the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Vegetation-mediated surface soil organic carbon formation and potential carbon loss risks in Dongting Lake floodplain, China

Liyan Wang

Zhengmiao Deng

Yonghong Xie

Tao Wang

Feng Li

Ye'ai Zou

Buqing Wang

Zhitao Huo

Cicheng Zhang

Changhui Peng

Andrew Macrae

Sources and stabilization mechanisms of soil organic carbon (SOC) fundamentally govern the carbon sequestration potential of wetland ecosystems. Nevertheless, systematic investigations regarding SOC sources and molecular stability remain scarce in floodplain wetland environments. This study employed dual analytical approaches (stable isotope analysis and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy) to characterize surface SOC composition (0–20 cm) across three dominant vegetation communities (Miscanthus, Carex, and mudflat) in Dongting Lake floodplain wetlands. Key findings revealed: (1) Significantly elevated SOC concentrations in vegetated communities (Miscanthus: 13.76 g kg−1; Carex: 12.98 g kg−1) compared to unvegetated mudflat (6.88 g kg−1); (2) Distinct δ13C signatures across communities, with the highest isotopic values in Miscanthus (−22.67 ‰), intermediate in mudflat (−26.01 ‰), and most depleted values in Carex (−28.25 ‰); (3) Bayesian mixing models identified autochthonous plant biomass as the primary SOC source (Miscanthus: 53.3 %±10.6 %, Carex: 52.4 %±11.6 %, mudflat: 47.5 %±12.5 %); (4) Spatial heterogeneity in particulate organic matter (POM)contributions across sub-lakes, showing descending contributions from South (highest) > West > East (lowest) Dongting Lake; (5) Molecular characterization revealed O-alkyl C dominance (30.5 %–46.8 %), followed by alkyl C and aromatic C. Notably, Miscanthus soils exhibited enhanced content (44.75 %) (: 3.64) and reduced aromaticity (0.22) / hydrophobicity (0.68) indices, suggesting comparatively lower biochemical stability of its SOC pool. These results highlight the critical role of vegetation-mediated SOC formation processes and warn against potential carbon loss risks in Miscanthus-dominated floodplain ecosystems, providing a scientific basis for carbon management of wetland soils.

- Article

(3118 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(452 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Although wetlands occupy merely 5 %–8 % of the global terrestrial surface, they disproportionately store 20 %–30 % of the terrestrial carbon, positioning them as pivotal regulators in global carbon cycling (Kayranli et al., 2010; Köchy et al., 2015; Mitsch et al., 2013). Small changes in wetland soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks may have large feedback effects on climate-carbon cycle interactions. The long-term carbon sequestration capacity of wetland ecosystems is jointly governed by two critical factors: carbon input dynamics and biochemical stabilization mechanisms. Therefore, clarifying the sources and stabilization pathways of wetland SOC is essential for optimizing carbon sink management and enhancing climate change mitigation strategies.

In floodplain systems, the organic carbon in sediment derives from both autochthonous (in-situ plant biomass and aquatic plankton) and allochthonous sources (river-transported particulate organic matter, POM) (Robertson et al., 1999). The sources of SOC vary significantly among different vegetation communities, depending on vegetation characteristics and hydrological conditions (Ni et al., 2025; Guo et al., 2025). For instance, in mangrove ecosystems, SOC is primarily derived from mangrove plant tissues, whereas in adjacent S. alterniflora marshes and tidal flats, it relies more heavily on fluvially imported particulate organic matter (POM) (Wang et al., 2024a). Vegetation influences SOC sources mainly through plant productivity and litter decomposition rates, while hydrological conditions regulate the input and deposition of allochthonous carbon (Guo et al., 2025; Xia et al., 2021). Moreover, even within the same type of vegetation community, SOC sources may exhibit spatial heterogeneity due to local topographic features and anthropogenic activities, leading to the accumulation of allochthonous carbon (Swinnen et al., 2020). Despite these insights, critical knowledge gaps persist regarding interspecific differences in carbon sourcing among co-occurring vegetation communities within floodplain wetlands and the spatial scaling of these heterogeneities. Stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes have been widely used to analyze the sources of wetland SOC (Sasmito et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2021a).

SOC stability is defined as the capacity of organic compounds to resist changes and/or losses (Doetterl et al., 2016). Enhanced SOC stability typically corresponds with preferential accumulation of recalcitrant compounds that withstand microbial degradation. 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is widely used to analyze the chemical composition of SOC, and can calculate the relative abundance of various C functional groups closely related to SOC decomposition (Shen et al., 2018). Biochemically recalcitrant components include alkyl-C and aromatic-C, whereas labile components comprise O-alkyl-C and carbonyl-C (Skjemstad et al., 1994). Consequently, soils enriched in labile SOC fractions demonstrate heightened vulnerability to carbon loss through accelerated decomposition pathways, particularly under environmental disturbance. These molecular signatures are regulated by fators, including vegetation inputs (via lignin/cellulose ratios and aliphatic content), soil properties (clay-silt particle associations), and climatic controls on vegetation litter decomposition (Cano et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2022; Preston et al., 1994; Quideau et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2020). In floodplain environments, hydrologic conditions further regulate SOC components by affecting oxygen supply and altering microbial metabolism and enzyme activity (Kirk and Farrell, 1987; Boye et al., 2017). However, there are insufficient studies on the sources and stability of SOC in floodplain wetlands.

Dongting Lake, a Yangtze River-connected floodplain wetland, presents an ideal natural laboratory for investigating these processes. Its elevation-dependent vegetation zonation and complex topography create pronounced gradients in carbon source inputs and stabilization conditions. Among soil carbon pools, surface SOC is more susceptible to the effects of climate, hydrological conditions and human activities, resulting in a high carbon turnover rate and requiring more attention. In this study, stable isotope techniques were used to analyze the source of surface SOC and the stability of SOC was further evaluated using the 13C NMR method. The hypotheses of this study were as follows: (1) Regarding vegetation communities, SOC content was expected to be highest in the Miscanthus community, intermediate in the Carex community, and lowest in the mudflat. This was based on the corresponding gradient in plant biomass input. Spatially, a gradient of East > South > West Dongting Lake was anticipated, owing to the longer inundation durations in East Dongting Lake, which promote anaerobic conditions that suppress SOC decomposition. (2) SOC in the Miscanthus and Carex communities would be primarily originate from autochthonous plant sources, driven by in-situ plant litter deposition. In contrast, SOC in the mudflat would primarily originate from allochthonous, derived from particulate organic matter delivered by hydrological processes due to the lack of local vegetation. (3) Due to differences in SOC sources, the SOC structure in the Miscanthus and Carex communities was hypothesized to be dominated by O-alkyl C (reflecting plant-derived carbohydrates like cellulose). Conversely, the SOC in the mudflat was expected to be richer in aromatic C, as allochthonous organic matter often contains more recalcitrant components.

