the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Northward shift of boreal tree cover confirmed by satellite record

Min Feng

Joseph O. Sexton

Panshi Wang

Paul M. Montesano

Leonardo Calle

Nuno Carvalhais

Benjamin Poulter

Matthew J. Macander

Michael A. Wulder

Margaret Wooten

William Wagner

Akiko Elders

Saurabh Channan

Christopher S. R. Neigh

The boreal forest has experienced the fastest warming of any forested biome in recent decades. While vegetation–climate models predict a northward migration of boreal tree cover, the long-term studies required to test the hypothesis have been confined to regional analyses, general indices of vegetation productivity, and data calibrated to other ecoregions. Here we report a comprehensive test of the magnitude, direction, and significance of changes in the distribution of the boreal forest based on the longest and highest-resolution time-series of calibrated satellite maps of tree cover to date. From 1985 to 2020, boreal tree cover expanded by 0.844 million km2, a 12 % relative increase since 1985, and shifted northward by 0.29° mean and 0.43° median latitude. Gains were concentrated between 64–68° N and exceeded losses at southern margins, despite stable disturbance rates across most latitudes. Forest age distributions reveal that young stands (up to 36 years) now comprise 15.4 % of forest area and hold 1.1–5.9 Pg of aboveground biomass carbon, with the potential to sequester an additional 2.3–3.8 Pg C if allowed to mature. These findings confirm the northward advance of the boreal forest and implicate the future importance of the region's greening to the global carbon budget.

- Article

(5954 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(4154 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The boreal biome is Earth's most expansive and ecologically intact forest. The region contains 38 ± 3.1 Pg Carbon (C) of above-ground biomass (Neigh et al., 2013) and is underlain by 1672 Pg C, summing to total biomass rivaling the tropics and half of global soil C (Gauthier et al., 2015). Its forested area comprises a third of the global total and accounts for 20.8 % of the total forest carbon (C) sink (Pan et al., 2011, 2024). Boreal tree cover also controls the reflective and thermal balance of solar radiation of the high northern latitudes, posing a positive feedback mechanism for greenhouse atmospheric warming (Betts, 2000; Bonan, 2008; Chen et al., 2018; Randerson et al., 2006).

The boreal region has experienced the fastest climatological warming of any forest biome, with annual surface temperatures increasing more than 1.4 °C over the past century (IPCC, 2014, 2023). Boreal forest dynamics are highly correlated to climate (Elmendorf et al., 2012; Holtmeier and Broll, 2005; Véga and St-Onge, 2009), and increases in vegetation productivity have been observed across the northern high latitudes (Berner and Goetz, 2022). However, regional increases in the frequency and severity of windthrow, fire, insect, and disease events have also been reported (Gauthier et al., 2015; Walker et al., 2019), and a recent analysis by Rotbarth et al. (2023) suggests that southern contraction exceeds northern expansion, yielding net shrinkage of the boreal forest.

While theory predicts a northward shift of the boreal forest, the global net effects of climate and other factors on the density and distribution of its tree cover remain untested hypotheses at the spatial and temporal scale of Landsat, Earth's longest-running record of global, high-resolution satellite imagery. Coupled climate-vegetation models predict a net-northward migration of boreal vegetation due to warming (IPCC, 2018; Scheffer et al., 2012), supporting the dominance of growth processes. Multiple studies (Berner and Goetz, 2022; Sulla-Menashe et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2016; Piao et al., 2020) have reported vegetation “greening” (e.g., Berner and Goetz, 2022) based on spectral indices of plant productivity. However, the ecological effects of trees differ from those of graminoids, shrubs, and other vegetation, and the comparatively low productivity of boreal ecosystems necessitate long-term analyses that have historically been limited to either regional scales or uncalibrated data (Beck et al., 2011; Brice et al., 2020; Taylor et al., 2017; Rotbarth et al., 2023). As a result, the net effect of growth and mortality on the global distribution of boreal tree cover, and the resulting effect on carbon budgets, remain uncertain (Fan et al., 2023).

Here we report a global test of the magnitude and direction of boreal-forest change from 1985 to 2020, as observed through historical satellite records of tree cover calibrated to the boreal biome. We calibrated and expanded a global tree cover dataset (Carroll et al., 2011; Sexton et al., 2013) to 224 026 Landsat images estimating tree cover and its changes over the global extent of the boreal forest and adjacent tundra at annual, 30 m resolution over 36 years (Fig. S1) – the most extensive and highest-resolution record of boreal tree cover to date. This pan-boreal time series was then subjected to trend analysis to estimate and map the historical direction, rate, and significance of change across the region, and the resulting estimates of forest age were used to infer impacts on the region's carbon budget.

2.1 Historical retrieval of tree cover

To improve characterization of boreal forest structure, we calibrated the 250 m resolution, 2000–2020 MODIS Vegetation Continuous Fields (VCF) Tree Cover product (MOD44B Collection 6; Carroll et al., 2011) against a region-wide sample of airborne lidar measurements, stratifying by topographic and bioclimatic covariates (Sects. S2–S3). This boreal-specific calibration improved characterization of tree-cover gradients across the boreal region (Fig. S7), increasing accuracy, decreasing uncertainty, and improving the linear correlation of per-pixel fractional tree cover estimates to reference measurements (Fig. S8). Mean absolute error (MAE) decreased to 11.13 %, root-mean-squared error (RMSE) decreased to 16.44 %, and the coefficient of determination (R2) of the linear model between estimated and measured data increased to 0.60.

The calibrated MODIS VCF estimates were then downscaled to 30 m resolution and extended to 1984–2020 by applying a machine learning model (gradient-boosted regression tree) to Landsat surface reflectance imagery from sensors Thematic Mapper (TM), Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+), and Operational Land Imager (OLI) (Sexton et al., 2013; Sects. S5–S6). A total of 224 026 Landsat scenes across 2189 World Reference System 2 (WRS-2) tiles was used to reconstruct annual tree cover estimates, composited to minimize cloud, snow, and phenological noise. For each pixel-year, the median value of valid observations was retained, resulting in a consistent, high-resolution time series of tree cover estimates (Sect. S7). The residual bias of the Landsat-based estimates relative to the LiDAR reference measurements was slight (∼ 2 %, Sect. S6).

