the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Ecosystem-scale greenhouse gas fluxes from actively extracted peatlands: water table depth drives interannual variability

Ian B. Strachan

Paul Moore

Sara Knox

Maria Strack

Peat extraction substantially alters a peatland's surface-atmosphere exchange of carbon (C). The sites are drained, their vegetation is removed, and then the peat is vacuum harvested for use as a horticultural growing medium. Despite this disturbance covering only a small percentage of Canadian peatlands, the shift from being a net sink to a net source of C during the typical 15–40 plus years of active extraction makes it an important system to study. Ours is the first study in Canada to conduct ecosystem scale measurements of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) exchange using eddy covariance from actively extracted peatlands. In order to understand environmental drivers of seasonal and interannual patterns of CO2, and seasonal patterns of CH4 fluxes, daytime ecosystem scale measurements of CO2 and CH4, along with average hourly water table depth (WTD) and soil temperature, were conducted from March to October in 2020, 2021 and 2022 at a Western Site (near Drayton Valley, Alberta), and from May to October in 2020 and 2022 at an Eastern Site (near Rivière-du-Loup, Quebec). In contrast to the positive linear relationship observed in my studies, we observed a unimodal CO2–WTD relationship, with fluxes peaking at WTDs of 47 cm. Water table depth drove interannual variability, suggesting that in deeply drained peatlands, we must consider that insufficient surface moisture conditions can reduce soil respiration. Soil temperature had a significant interaction with WTD with positive relationships during moderate and wet periods (WTD <50 cm) and weakly positive to negative relationships during dry periods (WTD >50 cm) with lower explanatory power. Thus, process-based models using soil temperature alone may overestimate fluxes from drained peatlands during dry periods. The sites were small sources of CH4 (mean May to August fluxes of 7.22 mg C m−2 d−1) compared to natural boreal bogs, though we were not able to capture freeze-thaw periods. After making assumptions for missing nighttime and wintertime data, we estimated an annual CO2-C of 112 to 174 g C m−2 yr−1, which is considerably lower than Canada's current Tier 2 emission factor. This research will aid in updating emission factors for peat extraction in Canada, and will help guide industry site management practices.

- Article

(2824 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(3061 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Peatlands are an important ecosystem in Canada, covering around 12 % of the land area (Hugelius et al., 2020; Tarnocai et al., 2011), and accumulating peat under waterlogged conditions resulting in long-term storage of carbon (C) (Yu et al., 2010). Peatland water table drawdown, either through partial drainage for resource extraction and infrastructure, or due to climate change induced drought, alters their C balance (Harris et al., 2020; Kitson and Bell, 2020; Strack et al., 2006). One cause of peatland drainage in Canada is the extraction of peatlands to produce horticultural growing media (Cleary et al., 2005; Sharma et al., 2025). Peat extraction affects less than 0.03 % (24964 ha) of Canadian peatlands and accounts for around 1.2 % of total peatland disturbance in Canada, with disturbance being primarily driven by agriculture and mining activities (Rochefort et al., 2022). However, the long extraction duration of a site, and the shift from it being a net sink to a net source of C following vegetation removal (Clark et al., 2023; Hunter et al., 2024; Waddington et al., 2002) means that a substantial amount of C is lost to the atmosphere from these sites, in addition to the loss of C from the physical removal of the peat (Sharma et al., 2024). In Canada, an estimated 3 Mt of peat is extracted annually, mainly in Quebec, Manitoba, Alberta and New Brunswick, resulting in yearly extraction activity emissions of 1.6 Mt CO2 equivalent (ECCC, 2025). Agricultural disturbance of peatlands, affecting an estimated 1 315 373 ha in Canada (Rochefort et al., 2022), is estimated to results in emissions of 1.4 to 35 Mt CO2 equivalent per year (Strack et al., 2025).

Peat extraction operations alter the hydrology and peat structure (Price, 2003; Kennedy and Price, 2005), thermal properties (Petrone et al., 2004), substrate quality and nutrient status (Basiliko et al., 2007; Glatzel et al., 2004; Kendall, 2021), and microbial community (Bieniada et al., 2023; Reumer et al., 2018) of the peatland, which in turn affect C cycling. To prepare a site for extraction, drainage ditches are created to lower the water table, and then the surface vegetation is removed. In addition to perimeter ditches, interior ditches running the length of the site are cut and spaced every ∼30 m in Canada (Fig. 1). A site is then harvested for 15–40 years through vacuum harvesting, the standard extraction method in Canada since the early 2000s. Briefly, harrowing machines break up the top ∼5 cm layer of the peat, disconnecting it hydrologically from the peat layer below, allowing it to dry out. Harvesting machines vacuum up a portion of this dried peat, where it is transferred to stockpiles to further dry before being removed for processing and sold for use as a growing medium (Cleary et al., 2005). The constant disturbance of the surface layers means that the sites remain unvegetated for the duration of active extraction. The water level in the interior drainage ditches fluctuates based on recent precipitation levels and site management (Hunter et al., 2024). The continued removal of peat each year will expose older, and often more recalcitrant peat to the surface (Clark et al., 2023).

The magnitude of CO2 and CH4 fluxes from actively extracted peatlands, and the seasonal and interannual variability, is poorly understood. Only a few studies have conducted measurements of CO2 and CH4 fluxes from actively extracted peatlands in Canada (Clark et al., 2023; Glatzel et al., 2003; Greenwood, 2005; Hunter et al., 2024). Internationally, there has been more research, predominantly in Finland, Estonia, Sweden, and the United Kingdom (e.g., Salm et al., 2012; Shurpali et al., 2008; Sundh et al., 2000; Vanags-Duka et al., 2022). Most of these studies have focused on CO2 fluxes, and only from the peat fields. We know that the drainage ditches are an important component of the C balance, with recent studies finding that they have at least double CO2 emissions, and increase seven-fold the emissions of CH4 of the fields (Clark et al., 2023; Hunter et al., 2024). While multiple studies have been conducted at post-extracted unrestored peatlands, many contain non-functioning drainage ditches and partial natural re-vegetation (Glatzel et al., 2003; McNeil and Waddington, 2003; Rankin et al., 2018; Strack and Zuback, 2013; Waddington et al., 2010; Waddington et al., 2002). Yearly CO2 fluxes from numerical modelling and eddy covariance measurements at active and post-extracted unrestored sites cover a wide range from 151 to over 400 g C m−2 yr−1 (He et al., 2023; He and Roulet, 2023; Rankin et al., 2018; Waddington et al., 2002).

Canada's current domestic Tier 2 emission factor for CO2 falls within this literature range at 310 g C m−2 yr−1 (ECCC, 2025). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) introduced a three-tier system for emission factors to convey the type of data used, and the accuracy of the estimates. Canada currently uses a Tier 2 approach for greenhouse gas emissions from extracted peatlands, but with data largely collected from post-extraction peatlands. A Tier 3 approach would include the use of process-based models for emission estimates. An improved Tier 2 emission factor, which would include Canadian specific national measurements of CO2 and CH4 emissions from actively extracted sites, would improve the accuracy of our reported emissions. To our knowledge there are no annual estimates of CH4 fluxes from extracted peatlands in Canada. Growing season (May to August) plot scale CH4 chamber measurements are wide ranging, with estimated spanning 18 to 90.2 mg C m−2 d−1 (Clark et al., 2023; Hunter et al., 2024). Studies that can reduce uncertainty in CO2 and CH4 emissions will aid Canada in its accounting of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, and in estimating the C benefit arising from restoration of these sites.

There is also uncertainty regarding the environmental controls on these C gas fluxes in drained peatlands generally. Using the convention of a positive WTD when the water table is below the surface, studies at extracted peatlands have generally reported positive relationships between CO2 fluxes and WTD, due to higher decomposition rates under oxic conditions (He and Roulet, 2023; Rankin et al., 2018; Waddington et al., 2002), which aligns with findings in vegetated drained peatlands (Evans et al., 2021). However, in most of these studies, average WTD was less than 50 cm, while we know that local climate and site management can result in periods with WTD greater than 70 cm at extracted peatlands (Glatzel et al., 2004; Price, 2003). Previous research has observed both strong positive (Rankin et al., 2018) and weak to no effect (Clark et al., 2023) of soil temperature on C fluxes from extracted peatlands, but has not considered how the range in WTD and surface soil moisture content might affect the strength and direction of this relationship. We know that temperature dependence of CO2 production can vary with moisture content (Liu et al., 2024; Swails et al., 2022), yet there is limited research on this in heavily drained peatlands. A better understanding of C dynamics during extraction will provide the industry with better tools to balance C fluxes with harvesting yields.

No study has measured ecosystem scale CO2 and CH4 fluxes from actively extracted peatlands in Canada, and to our knowledge, only one study has been conducted in Europe (Holl et al., 2020). Eddy covariance provides the ability to conduct measurements at the ecosystem scale, capturing both field and drainage ditch dynamics at a higher temporal frequency than chamber measurements. This study measured CO2 and CH4 fluxes using the eddy covariance technique at an actively extracted peatland in both Alberta and Quebec, Canada. The objectives of this study were to (i) assess seasonal and interannual patterns of CO2 fluxes and seasonal patterns of CH4 fluxes; (ii) investigate the effect of soil temperature, and its interaction with WTD, on CO2 and CH4 fluxes; and (iii) investigate whether the positive relationship between CO2 and WTD holds in heavily drained peatland systems.

