the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Perturbation increases source-dependent organic matter degradation rates in estuarine sediments

Klaas G. J. Nierop

Bingjie Yang

Stefan Schouten

Gert-Jan Reichart

Peter Kraal

Despite a relatively small surface area on Earth, estuaries play a disproportionally important role in the global carbon cycle due to their relatively high primary production and rapid organic carbon processing. Estuarine sediments are highly efficient in preserving organic carbon and thus often rich in organic matter (OM), highlighting them as important reservoirs of global blue carbon. Currently, estuaries are facing intensified human disturbance, one of which is sediment dredging. To understand estuarine carbon dynamics and the impact of perturbations, insights into sediment OM sources, composition, and degradability are required. We characterized the sediment OM properties and oxidation rates in one of the world's largest ports, the Port of Rotterdam, located in a major European estuary. Using a combination of OM source proxies and end-member modeling analysis, we quantified the contributions of marine (10 %–65 %), riverine (10 %–60 %), and terrestrial (10 %–65 %) OM inputs across the investigated transect, with salinity ranging from 32 (marine) to almost 0 (riverine). Incubating intact sediment cores from two contrasting sites (marine versus riverine) suggested that OM degradation rates in marine sediments were about four times higher than those in riverine sediments, which was also observed during a 35 d subaerial bottle incubation experiment with mixed surface sediment. Moreover, subaerial incubation of mixed sediment showed a two- to three-fold increase in OM degradation rates compared to intact core incubation, highlighting that perturbation and subsequent enhanced oxygen availability can substantially boost OM degradation. By combining detailed quantitative characterization of estuarine OM properties with degradation experiments under varying conditions, the results further our understanding of the factors that govern OM degradation rates in (perturbed) estuarine systems. Ultimately, this contributes to constraining the impact of human perturbation on OM cycling in estuaries and its role in the carbon cycle.

- Article

(3559 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2432 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Estuaries are highly dynamic aquatic systems that are influenced by simultaneous marine, riverine, and terrestrial inputs. In this transition zone, strong and variable gradients exist in hydrodynamic and sediment properties, resulting in dynamic and complex cycles of key elements such as carbon through coupled physical, chemical, and biological processes (Barbier et al., 2011; Dürr et al., 2011; Laruelle et al., 2010). Despite representing only 0.03 % of the surface area of marine systems, estuaries are estimated to release approximately 0.25 Pg carbon annually into atmosphere on a global scale, which is equivalent to 17 % of the air-water CO2 gas exchange of the entire open ocean (Bauer et al., 2013; Li et al., 2023). Additionally, estuarine sediments store large amounts of organic carbon (Macreadie et al., 2019; McLeod et al., 2011); due to high productivity and high sedimentation rates, carbon burial rates in estuaries are up to one order of magnitude higher than forest soils and three orders of magnitude higher than in open ocean sediments (Kuwae et al., 2016). Their disproportionally large importance in the global carbon cycle highlights the need to improve our understanding of carbon dynamics in estuarine systems.

Organic matter (OM), a fundamental component of sediment, plays a key role in sediment carbon fluxes and sequestration. Degradation of OM contributes to the release of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4). This is a dynamic process that proceeds through a series of enzymatic reactions involving different organisms, oxidants, and intermediate compounds. Studies have pointed out the importance of OM characteristics in influencing the rate and extent of OM degradation (Burd et al., 2016; Burdige, 2007; LaRowe and Van Cappellen, 2011). For instance, extensively degraded OM and biopolymers such as cellulose and lignin are less susceptible to degradation than freshly produced nitrogenous compounds (Arndt et al., 2013). Estuarine systems have diverse terrestrial and aquatic OM sources, exhibiting varying degrees of degradability (Canuel and Hardison, 2016). Moreover, interactions between OM and other components (organic or inorganic) during transportation, deposition, and mineralization can alter OM characteristics. Processes such as condensation, (geo)polymerization and mineral association increase OM resistance to degradation, thereby promoting OM preservation (Wakeham and Canuel, 2006).

Sediment OM degradation is also influenced by ambient conditions at the sediment-water interface and in the sediment (Arndt et al., 2013; Burd et al., 2016; Burdige, 2007; LaRowe and Van Cappellen, 2011). The degradation pathway follows the sequential utilization of the terminal electron acceptors (TEAs), typically in the order of O2, NO NO, Mn (IV), Fe (III) and SO, with a progressive decrease in energy yield down the redox ladder. The availability of these TEAs is greatly influenced by the depositional environment. Estuaries are highly dynamic systems with strong and shifting salinity (i.e. sulfate) gradients exist. This results in strong spatial variability in OM degradation pathways and carbon dynamics (Cao et al., 2021). Specifically, large fluctuations in salinity and thus sulfate (SO) availability between sites will affect CH4 emissions because sulfate-driven methane oxidation provides a highly effective CH4 filter in surface sediments (e.g. Egger et al., 2018; Lovley and Phillips, 1986). Moreover, compilation of field data reveals that organic carbon burial efficiency varies substantially in space because the availability and exposure time of TEAs are influenced by environmental factors such as sedimentation rate (Arndt et al., 2013; Freitas et al., 2021). Estuaries are often characterized by relatively high sedimentation rates, with supply of riverine material that settles under low flow velocities at the river mouths as well as large inputs of (re)suspended marine matter from the coastal zone (Hutchings et al., 2020). Oxygen transport into the sediment is sufficiently low relative to the flux of reactive organic carbon to these sediments to maintain very shallow oxygen penetration depths, on the scale of micro- to millimeters (Burdige, 2012). By notably reintroducing O2 to OM previously buried in oxygen-limited environments, sediment disturbance caused by natural processes (e.g. storm-induced mixing events, bioturbation) and human activities (e.g. dredging, bottom trawling) can change sediment redox chemistry and thereby have a profound effect on OM degradation pathways and burial efficiency (Aller, 1994).

Although estuaries have been widely studied from an ecological perspective, large variation in OM properties and cycling processes within and across estuarine systems contributes to the uncertainty in quantifying their significance in the global carbon cycle. This uncertainty is partially due to the highly diverse OM sources and properties in estuarine systems. Many studies of estuarine OM sources use bulk proxies such as the weight ratio of total organic carbon to total nitrogen (C N ratio) and their stable isotope ratios (δ13Corg and δ15N; Canuel and Hardison, 2016; Carneiro et al., 2021; Cloern et al., 2002; Middelburg and Nieuwenhuize, 1998). In other studies, OM sources have been investigated by identifying biomarker compounds associated with specific sources and transformation processes. For example, the branched and isoprenoid tetraether (BIT) index, based on the relative abundance of terrestrially and/or freshwater-derived branched glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraether (GDGT) versus marine-derived isoprenoid GDGT crenarchaeol, was adopted to quantify the relative contribution of terrestrial OM in sediments (Herfort et al., 2006; Hopmans et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2010; Strong et al., 2012). Some studies focused on macromolecular organic matter (MOM) composition in sediments to identify OM sources (Kaal et al., 2020; Nierop et al., 2017). Lignin, an important constituent of vascular plant MOM, has proved to be a useful tracer of vascular plant inputs to estuarine/coastal margin sediment (Bianchi and Bauer, 2012; Buurman et al., 2006; Fabbri et al., 2005; Hedges and Oades, 1997; Kaal, 2019). Furthermore, the relationship between OM source and degradability can be intricate, which inhibits the quantitative understanding of estuarine OM degradation.

Understanding the processing of OM within estuaries takes on further importance because many estuarine systems are intensively altered by human activities (Arndt et al., 2013; Heckbert et al., 2012; Holligan and Reiners, 1992). To increase or maintain waterway navigability, dredging is commonly practiced in many coastal regions and rivers worldwide. More than 600 million m3 of dredged material is generated annually just in Western Europe, China, and the USA (Amar et al., 2021). While the dredged sediments are often treated as waste and disposed of at sea, there is a growing trend of reusing dredged sediments on land, for instance in beach nourishment, habitat restoration, and land reclamation (Brils et al., 2014). However, this impacts organic matter degradation and subsequent CO2 release from dredged materials in currently poorly understood ways, with oxygen exposure potentially leading to enhanced carbon remineralization (LaRowe et al., 2020). Given the need for sediment dredging and sustainable management of these materials (van de Velde et al., 2018), it is of great importance to understand to what extent anthropogenic sediment perturbations affect OM processing in and carbon emissions from estuarine sediments.

In this study, we investigate the spatial variability in OM content and properties and relationships between OM source, composition, and degradability along a salinity gradient in the profoundly disturbed Port of Rotterdam estuarine environment of the Rhine-Meuse delta system. Given the frequent dredging activities in the study area, which hosts a globally major port, we aim to understand the impact of sediment dredging and its potential land applications on carbon dynamics. We used a combination of bulk OM proxies, BIT index, macromolecular organic matter (MOM) composition analysis, as well as end-member modelling to understand OM sources and composition. Furthermore, organic matter degradation rates were estimated both in 8 h sediment core incubation (mimicking in situ condition) and 37 d bottle incubations with mixed surface sediments under atmospheric conditions (representing subaerial application of dredged sediment). This study shows that variability in OM sources and subsequently molecular properties, as well as perturbation (i.e. introduction of oxygen), have important effects on OM degradation rates, providing important implications for estuarine sediment management strategies.

