the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

A new tropical savanna PFT, variable root growth and fire improve Cerrado vegetation dynamics simulations in a Dynamic Global Vegetation Model

Sarah Bereswill

Werner von Bloh

Maik Billing

Boris Sakschewski

Luke Oberhagemann

Kirsten Thonicke

Mercedes M. C. Bustamante

The Cerrado, South America's second largest biome, has been historically underrepresented in Dynamic Global Vegetation Models (DGVMs). Therefore, this study introduces a novel Plant Functional Type (PFT) tailored to the Cerrado biome into the DGVM LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE. The parametrization of the new PFT, called a Tropical Broadleaved Savanna tree (TrBS), integrates key ecological traits of Cerrado trees, including specific allometric relationships, wood density, specific leaf area (SLA), deep-rooting strategies, and fire-adaptive characteristics. The inclusion of TrBS in LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE led to notable improvements in simulated vegetation distribution. TrBS became dominant across Brazil's savanna regions, particularly in the Cerrado and Pantanal. The model also better reproduced the above- and belowground biomass patterns, accurately reflecting the “inverted forest” structure of the Cerrado, characterized by a substantial investment in root systems. Moreover, the presence of TrBS improved the simulation of fire dynamics, increasing estimates of burned area and yielding seasonal fire patterns more consistent with observational data. Model validation confirmed the enhanced performance of the model with the new PFT in capturing vegetation structure and fire regimes in Brazil. Additionally, a global-scale test demonstrated reasonable alignment between the simulated and observed global distribution of savannas. In summary, the integration of the TrBS PFT marks a critical advancement for LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE, offering a more robust framework for investigating the interaction of above- with belowground ecological processes, fire disturbance and the impacts of climate change across the Cerrado and other tropical savanna ecosystems that together account for approximately 30 % of the primary production of all terrestrial vegetation.

- Article

(6681 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1747 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Brazil spans over 850 million ha, from approximately 5° N to 35° S, and hosts diverse climatic conditions, from subtropical and semi-arid to tropical wet environments (IBGE, 2024; Table S1). Within this context, the Cerrado is recognized as the world's most biodiverse savanna and the second-largest vegetation formation in South America, covering about 23 % of Brazil (∼ 2 million km2), mainly in the central region (Myers et al., 2000; IBGE, 2024). The biome provides vital ecosystem services, including carbon storage, climate regulation, and water resources for major river basins (Sano et al., 2019; Schüler and Bustamante, 2022). Despite its global importance, the Cerrado faces severe threats from deforestation driven by agricultural expansion and from climate change, which is intensifying droughts and altering fire regimes, thereby accelerating biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation (Strassburg et al., 2017; Gomes et al., 2020b; Rodrigues et al., 2022).

Climate change impacts in Brazil are already evident. A study by INPE to the First Biennial Transparency Report (MCTI, 2024) reveals an increase of approximately 20 % in the number of consecutive dry days in Brazil in recent decades, particularly in the North, Northeast, and Central regions of the country. Similarly, Feron et al. (2024) demonstrated an increase in the frequency of compound climate events involving heat, drought, and high fire risk in key regions of South America, including the Amazon. A significant increase in maximum and minimum temperatures was also observed in the Brazilian Cerrado between 1961 and 2019, along with a reduction in relative humidity (Hofmann et al., 2021).

In this context, vegetation modeling emerges as an essential tool for understanding and predicting the Cerrado's responses to these pressures. Dynamic Global Vegetation Models (DGVMs), such as the Lund-Potsdam-Jena managed Land model (LPJmL), aim to simulate changes in vegetation, fire, water and carbon fluxes depending on climate and land use (Cramer et al., 2001; Thonicke et al., 2010; Baudena et al., 2015; Moncrieff et al., 2016; Schaphoff et al., 2018; Drüke et al., 2019; Martens et al., 2021). In order to reduce complexity, common DGVMs classify vegetation into so-called Plant Functional Types (PFTs), which are groups of plants that show similar responses to external drivers and resemble their ecological function. PFTs are, in general, distinguished by their allometry, growth form, phenology and photosynthetic strategy (Wullschleger et al., 2014). Parameterization of PFTs should therefore capture the most important characteristics of certain vegetation types while balancing complexity.

Specifically in savannas, vegetation is often characterized by small trees and shrubs that grow deep roots and are well adapted to fire and drought, all of which distinguish them from the trees in moist and seasonal tropical forests (Ratnam et al., 2011). However, many DGVMs, including LPJmL, lack a dedicated savanna PFT, leading to significant inconsistencies in model projections (Foley et al., 1996; Hughes et al., 2006; Clark et al., 2011; Neilson, 2015; Drüke; et al., 2019). This omission often results in the underestimation of savanna vegetation extent and fire occurrences, while overestimating above-ground biomass and the extent of tall tropical forest formations, as demonstrated in simulations for South America (Cramer et al., 2001; Drüke et al., 2019), or a depiction of savanna vegetation as tropical grasslands which do not encompass the coexistence of grasses, shrubs and trees. DGVMs are, nevertheless, widely used to simulate future transitions between the Amazon and the Cerrado biomes, often predicting an abrupt shift from forest to grassland under climate change (Malhi et al., 2009; Swann et al., 2015). However, this oversimplification neglects the intricate ecological gradient that spans diverse vegetation types, from open forests to woody savannas with varying tree cover densities.

This lack of precision in modeling has broader implications for understanding the Cerrado's role in climate mitigation and adaptation, including nature restoration. For example, restoring the entire 20 million hectares of the identified priority areas for restoration in the Cerrado could remove up to 1.77 million t of carbon from the atmosphere (Schüler and Bustamante, 2022). Beyond carbon sequestration, savannas play a crucial role in preserving water resources and biodiversity, acting as natural buffers against climate change and enhancing ecosystem resilience (Oliver et al., 2015; Salazar et al., 2016; Syktus and McAlpine, 2016; Bustamante et al., 2019). With its highly seasonal climate and diverse mosaic of grasslands, savannas, and forest formations, the Cerrado is particularly significant for mitigating and adapting to climate change (Ribeiro and Walter, 2008; Bustamante et al., 2019; Schüler and Bustamante, 2022). Accurately representing savanna-type vegetation in DGVMs will not only improve projections of the Cerrado's vulnerability to climate change but also help identify high-risk areas and guide the development of effective conservation, restoration, and management strategies. For instance, improved models, acknowledging savanna-specific characteristics, could inform studies investigating biome transitions and ecological tipping points, fire management measures, support agricultural adaptation, and optimize water resource management, ensuring the Cerrado's resilience in the face of environmental challenges.

We therefore introduce a new Cerrado specific PFT which we call “Tropical Broadleaved Savanna tree” (TrBS) that entails the biome's unique characteristics into a state-of-the-art version of the LPJmL model (LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE). LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE explicitly simulates variable tree rooting strategies (Sakschewski et al., 2021) and employs the prossed-based fire model SPITFIRE (Thonicke et al., 2010; Oberhagemann et al., 2025), while being based on the latest LPJmL version (LPJmL 5.7; Wirth et al., 2024). In this study, we test our new approach by modeling the Potential Natural Vegetation (PNV) distribution for the entire Brazil and validate our results against observational datasets. This model improvement provides a robust basis for studies exploring the impact of climate change on vegetation dynamics in the Cerrado region. This model is expected to show significant improvements in biomass estimate, vegetation type distributions, and fire dynamics in tropical regions.

2.1 Study region

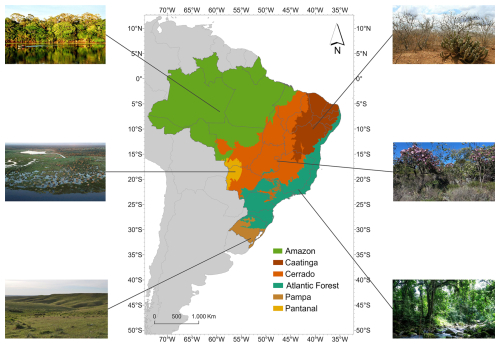

Our study region encompasses all of the Brazilian territory, focusing on the distribution of its six biomes, with special attention to the Cerrado biome. Because of its central position, the Cerrado has ecotones with four of the other five Brazilian biomes: Amazon, Caatinga, Atlantic Forest and Pantanal (Fig. 1).

Recognized as both a savanna and a global biodiversity hotspot, Cerrado's seasonal precipitation regime is closely tied to the South American Monsoon System (Myers at al., 2000; Grimm et al., 2005). According to the Köppen–Geiger classification, the region's climate is predominantly tropical savanna (Aw) with a rainy season from October to April and a dry season from May to September (Peel et al., 2007; Oliveira et al., 2021). Annual rainfall ranges from 600 to 2000 mm, with the highest averages near the Amazon border and the lowest near the Caatinga, and the mean annual temperature is 20.1 °C (Sano et al., 2019).

Figure 1Map representing the distribution of Brazilian biomes according to IBGE (2024) and photos showing their general appearances. Amazon photo by Andre Deak, Pantanal photo by Leandro de Almeida Luciano, Pampa photo by Ilsi Boldrini, Caatinga photo by Matheus Andrietta, Cerrado photo by Jéssica Schüler, and Atlantic Forest photo by Tânia Rego.

Historically, the biome is subject to periodic fires, especially in the grassland and savanna formations, highly influencing the evolution of its vegetation (Simon et al., 2009; Simon and Pennington, 2012). Currently, fires predominantly occur at the end of the dry season, during September and October (Gomes et al., 2020a; MapBiomas Fogo, 2024). The vegetation in the Cerrado can be classified into three main vegetation formations: Forests, Savannas and Grasslands. Forest formations predominantly consist of trees forming a continuous canopy, typically found on deeper soils (Ribeiro and Walter, 2008). Savanna formations are defined by the presence of both arboreal and herbaceous-shrub strata with a canopy cover ranging from 5 % to 70 % and tree heights reaching 8 m on average (Ribeiro and Walter 2008). Finally, grassland formations consist of shrubs and sub-shrubs intermixed with herbaceous strata (Ribeiro and Walter, 2008).

