the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Water vapour dynamics as a key determinant of atmospheric composition and transport mechanisms

Ivan A. Janssens

Oscar Pérez-Priego

Concentrations of any dry-air component (gas i) are often defined with reference to dry air, excluding water vapour. Here it is shown that water vapour is an air component of paramount importance because its sources and sinks dominate those of air. Alone among atmospheric components, water vapor shifts from a trace constituent (practically negligible) to a bulk gas that meaningfully reduces gas i's fraction and abundance within sultry, tropical air. Customary exclusion of humidity when expressing gas concentrations has practical justification, but biases assessments of gas i's content within air. Overwhelmingly dominating surface exchanges, water vapor dynamics (WVD) influences gas i's distributions, concentration gradients, and transport mechanisms, but this has been overlooked due to reliance on gas fractions within dry air. Important implications of this include physical decoupling of leaf gas exchanges under very hot conditions, with extreme humidity inside stomatal pores acting physically to boost transpiration and simultaneously inhibit photosynthesis by suppressing carbon dioxide, consequences that ecology's stomatal conductance modelling framework has not elucidated. We accentuate the environmental significance of WVD and urge quantifying humidity whenever assessing fractional air composition.

- Article

(2150 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Water vapour is often treated as separate from air due to its great variability, leading scientists to commonly quantify atmospheric composition in terms of fractions of dry air (Wallace and Hobbs, 2006). Such exclusion of humidity has practical justifications. For example, it avoids bias in chamber-based assessments of other gases' sources or sinks as a consequence of evaporation (Pérez-Priego et al., 2015). Furthermore, air samples typically are dried before chemical analysis (Steele et al., 1987; Prinn et al., 1990; Keeling and Shertz, 1992; Novelli et al., 1999; Khalil et al., 2002; Tohjima et al., 2005) to prevent condensation and instrument damage. Thereafter, gas i's dry-air fraction is commonly used to describe its distribution, concentration gradients, and thereby diffusive transport, and furthermore to assess its sources and sinks via inverse modelling (Bousquet et al., 1999; Tian et al., 2016). However, such discrimination – excluding water vapour, and often with no accounting – disguises how water vapor dynamics (WVD) influences gas i's abundance and gradients, and thereby obscures the hydrological cycle's role in actuating the mechanisms that transport gas i. Here we argue that water vapour is not apart from air – it is air – and specifically the component that most significantly influences gas abundances and transport dynamics, but these influences are masked by the typical exclusion of humidity when reporting on air composition.

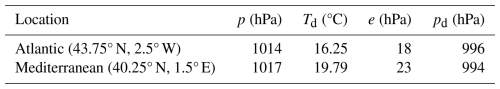

The idea that water vapour is air is clearly demonstrated by ERA5 reanalysis data (Hersbach et al., 2020), selected with intent, that contrast northern Spain's Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts near Bilbao and Barcelona, respectively. At 21:00 UTC on 19 September 2023, sea-level air temperatures at these locations were essentially equal (21.6 °C), but the pressure (p) at the surface was lower in the Atlantic. According to the Ideal Gas Law, this means that between two identical bottles filled with ambient air, one from each coast, the Mediterranean container held more moles of air. Yet, due to higher humidity, it held fewer moles of dry air (lower partial pressure, pd; Table 1). This clearly indicates that water vapour is air.

Table 1Comparison of atmospheric state at two points, respectively with atmospheric pressure (p) and dewpoint temperatures (Td) from ERA5 reanalysis data (Hersbach et al., 2020) for 19 September 2023, at 21:00 UTC. The vapour pressure (e) was calculated from Td using Eq. (10) of Bolton (1980), and the partial pressure of dry air (pd) as the difference p−e.

By dominating air's sources and sinks, water vapour uniquely exerts influence on atmospheric dynamics. Source–sink flows (Owen et al., 1985) are a type of fluid motion whose streamlines begin at sources and end at sinks. Though subtle in the atmosphere, such flows are shown below to contribute to transport, and they are largely governed by WVD. Since evapotranspiration exceeds the combined surface fluxes of all dry-air components by orders of magnitude (Kowalski, 2017), to a very close approximation, air's sources and sinks are those of water vapor. This is reflected in the above example where the Mediterranean's higher sea-level p is due to its greater humidity (Table 1), which in turn is forced by its superior evaporation rate (Lu, 2007). Thus, the substantial Atlantic–Mediterranean pressure gradient in Table 1 arose from WVD, and such gradients drive air motion (Sun et al., 2013). No other gas has comparable dynamical significance.

