the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Limited physical protection leads to high organic carbon reactivity in anoxic Baltic Sea sediments

Silvia Placitu

Sebastiaan J. van de Velde

Astrid Hylén

Mats Eriksson

Per O. J. Hall

Steeve Bonneville

Marine sediments bury ∼ 160 Tg organic carbon (OC) yr−1 globally, with ∼ 90 % of the burial occurring in continental margin sediments. It is generally believed that OC is buried more efficiently in sediments underlying anoxic bottom waters. However, recent studies revealed that sediments in the central Baltic Sea exhibit very high OC mineralization rates and consequently low OC burial efficiencies (∼ 5 %–10 %), despite being overlaid by long-term anoxic bottom waters. Here, we investigate factors contributing to this unexpectedly high OC mineralization rates in the Western Gotland Basin (WGB), a sub-basin of the central Baltic Sea. We sampled five sites along a transect in the WGB, including two where organic carbon-iron (OC–Fe) associations were quantified. Sulphate reduction rate measurements indicated that OC reactivity (k) was much higher than expected for anoxic sediments. High OC loadings (i.e., OC concentrations normalized to sediment specific surface area) and low OC–Fe associations showed that physical protection of OC is limited. Overall, these results suggest that the WGB sediments receive large amounts of bulk OC relative to the supply of mineral particles, far exceeding the potential for OC physical protection. As a result, a large fraction of OC is free from associations with mineral surfaces, thus the OC reactivity is high, despite anoxic bottom waters. Overall, our results demonstrate that anoxia does not always lead to lower OC mineralization rates and increased burial efficiencies in sediments.

- Article

(1883 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(634 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

OC burial within marine sediments modulates atmospheric oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations over geological timescales (Berner, 1982). Marine sediments are the largest active OC sink with ∼ 160 Tg OC buried annually on a global scale (Berner, 1982; Burdige, 2007; Hedges and Keil, 1995; LaRowe et al., 2020). OC burial efficiency, which corresponds to the percent of the OC deposition flux to the sediments that is eventually preserved (and therefore, not mineralized) is low globally, with on average ∼ 10 % of the OC settling at the sediment-water interface being buried (Burdige, 2007). However, this number can reach up to 80 % in continental shelf and coastal sediment depocenters (Blair and Aller, 2012; Canfield, 1994; Henrichs, 1992; Ingall and Cappellen, 1990; Ståhl et al., 2004). Multiple factors influence OC burial and mineralization rates (Arndt et al., 2013; LaRowe et al., 2020) and specifically, the availability of O2 in the benthic environment has been suggested to play a pivotal role in regulating the sediment biogeochemistry and the structure of the faunal community, which in turn affects the efficiency and pathways of OC remineralization and burial (Kristensen et al., 2012; Middelburg and Levin, 2009). However, the extent to which O2 influences the OC burial efficiency remains a topic of debate (Canfield, 1994; Middelburg and Levin, 2009; van de Velde et al., 2023). It is often reported that sediments deposited under anoxic bottom waters tend to exhibit apparent higher OC preservation.

This pattern is generally attributed not to the effective preservation of organic carbon in anoxic environments, but rather as the result of O2 strongly enhancing OC mineralization when present. Several processes explain this : (i) aerobic respiration yields more free energy than anaerobic pathways, leading to faster degradation (LaRowe and Van Cappellen, 2011), (ii) certain complex organic molecules, such as lignin, can be more efficiently degraded via oxidative enzymes available only under aerobic conditions (Megonigal et al., 2003; Burdige, 2007; Canfield, 1994), (iii) aerobic organisms are capable of degrading OM completely to CO2 (via the Krebs cycle) while mineralization under anoxic condition proceeds through a multi-step anaerobic food chains involving syntrophic interactions among specialized consortia which makes the degradation slower and less efficient (Arndt et al., 2013); (iv) oxygenated sediments support macrofauna that can directly or indirectly stimulate mineralization through bioturbation and bioirrigation and prevent accumulation of reduced toxic products such as H2S (Kristensen et al., 1992; Aller and Aller, 1998; Papaspyrou et al., 2007; van de Velde et al., 2020).

However, determining a clear relationship between burial efficiency and O2 exposure is challenging, as the OC mineralization can be hindered by physical protection mechanisms, such as adsorption on – or coprecipitation with – organic and inorganic matrices, forming `geomacromolecules' highly resistant to enzymatic hydrolysis and bacterial mineralization (Jørgensen, 2006). Examples of such processes are the formation of authigenic minerals, adsorption to mineral surfaces, encapsulation by refractory macromolecules or complexation with metals (Burdige, 2007; Henrichs, 1992; Lalonde et al., 2012). OC loading, defined as the ratio between OC content and specific surface area (SSA) of sediment, reflects the amount of OC associated with the total mineral surface available – including clays, Al, Mn, Fe oxides and other mineral phases – and is commonly used as a proxy to understand the OC fate in sediments. Because of their high SSA and positive surface charge, which confer enhanced adsorption capacity, reactive iron oxides (FeR) have been recognized for their significant role in sorbing OC in soils and sediments (Barber et al., 2014; Faust et al., 2021; Lalonde et al., 2012; Mehra and Jackson, 1958; Placitu et al., 2024; Yao et al., 2023).

Recently, studies in the Baltic Sea suggested that the magnitude of the positive effect of O2 level on OC mineralization rates has been overestimated (Nilsson et al., 2019; van de Velde et al., 2023). Extensive regions of the Baltic Sea suffer from prolonged periods of anoxia (O2<0.5 µM) due to eutrophication caused by intense land activities in the drainage area, strongly stratified waters induced by a permanent halocline around 60–80 m depth and limited water exchange with the North Sea, which lead to a relatively long water residence time of 25–35 years (Hall et al., 2017). Despite the absence of O2 in bottom waters over a large area of the central Baltic Sea, carbon budget calculations indicate that ∼ 22 Tg OC is mineralized and recycled back to the water column annually, while the long-term burial only involves 1.0 ± 0.3 Tg OC (Nilsson et al., 2019). This suggests that sedimentary OC in the Baltic Sea is more reactive than the environmental conditions would predict. van de Velde et al. (2023), combining in situ benthic chamber lander and core-based measurements, showed that the OC mineralization rates in anoxic sediments in the central Baltic Sea are much higher, and OC burial efficiencies much lower, than previously reported for sediments underlying anoxic bottom waters. Here, we evaluate how physical protection influences the mineralization and burial of OC by investigating five sites along a transect across the Western Gotland Basin (WGB) in the central Baltic Sea. We report OC decay rate constants (k) and OC loadings from five stations and quantify the OC–Fe associations (the so-called “rusty carbon sink”) at two stations representing contrasting redox conditions: one deep, persistently anoxic site and one comparatively shallow, hypoxic station.

