the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Low site diversity but high diversity across sites of depauperate Crustacea and Annelida communities in groundwater of urban wells in Kraków, Poland

Elżbieta Dumnicka

Joanna Galas

Tadeusz Namiotko

Agnieszka Pociecha

Crustaceans and annelids are key components of groundwater communities, influenced by both abiotic conditions and biotic interactions. This study assessed their diversity in urban groundwaters accessed via 91 dug/drilled wells in Kraków, southern Poland, subject to chronic anthropogenic disturbance. Invertebrates were recorded in 47 wells, with 19 species-group taxa identified from 28 wells, including eight annelid and 11 crustacean taxa (Ostracoda: 3; Copepoda: 6; Bathynellacea: 1; Amphipoda: 1). Six stygobitic taxa were detected in 10 wells: Trichodrilus cernosvitovi, Trichodrilus sp., Typhlocypris cf. eremita, Diacyclops gr. languidoides, Bathynella natans, and Niphargus cf. tatrensis. Due to some taxonomic uncertainties, open nomenclature was used where necessary. Species accumulation did not reach saturation, but extrapolation suggested the sampling was exhaustive. Alpha diversity was low (1–3 species per well, mean =1.4), while beta diversity was high (Whittaker index =12.3), indicating substantial species turnover, a typical feature of groundwater ecosystems. No clear seasonal trends were observed, consistent with previous studies in Kraków. Four main community types were identified. One, dominated by Enchytraeus gr. buchholzi, may indicate degraded conditions, another, with Bathynella natans and Aeolosoma spp., suggests transitional states; a third, dominated by Trichodrilus spp., likely reflects relatively undisturbed groundwater; and a fourth, more heterogeneous type dominated by surface copepods, was ecologically ambiguous. Despite generally low richness and dominance by surface taxa, the presence of six stygobitic species suggests that at least 20 % of the surveyed wells retain relatively good ecological conditions.

- Article

(4425 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(483 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Urban wells, constructed for various purposes, provide convenient access to groundwater and offer valuable opportunities for studying subterranean aquatic fauna. Urban expansion is a global phenomenon, with cities continuously increasing in area (Kraków in southern Poland, for instance, has expanded by 42 % since 1950), often encompassing regions of high conservation value. In urban settings, groundwater is frequently exposed to various types of pollution, including chemical, organic, and thermal contaminants (Kim, 1992; Burri et al., 2019; Becher et al., 2022), which pose significant risks to subterranean fauna. These threats are increasingly recognized, prompting frequent assessments of water chemistry and microbial communities. Consequently, the monitoring of groundwater quality has become a standard practice in many European countries under the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD, 2000) and the Groundwater Directive (GWD, 2006).

Despite the ecological significance of urban groundwater ecosystems, the invertebrate fauna of urban wells has historically been studied in only a limited number of European cities. Some of the earliest and most extensive research was conducted in Prague, Czech Republic, by Vejdovský (1882), Sládeček and Řehačková (1952), Řehačková (1953), and Ertl (1957). Additional historical studies include those by Moniez (1888–1889) in Lille (France), Jaworowski (1893) in wells of Lviv (Ukraine) and Kraków, Chappuis (1924) in Basel, and Vornatscher (1972) on crustaceans in Vienna. After a long hiatus, interest in urban groundwater fauna has recently resurged, with studies by Koch et al. (2021), Becher et al. (2022, 2024), Englisch et al. (2024), and Meyer et al. (2024). Only very recently have systematic efforts to monitor groundwater fauna in cities been initiated (Johns, 2024), underscoring the growing importance of this field. Earlier publications focused primarily on species inventories, whereas recent studies have increasingly addressed the impacts of urbanization and patterns of biodiversity.

The most commonly encountered invertebrate groups in urban wells are annelids and crustaceans. In Poland, annelids have been relatively well studied in various subterranean habitats, including rural wells, and additional records have been provided in the course of other ecological research. These data were comprehensively reviewed by Dumnicka et al. (2020). A checklist of Polish groundwater crustaceans was compiled by Pociecha et al. (2021), and subsequently complemented by Karpowicz et al. (2021) and Karpowicz and Smolska (2024). The distribution of the amphipod genus Niphargus in Poland has been particularly well documented, primarily through the work of Skalski (e.g., 1970, 1981), with a synthesis provided by Dumnicka and Galas (2017) and additional records recently reported (Andrzej Górny, personal communication, 2023).

Despite this progress, the subterranean aquatic fauna of urban areas in Poland remains insufficiently explored. In Kraków, local geology and contamination patterns have been shown to influence species presence and distribution (Dumnicka et al., 2025).

The aim of this study was to assess the taxonomic diversity of annelid and crustacean communities inhabiting groundwater from 91 urban wells in Kraków, estimate total species richness, evaluate seasonal variation, and identify major community types. These insights may help determine whether groundwater in at least some of these wells still retains a reasonably good ecological state.

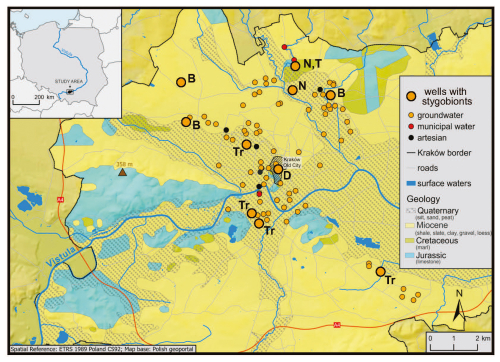

Figure 1Map of the study area showing the locations of urban wells sampled within the Kraków metropolitan area for the study of annelids and crustaceans (modified from Dumnicka et al., 2025). Wells where stygobionts were detected are marked as follows: B = Bathynella natans, D = Diacyclops gr. languidoides, N = Niphargus cf. tatrensis, T = Typhlocypris cf. eremita, Tr = Trichodrilus spp. juv T. cernosvitovi.

2.1 Study area and sampling sites

Kraków is located at the junction of three tectonic units: the Silesian-Kraków Monocline, the Miechów Basin, and the Precarpathian Depression, which results in a highly complex geological and hydrogeological structure of this area (Kleczkowski et al., 2009). The studied urban wells are distributed across the city, from the historic Old Market Square to the outer residential districts (Fig. 1). Most wells are situated in Quaternary sediments composed of gravel and sand, with occasional inclusions of peat and silt. In the city center, these are overlain by a few-meter-thick layer of anthropogenic deposits. Other wells are located in Neogene (Miocene) sediments composed of various lithologies, such as marls, shales, and gypsum (gypsum-salt formations) (Rutkowski, 1989). The Vistula River flows through Kraków center and is fed by several tributaries (Fig. 1). Holocene fluvial sediments, mainly sands and gravels, occur within the river valleys.

