the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Depth-dependent loss of microbiome diversity and Firmicutes compositional shift induced by ureolytic biostimulation in Aridisols

Kesem Abramov

Svetlana Gelfer

Michael Tsesarsky

Hadas Raveh-Amit

Soil microbiomes regulate biogeochemical cycles and fulfill essential ecosystem functions, particularly in arid environments. One beneficial function of various edaphic microbes is the ability to participate in the precipitation of calcium carbonate. Microbial Induced Calcite Precipitation (MICP) is a biomineralization process that has been extensively investigated as a soil improvement technique for various purposes, including mitigating drought-related soil degradation and controlling erosion. One aspect seldom addressed in MICP studies is the microbial heterogeneity of the ecosystem in which it is applied and its post-treatment consequences. In this study, we examined MICP biostimulation rates in an Aridisol, considering the microbial heterogeneity across different soil depths relevant to surface reinforcement applications (from the topsoil to 1 m below the surface). Biostimulation was achieved by inducing ureolysis, one of the most studied metabolic pathways to stimulate MICP. We characterized the native microbial communities and their response to biostimulation across the depths under consideration using 16S sequencing. We found that ureolysis rates were affected by soil depth, with higher rates detected in the topsoil. Before biostimulation, the native soils were dominated by Actinobacteria and contained diverse communities. The microbial communities of the deeper soil layers were richer in Firmicutes, and the deepest layer was less diverse than the topsoil. Following biostimulation, alpha-diversity and microbial richness were drastically reduced at all depths, resulting in homogenized communities dominated by Firmicutes, although microbial DNA concentrations increased. A notable decrease was detected in autotrophs (e.g., Cyanobacteria, Chloroflexi), which are important for the formation and function of biocrusts and, hence, to the entire ecosystem. We also found that biostimulation led to a shift in the composition of the Firmicutes phylum, where specific members of the Planococcaceae family became the most prevalent Firmicutes, replacing Paenibacillaceae and Bacillaceae as the dominant families. Our findings demonstrate that environmental heterogeneity across soil depth is an influential variable affecting ureolytic biostimulation. In turn, biostimulation affects microbial diversity consistently, regardless of preexisting differences resulting from spatial heterogeneity. Although feasible, implementing biostimulated MICP in arid environments induces a strong selective pressure with negative consequences for the native edaphic microbiomes.

- Article

(3565 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Soil microorganisms, and particularly soil bacteria, are a major component of Earth's biodiversity (Delgado-Baquerizo et al., 2018; Sokol et al., 2022). They are key regulators of biogeochemical cycles (Chen et al., 2017; Falkowski et al., 2008; Lal, 2008) with unquantifiable contributions to central ecological functions, including nutrient and carbon cycling, water retention, and primary production, among many others (Castillo-Monroy et al., 2010; Delgado-Baquerizo et al., 2014, 2018; Maestre et al., 2013). In arid regions, where plant cover is sparse, biocrusts – a diverse community in the soil surface – create a “living skin” that mediates most inputs, transfers, and losses across the soil surface and stabilizes the soil (Weber et al., 2022). Prokaryotes, notably cyanobacteria, constitute a key group in these arid biocrusts (Belnap and Lange, 2003).

Soil microbial communities in arid and semi-arid environments exhibit strong vertical stratification, driven by steep environmental gradients. Surface layers (0–5 cm) typically harbor the highest microbial diversity, dominated by phototrophic and heterotrophic organisms such as cyanobacteria, actinobacteria, and fungi, which are well adapted to desiccation, ultraviolet radiation, and rapid shifts in temperature and moisture (Pointing and Belnap, 2012; Steven et al., 2013). Subsurface soils (5–30 cm and deeper) tend to exhibit reduced richness and compositional shifts toward oligotrophic taxa that can survive under limited energy and carbon availability (Fierer et al., 2003a; Barnard et al., 2013). While microbial biomass and activity decrease with depth, subsurface communities may exhibit functional specialization, including resilience to long-term dormancy and adaptation of metabolic pathways.

Anthropogenic soil erosion may lead to changes in soil biodiversity, essential ecosystem traits, and impact human well-being (Delgado-Baquerizo et al., 2014; Maestre et al., 2013; Rodriguez-Caballero et al., 2022). In arid climates, chemical-physical soil surface stabilization is an alternative to plant cover (Durán Zuazo and Pleguezuelo, 2008) for mitigating soil erosion. Microbial Induced Calcite Precipitation (MICP) is a biomineralization process that is intensively studied as a possibly environmentally conscious ground improvement technique (DeJong et al., 2013; Gomez et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2019) with applications across environmental and engineering domains (DeJong et al., 2022). One key target for MICP-based applications is stabilization of the topsoil, where biological soil crusts play a crucial ecological role. In disturbed or degraded soils, MICP offers a synthetic analogue to these natural crusts, potentially restoring or enhancing surface cohesion. It has been proposed for various applications, including mitigating drought-related desiccation cracking (Liu et al., 2024), slope stabilization (Ghasemi and Montoya, 2022b), and reducing hazardous dust emissions from mine tailings (Fan et al., 2020).

Various microorganisms are capable of precipitating calcite through several metabolic pathways (Castanier et al., 1999; Castro-Alonso et al., 2019). Urea hydrolysis by the enzyme urease is one of the most studied pathways to induce MICP due to its high efficiency (De Muynck et al., 2010). Ureolytic MICP is usually achieved through one of two approaches: the biostimulation MICP approach harnesses the ability of many indigenous soil microorganisms to degrade urea. In contrast, the bioaugmentation approach relies on adding exogenous microbial biomass, most commonly cultures of the ureolytic Firmicute Sporosarcina pasteurii (Graddy et al., 2021; Whitaker et al., 2018). Both approaches require inputs of urea and an organic carbon source to stimulate urea hydrolysis efficiently (Gat et al., 2014, 2016; Graddy et al., 2021). Experiments using various medium compositions have been conducted across a range of setups, including incubation experiments, soil column rinsing, and field-scale studies (Gat et al., 2016; Gomez et al., 2018, 2019; Ghasemi and Montoya, 2022a; Ghasemi and Montoya, 2022b; Graddy et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2019; Ohan et al., 2020). Hereafter, we refer to the application of urea and an organic carbon source to induce ureolysis as ureolytic biostimulation.

