the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Proteomic and biogeochemical perspectives on cyanobacteria nutrient acquisition – Part 2: quantitative contributions of cyanobacterial alkaline phosphatases to bulk enzymatic rates in the subtropical North Atlantic

Noelle A. Held

Korinna Kunde

Clare E. Davis

Neil J. Wyatt

Elizabeth L. Mann

E. Malcolm S. Woodward

Matthew McIlvin

Alessandro Tagliabue

Benjamin S. Twining

Claire Mahaffey

Mak A. Saito

Maeve C. Lohan

Microbial enzymes alter marine biogeochemical cycles by catalyzing chemical transformations that bring elements into and out of particulate organic pools. These processes are often studied through enzyme rate-based estimates and nutrient-amendment bioassays, but these approaches are limited in their ability to resolve species-level contributions to enzymatic rates. Molecular methods including proteomics have the potential to link the contributions of specific populations to the overall community enzymatic rate; this is important because organisms will have distinct enzyme characteristics, feedbacks, and responses to perturbations. Integrating molecular methods with rate measurements can be achieved quantitatively through absolute quantitative proteomics. Here, we use the subtropical North Atlantic as a model system to probe how a combination of traditional bioassays and absolute quantitative proteomics can provide a more comprehensive understanding of nutrient limitation in marine environments. The experimental system is characterized by phosphorus stress and potential metal-phosphorus co-limitation due to dependence of the organic phosphorus scavenging enzyme alkaline phosphatase on metal cofactors. We performed nutrient amendment incubation experiments to investigate how alkaline phosphatase absolute abundance and activity is affected by trace metal additions and develop an inventory of cyanobacterial alkaline phosphatases. We show that the two most abundant picocyanobacteria, Prochlorocccus and Synechococcus are minor contributors to total alkaline phosphatase activity as assessed by a widely used enzyme assay, with Prochlorococcus accounting for 3 %–35 % and Synechococcus contributing 0.5 %–5 % of alkaline phosphatase activity depending on location and metal cofactor. This was true even when trace metals were added, despite both species having the genetic potential to utilize both the Fe and Zn containing enzymes, PhoX and PhoA respectively. Serendipitously, we also found that the alkaline phosphatases responded to cobalt additions suggesting possible substitution of the metal center by Co in natural populations of Prochloroccocus (substitution for Fe in PhoX) and Synechococcus (substitution for Zn in PhoA). This integrated approach allows for a nuanced interpretation of how nutrient limitation affects marine biogeochemical cycles and highlights the benefit of building quantitative connections between rate and “-omics” based measurements.

- Article

(3996 KB) - Full-text XML

- Companion paper

-

Supplement

(1247 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Microbial enzymes alter marine biogeochemical cycles by catalysing chemical transformations and facilitating the movement of elements through planetary reservoirs. On one hand, enzyme contributions from different groups of microbes can be considered collectively, for instance in rate-based or bioassay incubation experiments where the activities of the entire microbial community are aggregated. On the other hand, we anticipate that the enzymes of different organisms will have different activities and responses to perturbations; this means that resolving enzyme provenance could enhance the quantitative connection between microbial activity and biogeochemical rates (e.g. the goals of the fledgling Biogeoscapes program; Saito et al., 2024). “-Omics” based methods, particularly proteomics which directly resolves protein/enzyme concentrations, can provide a window into the relationships between microbial abundance, enzyme concentration, and biogeochemical rates.

In this work we use quantitative proteomics to constrain the relative contributions of different microbes (Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus) to biogeochemical rates of alkaline phosphatase activity in the oligotrophic subtropical North Atlantic gyre. In this region, primary production is constrained by availability of dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) and phosphorus (DIP), but inputs of atmospherically derived iron (Fe) from Saharan desert dust create a niche for nitrogen fixation, partially alleviating nitrogen limitation but driving the system to DIP depletion (Martiny et al., 2019; Moore et al., 2013). Lack of DIP then drives a shift towards the acquisition of the abundant yet less bioavailable dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP) by phytoplankton (Lomas et al., 2010; Mather et al., 2008). The DOP pool includes relatively labile phosphomono- and diesters (together ∼75 % to 85 % of DOP) that derive from ribonucleic acids, adenosine phosphates and phospholipids (Kolowith et al., 2001; Young and Ingall, 2010). These compounds cannot be directly assimilated but require the phosphate group to be cleaved from the ester moiety first. Cleaving is catalysed by a range of hydrolytic enzymes, such as alkaline phosphatases, which are common in marine microbes, including bacterial as well as eukaryotic phytoplankton (Dyhrman and Ruttenberg, 2006; Luo et al., 2009; Shaked et al., 2006). Reflecting this, alkaline phosphatase activity (APA) is high across the oligotrophic gyres (Browning et al., 2017; Davis et al., 2019; Duhamel et al., 2010; Mahaffey et al., 2014; Wurl et al., 2013).

Alkaline phosphatase activity is commonly regulated by intracellular phosphate levels (Santos-Beneit, 2015) and appears to be closely linked to low ambient DIP concentrations (Mahaffey et al., 2014). However, these enzymes also have a metal dependence, as metal co-factors are involved in the hydrolysis process at the active site. Different alkaline phosphatases exist that, while sharing function, evolved independently and have distinct metal requirements. For example, in Escherichia coli (E. coli) the alkaline phosphatase PhoA has two Zn2+ (zinc) or Co2+ (cobalt) ions and one Mg2+ (magnesium) ion at each active site per homodimer (Coleman, 1992), and in Pseudomonas fluorescens the monomeric alkaline phosphatase PhoX has two Fe3+ ions and three Ca3+ (calcium) ions (Yong et al., 2014). The active sites of PhoA and PhoX in marine microbes have yet to be biochemically characterized but based on sequence homology are presumed to be like these model organisms, leading to the hypothesis that alkaline phosphatase activity to be limited by scarce Fe, Zn, or Co trace metals in the marine environment (Lohan and Tagliabue, 2018).

Global change is predicted to intensify phosphorus stress and alter trace metal and nutrient cycles in the ocean (Hoffmann et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2014). Throughout the North Atlantic, the utilisation of DOP is widespread (Mather et al., 2008) and whole community rates of APA are high compared with other oceanic regions (Duhamel et al., 2010; Mahaffey et al., 2014). At this time, it is not known which microbes and enzyme types are responsible for bulk APA in the North Atlantic and elsewhere. Resolving this could lead to a more quantitative understanding of how APA activity is regulated in the modern ocean, allowing better predictions of future changes in enzyme abundance and activity and the resulting influence on carbon export. In this study, we use field-based quantitative proteomics to develop an inventory of alkaline phosphatase activity and to identify nutrient-related regulatory controls on alkaline phosphatase that are distinct for different organisms. We use this as a proof of concept for developing quantitative connections between biogeochemical rates and “-omics” based measurements of microbial enzymes, a topic that is of interest to ongoing international efforts to characterize ocean metabolism.

2.1 Shipboard bioassays

All samples for this study were collected on board the RRS James Cook during research cruise JC150 (GEOTRACES process study GApr08), on a zonal transect at 22° N leaving Guadeloupe on 26 June and arriving in Tenerife on 12 August 2017, with multiple stations occupied for bioassays. A detailed description of the bioassays and analysis of environmental parameters is presented in Part 1 (Mahaffey et al., 2026).

Briefly, surface seawater was collected and processed according to trace metal clean protocols and before dawn. For each location, duplicate or triplicate 24 L polycarbonate (Nalgene) carboys were filled and spiked with additions of Fe, Zn or Co, as detailed in Table 1. The seawater was incubated at ambient sea surface temperature and 50 % surface light level for 48 h from dawn to dawn with a 12:12 h simulated light cycle using white daylight LED panels.

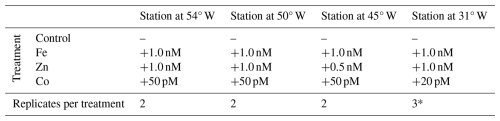

Table 1Bioassay details at each station, showing the types of treatments, the amount of metal added, and the number of replicates per treatment for which proteomics analyses were conducted.

Note that one of the three replicates of the Fe addition at the Station at 31° W (*) was removed as an outlier from all further analysis.