Net air movement causes non-diffusive transport that is distinct from diffusion in terms of its direction and determinants. At a given point, the orientation of non-diffusive transport – in the direction of fluid flow – is identical for every constituent of air. By contrast, diffusion inherently causes component gases to migrate in different directions. Also, the magnitude of non-diffusive transport depends on the air velocity and the abundance of gas i, but not directly on the concentration gradients that determine gas i's diffusion. However, for certain gas components, their non-diffusive and diffusive transport mechanisms are both influenced by WVD and thereby intimately linked, but this is masked when referencing their abundances to dry air.

Below, we describe how reliance on dry-air fractions that ignore non-negligible water vapour has restricted knowledge regarding gas abundances and transport mechanisms, and thereby important natural processes, at scales ranging from hemispheric (Keeling and Shertz, 1992) down to microscopic (Gaastra, 1959).

Neglect of WVD obscures how it significantly modulates the composition of air across climatic extremes. January's average sea-level isobars of 1008 hPa are found in both the Arctic and tropics (Ahrens, 2000). In surface environments with equal p, the partial pressure of water vapour (e) – tropically above 30 hPa but negligible in Arctic winters (Famiglietti et al., 2018) – regulates pd according to Dalton's law of partial pressures,

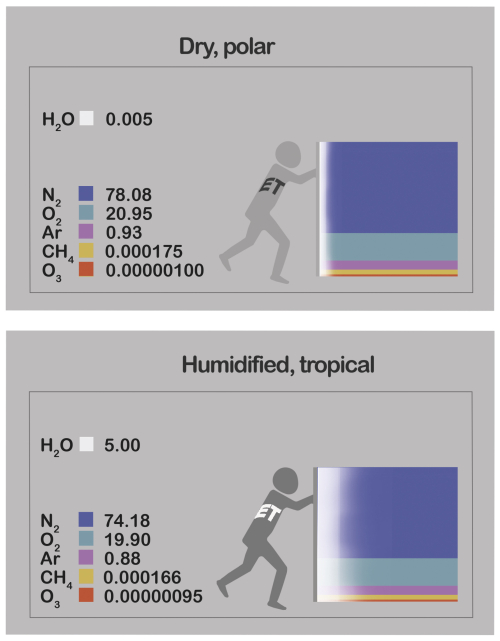

Since pd is likewise the sum of dry air's component partial pressures (∑pi), this zero-sum game describes how extreme humidity suppresses every pi by several percent (Fig. 1). However, this effect is obscured when quantifying gas concentrations in relation to dry air, disguising how every gas i is diluted and displaced by water vapour (Kowalski et al., 2021). Reported gas fractions that ignore humidity (Steele et al., 1987; Prinn et al., 1990; Keeling and Shertz, 1992; Novelli et al., 1999; Khalil et al., 2002; Tohjima et al., 2005) accurately portray dry air and sometimes help to identify gas i's sources and sinks, but do not reflect the true concentrations (i.e., including water vapour) that determine biogeochemical reactions. Also, for many dry-air components, WVD primarily determines the gradients that describe gas i's diffusive transport via flux-gradient relationships such as Fick's 1st law.

Figure 1Partial pressures (kPa) of water vapour (H2O) and selected representatives of dry air – nitrogen (N2), oxygen (O2), argon (Ar), methane (CH4) and ozone (O3) – at 100 kPa pressure, comparing extremes of atmospheric humidity. Summing to 100 in each case, the values also represent molar fractions (χi; %). (A) Dry, polar (Wallace and Hobbs, 2006) versus (B) humidified to extreme sultriness (Raymond et al., 2020). Humidification's agent, evapotranspiration (ET) displaces dry air with water vapour. Illustration by Esther Cardell.

Humidification can reduce pd by up to several percent, with varying degrees of influence on gas i's gradients that delimit three categories of dry-air components (Kowalski and García-Valdecasas Ojeda, 2025), each typified in Fig. 1. Type I gases are scarce and highly reactive, like ozone whose pi varies over orders of magnitude (Robeson and Steyn, 1990) rendering negligible the influence of WVD. Type II gases like methane vary due to both their own sources and sinks (Knief, 2019) and also those of water vapour; methane's reactions modify its pi by a few percent (Steele et al., 1987), comparable in magnitude to forcing by humidity variations. Type III gases are inert relative to their abundance, and include dry air's every bulk component and noble gas; their pi's vary negligibly (far below 1 %) due to their own sources and sinks, but substantially and inversely with humidity due to WVD.