2.1 Study sites

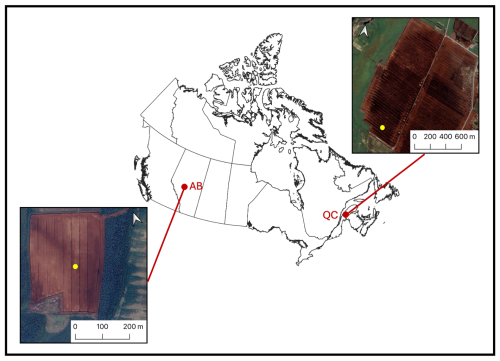

This study was conducted at two actively extracted Canadian peatlands. The site in western Canada (AB) (∼8 ha), located near Drayton Valley, AB (53.222° N, 114.977° W), has been extracted since 2009. The site in eastern Canada (QC site; ∼65 ha), located near Rivière-du-Loup, QC (47.836° N, 69.536° W), has undergone extraction since 2007 (Fig. 1). At each site, prior to extraction, the peat producers removed the surface vegetation and built drainage ditches to partially drain the site and allow harvesting machinery to drive over the site. Perimeter ditches extend around the site, and a series of ∼1 m deep, 0.5 m wide parallel interior drainage ditches, spaced 30 m apart, run the length of the site. The 30 m wide segments of peat between interior drainage ditches are referred to as fields (Waddington et al., 2009). Extraction generally occurs from May and October each year (depending on weather conditions in any given year), with an average extraction duration of 30 to 40 years. Due to extraction activity, the sites remained unvegetated for the duration of this study. Chamber based CO2 and CH4 fluxes were previously measured during the summers of 2019, 2021 and 2022 at AB (Hunter et al., 2024) and 2018, 2019 and 2020 at QC (Clark et al., 2023).

Figure 1Aerial images of AB (left) and QC (right) and their locations in Canada. The position of the eddy covariance towers at each site are indicated with yellow dots. The map was made using ESRI (2025). The vector data shapefile was obtained from Natural Resources Canada (2025). The basemap was obtained from © Google Earth 2024, accessed via QGIS (Version 3.34.15) using XYZ Tiles. Flux footprint models for each site in each year are shown in Fig. S2.

2.2 Instrumentation

The near identical flux tower setup at each site consisted of open path analyzers for and CH4 (LI-7500A and LI-7700, LI-COR, Nebraska, USA), and a sonic anemometer (CSAT-3, Campbell Scientific, Edmonton, Canada). Sensors were mounted on a cross arm at 2.1 m (AB) and 1.8 m (QC) height. The high frequency (10 Hz) and 30 min average data were stored on a USB drive connected to the control unit (LI-7550 AIU, LI-COR, Nebraska, USA). A series of environmental variables were logged half-hourly on a logger (CR3000, Campbell Scientific, Edmonton, Canada) including air temperature and relative humidity (HMP 45C, Vaisala, Finland) and incoming solar radiation (CNR-1, Kipp and Zonen, Netherlands). Due to large data gaps in air temperature and incoming solar radiation at the AB site, we used provincial and national weather station data for the whole study period. Air temperature was obtained from the Tomahawk AGDM weather station located ∼11 km southeast of the AB site (53.43° N, 114.72° W; ACIS, 2023) and incoming solar radiation from the Evansburg 2 AGDM weather station (53.61° N, 115.06° W; ACIS, 2023), located ∼20 km northwest of the AB site. We observed significant regressions between the measured solar radiation data at AB and the Evansburg radiation data (, p<0.0001; R2=0.73; Fig. S1) and between the measured air temperature at AB and Evansburg temperature data (, p<0.0001; R2=0.96; Fig. S1).

Additionally, soil temperature data was measured with Type T thermocouples (Omega Engineering, Stamford, Connecticut, USA) at a depth of 10 cm and logged half-hourly on a data logger (CR1000X, Campbell Scientific, Edmonton, Canada). Water table depth in 2020, 2021 and 2022 at AB and during 2020 and 2022 at QC was measured every 10 s and averaged hourly using pressure readings from Micro-Divers (Van Essen, Waterloo, Canada). These instruments were installed in a 2 m deep PVC well located at the center of a field in a harvesting exclusion zone near each tower (Fig. 1). The measured pressure values were converted to WTDs by subtracting the atmospheric air pressure data measured at the Stoney Plains climate station (53.56° N, 114.11° W; ECCC, 2023b) for AB and from a Micro-Diver hung above the peat surface at QC. A barometric correction was performed at AB to account for the elevation difference between our site and the climate station. Daily precipitation data was obtained from the Tomahawk AGDM station (ECCC, 2023c) and the Rivière-du-Loup Climate Station (47.81° N, 69.55° W; ECCC, 2023a), located ∼3 km northwest of the QC site. A trail camera (Moultrie Products, Alabama, USA) was installed on the AB tower during August and September 2022 to capture the timing of extraction activities (Sect. S1 in the Supplement).

At QC, the integrated top 14 cm VWC was measured using a 20 cm long water content reflectometer (CS 616, Campbell Scientific, Edmonton, Canada) inserted at a 45° angle. A combination of CS 655 and CS 616 probes were inserted horizontally into the peat at a depth of 20 cm at AB. The probes at both sites were logged half-hourly on a data logger (CR1000X, Campbell Scientific, Edmonton, Canada). Periods of insufficient power supply and equipment failure resulted in sporadic VWC measurements.

2.3 Flux processing and quality control

The eddy covariance data was processed using EddyPro software (version 7.0.9, LI-COR, Nebraska) advanced mode with a WPL correction to account for the effect of humidity and air temperature on density (Webb et al., 2007). The CO2 and CH4 data were storage corrected, and then de-spiked (Papale et al., 2006). Fluxes beyond three standard deviations of the mean were marked as outliers and removed. To account for low turbulent conditions, only half-hourly fluxes with the highest possible quality flag were used for this study (Mauder and Foken, 2004). Additionally, due to the potential for incorrect air density calculation, all 30 min CO2 and CH4 fluxes where the corresponding sensible or latent heat flux quality flag (Mauder and Foken, 2004) was at the lowest value were removed. All CH4 fluxes with a signal strength less than 30 % were removed.

To remove periods of insufficient turbulence, we applied a u* threshold of 0.15, 0.14 and 0.18 at AB in 2020, 2021 and 2022, respectively, and 0.17 and 0.19 for the 2020 and 2022 at QC, respectively. This threshold was objectively determined using the REddyProc online processing tool (Wutzler et al., 2018) to identify periods of low turbulence which did not meet the assumptions of the eddy covariance technique (Burba, 2013). Due to the absence of photosynthetic uptake, we applied this correction to both daytime and nighttime fluxes. We applied the same u* threshold to the CH4 data, assuming that insufficient turbulent conditions for CO2 would also be insufficient for CH4 fluxes. A 2D flux footprint at each site in each study year was estimated using the Flux Footprint Prediction (FFP) online tool (Kljun et al., 2015). Based on the FFP, fluxes were excluded from the analyses at AB when their 80 % probability footprint distance was beyond the edge of the extraction site (Fig. S2). Given the larger fetch at QC, no fluxes had to be removed (Fig. S2). The relative proportion of ditches and fields in the 80 % and 90 % probability flux footprints at each site were extracted using QGIS (QGIS Development Team, 2024). The ditches accounted for between 2 % and 5 % of the total footprint area (Table S1).

Incoming solar radiation of 20 W m−2 was used as a cut-off between daytime and nighttime fluxes. For the CO2 and CH4 data, there were no months in our data set that had more than 25 % of the original nighttime half hourly periods, with the majority having less than 15 % (Tables S2, S3, S4). This was likely due to the highly stable atmospheric conditions present overnight. We thus excluded all nighttime data from our analysis due to low data confidence and to not bias our analyses by the lower nighttime sample size. For the daytime CO2 fluxes, we excluded all months that had fewer than 20 % of the potential half hourly periods. Our resulting dataset for CO2 includes data from March to October 2020, March to August 2021 and May to October 2022 at AB, and July to October 2020 and May to October 2022 at QC. Due to instrument damage at QC and COVID travel restrictions, our CH4 dataset extends from May to August 2022 at AB only. For our analysis, we only used daytime data between 09:00 a.m. and 05:30 p.m. local standard time. This was based on the low percent of available data that met our quality standards during the early morning and later evenings compared to the middle of the day. This daytime period is also representative of the times when we were able to make chamber-based C fluxes measurements at these active sites (Clark et al., 2023; Hunter et al., 2024). While the biogeochemical processes responsible for CO2 exchange should be the same during the day and night at this unvegetated site, our estimated fluxes are likely an overestimation of the total CO2 flux due to the exclusion of the cooler nighttime periods.

We observed significant exponential relationships between air temperature and CO2 fluxes at our study sites; however, they had a high degree of scatter and low correlation (Fig. S3). Well established gap-filling methods, such as those employed by REddyProc use moving point windows to gap fill CO2 data based on similar periods of global radiation, air temperature and vapour pressure deficit. These variables are more strongly linked, and have a shorter lag time, with photosynthesis than with heterotrophic respiration and the NEE from our extracted sites (with vegetation having been removed) represents respiration only. Based on the low percentage of original flux data after strict quality control, we did not gap fill our data.