Recent studies have established the feasibility of applying MICP in Aridisols by stimulating indigenous microorganisms (Raveh-Amit and Tsesarsky, 2020; Raveh-Amit et al., 2024). The treatment resulted in considerable reinforcement of the soil surface, as manifested by decreased desiccation cracking and increased calcite contents. However, there is a scarcity of knowledge regarding the effectiveness of biostimulation using different microbiomes. Spatial heterogeneity, and vertical heterogeneity in particular, may result in varying effectiveness of MICP, since soil depth is one of the important drivers of microbial abundance and community structure (Fierer et al., 2003a). Bacterial abundance tends to concentrate at the soil surface and decrease with increasing depth (Eilers et al., 2012; Fierer et al., 2003b; He et al., 2022), while archaea become more abundant in deeper soil horizons (Jiao et al., 2018). Both groups exhibit depth-related variation in taxonomic compositions (Eilers et al., 2012; Jiao et al., 2018), which might translate to variable ureolytic and precipitation capacities. Biostimulation of varying intensity was reported in soil excavated from large depths relevant to geotechnical applications (2–12 m below the surface; Gomez et al., 2018). Since the microbial cell density was not correlated with the intensity of the ureolytic response, the authors postulated that microbiome heterogeneity underlies these findings, which was not further examined. Compared with conventional ground improvement methods (e.g., grouting materials), MICP is commonly considered an environmentally friendly alternative. However, the actual impacts of MICP implementation on the ecosystem and biodiversity are not widely addressed. As Graddy and colleagues importantly emphasized (2021), MICP studies often under-characterize the microbial community on which the experimental system is based, which leads to missing crucial information required for successful implementation. The few studies that did address the environmental consequences of MICP application reported profound alterations in the composition of the native microbial communities, releases of substantial amounts of ammonium, and changes in the pH of the treated medium (Gat et al., 2016; Gomez et al., 2019; Graddy et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2019; Ohan et al., 2020). Considering their roles in essential processes, such drastic alterations of the edaphic microbial diversity may result in negative consequences for the ecosystem functions and services (Bahram et al., 2018; Philippot et al., 2023). Nevertheless, the application of MICP is rapidly expanding to field-scale applications without considering the complexity of natural microbiomes or environmental effects.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the consequences of ureolytic biostimulation on the microbiome level in Aridisol. Specifically, we study soils from the Negev Desert (Israel) to: (i) characterize the native microbial community at depths relevant to soil surface stabilization and down to 1 m depth; (ii) establish the efficiency of ureolytic biostimulation using native microbiomes, and (iii) study the effects of the treatment on microbial diversity. Considering the possible environmental outcomes of MICP application and the vulnerability of desert ecosystems to disturbances, an incubation experiment was conducted in a controlled laboratory environment, using samples of native soils. Focusing on vertical variability, we used 16S sequencing to study the native prokaryotic communities when subjected to ureolytic biostimulation. We studied the course and efficiency of ureolysis in treated soils and monitored their pH during biostimulation. Then, we investigated possible relationships between the observed patterns in ureolysis and microbial diversity, and suggested potential mechanisms that underlie these relationships.

2.1 Soil sampling and chemical–physical characterization

We sampled soils from three sites in the Rotem Plateau (31.03° N, 35.09° E), northern Negev Desert, Israel. It is an arid region with an average annual rainfall of 70 mm, covered with low organic carbon (<0.1 %) Aridisol (Soil Survey Staff, 1999). The study sites, from which soils were sampled for biostimulation experiments, included two non-disturbed sites (referred here as site 1 and site 2), located 4.1 km apart. To examine the impact of mechanical disturbance on the ureolytic response, biostimulation experiments were performed on soils from a third, disturbed site (located 3 km away). The site was subjected to mechanical disturbance approximately 20 years before this study, during which a ditch was excavated and then filled with the excavated soil. Within each site, soil was sampled using a sterilized 2.75 in (70 mm) hand auger, from three depths: topsoil at 5, 50, and 100 cm below the surface. These depths were sampled in duplicates within each site, with approximately 10 m separating the replicates. The microbial communities of the soils of sites 1 and 2 were chosen for characterization using 16S DNA sequencing (overall, n=12 samples representing native Negev soil), as described in Sect. 2.3. All samples were stored at 4 °C until the biostimulation experiments began.

Elemental composition by X-ray fluorescence (XRF), mineralogical phase identification by X-ray diffraction (XRD), and particle size distribution (PSD) analyses were performed on the soil samples as described by Raveh-Amit and Tsesarsky (2020). The two sites comprise medium to coarse sand (D50 of 0.25 and 0.44 mm), with a high calcium content of 14 % and 40 % (by weight) for soil 1 and 2, respectively. The soil's pH before biostimulation was measured by suspending 1 g of soil in 10 mL of deionized water using a Metrohm pH meter (Metrohm, Herisau, Switzerland), yielding a value of 7.8±0.1.

2.2 Biostimulation of indigenous ureolytic microbes and chemical analysis

This study examined the response of edaphic microbiomes to the chemical solution composition that is the common ground to MICP experiments at various scales, as considerable shifts in microbial diversity and medium properties reported in previous studies stemmed from varied setups and media compositions (Gomez et al., 2018, 2019; Ghasemi and Montoya, 2022a; Ghasemi and Montoya, 2022b; Graddy et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2019; Ohan et al., 2020). A prior study has shown that the characteristic biostimulation response – a marked pH increase, ureolysis, and dominance of Firmicutes – requires both urea and an organic carbon source (Gat et al., 2016). Accordingly, our study employed a `before and after' design, where biostimulation was performed by incubating 10.0 g of each soil sample in 100 mL of a medium containing 20 g L−1 (330 mM) urea and 1 g L−1 of yeast extract at ambient temperature with gentle shaking at 100 rpm for 10 d (n=12 biostimulated samples intended for sequencing). The medium solution was filter-sterilized by disposable 0.22 µm Millex® syringe filters (Kenilworth, NJ) before the addition of yeast extract. To monitor biostimulation during the course of the experiment, we sampled the stimulation medium of each sample periodically and measured its pH and urea concentration. pH was measured using a Metrohm pH meter (Metrohm, Herisau, Switzerland). Urea concentrations were measured according to the Knorst colorimetric method (Knorst et al., 1997), with minor modifications, on an 8453 Agilent spectrophotometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

2.3 Soil microbial DNA extraction and 16S amplicon sequencing

To examine the response of the microbial communities of different soil depths to ureolytic stimulation, we extracted DNA from soil sampled from specific depths in sites 1 and 2, before and after the biostimulation experiment. DNA samples were extracted in triplicate using the Powersoil Pro kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). DNA extracts were eluted in Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) at room temperature and immediately stored at 4 °C. DNA quality control (QC) was performed by a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Library preparation and 16S amplicon sequencing were designed and performed by Qiagen Genomic Services (Hilden, Germany). Libraries were prepared using QIAseq 16S/ITS 7 regions Screening Panel using primers designed to amplify the variable regions by binding to the conserved regions of the 16S segment. Library QC and quantification were carried out using Agilent TapeStation or Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), depending on sample number, and by QIAseq Library Quant Array, respectively. Amplicons were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform using reagent kits v3 (extended paired-end reads of up to 2×300 bp). Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) assignment and clustering were carried out on the CLC Microbial Genomics module on the CLC Genomics Work Bench, setting the similarity percentage parameter to 97 %. The reference database used was SILVA 16S v132 97 %. Raw sequences were uploaded to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive and are available under bioproject ID PRJNA1041873.