After the incubation period, subsamples for proteins were collected into acid cleaned 10 L polycarbonate carboys (Nalgene) and immediately filtered, collecting the >0.22 µm fraction on polyethersulfone membrane filter cartridges (Millipore, Sterivex) and recording the filtered volume. Any remaining water was pressed out with an air-filled syringe, the filtration unit was sealed with clay and then frozen at −80 °C. This procedure was repeated for the second (and third where applicable) replicate of each treatment.

2.2 Alkaline phosphatase activity (APA) rate measurements

Total APA was measured in unfiltered seawater samples using the synthetic fluorogenic substrate 4- methylumbeliferyll-phosphate (MUFP, Sigma Aldrich, Ammerman 1993, Davis et al 2019). MUFP stock solutions (100 mM in 2-methoxyethanol) were diluted with Milli-Q deionized water (200 µM stock). Unfiltered seawater was spiked with the MUFP substrate to final concentrations of 500 or 2000 nM MUFP for single substrate additions, or a series of replicates were incubated over a final MUFP concentration range from 100 to 2000 nM for the determination of enzyme kinetic parameters, Vmax and Km. Once spiked, samples were incubated in polycarbonate bottles in triplicate in the temperature and light adjusted reefer container for up to 12 h.

MUFP hydrolysis to the fluorescent product, 4-methylumbelliferone (MUF), was measured at regular intervals (typically every 90 min) over a period of up to 8–12 h using a Turner 10Au field fluorometer (365 nm excitation, 455 nm emission) after the addition of a buffer solution (3:1 sample: 50 mM sodium tetraborate solution, pH 10.5). A calibration was produced at the start and end of the cruise using MUF standards (concentration range 0–1000 nM) to ensure linearity of the fluorescence of MUF over the expected concentration range. Fluorescence response factors were determined daily using freshly prepared 200 nM MUF stocks and was used to convert the rate of change in fluorescence to MUFP hydrolysis rate, here considered to be synonymous with volumetric APA (nM P h−1). Boiled seawater blanks (500 nM MUFP) were incubated in parallel with samples to ensure that there was no significant change in fluorescence due to abiotic degradation or hydrolysis over time. Enzyme kinetic parameters were determined using a range of MUFP concentrations. Michaelis-Menten equation was transformed to produce substrate-response curves or linear regression plots and the maximum hydrolysis rates (Vmax) and half saturation constant (Km) were determined using the Hanes-Woolf plot graphical linearization of the Michaelis-Menten equation following Duhamel et al. (2011).

2.3 Protein extraction and digestion

All plastics materials were washed with ethanol and dried before usage. All samples from one station were processed together in one extraction and digestion cycle. The frozen Sterivex filter cartridges were transported to the laboratory on ice and cut open with a tube cutter. The filters were cut out from their holders with razor blades and placed into 2 mL microfuge tubes (Eppendorf). Following previously established (Held et al., 2020; Saito et al., 2014), proteins were extracted in a 1 % sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer for 15 min at 20 °C, followed by 10 min at 95 °C for denaturation, and 1 h at 20 °C while shaking at 350 rpm. The protein extract was then centrifuged at 13.5 rpm for 20 min, with the impurities-free supernatant collected and then spin-concentrated for 1 h in 5 kD membrane filters (Vivaspin, GE Healthcare). Total protein concentrations were then measured by bicinchoninic assay (BCA) (Pierce) on a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific). Proteins were left to precipitate in a 50:50 solvent mixture of methanol and acetone (Fisher) with 0.004 % concentrated HCl (Sigma, ACS 37 %) for 5 d at −20 °C. At the end of the precipitation period, samples were centrifuged at 13.5 rpm at 4 °C, supernatants were removed, and the remaining protein pellets were vacuum-dried (DNA110 Savan SpeedVac, ThermoFisher). Pellets were redissolved in 50 µL SDS buffer, and the post-precipitation total protein concentrations were measured via a second BCA assay to assess recovery. The protein extracts were digested with the proteolytic enzyme trypsin (1 µg per 20 µg protein; Promega #V5280) in a polyacrylamide tube gel (Lu and Zhu, 2005). The digested samples were concentrated by vacuum drying and stored at −20 °C until analysis. The final volume was recorded to calculate the total protein concentration in the processed sample, and adjusted to ∼1 µg µL−1.

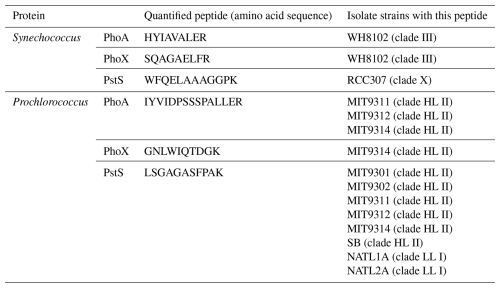

2.4 Target protein selection

Protein biomarkers for Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus were chosen to detect DIP stress (PstS) and related coping mechanisms via DOP hydrolysis (PhoA and PhoX) in our samples (Table 2). PstS is the substrate-binding protein of the high-affinity phosphate ABC (ATP-Binding Cassette) transporter, which is upregulated under low intracellular phosphate concentrations via the pho regulon and has previously been used as an indicator of DIP stress (Cox and Saito, 2013; Martiny et al., 2006; Scanlan et al., 1993). PhoA and PhoX are the -dependent and Fe-dependent alkaline phosphatases, respectively, which facilitate the acquisition of phosphorus from the DOP pool.

Table 2Details on the quantified peptide biomarkers that are used to represent each protein in the subsequent plots and discussions. For Prochlorococcus strains, “HL” and “LL” refer to high-light and low-light adapted strains, respectively.

The criteria for a peptide of the protein biomarker to be used for quantification were as follows. Firstly, we attempted to minimise the presence of methionine and cysteines because they are subject to oxidation and cause modifications of the mass-to-charge ratio () during the analyses. Secondly, the specificity and least common ancestor of each tryptic peptide was assessed using METATRYP (https://metatryp.whoi.edu/, last access: October 2023) (Saunders et al., 2020). It has been demonstrated that carefully selected tryptic peptides, screened by using tryptic peptides databases made from genome sequences like METATRYP, can be used to identify specific proteins in mixed microbial assemblages to the species or even sub-species (ecotype) taxonomic resolution (Saito et al., 2015). Finally, the performance of each precursor ion was visually inspected in Skyline (MacLean et al., 2010) for peak shape and signal to noise-ratio during uncalibrated test measurements using a target list containing many peptides of cyanobacterial alkaline phosphatases on a subset of the incubation samples.

2.5 Isotopically labelled standard peptides

The absolute quantitation of the target peptides was achieved using heavy nitrogen isotope-labelled peptide standards (Saito et al., 2020). Briefly, DNA was synthesized containing the reverse-translated gene sequences for our target peptides interspaced with spacer sequences and ligated with a PET30a(+) plasmid vector using the BAMHI 5′ and XhoI 3 restriction sites (Novagen; obtained through PriorityGENE, Genewiz). Different nucleotide sequences were used to encode for the spacer (amino acid sequence: TPELFR) to avoid repetition. As per manufacturer instructions, the plasmid was suspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) to 10 ng µL−1 and of this 1 µL was added to 20 µL competent Tuner(DE3)pLysS E. coli cells on ice. The cells were heated to 42 °C for 30 s to initiate transformation, followed by 2 min on ice. At room temperature, 80 µL 15N-enriched (98 %, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories), kanamycin-containing (50 µL mL−1) SOC medium was added, and cells were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C at 300 rpm. Subsequently, 25 µL were transferred to pre-heated (37 °C) 50 µg mL−1 agar plates and incubated overnight. One colony was added to 500 µL 15N-enriched SOC medium containing 50 µL mL−1 kanamycin as a starter culture and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C at 350 rpm. Next, 200 µL of the starter culture were transferred into 50 mL flat incubation flasks with 10 mL SOC medium and incubated for approximately 3 h at 37 °C and 350 rpm until the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.6. Protein production was induced by the addition of 100 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside to the culture and incubating at 25 °C overnight. Inclusion bodies were initially harvested using BugBuster protein extraction protocols (Novagen). The remaining pellet containing the inclusion bodies, i.e. the insoluble protein fraction, was resuspended in 400 µL 6 M urea, left on the shaker table at 350 rpm at room temperature for 3 h, and then moved to the fridge overnight. The next morning, the proteins were reduced, alkylated, and digested with trypsin as outlined above for the bioassay samples, and stored frozen at −20 °C until use.

