the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Nitrogen fixation in Arctic coastal waters (Qeqertarsuaq, West Greenland): influence of glacial melt on diazotrophs, nutrient availability, and seasonal blooms

Isabell Schlangen

Elizabeth Leon-Palmero

Annabell Moser

Peihang Xu

Erik Laursen

Carolin R. Löscher

The Arctic Ocean is undergoing rapid transformation due to climate change, with decreasing sea ice contributing to a predicted increase in primary productivity. A critical factor determining future productivity in this region is the availability of nitrogen, a key nutrient that often limits biological growth in Arctic waters. The fixation of dinitrogen (N2) gas, a biological process mediated by diazotrophs, provides a source of new nitrogen to marine ecosystems and has been increasingly recognized as a potential contributor to nitrogen supply in the Arctic Ocean. Historically it was believed to be limited to oligotrophic tropical and subtropical oceans, Arctic N2 fixation has only garnered significant attention over the past decade, leaving a gap in our understanding of its magnitude, the diazotrophic community, and potential environmental drivers. In this study, we investigated N2 fixation rates and the diazotrophic community in Arctic coastal waters, using a combination of isotope labeling, genetic analyses and biogeochemical profiling, in order to explore its response to glacial meltwater, nutrient availability and its impact on primary productivity. We observed N2 fixation rates ranging from 0.16 to 2.71 nmol N L−1 d−1, notably higher than many previously reported rates for Arctic waters. The diazotrophic community was predominantly composed of UCYN-A. The highest N2 fixation rates co-occurred with peaks in chlorophyll a and primary production at a station in the Vaigat Strait, likely influenced by glacial meltwater input. On average, N2 fixation contributed 1.6 % of the estimated nitrogen requirement of primary production, indicating that while its role is modest, it may still represent a nitrogen source in certain conditions. These findings illustrate the potential importance of N2 fixation in an environment previously not considered important for this process and provide insights into its response to the projected melting of the polar ice cover.

- Article

(6458 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(390 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Nitrogen is a key element for life and often acts as a growth-limiting factor for primary productivity (Gruber and Sarmiento, 1997; Gruber, 2004; Gruber and Galloway, 2008). Despite nitrogen gas (N2) making up approximately 78 % of the atmosphere, it remains inaccessible to most marine life forms. Diazotrophs, which are specialized bacteria and archaea, have the ability to convert N2 into biologically available nitrogen, facilitated by the nitrogenase enzyme complex carrying out the process of

biological nitrogen fixation (N2 fixation) (Capone and Carpenter, 1982). Despite the fact that these organisms are highly specialized and N2 fixation is energetically demanding, the ability to carry out this process is widespread amongst prokaryotes. However, it is controlled by several factors such as temperature, light, nutrients and trace metals such as iron and molybdenum (Sohm et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2019). Oceanic N2 fixation is the major source of nitrogen to the marine system (Karl et al., 2002; Gruber and Sarmiento, 1997), thus, diazotrophs determine the biological productivity of our planet (Falkowski et al., 2008), impact the global carbon cycle and the formation of organic matter (Galloway et al., 2004; Zehr and Capone, 2020). Traditionally it has been believed that the distribution of diazotrophs was limited to warm and oligotrophic waters (Buchanan et al., 2019; Sohm et al., 2011; Luo et al., 2012) until putative diazotrophs were identified in the central Arctic Ocean and Baffin Bay (Farnelid et al., 2011; Damm et al., 2010). First rate measurements have been reported for the Canadian Arctic by Blais et al. (2012) and recent studies have reported rate measurements in adjacent seas (Harding et al., 2018; Sipler et al., 2017; Shiozaki et al., 2017, 2018), drawing attention to cold and temperate waters as significant contributors to the global nitrogen budget through diverse organisms.

UCYN-A has been described as the dominant active N2 fixing cyanobacterial diazotroph in arctic waters (Harding et al., 2018), while other cyanobacteria have only occasionally been reported (Díez et al., 2012; Fernández-Méndez et al., 2016; Blais et al., 2012). However, other recent studies suggest, that the majority of the arctic marine diazotrophs are NCDs (non-cyanobacterial diazotroph) and those may contribute significantly to N2 fixation in the Arctic Ocean (Shiozaki et al., 2018; Fernández-Méndez et al., 2016; Harding et al., 2018; Von Friesen and Riemann, 2020). Recent work by Robicheau et al. (2023) nearby Baffin Bay, geographically close to the sampling area, document low nifH gene abundance while still detecting diazotrophs in Arctic surface waters, highlighting the patchy distribution of diazotrophs across Arctic coastal environments. Studies on the Arctic diazotroph community remain scarce, leaving Arctic environments poorly understood regarding N2 fixation. Shao et al. (2023) note the impossibility of estimating Arctic N2 fixation rates due to the sparse spatial coverage, which currently represents only approximately 1 % of the Arctic Ocean. Increasing data coverage in future studies will aid in better constraining the contribution of N2 fixation to the global oceanic nitrogen budget (Tang et al., 2019).

The Arctic ecosystem is undergoing significant changes driven by rising temperatures and the accelerated melting of sea ice, a trend predicted to intensify in the future (Arrigo et al., 2008; Hanna et al., 2008; Haine et al., 2015). These climate-driven shifts have stimulated primary productivity in the Arctic by 57 % from 1998 to 2018, elevating nutrient demands in the Arctic Ocean (Ardyna and Arrigo, 2020; Arrigo and van Dijken, 2015; Lewis et al., 2020). This increase is attributed to prolonged phytoplankton growing seasons and expanding ice-free areas suitable for phytoplankton growth (Arrigo et al., 2008). However, despite these dramatic changes, the role of N2 fixation in sustaining Arctic primary production remains poorly understood. While recent studies suggest that diazotrophic activity may contribute to nitrogen inputs in polar regions (Sipler et al., 2017), fundamental uncertainties remain regarding the extend, distribution and environmental drivers of N2 Fixation in the Arctic Ocean. Specifically, it is unclear whether increased glacial meltwater input enhances or inhibits N2 Fixation through changes in nutrient availability, stratification, and microbial community composition. Thus, the question of whether nitrogen limitation will emerge as a key factor constraining Arctic primary production under future climate scenarios remains unresolved. In this study, we investigate the diversity of diazotrophic communities alongside in situ N2 fixation rate measurements in Disko Bay (Qeqertarsuaq), a coastal Arctic system strongly influenced by glacial meltwater input. By linking environmental parameters to N2 fixation dynamics, we aim to clarify the role of diazotrophs in Arctic nutrient cycling and assess their potential contribution to sustaining primary production in a changing Arctic. Understanding these processes is essential for refining biogeochemical models and predicting ecosystem responses to future climate change.

2.1 Seawater sampling

The research expedition was conducted from 16 to 26 August 2022 aboard the Danish military vessel P540 within the waters of Qeqertarsuaq, located in the western region of Greenland (Kalaallit Nunaat). Discrete water samples were obtained using a 10 L Niskin bottle, manually lowered with a hand winch to five distinct depths (surface, 5, 25, 50, and 100 m). A comprehensive sampling strategy was employed at 10 stations (Fig. 1), covering the surface to a depth of 100 m. The sampled parameters included water characteristics, such as nutrient concentrations, chl a, particulate organic carbon (POC) and nitrogen (PON), molecular samples for nucleic acid extractions (DNA), dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) as well as CTD sensor data. At three selected stations (3,7,10) N2 fixation and primary production rates were quantified through concurrent incubation experiments.

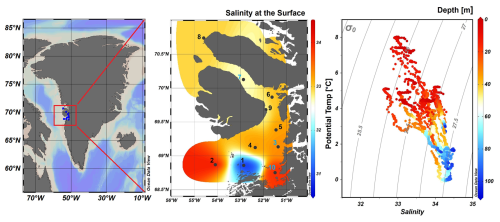

Figure 1Map of Greenland (Kalaallit Nunaat) with indication of study area (red box), on the left. Interpolated distribution of Sea Surface Salinity (SSS) values with corresponding isosurface lines and indication of 10 sampled stations (normal stations in black, incubation stations in blue), black arrows indicate the West Greenland Current (WGC) and the black box indicate the location of the Jakobshavn Isbræ, in the middle. Scatterplot of the potential temperature and salinity for all station data. The plot is used for the identification of the main water masses within the study area. Isopycnals (kg m−3) are depicted in grey lines, on the right. Figures were created in Ocean Data View (ODV) (Schlitzer, 2022).

Samples for nutrient analysis, nitrate (NO), nitrite (NO) and phosphate (PO) were taken in triplicates, filtered through a 0.22 µm syringe filter (Avantor VWR® Radnor, Pa, USA) and stored at −20 °C until further analysis. Concentrations were spectrophotometrically determined (Thermo Scientific, Genesys 1OS UV-VIS spectrophotometer) following the established protocols of Murphy and Riley (1962) for PO; García-Robledo et al. (2014) for NO & NO (detection limits: 0.01 µmol L−1 (NO, NO , and PO), 0.05 µmol L−1 (NH). Chl a samples were filtered onto 47 mm ø GF/F filters (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Whatman, USA), placed into darkened 15 mL LightSafe centrifuge tubes (Merck, Rahway, NJ, USA) and were subsequently stored at −20 °C until further analysis. To determine the Chl a concentration, the samples were immersed in 8 mL of 90 % acetone overnight at 5 °C. Subsequently, 1 mL of the resulting solution was transferred to a 1.5 mL glass vial (Mikrolab Aarhus A/S, Aarhus, Denmark) the following day and subjected to analysis using the Triology® Fluorometer (Model #7200-00) equipped with a Chl a in vivo blue module (Model #7200-043, both Turner Designs, San Jose, CA, USA). Measurements of serial dilutions from a 4 mg L−1 stock standard and 90 % acetone (serving as blank) were performed to calibrate the instrument. In addition, measurements of a solid-state secondary standard were performed every 10 samples. Water (1 L) from each depth was filtered for the determination of POC and PON concentrations, as well as natural isotope abundance (δ13C N PON) using 47 mm ø, 0.7 µm nominal pore size precombusted GF/F filter (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Whatman, USA), which were subsequently stored at −20 °C until further analysis. Seawater samples for DNA were filtered through 47 mm ø, 0.22 µm MCE membrane filter (Merck, Millipore Ltd., Ireland) for a maximum of 20 min, employing a gentle vacuum (200 mbar). The filtered volumes varied depending on the amount of material captured on the filter, ranging from 1.3 to 2 L, with precise measurements recorded. The filters were promptly stored at −20 °C on the ship and moved to −80 °C upon arrival to the lab until further analysis.