2.1 Study area and sampling

The Baltic Sea is the largest brackish water body in the world (Björck, 1995), spanning from latitude 53 to 66° N and longitude 10 to 30° E, covering an area of approximately 370 000 km2. Enclosed by the landmasses of Eastern and Central Europe and Scandinavia (Andrén et al., 2000), it connects to the North Sea via the Danish-Swedish straits, Öresund and Store Bælt. The vast drainage basin extends nearly 2 million km2 and is home to approximately ∼ 85 million people (Nilsson et al., 2021 and references therein).

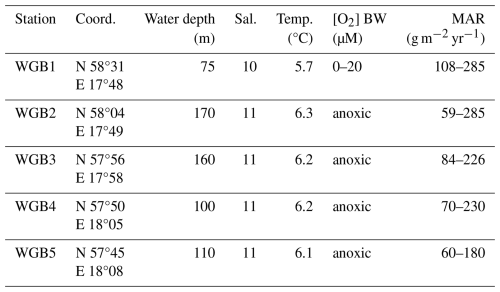

During a cruise in August 2021 aboard the R/V Skagerak, five sites (named WGB1 to WGB5) were sampled along a transect in the Western Gotland Basin, WGB (Fig. 1, Table 1). Bottom-water temperature, salinity and O2 were recorded through a CTD instrument (SBE 911, Sea-Bird Scientific) equipped with a high-accuracy O2 sensor (SBE 43, Sea-Bird Scientific). Sediment cores were retrieved using a GEMAX gravity corer (9 cm inner diameter). Two cores from each station were sectioned at 0.5 cm resolution from 0 to 2 cm depth, at 1 cm resolution between 2 and 6 cm depth, and in 2 cm slices from 6 to 20 cm depth in ambient air and samples were frozen until determination of the specific surface area (SSA) of the sedimentary particles, sedimentary organic carbon (SOC), nitrogen (N), and δ13C signature. At stations WGB1 and WGB2, two extra sediment cores were collected for the determination of OC–Fe associations. These cores were processed within a glovebag (Captair Pyramid, Erlab, France) under N2 atmosphere immediately after collection. Slicing was done at 1 cm intervals to a depth of 15 cm. Sediment sections were then transferred to 50 mL Falcon tubes (VWR, USA) and frozen until analysis.

Determination of porewater sulphate (SO), sulphate reduction rates (SRR), porosity, and 210Pb dating are detailed in van de Velde et al. (2023). Briefly, two cores at each station were sectioned under N2 atmosphere in a portable glove bag (Captair Pyramid, Erlab, France) at the same resolution as the SOC cores and porewater was collected using Rhizon samplers (pore size ∼ 0.15 µ m; Rhizosphere Research Products, The Netherlands). Porewater samples for SO analysis were stabilized using ZnAc (2.25 mL of a 10 % ZnAc solution per 0.25 mL sample) and stored at 4 °C. Two subcores (2.5 cm inner diameter, 20 cm length) were collected from the GEMAX corer at each station for SRR measurements, using the 35S radiotracer method (Jørgensen, 1978) immediately on retrieval, and the tracer addition and incubation started within 15 min of core collection. Duplicate cores were collected from two different GEMAX casts. One core per station was collected for 210Pb dating at Linköping University, Sweden.

Figure 1Sampling locations in the Western Gotland Basin, Baltic Sea. The bathymetry is from https://emodnet.ec.europa.eu/en (last access: 9 December 2025).

2.2 SOC, N, δ13C signature and OC loadings

Prior to determination of SOC, N, and isotopic signature, sediments were freeze dried and homogenized by gentle grinding in an agate mortar, which was cleaned with acetone after each sample. Typically, 15 to 30 mg of dry sediment were weighed in a silver capsule and decarbonated via fumigation overnight in a desiccator using 37 % HCl fuming acid after adding a drop of MilliQ water to the sediment (Harris et al., 2001). The samples were then dried under an infrared lamp and transferred into tin capsules before being loaded into on an elemental analyser (Sercon Europa EA-GSL; Sercon Ltd., Crewe, UK) coupled to an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS; Sercon 20-22) at the ISOGOT facility (Department of Earth Sciences, University of Gothenburg). A certified reference material (high organic content sediment standard; Elemental Microanalysis, UK) was used as an internal standard throughout analysis, approximately every 10–12 samples. This standard has a certified isotope value of δ13C −26.27 ‰. Drift was corrected relative to the standard and reproducibility was determined from replicate standard analyses. Blanks were run at the beginning of each analytical run to verify negligible contamination from previous analyses.) Linearity was assessed during annual service using reference gases (CO2).

SOC and N contents are expressed as % of sediment dry weight, and the δ13C isotopic signature are reported as ‰ deviations from Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) standard. The relative precision of the SOC measurements was 5 % or better.

The SSA of sediments was determined for certain sediment depths (See Dataset in the Supplement) on an aliquot of the SOC samples, using the 5-point BET method (BET, N2 adsorption isotherm at 77K) via ASAP 2020 surface area analyser (Micromeritics, US). Prior to the SSA analysis, freeze-dried sediment samples were heated at 350 °C for 24 h to remove OC following the method described by Cui et al. (2022). The OC loadings (mg C m−2) are calculated as the ratio between SOC content (mg C g−1) and SSA (m2 g−1).

2.3 Extraction and calculation of OC–Fe

The OC–Fe associations were quantified in sediment cores from WGB1 (the shallowest station with hypoxic BW) and WGB2 (the deepest station with anoxic BW) which together bracket the environmental conditions present across the WGB, using the citrate-bicarbonate-dithionite (CBD) extraction method adapted from Mehra and Jackson (1958) described in Lalonde et al. (2012) . This extraction method targets all reactive Fe (FeR), while leaving clay minerals unaffected (Lalonde et al., 2012).

In brief, 250 mg of freeze-dried sediment were weighed and placed into a 50 mL Falcon tube. Then, 15 mL of the extraction solution (0.27 M trisodium citrate and 0.11 M sodium bicarbonate) were added, and the tube was placed in a water bath at 80 °C. Once the temperature was reached, 250 mg of sodium dithionite were introduced to the solution which was continuously agitated in the water bath to maintain a constant temperature. After 15 min, the extraction was stopped and the tube centrifuged (Eppendorf centrifuge 5804, Germany) at 3200 g for 10 min, after which the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 µ m PTFE filter and collected in 50 mL Falcon tubes. The sediment was subsequently rinsed with 10 mL of artificial seawater (0.235 M sodium chloride and 0.0245 M magnesium sulphate heptahydrate), centrifuged, and filtered. The rinsing step was repeated three times. The rinsing and the extraction solutions were combined and acidified with 100 µL trace-metal grade HCl (32 %) to prevent Fe reoxidation.