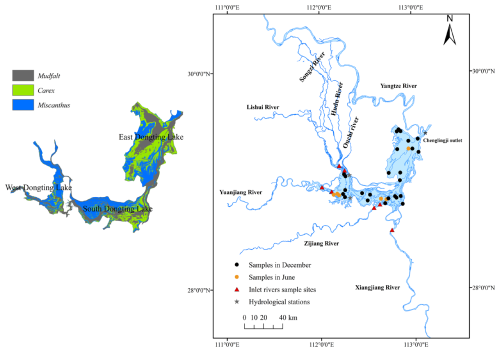

2.1 Study areas

Dongting Lake (28°30′–30°20′ N, 111°40′–113°10′ E) is the second largest inland freshwater lake in China, with an area of 2564 km2. It comprises East Dongting Lake (EDL, 1327.8 km2), West Dongting lake (WDL, 443.9 km2) and South Dongting Lake (SDL, 920 km2) (Gao et al., 2001). The Lake is a typical river-connected lake that mainly receives inflow from the Yangtze River through three channels (the Songzi, Hudu, and Ouchi Rivers) and other four tributaries (the Xiang, Zi, Yuan, and Li Rivers) and then outflows into the Yangtze River from the Chenglingji outlet (Deng et al., 2018). The lake's water level exhibits significant seasonal fluctuations, with flood periods occurring from June to October. From the water's edge to the uplands, the dominant vegetation communities include Mudflat communities, Carex spp. (Cyperaceae) communities, and Miscanthus sacchariflorus (Poaceae) communities (Xie et al., 2015). The study area is characterized by a humid subtropical monsoon climate with a mean annual temperature of 16.8 °C and a mean annual precipitation of 1382 mm.

2.2 Field sampling and parameter measurement

Soil sampling was conducted across three dominant vegetation during December 2022, with supplementary Mudflat sediment sampling in June to account for hydrological accessibility constraints. The final sampling comprised 31 sampling sites (11 Mudflat, 8 Carex community, 12 Miscanthus community) with latitude and longitude recorded using a hand-held global positioning system (GPS). Notably, Carex communities in West Dongting Lake were excluded from sampling due to insufficient population density. At each sampling site, a 1 m×1 m sample plot was set up, and surface (0–20 cm, 500 g fresh soil) soil samples were collected from five points in the plot and mixed for subsequent analysis. For vegetated sites (Carex and Miscanthus communities), aboveground tissue, surface litter layer and belowground roots were collected from the sample plots. All samples were transported to the laboratory. Soil samples were air-dried in a cool, ventilated area and passed through a 2 mm sieve. The sieved soil was split into two portions by quartering, with one portion being finely ground to pass through a 0.147 mm sieve for subsequent analysis. Plant material was dried at 60 °C to a constant mass and the dry weight was recorded prior to pulverization. Both SOC and plant organic carbon content was quantified using the potassium dichromate-sulfuric acid oxidation technique. The TN content of soil was measured using an elemental analyzer (Vario MAX CNS, Elementar, Germany). The formula for calculating vegetation organic carbon stocks (VOCS) is as follows:

Where A is the vegetation distribution area (km2), VB is the vegetation biomass (t km−2), VOC is the vegetation organic carbon content (t C (t biomass)−1.

2.3 Inundation duration and runoff volume

We used the hydrological data from Chenglingji, Xiaohezui, and Nanzui hydrological stations to calculate the inundation time and runoff volume of EDL, SDL, and WDL, respectively. The hydrological data from Chenglingji, Xiaohezui and Nanzui have been widely used to analyze the hydrological characteristics of EDL, SDL and WDL. Vegetation is classified as submerged when water levels exceed specific elevations. Using daily water levels and elevation data from the Dongting Lake Wetland DEM produced by Changjiang Water Resources Commission of the Ministry of Water Resources, China,we calculated vegetation-specific inundation durations. The inundation duration (ID) for each site was calculated as the total number of days within a year when the daily water depth (WD) was greater than zero. This was computed using a daily indicator function, summed over the entire year:

where n is the total number of days in a year, i is the day index, and is the indicator function which takes the value of 1 if the condition WDi>0 is true on the ith day, and 0 otherwise.

The daily water depth WDi was computed as:

where WLi is the daily water level (m) at the Chenglingji (EDL), Xiaohezui (SDL), and Nanzui (WDL) Hydrological Stations, and E is the elevation (m).

2.4 Stable isotope analysis and mixing model

The soil samples (2 g) were added to 0.5 mol L−1 hydrochloric acid reflections for 24 h to removal carbonates, then washed to neutrality with distilled water and dried at 55 °C. The treated soil samples were ground through a 0.147 mm sieve and used for stable isotope measurements. δ13C and δ15N stable isotope ratios were measured using the Element Analyses-Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (EA-IRMS) (Delta V advantage, Thermo Fisher) and were calculated from the following equation:

where Rsample is the stable or isotope ratio of the sample, and Rstandard is stable the or isotope ratios of the international isotope standard (Vienna Peedee Belemnite and N2 in the atmosphere, respectively).

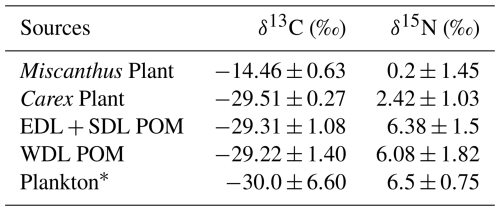

SOC potential sources include Miscanthus plant, Carex plant and Plankton, and rivers suspended particulate organic matter (POM). In addition to plankton, we collected other potential end-members for stable isotope analysis. Five samples of aboveground tissues, surface litter and root of Miscanthus and Carex plants were randomly sampled. Due to the construction of the Three Gorges Dam, the POM entering Dongting Lake changed from three channels (the Songzi, Hudu, and Ouchi Rivers) to four tributaries (the Xiang, Zi, Yuan, and Li Rivers) (Wang et al., 2024b). Therefore, we collected POM at the inlets of the Xiang, Zi, Yuan, and Li Rivers into the lake. The POM from the Yuan and Li Rivers served as the allochthonous end-members for WDL, while the POM from the Xiang, Zi, Yuan, and Li Rivers served as the allochthonous end-members for EDL and SDL (Fig. 1).

Source contributions were quantified using a Bayesian mixing model based on δ13C and δ15N. The MixSIAR model combines the advantages of SIAR and MixSIR. It not only introduces fixed and random effects, but also incorporates source uncertainty. These features endow the MixSIAR model with higher source analysis accuracy, and it has been widely used in wetland sediments (Zhang et al., 2024). In the Bayesian mixing model, the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm was set to “normal”. Model convergence was assessed using Gelman–Rubin diagnostics and Geweke diagnostics (Stock and Semmens, 2016). Additionally, an “uninformative”prior was selected, and the error structure was defined as “residual and process error”.