Oxygen (O2) is key example of a Type III gas whose overlooked humidity dependence is biogeochemically significant. Discarding water vapour before chemical analysis (Keeling and Shertz, 1992) confines O2's dry-air molar fraction (ci) within 20.95±0.01 %, i.e. varying globally by less than 100 ppm (Machta and Hughes, 1970). In reality, water vapour's molar fraction () can reach 5 % in extreme sultriness (Raymond et al., 2020), suppressing χi – which better describes the true abundance that determines biochemical or geophysical processes – by up to 10 000 ppm in the case of O2 (Fig. 1). Thus, WVD makes O2 variability orders of magnitude greater than previously supposed, with strong latitudinal and seasonal patterns in each hemisphere (Kowalski and García-Valdecasas Ojeda, 2025).

Geoscience studies that relied on dry-air O2 fractions overlooked this. Meridional, oceanic O2 transport was assessed (Portela et al., 2024) via a model that ignores latitudinal pi gradients when calculating dissolved O2 (Aumont et al., 2015). Global O2 cycle depictions claimed summer air is more aerobic (Gruber et al., 2001; Petsch, 2003), but humidity's strong seasonality makes the opposite true and much more so. Supposing O2 to mirror carbon dioxide (CO2; Gruber et al., 2001), hemispheric O2 cycles were assumed to be decoupled (Keeling et al., 1998). But while O2 reflects CO2 regarding biochemical stoichiometry, the same is not true about physics. Abundances, gradients, and transport mechanisms of CO2, which is a Type II gas, are fundamentally shaped by the carbon cycle and only secondarily influenced by WVD. By contrast, O2 is a Type III gas that moves with dry air, whose cross-equatorial transport must be massive to buffer p against seasonal shifts in e, per Eq. (1). For Type III gases like O2, it is the hydrological cycle that overwhelmingly determines abundances, gradients, and transport mechanisms.

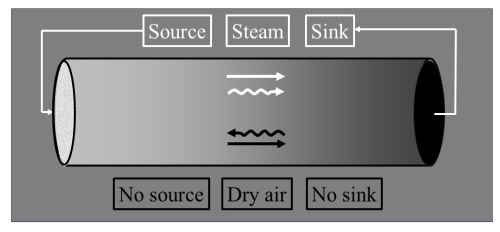

Assumptions that underlie atmospheric transport models are invalidated by their neglect of WVD, wherein humidification dilutes gas i, induces its gradients, and activates its distinct transport mechanisms. Studies of transport that focus on ci (Bousquet et al., 1999) commonly suppose that production and consumption of gas i directly determine its diffusion; these include “top-down” source/sink assessments of greenhouse gases based on inversion models (Tian et al., 2016). However, this overlooks how WVD drives gas i's transport processes, as the following inertia-diffusion thought experiment illustrates. A steady-state tube contains moist air including static, inert dry air and water vapour migrating rightward from its source towards its sink (Fig. 2). This rightward migration yields mass flow – a net rightward air momentum and hence velocity. As noted in Sect. 1, air flows away from its sources and towards its sinks, which in Fig. 2 are exclusively those of water vapour. The resulting air velocity propels rightward, non-diffusive transport of every gas. But for gas i, leftward diffusion counters this since water vapour's source injects molecules that are not gas i, thereby diluting its concentration without directly altering its ci. In Fig. 2, such displacement and dilution by water vapour activate offsetting transport mechanisms (Kowalski et al., 2021), yielding null net transport of gas i via its upstream diffusion. Hence, analyses based solely on ci misrepresent the ongoing physical mechanisms of gas transport, particularly when water vapour exceeds trace concentrations (Kowalski, 2017), with significant implications for accurately representing diffusion.

Figure 2A tube containing moist air, including water vapour (or steam, white) with a source on the left and a sink on the right, and nonreacting dry air (black). Greyscales depict gas fractions. Since air's momentum equals water vapour's, the air velocity is rightward. Both components experience rightward, non-diffusive transport (straight arrows) but they diffuse in opposite directions (curvy arrows). Thus, for dry air, offsetting transport mechanisms actuated by water vapour dynamics yield no net transport.