Parallel to the CBD extraction, a control extraction was performed to discriminate the portion of OC not associated with FeR, but solubilized due to the high ionic strength of the solution (Fisher et al., 2020). In the control extraction, trisodium citrate was substituted with 1.6 M of sodium chloride, and the sodium dithionite was substituted with 220 mg of sodium chloride to maintain the same ionic strength as the CBD solution. The extraction protocol mirrored the CBD extraction, with all steps described in (Table S1 in the Supplement). The Fe concentrations in the supernatant solutions were determined by ICP-OES (Varian, VISTA-MPX CCD, US) with an analytical precision of 5 %. Sediment leftovers from the extractions were frozen at −20 °C and then freeze dried prior to SOC analyses as described above.

The percentage of bulk OC associated with FeR (%OC–Fe) is calculated as the difference between the %OC left after the control extraction (%OCControl) and the %OC residual post CBD extraction (%OCCBD), normalized to the total OC in the bulk sediment (%OCBulk) before extractions as follow:

2.4 OC reactivity kand 210Pb-estimated OC age

The OC reactivity, approximated by the first-order decay rate constant k (yr−1), is derived from the volumetric sulphate reduction rates (SRR). The rate of OC mineralization Rmin (nmol cm−3 yr−1) at depth x (cm) can be calculated as:

where C(x) represents the OC concentration (nmol cm−3) at sediment depth x. These sediments are anoxic, unaffected by bioturbation, and sulphate SO is not depleted, so one can assume that all OC mineralization results from sulphate reduction. Contributions from denitrification, DNRA, manganese and iron reduction are negligible; however, it is important to note that the reported rates may slightly underestimate total reactivity:

The value of Rmin(x) can thus be approximated by the SRR, accounting for the 2 C for 1 S stoichiometry during sulphate reduction:

Since these WGB sediments are unbioturbated, the SOC age (yr) can be approximated from the 210Pb dating of each sediment depth. However, as the 210Pb dating quantifies the time since deposition at the sediment surface, it underestimates the actual age of the SOC (i.e., time since formation).

3.1 Organic carbon in Western Gotland Basin (WGB) sediments is highly reactive

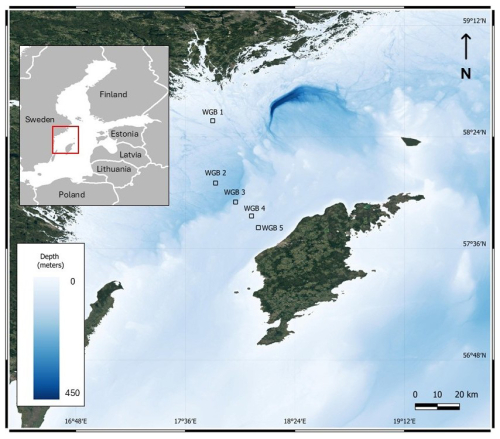

The sedimentary organic carbon (SOC) profiles (Fig. 2A–E) generally decrease with depth at all stations, but with distinct site-specific trends. At WGB2 and WGB3, the deepest stations (Table 1), surface SOC contents reach up to 20 wt %, while WGB1 shows lower surface values and a more gradual decline at depth. At WGB4, an increase of SOC at ∼ 5 cm depth may suggest a potential, localized input of refractory OC (possibly of terrestrial origin). Elevated SOC concentrations in the Baltic Sea generally stem from cyanobacteria, diatoms, and other phytoplankton blooms induced by nutrients inputs, as indicated by δ13C signatures and ratios of WGB1 and WGB2 sediments (Fig. S1 in the Supplement), reflecting autochthonous freshwater and marine inputs.

At WGB1, progressive δ13C depletion with depth and increasing indicate selective microbial degradation of labile, N-rich compounds (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). At WGB2, δ13C values fluctuate irregularly with depth (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). Such variability could, in principle, reflect changing rates of microbial SOC degradation, as isotopic fractionation during microbial metabolism generally enriches the residual organic matter in 13C. However, the δ13C and SRR profiles in WGB2 show no consistent covariation, indicating that variations in microbial activity are unlikely to be the primary driver of the δ13C pattern. Instead, the variations of δ13C, and SRR most likely reflect heterogeneity in the deposited material: certain layers may contain more reactive OC that transiently enhances microbial activity, whereas others consist of more degraded OC that experienced substantial mineralization during lateral transport. This interpretation aligns with the WGB sedimentation regime, where lateral transport involves repeated resuspension from shallow, erosive regions (e.g., WGB1) and redeposition in deeper, accumulating depocenters (e.g., WGB2; Nilsson et al., 2021). In addition to this transport, since the mid 1900's, enhanced nutrient loading in the central Baltic Sea has increased OC inputs, while damming of major rivers reduced sediment delivery and limited dilution of autochthonous OC, contributing to the heterogeneity of SOC profiles in WGB (Emeis et al., 2000; Leipe et al., 2011). The SRR depth profiles (Fig. 2F–J) show generally elevated activity in the surficial sediments, consistent with the distribution of SOC. Stations WGB2 and WGB3 exhibit the highest SRR values, but with contrasting depth trends: WGB3 displays markedly higher surface rates that decline steeply within the upper 5 cm, whereas WGB2 shows more moderate but relatively uniform SRR throughout the upper layers. This difference, despite broadly similar SOC depth profiles, suggests that SRR is influenced not only by SOC content but also by other factors such as organic matter quality and degradability, microbial community and porewater geochemistry.

Figure 2Sedimentary organic carbon SOC (A–E), and sulphate reduction rates (SRR) profiles (F–J) at all locations. Full and empty symbols are duplicate cores.