2.2 Model description

The LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE model is a fire-enabled DGVM that integrates the latest version of the DGVM LPJmL (LPJmL 5.7, Wirth et al., 2024) with the most recent improvements of the SPITFIRE fire regime model (Thonicke et al., 2010; Oberhagemann et al., 2025), together with the variable-roots (VR) developed by Sakschewski et al. (2021). This model framework enables the simulation of global vegetation dynamics, including the influence of fire disturbance (Schaphoff et al., 2018; Drüke et al., 2019).

LPJmL simulates the growth and productivity of both natural and managed vegetation, considering water, carbon, and energy fluxes, and represents vegetation through PFTs (Schaphoff et al., 2018). The model accounts for factors such as climate, soil, water, and nutrient availability to simulate the distribution, biomass, and productivity of PFTs, and has been validated against observational data on productivity, biomass, evapotranspiration and PFT distribution on the global scale (Schaphoff et al., 2018). We briefly outline only the most important features of the LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE model version, while referring to Schaphoff et al. (2018) for the general LPJmL model description.

Variable roots. In the original LPJmL model, a PFT-specific shape parameter β defines tree rooting depth and fine root biomass distribution (Jackson et al., 1996). To better reflect the diversity of rooting strategies of tropical trees, Sakschewski et al. (2021) introduced a range of possible rooting strategies (shallow to deep rooted trees) per PFT, that can coexist or outcompete each other. Unless constrained physically by soil depth or by available resources, actual rooting depth is scaled with tree height via a logistic root growth function, and new carbon pools (root sapwood and heartwood) represent the plant's investment in growing coarse roots (Sakschewski et al., 2021). A long-term selection of the best suited rooting strategies amongst each PFT is mediated by a modified tree establishment approach, where the most successful rooting strategies can produce more saplings.

Water-stress mortality. Tree mortality in LPJmL depends on tree longevity, growth efficiency and heat stress (Schaphoff et al., 2018). In this study, a new mortality component reflecting mortality risk due to water stress has been included. This newly integrated water stress mortality depends on tree phenology (“phen”) (Forkel et al., 2014, applied in Schaphoff et al., 2018), leaf senescence due to water stress (phenwater) and PFT-specific parameters representing water stress resistance (cres) and sensitivity to drought (csens).

csens is a PFT-specific parameter that determines the overall sensitivity to drought stress. Phen represents the actual phenological state of a tree, ranging from 0 (no leaf cover) to 1 (full leaf cover). This term accounts for the fact that trees with lower phenology (i.e., more dormant trees) experience reduced water stress mortality. The expression (1−phenwater) represents the intensity of leaf senescence due to low water availability (Forkel et al., 2014), indicating that periods of reduced water availability lead to higher drought-induced mortality. cres defines a threshold below which drought-induced leaf senescence does not significantly impact tree survival.

This model refinement allows for a more accurate representation of PFT-specific sensitivity to water stress. Coupled with the variable rooting scheme, LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE allows trees to optimize the trade-off between carbon investment in deep roots and aboveground growth, providing a survival advantage under drought conditions. The PFT-specific parameters are found in Table 1.

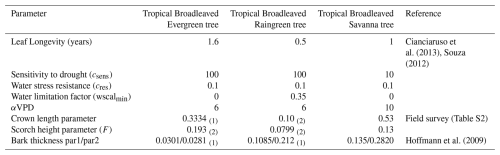

SPITFIRE is a process-based fire model that simulates wildfire occurrence, spread, and behavior, while considering fuel availability, fuel composition and weather conditions to simulate ignitions, rate of spread and flame intensity (Thonicke et al., 2010). By coupling SPITFIRE into LPJmL-VR (LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE), SPITFIRE can simulate the influence of fire on vegetation dynamics. Vegetation properties simulated by LPJmL-VR, such as PFT composition and litter fuel moisture, determine the simulation of fire spread and intensity which in turn influence post-fire vegetation conditions. SPITFIRE considers both human-induced and natural ignitions, with the likelihood of these ignitions developing into fires depending on the fire danger index of the modelled grid cell. Fires then spread depending on factors such as dead and live fuel composition, wind speed, and fuel moisture. We adopted the VPD (water vapor pressure deficit)-dependent calculation of the fire danger index (Drüke et al., 2019; Gomes et al., 2020a) and the most recent updates to the fire spread functions (Oberhagemann et al., 2025). Both the fire danger index and rate of spread calculations include PFT-specific parameters that reflect different vegetation related properties that affect ignition, fire duration and propagation. Fire-related tree mortality is calculated considering PFT specific bark thickness (influencing cambial damage) and scorch height (influencing crown mortality). Furthermore, with the recent updates, SPITFIRE allows for multi-day fires and considers moisture of the live grass share. SPITFIRE feeds back to the vegetation components by calculating fire effects on the vegetation, such as fuel combustion and post-fire tree mortality (Drüke et al., 2019; Oberhagemann et al., 2025).

2.3 Parameterization of a new Savanna tree PFT

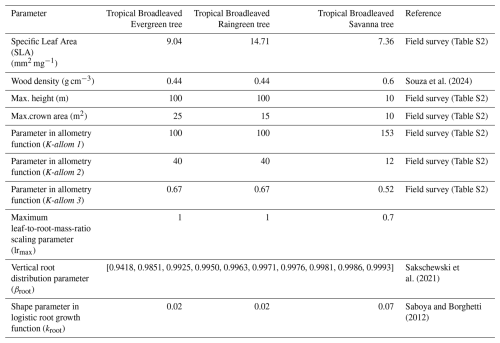

The Cerrado trees exhibit considerable morphological and physiological differences compared to other tropical forest trees growing in closed canopy and wet environments. In LPJmL, these forests are represented by the Tropical Broadleaved Evergreen Tree PFT (TrBE), reflecting the Amazon and the Atlantic rainforests, and by the Tropical Broadleaved Raingreen Tree PFT (TrBR), representing seasonal closed forests. In contrast, Cerrado vegetation is shaped by allometric relationships, and traits such as wood density, specific leaf area (SLA), rooting depth, and bark thickness, which together create a distinctive vegetation structure and functioning highly adapted to seasonal drought and fire occurrence. To incorporate these characteristics into the LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE model, we used a combination of literature data and field observations to derive and calibrate the relevant parameters for the new Tropical Broadleaved Savanna tree (TrBS) parametrization. A summary of all parameters and data sources used is provided in Tables 1 and 2, with detailed explanations below.

2.3.1 Allometry and growth form

The tree allometry is defined through a diameter distribution that follows an asymptotic pattern, where height increases at a slower rate as diameter grows larger, with most trees remaining under 10 m in height (Fig. S2A and C). A similar trend is observed in the relationship between diameter and crown area: trees initially grow in diameter, subsequently expanding their crown until crown growth reaches a plateau (Fig. S2B and D). This observed growth pattern is implemented by allometric relationships using PFT-specific allometric parameters within the LPJmL model (Schaphoff et al., 2018; Eqs. S1, S2 in the Supplement). To ensure an accurate representation of TrBS's tree growth, we analyzed field data to estimate maximum height, maximum crown area, and their relationship with stem diameter (Table S2 in the Supplement). Using these field measurements, we derived the allometric constant values that best aligned with the observed data, by fitting the allometric equations to the data (Fig. S2). Details about site location, data collected, and their references can be found on Table S2.

Despite variations of wood density and SLA due to factors such as soil quality, temperature, and water availability, trees in more arid environments typically develop denser wood with lower SLA values (indicating thicker leaves), an adaptation to water scarcity and mechanical stress (Scholz et al., 2008; Terra et al., 2018; Souza et al., 2024). While we based our wood density value on literature (Souza et al., 2024), the SLA values used in the development of TrBS PFT were estimated from field data collected from 71 individuals of 26 species (Tables 1, S2).

Table 1Allometry, drought mortality and rooting parameters used to define the new Tropical Broadleaved Savanna Tree (TrBS) PFT, along with the corresponding values for the Tropical Broadleaved Evergreen Tree (TrBE), and Tropical Broadleaved Raingreen Tree (TrBR). References cited apply exclusively to TrBS PFT. Details about the field survey data are available on Table S2. Additional information on TrBE and TrBR parameters, as well as parameters not included in this table, can be found in Schaphoff et al. (2018).

2.3.2 Root growth and belowground carbon allocation

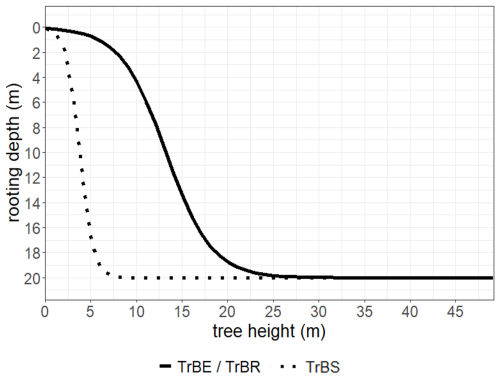

Rooting depth is a crucial adaptation for the Cerrado species, enabling access to deep water reserves during prolonged dry periods (Oliveira et al., 2005; Tumber-Dávila et al., 2022). Due to its high investment in belowground structures, the Cerrado is often referred to as an “upside-down forest”, storing approximately five times more carbon below-ground (in roots and as soil carbon) than above-ground (Terra et al., 2023). While deep roots are a well-documented feature of the Cerrado plants, rooting strategies vary widely among species. To try to reflect this diversity in rooting strategies in LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE we allowed for 10 different root distributions (βroot parameter) per PFT. We chose the same range of βroot values for TrBS PFT as for the other PFTs, to allow a spectrum of shallow, intermediate and deep rooting strategies to compete. From βroot the depth where 95 % of root biomass are found (D95) can be calculated (see Sakschewski et al., 2021). Studies show that the Cerrado tree seedlings invest more in root growth compared to shoot growth as a strategy to access water deeper in soil during the dry season (Hoffmann et al., 2004; Saboya and Borghetti, 2012). We reflect this by modifying the shape parameter of the logistic root growth function (kroot, Table 1), to allow TrBS to reach deeper rooting depths earlier in their lifecycle (Fig. 2), enhancing the underground competitiveness of these savanna trees. In LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE, carbon allocation to coarse woody roots is represented by separate root sapwood and heartwood carbon pools, introduced in addition to the fine root carbon pool (Sakschewski et al., 2021). Due to the necessary balance between root and stem sapwood investment (Pipe Model approach; Shinozaki et al., 1964), and the relationship between tree height and rooting depth, deep root growth for TrBS saplings represents a trade-off between above- and belowground growth.