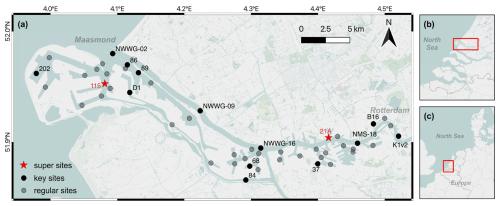

2.1 Study area and sample collection

The study area is located in the northern part of the Rhine-Meuse estuary (Fig. 1), spanning from Rotterdam city to the Maasmond. This area representing a transitional environment from riverine to marine is heavily urbanized and hosts one of the world's largest ports, the Port of Rotterdam (PoR). Every year, large amounts of sediment are deposited in the harbor from both rivers as well as the North Sea (Kirichek et al., 2018). The water channel maintenance and harbor expansion lead to an increasing need for sediment dredging throughout the PoR. Due to higher sedimentation rates and the demand for deeper navigation channels at the river mouth, dredging is more frequently performed in the western (marine) part (e.g. site 115) than in the eastern (riverine) part (e.g. 21A; Kirichek et al., 2018). Currently, over 10 million m3 of dredged materials are generated from the PoR annually, most sediments (classified as clean) being relocated to the shallow North Sea, while approximately 10 % (classified as contaminated) being stored subaerially in a holding basin in the PoR area (Kirichek et al., 2018).

Figure 1(a) The investigated study area and sampling sites. Sediments from all 49 sites were subjected to bulk analyses (e.g. grain size, TOC, TN) as detailed in Sect. 2.2. Sediments from 13 key sites were used for lipid and MOM analysis as detailed in Sect. 2.3 and 2.4, respectively. Sediment cores from two super sites were used in a whole-core incubation experiment as detailed in Sect. 2.5. (b) The location of investigated study area in the Rhine–Meuse estuary. (c) The location of Rhine-Meuse estuary in Western Europe. Map created using QGIS software. Basemap courtesy of Mapbox.

Bulk sediments were collected from 49 selected locations throughout the study area in the summer of 2021. These sites were selected from over 300 monitoring sites in the Port of Rotterdam to represent the full spectrum of depositional conditions in the main waterway and adjacent harbor areas from marine to riverine (Fig. 1). One sediment core from each site was collected using a gravity corer (inner diameter: 9 cm). Once on deck, materials in the corer (down to ∼ 50 cm depth) were emptied into 5 L polypropylene buckets that were closed and stored in the fridge at 4 °C. These samples, later referred as bulk sediments, were further processed within a week after collection at the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ) on Texel, the Netherlands. In addition to bulk sediments, intact sediment cores were collected in summer 2022 upon revisiting two strongly contrasting sites (referred as `super sites' in Fig. 1) representing marine (site 115, salinity 29) and riverine (site 21A, salinity 5) end-members in the PoR area. The intact sediment cores were immediately cooled, transported back to the NIOZ and used in whole-core incubation experiments (see Sect. 2.5) within 5 h after collection.

2.2 Sample processing and analysis

Bulk sediments from each of the 49 sites were thoroughly mixed using a spatula in the buckets. Approximately 40 mL of wet sediment were transferred into 50 mL polypropylene centrifuge tubes (Falcon) and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 min (Hermle Z 446). In a N2-purged glove bag, the porewater was immediately filtered through a 0.45 µm nylon syringe filter (MDI). Salinity was estimated by comparing the porewater sodium (Na) concentration to the average seawater sodium concentration and salinity in the North Sea (IJsseldijk et al., 2015; Steele et al., 2010). For Na analysis, the porewater was diluted around 900 times in 1 M double-distilled HNO3 and analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Thermo Scientific, Element 2).

The centrifuge tubes with wet sediment residues after centrifugation were purged with N2 and stored at −20 °C in N2-purged, gas-tight Al-laminate bags to prevent oxidation. To prepare for subsampling, the sediment residues were thawed overnight in a N2-purged glove bag (Coy Laboratories) and subsequently homogenized. One portion of wet sediment residue (∼ 1 g) was mixed with 50 mL of 3 g L−1 sodium pyrophosphate solution and gently shaken to disaggregate particles. Particle size distribution was determined using a Coulter laser particle sizer (Beckman Coulter), from which percentages of clay (0–2 µm), silt (2–63 µm), sand (63–2000 µm) and the median particle size (D50) were calculated.

Approximately 10 g of wet sediment residue was freeze-dried (Hetosicc freeze dryer) for 72 h and manually ground with an agate pestle and mortar, and further subsampled for carbon and nitrogen (CN) analysis. One subsample of the freeze-dried sediment (∼ 10 mg) was directly used for measuring total nitrogen (TN) and stable nitrogen isotope composition (expressed as δ15N, relative to atmospheric nitrogen) by a CN elementary analyzer (Thermo Scientific, FLASH 2000) coupled to a Delta V Advantage isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Another freeze-dried subsample (∼ 0.5 g), firstly treated with 1 M HCl to remove carbonates, was used for measuring total organic carbon (TOC) and stable carbon isotope composition (expressed as δ13Corg, relative to Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite). Certified laboratory standards (acetanilide, urea, and casein) were used for calibration with each sample. Precision and accuracy for standards and triplicate samples were ±0.3 ‰ for δ13Corg and δ15N, and the relative standard deviation (RSD; standard deviation/mean) was < 10 % for TOC and TN.

2.3 Lipid extraction and analysis

Sediments from 13 key locations (Fig. 1), selected to cover the full river-marine salinity transect, were used for lipid and MOM analyses. Freeze-dried and homogenized sediments (2–10 g) were ultrasonically extracted with dichloromethane (DCM) : methanol (2:1, v:v) five times. For each sample, extracts obtained from the five steps were combined. The total extract was separated over an Al2O3 column into an apolar, neutral and polar fraction using hexane:DCM (9 : 1, v:v), hexane:DCM (1 : 1, v:v) and DCM:methanol (1 : 1, v:v), respectively. The polar fractions containing glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers (GDGTs) were dried under N2, dissolved in hexane:propanol (99 : 1, v:v), and filtered using a 0.45 µm PTFE filter. This fraction was subsequently analyzed with ultra-high performance liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS) on an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC coupled to an Agilent 613MSD according to (Hopmans et al., 2016). The isoprenoid and branched GDGTs were detected by scanning for their [M + H]+ ions. The BIT index was calculated according to (Hopmans et al., 2004).

2.4 Macromolecular organic matter (MOM) isolation and analysis

The sediment residues, remaining after lipid extraction, from the 13 samples from key locations were dried under N2. To isolate MOM, dried sediment residue (2–3 g) was transferred into 50 mL centrifuge tubes and decalcified with 30 mL 1 M HCl for 4 h, later rinsed twice with 25 mL milli-Q water (18 MΩ). After centrifugation and decanting the supernatant, 15 mL 40 % HF (analytical grade, Merck) was added and shaken for 2 h at 100 rpm. The solution was diluted with milli-Q water to 50 mL and left standing overnight, after which the solution was decanted to a high-density polyethylene plastic container designated for HF waste. A volume of 15 mL 30 % HCl was added and subsequently diluted with milli-Q water to 50 mL. After shaking for 1 h and centrifugation, the solution was decanted, and the residues were washed with milli-Q water three times to neutralize pH and subsequently freeze-dried. The supernatant of all steps was collected in the HF waste container. Samples were desulfurized using activated copper pellets in DCM. Suspensions were stirred overnight after which the copper pellets and DCM were removed. The sample residue, containing the macromolecular organic matter (MOM), was air-dried prior to the analysis.

The analysis of MOM was conducted at Utrecht University using the pyrolysis-gas chromatograph-mass spectrometry method previously described in (Nierop et al., 2017). In short, the isolated MOM was pyrolyzed on a Horizon Instruments Curie-Point pyrolysis unit. The pyrolysis unit was connected to a Carlo Erba GC8060 gas chromatograph and the products were separated by a fused silica column (CP-Sil5, 25 m, 0.32 mm i.d.) coated with CP-Sil5 (film thickness 0.40 µm). The column was coupled to a Fisons MD800 mass spectrometer. Pyrolysis products were identified using a NIST library or by interpretation of the spectra, by their retention times and/or by comparison with literature data. Quantification was performed according to (Nierop et al., 2017).