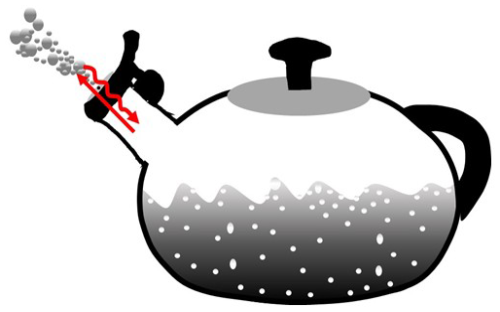

Since WVD dominates atmospheric surface exchanges, the relative magnitudes of water vapour's transport mechanisms depend on its bulk/trace status, as extremes illustrate. At the moist extreme, if water vapour constitutes 99.9999 % of air's mass in Fig. 2, its transport is primarily non-diffusive. In this case, trace dry air (1 mg kg−1) has inertia that impedes air motion only negligibly, and water vapour's transport resembles simple source-to-sink airflow whose magnitude determines that of gas i's upstream diffusion. This case – where air is water vapor – describes gas transport within a geyser, fumarole, or the spout of a whistling tea kettle (Fig. 3; e∼p; pd∼0). At the contrasting extreme, with mere trace water vapour, the fluid's bulk is dry air (pd∼p; e∼0) whose inertia keeps air nearly static, and water vapour transport is essentially diffusive; here, both airflow and dry-air diffusion are tiny, justifying traditional neglect of WVD when assessing gas i's transport mechanisms for Type I and II gases. But this simplification fails for Type II gases when water vapour exceeds trace levels and hydrological forcing of transport mechanisms cannot be ignored, as is common in tropical climates and especially within the micro-scale humid pores that connect leaves to the atmosphere.

Figure 3A whistling tea kettle, containing pure water vapour both above and within liquid water (as steam bubbles). At the boiling point, the water vapour pressure equals the total pressure. Water vapour egress is non-diffusive, with the wet steam jet visible due to external condensation. Inward diffusion of dry-air component gas i (curvy line) is huge, due to an extreme concentration gradient with no gas i inside the boiling kettle, but insufficient to overcome its outbound, non-diffusive transport (straight line).

Perhaps the most significant yet overlooked consequences of WVD occur in the micro-scale environments of plant stomata, where at high temperatures its neglect invalidates foundational ecological models. Inside terrestrial plant leaves, water vapour emission from humidified microscopic cavities beneath stomatal pores (i.e., transpiration; Buckley and Sack, 2019) vastly exceeds photosynthetic CO2 and O2 fluxes. Traditionally, plant physiologists have modelled stomatal gas transport as purely diffusive (Moss and Rawlins, 1963), regulated by stomatal conductance (gs). This assumes proportional CO2 and water vapour flux/gradient ratios based on Graham's law (Jones, 2014) and allows estimating the dry-air molar CO2 fraction (ci) of substomatal cavities, presumed a suitable proxy for the pi of CO2 (Gaastra, 1959), which determines CO2 dissolution via Henry's law and thereby photosynthesis. Such reasoning forms the basis of stomatal optimality theory (Cowan and Farquhar, 1977), which posits that plants adjust gs to optimise carbon gain relative to water loss, thus maximising water-use efficiency (WUE) via proportional regulation of coupled gas exchanges. However, this paradigm neglects both CO2 suppression by humidification (Sect. 2) and non-diffusive transport (Sect. 3), such that the validity of model-laden parameters ci and gs hinges on the assumption that water vapour is a trace gas. As discussed below, such neglect of WVD is inappropriate at very high leaf temperatures (Kowalski, 2025).

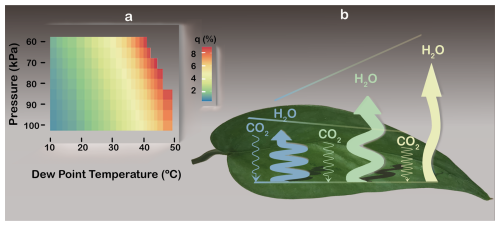

Water vapour's trace or bulk status can be quantified using its mass fraction, known as the specific humidity (q). Because it relates to inertia (Sect. 3), q also defines the non-diffusive fraction of water vapour transport, as described by momentum conservation (Kowalski, 2017; see Appendix A). Inside sub-stomatal cavities, q reaches non-negligible levels over relevant ranges of leaf air's dew point temperature and p (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4The non-diffusive fraction of water vapour (H2O) transport, or specific humidity (q; see Appendix A), and how it decouples leaf gas exchanges. (A) Colour map of stomatal q, calculated from leaf air's dew point temperature and pressure (Petty, 2008). (B) Schematic of CO2 and H2O fluxes decoupling as q increases (blue-yellow transition). Flux magnitudes are represented by arrow widths (H2O far exceeding CO2) and lengths (not to scale) that depict how elevated q boosts H2O egress but retards CO2 ingress, despite increased inward CO2 diffusion. Line sinuosity depicts the degree to which transport is diffusive. Illustration by Esther Cardell.