According to the list obtained from the Kraków Water Company, approximately 350 bored/dug, driven or drilled wells were constructed in the area between the early 19th century and the 1980s. Currently, only about half of these are operational. For the present study, 83 such relatively shallow bored/dug wells were selected. Their depths range from 2.3 to 30.0 m, with a typical water column height of 2–4 m. These wells are primarily fed by percolating water from Quaternary aquifers; however, hydraulic connections with deeper Jurassic or Cretaceous layers have been identified in some locations (Chowaniec et al., 2007). Each well is equipped with a piston pump and is fully sealed at the surface (Fig. 2, left).

Figure 2Photographs of representative surveyed wells: left – bored/dug well with piston pump; right – artesian deep well with tap.

In addition, 11 deep artesian wells are present in the area. These wells reach the Jurassic aquifer at depths of 80–100 m and discharge groundwater to the surface without mechanical pumping due to artesian pressure (Rajchel, 1998). The emerging water is directed through pipes (Fig. 2, right). Five of these artesian wells were included in the study.

Finally, tap water samples were collected from three separate municipal water intakes. Although well water is not potable, it is occasionally used for purposes such as plant irrigation.

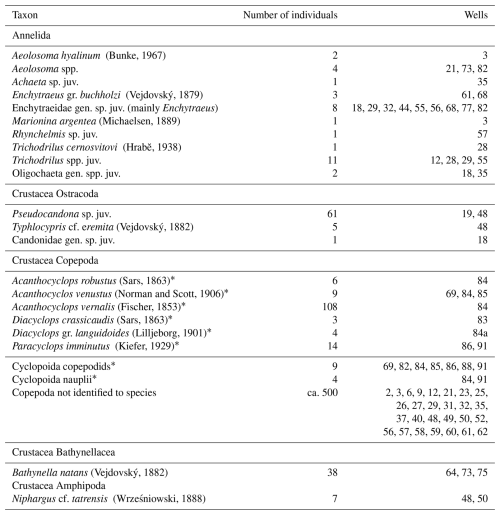

Table 1Occurrences of annelids and crustaceans in the studied urban wells in Kraków, Poland. Stygobitic species are shown in bold. Asterisks (*) indicate identifications based on samples collected only in 2020. Addresses of the numbered wells are provided in Table S1 in the Supplement. Complete data on water properties and the occurrences of other invertebrate groups are available in Dumnicka et al. (2025).

2.2 Sampling, sample processing and invertebrate identification

Sampling was conducted in two consecutive years, 2019 (59 wells) and 2020 (32 wells), with two sampling events per year: spring (April–June) and autumn (September–October). At each of the 91 sampling sites (see Table S1 and Fig. 1) and during each sampling event, 100 L of groundwater were filtered using a plankton net with a mesh size of 50 µm. Invertebrates were sorted live under a stereoscopic microscope and subsequently preserved in 95 % ethanol. Crustaceans and annelids were identified to the species level whenever possible, based on available literature (e.g., Meisch, 2000; Timm, 2009; Błędzki and Rybak, 2016). All taxa were analyzed in samples from both sampling years, with the exception of copepods, which were identified to species level only in the samples collected during the second year.

Water chemical and physical parameters were measured concurrently with biological sampling. Temperature and specific conductivity (at 25 °C) were recorded in situ using a portable multimeter (Elmetron CX-401). Ion concentrations were determined in the laboratory of the Institute of Geography and Spatial Management, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland, using ion chromatography following the methods described in Dumnicka et al. (2025).

2.3 Ecological and statistical analyses

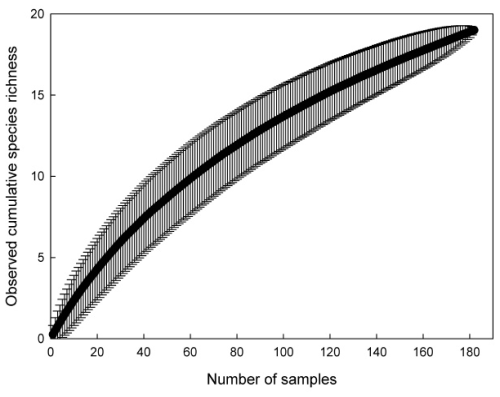

To assess whether the sampling effort was sufficient to capture the species richness of the studied area, species accumulation curves were generated using all 182 samples collected from the 91 wells. These curves illustrate how the number of detected species increases with the number of accumulated samples. Four standard non-parametric richness estimators based on abundance data (Chao 1, Jackknife 1, Bootstrap, and Michaelis-Menten) were also calculated to predict the total expected species richness. The mean (and standard deviation for Chao 1) of both observed and estimated species richness were calculated from 9999 permutations, with samples added in random order, using PAST v. 4.10 (Hammer et al., 2001) and the Species-Accumulation Plot routine in PRIMER 7 software (Clarke and Gorley, 2015).

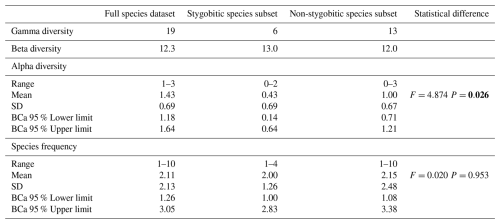

To evaluate biodiversity across the wells, several diversity metrics were computed using PAST v. 4.10 (Hammer et al., 2001) and in PRIMER 7 (Clarke and Gorley, 2015). These included: (a) alpha diversity (α) – species richness per site, (b) species frequency – number of wells in which each species was present, (c) gamma diversity (γ) – total species richness across all sites, and (d) beta diversity (β) – computed as Whittaker's species turnover index (). For both alpha diversity and species frequency, mean values, ranges, standard deviations, and and 95 % confidence intervals were estimated using the bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrap method with 9999 replicates. These diversity metrics were calculated separately for three datasets: (1) all species, (2) stygobitic species, and (3) non-stygobitic species. Differences in mean alpha diversity and mean species frequency between stygobitic and non-stygobitic groups were tested using one-way permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) with 9999 permutations in PRIMER 7 with the PERMANOVA+ add-on (Anderson et al., 2008).

To assess seasonal differences in the composition and structure of crustacean and annelid communities, non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS) was performed based on Bray-Curtis similarity matrices derived from species abundance data (with all-zero samples excluded). Seasonal differences were further tested using PERMANOVA (9999 permutations), implemented in PRIMER 7 with the PERMANOVA+ add-on.