2.5 Whole-core sediment incubation

Triplicate intact sediment cores collected from two strongly contrasting sites (marine site 115 vs. riverine site 21A) were used for whole-core incubation. These sites represent relatively intensively dredged marine and riverine areas, respectively, that contribute significantly to the total annual dredged sediment volume in the PoR. Prior to incubation, cores were carefully manipulated to have ∼ 15 cm of undisturbed top sediment (primary zone of diagenesis) with ∼ 20 cm of overlying water (achieving a ∼ 1 : 1 water:sediment volume ratio which represents a balance between sensitivity in measuring fluxes while avoiding excess accumulation of (inhibiting) reactants in the overlying water and ensuring a small fraction of the overlying water is replaced by discrete sampling). After confirming that the sediment surface was not disturbed, an oxygen sensor spot (Presens) was attached to the inner wall of the core tube (5 cm from the top) to monitor O2 in the overlying water. The cores, capped at the bottom and open at the top, were submerged in bottom water from the corresponding site in an incubation tank. Stirrers were placed in each core to mix the overlying water (at ∼ 1 rpm) and the cores were left open overnight to equilibrate. The water in the tank was kept fully oxygenated by sparging with air using an aquarium pump. Temperature in the room was maintained at the measured in situ bottom water temperature (19 °C). At the start of the incubation, the cores were capped with gas-tight lids with an outlet to sample bottom water from the core and an inlet to replace sampled volume with site water from a 20 L reservoir. Over the course of an eight-hour incubation period, 30 mL of bottom water (equivalent to 2.3 % of total overlaying water volume) were extracted at pre-determined time intervals of 0, 1.5, 3.5, 5, 6.5, and 8 h. The dissolved O2 concentration in the overlying water in each core was measured every five minutes using the sensor spots and a Presens OXY-4 SMA meter with fiber optic cables, operated using Presens Measurement Studio 2. Immediately after sampling, the water samples were filtered using 0.45 µm nylon syringe filters for dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), total alkalinity (TA) and dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN: NH, NO, NO) analysis, while an unfiltered subsample was retained for methane (CH4) analysis.

The DIC samples were diluted 10 times in N2-purged 25 g L−1 sodium chloride solution without headspace and analyzed within 24 h on a continuous flow analyzer (QuAAtro, Seal Analytical). The TA samples were kept at 5 °C without treatment and measured within a week using the same analyzer. The DIN samples were stored at −20 °C and later analyzed on a TRAACS 800+ continuous flow analyzer. For CH4, 12 mL of bottom water was directly transferred into a 12 mL Exetainer vial (Labco), immediately poisoned with ∼ 0.25 mL of saturated zinc chloride solution and capped with a butyl rubber stopper ensuring no headspace was present. Dissolved CH4 concentration was determined using a headspace technique (Magen et al., 2014). Prior to the measurement, 1 mL of N2 headspace was injected through the stopper in each Exetainer vial while a needle allowed the equivalent volume of sample to escape, after which the samples were equilibrated for a week. Headspace CH4 concentrations were then measured on a gas chromatograph (Thermo Scientific FOCUS GC) equipped with a HayeSep Q Packed GC Column and a flame ionization detector. A calibration curve was made using a certified 1000 ppm CH4 standard (Scott Specialty Gases Netherlands B.V.). From the measured CH4 concentration in the headspace, the total dissolved CH4 in the bottom water was calculated using the equations in (Magen et al., 2014) with the Bunsen coefficient (Yamamoto et al., 1976). Benthic fluxes of DIC and CH4 were calculated using the concentration changes of solutes in the bottom water of closed cores during the incubation period, as determined by linear regression analysis of the individual time series. Total organic matter mineralization was partitioned into aerobic and anaerobic contributions. Assuming a 1:1 stoichiometric relationship between O2 consumption rate and DIC production rate for aerobic mineralization, the aerobic fraction was calculated from measured O2 consumption, and the remaining OM-derived DIC production was attributed to anaerobic mineralization.

2.6 Subaerial incubation of dredged sediment

To investigate OM degradability under oxygen exposure during dredged sediment processing, open-air bottle incubations were conducted in triplicate for six sediments from sites that covered contrasting depositional and sedimentary conditions within the research area: three marine (115, 86, NWWG-02; Fig. 1a) and three riverine (21A, B16, K1v2; Fig. 1a), with differing sediment texture (silt-rich and sand-rich) in both groups. To obtain minimally altered sediment in which the water content could be accurately and rapidly adjusted, and to ensure reproducibility, we used freeze-dried and homogenized sediments from the six sites, in triplicate. The freeze-dried sediment was transferred into 330 mL borosilicate glass bottles, resulting in a thin sediment layer (< 5 mm). Artificial rainwater (composition in Table S1) was added to achieve a water content of 60 % water-filled pore space (assuming the same porosity after rewetting; calculation provided in the Supplement), which is a water content optimal for soil respiration (Fairbairn et al., 2023). The rewetted sediments were incubated in the dark at room temperature (20 °C). The CO2 emission rates were measured on day 2, 6, 9, 16, 23, 30 and 37; in the later stages in incubations, the rates declined significantly and became relatively stable after around one-month incubation, and the experiment was terminated. On the day of measurement, bottles were sealed with rubber stoppers tightened with aluminum crimp caps for approximately 3 h. We measured the CO2 concentrations in the headspace immediately after the bottles were capped and approximately 3 h later. The CO2 accumulation in the headspace of each bottle during these 3 h was used to calculate a CO2 emission rate. For the rest of the time, bottles were kept open to the atmosphere. The moisture level was maintained once a week and varied by less than 10 % from the target value.

The CO2 measurement for the subaerial incubation was conducted by withdrawing a volume of 150 µL headspace gas using a 250 µL glass, gas-tight syringe (Hamilton). The headspace sample was immediately injected into a gas chromatograph (GC, Agilent, 8890 GC system) equipped with a Jetanizer and a flame ionization detector. Gases were carried by helium and separated by a Carboxen-1010 PLOT analytical column (Sigma-Aldrich). Calibration was conducted by using certified reference CO2 gas (Scott specialty gases, Air Liquide, Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

To determine the percentage of degraded TOC over time, we firstly calculated the cumulative amount of CO2 emission and then normalized it to the total amount of organic carbon in the incubated sediments, calculated from the dry sediment mass and its TOC content. The cumulative CO2 emission was obtained by integrating the CO2 emission rate over time. For days when CO2 emission rates were not measured, the rates were estimated using spline interpolation. The integration and normalization were performed using the “AUC” (area under curve) function in RStudio.

2.7 End-member modelling of OM sources

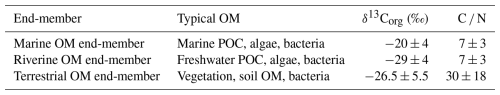

Contributions of three major OM end-members (marine, riverine, and terrestrial) to the 49 sediments were quantified based on δ13Corg and C N ratio using a Bayesian mixing model, MixSIAR (Stock et al., 2018). Anthropogenic OM such as petroleum and coal products were not considered as they typically have a much higher C N ratio (Tumuluru et al., 2012) compared to the investigated samples here (mostly < 20), thus suggesting a limited contribution. Input from industrial and chemical waste is considered being minimal because > 90 % of sediment is regarded as clean/safe with organic contaminants below their national intervention values (Kirichek et al., 2018). We did not include sewage OM and agricultural wastes as separate end-members due to their high variability in δ13Corg (−28 ‰ to −23 ‰; Shao et al., 2019) and C N ratio (Chow et al., 2020; Puyuelo et al., 2011; Szulc et al., 2021), and values largely overlaps with those of the considered three end-members. The model incorporates the common ranges of three OM end-members in coastal environments (Table 1) and employs Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation to sample from the posterior distribution. The distribution provides estimates of the mean contribution with standard deviation. The model was run in RStudio with package “MixSIAR” integrated into the JAGS program.

3.1 Bulk geochemical feature of sediments

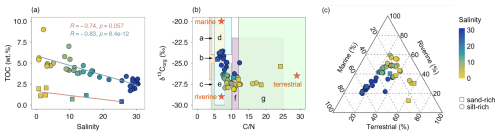

The PoR sediments were mostly (42 out of 49 samples) silt-rich with D50 smaller than 20 µm. A salinity gradient was observed in the study area increasing from approximately 0 at the most eastern part (Rotterdam city) to approximately 32 at the river mouth in the west. We observed a decrease in TOC content with increasing salinity (Fig. 2a). The silt-rich sediments generally contained more than 2.5 wt % TOC, with significantly lower TOC contents in the sand-rich sediments (p < 0.01, Student's t-test). The weight ratio of C N was between 5 and 13 for most samples (45 out of 49), and the corresponding δ13Corg was in the range of −29 ‰ to −23 ‰ (Fig. 2b). Despite a weak correlation between C N ratio and δ13Corg (0.38, Pearson), both properties showed (moderately) strong trends against salinity (C N ratio: 0.66; δ13Corg: R= 0.68, Pearson; Fig. 2b).

Figure 2Bulk geochemical properties of 49 sediment samples from the PoR. (a) TOC vs. salinity for both silt-rich (D50 < 20 µm) and sand-rich (D50 > 50 µm) sediments. (b) δ13Corg and the weight ratio of C N in sediments along salinity gradient in contrast to the typical δ13Corg and C N ranges for OM from coastal sediments in literature (Bianchi and Bauer, 2012; Finlay and Kendall, 2007; Lamb et al., 2006): a marine POC, b bacteria, c freshwater POC, d marine algae, e freshwater algae, f soil OM, g C3 terrestrial plants. Orange star symbols represent the mean values of three OM sources used in end-member analysis. (c) The contributions (%) of marine, riverine and terrestrial OM using a mixing model. The standard deviation (10 %–25 %) is provided in the Supplement (Table S2).

