP loss.

The data used in this paper are stored in the open-access online database Figshare and can be accessed using the following link: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12758387.v1 (Zhu et al., 2020).

LZ designed experiments, collected samples, acquired, analysed, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. ZD designed experiments, interpreted data, and revised the manuscript. YX designed experiments and revised the manuscript. XL, FL, XC and YZ collected samples and revised the manuscript. CZ and WW interpreted data and revised the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We are immensely thankful to the teachers at the Dongting Lake Station and Key Laboratory of Agro-ecological Processes in Subtropical Region for their help in soil sample collection and chemical analysis. We would like to thank Editage (https://www.editage.cn/, last access: 18 September 2020) for English language editing of an earlier version of the manuscript.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 32071576), the Hunan innovative province construction projection (grant no. 2019NK2011), the Changsha Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholar (grant no. 2020), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan province (grant no. 2020JJ4101).

This paper was edited by Michael Weintraub and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Bani, A., Borruso, L., Nicholass, K. J. M., Bardelli, T., Polo, A., Pioli, S., Gomez-Brandon, M., Insam, H., Dumbrell, A. J., and Brusetti, L.: Site-Specific Microbial Decomposer Communities Do Not Imply Faster Decomposition: Results from a Litter Transplantation Experiment, Microorganisms, 7, 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7090349, 2019.

Berg, B.: Decomposition patterns for foliar litter – A theory for influencing factors, Soil Biol. Biochem., 78, 222–232, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.08.005, 2014.

Bossio, D. A. and Scow, K. M.: Impacts of carbon and flooding on soil microbial communities: Phospholipid fatty acid profiles and substrate utilization patterns, Microb. Ecol., 35, 265–278, https://doi.org/10.1007/s002489900082, 1998.

Bowden, R. D., Deem, L., Plante, A. F., Peltre, C., Nadelhoffer, K., and Lajtha, K.: Litter Input Controls on Soil Carbon in a Temperate Deciduous Forest, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J., 78, 66–75, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2013.09.0413nafsc, 2014.

Cao, J. B., He, X. X., Chen, Y. Q., Chen, Y. P., Zhang, Y. J., Yu, S. Q., Zhou, L. X., Liu, Z. F., Zhang, C. L., and Fu, S. L.: Leaf litter contributes more to soil organic carbon than fine roots in two 10-year-old subtropical plantations, Sci. Total Environ., 704, 135341, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135341, 2020.

Chen, H. Y., Zou, J. Y., Cui, J., Nie, M., and Fang, C. M.: Wetland drying increases the temperature sensitivity of soil respiration, Soil Biol. Biochem., 120, 24–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.01.035, 2018.

Chen, X. S., Deng, Z. M., Xie, Y. H., Li, F., Hou, Z. Y., and Wu, C.: Consequences of Repeated Defoliation on Belowground Bud Banks of Carex brevicuspis (Cyperaceae) in the Dongting Lake Wetlands, China, Front. Plant Sci., 7, 1119, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01119, 2016.

Davis, S. E., Corronado-Molina, C., Childers, D. L., and Day, J. W.: Temporally dependent C, N, and P dynamics associated with the decay of Rhizophora mangle L. leaf litter in oligotrophic mangrove wetlands of the Southern Everglades, Aquat. Bot., 75, 199–215, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3770(02)00176-6, 2003.

de Boer, W., Folman, L. B., Summerbell, R. C., and Boddy, L.: Living in a fungal world: impact of fungi on soil bacterial niche development, Fems Microbiol. Rev., 29, 795–811, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsre.2004.11.005, 2005.

Deng, Z. M., Li, Y. Z., Xie, Y. H., Peng, C. H., Chen, X. S., Li, F., Ren, Y. J., Pan, B. H., and Zhang, C. Y.: Hydrologic and Edaphic Controls on Soil Carbon Emission in Dongting Lake Floodplain, China, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 123, 3088–3097, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018jg004515, 2018.