2.2 Tree cover trend analysis

The calibrated, downscaled, and extended tree cover values were then summarized across the region as annual, boreal-wide means and medians to calculate changes over the 36-year study span (Fig. 2). The annual mean and median tree cover were also broken down by latitude to calculate the change rate at each latitudinal degree between 47 to 70° N. Tree cover estimates for 1984 were excluded from the trend analysis due to the poor spatial coverage in the first operational year of Landsat 5 (Sect. S8), and pixels with less than 30 unobscured annual tree cover observations were excluded to minimize unbalanced representation caused by the lapses in the availability of Landsat images, mainly in central and northeast Siberia (Neigh et al., 2013; Sexton et al., 2013).

2.3 Detection of forest change and estimation of age

Following the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, 2002), forest was defined as tree cover exceeding 30 % within each 30 m pixel. The probability of a pixel being forested, p(F), was calculated as the integral of the probability density function of tree cover values exceeding this 30 % threshold (Sect. S9). Using the 36-year time series of annual, 30 m resolution estimates of forest probability (p(F)), forest changes, i.e., gains and losses, were identified by applying a two-sample z-test in a moving kernel centered on transitions across the 50 % threshold of p(F) (Fig. S13).

Pixels with multiple statistically significant transitions during the 1985–2020 period were permitted up to three gain or loss events. Forest changes were classified as “incomplete” if more than 7 years of data were missing, and “complete” otherwise. Incomplete changes were concentrated in areas with sparse Landsat acquisitions prior to 1999, before implementation of systematic global imaging by Landsat 7 (Sexton et al., 2013; Potapov et al., 2012).

Forest age was estimated for each year and pixel by subtracting the year of the most recent significant forest gain from the year of interest. Pixels were classified as “new” forests if no forest cover or loss had been observed earlier in the time series within a 150 m radius (five Landsat pixels); otherwise, forests were considered “recovering.” This approach does not capture the initial years of seedling establishment and growth when cover is below this detection threshold. Also, because of the limited Landsat period, areas detected as “new” forest may actually be “recovering” from pre-1985 disturbances. Accuracy of change detection and age estimation was assessed against a reference sample of 2404 visually interpreted points distributed across the boreal biome (Figs. S14 and S15).

2.4 Estimation of aboveground biomass

Aboveground biomass carbon (AGB) was estimated as a function of forest stand age using a linear growth model (Cook-Patton et al., 2020; Fig. S16), with intercept (, σ=12.6) and slope coefficients (μ=23.2, σ=3.2) incorporating parametric uncertainty. Because ages of forests older than the 36-year time-series could not be directly observed, we assumed three scenarios of stand age to bracket carbon stock estimates in these undated stands: the absolute minimum possible age (36 years) yielding 19.1–58.4 Pg C, and typical ages for mature and old-growth stands in boreal ecosystems, i.e., 100 years yielding 35.8–80.5 Pg C, and 300 years yielding 42.4–89.2 Pg C.

These scenarios define the plausible envelope of legacy biomass in mature forest. However, estimates reflected structural biomass only and did not account for potential effects of changes in soil moisture or variation in respiration rates. To contextualize the biomass sink relative to climate-driven emissions, we also evaluated the trend in regional surface air temperature using the Climate Research Unit (CRU) dataset and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ERA-Interim reanalysis. Both records indicated significant warming over the study period, with trends of 0.038 °C yr−1 (r=0.69, p<1 × 10?5) and 0.035 °C yr−1 (r= 0.73, p <1 × 10?6) respectively (Fig. S17).

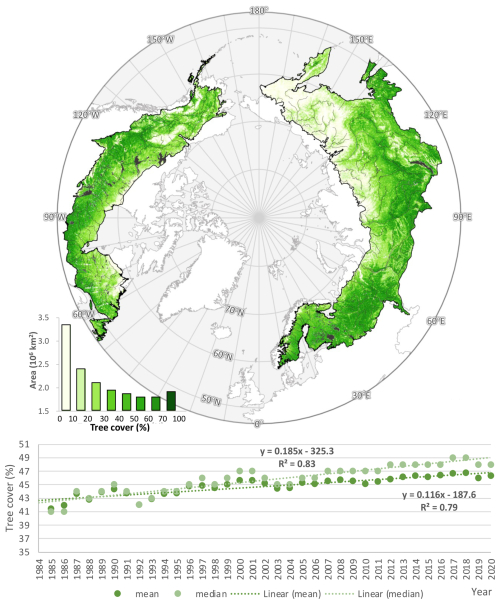

3.1 Distribution of boreal tree cover

Tree cover reaches its highest densities in the southern portion of the boreal biome and decreases progressively northward (Fig. 1). Sparse conifer stands, woodlands, herbaceous vegetation, and unvegetated barrens dominate the transition to Arctic tundra, and tree cover is nearly absent north of 71° N. Due to interspersion of tundra, wetlands, and inland water bodies, the most common local (i.e., 30 m pixel) tree-cover density across the entire boreal forest and taiga-tundra ecotone is below 5 %.

Boreal tree cover expanded from 7.153 million km2 (41.44 % of the region) in 1985 to 7.997 million km2 (46.32 %) in 2020, with a linear trend of 0.023 million km2 yr−1 (0.12 % yr−1; percent cover = 0.116 × year – 187.6, R2=0.99, p<0.001) (Fig. 1). From 1985 to 2020, the boreal tree cover increased by 0.844 million km2, a 4.3 percentage point absolute increase and a 12 % relative increase over its 1985 extent. Applying the UNFCCC forest definition of 10 %–30 % tree cover (UNFCCC, 2002; Sexton et al., 2016), the region held between 8.95 and 12.41 million km2 of forest in 2000 and between 9.41 and 13.26 million km2 in 2020.

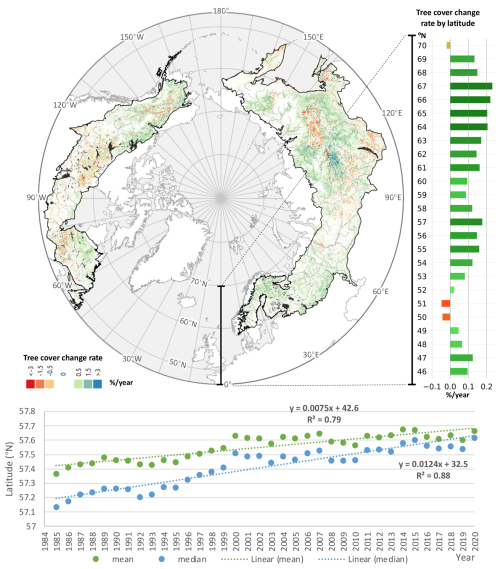

The latitudinal distribution of tree cover also shifted northward from 1985 to 2020. The mean latitude of tree cover increased by 0.29°, from 57.37° N in 1985 to 57.66° N in 2020 (mean latitude = 0.0075 × year + 42.6, R2=0.79, p <0.001). The median latitude increased more rapidly, by 0.43° (median latitude = 0.0124 × year + 32.5, R2=0.88, p<0.001), indicating widespread net expansion across the biome rather than outliers of change at either its northern or southern extremes.