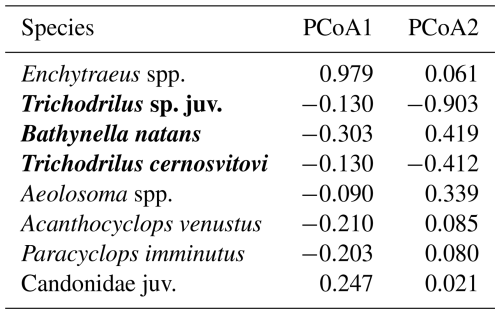

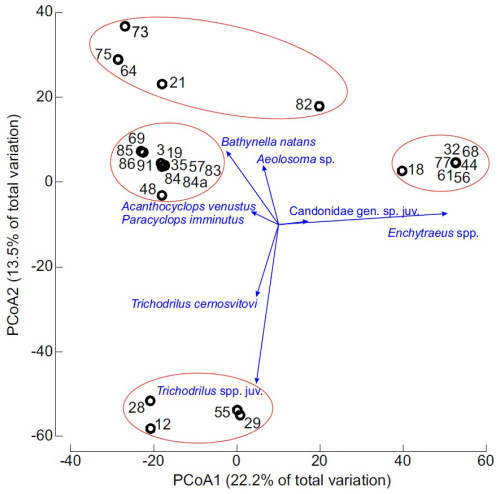

Finally, Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis similarity of relative abundance (percentage) data was used to visualize differences in community structure and composition of crustaceans and annelids among wells. Pearson correlation vectors (threshold >0.2) were overlaid on the PCoA plot to highlight taxa contributing most strongly to observed patterns. This analysis was also conducted using PRIMER 7 with the PERMANOVA+ add-on.

3.1 Groundwater physical and chemical properties

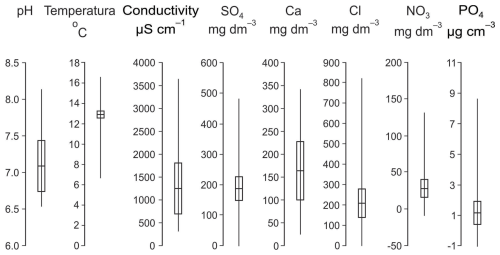

A summary of the variation in physical and chemical water properties across the studied wells is provided in Fig. 3, with detailed data available in Dumnicka et al. (2025).

Water temperature in all wells was relatively high, ranging from 9.7 to 16.2 °C, while pH values were predominantly circumneutral (6.5–8.2). Electrical conductivity ranged from 314 to 3641 µS cm−1, with a mean of 1276 µS cm−1, indicating soft to moderately hard water and generally low to moderate dissolved ion concentrations. Some wells exhibited elevated concentrations of sulphates and/or chlorides (>250 mg L−1), with values varying depending on well location and local pollution source. Nitrogen concentrations, in the form of nitrates and ammonium, also varied widely. A considerable proportion of wells were nitrate-enriched (>50 mg NO L−1) or ammonium-enriched (>0.5 mg NH L−1). Additionally, relatively high concentration of phosphates (>0.1 mg PO L−1) and of fluorides (>1.5 mg F− L−1) were recorded in some wells (Fig. 3).

3.2 Taxonomic richness and diversity

Crustaceans or annelids were recorded in 47 out of 91 wells (52 %), but these could be identified to species level in 28 wells (31 %), resulting in 19 species-group taxa (gamma diversity) belonging to Annelida and to four crustacean groups: Ostracoda, Copepoda, Bathynellacea, and Amphipoda, and representing both stygobitic and non-stygobitic ecological groups. Interestingly, there is low co-occurrence of the annelids and crustaceans within the same wells (Table 1). Other invertebrate taxa, including Microturbellaria, Nematoda, Rotifera, Collembola, and Diptera larvae, were also found but were excluded from further analysis as they were not identified to species level.

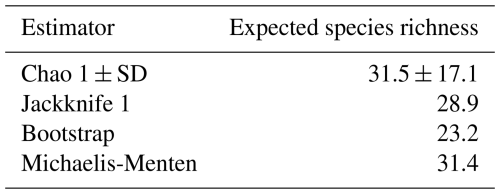

As expected given the rarity of many species, the species accumulation curve of the observed number of annelid and crustacean species based on all 182 samples from 91 wells did not reach an asymptote (Fig. 4), indicating incomplete sampling. Extrapolated species richness estimates ranged from 23.2 (Bootstrap) to 31.5 (Chao 1), suggesting that between 60.3 % and 81.9 % of the estimated total species pool of the studied area was captured (Table 2).

Table 2Estimated total number of species predicted by four extrapolation estimators based on abundance data for 19 crustacean and annelid species from 182 samples collected in 91 urban wells in Kraków. SD = standard deviation.

Figure 4Mean cumulative species richness of the 19 studied invertebrate species (including stygobitic and non-stygobitic annelids, ostracods, copepods, bathynellaceans, and amphipods) plotted against the number of 182 samples from 91 urban wells in Kraków. Whiskers represent ± 1 standard deviation.

Annelids were found in 17 wells (Table 1), and conservatively assigned to at least eight species. Many specimens were immature and were therefore left in open nomenclature. The semi-aquatic family Enchytraeidae was considered as represented by two species: one identified as Enchytraeus gr. buchholzi and one taxon of the genus Achaeta. Other recorded annelids included surface-dwelling Rhynchelmis (Lumbriculidae), treated as a single species due to immature material, two Aeolosoma species-group taxa, one identified as A. hyalinum, and stygobitic Trichodrilus, conservatively treated as two species-group taxa, one of which (T. cernosvitovi) was confirmed by a single mature individual.

Ostracods were recorded only in three wells and they were represented by at least three species of the family Candonidae, one stygobitic Typhlocypris cf. eremita, and two other surface dwelling species left in open nomenclature since the collected juvenile specimens were not identified down to the species level (representatives of the genus Pseudocandona) and neither at the species nor at the genus level (representatives of the family Candonidae) (Table 1).

Copepods were the most frequently recorded group, present in 37 wells. However, only specimens from the second sampling year were identified to species level and considered in further analyses. Six species were identified, most typical of small, astatic surface waters. A species belonging to Diacyclops languidoides group, recorded in a single well, was considered stygobitic (Table 1).

Two additional stygobitic crustaceans were noted: Bathynella natans (Bathynellacea) and Niphargus cf. tatrensis (Amphipoda) (Table 1).

Table 3Diversity measures for crustaceans and annelids found in the 28 out of 91 studied urban wells in Kraków, shown for the full dataset and separately for stygobitic and non-stygobitic species subsets. Gamma diversity = total species richness, Beta diversity = global Whittaker species turnover index, Alpha diversity = average species richness per well, Species frequency = number of wells in which species occurred. SD = standard deviation, BCa = bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap method. Differences in mean alpha diversity and species frequency between stygobitic and non-stygobitic datasets were tested using one-way permutational analysis of variance PERMANOVA: F= permutation-based test statistic, P= probability based on 9999 permutations. Statistically significant value is bolded.