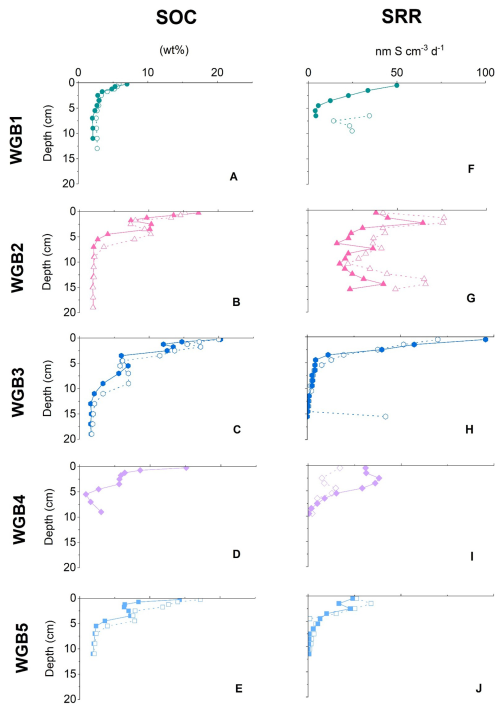

Generally, bulk OC reactivity approximated by the first-order decay constant k (yr−1) decreases with 210Pb-estimated OC age as the more reactive compounds are mineralized first, leaving behind the less reactive fractions (Middelburg et al., 1997). The k values we found in the WGB sediments range from 10−1 to 10−3 yr−1, consistent with previously reported values for sediments, that range from 100 to 10−6 yr−1 (Katsev and Crowe, 2015; Middelburg, 1989). These high OC reactivity values corroborate the very low OC burial efficiencies reported for the WGB (van de Velde et al., 2023). Katsev and Crowe (2015) demonstrated that the relationship between the OC reactivity and the OC age differs between OC exposed to O2 and OC mineralized under anoxic conditions (Fig. 3), consistent with evidence that OC mineralization efficiency increases with O2 exposure time (Hartnett et al., 1998; Hulthe et al., 1998). Because large parts of the WGB are long-term anoxic, the k values would be expected to follow the reactivity-age relationship derived for anoxic sediments. Intriguingly, however, most of the k values fall closer to the oxic reactivity-age trend line (Fig. 3). Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) for the anoxic trendline and the k vs. 210Pb-estimated OC age dataset is 0.68, while the RMSE for the oxic trendline was significantly lower at 0.45. This indicates that, overall, the sediment reactivity aligns more closely with the oxic trendline. Note, however, that the OC age estimated by the 210Pb method may be underestimated (see Sect. 2.4) which would shift our reactivity-age dataset further to the right toward the oxic trendline.

Importantly, the OC reactivity derived for oxic conditions in the compilation of Katsev and Crowe (2015) predominantly consisted of water column data, whereas their anoxic conditions were taken from sedimentary environments. A large fraction of the particulate organic matter is fragmented into smaller fractions during the sinking to the benthic environment and is exposed to microbes, zooplankton, and nekton that consume the more reactive fractions. Consequently, the remaining particulate organic matter reaching the sediment is comparatively less reactive than its water column counterpart and it is often found sorbed to mineral surfaces or within aggregates with the sediment particles (Arndt et al., 2013; Burdige, 2007). The high OC reactivity estimated in our study, despite anoxic conditions, suggests that the pattern observed by Katsev and Crowe (2015) could be driven by the interaction between OC and sedimentary particles, rather than a direct O2 effect. Indeed, the high OC reactivity in the WGB sediments could be explained by (i) a lack of physical protection through adsorption to sediment particles, and (ii) a lack of protection by interactions with Fe minerals. We explore these factors below.

Figure 3OC reactivity (k) versus 210Pb estimated sediment age (t) in logarithmic scales. Data are represented per station using different symbols; individual points represent different sediment depths at a given station. The two regression lines are from Katsev and Crowe (2015), where the dashed line is for anoxic conditions ), and the solid line is for oxic conditions .

3.2 OC loading and physical protection

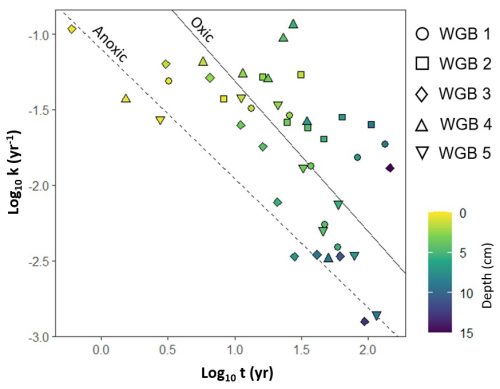

Because of the often observed positive correlation between SOC content and sediment specific surface area (SSA), SOC is assumed to be primarily associated with particle surfaces, which is consistent with the stabilization of OC through sorption to mineral surfaces (Goni et al., 2008; Keil et al., 1994). While this mechanism has been well documented in terrestrial settings (Blair and Aller, 2012; Goni et al., 2008), where sorption provides protection to inherently more refractory compounds such as lignin-rich material, it has also been demonstrated in marine sediments (Keil et al., 1994; Li et al., 2017; Mayer, 1994b). In latter case, sorption on mineral surfaces may act to stabilize more labile, phytoplankton-derived OC. Such physical protection presumably promotes OC burial, making OC loading an important proxy for the OC fate (albeit all OC included in the loading calculations is not necessarily adsorbed to mineral surfaces, Li et al. (2017); Mayer (1994b). Local environmental conditions determine the OC loading (Bianchi et al., 2018; Blair and Aller, 2012). Low OC loadings (<0.4 mg OC m−2) are indicative of frequently resuspended sediments that possibly undergo disaggregation and are exposed to O2 for prolonged periods, leading to efficient OC mineralization. OC loadings between 0.4 and 1 mg OC m−2 are typical for river-suspended sediments and those found downcore in shelf sediments respectively. High OC loadings (>1 mg OC m−2) are commonly observed in sediments from high-productivity regions such as upwelling zones or areas experiencing eutrophication, which have a high OC delivery relative to the detrital sediment input.

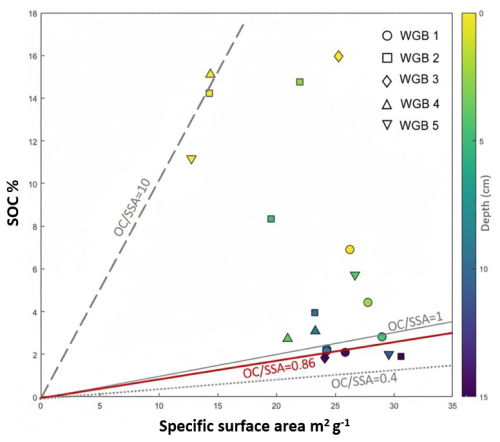

Figure 4Sedimentary organic carbon (SOC) content versus specific surface area (SSA). Stations are represented by symbols with filling colours indicating depth within profiles. Lines correspond to specific OC loadings (): 0.4, 1 and 10 mg OC m−2. The bold red line corresponds to the monolayer equivalent adsorption (0.86 mg OC m−2).