2.4 Sequence data and statistical analysis

Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) and statistical analyses were performed using RStudio v2023.03.0 (R Core Team, 2023) on the v4v5 region. We used ANOVA and pairwise (Bonferroni corrected) tests to compare the amount of DNA extracted from the different depths and the biostimulated and non-treated soils, as well as to compare OTU diversity (using Shannon's index and Chao1 richness) of the prokaryotic communities, beta diversity, and prevalence of specific taxa. The data was log-transformed when the assumption of equal variances was not met, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was applied when the data violated the assumption of normal distribution. We used Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to illustrate the distances between the communities of the compared soil samples based on Bray-Curtis distances calculated for relative abundances of the OTUs. An Analysis of Similarities (ANOSIM) test was then performed to determine the significance of differences between the communities' taxonomic structures. Additionally, a Similarity Percentage analysis (SIMPER) was used to assess which identified OTUs contributed most to the variance between samples. Values along the results section represent means, and the presented errors are standard deviations.

We plotted the measured urea concentrations and the change in pH during the biostimulation process to create reaction profiles for each sampling depth. The significance of the change in these variables during the experiment was examined using repeated-measures ANOVA.

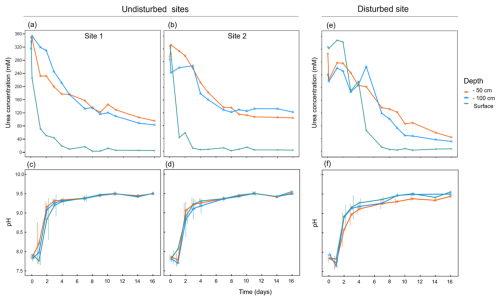

3.1 Depth-Dependent Ureolytic Performance

Ureolytic activity was successfully induced by the biostimulation treatment in soil samples from different depths (Fig. 1). The measured urea concentration significantly decreased during the days following the treatment (repeated measures ANOVA; , ). The ureolysis levels differed between soils from different depths (, ). At the soil surface, urea was completely depleted within approximately 5 d following the treatment in sites 1 and 2. In the deeper soils, ureolysis rates were milder than in the topsoil and complete urea depletion was not achieved even after 18 d of the treatment (Fig. 1a and b). The course of ureolytic response at the two greater depths was similar (paired t-test: t41=1.45, P=0.465).

Figure 1Ureolytic activity profiles and pH changes following ureolytic biostimulation in three soil layers at different sampling sites: (a, c) site 1, (b, d) site 2, and (e, f) a site that was mechanically disturbed 20 years ago.

At the disturbed site, the ureolytic response was delayed in comparison to the other sites, with complete urea depletion at the soil surface a week from the beginning of the experiment (Fig. 1e). Moreover, higher hydrolysis rates were recorded at the deeper soils at this site (46.64±10.39 mM urea measured after 18 d) in comparison to sites 1 and 2 (94.97±28.56 mM urea measured after 18 d). Lower hydrolysis rates at the surface, combined with higher rates at the deeper layers, might indicate that decades after the harsh disturbance, the amalgamation of soil layers is still reflected in the microbial community of the disturbed site. The surface community that plays a crucial functional role has apparently not yet recovered. Indeed, biocrusts are known to be highly sensitive to disturbances and are characterized by notoriously slow recovery rates (Belnap and Eldridge, 2001). Although the ability to distinguish the effect of disturbance from other influential factors is limited in environmental studies, our results suggest there are functional consequences of mechanical disturbance to the soil microbiome.

The pH of the treated soils drastically increased during the experiment in accordance with urea hydrolysis (Fig. 1c, d, and f), elevating from 7.85±0.08 to 8.92±0.29 after 48 h and then stabilizing at pH 9.46±0.05 until experiment termination. These changes were consistent among soils from different depths and sites (repeated measures ANOVA; , P=0.943). Such changes in the chemical properties of MICP-treated soil pore fluids, even over a limited time, may have considerable environmental consequences. For instance, soil pH was identified as one of the most important factors that shape microbial communities (Fierer, 2017; Ratzke and Gore, 2018). The above-described processes are constrained by our experimental design aimed to follow the bio-stimulation phase of the MICP process. Hence, its duration was limited to 16 d. In a long-term bio-stimulation experiment (Gat, Ronen et al., 2016), with a similar experimental setup, the pH evolution of the medium was monitored for six months following the stimulation phase. It showed that a gradual decline follows the initial increase in pH, ultimately converging to control levels of untreated (water only) samples. Although derived from an incubation experiment, these results show long-term soil buffering capacity and should be considered in future field experiments.

3.2 Biostimulation-Induced Shifts in Microbial Communities Along Soil Depth Gradient

We extracted microbial DNA and performed 16S amplicon sequencing to assess the effect of the treatment on the diversity of native prokaryotes in soils from different depths. The analysis yielded a total of 877 848 reads that were assigned to 7650 OTUs, with an average of 36 577±20 701 reads per sample. These OTUs belonged to 27 bacterial phyla and two archaeal phyla.

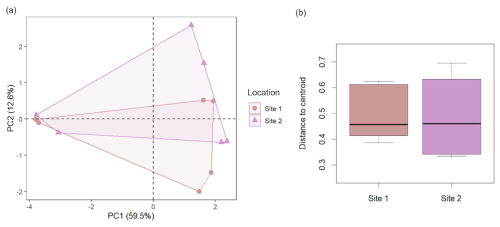

To study the differences in the responses of microbiomes of different depths to biostimulation, we first compared the two study sites to account for any occurring horizontal spatial variation. Before treatment, the two sites did not differ in their overall local microbial diversity (, P=0.13) nor beta-diversity (Fig. 2), hosting similar communities without clear compositional distinctions (ANOSIM: , P=0.56). The communities of both sites were similarly affected by the treatment, as will be discussed below. Therefore, the analysis focused on depth and treatment-related effects.