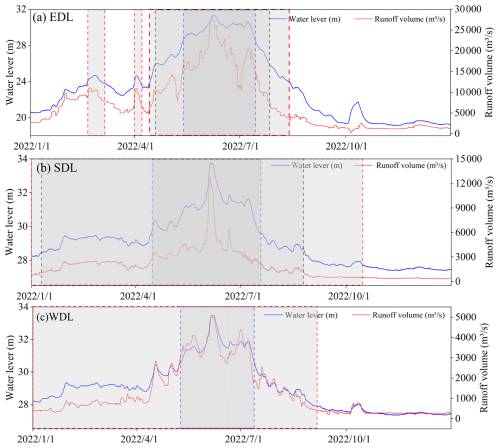

Figure 2Water level, Runoff volume and inundation duration in EDL, SDL, and WDL. In the figure, the shaded part represents submerged, with the red, black, and blue dashed boxes respectively indicating the Mudflat, Carex, and Miscanthus communities. EDL: East Dongting Lake; SDL: South Dongting Lake; WDL: West Dongting Lake.

2.5 13C NMR analysis and spectral indices

The chemical structure of SOC was determined by solid-state 13C NMR spectroscopy. In order to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, soil samples are pretreated with hydrofluoric acid (HF) before 13C NMR spectroscopy analysis. Soil samples (8.0 g) were placed into 100 mL plastic centrifuge tubes containing 50 mL of 10 % () HF solution. The tubes were shaken on a shaking bed at 200 rpm for 1 h at 25 °C, then centrifuged at 3800 rpm for 5 min. After discarding the supernatant, the residual soil was subjected to repeated HF treatments under identical conditions. The entire procedure was conducted 8 times with the following shaking durations: 1 h for the first 4 cycles, 12 h for cycles 5–7, and 24 h for the final cycle. The treated residue was washed 5–6 times with distilled water to remove the HF solution. The residue was dried in an oven at 40° and sieved through 0.25 mm sieve. Subsequently, pretreated samples were analyzed using a Bruker AVANCE III HD 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with an H/X dual-resonance solid probe, operating in CP/MAS mode. Experimental parameters were set as follows: 4 mm ZrO2 rotor spinning at 10 kHz, 13C detection resonance frequency of 150 MHz, acquisition time of 6.25 µs, and spectral width of 30 kHz.

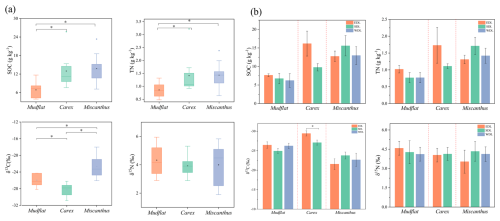

Figure 4Characteristics of SOC, TN, δ13C and δ15N with vegetation types (a), and in different sub lakes (b). EDL: East Dongting Lake; SDL: South Dongting Lake; WDL: West Dongting Lake. * Indicates significant differences between different vegetation types at the P<0.05 level.

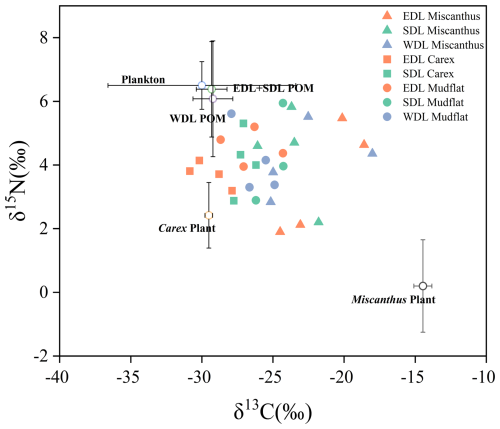

Figure 5The end-element plots of δ13C and δ15N values for samples of Dongting Lake soil and SOC sources. EDL: East Dongting Lake; SDL: South Dongting Lake; WDL: West Dongting Lake.

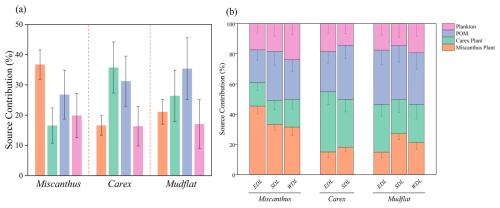

Figure 6Relative contributions of SOC sources with vegetation types (a) and in different sub lakes (b). POM: particulate organic matter; EDL: East Dongting Lake; SDL: South Dongting Lake; WDL: West Dongting Lake.

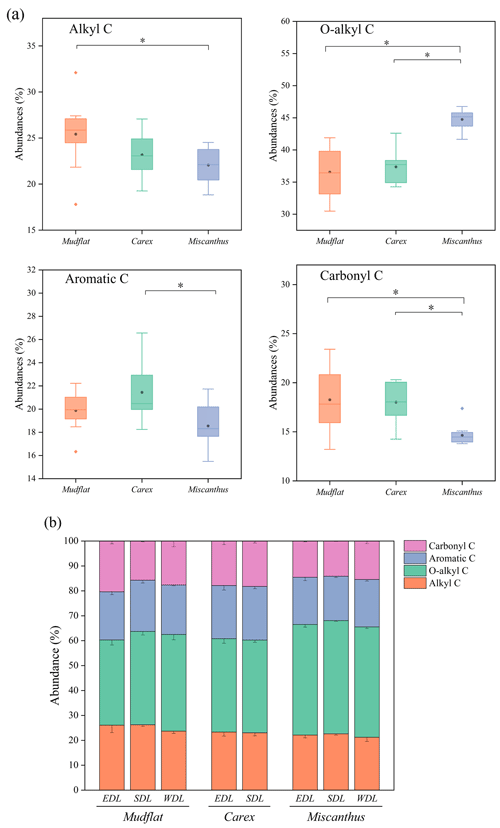

Figure 7SOC functional group abundance in different vegetation types (a) and in different sub lakes (b). EDL: East Dongting Lake; SDL: South Dongting Lake; WDL: West Dongting Lake.

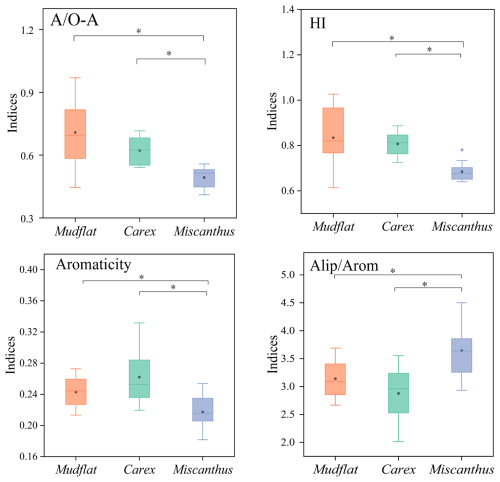

Figure 8SOC stability index for different vegetation types. : the ratio of alkyl C over O-alkyl C; HI: hydrophobicity index, the ratio of the sum of alkyl and aromatic C over the sum of O-alkyl and carbony C; , the ratio of the sum of alkyl C and O-alkyl C over aromatic C; AI, aromaticity index, the ratio of aromatic C over the sum of alkyl C, O-alkyl C and aromatic C.