Among the 28 wells where crustaceans and/or annelids were identified to species level, the most frequent species were Enchytraeus gr. buchholzi (found in 10 wells, 36 %) and Trichodrilus spp. (4 wells, 14 %). Notably, 10 species (53 %) were found in only one well (Table 1). The mean species occurrence frequency across the full dataset was 2.1 ± 2.0 wells (mean ± standard deviation SD), with no significant difference between stygobionts (2.0 ± 1.3) and non-stygobionts (2.2 ± 2.5) (PERMANOVA: F=0.020, P=0.953; Table 3).

Alpha diversity averaged 1.4 ± 0.7 species per well, ranging from 1 to 3. Stygobitic species exhibited significantly lower mean alpha diversity (0.4 ± 0.7) compared to non-stygobionts (1.0 ± 0.7) (PERMANOVA: F=4.874, P=0.026). Despite generally low alpha diversity, beta diversity (Whittaker index) was high for the entire dataset (12.3) and for both stygobionts (13.0) and non-stygobionts (12.0), indicating high species turnover among wells (Table 3). This is consistent with the PCoA results based on Bray-Curtis similarity for each pair of wells (see below).

3.3 Seasonal variation in community structure and composition

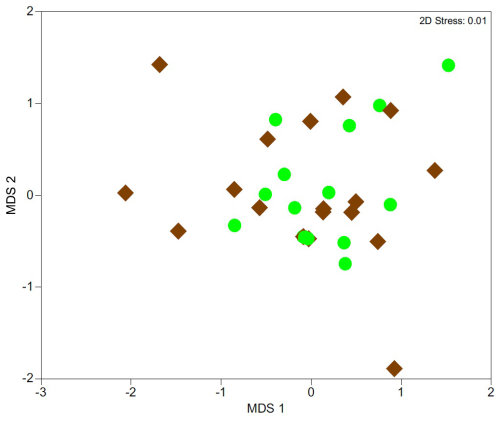

Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (nMDS) ordination revealed overlap between samples collected in spring and autumn (Fig. 5), suggesting no significant seasonal differences in the structure and composition of crustacean and annelid communities. This was supported by PERMANOVA (F=1.30, P=0.171).

3.4 Major community types

Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) revealed four distinct community types, with the first two axes explaining 35.7 % of the total variance (Fig. 6). Eight species/taxa exhibited the strongest correlations with the first two PCoA axes and contributed most to the observed pattern (Table 4). The first PCoA axis separated seven wells dominated by nearly monospecific community of Enchytraeus gr. buchholzi (with minor contribution from Candonidae ostracods), positioned on the right side of the plot, from three additional community types on the left. The lower-left quadrant grouped four wells dominated by stygobitic Trichodrilus spp. and Niphargus cf. tatrensis (with minor enchytraeid presence). The upper-left quadrant contained five wells with the community type characterized by Bathynella natans and Aeolosoma spp. Between these two community types were 12 wells representing a fourth, less clearly structured community type, distinguished primarily by the surface-dwelling copepods Acanthocyclops venustus and Paracyclops imminutus, along with various copepods, ostracods, amphipods, and annelids, including stygobionts.

Although invertebrates have been recorded in 74 of the 91 wells examined in this study, representing 81.3 % of the total (Dumnicka et al., 2025), which is comparable to the 81.6 % colonization rate observed in 201 wells in Munich (Becher et al., 2024), crustaceans and/or annelids were detected in only about half of these wells (52 %). Given the absence of significant differences in the main environmental variables between wells with and without invertebrates (Dumnicka et al., 2025), the absence of crustaceans and annelids in some wells is likely attributable to other natural factors or methodological constraints. These may include the limited dispersal capacity of these taxa in groundwater, the isolation of some aquifers, low population densities leading to non-detection during sampling, or unexamined environmental factors known to influence groundwater fauna (e.g., Marmonier et al., 2023; Hotèkpo et al., 2025), particularly in urban settings. Potential anthropogenic stressors include chemical pollution, oxygen depletion, and thermal disturbances (Becher et al., 2022). Notably, groundwater temperatures in Kraków wells were approximately 3 °C higher than those in rural wells located 30–40 km from the city (Dumnicka et al., 2017, 2025).

The availability of organic matter and dissolved oxygen, largely dependent on surface-subsurface water exchange, is essential for sustaining groundwater faunal communities. In urban environments, such exchange is often impeded be extensive built-up areas, impervious surfaces, and drainage infrastructure (Becher et al., 2022). Other water chemistry parameters of Kraków urban wells, such as mineralization and nutrient levels, shaped in part by the complex geology of the region (Kleczkowski et al., 2009; Gradziński and Gradziński, 2015), as well as local contamination, may also affect the faunal presence (Chowaniec et al., 2007; Dumnicka et al., 2025). Similar variability in groundwater chemistry has been reported from other European cities (Koch et al., 2021; Becher et al., 2022; Englisch et al., 2022; Meyer et al., 2024). Unfavourable chemical conditions, such as low oxygen or high salinity, may explain the absence of invertebrates in certain wells. Furthermore, the complete sealing of some wells and their location in “urban desert” areas likely inhibit colonization by surface-dwelling species, which can otherwise enhance local groundwater biodiversity. Given this isolation, colonization pathways for surface annelids and crustaceans remain difficult to trace – entry into groundwater likely occurs by chance, and populations may or may not persist. Surface water proximity and rainwater infiltration probably facilitate invertebrate access. In the wells studied in Kraków a substantial proportion of the annelid and crustacean communities consisted of surface-water taxa, a pattern also observed in other Polish wells (Dumnicka et al., 2020; Karpowicz et al., 2021; Pociecha et al., 2021) and those in other countries (e.g., Vejdovský, 1882; Moniez, 1888–1889; Řehačkova, 1953; Dalmas, 1973; Hahn et al., 2013; Bozkurt, 2023).

Figure 6Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) of annelid and crustacean community composition in groundwater from the studied urban wells in Kraków, Poland. Points represent individual wells (well numbers correspond to Tables 1 and S1). Pearson correlation vectors with values >0.2 on at least one axis are overlaid.

The frequencies of annelids (19 %) and crustaceans (46 %) observed in this study fall within the broad range reported for other large European and North African cities, where annelids and crustaceans have been found in 7 %–58 % and 3 %–75 % of wells, respectively (Vejdovský, 1882; Jaworowski, 1893; Řehačkova, 1953; Vornatscher, 1972; Koch et al., 2021; El Moustaine et al., 2022; Dumnicka et al., 2025).

We found no clear pattern of seasonal variation in the composition of crustacean and annelid communities what can be partially caused by low number of taxa. This aligns with previous findings in the urban wells in Kraków showing no significant differences in total or group-specific abundances, although taxa richness and the Shannon–Wiener diversity index were significantly higher in autumn than in spring (Dumnicka et al., 2025). Seasonal dynamics in invertebrate communities in urban wells remain unexplored. Bozkurt (2023), for example, found only minor seasonal differences in copepods, cladocerans and rotifers in 29 wells in Kilis, southern Turkey, although these were not statistically tested.