2.6 Absolute protein quantitation

To determine the absolute concentration of the peptides in the heavy peptide mixture, commercial standard peptides of known concentration were used. In addition to the peptides of interest, a range of tryptic peptide sequences from commercially available standards (apomyoglobin, Sigma; Pierce Bovine Serum Albumin, ThermoFisher) were included in the original plasmid design. Using these, the calibrated concentration of the heavy peptide mixture had a relative standard deviation of 57 %, with the standard deviation resulting from the cross-peptide and cross-replicate variability (n=3) (Fig. S1). A systematic method-focused study addressing the precision and accuracy of these measurements as well as the development of reference materials will be essential for using absolute quantitative proteomics in the marine environment in the future (Saito et al., 2024). The linear performance range of each heavy peptide standard was assessed using standard curves of the peptide mixture. Targeted proteomic measurements were made by high pressure liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) on an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid Mass Spectrometer (ThermoFisher). Two µg of each sample diluted to 10 µL in buffer B (0.1 % formic acid in acetonitrile) was spiked with 10 fmol µL−1 of the heavy peptide mixture and injected into the Dionex nanospray HPLC system at a flow rate of 0.17 µL min−1. The chromatography consisted of a nonlinear gradient from 5 % to 95 % of buffer B with the remaining concentration consisting of buffer A (0.1 % formic acid in LC-grade H2O). Precursor (MS1) ions were scanned for the of the heavy peptide standards and their natural light counterparts. The mass spectrometer was run in parallel reaction monitoring mode such that only peptides included in the precursor inclusion list were selected for fragmentation. Absolute peptide concentrations were calculated from the ratio of the peak areas of the product ions (MS2) of the heavy peptide of known concentration to the natural light peptide (calculated in Skyline; MacLean et al., 2010). Manual validation of peak shapes was performed for each peptide and sample. Differences between samples with regards to filtration volume, initial protein mass and recovery after precipitation were accounted for. Final peptide concentrations will hereafter be used to represent corresponding protein concentrations, with the caveat that the measurements are not able to discern active versus non-active proteins. The status of metalation and if the protein is correctly folded or functions as a polymeric complex cannot be determined from this method.

2.7 Identification of significant responses to metal additions

Changes in protein concentrations in response to metal additions were compared relative to the unamended control treatment after 48 h. This approach accounts for any bottle effects. Due to the unique challenges of ocean proteomics sampling and large-scale trace-metal clean bioassays treatment replication was limited to n=2 at 54, 50 and 45° W and to n=3 at 31° W. Many statistical tests assume normal distributions, which for n=2 is not assessable. Therefore, in our case, significant differences in protein concentrations were evaluated using a two-fold change criterion, in which the concentrations in all replicates of the metal treatments must lie outside a two-fold change in the average ± one standard deviation of the control to be deemed a significant response. The fold-change in expression and in particular the two-fold change is a commonly used metric to identify proteins that are significantly more or less expressed across different conditions (Carvalho et al., 2008; Lundgren et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2006).

For the biogeochemical parameters measured in the bioassays, i.e. Chl a, APA and cell counts replication was not limited to n=2 in most cases. Where n=3, ANOVA (a=0.05) followed by Tukey posthoc tests were applied to compare the Control treatments with other treatments.

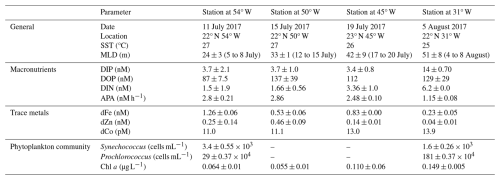

3.1 Biogeochemical setting

The oligotrophic subtropical North Atlantic is marked by high deposition of Saharan desert dust, delivering large amounts of Fe and other lithogenic trace metals to the surface ocean (Kunde et al., 2019). During JC150, contrasting biogeochemical regimes existed in the western and eastern basin with high-metal, low-phosphorus, low-nitrogen surface waters at 54° W and lower-metal, higher-phosphorus, higher-nitrogen surface waters at 31° W (Mahaffey et al., 2026, companion article). Furthermore, Synechococcus was two-fold more abundant in the west than in the east, whilst Prochlorococcus was more than six-fold more abundant in the west than the west and numerically more abundant than Synechoccocus throughout. Overall, the stations at 50 and 45° W exhibited biogeochemical intermediates to the conditions in the east and west. The confluence of gradients in both DIP and trace element availability, as well as clear shifts in microbial community structure, provide a natural field laboratory to probe how environmental drivers differentially influence the contributions of dominant microbes to whole-ecosystem enzyme activity.

Table 3Date, location and biogeochemical conditions at 40 m depth at the start (t0) of the bioassays. Biogeochemical parameters are presented as the average ± one standard deviation of replicate t0 samples, except for the singlet samples of DOP at Station 4 and dCo at all stations. Mixed layer depths (MLD; defined after 52) averages over multiple days, as these were not always determined on the exact day of bioassay set-up.

3.2 Alkaline phosphatase responded differently in the traditional vs proteomic bioassays

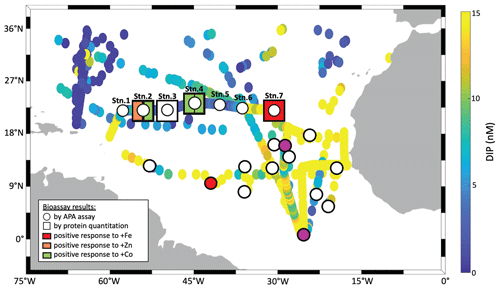

We measured responses in alkaline phosphatase activity (traditional bioassay) and enzyme identity and provenance (proteomic assay) to metal additions across the North Atlantic gyre. Both assays were performed on matched samples at four locations (St 2, 3, 4, 7; Fig. 1), allowing direct comparison of the results. In all cases for the traditional assay (shown as circles in Fig. 1), bulk alkaline phosphatase activity did not increase significantly upon metal additions (see also Fig. 2). However, the proteomic assay revealed that specific alkaline phosphatases did respond positively to the metal additions (squares in Fig. 1), depending on the location and metal added. The discrepancy between the traditional bioassay (no response) and proteomic assay (specific, albeit patchy responses) merited additional exploration of the two approaches, which we detail below. One important explanation emerges from the fact that the APA assay covers the entire microbial community (i.e. everything from bacteria to eukaryotes) but the proteomics measurements are specific to a subset of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus.

Figure 1Summary of traditional and molecular bioassay results from this manuscript and others. Map of the North Atlantic showing surface phosphate concentrations (data compiled by Martiny et al., 2019 and augmented with data from Browning et al., 2017). Overlain are locations of bioassays, where the response of APA to metal additions was tested (circles), and of bioassays, where the absolute concentration of the alkaline phosphatase proteins was measured in response to metal additions (squares). Bioassays of the present study include longitudinal station labels. The others are from Mahaffey et al. (2014) and Browning et al. (2017) as well as from additional bioassays during JC150 (Mahaffey et al., 2026). but where no protein measurements were made. Symbols at bioassay locations are coloured in orange, green or red, if a positive response was observed upon addition of Fe, Zn or Co respectively.

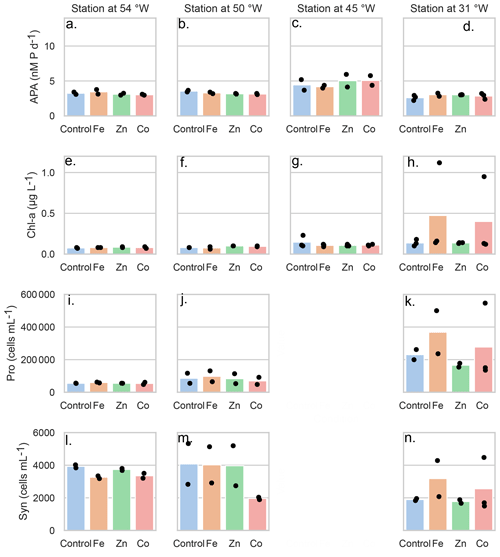

3.3 Variability in the response to metal additions in the traditional bioassays

As mentioned above, there was no significant response in bulk alkaline phosphatase activity to metal additions at any of the stations. Here we focus on Stations 2, 3, 4, and 7, where matched proteomic assays were also conducted. However, alkaline phosphatase assays were conducted on incubations at all seven stations, and there was no response to metal addition at any of them, nor in APA rates normalized to chl a (Figs. S2–S5 and see Table S6 in the Supplement). Given this, we sought to address whether there were other observable shifts in microbial activity as a result of the metal additions, including in Chl a (a proxy for phytoplankton growth) and cell counts for Prochloroccocus and Synechococcus (Fig. 2). While there were no statistically significant changes, either positive or negative, in any of these conventional assays, there were differences between replicate incubation bottles and within the basal conditions across the stations. Despite our efforts to homogenize the incubations and work in large volumes, this variation seems to result from stochasticity of sampling the low biomass system of the subtropical North Atlantic gyre, particularly since there is clear variation among the control bottles as well as in the amended conditions. It is also consistent with past literature including Browning et al. (2017) in which only one in eight experiments showed a metal driven response in APA and Mahaffey et al. (2014) in which there was a positive response of APA to Zn only in the eastern basin (see Fig. 1). One possible explanation for the presence of the many null responses across the basin is that organisms could be re-allocating metals towards use in alkaline phosphatases when under phosphorus stress. Supporting this idea, a comparable re-allocation mechanism of cellular Fe between metalloproteins involved in biological N2 fixation and photosynthesis has previously been demonstrated in the diel cycle of Crocosphaera watsonii (Saito et al., 2011a). Regardless, the absence of significant responses in the biogeochemical parameters contrasted notably with the observed responses in protein data detailed below.