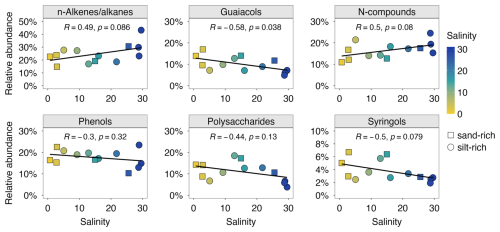

3.2 Flash pyrolysis products of MOM

Pyrolysis of isolated MOM produced hundreds of pyrolysis compounds. The identified pyrolysis products are listed in Supplementary Information (Table S3). They were divided into nine groups based on the chemical characteristics, following the approach detailed in Nierop et al. (2017). Here in Fig. 3, we present the relative abundance of six MOM pyrolysate groups along the salinity gradient, including n-alkenes/alkanes, guaiacols, N-compounds, phenols, polysaccharide-derived products, and syringols. The other three groups: phytadienes and pris-1-ene were only minor constituents (relative abundance < 5 %), and aromatics showed a negligible correlation with salinity (−0.1 < R < 0.1, Pearson; Supplement Fig. S1). With increasing salinity, we observed an increase in the relative abundance of n-alkenes/alkanes and N-compounds, while guaiacols, phenols, polysaccharides, and syringols decreased. The correlations were generally moderate or weak, as suggested by the magnitude of the correlation coefficient (−0.6 < R < 0.6, Pearson). Additionally, the correlation coefficients between the identified MOM pyrolysate groups and other bulk sediment properties (i.e. D50, C N, δ13Corg) were also weak (see Fig. S2).

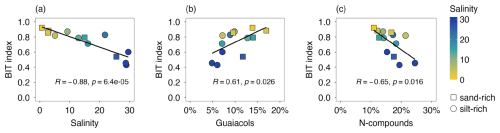

3.3 BIT index

Crenarchaeol and branched GDGTs were detected in sediments from all 13 investigated sites. The calculated BIT index ranged between 0.43 and 0.92 (Fig. 4a). A strong negative correlation was observed between BIT index and salinity (, Pearson) and between BIT index and δ13Corg (0.83, Pearson). In contrast, the correlations with MOM pyrolysis products were in general weak or moderate (−0.6 < R < 0.6, Pearson; Fig. S2), except for guaiacols and N-compounds (Fig. 4b and c). Additionally, we did not observe a significant difference between sand-rich and silt-rich sediments in BIT index values (p > 0.5, Student's t-test).

3.4 Benthic fluxes on intact sediment cores

During the whole-core incubation, the O2 concentration in the overlying water decreased linearly from around 90 % to 60 % air-saturation for both the high salinity location (115, salinity 29, later referred as “marine” location) and the low salinity location (21A, salinity 5, later referred as “riverine” location; Fig. S2). At the same time, concentrations of DIC and CH4 in the overlying water increased linearly with time (Fig. S3). Benthic O2 consumption and DIC release rates showed no significant differences between two contrasting locations (p > 0.05, Student's t-test), on average around 30 and 122–158 mmol m−2 d−1, respectively (Fig. 5a, b). However, DIC was released into the overlying water at a much higher rate, 4–5 times larger than O2 consumption rate. Correcting the DIC flux for contributions not associated with OM degradation (i.e. CaCO3 dissolution) as described in the supplementary information provided us with an estimate of the DIC flux from OM degradation (DICOM) which accounted for 88 %–97 % of the total DIC flux (Fig. 5c). When normalized to TOC to correct DICOM for differences in bulk TOC content, the DIC flux at 115 was about four times higher than at site 21A (Fig. 5d). Additionally, the CH4 efflux was one to two orders of magnitude smaller than the O2 and DIC fluxes and showed significant differences between two contrasting locations: the CH4 efflux at the river location was more than five times higher compared to the marine location (Fig. 5e).

Figure 5Benthic fluxes of dissolved O2 (a) and DIC (b) determined from whole-core incubation. Positive and negative rates represent efflux (from sediment into overlying water) and influx (from overlying water into sediment), respectively. The contribution of OM degradation to benthic DIC fluxes is shown in panel (c) and further normalized by sediment TOC in panel (d). Panel (e) shows benthic CH4 fluxes. Error bars represent standard deviations from triplicate core incubations. Other measured fluxes (e.g. DIN, total alkalinity) are available in Fig. S4.

3.5 Subaerial carbon emissions from bulk sediments

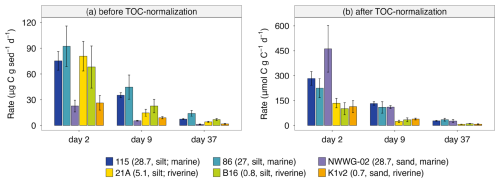

During the aerobic incubation experiment, CO2 accumulation was detected during the 3 h rate measurements for all timesteps. The CO2 emission rate, expressed as µg C g−1 d−1, was the highest at the start of the incubation. Rates dropped drastically in the first two weeks and then stabilized after day 25. Here we present carbon emission rates at three timesteps representing the initial stage, declining stage, and stable stage (Fig. 6). The silt-rich sediments showed both higher emission rates throughout the incubation period (up to 120 µg C g−1 d−1) and stronger decreases in rate over time (more than 60 µg C g−1 d−1), compared to sand-rich sediments (maximum rate around 35 µg C g−1 d−1; Fig. 6a). The TOC-normalized carbon emission rates were higher (up to three times) in the three marine sediments (salinity 27–28) compared to the three riverine sediments (salinity 0–5) throughout the experiment (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6Carbon emission rates in aerobic incubation at day 2, day 9 and day 37 from six sediments. Note the different scales and units for the y-axis for carbon emission rates before TOC-normalization (a) and after TOC-normalization (b). Site information (i.e. salinity, sediment texture, and marine/riverine location within the PoR) is given in brackets in the legend.

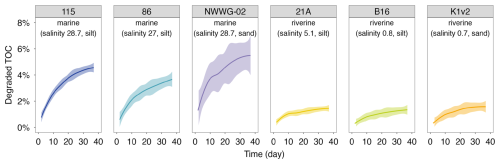

Figure 7The percentage of degraded TOC over time in aerobic incubation experiments. The shading areas represent the 95 % confidential interval for the fitted locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) curves.

The decreasing trend of CO2 emission rate was also reflected in the cumulative percentage of degraded TOC over time (Fig. 7), which increased fast initially and stabilized towards the end of the incubation experiment. After the 37 d incubation period, the amount of degraded TOC ranged from 1 % to 7 % for the investigated sites. Additionally, the percentage of degraded TOC was 2–4 times higher in sediments from marine locations than those in river locations, consistent with the differences in carbon emission rates (Fig. 6b).

4.1 Organic matter content, source and composition in estuarine sediments

The PoR sediments are characterized by relatively high TOC contents compared to the North Sea surface sediments (0.03–2.79 wt %; Wiesner et al., 1990), but in the range of Dutch coastal sediments (0–9.8 wt %; Stronkhorst and Van Hattum, 2003) or other harbor systems such as the Port of Hamburg (2–7.6 wt %; Zander et al., 2020). The high carbon content arose from high productivity and rapid burial of OM under high sedimentation rates; oxygen penetration is limited in rapidly accumulating, organic-rich sediment, and thus most OM breakdown occurs via relatively slow, anaerobic processes (Schulz and Zabel, 2006). Moreover, the fine sediment texture observed at most investigated sites limits oxygen diffusion and provides more sorption surface for OM (Keil et al., 1994), both contributing to the preservation of sedimentary OM and thus high TOC content compared to sandy sediment. This is expressed in the relatively low TOC content (0–2.5 wt %) of the coarser-grained sediments shown in Fig. 2a. Besides the clear impact of grain size on OM content, a general decreasing trend in sediment TOC contents from river to marine area of the PoR sediments was observed, in line with previous work on estuarine sediment OM (Strong et al., 2012). The relatively low OM content in sediment from the marine-dominated sites in part arises from the large input (up to 5.7 million t yr−1) in this area of repeatedly resuspended, OM-poor coastal sediment transported by strong tide and waves (Cox et al., 2021). More frequent dredging activities at the marine sites may also contribute to the lower OM content (Fig. 2a), as also witnessed in other coastal sediments (Aller et al., 1996). Furthermore, moving downstream from the riverine to the marine part of estuarine systems, the contribution of OM-rich riverine sediment not only decreases, but continuing OM degradation in this transported sediment further diminishes the amount of riverine OM (Bianchi et al., 2018; Freitas et al., 2021).