Figure 1Distribution of boreal across boreal ecoregions in 2020. Estimates from 2020 are shown. Data gaps due to clouds were filled with estimates from earlier years. Ecoregions were defined by Dinerstein et al. (2017). The bottom panel shows the increasing density in the overall, pan-boreal density of tree cover from 1985 to 2020.

3.2 The pace and pattern of boreal forest change

Net biome-wide changes were underlain by strong geographic variation (Fig. 2). Net gains from 1985 to 2020 occurred at all latitudes above 53° N, with the strongest increases concentrated between 64 and 68° N. Gains in the northernmost latitudes support the hypothesis of a poleward shift in the northernmost extent of tree cover and are consistent with findings by Montesano et al. (2024), who reported long-term increases in deciduous and mixed forest components in transitional boreal zones. These structural shifts parallel recent evidence that warming-induced species diversification is strongest near the tundra margin as temperate species colonize newly viable habitat (Xi et al., 2024). In contrast, net losses were smaller in magnitude and limited to the southern boreal latitudes (47–52° N), corroborating recent observations by Rotbarth et al. (2023).

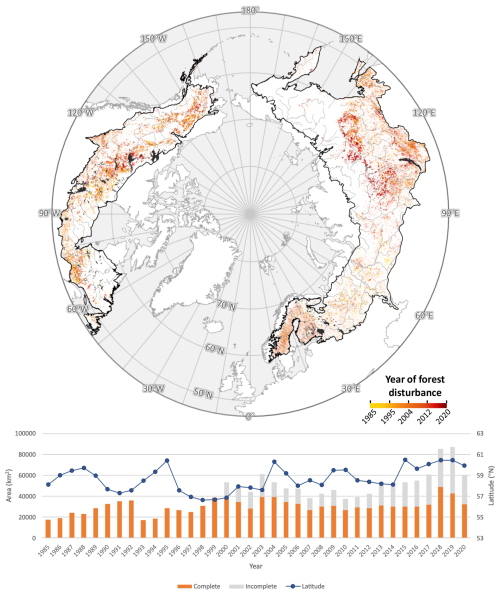

Our analysis of calibrated, high (30 m) resolution estimates of tree cover minimized potential for herbaceous growth to obscure tree mortality, for which coarser-resolution, The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)-based analyses have been criticized (Yan et al., 2024). The pan-boreal expansion of tree cover occurred against relatively stable disturbance rates over the study period (Fig. 3), and observed disturbances influenced regional patterns but did not obscure the biome-wide trend. The annual rate of disturbance increased modestly from 53 546 km2 yr−1 in 2000 to 60 275 km2 yr−1 in 2020, equivalent to a 1.8 % yr−1 linear increase (1100 km2 yr−1), or approximately 0.2 %–0.4 % of the forested area. Locations undisturbed between 1985 and 2020 exhibited net gains across nearly all latitudes, and the latitudinal distribution of disturbance – while varying strongly among years – remained broadly stationary over time (Fig. S10).

In North America, the largest gains were concentrated in the northernmost boreal, where increases in shrubs and grasses have also been reported (McManus et al., 2012). Areas of net loss corresponded to widespread forest disturbances, including wildfire and bark beetle (Dendroctonus spp.) outbreaks in British Columbia (Meddens et al., 2012), spruce budworm (Choristoneura spp.) in Quebec (Boulanger and Arseneault, 2004), and wildfire across western Canada and interior Alaska (Stocks et al., 2002). Recent shifts in transitional forest structure and composition noted by Montesano et al. (2024) lend further weight to these observations, suggesting a biome-wide response in functional traits, including increased deciduous dominance at the taiga-tundra ecotone. These findings are also partially corroborated by Rotbarth et al. (2023), who also reported tree cover gains in the boreal interior of North America but loss at the southern margins, especially in areas impacted by wildfire and harvest.

In Eurasia, hotspots of forest loss included the eastern Russian–Chinese border, agricultural zones south of the Urals, and regions affected by timber harvesting near the Russia–Finland border in the 1990s (Potapov et al., 2012). Logging and fire contributed to localized loss in eastern Russia (Krylov et al., 2014), whereas gains in northern Europe were associated with silvicultural management, afforestation, and fire suppression (Henttonen et al., 2017). Recent analyses confirm extensive regrowth in post-agricultural and permafrost-transitioning landscapes in Russia, where lidar and optical remote sensing reveal increases in regeneration potential, particularly in abandoned or disturbed sites (Neigh et al., 2025).

In Asia, net gains were observed in areas of post-Soviet agricultural abandonment, as well as in larch forests near the Yakutsk permafrost zone. These trends are consistent with increases in tall shrubs and larch (Larix spp.) at the taiga–tundra boundary (Frost and Epstein, 2014). Recovery from wildfires in the 1990s continues in these regions (Kajii et al., 2002), and permafrost thaw has been hypothesized to enhance productivity (Sato et al., 2016).

Although we did not attempt to demarcate or detect changes in a discrete tree line, our observations corroborate the boreal advancement hypothesis alongside field measurements of woody vegetation near the northern limits of tree growth and satellite-based studies demarcating the northern tree line (Frost and Epstein, 2014; Rees et al., 2020; Dial et al., 2024; Dial et al., 2022; Rotbarth et al., 2023). While analysis of tree-cover estimates avoided the potential confusion of changes in trees specifically with general NDVI-based “greening” (Yan et al., 2024), the trend's geographic variations correspond to general patterns of greening across the biome (Berner and Goetz, 2022; Sulla-Menashe et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2016; Piao et al., 2020; Guay et al., 2014).