2.4 Calculation of annual carbon budget

We estimated an annual upper limit CO2 and CH4 budget for Canadian extracted peatlands. Given the periods of missing data at each site, and the need for Canada-wide values for national emissions factor reporting, we combined data from both AB and QC, and averaged data across all study years. In the absence of nighttime data, we assumed that average daytime (09:00 a.m. to 05:30 p.m.) monthly March to October fluxes were representative of the whole month. We estimated the missing wintertime (November to February) CO2 fluxes using three methods. The first was to use a daily value equivalent to 15 % of the March to October fluxes rate (Saarnio et al., 2007); the second was to compute 50 % of our average monthly May to October fluxes, and then use that as a monthly fluxes rate for the whole year (He and Roulet, 2023); the third was to use our limited wintertime CO2 measurements. For CH4, we assumed that fluxes for the missing months (October to April) were equivalent to 15 % of the March to October flux rate (Saarnio et al., 2007). To account for the uncertainty in the contribution of our estimates for periods of missing data for the annual CO2 and CH4 budgets, we included an error term representing a 15 % increase or decrease in these estimates. We calculated an annual net ecosystem carbon budget (NECB) using our estimated CO2 and CH4 annual budgets, along with dissolved organic carbon export measurements from 2021 and 2022 at AB (Frei, 2023). This estimate represents emissions occurring at the peat extraction site, and thus does not include emissions relating to the harvested peat and its end use (e.g., Sharma et al., 2025).

2.5 Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed in RStudio (R Core Team, 2021; RStudio Team, 2020). The scatter, line and boxplots were produced using the ggplot2 package (Wickham, 2016). We used QQ plots to visually assess the normality of the C fluxes (Zurr et al., 2009). The CH4 fluxes were shifted by 6.12 mg C m−2 d−1 to remove negative values and then log transformed to meet the assumption of normality for analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Only daytime 09:00 a.m. and 05:30 p.m. local standard time CO2 and CH4 data from March to October was used for the following analysis (see Sect. 2.3).

A two-way ANOVA was performed on a linear model to determine the effect of month and location (factor with five levels combining site and year) on CO2 fluxes. For CH4 fluxes, a one-way ANOVA was performed to determine the effect of month on CH4 fluxes at AB in 2022. The Tukey post hoc test (emmeans package; Lenth et al., 2018) was used when a fixed effect was significant. We averaged the data monthly to assess seasonal trends despite the small fraction of data that passed quality assurances. To create a balanced design and remove the effect of unequal number of fluxes between half hourly periods, these models were run on monthly half hourly averages of CO2 and CH4. Linear regressions were performed to determine the effect of daily averaged soil temperature and VWC on CO2 and CH4 fluxes. We fitted average daily and weekly CO2 fluxes and WTD using a Gaussian model (Riutta et al., 2007),

where WTDopt and WTDtol were fitted parameters representing the optimal WTD for CO2 fluxes, and the deviation from the optimum where CO2 fluxes are 61 % of the maximum, respectively. To understand the parameter uncertainty, we conducted a non-parametric bootstrap analysis with 1000 resamples to determine the 95 % confidence intervals.

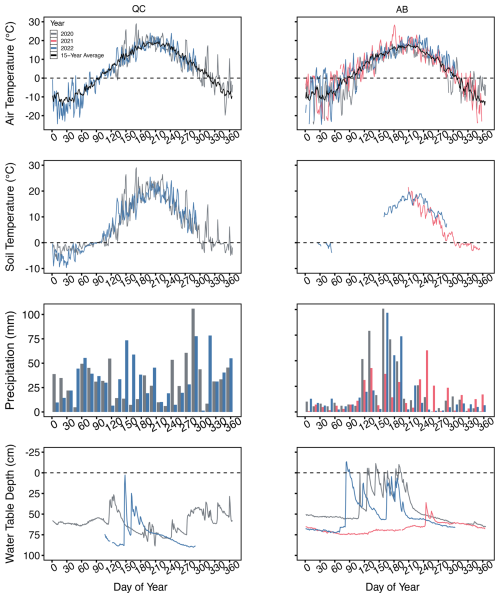

3.1 Environmental conditions

At AB, the 2020 study period (March to October) was wetter (482 mm) than the 15-year average of 377 mm, while the 2021 (341 mm) and 2022 (350 mm) periods were comparable to it (ACIS, 2023). Of note, in 2022, 65 % of the precipitation occurred during June and July, compared to only 27 % in 2021 (Fig. 2). Average air temperature across the study period was cooler in 2020 (7.6 °C), and warmer in 2021 (10.3 °C) and 2022 (9.9 °C) than the 15-year average (9.1 °C) (Fig. 2) (ACIS, 2023). At QC, the 2020 (609 mm) and 2022 (601 mm) study period precipitation totals were similar to the 15-year average (596 mm) (ECCC, 2023a). However, the spread was different, with 2020 being wettest in September and October compared to in March and May in 2022. Similarly, average air temperature was within 0.1 °C of the 15-year average of 9.6 °C (Fig. 2).

Soil temperature followed the seasonal pattern of air temperature (Fig. 2). Temperatures were around 2 °C higher in July onwards in 2022 compared to 2021 at AB, with smaller diurnal and daily temperature fluctuation. At QC, temperatures were similar between years, reaching a monthly average peak of ∼20 °C in July of each year.

Both the average WTD and the degree of water table fluctuation were different among years and sites (Fig. 2). At AB, WTD steadily rose from ∼70 to 60 cm below the surface from April to August in 2021. In contrast, 2020 and 2022 were characterized by large water table fluctuations and WTD of less than 40 cm for most of the study period. At QC, WTD was shallowest in May (2020) and June (2022), though unlike AB, the water table was rarely within the top 30 cm of the peat. In 2022 at the QC site, the water table dropped to greater than 90 cm depth by early fall.

Figure 2Daily mean air temperature (°C), 10 cm depth soil temperature (°C) and WTD (cm) at QC (left) and AB (right) during the study years. Water table depth was measured in the centre of a field (see Fig. 1). A negative value implies that the water table was above the peat surface. The 15-year average (2008 to 2022) air temperature at AB and QC is shown in black. Air temperature at AB was obtained from the Tomahawk AGDM weather station (ACIS, 2023). Precipitation data was obtained from the Tomahawk climate station (for AB; ECCC, 2023c) and the Rivière-du-Loup climate station (for QC; ECCC, 2023a).

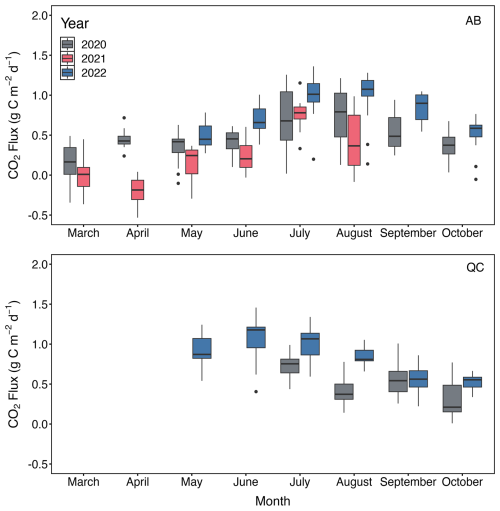

3.2 Carbon dioxide and methane fluxes

Mean monthly daytime (09:00 a.m. to 05:30 p.m. local standard time) CO2 fluxes ranged from −0.19 to 1.0 g C m−2 d−1 at AB and 0.39 to 1.09 g C m−2 d−1 at QC (Fig. 3, Table S5). There was a significant effect of month (, p<0.0001) and location (factor with five levels combining site and year; , p<0.0001), and their interaction (, p<0.0001) on monthly daytime CO2 fluxes. At AB, we observed a pattern of CO2 fluxes increasing during May and June, reaching a peak in July, and then decreasing in September and October (Fig. 3). The effect was largest in 2021 and 2022, with a significant increase in average monthly CO2 fluxes of 0.6 and 0.5 g C m−2 d−1, respectively from May to July (Table S5). Late winter and early spring March and April fluxes were not consistent between years. April 2020 fluxes were comparable to those in June, while there was a small average uptake in 2021 in March (−0.01 g C m−2 d−1) and April (−0.19 g C m−2 d−1). Interannually, May to August fluxes were at least 25 % higher in 2022 compared to 2021, though differences were only significant during the month of August (Fig. 3, Table S5).

We observed similar patterns at QC (Fig. 3). Carbon dioxide fluxes peaked in June and July, in 2020 and 2022, respectively, significantly decreasing by 0.43 and 0.56 g C m−2 d−1 by October in their respective years (Table S5). Of note, August 2020 fluxes were significantly lower than in both July and September (Table S5). Interannually, July and August fluxes were 0.28 and 0.45 g C m−2 d−1 higher in 2022 than 2020, while September and October fluxes were similar between years. When comparing between sites, May and June CO2 fluxes in 2022 at QC were significantly higher than those in the three AB study years. July, August, September and October CO2 fluxes, which were measured at each site over two years, were similar between sites and years, with the highest fluxes generally at QC and AB in 2022 and the lowest average fluxes at AB in 2021.

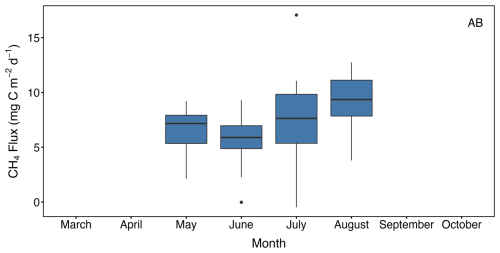

Methane fluxes were only measured for one year at AB (Fig. 4, Table S6). There was a significant effect of month (, p=0.0016) on CH4 fluxes. We observed a seasonal pattern, with average monthly daytime (09:00 a.m. to 05:30 p.m.) fluxes increasing significantly from 6.54 mg C m−2 d−1 in May to 9.13 mg C m−2 d−1 in August.

Figure 3Boxplots of average monthly daytime (09:00 a.m. to 05:30 p.m. local standard time) CO2 fluxes during 2020, 2021 and 2022 at AB (top) and QC (bottom). Measurements from March and April in 2022 at AB, from March, April, May and June at QC in 2020, and from March and April at QC in 2022 are missing due to equipment damage and COVID restrictions. See Table S5 for summary of results from post hoc test performed on linear model looking at the effect of location and month on CO2 fluxes.