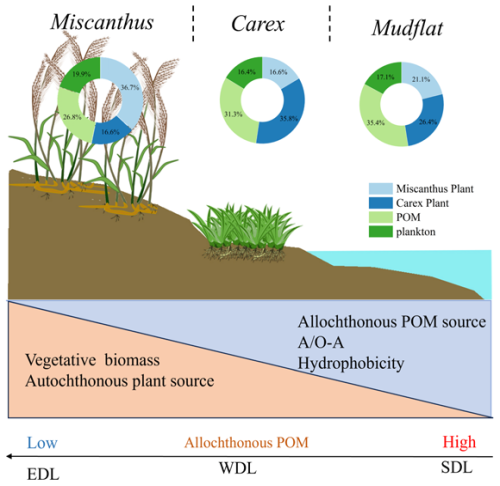

Figure 9A conceptual map of the sources and stability of SOC on a geomorphic gradient in the Dongting floodplain wetlands. Orange triangles show the decrease in vegetative biomass and autochthonous plant sources from Miscanthus (high elevation) to Mudflat (low elevation). In contrast, blue triangles show increases in allochthonous POM sources, , and hydrophobicity. The arrows below indicate that from SDL to WDL to EDL, the contribution of allochthonous POM is decreasing. : the ratio of alkyl C over O-alkyl C; POM: particulate organic matter; EDL: East Dongting Lake; SDL: South Dongting Lake; WDL: West Dongting Lake.

The spectra of samples were divided in the following chemical shift regions: 0–45 ppm (alkyl C, originating from Microbial metabolites and plant biopolymers), 45–110 ppm (O-alkyl C, derived from carbohydrates), 110–160 ppm (aromatic C, derived from lignin, polypeptides and black carbon) and 160–220 ppm (carbonyl C, derived from fatty acids, amino acids and lipids). The relative abundances of different carbon functional groups were quantitatively determined by integrating their respective peak areas in the solid-state 13C NMR spectra. Subsequent spectral analyses were performed using MestReNova software (12.0.0–20080) for statistical interpretation of the data. SOC spectra of the different communities are provided in the Supplement (Fig. S1). According to (Boeni et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2023), four indicators of the stability of SOC were calculated as:

-

, which is used to indicate the degree of humification of SOC, the higher the value, the more resistant it is to decomposition;

-

, which is used to indicate the complexity of the molecular structure of humus, the higher the ratio, the simpler the molecular structure;

-

aromaticity index (AI), which is used as measure of the complexity of SOC structure;

-

hydrophobicity index (HI), which is used to indicate the stability of SOC integrated with aggregates.

2.6 Statistical analysis

The Shapiro–Wilk test and the Levene test are used respectively to test the regularity and consistency of the data. Differences between community were evaluated through one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); multiple comparisons were performed using the least significant difference (LSD) test. Nonparametric tests were used for data that did not meet homogeneity of variance. A threshold of P<0.05 was used to denote statistically significant differences. Source contributions were quantified using the “MixSIAR” package in R.

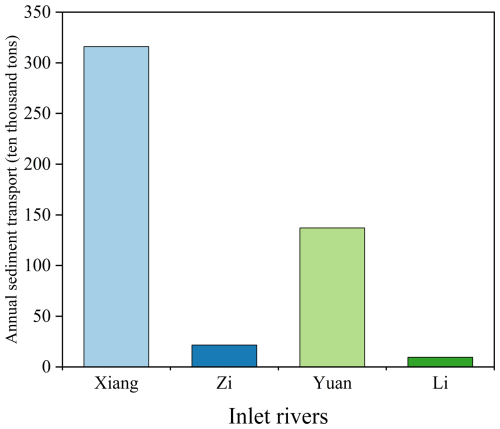

3.1 Hydrological Characteristics of East, South and West Dongting Lakes

The water level of Dongting Lake shows significant fluctuations (19.24–33.78 m) (Fig. 2). There were differences in the inundation duration of different vegetation communities, with the Mudflat having the longest inundation duration (223.8 d), followed by Carex (162.4 d), and Miscanthus having the shortest inundation time (78.9 d). Among the sub-lakes, SDL showed the longest inundation time (206.8 d), followed by WDL (152 d) and EDL (102.8 d). The annual runoff volume was the highest in EDL, followed by SDL and WDL. The annual sediment transport of four tributaries was 484.1×104 t, with the Xiangjiang River having the highest annual sand transport (Fig. 3).

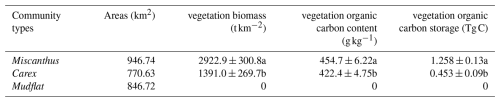

3.2 Carbon sink capacity in dominant vegetation community

The area of Dongting Lake wetland spans 2564.1 km2, with vegetation distribution dominated by the Miscanthus community (36.9 %), followed by the Mudflat (33.0 %) and the Carex community (30.1 %) (Table 1). Miscanthus community exhibited significantly higher plant biomass (2922.9 t km−2) and tissue carbon content (454.7 g kg−1) than Carex community (1391.0 t km−2 and 422.4 g kg−1, respectively; P<0.05). Consequently, its organic carbon stock (1.258±0.13 Tg C) nearly tripled that of Carex communities, representing 72.5 % of the wetland's total vegetation-mediated carbon storage.

3.3 Stable isotope of soil and vegetation

Miscanthus plants displayed the most enriched δ13C values (−13.85 ‰ to −17.24 ‰), contrasting with plankton-derived carbon showing the most depleted signatures. Conversely, δ15N values followed an inverse pattern, with plankton exhibiting the highest enrichment (Table 2). There were differences in SOC and TN contents among community types, with the Miscanthus and Carex communities having significantly higher SOC and TN contents than the Mudflat community (P<0.05, Fig. 4a).

The soil δ13C value ranged from −30.85 ‰ to −18.01 ‰ ( ‰) with the highest values were observed in Miscanthus (−18.01 ‰ to −26.08 ‰ ) (P<0.05, Fig. 4a), followed by Mudflat (−24.3 ‰ to −28.68 ‰) and Carex (−27.08 ‰ to −30.85 ‰). There was no significant difference in soils δ15N values from different vegetation types. EDL Carex communities were smaller in δ13C compared to SDL (P<0.05, Fig. 4b), while other vegetation types showed no significant inter-regional differences in SOC, TN, δ13C or δ15N across sub-basins (Fig. 4b).

3.4 SOC sources and contribution

The isotopic composition of all soil samples fell within the mixing space delineated by potential end-members, confirming their effectiveness in source discrimination (Fig. 5). Our study showed autochthonous plant (including Miscanthus and Carex plant) was the main source of SOC in floodplain wetland (Miscanthus: 53.3 %±10.6 %, Carex: 52.4 %±11.6 %, mudflat: 47.5 %±12.5 %) (Fig. 6a). Allochthonous POM contributions exhibited significant variation across vegetation types, with minimum values in Miscanthus communities (26.8 %±8.1 %) versus Carex (31.3 %±8.3 %) and mudflat (35.4 %±10.2 %).