Figure 2Mean concentrations (bars) of the bioassay parameters after the addition of Fe, Zn and Co at the four stations), specifically concentrations of chlorophyll a (µg L−1), (A–D) rates of alkaline phosphatase (nM d−1), (E–H) Prochlorococcus abundance (cells mL−1) (I–K) and Synechococcus abundance (cells mL−1) (L–O). Dots represent the concentrations of each replicate. Note the data gap for cell counts at the Station at 45° W.

3.4 Strain-resolved cyanobacterial alkaline phosphatases did respond to metal additions

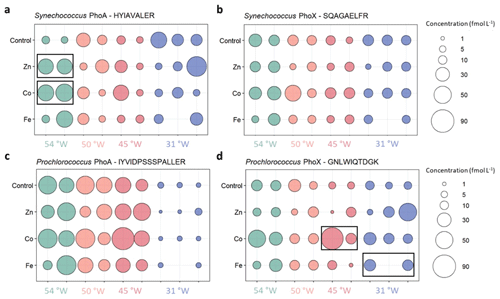

In contrast to the bioassay results, there were clear changes in proteomically-resolved alkaline phosphatase concentrations after metal additions. We focused on the enzymes PhoA and PhoX and used peptides that were specific to one or more strains of either Prochlorococcus or Synechococcus (Table 2) and represent a subset of the population of alkaline phosphatase enzymes in the ocean. We note that marine alkaline phosphatases are found at different subcellular localizations and are also known to be secreted to the environment (i.e. into the dissolved phase) (Li et al., 1998; Luo et al., 2009). Our measurements focus on the alkaline phosphatase associated with microbial cells (i.e. the particulate phase). Coming from an overview of the enzyme concentrations across isoforms, taxa and bioassays, we will discuss how these compare to the APA assay involving fluorogenic substrates.

Figure 3Absolute concentrations of the alkaline phosphatases PhoA (left column) and PhoX (right column) of Synechococcus (top) and Prochlorococcus (bottom) in the different metal treatments or the unamended control at the four probed stations. Bubbles of the same colour are replicates of the same treatment and show the concentrations as fmol enzyme per L seawater. Black boxes indicate significant change from Control treatment.

The results of all measured alkaline phosphatase concentrations are shown in Fig. 3 and all data is compiled in Table S5. Synechococcus PhoA and PhoX concentrations in the control treatments ranged from 6 to 43 and 6 to 26 fmol L−1, respectively, with no clear cross-basin trend despite a strong west-to-east decreasing gradient in Synechococcus cell abundance (Table 3). Similarly, Prochlorococcus PhoA and PhoX concentrations in the control treatments ranged from 2 to 55 and 6 to 23 fmol L−1, respectively, but with elevated PhoA at in the west and the lowest concentrations at 31° W, which is opposite to the west-to-east increasing gradient in Prochlorococcus cell abundance. This suggests that we observed a gradient in DIP/trace metal nutrient stress for Prochlorococcus, but not for Synechococcus.

Our measured alkaline phosphatase concentrations were similar, albeit at the lower end, to concentrations reported for other cyanobacterial enzymes and nutrient regulators from the North Pacific ( to 103 fmol L−1) (Saito et al., 2014). Interestingly, our alkaline phosphatase concentrations occurred at the same concentration range as other macronutrient stress indicators (response regulator protein PhoP, sulfolipid biosynthesis protein SqdB, nitrogen regulatory protein P-II), all of which did not exceed tens of fmol L−1 (Saito et al., 2014). In contrast, concentrations of the Prochlorococcus PstS transporter protein were higher, ranging from 95 to 472 fmol L−1 (Table S5). This is within the concentration range of other cyanobacterial nutrient transporters, such as the urea transporter UrtA, measured previously (Saito et al., 2014). In mediating nutrient stress, particularly phosphorus stress, the relative role of transporter proteins (such as PstS) versus other strategically deployed enzymes like alkaline phosphatase in the oligotrophic specialists Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus, represents an interesting avenue for future research.

3.5 Evidence for direct biochemical regulation of certain alkaline phosphatases by metals

Our strain-specific, quantitative proteomics approach allowed us to resolve contrasting responses across the sites. The responses differed with varying phytoplankton species, alkaline phosphatase type and stimulating metal addition, consistent with differences in the biogeochemical regimes (Table 3). At the iron-rich westernmost station (Station 4; 54° W), the Synechococcus PhoA concentration increased six- and seven-fold upon addition of Zn (to 38±0.56 fmol L−1) and Co (to 47±6.8 fmol L−1) relative to the control (6.7±1.5 fmol L−1), respectively. At one intermediate Station (45° W), the Prochlorococcus PhoX concentration increased 8-fold upon addition of Co relative to the control. Notably, a direct response of alkaline phosphatase to an addition of Co has not been shown in the field before. In contrast, at the low iron easternmost station, the Prochlorococcus PhoX increased over two-fold upon Fe addition (to 18±2.6 fmol L−1) relative to the control (8.2±2.4 fmol L−1).

At least three scenarios are possible to explain the increased alkaline phosphatase concentrations of Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus in seawater in these treatments – two biochemical and one growth driven hypotheses. First, the metal addition may stimulate the production of the alkaline phosphatase enzyme via a direct or indirect metal regulation on the expression of this enzyme, as was previously observed for PhoA with Zn additions in Synechococcus cultures (Cox and Saito, 2013). Second, the metal addition may prevent the degradation of the existing alkaline phosphatases by filling empty metal co-factor sites (Bicknell et al., 1985), with the caveat that PhoA is likely to be periplasmic and hence unlikely to be actively degraded (Luo et al., 2009). Both biochemical scenarios allow for increased alkaline phosphatase concentrations at a constant cell abundance. The third explanation is that the alkaline phosphatase concentration increases because the metal addition stimulates overall cell growth, resulting in higher phosphorus demands and hence more production of alkaline phosphatase proteins by the cell. This could manifest itself as higher cell abundances in addition to increased alkaline phosphatase concentration per unit biomass.

While the different scenarios are not mutually exclusive, our quantitative proteomic approach allowed us to discern between biochemical and growth mechanisms by normalising the alkaline phosphatase concentrations to the total cell counts of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus, caveating that the cell counts are not strain-specific, unlike the peptide-based protein measurements. Cell counts did not change significantly across these treatments Mahaffey et al. (2026) which means that the trends of increased alkaline phosphatase concentration per L seawater persisted in bioassays (i.e. +Zn and +Co at 54° W and +Fe at 31° W; cell counts do not exist for 45° W) even when converted to the number of alkaline phosphatase enzymes per cell, indicating biochemical regulation as opposed to simply growth of the responsible organism. Specifically, the concentration of Synechococcus PhoA increased to 8418±673 enzymes cell−1 upon Co addition and to 6057±48 enzymes cell−1 upon Zn addition relative to 1025±257 enzymes cell−1 in the control at 54° W, while the concentration of the Prochlorococcus PhoX increased to 59 enzymes cell−1 upon Fe addition relative to 19±7 enzymes cell−1 in the control at 31° W. Therefore, a direct biochemical metal control on the alkaline phosphatase concentrations during the bioassays is plausible (i.e. either of the first two explanations) and adds weight to the hypothesis for localised metal-phosphorus co-limitation in the subtropical North Atlantic (Browning et al., 2017; Wisniewski Jakuba et al., 2008; Mahaffey et al., 2014; Saito et al., 2017; Shaked et al., 2006).