Gao, J. Q., Feng, J., Zhang, X. W., Yu, F. H., Xu, X. L., and Kuzyakov, Y.: Drying-rewetting cycles alter carbon and nitrogen mineralization in litter-amended alpine wetland soil, Catena, 145, 285–290, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2016.06.026, 2016.

Gomez-Casanovas, N., DeLucia, N. J., DeLucia, E. H., Blanc-Betes, E., Boughton, E. H., Sparks, J., and Bernacchi, C. J.: Seasonal Controls of CO2 and CH4 Dynamics in a Temporarily Flooded Subtropical Wetland, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeosc., 125, 18, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019jg005257, 2020.

Graça, M. A. S., Bärlocher, F., and Gessner, M. O.: Methods to Study Litter Decomposition, Springer Netherlands, Germany, 2005.

Hoyos-Santillan, J., Lomax, B. H., Large, D., Turner, B. L., Boom, A., Lopez, O. R., and Sjogersten, S.: Getting to the root of the problem: litter decomposition and peat formation in lowland Neotropical peatlands, Biogeochemistry, 126, 115–129, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-015-0147-7, 2015.

Hu, J. Y., Xie, Y. H., Tang, Y., Li, F., and Zou, Y. A.: Changes of Vegetation Distribution in the East Dongting Lake After the Operation of the Three Gorges Dam, China, Front. Plant Sci., 9, 582, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00582, 2018.

Kang, W. X., Tian, H., Jie-Nan, H. E., Hong-Zheng, X. I., Cui, S. S., and Yan-Ping, H. U.: Carbon Storage of the Wetland Vegetation Ecosystem and Its Distribution in Dongting Lake, J. Soil Water Conserv., 23, 129–133, https://doi.org/10.13870/j.cnki.stbcxb.2009.06.053, 2009.

Kayranli, B., Scholz, M., Mustafa, A., and Hedmark, A.: Carbon Storage and Fluxes within Freshwater Wetlands: a Critical Review, Wetlands, 30, 111–124, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-009-0003-4, 2010.

Köchy, M., Hiederer, R., and Freibauer, A.: Global distribution of soil organic carbon – Part 1: Masses and frequency distributions of SOC stocks for the tropics, permafrost regions, wetlands, and the world, SOIL, 1, 351–365, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-1-351-2015, 2015.

Liu, S. L., Jiang, Z. J., Deng, Y. Q., Wu, Y. C., Zhao, C. Y., Zhang, J. P., Shen, Y., and Huang, X. P.: Effects of seagrass leaf litter decomposition on sediment organic carbon composition and the key transformation processes, Sci. China-Earth Sci., 60, 2108–2117, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-017-9147-4, 2017.

Lv, F. C. and Wang, X. D.: Contribution of Litters to Soil Respiration : A Review, Soils, 49, 225–231, 2017.

Lyu, M. K., Li, X. J., Xie, J. S., Homyak, P. M., Ukonmaanaho, L., Yang, Z. J., Liu, X. F., Ruan, C. Y., and Yang, Y. S.: Root-microbial interaction accelerates soil nitrogen depletion but not soil carbon after increasing litter inputs to a coniferous forest, Plant and Soil, 444, 153–164, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-019-04265-w, 2019.

Molles, M. C., Crawford, C. S., and Ellis, L. M.: Effects of an experimental flood on litter dynamics in the middle Rio Grande riparian ecosystem, Regul. Rivers-Res. Manage., 11, 275–281, https://doi.org/10.1002/rrr.3450110304, 1995.

Moriyama, A., Yonemura, S., Kawashima, S., Du, M. Y., and Tang, Y. H.: Environmental indicators for estimating the potential soil respiration rate in alpine zone, Ecol. Indic., 32, 245–252, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.03.032, 2013.

Olson, J. S.: Energy-storage and balabce of producers and decomposers in ecological- systems, Ecology, 44, 322–331, https://doi.org/10.2307/1932179, 1963.

Peltoniemi, K., Strakova, P., Fritze, H., Iraizoz, P. A., Pennanen, T., and Laiho, R.: How water-level drawdown modifies litter-decomposing fungal and actinobacterial communities in boreal peatlands, Soil Biol. Biochem., 51, 20–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.04.013, 2012.