Spatial heterogeneity in carbon source contributions was evident across vegetation types (Fig. 6b). In Miscanthus communities, EDL demonstrated maximal autochthonous input dominance (12.1 % and 13.9 % greater than SDL and WDL respectively), whereas allochthonous POM displayed inverse spatial patterns (10.9 % and 4.7 % lower than SDL and WDL respectively). In Carex communities, EDL showed 8.1 % higher in autochthonous contributions relative to SDL, concomitant with 9.1 % reduce in POM inputs compared to SDL.

3.5 Chemical structure and SOC stability

SOC functional groups were dominated by O-alkyl C (30.5 %–46.8 %), followed by alkyl C (17.8 %–32.1 %) and aromatic C (15.5 %–26.6 %), with Carbonyl C exhibiting minimal abundance. The highest abundance of alkyl C was observed in mudflat community (25.4 %±1.2 %), followed by Carex (23.2 %±0.9 %), and then Miscanthus community (22.1 %±0.6 %) (P<0.05, Fig. 7a); O-alkyl C shows the opposite trend. The abundances of aromatic C were significantly higher in the Carex community than Miscanthus (Fig. 7a, P<0.05). Carbonyl C showed the same trend as alkyl C. There were no significant changes in the abundance of SOC functional groups across vegetation types in different sub lakes (Fig. 7b).

Stability indices showed that Mudflat and Carex communities had significantly higher ratios, HI indices and aromaticity than Miscanthus (P<0.05), while the ratio showed the opposite pattern (Fig. 8), suggesting that the mudflat and Carex community formed a more stable organic carbon pool through enrichment of difficult-to-degrade fractions, such as alkyl C and aromatic C.

4.1 SOC content in different vegetation types

Our study showed that the SOC content of mudflat community (6.88 g kg−1) was the lowest, and there was no significant difference in SOC content between the two communities (Miscanthus: 13.76 g kg−1 and Carex: 12.99 g kg−1). These results partially support our first hypothesis that SOC content should be the highest in the Miscanthus community, followed by the Carex community, with the mudflat exhibiting the lowest SOC content. Although the vegetation biomass of Miscanthus community (2922.9±300.8 t km−2) was significantly higher than that of Carex community (1391.0±269.7 t km−2), the simpler chemical structure of Miscanthus SOC (Fig. 7) may facilitate its microbial decomposition. The cross-sub-lake comparisons revealed no significant spatial heterogeneity in vegetated SOC content, which was also inconsistent to our first hypothesis. This may be due to the joint influence of vegetation, hydrology and human disturbance on SOC content. The surface SOC content of the Dongting floodplain wetland (11.12 g kg−1) was close to that of the Poyang Lake wetland (9.69 g kg−1) (Yuan et al., 2023), but lower than that of the forested wetland in the middle and lower Elbe River in Germany (33.73 g kg−1) (Heger et al., 2021).

4.2 SOC sources in different vegetation types

Our results showed that autochthonous plant were the main source of SOC (Miscanthus: 53.3 %±10.6 %, Carex: 52.4 %±11.6 %, mudflat: 47.5 %±12.5 %), which partially supports our second hypothesis that SOC in Miscanthus and Carex community would primarily originate from autochthonous plant sources; the source of SOC in the mudflat would primarily originate from allochthonous POM. The SOC of Miscanthus and Carex communities is mainly derived from autochthonous plant which were related to the plant biomass of communities (Miscanthus: 2922.9±300.8 t km−2, Carex: 1391.0±269.7 t km−2) (Table 1). Each year autochthonous plants input a large source of carbon into the soil (Zhu et al., 2022). SOC in the mudflat community was also predominantly derived from autochthonous plants, which can be attributed to reduced allochthonous POM inputs. The commissioning of the Three Gorges Dam in 2003, the world's largest hydropower project, fundamentally altered sediment dynamics, reducing downstream sediment transport from t yr−1 (pre-dam) to a state of net erosion (2×106 t yr−1 post-dam) (Yu et al., 2018). The reductions in river sediment transport diminished allochthonous POM contributions. Autochthonous plants are also a major source of SOC in Poyang Lake (located in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River), riverine wetlands along Mexico's Pacific coast, and coastal wetlands in the Mississippi River delta (Wang et al., 2016; Kelsall et al., 2023; Adame and Fry, 2016). The source of SOC in Dongting floodplain wetland has a part of the source of plankton (14.3 %–23.9 %). This is due to the decline in water quality of the lakes and the gradual increase in algae as a result of problems such as the increased intensity of agricultural farming and the use of chemical fertilizers (Ren et al., 2018).

POM had the highest SOC contribution to the mudflat community (35.4 %±10.2 %), followed by Carex (31.3 %±8.3 %), and the lowest was Miscanthus (26.8 %±8.1 %). This may be related to the different elevations of the vegetation communities (Miscanthus: >25 m, Carex: 22–25 m, Mudflat: <22 m), where higher elevations lead to shorter inundation times, thus limiting particulate organic matter (POM) deposition. In this study, we also found that SDL exhibited the highest POM contribution (32.5 %), followed by WDL (26.3 %), with EDL showing minimal inputs (21.6 %) in Miscanthus communities. A parallel pattern emerged with Carex communities, where SDL's POM contribution exceeded EDL by 9.1 %. This may be due to the following: Firstly, the intensive agricultural activities and urbanization in the Xiangjiang River basins that have increased soil erosion, making more POM enter the SDL (Xiao et al., 2023). Second, the northern part of the SDL receives a large amount of sediment under the top-supporting effect of the outflow of WDL (Zhang et al., 2019). Third, the inundation duration is the longest in the SDL, followed by the WDL, and the EDL has the shortest inundation duration. The extension of inundation duration can improve the deposition of allochthonous POM (Shen et al., 2020). Studies have also shown that the mean mass accumulative rate (MAR) of the SDL is the highest, followed by the WDL, and the EDL is the lowest (Ran et al., 2023). Thus, the spatial heterogeneity of allochthonous POM contributions to SOC across sub-lakes revealed synergistic controls by anthropogenic and hydrodynamic drivers.

4.3 SOC stability in in different vegetation types

Our findings demonstrate that O-alkyl C, primarily derived from carbohydrates, constitutes the dominant fraction (30.5 %–46.8 %) of SOC in Dongting Lake wetlands. This result partially supports our third hypothesis that the structure of SOC in Miscanthus and Carex should be dominated by O-alkyl C, and the SOC structure of the mudflat should be dominated by aromatic C. The predominance of O-alkyl C across vegetation communities likely reflects the autochthonous origin of SOC from plant-derived inputs. Specifically, the cellulose and hemicellulose components of plant litter decompose rapidly to produce carbohydrates (Mckee et al., 2016). O-alkyl C has also been found to be the dominant fraction of SOC in other lakes or river wetland (Yang et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2011).