Figure 2Beta-diversity comparison between the two study sites. (a) PCA based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities shows that the microbiome composition of the two sampling sites highly overlaps. (b) Beta-diversity of the untreated samples does not significantly differ between the two sites (one-way ANOVA: , P=0.96).

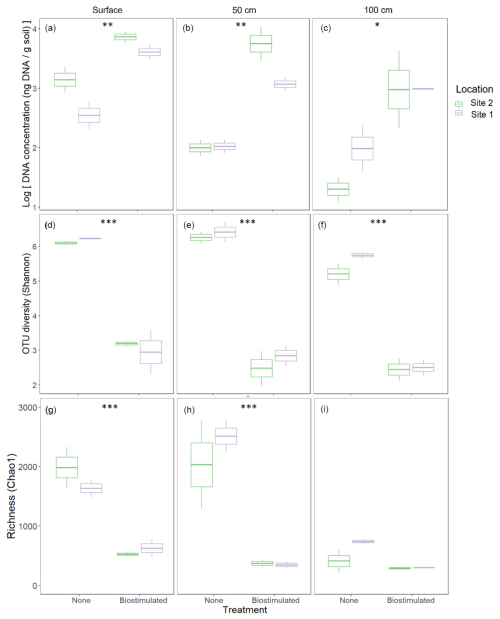

3.2.1 Local microbial diversity

Upon DNA extraction, it was noticeable that the amount of microbial DNA extracted from biostimulated soils (30±15 ng DNA per g soil) was consistently higher than that of untreated soils (10.54±7.31 DNA per g soil; 2-way ANOVA: , ; Fig. 3a–c). Before the treatment, the native soils contained diverse communities (Fig. 3d–i), typical of hot desert soils (Walters and Martiny, 2020). Microbial diversity was higher in the upper soil layer compared to the microbial community at 100 cm depth (2-way ANOVA: , P=0.01). Following biostimulation, alpha-diversity (Fig. 3d–f) and microbial richness (Fig. 3g–i) were drastically diminished. These results were consistent across soil depths, despite the observed increase in the amount of microbial DNA. In the samples from 100 cm depth, the decrease following biostimulation was less drastic since the initial microbial richness was low. Nevertheless, given the higher initial ratio between the number of reads and richness, the decrease in diversity was also considerable in this layer.

Figure 3Effects of ureolytic biostimulation on edaphic microbial communities. Microbial DNA concentrations (a–c) extracted from the studied soils were higher in biostimulated compared to non-treated soils. However, microbial diversity (d–f) decreased following the treatment across depths (2-way ANOVA: , ), as well as OTU richness (, , g–i). Asterisks denote the significance level of the differences in the treatment's effect within a specific depth according to pairwise tests.

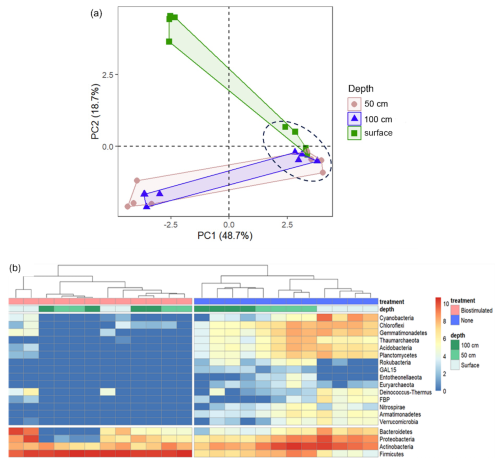

3.2.2 Microbial community composition

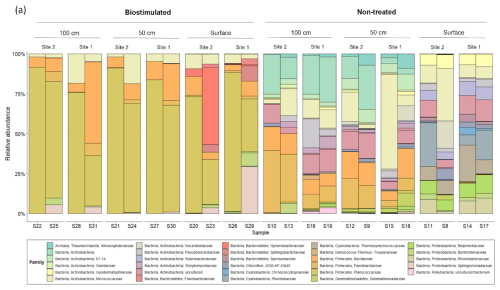

Communities at all depths were dominated by the rigid-walled, mostly chemoorganotrophic (Goodfellow, 2015) Actinobacteria (49.47±10.93 of total reads). The surface layer contained more Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Chloroflexi in comparison to the deeper layers (50 and 100 cm, refer to Fig. 4a; ANOSIM: R=0.87, P=0.0004). The communities of the deeper soils were richer in Firmicutes compared to the topsoil (Fig. 4b). These findings will be discussed in greater depth, with respect to the ureolytic response, in the last section of the Results and Discussion chapter. Composition-wise, the soils in the deeper layers hosted communities that were more similar to one another in comparison to the community of the surface. Nevertheless, significant differences were found between the communities of the greater depths (R=0.41, P=0.03). For instance, most of the Archaea populated the 50 cm deep layer (Fig. 4b). The observed shifts in microbial community composition likely result from vertical environmental gradients – specifically temperature, UV radiation, and oxygen availability – given that the particle size distribution and mineralogical composition remain largely consistent between surface and subsurface layers.

Figure 4Microbial diversity patterns in communities from different soil depths, before and after ureolytic biostimulation. (a) PCA based on OTU relative abundances at the different soil samples. The biostimulated soils are circled by a dashed black line. (b) A heatmap of the changes in the OTU counts (log transformed) of the main prokaryotic phyla between the studied soil samples (columns). The phylogenetic tree represents the similarity between the composition of sample communities based on Euclidean distances.