Field studies have shown that climate, soil properties, and forest management drive large differences in boreal tree growth rates across the ecotone (Henttonen et al., 2017; Henttonen et al., 2017; Hofgaard et al., 2009). Recent shifts in transitional forest structure and composition noted by Montesano et al. (2024) lend further weight to these observations, suggesting a total biome-wide response in functional traits, including increased deciduous dominance near treeline margins. Xi et al. (2024) further demonstrate that increasing diversity near the forest–tundra boundary is associated with moderate climatic warming, although they caution that the gains are vulnerable to reversal under extremes such as drought and heatwaves. Changes in species composition remain a focal point of research (Xi et al., 2024; Mekonnen et al., 2019; Massey et al., 2023; Mack et al., 2021; Liski et al., 2003), while still remaining to be explored are the differentiation of climate and soil effects at the global scale and the discrimination of tree cover expansion due to the establishment and growth of new seedlings versus the widening of existing tree crowns.

Figure 2Spatial and temporal distribution of boreal tree cover change from 1985 to 2020. Map: significant net gains (green-blue) and losses (orange-red) of tree cover over the boreal biome. Bar chart (top-right): linear regression slope of tree cover over time, stratified by latitude. Time series (bottom): northward migration of the distribution of mean and median latitude of tree cover. Every 30 m resolution pixel included in the analysis had >30 unobscured annual tree cover estimates between 1985 and 2020.

Figure 3Total area and median latitude of boreal stand-clearing disturbances from 1985 to 2020. Trends are plotted for the portion of the boreal area where the satellite image is complete from 1984 to 2019 (“complete”) and from all locations, including where the satellite record is incomplete (“incomplete”) (Sect. S9).

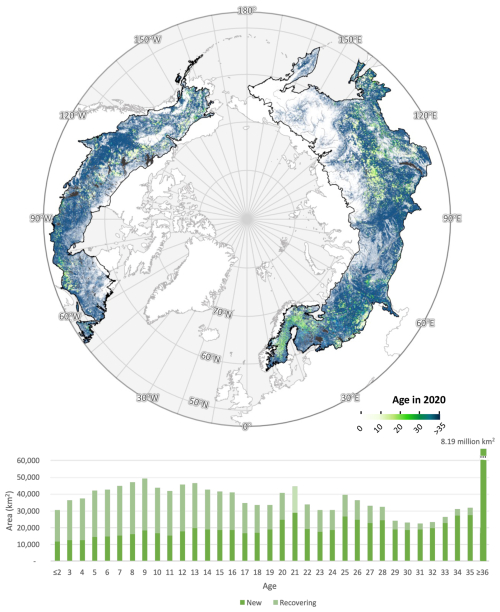

3.3 The distribution of boreal forest age

Most of the boreal forest – 8.19 million km2, or 47.5 % of the region – is older than can be directly measured from the satellite record (Fig. 4). Tree cover in these older stands was already established by the beginning of the Landsat observation period in 1985, and the slow rates of biomass accumulation in boreal ecosystems further complicate the detection of recent forest establishment (Fig. S16). However, the age of younger stands can be estimated by subtracting the year of first detected forest cover from 2020. The forest age estimator showed a root mean square error (RMSE) of 17.46 years and a mean bias of −3.27 years relative to reference data. These errors indicate that while the age maps capture broad spatial patterns and distributions, they should not be interpreted as precise pixel-level predictions. Instead, the results are most reliable when aggregated to regional or biome scales, where random errors are reduced.

Of the forested area present in 1985, 0.5 million km2 – representing 5.29 % of standing forests – was disturbed during the study period and recovered to forest by 2020. Recovering forests, combined with “new” forests gained during the Landsat era, produced a weak modal age class centered between 9 and 21 years, with a notable lapse in the youngest age classes. These young forests were concentrated in regions of intensive silviculture, including industrial plantations in Scandinavia (Henttonen et al., 2017; Liski et al., 2003; Ågren et al., 2008), and in areas recovering from wildfire. The latter trend is corroborated by reports of increasing burn frequency and extent in Siberia since the late 20th century (Kharuk et al., 2021), which has driven a rising proportion of recovering forest younger than 20 years.

Figure 4Spatial distribution of stand age (top) across the boreal ecoregion and frequency distribution of boreal stand age in 2020 (bottom). Forest age-class distribution is defined as years since establishment of pixels identified as forest in 2020. “New” forests were identified as pixels with forest cover following a gain but no prior forest cover or loss earlier in the time series within a 150 m radius (5 pixels) over the observable period (1984–2020); “recovering” forests were identified as pixels with forest cover following a gain where a forest loss had been observed previously in the series (Sect. S9).

The expansion and redistribution of boreal tree cover documented in this study has direct implications for the region's role in the global carbon cycle. Between 1985 and 2020, boreal tree cover increased by 0.844 million km2 and shifted northward by over 0.4° in median latitude, with gains concentrated at the biome's northern margin and net expansion observed across most latitudes. These changes are not only spatially extensive but demographically consequential: they reflect a growing fraction of young forests with distinct structural and functional attributes that position them as dynamic agents of carbon sequestration. Understanding the contribution of these forests to current and future carbon stocks is essential for anticipating the net climate feedbacks emerging from boreal ecosystems.

Recent models relating forest age to biomass dynamics suggest that shifting age structure will substantially influence the boreal region's contribution to the global carbon budget in the coming decades. Young forests already contribute significantly to the region's carbon sink (Pan et al., 2011). Forest age estimates carry substantial uncertainty (RMSE ≈ 17 years), limiting their precision at the pixel scale. They remain useful for identifying large-scale patterns and average age structures, but future work will be required to reduce error and quantify regional biases. Forests with known stand ages (less than 36 years since disturbance) hold between 1.1 and 5.9 Pg C in aboveground biomass, based on global growth models (Cook-Patton et al., 2020). The ages of forests where no disturbance was observed during the satellite era remain unknown, but plausible aboveground carbon stocks in these older stands can be bracketed between a low-end scenario assuming 36 years of age (19.1–58.4 Pg C) and a high-end scenario assuming 300 years (42.4–89.2 Pg C). Based on these estimates, forests younger than 36 years of age comprise 1.35 %–14.20 % of the total boreal aboveground biomass carbon stock – consistent with their 15.4 % share of total forest area. Including belowground biomass would raise these values by approximately 25 %, based on a mean global root:shoot ratio of 0.25 (Huang et al., 2021).