To achieve detailed vertical profiles, a conductivity-temperature-depth-profiler (CTD, Seabird X) equipped with supplemen- tary sensors for dissolved oxygen (DO), photosynthetic active radiation (PAR), and fluorescence (Flourometer) was manually deployed.

2.2 Nitrogen fixation and primary production

Water samples were collected at three distinct depths (0, 25 and 50 m) for the investigation of N2 fixation rates and primary production rates, encompassing the euphotic zone, chlorophyll maximum, and a light-absent zone. Three incubation stations (Fig. 2: station 3, 7, 10) were chosen, in a way to cover the variability of the study area. This strategic sampling aimed to capture a gradient of the water column with varying environmental conditions, relevant to the aim of the study. N2 fixation rates were assessed through triplicate incubations employing the modified 15N–N2 dissolution technique after Großkopf et al. (2012) and Mohr et al. (2010).

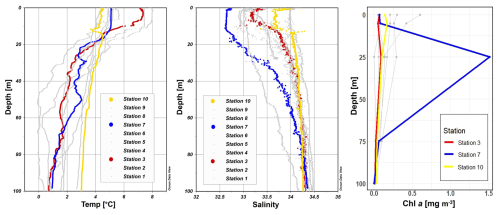

Figure 2Profiles of temperature (°C), salinity, photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) (µmol m−2 s−1) and Chl a (mg m−3) across stations 1 to 10 with depth (m). Stations 3, 7, and 10 are highlighted in red, blue, and yellow, respectively, to emphasize incubation stations. Figures were created in Ocean Data View and R-Studio (Schlitzer, 2022).

To ensure minimal contamination, 2.3 L glass bottles (Schott-Duran, Wertheim, Germany) underwent pre-cleaning and acid washing before being filled with seawater samples. Oxygen contamination during sample collection was mitigated by gently and bubble-free filling the bottles from the bottom, allowing the water to overflow. Each incubation bottle received a 100 mL amendment of 15N–N2 enriched seawater (98 %, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.,USA) achieving an average dissolved N2 isotope abundance (15N atom %) of 3.90 ± 0.02 atom % (mean ± SD). Additionally, 1 mL of H13CO3 (1 g/50 mL) (Sigma- Aldrich, Saint Louis Missouri US) was added to each incubation bottle, roughly corresponding to 10 atom % enrichment and thus measurements of primary production and N2 fixation were conducted in the same bottle. Following the addition of both isotopic components, the bottles were closed airtight with septa-fitted caps and incubated for 24 h on-deck incubators with a continuous surface seawater flow. These incubators, partially shaded (using daylight-filtering foil) to simulate in situ photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) conditions, aimed to replicate environmental parameters experienced at the sampled depths. Control incubations utilizing atmospheric air served as controls to monitor any natural changes in δ15N not attributable to 15N–N2 addition. These control incubations were conducted using the dissolution method, like the 15N–N2 enrichment experiments, but with the substitution of atmospheric air instead of isotopic tracer.

After the incubation period, subsamples for nutrient analysis were taken from each incubation sample, and the remaining content was subjected to the filtration process and were gently filtered (200 mbar) onto precombusted GF/F filters (Advantec, 47 mm ø, 0.7 µm nominal pore size). This step ensured a comprehensive examination of both nutrient dynamics and the isotopic composition of the particulate pool in the incubated samples. Samples were stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

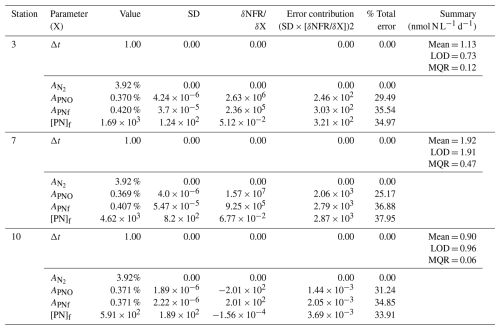

Upon arrival in the lab, the filters were dried at 60 °C and to eliminate particulate inorganic carbon, subsequently subject to acid fuming during which they were exposed to concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCL) vapors overnight in a desiccator. After undergoing acid treatment, the filters were carefully dried, then placed into tin capsules and pelletized for subsequent analysis. The determination of POC and PON, as well as isotopic composition (δ13C POC/δ15N PON), was carried out using an elemental analyzer (Flash EA, ThermoFisher, USA) connected to a mass spectrometer (Delta V Advantage Isotope Ratio MS, ThermoFisher, USA) with the ConFlo IV interface. This analytical setup was applied to all filters. These values, derived from triplicate incubation measurements, exhibited no omission of data points or identification of outliers. Final rate calculations for N2 fixation rates were performed after Mohr et al. (2010) and primary production rates after Slawyk et al. (1977). A detailed sensitivity analysis of N2 fixation rates, including the contribution of each source of error for all parameters, is provided in a supplementary table and summarized form in Table A1.

2.3 Molecular methods

The filters were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, crushed and DNA was extracted using the Qiagen DNA/RNA AllPrep Kit (Qiagen, Hildesheim, DE), following the procedure outlined by the manufacturer. The concentration and quality of the extracted DNA was assessed spectrophotometrically using a MySpec spectrofluorometer (VWR, Darmstadt, Germany). The preparation of the metagenome library and sequencing were performed by BGI (China). Sequencing libraries were generated using MGIEasy Fast FS DNA Library Prep Set following the manufacturer's protocol. Sequencing was conducted with 2 × 150 bp on a DNBSEQ-G400 platform (MGI). SOAPnuke1.5.5 (Chen et al., 2018) was used to filter and trim low quality reads and adaptor contaminants from the raw sequence reads, as clean reads. In total, fifteen metagenomic datasets were produced with an average of 9.6G bp per sample.

Metagenomic De Novo assembly, gene prediction, and annotation

Megahit v1.2.9 (Li et al., 2015) was used to assemble clean reads for each dataset with its minimum contig length as 500. Prodigal v2.6.3 (Hyatt et al., 2010) with the setting of “−p meta” was then used to predict the open reading frames (ORFs) of the assembled contigs. ORFs from all the available datasets were filtered (> 100 bp), dereplicated and merged into a catalog of non-redundant genes using cd-hit-est (> 95 % sequence identity) (Fu et al., 2012). Salmon v1.10.0 (Patro et al., 2017) with the “– meta” option was employed to map clean reads of each dataset to the catalog of non-redundant genes and generate the GPM (genes per million reads) abundance. Eggnog mapper v2.1.12 (Cantalapiedra et al., 2021) was then performed to assign KEGG Orthology (KO) and identify specific functional annotation for the catalog of non-redundant genes. The marker genes, nifDK (K02586, K02591 nitrogenase molybdenum-iron protein alpha/beta chain) and nif H (K02588, nitrogenase iron protein), were used for the evaluation of microbial potential of N2 fixation. RbcL (K01601, ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase large chain) and psbA (K02703, photosystem II P680 reaction center D1 protein) were selected to evaluate the microbial potential of carbon fixation and photosynthesis, respectively. The molecular datasets have been deposited with the accession number: Bioproject PRJNA1133027.

3.1 Hydrographic conditions in Qeqertarsuaq (Disco Bay) and Sullorsuaq (Vaigat) Strait

Disko Bay (Qeqertarsuaq) is located along the west coast of Greenland (Kalaallit Nunaat) at approximately 69° N (Fig. 1), and is strongly influenced by the West Greenland Current (WGC) which is associated with the broader Baffin Bay Polar Waters (BBPW) (Mortensen et al., 2022; Hansen et al., 2012). The WGC does not only significantly shape the hydrographic conditions within the bay but also plays an important role in the larger context of Greenland Ice Sheet melting (Mortensen et al., 2022). Central to the hydrographic system of the Qeqertarsuaq area is the Jakobshavn Isbræ, which is the most productive glacier in the northern hemisphere and believed to drain about 7 % of the Greenland Ice Sheet and thus contributes substantially to the water influx into the Qeqertarsuaq (Holland et al., 2008). A predicted increased inflow of warm subsurface water, originating from North Atlantic waters, has been suggested to further affect the melting of the Jakobshavn Isbræ and thus adds another layer of complexity to this dynamic system (Holland et al., 2008; Hansen et al., 2012).

The hydrographic conditions in Qeqertarsuaq have a significant influence on biological processes, nutrient availability, and the broader marine ecosystem (Munk et al., 2015; Hendry et al., 2019; Schiøtt, 2023).

