the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Transporter gene family evolution in ectomycorrhizal fungi in relation to mineral weathering capabilities

Petra Fransson

Roger Finlay

Marisol Sánchez-García

Ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi play an important role in biological mineral weathering and show increased mycelial base cation content when grown with minerals. However, the mechanisms underlying base cation mobilisation and uptake remain poorly understood. With a focus on the mineral weathering ECM genus Suillus, we investigated evolutionary expansions and contractions of base cation transporter gene families across a phylogeny of 108 Agaricomycetes species. We also quantified base cation uptake by ECM and saprotrophic fungal species, including Suillus, under pure culture conditions with and without mineral additions, and assessed correlations between uptake and base cation transporter family copy numbers. We hypothesised that (1) greater base cation uptake depends on higher gene copy numbers of base cation transporter families resulting from evolutionary expansions, (2) weathering of mineral additions enhances base cation uptake by Suillus, and (3) Suillus species exhibit greater base cation uptake in mineral amended conditions compared to other fungi. We identified 25 base cation transporter families with significant expansions and contractions across the phylogeny, and many within Suillus, underscoring the ecological importance of base cation transport in this genus. Suillus and Piloderma, another ECM genus, showed higher mycelial cation concentrations when grown with minerals compared to nutrient limited conditions, confirming mineral-derived uptake. Nine significant positive correlations were detected between base cation uptake and base cation transporter gene family copy numbers in mineral amended conditions. This indicates that in some cases, such as for the Mg2+ transporter-E family, expansions in transporter families likely support enhanced base cation acquisition. Overall, these findings suggest that Suillus species have undergone rapid evolutionary changes in base cation transporter family copy numbers, potentially linked to their mineral weathering abilities. Further studies integrating transcriptional regulation of transporter genes will be essential to elucidate the mechanisms governing base cation mobilisation and uptake in Suillus and other ECM fungi.

- Article

(2131 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(3722 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

In boreal forests biological mineral weathering, the disintegration and dissolution of minerals caused by biota, is driven by plant-associated ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi. These ECM fungi form the dominant type of symbiosis, primarily with trees of the Pinaceae family (Smith and Read, 2008), and play key roles in plant nutrient acquisition, carbon (C) partitioning and sequestration, and biogeochemical cycles, by exchanging nutrients mobilised by ECM fungi from the soil with photosynthetically derived C from the host plant (Clemmensen et al., 2013; Genre et al., 2020; Van Der Heijden et al., 2015). Base cations – such as calcium (Ca2+), iron (Fe2+ or Fe3+), potassium (K+), magnesium (Mg2+) and sodium (Na+) – and phosphorus (P), and nitrogen (N), are primarily mobilised by mineral weathering and N mobilisation via decomposition of organic matter, respectively (Finlay et al., 2020; Hoffland et al., 2004; Tunlid et al., 2022). In stratified boreal forest soils, mineral weathering and N mobilisation occur primarily in the lower mineral B horizon and upper organic O horizon, respectively (van Breemen et al., 2000; Hobbie and Horton, 2007; Jongmans et al., 1997; Mahmood et al., 2024). These processes have been shown to influence each other and ECM fungi play a large role in their integration. It was also shown that adequate plant N acquisition is essential for sufficient C allocation to ECM fungi involved in mineral weathering (Mahmood et al., 2024). Although organic matter depletion was shown to negatively impact mineral weathering rates, N mobilisation and plant growth, forestry practices are intensifying and there is increasing demand for organic matter for bioenergy (Akselsson et al., 2007, 2019; Klaminder et al., 2011; Moldan et al., 2017). These practices are suggested to be unsustainable and it is therefore essential to improve our understanding of ECM-mediated mineral weathering and base cation uptake, including which ECM species play key roles and how these processes are regulated to aid the development of more sustainable forestry practices.

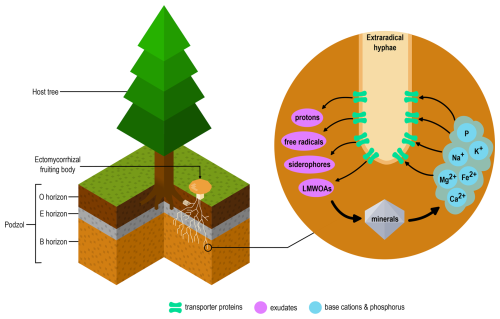

To weather minerals, ECM fungi must colonise mineral rich soils and utilise plant allocated C to generate mechanical pressure and produce low molecular weight organic acids (LMWOAs), free radicals, protons and siderophores, which collectively facilitate mineral breakdown and the mobilisation of base cations (Fig. 1) (Finlay et al., 2020; Fomina et al., 2010; Schmalenberger et al., 2015). Several ECM species have been identified to perform mineral weathering including Paxillus involutus (Bonneville et al., 2009, 2016; Gazze et al., 2012; van Scholl et al., 2006), Pisolithus tinctorius (Balogh-Brunstad et al., 2008b; Paris et al., 1995, 1996), a number of Piloderma species (Glowa et al., 2003; van Scholl et al., 2006), as well as a number of Suillus species which are commonly found in the B horizon in boreal forests (Lofgren et al., 2024; Mahmood et al., 2024; Marupakula et al., 2021). In the presence of minerals, several Suillus species have been observed to increase production and exudation of LMWOAs (Adeleke et al., 2012; Olsson and Wallander, 1998; Wallander and Wickman, 1999), and take up base cations such as K+, Mg2+ and Fe2+ or Fe3+ (Balogh-Brunstad et al., 2008a; Fahad et al., 2016; Mahmood et al., 2024). These studies, however, primarily rely on abundance data and chemical analyses of ECM fungal biomass, plant biomass, or growth medium of experimental systems without specifically investigating the genetic basis of how these species perform mineral weathering and base cation uptake, nor the mechanisms involved or their regulation.

Figure 1In boreal forest podzols, ECM fungi, in symbiosis with the fine roots of host trees (left), can exude LMWOAs, siderophores, free radicals and protons which can weather minerals via their extraradical hyphae, and mobilise base cations and P (right). Both the exudation of weathering agents, and the uptake of base cations and P occurs through transporter proteins.

Regulation of base cation uptake through transporter proteins can take place at multiple stages, from the genomic to the post-translational stage (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2024). Although studies on the regulation of base cation transporter genes are limited, transcriptomic analyses have revealed that K+ transporter genes are upregulated during mineral weathering in Hebeloma cylindrosporum (Corratgé et al., 2007; Garcia et al., 2014), Amanita pantherina (Sun et al., 2019) and Paxillus involutus (Pinzari et al., 2022). On the genomic level, one mechanism of regulating transporter protein expression is differences in the number of copies of a protein encoding gene. This can occur within species or populations and has been shown to drive genome evolution and environmental adaptation (Steenwyk and Rokas, 2017; Tralamazza et al., 2024). Differences in copy number can also occur between species, and Wapinski et al. (2007) found that genes related to growth and maintenance show little duplication or loss in copy number, but genes related to stress and environment interactions show much greater fluctuations in copy number. Genes encoding transporter proteins belong to the latter group, thus, it is reasonable to expect lifestyle and niche dependent fluctuations in copy number as a form of adaptation and regulation of transport. Fungal comparative genomic studies have highlighted the importance of gene family copy number in the emergence of the ECM lifestyle from saprotrophic ancestors (Kohler et al., 2015; Miyauchi et al., 2020). Gene family copy numbers of plant cell wall degrading enzymes, important in fungal-mediated decomposition of plant material, have been observed to be markedly reduced in ECM fungi compared to their saprotrophic ancestors, and gene copy numbers of symbiosis-induced secreted proteins have been shown to expand in ECM fungi (Miyauchi et al., 2020). Currently however, there are no studies addressing the evolution of base cation transporter genes involved in ECM-mediated mineral weathering or how they might contribute to base cation uptake regulation.

Here, we investigated the evolution of base cation transporter gene families in the Agaricomycotina, with a particular focus on the genus Suillus. We hypothesised that (1) greater base cation uptake is dependent on base cation transporter gene family copy numbers that result from evolutionary expansions, (2) mineral weathering results in base cation uptake by Suillus growing in pure culture with mineral additions, and (3) base cation uptake by members of the genus Suillus, frequently reported to perform mineral weathering, will be greater when growing in pure culture with mineral additions compared to other fungal species. A correlation between base cation uptake and base cation transporter gene family copy numbers would provide a mechanistic explanation for mineral weathering. Using bioinformatics we explored evolutionary expansions and contractions in base cation transporter gene families, and using experimental approaches we determined base cation uptake by five species of Suillus (S. bovinus, S. granulatus, S. grevillei, S. luteus and S. variegatus), six Piloderma isolates, and two saprotrophic fungi, Coniophora puteana and Serpula lacrymans, that were grown in pure culture with and without mineral additions. This study aims to elucidate the evolutionary patterns of base cation transporter genes and to explore the significance of their copy numbers in relation to mineral weathering and base cation uptake by ECM fungi, with a particular focus on the genus Suillus.

2.1 Bioinformatics

Bioinformatic analyses were performed to investigate the occurrence of evolutionary expansions within base cation transporter gene families in mineral-weathering ECM species, particularly those belonging to genus Suillus. This study also examined the relationship between gene copy number and mineral weathering capacity. To this end, a phylogeny of Agaricomycotina taxa was constructed. Evolutionary expansions and contractions of all transporter gene families, including those associated with base cation transport, were analysed to assess copy number variation across the phylogeny. Additionally, transporter gene families identified as particularly relevant in our analyses were examined in greater detail.