Notably, the Miscanthus community exhibited significantly higher O-alkyl C content compared to Carex and mudflat, while displaying lower alkyl and aromatic C contents (Fig. 7a). Given that O-alkyl C was classified as labile C whereas alkyl and aromatic C were classified as recalcitrant C, these results showed that Miscanthus community SOC is more unstable and more susceptible to decomposition. Therefore, the risk of SOC loss is higher in the Miscanthus community. The and aromaticity as well as HI and , are recognized as important parameters for evaluating the stability of SOC. The ratio, aromaticity and hydrophobicity index (HI) were significantly higher in the Carex and mudflat communities than Miscanthus community (P<0.05), whereas the ratio showed the opposite trend, indicating that the SOC of Carex and mudflat communities had more complex structures and higher hydrophobicity, which increased SOC stability (Spaccini et al., 2006).

O-alkyl C is primarily derived from carbohydrates. Miscanthus plants possess a well-developed underground root system that may produces more root secretions, which are mainly composed of carbohydrates (Wu et al., 2021b). The higher aromatic and alkyl C fractions observed in Carex and mudflat communities likely result from prolonged inundation duration, which extends exposure to anaerobic conditions. Anoxic conditions significantly limit reactive oxygen species generation and catalase activity, thereby inhibiting oxidative decomposition of lignin (the main component of aromatic carbon) (Benner et al., 1984; Kirk and Farrell, 1987). Additionally, microbial metabolic efficiency declines under oxygen deprivation, retarding the decomposition of lipids and waxes (alkyl carbon precursors) (Keiluweit et al., 2017). These stability difference may be related to the contribution of allochthonous POM. Allochthonous carbon is rich in aromatic and hydrophobic components, exhibiting stronger resistance to decomposition (Keil, 2011). The proportion of allochthonous POM was significantly higher in the Carex and mudflat communities than in the Miscanthus.

The risk of loss of soil carbon pools in Miscanthus community is higher due to the more labile molecular structure of SOC (Fig. 9). In our previous research, we also found that the Miscanthus community experienced the greatest loss of SOC from 2013 to 2022 (Wang et al., 2025b). Although the SOC stability of the Miscanthus community is relatively low, its SOC content shows no significant difference from that of the Carex community due to high litter input (1.258±0.13 Tg C), revealing the differences in the mechanisms of carbon sequestration function formation among different vegetation types in floodplain wetlands (Fig. 9). Therefore, hydrological management strategies such as regulating water levels or extending flood duration could be applied to maintain anaerobic conditions in Miscanthus soil, thereby potentially reducing the decomposition rate and loss of SOC. Although this study evaluated SOC stability primarily from the perspective of chemical composition, unaccounted physical and mineral protection mechanisms likely also play significant roles. Therefore, it is necessary to integrate these protective mechanisms into future research considerations.

Stable isotopic analysis demonstrates that SOC in Dongting floodplain wetlands was mainly derived from autochthonous plant inputs, with mean contributions of 53.3 %±10.6 % (Miscanthus), 52.4 %±11.6 % (Carex), and 47.5 %±12.5 % (mudflat). Notably, allochthonous POM contributions exhibited both vegetation-dependent (mudflat > Carex > Miscanthus) and regional disparities (SDL > WDL > EDL). We attribute these differences to interacting effects of anthropogenic and hydrodynamic drivers, which collectively regulate allochthonous POM transport and deposition. The ratios, aromaticity, and hydrophobicity were lower in Miscanthus community, indicating that SOC is more easily decomposed, and the stability of SOC pools is lower. Therefore, we should prioritize the conservation of Miscanthus communities SOC to mitigate carbon loss risks.

The data used in this paper are stored in the open-access online database Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30781895; Wang et al., 2025a).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-23-39-2026-supplement.

LW: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation. ZD: Writing – review and editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. YX: Writing–review and editing, Funding acquisition. TW: Investigation, Data curation. FL: Writing – review and editing, Methodology. YZ: Investigation, Data curation. BW: Formal analysis, Resources. ZH: Methodology, Data curation. CZ: Investigation, Data curation. CP: Writing – review and editing, Formal analysis. AM: Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which greatly improved the manuscript. We are also grateful to Dr. Susanne Liebner for her guidance throughout the review process. Special thanks go to Miao Li for his invaluable assistance during fieldwork.

This research has been supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant nos. 2023YFF0807202, 2022YFC3204101), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. U2444221, U22A20570), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (grant no. 2025JJ20039), the Science, Technology and Innovation Platform Plan of Hunan Province, China (grant no. 2022PT1010).

This paper was edited by Susanne Liebner and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Adame, M. F. and Fry, B.: Source and stability of soil carbon in mangrove and freshwater wetlands of the Mexican Pacific coast, Wetlands Ecol. Manage., 24, 129–137, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-015-9475-6, 2016.

Benner, R., Maccubbin, A. E., and Hodson, R. E.: Anaerobic Biodegradation of the Lignin and Polysaccharide Components of Lignocellulose and Synthetic Lignin by Sediment Microflora, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 47, 998–1004, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.47.5.998-1004.1984, 1984.

Boeni, M., Bayer, C., Dieckow, J., Conceiçao, P. C., Dick, D. P., Knicker, H., Salton, J. C., and Macedo, M. C. M.: Organic matter composition in density fractions of Cerrado Ferralsols as revealed by CPMAS 13C NMR: Influence of pastureland, cropland and integrated crop-livestock, Agric., Ecosyst. Environ., 190, 80–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.09.024, 2014.

Boye, K., Noël, V., Tfaily, M. M., Bone, S. E., Williams, K. H., Bargar, J. R., and Fendorf, S.: Thermodynamically controlled preservation of organic carbon in floodplains, Nat. Geosci., 10, 415–419, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2940, 2017.

Cano, A. F., Mermut, A. R., Ortiz, R., Benke, M. B., and Chatson, B.: 13C CP/MAS-NMR spectra, of organic matter as influenced by vegetation, climate, and soil characteristics in soils from Murcia, Spain, Can. J. Soil Sci., 82, 403–411, 2002.

Chen, X., Xu, Y. J., Gao, H. J., Mao, J. D., Chu, W. Y., and Thompson, M. L.: Biochemical stabilization of soil organic matter in straw-amended, anaerobic and aerobic soils, Sci. Total Environ., 625, 1065–1073, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.293, 2018.

Deng, Z. M., Li, Y. Z., Xie, Y. H., Peng, C. H., Chen, X. S., Li, F., Ren, Y. J., Pan, B. H., and Zhang, C. Y.: Hydrologic and Edaphic Controls on Soil Carbon Emission in Dongting Lake Floodplain, China, Journal of Geophysical Research-Biogeosciences, 123, 3088–3097, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018jg004515, 2018.

Doetterl, S., Berhe, A. A., Nadeu, E., Wang, Z. G., Sommer, M., and Fiener, P.: Erosion, deposition and soil carbon: A review of process-level controls, experimental tools and models to address C cycling in dynamic landscapes, Earth-Sci. Rev., 154, 102–122, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.12.005, 2016.