If allowed to mature without further disturbance, these young forests could sequester an additional 2.3–3.8 Pg C in aboveground biomass. Forests newly established during the observation period contribute between 0.8 and 3.5 Pg C today, exceeding the 0.3–2.4 Pg C held in forests recovering from recorded disturbances. Over the next 36 years, new forests represent a potential additional aboveground sink of 1.3–2.0 Pg C (0.036–0.18 Pg C yr−1), compared to 1.0–1.8 Pg C (0.028–0.05 Pg C yr−1) from recovering forests. This distinction reflects both the greater area occupied by new forests (7.6 % vs. 6.7 %) and their older mean stand age. These findings support recent observations by Neigh et al. (2025), who reported a disproportionately large contribution of young, regrowing stands to carbon storage in the Russian boreal.

The additional carbon in new forests could help offset warming-induced increases in boreal ecosystem respiration, which have been estimated between 5 and 28 Pg C from 1985 to 2020 (Fig. S16). Both climate warming and carbon dioxide (CO2) fertilization are expected to enhance productivity (Norby and Zak, 2011), and the spatial pattern of observed tree-cover growth aligns with model predictions of increased seasonal CO2 exchange above 40° N (Forkel et al., 2016). However, several mechanisms may limit this offset. First, temperature sensitivity of respiration can itself be temperature-dependent (Koven et al., 2017). Second, carbon accumulation rates decline with forest age (Odum, 1969). Third, thawing of permafrost can release substantial legacy carbon stocks (Schuur et al., 2015). Fourth, increases in fire and harvest activity may reverse regional gains in biomass (Gauthier et al., 2015; Kharuk et al., 2021). Compositional and functional transitions may also alter sink dynamics (Montesano et al., 2024; Xi et al., 2024).

The long-term persistence of tree-cover expansion depends not only on productivity, but also on the capacity of boreal soils to support woody vegetation. It remains uncertain whether boreal soils – especially under changing permafrost regimes – can structurally sustain expanded forest cover (Koven, 2013). Additional uncertainty stems from the rising role of anthropogenic fire in some parts of the boreal zone (Doerr and Santín, 2016; Mollicone et al., 2006). Our biomass estimates are derived from models for natural forests and do not account for differences between managed and unmanaged systems (Kuuluvainen and Gauthier, 2018) or for anticipated changes in fire regimes.

While expansion of tree cover may imply increased carbon storage, nonlinear biodiversity responses to warming complicate projections. Enhanced taxonomic and functional diversity may improve ecological resilience (Xi et al., 2024), but these benefits are constrained by the growing frequency of climatic extremes. Moreover, biodiversity-related feedbacks on carbon balance remain difficult to predict under scenarios of increasing disturbance. Ultimately, all of these processes – forest growth, mortality, disturbance, and compositional change – are already underway across the boreal biome. Quantifying the balance of autotrophic and heterotrophic carbon fluxes remains critical to understanding and managing the global climate system.

While our calibration was stratified across ecological and topographic gradients to minimize overfitting, more stringent tests could be obtained by withholding subsets of the reference data (e.g., complete LVIS flightlines or high-resolution imagery tiles) within specific ecozones and revalidating predictions at those sites. Such “leave-tile-out” cross-validation would provide a direct assessment of model transferability at biome boundaries, including ecotones. A limitation is the absence of temporally repeated reference data, which prevents direct assessment of stability (bias drift). Our calibration and annual compositing reduce some risks, but nonstationary, unaccounted-for sensor differences, phenological shifts, and atmospheric noise remain possible contributors to temporal bias.

The accuracy of the reference datasets themselves warrants consideration. Montesano et al. (2023) showed that LVIS canopy heights agree closely with NASA G-LiHT airborne LiDAR, with coefficients of determination (R2) up to 0.87 and root mean square errors of approximately 1–2 m depending on canopy cover and temporal offset. G-LiHT, with its high point density and small footprint, is widely regarded as a reference standard, though its own absolute error was not quantified in that study. For high-resolution optical reference data (QuickBird imagery, Google Earth interpretations), prior work (Montesano et al., 2009, 2016) demonstrated their utility in validating coarse-resolution products but also did not report independent accuracy or inter-observer precision. These limitations highlight the need for future work to establish formal error budgets for reference datasets, while affirming that they provide the best available benchmarks for tree cover calibration and validation.

This pan-boreal assessment provides the strongest empirical confirmation to date of a northward shift in boreal tree cover, long hypothesized by climate–vegetation models. By retrieving the longest, highest-resolution, and most spatially complete record of calibrated boreal tree cover available, we applied machine learning to the Landsat 4, 5, 7, and 8 surface reflectance archives to reconstruct annual, 30 m maps of forest change from 1985 to 2020. Time-series analysis of 1.9 × 108 pixels revealed widespread increases in tree-cover density and a poleward shift in forest distribution, occurring despite relatively stable disturbance rates across the biome.

Although the net trends are globally significant, they mask substantial geographic and temporal heterogeneity, as well as complexity in the ecological processes underlying forest change. These results underscore the need for high-resolution, disturbance-aware metrics to supplement NDVI-based assessments, particularly in climatically sensitive boreal transition zones (Yan et al., 2024). A more complete understanding of boreal forest dynamics will require integration of satellite time series with field-based measurements of canopy structure and the environmental drivers of growth, mortality, and species turnover. Moreover, translating the resulting information into action to forestall and adapt to climate change will require effective communication across scientific, government, and commercial domains of human activity.

The data for this paper is made available online at https://www.terrapulse.com/terraView/ccs (last access: 1 December 2025).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-23-1089-2026-supplement.

MF and JOS designed and developed the tree-cover and forest-change algorithms. PMM, PW, and MJM conducted the validation and calibration. CSRN and PMM co-edited the manuscript, CSRN secured research funding to conduct the study. BP commented on the final manuscript. NC and LC conducted the carbon impact analysis. NC conducted the ecosystem respiration analysis. SC developed the platform on AWS. MAW, WW, and AE interpreted the validation dataset. JOS conceived the study and compiled the manuscript with contributions from all coauthors.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This research was supported by the NASA Carbon Cycle Science Program (NNH16ZDA001N-CARBON), National Science Foundation Arctic System Science Program (1604105), and NASA ABoVE (80NSSC19M0112). Satellite image processing was performed by terraPulse, Inc. on Amazon Web Services (AWS). Reference data for calibration and validation was produced on the NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center ADAPT HEC cluster provided by the NASA High-End Computing Program. Aaron Wells (ABR, Inc.), Celio De Sousa (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, URSA, Inc.), and Jaime Nickeson (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, SSAI, Inc.) contributed reference observations of forest cover and disturbance.