During our survey, we found very heterogenous hydrographic conditions at the different stations across Qeqertarsuaq (Figs. 1 and 2). The three selected stations for N2 fixation analysis (stations 3, 7, and 10) were strategically chosen to capture the spatial variability of the area. Surface salinity and temperature measurements at these stations indicate the influence of freshwater input. The surface temperature exhibit a range of 4.5 to 8 °C, while surface salinity varies between 31 and 34, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The profiles sampled during our survey extend to a maximum depth of 100 m. Comparison of temperature/salinity (T/S) plots with recent studies suggests the presence of previously described water masses, including Warm Fjord Water (WFjW) and Cold Fjord Water (CFjW) with an overlaying surface glacial meltwater runoff. Those water masses are defined with a density range of 27.20 27.31 but different temperature profiles. Thus water masses can be differentiated by their temperature within the same density range (Gladish et al., 2015). Other water masses like upper subpolar mode water (uSPMW), deep subpolar mode water (dSPMW) and Baffin Bay polar Water (BBPW) which has been identified in the Disko Bay (Qeqertarsuaq) before, cannot be identified from this data and may be present in deeper layers (Mortensen et al., 2022; Sherwood et al., 2021; Myers and Ribergaard, 2013; Rysgaard et al., 2020). The temperature and salinity profiles across the 10 stations in the study area show distinct stratification and variability, which is represented through the three incubation stations (highlighted stations 3, 7, and 10 in Fig. 2). They display varying degrees of stratification and mixing, with notable differences in the salinity and termperature profiles. Station 3 and station 7 exhibit clear stratification in both temperature and salinity marked by the presence of thermoclines and haloclines. These features suggest significant freshwater input influenced by local weather conditions and climate dynamics, like surface heat absorption. In contrast, Station 10 exhibits a narrower range of temperature and salinity values throughout the water column compared to Stations 3 and 7, indicating more well-mixed conditions. This uniformity is likely influenced by the regional circulation pattern and partial upwelling (Hansen et al., 2012; Krawczyk et al., 2022). The distinct characteristics observed at station 10, as illustrated in the surface plot (Fig. 1), show an elevated salinity and colder temperatures compared to the other stations. This feature suggests upwelling of deeper waters along the shallower shelf, likely facilitated by the local seafloor topography. Specifically, the seafloor shallowing off the coast of Station 10 may act as a barrier, disrupting typical circulation and forcing deeper, saltier, and colder waters to the surface. This pattern aligns with previous studies that describe similar mechanisms in the region (Krawczyk et al., 2022). Their description of the bathymetry in Qeqertarsuaq, featuring depths ranging from ca. 50 to 900 m, suggests its impact on turbulent circulation patterns, leading to the mixing of different water masses. Evident variability in oceanographic conditions that can be observed throughout the study area occurs particularly along characteristic topographical features like steep slopes, canyons, and shallower areas. The summer melting of sea ice and glaciers introduces freshwater influxes that create distinct vertical and horizontal gradients in salinity and temperature in the Qeqertarsuaq area Hansen et al. (2012). Additionally, the accelerated melting of the Jakobshavn Isbraæ, influenced by the warmer inflow from the West Greenland Intermediate Current (WGIC), further alters the hydrographic conditions. Recent observations indicate significant warming and shoaling of the WGIC, potentially enabling it to overcome the sill separating the Illulissat Fjord from the Qeqertarsuaq area (Hansen et al., 2012; Holland et al., 2008; Myers and Ribergaard, 2013). This shift intensifies glacier melting, driving substantial changes in the local ecological dynamics (Ardyna et al., 2014; Arrigo et al., 2008; Bhatia et al., 2013).

3.2 N2 Fixation Rate Variability and Associated Environmental Conditions

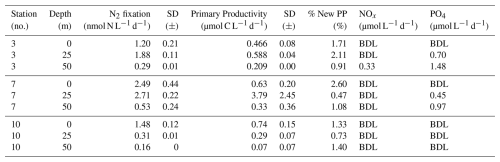

We quantified N2 fixation rates within the waters of Qeqertarsuaq, spanning from the surface to a depth of 50 m (Table 1). The rates ranged from 0.16 to 2.71 nmol N L−1 d−1 with all rates surpassing the minimum quantifiably rate (Appendix Table 1). Our findings represent rates at the upper range of those observed in the Arctic Ocean. Previous measurements in the region have been limited, with only one study in Baffin Bay by Blais et al. (2012), reporting rates of 0.02 nmol N L−1 d−1, which are 1–2 orders of magnitude lower than our observations. Moreover, Sipler et al. (2017), reported rated in the coastal Chukchi Sea, with average values of 7.7 nmol N L−1 d−1. These values currently represent some of the highest rates measured in Arctic shelf environments. Compared to these, our highest measured rate (2.71 nmol N L−1 d−1) is lower, but still important, particularly considering the more Atlantic-influenced location of our study site. Sipler et al. (2017) also noted that a significant fraction of diazotrophs were < 3 µm in size, suggesting that small unicellular diazotrophs play a dominant role in Arctic nitrogen fixation. Altogether, our data contribute to the growing evidence that N2 fixation is a widespread and potentially significant nitrogen source across various Arctic regions. Simultaneous primary production rate measurements ranged from 0.07 to 3.79 µmol N L−1 d−1, with the highest rates observed at station 7 and generally higher values in the surface layers. Employing Redfield stoichiometry, the measured N2 fixation rates accounted for 0.47 % to 2.6 % (averaging 1.57 %) of primary production at our stations. The modest contribution to primary production suggests that N2 fixation does not exert a substantial influence on the productivity of these waters during the time of the sampling. Rather, our N2 fixation rates suggest primary production to depend mostly on additional nitrogen sources including regenerated, meltwater or land-based sources.

Table 1N2 fixation (nmol N L−1 d−1), standard deviation (SD), primary productivity (PP; µmol C L−1 d−1), SD, percentage of estimated new primary productivity (% New PP) sustained by N2 fixation, dissolved inorganic nitrogen compounds (NOx), phosphorus (PO4), and the molar nitrogen-to-phosphorus ratio (N:P) at stations 3, 7, and 10. BDL = Below detection limit.

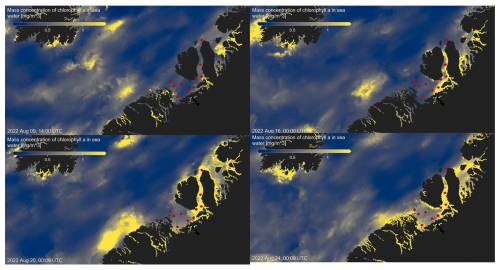

While the N:P ratio is commonly used to assess nutrient limitations relative to Redfield stoichiometry, most DIN and DIP measurements in our study were below detection limit (BDL), preventing a reliable calculation for this ratio. As such, we refrain from drawing conclusions based on N:P stoichiometry. Nevertheless, previous studies by Jensen et al. (1999) and Tremblay and Gagnon (2009), have identified nitrogen limitation in this region. Such biogeochemical conditions, when present, would be expected to generate a niche for N2 fixing organisms (Sohm et al., 2011). While N2 fixation did not chiefly sustain primary production during our sampling campaign, we hypothesize that N2 fixation has the potential to play a role in bloom dynamics under certain conditions. As nitrogen availability decreases during a bloom, it may provide a niche for N2 fixation, potentially helping to extend the productive period of the bloom period (Reeder et al., 2022). Satellite data indicates that a fall bloom began in early August, following the annual spring bloom, as described by Ardyna et al. (2014). This double bloom situation may be driven by increased melting and the subsequent input of bioavailable nutrients and iron (Fe) from meltwater runoff (Arrigo et al., 2017; Hopwood et al., 2016; Bhatia et al., 2013). The meltwater from the Greenland Ice Sheet is a significant source of Fe (Bhatia et al., 2013; Hawkings et al., 2015, 2014), which is a limiting factor especially for diazotrophs (Sohm et al., 2011). Consequently, it is plausible that Fe and nutrients from the Isbræ glacier create favorable conditions for both bloom development and diazotroph activity in Qeqertarsuaq. However, we emphasize that confirming a causal link between N2 fixation and secondary bloom development requires further evidence, such as time-series data on nutrient concentrations, diazotroph abundance, and bloom dynamics.

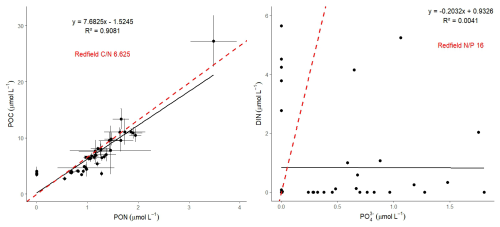

A near-Redfield stoichiometry in POC:PON suggests that the particulate organic matter (POM) likely originates from an ongoing phytoplankton bloom, as phytoplankton generally assimilate carbon and nitrogen in relatively consistent proportions during active growth (Redfield, 1934). However this assumption is based on a global average, and POM stoichiometry can exhibit substantial latitudinal variation. Deviations may also arise during particle production and remineralization processes (Redfield, 1934; Geider and La Roche, 2002; Sterner and Elser, 2003; Quigg et al., 2003). Recent studies have further shown that POM composition vary widely across plankton communities, influenced by factors such as growth rates, community composition, ad physiological status (e.g. fast- vs. slow-growing organisms), with degradation often playing a secondary role (Tanioka et al., 2022). Additionally, terrestrial organic material – likely introduced via glacial outflow in the study area – may also contribute to the observed POM composition (Schneider et al., 2003). Latitudinal variability in organic matter stoichiometry has also been linked to differences in nutrient supply and phosphorus stress (Fagan et al., 2024; Tanioka et al., 2022). Consequently, the near-Redfield stoichiometry observed here cannot be clearly attributed to freshly produced organic material. Nevertheless, satellite-derived surface chlorophyll a concentration and associated primary production support the interpretation that recently produced organic matter does contribute, at least in part, to the sinking POM captured in our samples. Since inorganic nitrogen species (e.g., NOx) were below detection limits, direct calculation or interpretation of the N:P ratio in the dissolved nutrient pool was not possible and has been avoided. The absence of available nitrogen may nonetheless reflect nitrogen depletion, potentially creating ecological niches for diazotrophs and nitrogen-fixing organisms. Such conditions may promote shifts in microbial community structure, as observed by Laso-Perez et al. (2024). Laso Perez et al. (2024) documented changes in microbial community composition during an Arctic bloom, focusing on nitrogen cycling. They observed a shift from chemolithotrophic to heterotrophic organisms throughout the summer bloom and noted increased activity to compete for various nitrogen sources. However, no nif H gene copies, indicative of nitrogen-fixing organisms, were found in their dataset based on metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs). This is not unexpected due to the classically low abundance of diazotrophs in marine microbial communities which has often been described (Turk-Kubo et al., 2015; Farnelid et al., 2019). Given the high productivity and metabolic activity observed in Qeqertarsuaq during a similar bloom period, the detected diazotrophs (Sect. 3.3) may play a more significant role than previously thought. Across the 10 stations there is considerable variability in POC and PON concentrations (Fig. 3). PON concentrations range from 0.0 to 3.48 µmol N L−1 (n= 124), while POC concentrations range from 2.7 to 27.2 µmol C L−1 (n= 144). The highest concentrations for both PON and POC were observed at station 7 at a depth of 25 m and coincide with the highest reported N2 fixation rate (Figs. A2 and A3). Generally, POC and PON concentrations decrease with depth, peaking at the deep chl a maximum (DCM), identified between 15 to 30 m across all stations. The DCM was identified based on measured chl a concentrations and previous descriptions in the region (Fox and Walker, 2022; Jensen et al., 1999). The variability in chl a concentrations indicates differences in phytoplankton abundance among the stations, with concentrations ranging between 0 to 0.42 mg m−3. Excluding station 7, which exhibited the highest chl a concentration at the DCM (1.51 mg m−3). While Tang et al. (2019) found that N2 fixation measurements strongly correlated to satellite estimates of chl a concentrations, our results did not show a statistically significant correlation between nitrogen fixation rates and chl a concentrations overall (Figs. A2 and A3). However, as noted, Station 7 at 25 m represents a unique case. The elevated concentration of chl a at this station likely resulted from a local phytoplankton bloom induced by meltwater outflow from the Isbræ glacier and sea ice melting, which may help explain the observed nitrogen fixation rates (Arrigo et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2014). This study's findings are in agreement with prior reports of analogous blooms occurring in the region (Fox and Walker, 2022; Jensen et al., 1999).