The OM burial and degradation are not only affected by the sediment dynamics as described above, but also by the source and inherent properties of the OM. The δ13Corg and C N ratio have been widely used to assess OM sources in coastal environments (Canuel and Hardison, 2016; Lamb et al., 2006; Li et al., 2021; Middelburg and Nieuwenhuize, 1998). The OM in the estuarine ecosystems can originate from multiple sources, and the typical ranges of δ13Corg and C N ratio for the common OM sources are indicated in Fig. 2b. The trends in δ13Corg and C N ratio suggest that OM in the PoR sediments is derived from a mixture of marine, riverine and terrestrial OM that are sourced from algae, bacteria, soil OM, and terrestrial plants, the relative contribution of these sources being a function of depositional conditions (riverine versus marine) also reflected by salinity (Fig. 2b). The observed δ13Corg values (−29 ‰ to −23 ‰) and their trend against salinity are similar to those in the broader Rhine estuary reported in earlier work by (Middelburg and Herman, 2007), suggesting that intense sediment reworking in connection with harbor expansion over the last 15 years has had little impact on sediment OM sources. Furthermore, the range in observed δ13Corg values is lower than that reported for temperate marine OM (−18 ‰ and −22 ‰; Thornton and McManus, 1994), reflecting a significant non-marine OM source even under nearly marine conditions at the river mouth. Quantification of the different sources using end-member modelling similarly indicates that the dominant OM source shifts with depositional environment: terrestrial OM in the most river-dominated locations (up to 65 %, salinity < 5), freshwater OM in the river-sea transitional area (∼ 45 %, 5 < salinity < 25), and marine OM in the river-mouth area (up to 65 %, salinity > 25).

Regarding the range of and trend in C N values, it is important to note that the value is subject to OM-specific alterations during sediment diagenesis: for higher plant litter, the C N ratio decreases during decomposition, while for aquatic detritus the C N ratio increases during degradation (Hedges and Oades, 1997; Wakeham and Canuel, 2006). These opposing diagenetic trajectories can result in a convergence of C N ratios of terrestrial and aquatic detritus (Middelburg and Herman, 2007). This may explain the observation that bulk sediments at many of the investigated sites in the PoR research area have C N ratios near the upper limit of the typical range for freshwater algae (∼ 8) or POC (∼ 10), or around the lower limit of the typical range for C3 plants (∼ 12, Fig. 2b). Compared to the C N ratio, the BIT index is thought to be less sensitive to diagenetic effects (Hopmans et al., 2004). This proxy indicates a predominant riverine and/or terrestrial source of the sedimentary OM (Schouten et al., 2013). The BIT values from this study are in line with the values previously determined by Herfort et al. (2006) in sediment at Maassluis (0.74–0.82; close to NWWG-09, Fig. 1), while they are much higher than those determined in coastal sediments of the southern North Sea (0.02–0.25; Herfort et al., 2006), highlighting the sharp transition in OM composition between estuarine and coastal systems and the importance of non-marine OM throughout the harbor system.

The source proxies presented above (δ13Corg, C N, BIT) indicate a strong terrestrial and riverine OM signature across the salinity gradient in the PoR study area, with a considerable marine contribution at the river mouth. The pyrolysis products from MOM offer additional insights into sediment OM sources and composition. Guaiacols and syringols are pyrolytic markers of terrestrial OM, as they are characteristic structural moieties of lignin, a typical biopolymer of higher plants. Their relative abundance together (7 %–28 %) falls within the reported lignin fractions (3 %–57 %) for various coastal aquatic environments (Brandini et al., 2022; Burdige, 2007; Kaal et al., 2020). Although having multiple potential sources, the markers of polysaccharides in the investigated samples showed strong positive correlations with both guaiacols (R= 0.77, Pearson) and syringols (R= 0.83, Pearson), suggesting they were mainly derived from terrestrial higher plants. The decreasing trends of these markers (relative abundance 10 %–40 %) with increasing salinity, well aligned with δ13Corg and BIT index, further support the decreasing importance of terrestrial OM input towards the river mouth. In contrast, N-compounds showed strong negative correlations with both guaiacols (0.84, Pearson) and syringols (0.81, Pearson), suggesting a non-terrestrial OM origin such as protein from algal detritus and chitin from various crustaceans (Nierop et al., 2017). n-Alkenes/alkanes, negatively correlated with (terrestrial) polysaccharide-derived products (0.78, Pearson; Fig. S2), were probably from non-terrestrial sources like algaenan (de Leeuw et al., 2006). The other detected pyrolysis products constituted a major fraction (> 50 %) but most correlated with all mentioned source proxies moderately or poorly (−0.5 < R < 0.5, Pearson; Fig. S2), thus are less effective provenance proxies because they originate from multiple sources.

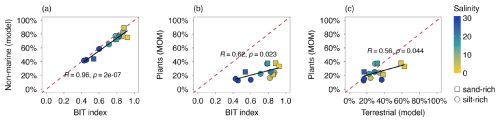

All proxies and analytical techniques have their strengths and weaknesses in determining OM sources. Here, we obtain further insight into MOM characteristics by exploring the relationships between different independent OM proxies and the end-member modelling results. There is a strong agreement between the BIT index and the modelled non-marine OM contribution (R= 0.96, Pearson; Fig. 8a), indicating that both approaches agree with respect to the relative contribution of terrestrial sources (plants, rivers, soils) to the sedimentary OM pool. The contribution to the MOM pool by lignin-derived products, likely representing remains of higher plants, was up to 40 % (Fig. 8b) and correlated strongly with BIT index (R= 0.62, Pearson). However, the weak slope in the scatter plot of BIT and plant-MOM suggests that plant-derived OM was a lesser indicator of changes in OM composition and reactivity in the harbor area. There was overall good agreement between the plant-derived contribution from chemical MOM analysis and end-member modelling (Fig. 8c), indicating that mixing models based on bulk OM parameters can provide valuable information about OM composition in dynamic coastal settings.

Figure 8Scatter plots of proxies for OM source: (a) BIT index vs. non-marine OM contribution (i.e. terrestrial and riverine input from the three end-member modelling), (b) modelled terrestrial OM contribution vs. plant-derived MOM pyrolysis products (i.e. sum of guaiacols, syringols, polysaccharide-derived products), (c) BIT index vs. plant-derived MOM pyrolysis products (i.e. sum of guaiacols, syringols, polysaccharide-derived products). The red dashed lines are 1:1 curves and the black lines are the linear regression fitting curves.

The terrestrial OM fraction modelled from C N and δ13Corg showed a positive correlation with plant-derived MOM pyrolysis products (Fig. 8c). Most data points seem to lie around the 1 : 1 curve except for two sand-rich outliers. However, interpreting their relationship in Fig. 8c is challenging because of the complexity in assigning MOM pyrolysis products to terrestrial-derived OM in estuarine environments. Phenols and N-compounds, partially derived from terrestrial OM, are not included in the presented MOM-determined contribution here. On the other hand, pyrolysis of algal material also produces polysaccharide-derived products (Stevenson and Abbott, 2019), which can lead to overestimation of MOM-determined terrestrial contribution. Nevertheless, this study suggests using bulk proxies (C N, δ13Corg) in combination with biomarker proxies (BIT index, MOM pyrolysis products) can provide a more complete picture of OM composition in highly dynamic systems like estuaries.

4.2 Organic matter degradation: rates and pathways

In the 8 h whole-core incubation experiment, oxygen consumption was mostly due to OM mineralization; the upward diffusive fluxes of reduced species (e.g. Fe2+, HS−) that can react with oxygen represented a negligible oxygen sink at the sediment-water interface (< 1 % of total oxygen uptake; calculation detailed in the Supplment). The measured benthic O2 consumption rates in the PoR sediments (33±6 mmol m−2 d−1) were similar to the reported rates in coastal sediments in the North Sea (22.1±0.6 mmol m−2 d−1; Neumann et al., 2021) and other human-influenced estuarine sediments (27–82 mmol m−2 d−1; Kraal et al., 2013). In estuarine systems, high primary production and shallow water depth (here 13–25 m) lead to deposition of a substantial amount of freshly produced OM, contributing to the high aerobic OM degradation rates. Furthermore, the whole-core incubation showed similar O2 consumption rates between sediment types. However, TOC-normalized carbon emission rates from OM degradation – measured as DIC in the whole-core incubation and CO2 in the subaerial bottle incubation experiment – were higher in marine sediments compared to riverine sediments (Figs. 5, 6). Here, the DICOM flux, which more broadly represents OM degradation in the surface sediment as it includes anaerobic OM degradation pathways, was normalized to TOC in order to compare between sites with strongly differing surface-sediment TOC contents (2.2 wt % for site 115 wt % vs. 5 wt % for site 21A). The results indicate that short-term oxic respiration rates (Fig. 5a), driven by rapid degradation of freshly deposited (algal) OM at the sediment-water interface, were similar between sites. Furthermore, OM degradation rates may have been affected by (similar) limitation of O2 supply rather than carbon availability. By contrast, overall (Fig. 5d) and long-term (Fig. 6b) OM degradation in the riverine sediment was 3–4 times slower than in the marine sediment, the former being characterized by a higher proportion of more recalcitrant OM sources. This suggests a link between OM composition and “quality” (rather than quantity) and the CO2 release potential from (dredged) estuarine sediment. Sediment from site 115 likely received a greater supply and burial of freshly produced (N-rich) algal OM, due to a faster burial rate (10–15 cm yr−1) than at riverine site 21A (< 10 cm yr−1; Cox et al., 2021). Riverine sediments (e.g. 21A), however, were richer in eroded soil OM (Fig. 8), which is typically more recalcitrant and N-depleted than freshly produced algal OM.