Diffusion-only stomatal transport models, including ternary approaches (Jarman, 1974; von Caemmerer and Farquhar, 1981), obscure two key consequences of WVD when humidity achieves bulk status. First but least, since q varies inversely with p (Fig. 4A), leaf functioning depends on elevation in contradiction to deductions based on diffusion-only models (Gale, 1972). This may help explain why vascular plants that evolved without stomata thrived only in regions with high-qleaves – in tropical latitudes at very high altitude (Keeley et al., 1984) – when considering the second consequence. To wit, mass flow indiscriminately drives both CO2 and water vapour out of the leaf (Sect. 3), which reduces WUE via independent effects on each gas. Within open stomata at high T when q is high (Fig. 4a) and independently of dilation status, bulk water vapour suppresses the χi of every dry-air component (Fig. 1), including CO2, thereby reducing net assimilation (An) without changing ci; meanwhile, WVD enhances water vapour egress (Fig. 4B) via non-diffusive transport. Evidence of such decoupling – with extreme heat physically restraining An but boosting ET – has frequently been observed across a range of ecosystems and species, as reviewed below.

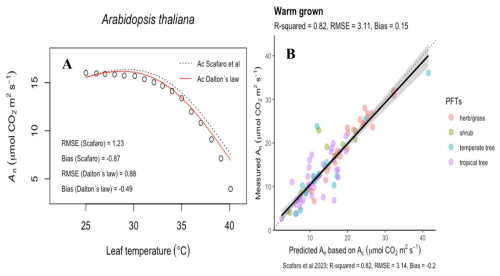

Figure 5Observations, modelled simulations, and the predictability of the leaf temperature response of net CO2 assimilation (An). (A) The An temperature response of Arabidopsis Thaliana. As in Scafaro et al. (2023), points are observations and the curves are the modelled Rubisco carboxylation limited assimilation rates (Ac) with Rubisco deactivation included. Model partial pressures are estimated via the dry-air molar fraction (ci, dashed line) or moist-air molar fraction (χi; solid red line). (B) Predictions of Ac which included Rubisco deactivation but with partial pressures estimated via χi.

With leaf T reaching 50 °C in the Sonoran Desert, 37 % of surveyed species showed increased ET despite declining An (Aparecido et al., 2020). For broadleaf species during heatwaves under well-watered conditions, Diao et al. (2024) found that An decreased with rising heat while ET increased continuously up to a maximum cuvette T of 40 °C. Marchin et al. (2023) found that heatwaves in urban Sydney caused broadleaf evergreen and deciduous species to increase gs but decrease An at air T above 45 °C, independent of plant water access. At the ecosystem scale, Krich et al. (2022) observed similar decoupling in four Australian woodland species based on eddy covariance fluxes, and De Kauwe et al. (2019) demonstrated widespread model–data mismatches during heat extremes across FLUXNET sites. All of these findings are consistent with WVD being a major driving force that physically decouples the fluxes of these gases and reduces WUE in leaves at high T.

To illustrate the significance of WVD's influence on high-temperature leaves, we incorporated the consequences of Dalton's law into the model of Scafaro et al. (2023). These authors showed that biochemistry can limit photosynthesis when leaf T rises above 40 °C; however, by making the substomatal pi of CO2 a fixed fraction of ambient, they effectively bypassed WVD's suppression of dry air within these extremely humid leaf airspaces. To correct this, we multiplied each pi by () in the Scafaro et al. (2023) dataset, which improved the fit of the photosynthetic T response function and reduced bias in Rubisco carboxylation–limited assimilation rates (Fig. 5).

At each spatial scale considered above, disregard of WVD emerges as a substantial shortcoming that results from reliance on dry-air fractions. This highlights the importance of accounting for humidity in assessments of gas i's abundance and transport mechanisms, except perhaps for Type I gases or studies confined to extremely dry environments (e.g., Antarctic science). Fortunately, analytical limitations to determining moist air's composition can be compensated by simple conversion of dry-air fractions to air fractions. The conversion factor, obtained dividing gas i's molar fraction by its dry-air molar fraction and substituting via Eq. (1), is

Figures 1 and 5 quantitatively characterise the effects of this conversion. Mass conservation similarly allows calculating gas i's mass fraction from its dry-air mass fraction (or mixing ratio) and q. Enabling such conversions requires only inexpensive instruments – a barometer and thermo-hygrometer – to monitor the state and humidity of sampled air.

By unlocking the potential of WVD, the steam engine powered the industrial revolution (Nuvolari, 2006) and influenced economic, social and political systems worldwide. Modern environmental science should similarly harness a renewed appreciation of WVD's consequences to advance insight in atmospheric and ecological sciences. The above instances – key examples where its neglect has impeded understanding of the natural world – underline the relevance of quantifying humidity when describing gas concentrations and transport mechanisms. Regarding plant ecology, a novel modelling framework seems necessary to accurately quantify how high temperatures, particularly at altitude, decouple leaf photosynthesis and transpiration.