3.3 Potential Contribution of UCYN-A to Nitrogen Fixation During a Diatom Bloom: Insights and Uncertainties

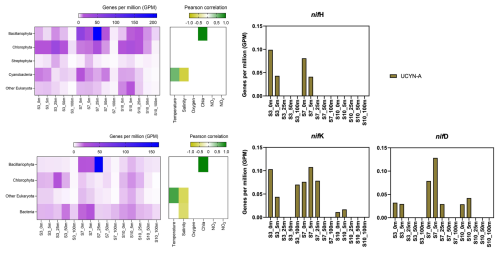

In our metagenomic analysis, we filtered the nif H, nif D, nif K genes, which code for the nitrogenase enzyme responsible for catalyzing N2 fixation. We could identify sequences related to UCYN-A, which dominated the sequence pool of diazotrophs, particularly in the upper water masses (0 to 5 m) (Fig. 4). UCYN-A, a unicellular cyanobacterial symbiont, has a cosmopolitan distribution and is thought to substantially contribute to global N2 fixation, as documented by (Martínez-Pérez et al., 2016; Tang et al., 2019). This conclusion is based on our metagenomic analysis, in which we set a sequence identity threshold of 95 % for both nif and photosystem genes. Notably, we only recovered sequences related to UCYN-A within our nif sequence pool, suggesting its predominance among detected diazotrophs. However, metagenomic approaches may underestimate overall diazotroph diversity, and we cannot fully exclude the presence of other, less abundant diazotrophs that may have been missed using this method. While UCYN-A was primarily detected in surface waters, we also observed relatively high nifK values at S3_100m, an unusual finding given that UCYN-A is typically constrained to the euphotic zone. Previous studies have predominantly reported UCYN-A in surface waters; for instance Harding et al. (2018) and Shiozaki et al. (2017) detected UCYN-A exclusively in the upper layers of the Arctic Ocean. Additionally, Shiozaki et al. (2020) found UCYN-A2 at depths extending to the 0.1 % light level but not below 66 m in the Chukchi Sea. The detection of UCYN-A at 100 m in our study suggests that alternative mechanisms, such as particle association, vertical transport, or local environmental conditions, may facilitate its presence at depth. Interestingly, despite very low nifH copy numbers being reported in nearby Baffin Bay by Robicheau et al. (2023), UCYN-A dominated the metagenomic nifH community in our study, further underscoring this organisms's presence in Arctic surface coastal areas under certain environmental conditions. This warrants further investigation into the environmental drivers and potential processes enabling its occurrence in Arctic waters.

Figure 4Upper left image: psbA with correlation plot. Lower left image: rbcL with correlation plot. Right image: nif H, nif D, nif K genes per million reads in the metagenomic datasets. All figures display molecular data from metagenomic dataset for all sampled depth of station 3, 7, 10.

Due to the lack of genes such as those encoding Photosystem II and Rubisco, UCYN-A plays a significant role within the host cell and participates in fundamental cellular processes. Consequently, it has evolved to become a closely integrated component of the host cell. Very recent findings demonstrate that UCYN-A imports proteins encoded by the host genome and has been described as an early form of N2 fixing organelle termed a “Nitroplast” (Coale et al., 2024).

Previous investigations document that they are critical for primary production, supplying up to 85 % of the fixed nitrogen to their haptophyte host (Martínez-Pérez et al., 2016). In addition to its high contribution to primary production, studies have shown that UCYN-A in high latitude waters fix similar amounts of N2 per cell as in the tropical Atlantic Ocean, even in nitrogen- replete waters (Harding et al., 2018; Shiozaki et al., 2020; Martínez-Pérez et al., 2016; Krupke et al., 2015; Mills et al., 2020). However, estimating their contribution to N2 fixation in our study is challenging, particularly since we detected cyanobacteria only at the surface but observe significant N2 fixation rates below 5 m. The diazotrophic community is often underrepresented in metagenomic datasets due to the low abundance of nitrogenase gene copies, implying our data does not present a complete picture. We suspect a more diverse diazotrophic community exists, with UCYN-A being a significant contributor to N2 fixation in Arctic waters. However, the exact proportion of its contribution requires further investigation.

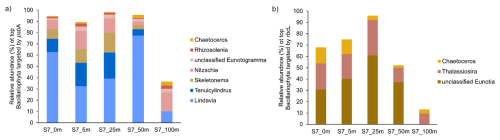

The contribution of N2 fixation to carbon fixation (as percent of PP) is relatively low, at the time of our study. We identified genes such as rbcL, which encodes Rubisco, a key enzyme in the carbon fixation pathway and psbA, a gene encoding Photosystem II, involved in light-driven electron transfer in photosynthesis, in our metagenomic dataset. The gene rbcL (for the carbon fixation pathway) and the gene psbA (for primary producers) were used to track the community of photosynthetic primary producers in our metagenomic dataset. At station 7, elevated carbon fixation rates are correlated with high diatom (Bacillariophyta) abundance and increased chl a concentration (Fig. 4), suggesting the onset of a bloom, which is also observable via satellite images (Appendix A1). We hypothesize that meltwater, carrying elevated nutrient and trace metal concentrations, was rapidly transported away from the glacier through the Vaigat Strait by strong winds, leading to increased productivity, as previously described by Fox and Walker (2022) and Jensen et al. (1999). The elevated diatom abundance and primary production rates at station 7 coincide with the highest N2 fixation rates, which could point toward a possible diatom-diazotroph symbiosis (Foster et al., 2022, 2011; Schvarcz et al., 2022). However, we did not detect a clear diazotrophic signal directly associated with the diatoms in our metagenomic dataset, which might be due to generally underrepresentation of diazotrophs in metagenomes due to low abundance or low sequencing coverage. To investigate this further, we examined the taxonomic composition of Bacillariophyta at higher resolution. Among the various abundant diatom genera, Rhizosolenia and Chaetoceros have been identified as symbiosis with diazotrophs (Grosse et al., 2010; Foster et al., 2010), representing less than 6 % or 15 % of Bacillariophyta, based on rbcL or psbA, respectively (Fig. A4). Although we underestimate diazotrophs to an extent, the presence of certain diatom-diazotroph symbiosis could help explain the high nitrogen fixation rates in the diatom bloom to a certain degree. Compilation of nif sequences identified from this study as well as homologous from their NCBI top hit were added in Table S1 in the Supplement. However, we cannot tell if the diazotrophs belong to UCYN-A1 or UCYN-A2, or UCYN-A3. Based on the Pierella Karlusich et al. (2021), they generated clonal nifH sequences from Tara Oceans, which the length of nifH sequences is much shorter than the two nifH sequences we generated in our study. Also, the available UCYN-A2 or UCYN-A3 nifH sequences from NCBI were shorter than the two nifH sequences we generated. Therefore, it would be not accurate to assign the nifH sequences to either group under UCYN-A. Furthermore, not much information is available regarding the different groups of UCYN-A using marker genes of nifD and nifK.

There is evidence that UCYN-A have a higher Fe demand, with input through meltwater or river runoff potentially being advantageous to those organisms (Shiozaki et al., 2017, 2018; Cheung et al., 2022). Consequently, UCYN-A might play a more critical role in the future with increased Fe-rich meltwater runoff. UCYN-A can potentially fuel primary productivity by supplying nitrogen, especially with increased melting, nutrient inputs, and more light availability due to rising temperatures as- sociated with climate change. This predicted enhancement of primary productivity may contribute to the biological drawdown of CO2, acting as a negative feedback mechanism. These projections are based on studies forecasting increased temperatures, melting, and resulting biogeochemical changes leading to higher primary productivity. However large uncertainties make predictions very difficult and should be handled with care. Thus, we can only hypothesize that UCYN-A might be coupled to these dynamics by providing essential nitrogen.

3.4 δ15N Signatures in particulate organic nitrogen

Stable isotopic composition, expressed using the δ15N notation, serve as indicators for understanding nitrogen dynamics because different biogeochemical processes fractionate nitrogen isotopes in distinct ways (Montoya, 2008). However, it is important to keep in mind that the final isotopic signal is a combination of all processes and an accurate distinction between processes cannot be made. N2 fixation tends to enrich nitrogenous compounds with lighter isotopes, producing OM with isotopic values ranging approximately from −2 to +2 ‰ (Dähnke and Thamdrup, 2013). Upon complete remineralization and oxidation, organic matter contributes to a reduction in the average δ-values in the open ocean (e.g. Montoya et al., 2002; Emeis et al., 2010). Whereas processes like denitrification and anammox preferentially remove lighter isotopes, leading to enrichment in heavier isotopes and delta values up to −25 ‰.