Peng, P. Q., Zhang, W. J., Tong, C. L., Qiu, S. J., and Zhang, W. C.: Soil C, N and P contents and their relationships with soil physical properties in wetlands of Dongting Lake floodplain, J. Appl. Ecol., 16, 1872–1878, 2005.

Pinto, O. B., Vourlitis, G. L., Carneiro, E. M. D., Dias, M. D., Hentz, C., and Nogueira, J. D.: Interactions between Vegetation, Hydrology, and Litter Inputs on Decomposition and Soil CO2 Efflux of Tropical Forests in the Brazilian Pantanal, Forests, 9, 281, https://doi.org/10.3390/f9050281, 2018.

Qiu, H. S., Ge, T. D., Liu, J. Y., Chen, X. B., Hu, Y. J., Wu, J. S., Su, Y. R., and Kuzyakov, Y.: Effects of biotic and abiotic factors on soil organic matter mineralization: Experiments and struc tural modeling analysis, Eur. J. Soil Biol., 84, 27–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2017.12.003, 2018.

Sokol, N. W. and Bradford, M. A.: Microbial formation of stable soil carbon is more efficient from belowground than aboveground input, Nat. Geosci., 12, 46–53, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0258-6, 2019.

Song, Y. Y., Song, C. C., Tao, B. X., Wang, J. Y., Zhu, X. Y., and Wang, X. W.: Short-term responses of soil enzyme activities and carbon mineralization to added nitrogen and litter in a freshwater marsh of Northeast China, Eur. J. Soil Biol., 61, 72–79, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2014.02.001, 2014.

Sun, X. L., Kong, F. L., Li, Y., Di, L. Y., and Xi, M.: Effects of litter decomposition on contents and three-dimensional fluorescence spectroscopy characteristics of soil labile organic carbon in coastal wetlands of Jiaozhou Bay, China, J. Appl. Ecol., 30, 563–572, https://doi.org/10.13287/j.1001-9332.201902.036, 2019.

Sun, Z. G., Mou, X. J., and Liu, J. S.: Effects of flooding regimes on the decomposition and nutrient dynamics of Calamagrostis angustifolia litter in the Sanjiang Plain of China, Environ. Earth Sci., 66, 2235–2246, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-011-1444-7, 2012.

Tong, C., Cadillo-Quiroz, H., Zeng, Z. H., She, C. X., Yang, P., and Huang, J. F.: Changes of community structure and abundance of methanogens in soils along a freshwater-brackish water gradient in subtropical estuarine marshes, Geoderma, 299, 101–110, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2017.03.026, 2017.

Van de Moortel, A. M. K., Du Laing, G., De Pauw, N., and Tack, F. M. G.: The role of the litter compartment in a constructed floating wetland, Ecol. Eng., 39, 71–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2011.11.003, 2012.

Wang, X. L., Xu, L. G., and Wan, R. R.: Comparison on soil organic carbon within two typical wetland areas along the vegetation gradient of Poyang Lake, China, Hydrol. Res., 47, 261–277, https://doi.org/10.2166/nh.2016.218, 2016.

Whiting, G. J. and Chanton, J. P.: Greenhouse carbon balance of wetlands: methane emission versus carbon sequestration, Tellus B, 53, 521–528, https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0889.2001.530501.x, 2001.

Wilkinson, S. C., Anderson, J. M., Scardelis, S. P., Tisiafouli, M., Taylor, A., and Wolters, V.: PLFA profiles of microbial communities in decomposing conifer litters subject to moisture stress, Soil Biol. Biochem., 34, 189–200, 2002.

Xie, Y., Xie, Y., Chen, X., Li, F., Hou, Z., and Li, X.: Non-additive effects of water availability and litter quality on decomposition of litter mixtures, J. Freshwater Ecol., 31, 153–168, https://doi.org/10.1080/02705060.2015.1079559, 2016a.