2.1.1 Agaricomycotina phylogeny

A phylogeny of 108 Agaricomycotina species was inferred using publicly available genome data from JGI MycoCosm (Grigoriev et al., 2014, https://mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov/mycocosm/species-tree/tree;aY7X8o?organism=agaricomycotina, last access: 20 June 2022) (Table S1 in the Supplement), with Tremella mesenterica (Tremellomycetes) and Dacryopinax primogenitus (Dacrymycetes) as outgroups. Orthogroups were identified from amino acid sequences with OrthoMCL v2.0.9 (Chen et al., 2006) with the settings percentMatchCutoff=50 and evalueExponentCutoff=-5. Single copy orthogroups present in at least 50 % of the taxa were chosen for the subsequent analyses. Multiple sequence alignment was done with MAFFT v7.407 (Katoh et al., 2005) using the auto settings, and poorly aligned regions were removed with TrimAL v1.4.1 (Capella-Gutiérrez et al., 2009) with a gap threshold of -gt 0.1. Individual gene alignments were concatenated with genestitcher v3 (Ballesterus, 2015), and a maximum likelihood phylogeny was inferred with IQ-TREE v2 (Nguyen et al., 2015) using the MFP+MERGE arguments to select the best-fit substitution model using ModelFinder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017), with 1000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates (Hoang et al., 2018).

2.1.2 Molecular dating

The resulting phylogenetic tree was time-calibrated with r8s v1.81 (Sanderson, 2003) using the penalised likelihood method and POWELL optimisation. A smoothing parameter of 0.01 was selected based on cross-validation performance. The root of Agaricomycotina was fixed to 436×106 years ago (MYA), the Suillaceae node was calibrated with a suilloid ectomycorrhizal fungi fossil (∼50–100 MYA) (LePage et al., 1997), and the Agaricales node was calibrated with the fossil Palaeoagaricites antiquus (∼105–210 MYA) (Poinar and Buckley, 2007). The resulting ultrametric tree was visualised and edited using inkscape (Inkscape Project, 2022).

2.1.3 Analysis of transporter gene family evolution

Copy number data for 173 transporter gene families present in the phylogeny and annotated according to the Transporter Classification Database (TCDB) system (Saier, 2006; Saier et al., 2009, 2014, 2016, 2021), were downloaded from JGI MycoCosm (Grigoriev et al., 2014; https://mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov/mycocosm/species-tree/tree;aY7X8o?organism=agaricomycotina, last access: 20 June 2022) (Table S2 in the Supplement). Transporter gene families were categorised as either associated or non-associated with base cation transport, with both groups included in the analysis to enable comparative evaluation of base cation transporter gene evolution. In addition, transporter gene families potentially undergoing rapid evolution were carefully examined, as such evolutionary dynamics, combined with an increased number of base cation transporter gene copies, may suggest enhanced mineral weathering capabilities. Relationships between transporter gene family copy numbers and fungal taxa were analysed and visualised using principal component analysis (PCA) on count data (Table S3 in the Supplement) using CANOCO 5.10 (Microcomputer Power, Ithaca, NY, USA; ter Braak and Smilauer, 2012). Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to test the influence of taxa, transporter gene family, and their interaction on transporter gene family copy number and Tukeys HSD was used for post hoc pairwise comparisons between copy numbers of transporter gene families in R using AICcmodavg (Mazerolle, 2023), emmeans (Lenth, 2024), multcomp, and multcompView (Hothorn et al., 2008).

The same data was used to estimate gene family evolution of transporters across the Agaricomycotina phylogeny using CAFE5 v5.1 (Mendes et al., 2020). This approach facilitated the comparison of changes in transporter gene family copy number between multiple lineages, enabling evaluation of whether these changes were isolated to Suillus or more broadly distributed. Rapidly evolving gene families were identified as those that have a significantly (p<0.05) higher rate of evolution than the mean rate. This rate is inferred from the numbers of expansions (gains) and contractions (losses). Due to the birth-death model employed by CAFE5, transporter gene families with zero gene copies at the root were excluded, reducing the analysed transporter gene families from 173 to 114. CAFE5 was unable to run when within-family size variation exceeded 80 copy numbers, so transporter gene family copy numbers were scaled to values of 0–80 and rounded up to the nearest whole number in R v4.3.2 (R Core Team, 2023), using the “Tidyverse” suite v2.0.0 (Wickham et al., 2019) and scales (Wickham et al., 2024). This dataset is referred to as the “full” dataset and although the values are scaled, it remains valuable for observing expansions and contractions across the entire Agaricomycotina phylogeny.

CAFE5 was also run with true count values of copy numbers and a reduced phylogeny of 28 taxa to account for any error introduced by the scaling, and to allow for the observation of expansions and contractions calculated with true copy number values in key species of interest. This dataset is referred to as the “partial family” dataset and included 126 transporter gene families in the CAFE5 analyses. The 28 selected taxa included all Suillus species known for their mineral weathering ability and occurrence in the mineral B horizon of boreal forest soils, as well as all Piloderma species inhabiting both the organic and mineral horizons of boreal forests. Additionally, two saprotrophic fungi, Coniophora puteana and Serpula lacrymans, were included to facilitate comparison between the ECM and saprotrophic lifestyle. These taxa were extracted from the original Agaricomycotina tree using R and the packages Geiger (Harmon et al., 2008) and ape v5.8 (Paradis and Schliep, 2019). Copy numbers of subfamilies of significantly expanding and/or contracting transporter gene superfamilies in the partial family dataset were also run with the reduced phylogeny of 28 taxa in CAFE5. This dataset is referred to as the “partial subfamily” dataset, with 51 transporter gene families included in CAFE5 analyses (Table S4 in the Supplement). All datasets were filtered in to include only significant expansions and contractions of transporter gene families, using the python script CafeMiner (EdoardoPiombo, 2023). Trees were visualised using CafePlotter (moshi4, 2023).

2.1.4 The Mg2+ transporter-E (MgtE) family phylogeny

Our CAFE5 results and subsequent correlations between base cations concentrations and base cation transporter gene family copy numbers, prompted further investigation of the Mg2+ transporter-E (MgtE) gene family (TCDB IC 1.A.26). Magnesium is a vital base cation involved in photosynthesis (Black et al., 2007), enzymatic activity (Bose et al., 2011), and has been shown to be mobilised and taken up by ECM fungi from mineral sources (Fahad et al., 2016; Mahmood et al., 2024). To explore the evolution of this gene family, a phylogenetic tree of all MgtE family amino acid sequences present in the 28 taxa of the partial family dataset was constructed. Sequences were extracted from proteomes using SAMTOOLS (Danecek et al., 2021), and the tree was reconstructed using the methods in Sect. 2.1.1 and visualised in R using ggtree (Wang et al., 2020; Yu, 2020; Yu et al., 2017).

2.2 Base cation uptake in pure culture

The ECM genus Suillus has been reported to possess mineral weathering capabilities and inhabit the mineral horizon in boreal forest soils, and was therefore studied in greater depth. Isolates of Suillus, and another ECM genus Piloderma, which inhabits both the organic and mineral soil horizons (Mahmood et al., 2024; Marupakula et al., 2021), and two saprotrophic fungi, Coniophora puteana and Serpula lacrymans, were included to compare between ECM and saprotrophic lifestyles. All isolates were grown in pure culture axenic systems with and without mineral additions to determine base cation uptake during mineral weathering.

2.2.1 Fungal isolates

A total of 23 fungal isolates, covering 11 species and two isolates identified to genus level, were used in the study (Table S5 in the Supplement). Fourteen Suillus isolates (S. bovinus [4], S. granulatus [3], S. grevillei [1], S. luteus [3], S. variegatus [3]) were isolated in summer and autumn of 2022 from morphologically identified fruitbodies collected in Central and Southern Sweden. Six Piloderma isolates (P. byssinum, P. aff. fallax, P. olivaceum, P. sphaerosporum, Piloderma sp. 1 and Piloderma sp. 2) were obtained from the culture collection maintained at the Department of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology, SLU. Two saprotrophic brown-rot species, Coniophora puteana and Serpula lacrymans (provided by Geoffry Daniel, Department of Forest Biomaterials and Technology, Wood Science, SLU). Prior to the experiment, all isolates were grown on Modified Melin-Norkrans (MMN) media (Marx, 1969) for 12 weeks (ECM) and 5 weeks (saprotrophs).

2.2.2 Experimental conditions

To measure base cation uptake during mineral weathering, fungal isolates were grown in 9 cm Petri dish closed axenic systems with and without mineral additions, as previously described by Fahad et al. (2016). Granite and gabbro, which are common in Swedish bedrock and differ in weathering rates, were selected as mineral sources (Bazilevskaya et al., 2013; Fritz, 1988; Holtstam et al., 2004). Granite, which weathers more slowly, is a complex of K feldspar, muscovite mica, and quartz, while gabbro, which weathers more quickly, is a complex of feldspar, amphibole, pyroxene and olivine, all of which contain essential base cations (Goldich, 1938). Rock material (provided by Swerock AB, Ängelholm, Sweden) was pulverised and sieved under flowing deionised water to retain a size fraction of 63–250 µm to maximise surface area and avoid finer fractions to ensure fungi had to actively weather minerals. Rock particles were sonicated for 10 min and sieved again to dislodge and remove residual debris. It was then transferred to a 1 L cylinder with small holes at the base and flushed continuously with deionised water for 3 d to remove loosely bound ions.