For most land plants, the gaseous species composing stomatal air have diverse momenta (kg m s−1) including outward water vapour (H2O) and O2, null nitrogen (N2) and argon (Ar), and inward CO2. With the outward velocity as w (m s−1) and the mass as m (kg), air's momentum is the sum of its components' momenta

Dividing each side of Eq. (A1) by some stomatal control volume V yields

where ρ is density (kg m−3) and (wρ)i is the flux density (kg m−2 s−1) of gas i. Since H2O dominates stomatal gas exchange by orders of magnitude (Kowalski, 2017), the flux densities of other gases can be neglected simplifying Eq. (A2) to

which quantifies the net H2O flux density, or evaporative flux density (E; kg m−2 s−1). Dividing this by ρ yields the air velocity

and multiplying this by defines H2O's non-diffusive flux density () as

where (the specific humidity, q) quantifies the non-diffusive fraction of H2O transport, as depicted in Fig. 4.

No data sets were used in this article.

ASK conceived and wrote the first draft of the manuscript, created Figs. 2 and 3, and contracted for figure artwork. IAJ reoriented key sections, notably the abstract and first section, and eliminated much extraneous text. OP-P wrote the first-draft paragraph on leaf ecology, produced Figs. 4A and 5, and remoulded the conclusions. All authors revised the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Andrew S. Kowalski and Oscar Pérez-Priego are funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación project REMEDIO (grant no. PID2021-128463OB-I00). Ivan A. Janssens acknowledges support from ICOS-Flanders (grant no. I00325N). We thank Matilde García-Valdecasas Ojeda for assistance in accessing ERA5 reanalysis data, editor Lutz Merbold for handling and suggesting changes to our manuscript, and Dan Yakir and one anonymous referee for reviewing our submission. We used AI tools to improve paragraph concision.

This research has been supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (grant no. PID2021-128463OB-I00).

This paper was edited by Lutz Merbold and Anja Rammig and reviewed by one anonymous referee.

Ahrens, C. D.: Essentials of Meteorology, Brooks/Cole, Australia, ISBN 10 0534372007, 2000.

Aparecido, L. M. T., Woo, S., Suazo, C., Hultine, K. R., and Blonder, B.: High water use in desert plants exposed to extreme heat, Ecol. Lett., 23, 1189–1200, https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13516, 2020.

Aumont, O., Ethé, C., Tagliabue, A., Bopp, L., and Gehlen, M.: PISCES-v2: an ocean biogeochemical model for carbon and ecosystem studies, Geosci. Model Dev., 8, 2465–2513, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-8-2465-2015, 2015.

Bolton, D.: The computation of equivalent potential temperature, Monthly Weather Rev., 108, 1046–1053, 1980.

Bousquet, P., Ciais, P., Peylin, M., Ramonet, M., and Monfray, M.: Inverse modelling of annual atmospheric CO2 sources and sinks 1. Method and control inversion, J. Geophys. Res., 104, 26161–26178, 1999.

Buckley, T. N. and Sack, L.: The humidity inside leaves and why you should care: implications of unsaturation of leaf intercellular airspaces, Am. J. Bot., 106, 618–621, https://doi.org/10.1002/ajb2.1282, 2019.

Cowan, I. R. and Farquhar, G. D.: Stomatal function in relation to leaf metabolism and environment, Symp. Soc. Exp. Bio., 31, 471–505, 1977.

De Kauwe, M. G., Medlyn, B. E., Pitman, A. J., Drake, J. E., Ukkola, A., Griebel, A., Pendall, E., Prober, S., and Roderick, M.: Examining the evidence for decoupling between photosynthesis and transpiration during heat extremes, Biogeosciences, 16, 903–916, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-16-903-2019, 2019.

Diao, H., Cernusak, L. A., Saurer, M., Gessler, A., Siegwolf, R. T. W., and Lehmann, M. M.: Uncoupling of stomatal conductance and photosynthesis at high temperatures: mechanistic insights from online stable isotope techniques, New Phytol., 241, 2366–2378, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19558, 2024.

Famiglietti, C. A., Fisher, J. B., Halverson, G., and Borbas, B.: Global validation of MODIS near-surface air and dewpoint temperatures, Geophys. Res. Lett., 45, 7772–7780, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL077813, 2018.

Gaastra, P. L.: Photosynthesis of crop plants as influenced by light, carbon dioxide, temperature and stomatal diffusion resistance, edited by: Veenman, H. and Zonen, N. V., doctoral thesis, Wageningen, Netherlands, , 1959.

Gale, J.: Availability of carbon dioxide for photosynthesis at high altitudes: theoretical considerations, Ecol., 149, 78–90, 1972.