Figure 4Boxplots of average monthly daytime (09:00 a.m. to 05:30 p.m. local time) CH4 fluxes during 2022 at AB. Measurements from March, April, September and October are missing due to equipment damage and COVID restrictions. See Table S6 for summary of results from post hoc test performed on linear model looking at effect of month on CH4 fluxes. Methane values displayed on this figure are the raw non-log transformed fluxes.

3.3 Environmental controls of carbon dioxide and methane fluxes

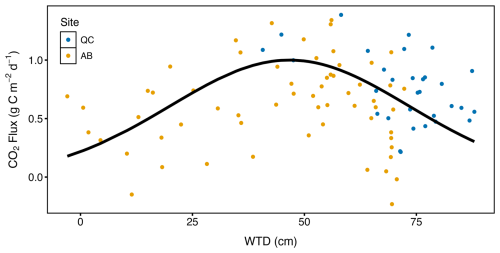

We observed a Gaussian relationship between average weekly WTD and CO2 fluxes across both sites and years (Fig. 5), with fitted WTDopt and WTDtol parameters of 46.7±3.2 and 26.7±2.9 respectively. We observed 95 % confidence intervals of 39.7–52.6 and 21.4–33.1 for the two fitted parameters through a non-parametric bootstrap analysis. Carbon dioxide fluxes peaked at a WTD of ∼47 cm, with a positive relationship when WTDs were less than this threshold, and a negative relationship when WTDs were greater than this threshold. A linear regression between the observed and predicted CO2 values was significant (, p=0.0016), with a correlation of 32 %. A similar gaussian relationship was also observed at the daily time scale (Fig. S5), with a similar significant linear relationship between the observed and predicted values (, p=0.0043). At QC, the average monthly WTD was never less than 50 cm, suggesting that there was always a moisture limitation for decomposition at the site during our measurement periods. There was no significant effect of half-hourly VWC on CO2 emissions (Fig. S4) at AB (, p=0.15). At QC, VWC explained less than 1 % of the variation in CO2 fluxes (, p=0.0001). This may be due to both the limited number of VWC measurements, and the placement of the sensors. It should be noted, however, that the sensors were by necessity in a harvesting exclusion zone that was not subjected to harrowing and harvesting practices, meaning that the measurements were not a true representation of field surface moisture conditions.

Figure 5Scatterplot showing the effect of weekly average WTD on CO2 fluxes at QC and AB. The data has been fitted using a Gaussian model (Eq. 1) resulting in an optimal WTD (WTDopt) of 46.7±3.2 cm.

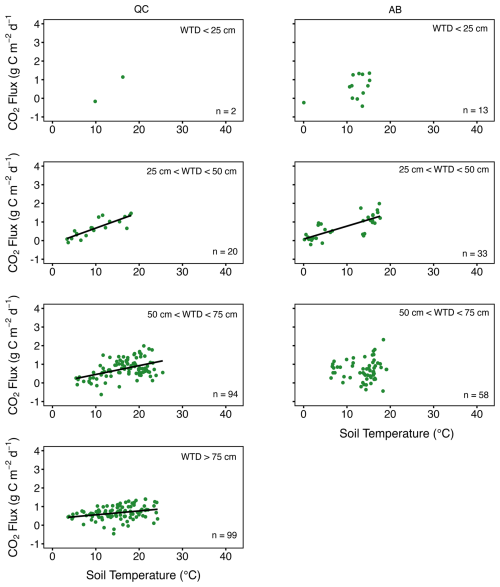

At AB, there was a significant effect of the interaction between 20 cm depth soil temperature and WTD on daily mean CO2 fluxes at AB (, p<0.0001). In contrast, there was a significant interaction between soil temperature at 10 cm depth and WTD at QC (, p<0.0001). Grouping the CO2 data by WTD revealed that the relationship between CO2 and soil temperature varied with WTD (Fig. 6). We categorized WTD as wet periods (WTD <25 cm), moderate periods (50 cm > WTD > 25 cm), dry periods ( cm) and very dry periods (WTD >75 cm). At AB, during dry periods there was no significant effect of soil temperature on CO2 fluxes (Fig. 6, Table S7). In contrast, soil temperature explained 59 % of the variance in CO2 fluxes during moderate WTD periods. There was no significant effect during wet periods, likely due to the very small sample size (Fig. 6, Table S7). At QC, there was a significant positive effect of soil temperature on CO2 fluxes at a daily time scale for all WTD levels, though the relationships were strongest, and had the steepest slope, during wetter periods. We observed no effect of harrowing or harvesting on ecosystem scale CO2 fluxes (Sect. S1, Fig. S6).

There was a significant positive effect of soil temperature at 20 cm depth on daily CH4 fluxes at AB (, p<0.0001), explaining 11 % of the variation (Fig. S7). Due to the small number of data points, and the narrow range of temperatures recorded when the WTD was less than 50 cm, we did not divide the data by WTD level.

Figure 6Scatterplots showing the effect of 10 cm depth (QC) and 20 cm depth (AB) soil temperature on daily daytime (09:00 a.m. to 05:30 p.m.) CO2 fluxes at QC (left column) and AB (right column) across the study years. The CO2 data has been divided by WTD, as wet period (WTD <25 cm), moderate period (50 cm > WTD > 25 cm), dry period (75 cm > WTD > 50 cm) and very dry period (WTD >75 cm). All linear regressions were significant (Table S6). The sample size (n) is indicated on the figures.

3.4 Annual net ecosystem carbon budget

Using our March to October monthly average fluxes across both sites, we calculated three annual CO2 budgets for extracted peatlands in Canada using different approaches to estimate missing wintertime (November to February) data (see Sect. 2.4). Assuming that wintertime fluxes were 15 % of March to October fluxes, we calculated annual CO2 budget of 129±2 g C m−2 yr−1. Using our limited wintertime data, we calculated average daytime (09:00 a.m. to 05:30 p.m.) monthly fluxes of 0.56, 0.40, 0.50, and 0.42 g C m−2 d−1 for November, December, January and February, respectively at AB. These are comparable to the 0.5 g C m−2 d−1 often estimated for non-growing season CO2 fluxes (Webster et al., 2018). This then resulted in an annual CO2 budget of 174±9 g C m−2 yr−1. The error term in these two estimates accounts for a 15 % increase or decrease in non-growing season estimates. Finally, by assuming that monthly fluxes for the whole year were 50 % of average March to October fluxes (He and Roulet, 2023), we calculated an annual CO2 budget of 112 g C m−2 yr−1. We calculated an annual CH4 budget of 1.1±0.4 g C m−2 yr−1, assuming that the missing September to April CH4 fluxes were 15 % of our measured May to August fluxes. Assuming a lower and upper DOC export limit in a dry and wet year of 2 and 10 g C m−2 yr−1, respectively (Frei, 2023), the annual NECB likely ranges from fluxes of 115 to 185 g C m−2 yr−1.

Across both study sites, we observed important controls on seasonal and interannual C fluxes that must be considered when estimating the annual greenhouse gas budgets of extracted peatlands. These include the unimodal relationship between CO2 and WTD, and the interacting effects of temperature and WTD on CO2 fluxes.

4.1 Carbon dioxide fluxes

We measured comparable ecosystem-scale daytime fluxes at QC and AB. In contrast, previous multi-year chamber studies from our study sites reported that AB (Hunter et al., 2024) had around double the site-integrated ditch and field CO2 fluxes as QC (Clark et al., 2023). The Clark et al. (2023) average summertime fluxes of 0.76 and 2.56 g C m−2 d−1 from the fields and ditches, with a field to ditch ratio of 30:1, results in sector fluxes of 0.82 g C m−2 d−1. This is in line with our average fluxes at QC. Hunter et al. (2024), using the same field to ditch ratio, calculated integrated summer June to August fluxes of 1.47 g C m−2 d−1 at AB, which is just over double our eddy covariance estimated average fluxes of 0.66 g C m−2 d−1 during that same period. This may be due to unequal relative contribution of ditch and field fluxes to total sitewide fluxes in the two studies, since Hunter et al. (2024) found that ditch CO2 fluxes were around double the field fluxes.

4.1.1 Decreased carbon dioxide fluxes during periods with deep water tables

The persistent drainage at extracted sites means that surface VWC may be below the optimum for aerobic decomposition for large portions of the year. Our interannual and seasonal patterns suggest a decrease in CO2 fluxes during periods with deep water tables. At AB, May, June and August average fluxes were at least double (at least 0.2 g C m−2 d−1 higher) in 2020 and 2022 compared to 2021, which coincided with 20 to 50 cm deeper water tables in 2021 compared to the other two years. Our soil temperature data suggests that the surface temperature varied by only a few degrees between these years. This is consistent with findings by Hunter et al. (2024) who observed significantly lower chamber fluxes in 2021 compared to 2022 at AB. Seasonally, in 2022 at QC, we observed some of the highest fluxes when WTDs were their shallowest, around 30 cm (June and May). This was despite the peat being 10 to 20 °C cooler than later in the summer. Thus, both AB and QC results show higher CO2 with wetter peat conditions (water tables closer to the surface). These results seemingly contrast with other studies and data compilations at extracted peatlands, which have observed reduced fluxes during wet periods (He and Roulet, 2023; Holl et al., 2020; Rankin et al., 2018). This reported reduction in fluxes can be considerable, with CO2 fluxes during a wet summer being 24 % of the dry summer fluxes (Waddington et al., 2002). The exception is a study in Finland that measured over double the fluxes in a wet year compared to a dry year (Shurpali et al., 2008). Previous studies in drained vegetated peatlands have also generally observed higher fluxes during dry periods (Evans et al., 2021; Nielsen et al., 2023; Salm et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2016), though one study in a heavily drained peatland for forestry found a positive relationship with CO2 fluxes when WTDs were greater than 70 cm (Mäkiranta et al., 2009).