For each isolate two treatments, granite and gabbro, were prepared, with 30 replicates each. Plates were layered with 20 mL of limited media, containing (NH4)2HPO4 0.22 g L−1, thiamine-HCl 100 mg L−1, glucose 5 g L−1, malt extract 5 g L−1 and agar 12 g L−1, followed by a 5 mL layer of limited media amended with 20 g L−1 granite or gabbro. Media was adjusted to pH 5.5 (Fahad et al., 2016). A sterile cellophane sheet, rinsed in deionised water and autoclaved, was placed on each plate to prevent mycelial growth into the agar and to aid when harvesting, whilst allowing the transfer of soluble compounds.

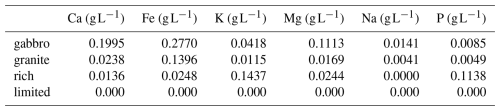

Two control treatments, limited and rich, each with 30 replicates per isolate were included. The limited control, identical to the limited media described above, served as a baseline with minimal nutrients. The rich control supplied all essential nutrients in readily available forms and contained CaCl2.2H2O 0.05 g L−1, NaCl 0.025 g L−1, MgSO4.7H2O 0.15 g L−1, (NH4)2HPO4 0.22 g L−1, KH2PO4 0.5 g L−1, FeCl3.6H2O 0.012 g L−1, thiamine-HCl 100 mg L−1, glucose 5 g L−1, malt extract 5 g L−1 and agar 12 g L−1. This allowed comparison between treatments where mineral weathering is required to access nutrients, and those in which base cations are readily available. Both control treatments were adjusted to pH 5.5 and covered with a sterile cellophane sheet. Relative concentrations of Ca, Fe, K, Mg, Na and P in each treatment are shown in Table 1.

2.2.3 Elemental analyses and statistics

Biomass samples were sent to the James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen, UK for elemental analyses. C and N analysis (Mettler MT5 Microbalance, Mettler-Toledo GmbH, Laboratory & Weighing Technologies, Greifensee, Switzerland and Thermo Finnigan Elemental Analyser FlashEA 1112 Series, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA), nitric acid microwave digestion (PerkinElmer Titan MPS Microwave Sample Preparation System, PerkinElmer, Massachusetts, USA) and ICP-EOS analysis (AVIO 500 ICP-OES, PerkinElmer, Massachusetts, USA) of Ca, Fe, K, Mg, Na and P was conducted on fungal biomass, cellophane, gabbro and granite.

Individual biomass per plate and elemental concentrations from pooled samples were used for statistical analysis in R v4.3.2 (R Core Team, 2023), with data processing and visualisation performed using the “Tidyverse” suite v2.0.0 (Wickham et al., 2019). Carbon and N measurements were used to calculate C:N ratios. Linear models were used to perform ANOVA for each element, biomass, and C:N ratio to assess the effects of isolate (or species in the case of C:N ratio), treatment, and their interactive effect on individual response variables. Post hoc comparisons were conducted using “emmeans” v1.10.4 (Lenth, 2024), with compact letter displays generated using “multcomp” v1.4-26 (Hothorn et al., 2008). Tukey's HSD was used for pairwise comparisons between treatments within each isolate for elemental concentration, and between treatments within each species and between species within each treatment for biomass and C:N ratio. Weathering was defined as a significantly higher element concentration in gabbro and/or granite treatments compared to the limited treatment.

Serpula lacrymans and C. puteana were excluded from biomass analyses based on individual plates due to difficulties harvesting complete biomass. The following isolates and treatments included fewer than three replicates for elemental analyses due to a lack of biomass; P. byssinum and S. lacrymans all treatments (1 replicate), isolates Sl2 and Sl3 limited treatment (1 replicate), and Sl3 gabbro treatment (2 replicates).

To evaluate whether Suillus isolates exhibited greater base cation uptake when growing with mineral additions than other fungal isolates, linear models were fitted to estimate the ratio of mycelial elemental concentrations in gabbro and granite treatments relative to the limited treatment, with isolate and treatment as explanatory factors. Analyses were conducted using “emmeans” v1.10.4 (Lenth, 2024). Ratios were calculated from the means of all replicates per isolate per treatment, yielding one ratio per comparison. Ratio means are reported with 95 % confidence intervals, based on model uncertainty and pooled variance across isolates. Ratios with non-overlapping confidence intervals were considered significantly different.

Correlations between base cation transporter gene family copy numbers and mean mycelial base cation and P concentration for all isolates in each treatment were tested using Pearson's correlation. Analyses were restricted to base cation transporter gene families which were both identified as significantly expanding or contracting in all CAFE5 analyses, and associated with the uptake of Ca2+, Fe2+ or Fe3+, K+, Mg2+, Na+, or P. This was determined using the TCDB substrate search tool (Saier Lab Bioinformatics Group, 2023). Correlations were only performed between mycelial base cation concentrations and transporter gene families that transported the corresponding base cation. Species lacking transporter family copy number data were excluded (S. granulatus, S. grevillei, P. aff. fallax, Piloderma sp. 1 and Piloderma sp. 2).

3.1 Phylogenetic Analyses

3.1.1 Agaricomycotina phylogeny

The phylogenetic inference of 108 Agaricomycotina species was performed using 152 single copy orthologs that were present in at least 50 % of the taxa, which after concatenation resulted in a supermatrix with 54 895 amino acids. Most nodes were recovered with a bootstrap value of 100 (Fig. S1 in the Supplement).

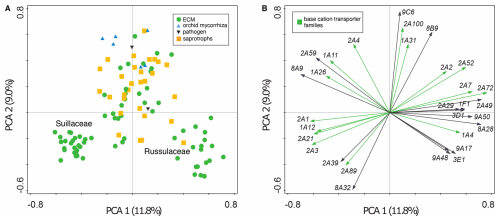

3.1.2 Transporter gene family copy numbers of 108 Agaricomycotina taxa

Within the Agaricomycotina, we identified significantly (p<0.05) higher gene copy numbers of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS; TCDB ID 2.A.1), Mg2+ transporter-E (MgtE; TCDB ID 1.A.26), ATP-binding cassette (ABC; TCDB ID 3.A.1), peroxisomal protein importer (PPI; TCDB ID 3.A.20) and mitochondrial carrier (MC; TCDB ID 2.A.29) gene families compared to other transporter gene families (Fig. S2 in the Supplement). Of these, the MFS, MgtE, ABC and MC gene families are involved in base cation transport. Visualisation of transporter gene family copy numbers (Table S3) by PCA showed a clear clustering of the families Suillaceae and Russulaceae which are distinct from each other and all other taxa (Fig. 2a). Among the 30 transporter gene families with the highest contribution to the ordination, 18 are base cation transporter gene families (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2Variation in transporter gene family composition in 108 Agaricomycotina taxa, based on Principle Component Analysis of copy numbers of 173 transporter gene families (Table S3) and visualised by (a) sample and (b) species plots showing the 30 transporter gene families with the greatest contribution to the ordination of taxa. Nutritional lifestyle (a) is coded by shape and colour of sample points, and in (b) base cation transporter families are indicated in green. The first two axes together explained 20.8 % of total variation.

3.1.3 Transporter gene family evolution

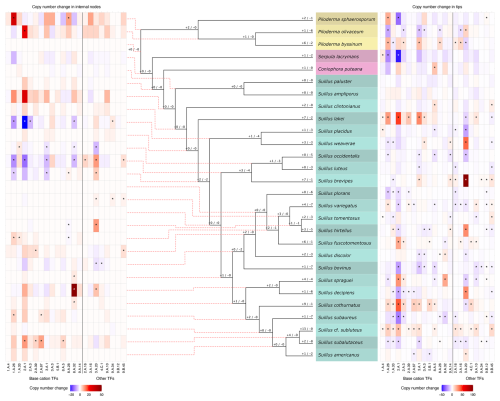

Thirteen out of 114, and 22 out of 126 transporter gene families in the full and partial datasets, respectively, were found to have significant expansions and contractions (Figs. S3 and 3, respectively). Half of these transporter gene families were related to base cation transport (Table S2), and all were found to be significantly expanding or contracting in the genus Suillus (Fig. 3 and S3). In the full dataset, the Atheliaceae and Russulaceae clades also possessed a large number of expansions and contractions (Fig. S3). In the partial subfamily dataset, 15 of 51 analysed transporter gene subfamilies were shown to be significantly expanding and contracting (Table S4), of which ten were related to base cation transport (Fig. 3, Table S4).

Figure 3Summary of copy number changes in significantly expanding and contracting transporter families (TFs) across the partial family dataset. The numbers at each node of the phylogeny (not to scale) indicate the count of TFs undergoing expansion (+) or contraction (−). Heatmaps display gene copy number changes for significantly expanding and contracting TFs, with contractions shown in blue and expansions in red: the left heatmap corresponds to internal nodes, and the right heatmap corresponds to tree tips. Significant expansions and contractions are indicated with an asterisk (*). For the internal node heatmap (left), gene copy number changes range from −22 to +49, with dashed red lines linking each node to its corresponding heatmap row. For the tip heatmap (right), changes range from −48 to +101. In both heatmaps, base cation TFs are positioned on the left and separated from other TFs on the right.