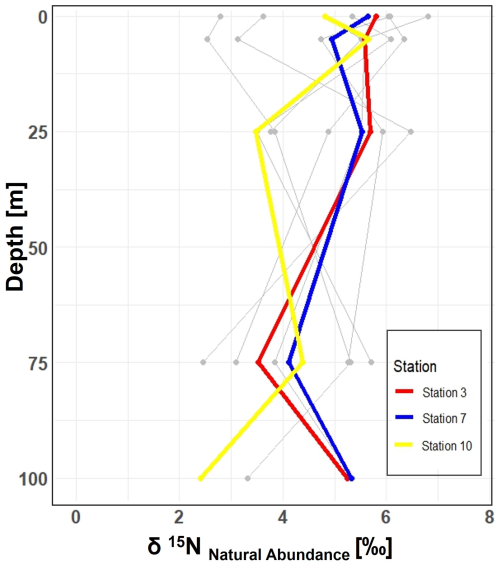

Figure 5Vertical profiles of δ15N natural abundance signatures in PON across 10 stations in the study area. Incubation stations 3, 7, and 10 are highlighted in red, blue, and yellow, respectively. The figure shows variations in δ15N signatures with depth at each station, providing insight into nitrogen cycling in the study area.

In our study, the δ15N values of PON from all 10 stations, range between 2.45 ‰ and 8.30 ‰ within the 0 to 100 m depth range. While N2 fixation typically produces OM ranging from −2 ‰ to 0.5 ‰, this signal can be masked by processes such as remineralization, mixing with nitrate from deeper waters or other biological transformations (Emeis et al., 2010; Sigman et al., 2009). The composition of OM in the surface ocean is influenced by the nitrogen substrate and the fractionation factor during assimilation. When nitrate is depleted in the surface ocean, the isotopic signature of OM produced during photosynthesis will mirror that of the nitrogen source. Nitrate, the primary form of dissolved nitrogen in the open ocean, typically exhibits an average stable isotope value of around 5 ‰. No fractionation occurs during photosynthesis because the nitrogen source is entirely taken up in the surface waters (Sigman et al., 2009). This matches conditions observed in Qeqertarsuaq, suggesting that subsurface nitrate is a dominant nitrogen source (Fox and Walker, 2022).

In the eastern Baffin Bay waters, Atlantic water masses serve as an important source of nitrate to surface waters with δ15N values around 5 ‰ (Sherwood et al., 2021). This is consistent with our observed PON values and supports the view that primary productivity in the region is largely fueled by nitrate input from deeper Atlantic waters, particularly during early bloom stages (Fox and Walker, 2022; Knies, 2022). The mechanisms through which subsurface nitrate reaches the euphotic layer are not well understood. However, potential pathways include vertical migration of phytoplankton and physical mixing. Subsequently, nitrogen undergoes rapid recycling and remineralization processes to meet the system's nitrogen demands (Jensen et al., 1999). Taken together, the δ15N signatures observed in this study are best interpreted as indicative of a system influenced by multiple nitrogen sources and biogeochemical processes, where nitrate input and remineralization appear to dominate.

Our study highlights the occurrence of elevated rates of N2 fixation in Arctic coastal waters, particularly prominent at station 7, where they coincide with high chl a values, indicative of heightened productivity. Satellite observations tracing the origin of a bloom near the Isbræ Glacier, subsequently moving through the Vaigat strait, suggest a recurring phenomenon likely triggered by increased nutrient-rich meltwater originating from the glacier. This aligns with previous reports by Jensen et al. (1999) and Fox and Walker (2022), underlining the significance of such events in driving primary productivity in the region. The contribution of N2 fixation to primary production was low (average 1.57 %) across the stations. Since the demand was high relative to the new nitrogen provided by N2 fixation, the observed primary production must be sustained by the already present or adequate amount of subsurface supply of NOx nutrients in the seawater. This is also visible in the isotopic signature of the POM (Fox and Walker, 2022; Sherwood et al., 2021). However, the detected N2 fixation rates are likely linked to the development of the fresh secondary summer bloom, which could be sustained by high nutrient and Fe availability from melting, potentially leading the system into a nutrient-limited state. The ongoing high demand for nitrogen compounds may suggest an onset to further sustain the bloom, but it remains speculative whether Fe availability definitively contributes to this process. The occurrence of such double blooms has increased by 10 % in the Qeqertarsuaq and even 33 % in the Baffin Bay, with further projected increases moving north from Greenland (Kalaallit Nunaat) waters (Ardyna et al., 2014). Thus, nutrient demands are likely to increase, and the role of N2 fixation can become more significant. The diazotrophic community in this study is dominated by UCYN-A in surface waters and may be linked to diatom abundance in deeper layers. This co-occurrence of diatoms and N2 fixers in the same location is probably due to the co-limitation of similar nutrients, rather than a symbiotic relationship. Thus, this highlights the significant presence of diazotrophs despite their limited representation in datasets. It also highlights the potential for further discoveries, as existing datasets likely underestimate the full extent of the diazotrophic community (Laso Perez et al., 2024; Shao et al., 2023; Shiozaki et al., 2017, 2023). The reported N2 fixation rates in the Vaigat strait within the Arctic Ocean are notably higher than those observed in many other oceanic regions, emphasizing that N2 fixation is an active and significant process in these high-latitude waters. When compared to measured rates across various ocean systems using the 15N approach, the significance of these findings becomes clear. For instance, N2 fixation rates are sometimes below the detection limit and often relatively low ranging from 0.8 to 4.4 nmol N L−1 d−1 (Löscher et al., 2020, 2016; Turk et al., 2011). In contrast, higher rates reach up to 20 nmol N L−1 d−1 (Rees et al. (2009)) and sometime exceptional high rates range from 38 to 610 nmol N L−1 d−1 (Bonnet et al., 2009). The Arctic Ocean rates are thus significant in the global context, underscoring the region's role in the global nitrogen cycle and the importance of N2 fixation in supporting primary productivity in these waters.

These findings highlight the urgent need to understand the interplay between seasonal variations, sea-ice dynamics, and hydro- graphic conditions in Qeqertarsuaq. As climate change accelerates the melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet at Jakobshavn Isbræ, shifts in hydrodynamic patterns and hydrographic conditions in Qeqertarsuaq are anticipated. The resulting influx of warmer waters could significantly reshape the bay's hydrography, making it crucial to comprehend the coupling of climate-driven changes and oceanic processes in this vital Arctic region. Our study provides key insights into these dynamics and underscores the importance of continued investigation to predict Qeqertarsuaq's future hydrographic state. By detailing the environmental and hydrographic changes, we contribute valuable knowledge to the broader context of N2 fixation in the Arctic Ocean. Given nitrogen's pivotal role in Arctic ecosystem productivity, it is essential to explore diazotrophs, quantify N2 fixation, and assess their impact on ecosystem services as climate change progresses.

Figure A1Chlorophyll a concentration mg m−3 at four time points before, during, and after sea water sampling in August 2022 (sampling stations indicated by red dots), obtained from MODIS-Aqua; https://giovanni.gsfc.nasa.gov (last access: 10 May 2024; Aqua MODIS Global Mapped Chl a Data, version R2022.0, https://doi.org/10.5067/AQUA/MODIS/L3M/CHL/2022), 4 km resolution.

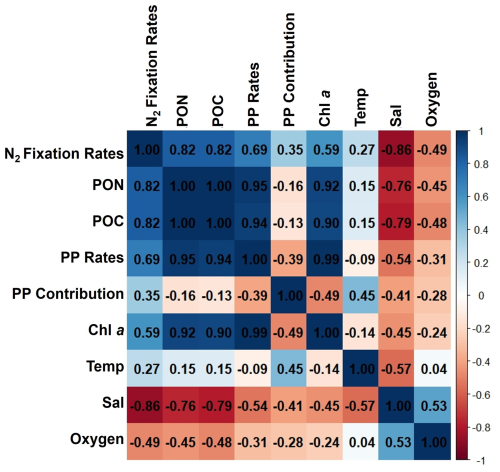

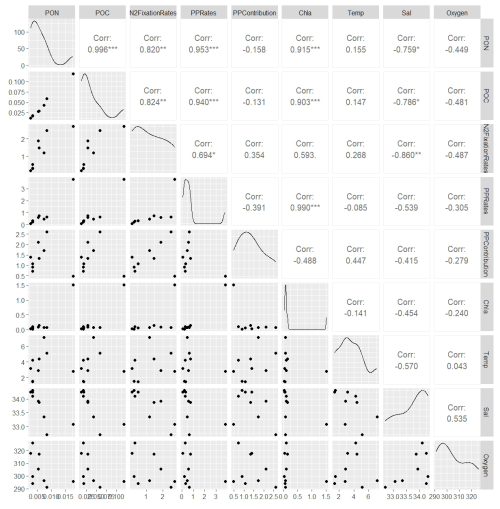

Figure A2Correlation matrix of environmental and biological variables. The plot shows the correlation coefficients between the following parameters: N2 fixation rates, PON, POC, PP rates, the contribution N2 fixation to PP (PP contribution), Chl a, temperature (Temp), salinity (Sal), and Oxygen. The scale ranges from −1 to 1, where values close to 1 or −1 indicate strong positive or negative correlations, respectively, and values near 0 indicate weak or no correlation. The color intensity represents the strength and direction of the correlations, facilitating the identification of relationships among the variables.

Figure A3This figure displays a ggpairs plot, showing pairwise relationships and correlations between biological and environmental vari- ables. Pearson correlation coefficients displayed in the upper triangular panel, indicating the strength and significance of linear relationships. Statistical significance levels are indicated by stars (*), where * indicates p<0.05, indicates p<0.01 and indicates p<0.001.

Figure A4Taxonomic composition of Bacillariophyta at Station 7 based on (a) psbA and (b) rbcL marker genes. The figure shows the relative abundance of Bacillariophyta genera detected in the metagenomic dataset, grouped by gene-specific classifications.

Table A1Sensitivity analysis for N2 fixation rates. The contribution of each source of error to the total uncertainty was determined and calculated after Montoya et al. (1996). Average values and standard deviations (SD) are provided for all parameters at each station. The partial derivative (δNFR/ δX) of the N2 fixation rate measurements is calculated for each parameter and evaluated using the provided average and standard deviation. The total and relative error are given for each parameter. Mean represents the average N2 fixation rate measurement. MQR (minimal quantifiable rate) represents the total uncertainty linked to every measurement and is calculated using standard propagation of error. LOD (limit of detection) represents an alternative detection limit defined as ΔAPN = 0.00146.