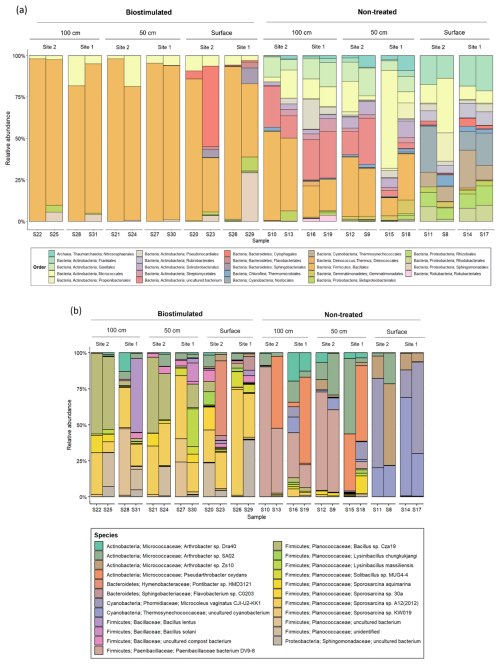

The loss of biodiversity following biostimulation was mainly derived from a drastic increase in the proportions of the endospore-forming Firmicutes at the expense of many other taxa (Fig. 4b). Biostimulation thus resulted in homogenized communities, which no longer differed between depths (R=0.13, P=0.17) and were all dominated solely by this phylum (80.39±21.41 % of all reads in treated soils in comparison to 11.20±9.89 % in untreated soils). Particularly, the treated soils were dominated by the firmicute family Planococcaceae (Fig. A1), to which the most frequently studied model bacterium in MICP experiments, S. pasteurii, belongs. Several additional taxa remained prevalent after the treatment, mainly Micrococcales (Actinobacteria; Fig. 5).

Figure 5The composition of the most prevalent microbial (a) orders (above 1 % of total reads) and (b) specific OTUs (above 5 % of total reads) in studied soil depths, before and after ureolytic biostimulation.

Our results emphasize the robustness of MICP, as substantial and rapid urea hydrolysis can be obtained using distinct microbiomes from different soil depths. Nevertheless, they show that applying this technique to soils comes with an ecological cost. The proliferation of Firmicutes following ureolytic stimulation has been reported in several previous studies on MICP (Gat et al., 2016; Graddy et al., 2021; Ohan et al., 2020) as well as in a study on agricultural-related nitrogen amendments (Kaminsky et al., 2021). This might be attributed to their physiological abilities to cope with the applied selection pressure (i.e., urea addition and the rapid increase in pH following ureolysis) and even utilize the new niche, with reduced competition, to flourish. Nevertheless, the fate of other populations, that are not recognized as ureolytically beneficial, remains largely unaddressed. Our results show that many of the native residents are suppressed by the treatment, leaving only 13 of the 29 phyla that were initially detected. Notably, the treatment dramatically decreased the amount of detected autotrophs (e.g., Cyanobacteria, Chloroflexi), which are extremely important to the formation and function of biocrusts (Maier et al., 2018), and hence to the entire ecosystem (Belnap, 2002; Maestre et al., 2011; Rodriguez-Caballero et al., 2022; Rutherford et al., 2017). Inspecting higher resolution changes in the taxonomic structure of the communities (Fig. 5) revealed that specific bacteria that are crucial for the establishment of biocrusts (Xu et al., 2020), and in the Negev in particular (Belnap and Lange, 2003) – Nostocales (Fig. 5a) and Microcoleus vaginatus (Fig. 5b) – are not detected in treated soils, which would likely suppress biocrust recovery. Additional functionally important groups that were suppressed by biostimulation are ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria, including Thaumarchaeota and Nitrospirae (Marusenko et al., 2015; Fig. 4b).

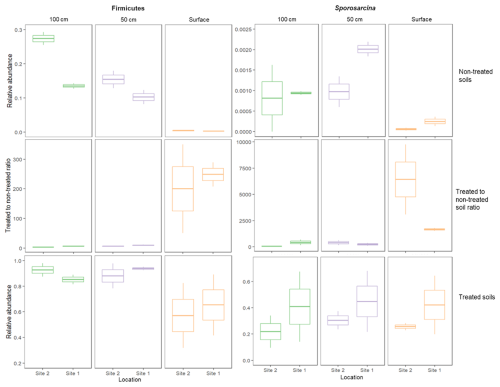

The shift in taxonomic composition was also noticeable within the Firmicutes and other surviving phyla (Fig. A1). At the same time, in the untreated soils, the main Firmicute families were Paenibacillaceae and Bacillaceae, the treated soils were dominated by Planococcaceae. Our analysis identified two specific bacterial taxa that were prominently abundant in biostimulated soils. They were annotated as Sporosarcina sp. A12(2012) and Bacillus sp. Cza19 (Fig. 5b). Both are classified at the SILVA database as members of the family Planococcaceae. Combined, these two OTUs contributed 18.9 % of the variance between the communities of treated and non-treated soils (SIMPER analysis). Our results support the findings of Graddy et al. (2021), showing a clear convergence of bacterial communities in biostimulation and augmentation experiments. In both forms, MICP has a deterministic and consistent effect on the microbial communities, regardless of preexisting structural differences.

3.3 The relationship between the ureolytic response, microbial diversity, and spatial heterogeneity

The heterogeneity of the ecosystem in which ureolytic biostimulation is applied is rarely addressed in MICP studies. Our findings support the notion that environmental heterogeneity and microbiome composition are influential variables that should be considered in MICP experiments and applications. In sites 1 and 2, soil depth had a strong influence on the composition of the microbiome (Fig. 4) and hence on the ureolytic response (Fig. 1). In contrast, horizontal variance did not (Fig. 2). These findings agree with the results of a previous study (Eilers et al., 2012), in which the effect of soil depth on the microbiome composition in samples within a specific forested biome was found to be equivalent, or even stronger, than the differences between samples from similar depths obtained from a wide range of ecosystems. Conversely, in the mechanically disturbed site, the disturbance itself appeared to play a dominant role, as evidenced by a delayed ureolytic response near the surface and a stronger activity in the deeper layers relative to two adjacent undisturbed sites. Taken together, our study shows that environmental variability affects the efficiency of MICP and that MICP, in turn, detrimentally impacts the microbial diversity regardless of preexisting differences resulting from spatial heterogeneity. Despite being drawn from a laboratory experiment, our results thus stress the importance of studying biostimulation in the context of different biotic and abiotic variables that operate on the native microbial community in order to analyze and forecast its efficiency.

The consistent proliferation of Firmicutes in MICP studies leads to the reasonable assumption that Firmicutes (and particularly highly ureolytic species such as S. pasteurii) are the engine behind the ureolytic response. Our results interestingly indicate that the process involves greater complexity, since the intensity of the ureolytic response cannot be predicted solely by the preexisting amount of Firmicutes in the soil; Although most of the Firmicutes and Sporosarcina members in our study sites were originally concentrated in the deeper layers of soil (Figs. 4b and A2), and although their relative abundances (Fig. A2) and total microbial DNA concentration increased similarly across the different depths following biostimulation (Fig. 2a–c), the ureolytic response was not uniform. Urea degradation rates were higher at the soil surface and decreased in deeper soils (Fig. 1a–c). The stronger response at the surface was documented despite being measured at identical laboratory conditions of light, temperature, available oxygen, etc. Hence, it is possible that a consortium of microbes contributes to the ureolytic process, either by: (i) directly engaging in ureolysis or (ii) turning into an additional carbon source in the form of microbial necromass, which fuels the rapid response upon cell mortality, if induced by the treatment.