This research has been supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (grant nos. NNH16ZDA001N-CARBON and 80NSSC19M0112).This research was supported by the NASA Carbon Cycle Science Program (grant no. NNH16ZDA001N-CARBON), the National Science Foundation Arctic System Science Program (grant no. 1604105), and NASA's ABoVE (grant no. 80NSSC19M0112).

This paper was edited by Benjamin Stocker and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ågren, G. I., Hyvönen, R., and Nilsson, T.: Are Swedish forest soils sinks or sources for CO2 – model analyses based on forest inventory data, Biogeochemistry, 89, 139–149, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-007-9151-x, 2008.

Beck, P. S. A., Juday, G. P., Alix, C., Barber, V. A., Winslow, S. E., Sousa, E. E., Heiser, P., Herriges, J. D., and Goetz, S. J.: Changes in forest productivity across Alaska consistent with biome shift, Ecol. Lett., 14, 373–379, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01598.x, 2011.

Berner, L. T. and Goetz, S. J.: Satellite observations document trends consistent with a boreal forest biome shift, Glob. Change Biol., 28, 3275–3292, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16100, 2022.

Betts, R. A.: Offset of the potential carbon sink from boreal forestation by decreases in surface albedo, Nature, 408, 187–190, https://doi.org/10.1038/35041545, 2000.

Bonan, G. B.: Forests and climate change: Forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests, Science, 320, 1444–1449, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1155121, 2008.

Boulanger, Y. and Arseneault, D.: Spruce budworm outbreaks in eastern Quebec over the last 450 years, Can. J. For. Res., 34, 1035–1043, https://doi.org/10.1139/x03-269, 2004.

Brice, M., Boucher, Y., Girardin, M. P., Marchand, W., Tremblay, J.-P., and Krause, C.: Moderate disturbances accelerate forest transition dynamics under climate change in the temperate–boreal ecotone of eastern North America, Glob. Change Biol., 26, 4418–4435, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15115, 2020.

Carroll, M., DiMiceli, C., Sohlberg, R., Huang, C., and Hansen, M. C.: MODIS Vegetative Cover Conversion and Vegetation Continuous Fields, in: Land Remote Sensing and Global Environmental Change: NASA's Earth Observing System and the Science of ASTER and MODIS, edited by: Ramachandran, B., Justice, C. O., and Abrams, M. J., 725–745, Springer, New York, NY, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6749-7_32, 2011.

Chen, D., Loboda, T. V., He, T., Zhang, Y., and Liang, S.: Strong cooling induced by stand-replacing fires through albedo in Siberian larch forests, Sci. Rep., 8, 4821, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23253-1, 2018.

Cook-Patton, S. C., Leavitt, S. M., Gibbs, D., Harris, N. L., Lister, K., Anderson-Teixeira, K. J., Briggs, R. D., Chazdon, R. L., Crowther, T. W., and Ellis, P. W.: Mapping carbon accumulation potential from global natural forest regrowth, Nature, 585, 545–550, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2686-x, 2020.

Dial, R. J., Maher, C. T., Hewitt, R. E., and Sullivan, P. F.: Sufficient conditions for rapid range expansion of a boreal conifer, Nature, 608, 546–551, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05093-2, 2022.

Dial, R. J., Maher, C. T., Hewitt, R. E., Wockenfuss, A. M., Wong, R. E., Crawford, D. J., Zietlow, M. G., and Sullivan, P. F.: Arctic sea ice retreat fuels boreal forest advance, Science, 383, 877–884, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh2339, 2024.

Dinerstein, E., Olson, D., Joshi, A., Vynne, C., Burgess, N. D., Wikramanayake, E., Hahn, N., Palminteri, S., Hedao, P., and Noss, R.: An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm, BioScience, 67, 534–545, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix014, 2017.

Doerr, S. H. and Santín, C.: Global trends in wildfire and its impacts: perceptions versus realities in a changing world, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., 371, 20150345, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0345, 2016.

Elmendorf, S. C., Henry, G. H. R., Hollister, R. D., Björk, R. G., Bjorkman, A. D., Callaghan, T. V., and Collier, L. S.: Plot-scale evidence of tundra vegetation change and links to recent summer warming, Nat. Clim. Change, 2, 453–457, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1465, 2012.

Fan, L., Wigneron, J.-P., Ciais, P., Chave, J., Brandt, M., Sitch, S., Yue, C., Bastos, A., Li, X., Qin, Y., Yuan, W., Schepaschenko, D., Mukhortova, L., Li, X., Liu, X., Wang, M., Frappart, F., Xiao, X., Chen, J., Ma, M., Wen, J., Chen, X., Yang, H., van Wees, D., and Fensholt, R.: Siberian carbon sink reduced by forest disturbances, Nature Geoscience, 16, 56–62, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-022-01087-x, 2023.

Forkel, M., Carvalhais, N., Rödenbeck, C., Keeling, R., Heimann, M., Thonicke, K., Reichstein, M., and High-Latitude Ecosystem Modeling Group: Enhanced seasonal CO2 exchange caused by amplified plant productivity in northern ecosystems, Science, 351, 696–699, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4971, 2016.

Frost, G. V. and Epstein, H. E.: Tall shrub and tree expansion in Siberian tundra ecotones since the 1960s, Glob. Change Biol., 20, 1264–1277, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12406, 2014.

Gauthier, S., Bernier, P., Kuuluvainen, T., Shvidenko, A. Z., and Schepaschenko, D. G.: Boreal forest health and global change, Science, 349, 819–822, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa9092, 2015.

Guay, K. C., Beck, P. S. A., Berner, L. T., Goetz, S. J., Baccini, A., and Buermann, W.: Vegetation productivity patterns at high northern latitudes: a multi-sensor satellite data assessment, Glob. Change Biol., 20, 3147–3158, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12647, 2014.

Henttonen, H. M., Nöjd, P., and Mäkinen, H.: Environment-induced growth changes in the Finnish forests during 1971–2010 – An analysis based on National Forest Inventory, For. Ecol. Manag., 386, 22–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2016.12.021, 2017.