The ratio between the leaf and the fine root biomass in the model depends on the model internally calculated water stress index (ω), where more root biomass is built under water stress, and is constrained by the lrmax (maximum leaf-to-root-mass-ratio) scaling parameter (Table 1; Schaphoff et al., 2018). We set lrmax to 0.7 to allow TrBS to invest relatively more into root biomass than the other tropical tree PFTs, where lrmax was set to 1 (Schaphoff et al., 2018).

2.3.3 Phenology

The Cerrado exhibits pronounced precipitation seasonality, which shapes the phenology of its vegetation. Deciduous and semi-deciduous species display leaf dynamics in which leaves shed during the dry season, peaking in July, and sprout during the transition to the rainy season in September (de Camargo et al., 2018). Despite the dominance of deciduous and semi-deciduous species (74 %), the community rarely experiences complete defoliation, retaining at least half of its foliage in most years (de Camargo et al., 2018). This seasonal pattern is also evident in the Leaf Area Index (LAI) of trees. LAI values drop from around 1 in the rainy season to approximately 0.6 on the peak of the dry season (Hoffmann et al., 2005).

The degree of foliation in LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE is given by the phenology status, which is updated daily (ranging from 0 = no leaves to 1 = full leaf cover) and derived by multiplication of four limiting functions, namely a water-limiting (fwater), light-limiting (flight), cold-limiting (fcold) and heat-limiting (fheat) function (Schaphoff et al., 2018; Forkel et al., 2014). The shape parameters of fwater were chosen to reflect a behaviour intermediate between the evergreen and the raingreen PFT (Fig. S3), and thereby reflects the general phenological behaviour of the Cerrado community as explained above; fheat, fcold and flight were set to the same values as for TrBE.

2.3.4 Fire dynamic and vegetation adaptation

Over 10.5 million ha burned in the Cerrado in 2024 (MapBiomas Fogo, 2025), with 98 % of these fires attributed to human activity (Schumacher et al., 2022). At local and landscape scales, fire dynamics are influenced by factors such as fuel availability, ignition sources, topography, and climatic conditions (Gomes et al., 2018). In the Cerrado, fire behavior is closely tied to seasonal cycles and one key factor determining its behavior is the vapor pressure deficit (VPD) (Gomes et al., 2020a; Oliveira et al., 2021). VPD is the measure of the difference between the vapour pressure of the moisture present in the air and the maximum vapour pressure the air can hold, being influenced by temperature and relative humidity. In the Cerrado, the VPD varies seasonally, with average values around 0.3 to 0.7 kPa in the rainy season and 1.4 to 2.0 kPa in the dry season (Cattelan et al., 2024). Higher VPD dehydrates plant biomass, especially from grasses, making it more flammable and susceptible to fire (Gomes et al., 2020a). The VPD affects the rate of spread and intensity of the fire, with higher VPD resulting in faster and more intense fires in a given fuel bed (Gomes et al., 2020a; Oliveira et al., 2021). In LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE, the fire danger index depends on VPD and is scaled via a PFT-specific factor αVPD, where higher values of αVPD increase fire danger. We calibrated αVPD to achieve good agreement between observed and modelled burnt area. A higher αVPD for TrBS than for TrBE and TrBR was chosen, because the fuel produced by the Cerrado trees burns more readily, compared to the fuel dropped by trees in the moist forests (dos Santos et al., 2023).

Because of its fire-prone environment, the Cerrado trees exhibit several adaptations that enable them to survive fire damage. These include belowground organs that promote resprouting after fire, thick bark that insulates and protects internal tissues, robust terminal branches, leaves concentrated at branch tips, and persistent stipules that safeguard apical buds, all minimize fire damage (Simon et al., 2009; Simon and Pennington 2012). Fire-induced tree mortality in LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE results from combined effects of cambial and crown damage (Oberhagemann et al., 2025). PFT-specific parameters for bark thickness were chosen to fit the relationship between stem diameter and bark thickness shown in Hofmann et al. (2009) (Fig. S3; Table 2). Scorch height, the highest point at which flames reach and affect the vegetation, is calculated from fire intensity and a PFT specific scaling factor (F; see Eq. S5), which also depends on tree crown length relative to its height (Thonicke et al., 2010; Oberhagemann et al., 2025). The Cerrado trees have relatively long crowns compared to their total height, with a ratio of 0.53 (Table 2). While this exposes them to crown scorch, the above-mentioned adaptations result in an overall lower mortality risk from crown scorch, and we therefore adjusted the parameter F accordingly (Table 2).

Table 2Fire parameters used to define the new Tropical Broadleaved Savanna Tree (TrBS) PFT, along with the corresponding values for the Tropical Broadleaved Evergreen Tree (TrBE) and Tropical Broadleaved Raingreen Tree (TrBR) PFTs. References cited apply exclusively to TrBS PFT. SPITFIRE parameters for TrBE and TrBR are taken from (1) Thonicke et al. (2010), and (2) Drüke et al. (2019).

2.4 Simulation protocol

To evaluate the performance of the newly implemented TrBS PFT, two simulation runs were conducted: one including TrBS PFT (hereafter “Savanna” simulation) and the other experiment excluding it (hereafter “No Savanna” simulation). Both simulations covered the period from 1901 to 2019, with a 5000-year spin-up phase, and utilized identical environmental input data in a 0.5° horizontal resolution.

The model spin-up was simulated from bare ground using climate input from 1901–1930 (with pre-industrial pCO2=276.59 ppm), which was repeated for 5000 years, to allow carbon pools to reach equilibrium with climate. The transient simulation then ran from 1901 to 2019. For model validation, we analyzed the last 30 years of the transient run. Because we aim to evaluate the establishment and general characteristics of the new TrBS PFT, all simulations were conducted for potential natural vegetation (PNV) only, with no simulation of human land use to focus on geographical distribution of vegetation and fire. While LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE features the latest model updates regarding the nitrogen cycle (von Bloh et al., 2018) and biological nitrogen fixation (Wirth et al., 2024), we switched the nitrogen limitation off as it was beyond the scope for this study.

The LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE model uses daily climate input, including air temperature, precipitation, wind speed, humidity, and long- and shortwave radiation. These datasets were sourced from ISIMIP3a (https://doi.org/10.48364/ISIMIP.664235.2, Büchner and Reyer, 2022), which combines GSWP3 data (1901–1978) and W5E5 data (1979–2019). Atmospheric CO2 concentration data were derived from the TRENDY project (Friedlingstein et al., 2023).

Soil texture data were obtained from the Harmonized World Soil Database (Nachtergaele et al., 2009). Soil depth in LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE was defined using the lower water table depth values provided by the SOIL-WATERGRIDS dataset (Guglielmo et al., 2021).

Ignition sources for the SPITFIRE model are based on population density (Klein Goldewijk et al., 2011) for human ignitions, and lightning occurrence data from the OTL/LIS dataset (Christian et al., 2003) for natural ignitions.

2.5 Model validation

For each of our simulation outputs, we selected appropriate Brazilian or global datasets to validate the modeled results from LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE. All spatial analysis and comparisons between the validation data and model outputs were conducted in R, utilizing the ncdf4, terra, raster and sf packages. The analysis focused on the mean values of the last 30 years of the simulations (1990–2019). Details of each validation dataset are provided below.

2.5.1 Vegetation distribution

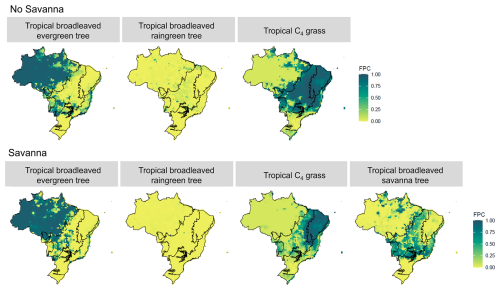

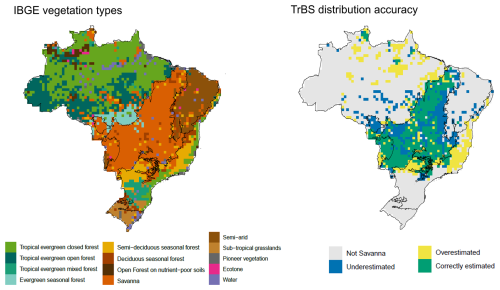

To validate the modeled distribution of the vegetation in Brazil, represented by the foliar projected coverage (FPC) of each PFT, we used Brazil's original vegetation distribution by IBGE (2017). The original IBGE map was a very detailed Shapefile, with specific variation of each major vegetation group, that would have complicated the comparison with the FPC and limited number of PFTs. For this reason, we aggregated the vegetation classes into 13 vegetation types following the attribute table of IBGE's product (Fig. 4). After that, we converted the Shapefile into a raster file using the function rasterize from the terra package in R.