Base cation transporter gene family evolution

Across the whole phylogeny, the MgtE gene family possessed the largest number of expansion or contraction events, alongside the MSF gene superfamily in the full dataset, and the β-amyloid cleaving enzyme 1 gene family (TCDB ID 1.A.33) in the partial dataset. Within the genus Suillus, in both datasets, several branches show significant expansions and contractions in base cation transporter gene families (Fig. 3 and S3); base cation transporter gene families with the largest number of expansion or contraction events in the full dataset are the MSF gene superfamily and the ABC gene superfamily (Fig. S3); and in the partial dataset the same two gene families with the addition of the MgtE gene family and the β-amyloid cleaving enzyme 1 gene family (Fig. 3). Branches within the Piloderma clade also exhibited high numbers of expansions and contractions in both the full and partial family datasets (Figs. S3 and 3, respectively), with the MgtE gene family exhibiting the largest number of expansion or contraction events. Branches leading to the saprotrophic fungi C. puteana and S. lacrymans show low numbers of significant expansions and contractions in base cation transporter gene families in both the full and the partial datasets. The Atheliaceae and Russulaceae also have a large number of expansions and contractions in base cation transporter gene families (Fig. S3). In the partial subfamily dataset there are significant expansions and contractions in branches leading to 14 internal nodes (Fig. S4 in the Supplement).

Fungal mating-type pheromone receptor (MAT-PR) transporter gene family evolution

In addition to examining base cation transporter gene families, we also analysed transporter gene families associated with biological processes that may influence evolutionary rates and adaptation, such as those involved in sexual reproduction. Since variations in evolutionary and adaptive rates could, in turn, impact the mineral weathering capabilities of different taxa, these gene families were considered to be of particular interest. Our CAFE5 analyses indicated numerous significant expansions and contractions in the fungal mating-type pheromone receptor (MAT-PR) gene family (TCDB ID 9.B.45), which is involved in mate recognition and compatibility. The MAT-PR gene family was inferred to be significantly expanding and contracting at several nodes in the genus Suillus in both the full and partial datasets (Fig. S3 and 3, respectively), as well as in the branch leading to Russula emetica (Fig. 3).

Mg2+ transporter-E (MgtE) gene family evolution

The Mg2+ transporting MgtE gene family was prominent in our CAFE5 results, with high numbers of expansions and contractions in both the full and the partial datasets, and particularly in the genus Suillus. Furthermore, Mg plays an important role in plants and fungi, and has been found to be taken up by ECM fungi from minerals and mineral soils (Fahad et al., 2016; Mahmood et al., 2024). A phylogenetic tree was reconstructed from amino acid sequences of the MgtE gene family using the partial family dataset. The goal was to determine whether the genus Suillus contains an expansion of a single homologous transporter gene, or instead multiple transporter genes of different origins. The results supported the latter, revealing several distinct clades of MgtE genes present in each taxon (Fig. S5 in the Supplement).

3.2 Base cation uptake by mycelia grown in pure culture

3.2.1 Correlation between base cation transporter gene family copy number and mycelial base cation concentration

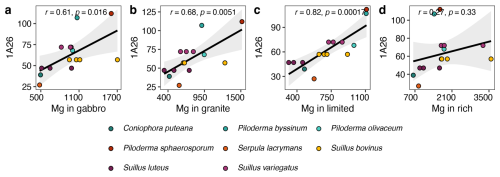

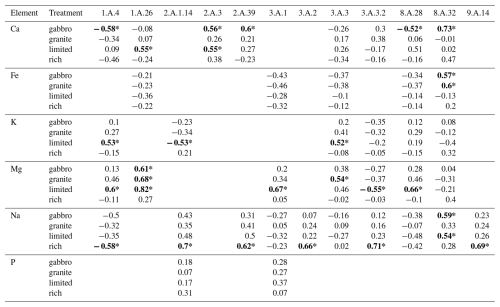

Of the 25 base cation transporter gene families that exhibited significant expansions or contractions across all three datasets, 12 showed significant correlations between mycelial base cation concentrations and the transporter gene families that transporting the corresponding base cation. From these, six are specifically involved in the transport of Ca2+, Fe2+ or Fe3+, K+, Mg2+, Na+ and P and six are more general base cation transporters not linked to a specific base cation. Across all treatments there were 28 significant correlations, of which 23 were positive. Of these, nine were in either the gabbro or the granite treatment. In particular, mycelial Mg concentration was significantly positively correlated with genome copy numbers of the MgtE gene family in the gabbro, granite and limited treatments, and there was a positive correlation in the rich treatment (Fig. 4a–d, respectively).

Figure 4Pearson's correlations between mycelial magnesium (Mg) concentrations (mg kg−1) and transporter gene copy numbers of the Mg2+ transporter-E (MgtE) family (TCDB ID: 1.A.26) in the corresponding fungal genomes. Element concentration is given as the estimated mean values in eight different fungal species grown in pure culture in gabbro, granite, limited and rich treatments. Significant correlations with p<0.05 are found in panels (a), (b) and (c).

3.2.2 Mycelial base cation concentration

For mycelial concentration of each base cation measured, ANOVA showed that there were significant (p<0.001) overall effects of isolate, treatment (gabbro, granite, limited or rich) and the interaction between isolate and treatment. For all elements there were examples of higher element concentrations after growth with gabbro and/or granite as compared to the limited treatment (Fig. S6 in the Supplement). In particular, all S. bovinus isolates showed significantly greater Mg mycelial concentration in the gabbro treatment compared to the granite and limited treatment (Fig. S6d). For Fe, all isolates excluding P. byssinum and S. lacrymans showed significantly greater Fe mycelial concentrations in the gabbro and the granite treatment compared to the limited (Fig. S6b). There were also examples of higher element concentration in the rich treatment as compared to the mineral treatments. Nearly all isolates showed significantly greater Ca, Fe and Mg mycelial concentrations in the rich treatment compared to the limited (Fig. S6d). Six Suillus isolates and four Piloderma isolates showed significantly greater K mycelial concentrations in the rich treatment compared to the limited (Fig. S6c).

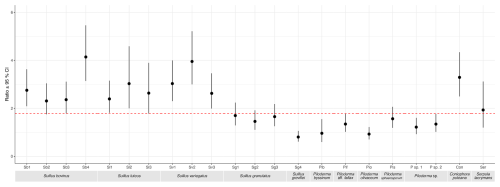

Comparisons between Suillus, Piloderma, and saprotroph isolates of the ratio of individual element concentrations in mycelia grown in mineral treatments compared to the limited treatment showed different patterns (Figs. S7 and S8 in the Supplement). The linear models showed many instances of a significant overall effect (p<0.05) of both isolate and treatment on the ratio between concentrations of each element in the mineral and limited treatments. The strongest difference between groups was seen in Ca. Furthermore, for Ca ratios between the gabbro and limited treatments, all S. bovinus, S. luteus and S. variegatus isolates, as well as C. puteana exhibit significantly higher values than all but one Piloderma isolate, as indicated by non-overlapping 95 % confidence intervals in Fig. 5. For Mg ratios between both mineral treatments and the limited treatment, the isolate S. luteus 2 had a significantly higher ratio between gabbro and limited treatments for Mg and P concentrations, and between granite and limited treatments for Mg, compared to all other isolates (Figs. S7 and S8). In all other cases, for both mineral treatments, isolates showed similar variation in ratios within and between genera (Figs. S7 and S8).

Figure 5Ratios of mycelial calcium (Ca) concentration (mg kg−1) between gabbro and limited treatments for each fungal isolate. Isolates include Suillus bovinus (Sb1–4), S. luteus (Sl1–3), S. variegatus (Sv1–3), S. granulatus (Sg1–3), S. grevillei (Sg4), Piloderma byssinum (Pb), P. aff. fallax (Pf), P. olivaceum (Po), P. sphaerosporum (Ps), Piloderma sp. 1, Piloderma sp. 2, Coniophora puteana (Cp), and Serpula lacrymans (Sl). Data points represent the mean ratio of Ca concentration between gabbro and limited treatments for each isolate, with error bars indicating the 95 % confidence interval. Isolates with non-overlapping confidence intervals are considered significantly different from one another. The red dashed line represents a ratio of 1.78, distinguishing isolates with significantly higher Ca concentrations above the line (S. luteus, S. variegatus, and all S. bovinus isolates except Sb2) from those below it, which include all Piloderma species except P. sphaerosporum.

3.2.3 Mycelial biomass and C:N ratio

There was a significant overall effect (p<0.001) of species, treatment (gabbro, granite, limited or rich), and their interaction for fungal biomass and C:N ratio. Overall, Suillus and Piloderma species produced similar amounts of biomass across all treatments (Fig. S9a in the Supplement). Piloderma olivaceum had significantly higher biomass than all other species in the gabbro treatment, followed by S. variegatus which had significantly higher biomass compared to the remaining species. In the granite and rich treatments P. olivaceum and S. variegatus both had significantly greater biomass than other species. Piloderma byssinum produced significantly less biomass than all other species in all treatments. When comparing different treatments within each species, S. bovinus showed a significant increase in biomass in the rich treatment compared to all other treatments (Fig. S9b), and S. luteus, P. olivaceum and isolates Piloderma sp. 1 and sp. 2 produced significantly more biomass in the gabbro, granite and rich treatments compared to the limited treatment. When comparing C:N ratios between treatments within species, S. luteus was the only species to show a significant difference, with a higher C:N ratio in the rich treatment compared to the limited treatment (Table S6a in the Supplement), while all other species showed no significant variation. In contrast, when comparing between species within treatments, Suillus species generally had a higher C:N ratio than Piloderma species, and saprotrophic species consistently had low C:N ratios (Table S6b).