We offer four possible explanations for our observed reduced emissions during dry periods. The first is that the water table–CO2 relationship is likely unimodal, as was seen in our study (Fig. 5) where peak fluxes occurred at a WTD of 47 cm. This has been observed in other peatland studies, with the optimal CO2 production occurring under hydrologic conditions that maximize aerobic conditions while also maintaining sufficient surface moisture conditions for substrate diffusion (Byun et al., 2021; Ojanen and Minkkinen, 2019). Most of the previous studies have had water tables within the top 50 cm of the peat profile, while our water tables were deeper than 50 cm for 68 % and 84 % of the days during the AB (March to October) and QC (May to October) study periods, respectively. When water tables varied within the top ∼50 cm of the peat, as is the case for many previous studies in drained peatlands (e.g., Evans et al., 2021), we observed the expected positive relationship. Additional studies in heavily drained systems will aid in better determining this WTD threshold for optimum decomposition. Secondly, WTD measurements in heavily drained peatlands may provide misleading information about redox conditions in the near surface peat. Peatlands with high water retention can maintain high surface moisture contents despite deep water tables (Lai, 2022; Price, 2003). Additionally, wetting fronts may never reach the water table, resulting in increases in surface moisture content, but no measurable change in WTD (Waddington et al., 2002). Therefore, continuous measurements of surface VWC should be conducted in future studies to better assess how changes in WTD relate to surface moisture conditions. Thirdly, this study could not assess whether there was a hysteretic relationship between soil moisture and WTD, and how the frequent water table fluctuations in May and June may have contributed to the observed CO2 fluxes (Rezanezhad et al., 2014). Fourthly, there has been limited research on the shifts in the microbial community following long term drainage of extracted sites (Basiliko et al., 2007; Bieniada et al., 2023; Croft et al., 2001), and how these changes will affect CO2-water table relationships.

This work therefore shows that the assumption of a positive relationship between CO2 fluxes and WTD, which has been observed in many studies with a drainage depth of less than 50 cm, may not hold in heavily drained systems. Our work suggests that maintaining deep water tables prior to restoration could be a management strategy to reduce CO2 fluxes, though more work should be done to generalize this finding to other sites. It must be noted that the removal of vegetation during peat extraction shifts these sites from net sinks to net sources of CO2 during active extraction, regardless of the degree of drainage. Given the management (harrowing and harvesting) activities at these sites, the surface layer (top 5 cm) is expected to undergo hourly to multi-day changes in moisture content and bulk density (Lai, 2022; O'Kane, 1992). The effects of management on C gas production and transport have not been adequately studied; however, we did not observe noticeable effects of these activities on CO2 fluxes (Fig. S5).

4.1.2 Water table depth affects the dependence of carbon dioxide fluxes on soil temperature

Although half-hourly soil temperature on its own does not explain much of the variance in CO2 fluxes at our sites, when categorized by WTD and analysed at a daily timestep, a stronger trend emerges likely due to control of moisture on decomposition and decomposition occurring over a range of depth in the peat profile. Based on thermodynamics of peat decomposition, studies generally observe higher aerobic CO2 production with increasing peat temperature (Byun et al., 2021; Limpens et al., 2008). Our seasonal patterns highlight the importance of soil temperature as a control on CO2 fluxes at the monthly time scale. However, our regressions yielded weak positive relationships with a high degree of scatter and low explanatory power, accounting for only 16 % of the variance in CO2 fluxes. Soil temperature had a moderate positive effect on chamber-based measurements at AB (Hunter et al., 2024), and this mismatch could be due to measurement methods. In Hunter et al. (2024), temperature measurements were made directly adjacent to the C flux measurements, while our study made temperature measurements in a harvesting exclusion zone adjacent to the eddy covariance tower. It is possible that our 10 cm depth soil temperature was not representative of the temperature of peat directly below a harrowed layer in the fields. This could also explain why soil temperature at 20 cm depth was a stronger predictor than at 10 cm depth at AB, as it was less likely to be affected by harrowing and harvesting practices. Other peatland studies have also observed a stronger CO2−soil temperature relationship at depth (e.g., Heffernan et al., 2024).

When CO2 data was grouped by water table position, we found that there was a stronger effect of soil temperature when the water table was within the top 50 cm of the peat. The decreasing importance of soil temperature during dry periods is likely due to the increasing importance of surface soil moisture for decomposition (see Sect. 4.1.1). In addition to measurement method, this complex interaction between water table and temperature control on CO2 fluxes could help explain the mismatch in the importance of soil temperature within the peat extraction literature. Studies in extracted peatlands (both active and unrestored) using chamber and eddy covariance techniques have observed strong positive effects (He et al., 2023; Rankin et al., 2018; Shurpali et al., 2008), moderate (Hunter et al., 2024; Salm et al., 2012; Waddington et al., 2002) and weak to no effect (Clark et al., 2023; Sundh et al., 2000) of soil temperature on CO2 fluxes. These studies generally did not measure hydrologic conditions, or report VWC measurements, making it hard to compare among them. However, the strong effect observed by Rankin et al. (2018) was at a post-extraction, unrestored peatland with a water table that was within the top 50 cm of the peat until mid-August, and we might thus expect a stronger temperature dependence. In our data set, while the water table was within the top 50 cm for a large portion of one of our study years (2022) at AB, most of our data is from periods with deeper water tables.

This importance of hydrologic conditions on the effect of soil temperature on CO2 fluxes has not been well-explored, with the presence of vegetation at many sites making it difficult to disentangle the impact of water table-soil temperature interactions on autotrophic (plant) respiration versus heterotrophic respiration. While the majority of recent peatland studies on soil respiration have found higher temperature dependence in drier conditions (Li et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2024; Swails et al., 2022), a few studies in drained extracted peatlands observed similar results to ours (Shurpali et al., 2008; Waddington et al., 2002). Additionally, in soils drained for forestry and agriculture, multiple studies have observed increased dependence of heterotrophic CO2 fluxes on soil temperature under wet periods (Balogh et al., 2011; Scott-Denton et al., 2006). We explored how CO2−temperature relationship varied across binned WTDs (Sect. 3.3), but we acknowledge that one cannot know the direction to interpret a 2-way interaction (Spake et al., 2023). Analysis of the CO2−WTD relationship across a range of soil temperature also suggested that CO2 is controlled by the co-occurrence of warm and dry conditions (Fig. S8, Table S8). The VWC that constitutes “dry” conditions varies among studies, and therefore, comprehensive measurements of surface VWC at heavily drained sites would allow us to better compare our findings to the wider literature. Nevertheless, our findings will have implications for modelling work at drained peatlands. Many processed based models rely on CO2–temperature relationships to estimate emissions arising from respiration in peatlands (e.g., Bona et al., 2020; He et al., 2023). Our results indicate the importance of considering the interacting effects of soil moisture and temperature on respiration during dry periods.

4.1.3 Soil temperature relationships underestimate March and April carbon dioxide fluxes

March and April are associated with the start of peat thawing and snowmelt. April fluxes were comparable to summer values at AB in 2020 (Fig. 3), demonstrating the importance of capturing spring thaw fluxes in our annual C budgets. Episodic pulses of CO2 in the late winter and early spring have been measured at some drained peatlands (Rankin et al., 2018), but not others (Holl et al., 2020). While we lack soil temperature data in those months, average air temperatures were just above freezing, compared to around 20 °C in July, showing that temperature relationships alone cannot explain CO2 fluxes during this period. Possible mechanisms include the presence of ice lenses in the frozen soil and snow layer that trap produced CO2 during the winter, leading to the release of this built-up CO2 when the soil thaws (Raz-Yaseef et al., 2017). Freeze-thaw cycles have also been shown to alter respiration rates through changes in microbial community structure and enzyme activity (Matzner and Borken, 2008; Wang et al., 2014). Understanding both the magnitude, and the underlying processes involved with these springtime CO2 fluxes will be important as they can contribute a significant portion to the yearly net C balance and are often not captured in northern peatland measurements. Modelling studies that use CO2–temperature relationships may underestimate CO2 fluxes during this period. However, we also observed slightly negative average CO2 fluxes in March and April 2021 at AB, when there should have been no photosynthetic uptake of CO2 by vegetation. These negative fluxes remained after extensive data processing and quality assurance steps, and were thus left in to avoid biasing the data. As our average fluxes are expected to be close to zero during this period, we would expect both positive and negative values around the mean due to noise. Recent studies also suggest that microbial photosynthesis could be responsible for this observed CO2 uptake (Hamard et al., 2021). These springtime fluxes should therefore be interpreted with caution.