Regarding the role of estuaries in carbon cycling, a crucial transition in anaerobic OM degradation pathways is the onset of methanogenesis, which occurs when other TEAs have become depleted. Due to a lower salinity and thus a shallowing of the sulfate-methane transition zone (Kuliński et al., 2022), sediment from a river location (21A; salinity 5) exhibited an eight-time larger CH4 efflux (Fig. 5c) compared to the marine location (115; salinity 29) despite of less degradable OM with a stronger terrestrial signature (Fig. 2) as evidenced by the above-described lower OM mineralization rates relative to TOC content. Similar spatial variability of benthic CH4 fluxes as a function of salinity was documented in other estuaries but with rather different values (0.2–19 mmol m−2 d−1; Gelesh et al., 2016; Li et al., 2021; Middelburg et al., 2002). Note that the benthic fluxes measured here do not directly translate into atmospheric CO2 and CH4 emissions, as various processes (e.g. carbonate system equilibria, CH4 oxidation) act on the speciation and concentration of these greenhouse gases released from the sediment. Nevertheless, estuaries are considered as hotspots for both CO2 and CH4 emissions into atmosphere (Li et al., 2023; Middelburg et al., 2002). Therefore, elucidating how in addition to OM content the source and composition as well environmental conditions during OM degradation control the magnitude and speciation of carbon release from estuarine sediment is important to better constrain the role of estuaries in global carbon cycling.

4.3 The impact of perturbation on organic matter degradation

Sediment dredging and its further management, such as relocation on land, often alter OM degradation conditions substantially by reintroducing O2. In principle, aerobic degradation is more effective than anaerobic degradation as aerobic oxidation has a relatively high energy yield, especially compared to sulfate reduction (Hansen and Blackburn, 1991). This is reflected in the whole-core incubation results, where aerobic mineralization confined in the uppermost few-millimeter-thick sediment layer (Revsbech et al., 1980) accounted for 25 %–30 % of the total OM-derived DIC production across the entire 15 cm sediment core. By manually perturbing sediments and exposing them to atmospheric oxygen in subaerial incubations, we found that the initial (day 2) TOC-normalized carbon emission rate (283±42 and 134±29 µmol C g C−1 d−1 for 115 and 21A, respectively; Fig. 6b) increased to 2–3 times of that in undisturbed whole-core incubation (158±61 and 41±12 µmol C g C−1 d−1 for 115 and 21A, respectively; Fig. 5d). These findings agree with a slurry incubation experiment under contrasting redox conditions using Dutch coastal sediments conducted by Dauwe et al. (2001), which showed that the mineralization rate under aerobic conditions was faster than anaerobic conditions by up to one order of magnitude. Furthermore, the increase in carbon emission rate was more pronounced in the riverine sediment (21A) with a three-fold increase after perturbation, compared to the marine sediment (115) with a two-fold increase. We attribute this to the stronger terrestrial, recalcitrant signature of OM in the riverine part of the investigated harbor area. (Hulthe et al., 1998) suggested that the impact of redox conditions and specifically oxygen availability is greatest for relatively recalcitrant OM; fresh, labile OM is degraded relatively rapidly under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Therefore, the difference in the observed rate increase following sediment perturbation may be attributed to the more active enzymatic catalysis involved in the degradation of terrestrial OM, such as lignin, cellulose, and tannins (Hedges and Oades, 1997), compared to freshly produced marine OM was more predominant.

These OM source-dependent differences in OM degradation rates were expressed across the six investigated sites: the TOC-normalized carbon emission rates were over 100 % higher in marine sediments (115, 86, NWWG-02) than riverine sediments (21A, B16, K1v2) at almost all timesteps (Fig. 6b). This observed difference was supported by the OM end-member analysis: sediments near the river mouth (115, 86, NWWG-02) were composed of more than 50 % marine OM and less than 20 % terrestrial OM, whereas sediments from the river side (21A, B16, K1v2) were dominated (> 70 %) by non-marine OM (Fig. 2c, Table S2). The faster degradation rate of marine OM, such as algae, which was reported to be up to 10 times faster than terrestrial OM (Guillemette et al., 2013), likely explains the higher TOC-normalized carbon emission rates in marine sediments. We note that sample treatment for the subaerial bottle incubation experiment, i.e. freeze-drying and rewetting, may have reduced overall microbial activities and thus OM degradability, but previous studies indicate that such an effect is likely limited (He et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2020) and does not affect the overall conclusions regarding the role of OM source and reactivity in shaping CO2 emission kinetics.

In addition to the degradation rate, the extent of OM degradation is also affected by the OM source and composition. By the end of the subaerial incubation experiment, marine sediments (115, 86, NWWG-02) exhibited 2–4 times larger fractions of degraded TOC than riverine sediments (21A, B16, K1v2; Fig. 7). Despite a lower TOC content, marine sediments contained a higher percentage of fresher and more labile OM, thus resulting in a larger biodegradation fraction after 37 d of subaerial incubation. A majority of the annual dredged sediment volume is marine (∼ 77 %; Kirichek et al., 2018) and, consequently, dredging mostly perturbs sediments with relatively labile OM and high potential CO2 emission rates. Interestingly, sand-rich sediment NWWG-02 exhibited a notably larger biodegradable OM fraction (up to 7 %; Fig. 7), highlighting sediment texture may play an important role besides OM sources. Silt-rich sediment can contain 20 times more mineral-associated OM than sand-rich wetland soils (Mirabito and Chambers, 2023). This mineral-associated OM, physically protected by inorganic matrices from mineralization, was suggested to play a key role in lasting carbon sequestration globally (Georgiou et al., 2022; Keil et al., 1994).

Despite variations in the fractions of degraded TOC, more than 90 % of the organic carbon remained in the sediments by the end of the 37 d aerobic incubation experiments (Fig. 7). This aligns with other studies where a majority fraction (> 80 %) of organic carbon remained preserved in sediments or soils after prolonged incubation periods ranging from weeks to years (Gebert et al., 2019; Haynes, 2005; Plante et al., 2011). The predominant fraction of sediment OM being less degradable on such timescales fits well with the relatively large amounts (∼ 50 %) of pyrolysis products derived from (terrestrial) polysaccharide, n-alkenes/alkanes from algaenan, guaiacols and syringols from lignin. However, (Zander et al., 2022) indicated that the slow degradation of the majority of OM could also be attributed to its association with sedimentary minerals. Importantly, the remaining OM, while resistant to degradation over weeks to years, is still potentially degradable on longer timescales and relevant for the carbon footprint of perturbing estuarine sediment over decades. While the results in this study indicate that reintroduction of O2 leads to a short-lived increase in estuarine OM degradation rates, the degradation can still be stimulated under certain conditions. For instance, the addition of fresh, readily degradable OM, known as priming, was reported to increase the degradability of old, recalcitrant OM by 59 % (Huo et al., 2017). This highlights that the organic carbon turnover rate is rather complex and can vary markedly under different sediment management practices.

4.4 Implications and future perspectives

Estuaries are sites of high OM production and understanding OM processes within these regions is key to quantify organic carbon budgets along the river-estuary-coastal ocean continuum (Canuel and Hardison, 2016). In the PoR, sediment OM degradation (i.e. degradation rate and biodegradable pool) exhibited a large spatial variation (marine vs. riverine), demonstrated in both whole-core and subaerial incubation experiments. This spatial variability likely reflected a shift of OM composition, where marine sediment was richer in freshly produced, easily degradable OM of algal origin. Similar source-dependent OM degradation patterns were also observed in other coastal systems (e.g. the Elbe estuary; Zander et al., 2022). However, the spatial distribution of OM may vary between different estuaries, driven by many environmental factors (e.g. hydrological conditions, nutrient availability, land use). Combining multiple independent proxies (e.g. C N, δ13Corg, biomarkers) can improve our ability to understand the source, transport and fate of OM in (perturbed) estuarine environments. Degradation of OM is responsible for nutrient cycling, oxygen balance between the aquatic system and sediment, and most early diagenetic processes (Middelburg et al., 1993). Therefore, recognizing and differentiating OM reactivity of varying sources can help to refine the biogeochemical processes and minimize the uncertainty in estimating OM mineralization and preservation efficiency in both field and theoretical frameworks.

Anthropogenic perturbation like dredging within the coastal zone have greatly intensified in recent decades. It is therefore important to explore the impact of such activities, specifically dredging and potential sediment reuse, on the fate of carbon stored in estuarine sediments. The growing trend of sediment reuse on land (e.g. beach nourishment, dike construction) introduces subaerial conditions that can boost carbon mineralization rates (2–3 times), as shown in the open-air incubations. Current practice with unpolluted PoR dredged sediment is relocation in the shallow North Sea, which is likely to lead to less CO2 emission than open-air incubation because (1) burial of dredged sediment at sea limits exposure to O2 and thus degradation rates and (2) buffering of released CO2 in the water column by conversion to HCO. However, extensive resuspension in the coastal zone will increase O2 exposure and CO2 release into seawater results in a pH decrease, and as such the reactivity of dredged material as determined in this study is also relevant to inform about the environmental impact of disposal at sea. Overall, balancing sediment valorization with its associated carbon footprint is of importance in determining the suitable sediment management strategies.