These estimates of enzyme copies per cell are potentially underestimates as multiple Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus ecotypes co-exist and the alkaline phosphatase peptide sequences probed here do not encompass all of them (Table 2). Moreover, it is also possible that there are additional isoforms of alkaline phosphatase present in these organisms that have yet to be identified (Bradshaw et al., 1981). Yet in these marine cyanobacteria, the cellular concentration of alkaline phosphatase was much higher compared to a measurement in the model bacterium E. coli, which contained ∼4 PhoA copies cell−1 (Wiśniewski and Rakus, 2014). This underscores the ecological demand for alkaline phosphatases due to the significant depletion of phosphorus in the marine environment. It is yet to be determined whether the per-cell estimates of alkaline phosphatases presented here are the norm for marine cyanobacteria, or whether these estimates are exceptionally high due to phosphorus stress in our study region.

While PhoX enzymes are unknown to use Co as a metal co-factor and the response at 45° W warrants further investigation, the substitution of Zn with Co in PhoA has been hypothesised previously based on the distributions of trace metals and phosphate in the Sargasso Sea (Wisniewski Jakuba et al., 2008; Saito et al., 2017). The results from 54° W support this hypothesis as the addition of both Zn and Co were associated with almost equal increases of the Synechococcus PhoA concentration relative to the control. It is thought that while Zn is the preferred metal centre for PhoA, it is possible to substitute Co for Zn in the protein, such as occurs in Thermotoga maritima (Wojciechowski et al., 2022) in vivo and in vitro in E. coli (Gottesman et al., 1969). Metabolic substitution capabilities between Zn and Co in carbonic anhydrases have previously been identified in marine phytoplankton, with similar or slightly reduced growth rates for a range of marine diatoms and coccolithophores, when Zn was replaced with Co in carbonic anhydrases (Dupont et al., 2006; Kellogg et al., 2020; Morel et al., 2020; Price and Morel, 1990; Sunda and Huntsman, 1995; Timmermans et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2007; Yee and Morel, 1996). However, in certain organisms such as in the coccolithophore Emiliana huxleyi, it is possible that Co is the preferred metal co-factor since the growth rate was higher under replete Co than under replete Zn. One reason could be the simultaneous development of ocean chemistry and cyanobacterial metabolism under the Co- and Fe-replete, but Zn-deplete conditions of the ancient ocean ∼2.5 Gyr ago (Dupont et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2024; Saito et al., 2003). Another explanation for Co use in alkaline phosphatases may require maintaining low intracellular availability of Zn to avoid toxicity through inhibition of Co insertion by high Zn into cobalamin (Hawco and Saito, 2018). Supporting this, the cyanobacteria Synechococcus bacillaris and Prochlorococcus were found to have absolute Co requirements for growth (Sunda and Huntsman, 1995). Together with these aspects, our insights from the bioassay response at 54° W merits further investigations into whether Synechococcus can interchange Zn and Co in PhoA, and indeed which metal is preferred. This would be an important insight for considerations of stoichiometric plasticity and niche partitioning across the vast Zn- and Co-depleted regions of the ocean, especially where dZn can become depleted to levels similar or below dCo (Kellogg et al., 2020).

Across all bioassays, the addition of Zn did not increase the concentration of any presumably Fe-dependent PhoX, and the addition of Fe did not increase the concentration of any presumably Zn- or Co-dependent PhoA. In other words, no significant unexpected responses were observed. Nevertheless, there are some non-significant trends upon the addition of Co that warrant further study. For example, the addition of Co increased the putative Fe-containing Prochlorococcus PhoX protein concentration dramatically in one of the replicates at 45° W and hence, Co could be an efficient metal co-factor in PhoX (as in the bacterium Pasteurella multocida; Wu et al., 2007), or at least, directly or indirectly stimulate production of PhoX. This contrasts with the results of Kathuria and Martiny (2011), who hypothesized an enzyme inhibiting role of Co (and Zn; with Fe untested) for the activity of both Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus PhoX by replacing Ca2+ at the active site.

Taken together, the results of our bioassays suggest that alkaline phosphatase enzymes are affected by trace metal concentrations, and that the response to Zn, Co or Fe may be species or strain specific. The metal effects differed between the responsive enzyme type (PhoA versus PhoX) and phytoplankton species (Prochlorococcus versus Synechococcus) at contrasting biogeochemical settings across the basin. It is plausible that the significant changes in protein concentration can result directly from the metal addition triggering more alkaline phosphatase production per cell. This demonstrates that the cycling of macronutrients and metals are intermittently linked and that the nature of that linkage depends on microbial community composition.

3.6 Towards a quantitative, in situ marine metalloproteome of Synechococcus

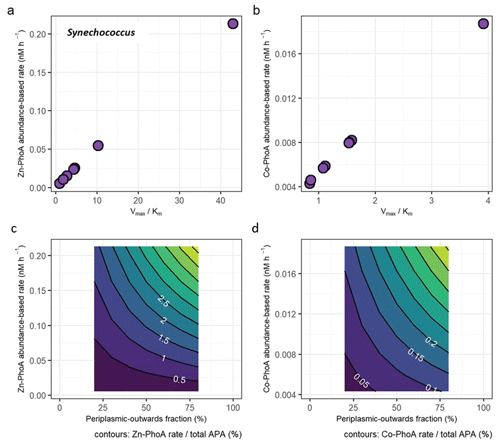

An advantage of absolute quantitative measurements over relative proteomics data is the ability to relate the absolute protein concentrations to other data types, including biological rate measurements and cellular metal stoichiometry. To this end, the concentrations of the Zn, Co or Fe-dependent alkaline phosphatases measured in this study naturally lead to two questions: First, how much metal is allocated as alkaline phosphatase co-factors in the cell, and how does this compare to total cellular metal content? Second, how does the APA estimated from enzyme abundance compare to assay-based APA?

To address these questions, model calculations were performed. Variables other than the absolute concentrations of the alkaline phosphatases were either measured concomitantly during the bioassays, such as cellular metal quotas, cell abundance, APA and DOP concentration, or sourced from the literature such as strain specific contribution to cell abundance, phosphoester contribution to the DOP pool, enzyme kinetics parameters and subcellular enzyme localization (Table S7). We chose to use the Synechococcus PhoA concentrations in the control treatments at 54° W after 48 h in these calculations for three reasons: First, cellular metal quotas of Synechococcus but not of Prochlorococcus were measured in this treatment, due to limited sampling capacity and small cell sizes for Prochloroccocus (Sofen et al., 2022). Second, enzyme kinetics parameters of the PhoA rather than the PhoX isoform are well documented in the literature (Lazdunski and Lazdunski, 1969). Third, estimates for the contribution of Synechococcus strain WH8102 (to which our measured PhoA is specific) to total Synechococcus counts exist from previous studies nearest to 54° W (Ohnemus et al., 2016). A similar reasoning applied to the phosphoester contribution to the DOP pool. For ease, more detailed explanations, all values, and assumptions are in Tables S3 and S4.

Equation (1a) approximates the cellular Zn allocation towards the Synechococcus PhoA from the replicate-averaged PhoA concentration in seawater normalised to cell abundance, assuming full metalation of the enzyme with four metal ions per dimer (Coleman, 1992). The cell abundance is a function of Synechococcus cell counts and the fractional abundance of strain WH8102, to which the measured PhoA is specific. Equation (1b) expresses the results of Eq. (1a) as a fraction of the total cellular Zn content.

The amount of metal allocated to PhoA in Synechococcus is 3054 atoms cell−1. This translates to a maximum fractional contribution towards the total cellular Zn content of 0.66 % after dividing by cellular Zn measured using SXRF (Table S1). If the co-factor in PhoA is assumed to be occupied by Co2+ instead of Zn2+, the fractional contribution to the cellular Co content is 38 %, due to the lower total cellular Co content of Synechococcus compared to Zn (Table S1). It is possible that the active sites of PhoA are occupied by a mixture of Zn and Co, incompletely metalated, or under competition by metals other than Zn or Co. Nevertheless, these low fractional contributions of PhoA-allocated Zn appear biochemically reasonable, as the majority of Zn in Synechococcus appears to be stored in metallothioneins to maintain Zn homeostasis and potentially supply alkaline phosphatases with Zn as needed (Cox and Saito, 2013; Mikhaylina et al., 2022). However, our bioassay results also suggest Zn may not be the preferred co-factor in Synechococcus PhoA: The larger response of this enzyme to Co additions at 54° W suggests the effective substitution of or even preference for Co (Fig. 2). This aligns with evolutionary arguments (see “Metal control on alkaline phosphatases”) and imply that PhoA is a potential major sink of cellular Co. This also implies that Synechococcus growth may be sensitive towards Co-phosphorus co-limitation in the oligotrophic ocean.