The presented data collected during the cruise will be made accessible on PANGEA (https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.973563, Löscher et al., 2025a; https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.973564, Löscher et al., 2025b). The molecular datasets have been deposited with the accession number: Bioproject PRJNA1133027.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-23-1-2026-supplement.

IS carried out fieldwork and laboratory work at the University of Southern Denmark, and wrote the majority of the manuscript. ELP, AM, and EL conducted fieldwork and laboratory work at the University of Southern Denmark. PX performed metagenomic analysis and created the corresponding graphs. CRL designed the study, provided supervision and guidance throughout the project, and contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the conception of the study and participated in the writing and revision of the manuscript.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Biogeosciences. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This work was supported by the Velux Foundation (grant no. 29411 to Carolin R. Löscher) and through the DFF grant from the the Independent Research Fund Denmark (grant no. 0217-00089B to Lasse Riemann, Carolin R. Löscher and Stiig Markager). ELP was supported by a postdoctoral contract from Danmarks Frie Forskningsfond (DFF, 1026-00428B) at SDU, and by a Marie Skłodowska- Curie postdoctoral fellowship (HORIZON291 MSCA-2021-PF-01, project number: 101066750) by the European Commission at Princeton University. We sincerely thank the captain and crew of the P540 during the cruise on the Danish military vessel for their invaluable support and cooperation at sea. Our gratitude extends to Isaaffik Arctic Gateway for providing the infrastructure and opportunities that made this project possible. We also acknowledge Zarah Kofoed for her technical support in the laboratory and thank all the Nordcee laboratory technicians for their general assistance.

This research has been supported by the Velux Fonden (grant no. 29411), the Danmarks Frie Forskningsfond (grant nos. 0217-00089B and 1026-00428B), and the EU H2020 Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (grant no. 101066750).

This paper was edited by Emilio Marañón and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Ardyna, M. and Arrigo, K. R.: Phytoplankton dynamics in a changing Arctic Ocean, Nature Climate Change, 10, 892–903, 2020.

Ardyna, M., Babin, M., Gosselin, M., Devred, E., Rainville, L., and Tremblay, J.-É.: Recent Arctic Ocean sea ice loss triggers novel fall phytoplankton blooms, Geophysical Research Letters, 41, 6207–6212, 2014.

Arrigo, K. R. and van Dijken, G. L.: Continued increases in Arctic Ocean primary production, Progress in Oceanography, 136, 60–70, 2015.

Arrigo, K. R., van Dijken, G., and Pabi, S.: Impact of a shrinking Arctic ice cover on marine primary production, Geophysical Research Letters, 35, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL035028, 2008.

Arrigo, K. R., van Dijken, G. L., Castelao, R. M., Luo, H., Rennermalm, Å. K., Tedesco, M., Mote, T. L., Oliver, H., and Yager, P. L.: Melting glaciers stimulate large summer phytoplankton blooms in southwest Greenland waters, Geophysical Research Letters, 44, 6278–6285, 2017.

Bhatia, M. P., Kujawinski, E. B., Das, S. B., Breier, C. F., Henderson, P. B., and Charette, M. A.: Greenland meltwater as a significant and potentially bioavailable source of iron to the ocean, Nature Geoscience, 6, 274–278, 2013.

Blais, M., Tremblay, J.-É., Jungblut, A. D., Gagnon, J., Martin, J., Thaler, M., and Lovejoy, C.: Nitrogen fixation and identification of potential diazotrophs in the Canadian Arctic, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 26, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GB004096, 2012.

Bonnet, S., Biegala, I. C., Dutrieux, P., Slemons, L. O., and Capone, D. G.: Nitrogen fixation in the western equatorial Pacific: Rates, diazotrophic cyanobacterial size class distribution, and biogeochemical significance, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 23, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GB003439, 2009.

Buchanan, P. J., Chase, Z., Matear, R. J., Phipps, S. J., and Bindoff, N. L.: Marine nitrogen fixers mediate a low latitude pathway for atmospheric CO2 drawdown, Nature Communications, 10, 4611, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12549-z, 2019.

Cantalapiedra, C. P., Hernández-Plaza, A., Letunic, I., Bork, P., and Huerta-Cepas, J.: eggNOG-mapper v2: functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale, Molecular Biology and Evolution, 38, 5825–5829, 2021.

Capone, D. G. and Carpenter, E. J.: Nitrogen fixation in the marine environment, Science, 217, 1140–1142, 1982.

Chen, Y., Chen, Y., Shi, C., Huang, Z., Zhang, Y., Li, S., Li, Y., Ye, J., Yu, C., Li, Z., Zhang, X., Wang, J., Yang, H., Fang, L., and Chen, Q.: SOAPnuke: a MapReduce acceleration-supported software for integrated quality control and preprocessing of high-throughput sequencing data, Gigascience, 7, gix120, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/gix120, 2018.

Cheung, S., Liu, K., Turk-Kubo, K. A., Nishioka, J., Suzuki, K., Landry, M. R., Zehr, J. P., Leung, S., Deng, L., and Liu, H.: High biomass turnover rates of endosymbiotic nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria in the western Bering Sea, Limnology and Oceanography Letters, 7, 501–509, 2022.

Coale, T. H., Loconte, V., Turk-Kubo, K. A., Vanslembrouck, B., Mak, W. K. E., Cheung, S., Ekman, A., Chen, J. H., Hagino, K., Takano, Y., Nishimura, T., Adachi, M., Le Gros, M., Larabell, C., and Zehr, J.: Nitrogen-fixing organelle in a marine alga, Science, 384, 217–222, 2024.

Dähnke, K. and Thamdrup, B.: Nitrogen isotope dynamics and fractionation during sedimentary denitrification in Boknis Eck, Baltic Sea, Biogeosciences, 10, 3079–3088, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-3079-2013, 2013.

Damm, E., Helmke, E., Thoms, S., Schauer, U., Nöthig, E., Bakker, K., and Kiene, R. P.: Methane production in aerobic oligotrophic surface water in the central Arctic Ocean, Biogeosciences, 7, 1099–1108, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-7-1099-2010, 2010.

Díez, B., Bergman, B., Pedrós-Alió, C., Antó, M., and Snoeijs, P.: High cyanobacterial nifH gene diversity in Arctic seawater and sea ice brine, Environmental Microbiology Reports, 4, 360–366, 2012.

Emeis, K.-C., Mara, P., Schlarbaum, T., Möbius, J., Dähnke, K., Struck, U., Mihalopoulos, N., and Krom, M.: External N inputs and internal N cycling traced by isotope ratios of nitrate, dissolved reduced nitrogen, and particulate nitrogen in the eastern Mediterranean Sea, Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 115, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JG001214, 2010.

Fagan, A. J., Tanioka, T., Larkin, A. A., Lee, J. A., Garcia, N. S., and Martiny, A. C.: Elemental stoichiometry of particulate organic matter across the Atlantic Ocean, Biogeosciences, 21, 4239–4250, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-21-4239-2024, 2024.

Falkowski, P. G., Fenchel, T., and Delong, E. F.: The microbial engines that drive Earth's biogeochemical cycles, Science, 320, 1034–1039, 2008.

Farnelid, H., Andersson, A. F., Bertilsson, S., Al-Soud, W. A., Hansen, L. H., Sørensen, S., Steward, G. F., Hagström, Å., and Riemann, L.: Nitrogenase gene amplicons from global marine surface waters are dominated by genes of non-cyanobacteria, PloS one, 6, e19223, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019223, 2011.

Farnelid, H., Turk-Kubo, K., Ploug, H., Ossolinski, J. E., Collins, J. R., Van Mooy, B. A., and Zehr, J. P.: Diverse diazotrophs are present on sinking particles in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, The ISME Journal, 13, 170–182, 2019.

Fernández-Méndez, M., Turk-Kubo, K. A., Buttigieg, P. L., Rapp, J. Z., Krumpen, T., and Zehr, J. P.: Diazotroph diversity in the sea ice, melt ponds, and surface waters of the Eurasian Basin of the Central Arctic Ocean, Frontiers in Microbiology, 7, 217140, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01884, 2016.

Foster, R. A., Goebel, N. L., and Zehr, J. P.: Isolation of calothrix rhizosoleniae (cyanobacteria) strain SC01 from chaetoceros (bacillariophyta) spp. diatoms of the subtropical north pacific ocean 1, Journal of Phycology, 46, 1028–1037, 2010.

Foster, R. A., Kuypers, M. M., Vagner, T., Paerl, R. W., Musat, N., and Zehr, J. P.: Nitrogen fixation and transfer in open ocean diatom–cyanobacterial symbioses, The ISME Journal, 5, 1484–1493, 2011.

Foster, R. A., Tienken, D., Littmann, S., Whitehouse, M. J., Kuypers, M. M., and White, A. E.: The rate and fate of N2 and C fixation by marine diatom-diazotroph symbioses, The ISME journal, 16, 477–487, 2022.

Fox, A. and Walker, B. D.: Sources and Cycling of Particulate Organic Matter in Baffin Bay: A Multi-Isotope δ13C, δ15N, and Δ14C Approach, Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, 846025, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.846025, 2022.

Fu, L., Niu, B., Zhu, Z., Wu, S., and Cd-hit, W. L.: Accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data, Bioinformatics, 28, 3150–3152, 2012.

Galloway, J., Dentener, F., Capone, D., Boyer, E., Howarth, R., Seitzinger, S., Asner, G., Cleveland, C., Green, P., Holland, E., Karl, D., Michaels, A., Porter, J., Townsend, A., and Vöosmarty, C.: Nitrogen cycles: past, present, and future, Biogeochemistry, 70, 153e226, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-004-0370-0, 2004.

García-Robledo, E., Corzo, A., and Papaspyrou, S.: A fast and direct spectrophotometric method for the sequential determination of nitrate and nitrite at low concentrations in small volumes, Marine Chemistry, 162, 30–36, 2014.