Rapid base cation transporter gene family evolution in Suillus species

The requirement for base cations by plants and fungi is a key driver of biological mineral weathering. Several ECM fungal species facilitate this process by colonising mineral surfaces, producing LMWOAs and altering soil chemistry (Calvaruso et al., 2013; Gazze et al., 2012; Griffiths et al., 1994; Schmalenberger et al., 2015; van Scholl et al., 2006). The genus Suillus has the ability to acquire base cations from mineral sources (Balogh-Brunstad et al., 2008a; Wallander, 2000). Ordination analysis based on transporter gene family copy numbers revealed that members of the families Suillaceae and Russulaceae formed distinct clusters, separate from each other and from other Agaricomycotina species, including other ECM taxa (Fig. 2). Among the transporter gene families contributing most strongly to the observed patterns, base cation transporter gene families were particularly abundant, suggesting that these transporters play a crucial role in the ecological lifestyle and environmental adaptations of these two fungal groups.

In general, genes related to cellular maintenance and growth tend to have stable copy numbers since mutations in these genes can reduce fitness. In contrast, genes associated with ecological adaptations, including responses to stress, exhibit greater variation in copy numbers, as changes in these genes are less likely to be detrimental and may even provide adaptive advantages (Wapinski et al., 2007). Transporter genes, which are often involved in abiotic and biotic environmental interactions, are therefore expected to undergo frequent expansions and contractions, enabling rapid adaptation to environmental changes and stressors. For example, Suillus luteus has been shown to possess single nucleotide polymorphisms and gene copy number variation in genes involved in heavy metal homeostasis, which includes metal ion transporter genes, enabling tolerant populations to grow under exposure to heavy metals (Bazzicalupo et al., 2020; Colpaert et al., 2011; Ruytinx et al., 2011, 2017, 2019). Our analyses of 108 Agaricomycotina genomes confirm significant expansions and contractions in base cation transporter gene families, highlighting their rapid evolution within the genus Suillus and indicating that the evolutionary changes in copy number are not random and are likely related to species specific adaptation. Additionally, we identified 23 significant positive correlations between different elements and the copy numbers of expanding or contracting base cation transporter gene families associated with their uptake, nine of which were in the mineral treatments. These findings suggest that increased copy numbers of certain base cation transporter gene families may contribute to enhanced uptake of specific base cations, however this pattern is not universal. This offers partial support for our first hypothesis that greater base cation uptake is dependent on base cation transporter gene family copy numbers which have resulted from evolutionary expansions. In cases where no significant correlation was found, other levels of regulation such as transcriptional up-regulation may play a larger role, and this requires further investigation.

Significant expansions and contractions were identified in 13 transporter gene families in the full dataset, 22 in the partial dataset, and 15 in the partial subfamily dataset. All of these exhibited significant changes in the genus Suillus. While the number of affected transporter families varied across datasets, likely due to the scaling of the full dataset and the difference in the number of taxa included, the general trend of expansion and contractions was consistently recovered across all datasets.

Significant expansions of the fungal mating-type pheromone receptor (MAT-PR) gene family were observed in several Suillus species, in both the full and partial datasets (Figs. S3 and 3, respectively), with a notable expansion in Russula emetica in the full dataset. This gene family encodes pheromone receptors located on the plasma membrane that play key roles in mate recognition, compatibility, and the reciprocal migration of nuclei during mating (Coelho et al., 2017; Di Segni et al., 2011; James, 2015; Xue et al., 2008). Sexual reproduction, which these receptors facilitate, promotes genetic recombination, enhances the selection of advantageous traits, and accelerated adaptation compared to asexual reproduction (Becks and Agrawal, 2012; McDonald et al., 2016; Nieuwenhuis and James, 2016). It is especially advantageous in unstable or nutritionally variable environments (Nieuwenhuis and James, 2016). Thus, the observed gene family expansions may indicate an increased reliance on sexual reproduction, potentially enhancing adaptability in changing environments.

Significantly evolving base cation transporters and their functions

Approximately half of the transporter gene families showing significant expansions and contractions in each dataset are involved in base cation transport, suggesting that base cation transport may play a key role in responding to environmental fluctuations and stress. Gene families that exhibit copy number variation are more likely to contribute to adaptive processes (Wapinski et al., 2007). In addition, expansions and contractions in these transporter families are likely linked to the demand for base cation uptake, and their occurrence within certain taxa, such as the genus Suillus, may reflect enhanced mineral weathering capabilities. Branches leading to S. lakei, S. variegatus, S. cothurnatus and S. cf. subluteus, as well as two internal branches within the genus Suillus possess significant expansions in the MgtE gene family (Fig. 3). Though primarily studied in bacteria and mammals, members of the MgtE gene family are identified as facilitators of Mg2+, Zn2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Fe and Cu influx (Goytain and Quamme, 2005; Smith et al., 1995), and play roles in Mg2+ homeostasis (Conn et al., 2011; Franken et al., 2022; Hattori et al., 2009; Hermans et al., 2013). Additionally, it has been found that many organisms have multiple copies of one type of Mg2+ transporter gene family, which may explain the relatively low abundance of other Mg2+ transporter gene families in our datasets (Franken et al., 2022). In plants, it was reported that there are many gene copies of a Mg2+ transporter gene family, the CorA/Mrs2 metal ion transporter (MIT) gene family, and that they are not functionally redundant (Gebert et al., 2009; Schmitz et al., 2013). Our analysis suggests multiple different homologous MgtE genes have undergone expansions, as observed in the phylogenetic gene tree of MgtE gene family members present in the partial dataset (Fig. S5). Furthermore, when comparing within each taxon, MgtE gene amino acid sequences generally had low similarity, with the majority having around 30 %–40 % shared identity. This may indicate that the genes of the MgtE family are, like those of the MIT gene family in plants, not functionally redundant. In Suillus, the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) shows significant changes across both full and partial datasets, and P. sphaerosporum shows a significant contraction in each dataset (Figs. S3 and 3, respectively). This gene superfamily is large and diverse and reported to transport solutes such as sugars and cations (Law et al., 2008).

Although S. bovinus possesses two significant contractions in the full dataset, three in the partial family dataset and no expansions in base cation transporter families, it had significantly higher mycelial concentrations of Mg, Ca and Fe in the gabbro treatment compared to the limited treatment. One isolate in particular (Sb1), had significantly higher mycelial concentration of all base cations in the gabbro treatment compared to the limited (Fig. S6). Similarly, S. luteus, which exhibited only one significant contraction in the full dataset, had significantly higher mycelial concentrations of Ca and Fe in the gabbro treatment compared to the limited treatment. Together, these findings support our second hypothesis that mineral weathering results in base cation uptake by Suillus species when grown with mineral additions. The significant uptake of base cations, despite the lack of expansions in base cation transporter gene families in S. bovinus and S. luteus may reflect that strong mineral weathering capability was already present in their ancestral lineage, reducing the necessity for additional expansions. It could also indicate that another level of regulation may play a larger role than gene copy numbers in base cation uptake in these taxa.

In addition to significant expansions in the MgtE gene family, S. variegatus also exhibits significant expansions in the nucleobase : cation symporter-1 gene family (TCDB ID 2.A.39) which is associated with Na uptake. In pure culture however, S. variegatus exhibited significantly higher mycelial Ca and Fe concentrations in the gabbro compared to the limited treatment, further supporting our second hypothesis. Like S. bovinus and S. luteus, the observed Ca and Fe uptake could indicate that expansions of Ca and Fe transporting gene families in the ancestors of S. variegatus were already sufficient to support mineral weathering and further expansions were not required. It could also be that another form of regulation, such as transcriptional up-regulation, may play a role in the uptake of Ca and Fe in S. variegatus. Alongside significant expansions in the MgtE gene family, S. lakei, S. cothurnatus and S. cf. subluteus have particularly high numbers of other base cation transporter gene families with significant expansions in the full and the partial family datasets, which may also indicate a heightened ability to take up base cations and potentially weather minerals, however this needs experimental confirmation.

Table 2Summary of r values for Pearson's correlations between estimated mean mycelial base cation or P concentration and base cation transporter gene family copy numbers across eight different fungal species grown in pure culture in gabbro, granite, limited and rich treatments. Base cation transporter gene families were only correlated with the elements they are associated with the uptake of. The table indicates element, treatment and TCDB IDs (see Tables S2 and S4) of the transporter gene families. The r values with statistically significant p values (p≤0.05) are indicated in bold and with an asterisk. Empty cells denote that the transporter gene family in that column does not transport the element listed in the corresponding row.