The very high OC loadings observed in the WGB surface sediments most likely reflect a combination of intense autochthonous OC inputs, stimulated by eutrophication, together with a limited role of mineral surfaces in constraining OC accumulation. OC loadings range from approximatively 2 mg OC m−2 in the hypoxic WGB1 to over 6 mg OC m−2 at other stations, peaking at around 10 mg C m−2 in WGB4 (Fig. 4). These values are comparable to those reported in upwelling regions or other settings with high productivity such as the Peruvian slope or Black Sea surface sediments (Mayer, 1994a). Enhanced nutrient loading and primary production in the Baltic Sea during the 20th century (Conley et al., 2009) likely contributed to these elevated values in surficial sediments, as increased deposition of autochthonous OC on particle surfaces was not supported by a proportional increase in mineral inputs. With depth, OC loading systematically declines across all stations, dropping below 1 mg C m−2 beneath 10 cm and falling below the monolayer equivalent adsorption threshold of 0.86 mg C m−2 at ∼ 15 cm (Mayer, 1994b). This downcore decrease parallels the sharp decline in both SOC concentrations and SRR (Fig. 2) indicating that high surficial OC loadings represent reactive organic pools that are efficiently degraded rather than being stabilized by mineral associations. Thus, the combined , SRR, and OC% patterns point to a system where microbial activity dominates over mineral protection in regulating OC preservation in WGB sediments.

While direct observations of the OC distribution on particle surfaces in the sediment are lacking in this study, it has been demonstrated that OC does not form uniform coatings or infillings on sediment particles; rather, it likely exists as discrete blebs on the mineral surface or as non-associated organic debris (Ransom et al., 1997). The latter were shown to disproportionately contribute to OC loading (Bianchi et al., 2018) and we hypothesize that they form a large portion of the OC present in our profiles. High SOC due to eutrophication, together with intense mineralization and limited mineral surface protection (likely saturated) explains both the exceptionally high OC loadings at the surface and their rapid decline with depth. This underscores that OC preservation in WGB sediments is governed by both historical input dynamics and post-depositional degradation processes, rather than mineral protection alone.

3.3 The rusty carbon sink

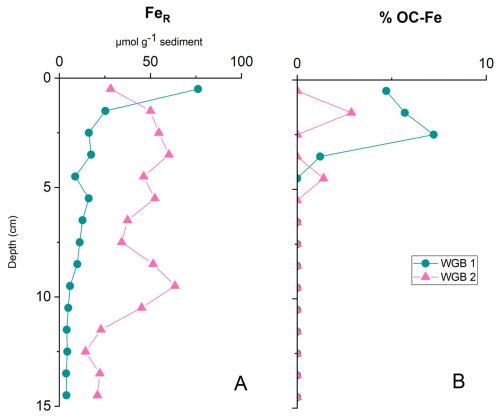

The very high OC loadings observed in WGB sediments (Sect. 3.2) indicate that mineral surfaces overall play a limited role in preserving OC from degradation. This interpretation is reinforced by the very low fraction of OC bound to FeR in the two stations tested (Fig. 5), compared to a global average for marine sediments of 15 %–20 % (Lalonde et al., 2012; Longman et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2018). At WGB1, FeR binds on average 1.25 % of total OC (ranging from 0 to ∼ 7 %OC–Fe), with OC–Fe associations restricted to the top 4 cm. The maximum of 7 %OC–Fe occurs near the surface and decreases with depth, consistent with reductive dissolution of Fe phases in OC–Fe associations. This strongly contrast with the observations in the Barents Sea where OC–Fe associations persist over millennia (Faust et al., 2021). WGB1 also shows the highest %OC–Fe values despite low concentrations of both SOC (average of 3.5 ± 1.3 %) and FeR (average of 14.7 µmol g−1, ranging from 3 to 76 µmol g−1). This suggests that the formation of OC–Fe associations is not solely controlled by FeR or SOC availability (Faust et al., 2021; Longman et al., 2021; Peter and Sobek, 2018; Sirois et al., 2018). Similar observations and conclusions have been drawn from Swedish fjord sediments where low and variable amounts of %OC–Fe with no relation with FeR nor SOC concentrations have been reported in Placitu et al. (2024).

Figure 5Downcore profiles of reactive iron (FeR; A) and fraction of organic carbon associated to FeR (%OC–Fe; B) at stations WGB1 and WGB2.

At WGB2, despite higher SOC (6.4 ± 4.7 %) and FeR (average of 40.3 µmol g−1, ranging from 14 to 63 µmol g−1) than in WGB1, only 0.28 %OC–Fe (ranging from 0 % to 2.8 %OC–Fe) is found. This is remarkable given that FeR concentrations are similar to those reported for other O2-depleted and eutrophic settings such as the Black Sea where FeR binds ∼ 15 % of the OC (Lalonde et al., 2012). The very low %OC–Fe at WGB2 may reflect the effects of repeated physical reworking and sediment redistribution prior to deposition in WGB2. Frequent resuspension and redeposition events can disrupt the OC–Fe associations by exposing particles to fluctuating redox conditions and mechanical disaggregation, as observed in mobile mud environments (Zhao et al., 2018). This process is consistent with the strong downcore variability in δ13C and SRR at WGB2 and with earlier evidence of sediment shuttling and lateral transport in the area (Nilsson et al., 2021). The persistence of FeR under anoxic and sulphidic conditions in WGB2 is intriguing. One potential explanation is the presence of Fe(II)-phosphate mineral phases such as vivianite, which have been well-documented in Baltic Sea sediments and can be solubilized during the CBD extraction (e.g. Dijkstra et al., 2018; Egger et al., 2015; van Helmond et al., 2020; Kubeneck et al., 2021).

Although the downcore variability in our measurements indicates that depth trends should be interpreted with caution, a speculative interpretation of this downcore trend could be that the build-up of H2S can reduce FeR thus destabilizing the OC–Fe associations (Chen et al., 2014), which might ultimately precipitate as OC–Fe-sulphide associations. However, this so called “black carbon sink” has so far only been reported in laboratory studies (Ma et al., 2022; Picard et al., 2019). Differences in the %OC–Fe could also be due to mineralogical variations within the FeR pool at depth, as the CBD extraction reduces and solubilizes a wide array of FeR, such as ferrihydrite, goethite, and lepidocrocite including Fe(II)-phosphates phases, all of which characterized by their small particle size, yet exhibiting large differences in SSA and surface reactivities towards OM moieties (Egger et al., 2015; Ghaisas et al., 2021). These characteristics determine the sorption efficiency, and therefore the extent of the OC–Fe associations. For instance, OC associations with more crystalline FeR minerals are believed to be less efficient in preserving organic matter from mineralization, creating mono or multi-layer sorption that are probably still accessible to microbial mineralization (Faust et al., 2021).