To evaluate the distribution of the new TrBS PFT, as well as the other tropical PFTs, we overlaid the FPC output with the corresponding classification from IBGE. For this comparison, we selected only grid cells where the respective FPC ≥0.3 and matched the class in the IBGE dataset, generating a map that identifies under-, over-, and correctly simulated PFT coverage.

2.5.2 Above- and belowground Biomass, evapotranspiration and productivity

The above- and belowground biomass (AGB and BGB) validation maps were produced by the team from the Fourth National Communication to the United Nations Convention of Climate Change, here referred to as QCN (MCTI, 2020). These maps were produced considering the distribution of Brazil's original vegetation (IBGE, 2017) and estimating AGB and BGB using specific equations and field data that best fit each vegetation type. From these maps we derived a BGB : AGB ratio map to validate the structural characteristics of TrBS PFT. For better comparison, we calculated the Spearman Correlation between the two modeled scenarios of BGB : AGB and the QCN validation using the stats package from R software.

For evapotranspiration (ET) and gross primary productivity (GPP), the mean annual distribution of the last 30 simulation years (1990–2019) were compared to reference datasets (GPP: Carvalhais et al., 2014; ET: ERA5, Hersbach et al., 2020) and evaluated via the Normalized Mean Squared Error (NMSE) and Pearson correlation (as described in Sakschewski et al., 2021).

2.5.3 Burned Area

The Burned Area validation map was produced using the annual burned coverage product from MapBiomas Fogo 3.0 (2024) database. This product gives a 30 m resolution presence-absence map of areas in which fire occurred for a time series from 1985 to 2023. The burned area was calculated from the burned coverage for a 0.5° grid, covering all the Brazilian territory, for each year from 1990 to 2019. Then, from resulting annual burned area maps, we calculated the mean burned area for all selected time series. All calculations and map generation from the MapBiomas dataset were performed using the Google Earth Engine platform.

For the spatial distribution of annual burned area, we created a map of the human land-use fraction based on MapBiomas 9.0 land-use data (MapBiomas 9.0, 2024), using the mean value from 1990 to 2019 (Fig. S5). Since our simulation considers only potential natural vegetation (PNV), we weighted the burned area, in both the validation data and model output, to account for fire occurrences in human-managed land.

The validation of the monthly burned area for the Cerrado biome was conducted using the MapBiomas Fogo 3.0 dataset (2024). The burned area validation was also weighted by the natural land-cover of the corresponding year. This dataset was used to assess the accuracy of the simulated seasonal burned area patterns in the Cerrado. The comparison between the simulated scenarios and the MapBiomas data was evaluated using Normalized Mean Squared Error (NMSE), Willmott's index, R2, and p value statistics from the respective R packages kerntools, hydroGOF and stats (Drüke et al., 2019).

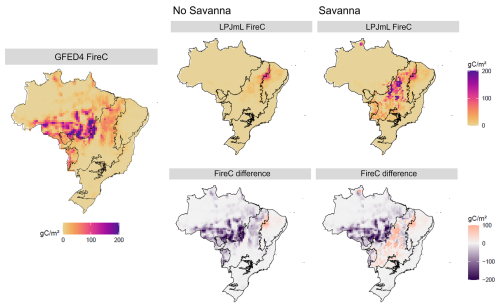

For carbon emission by fire (FireC), our validation is based on the Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED4), which derives its fireC emission maps using its own burned area data (van der Werf et al., 2017). GFED4 combines satellite observations of burned area with biogeochemical modeling to estimate emissions of CO2, CO, CH4, and other trace gases. Given the strong link between burned area and fire emissions, we apply the same land-use fraction weighting approach as for burned area to ensure consistency in our analysis.

3.1 Vegetation distribution

The inclusion of TrBS PFT and the implementation of the Drought Mortality Function have significantly altered the distribution and abundance of key vegetation types across Brazil, particularly the Tropical C4 grasses and TrBE PFTs (see the Supplement for further information). In simulations without TrBS, C4 grass dominates across northeastern and central Brazil, occupying the whole Caatinga biome, most of the Cerrado and northern Atlantic Forest (Fig. 3).

TrBS establishes itself predominantly in the Cerrado and Pantanal biomes, aligning with regions classified as savanna vegetation by IBGE (Figs. 3 and 4). Pockets of TrBS also appear in northern portions of the Amazon biome, where patches of savanna-like vegetation can occur, and Atlantic Forest regions where seasonal forest is present (Figs. 3 and 4). The presence of TrBS results in a contraction of C4 grass, which retreats mostly to the Caatinga biome, where they almost entirely dominate due to Caatinga's dry environment, while grass and savanna vegetation coexist in Pantanal, northern and eastern Cerrado (Fig. 3).

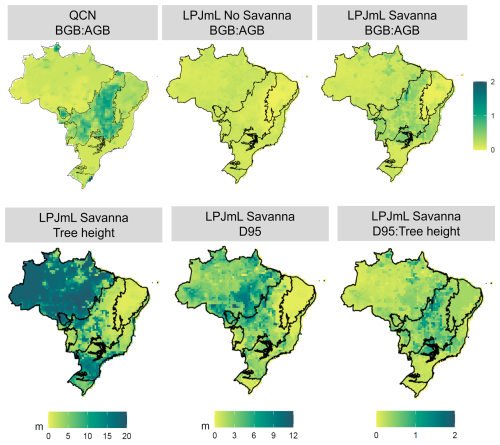

3.2 Above- and belowground Biomass and vegetation structure

The inclusion of TrBS PFT significantly improved the simulated above- and belowground biomass patterns across Brazil compared to simulations without it. By better capturing the characteristic small trees with extensive belowground structures of the Cerrado, TrBS PFT led to an improved representation of the “upside-down forest” in central Brazil (Fig. 5). As a reflection of the distinct allocation strategies of the Cerrado vegetation, the biomass ratio (BGB : AGB) was also clearly improved in the Savanna scenario (Fig. 5). Although the simulated values did not fully match those observed in the QCN validation, as shown by the Spearman correlations (QCN vs. Savanna: 0.27; QCN vs. No Savanna: −0.16), the introduction of TrBS resulted in a more accurate simulation of carbon allocation across Brazil. Both scenarios also showed good performance relative to the reference data for GPP (NMSE <1), with the Savanna model having a marginally lower error compared to the No Savanna (Fig. S10; Table S3). For ET, deviations from the validation dataset are large for both scenarios, with the No Savanna having a slightly better performance (NMSE = 1.56) compared to the Savanna (NMSE = 1.89) (Fig. S10; Table S3).

TrBS PFT also improved the representation of tree height gradients, with tall trees, above 20 m, in the Amazon transitioning to slightly shorter trees in the southern Amazon and reaching approximately 7 m in the Cerrado (Figs. 5, S7). Additionally, the model now captures a gradient in rooting depth (D95), with shallower roots in the Amazon, deepening towards the southern Amazon and Cerrado (Figs. 5, S7). This pattern is further supported by a higher D95 : height ratio in the Cerrado, aligning with the characterization of its vegetation as an “upside-down forest”, where rooting depth can exceed tree height.

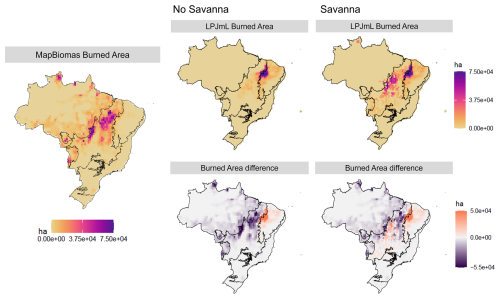

3.3 Fire dynamics

The introduction of TrBS PFT significantly influenced burned area patterns across biomes. LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE generally underestimated burned areas in the “No Savanna” simulation, particularly in the Cerrado and Amazon regions, while overestimating them in the Caatinga (Table 3; Fig. 6). With the inclusion of the new TrBS PFT, the burned area estimates in the Cerrado increased, surpassing the values recorded in the MapBiomas Fogo in central Cerrado, but still underestimating burned area in the northern region of Cerrado and in the Amazon (Fig. 6). Despite these regional discrepancies and given the SPITFIRE improvements applied to both model configurations, the inclusion of TrBS PFT and its adjusted parameterizations led to a clear improvement in the total burned area estimates for Brazil (Table 3).

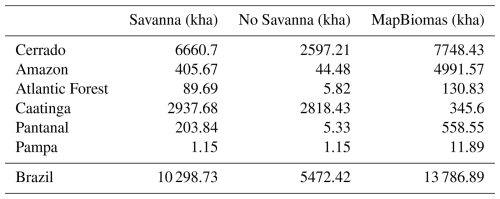

Table 3Total burned area for all Brazilian biomes simulated by LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE for “Savanna”, and “No Savanna” scenarios, and the validation data from MapBiomas Fogo. The values are in Thousand hectares (Kha).

Figure 6LPJmL simulations of burned area in Brazil for “No Savanna” and “Savanna” scenarios (top row), the validation data by MapBiomas Fogo (left), and the respective difference between simulated results and MapBiomas Fogo validation (bottom row).