4.2 Extracted sites are small sources of methane

Our study suggests that CH4 fluxes are considerably lower at active peat extraction sites than in natural peatlands, suggesting that these sites are small sources of CH4. Our measured mean May to August CH4 fluxes of 7.22 mg C m−2 d−1 (median of 7.51 mg C m−2 d−1) is considerably lower than the growing season 29.9 to 72.7 mg C m−2 d−1 reported for natural boreal bogs in Canada (Turetsky et al., 2014; Webster et al., 2018). Plot scale average and median, in brackets, chamber fluxes at AB in 2022 were 3.1 (0.06) and 2580 (53) mg C m−2 d−1 from the fields and ditches, respectively (Hunter et al., 2024). Assuming the fields consist of around 97 % of the total site area, as seen in our eddy covariance tower footprints, that would result in a site integrated chamber flux (combined field and ditch fluxes) of 80 and 1.6 mg C m−2 d−1, by using the average and median CH4 fluxes, respectively. Given the errors associated with each method, a mismatch between chamber fluxes and ecosystem scale fluxes is not uncommon (Peltola et al., 2015; Riederer et al., 2014). Despite direct chamber measurements indicating that ditches can emit strongly (Clark et al., 2023; Hunter et al., 2024), the CH4 fluxes from extracted peatlands are likely lower than from natural peatlands, and only make up a small portion of the total site NECB (see Sect. 4.3).

The CH4 fluxes at AB in 2022 followed the expected seasonal pattern, with fluxes increasing over the summer following seasonal temperature patterns, as has been observed in natural peatlands (Abdalla et al., 2016). To our knowledge there are no reported March and April CH4 fluxes from actively extracted, or post extraction unrestored, peatlands in Canada. In natural peatlands, ebullition associated with spring thaw can be significant, with some studies reporting larger values than the annual diffusive CH4 fluxes from a site (D'Acunha et al., 2019).

Water table depth and soil temperature were not strong predictors of CH4 fluxes, likely due to a combination of the unique site hydrology, and the overall low CH4 fluxes. The absence of vegetation at our sites means that diffusion, and the associated oxidation of CH4 to CO2 in the oxic peat layer, will be the primary transport pathway of CH4 (Lai, 2009). While peatland studies have usually observed a negative relationship between WTD and CH4 fluxes (Abdalla et al., 2016; Dean et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2016), we did not find a significant effect. This is likely due to the deep water table at the AB site. Couwenberg et al. (2011) found that peatland CH4 fluxes were near zero for WTDs greater than 20 cm, making it hard to detect a WTD effect. The large water table fluctuations at the sites combined with the known long lag time between the establishment of anoxic conditions and the start of CH4 production could also make it difficult to isolate the effect of WTD on CH4 fluxes (Blodau et al., 2004). Finally, the high specific yield of extracted peatlands (Price, 2003) can also support the presence of anaerobic pockets for CH4 production in the surface peat, even during periods of deep water tables (Bieniada and Strack, 2021).

We observed a weak effect of soil temperature on CH4, as has been seen in other extracted sites (Clark et al., 2023; Sundh et al., 2000). In natural peatlands, the importance of soil temperature is complex and varies with season, hydrologic conditions, and vegetation type (Chang et al., 2021; Turetsky et al., 2014). Given the observed WTDs, the majority of CH4 was likely produced below the soil temperature sampling depth, or in the drainage ditches, where we did not measure soil temperature. Future measurements from dry and wet years will aid in understanding CH4 dynamics from extracted peatlands and support management plans that balance harvesting yields with CO2 and CH4 fluxes.

4.3 Implications for annual NECB and emission factors

To date, estimates of CO2 fluxes from extracted peatlands in Canada are wide ranging. A modelling study based at QC reported fluxes of 151–168 g C m−2 yr−1 from the fields (He et al., 2023). At post-extracted unrestored peatlands, Rankin et al. (2018), using eddy covariance, reported an annual CO2 budget of 173 to 259 g C m−2 yr−1, while Waddington et al. (2002) modelled (using chamber data to validate) fluxes of 363 to 399 g C m−2 during a dry year, and 88 to 112 g C m−2 during a wet year. Some vegetation had naturally regenerated since the end of extraction at Rankin et al. (2018)'s site, and so their value likely includes some photosynthetic uptake of CO2. Our calculated annual CO2 budget range of 112 to 174 g C m−2 yr−1 is considerably lower than the current Tier 2 fluxes factor value of 310 g C m−2 yr−1 that Canada is using (ECCC, 2025). A recent study (He and Roulet, 2023), using model simulations run with 27 years of climate data, suggested a revised Tier 3 emission factor value of 139 g C m−2 yr−1 (1.4 t C ha−1 yr−1) for a standard extraction site in Eastern Canada. Our data is more in line with this proposed Tier 3 emission factor compared to the higher Tier 2 value. This study, along with other recent work by Clark et al. (2023), He et al. (2023), He and Roulet (2023) and Sharma et al. (2025) can support Canada updating their emission factor value.

Our findings suggest that the CO2 fluxes make up the bulk of the 115 to 185 g C m−2 yr−1 NECB of these extracted peatlands. Assuming a global warming potential for CH4 over a 100-year time period that is 28 times that of CO2 (IPCC, 2013), CH4 fluxes are equal to 41 g CO2 m−2 yr−1. Methane fluxes are thus at most 9 % of the total radiative balance of CO2 and CH4 fluxes from these sites, not including downstream gaseous loss. Export of C as DOC is likely a small component of the C budget, with previous research finding DOC export at AB was only <2 g C m−2 yr−1 during 2021 (dry year) and <10 g C m−2 yr−1 in 2022 (wet year) (Frei, 2023). Despite the small contribution of CH4 to sitewide fluxes, management actions to reduce CH4 fluxes may be the easiest to implement to achieve greenhouse gas fluxes reductions from actively extracted sites. Given the at least 7 times higher CH4 fluxes from ditches compared to fields (Clark et al., 2023; Hunter et al., 2024), increasing the drainage ditch spacing (and thus reducing the proportional area of ditches) could substantially reduce CH4 fluxes.

Our study is the first to measure ecosystem scale CO2 and CH4 fluxes from actively extracted peatlands in Canada. Interannually, CO2 fluxes varied by as much as 0.5 g C m−2 d−1, and seasonal and interannual patterns were largely driven by WTD differences. Our observed unimodal CO2–WTD relationship suggests that surface moisture conditions at actively extracted peatlands can be below optimal levels for decomposition for large portions of the active extraction season (May to October). The limited previous studies of heterotrophic respiration in drained peatlands have generally been based at sites with shallower water tables than our WTD optimum. Additional measurements at deeply drained sites will allow us to better assess this non-linear mechanism to predict the impact of anthropogenic and climate induced drainage on C cycling in peatlands. Our results also suggest an interaction between soil temperature and WTD, where surface soil temperature has only a weak effect on CO2 and CH4 fluxes under deep (>50 cm below surface) water tables. This means that process-based modelling studies that use C-temperature relationships alone have the potential to overestimate fluxes during drier years in drained unvegetated peatlands. Water table depths at extracted sites are controlled by both local weather, and site management, including the spacing and the depth of the drainage ditches. Understanding how C fluxes vary with fluctuations in WTD will help inform site management plans, allowing companies to balance C fluxes with harvesting yields. At AB, CH4 fluxes were less than a tenth of the fluxes reported for natural boreal bogs, suggesting that actively extracted peatland sites are a negligible source of CH4. However, more work will be needed to understand how well ditch CH4 fluxes are captured by eddy covariance towers. We were unable to quantify nighttime and wintertime CO2 and CH4 fluxes, leading to a large range of estimated yearly fluxes. The current Tier 2 emission factors for CO2 fluxes from Canadian extracted peatlands are well above our estimated 112 to 174 g C m−2 yr−1, suggesting that they may not be appropriate for peat extraction sites in Canada.

The processed CO2 and CH4 fluxes, along with all environmental and meteorological measurements, are available at the Borealis: The Canadian Dataverse Repository with a CC_BY 4.0 licence agreement via https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/EN34AD (Hunter, 2025).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-23-793-2026-supplement.

MLH contributed to conceptualization, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, visualization and original manuscript preparation. IBS and MS contributed to funding acquisition, conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, supervision, and reviewing and editing of the manuscript. PM and SK contributed to formal analysis and reviewing and editing of the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We want to thank everyone who contributed to data collection and eddy covariance tower maintenance, including Rebecca Frei, David Olefeldt, Lorna Harris, Alice Watts, Steffy Velosa, Nicolas Perciballi. Anna Laine-Petäjäkangas, Tonya Delsontro, and Jonathan Price served on MLH's PhD committee and provided comments on the manuscript. We also acknowledge that this research took place on Treaty Six Territory, and the traditional territories of the Ĩyãhé Nakón mąkóce, Tsuut'ina, Michif Piyii (Métis) and Cree First Nations. We thank the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments on this manuscript.

This research was funded through an NSERC Collaborative Research and Development Grant with the support of the Canadian Sphagnum Peat Moss Association (CSPMA) and its members. Miranda L. Hunter was funded partially through NSERC CGS-D and OGS scholarships.

This paper was edited by Ivonne Trebs and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Abdalla, M., Hastings, A., Truu, J., Espenberg, M., Mander, U., and Smith, P.: Emissions of methane from northern peatlands: a review of management impacts and implications for future management options, Ecological Evolution, 6, 7080–7102, https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.2469, 2016.

ACIS: Current and historical Alberta weather station data [data set], https://acis.alberta.ca/acis/weather-data-viewer.jsp (last access: 10 December 2023), 2023.

Balogh, J., Pintér, K., Fóti, S., Cserhalmi, D., Papp, M., and Nagy, Z.: Dependence of soil respiration on soil moisture, clay content, soil organic matter, and CO2 uptake in dry grasslands, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 43, 1006–1013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.01.017, 2011.

Basiliko, N., Blodau, C., Roehm, C., Bengtson, P., and Moore, T. R.: Regulation of Decomposition and Methane Dynamics across Natural, Commercially Mined, and Restored Northern Peatlands, Ecosystems, 10, 1148–1165, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-007-9083-2, 2007.