Considering the essential functions of the upper layer of soil in arid environments and its vulnerability, our findings call for taking precautions when considering the application of MICP in arid habitats. Nevertheless, our results capture a short-term time frame of the treatment's effect. Kaminsky and her colleagues (2021) have reported similar impacts of urea amendments on microbial diversity, yet they also found some recovery trends seven weeks after the treatment. To our knowledge, the succession of the microbial community over time following MICP was never monitored in previous studies. Considering the central functions of microbiomes in biogeochemical cycles and the evidence of functional effects, this issue should be addressed in future studies.

In this study, we demonstrated the feasibility of inducing effective ureolytic biostimulation using native microbiomes that inhabit different depths within the upper 1 m of Aridisols. Effective ureolysis was achieved at the depths of interest, regardless of the preexisting differences between the microbial communities. However, vertical microbial heterogeneity influenced the intensity of the ureolytic response, with depth-dependent variations likely reflecting differences in functional potential and environmental constraints.

While biostimulated MICP shows promise for stabilizing soil surfaces in arid environments, our results highlight potential ecological trade-offs. Specifically, the treatment consistently altered microbial community composition, enriching specific heterotrophic taxa while suppressing autotrophs and other functionally important groups. Given that autotrophs are central to the integrity of biological soil crusts, their decline may undermine long-term soil stability and ecosystem function.

Taken together, these findings underscore the importance of incorporating environmental heterogeneity and microbial biodiversity into the design and assessment of MICP-based interventions. Future studies should evaluate both the engineering effectiveness and the ecological consequences of biostimulation in arid soils to ensure sustainable implementation.

Figure A1The composition of the most prevalent (above 1 % of total reads) microbial families in the studied soil depths, before and after ureolytic biostimulation.

Figure A2Relative abundances of the phylum Firmicutes and of the genus Sporosarcina in soils before ureolytic biostimulation and after the treatment, and the ratio between them. The relative abundance of Firmicutes reached similar values in treated soils (2-way ANOVA: , P=0.08), as did the Sporosarcina (, P=0.93) despite their original higher proportions in the deeper soils in comparison to the surface.

The raw 16S sequences were uploaded to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive and are available under bioproject ID no. PRJNA1041873 (https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1041873?reviewer=stgmv3s8utnp6gaqr81hm43p55 (last access: 15 December 2025).

KA: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing – original draft preparation, writing – review and editing. SG: investigation and formal analysis. MT: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, writing – review and editing. HRA: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, writing – review and editing.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This research was funded by the Pazy Foundation (grant no. 304/22). We thank Inbar Gal, Shir Keret, Ido Grinshpan, and Ariel Kushmaro for their assistance throughout the study.

This research has been supported by the PAZY Foundation (grant no. 304/22).

This paper was edited by Anja Rammig and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Bahram, M., Hildebrand, F., Forslund, S. K., Anderson, J. L., Soudzilovskaia, N. A., Bodegom, P. M., Bengtsson-Palme, J., Anslan, S., Coelho, L. P., Harend, H., Huerta-Cepas, J., Medema, M. H., Maltz, M. R., Mundra, S., Olsson, P. A., Pent, M., Põlme, S., Sunagawa, S., Ryberg, M., Tedersoo, L., and Bork, P.: Structure and function of the global topsoil microbiome, Nature, 560, 233–237, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0386-6, 2018.

Belnap, J.: Nitrogen fixation in biological soil crusts from southeast Utah, USA, Biol. Fertil. Soils, 35, 128–135, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-002-0452-x, 2002.

Belnap, J. and Eldridge, D.: Disturbance and Recovery of Biological Soil Crusts, in: Biological Soil Crusts: Structure, Function, and Management, 363–383, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-56475-8_27, 2001.

Belnap, J. and Lange, O. L.: Biological soil crusts: structure, function, and management, Ecological Studies, vol. 150, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, ISBN 3-540-43757-6, 2003.

Barnard, R. L., Osborne, C. A., and Firestone, M. K.: Responses of soil bacterial and fungal communities to extreme desiccation and rewetting, ISME Journal, 7, 2229–2241, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.104, 2013.

Castanier, S., Le Métayer-Levrel, G., and Perthuisot, J.-P.: Ca-carbonates precipitation and limestone genesis-the microbiogeologist point of view, Sedimentary Geology, 9–23, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0037-0738(99)00028-7, 1999.

Castillo-Monroy, A. P., Maestre, F. T., Delgado-Baquerizo, M., and Gallardo, A.: Biological soil crusts modulate nitrogen availability in semi-arid ecosystems: Insights from a Mediterranean grassland, Plant Soil, 333, 21–34, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-009-0276-7, 2010.

Castro-Alonso, M. J., Montañez-Hernandez, L. E., Sanchez-Muñoz, M. A., Macias Franco, M. R., Narayanasamy, R., and Balagurusamy, N.: Microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP) and its potential in bioconcrete: Microbiological and molecular concepts, Frontiers in Materials, 6, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2019.00126, 2019.

Chen, J., Xiao, G., Kuzyakov, Y., Jenerette, D., Liu, W., Wang, Z., and Shen, W.: Soil nitrogen transformation responses to seasonal precipitation changes are regulated by changes in functional microbial abundance in a subtropical forest, Biogeosciences, 14, 2513–2525, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-14-2513-2017, 2017.

Dejong, J. T., Soga, K., Kavazanjian, E., Burns, S., Van Paassen, L. A., AL Qabany, A., Aydilek, A., Bang, S. S., Burbank, M., Caslake, L. F., Chen, C. Y., Cheng, X., Chu, J., Ciurli, S., Esnault-Filet, A., Fauriel, S., Hamdan, N., Hata, T., Inagaki, Y., Jefferis, S., Kuo, M., Laloui, L., Larrahondo, J., Manning, D. A. C., Martinez, B., Montoya, B. M., Nelson, D. C., Palomino, A., Renforth, P., Santamarina, J. C., Seagren, E. A., Tanyu, B., Tsesarsky, M., and Weaver, T.: Biogeochemical processes and geotechnical applications: Progress, opportunities and challenges, Geotechnique, 63, 287–301, https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.SIP13.P.017, 2013.