Mycelial base cation uptake correlates with base cation transporter gene family copy numbers

Copy numbers of the MgtE gene family were shown to have significant positive correlations with Mg uptake in the gabbro, granite and limited treatments and a weak positive correlation in the rich treatment (Fig. 4), which may indicate that these genes are only transcribed in conditions where nutrients are limited and mineral weathering is required to access nutrients. The major facilitator gene superfamily showed no significant correlation between gene copy number and base cation uptake, however when further separated into subfamilies, copy numbers of the anion : cation symporter (ACS) gene family (TCDB ID: 2.A.1.14), associated with K, Na and P transport (Farsi et al., 2016; Pavón et al., 2008; Prestin et al., 2014), had a significant positive correlation with Na uptake in the rich treatment (Table 2). The TRP-CC gene family and the ACS gene family showed significant negative correlations with Ca uptake in the gabbro treatment and K uptake in the limited treatment, respectively, which may indicate that another mechanism of regulation, such as transcriptional up-regulation of a smaller number of genes, may be favoured (Table 2). Additionally, there were significant correlations between uptake of specific base cations and gene copy numbers of transporter families which are not associated with the transport of those base cations. For example, the oligopeptide transporter (OPT) family, which is associated with Fe transport (Kurt, 2021; Mousavi et al., 2020; Wintz et al., 2003), was significantly negatively correlated with Mg uptake in the gabbro, granite and limited treatments. This may indicate an inhibitory effect of proteins of this family on Mg uptake (data not shown). Taken together, these findings indicate that gene copy numbers may play a key role in the regulation of base cation uptake by certain base cation transporter gene families, like the MgtE gene family, and offer circumstantial support for the first part of our first hypothesis, that greater base cation uptake is dependent on base cation transporter gene family copy numbers. Regulation of base cation uptake by other gene families may take place at the transcriptional or translational level.

Proportionally higher base cation uptake of Ca in Suillus compared to Piloderma indicating greater weathering capabilities

The comparison of base cations and P ratios in the mineral and limited treatments supports our second hypothesis. However, these comparisons only partially support our third hypothesis that base cation uptake by Suillus species would exceed that of other taxa when grown with mineral additions. A clear pattern emerged only for Ca in ratios gabbro and limited treatments, where Suillus species as a group exhibited significantly higher ratios than most other taxa, supporting our third hypothesis. For other base cations, the ratios between mineral and limited treatments showed either no pattern or mixed results, with several Piloderma isolates performing equally well compared to the Suillus isolates, contradicting our third hypothesis. Together with evidence of rapid evolution in multiple base cation transporter gene families in Piloderma, these findings suggest that enhanced mineral weathering capability may extend beyond Suillus to include Piloderma as well.

Suillus species, which commonly inhabit the B horizon in boreal forests, are capable of acquiring base cations directly from mineral sources. In this study, we investigated whether greater base cation uptake is associated with evolutionary expansions in the copy numbers of base cation transporter gene families. Base cation transporter gene families were among the most abundant transporter types, showing rapid evolution not only in Suillus, but also in the genus Piloderma. The MgtE gene family, in particular, exhibited numerous expansions and contractions across the whole phylogeny. Mycelial uptake of Mg in the presence of gabbro and granite, increased sharply with copy numbers of MgtE genes, and significant correlations were found in the gabbro, granite and limited treatments. Our findings highlight potential associations rather than definitive functional assignments, indicating that while gene copy number correlates with base cation uptake capacity, causal relationships remain to be validated experimentally.

Although this study focused primarily on Suillus, we found that Piloderma species also displayed significant expansions in transporter gene families, showed comparably similar base cation uptake to Suillus in many instances, and strongly contributed to the positive correlations observed between base cation uptake and base cation transporter gene family copy number. Future studies should examine mineral weathering capabilities of Piloderma species alongside Suillus species, and controlled pure culture experiments should incorporate a broader range of ECM fungi to assess the prevalence of mineral weathering in this guild. Additionally, investigating the transcriptional regulation of transporter proteins in Suillus and other ECM species could provide deeper insights into the mechanisms driving mineral weathering and base cation uptake.

Genome and proteome sequences were obtained from JGI Mycocosm (Grigoriev et al., 2014; https://mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov/mycocosm/species-tree/tree;aY7X8o?organism=agaricomycotina, last access: 20 June 2022).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-22-8047-2025-supplement.

All authors contributed to conceptualisation of the project. KK and MSG performed bioinformatic analyses. KK and PF carried out experimental work and elemental analyses. KK wrote the manuscript with contribution from all co-authors.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank Erica Packard and Carles Castaño for assistance with collecting Suillus fruitbodies, Geoffry Daniels for use of fungal cultures, and Yasaman Najafi, Katarina Ihrmark, and Rena Gadjieva for help in the laboratory with the pure culture experiment.

This research has been supported by the Svenska Forskningsrådet Formas (grant no. 2020-01100).

The publication of this article was funded by the Swedish Research Council, Forte, Formas, and Vinnova.

This paper was edited by Mark Lever and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Adeleke, R. A., Cloete, T. E., Bertrand, A., and Khasa, D. P.: Iron ore weathering potentials of ectomycorrhizal plants, Mycorrhiza, 22, 535–544, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-012-0431-5, 2012.

Akselsson, C., Westling, O., Sverdrup, H., and Gundersen, P.: Nutrient and carbon budgets in forest soils as decision support in sustainable forest management, For. Ecol. Manag., 238, 167–174, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2006.10.015, 2007.

Akselsson, C., Belyazid, S., Stendahl, J., Finlay, R., Olsson, B. A., Erlandsson Lampa, M., Wallander, H., Gustafsson, J. P., and Bishop, K.: Weathering rates in Swedish forest soils, Biogeosciences, 16, 4429–4450, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-16-4429-2019, 2019.

Ballesterus: Utensils, Github [code], https://github.com/ballesterus/Utensils (last access: 8 August 2022), 2015.

Balogh-Brunstad, Z., Keller, C. K., Dickinson, J. T., Stevens, F., Li, C. Y., and Bormann, B. T.: Biotite weathering and nutrient uptake by ectomycorrhizal fungus, Suillus tomentosus, in liquid-culture experiments, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 72, 2601–2618, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2008.04.003, 2008a.

Balogh-Brunstad, Z., Keller, C. K., Gill, R. A., Bormann, B. T., and Li, C. Y.: The effect of bacteria and fungi on chemical weathering and chemical denudation fluxes in pine growth experiments, Biogeochemistry, 88, 153–167, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-008-9202-y, 2008b.

Bazilevskaya, E., Lebedeva, M., Pavich, M., Rother, G., Parkinson, D. Y., Cole, D., and Brantley, S. L.: Where fast weathering creates thin regolith and slow weathering creates thick regolith, Earth Surf. Process. Landf., 38, 847–858, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.3369, 2013.

Bazzicalupo, A. L., Ruytinx, J., Ke, Y. H., Coninx, L., Colpaert, J. V., Nguyen, N. H., Vilgalys, R., and Branco, S.: Fungal heavy metal adaptation through single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy-number variation, Mol. Ecol., 29, 4157–4169, https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15618, 2020.

Becks, L. and Agrawal, A. F.: The Evolution of Sex Is Favoured During Adaptation to New Environments, PLoS Biol., 10, e1001317, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001317, 2012.

Black, J. R., Yin, Q.-Z., Rustad, J. R., and Casey, W. H.: Magnesium isotopic equilibrium in chlorophylls, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 129, 8690–8691, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja072573i, 2007.

Bonneville, S., Smits, M. M., Brown, A., Harrington, J., Leake, J. R., Brydson, R., and Benning, L. G.: Plant-driven fungal weathering: Early stages of mineral alteration at the nanometer scale, Geology, 37, 615–618, https://doi.org/10.1130/G25699A.1, 2009.

Bonneville, S., Bray, A. W., and Benning, L. G.: Structural Fe(II) Oxidation in Biotite by an Ectomycorrhizal Fungi Drives Mechanical Forcing, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 5589–5596, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b06178, 2016.

Bose, J., Babourina, O., and Rengel, Z.: Role of magnesium in alleviation of aluminium toxicity in plants, J. Exp. Bot., 62, 2251–2264, https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erq456, 2011.

Calvaruso, C., Turpault, M.-P., Frey-Klett, P., Uroz, S., Pierret, M.-C., Tosheva, Z., and Kies, A.: Increase of apatite dissolution rate by Scots pine roots associated or not with Burkholderia glathei PML1(12)Rp in open-system flow microcosms, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 106, 287–306, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2012.12.014, 2013.

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M., and Gabaldón, T.: trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses, Bioinformatics, 25, 1972–1973, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348, 2009.

Chen, F., Mackey, A. J., Stoeckert, C. J., and Roos, D. S.: OrthoMCL-DB: querying a comprehensive multi-species collection of ortholog groups, Nucleic Acids Res., 34, D363–D368, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkj123, 2006.

Clemmensen, K. E., Bahr, A., Ovaskainen, O., Dahlberg, A., Ekblad, A., Wallander, H., Stenlid, J., Finlay, R. D., Wardle, D. A., and Lindahl, B. D.: Roots and Associated Fungi Drive Long-Term Carbon Sequestration in Boreal Forest, Science, 339, 1615–1618, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1231923, 2013.

Coelho, M. A., Bakkeren, G., Sun, S., Hood, M. E., and Giraud, T.: Fungal Sex: The Basidiomycota, Microbiol. Spectr., 5, 5.3.12, https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0046-2016, 2017.

Colpaert, J. V., Wevers, J. H. L., Krznaric, E., and Adriaensen, K.: How metal-tolerant ecotypes of ectomycorrhizal fungi protect plants from heavy metal pollution, Ann. For. Sci., 68, 17–24, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-010-0003-9, 2011.

Conn, S. J., Conn, V., Tyerman, S. D., Kaiser, B. N., Leigh, R. A., and Gilliham, M.: Magnesium transporters, MGT2/MRS2-1 and MGT3/MRS2-5, are important for magnesium partitioning within Arabidopsis thaliana mesophyll vacuoles, New Phytol., 190, 583–594, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03619.x, 2011.