Methane, a strong greenhouse gas, is often oversaturated in the OM-rich coastal sediments, favoring CH4 bubble formation. Most CH4 is trapped below the sulfate-methane transition zone, within which anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) coupled to SO removes approximately 71 % of the CH4 in marine sediments (Gao et al., 2022). Dredging, similar to the natural forms of sediment erosion (Hulot et al., 2023), can disrupt the functioning of this AOM filter and destabilize riverbed/seabed, leading to a temporary CH4 escape via enhanced diffusion and ebullition (Maeck et al., 2013; Nijman et al., 2022). However, in the long term, exposing sediments to oxygen is expected to inhibit methane production and emissions (Nijman et al., 2022). Whether dredging and the following sediment processing will shift the estuarine sediment from a carbon sink into a carbon source is dependent on the pristine sediment carbon dynamics and the specifications of human disturbance. Indubitably, estuaries will remain vulnerable to human pressure and climate change. These alternations will in return influence the important drivers of the estuarine, further affecting the balance between OM degradation and preservation (Heckbert et al., 2012).

The PoR sediments, like many other coastal sediments, exhibited relatively high OM content and reactivity due to the high primary production and rapid sedimentation in these shallow aquatic systems. Organic carbon in marine sediments degraded up to 5 times faster than that in riverine sediments under both intact and perturbed conditions. This variability was suggested to reflect differences in OM composition: marine sediments were richer in recently produced, labile algal OM. By contrast, riverine sediments contained larger amounts of eroded, more recalcitrant soil and plant-derived OM. Additionally, OM degradation rates were 2–3 times higher in the open-air, disturbed sediment incubations than the intact whole-core incubations. This suggested that perturbation triggered by sediment dredging and processing can mobilize the sequestered sediment organic carbon. Despite only 1 %–7 % of organic carbon was released after 37 d open-air incubation, certain favorable conditions may still promote degradation of the remaining organic carbon. With the growing need for dredging and other coastal sediment reworking, it is therefore of great importance to consider the sensitivity of carbon in sediment management practices on relevant timescales and in the context of the fast-changing environmental conditions.

The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-23-995-2026-supplement.

GW conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, conducted the investigation and formal analysis, created visualizations, and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. KN and BY contributed to the investigation and formal analysis, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. SS and GJR reviewed and edited the manuscript. PK supervised the project, contributed to the conceptualization and methodology, acquired funding, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and agreed on the final version of the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This study is part of the project “Transforming harbor sediment from waste into resource”. We extend our gratitude to the Port of Rotterdam Authority, particularly Marco Wensveen and Ronald Rutgers, and Heijdra Milieu Service B.V. for their assistance with sediment collection. We thank Julia Gebert from Delft University of Technology for her stimulating discussion. We appreciate the scientific and technical staff from NIOZ Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research for their analytical support.

This research has been supported by the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (grant no. TWM.BL.019.005).

This paper was edited by Edouard Metzger and reviewed by Tom Jilbert and two anonymous referees.

Aller, R. C.: Bioturbation and remineralization of sedimentary organic matter: effects of redox oscillation, Chem. Geol., 114, 331–345, https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2541(94)90062-0, 1994.

Aller, R. C., Blair, N. E., Xia, Q., and Rude, P. D.: Remineralization rates, recycling, and storage of carbon in Amazon shelf sediments, Continental Shelf Research, 16, 753–786, https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4343(95)00046-1, 1996.

Amar, M., Benzerzour, M., Kleib, J., and Abriak, N. E.: From dredged sediment to supplementary cementitious material: characterization, treatment, and reuse, International Journal of Sediment Research, 36, 92–109, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsrc.2020.06.002, 2021.

Arndt, S., Jørgensen, B. B., LaRowe, D. E., Middelburg, J. J., Pancost, R. D., and Regnier, P.: Quantifying the degradation of organic matter in marine sediments: A review and synthesis, Earth Sci. Rev., 123, 53–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.02.008, 2013.

Barbier, E. B., Hacker, S. D., Kennedy, C., Koch, E. W., Stier, A. C., and Silliman, B. R.: The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services, Ecol. Monogr., 81, 169–193, https://doi.org/10.1890/10-1510.1, 2011.

Bauer, J. E., Cai, W. J., Raymond, P. A., Bianchi, T. S., Hopkinson, C. S., and Regnier, P. A. G.: The changing carbon cycle of the coastal ocean, Nature, 504, 61–70, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12857, 2013.

Bianchi, T. S. and Bauer, J. E.: Particulate Organic Carbon Cycling and Transformation, Elsevier Inc., 69–117, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374711-2.00503-9, 2012.

Bianchi, T. S., Cui, X., Blair, N. E., Burdige, D. J., Eglinton, T. I., and Galy, V.: Centers of organic carbon burial and oxidation at the land-ocean interface, Org. Geochem., 115, 138–155, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2017.09.008, 2018.

Brandini, N., da Costa Machado, E., Sanders, C. J., Cotovicz, L. C., Bernardes, M. C., and Knoppers, B. A.: Organic matter processing through an estuarine system: Evidence from stable isotopes (δ13C and δ15N) and molecular (lignin phenols) signatures, Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci., 265, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2021.107707, 2022.

Brils, J., de Boer, P., Mulder, J., and de Boer, E.: Reuse of dredged material as a way to tackle societal challenges, Journal of Soils and Sediments, 14, 1638–1641, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-014-0918-0, 2014.

Burd, A. B., Frey, S., Cabre, A., Ito, T., Levine, N. M., Lønborg, C., Long, M., Mauritz, M., Thomas, R. Q., Stephens, B. M., Vanwalleghem, T., and Zeng, N.: Terrestrial and marine perspectives on modeling organic matter degradation pathways, Glob. Chang. Biol., 22, 121–136, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12987, 2016.

Burdige, D. J.: Preservation of organic matter in marine sediments: Controls, mechanisms, and an imbalance in sediment organic carbon budgets?, Chem. Rev., 107, 467–485, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr050347q, 2007.

Burdige, D. J.: Estuarine and Coastal Sediments – Coupled Biogeochemical Cycling, Elsevier Inc., 279–316, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374711-2.00511-8, 2012.

Buurman, P., Nierop, K. G. J., Pontevedra-Pombal, X., and Martínez Cortizas, A.: Chapter 10 Molecular chemistry by pyrolysis-GC/MS of selected samples of the Penido Vello peat deposit, Galicia, NW Spain, Developments in Earth Surface Processes, 9, 217–240, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0928-2025(06)09010-9, 2006.

Canuel, E. A. and Hardison, A. K.: Sources, Ages, and Alteration of Organic Matter in Estuaries, Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci., 8, 409–434, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-122414-034058, 2016.

Cao, C., Cai, F., Qi, H., Zhao, S., and Wu, C.: Differences in the sulfate–methane transitional zone in coastal pockmarks in various sedimentary environments, Water (Switzerland), 13, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.3390/w13010068, 2021.

Carneiro, L. M., do Rosário Zucchi, M., de Jesus, T. B., da Silva Júnior, J. B., and Hadlich, G. M.: δ13C, δ15N and TOC/TN as indicators of the origin of organic matter in sediment samples from the estuary of a tropical river, Mar. Pollut. Bull., 172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112857, 2021.

Chow, W. L., Chong, S., Lim, J. W., Chan, Y. J., Chong, M. F., Tiong, T. J., Chin, J. K., Pan, G. T., Puyuelo, B., Ponsá, S., Gea, T., Sánchez, A., Szulc, W., Rutkowska, B., Gawroński, S., and Wszelaczyńska, E.: Determining C N ratios for typical organic wastes using biodegradable fractions, Processes, 85, 653–659, https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9091501, 2020.

Cloern, J. E., Canuel, E. A., and Harris, D.: Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope composition of aquatic and terrestrial plants of the San Francisco Bay estuarine system, Limnol. Oceanogr., 47, 713–729, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2002.47.3.0713, 2002.

Cox, J. R., Dunn, F. E., Nienhuis, J. H., van der Perk, M., and Kleinhans, M. G.: Climate change and human influences on sediment fluxes and the sediment budget of an urban delta: The example of the lower rhine–meuse delta distributary network, Anthropocene Coasts, 4, 251–280, https://doi.org/10.1139/anc-2021-0003, 2021.

Dauwe, B., Middelburg, J. J., and Herman, P. M. J.: Effect of oxygen on the degradability of organic matter in subtidal and intertidal sediments of the North Sea area, 215, 13–22, 2001.

Dürr, H. H., Laruelle, G. G., van Kempen, C. M., Slomp, C. P., Meybeck, M., and Middelkoop, H.: Worldwide Typology of Nearshore Coastal Systems: Defining the Estuarine Filter of River Inputs to the Oceans, Estuaries and Coasts, 34, 441–458, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-011-9381-y, 2011.

Egger, M., Riedinger, N., Mogollón, J. M., and Jřrgensen, B. B.: Global diffusive fluxes of methane in marine sediments, Nat. Geosci., 11, 421–425, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0122-8, 2018.

Fabbri, D., Sangiorgi, F., and Vassura, I.: Pyrolysis-GC-MS to trace terrigenous organic matter in marine sediments: A comparison between pyrolytic and lipid markers in the Adriatic Sea, Anal. Chim. Acta, 530, 253–261, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2004.09.020, 2005.