Taken together, these results indicate that Fe minerals contribute only marginally to the OC preservation in the WGB. While we cannot rule out that other mineral phases (e.g. clays, Al oxides) also provide sorption sites, the combination of very low %OC–Fe and high OC loadings strongly suggest that physical protection is very limited in WGB. The low %OC–Fe found in WGB1 and WGB2 potentially reflects both the decoupled delivery of FeR and OC and the absence of substantial terrestrial inputs of FeR that preferentially bind terrestrial organic matter. In the WGB, FeR is likely to enter the Baltic Sea via surface runoff and is redistributed via sediment resuspension as described in Nilsson et al. (2021), while most OC consists of autochthonous marine production (Fig. S1 in the Supplement) which likely limits the formation of OC–Fe associations. This decoupling of OC and FeR inputs in WGB could explain the limited amount of OC–Fe associations found across the WGB sediments.

Sediments in the WGB underly hypoxic and anoxic bottom waters, yet the reactivity of sedimentary OC is in line with previous estimates from oxic settings. Detailed analyses at two representative sites (WGB1 and WGB2) show limited potential for physical protection of OC by adsorption on mineral surfaces and association with Fe oxides in these sediments, demonstrated by high OC loadings and low amounts of OC–Fe associations. Together with consistently high sulphate reduction rates across the basin, these results suggest that anoxic conditions in the WGB do not necessarily result in a slowdown of OC mineralization. Instead, the significant degradation of OC under anaerobic conditions is likely facilitated by the limited physical protection of OC by mineral surface, which keeps a large portion of OC accessible to sulphate reducers. While our targeted dataset does not capture the full extent of spatial heterogeneity of the WGB, it nevertheless supports the view that mineral protection, rather than redox state alone, constitutes a critical control on the long-term burial of OC in marine sediments.

The datasets used in this study are available in the Zenodo repository (Placitu, 2025, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17174549).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-22-8065-2025-supplement.

Conceptualization: SP, SJvdV, SB; Field sampling: SP, SJvdV, AH, POJH; Formal analysis: SP; Writing – original draft: SP; Writing – review & editing: SP, SB, SJvdV, AH, ME, POJH; Funding acquisition: POJH, SB, SJvdV.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors would like to thank the crew of the University of Gothenburg RV Skagerak for technical assistance, Elizabeth Robertson and Rebecca James for help at sea and with sample analysis, and Marie Carlsson (Linköping University) for her work with the 210Po analysis.

The research leading to this manuscript was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (grant no. 2015-03717 to POJH), the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (grant no. 2535-20 to POJH), and the Belgian Federal Research Policy Office (grant no. RV/21/CANOE to SJV). AH was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO; project nr 1241724N). SP and SB acknowledge the support of the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FRS-FNRS PDR-T002019F).

This paper was edited by Tyler Cyronak and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Aller, R. C. and Aller, J. Y.: The effect of biogenic irrigation intensity and solute exchange on diagenetic reaction rates in marine sediments, Journal of Marine Research, 56, 905–936, https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/journal_of_marine_research/2296/ (last access: 15 December 2025), 1998.

Andrén, E., Andrén, T., and Kunzendorf, H.: Holocene history of the Baltic Sea as a background for assessing records of human impact in the sediments of the Gotland Basin, The Holocene, 10, 687–702, https://doi.org/10.1191/09596830094944, 2000.

Arndt, S., Jørgensen, B. B., LaRowe, D. E., Middelburg, J. J., Pancost, R. D., and Regnier, P.: Quantifying the degradation of organic matter in marine sediments: A review and synthesis, Earth-Science Reviews, 123, 53–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.02.008, 2013.

Barber, A., Lalonde, K., Mucci, A., and Gélinas, Y.: The role of iron in the diagenesis of organic carbon and nitrogen in sediments: A long-term incubation experiment, Marine Chemistry, 162, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2014.02.007, 2014.

Berner, R. A.: Burial of organic carbon and pyrite sulfur in the modern ocean; its geochemical and environmental significance, American Journal of Science, 282, 451–473, https://doi.org/10.2475/ajs.282.4.451, 1982.

Bianchi, T. S., Cui, X., Blair, N. E., Burdige, D. J., Eglinton, T. I., and Galy, V.: Centers of organic carbon burial and oxidation at the land-ocean interface, Organic Geochemistry, 115, 138–155, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2017.09.008, 2018.

Björck, S.: A review of the history of the Baltic Sea, 13.0–8.0 ka BP, Quaternary International, 27, 19–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/1040-6182(94)00057-C, 1995.

Blair, N. E. and Aller, R. C.: The Fate of Terrestrial Organic Carbon in the Marine Environment, Annual Review of Marine Science, 4, 401–423, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142717, 2012.

Burdige, D. J.: Preservation of Organic Matter in Marine Sediments: Controls, Mechanisms, and an Imbalance in Sediment Organic Carbon Budgets?, Chem. Rev., 107, 467–485, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr050347q, 2007.

Canfield, D. E.: Factors influencing organic carbon preservation in marine sediments, Chemical Geology, 114, 315–329, https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2541(94)90061-2, 1994.

Chen, C., Dynes, J. J., Wang, J., and Sparks, D. L.: Properties of Fe-Organic Matter Associations via Coprecipitation versus Adsorption, Environ. Sci. Technol., 48, 13751–13759, https://doi.org/10.1021/es503669u, 2014.

Conley, D. J., Björck, S., Bonsdorff, E., Carstensen, J., Destouni, G., Gustafsson, B. G., Hietanen, S., Kortekaas, M., Kuosa, H., Markus Meier, H. E., Müller-Karulis, B., Nordberg, K., Norkko, A., Nürnberg, G., Pitkänen, H., Rabalais, N. N., Rosenberg, R., Savchuk, O. P., Slomp, C. P., Voss, M., Wulff, F., and Zillén, L.: Hypoxia-Related Processes in the Baltic Sea, Environ. Sci. Technol., 43, 3412–3420, https://doi.org/10.1021/es802762a, 2009.

Cui, X., Mucci, A., Bianchi, T. S., He, D., Vaughn, D., Williams, E. K., Wang, C., Smeaton, C., Koziorowska-Makuch, K., Faust, J. C., Plante, A. F., and Rosenheim, B. E.: Global fjords as transitory reservoirs of labile organic carbon modulated by organo-mineral interactions, Science Advances, 8, eadd0610, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.add0610, 2022.

Dijkstra, N., Hagens, M., Egger, M., and Slomp, C. P.: Post-depositional formation of vivianite-type minerals alters sediment phosphorus records, Biogeosciences, 15, 861–883, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-861-2018, 2018.