Geider, R. J. and La Roche, J.: Redfield revisited: variability of in marine microalgae and its biochemical basis, European Journal of Phycology, 37, 1–17, 2002.

Gladish, C. V., Holland, D. M., and Lee, C. M.: Oceanic boundary conditions for Jakobshavn Glacier. Part II: Provenance and sources of variability of Disko Bay and Ilulissat icefjord waters, 1990–2011, Journal of Physical Oceanography, 45, 33–63, 2015.

Grosse, J., Bombar, D., Doan, H. N., Nguyen, L. N., and Voss, M.: The Mekong River plume fuels nitrogen fixation and determines phytoplankton species distribution in the South China Sea during low and high discharge season, Limnology and Oceanography, 55, 1668–1680, 2010.

Großkopf, T., Mohr, W., Baustian, T., Schunck, H., Gill, D., Kuypers, M. M., Lavik, G., Schmitz, R. A., Wallace, D. W., and LaRoche, J.: Doubling of marine dinitrogen-fixation rates based on direct measurements, Nature, 488, 361–364, 2012.

Gruber, N.: The dynamics of the marine nitrogen cycle and its influence on atmospheric CO2 variations, in: The ocean carbon cycle and climate, Springer, 97–148, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-2087-2_4, 2004.

Gruber, N. and Galloway, J. N.: An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle, Nature, 451, 293–296, 2008.

Gruber, N. and Sarmiento, J. L.: Global patterns of marine nitrogen fixation and denitrification, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 11, 235–266, 1997.

Haine, T. W., Curry, B., Gerdes, R., Hansen, E., Karcher, M., Lee, C., Rudels, B., Spreen, G., de Steur, L., Stewart, K. D., and Woodgate, R.: Arctic freshwater export: Status, mechanisms, and prospects, Global and Planetary Change, 125, 13–35, 2015.

Hanna, E., Huybrechts, P., Steffen, K., Cappelen, J., Huff, R., Shuman, C., Irvine-Fynn, T., Wise, S., and Griffiths, M.: Increased runoff from melt from the Greenland Ice Sheet: a response to global warming, Journal of Climate, 21, 331–341, 2008.

Hansen, M. O., Nielsen, T. G., Stedmon, C. A., and Munk, P.: Oceanographic regime shift during 1997 in Disko Bay, western Greenland, Limnology and Oceanography, 57, 634–644, 2012.

Harding, K., Turk-Kubo, K. A., Sipler, R. E., Mills, M. M., Bronk, D. A., and Zehr, J. P.: Symbiotic unicellular cyanobacteria fix nitrogen in the Arctic Ocean, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115, 13371–13375, 2018.

Hawkings, J., Wadham, J., Tranter, M., Lawson, E., Sole, A., Cowton, T., Tedstone, A., Bartholomew, I., Nienow, P., Chandler, D., and Telling, J.: The effect of warming climate on nutrient and solute export from the Greenland Ice Sheet, Geochemical Perspectives Letters, 94–104, https://doi.org/10.7185/geochemlet.1510, 2015.

Hawkings, J. R., Wadham, J. L., Tranter, M., Raiswell, R., Benning, L. G., Statham, P. J., Tedstone, A., Nienow, P., Lee, K., and Telling, J.: Ice sheets as a significant source of highly reactive nanoparticulate iron to the oceans, Nature Communications, 5, 1–8, 2014.

Hendry, K. R., Huvenne, V. A., Robinson, L. F., Annett, A., Badger, M., Jacobel, A. W., Ng, H. C., Opher, J., Pickering, R. A., Taylor, M. L., Bates, S. L., Cooper, A., Cushman, G. G., Goodwin, C., Hoy, S., Rowland, G., Samperiz, A., Williams, J. A., Achterberg, E. P., Arrowsmith, C., Brearley, A., Henley, S. F., Krause, J. W., Leng, M. J., Li, T., McManus, J. F., Meredith, M. P., Perkins, R., and Woodward, E. M. S.: The biogeochemical impact of glacial meltwater from Southwest Greenland, Progress in Oceanography, 176, 102126, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2019.102126, 2019.

Holland, D. M., Thomas, R. H., De Young, B., Ribergaard, M. H., and Lyberth, B.: Acceleration of Jakobshavn Isbræ triggered by warm subsurface ocean waters, Nature Geoscience, 1, 659–664, 2008.

Hopwood, M. J., Connelly, D. P., Arendt, K. E., Juul-Pedersen, T., Stinchcombe, M. C., Meire, L., Esposito, M., and Krishna, R.: Seasonal changes in Fe along a glaciated Greenlandic fjord, Frontiers in Earth Science, 4, 15, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2016.00015, 2016.

Hyatt, D., Chen, G.-L., LoCascio, P. F., Land, M. L., Larimer, F. W., and Hauser, L. J.: Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification, BMC Bioinformatics, 11, 1–11, 2010.

Jensen, H. M., Pedersen, L., Burmeister, A., and Winding Hansen, B.: Pelagic primary production during summer along 65 to 72 N off West Greenland, Polar Biology, 21, 269–278, 1999.

Karl, D., Michaels, A., Bergman, B., Capone, D., Carpenter, E., Letelier, R., Lipschultz, F., Paerl, H., Sigman, D., and Stal, L.: Dinitrogen fixation in the world's oceans, The nitrogen cycle at regional to global scales, 47–98, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-3405-9_2, 2002.

Knies, J.: Nitrogen isotope evidence for changing Arctic Ocean ventilation regimes during the Cenozoic, Geophysical Research Letters, 49, e2022GL099512, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL099512, 2022.

Krawczyk, D. W., Yesson, C., Knutz, P., Arboe, N. H., Blicher, M. E., Zinglersen, K. B., and Wagnholt, J. N.: Seafloor habitats across geological boundaries in Disko Bay, central West Greenland, Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 278, 108087, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2022.108087, 2022.

Krupke, A., Mohr, W., LaRoche, J., Fuchs, B. M., Amann, R. I., and Kuypers, M. M.: The effect of nutrients on carbon and nitrogen fixation by the UCYN-A–haptophyte symbiosis, The ISME Journal, 9, 1635–1647, 2015.

Laso Perez, R., Rivas Santisteban, J., Fernandez-Gonzalez, N., Mundy, C. J., Tamames, J., and Pedros-Alio, C.: Nitrogen cycling during an Arctic bloom: from chemolithotrophy to nitrogen assimilation, bioRxiv, 2024–02, https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.27.582273, 2024.

Lewis, K., Van Dijken, G., and Arrigo, K. R.: Changes in phytoplankton concentration now drive increased Arctic Ocean primary production, Science, 369, 198–202, 2020.

Li, D., Liu, C.-M., Luo, R., Sadakane, K., and Lam, T.-W.: MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph, Bioinformatics, 31, 1674–1676, 2015.

Löscher, C. R., Bourbonnais, A., Dekaezemacker, J., Charoenpong, C. N., Altabet, M. A., Bange, H. W., Czeschel, R., Hoffmann, C., and Schmitz, R.: N2 fixation in eddies of the eastern tropical South Pacific Ocean, Biogeosciences, 13, 2889–2899, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-13-2889-2016, 2016.

Löscher, C. R., Mohr, W., Bange, H. W., and Canfield, D. E.: No nitrogen fixation in the Bay of Bengal?, Biogeosciences, 17, 851–864, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-851-2020, 2020.

Löscher, C. R., Schlangen, I., Leon-Palmero, E., Moser, A., Xu, P., and Laursen, E.: Hydrographic and Biogeochemical Profiles of Disco Bay: High-Resolution CTD Measurements, PANGAEA [data set], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.973563, 2025a.

Löscher, C. R., Schlangen, I., Leon-Palmero, E., Moser, A., Xu, P., and Laursen, E.: Hydrographic and Biogeochemical Profiles of Disco Bay: High-Resolution Nitrogen Cycling Experimental Data, PANGAEA [data set], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.973564, 2025b.

Luo, Y.-W., Doney, S. C., Anderson, L. A., Benavides, M., Berman-Frank, I., Bode, A., Bonnet, S., Boström, K. H., Böttjer, D., Capone, D. G., Carpenter, E. J., Chen, Y. L., Church, M. J., Dore, J. E., Falcón, L. I., Fernández, A., Foster, R. A., Furuya, K., Gómez, F., Gundersen, K., Hynes, A. M., Karl, D. M., Kitajima, S., Langlois, R. J., LaRoche, J., Letelier, R. M., Marañón, E., McGillicuddy Jr., D. J., Moisander, P. H., Moore, C. M., Mouriño-Carballido, B., Mulholland, M. R., Needoba, J. A., Orcutt, K. M., Poulton, A. J., Rahav, E., Raimbault, P., Rees, A. P., Riemann, L., Shiozaki, T., Subramaniam, A., Tyrrell, T., Turk-Kubo, K. A., Varela, M., Villareal, T. A., Webb, E. A., White, A. E., Wu, J., and Zehr, J. P.: Database of diazotrophs in global ocean: abundance, biomass and nitrogen fixation rates, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 4, 47–73, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-4-47-2012, 2012.

Martínez-Pérez, C., Mohr, W., Löscher, C. R., Dekaezemacker, J., Littmann, S., Yilmaz, P., Lehnen, N., Fuchs, B. M., Lavik, G., Schmitz, R. A., LaRoche, J., and Kuypers, M. M. M.: The small unicellular diazotrophic symbiont, UCYN-A, is a key player in the marine nitrogen cycle, Nature Microbiology, 1, 1–7, 2016.

Mills, M. M., Turk-Kubo, K. A., van Dijken, G. L., Henke, B. A., Harding, K., Wilson, S. T., Arrigo, K. R., and Zehr, J. P.: Unusual marine cyanobacteria/haptophyte symbiosis relies on N2 fixation even in N-rich environments, The ISME Journal, 14, 2395–2406, 2020.

Mohr, W., Grosskopf, T., Wallace, D. W., and LaRoche, J.: Methodological underestimation of oceanic nitrogen fixation rates, PloS One, 5, e12583, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0012583, 2010.

Montoya, J. P.: Nitrogen stable isotopes in marine environments, Nitrogen in the Marine Environment, 2, 1277–1302, 2008.