Xie, Y. J., Xie, Y. H., Hu, C., Chen, X. S., and Li, F.: Interaction between litter quality and simulated water depths on decomposition of two emergent macrophytes, J. Limnol., 75, 36–43, https://doi.org/10.4081/jlimnol.2015.1119, 2016b.

Xie, Y. J., Xie, Y. H., Xiao, H. Y., Chen, X. S., and Li, F.: Controls on Litter Decomposition of Emergent Macrophyte in Dongting Lake Wetlands, Ecosystems, 20, 1383–1389, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-017-0119-y, 2017.

Yan, J. F., Wang, L., Hu, Y., Tsang, Y. F., Zhang, Y. N., Wu, J. H., Fu, X. H., and Sun, Y.: Plant litter composition selects different soil microbial structures and in turn drives different litter decomposition pattern and soil carbon sequestration capability, Geoderma, 319, 194–203, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.01.009, 2018.

Yan, Z. Z., Xu, Y., Zhang, Q. Q., Qu, J. G., and Li, X. Z.: Decomposition of Spartina alterniflora and concomitant metal release dynamics in a tidal environment, Sci. Total Environ., 663, 867–877, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.422, 2019.

Yarwood, S. A.: The role of wetland microorganisms in plant-litter decomposition and soil organic matter formation: a critical review, Fems Microbiol. Ecol., 94, 17, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiy175, 2018.

Yu, X. F., Ding, S. S., Lin, Q. X., Wang, G. P., Wang, C. L., Zheng, S. J., and Zou, Y. C.: Wetland plant litter decomposition occurring during the freeze season under disparate flooded conditions, Sci. Total Environ., 706, 136091, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136091, 2020.

Yue, K., Peng, C. H., Yang, W. Q., Peng, Y., Zhang, C., Huang, C. P., and Wu, F. Z.: Degradation of lignin and cellulose during foliar litter decomposition in an alpine forest river, Ecosphere, 7, 11, https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1523, 2016.

Zhang, G. S., Yu, X. B., Gao, Y., Li, Y., Zhang, Q. J., Liu, Y., Rao, D. D., Lin, Y. M., and Xia, S. X.: Effects of water table on cellulose and lignin degradation of Carex cinerascens in a large seasonal floodplain, J. Freshw. Ecol., 33, 311–325, https://doi.org/10.1080/02705060.2018.1459324, 2018.

Zhang, L., Zhou, G. S., Ji, Y. H., and Bai, Y. F.: Grassland Carbon Budget and Its Driving Factors of the Subtropical and Tropical Monsoon Region in China During 1961 to 2013, Sci. Rep.-UK, 7, 14717, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15296-7, 2017.

Zhang, Q. J., Zhang, G. S., Yu, X. B., Liu, Y., Xia, S. X., Ya, L., Hu, B. H., and Wan, S. X.: Effect of ground water level on the release of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus during decomposition of Carex, cinerascens Kukenth in the typical seasonal floodplain in dry season, J. Freshwater Ecol., 34, 305–322, https://doi.org/10.1080/02705060.2019.1584128, 2019.

Zhao, J., Zeng, Z. X., He, X. Y., Chen, H. S., and Wang, K. L.: Effects of monoculture and mixed culture of grass and legume forage species on soil microbial community structure under different levels of nitrogen fertilization, Eur. J. Soil Biol., 68, 61–68, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2015.03.008, 2015.

Zhou, W. J., Sha, L. Q., Schaefer, D. A., Zhang, Y. P., Song, Q. H., Tan, Z. H., Deng, Y., Deng, X. B., and Guan, H. L.: Direct effects of litter decomposition on soil dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen in a tropical rainforest, Soil Biol. Biochem., 81, 255–258, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.11.019, 2015.

Zhu, L., Deng, Z., Xie, Y., Li, X., Li, F., Chen, X., Zou, Y., Zhang, C., and Wang, W.: Factors controlling Carex brevicuspis leaf litter decomposition and its contribution to surface soil organic carbon pool at different water levels.xlsx, figshare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12758387.v1, 2020.