Egger, M., Jilbert, T., Behrends, T., Rivard, C., and Slomp, C. P.: Vivianite is a major sink for phosphorus in methanogenic coastal surface sediments, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 169, 217–235, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2015.09.012, 2015.

Emeis, K.-C., Struck, U., Leipe, T., Pollehne, F., Kunzendorf, H., and Christiansen, C.: Changes in the C, N, P burial rates in some Baltic Sea sediments over the last 150 years – relevance to P regeneration rates and the phosphorus cycle, Marine Geology, 167, 43–59, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-3227(00)00015-3, 2000.

Faust, J. C., Tessin, A., Fisher, B. J., Zindorf, M., Papadaki, S., Hendry, K. R., Doyle, K. A., and März, C.: Millennial scale persistence of organic carbon bound to iron in Arctic marine sediments, Nat. Commun., 12, 275, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20550-0, 2021.

Fisher, B. J., Moore, O. W., Faust, J. C., Peacock, C. L., and März, C.: Experimental evaluation of the extractability of iron bound organic carbon in sediments as a function of carboxyl content, Chemical Geology, 556, 119853, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2020.119853, 2020.

Ghaisas, N. A., Maiti, K., and Roy, A.: Iron-Mediated Organic Matter Preservation in the Mississippi River-Influenced Shelf Sediments, Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 126, e2020JG006089, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JG006089, 2021.

Goni, M. A., Monacci, N., Gisewhite, R., Crockett, J., Nittrouer, C., Ogston, A., Alin, S. R., and Aalto, R.: Terrigenous organic matter in sediments from the Fly River delta-clinoform system (Papua New Guinea), Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface, 113, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JF000653, 2008.

Hall, P. O. J., Almroth Rosell, E., Bonaglia, S., Dale, A. W., Hylén, A., Kononets, M., Nilsson, M., Sommer, S., van de Velde, S., and Viktorsson, L.: Influence of Natural Oxygenation of Baltic Proper Deep Water on Benthic Recycling and Removal of Phosphorus, Nitrogen, Silicon and Carbon, Frontiers in Marine Science, 4, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00027, 2017.

Harris, D., Horwáth, W. R., and van Kessel, C.: Acid fumigation of soils to remove carbonates prior to total organic carbon or CARBON-13 isotopic analysis, Soil Science Society of America Journal, 65, 1853–1856, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2001.1853, 2001.

Hartnett, H. E., Keil, R. G., Hedges, J. I., and Devol, A. H.: Influence of oxygen exposure time on organic carbon preservation in continental margin sediments, Nature, 391, 572–575, https://doi.org/10.1038/35351, 1998.

Hedges, J. I. and Keil, R. G.: Sedimentary organic matter preservation: an assessment and speculative synthesis, Marine Chemistry, 49, 81–115, https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4203(95)00008-F, 1995.

Henrichs, S. M.: Early diagenesis of organic matter in marine sediments: progress and perplexity, Marine Chemistry, 39, 119–149, https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4203(92)90098-U, 1992.

Hulthe, G., Hulth, S., and Hall, P. O. J.: Effect of oxygen on degradation rate of refractory and labile organic matter in continental margin sediments, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 62, 1319–1328, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(98)00044-1, 1998.

Ingall, E. D. and Cappellen, P. V.: Relation between sedimentation rate and burial of organic phosphorus and organic carbon in marine sediments, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 54, 373–386, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(90)90326-G, 1990.

Jørgensen, B.: Bacteria and Marine Biogeochemistry, in: Marine Geochemistry, 169–206, https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-32144-6_5, 2006.

Jørgensen, B. B.: A comparison of methods for the quantification of bacterial sulfate reduction in coastal marine sediments: I. Measurement with radiotracer techniques, Geomicrobiology Journal, 1, 11–27, https://doi.org/10.1080/01490457809377721, 1978.

Katsev, S. and Crowe, S. A.: Organic carbon burial efficiencies in sediments: The power law of mineralization revisited, Geology, 43, 607–610, https://doi.org/10.1130/G36626.1, 2015.

Keil, R. G., Montluçon, D. B., Prahl, F. G., and Hedges, J. I.: Sorptive preservation of labile organic matter in marine sediments, Nature, 370, 549–552, https://doi.org/10.1038/370549a0, 1994.

Kristensen, E., Andersen, F. Ø., and Blackburn, T. H.: Effects of benthic macrofauna and temperature on degradation of macroalgal detritus: The fate of organic carbon, Limnology and Oceanography, 37, 1404–1419, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1992.37.7.1404, 1992.

Kristensen, E., Penha-Lopes, G., Delefosse, M., Valdemarsen, T., Quintana, C., and Banta, G.: What is bioturbation? The need for a precise definition for fauna in aquatic sciences, Marine Ecology Progress Series, 446, 285–302, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps09506, 2012.

Kubeneck, L. J., Lenstra, W. K., Malkin, S. Y., Conley, D. J., and Slomp, C. P.: Phosphorus burial in vivianite-type minerals in methane-rich coastal sediments, Marine Chemistry, 231, 103948, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2021.103948, 2021.

Lalonde, K., Mucci, A., Ouellet, A., and Gélinas, Y.: Preservation of organic matter in sediments promoted by iron, Nature, 483, 198–200, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10855, 2012.

LaRowe, D. E. and Van Cappellen, P.: Degradation of natural organic matter: A thermodynamic analysis, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 75, 2030–2042, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2011.01.020, 2011.

LaRowe, D. E., Arndt, S., Bradley, J. A., Estes, E. R., Hoarfrost, A., Lang, S. Q., Lloyd, K. G., Mahmoudi, N., Orsi, W. D., Shah Walter, S. R., Steen, A. D., and Zhao, R.: The fate of organic carbon in marine sediments – New insights from recent data and analysis, Earth-Science Reviews, 204, 103146, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103146, 2020.

Leipe, T., Tauber, F., Vallius, H., Virtasalo, J., Uścinowicz, S., Kowalski, N., Hille, S., Lindgren, S., and Myllyvirta, T.: Particulate organic carbon (POC) in surface sediments of the Baltic Sea, Geo-Mar. Lett., 31, 175–188, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00367-010-0223-x, 2011.

Li, Z., Wang, X., Jin, H., Ji, Z., Bai, Y., and Chen, J.: Variations in organic carbon loading of surface sediments from the shelf to the slope of the Chukchi Sea, Arctic Ocean, Acta Oceanol. Sin., 36, 131–136, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13131-017-1026-y, 2017.

Longman, J., Gernon, T. M., Palmer, M. R., and Manners, H. R.: Tephra Deposition and Bonding With Reactive Oxides Enhances Burial of Organic Carbon in the Bering Sea, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 35, e2021GB007140, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GB007140, 2021.