Corratgé, C., Zimmermann, S., Lambilliotte, R., Plassard, C., Marmeisse, R., Thibaud, J.-B., Lacombe, B., and Sentenac, H.: Molecular and Functional Characterization of a Na+-K+ Transporter from the Trk Family in the Ectomycorrhizal Fungus Hebeloma cylindrosporum, J. Biol. Chem., 282, 26057–26066, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M611613200, 2007.

Danecek, P., Bonfield, J. K., Liddle, J., Marshall, J., Ohan, V., Pollard, M. O., Whitwham, A., Keane, T., McCarthy, S. A., Davies, R. M., and Li, H.: Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools, GigaScience, 10, giab008, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giab008, 2021.

Di Segni, G., Gastaldi, S., Zamboni, M., and Tocchini-Valentini, G. P.: Yeast pheromone receptor genes STE2 and STE3 are differently regulated at the transcription and polyadenylation level, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 108, 17082–17086, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1114648108, 2011.

EdoardoPiombo: CafeMiner, Github [code], https://github.com/EdoardoPiombo/CafeMiner/tree/main, last access: 20 December 2023.

Fahad, Z. A., Bolou-Bi, E. B., Kohler, S. J., Finlay, R. D., and Mahmood, S.: Fractionation and assimilation of Mg isotopes by fungi is species dependent, Environ. Microbiol. Rep., 8, 956–965, https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-2229.12459, 2016.

Farsi, Z., Preobraschenski, J., van den Bogaart, G., Riedel, D., Jahn, R., and Woehler, A.: Single-vesicle imaging reveals different transport mechanisms between glutamatergic and GABAergic vesicles, Science, 351, 981–984, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad8142, 2016.

Finlay, R. D., Mahmood, S., Rosenstock, N., Bolou-Bi, E. B., Köhler, S. J., Fahad, Z., Rosling, A., Wallander, H., Belyazid, S., Bishop, K., and Lian, B.: Reviews and syntheses: Biological weathering and its consequences at different spatial levels – from nanoscale to global scale, Biogeosciences, 17, 1507–1533, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-1507-2020, 2020.

Fomina, M., Burford, E. P., Hillier, S., Kierans, M., and Gadd, G. M.: Rock-Building Fungi, Geomicrobiol. J., 27, 624–629, https://doi.org/10.1080/01490451003702974, 2010.

Franken, G. A. C., Huynen, M. A., Martínez-Cruz, L. A., Bindels, R. J. M., and de Baaij, J. H. F.: Structural and functional comparison of magnesium transporters throughout evolution, Cell. Mol. Life Sci., 79, 418, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-022-04442-8, 2022.

Fritz, S. J.: A comparative study of gabbro and granite weathering, Chem. Geol., 68, 275–290, https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2541(88)90026-5, 1988.

Garcia, K., Delteil, A., Conéjéro, G., Becquer, A., Plassard, C., Sentenac, H., and Zimmermann, S.: Potassium nutrition of ectomycorrhizal Pinus pinaster: overexpression of the Hebeloma cylindrosporum Hc Trk1 transporter affects the translocation of both K+ and phosphorus in the host plant, New Phytol., 201, 951–960, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12603, 2014.

Gazze, S. A., Saccone, L., Ragnarsdottir, K. V., Smits, M. M., Duran, A. L., Leake, J. R., Banwart, S. A., and McMaster, T. J.: Nanoscale channels on ectomycorrhizal-colonized chlorite: Evidence for plant-driven fungal dissolution, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeosciences, 117, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012jg002016, 2012.

Gebert, M., Meschenmoser, K., Svidová, S., Weghuber, J., Schweyen, R., Eifler, K., Lenz, H., Weyand, K., and Knoop, V.: A Root-Expressed Magnesium Transporter of the MRS2/MGT Gene Family in Arabidopsis thaliana Allows for Growth in Low-Mg2+ Environments, Plant Cell, 21, 4018–4030, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.109.070557, 2009.

Genre, A., Lanfranco, L., Perotto, S., and Bonfante, P.: Unique and common traits in mycorrhizal symbioses, Nat. Rev. Microbiol., 18, 649–660, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-0402-3, 2020.

Glowa, K. R., Arocena, J. M., and Massicotte, H. B.: Extraction of potassium and/or magnesium from selected soil minerals by Piloderma, Geomicrobiol. J., 20, 99–111, https://doi.org/10.1080/01490450303881, 2003.

Goldich, S. S.: A Study in Rock-Weathering, J. Geol., https://doi.org/10.1086/624619, 1938.

Goytain, A. and Quamme, G. A.: Functional characterization of human SLC41A1, a Mg2+ transporter with similarity to prokaryotic MgtE Mg2+ transporters, Physiol. Genomics, 21, 337–342, https://doi.org/10.1152/physiolgenomics.00261.2004, 2005.

Griffiths, R. P., Baham, J. E., and Caldwell, B. A.: Soil solution chemistry of ectomycorrhizal mats in forest soil, Soil Biol. Biochem., 26, 331–337, https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(94)90282-8, 1994.

Grigoriev, I. V., Nikitin, R., Haridas, S., Kuo, A., Ohm, R., Otillar, R., Riley, R., Salamov, A., Zhao, X., Korzeniewski, F., Smirnova, T., Nordberg, H., Dubchak, I., and Shabalov, I.: MycoCosm portal: gearing up for 1000 fungal genomes, Nucl. Acids Res., 42, D699–D704, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt1183, 2014 (data available at: https://mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov/mycocosm/species-tree/tree;aY7X8o?organism=agaricomycotina, last access: 20 June 2022).

Harmon, L. J., Weir, J. T., Brock, C. D., Glor, R. E., and Challenger, W.: GEIGER: investigating evolutionary radiations, Bioinformatics, 24, 129–131, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm538, 2008.

Hattori, M., Iwase, N., Furuya, N., Tanaka, Y., Tsukazaki, T., Ishitani, R., Maguire, M. E., Ito, K., Maturana, A., and Nureki, O.: Mg2+-dependent gating of bacterial MgtE channel underlies Mg2+ homeostasis, EMBO J., 28, 3602–3612, https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2009.288, 2009.

Hermans, C., Conn, S. J., Chen, J. G., Xiao, Q. Y., and Verbruggen, N.: An update on magnesium homeostasis mechanisms in plants, Metallomics, 5, 1170–1183, https://doi.org/10.1039/c3mt20223b, 2013.

Hoang, D. T., Chernomor, O., von Haeseler, A., Minh, B. Q., and Vinh, L. S.: UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation, Mol. Biol. Evol., 35, 518–522, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msx281, 2018.

Hobbie, E. A. and Horton, T. R.: Evidence that saprotrophic fungi mobilise carbon and mycorrhizal fungi mobilise nitrogen during litter decomposition, New Phytol., 173, 447–449, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.01984.x, 2007.

Hoffland, E., Kuyper, T. W., Wallander, H., Plassard, C., Gorbushina, A. A., Haselwandter, K., Holmström, S., Landeweert, R., Lundström, U. S., Rosling, A., Sen, R., Smits, M. M., Van Hees, P. A., and Van Breemen, N.: The role of fungi in weathering, Front. Ecol. Environ., 2, 258–264, https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2004)002[0258:TROFIW]2.0.CO;2, 2004.

Holtstam, D., Andersson, U., Lundström, I., Langhof, J., and Nysten, P.: The Bastnäs-type REE-mineralisations in north-western Bergslagen, Sweden – a summary with geological background and excursion guide, ISBN 978-91-7158-700-8, 2004.

Hothorn, T., Bretz, F., and Westfall, P.: Simultaneous Inference in General Parametric Models, Biom. J., 50, 346–363, https://doi.org/10.1002/bimj.200810425, 2008.

Inkscape Project: Inkscape 1.2.1 (9c6d41e, 2022-07-14), https://inkscape.org (last access: 17 November 2023), 2022.

James, T. Y.: Why mushrooms have evolved to be so promiscuous: Insights from evolutionary and ecological patterns, Fungal Biol. Rev., 29, 167–178, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbr.2015.10.002, 2015.

Jongmans, A. G., van Breemen, N., Lundström, U., van Hees, P. A. W., Finlay, R. D., Srinivasan, M., Unestam, T., Giesler, R., Melkerud, P.-A., and Olsson, M.: Rock-eating fungi, Nature, 389, 682–683, https://doi.org/10.1038/39493, 1997.

Kalyaanamoorthy, S., Minh, B. Q., Wong, T. K. F., von Haeseler, A., and Jermiin, L. S.: ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates, Nat. Methods, 14, 587–589, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4285, 2017.

Katoh, K., Kuma, K., Toh, H., and Miyata, T.: MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment, Nucleic Acids Res., 33, 511–518, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki198, 2005.

Klaminder, J., Lucas, R. W., Futter, M. N., Bishop, K. H., Köhler, S. J., Egnell, G., and Laudon, H.: Silicate mineral weathering rate estimates: Are they precise enough to be useful when predicting the recovery of nutrient pools after harvesting?, For. Ecol. Manag., 261, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2010.09.040, 2011.