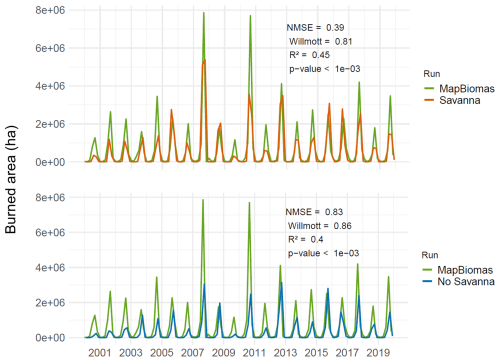

We could also observe an improvement in the seasonal patterns of the burned area in the Cerrado Biome with the incorporation of TrBS PFT (Fig. 7). The Savanna scenario, compared to the MapBiomas data, shows an NMSE of 0.39 with an R2 of 0.45, and a Willmott index of 0.81, indicating that the model has a good fit. The No Savanna scenario has a slightly higher NMSE (0.83) and Willmott index (0.86), and a lower R2 (0.40) compared to MapBiomas, suggesting that removing TrBS reduces the overall model's ability to represent observed seasonal fire patterns.

Figure 7Total monthly burned area, for the Cerrado Biome, from 2000 to 2019 for two LPJmL simulation scenarios: “Savanna” (top) and “No Savanna” (bottom) in comparison with the monthly burned area product from MapBiomas Fogo.

Carbon emission by fire (FireC) patterns reflect directly the burned area patterns (Fig. 8). Overall, the introduction of TrBS did not improve emission estimates in Brazil as most of the emission comes from southeastern Amazon, which has its burned area highly underestimated by our model. In the Cerrado, fire-related emissions were overestimated in the Savanna scenario, particularly in the central part of the biome, reflecting the spatial patterns of burned area.

3.4 Extrapolation to the global scale

Since the LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE model will also be run on a global scale in future applications, the parameterization of the new PFT was tested in a global simulation using the same climate input data set as for the Brazilian simulations. Although TrBS PFT was specifically adapted to the Cerrado tree data, we found high agreement in the simulated global savanna distribution compared to a reference dataset (Hengl et al., 2018). The results are shown in Fig. S9.

4.1 Advancing in Savanna Modeling

The introduction of a savanna-specific Plant Functional Type in the LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE model significantly enhances the representation of vegetation and fire dynamics in Brazil. TrBS improved simulations of carbon allocation, particularly below- to aboveground biomass ratio, and better represented fire behavior, especially the temporal dynamics of burned area. Key features of the Cerrado, that also apply to tropical savannas in general, are now well represented: a vegetation that is adapted to seasonal drought environments by accessing water with deep root systems and allocating more resources belowground and can cope with or even depends on regular occurring fires. This update moves the capability of LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE beyond the previous binary classification of tropical rainforests and grasslands, allowing for a more nuanced depiction of ecological transitions, such as the Amazon-Cerrado interface. By incorporating savanna vegetation, the model facilitates more realistic investigations into the future dynamics of these biomes and allows for a more critical evaluation of restoration efforts within this specific vegetation type. A model limited to representing only “forest” and “grasslands” will fail to capture the significance and vulnerabilities inherent in savanna ecosystems like the Cerrado.

Other DGVMs have struggled earlier to accurately depict the savanna biome (Whitley et al., 2017; Baudena et al., 2015), as many of them oversimplify root dynamics, specific phenology and vegetation-fire feedback. In particular, the role of rooting depth, which is often constrained to shallow values in DGVMs, has a significant impact on the competition between forest, savanna vegetation and grasses, as shown by Langan et al. (2017) for South America. The introduction of root growth and rooting depth diversity in the LPJmL model (Sakschewski et al., 2021) can therefore be considered key to improving savanna modeling, as it allows vegetation adaptation to water scarcity, especially when subdividing the PFTs into different rooting strategies. Importantly, the competition for water between savanna trees and grasses can also be better depicted when partitioning of access to water resources is considered (Whitley et al., 2017; Baudena et al., 2015).

We parameterized the savanna tree PFT using field and literature data specific to the Brazilian Cerrado region and achieved a good fit between modelled and observed savanna distribution. Other modeling studies, for example Moncrieff et al. (2016), have encountered challenges to capture the Cerrado extent due to missing processes. Extrapolations of model parametrization that were specifically evaluated for one savanna region, here the Cerrado, often leads to inaccuracies, given the distinct climate, species composition, and fire-vegetation interactions in each of the savanna-type regions (Solbrig et al., 1996; Lehmann et al., 2014; Moncrieff et al., 2016). Nevertheless, to assess the robustness of our parameterization, we conducted a global simulation and found that the parameterization developed for the Brazilian savanna performed well in simulating global tropical savanna distributions (Fig. S9). Future work could also include an assessment to better capture main functional differences between each savanna-type region.

4.2 Challenges in Representing the Cerrado Dynamics

Despite these advancements, several challenges remain in capturing the complex vegetation dynamics of the Cerrado. Although our simulations already produce a mix of savanna trees and grasses in the northern Cerrado, one key issue is achieving a realistic balance and dynamic feedback between tree and grass cover. Achieving a more realistic vegetation structure is challenging with representing tree and shrub individuals as generalized representatives of each PFT, even though differentiations by rooting depth were incorporated in LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE. Building on the knowledge gained in this study a gap-model framework that simulates individual trees and also incorporates trait diversity such as the LPJmL-FIT model (Sakschewski et al., 2015; Thonicke et al., 2020), could offer a more accurate representation of tree-grass coexistence in the near future.

Our analysis focused on depicting the overall distribution and performance of the new savanna PFT across Brazil. A detailed, site specific validation of carbon and water fluxes, the seasonality of leaf cover and productivity might complement the results of this study. In this context, further model refinement could be undertaken, such as implementing shade intolerant PFTs in the model (Ronquim et al., 2003; Lemos-Filho et al., 2010). Additionally, a notable limitation observed in our simulations is the overrepresentation of C4 grasses in the Caatinga biome, which contrasts with the known vegetation characteristics of the region. The Caatinga is a semi-arid biome characterized by diverse vegetation physiognomies, including succulents and small shrub vegetation, with a predominance of seasonal dry tropical forests rather than extensive grasslands (de Queiroz et al., 2017). As discussed for the tree-grass coexistence in the previous paragraph, Caatinga vegetation modeling would benefit from an individual tree approach (as in LPJmL-FIT) rather than the average individual approach of the LPJmL model. Addressing this will be important for improving model realism and its applicability to drier tropical ecosystems, as well as enhancing its performance in representing fire patterns in the region.

Fire impacts on the vegetation are a key process that maintains savannas' open-canopy structure. Our parameterization of the savanna tree PFT resulted in a vegetation type with high flammability, yet is well protected against lethal fire damage. However, resprouting mechanisms, which are crucial for post-fire recovery (Souchie et al., 2017) are not yet implemented explicitly in the vegetation model but would improve the simulation of vegetation recovery. The amount of fuel available for burning is another key area of ongoing model development, as it strongly influences fire spread and intensity. In the most recent SPITFIRE version that we used in this study, the live grass moisture calculation was substantially improved (Oberhagemann et al., 2025), better reflecting seasonal dynamics of fuel availability of grass vegetation. Although the inclusion of the TrBS PFT may improve the representation of vegetation structure and total biomass in the Cerrado, we could not assess whether this translated into an improvement in fuel biomass estimates. In SPITFIRE, leaves and a proportion of sapwood and heartwood from twigs, branches, and trunks are considered to calculate living fuel biomass (Thonicke et al., 2010). QCN products, on the other hand, do not distinguish carbon stored in these specific tree components but only report total above- and belowground biomass; therefore, a direct validation or assessment of fuel biomass improvement resulting from the TrBS implementation was not feasible.

In Savannas, there is often extensive use of fire for land management purposes. Specifically, in the Cerrado, fire in natural areas is associated with the use of fire for deforestation and pasture management, with fire escaping to natural areas, while in areas of mechanized agriculture and planted forests, owners rather protect the areas against fire. In SPITFIRE, however, ignitions are represented solely as a function of population density, and the model does not explicitly capture the diverse fire management regimes common in these regions. This simplification contributes to the underestimation of burned area along the Caatinga border, where expanding deforestation and intensive land management interact with natural fire regimes, as well as in southeastern Amazonia, where large-scale pasture management fires may escape and affect adjacent rainforest (MapBiomas Fogo, 2024; Cano-Crespo et al., 2015). To mitigate this, we weighted both validation data and model outputs by the human land-use fraction from MapBiomas, thereby excluding grid cells with extensive anthropogenic land use from the analysis. Recent attempts to better incorporate anthropogenic fire management into models (Perkins et al., 2024) could enhance Cerrado fire simulations, which is particularly relevant given the increasing pressures on the biome and the ongoing shifts in fire regimes (da Silva Arruda et al., 2024). Nevertheless, even with improved fire–vegetation dynamics, simulations of future trajectories of these dynamics will remain constrained if key vegetation traits, such as deep root water uptake, are not adequately represented (D'Onofrio et al., 2020; Baudena et al., 2015).

The most recent version of LPJmL incorporates the nitrogen cycle (von Bloh et al., 2018), along with mechanisms of biological nitrogen fixation (BNF, Wirth et al., 2024). Soils in the Cerrado are characterized by acidity, high aluminum concentrations, and nutrient scarcity (Bustamante et al., 2006, 2012), requiring vegetation to develop specific adaptations that confer a competitive advantage in these nutrient-poor conditions. Future advancements should leverage these model enhancements to incorporate nitrogen and other nutrient constraints, enhancing ecological realism to specifically address this aspect to the complex ecological interactions.

Beyond the factors already discussed, rootable soil depth significantly influences vegetation dynamics. However, determining the maximum depth roots can physically penetrate is challenging, as they can grow into bedrock and access groundwater, but are also limited by high soil density and low oxygen availability. In our simulations we used the water table depth of Guglielmo et al. (2021)) as a proxy for rootable soil depth, which allows deep rooting over large parts of the Cerrado, in line with observations of deep rooting vegetation. While this method provides reasonably spatial variable maximum rooting depths, LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE does not simulate an actual water table. In reality, deep-rooted trees can tap groundwater, but LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE assumes free drainage, preventing this interaction. Consequently, some areas may experience artificially shallow rooting depths (e.g. Amazonian floodplains) without the benefit of accessing deeper water reserves, a factor that could become important, especially when running future simulations with the model. Considering these aspects in future work, especially global studies, could further improve the representation of belowground competition and resulting spatial vegetation distribution.