The gamma diversity of crustaceans and annelids in Kraków wells was relatively high, with 19 species recorded, including six stygobionts, although some uncertainty remains to whether all juvenile Trichodrilus specimens represent true stygobiont species. These values apper higher than those reported for urban wells in other Central and Northwestern European cities (Moniez, 1888–1889; Jaworowski, 1893; Řehačkova, 1953; Hahn et al., 2013), where the number of recorded stygobitic species was generally low, ranging from zero in the historical survey in Kraków (Jaworowski, 1893) to five in Prague (Vejdovský, 1882).

The species accumulation curve based on our data did not reach saturation. The low mean species frequency (2.1 wells), with no significant differences between stygobionts and non-stygobionts, suggests that additional sampling would likely yield further species. Extrapolation metrics indicate, however, that 4 to 13 additional species might be detected, implying that the current sampling effort approached completeness.

Alpha diversity was relatively low, ranging from one to three species per well, with an average of 1.4 ± 0.7. Notably, the alpha diversity was significantly lower for the stygobitic species (on average <1 species) than for surface-dwelling species (on average 1 species). Similar alpha diversity (mean 1.3, range 1–2) for crustaceans and annelids has been historically reported in urban wells in Lviv, Ukraine as well as in Kraków (Jaworowski, 1893), while more diverse communities of these invertebrate groups have also been reported in wells in other cities. For instance, El Moustaine et al. (2022) documented alpha diversity ranging from 1 to 6 species (mean 2.8) in eight wells in Meknes, Morocco, although some taxa were identified only to genus or family level. Comparative analyses remain limited due to a paucity of detailed taxonomic studies in urban well fauna in Europe and the tendency of some to report only higher taxonomic groups (e.g., Cyclopoida, Amphipoda, Oligochaeta) (Koch et al., 2021).

Copepods were the most frequently found group in the Kraków wells, with six species identified, including Diacyclops gr. languidoides, previously recorded in Poland in caves, wells, and interstitial habitats (Kur et al., 2020; Pociecha et al., 2021). This taxon has also been occasionally recorded from lakes in Poland (Kur and Wojtasik, 2007) but due to its sporadic occurrence in surface inland waters, its predominantly subterranean distribution, and existing taxonomic uncertainties within this complex, Diacyclops gr. longuidoides from the Kraków well is treated here as a stygobitic species. Stoch (1995) highlighted the difficulties associated with classifying this species complex, arguing that such classification should take into account ecological factors, such as habitat heterogeneity, environmental stability, and biotic interactions, as well as evolutionary processes, including multiple colonization events and diversification through niche differentiation. Later, Stoch (2001) also pointed out that the importance of these factors in the formation of freshwater invertebrate communities – especially subterranean ones – remains poorly understood, and suggested that advances in copepod taxonomy would contribute to our our understanding of broader questions in theoretical biology. Moreover, the genus Diacyclops appears to be highly diversified in the underground waters of Romania, where several species of the D. languidoides group are yet to be described (Iepure at al., 2021).

Copepods are key components of groundwater fauna, often comprising true stygobionts and taxa adapted to subsurface habitats (Galassi et al., 2009). Previous surveys of Polish groundwater habitats have reported 51 copepod species, with only four true stygobionts (Karpowicz et al., 2021; Pociecha et al., 2021; Karpowicz and Smolska, 2024). In wells 37 species have been recorded (including three stygobionts), primarily Cyclopoida (30 species) plus one Calanoida and six Harpacticoida. Most non-stygobitic copepods in our study likely originated from surface waters in the Kraków area, as suggested by the presence of Acanthocyclops venustus and A. vernalis, known from local surface habitats (see Ślusarczyk, 2003; Kur, 2012; Pociecha and Bielańska-Grajner, 2015; Żurek, 2000 and Żurek et al., 2019 for surface water copepods in Kraków).

Despite the relatively high total number of ostracod species recorded in Polish groundwater environments (38 species, including nine stygobionts) and specifically from wells (22 species, including eight stygobionts), only three species were found in present study: one stygobiont (Typhlocypris cf. eremita) and two surface dwelling juvenile candonids. Typhlocypris eremita is a most common representative of the stygobitic genus Typhlocypris, with representatives found mainly in the interstitial habitats of alluvial aquifers, in the hyporheic zone along rivers and in cavernicolous habitats of central and south-eastern Europe (Namiotko and Danielopol, 2004; Namiotko et al., 2004, 2014). In Poland T. eremita is a most common stygobitic ostracod (Sywula, 1981; Pociecha et al., 2021), occasionally collected in surface waters connected to groundwater (Namiotko, 1990; Namiotko and Sywula, 1993).

Two additional crustacean stygobionts were recorded: the bathynellacean Bathynella natans and the amphipod Niphargus cf. tatrensis. The former has been found in one well and five interstitial sites in southern Poland (Sywula, 1989; Pociecha et al., 2021), while the latter is the most widespread Polish stygobiont amphipod, commonly found in caves, wells, and interstitial habitats (Dumnicka and Galas, 2017; Pociecha et al., 2021).

Subterranean waters in Poland are known to host 111 annelid species (Dumnicka et al., 2020), with Enchytraeidae being particularly diverse, including soil-dwelling or semi-aquatic species. In Kraków, surface water oligochaetes have been rarely studied (Szarski, 1947; Dumnicka, 2002), with Nais elinguis being the most common taxon, mainly in lotic habitats. Previous surveys found Enchytraeidae to be relatively rare in Polish wells, with more common Tubificidae and Naididae including several stygophiles (Dumnicka et al., 2020). Similarly, our study found relatively few annelid species. Beside semi-aquatic taxa, also occasional individuals of surface-dwelling genera Rhynchelmis and Aeolosoma, were unexpectedly observed in the wells in the Kraków centre. Stygobiont Trichodrilus spp. were found in four wells, potentially indicating higher water quality.