Bieniada, A. and Strack, M.: Steady and ebullitive methane fluxes from active, restored and unrestored horticultural peatlands, Ecological Engineering, 169, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2021.106324, 2021

Bieniada, A., Hug, L. A., Parsons, C. T., and Strack, M.: Methane Cycling Microbial Community Characteristics: Comparing Natural, Actively Extracted, Restored and Unrestored Boreal Peatlands, Wetlands, 43, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-023-01726-y, 2023.

Blodau, C., Basiliko, N., and Moore, T. R.: Carbon turnover in peatland mesocosms exposed to different water table levels, Biogeochemistry, 67, 331–351, https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BIOG.0000015788.30164.e2, 2004.

Bona, K. A., Shaw, C., Thompson, D. K., Hararuk, O., Webster, K., Zhang, G., Voicu, M., and Kurz, W. A.: The Canadian model for peatlands (CaMP): A peatland carbon model for national greenhouse gas reporting, Ecological Modelling, 431, e109164, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2020.109164, 2020.

Burba, G.: Eddy Covariance Method for Scientific, Industrial, Agricultural and Regulatory Applications: A Field Book on Measuring Ecosystem Gas Exchange and Areal Emission Rates, Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, USA, https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4247.8561, 2013.

Byun, E., Rezanezhad, F., Fairbairn, L., Slowinski, S., Basiliko, N., Price, J. S., Quinton, W. L., Roy-Leveillee, P., Webster, K., and Van Cappellen, P.: Temperature, moisture and freeze-thaw controls on CO2 production in soil incubations from northern peatlands, Sci. Rep., 11, 23219, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02606-3, 2021.

Chang, K. Y., Riley, W. J., Knox, S. H., Jackson, R. B., McNicol, G., Poulter, B., Aurela, M., Baldocchi, D., Bansal, S., Bohrer, G., Campbell, D. I., Cescatti, A., Chu, H., Delwiche, K. B., Desai, A. R., Euskirchen, E., Friborg, T., Goeckede, M., Helbig, M., Hemes, K. S., Hirano, T., Iwata, H., Kang, M., Keenan, T., Krauss, K. W., Lohila, A., Mammarella, I., Mitra, B., Miyata, A., Nilsson, M. B., Noormets, A., Oechel, W. C., Papale, D., Peichl, M., Reba, M. L., Rinne, J., Runkle, B. R. K., Ryu, Y., Sachs, T., Schäfer, K. V. R., Schmid, H. P., Schurpali, N., Sonnentag, O., Tang, A. C. I., Torn, M. S., Trotta, C., Tuittila, E-S., Ueyama, M., Vargas, R., Vesala, T., Windham-Myers, L., Zhang, Z., and Zona, D.: Substantial hysteresis in emergent temperature sensitivity of global wetland CH4 emissions, Nat. Com- mun., 12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22452-1, 2021.

Clark, L., Strachan, I. B., Strack, M., Roulet, N. T., Knorr, K.-H., and Teickner, H.: Duration of extraction determines CO2 and CH4 emissions from an actively extracted peatland in eastern Quebec, Canada, Biogeosciences, 20, 737–751, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-20-737-2023, 2023.

Cleary, J., Roulet, N. T., and Moore, T. R.: Greenhouse gas emissions from Canadian peat extraction, 19990-2000: a life-cycle analysis, Ambio, 34, 456–461, https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447-34.6.456, 2005.

Couwenberg, J., Thiele, A., Tanneberger, F., Augustin, J., Bärisch, S., Dubovik, D., Liashchynskaya, N., Michaelis, D., Minke, M., Skuratovich, A., and Joosten, H.: Assessing greenhouse gas emissions from peatlands using vegetation as a proxy, Hydrobiologia, 674, 67–89, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-011-0729-x, 2011.

Croft, M., Rochefort, L., and Beauchamp, C. J.: Vacuum-extractionof peatlands disturbs bacterial population and micorbial biomass carbon, Applied Soil Ecology, 18, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-1393(01)00154-8, 2001.

D'Acunha, B., Morillas, L., Black, T. A., Christen, A., and Johnson, M. S.: Net Ecosystem Carbon Balance of a Peat Bog Undergoing Restoration: Integrating CO2 and CH4 Fluxes From Eddy Covariance and Aquatic Evasion With DOC Drainage Fluxes, Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 124, 884-901, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019jg005123, 2019.

Dean, J. F., Middelburg, J. J., Röckmann, T., Aerts, R., Blauw, L. G., Egger, M., Jetten, M. S. M., de Jong, A. E. E., Meisel, O. H., Rasigraf, O., Slomp, C. P., in't Zandt, M. H., and Dolman, A. J.: Methane Feedbacks to the Global Climate System in a Warmer World, Reviews of Geophysics, 56, 207–250, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017rg000559, 2018.

ECCC: Historical climate data: Rivière-du-Loup, https://climate.weather.gc.ca/historical_data/search_historic_data_e.html (last access: 10 December 2024), 2023a.

ECCC: Historical climate data: Stoney Plains [data set], https://climate.weather.gc.ca/historical_data/search_historic_data_e.html (last access: 10 December 2024), 2023b.

ECCC: Historical climate data: Tomahawk [data set], https://climate.weather.gc.ca/historical_data/search_historic_data_e.html (last access: 10 December 2024), 2023c.

ECCC: National Inventory Report, Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa, Canada, http://publications.gc.ca/pub?id=9.506002andsl=0 (last access: 10 December 2024), 2025.

ESRI: World Imagery [data set], https://services.arcgisonline.com/ArcGIS/rest/services/World_Imagery/MapServer (last access: 1 September 2025), 2025.

Evans, C. D., Peacock, M., Baird, A. J., Artz, R. R. E., Burden, A., Callaghan, N., Chapman, P. J., Cooper, H. M., Coyle, M., Craig, E., Cumming, A., Dixon, S., Gauci, V., Grayson, R. P., Helfter, C., Heppell, C. M., Holden, J., Jones, D. L., Kaduk, J., Levy, P., Matthews, R., McNamara, N. P., Misselbrook, T., Oakley, S., Page, S. E., Rayment, M., Ridley, L. M., Stanley, K. M., Williamson, J. L., Worrall, F., and Morrison, R.: Overriding water table control on man- aged peatland greenhouse gas emissions, Nature, 593, 548–552, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03523-1, 2021.

Frei, R. J.: Consequences of peatland disturbance for dissolved organic matter and nutrient transport and fate in northern catchments, Ph.D. thesis, University of Alberta, https://doi.org/10.7939/r3-wy23-r730, 2023.

Glatzel, S., Kalbitz, K., Dalva, M., and Moore, T.: Dissolved organic matter properties and their relationship to carbon dioxide efflux from restored peat bogs, Geoderma, 113, 397–411, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-7061(02)00372-5, 2003.

Glatzel, S., Basiliko, N., and Moore, T.: Carbon dioxide and methane production potentials of peats from natural, harvested and restored sites, eastern Québec, Canada, Wetlands, 24, 261–267, https://doi.org/10.1672/0277-5212(2004)024[0261:Cdampp]2.0.Co;2, 2004.

Greenwood, M. J.: The effects of restoration on CO2 exchange in a cutover peatland, M.Sc. thesis, McMaster University, http://hdl.handle.net/11375/21160, 2005.

Hamard, S., Céréghino, R., Barret, M., Sytiuk, A., Lara, E., Dorrepaal, E., Kardol, P., Küttim, M., Lamentowicz, M., Leflaive, J., Le Roux, G., Tuittila, E.-S., and Jassey, V. E. J.: Contribution of microbial photosynthesis to peatland carbon uptake along a latitudinal gradient, Journal of Ecology, 109, 3424–3441, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.13732, 2021.

Harris, L. I., Roulet, N. T., and Moore, T. R.: Drainage reduces the resilience of a boreal peatland, Environmental Research Communications, 2, https://doi.org/10.1088/2515-7620/ab9895, 2020.

He, H. and Roulet, N. T.: Improved estimates of carbon dioxide emissions from drained peatlands support a reduction in emission factor, Communications Earth and Environment, 4, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-01091-y, 2023.

He, H., Clark, L., Lai, O. Y., Kendall, R., Strachan, I., and Roulet, N. T.: Simulating Soil Atmosphere Exchanges and CO2 Fluxes for an Ongoing Peat Extraction Site, Ecosystems, 26, 1335–1348, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-023-00836-2, 2023.

Heffernan, L., Estop-Aragonés, C., Kuhn, M. A., Holger-Knorr, K., and Olefeldt, D.: Changing climatic controls on the greenhouse gas balance of thermokarst bogs during succession after permafrost thaw, Global Change Biology, 30, e17388, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.17388, 2024.

Holl, D., Pfeiffer, E.-M., and Kutzbach, L.: Comparison of eddy covariance CO2 and CH4 fluxes from mined and recently rewetted sections in a northwestern German cutover bog, Biogeosciences, 17, 2853–2874, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-2853-2020, 2020.

Hugelius, G., Loisel, J., Chadburn, S., Jackson, R. B., Jones, M., MacDonald, G., Marushchak, M., Olefeldt, D., Packalen, M., Siewert, M. B., Treat, C., Turetsky, M., Voigt, C., and Yu, Z.: Large stocks of peatland carbon and nitrogen are vulnerable to permafrost thaw, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 117, 20438–20446, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1916387117, 2020.

Hunter, M.: Ecosystem scale carbon dioxide and methane emissions from extracted peatlands in Alberta and Quebec, Canada, Borealis [data set], https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/EN34AD, 2025.

Hunter, M. L., Frei, R. J., Strachan, I. B., and Strack, M.: Environmental and Management Drivers of Carbon Dioxide and Methane Emissions From Actively-Extracted Peatlands in Alberta, Canada, Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 129, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023jg007738, 2024.