Gruber, N., Gloor, M., Fan, S.-M., and Sarmiento, H. L.: Air-sea flux of oxygen estimated from bulk data: Implications For the marine and atmospheric oxygen cycles, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 15, 783–803, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000GB001302, 2001.

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Hirahara, S., Horányi, A., Muñoz-Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Abdalla, S., Abellan, X., Balsamo, G., Hechtold, P., Biavati, G., Bidlot, J., Bonavita, M., De Chiara, G., Dahlgren, P., Dee, D., Diamantakis, M., Dragani, R., Flemming, J., Forbes, R., Fuentes, M., Geer, A., Haimberger, L., Healy, S., Hogan, R. J., Hólm, E., Janisková, M., Keeley, S., Laloyaux, P., Lopez, P., Lupu, C., Radnoti, G., de Rosnay, P., Rozum, I., Vamborg, F., Villaume, S., and Thépaut, J.-N.: The ERA5 global reanalysis, Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc., 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803, 2020.

Jarman, P. D.: The diffusion of carbon dioxide and water vapour through stomata, J. Exp. Bot., 25, 927–936, 1974.

Jones, H. G.: Plants and Microclimate, Cambridge University, Cambridge, UK, ISBN 10 0521279593, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511845727, 2014.

Keeley, J. E., Osmond, C. B., and Raven, J. A.: Stylites, a vascular land plant without stomata absorbs CO2 via its roots, Nature, 310, 695–695, 1984.

Keeling, R. F. and Shertz, S. R.: Seasonal and interannual variations in atmospheric oxygen and implications for the global carbon cycle, Nature, 358, 723–727, https://doi.org/10.1038/358723a0, 1992.

Keeling, R. F., Stephens, B. B., Najjar, R. G., Doney, S. C., Archer, D., and Heimann, M.: Seasonal variations in the atmospheric ratio in relation to the kinetics of air-sea gas exchange, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 12, 141–163, https://doi.org/10.1029/97GB02339, 1998.

Khalil, M. A. K., Rasmussen, R. A., and Shearer, M. J.: Atmospheric nitrous oxide: patterns of global change during recent decades and centuries, Chemosphere, 47, 807–821, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0045-6535(01)00297-1, 2002.

Knief, C.: Diversity of methane-cycling microorganisms in soils and their relation to oxygen, Curr. Issues Mol. Biol., 33, 23–56, https://doi.org/10.21775/cimb.033.023, 2019.

Kowalski, A. S.: The boundary condition for vertical velocity and its interdependence with surface gas exchange, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 8177–8187, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-8177-2017, 2017.

Kowalski, A. S.: An elucidatory model of oxygen's partial pressure inside substomatal cavities, Biogeosciences, 22, 785–789, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-22-785-2025, 2025.

Kowalski, A. S. and García-Valdecasas Ojeda, M.: Humidity-determined distributions of surface oxygen, ESS Open Archive [preprint], https://doi.org/10.22541/essoar.174721854.49630082/v1, 2025.

Kowalski, A. S., Serrano-Ortiz, P., Miranda-García, G., and Fratini, G.: Disentangling turbulent gas diffusion from non-diffusive transport in the boundary layer, Bound.-Lay. Meteorol., 179, 347–367, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-021-00605-5, 2021.

Krich, C., Mahecha, M. D., Migliavacca, M., De Kauwe, M. G., Griebel, A., Runge, J., and Miralles, D. G.: Decoupling between ecosystem photosynthesis and transpiration: A last resort against overheating, Env. Res. Lett., 17, 044013, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac583e, 2022.

Lu, Y.: Global variations in oceanic evaporation (1958–2005): the role of the changing wind speed, J. Clim., 20, 5376–5390, https://doi.org/10.1175/2007JCLI1714.1, 2007.

Machta, L. and Hughes, E.: Atmospheric oxygen in 1967 to 1970, Science 168, 1582–1584, 1970.

Marchin, R., Medlyn, B. E., Tjoelker, M. G., and Ellsworth, D. S.: Decoupling between stomatal conductance and photosynthesis occurs under extreme heat in broadleaf tree species regardless of water access, Global Change Biol., 29, 6319–6335, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16929, 2023.

Moss, D. N. and Rawlins, S. L.: Concentration of carbon dioxide inside leaves, Nature, 197, 1320–1321, 1963.

Novelli, P. C., Lang, P. M., Masarie, K. A., Hurst, D. F., Myers, R., and Elkins, J. W.: Molecular hydrogen in the troposphere: Global distribution and budget, J. Geophys. Res., 104, 30427–30444, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JD900788, 1999.

Nuvolari, A.: The making of water vapour power technology: a study of technical change during the British industrial revolution, J. Econ. Hist., 66, 472–476, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050706220205, 2006.