Figure 4(a) Protein abundance-based APA estimates of Synechococcus Zn-dependent PhoA as a function of different enzyme kinetic parameters Vmax and Km. (b) Same as (a), but with enzyme parameters for the less efficient Co-dependent PhoA. (see Table S2). (c) The fraction of the Zn-PhoA abundance-based APA from (a) over the total APA. (d) Same as (c) but using the Co-PhoA rates from (b). Note the scale difference between (a, c) and (b, d).

Equation (2a) approximates the Synechococcus PhoA-abundance based hydrolysis rate as a function of the PhoA concentration (converting molarity units to grams using its molecular weight), phosphoester substrate concentration, and Michaelis-Menten kinetics parameters Vmax and Km, the maximum reaction rate and half-saturation constant, respectively, derived from an E. coli homologue of PhoA (Table S2). Equation (2b) expresses the results of Eq. (2a) as a fraction of the “total APA”, a function of the measured MUF-P assay-based APA with a correction applied for the subcellular localisation of marine alkaline phosphatases, of which only the periplasmic-outwards fraction (∼20 % to 80 %) is detectable via the MUF-P assay. In other words, the calculated `total APA' accounts for both the dissolved and particulate activity. Details on made assumptions are in the Supplement (Table S2).

where substrate = DOP×phosphoester fraction.

The protein abundance-based rates range from 0.00517 to 0.213 nM h−1 for the Zn-dependent Synechococcus PhoA and from 0.00428 to 0.0187 nM h−1 for the Co-dependent PhoA (Fig. 4a and b), using the E. coli kinetics parameters for each metal that are slower under Co coordination. In terms of fractional contributions to total APA, the rate estimates translate to maximally 5.2 % for Zn-PhoA and 0.46 % for the Co-PhoA. Regardless of the choice of enzyme kinetics, it appeared that Synechococcus PhoA contributed a small component to the total APA in our bioassays. This concurs with the observed increase in concentration of Synechococcus PhoA upon metal addition versus the null response in APA. Applying the same calculation and kinetics parameters for the case of the Prochlorococcus PhoA yields abundance-based rates between 0.035 and 1.4 nM h−1 for the Zn-PhoA and between 0.029 and 0.13 nM h−1 for the Co-PhoA, which translate to maximal contributions to the total APA of 35 % and 3.1 %, respectively. These higher rates and fractional contributions compared to the Synechococcus PhoA are due to the higher concentrations of the Prochlorococcus PhoA than the Synechococcus PhoA in the chosen samples. The taxon-specific alkaline phosphatase concentrations illustrate the challenge of interpreting bulk enzyme activities when the functional enzyme class is produced by many biological taxa (cyanobacteria, heterotrophic bacteria, diatoms etc.). In essence, the different bioassay responses shown here demonstrate the need to further develop a “meta-biochemistry” capability to understand biogeochemical reactions at the mechanistic level.

The enzyme-based rates calculated here may be below that of bulk activity (APA assay) because our protein analysis focused on few species and only in the particulate phase. Alkaline phosphatase is known to be more abundant in the dissolved phase, for example as much as 72 % of the APA was observed in Red Sea samples to be in the dissolved phase (Li et al., 1998). Moreover, the periplasmic location of alkaline phosphatase has been observed to result in loss during preservation. In a preservation study, PhoA was notably the protein with the lowest recovery in Synechococcus WH8102 after a month in storage compared to 101±27 % for the fifty most abundant proteins (Saito et al., 2011b). The combination of multiple abundant and rare microbial sources of alkaline phosphatases together contribute to the particulate, and when secreted or lost, dissolved reservoirs that make up the bulk APA.

This study performs taxon-specific alkaline phosphatase isoform analysis via absolute quantitative proteomics on Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus, coupled to enzyme bioassays. This approach supports the use of Zn, Co and Fe in alkaline phosphatases in the natural oceanic environment, but also adds complexity to our understanding of how these enzymes are regulated in a biogeochemical context. Our mechanistic perspective revealed that these two highly abundant microbes are only minor contributors to bulk APA, which carries important implications for the interpretation of the widely used fluorescent APA assay. Additionally, within this picocyanobacterial class, we observed heterogeneous responses of the alkaline phosphatase enzymes depending on the protein, taxonomy, biogeochemical context, and treatment. This indicates that there is significant biological diversity in the responses of individual marine organisms to experimental treatments that can be resolved by combining enzyme assay measurements with quantitative proteomics. Our results indicate a need for biochemical characterisation of key marine alkaline phosphatases, particularly with regards to their kinetics and metal co-factors as highlighted by the potential importance of Co as a metal co-factor in PhoA and possibly PhoX. Future efforts to understand the biochemical properties of marine microbes will benefit the connected interpretation of molecular, enzymatic, and biogeochemical assays, and in turn our understanding of nutrient cycling in the ocean system.

Source data for all main and supplementary figures are provided in the Supplement. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [1] partner repository (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD053717/, last access: December 2025) with the dataset identifier PXD053717.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-23-923-2026-supplement.

NAH and KK wrote the initial manuscript draft. NAH and KK performed the proteomics analysis with help from MM and MAS. KK, NAH, NJW, CD, CM, MCL performed the experiments at sea. BST and ELM conducted the cell quota measurements. MCL, CM, AT and MAS led the research campaign. All authors commented on the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors would like to thank the captain and crew of the R.R.S. James Cook during cruise JC150, as well as all the scientific party members, who helped to conduct the bioassays. The authors would also like to thank Alastair Lough and Clément Demasy for the dCo measurements, and Julie Robidart and Rosalind Rickaby for fruitful discussions on this manuscript.

This research was supported by the National Environmental Research Council (UK) under grants NE/N001125/1 to MCL and NE/N001079/1 to CM, by the National Science Foundation (USA) under grant OCE1829819 to BST, OCE1924554, OCE1850719 and NIH R01GM135709 to MAS, and by the Graduate School of the National Oceanography Centre Southampton (UK) to KK. The writing process was also supported by the Simons Foundation under award 723552 and by the the USC Dornsife College of Arts and Sciences (NAH). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

This paper was edited by Paul Stoy and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Bicknell, R., Schaeffer, A., Auld, D. S., Riordan, J. F., Monnanni, R., and Bertini, I.: Protease susceptibility of zinc- and APO-carboxypeptidase A, Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 133, 787–793, https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-291X(85)90973-8, 1985.

Bradshaw, R. A., Cancedda, F., Ericsson, L. H., Neumann, P. A., Piccoli, S. P., Schlesinger, M. J., Shriefer, K., and Walsh, K. A.: Amino acid sequence of Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase., P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 78, 3473–3477, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.78.6.3473, 1981.

Browning, T. J., Achterberg, E. P., Yong, J. C., Rapp, I., Utermann, C., Engel, A., and Moore, C. M.: Iron limitation of microbial phosphorus acquisition in the tropical North Atlantic, Nature Communications, 8, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15465, 2017.

Carvalho, P. C., Fischer, J. S. G., Chen, E. I., Yates, J. R., and Barbosa, V. C.: PatternLab for proteomics: A tool for differential shotgun proteomics, BMC Bioinformatics, 9, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-316, 2008.

Coleman, J. E.: Structure and mechanism of alkaline phosphatase, Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct., 21, 441–483, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.002301, 1992.

Cox, A. D. and Saito, M. A.: Proteomic responses of oceanic Synechococcus WH8102 to phosphate and zinc scarcity and cadmium additions, Frontiers in Microbiology, 4, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2013.00387, 2013.

Davis, C., Lohan, M. C., Tuerena, R., Cerdan-Garcia, E., Woodward, E. M. S., Tagliabue, A., and Mahaffey, C.: Diurnal variability in alkaline phosphatase activity and the potential role of zooplankton, Limnology and Oceanography Letters, 4, 71–78, https://doi.org/10.1002/lol2.10104, 2019.