IPCC: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Stocker, T. F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S. K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., and Midgley, P. M., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1535 pp., https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324, 2013.

Kendall, R.: Microbial and substrate decomposition factors in Canadian commercially extracted peatlands, M.Sc. thesis, McGill University, https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/gh93h442s (last access: 1 September 2025), 2021.

Kennedy, G. W. and Price, J. S.: A conceptual model of volume-change controls on the hydrology of cutover peats, Journal of Hydrology, 302, 13–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2004.06.024, 2005.

Kitson, E. and Bell, N. G. A.: The Response of Microbial Communities to Peatland Drainage and Rewetting: A Review, Front. Microbiol., 11, 582812, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.582812, 2020.

Kljun, N., Calanca, P., Rotach, M. W., and Schmid, H. P.: A simple two-dimensional parameterisation for Flux Footprint Prediction (FFP), Geosci. Model Dev., 8, 3695–3713, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-8-3695-2015, 2015.

Lai, D. Y. F.: Methane Dynamics in Northern Peatlands: A Review, Pedosphere, 19, 409–421, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0160(09)00003-4, 2009.

Lai, O. Y.: Peat moisture and thermal regimes for peatlands undergoing active extraction, M.Sc. Thesis, McGill University, https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/d791sn38s (last access: 1 September 2025), 2022.

Lenth, R., Singmann, H., Love, J., Buerkner, P., and Herve, M.: Emmeans: R Package Version 4.0-3 [code], http://cran.r-project.org/package=emmeans (last access: 1 October 2025), 2018.

Li, Q., Gogo, S., Leroy, F., Guimbaud, C., and Laggoun-Défarge, F.: Response of Peatland CO2 and CH4 Fluxes to Experimental Warming and the Carbon Balance, Frontiers in Earth Science, 9, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2021.631368, 2021.

Limpens, J., Berendse, F., Blodau, C., Canadell, J. G., Freeman, C., Holden, J., Roulet, N., Rydin, H., and Schaepman-Strub, G.: Peatlands and the carbon cycle: from local processes to global implications – a synthesis, Biogeosciences, 5, 1475–1491, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-5-1475-2008, 2008.

Liu, H., Rezanezhad, F., Zhao, Y., He, H., Van Cappellen, P., and Lennartz, B.: The apparent temperature sensitivity (Q10) of peat soil respiration: A synthesis study, Geoderma, 443, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2024.116844, 2024.

Mäkiranta, P., Laiho, R., Fritze, H., Hytönen, J., Laine, J., and Minkkinen, K.: Indirect regulation of heterotrophic peat soil respiration by water level via microbial community structure and temperature sensitivity, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 41, 695–703, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.01.004, 2009.

Matzner, E. and Borken, W.: Do freeze-thaw events enhance C and N losses from soils of different ecosystems? A review, European Journal of Soil Science, 59, 274–284, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2007.00992.x, 2008.

Mauder, M. and Foken, T.: Documentation and instruction manual of the eddy covariance software package TK2, Universität Bayreuth, Abt, Mikrometeorologie, Arbeitsergebnisse 26, 42 pp., ISSN 1614-8926, 2004

McNeil, P. and Waddington, J. M.: Moisture controls on Sphagnum growth and CO2 exchange on a cutover bog, Journal of Applied Ecology, 40, 354–367, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2664.2003.00790.x, 2003.

Nielsen, C. K., Elsgaard, L., Jorgensen, U., and Laerke, P. E.: Soil greenhouse gas emissions from drained and rewetted agricultural bare peat mesocosms are linked to geochemistry, Science of the Total Environment, 896, 165083, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165083, 2023.

Ojanen, P. and Minkkinen, K.: The dependence of net soil CO2 emissions on water table depth in boreal peatlands drained for forestry, Mires and Peat, 24, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.19189/MaP.2019.OMB.StA.1751, 2019.

O'Kane, J. P. (Ed.): Advances in Theoretical Hydrology: A Tribute to James Dooge, Elsevier, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-89831-9.50010-7, 1992.

Natural Resources Canada: CanVec series: National topographic vector data [data set], Government of Canada, https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/8ba2aa2a-7bb9-4448-b4d7-f164409fe056 (last access: 1 September 2025), 2025.

Papale, D., Reichstein, M., Aubinet, M., Canfora, E., Bernhofer, C., Kutsch, W., Longdoz, B., Rambal, S., Valentini, R., Vesala, T., and Yakir, D.: Towards a standardized processing of Net Ecosystem Exchange measured with eddy covariance technique: algorithms and uncertainty estimation, Biogeosciences, 3, 571–583, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-3-571-2006, 2006.

Peltola, O., Hensen, A., Belelli Marchesini, L., Helfter, C., Bosveld, F. C., van den Bulk, W. C. M., Haapanala, S., van Huissteden, J., Laurila, T., Lindroth, A., Nemitz, E., Röckmann, T., Vermeulen, A. T., and Mammarella, I.: Studying the spatial variability of methane flux with five eddy covariance towers of varying height, Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 214–215, 456–472, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2015.09.007, 2015.

Petrone, R. M., Price, J. S., Waddington, J. M., and von Waldow, H.: Surface moisture and energy exchange from a restored peatland, Québec, Canada, Journal of Hydrology, 295, 198–210, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2004.03.009, 2004.

Price, J. S.: Role and character of seasonal peat soil deformation on the hydrology of undisturbed and cutover peatlands, Subsurface Hydrology, 39, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002WR001302, 2003.

QGIS Development Team: QGIS Geographic Information System, Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project [code], http://qgis.org (last access: 1 October 2025), 2024.

R Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing [code], Vienna, Austria, https://www.R-project.org (last access: 1 October 2025), 2021.

Rankin, T., Strachan, I. B., and Strack, M.: Carbon dioxide and methane exchange at a post-extraction, unrestored peatland, Ecological Engineering, 122, 241–251, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2018.06.021, 2018.

Raz-Yaseef, N., Torn, M. S., Wu, Y., Billesbach, D. P., Liljedahl, A. K., Kneafsey, T. J., Romanovsky, V. E., Cook, D. R., and Wullschleger, S. D.: Large CO2 and CH4 emissions from polygonal tundra during spring thaw in northern Alaska, Geophysical Research Letters, 44, 504–513, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016gl071220, 2017.

Reumer, M., Harnisz, M., Lee, H. J., Reim, A., Grunert, O., Putkinen, A., Fritze, H., Bodelier, P. L. E., and Ho, A.: Impact of Peat Mining and Restoration on Methane Turnover Potential and Methane-Cycling Microorganisms in a Northern Bog, Applied Environment Microbiology, 84, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02218-17, 2018.

Rezanezhad, F., Couture, R. M., Kovac, R., O'Connell, D., and Van Cappellen, P.: Water table fluctuations and soil biogeochemistry: An experimental approach using an automated soil column system, Journal of Hydrology, 509, 245–256, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2013.11.036, 2014.

Riederer, M., Serafimovich, A., and Foken, T.: Net ecosystem CO2 exchange measurements by the closed chamber method and the eddy covariance technique and their dependence on atmospheric conditions, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 7, 1057–1064, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-7-1057-2014, 2014.

Riutta, T., Laine, J., and Tuittila, E-S.: Sensitivity of CO2 exchange of fen ecosystem components to water level variation, Ecosystems, 10, 718–733, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-007-9046-7, 2007.

Rochefort, L., Strack, M. and Chimner, R. (coordinating lead authors): Regional assessment for North America, Chapter 7, 193–200 pp., in: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Global peatlands assessment – The state of the world's peatlands: Evidence for action toward the conservation, restoration and sustainable management of peatlands, Global Peatlands Initiative, United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, 2022.

RStudio Team: RStudio: Integrated Development for R, RStudio [code], Boston, MA, http://www.rstudio.com/ (last access: 1 October 2025), 2020.

Saarnio, S., Morero, M., Shurpali, N. J., Tuittila, E. S., Mäkilä, M., and Alm, J.: Annual CO2 and CH4 fluxes of pristine boreal mires as a background for the lifecycle analyses of peat energy, Boreal Environment Research, 12, 101–113, https://doi.org/10.60910/thg7-mxk6, 2007.

Salm, J.-O., Maddison, M., Tammik, S., Soosaar, K., Truu, J., and Mander, Ü.: Emissions of CO2, CH4 and N2O from undisturbed, drained and mined peatlands in Estonia, Hydrobiologia, 692, 41–55, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-011-0934-7, 2012.

Scott-Denton, L. E., Rosenstiel, T. N., and Monson, R. K.: Differential controls by climate and substrate over the heterotrophic and rhizospheric components of soil respiration, Global Change Biology, 12, 205–216, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.01064.x, 2006.

Sharma, B., Moore, T. R., Knorr, K.-H., Teickner, H., Douglas, P. M. J., and Roulet, N. T.: Horticultural additives influence peat biogeochemistry and increase short-term CO2 production from peat, Plant and Soil, 505, 449–464, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-024-06685-9, 2024.

Sharma, B., He, H., and Rouelt, N. T.: CO2 emitted from peat use in horticulture supports a lower emission factor, Carbon Management, 16, 2468476, https://doi.org/10.1080/17583004.2025.2468476, 2025.

Shurpali, N. J., Hyvönen, N. P., Huttunen, J. T., Biasi, C., Nykänen, H., Pekkarinen, N., and Martikainen, P. J.: Bare soil and reed canary grass ecosystem respiration in peat extraction sites in Eastern Finland, Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology, 60, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0889.2007.00325.x, 2008.