Owen, J. M., Pincombe, J. R., and Rogers, R. H.: Source-sink flow inside a rotating cylindrical cavity, J. Fluid Mech., 155, 233–265, 1985.

Pérez-Priego, O., López-Ballesteros, A., Sánchez-Cañete, E.P., Serrano-Ortiz, P., Kutzbach, L., Domingo, F., Eugster, W., and Kowalski, A. S.: Analysing uncertainties in the calculation of fluxes using whole-plant chambers: random and systematic errors, Plant Soil, 393, 229–244, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-015-2481-x, 2015.

Petsch, S. T.: The global oxygen cycle, in: Treatise on Geochemistry Volume 8, edited by: Turekian, K. K. and Holland, H. D., Elsevier, Amsterdam, eBook ISBN 9780080548074, 2003.

Petty, G. W.: A first course in atmospheric thermodynamics, Sundog Publishing, Madison, USA, ISBN-10 0-9729033-2-1, 2008.

Portela, E., Kolodziejczyk, N., Gorgues, T., Zika, J., Perruche, C., and Mignot, A.: The ocean's meridional oxygen transport, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 129, e2023JC020259, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JC020259, 2024.

Prinn, R., Cunnold, D., Rasmussen, R., Simmonds, P., Alyea, F., Crawford, A., Fraser, R., and Rosen, R.: Atmospheric emissions and trends of nitrous oxide deduced from 10 years of ALE-GAGE data, J. Geophys. Res., 95, 18369–18385, 1990.

Raymond, C., Matthews, T., and Horton, R. M.: The emergence of heat and humidity too severe for human tolerance, Sci. Adv., 6, eaaw1838, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaw1838, 2020.

Robeson, S. M. and Steyn, D. G.: Evaluation and comparison of statistical forecast models for daily maximum ozone concentrations, Atmos. Env., 24B, 303–312, 1990.

Scafaro, A. P., Posch, B. C., Evans, J. R., Farquhar, G. D., and Atkins, O. K.: Rubisco deactivation and chloroplast electron transport rates co-limit photo-synthesis above optimal leaf temperature in terrestrial plants, Nat. Commun., 14, 2820, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38496-4, 2023.

Steele, L. P., Fraser, P. J., Rasmussen, R. A., Khalil, M. A. K., Conway, T. J., Crawford, A. J., Gammon, R. H., Masarie, K. A., and Thoning, K. W.: The global distribution of methane in the troposphere, J. Atmos. Chem., 5, 125–171, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-3909-7_21, 1987.

Sun, J., Lenschow, D. H., Mahrt, L., and Nappo, C.: The relationships among wind, horizontal pressure gradient, and turbulent momentum transport during CASES-99, J. Atmos. Sci., 70, 3397–3414, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-12-0233.1, 2013.

Tian, H., Lu, C., Ciaias, P., Michalak, A. M., Canadell, J. G., Saikawa, E., Huntzinger, D. N., Gurney, K. R., Sitch, S., Zhang, B., Yang, J., Bousquet, P., Bruhwiler, L., Chen, G., Dlugokencky, E., Friedlingstein, P., Melillo, J., Pan, S., Poulter, B., Prinn, R., Saunois, M., Schwalm, C. R., and Wofsy, S. C.: The terrestrial biosphere as a net source of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, Nature, 531, 225–228, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16946, 2016.

Tohjima, Y., Machida, T., Watai, T., Akama, I., Amari, T., and Moriwaki, Y.: Preparation of gravimetric standards for measurements of atmospheric oxygen and reevaluation of atmospheric oxygen concentration, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 110, D11302, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JD005595, 2005.

von Caemmerer, S. and Farquhar, G. D.: Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas exchange of leaves, Planta, 153, 376–387, 1981.

Wallace, J. M. and Hobbs, P. V.: Atmospheric science: an introductory survey, Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, ISBN 10 012732951X, 2006.

- Abstract

- Water Vapour is Part and Parcel of Air

- Humidity Suppresses Dry Air's Components

- Transport Knowledge Gathers Steam

- Consequences of Bulk Water Vapour within Stomata

- Perspectives and conclusions

- Appendix A: Stomatal Water Vapour Transport's Non-diffusive Fraction is the Specific Humidity (q)

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Water Vapour is Part and Parcel of Air

- Humidity Suppresses Dry Air's Components

- Transport Knowledge Gathers Steam

- Consequences of Bulk Water Vapour within Stomata

- Perspectives and conclusions

- Appendix A: Stomatal Water Vapour Transport's Non-diffusive Fraction is the Specific Humidity (q)

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References