Gao, J. F., Zhang, C., Jiang J. H., and Huang, Q.: Changes in Sediment Deposition and Erosion and Their Spatial Distribution in the Dongting Lake, Journal of Geographical Sciences, 11, 402–410, 2001.

Guo, M., Yang, L., Zhang, L., Shen, F. X., Meadows, M. E., and Zhou, C. H.: Hydrology, vegetation, and soil properties as key drivers of soil organic carbon in coastal wetlands: A high-resolution study, Environmental Science and Ecotechnology, 23, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ese.2024.100482, 2025.

Heger, A., Becker, J. N., Navas, L. K. V., and Eschenbach, A.: Factors controlling soil organic carbon stocks in hardwood floodplain forests of the lower middle Elbe River, Geoderma, 404, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2021.115389, 2021.

Kayranli, B., Scholz, M., Mustafa, A., and Hedmark, Å.: Carbon Storage and Fluxes within Freshwater Wetlands: a Critical Review, Wetlands, 30, 111–124, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-009-0003-4, 2010.

Keil, R. G.: Terrestrial influences on carbon burial at sea, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 9729–9730, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1106928108, 2011.

Keiluweit, M., Wanzek, T., Kleber, M., Nico, P., and Fendorf, S.: Anaerobic microsites have an unaccounted role in soil carbon stabilization, Nat. Commun., 8, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01406-6, 2017.

Kelsall, M., Quirk, T., Wilson, C., and Snedden, G. A.: Sources and chemical stability of soil organic carbon in natural and created coastal marshes of Louisiana, Sci. Total Environ., 867, 12, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161415, 2023.

Kendall, C., Silva, S. R., and Kelly, V. J.: Carbon and nitrogen isotopic compositions of particulate organic matter in four large river systems across the United States, Hydrol. Process., 15, 1301–1346, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.216, 2001.

Kirk, T. K. and Farrell, R. L.: Enzymatic combustion – the microbial-degradation of lignin, Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 41, 465–505, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.002341, 1987.

Köchy, M., Hiederer, R., and Freibauer, A.: Global distribution of soil organic carbon – Part 1: Masses and frequency distributions of SOC stocks for the tropics, permafrost regions, wetlands, and the world, SOIL, 1, 351–365, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-1-351-2015, 2015.

Li, Y., Zhang, H. B., Tu, C., Fu, C. C., Xue, Y., and Luo, Y. M.: Sources and fate of organic carbon and nitrogen from land to ocean: Identified by coupling stable isotopes with C N ratio, Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci., 181, 114–122, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2016.08.024, 2016.

Liu, S. Y., Li, J. Y., Liang, A. Z., Duan, Y., Chen, H. B., Yu, Z. Y., Fan, R. Q., Liu, H. Y., and Pan, H.: Chemical Composition of Plant Residues Regulates Soil Organic Carbon Turnover in Typical Soils with Contrasting Textures in Northeast China Plain, Agronomy-Basel, 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12030747, 2022.

McKee, G. A., Soong, J. L., Caldéron, F., Borch, T., and Cotrufo, M. F.: An integrated spectroscopic and wet chemical approach to investigate grass litter decomposition chemistry, Biogeochemistry, 128, 107–123, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-016-0197-5, 2016.

Mitsch, W. J., Bernal, B., Nahlik, A. M., Mander, Ü., Zhang, L., Anderson, C. J., Jorgensen, S. E., and Brix, H.: Wetlands, carbon, and climate change, Landsc. Ecol., 28, 583–597, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-012-9758-8, 2013.

Ni, X., Zhao, G. M., White, J. R., Yao, P., Xu, K. H., Sapkota, Y., Liu, J. C., Zheng, H., Su, D. P., He, L., Liu, Q., Yang, S. X., Yuan, H. M., Ding, X. G., Zhang, Y., and Ye, S. Y.: Source and degradation of soil organic matter in different vegetations along a salinity gradient in the Yellow River Delta wetland, Catena, 248, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2024.108603, 2025.

Preston, C. M., Newman, R. H., and Rother, P.: Using C-13 CPMAS NMR to assess effects of cultivation on the organic-matter of particle-size fractions in a grassland soil, Soil Sci., 157, 26–35, https://doi.org/10.1097/00010694-199401000-00005, 1994.

Quideau, S. A., Chadwick, O. A., Benesi, A., Graham, R. C., and Anderson, M. A.: A direct link between forest vegetation type and soil organic matter composition, Geoderma, 104, 41–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-7061(01)00055-6, 2001.

Ran, F. W., Nie, X. D., Wang, S. L., Liao, W. F., and Li, Z. W.: Evolutionary patterns of the sedimentary environment signified by grain size characteristics in Lake Dongting during the last century, Journal of Lake Sciences, 35, 1111–1125, 2023.

Ren, J. L., Zheng, Z. B., Li, Y. M., Lv, G. N., Wang, Q., Lyu, H., Huang, C. C., Liu, G., Du, C. G., Mu, M., Lei, S. H., and Bi, S.: Remote observation of water clarity patterns in Three Gorges Reservoir and Dongting Lake of China and their probable linkage to the Three Gorges Dam based on Landsat 8 imagery, Sci. Total Environ., 625, 1554–1566, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.036, 2018.

Robertson, A. I., Bunn, S. E., Boon, P. I., and Walker, K. F.: Sources, sinks and transformations of organic carbon in Australian floodplain rivers, Mar. Freshw. Res., 50, 813–829, https://doi.org/10.1071/mf99112, 1999.

Sasmito, S. D., Kuzyakov, Y., Lubis, A. A., Murdiyarso, D., Hutley, L. B., Bachri, S., Friess, D. A., Martius, C., and Borchard, N.: Organic carbon burial and sources in soils of coastal mudflat and mangrove ecosystems, Catena, 187, 11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2019.104414, 2020.

Shen, D. Y., Ye, C. L., Hu, Z. K., Chen, X. Y., Guo, H., Li, J. Y., Du, G. Z., Adl, S., and Liu, M. Q.: Increased chemical stability but decreased physical protection of soil organic carbon in response to nutrient amendment in a Tibetan alpine meadow, Soil Biol. Biochem., 126, 11–21, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.08.008, 2018.

Shen, R. C., Lan, Z. C., Huang, X. Y., Chen, Y. S., Hu, Q. W., Fang, C. M., Jin, B. S., and Chen, J. K.: Soil and plant characteristics during two hydrologically contrasting years at the lakeshore wetland of Poyang Lake, China, J. Soils Sediments, 20, 3368–3379, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-020-02638-8, 2020.

Skjemstad, J. O., Clarke, P., Taylor, J. A., Oades, J. M., and Newman, R. H.: The removal of magnetic-materials from surface soils – a solid-state C-13 CP/MAS NMR-study, Aust. J. Soil Res., 32, 1215–1229, https://doi.org/10.1071/sr9941215, 1994.