Despite low alpha diversity, beta diversity among wells was high – a pattern characteristic of groundwater ecosystems where total number of species most often is low (Hahn and Fuchs, 2009; Malard et al., 2009; Stoch and Galassi, 2010; Zagmajster et al., 2014; Hose et al., 2022). Crustaceans and annelids generally occurred allopatrically, forming four main community types. One type, dominated by Enchytraeus gr. buchholzi and observed in seven wells may reflect degraded conditions according to the German groundwater ecosystem status index (GESI) (Koch et al., 2021). Another type, dominated by Bathynella natans with Aeolosoma spp. which was observed in five studied wells may indicate transitional ecological conditions, while the third type dominated in four wells by Trichodrilus spp. suggest relatively unaffected conditions. The forth, more heterogeneous community, distinguished primarily by the surface copepods Acanthocyclops venustus and Paracyclops imminutus is difficult to interpret ecologically. This community occurred in old city center (wells 84–86 and 91) or in elevated area (well 69) with no direct connection to surface water. In conclusion, although species richness and abundances of annelids and crustaceans were relatively low and dominated by surface water taxa, the occurrence of six stygobitic species in 10 of 47 wells with crustaceans and/or annelids (or of 28 wells with species-level identifications) suggests that to of wells in Kraków may offer relatively good ecological conditions. Even in urban environments, groundwater fauna play a vital ecological role and may serve as bioindicators, reflecting environmental changes over multiple time scales. Accordingly, the development of a biomonitoring framework for subterranean waters, as proposed by Johns (2024), is warranted.

Although the fauna of urban wells in Central Europe is generally species-poor, studies of these habitats may help explain important questions, for example the pathways and timing of species migration from surface to underground waters or between isolated aquifers. Moreover, identifying sites that host the richest fauna and stygobiont populations may serve as a basis for establishing appropriate conservation.

This study reveals that despite the relatively low alpha diversity of annelids and crustaceans in urban wells of Kraków, their beta and gamma diversity indicate a heterogeneous and partially natural subterranean ecosystem. The occurrence of stygobitic species in a notable proportion of wells suggests that some groundwater habitats in the city retain ecological integrity. These findings highlight the importance of including urban groundwater fauna in biodiversity assessments and support the need for long-term biomonitoring systems to track environmental changes and protect subterranean ecosystems in urban areas.

All data are available in Table 1 in the paper. Chemical data are available from Dumnicka et al. (2025). Readers interested in other materials can request this information from the corresponding author.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-22-7961-2025-supplement.

E. D.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology (collection, analysis, and interpretation of data), formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, project administration; J. G.: investigation, methodology (collection, analysis of data), writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, project administration; T. N.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology (analysis and interpretation of data), formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing; A. P.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology (analysis, and interpretation of data), formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We are very much indebted to Mirosław Żelazny from the Institute of Geography and Spatial Management, Jagiellonian University, Kraków for allowing us to use the results of water chemical analyses. We also would like to thank the Management of the Kraków Water Company for sharing the list of wells existing in the Kraków city area.

This research was funded by subvention of Institute of Nature Conservation, Polish Academy of Sciences (E. D., J. G., A. P.) and partly by the University of Gdansk attributed to T. N.

This paper was edited by Pierre Amato and reviewed by Fabio Stoch and one anonymous referee.

Anderson, M. J., Gorley, R. N., and Clarke, K. R.: PERMANOVA+ for PRIMER: Guide to Software and Statistical Methods, PRIMER-E, Plymouth, UK, https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=19bb860e-6a20-42d4-a081-a1f62bc8dfa1 (last access: 9 December 2025), 2008.

Becher, J., Englisch, C., Griebler, C., and Bayer P.: Groundwater fauna downtown – drivers, impacts and implications for subsurface ecosystems in urban areas, J. Contam. Hydrol., 248, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2022.104021, 2022.

Becher, J., Griebler, C., Fuchs, A., Gaviria, S., Pfingstl, T., Eisendle, U., Duda, M., and Bayer P. B.: Groundwater fauna below the city of Munich and relationships to urbanization effects, in: 26th International Conference on Subterranean Biology 6th International Symposium on Anchialine Ecosystems, Book of Abstracts, Cagliari, Sardinia, Italy, 9–14 September 2024, edited by: Cialente, E., Tabilio Di Camillo, A., Di Lorenzo, T., and Lunghi, E., 77, https://www.abcdarkworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/26thICSB_6thISAE_Book-of-Abstract.pdf (last access: 9 December 2025), 2024.

Błędzki, L. A. and Rybak J. I.: Freshwater Crustacean Zooplankton of Europe: Cladocera & Copepoda (Calanoida, Cyclopoida) Key to Species Identification, with Notes on Ecology, Distribution, Methods and Introduction to Data Analysis, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29871-9, 2016.

Bozkurt, A.: Investigation of groundwater zooplankton fauna from water wells in Kilis Province from Türkiye, Nat. Engin. Sci., 8, 86–105, 2023.

Burri, N. M., Weatherl, R., Moeck, C., and Schirmer M.: A review of threats to groundwater quality in the Anthropocene, Sci. Total Environ., 684, 136–154, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.236, 2019.

Chappuis, P. A.: Die Fauna der unterirdischen Gewässer der Umgebung von Basel, Arch. Hydrobiol., 14, 1–88, 1924.

Chowaniec, J., Freiwald, P., Patorski, R., and Witek, K.: Kraków. In: Wody podziemne miast wojewódzkich Polski, Ed. Nowicki, 72–88, Warszawa, Polska: Informator Państwowej Służby Hydrogeologicznej, PGI, ISBN 978-83-7538-8, 2007 (in Polish).

Clarke, K. R. and Gorley R. N.: PRIMER v7: User Manual/Tutorial, PRIMER-E, Plymouth, UK, https://www.scribd.com/document/268811163/Getting-Started-With-PRIMER-7 (last access: 9 December 2025), 2015.

Dalmas, A.: Zoocenoses de puits artificiels en provence, Ann. Spéléol., 28, 517–522, 1973.

Dumnicka, E.: Upper Vistula River: Response of aquatic communities to pollution and impoundment. X. Oligochaete taxocens, Pol. J. Ecol., 50, 237–247, 2002.

Dumnicka, E. and Galas, J.: An overview of stygobiontic invertebrates of Poland based on published data, Subterranean Biology, 23, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.3897/subtbiol.23.11877, 2017.

Dumnicka, E., Galas, J., and Krodkiewska, M.: Patterns of benthic fauna distribution in wells: the role of anthropogenic impact and geology, Vadose Zone J., 16, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2016.07.0057, 2017.

Dumnicka, E., Galas, J., Krodkiewska, M., and Pociecha, A.: The diversity of annelids in subterranean waters: a case study from Poland, Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst., 421, 16, https://doi.org/10.1051/kmae/2020007, 2020.

Dumnicka, E., Galas, J., Krodkiewska, M., Pociecha, A., Żelazny, M., Biernacka, A., and Jelonkiewicz, Ł.: Ecohydrological conditions in municipal wells and patterns of invertebrate fauna distribution (Kraków, Poland), Ecohydrology, 18, https://doi.org/10.1002/eco.2757, 2025.

El Moustaine, R., Chahlaoui, A., Khaffou, M., Rour, E., and Boulal, M.: Groundwater quality and aquatic fauna of some wells and springs from Meknes area (Morocco), Geology, Ecology, and Landscapes, https://doi.org/10.1080/24749508.2022.2134636, 2022.