Montoya, J. P., Voss, M., Kahler, P., and Capone, D. G.: A simple, high-precision, highsensitivity tracer assay for N (inf2) fixation, Applied and environmental microbiology, 62, 986–993, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.62.3.986-993.1996, 1996.

Montoya, J. P., Carpenter, E. J., and Capone, D. G.: Nitrogen fixation and nitrogen isotope abundances in zooplankton of the oligotrophic North Atlantic, Limnology and Oceanography, 47, 1617–1628, 2002.

Mortensen, J., Rysgaard, S., Winding, M., Juul-Pedersen, T., Arendt, K., Lund, H., Stuart-Lee, A., and Meire, L.: Multidecadal water mass dynamics on the West Greenland Shelf, Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 127, e2022JC018724, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JC018724, 2022.

Munk, P., Nielsen, T. G., and Hansen, B. W.: Horizontal and vertical dynamics of zooplankton and larval fish communities during mid- summer in Disko Bay, West Greenland, Journal of Plankton Research, 37, 554–570, 2015.

Murphy, J. and Riley, J. P.: A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters, Analytica Chimica Acta, 27, 31–36, 1962.

Myers, P. G. and Ribergaard, M. H.: Warming of the polar water layer in Disko Bay and potential impact on Jakobshavn Isbrae, Journal of Physical Oceanography, 43, 2629–2640, 2013.

Patro, R., Duggal, G., Love, M. I., Irizarry, R. A., and Kingsford, C.: Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression, Nature Methods, 14, 417–419, 2017.

Pierella Karlusich, J. J., Pelletier, E., Lombard, F., Carsique, M., Dvorak, E., Colin, S., Picheral, M., Cornejo-Castillo, F. M., Acinas, S. G., Pepperkok, R., Karsenti, E., De Vargas, C., Wincker, P., Bowler, C., and Foster, R. A.: Global distribution patterns of marine nitrogenfixers by imaging and molecular methods, Nature Communications, 12, 4160, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24299-y, 2021.

Quigg, A., Finkel, Z. V., Irwin, A. J., Rosenthal, Y., Ho, T. Y., Reinfelder, J. R., Schofield, O., Morel, F. M. and Falkowski, P. G.: The evolutionary inheritance of elemental stoichiometry in marine phytoplankton, Nature, 425, 291–294, 2003.

Redfield, A. C.: On the proportions of organic derivatives in sea water and their relation to the composition of plankton, Vol. 1, Liverpool: University Press of Liverpool, 1934.

Reeder, C. F., Stoltenberg, I., Javidpour, J., and Löscher, C. R.: Salinity as a key control on the diazotrophic community composition in the southern Baltic Sea, Ocean Sci., 18, 401–417, https://doi.org/10.5194/os-18-401-2022, 2022.

Rees, A. P., Gilbert, J. A., and Kelly-Gerreyn, B. A.: Nitrogen fixation in the western English Channel (NE Atlantic ocean), Marine Ecology Progress Series, 374, 7–12, 2009.

Robicheau, B. M., Tolman, J., Rose, S., Desai, D., and LaRoche, J.: Marine nitrogen-fixers in the Canadian Arctic Gateway are dominated by biogeographically distinct noncyanobacterial communities, FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 99, 122, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiad122, 2023.

Rysgaard, S., Boone, W., Carlson, D., Sejr, M., Bendtsen, J., Juul-Pedersen, T., Lund, H., Meire, L., and Mortensen, J.: An updated view on water masses on the pan-west Greenland continental shelf and their link to proglacial fjords, Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 125, e2019JC015564, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JC015564 2020.

Schiøtt, S.: The Marine Ecosystem of Ilulissat Icefjord, Greenland, PhD thesis, Department of Biology, Aarhus University, Denmark, https://pure.au.dk/portal/en/publications/the-marine-ecosystem-of-ilulissat-icefjord-greenland/ (last accessed: 17 November 2025), 2023.

Schlitzer, R.: Ocean data view, https://odv.awi.de (last access: 15 May 2025), 2022.

Schneider, B., Schlitzer, R., Fischer, G., and Nöthig, E. M.: Depth-dependent elemental compositions of particulate organic matter (POM) in the ocean, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 17, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GB001871, 2003.

Schvarcz, C. R., Wilson, S. T., Caffin, M., Stancheva, R., Li, Q., Turk-Kubo, K. A., White, A. E., Karl, D. M., Zehr, J. P., and Steward, G. F.: Overlooked and widespread pennate diatom-diazotroph symbioses in the sea, Nature Communications, 13, 799, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28065-6, 2022.

Shao, Z., Xu, Y., Wang, H., Luo, W., Wang, L., Huang, Y., Agawin, N. S. R., Ahmed, A., Benavides, M., Bentzon-Tilia, M., Berman-Frank, I., Berthelot, H., Biegala, I. C., Bif, M. B., Bode, A., Bonnet, S., Bronk, D. A., Brown, M. V., Campbell, L., Capone, D. G., Carpenter, E. J., Cassar, N., Chang, B. X., Chappell, D., Chen, Y.-L., Church, M. J., Cornejo-Castillo, F. M., Detoni, A. M. S., Doney, S. C., Dupouy, C., Estrada, M., Fernandez, C., Fernández-Castro, B., Fonseca-Batista, D., Foster, R. A., Furuya, K., Garcia, N., Goto, K., Gago, J., Gradoville, M. R., Hamersley, M. R., Henke, B. A., Hörstmann, C., Jayakumar, A., Jiang, Z., Kao, S.-J., Karl, D. M., Kittu, L. R., Knapp, A. N., Kumar, S., LaRoche, J., Liu, H., Liu, J., Lory, C., Löscher, C. R., Marañón, E., Messer, L. F., Mills, M. M., Mohr, W., Moisander, P. H., Mahaffey, C., Moore, R., Mouriño-Carballido, B., Mulholland, M. R., Nakaoka, S., Needoba, J. A., Raes, E. J., Rahav, E., Ramírez-Cárdenas, T., Reeder, C. F., Riemann, L., Riou, V., Robidart, J. C., Sarma, V. V. S. S., Sato, T., Saxena, H., Selden, C., Seymour, J. R., Shi, D., Shiozaki, T., Singh, A., Sipler, R. E., Sun, J., Suzuki, K., Takahashi, K., Tan, Y., Tang, W., Tremblay, J.-É., Turk-Kubo, K., Wen, Z., White, A. E., Wilson, S. T., Yoshida, T., Zehr, J. P., Zhang, R., Zhang, Y., and Luo, Y.-W.: Global oceanic diazotroph database version 2 and elevated estimate of global oceanic N2 fixation, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 15, 3673–3709, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-3673-2023, 2023.

Sherwood, O. A., Davin, S. H., Lehmann, N., Buchwald, C., Edinger, E. N., Lehmann, M. F., and Kienast, M.: Stable isotope ratios in seawater nitrate reflect the influence of Pacific water along the northwest Atlantic margin, Biogeosciences, 18, 4491–4510, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-18-4491-2021, 2021.

Shiozaki, T., Bombar, D., Riemann, L., Hashihama, F., Takeda, S., Yamaguchi, T., Ehama, M., Hamasaki, K., and Furuya, K.: Basin scale variability of active diazotrophs and nitrogen fixation in the North Pacific, from the tropics to the subarctic Bering Sea, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 31, 996–1009, 2017.

Shiozaki, T., Fujiwara, A., Ijichi, M., Harada, N., Nishino, S., Nishi, S., Nagata, T., and Hamasaki, K.: Diazotroph community structure and the role of nitrogen fixation in the nitrogen cycle in the Chukchi Sea (western Arctic Ocean), Limnology and Oceanography, 63, 2191–2205, 2018.

Shiozaki, T., Fujiwara, A., Inomura, K., Hirose, Y., Hashihama, F., and Harada, N.: Biological nitrogen fixation detected under Antarctic sea ice, Nature Geoscience, 13, 729–732, 2020.

Shiozaki, T., Nishimura, Y., Yoshizawa, S., Takami, H., Hamasaki, K., Fujiwara, A., Nishino, S., and Harada, N.: Distribution and survival strategies of endemic and cosmopolitan diazotrophs in the Arctic Ocean, The ISME Journal, 17, 1340–1350, 2023.

Sigman, D. M., DiFiore, P. J., Hain, M. P., Deutsch, C., Wang, Y., Karl, D. M., Knapp, A. N., Lehmann, M. F., and Pantoja, S.: The dual isotopes of deep nitrate as a constraint on the cycle and budget of oceanic fixed nitrogen, Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 56, 1419–1439, 2009.

Sipler, R. E., Gong, D., Baer, S. E., Sanderson, M. P., Roberts, Q. N., Mulholland, M. R., and Bronk, D. A.: Preliminary estimates of the contribution of Arctic nitrogen fixation to the global nitrogen budget, Limnology and Oceanography Letters, 2, 159–166, 2017.

Slawyk, G., Collos, Y., and Auclair, J.-C.: The use of the 13C and 15N isotopes for the simultaneous measurement of carbon and nitrogen turnover rates in marine phytoplankton 1, Limnology and Oceanography, 22, 925–932, 1977.

Sohm, J. A., Webb, E. A., and Capone, D. G.: Emerging patterns of marine nitrogen fixation, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 9, 499–508, 2011.

Sterner, R. W. and Elser, J. J. Ecological stoichiometry: the biology of elements from molecules to the biosphere, in: Ecological stoichiometry, Princeton University Press, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400885695, 2003.

Tanioka, T., Garcia, C. A., Larkin, A. A., Garcia, N. S., Fagan, A. J., and Martiny, A. C.: Global patterns and predictors of in marine ecosystems, Communications Earth & Environment, 3, 271, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00603-6, 2022.

Tang, W., Wang, S., Fonseca-Batista, D., Dehairs, F., Gifford, S., Gonzalez, A. G., Gallinari, M., Planquette, H., Sarthou, G., and Cassar, N.: Revisiting the distribution of oceanic N2 fixation and estimating diazotrophic contribution to marine production, Nature Communications, 10, 831, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08640-0, 2019.