Duhamel, S., Dyhrman, S. T., and Karl, D. M.: Alkaline phosphatase activity and regulation in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, Limnology and Oceanography, 55, 1414–1425, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2010.55.3.1414, 2010.

Duhamel, S., Bjo, K. M., Wambeke, F. V., Moutin, T., and Karl, D. M.: Characterization of alkaline phosphatase activity in the North and South Pacific Subtropical Gyres: Implications for phosphorus cycling, 56, 1244–1254, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2011.56.4.1244, 2011.

Dupont, C. L., Yang, S., Palenik, B., and Bourne, P. E.: Modern proteomes contain putative imprints of ancient shifts in trace metal geochemistry, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 17822–7, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0605798103, 2006.

Dyhrman, S. T. and Ruttenberg, K. C.: Presence and regulation of alkaline phosphatase activity in eukaryotic phytoplankton from the coastal ocean: Implications for dissolved organic phosphorus remineralization, Limnology and Oceanography, 51, 1381–1390, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2006.51.3.1381, 2006.

Gottesman, M., Simpson, R. T., and Vallee, B. L.: Kinetic properties of cobalt alkaline phosphatase, Biochemistry, 8, 3776–3783, https://doi.org/10.1021/bi00837a043, 1969.

Hawco, N. J. and Saito, M. A.: Competitive inhibition of cobalt uptake by zinc and manganese in a pacific Prochlorococcus strain: Insights into metal homeostasis in a streamlined oligotrophic cyanobacterium, Limnology and Oceanography, 63, 2229–2249, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10935, 2018.

Held, N. A., Webb, E. A., McIlvin, M. M., Hutchins, D. A., Cohen, N. R., Moran, D. M., Kunde, K., Lohan, M. C., Mahaffey, C., Woodward, E. M. S., and Saito, M. A.: Co-occurrence of Fe and P stress in natural populations of the marine diazotroph Trichodesmium, Biogeosciences, 17, 2537–2551, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-2537-2020, 2020.

Hoffmann, L. J., Breitbarth, E., Boyd, P. W., and Hunter, K. A.: Influence of ocean warming and acidification on trace metal biogeochemistry, Marine Ecology Progress Series, 470, 191–205, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps10082, 2012.

Johnson, J. E., Present, T. M., and Valentine, J. S.: Iron: Life's primeval transition metal, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 121, e2318692121, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2318692121, 2024.

Kathuria, S. and Martiny, A. C.: Prevalence of a calcium-based alkaline phosphatase associated with the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus and other ocean bacteria, Environ. Microbiol., 13, 74–83, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02310.x, 2011.

Kellogg, R. M., McIlvin, M. R., Vedamati, J., Twining, B. S., Moffett, J. W., Marchetti, A., Moran, D. M., and Saito, M. A.: Efficient zinc/cobalt inter-replacement in northeast Pacific diatoms and relationship to high surface dissolved Co: Zn ratios, Limnology and Oceanography, 65, 2557–2582, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.11471, 2020.

Kim, I.-N., Lee, K., Gruber, N., Karl, D. M., Bullister, J. L., Yang, S., and Kim, T.-W.: Chemical oceanography. Increasing anthropogenic nitrogen in the North Pacific Ocean, Science, 346, 1102–1106, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1258396, 2014.

Kolowith, L. C., Ingall, E. D., and Benner, R.: Composition and cycling of marine organic phosphorus, Limnology & Oceanography, 46, 309–320, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2001.46.2.0309, 2001.

Kunde, K., Wyatt, N. J., González-Santana, D., Tagliabue, A., Mahaffey, C., and Lohan, M. C.: Iron Distribution in the Subtropical North Atlantic: The Pivotal Role of Colloidal Iron, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 33, 2019GB006326, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GB006326, 2019.

Lazdunski, C. and Lazdunski, M.: Zn2+ and Co2+-alkaline phosphatases of E. coli. A comparative kinetic study, Eur. J. Biochem., 7, 294–300, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1969.tb19606.x, 1969.

Li, H., Veldhuis, M., and Post, A.: Alkaline phosphatase activities among planktonic communities in the northern Red Sea, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 173, 107–115, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps173107, 1998.

Lohan, M. C. and Tagliabue, A.: Oceanic Micronutrients: Trace Metals that are Essential for Marine Life, Elements, 14, 385–390, https://doi.org/10.2138/gselements.14.6.385, 2018.

Lomas, M. W., Burke, A. L., Lomas, D. A., Bell, D. W., Shen, C., Dyhrman, S. T., and Ammerman, J. W.: Sargasso Sea phosphorus biogeochemistry: an important role for dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP), Biogeosciences, 7, 695–710, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-7-695-2010, 2010.

Lu, X. and Zhu, H.: Tube-Gel Digestion: A Novel Proteomic Approach for High Throughput Analysis of Membrane Proteins, Mol. Cell Proteomics, 4, 1948–1958, https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.M500138-MCP200, 2005.

Lundgren, D. H., Hwang, S. I., Wu, L., and Han, D. K.: Role of spectral counting in quantitative proteomics, Expert Review of Proteomics, 7, 39–53, https://doi.org/10.1586/epr.09.69, 2010.

Luo, H., Benner, R., Long, R. A., and Hu, J.: Subcellular localization of marine bacterial alkaline phosphatases, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 21219–21223, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0907586106, 2009.

MacLean, B., Tomazela, D. M., Shulman, N., Chambers, M., Finney, G. L., Frewen, B., Kern, R., Tabb, D. L., Liebler, D. C., and MacCoss, M. J.: Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments, Bioinformatics, 26, 966–968, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq054, 2010.

Mahaffey, C., Reynolds, S., Davis, C. E., Lohan, M. C., and Lomas, M. W.: Alkaline phosphatase activity in the subtropical ocean: insights from nutrient, dust and trace metal addition experiments, Frontiers in Marine Science, 1, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2014.00073, 2014.

Mahaffey, C., Held, N. A., Kunde, K., Davis, C., Wyatt, N., McIlvin, E. M. R., Woodward, E. M. S., Wrightson, L., Tagliabue, A., Lohan, M. C., and Saito, M.: Proteomic and biogeochemical perspectives on cyanobacteria nutrient acquisition – Part 1: Zonal gradients in phosphorus and nitrogen acquisition and stress revealed by metaproteomes of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus, Biogeosciences, 23, 905–922, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-23-905-2026, 2026.

Martiny, A. C., Coleman, M. L., and Chisholm, S. W.: Phosphate acquisition genes in Prochlorococcus ecotypes: Evidence for genome-wide adaptation, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 12552–12557, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0601301103, 2006.

Martiny, A. C., Lomas, M. W., Fu, W., Boyd, P. W., Chen, Y. L., Cutter, G. A., Ellwood, M. J., Furuya, K., Hashihama, F., Kanda, J., Karl, D. M., Kodama, T., Li, Q. P., Ma, J., Moutin, T., Woodward, E. M. S., and Moore, J. K.: Biogeochemical controls of surface ocean phosphate, Science Advances, 5, eaax0341, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax0341, 2019.

Mather, R., Reynolds, S., Wolff, G., Williams, R., Torres-Valdés, S., Woodward, E., Angela, L., Pan, X., Sanders, R., and Achterberg, E.: Phosphorus cycling in the North and South Atlantic Ocean subtropical gyres, Nature Geoscience, 1, 439–443, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo232, 2008.

Mikhaylina, A., Scott, L., Scanlan, D. J., and Blindauer, C. A.: A metallothionein from an open ocean cyanobacterium removes zinc from the sensor protein controlling its transcription, J. Inorg. Biochem., 230, 111755, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2022.111755, 2022.

Moore, C. M., Mills, M. M., Arrigo, K. R., Berman-Frank, I., Bopp, L., Boyd, P. W., Galbraith, E. D., Geider, R. J., Guieu, C., Jaccard, S. L., Jickells, T. D., Roche, J. L., Lenton, T. M., Mahowald, N. M., Marañón, E., Marinov, I., Moore, J. K., Nakatsuka, T., Oschlies, A., Saito, M. A., Thingstad, T. F., Tsuda, A., and Ulloa, O.: Processes and Patterns of Oceanic Nutrient Limitation, Nat. Geoscience, 6, 701–710, 2013.

Morel, F. M. M., Lam, P. J., and Saito, M. A.: Trace Metal Substitution in Marine Phytoplankton, Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 48, 491–517, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-053018-060108, 2020.