Englisch, C., Kaminsky, E., Steiner, C., Stumpp, C., Götzl, G., and Griebler, C.: Heat Below the City – Is Temperature a Key Driver in Urban Groundwater Ecosystems?, in: ARPHA Conference Abstracts, 5, e89677, Sofia, Bulgaria, Pensoft Publishers, https://doi.org/10.3897/aca.5.e89677, 2022.

Englisch, C., Kaminsky, E., Steiner, C., Buga-Nyeki, E., Stumpp, C., and Griebler C.: Life below the City of Vienna - Drivers of groundwater fauna distribution in an urban ecosystem, in: 26th International Conference on Subterranean Biology 6th International Symposium on Anchialine Ecosystems, Book of Abstracts, Cagliari, Sardinia, Italy, 9–14 September 2024, edited by: Cialente, E., Tabilio Di Camillo, A., Di Lorenzo, T., and Lunghi, E., 74, https://www.abcdarkworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/26thICSB_6thISAE_Book-of-Abstract.pdf (last access: 9 December 2025), 2024.

Ertl, M.: Jahreszeitliche Veränderungen der Brunnenorganismen im verhältnis zur oberflächlichen Verunreinigung der Brunnen, Biologica: Universitas Carolina, 3, 109–131, 1957 (in Czech with German Summary).

Galassi, D. M. P., Huys, R., and Reid, J. W.: Diversity, ecology and evolution of groundwater copepods, Freshw. Biol., 54, 691–708, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2009.02185.x, 2009.

Gradziński, M. and Gradziński, R.: Budowa Geologiczna, [Geology], in: Natural Environment of Krakow. Resources-Protection-Management, edited by: Baścik, M. and Degórska, B., Kraków, Poland, Institute of Geography and Spatial Management Jagiellonian University, 23–32, ISBN 978-83-64089-09-1, 2015 (in Polish with English Summary).

GWD: Directive 2006/118/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006 on the Protection of groundwater against pollution and deterioration, http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2006/118/oj (last access: 9 December 2025), 2006.

Hahn, H. J. and Fuchs, A.: Distribution patterns of groundwater communities across aquifer types in South-Western Germany, Freshw. Biol., 54, 848–860, 2009.

Hahn, H. J., Matzke, D., Kolberg, A., and Limberg, A. : Untersuchungen zur Fauna des Berliner Grundwassers – erste Ergebnisse, Brandenburg. Geowiss. Beitr., 20, 85–92, 2013.

Hammer, O., Harper, D. A. T., and Ryan, P. D.: Past: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis, Palaeontologia Electronica, 4, 1–9, 2001.

Hose, G. C., Chariton, A. A., Daam, M. A., Di Lorenzo, T., Galassi, D. M. P., Halse, S. A., Reboleira, A. S. P. S., Robertson, A. L., Schmidt, S. I., and Korbel, K. L.: Invertebrate traits, diversity and the vulnerability of groundwater ecosystems, Functional Ecology, 36, 2200–2214, 2022.

Hotèkpo, S. J., Namiotko, T., Lagnika, M., Ibikounle, M., Martin, P., Schon, I., and Martens, K.: Stygobitic Candonidae (Crustacea, Ostracoda) are potential environmental indicators of groundwater quality in tropical West Africa, Freshw. Biol., e70043, https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.70043, 2025.

Iepure, S., Bădăluţă, C. A., and Moldovan, O. T.: An annotated checklist of groundwater Cyclopoida and Harpacticoida (Crustacea, Copepoda) from Romania with notes on their distribution and ecology, Subterranean Biology, 41, 87–108, https://doi.org/10.3897/subtbiol.41.72542, 2021.

Jaworowski, A.: Fauna studzienna miast Krakowa i Lwowa [Fauna of Wells in Kraków and Lwów Cities], Spraw. Kom. Fizyograf., AU w Krakowie 28, 29–48, 1893 (in Polish).

Johns, T.: Developing the first national monitoring network for groundwater ecology in England, in: 26th International Conference on Subterranean Biology 6th International Symposium on Anchialine Ecosystems, Book of Abstracts, Cagliari, Sardinia, Italy, 9–14 September 2024, edited by: Cialente, E., Tabilio Di Camillo, A., Di Lorenzo, T., and Lunghi, E., 6, https://www.abcdarkworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/26thICSB_6thISAE_Book-of-Abstract.pdf (last access: 9 December 2025), 2024.

Karpowicz, M. and Smolska, S.: Ephemeral Puddles – Potential Sites for Feeding and Reproduction of Hyporheic Copepoda, Water, 16, 1068, https://doi.org/10.3390/w16071068, 2024.

Karpowicz, M., Smolska, S., Świsłocka, M., and Moroz, J.: First insight into groundwater copepods of the Polish lowland, Water, 13, 2086, https://doi.org/10.3390/w13152086, 2021.

Kleczkowski, A. S., Czop, M., Motyka, J., and Rajchel L. Z.: Influence of the geogenic and anthropogenic factors on the groundwater chemistry in Krakow (south Poland), Geologia, 35, 117–129, 2009.

Kim, H. H.: Urban Heat Island, Internat. J. Remote Sensing, 13, 2319–2336, https://doi.org/10.1080/01431169208904271, 1992.

Koch, F., Menberg, K., Schweikert, S., Spengler, C., Hahn, H. J., and Blum, P.: Groundwater fauna in an urban area – natural or affected?, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 25, 3053–3070, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-25-3053-2021, 2021.

Kur, J.: Zmienność populacyjna widłonogów Copepoda w wodach podziemnych Południowej Polski [Population variability of copepods in subterranean waters of Southern Poland], Praca doktorska, IOP, Institute of Nature Conservation, Polish Academy of Sciences, division X, part a, item 27009, 127 pp., 2012 (in Polish).

Kur, J. and Wojtasik, B.: Widłonogi Cyclopoida wybranych jezior zlewni górnej Raduni. Jeziora Kaszubskiego Parku Krajobrazowego, 145–163, ISBN 978-83-910381-6-1, 2007 (in Polish).

Kur, J., Mioduchowska, M., and Kilikowska, A.: Distribution of cyclopoid copepods in different subterranean habitats (southern Poland), Oceanological and Hydrobiological Studies, 49, 255–266, 2020.

Malard, F., Boutin, C., Camacho, A. I., Ferreira, D., Michel, G., Sket, B., and Stoch, F.: Diversity patterns of stygobiotic crustaceans across multiple spatial scales in Europe, Freshw. Biol., 54, 756–776, 2009.

Marmonier, P., Galassi, D. M. P., Korbel, K., Close, M., Datry, T., and Karwautz, C.: Groundwater biodiversity and constraints to biological distribution, Chapter 5, in: Groundwater Ecology and Evolution, edited by: Malard, F., Griebler, C., and Rétaux, S., Academic Press, 113–140, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819119-4.00003-2, 2023.