The parameterization of the new Tropical Broadleaved Savanna PFT (TrBS) in LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE significantly improves the representation of the Cerrado biome, the second-largest vegetation formation in South America, in terms of belowground vs aboveground competition, vegetation dynamics and fire. By inclusion of variable rooting strategies along with recent process-based fire modeling, and a new drought mortality function, we present a model that is suited to study complex ecological interactions of the sensitive Cerrado biome that are rapidly changing under ongoing climate change. Here, we combined literature and observational data to parameterize the TrBS PFT and to adjust parameters of tree and root allocation functions, among others. Introducing a dedicated vegetation type for tropical savannas and combining with variable rooting strategies will equip DGVMs to make more precise assessments of recovery, reforestation, and regeneration strategies in these unique ecosystems. By refining the modeling of savanna dynamics, this study provides a valuable foundation for improving conservation strategies, land-use planning, and climate mitigation efforts in fire-prone landscapes such as the Cerrado. The introduction of a savanna-specific PFT with deeper rooting depth not only led to a more realistic allocation of carbon belowground but also enabled the model to reproduce the iconic “upside-down forest” structure of the Cerrado. This structural realism also translated into better representation of vegetation distribution, fire regimes, and their seasonal patterns. These results underscore the importance of incorporating trait diversity, particularly rooting strategies, into DGVMs. Building on this progress, future work, such as extending this savanna-specific PFT to individual-based models like LPJmL-FIT, can further enhance our understanding of post-fire recovery dynamics interacting with functional diversity and more clearly distinguish the intrinsic ecological behavior of tropical savannas from that of tropical forests.

The LPJmL-VR-SPITFIRE model is open-source and available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16965740 (Schüler et al., 2025). Field survey data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All other relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors or included in the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-23-95-2026-supplement.

JS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft; SB: Methodology and Software, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft; WvB: Methodology and Software, Writing – review and editing; MB: Methodology and Software, Writing – review and editing; BS: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing; LO: Writing – review and editing; KT: Supervision, Writing – review and editing; MMCB: Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Biogeosciences. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors are grateful to PIK and the Graduate Program in Ecology from UnB for providing the infrastructure and assistance without which this project wouldn't be possible. To all researchers from the Ecosystems in Transition group at PIK and the Ecosystems Ecology Lab at UnB that contributed with suggestions, critiques, points and ideas. Special thanks to the data curators Letícia Gomes (UNEMAT), Beatriz S. Marimon (UNEMAT), Eddie Lenza (UNEMAT), Christopher William Fagg (UnB), Sabrina Miranda (UEG), Isabela Castro (UnB), Waira Machida (UFG), Lucas Costa (UnB) and Felipe Lenti (UnB) for sharing their field data, essential for this work. B.S. is part of the Planetary Boundaries Science Lab's research effort at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK).

Jéssica Schüler acknowledges the funding by the National Coordination for High Level Education and Training (CAPES) through the Internationalization Program (PrInt), grant no. 88887.891863/2023-00. This work was supported by the National Institute of Science and Technology for Climate Change Phase 2 under CNPq grant no. 465501/2014-1, FAPESP grant no. 2014/50848-9 and CAPES grant no. 88881.146050/2017-01. Sarah Bereswill gratefully acknowledges funding by the Conservation International Foundation, grant no. CI-114129. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program grant no. 101003890 (FirEUrisk). The authors gratefully acknowledge the Ministry of Research, Science and Culture (MWFK) of Land Brandenburg for supporting this project by providing resources on the high-performance computer system at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Jéssica Schüler, Kirsten Thonicke and Mercedes Bustamante acknowledge funding from the BMFTR-funded project “Establishment and consolidation of a German-Brazilian research network to investigate Cerrado resilience under climate change (RESCUE-Cerrado)”, grant no. 01DN25021.

This paper was edited by Manuela Balzarolo and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Baudena, M., Dekker, S. C., van Bodegom, P. M., Cuesta, B., Higgins, S. I., Lehsten, V., Reick, C. H., Rietkerk, M., Scheiter, S., Yin, Z., Zavala, M. A., and Brovkin, V.: Forests, savannas, and grasslands: bridging the knowledge gap between ecology and Dynamic Global Vegetation Models, Biogeosciences, 12, 1833–1848, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-12-1833-2015, 2015.

Büchner, M. and Reyer, C. P. O.: ISIMIP3a atmospheric composition input data (v1.2), ISIMIP Repository, https://doi.org/10.48364/ISIMIP.664235.2, 2022.

Bustamante, M., Medina, E., Asner, G., Nardoto, G., and Garcia-Montiel, D.: Nitrogen cycling in tropical and temperate savannas, Biogeochemistry, 79, 209–237, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-006-9006-x, 2006.

Bustamante, M. M. C., Nardoto, G. B., Pinto, A. S., Resende, J. C. F., Takahashi, F. S. C., and Vieira, L. C. G.: Potential impacts of climate change on biogeochemical functioning of Cerrado ecosystems, Braz. J. Biol., 72, 655–671, https://doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842012000400005, 2012.

Bustamante, M. M. C., Silva, J. S., Scariot, A., Sampaio, A. B., Mascia, D. L., Garcia, E., Sano, E., Fernandes, G. W., Durigan, G., Roitman, I., Figueiredo, I., Rodrigues, R. R., Pillar, V. D., de Oliveira, A. O., Malhado, A. C., Alencar, A., Vendramini, A., Padovezi, A., Carrascosa, H., Freitas, J., Siqueira, J. A., Shimbo, J., Generoso, L. G., Tabarelli, M., Biderman, R., de Paiva Salomão, R., Valle, R., Junior, B., and Nobre, C.: Ecological restoration as a strategy for mitigating and adapting to climate change: Lessons and challenges from Brazil, Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Gl., 24, 1249–1270, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-018-9837-5, 2019.

Cano-Crespo, A., Oliveira, P. J. C., Boit, A., Cardoso, M., and Thonicke, K.: Forest edge burning in the Brazilian Amazon promoted by escaping fires from managed pastures, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 120, 2095–2107, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JG002914, 2015.

Carvalhais, N., Forkel, M., Khomik, M., Bellarby, J., Jung, M., Migliavacca, M., Mu, M., Saatchi, S., Santoro, M., Thurner, M., Weber, U., Ahrens, B., Beer, C., Cescatti, A., Randerson, J. T., and Reichstein, M.: Global covariation of carbon turnover times with climate in terrestrial ecosystems, Nature, 51, 213–217, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13731, 2014.

Cattelan, L. G., Mattos, C. R. C., Pamplona, M. B., and Hirota, M.: Mapping Climatic Regions of the Cerrado: General Patterns and Future Change, International Journal of Climatology, 44, 5857–5872, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.8670, 2024.

Christian, H. J., Blakeslee, R. J., Boccippio, D. J., Boeck, W. L., Buechler, D. E., Driscoll, K. T., Goodman, S. J., Hall, J. M., Koshak, W. J., Mach, D. M., and Stewart, M. F.: Global frequency and distribution of lightning as observed from space by the Optical Transient Detector, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 108, ACL 4-1–ACL 4-15, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002347, 2003.

Cianciaruso, M. V., Silva, I. A., Manica, L. T., and Souza, J. P.: Leaf habit does not predict leaf functional traits in cerrado woody species, Basic and Applied Ecology, 14, 404–412, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2013.05.002, 2013.

Clark, D. B., Mercado, L. M., Sitch, S., Jones, C. D., Gedney, N., Best, M. J., Pryor, M., Rooney, G. G., Essery, R. L. H., Blyth, E., Boucher, O., Harding, R. J., Huntingford, C., and Cox, P. M.: The Joint UK Land Environment Simulator (JULES), model description – Part 2: Carbon fluxes and vegetation dynamics, Geoscientific Model Development, 4, 701–722, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-4-701-2011, 2011.

Cramer, W., Bondeau, A., Woodward, F. I., Prentice, I. C., Betts, R. A., Brovkin, V., Cox, P. M., Fisher, V., Foley, J. A., Friend, A. D., Kucharik, C., Lomas, M. R., Ramankutty, N., Sitch, S., Smith, B., White, A., and Young-Molling, C.: Global response of terrestrial ecosystem structure and function to CO2 and climate change: Results from six dynamic global vegetation models, Glob. Change Biol., 7, 357–373, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2001.00383.x, 2001.

da Silva Arruda, V. L., Alencar, A. A. C., de Carvalho Júnior, O. A., de Figueiredo Ribeiro, F., de Arruda, F. V., Conciani, D. E., da Silva, W. V., and Shimbo, J. Z.: Assessing four decades of fire behavior dynamics in the Cerrado biome (1985 to 2022), fire ecol, 20, 64, https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-024-00298-4, 2024.

de Camargo, M. G. G., de Carvalho, G. H., Alberton, B. D. C., Reys, P., and Morellato, L. P. C.: Leafing patterns and leaf exchange strategies of a cerrado woody community, Biotropica, 50, 442–454, https://doi.org/10.1111/btp.12552, 2018.

de Queiroz, L. P., Cardoso, D., Fernandes, M. F., and Moro, M. F: Diversity and Evolution of Flowering Plants of the Caatinga Domain, in: Caatinga, edited by: Silva, J. M. C., Leal, I. R., and Tabarelli, M., Springer-Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68339-3_2, 2017.