Hofgaard, A., Dalen, L., and Hytteborn, H.: Tree recruitment above the treeline and potential for climate-driven treeline change, J. Veg. Sci., 20, 1133–1144, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2009.01106.x, 2009.

Holtmeier, F.-K. and Broll, G.: Sensitivity and response of northern hemisphere altitudinal and polar treelines to environmental change at landscape and local scales, Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr., 14, 395–410, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-822X.2005.00168.x, 2005.

Huang, Y., Ciais, P., Santoro, M., Makowski, D., Chave, J., Schepaschenko, D., Abramoff, R. Z., Goll, D. S., Yang, H., Chen, Y., Wei, W., and Piao, S.: A global map of root biomass across the world's forests, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 13, 4263–4274, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-4263-2021, 2021.

IPCC: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report, Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R. K., and Meyer, L. A., IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/ (last access: 23 December 2025), 2014.

IPCC: Global Warming of 1.5°C, IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., Shukla, P. R., Pirani, A., Moufouma-Okia, W., Péan, C., Pidcock, R., Connors, S., Matthews, J. B. R., Chen, Y., Zhou, X., Gomis, M. I., Lonnoy, E., Maycock, T., Tignor, M., and Waterfield, T., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY, USA, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157940, 2018.

IPCC: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Core Writing Team, Lee, H., and Romero, J., IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 35–115, https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647, 2023.

Kajii, Y., Kato, S., Streets, D. G., Tsai, N. Y., Shibata, T., Matsumoto, J., and Kajino, M.: Boreal forest fires in Siberia in 1998: Estimation of area burned and emissions of pollutants by advanced very high resolution radiometer satellite data, J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres, 107, ACH 4-1–ACH 4-8, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JD001078, 2002.

Kharuk, V. I., Ponomarev, E. I., Ivanova, G. A., Dvinskaya, M. L., Coogan, S. C. P., and Flannigan, M. D.: Wildfires in the Siberian taiga, Ambio, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-020-01490-x, 2021.

Koven, C. D.: Boreal carbon loss due to poleward shift in low-carbon ecosystems, Nat. Geosci., 6, 452–456, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1801, 2013.

Koven, C. D., Hugelius, G., Lawrence, D. M., and Wieder, W. R.: Higher climatological temperature sensitivity of soil carbon in cold than warm climates, Nat. Clim. Change, 7, 817–822, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3421, 2017.

Krylov, A., McCarty, J. L., Potapov, P., Loboda, T., Tyukavina, A., Turubanova, S., and Hansen, M. C.: Remote sensing estimates of stand-replacement fires in Russia, 2002–2011, Environ. Res. Lett., 9, 105007, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/9/10/105007, 2014.

Kuuluvainen, T. and Gauthier, S.: Young and old forest in the boreal: critical stages of ecosystem dynamics and management under global change, For. Ecosyst., 5, 26, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-018-0149-8, 2018.

Liski, J., Korotkov, A. V., Prins, C. F. L., Karjalainen, T., Victor, D. G., and Kauppi, P. E.: Increased Carbon Sink in Temperate and Boreal Forests, Climatic Change, 61, 89–99, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026365005696, 2003.

Mack, M. C., Walker, X. J., Johnstone, J. F., Alexander, H. D., Melvin, A. M., Miller, S. N., and Goetz, S. J.: Carbon loss from boreal forest wildfires offset by increased dominance of deciduous trees, Science, 372, 280–283, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abf3903, 2021.

Massey, R., Rogers, B. M., Berner, L. T., Cooperdock, S., Mack, M. C., Walker, X. J., and Goetz, S. J.: Forest composition change and biophysical climate feedbacks across boreal North America, Nat. Clim. Chang., 13, 1368–1375, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01851-w, 2023.

McManus, K. M., Morton, D. C., Masek, J. G., Wang, D., Sexton, J. O., and Nagol, J.: Satellite-based evidence for shrub and graminoid tundra expansion in northern Quebec from 1986 to 2010, Glob. Change Biol., 18, 2313–2323, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02708.x, 2012.

Meddens, A. J. H., Hicke, J. A., and Ferguson, C. A.: Spatiotemporal patterns of observed bark beetle-caused tree mortality in British Columbia and the western United States, Ecol. Appl., 22, 1876–1891, https://doi.org/10.1890/11-1785.1, 2012.

Mekonnen, Z. A., Riley, W. J., Randerson, J. T., Grant, R. F., and Rogers, B. M.: Expansion of high-latitude deciduous forests driven by interactions between climate warming and fire, Nat. Plants, 5, 952–958, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-019-0495-8, 2019.

Mollicone, D., Eva, H. D., and Achard, F.: Human role in Russian wildfires, Nature, 440, 436–437, https://doi.org/10.1038/440436a, 2006.

Montesano, P. M., Nelson, R., Sun, G., Margolis, H., Kerber, A., and Ranson, K. J.: MODIS tree cover validation for the circumpolar taiga–tundra transition zone, Remote Sensing of Environment, 113, 2130–2141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2009.05.021, 2009.

Montesano, P. M., Sun, G., Dubayah, R. O., and Ranson, K. J.: Spaceborne potential for examining taiga–tundra ecotone form and vulnerability, Biogeosciences, 13, 3847–3861, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-13-3847-2016, 2016.

Montesano, P. M., Neigh, C. S. R., Macander, M. J., Wagner, W., Duncanson, L. I., Wang, P., Sexton, J. O., Miller, C. E., and Armstrong, A. H.: Patterns of regional site index across a North American boreal forest gradient. Environmental Research Letters, 18, 075006, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/acdcab, 2023.

Montesano, P. M., Frost, M., Li, J., Carroll, M., Neigh, C. S. R., Macander, M. J., Sexton, J. O., and Frost, G. V.: A shift in transitional forests of the North American boreal will persist through 2100, Nature Communications: Earth and Environment, 5, 1, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01454-z, 2024.

Neigh, C. S. R., Nelson, R. F., Ranson, K. J., Margolis, H. A., Montesano, P. M., Sun, G., and Goetz, S. J.: Taking stock of circumboreal forest carbon with ground measurements, airborne and spaceborne LiDAR, Remote Sens. Environ., 137, 274–287, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2013.06.019, 2013.