Meisch, C.: Freshwater Ostracoda of Western and Central Europe, Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg Berlin, 522 pp., ISBN 9783827410016, 2000.

Meyer, L., Becher, J., Griebler, C., Herrmann, M., Küsel, M., and Bayer, P.: Biodiversity patterns in the urban groundwater of Halle (Saale), Germany, in: 26th International Conference on Subterranean Biology 6th International Symposium on Anchialine Ecosystems, Book of Abstracts, Cagliari, Sardinia, Italy, 9–14 September 2024, edited by: Cialente, E., Tabilio Di Camillo, A., Di Lorenzo, T., and Lunghi, E., 39, https://www.abcdarkworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/26thICSB_6thISAE_Book-of-Abstract.pdf (last access: 9 December 2025), 2024.

Moniez, R.: Faune des eaux souterraines du Département du Nord et en particulier de la ville de Lille, Rev. Biol. Nord France, 3–4, 81–94, 142–153, 170–182, 241–262, 1888–1889.

Namiotko, T.: Freshwater Ostracoda (Crustacea) of Żuławy Wiślane (Vistula Fen Country, Northern Poland), Acta Zool. Cracov., 33, 459–484, 1990.

Namiotko, T. and Sywula, T.: Crustacean assemblages from the irrigation ditches near Szymankowo (Vistula Delta), Zesz. Nauk. UG, Biologia, 10, 159–162, 1993 (in Polish with English abstract).

Namiotko, T. and Danielopol D. L.: Review of the eremita species-group of the genus Pseudocandona Kaufmann (Ostracoda, Crustacea), with the description of a new species, Revista Española de Micropaleontologia, 36, 117–134, 2004.

Namiotko, T., Danielopol, D. L., and Rađa, T.: Pseudocandona sywulai sp. nov., a new stygobitic ostracode (Ostracoda, Candonidae) from Croatia, Crustaceana, 77, 311–331, 2004.

Namiotko, T., Danielopol, D. L., Meisch, C., Gross, M., and Mori, N.: Redefinition of the genus Typhlocypris Vejdovský, 1882 (Ostracoda, Candonidae), Crustaceana, 87, 952–984, 2014.

Pociecha, A. and Bielańska-Grajner, I.: Large-scale assessment of planktonic organisms biodiversity in artificial water reservoirs in Poland, Institute of Nature Conservation Polish Academy of Sciences, 272 pp., ISBN 978-83-61191-80-3, 2015.

Pociecha, A., Karpowicz, M., Namiotko, T., Dumnicka, E., and Galas, J.: Diversity of groundwater crustaceans in wells in various geologic formations of southern Poland, Water, 13, 2193, doi.org10.2290/w13162193, 2021.

Rajchel, L.: Wody mineralne i akratopegi Krakowa (Mineral waters and akratopegs in Kraków), Przegląd Geologiczny, 46, 1139–1145, 1998 (in Polish).

Řehačkova, V.: Well-Water Organisms of Prague, Rozpr. Českoslov. Akad. Věd, 63, 1–35, 1953 (in Czech with English Summary).

Rutkowski, J.: Szczegółowa Mapa Geologiczna Polski 1:50 000, arkusz Kraków (973) (Detailed Geological Map of Poland, 1:50 000, Sheet Kraków), Warszawa, Poland, Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny, https://bazadata.pgi.gov.pl/data/smgp/arkusze_txt/smgp0973.pdf (last access: 10 December 2025), 1989 (in Polish).

Skalski, A. W.: The hypogeous gammarids in Poland (Crustacea, Amphipoda, Gammaridae), Acta Hydrobiol., 12, 431–437, 1970.

Skalski, A. W.: Underground Amphipoda in Poland, V Rocznik Muzeum Okręgowego w Częstochowie, Przyroda 2, 61–83, 1981 (in Polish with English summary).

Stoch, F.: Diversity in groundwaters, or: why are there so many, Mémoires de Biospéologie, 22, 139–160, 1995.

Stoch, F.: How many species of Diacyclops? New taxonomic characters and species richness in a freshwater cyclopid genus (Copepoda, Cyclopoida), Hydrobiologia, 453, 525–531, 2001.

Stoch, F. and Galassi, D. M. P.: Stygobiotic crustacean species richness: A question of numbers, a matter of scale, Hydrobiologia, 653, 217–234, 2010.

Sywula, T.: Ostracoda of underground water in Poland, V Rocznik Muzeum Okręgowego w Częstochowie, Przyroda 2, 89–96, 1981 (in Polish with English summary).

Sywula, T.: Bathynella natans Vejdovský, 1882 and Proasellus slavus (Remy, 1948), subterranean crustaceans new for Poland, Przeg. Zool., 33, 77–82, 1989 (in Polish with English summary).

Szarski, H.: Oligochaeta limicola found in the neighbourhood of Kraków in the year 1942, Kosmos, ser. A, 65, 150–158, 1947 (in Polish with English summary).

Ślusarczyk, A.: Limnological study of a lake formed in limestone quarry (Kraków, Poland), I. Zooplankton community, Pol. J. Environ. Stud., 12, 489–493, 2003.

Timm, T.: A guide to the freshwater Oligochaeta and Polychaeta of Northern and Central Europe, Lauterbornia, 66, 1–235, 2009.

Vejdovský, F.: Thierische Organismen der Brunnenwässer von Prag, Selbstverlag, Prag, 70 pp. mit 8 Tafeln, 1882.

Vornatscher, J.: Die Tierwelt des Grundwassers – Leben im Dunkeln, in: Die Naturgeschichte Wiens, Band 2, Naturnahe Landschaften, Pflanzen- Und Tierwelt, edited by: Starmühler, F. and Ehendorfer, F., 659–674, Jugend und Volk, Wien/München, ISBN 3-8141-6113-9, 1972.

WFD: Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy, http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/60/oj (last access: 9 December 2025), 2000.

Zagmajster, M., Eme, D., Fišer, C., Galassi, D., Marmonier, P., Stoch, F., Cornu, J. F., and Malard, F.: Geographic variation in range size and beta diversity of groundwater crustaceans: insights from habitats with low thermal seasonality, Global Ecol. Biogeogr., 23, 1135–1145, https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12200, 2014.

Żurek, R.: Diversity of flora and fauna in running waters of the Province of Cracow (southern Poland) in relation to water quality, 4. Zooseston, Acta Hydrobiol., 42, 331–345, 2000.

Żurek, R., Baś, G., Dumnicka, E., Gołąb, M. J., Profus, P., Szarek-Gwiazda, E., Walusiak, E., Ciężak, K.: Płaszów pond in Kraków – biocenoses, Chrońmy Przyr. Ojcz., 75, 345–362, 2019 (in Polish with English summary).