Spaccini, R., Mbagwu, J. S. C., Conte, P., and Piccolo, A.: Changes of humic substances characteristics from forested to cultivated soils in Ethiopia, Geoderma, 132, 9–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2005.04.015, 2006.

Stock, B. C. and Semmens, B. X.: MixSIAR GUI User Manual, Version3.1, https://github.com/brianstock/MixSIAR/, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.47719, 2016.

Swinnen, W., Daniëls, T., Maurer, E., Broothaerts, N., and Verstraeten, G.: Geomorphic controls on floodplain sediment and soil organic carbon storage in a Scottish mountain river, Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 45, 207–223, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4729, 2020.

Wang, F. F., Tao, Y. R., Yang, S. C., and Cao, W. Z.: Warming and flooding have different effects on organic carbon stability in mangrove soils, J. Soils Sediments, 10, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-023-03636-2, 2023.

Wang, F. F., Zhang, N., Yang, S. C., Li, Y. S., Yang, L., and Cao, W. Z.: Source and stability of soil organic carbon jointly regulate soil carbon pool, but source alteration is more effective in mangrove ecosystem following Spartina alterniflora invasion, Catena, 235, 12, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.107681, 2024a.

Wang, J. J., Dodla, S. K., DeLaune, R. D., Hudnall, W. H., and Cook, R. L.: Soil Carbon Characteristics in Two Mississippi River Deltaic Marshland Profiles, Wetlands, 31, 157–166, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-010-0130-y, 2011.

Wang, L., Deng, Z., Xie, Y., Wang, T., Li, F., Zou, Y., Wang, B., Huo, Z., Zhang, C., Peng, C., and Macrae, A.: SOC, figshare [data set], https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30781895, 2025a.

Wang, L. Y., Wang, B. Q., Deng, Z. M., Xie, Y. H., Wang, T., Li, F., Wu, S. A., Hu, C., Li, X., Hou, Z. Y., Zeng, J., Zou, Y. A., Liu, Z. L., Peng, C. H., and Andrew, M.: Surface soil organic carbon losses in Dongting Lake floodplain as evidenced by field observations from 2013 to 2022, J. Integr. Agric., 2025b.

Wang, M. L., Lai, J. P., Hu, K. T., and Zhang, D. L.: Compositions of stable organic carbon and nitrogen isotopes in wetland soil of Poyang Lake and its environmental implications, China Environmental Science, 36, 500–505, 2016.

Wang, S. L., Ran, F. W., Li, Z. W., Yang, C. R., Xiao, T., Liu, Y. J., and Nie, X. D.: Coupled effects of human activities and river-Lake interactions evolution alter sources and fate of sedimentary organic carbon in a typical river-Lake system, Water Res., 255, 13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2024.121509, 2024b.

Wu, H., Zhang, H. C., Chang, F. Q., Duan, L. Z., Zhang, X. N., Peng, W., Liu, Q., Zhang, Y., and Liu, F. W.: Isotopic constraints on sources of organic matter and environmental change in Lake Yangzong, Southwest China, Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 217, 11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2021.104845, 2021a.

Wu, J. P., Deng, Q., Hui, D. F., Xiong, X., Zhang, H. L., Zhao, M. D., Wang, X., Hu, M. H., Su, Y. X., Zhang, H. O., Chu, G. W., and Zhang, D. Q.: Reduced Lignin Decomposition and Enhanced Soil Organic Carbon Stability by Acid Rain: Evidence from 13C Isotope and 13C NMR Analyses, Forests, 11, 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/f11111191, 2020.

Wu, Q. Y., Lin, Y. L., Sun, Y. H., Wei, Q. H., Liu, J. T., Li, X. F., and Cui, G. W.: Research Progress on Effects of Root Exudates on Plant Growth and Soil Nutrient Uptake, Chinese Journal of Grassland, 43, 97–104, 2021b.

Xia, S. P., Wang, W. Q., Song, Z. L., Kuzyakov, Y., Guo, L. D., Van Zwieten, L., Li, Q., Hartley, I. P., Yang, Y. H., Wang, Y. D., Quine, T. A., Liu, C. Q., and Wang, H. L.: Spartina alterniflora invasion controls organic carbon stocks in coastal marsh and mangrove soils across tropics and subtropics, Global Change Biology, 27, 1627–1644, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15516, 2021.

Xiao, T., Ran, F. W., Li, Z. W., Wang, S. L., Nie, X. D., Liu, Y. J., Yang, C. R., Tan, M., and Feng, S. R.: Sediment organic carbon dynamics response to land use change in diverse watershed anthropogenic activities, Environ. Int., 172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2023.107788, 2023.

Xie, Y. H., Yue, T., Chen, X. S., Feng, L., Li, F., and Deng, Z. M.: The impact of Three Gorges Dam on the downstream eco-hydrological environment and vegetation distribution of East Dongting Lake, Ecohydrology, 8, 738–746, https://doi.org/10.1002/eco.1543, 2015.

Yang, Y., Jia, G. D., Yu, X. X., and Cao, Y. X.: Land use conversion impacts on the stability of soil organic carbon in Qinghai Lake using 13C NMR and C cycle-related enzyme activities, Land Degrad. Dev., 34, 3606–3617, https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4706, 2023.

Yu, Y. W., Mei, X. F., Dai, Z. J., Gao, J. J., Li, J. B., Wang, J., and Lou, Y. Y.: Hydromorphological processes of Dongting Lake in China between 1951 and 2014, J. Hydrol., 562, 254–266, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.05.015, 2018.

Yuan, J. H., Ren, Q., Zhou, L. Y., Miao, L. J., Chi, Y. Y., Wan, F., Wang, J. P., and Wan, S. X.: Characteristics and influencing factors of soil organic carbon components under different environmental conditions in Poyang Lake wetland, Chinese Jounal of Ecology, 42, 1323–1329, 2023.

Zhang, J. Q., Hao, Q., Li, Q., Zhao, X. W., Fu, X. L., Wang, W. Q., He, D., Li, Y., Zhang, Z. Q., Zhang, X. D., and Song, Z. L.: Source identification of sedimentary organic carbon in coastal wetlands of the western Bohai Sea, Sci. Total Environ., 913, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169282, 2024.

Zhang, W. L., Gu, J. F., Li, Y., Lin, L., Wang, P. F., Wang, C., Qian, B., Wang, H. L., Niu, L. H., Wang, L. F., Zhang, H. J., Gao, Y., Zhu, M. J., and Fang, S. Q.: New Insights into Sediment Transport in Interconnected River–Lake Systems Through Tracing Microorganisms, Environ. Sci. Technol., 53, 4099–4108, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b07334, 2019.

Zhu, L. L., Deng, Z. M., Xie, Y. H., Zhang, C. Y., Chen, X. R., Li, X., Li, F., Chen, X. S., Zou, Y. A., and Wang, W.: Effects of hydrological environment on litter carbon input into the surface soil organic carbon pool in the Dongting Lake floodplain, Catena, 208, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2021.105761, 2022.