DeJong, J. T., Gomez, M. G., San Pablo, A. C., Graddy, C. M., Nelson, D. C., Lee, M., Ziotopoulou, K., El Kortbawi, M., Montoya, B., and Kwon, T .: State of the Art: MICP soil improvement and its application to liquefaction hazard mitigation, 20th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, 2022.

Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Maestre, F. T., Escolar, C., Gallardo, A., Ochoa, V., Gozalo, B., and Prado-Comesaña, A.: Direct and indirect impacts of climate change on microbial and biocrust communities alter the resistance of the N cycle in a semi-arid grassland, Journal of Ecology, 102, 1592–1605, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12303, 2014.

Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Oliverio, A. M., Brewer, T. E., Benavent-González, A., Eldridge, D. J., Bardgett, R. D., Maestre, F. T., Singh, B. K., and Fierer, N.: A global atlas of the dominant bacteria found in soil, Science, 359, 320–325, 2018.

De Muynck, W., De Belie, N., and Verstraete, W.: Microbial carbonate precipitation in construction materials: A review, Ecological Engineering, 36, 118–136, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2009.02.006, 2010.

Durán Zuazo, V. H. and Rodríguez Pleguezuelo, C. R.: Soil erosion and runoff prevention by plant covers. A review, Agron. Sustain. Dev., 28, 65–86, https://doi.org/10.1051/agro:2007062, 2008.

Eilers, K. G., Debenport, S., Anderson, S., and Fierer, N.: Digging deeper to find unique microbial communities: The strong effect of depth on the structure of bacterial and archaeal communities in soil, Soil Biol. Biochem., 50, 58–65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.03.011, 2012.

Falkowski, P. G., Fenchel, T., and Delong, E. F.: The Microbial Engines That Drive Earth's Biogeochemical Cycles, Science, 320, 1034–1039, https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.1153213, 2008.

Fan, Y., Hu, X., Zhao, Y., Wu, M., Wang, S., Wang, P., Xue, Y., and Zhu, S.: Urease producing microorganisms for coal dust suppression isolated from coal: Characterization and comparative study, Advanced Powder Technology, 31, 4095–4106, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2020.08.014, 2020.

Fierer, N.: Embracing the unknown: Disentangling the complexities of the soil microbiome, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 15, 579–590, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.87, 2017.

Fierer, N., Schimel, J. P., and Holden, P. A.: Influence of drying–rewetting frequency on soil bacterial community structure, Microbial Ecology, 45, 63–71, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-002-1007-2, 2003a.

Fierer, N., Schimel, J. P., and Holden, P. A.: Variations in microbial community composition through two soil depth profiles, Soil Biol. Biochem., 35, 167–176, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0717(02)00251-1, 2003b.

Gat, D., Tsesarsky, M., Wahanon, A., and Ronen, Z.: Ureolysis and MICP with model and native bacteria: implications for treatment strategies, in: Geo-Congress 2014 Technical Papers: Geo-Characterization and Modeling for Sustainability – Proceedings of the 2014 Congress, vol. 234, Geotechnical Special Publication 234, American Society of Civil Engineers, 1713–1720, https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784413272.168, 2014.

Gat, D., Ronen, Z., and Tsesarsky, M.: Soil Bacteria Population Dynamics Following Stimulation for Ureolytic Microbial-Induced CaCO3 Precipitation, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 616–624, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b04033, 2016.

Ghasemi, P. and Montoya, B. M.: Effect of Treatment Solution Chemistry and Soil Engineering Properties due to Microbially Induced Carbonate Precipitation Treatments on Vegetation Health and Growth, ACS ES&T Engineering, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestengg.2c00196, 2022a.

Ghasemi, P. and Montoya, B. M.: Field Implementation of Microbially Induced Calcium Carbonate Precipitation for Surface Erosion Reduction of a Coastal Plain Sandy Slope, Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 148, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0002836, 2022b.

Gomez, M. G., Martinez, B. C., Dejong, J. T., Hunt, C. E., Devlaming, L. A., Major, D. W., and Dworatzek, S. M.: Field-scale bio-cementation tests to improve sands, Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Ground Improvement, 168, 206–216, https://doi.org/10.1680/grim.13.00052, 2015.

Gomez, M. G., Graddy, C. M. R., DeJong, J. T., Nelson, D. C., and Tsesarsky, M.: Stimulation of Native Microorganisms for Biocementation in Samples Recovered from Field-Scale Treatment Depths, Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 144, https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)gt.1943-5606.0001804, 2018.

Gomez, M. G., Graddy, C. M. R., DeJong, J. T., and Nelson, D. C.: Biogeochemical Changes During Bio-cementation Mediated by Stimulated and Augmented Ureolytic Microorganisms, Sci. Rep., 9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47973-0, 2019.

Goodfellow, M.: Actinobacteria phyl. nov., in: Bergey's Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria, Wiley, 1–2, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118960608.pbm00002, 2015.

Graddy, C. M. R., Gomez, M. G., Dejong, J. T., and Nelson, D. C.: Native Bacterial Community Convergence in Augmented and Stimulated Ureolytic MICP Biocementation, Environ. Sci. Technol., 55, 10784–10793, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c01520, 2021.

He, J., He, Y., Gao, W., Chen, Y., Ma, G., Ji, R., and Liu, X.: Soil depth and agricultural irrigation activities drive variation in microbial abundance and nitrogen cycling, Catena, 219, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106596, 2022.

Jiao, S., Chen, W., Wang, J., Du, N., Li, Q., and Wei, G.: Soil microbiomes with distinct assemblies through vertical soil profiles drive the cycling of multiple nutrients in reforested ecosystems, Microbiome, 6, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0526-0, 2018.

Kaminsky, L. M., Esker, P. D., and Bell, T. H.: Abiotic conditions outweigh microbial origin during bacterial assembly in soils, Environ. Microbiol., 23, 358–371, https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.15322, 2021.

Knorst, M. T., Neubert, R., and Wohlrab, W.: Analytical methods for measuring urea in pharmaceutical formulations, Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 15, 1627–1632, 1997.

Lal, R.: Sequestration of atmospheric CO2 in global carbon pools, Energy Environ. Sci., 1, 86–100, https://doi.org/10.1039/b809492f, 2008.