D'Onofrio, D., Baudena, M., Lasslop, G., Nieradzik, L. P., Wårlind, D., and von Hardenberg, J.: Linking vegetation-climate-fire relationships in Sub-Saharan Africa to key ecological processes in two dynamic global vegetation models, Fr. Environ. Sci., 8, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2020.00136, 2020.

dos Santos, L. O. F., Machado, N. G., Biudes, M. S., Geli, H. M. E., Querino, C. A. S., Ruhoff, A. L., Ivo, I. O., and Lotufo Neto, N.: Trends in Precipitation and Air Temperature Extremes and Their Relationship with Sea Surface Temperature in the Brazilian Midwest, Atmosphere, 14, 426, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos14030426, 2023.

Drüke, M., Forkel, M., von Bloh, W., Sakschewski, B., Cardoso, M., Bustamante, M., Kurths, J., and Thonicke, K.: Improving the LPJmL4-SPITFIRE vegetation–fire model for South America using satellite data, Geosci. Model Dev., 12, 5029–5054, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-5029-2019, 2019.

Feron, S., Cordero, R. R., Damiani, A., MacDonell, S., Pizarro, J., Goubanova, K., Valenzuela, R., Wang, C., Rester, L., and Beaulieu, A.: South America is becoming warmer, drier, and more flammable, Commun. Earth Environ., 5, 501, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01654-7, 2024.

Foley, J. A., Prentice, I. C., Ramankutty, N., Levis, S., Pollard, D., Sitch, S., and Haxeltine, A.: An integrated biosphere model of land surface processes, terrestrial carbon balance, and vegetation dynamics, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 10, 603–628, https://doi.org/10.1029/96GB02692, 1996.

Forkel, M., Carvalhais, N., Schaphoff, S., v. Bloh, W., Migliavacca, M., Thurner, M., and Thonicke, K.: Identifying environmental controls on vegetation greenness phenology through model–data integration, Biogeosciences, 11, 7025–7050, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-7025-2014, 2014.

Friedlingstein, P., O’Sullivan, M., Jones, M. W., Andrew, R. M., Bakker, D. C. E., Hauck, J., Landschützer, P., Le Quéré, C., Luijkx, I. T., Peters, G. P., Peters, W., Pongratz, J., Schwingshackl, C., Sitch, S., Canadell, J. G., Ciais, P., Jackson, R. B., Alin, S. R., Anthoni, P., Barbero, L., Bates, N. R., Becker, M., Bellouin, N., Decharme, B., Bopp, L., Brasika, I. B. M., Cadule, P., Chamberlain, M. A., Chandra, N., Chau, T.-T.-T., Chevallier, F., Chini, L. P., Cronin, M., Dou, X., Enyo, K., Evans, W., Falk, S., Feely, R. A., Feng, L., Ford, D. J., Gasser, T., Ghattas, J., Gkritzalis, T., Grassi, G., Gregor, L., Gruber, N., Gürses, Ö., Harris, I., Hefner, M., Heinke, J., Houghton, R. A., Hurtt, G. C., Iida, Y., Ilyina, T., Jacobson, A. R., Jain, A., Jarníková, T., Jersild, A., Jiang, F., Jin, Z., Joos, F., Kato, E., Keeling, R. F., Kennedy, D., Klein Goldewijk, K., Knauer, J., Korsbakken, J. I., Körtzinger, A., Lan, X., Lefèvre, N., Li, H., Liu, J., Liu, Z., Ma, L., Marland, G., Mayot, N., McGuire, P. C., McKinley, G. A., Meyer, G., Morgan, E. J., Munro, D. R., Nakaoka, S.-I., Niwa, Y., O’Brien, K. M., Olsen, A., Omar, A. M., Ono, T., Paulsen, M., Pierrot, D., Pocock, K., Poulter, B., Powis, C. M., Rehder, G., Resplandy, L., Robertson, E., Rödenbeck, C., Rosan, T. M., Schwinger, J., Séférian, R., Smallman, T. L., Smith, S. M., Sospedra-Alfonso, R., Sun, Q., Sutton, A. J., Sweeney, C., Takao, S., Tans, P. P., Tian, H., Tilbrook, B., Tsujino, H., Tubiello, F., van der Werf, G. R., van Ooijen, E., Wanninkhof, R., Watanabe, M., Wimart-Rousseau, C., Yang, D., Yang, X., Yuan, W., Yue, X., Zaehle, S., Zeng, J., and Zheng B.: Global Carbon Budget 2023, Earth System Science Data, 15, 5301–5369, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-5301-2023, 2023.

Gomes, L., Miranda, H. S., and Bustamante, M. M. C.: How can we advance the knowledge on the behavior and effects of fire in the Cerrado biome?, Forest Ecol. Manag., 417, 281–290, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.02.032, 2018.

Gomes, L., Miranda, H. S., Silvério, D. V., and Bustamante, M. M. C.: Effects and behaviour of experimental fires in grasslands, savannas, and forests of the Brazilian Cerrado, Forest Ecol. Manag., 458, 117804, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.117804, 2020a.

Gomes, L., Miranda, H. S., Soares-Filho, B., Rodrigues, L., Oliveira, U., and Bustamante, M. M. C.: Responses of plant biomass in the Brazilian savanna to frequent fires, Front. Forest Glob. Change, 3, 507710, https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2020.507710, 2020b.

Grimm, A. M., Vera, C. S., and Mechoso, C. R.: The South American monsoon system, in: The Global Monsoon System: Research and Forecast, WMO/TD 1266, TMRP Rep. 70, 219–238, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/36730348.pdf (last access: 14 February 2025), 2005.

Guglielmo, M., Tang, F. H. M., Pasut, C., and Maggi, F.: SOIL-WATERGRIDS, mapping dynamic changes in soil moisture and depth of water table from 1970 to 2014, Sci. Data, 8, 263, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-01032-4, 2021.

Hengl, T., Walsh, M. G., Sanderman, J., Wheeler, I., Harrison, S. P., and Prentice, I. C.: Global mapping of potential natural vegetation: An assessment of machine learning algorithms for estimating land potential, PeerJ, 6, e5457, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.5457, 2018.

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Hirahara, S., Horányi, A., Muñoz-Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Abdalla, S., Abellan, X., Balsamo, G., Bechtold, P., Biavati, G., Bidlot, J., Bonavita, M., De Chiara, G., Dahlgren, P., Dee, D., Diamantakis, M., Dragani, R., Flemming, J., Forbes, R., Fuentes, M., Geer, A., Haimberger, L., Healy, S., Hogan, R. J., Hólm, E., Janisková, M., Keeley, S., Laloyaux, P., Lopez, P., Lupu, C., Radnoti, G., de Rosnay, P., Rozum, I., Vamborg, F., Villaume, S., and Thépaut, J. N.: The ERA5 global reanalysis, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803, 2020.

Hoffmann, W. A., Orthen, B., and Franco, A. C.: Constraints to seedling success of savanna and forest trees across the savanna-forest boundary, Oecologia, 140, 252–260, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-004-1595-2, 2004.

Hoffmann, W. A., da Silva, E. R., Machado, G. C., Bucci, S. J., Scholz, F. G., Goldstein, G., and Meinzer, F. C.: Seasonal leaf dynamics across a tree density gradient in a Brazilian savanna, Oecologia, 145, 306–315, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-005-0129-x, 2005.

Hoffmann, W. A., Adasme, R., Haridasan, M., T. De Carvalho, M., Geiger, E. L., Pereira, M. A. B., Gotsch, S. G., and Franco, A. C.: Tree topkill, not mortality, governs the dynamics of savanna–forest boundaries under frequent fire in central Brazil, Ecology, 90, 1326–1337, https://doi.org/10.1890/08-0741.1, 2009.

Hofmann, G., Cardoso, M., Alves, R., Weber, E., Barbosa, A., De Toledo, P., Pontual, F., Salles, L., Hasenack, H., Passos Cordeiro, J. L., Aquino, F., and Oliveira, L.: The Brazilian Cerrado is becoming hotter and drier, Glob. Change Biol., 27, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15712, 2021.

Hughes, J. K., Valdes, P. J., and Betts, R.: Dynamics of a global-scale vegetation model, Ecological Modelling, 198, 452–462, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2006.05.020, 2006.

IBGE: Brazilian Vegetation, https://www.ibge.gov.br/en/geosciences/maps/state-maps/19470-brazilian-vegetation.html?=&t=downloads (last access: 7 November 2024), 2017.

IBGE: Biomas e Sistema Costeiro-Marinho do Brasil – PGI, https://www.ibge.gov.br/apps/biomas/#/home (last access: 11 December 2024), 2024.

Jackson, R. B., Canadell, J., Ehleringer, J. R., Mooney, H. A., Sala, O. E., and Schulze, E. D.: A global analysis of root distributions for terrestrial biomes, Oecologia, 108, 389–411, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00333714, 1996.

Klein Goldewijk, K., Beusen, A., Drecht, G., and Vos, M.: The HYDE 3.1 spatially explicit database of human-induced global land-use change over the past 12,000 years, Global Ecol Biogeogr., 20, 73–86, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00587.x, 2011.

Langan, L., Higgins, S. I., and Scheiter, S.: Climate-biomes, pedo-biomes or pyro-biomes: which world view explains the tropical forest–savanna boundary in South America?, J. Biogeogr., 44, 2319–2330, https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.13018, 2017.

Lehmann, C. E. R., Anderson, T. M., Sankaran, M., Higgins, S. I., Archibald, S., Hoffmann, W. A., Hanan, N. P., Williams, R. J., Fensham, R. J., Felfili, J., Hutley, L. B., Ratnam, J., San Jose, J., Montes, R., Franklin, D., Russell-Smith, J., Ryan, C. M., Durigan, G., Hiernaux, P., Haidar, R., Bowman, D. M. J. S., and Bond, W. J.: Savanna vegetation-fire-climate relationships differ among continents, Science, 343, 548–552, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1247355, 2014.