Kohler, A., Kuo, A., Nagy, L. G., Morin, E., Barry, K. W., Buscot, F., Canback, B., Choi, C., Cichocki, N., Clum, A., Colpaert, J., Copeland, A., Costa, M. D., Dore, J., Floudas, D., Gay, G., Girlanda, M., Henrissat, B., Herrmann, S., Hess, J., Hogberg, N., Johansson, T., Khouja, H. R., LaButti, K., Lahrmann, U., Levasseur, A., Lindquist, E. A., Lipzen, A., Marmeisse, R., Martino, E., Murat, C., Ngan, C. Y., Nehls, U., Plett, J. M., Pringle, A., Ohm, R. A., Perotto, S., Peter, M., Riley, R., Rineau, F., Ruytinx, J., Salamov, A., Shah, F., Sun, H., Tarkka, M., Tritt, A., Veneault-Fourrey, C., Zuccaro, A., Mycorrhizal Genomics Initiative Consortium, Tunlid, A., Grigoriev, I. V., Hibbett, D. S., and Martin, F.: Convergent losses of decay mechanisms and rapid turnover of symbiosis genes in mycorrhizal mutualists, Nat. Genet., 47, 410-U176, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3223, 2015.

Kurt, F.: An Insight into Oligopeptide Transporter 3 (OPT3) Family Proteins, Protein Pept. Lett., 28, 43–54, https://doi.org/10.2174/0929866527666200625202028, 2021.

Law, C. J., Maloney, P. C., and Wang, D.-N.: Ins and outs of major facilitator superfamily antiporters, Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 62, 289–305, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093329, 2008.

Lenth, R. V.: emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means, CRAN [code], https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.emmeans, 2024.

LePage, B. A., Currah, R. S., Stockey, R. A., and Rothwell, G. W.: Fossil ectomycorrhizae from the middle Eocene, Am. J. Bot., 84, 410–412, https://doi.org/10.2307/2446014, 1997.

Lofgren, L., Nguyen, N. H., Kennedy, P. G., Pérez-Pazos, E., Fletcher, J., Liao, H.-L., Wang, H., Zhang, K., Ruytinx, J., Smith, A. H., Ke, Y.-H., Cotter, H. V. T., Engwall, E., Hameed, K. M., Vilgalys, R., and Branco, S.: Suillus: an emerging model for the study of ectomycorrhizal ecology and evolution, New Phytol., 242, 1448–1475, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19700, 2024.

Mahmood, S., Fahad, Z., Bolou-Bi, E. B., King, K., Köhler, S. J., Bishop, K., Ekblad, A., and Finlay, R. D.: Ectomycorrhizal fungi integrate nitrogen mobilisation and mineral weathering in boreal forest soil, New Phytol., 242, 1545–1560, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19260, 2024.

Marupakula, S., Mahmood, S., Clemmensen, K. E., Jacobson, S., Hogbom, L., and Finlay, R. D.: Root associated fungi respond more strongly than rhizosphere soil fungi to N fertilization in a boreal forest, Sci. Total Environ., 766, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142597, 2021.

Marx, D. H.: The influence of ectotrophic mycorrhizal fungi on the resistance of pine roots to pathogenic infections. II. Production, identification, and biological activity of antibiotics produced by Leucopaxillus cerealis var. piceina, Phytopathology, 59, 411–417, 1969.

Mazerolle, M. J.: AICcmodavg: Model Selection and Multimodel Inference Based on (Q)AIC(c), CRAN [code] https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.AICcmodavg, 2023.

McDonald, M. J., Rice, D. P., and Desai, M. M.: Sex speeds adaptation by altering the dynamics of molecular evolution, Nature, 531, 233–236, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17143, 2016.

Mendes, F. K., Vanderpool, D., Fulton, B., and Hahn, M. W.: CAFE 5 models variation in evolutionary rates among gene families, Bioinformatics, 36, 5516–5518, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa1022, 2020.

Miyauchi, S., Kiss, E., Kuo, A., Drula, E., Kohler, A., Sanchez-Garcia, M., Morin, E., Andreopoulos, B., Barry, K. W., Bonito, G., Buee, M., Carver, A., Chen, C., Cichocki, N., Clum, A., Culley, D., Crous, P. W., Fauchery, L., Girlanda, M., Hayes, R. D., Keri, Z., LaButti, K., Lipzen, A., Lombard, V., Magnuson, J., Maillard, F., Murat, C., Nolan, M., Ohm, R. A., Pangilinan, J., Pereira, M. D., Perotto, S., Peter, M., Pfister, S., Riley, R., Sitrit, Y., Stielow, J. B., Szollosi, G., Zifcakova, L., Stursova, M., Spatafora, J. W., Tedersoo, L., Vaario, L. M., Yamada, A., Yan, M., Wang, P. F., Xu, J. P., Bruns, T., Baldrian, P., Vilgalys, R., Dunand, C., Henrissat, B., Grigoriev, I. V., Hibbett, D., Nagy, L. G., and Martin, F. M.: Large-scale genome sequencing of mycorrhizal fungi provides insights into the early evolution of symbiotic traits, Nat. Commun., 11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18795-w, 2020.

Moldan, F., Stadmark, J., Fölster, J., Jutterström, S., Futter, M. N., Cosby, B. J., and Wright, R. F.: Consequences of intensive forest harvesting on the recovery of Swedish lakes from acidification and on critical load exceedances, Sci. Total Environ., 603–604, 562–569, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.013, 2017.

moshi4: CafePlotter v0.2.0, Github [code], https://github.com/moshi4/CafePlotter, last access: 5 October 2023.

Mousavi, S. R., Niknejad, Y., Fallah, H., and Tari, D. B.: Methyl jasmonate alleviates arsenic toxicity in rice, Plant Cell Rep., 39, 1041–1060, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-020-02547-7, 2020.

Mukhopadhyay, R., Nath, S., Kumar, D., Sahana, N., and Mandal, S.: Basics of the Molecular Biology: From Genes to Its Function, in: Genomics Data Analysis for Crop Improvement, edited by: Anjoy, P., Kumar, K., Chandra, G., and Gaikwad, K., Springer Nature, Singapore, 343–374, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-6913-5_14, 2024.

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A., and Minh, B. Q.: IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies, Mol. Biol. Evol., 32, 268–274, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu300, 2015.

Nieuwenhuis, B. P. S. and James, T. Y.: The frequency of sex in fungi, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., 371, 20150540, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0540, 2016.

Olsson, P. A. and Wallander, H.: Interactions between ectomycorrhizal fungi and the bacterial community in soils amended with various primary minerals, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 27, 195–205, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.1998.tb00537.x, 1998.

Paradis, E. and Schliep, K.: ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R, Bioinformatics, 35, 526–528, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty633, 2019.

Paris, F., Bonnaud, P., Ranger, J., and Lapeyrie, F.: In vitro weathering of phlogopite by ectomycorrhizal fungi, Plant Soil, 177, 191–201, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00010125, 1995.

Paris, F., Botton, B., and Lapeyrie, F.: In vitro weathering of phlogopite by ectomycorrhizal fungi: II. Effect of K+ and Mg2+ deficiency and N sources on accumulation of oxalate and H+, Plant Soil, 179, 141–150, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00011651, 1996.

Pavón, L. R., Lundh, F., Lundin, B., Mishra, A., Persson, B. L., and Spetea, C.: Arabidopsis ANTR1 is a thylakoid Na+-dependent phosphate transporter: functional characterisation in Escherichia coli*, J. Biol. Chem., 283, 13520–13527, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M709371200, 2008.

Pinzari, F., Cuadros, J., Jungblut, A. D., Najorka, J., and Humphreys-Williams, E.: Fungal strategies of potassium extraction from silicates of different resistance as manifested in differential weathering and gene expression, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 316, 168–200, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.10.010, 2022.

Poinar, G. O. and Buckley, R.: Evidence of mycoparasitism and hypermycoparasitism in Early Cretaceous amber, Mycol. Res., 111, 503–506, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mycres.2007.02.004, 2007.

Prestin, K., Wolf, S., Feldtmann, R., Hussner, J., Geissler, I., Rimmbach, C., Kroemer, H. K., Zimmermann, U., and Meyer zu Schwabedissen, H. E.: Transcriptional regulation of urate transportosome member SLC2A9 by nuclear receptor HNF4α, Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol., 307, F1041-1051, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00640.2013, 2014.

R Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, version 4.3.2 [code], https://www.R-project.org/ (last access: 10 January 2024), 2023.

Ruytinx, J., Craciun, A. R., Verstraelen, K., Vangronsveld, J., Colpaert, J. V., and Verbruggen, N.: Transcriptome analysis by cDNA-AFLP of Suillus luteus Cd-tolerant and Cd-sensitive isolates, Mycorrhiza, 21, 145–154, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-010-0318-2, 2011.

Ruytinx, J., Coninx, L., Nguyen, H., Smisdom, N., Morin, E., Kohler, A., Cuypers, A., and Colpaert, J. V.: Identification, evolution and functional characterization of two Zn CDF-family transporters of the ectomycorrhizal fungus Suillus luteus, Environ. Microbiol. Rep., 9, 419–427, https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-2229.12551, 2017.

Ruytinx, J., Coninx, L., Op De Beeck, M., Arnauts, N., Rineau, F., and Colpaert, J.: Adaptive zinc tolerance is supported by extensive gene multiplication and differences in cis-regulation of a CDF-transporter in an ectomycorrhizal fungus, Adapt. Zinc Toler. Support. Extensive Gene Mult. Differ. Cis-Regul. CDF-Transp. Ectomycorrhizal Fungus, https://doi.org/10.1101/817676, 2019.