Ohnemus, D. C., Rauschenberg, S., Krause, J. W., Brzezinski, M. A., Collier, J. L., Geraci-Yee, S., Baines, S. B., and Twining, B. S.: Silicon content of individual cells of Synechococcus from the North Atlantic Ocean, Marine Chemistry, 187, 16–24, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2016.10.003, 2016.

Price, N. M. and Morel, F. M. M.: Cadmium and cobalt substitution for zinc in a marine diatom, Nature, 344, 658–660, https://doi.org/10.1038/344658a0, 1990.

Saito, M., Alexander, H., Benway, H., Boyd, P., Gledhill, M., Kujawinski, E., Levine, N., Maheigan, M., Marchetti, A., Obernosterer, I., Santoro, A., Shi, D., Suzuki, K., Tagliabue, A., Twining, B., and Maldonado, M.: The Dawn of the BioGeoSCAPES Program: Ocean Metabolism and Nutrient Cycles on a Changing Planet, Oceanog., 37, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2024.417, 2024.

Saito, M. A., Sigman, D. M., and Morel, F. M. M.: The bioinorganic chemistry of the ancient ocean: The co-evolution of cyanobacterial metal requirements and biogeochemical cycles at the Archean-Proterozoic boundary?, Inorganica Chimica Acta, 356, 308–318, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-1693(03)00442-0, 2003.

Saito, M. A., Bertrand, E. M., Dutkiewicz, S., Bulygin, V. V., Moran, D. M., Monteiro, F. M., Follows, M. J., Valois, F. W., and Waterbury, J. B.: Iron conservation by reduction of metalloenzyme inventories in the marine diazotroph Crocosphaera watsonii, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 2184–9, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1006943108, 2011a.

Saito, M. A., Bulygin, V. V., Moran, D. M., Taylor, C., and Scholin, C.: Examination of Microbial Proteome Preservation Techniques Applicable to Autonomous Environmental Sample Collection, Front. Microbiol., 2, 215, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2011.00215, 2011b.

Saito, M. A., McIlvin, M. R., Moran, D. M., Goepfert, T. J., DiTullio, G. R., Post, A. F., and Lamborg, C. H.: Multiple nutrient stresses at intersecting Pacific Ocean biomes detected by protein biomarkers, Science (New York, N.Y.), 345, 1173–1177, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1256450, 2014.

Saito, M. A., Dorsk, A., Post, A. F., McIlvin, M. R., Rappé, M. S., DiTullio, G. R., and Moran, D. M.: Needles in the blue sea: Sub-species specificity in targeted protein biomarker analyses within the vast oceanic microbial metaproteome, Proteomics, 15, 3521–3531, https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.201400630, 2015.

Saito, M. A., Noble, A. E., Hawco, N., Twining, B. S., Ohnemus, D. C., John, S. G., Lam, P., Conway, T. M., Johnson, R., Moran, D., and McIlvin, M.: The acceleration of dissolved cobalt's ecological stoichiometry due to biological uptake, remineralization, and scavenging in the Atlantic Ocean, Biogeosciences, 14, 4637–4662, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-14-4637-2017, 2017.

Saito, M. A., Mcilvin, M. R., Moran, D. M., Santoro, A. E., Dupont, C. L., Rafter, P. A., Saunders, J. K., Kaul, D., Lamborg, C. H., Westley, M., Valois, F., and Waterbury, J. B.: Abundant nitrite-oxidizing metalloenzymes in the mesopelagic zone of the tropical Pacific Ocean, Nature Geoscience, 13, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-020-0565-6, 2020.

Santos-Beneit, F.: The Pho regulon: a huge regulatory network in bacteria, Frontiers in Microbiology, 6, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00402, 2015.

Saunders, J. K., Gaylord, D. A., Held, N. A., Symmonds, N., Dupont, C., Shepherd, A., Kinkade, D. B., and Saito, M. A.: METATRYP v 2.0: Metaproteomic Least Common Ancestor Analysis for Taxonomic Inference Using Specialized Sequence Assemblies - Standalone Software and Web Servers for Marine Microorganisms and Coronaviruses, Journal of Proteome Research, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00385, 2020.

Scanlan, D. J., Mann, N. H., and Carr, N. G.: The response of the picoplanktonic marine cyanobacterium Synechococcus species WH7803 to phosphate starvation involves a protein homologous to the periplasmic phosphate-binding protein of Escherichia coli, Mol. Microbiol., 10, 181–191, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00914.x, 1993.

Shaked, Y., Xu, Y., Leblanc, K., and Morel, F. M. M.: Zinc availability and alkaline phosphatase activity in Emiliania huxleyi: Implications for Zn-P co-limitation in the ocean, Limnology and Oceanography, 51, 299–309, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2006.51.1.0299, 2006.

Sofen, L. E., Antipova, O. A., Ellwood, M. J., Gilbert, N. E., LeCleir, G. R., Lohan, M. C., Mahaffey, C., Mann, E. L., Ohnemus, D. C., Wilhelm, S. W., and Twining, B. S.: Trace metal contents of autotrophic flagellates from contrasting open-ocean ecosystems, Limnology and Oceanography Letters, 7, 354–362, https://doi.org/10.1002/lol2.10258, 2022.

Sunda, W. G. and Huntsman, S. A.: Cobalt and zinc interreplacement in marine phytoplankton: Biological and geochemical implications, Limnology and Oceanography, 40, 1404–1417, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1995.40.8.1404, 1995.

Timmermans, K. R., Snoek, J., Gerringa, L. J. A., Zondervan, I., and de Baar, H. J. W.: Not all eukaryotic algae can replace zinc with cobalt: Chaetoceros calcitrans (Bacillariophyceae) versus Emiliania huxleyi (Prymnesiophyceae), Limnology and Oceanography, 46, 699–703, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2001.46.3.0699, 2001.

Wiśniewski, J. R. and Rakus, D.: Quantitative analysis of the Escherichia coli proteome, Data Brief, 1, 7–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2014.08.004, 2014.

Wisniewski Jakuba, R., Moffett, J. W., and Dyhrman, S. T.: Evidence for the linked biogeochemical cycling of zinc, cobalt, and phosphorus in the western North Atlantic Ocean, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 22, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GB003119, 2008.

Wojciechowski, C. L., Cardia, J. P., and Kantrowitz, E. R. Alkaline phosphatase from the hyperthermophilic bacterium T. maritima requires cobalt for activity Protein Science, 11, 903–911, 2022.

Wu, J.-R., Shien, J.-H., Shieh, H. K., Hu, C.-C., Gong, S.-R., Chen, L.-Y., and Chang, P.-C.: Cloning of the gene and characterization of the enzymatic properties of the monomeric alkaline phosphatase (PhoX) from Pasteurella multocida strain X-73, FEMS Microbiology Letters, 267, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00542.x, 2007.

Wurl, O., Zimmer, L., and Cutter, G. A.: Arsenic and phosphorus biogeochemistry in the ocean: Arsenic species as proxies for P-limitation, Limnology and Oceanography, 58, 729–740, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2013.58.2.0729, 2013.

Xu, Y., Tang, D., Shaked, Y., and Morel, F. M. M.: Zinc, cadmium, and cobalt interreplacement and relative use efficiencies in the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi, Limnology and Oceanography, 52, 2294–2305, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2007.52.5.2294, 2007.

Yee, D. and Morel, F. M. M.: In vivo substitution of zinc by cobalt in carbonic anhydrase of a marine diatom, Limnology and Oceanography, 41, 573–577, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1996.41.3.0573, 1996.

Yong, S. C., Roversi, P., Lillington, J., Rodriguez, F., Krehenbrink, M., Zeldin, O. B., Garman, E. F., Lea, S. M., and Berks, B. C.: A complex iron-calcium cofactor catalyzing phosphotransfer chemistry, Science (New York, N.Y.), 345, 1170–3, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254237, 2014.

Young, C. L. and Ingall, E. D.: Marine Dissolved Organic Phosphorus Composition: Insights from Samples Recovered Using Combined Electrodialysis/Reverse Osmosis, Aquat. Geochem., 16, 563–574, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10498-009-9087-y, 2010.

Zhang, B., VerBerkmoes, N. C., Langston, M. A., Uberbacher, E., Hettich, R. L., and Samatova, N. F.: Detecting differential and correlated protein expression in label-free shotgun proteomics, Journal of Proteome Research, 5, 2909–2918, https://doi.org/10.1021/pr0600273, 2006.