Neigh, C., Montesano, P. M., Sexton, J. O., Wooten, M., Wagner, W., Feng, M., Carvalhais, N., Calle, L., and Carroll, M. L.: Russian forests show strong potential for young forest growth, Nature Communications: Earth and Environment, 6, 1, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02006-9, 2025.

Norby, R. J. and Zak, D. R.: Ecological lessons from Free-Air CO2 Enrichment (FACE) experiments, Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst., 42, 181–203, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102209-144647, 2011.

Odum, E. P.: The strategy of ecosystem development, Science, 164, 262–270, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.164.3877.262, 1969.

Pan, Y., Birdsey, R. A., Fang, J., Houghton, R., Kauppi, P. E., Kurz, W. A., and Phillips, O. L.: A large and persistent carbon sink in the world's forests, Science, 333, 988–993, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1201609, 2011.

Pan, Y., Birdsey, R. A., Phillips, O. L., Houghton, R. A., Fang, J., Kauppi, P. E., Keith, H., Kurz, W. A., Ito, A., Lewis, S. L., Nabuurs, G.-J., Shvidenko, A., Hashimoto, S., Lerink, B., Schepaschenko, D., Castanho, A., and Murdiyarso, D.: The enduring world forest carbon sink, Nature, 631, 563–569, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07602-x, 2024.

Piao, S., Wang, X., Ciais, P., Zhu, B., Wang, T., and Liu, J.: Characteristics, drivers and feedbacks of global greening, Nat. Rev. Earth Environ., 1, 14–27, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-019-0001-x, 2020.

Potapov, P., Turubanova, S., Zhuravleva, I., Hansen, M., Yaroshenko, A., and Manisha, A.: Forest Cover Change within the Russian European North after the Breakdown of Soviet Union (1990–2005), International Journal of Forestry Research, 2012, 729614, https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/729614, 2012.

Randerson, J. T., Liu, H., Flanner, M. G., Chambers, S. D., Jin, Y., Hess, P. G., and Rasch, P. J.: The impact of boreal forest fire on climate warming, Science, 314, 1130–1132, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1132075, 2006.

Rees, W. G., Stammler, F. M., Danks, F. S., and Vitebsky, P.: Is subarctic forest advance able to keep pace with climate change?, Glob. Change Biol., 26, 3965–3977, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15181, 2020.

Rotbarth, R., Van Nes, E. H., Scheffer, M., Jepsen, J. U., Vindstad, O. P. L., Xu, C., and Holmgren, M.: Northern expansion is not compensating for southern declines in North American boreal forests, Nat Commun, 14, 3373, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39092-2, 2023.

Sato, H., Kobayashi, H., Iwahana, G., and Ohta, T.: Endurance of larch forest ecosystems in eastern Siberia under warming trends, Ecol. Evol., 6, 5690–5704, https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.2264, 2016.

Scheffer, M., Hirota, M., Holmgren, M., van Nes, E. H., and Chapin, F. S.: Thresholds for boreal biome transitions, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 109, 21384–21389, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1219844110, 2012.

Schuur, E. A. G., Abbott, B. W., Bowden, W. B., Brovkin, V., Camill, P., Davidson, E. A., and Hayes, D. J.: Climate change and the permafrost carbon feedback, Nature, 520, 171–179, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14338, 2015.

Sexton, J. O., Noojipady, P., Song, X.-P., Feng, M., Song, D. X., Kim, D. H., and Hansen, M. C.: Global, 30 m resolution continuous fields of tree cover: Landsat-based rescaling of MODIS vegetation continuous fields with LiDAR-based estimates of error, Int. J. Digit. Earth, 6, 427–448, https://doi.org/10.1080/17538947.2013.786146, 2013.

Sexton, J. O., Noojipady, P., Song, X.-P., Feng, M., Song, D., Kim, D., Anand, A., Huang, C., Channan, S., Pimm, S. L., and Townshend, J. R.: Conservation policy and the measurement of forests, Nature Climate Change, 6, 192–196, https://doi.org/10.1038/NCLIMATE2816, 2016.

Stocks, B. J., Mason, J. A., Todd, J. B., Bosch, E. M., Wotton, B. M., Amiro, B. D., Flannigan, M. D., Hirsch, K. G., Logan, K. A., Martell, D. L., and Skinner, W. R.: Large forest fires in Canada, 1959–1997, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 107, FFR 5-1-FFR 5-12, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JD000484, 2002.

Sulla-Menashe, D., Woodcock, C. E., and Friedl, M. A.: Canadian boreal forest greening and browning trends: an analysis of biogeographic patterns and the relative roles of disturbance versus climate drivers, Environ. Res. Lett., 13, 014007, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa9b88, 2018.

Taylor, A. R., Boulanger, Y., Price, D. T., Cyr, D., McGarrigle, E., Rammer, W., and Kershaw, J. A.: Rapid 21st century climate change projected to shift composition and growth of Canada’s Acadian Forest Region, Forest Ecology and Management, 405, 284–294, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2017.07.033, 2017.

Walker, X. J., Rogers, B. M., Baltzer, J. L., Baltzer, B., Barrett, M., Bourgeau-Chavez, L., and Mack, M. C.: Increasing wildfires threaten historic carbon sink of boreal forest soils, Nature, 572, 520–523, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1474-y, 2019.

UNFCCC: Report of the Conference of the Parties on its seventh session, held at Marrakesh from 29 October to 10 November 2001, Addendum, Part two: Action taken by the Conference of the Parties, I, https://unfccc.int/documents/2516 (last access: 23 December 2025), 2002.

Véga, C. and St-Onge, B.: Mapping site index and age by linking a time series of canopy height models with growth curves, Forest Ecology and Management, 257, 951–959, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.10.029, 2009.

Xi, Y., Zhang, W., Wei, F., Fang, Z., and Fensholt, R.: Boreal tree species diversity increases with global warming but is reversed by extremes, Nature Plants, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-024-01794-w, 2024.

Yan, Y., Piao, S., Hammond, W. M., Chen, A., Hong, S., Xu, H., Munson, S. M., Myneni, R. B., and Allen, C. D.: Climate-induced tree-mortality pulses are obscured by broad-scale and long-term greening, Nature Ecology and Evolution, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02372-1, 2024.

Zhu, Z., Piao, S., Myneni, R. B., Huang, M., Zeng, Z., Canadell, J. G., and Ciais, P.: Greening of the Earth and its drivers, Nat. Clim. Change, 6, 791–795, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3004, 2016.