Lemos-Filho, J. P., Barros, C. F. A., Dantas, G. P. M., Dias, L. G., and Mendes, R. S.: Spatial and temporal variability of canopy cover and understory light in a Cerrado of Southern Brazil, Braz. J. Biol., 70, 19–24, https://doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842010000100005, 2010.

Malhi, Y., Aragão, L. E. O. C., Galbraith, D., Huntingford, C., Fisher, R., Zelazowski, P., Sitch, S., McSweeney, C., and Meir, P.:Exploring the likelihood and mechanism of a climate-change-induced dieback of the Amazon rainforest, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 20610–20615, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0804619106, 2009.

MapBiomas 9.0: MapBiomas Uso e Cobertura 9.0, https://brasil.mapbiomas.org/colecoes-mapbiomas/ (last access: 23 January 2025), 2024.

MapBiomas Fogo: MapBiomas Fogo 3.0, https://mapbiomasfogocol3v1.netlify.app/index.html (last access: 11 December 2024), 2024.

MapBiomas Fogo: MapBiomas Fogo 4.0, https://brasil.mapbiomas.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/06/Fact_Fogo_colecao4.pdf (last access: 20 October 2025), 2025.

Martens, C., Hickler, T., Davis-Reddy, C., Engelbrecht, F., Higgins, S. I., Von Maltitz, G. P., Midgley, G. F., Pfeiffer, M., and Scheiter, S.: Large uncertainties in future biome changes in Africa call for flexible climate adaptation strategies, Glob. Change Biol., 27, 340–358, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15390, 2021.

MCTI: Quarto inventário nacional de emissões e remoções antrópicas de gases de efeito estufa setor uso da terra, mudança do uso da terra e florestas, https://repositorio.mcti.gov.br/handle/mctic/4782 (last access: 26 November 2024), 2020.

MCTI: First biennial transparency report of Brazil to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, https://www.gov.br/mcti/pt-br/acompanhe-o-mcti/sirene/publicacoes/relatorios-bienais-de-transparencia-btrs (last access: 15 January 2025), 2024.

Moncrieff, G. R., Scheiter, S., Langan, L., Trabucco, A., and Higgins, S. I.: The future distribution of the savannah biome: model-based and biogeographic contingency, Philos. T. R. Soc. B., 371, 20150311, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0311, 2016.

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B., and Kent, J.: Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities, Nature, 403, 853–858, https://doi.org/10.1038/35002501, 2000.

Nachtergaele, F., Velthuizen, H., Verelst, L., Batjes, N., Dijkshoorn, K., Engelen, V. W. P., Fischer, G., Jones, A., Montanarela, L., Petri, M., Prieler, S., Shi, X., Texeira, E., and Wiberg, D.: The Harmonized World Soil Database, 34, 2009.

Neilson, R. P.: The Making of a Dynamic General Vegetation Model, MC1, in: Global Vegetation Dynamics, American Geophysical Union (AGU), 41–57, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119011705.ch4, 2015.

Oberhagemann, L., Billing, M., von Bloh, W., Drüke, M., Forrest, M., Bowring, S. P. K., Hetzer, J., Ribalaygua Batalla, J., and Thonicke, K.: Sources of uncertainty in the SPITFIRE global fire model: development of LPJmL-SPITFIRE1.9 and directions for future improvements, Geosci. Model Dev., 18, 2021–2050, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-18-2021-2025, 2025.

Oliveira, R. S., Bezerra, L., Davidson, E. A., Pinto, F., Klink, C. A., Nepstad, D. C., and Moreira, A.: Deep root function in soil water dynamics in cerrado savannas of central Brazil, Funct. Ecol., 19, 574–581, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2005.01003.x, 2005.

Oliveira, U., Soares-Filho, B., de Souza Costa, W. L., Gomes, L., Bustamante, M., and Miranda, H.: Modeling fuel loads dynamics and fire spread probability in the Brazilian Cerrado, Forest Ecol. Manag., 482, 118889, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118889, 2021.

Oliver, T. H., Heard, M. S., Isaac, N. J. B., Roy, D. B., Procter, D., Eigenbrod, F., Freckleton, R., Hector, A., Orme, C. D. L., Petchey, O. L., Proença, V., Raffaelli, D., Suttle, K. B., Mace, G. M., Martín-López, B., Woodcock, B. A., and Bullock, J. M: Biodiversity and resilience of ecosystem functions, Trends Ecol. Evol., 30, 673–684, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2015.08.009, 2015.

Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L., and McMahon, T. A.: Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 11, 1633–1644, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007, 2007.

Perkins, O., Kasoar, M., Voulgarakis, A., Smith, C., Mistry, J., and Millington, J. D. A.: A global behavioural model of human fire use and management: WHAM! v1.0, Geosci. Model Dev., 17, 3993–4016, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-17-3993-2024, 2024.

Ratnam, J., Bond, W. J., Fensham, R. J., Hoffmann, W. A., Archibald, S., Lehmann, C. E. R., Anderson, M. T., Higgins, S. I., and Sankaran, M.: When is a `forest' a savanna, and why does it matter?, Global Ecol. Biogeogr., 20, 653–660, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00634.x, 2011.

Ribeiro, J. and Walter, B.: As principais fitofisionomias do bioma Cerrado, in: Cerrado Ecologia e Flora, edited by: Sano, S. M., Almeida, S. P., and Ribeiro, J. F., Brasília, 152–212, http://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/handle/doc/570911 (last access: 26 November 2024), 2008.

Rodrigues, A. A., Macedo, M. N., Silvério, D. V., Maracahipes, L., Coe, M. T., Brando, P. M., Shimbo, J. Z., Rajão, R., Soares-Filho, B., and Bustamante, M. M. C.: Cerrado deforestation threatens regional climate and water availability for agriculture and ecosystems, Glob. Change Biol., 28, 6807–6822, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16386, 2022.

Ronquim, C. C., Prado, C. H. B. de A., and de Paula, N. F.: Growth and photosynthetic capacity in two woody species of cerrado vegetation under different radiation availability, Braz. Arch. Biol. Techn., 46, 243–252, https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-89132003000200016, 2003.

Saboya, P. and Borghetti, F.: Germination, initial growth, and biomass allocation in three native Cerrado species, Braz. J. Bot., 35, 129–135, https://www.scielo.br/j/rbb/a/8dprpjrPHKPHpytdVCBrVQw/?lang=en (last access: 23 January 2025), 2012.

Sakschewski, B., von Bloh, W., Boit, A., Rammig, A., Kattge, J., Poorter, L., Peñuelas, J., and Thonicke, K.: Leaf and stem economics spectra drive diversity of functional plant traits in a dynamic global vegetation model, Glob. Change Biol., 21, 2711–2725, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12870, 2015.

Sakschewski, B., von Bloh, W., Drüke, M., Sörensson, A. A., Ruscica, R., Langerwisch, F., Billing, M., Bereswill, S., Hirota, M., Oliveira, R. S., Heinke, J., and Thonicke, K.: Variable tree rooting strategies are key for modelling the distribution, productivity and evapotranspiration of tropical evergreen forests, Biogeosciences, 18, 4091–4116, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-18-4091-2021, 2021.

Salazar, A., Katzfey, J., Thatcher, M., Syktus, J., Wong, K., and McAlpine, C.: Deforestation changes land–atmosphere interactions across South American biomes, Global Planet. Change, 139, 97–108, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2016.01.004, 2016.

Sano, E. E., Rodrigues, A. A., Martins, E. S., Bettiol, G. M., Bustamante, M. M. C., Bezerra, A. S., Couto, A. F., Vasconcelos, V., Schüler, J., and Bolfe, E. L.: Cerrado ecoregions: A spatial framework to assess and prioritize Brazilian savanna environmental diversity for conservation, J. Environ. Manage., 232, 818–828, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.11.108, 2019.

Schaphoff, S., von Bloh, W., Rammig, A., Thonicke, K., Biemans, H., Forkel, M., Gerten, D., Heinke, J., Jägermeyr, J., Knauer, J., Langerwisch, F., Lucht, W., Müller, C., Rolinski, S., and Waha, K.: LPJmL4 – a dynamic global vegetation model with managed land – Part 1: Model description, Geosci. Model Dev., 11, 1343–1375, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-1343-2018, 2018.

Scholz, F. G., Bucci, S. J., Goldstein, G., Meinzer, F. C., Franco, A. C., and Salazar, A.: Plant- and stand-level variation in biophysical and physiological traits along tree density gradients in the Cerrado, Braz. J. Plant Physiol., 20, 217–232, https://doi.org/10.1590/S1677-04202008000300006, 2008.

Schüler, J. and Bustamante, M. M. C.: Spatial planning for restoration in Cerrado: Balancing the trade-offs between conservation and agriculture, J. Appl. Ecol., 59, 2616–2626, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14262, 2022.

Schüler, J., Bereswill, S., von Bloh, W., Billing, M., Sakschewski, B., Oberhagemann, L., Thonicke, K., and Bustamante, M. M. C.: Model code for LPJmL-5.8.16-VR-SPITFIRE, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16965740, 2025.

Schumacher, V., Setzer, A., Saba, M. M. F., Naccarato, K. P., Mattos, E., and Justino, F.: Characteristics of lightning-caused wildfires in central Brazil in relation to cloud-ground and dry lightning, Agr. Forest Meteorol., 312, 108723, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2021.108723, 2022.

Shinozaki, K., Yoda, K., Hozumi, K., and Kira, T.: A quantitative analysis of plant form-the Pipe Model Theory: II. Further evidence of the theory and its application in forest ecology, Jpn. J. Ecol., 14, 133–139, https://doi.org/10.18960/seitai.14.4_133, 1964.