Fairbairn, L., Rezanezhad, F., Gharasoo, M., Parsons, C. T., Macrae, M. L., Slowinski, S., and Van Cappellen, P.: Relationship between soil CO2 fluxes and soil moisture: Anaerobic sources explain fluxes at high water content, Geoderma, 434, 116493, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2023.116493, 2023.

Finlay, J. C. and Kendall, C.: Stable Isotope Tracing of Temporal and Spatial Variability in Organic Matter Sources to Freshwater Ecosystems, in: Stable Isotopes in Ecology and Environmental Science, edited by: Michener, R. and Lajtha, K., Wiley, 283–333, https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470691854.ch10, 2007.

Freitas, F. S., Pika, P. A., Kasten, S., Jørgensen, B. B., Rassmann, J., Rabouille, C., Thomas, S., Sass, H., Pancost, R. D., and Arndt, S.: New insights into large-scale trends of apparent organic matter reactivity in marine sediments and patterns of benthic carbon transformation, Biogeosciences, 18, 4651–4679, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-18-4651-2021, 2021.

Gao, Y., Wang, Y., Lee, H. S., and Jin, P.: Significance of anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) in mitigating methane emission from major natural and anthropogenic sources: a review of AOM rates in recent publications, Environmental Science: Advances, 1, 401–425, https://doi.org/10.1039/d2va00091a, 2022.

Gebert, J., Knoblauch, C., and Gröngröft, A.: Gas production from dredged sediment, Waste Management, 85, 82–89, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.12.009, 2019.

Gelesh, L., Marshall, K., Boicourt, W., and Lapham, L.: Methane concentrations increase in bottom waters during summertime anoxia in the highly eutrophic estuary, Chesapeake Bay, U.S.A., Limnol. Oceanogr., 61, S253–S266, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10272, 2016.

Georgiou, K., Jackson, R. B., Vindušková, O., Abramoff, R. Z., Ahlström, A., Feng, W., Harden, J. W., Pellegrini, A. F. A., Polley, H. W., Soong, J. L., Riley, W. J., and Torn, M. S.: Global stocks and capacity of mineral-associated soil organic carbon, Nat. Commun., 13, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31540-9, 2022.

Guillemette, F., McCallister, S. L., and Del Giorgio, P. A.: Differentiating the degradation dynamics of algal and terrestrial carbon within complex natural dissolved organic carbon in temperate lakes, J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci., 118, 963–973, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrg.20077, 2013.

Hansen, L. S. and Blackburn, T. H.: Aerobic and anaerobic mineralization of organic material in marine sediment microcosms, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 75, 283–291, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps075283, 1991.

Haynes, R. J.: Labile Organic Matter Fractions as Central Components of the Quality of Agricultural Soils: An Overview, Advances in Agronomy, 85, 221–268, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2113(04)85005-3, 2005.

He, Y., Zhang, T., Zhao, Q., Gao, X., He, T., and Yang, S.: Response of GHG emissions to interactions of temperature and drying in the karst wetland of the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, Front. Environ. Sci., 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.973900, 2022.

Heckbert, S., Costanza, R., Poloczanska, E. S., and Richardson, A. J.: Climate Regulation as a Service from Estuarine and Coastal Ecosystems, Elsevier Inc., 199–216, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374711-2.01211-0, 2012.

Hedges, J. I. and Oades, J. M.: Comparative organic geochemistries of soils and marine sediments, Org. Geochem., 27, 319–361, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0146-6380(97)00056-9, 1997.

Herfort, L., Schouten, S., Boon, J. P., Woltering, M., Baas, M., Weijers, J. W. H., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S.: Characterization of transport and deposition of terrestrial organic matter in the southern North Sea using the BIT index, Limnol. Oceanogr., 51, 2196–2205, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2006.51.5.2196, 2006.

Holligan, P. M. and Reiners, W. A.: Predicting the Responses of the Coastal Zone to Global Change, Adv. Ecol. Res., 22, 211–255, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60137-3, 1992.

Hopmans, E. C., Weijers, J. W. H., Schefuß, E., Herfort, L., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., and Schouten, S.: A novel proxy for terrestrial organic matter in sediments based on branched and isoprenoid tetraether lipids, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 224, 107–116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2004.05.012, 2004.

Hopmans, E. C., Schouten, S., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S.: The effect of improved chromatography on GDGT-based palaeoproxies, Org. Geochem., 93, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2015.12.006, 2016.

Hulot, V., Metzger, E., Thibault de Chanvalon, A., Mouret, A., Schmidt, S., Deflandre, B., Rigaud, S., Beneteau, E., Savoye, N., Souchu, P., Le Merrer, Y., and Maillet, G. M.: Impact of an exceptional winter flood on benthic oxygen and nutrient fluxes in a temperate macrotidal estuary: Potential consequences on summer deoxygenation, Front. Mar. Sci., 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1083377, 2023.

Hulthe, G., Hulth, S., and Hall, P. O. J.: Effect of oxygen on degradation rate of refractory and labile organic matter in continental margin sediments, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 62, 1319–1328, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(98)00044-1, 1998.

Huo, C., Luo, Y., and Cheng, W.: Rhizosphere priming effect: A meta-analysis, Soil Biol. Biochem., 111, 78–84, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.04.003, 2017.

Hutchings, J. A., Bianchi, T. S., Najjar, R. G., Herrmann, M., Kemp, W. M., Hinson, A. L., and Feagin, R. A.: Carbon Deposition and Burial in Estuarine Sediments of the Contiguous United States, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 34, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GB006376, 2020.

IJsseldijk, L. L., Camphuysen, K. C. J., Nauw, J. J., and Aarts, G.: Going with the flow: Tidal influence on the occurrence of the harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) in the Marsdiep area, The Netherlands, J. Sea Res., 103, 129–137, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seares.2015.07.010, 2015.

Kaal, J.: Analytical pyrolysis in marine environments revisited, Analytical Pyrolysis Letters, 1–16, https://pyrolyscience.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/APL006.pdf (last access: 2 February 2026), 2019.

Kaal, J., Martínez Cortizas, A., Mateo, M. Á., and Serrano, O.: Deciphering organic matter sources and ecological shifts in blue carbon ecosystems based on molecular fingerprinting, Science of the Total Environment, 742, 140554, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140554, 2020.

Keil, R., Montluçon, D., Prahl, F., and Hedges, J.: Sorptive preservation of labile organic matter in marine sediments, Nature, 370, 549–552, https://doi.org/10.1038/370549a0, 1994.

Kirichek, A., Rutgers, R., Wensween, M., and van Hassent, A.: Sediment management in the Port of Rotterdam, in: Baggern – Unterbringen – Aufbereiten – Verwerten, Steinbeis-Transverzentrum Angewandte Landschaftsplanung, Rostock, Germany, 11–12 September 2018, 1–8, https://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:ce955781-bfbc-4ca5-a996-842b3ffcc0d8 (last access: 2 February 2026), 2018.

Kraal, P., Burton, E. D., Rose, A. L., Cheetham, M. D., Bush, R. T., and Sullivan, L. A.: Decoupling between water column oxygenation and benthic phosphate dynamics in a shallow eutrophic estuary, Environ. Sci. Technol., 47, 3114–3121, https://doi.org/10.1021/es304868t, 2013.

Kuliński, K., Rehder, G., Asmala, E., Bartosova, A., Carstensen, J., Gustafsson, B., Hall, P. O. J., Humborg, C., Jilbert, T., Jürgens, K., Meier, H. E. M., Müller-Karulis, B., Naumann, M., Olesen, J. E., Savchuk, O., Schramm, A., Slomp, C. P., Sofiev, M., Sobek, A., Szymczycha, B., and Undeman, E.: Biogeochemical functioning of the Baltic Sea, Earth Syst. Dynam., 13, 633–685, https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-13-633-2022, 2022.

Kuwae, T., Kanda, J., Kubo, A., Nakajima, F., Ogawa, H., Sohma, A., and Suzumura, M.: Blue carbon in human-dominated estuarine and shallow coastal systems, Ambio, 45, 290–301, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-015-0725-x, 2016.

Lamb, A. L., Wilson, G. P., and Leng, M. J.: A review of coastal palaeoclimate and relative sea-level reconstructions using δ13C and C N ratios in organic material, Earth Sci. Rev., 75, 29–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.10.003, 2006.

LaRowe, D. E. and Van Cappellen, P.: Degradation of natural organic matter: A thermodynamic analysis, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 75, 2030–2042, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2011.01.020, 2011.

LaRowe, D. E., Arndt, S., Bradley, J. A., Estes, E. R., Hoarfrost, A., Lang, S. Q., Lloyd, K. G., Mahmoudi, N., Orsi, W. D., Shah Walter, S. R., Steen, A. D., and Zhao, R.: The fate of organic carbon in marine sediments – New insights from recent data and analysis, Earth Sci. Rev., 204, 103146, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103146, 2020.

Laruelle, G. G., Dürr, H. H., Slomp, C. P., and Borges, A. V.: Evaluation of sinks and sources of CO2 in the global coastal ocean using a spatially-explicit typology of estuaries and continental shelves, Geophys. Res. Lett., 37, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GL043691, 2010.