Longman, J., Faust, J. C., Bryce, C., Homoky, W. B., and März, C.: Organic Carbon Burial With Reactive Iron Across Global Environments, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 36, e2022GB007447, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GB007447, 2022.

Ma, W.-W., Zhu, M.-X., Yang, G.-P., Li, T., Li, Q.-Q., Liu, S.-H., and Li, J.-L.: Stability and molecular fractionation of ferrihydrite-bound organic carbon during iron reduction by dissolved sulfide, Chemical Geology, 594, 120774, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2022.120774, 2022.

Mayer, L. M.: Relationships between mineral surfaces and organic carbon concentrations in soils and sediments, Chemical Geology, 114, 347–363, https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2541(94)90063-9, 1994a.

Mayer, L. M.: Surface area control of organic carbon accumulation in continental shelf sediments, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 58, 1271–1284, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(94)90381-6, 1994b.

Megonigal, J. P., Hines, M. E., and Visscher, P. T.: 8.08 – Anaerobic Metabolism: Linkages to Trace Gases and Aerobic Processes, in: Treatise on Geochemistry, edited by: Holland, H. D. and Turekian, K. K., Pergamon, Oxford, 317–424, https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043751-6/08132-9, 2003.

Mehra, O. P. and Jackson, M. L.: Iron Oxide Removal from Soils and Clays by a Dithionite-Citrate System Buffered with Sodium Bicarbonate, Clays Clay Miner., 7, 317–327, https://doi.org/10.1346/CCMN.1958.0070122, 1958.

Middelburg, J. J.: A simple rate model for organic matter decomposition in marine sediments, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 53, 1577–1581, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(89)90239-1, 1989.

Middelburg, J. J. and Levin, L. A.: Coastal hypoxia and sediment biogeochemistry, Biogeosciences, 6, 1273–1293, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-6-1273-2009, 2009.

Middelburg, J. J., Soetaert, K., and Herman, P. M. J.: Empirical relationships for use in global diagenetic models, Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 44, 327–344, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0637(96)00101-X, 1997.

Nilsson, M. M., Kononets, M., Ekeroth, N., Viktorsson, L., Hylén, A., Sommer, S., Pfannkuche, O., Almroth-Rosell, E., Atamanchuk, D., Andersson, J. H., Roos, P., Tengberg, A., and Hall, P. O. J.: Organic carbon recycling in Baltic Sea sediments – An integrated estimate on the system scale based on in situ measurements, Marine Chemistry, 209, 81–93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2018.11.004, 2019.

Nilsson, M. M., Hylén, A., Ekeroth, N., Kononets, M. Y., Viktorsson, L., Almroth-Rosell, E., Roos, P., Tengberg, A., and Hall, P. O. J.: Particle shuttling and oxidation capacity of sedimentary organic carbon on the Baltic Sea system scale, Marine Chemistry, 232, 103963, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2021.103963, 2021.

Papaspyrou, S., Kristensen, E., and Christensen, B.: Arenicola marina (Polychaeta) and organic matter mineralisation in sandy marine sediments: In situ and microcosm comparison, Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 72, 213–222, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2006.10.020, 2007.

Peter, S. and Sobek, S.: High variability in iron-bound organic carbon among five boreal lake sediments, Biogeochemistry, 139, 19–29, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-018-0456-8, 2018.

Picard, A., Gartman, A., Cosmidis, J., Obst, M., Vidoudez, C., Clarke, D. R., and Girguis, P. R.: Authigenic metastable iron sulfide minerals preserve microbial organic carbon in anoxic environments, Chemical Geology, 530, 119343, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2019.119343, 2019.

Placitu, S.: Limited physical protection leads to high organic carbon reactivity in anoxic Baltic Sea sediments, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17174549, 2025.

Placitu, S., van de Velde, S. J., Hylén, A., Hall, P. O. J., Robertson, E. K., Eriksson, M., Leermakers, M., Mehta, N., and Bonneville, S.: Limited Organic Carbon Burial by the Rusty Carbon Sink in Swedish Fjord Sediments, Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 129, e2024JG008277, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JG008277, 2024.

Ransom, B., Bennett, R. H., Baerwald, R., and Shea, K.: TEM study of in situ organic matter on continental margins: occurrence and the “monolayer” hypothesis, Marine Geology, 138, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-3227(97)00012-1, 1997.

Sirois, M., Couturier, M., Barber, A., Gélinas, Y., and Chaillou, G.: Interactions between iron and organic carbon in a sandy beach subterranean estuary, Marine Chemistry, 202, 86–96, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2018.02.004, 2018.

Ståhl, H., Tengberg, A., Brunnegård, J., Bjørnbom, E., Forbes, T. L., Josefson, A. B., Kaberi, H. G., Hassellöv, I. M. K., Olsgard, F., Roos, P., and Hall, P. O. J.: Factors influencing organic carbon recycling and burial in Skagerrak sediments, J. Mar. Res., 62, 867–907, https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/journal_of_marine_research/66 (last access: 15 December 2025), 2004.

van de Velde, S. J., Hidalgo-Martinez, S., Callebaut, I., Antler, G., James, R. K., Leermakers, M., and Meysman, F. J. R.: Burrowing fauna mediate alternative stable states in the redox cycling of salt marsh sediments, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 276, 31–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2020.02.021, 2020.

van de Velde, S. J., Hylén, A., Eriksson, M., James, R. K., Kononets, M. Y., Robertson, E. K., and Hall, P. O. J.: Exceptionally high respiration rates in the reactive surface layer of sediments underlying oxygen-deficient bottom waters, Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 479, 20230189, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2023.0189, 2023.

van Helmond, N. A. G. M., Robertson, E. K., Conley, D. J., Hermans, M., Humborg, C., Kubeneck, L. J., Lenstra, W. K., and Slomp, C. P.: Removal of phosphorus and nitrogen in sediments of the eutrophic Stockholm archipelago, Baltic Sea, Biogeosciences, 17, 2745–2766, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-2745-2020, 2020.

Yao, Y., Wang, L., Hemamali Peduruhewa, J., Van Zwieten, L., Gong, L., Tan, B., and Zhang, G.: The coupling between iron and carbon and iron reducing bacteria control carbon sequestration in paddy soils, CATENA, 223, 106937, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.106937, 2023.

Zhao, B., Yao, P., Bianchi, T. S., Shields, M. R., Cui, X. Q., Zhang, X. W., Huang, X. Y., Schröder, C., Zhao, J., and Yu, Z. G.: The Role of Reactive Iron in the Preservation of Terrestrial Organic Carbon in Estuarine Sediments, Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 123, 3556–3569, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JG004649, 2018.