Lee, M., Gomez, M. G., San Pablo, A. C. M., Kolbus, C. M., Graddy, C. M. R., DeJong, J. T., and Nelson, D. C.: Investigating Ammonium By-product Removal for Ureolytic Bio-cementation Using Meter-scale Experiments, Sci. Rep., 9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54666-1, 2019.

Liu, B., Tang, C.-S., Pan, X.-H., Xu, J.-J., and Zhang, X.-Y.: Suppressing Drought-Induced Soil Desiccation Cracking Using MICP: Field Demonstration and Insights, Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 150, https://doi.org/10.1061/JGGEFK.GTENG-12011, 2024.

Maestre, F. T., Bowker, M. A., Cantón, Y., Castillo-Monroy, A. P., Cortina, J., Escolar, C., Escudero, A., Lázaro, R., and Martínez, I.: Ecology and functional roles of biological soil crusts in semi-arid ecosystems of Spain, J. Arid Environ., 75, 1282–1291, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.12.008, 2011.

Maestre, F. T., Escolar, C., de Guevara, M. L., Quero, J. L., Lázaro, R., Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Ochoa, V., Berdugo, M., Gozalo, B., and Gallardo, A.: Changes in biocrust cover drive carbon cycle responses to climate change in drylands, Glob. Chang. Biol., 19, 3835–3847, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12306, 2013.

Maier, S., Tamm, A., Wu, D., Caesar, J., Grube, M., and Weber, B.: Photoautotrophic organisms control microbial abundance, diversity, and physiology in different types of biological soil crusts, ISME Journal, 12, 1032–1046, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0062-8, 2018.

Marusenko, Y., Garcia-Pichel, F., and Hall, S. J.: Ammonia-oxidizing archaea respond positively to inorganic nitrogen addition in desert soils, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 91, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiu023, 2015.

Ohan, J. A., Saneiyan, S., Lee, J., Bartlow, A. W., Ntarlagiannis, D., Burns, S. E., and Colwell, F. S.: Microbial and Geochemical Dynamics of an Aquifer Stimulated for Microbial Induced Calcite Precipitation (MICP), Front. Microbiol., 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01327, 2020.

Philippot, L., Chenu, C., Kappler, A., Rillig, M. C., and Fierer, N.: The interplay between microbial communities and soil properties, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 22, 226–239, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00980-5, 2023.

Pointing, S. B., and Belnap, J.: Microbial colonization and controls in dryland systems, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 10, 551–562, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2831, 2012.

Ratzke, C. and Gore, J.: Modifying and reacting to the environmental pH can drive bacterial interactions, PLoS Biol., 16, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2004248, 2018.

Raveh-Amit, H. and Tsesarsky, M.: Biostimulation in desert soils for microbial-induced calcite precipitation, Appl. Sci.-Basel, 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/APP10082905, 2020.

Raveh-Amit, H., Gruber, A., Abramov, K., and Tsesarsky, M.: Mitigation of aeolian erosion of loess soil by Bio-Stimulated microbial induced calcite precipitation, Catena, 237, 107808, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2024.107808, 2024.

R Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.R-project.org/ (last access: 15 December 2025), 2023.

Rodriguez-Caballero, E., Stanelle, T., Egerer, S., Cheng, Y., Su, H., Canton, Y., Belnap, J., Andreae, M. O., Tegen, I., Reick, C. H., Pöschl, U., and Weber, B.: Global cycling and climate effects of aeolian dust controlled by biological soil crusts, Nat. Geosci., 15, 458–463, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-022-00942-1, 2022.

Rutherford, W. A., Painter, T. H., Ferrenberg, S., Belnap, J., Okin, G. S., Flagg, C., and Reed, S. C.: Albedo feedbacks to future climate via climate change impacts on dryland biocrusts, Sci. Rep., 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44188, 2017.

Soil Survey Staff: Soil taxonomy: A basic system of soil classification for making and interpreting soil surveys, 2nd edn., Natural Resources Conservation Service, US Department of Agriculture, Handbook 436, https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/resources/guides-and-instructions/soil-taxonomy (last access: 15 December 2025), 1999.

Sokol, N. W., Slessarev, E., Marschmann, G. L., Nicolas, A., Blazewicz, S. J., Brodie, E. L., Firestone, M. K., Foley, M. M., Hestrin, R., Hungate, B. A., Koch, B. J., Stone, B. W., Sullivan, M. B., Zablocki, O., Trubl, G., McFarlane, K., Stuart, R., Nuccio, E., Weber, P., Jiao, Y., Zavarin, M., Kimbrel, J., Morrison, K., Adhikari, D., Bhattacharaya, A., Nico, P., Tang, J., Didonato, N., Paša-Tolić, L., Greenlon, A., Sieradzki, E. T., Dijkstra, P., Schwartz, E., Sachdeva, R., Banfield, J., and Pett-Ridge, J.: Life and death in the soil microbiome: how ecological processes influence biogeochemistry, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 20, 415–430, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-022-00695-z, 2022.

Steven, B., Gallegos-Graves, L. V., Belnap, J., and Kuske, C. R.: Dryland soil microbial communities display spatial biogeographic patterns associated with soil depth and soil parent material, FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 86, 101–113, https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6941.12143, 2013.

Walters, K. E. and Martiny, J. B. H.: Alpha-, beta-, and gamma-diversity of bacteria varies across habitats, PLoS One, 15, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233872, 2020.

Weber, B., Belnap, J., Büdel, B., Antoninka, A. J., Barger, N. N., Chaudhary, V. B., Darrouzet-Nardi, A., Eldridge, D. J., Faist, A. M., Ferrenberg, S., Havrilla, C. A., Huber-Sannwald, E., Malam Issa, O., Maestre, F. T., Reed, S. C., Rodriguez-Caballero, E., Tucker, C., Young, K. E., Zhang, Y., Zhao, Y., Zhou, X., and Bowker, M. A.: What is a biocrust? A refined, contemporary definition for a broadening research community, Biological Reviews, 97, 1768–1785, https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12862, 2022.

Whitaker, J. M., Vanapalli, S., and Fortin, D.: Improving the strength of sandy soils via ureolytic CaCO3 solidification by Sporosarcina ureae, Biogeosciences, 15, 4367–4380, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-4367-2018, 2018.

Xu, L., Zhu, B., Li, C., Yao, M., Zhang, B., and Li, X.: Development of biological soil crust prompts convergent succession of prokaryotic communities, Catena, 187, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2019.104360, 2020.